#land conservation and preservation

Text

Biden creates a new national monument near the Grand Canyon - https://www.npr.org/2023/08/08/1192622716/biden-national-monument-grand-canyon-arizona

The move protects lands that are sacred to indigenous peoples and permanently bans new uranium mining claims in the area. It covers nearly 1 million acres.

—

"It will help protect lands that many tribes referred to as their eternal home, a place of healing and a source of spiritual sustenance," she said. "It will help ensure that indigenous peoples can continue to use these areas for religious ceremonies, hunting and gathering of plants, medicines and other materials, including some found nowhere else on earth. It will protect objects of historic and scientific importance for the benefit of tribes, the public and for future generations."

—

The new national monument will be called Baaj Nwaavjo I'tah Kukveni Grand Canyon National Monument. According to the Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition that drafted a proposal for the monument, "Baaj Nwaavjo" means "where tribes roam" in Havasupai, and "I'tah Kukveni" translates to "our ancestral footprints" in Hopi.

all land is sacred (and should be returned) but this is good news.

#indigenous#native american#ndn#arizona#grand canyon#climate change#nature#good news#land conservation and preservation#hopi#havasupai

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Maximize AI’s Investment with Bitcoin

How will AI and cryptocurrency interact and intersect? “There’s a whole slew of possibilities,” Whittemore says. Some are obvious, some are bizarre, some are optimistic, and some are terrifying. To provide some order to the chaos, we’ll look at ten probable areas of overlap…ranging from productivity gains to Armageddon.

Read more https://rb.gy/rg6ob

#indigenous#native american#ndn#arizona#grand canyon#climate change#nature#good news#land conservation and preservation#hopi#wwdtis#wwdits season 5#wwdits s5#wwdits s5 spoilers#wwdits fx#ai#bitcoin#crypto

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

West African countries such as Liberia, Senegal and Guinea-Bissau, communities have designated biodiversity hotspots, including forests and lagoons, as sacred. This system has served as a conservation tool respected by these communities for generations. The community's existence is intricately linked to the well-being and survival of the biodiversity and natural resources surrounding it.

The Western African method is to reinforce communal stewardship of the land, rather than ownership. The system starkly contrasts with some current, non-Indigenous North American methods of prohibiting humans from living in certain protected areas. Placing a dollar value on conserving these areas risks destroying the very belief system and way of thinking that have ensured their survival in the first place. Their value of biodiversity cannot be translated into monetary terms.

#biodiversity#west africa#environmentalism#habitat preservation#african#africa#biology#culture#liberia#senegal#guinea bissau#traditional culture#african tribe#conservation#sacred land#logging company#protected land

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

April 7, 2024 (Sunday)

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

APR 08, 2024

In August 1870 a U.S. exploring expedition headed out from Montana toward the Yellowstone River into land the U.S. government had recognized as belonging to different Indigenous tribes.

By October the men had reached the Yellowstone, where they reported they had “found abundance of game and trout, hot springs of five or six different kinds…basaltic columns of enormous size” and a waterfall that must, they wrote, “be in form, color and surroundings one of the most glorious objects on the American Continent.” On the strength of their widely reprinted reports, the secretary of the interior sent out an official surveying team under geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden. With it went photographer William Henry Jackson and fine artist Thomas Moran.

Banker and railroad baron Jay Cooke had arranged for Moran to join the expedition. In 1871 the popular Scribner’s Monthly published the surveyor’s report along with Moran’s drawings and a promise that Cooke’s Northern Pacific Railroad would soon lay tracks to enable tourists to see the great natural wonders of the West.

But by 1871, Americans had begun to turn against the railroads, seeing them as big businesses monopolizing American resources at the expense of ordinary Americans. When Hayden called on Congress to pass a law setting the area around Yellowstone aside as a public park, two Republicans—Senator Samuel Pomeroy of Kansas and Delegate William H. Clagett of Montana—introduced bills to protect Yellowstone in a natural state and provide against “wanton destruction of the fish and game…or destruction for the purposes of merchandise or profit.”

The House Committee on Public Lands praised Yellowstone Valley’s beauty and warned that “persons are now waiting for the spring…to enter in and take possession of these remarkable curiosities, to make merchandise of these bountiful specimens, to fence in these rare wonders so as to charge visitors a fee, as is now done at Niagara Falls, for the sight of that which ought to be as free as the air or water.” It warned that “the vandals who are now waiting to enter into this wonderland will, in a single season, despoil, beyond recovery, these remarkable curiosities which have required all the cunning skill of nature thousands of years to prepare.”

