#medieval Greek

Text

Green horses

More Greek etymological madness!

There is a saying in modern Greek, πράσινα άλογα (prásina álogha), which literally means “green horses”. It is usually added to the end of a sentence to show that something is crazy, unbelievable, foolish and to express disbelief for a statement.

i.e «Είπε ότι θα είναι πάντα στην ώρα του από δω και στο εξής και πράσινα άλογα»

(“He said he will always be on time from now on and green horses”)

The sentence indicates that the person has not stopped being late or that there is disbelief expressed that this person has the ability to even start trying being on time.

Why green horses though? How did this come to be?

Interestingly, no, it was not formed as a concept due to the inherent improbability of a horse being green. It originally had nothing to do with horses, let alone green ones.

The phrase originates from the ancient «πράσσειν άλογα» (prásin álogha) which means “acting thoughtlessly”.

The sound similarity between πράσσειν (prásin, acting) and πράσινα (prásina, green) is entirely incidental. The άλογα (álogha, thoughtlessly / horses) is on the contrary the same word! You see, the “official” Greek word for horse is ίππος (hippos or ippos). However, all animals were often called in ancient and especially medieval times as άλογα, from the negative α- and the noun λόγος which means logic, reason. Therefore animals were called álogha, beings without logic. The more the language evolved the word started describing horses more specific until in modern Greek it became the standard word for horse, overcoming ίππος by a long shot.

The phrase was surviving throughout in some way or another, however now the meaning of άλογα was getting enriched (it still also means “thoughtlessly”). Simultaneously, the infinitive «πράσσειν» was slowly fading, especially because its other lexical variant «πράττειν» (prátin, also means acting) was more popular and its verb is still used in its -t- variant nowadays.

So as πράσσειν was gradually becoming rarer and άλογα was getting a double meaning, people either out of humour or out of poor vocabulary morphed the phrase into πράσινα άλογα, green horses!

Interestingly it still expresses judgement against someone’s perceived stupidity, unreliability or madness (acting thoughtlessly)!

#greece#Greek#languages#language stuff#linguistics#langblr#Greek language#modern Greek#Ancient Greek#medieval Greek#Greek culture

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

That time in ancient Greece when Aziraphale needed a speedy horse and accidentally invented the pegasus

VS.

Whatever Crowley had going on in medieval times

#Crowley just really misses the unicorns ok???#Also Crowley didn't start from a horse to make a new unicorn#he looked at a horse and was like.... nah#then looked at a goat and was like YEAAAAH LET'S GOO LET'S MAKE YOU BIG AF AND YOU CAN ALSO SPIT FIRE WHAT A GREAT IDEA!!#While Aziraphale is fretting over the fact that he accidentally gave WINGS to a HORSE and every time that the angels asks about it he's lik#whaaat?? PegaSUS naaaah never heard about it. Must be a made up thing. humans...right?? silly little things ahahah *sweat nervously*#good omens#crowley#aziraphale#ineffable husbands#aziracrow#pegasus#unicorn#Do I wanna draw the precious good omens beans? yes.#is this an excuse to draw more horses? also yes.#medieval crowley#ancient greek aziraphale#CAVALLIIIIIII 🐎🐴🐎🐴🐎🐴🐎🐴#good omens comic#historical husbands

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

#hermes worship#hermes#mercury#hermes god#ancient greek god#greek god#coin#greek myth#greek myth art#ancient greek mythology#greek mythology#ancient greek coin#roman coin#medieval coin

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

dido tearing her hair out in madness & dido's suicide

in an illustrated copy of the 'eneasroman' by heinrich von veldeke, alsace, c. 1419

source: Heidelberg, UB, Cod. Pal. germ. 403, fol. 32v and 51r

#15th century#eneasroman#heinrich von veldeke#dido#greek mythology#madness#queens#violence#medieval art

569 notes

·

View notes

Text

Virgil and Dante Sitting on the Back of Geryon by Bartolomeo Pinelli

#virgil#dante#geryon#art#bartolomeo pinelli#inferno#hell#divine comedy#the divine comedy#dante alighieri#medieval#middle ages#religion#religious#christianity#christian#europe#european#italy#mythical creatures#monster#monsters#giant#giants#greek mythology#mythology#laurel wreath