The New York Times got behind the idea that saving Yellowstone for the people was the responsibility of the federal government, saying that if businesses “should be strictly shut out, it will remain a place which we can proudly show to the benighted European as a proof of what nature—under a republican form of government—can accomplish in the great West.”

On March 1, 1872, President U. S. Grant, a Republican, signed the bill making Yellowstone a national park.

The impulse to protect natural resources from those who would plunder them for profit expanded 18 years later, when the federal government stepped in to protect Yosemite. In June 1864, Congress had passed and President Abraham Lincoln signed a law giving to the state of California the Yosemite Valley and nearby Mariposa Big Tree Grove “upon the express conditions that the premises shall be held for public use, resort and recreation.”

But by 1890 it was clear that under state management the property had been largely turned over to timber companies, sheep-herding enterprises, and tourist businesses with state contracts. Naturalist John Muir warned in the Century magazine: “Ax and plow, hogs and horses, have long been and are still busy in Yosemite’s gardens and groves. All that is accessible and destructible is rapidly being destroyed.” Congress passed a law making the land around the state property in Yosemite a national park area, and the United States military began to manage the area.

The next year, in March 1891, Congress gave the president power to “set apart and reserve…as public reservations” land that bore at least some timber, whether or not that timber was of any commercial value. Under this General Revision Act, also known as the Forest Reserve Act, Republican president Benjamin Harrison set aside timber land adjacent to Yellowstone National Park and south of Yosemite National Park. By September 1893, about 17 million acres of land had been put into forest reserves. Those who objected to this policy, according to Century, were “men [who] wish to get at it and make it earn something for them.”

Presidents of both parties continued to protect American lands, but in the late nineteenth century it was New York Republican politician Theodore Roosevelt who most dramatically expanded the effort to keep western lands from the hands of those who wanted only their timber and minerals.

Roosevelt was concerned that moneygrubbing was eroding the character of the nation, and he believed that western land nurtured the independence and community that he worried was disappearing in the East. During his presidency, which stretched from 1901 to 1909, Roosevelt protected 141 million acres of forest and established five new national parks.

More powerfully, he used the 1906 Antiquities Act, which Congress had passed to stop the looting and sale of Indigenous objects and sites, to protect land. The Antiquities Act allowed presidents to protect areas of historic, cultural, or scientific interest. Before the law was a year old, Roosevelt had created four national monuments: Devils Tower in Wyoming, El Morro in New Mexico, and Montezuma Castle and Petrified Forest in Arizona.

In 1908, Roosevelt used the Antiquities Act to protect the Grand Canyon.

Since then, presidents of both parties have protected American lands. President Jimmy Carter rivaled Roosevelt’s protection of land when he protected more than 100 million acres in Alaska from oil development. Carter’s secretary of the interior, Cecil D. Andrus, saw himself as a practical man trying to balance the needs of business and environmental needs but seemed to think business interests had become too powerful: “The domination of the department by mining, oil, timber, grazing and other interests is over.”

In fact, the fight over the public lands was not ending; it was entering a new phase. Since the 1980s, Republicans have pushed to reopen public lands to resource development, maintaining even today that Democrats have hampered oil production although it is currently, under President Joe Biden, at an all-time high.

The push to return public lands to private hands got stronger under former president Donald Trump. On April 26, 2017, Trump signed an executive order—Executive Order 13792—directing his secretary of the interior, Ryan Zinke, to review designations of 22 national monuments greater than 100,000 acres, made since 1996. He then ordered the largest national monument reduction in U.S. history, slashing the size of Utah’s Bears Ears National Monument by 85%—a goal of uranium-mining interests—and that of Utah’s Escalante–Grand Staircase by about half, favoring coal interests.

“No one better values the splendor of Utah more than you do,” Trump told cheering supporters. “And no one knows better how to use it.”

In March 2021, shortly after he took office, President Biden announced a new initiative to protect 30% of U.S. land, fresh water, and oceans areas by 2030, a plan popularly known as 30 by 30. Also in March 2021, Supreme Court chief justice John Roberts urged opponents of land protection to push back against the Antiquities Act, saying the broad protection of lands presidents have established under it is an abuse of power.

In October 2021, President Biden restored Bears Ears and Escalante–Grand Staircase to their original size. “Today’s announcement is not just about national monuments,” Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a member of the Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico, said at the ceremony. “It’s about this administration centering the voices of Indigenous people and affirming the shared stewardship of this landscape with tribal nations.”

In 2022, nearly 312 million people visited the country’s national parks and monuments, supporting 378,400 jobs and spending $23.9 billion in communities within 60 miles of a park. This amounted to a $50.3 billion benefit to the nation’s economy.