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

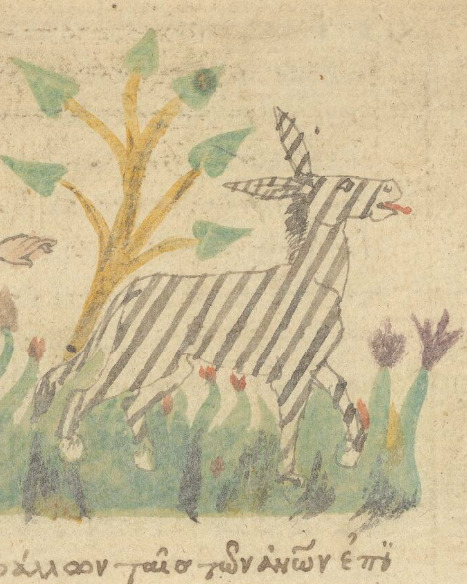

More for #InternationalZebraDay: zebras in a Byzantine Greek illuminated manuscript of the Book of Job, c. 1362.

BnF Grec 135, f. 100r and 224r.

#zebra#zebras#mammals#illustration#manuscript#illuminated manuscript#medieval manuscript#Byzantine#Greek#medieval art#Byzantine art#Greek art#14th century#Book of Job#BnF#Bibliothèque nationale de France#International Zebra Day#animals in art

526 notes

·

View notes

Text

Various knights and soldiers

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

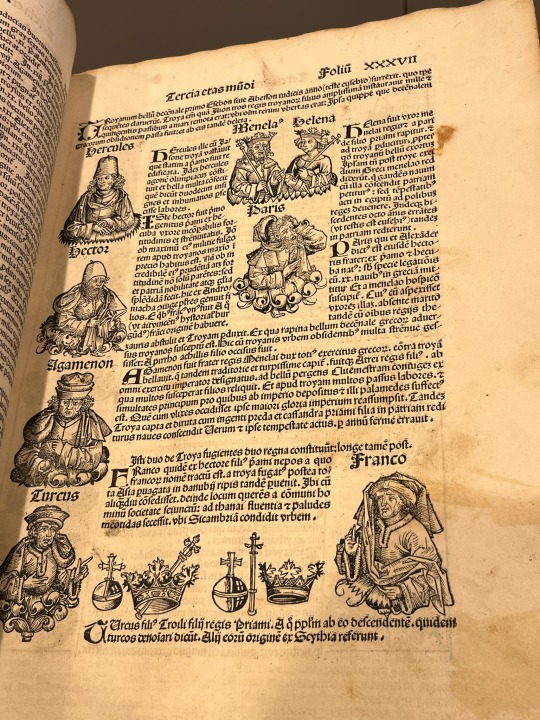

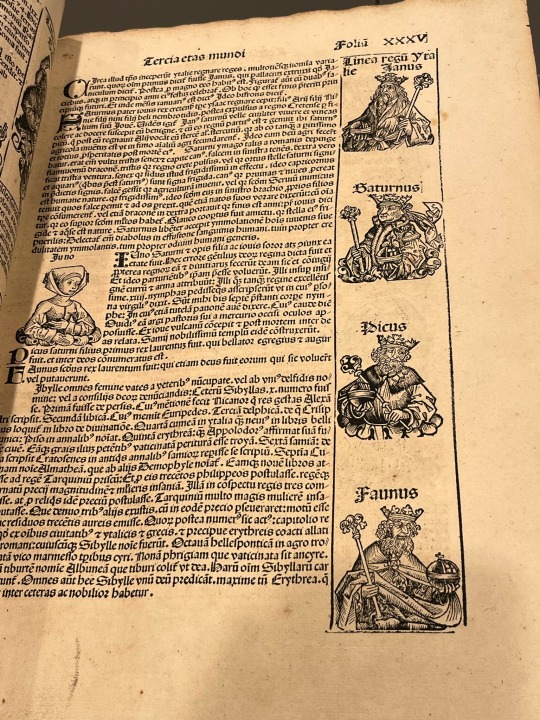

Have you ever wondered what characters from Greek mythology would look like in a medieval AU? Wonder no more:

In the first picture are Hercules on the top left, Menelaus and Helen in the middle, Paris underneath them, and Hector and Agamemnon underneath Hercules. In the second picture are Janus, Saturn, Picus, and Faunus on the right, and Juno on the left.

(This is the Nuremberg Chronicle, a fifteenth-century German incunabulum.)

#early modern#incunabula#early printed books#medieval studies#greek mythology#greek myth art#trojan war#Hercules#Heracles#Agamemnon#menelaus#helen of troy#faunus#saturnus#Juno#janus

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Byzantine " Greek Fire" Grenade, c. 800-1000 AD.

The vessel was filled with a volatile concoction, usually a mixture of flammable liquids, sulphur and other combustible substances. It was then thrown at enemy ships or troops, where the impact caused the vessel to burst, dispersing the fiery contents and setting the target ablaze.

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

νόστιμον ἦμαρ

There are two words in Modern Greek that are frequently used for the meanings of “tasty”, “delicious”. The most literal one is εύγευστος (évyefstos) which comes from the words ευ and γεύση and literally means “having good / pleasant flavour / taste”.

The other one is more common in everyday speech however. That is νόστιμος (nóstimos), which in Modern Greek means “tasty” and when used figuratively and colloquially it can also refer to a person you find physically attractive.

This has been the usage of the word since Medieval Greek, when the word was also used to describe something tasty, pretty or generally pleasant in any way.

The word is much older than that as its etymology reveals. Νόστιμος comes from the Homeric Greek word νόστος (nóstos), which of course means “coming home” and “returning to your homeland / hometown / place”. The adjective itself was used in the epics as well in the phrase «νόστιμον ἦμαρ», which in Modern Greek would be like «νόστιμη ημέρα» (!) but of course it did not mean “tasty day” but actually “the sweet day of returning home”.

This gives us more insight into how important it was for Ancient Greeks to return to their homeland, how much they prized that feeling of warmth, fuzziness and familiarity. Therefore, it seems that good things were often valued depending on how much they reminded them of home and of their own ways.

The exact meaning of a νόστιμο φαγητό (tasty food) is that it reminds you of the hearty, homemade meals you remember from your family, your grandma, your hometown or country. And in your mind, these qualities immediately make it delicious. This was a concept that was so common and unquestionable throughout the centuries that the word, which has no etymological connection to the words associated to flavour and food, has been used without the merest second thought to this day to denote something delicious.

And just as interestingly but totally in the same spirit, one modern word for “flavourless”, “bland”, “boring” is άνοστος (ánostos) which also existed in Ancient Greek but etymologically it would mean “not (like) returning home”!

Bonus grammatical context:

The differentiations in the word endings i.e in νόστιμον, νόστιμη are the gender endings and not conceptual or lexical differences. That is because the ancient version ἦμαρ and the modern version ημέρα are neuter and feminine respectively. This is not however a change that happened chronologically from ancient to modern Greek but it was due to the different variations of the word amongst several ancient dialects. ἦμαρ was used in poetic speech often however the modern ημέρα comes of course directly from the more common ancient form ἡμέρα (heméra). It was also the name of the deity of the day.

#greece#languages#Greek#Greek language#language stuff#linguistics#etymology#langblr#modern Greek#ancient Greek#Homeric Greek#medieval Greek#Greek culture

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

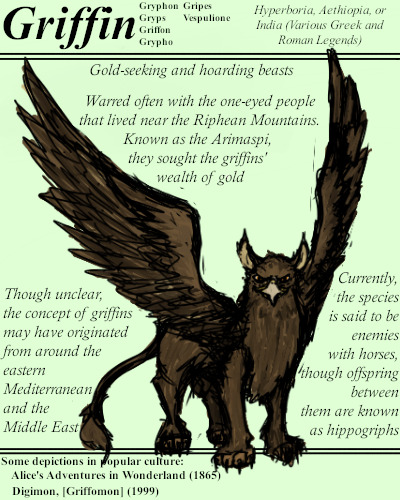

Folklore Fact - Gryphons/Griffins

Gryphons, griffins, griffons, however you prefer to spell it (I personally use gryphon) - let's talk their folklore and mythology!

(Attic pottery depicting a satyr and a griffin and an Arimaspus from around 375-350 BC, Eretria.)

You probably already know the common popular culture concept of a gryphon: a big, vicious beast that attacks people and probably eats them and/or carries people away to its nest to feed them to its babies. Not much about it has changed in legend, though in a lot of popular culture today, it has seemed to lose its divinity. Gryphons - griffins, whatever you prefer - have quite the robust history, like so many creatures of myth and folklore. Unlike some, however, they have changed very little over time.

Note that this article a general overview of concepts, not a detailed history.

Let's start with etymology, because I just love that stuff. The word "griffin" comes from the Greek word "gryps," which referred to a dragon or griffin and literally meant "curved [or] hook-nosed." Late Latin spelled it "gryphus," a misspelling of grypus, a Latinized version of the Greek (source: https://www.etymonline.com/, one of my favorite websites).

Griffins are said to have the head and wings of an eagle and body of a lion. They may or may not also have pointed ears, depending on the depiction (they more often did, overall, though the griffin of Crete is a notable exception). They were said to guard the gold in the mountains of the north, specifically the mountains of Scythia. The one-eyed Arimaspian people rode on horseback and attempted to steal the griffins' gold, causing griffins to nurture a deep hatred of and hostility toward horses.