But the struggle over the use of public lands continues, and now the Republicans are standing on the opposite side from their position of a century ago. Project 2025, the blueprint for a second Trump presidency, demands significant increases in drilling for oil and gas. That will require removing land from federal protection and opening it to private development. As Roberts urged, Project 2025 promises to seek a Supreme Court ruling to permit the president to reduce the size of national monuments. But it takes that advice even further.

It says a second Trump administration “must seek repeal of the Antiquities Act of 1906.”

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#Letters From An American#Heather Cox Richardson#public lands#the Antiquities Act of 1906#history#Department of the interior#tribal nations#Teddy Roosevelt#conservation#conservatism#preservation

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wings in the Shadow of Grief

Monarcho bravely flew through the dense forests of the North and encountered Luna, an elegant companion with iridescent wings. "Who are you, noble butterfly, and where does your flight lead you?" inquired Monarcho. Luna, enveloped in golden sunbeams, replied, "I am Luna, on a journey to the southern paradise. My heart longs for the warm realms of Michoacán."

The two butterflies continued to fly side by side, exchanging their stories. "I feel a special connection to a hero named Homero Gómez González," shared Monarcho. "Have you heard of him, Luna?"

Luna respectfully inclined her wings. "Yes, Homero is known in the butterfly lands. A brave protector of our kind. His name is carried from flower to flower, like a gentle breeze."

The majestic mountains that Monarcho crossed provided an epic backdrop to their flights. As they approached the El Rosario Butterfly Preserve, Monarcho felt the tension in the air. Luna whispered, "We are entering a realm of change, Monarcho. Here, the paths of nature and humanity intersect."

In a poignant scene, the two butterflies observed Homero's patrols. Luna said, "Homero fights with a courageous heart. But humanity is a complex being, and nature suffers from its decisions."

In the El Rosario Butterfly Preserve, Homero and a group of passionate environmentalists gathered. "Friends," began Homero, "the Monarch butterflies are not just butterflies; they are a symbol of the fragility of nature. We must unite our forces to protect them from the deforestation threatening their home."

Elena, an experienced environmentalist, stepped forward. "Homero, we know the dangers are real, but we are here to stand side by side with you. Nature needs our voices, and we must raise them loud and clear."

A young activist named Diego added, "We must not only protect the Monarch butterflies but also the forests themselves. They are our common heritage, and it is our responsibility to preserve them for future generations."

Homero nodded in agreement. "Let us form patrols, launch information campaigns, and raise awareness in the community. Together, we can ignite a movement that protects not only the Monarch butterflies but also our habitat."

The environmentalists exchanged looks of determination, and Maria, a naturalist, suggested, "Let us also speak with the local communities, Homero. If we can win them over to the beauty and significance of these forests, they will support us."

Homero smiled gratefully. "You are right. The connection between humans and nature is crucial. Together, we can unleash a force stronger than any threat. Let us embark on this mission in the name of the Monarch butterflies and our planet."

The environmentalists raised their hands in unity, and in this dialogue, the seed of a movement was planted, aiming to protect not only the Monarch butterflies but also the forests of Michoacán.

Night descended over the El Rosario Butterfly Preserve as Monarcho and Luna, burdened by the sad news, floated across the sky. The moon cast gentle shadows on their shimmering wings.

The two butterflies decided to take a pause in a secluded part of the forest to gather their thoughts. In a quiet dialogue between them, Monarcho spoke, "Luna, Homero was a hero. His courage will live on in our wings, but we must also be vigilant. The danger is real."

Luna nodded sadly. "Yes, Monarcho. Our mission is more important than ever. The Monarch butterflies and nature need us. But we must proceed wisely to avoid the same fate."

While the two butterflies lingered in the silence of the forest, threatening sounds suddenly echoed. A shadow approached, and a rough voice said, "You are no strangers, you little fluttering beings. You have seen and heard too much."

A member of the drug cartel emerged from the darkness, eyes cold and sinister. Monarcho and Luna felt the danger in the air. In a desperate dialogue, they tried to plead their innocence, but their words faded in the impenetrable thicket of the threat.

Suddenly, the silence was pierced by a painful scream. Homero Gómez González, the hero of the El Rosario Butterfly Preserve, was silenced by the darkness of the forest. Monarcho and Luna witnessed with horror as the drug cartel silenced the voice of nature.

The forest, once filled with life and beauty, became a witness to a terrible crime. Monarcho and Luna, marked by sorrow and anger, fluttered away, carrying their mission even more resolutely in their hearts.

The story of the Monarch butterflies and their brave protector took a dark turn. Yet, in the wings of the butterflies, the flame of resistance and protection continued to burn. Monarcho and Luna vowed that the Earth would know their story and that the legacy of Homero Gómez González would never extinguish in the wings of the Monarch butterflies.