A Scythian pectoral, thought to have been made in Greece, depicting - among other things - griffins slaughtering horses. Griffins really, really hate horses.

The famous griffin in the palace of Knossos at Crete, from the Bronze Age (restored).

Griffins appear in truly ancient civilizations, not only Greece but also ancient Egypt and civilizations to the east, including ancient Sumeria. Griffins were later said to also dwell in India and guard gold in that region, and they continued to appear in art throughout ancient Persia, Rome, Byzantium, and into the Middle Ages throughout other regions such as France; they were depicted in ancient Greece with relative frequency and occasionally of considerable importance.

Griffins appeared in many ancient Greek writings, including Aristeas in the 7th century BC. Herodotus and Aeschylus preserved and continued these writings in the 5th century BC, including lines such as,

"But in the north of Europe there is by far the most gold. In this matter again I cannot say with assurance how the gold is produced, but it is said that one-eyed men called Arimaspoi (Arimaspians) steal it from Grypes (Griffins). The most outlying lands, though, as they enclose and wholly surround all the rest of the world, are likely to have those things which we think the finest and the rarest." Herodotus, Histories 3. 116. 1 (trans. Godley) (Greek historian C5th B.C.), source: https://www.theoi.com/Thaumasios/Grypes.html (a wonderful site)

Physical descriptions of the griffin were not commonplace until some later works, and even then, their appearance wasn't always agreed upon. Even the notion of griffins having wings was sometimes disputed. Some scholars even got pretty wild, claiming griffons had no wings at all but instead skin-flaps that they used to glide. They apparently hated awesome things, so it turns out there were always boring people who thought they knew everything, wanted to explain everything "logically," and generally assume they were the smartest ever while also ruining mystique. They would make great scientists today.

Griffins were, however, often said to be holy in nature. They were referred to as the "unbarking hounds of Zeus" by Aeschylus, who warned others never to approach them. Gryphons were also considered sacred to several gods, including prominently Apollo, who was said to depart Delphi each winter, flying on a griffon (griffin, gryphon, etc, I keep swapping this around, I know; my brain spells it differently because I've read way too many sources), and he also is occasionally depicted as hitching griffins to his chariot in addition to riding one. This was particularly prominent in the cults of Hyperborean Apollo, one of the many endless and fascinating cults of ancient Greece.

Medieval bestiary depiction of a griffin slaughtering a horse.

Even by the Middle Ages, gryphons still hated and slaughtered horses and guarded gold, elements that certainly persisted throughout their legends. They also killed men and carried them away to their nests, similar to the manner in which Aeschylus warned people to stay away from gryphons even back when. We can obviously assume griffons were never cuddly, so that isn't much of a change.

Griffins also did not entirely lose their divine relations even into the Middle Ages. Christianity often used positive portrayals of griffins to represent and uphold certain positive tenets of Christian faith; likewise, they became important symbols of medieval heraldry, used to represent a Christian symbol of divine power, as well as general courage, strength, and leadership, especially in a military sense. The depiction of the griffin as a powerful and majestic creature - killing horses and men or not - throughout its history is no doubt because they are a combination of two beasts often considered noble symbols of bravery, power, and divinity: the lion and the eagle, kings of land animals and birds, respectively.

That's a general overview! As you can see, griffins aren't always so bad, at least not compared to some of the other creatures out there from folklore and myth.

( If you like my blog, be sure to follow me here and sign up for my free newsletter for more folklore and fiction, including books!

Free Newsletter - maverickwerewolf.com (info + book shop) — Patreon — Wulfgard — Werewolf Fact Masterlist — Twitter — Vampire Fact Masterlist — Amazon Author page )

#folklore#mythology#gryphon#griffin#fantasy creature#gryphons#griffins#griffon#folklore fact#folklore thursday#greek myth#myth#persian myth#medival#medieval folklore#history

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Legendary beasts that once warred with the horse-riding Arimaspians.

Apparently the Indian Griffin is a type of griffin about the size of a wolf with a unique plumage coloration. Regardless, this particular variation of the species also nests as close to local gold deposits as possible, just like their relatives outside of India.

#BriefBestiary#bestiary#digital art#fantasy#folklore#legend#myth#mythology#griffin#gryphon#griffon#gryps#grypho#gripes#vespulione#medieval legend#greek legend#roman legend#hyperborea#riphean mountains#arimaspi#beast

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

the three furies

in a copy of john ridewall's 'fulgentius metaforalis', bavaria, c. 1424

source: Vatican, Bibl. Apostolica Vaticana, Pal. lat. 1066, fol. 221r

426 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Fireships, Flamethrowers & Hand Grenades? - What We Actually Know About the "Greek Fire"

from SandRhoman History

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just realised something fun!! If Laszlo had a typical Georgian/Victorian rich person education, he almost definitely learned a decent amount of ancient Latin and ancient greek. From what I know of greek in general (very little) the modern version is to ancient greek as modern English is to Shakespearean English - as in, it takes some getting used to and there are lots of dialects to figure out but it's more similar than you'd expect. Antipaxos probably has/had a pretty strong dialect (Doric? I think?) but I just think the idea of Nadja saying something in Greek and Laszlo responding in (simultaneously broken and weirdly formal) Greek...... Nadja would be so excited and they'd sort of smoothe over the differences and end up with their own dialect and I just. I just. Please

(bonus: Laszlo would exclusively speak in quotes from ancient greek works because most Victorian education was by rote ie you just memorised texts. Nadja wouldn't have been taught any of this ancient stuff probably except the bible in Greek* so she thinks he's just really philosophical)

(extra but ahistorical bonus: he wouldn't know Sappho because the Christians burnt and hid all her stuff so it wasn't taught til v recently but. What if he recited sappho to Nadja)

*biblical Greek is very similar to Homeric greek so that would be a point of crossover maybe??? I'm taking this too far perhaps

#maybe ill write it?#but i wouldn't be able to write any of the medieval greek esp with an accurate dialect#i do know some sappho by heart#and i have access to the ancient greek editions of some texts#is that too extra#im so invested in this headcanon#wwdits#nadja of antipaxos#laszlo cravensworth#laszlo x nadja

235 notes

·

View notes

Note

As a Greek i find hilarious and bitter that people still remember the ancient tales of our ancestors and are studied globally hoe well written they were but we modern Greeks don't produce that anymore like why?

Where did all the creativity go instead of making the same stories everyone globally make that sometimes don't even reflect our society?

I understand what you mean cause I've heard the same comment many times, but let me come to this from another angle.

Fuck what foreigners think. The ancient Greek works have great merit and no one in the world is wrong for studying them and appreciating them. However, the overstudy of these manuscripts has led to needless over-analyzing of texts and the overlook of other great Greek works. The Western world has focused so much on ancient Greek works and has talked only about them for such a long time that more than half the world has forgotten that Greeks existed beyond that era.

We have GREAT literary Greek works from medieval times. It wasn't "the Dark Ages" for us, baby! I'm talking about the Alexeiad, the Digenes Akritas Epic cycle, the satiric works "Timarion" and "Mazaris", the poem the "Spaneas", the (huuuge) "Fountain of Knowledge" by Ioannis Damaskinos, the historical work of Ioannis Malalas, the works of Mihail Psellos, the HUNDREDS of medical and scientific books, and other works that influenced the East and the West alike. That's just the tip of the iceberg!

Why don't we feel proud about those? Because we don't know them. Why don't we know them? Because it's not trendy to study these periods.

We also don't talk about the hundreds of amazing writers we had the last century - including those who got Nobels - because that's not trendy right now.

We have to stop seeing the value of Greek literature through the eyes of foreigners. We have to promote Greek works because we can't just wait for a Shannon in New Jersey, US, to discover it and like it, in order for us to appreciate it too.

Also, we cannot re-invent the wheel. Our ancestors wrote some great stuff for their era. In 2023 this stuff is still great but it's not THAT revolutionary. So there's no comparison in regards to novelty. But we can produce good works regardless.

Greece is not a colonial power or a former colonial power like the European "Big Powers" (these 8 countries), or an empire like the US. Our nation is still recovering for 400-600 years of slavery and occupation AND the dozens of traumatising conflicts and wars that came after that. We can't expect the same growth at the same numbers as these luckier countries. We can't afford as a nation to have extremely popular events and promote the arts like they do in LA, or in Berlin, or London. Let's be kind to ourselves.

In continuation of the previous point, Greece today doesn't have enough powerful publishing houses to back great writers. Our writers, except 4-5 names in the whole country, don't see a penny from their work even after selling hundreds of copies. Even if you earn something, it's not even enough for a month's groceries. So writers either have to choose to spend only 10% of their time writing, or 80% of their time writing and live penniless.

The creativity is there, but Greeks rarely have the time and resources to pursue their writing passion to the point of greatness.

35 notes

·

View notes