Oh heavenly Father,

We pray to You for Homero Gómez González, a heroic protector of the Monarch butterflies. Bless his soul, may his sacrifice be recognized and valued. Comfort the grieving hearts.

May the delicate wings of the Monarch butterflies dance in Your light, bearing witness to Your creation. Inspire us through Homero's devotion to be good stewards of nature, for the generations to come and to the honor of Your sacred work.

Through Jesus Christ, our Redeemer, we pray.

Amen.

#Monarch butterflies#Homero Gómez González#El Rosario Butterfly Preserve#Nature conservation#Environmental awareness#Drug cartel#Michoacán#Butterfly lands#Wings of resistance#Luna and Monarcho#Loss#Grief#Environmentalists#Deforestation#Nature crime#Heroic courage#Movement for environmental protection#Shadows of threat#Moonlight#Forest secrets

0 notes

Text

Want to get outside this #EarthDay2023 ? Why not the Art and Nature Festival hosted by the Wildlands Conservancy at the Oak Glen Preserve!

#wildlands conservancy#rivers and lands#art and nature#art and nature festival#oak glen#oak glen preserve#california#redlands#riverside#san bernardino#big bear#runningsprings#art festival#nature festival#yucaipa#nature#education#music#activities

0 notes

Text

"When considering the great victories of America’s conservationists, we tend to think of the sights and landscapes emblematic of the West, but there’s also a rich history of acknowledging the value of the wetlands of America’s south.

These include such vibrant ecosystems as the Everglades, the Great Dismal Swamp, the floodplains of the Congaree River, and “America’s Amazon” also known as the “Land Between the Rivers”—recently preserved forever thanks to generous donors and work by the Nature Conservancy (TNC).

With what the TNC described as an “unprecedented gift,” 8,000 acres of pristine wetlands where the Alabama and Tombigbee Rivers join, known as the Mobile Delta, were purchased for the purpose of conservation for $15 million. The owners chose to sell to TNC rather than to the timber industry which planned to log in the location.

“This is one of the most important conservation victories that we’ve ever been a part of,” said Mitch Reid, state director for The Nature Conservancy in Alabama.

The area is filled with oxbow lakes, creeks, and swamps alongside the rivers, and they’re home to so many species that it ranks as one of the most biodiverse ecosystems on Earth, such that Reid often jokes that while it has rightfully earned the moniker “America’s Amazon” the Amazon should seriously consider using the moniker “South America’s Mobile.”

“This tract represents the largest remaining block of land that we can protect in the Mobile-Tensaw Delta. First and foremost, TNC is doing this work for our fellow Alabamians who rightly pride themselves on their relationship with the outdoors,” said Reid, who told Advance Local that it can connect with other protected lands to the north, in an area called the Red Hills.

“Conservation lands in the Delta positions it as an anchor in a corridor of protected lands stretching from the Gulf of Mexico to the Appalachian Mountains and has long been a priority in TNC’s ongoing efforts to establish resilient and connected landscapes across the region.”

At the moment, no management plan has been sketched out, but TNC believes it must allow the public to use it for recreation as much as possible.

The money for the purchase was provided by a government grant and a generous, anonymous donor, along with $5.2 million from the Holdfast Collective—the conservation funding body of Patagonia outfitters."

youtube

Video via Mobile Bay National Estuary Program, August 7, 2020

Article via Good News Network, February 14, 2024

#united states#alabama#estuary#wetlands#swamp#river#environment#environmental issues#conservation#video#biodiversity#american south#ecosystems#ecology#conservation news#wildlife conservation#ecosystem#conservation efforts#good news#hope#forest#swampco#re#Youtube

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

How people in the USA loved nature and knew the ways of the plants in the past vs. nowadays

I have been in the stacks at the library, reading a lot of magazine and journal articles, selecting those that are from over fifty years ago.

I do this because I want to see how people thought and the tools they had to come up with their ideas, and see if I can get perspective on the thoughts and ideas of nowadays

I've been looking at the journals and magazines about nature, gardening, plants, and wildlife, focusing on those from 1950-1970 or thereabouts. These are some unstructured observations.

The discourse about spraying poisons on everything in your garden/lawn has been virtually unchanged for the past 70 years; the main thing that's changed is the specific chemicals used, which in the past were chemicals now known to be horribly dangerous and toxic. In many cases, just as today, the people who opposed the poisons were considered as whackos overreacting to something mostly safe with a few risks that could be easily minimized. In short, history is not on the pesticides' side.

Compared with 50-70 years ago, today the "wilderness" areas of the USA are doing much better nowadays, but it actually appears that the areas with lots of human habitation are doing much worse nowadays.

I am especially stricken by references to wildflowers. There has definitely been a MASSIVE disappearance of flowers in the Eastern United States. I can tell this because of what flowers the old magazines reference as common or familiar wildflowers. Many of them are flowers that seem rare to me, which I have only seen in designated preserves.

There are a lot more lepidopterans (butterflies and moths) presumed to be familiar to the reader. And birds.

Yes, land ownership in the USA originated with colonization, but it appears that the preoccupation with who owns every little piece of land on a very nitpicking level has emerged more recently? In the magazines there is a sense of natural places as an unacknowledged commons. It is assumed that a person has access to "The creek," "The woods," "The field," "The pond" for simple rambling or enjoyment without personally owning property or directly asking permission to go onto another person's property.

There is very little talk of hiking and backpacking. I don't think I saw anything in the magazines about hiking or going on hikes, which is strange because nowadays hiking is the main outdoor activity people think of. Nature lovers 50-70 years ago described many more activities that were not very physically active, simply watching the birds or tending to one's garden or going on a nice walk. I feel this HAS to do with the immediately above point.

Gardening seems like it was more common, like in general. The discussion is about gardening without poisons or unsustainable practices, instead of trying to convince people to garden at all.

Overall, the range of animals and plants culturally considered to be common or familiar "backyard" creatures has narrowed significantly, even as the overall conservation status of animals and plants has improved.

This, to me, suggests two things that each may be possible: first, that the soils and environments of our suburbs and houses have sustained such a high level of cumulative damage that the life forms they once supported are no longer able to live, or second, that our way of managing our yards and inhabited areas has become steadily more destructive. Perhaps it may be the case that the minimum "acceptable" standard of lawn management has become more fastidious.

In conclusion, I feel that our relationship with nature has become more distant, even as the number of people who abstractly support the preservation of "wilderness" has increased. In the past, these wilderness preservation initiatives were a harder sell, but somehow, more people were in more direct contact with the more mundane parts of nature like flowers and birds, and had a personal relationship with those things.

And somehow, even with all the DDT and arsenic, the everyday outdoor spaces surrounding people's homes were not as broadly hostile to life even though the people might have FELT more hostile towards life. In 1960, a person hates woodpeckers, snakes and moths and his yard is constantly plagued by them: in 2024, a person enjoys the concept of woodpeckers, snakes and moths but rarely sees them, and is more likely to think of parks and preserves as the place they live and need to be protected. Large animals are mostly doing better in 2024, but the littlest ones, the wildflowers and bugs and birds, have declined steeply. It's not because "wilderness" is less; it seems more because non-wilderness has declined in quality.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

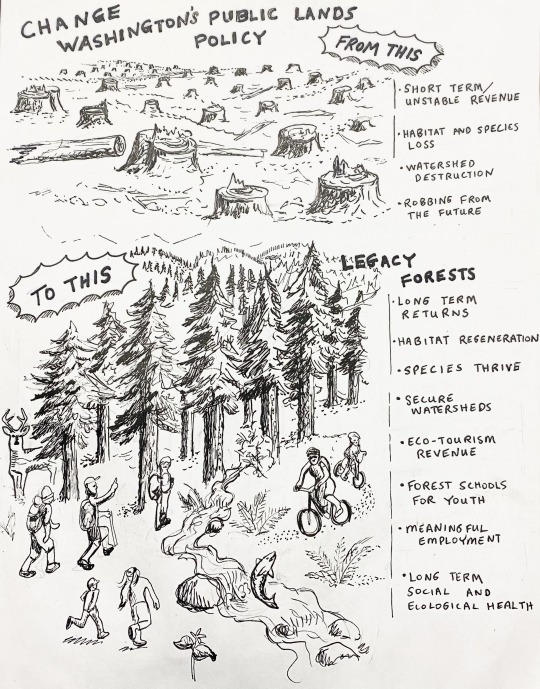

Forests

View On WordPress

#art#cartoon#conservation#DNR#earth#environment#forest schools#forests#future forests#habitat#habitat preservation#inspiration#legacy forests#nature#northwest art#Pacific Northwest#preservation#public lands#river#salmon#timber

1 note

·

View note

Text

September 24, 2022 - NATIONAL SINGLES DAY – NATIONAL PUNCTUATION DAY – SCHWENKFELDER THANKSGIVING – NATIONAL CHERRIES JUBILEE DAY – SEAT CHECK SATURDAY - NATIONAL HUNTING AND FISHING DAY – NATIONAL GHOST HUNTING DAY – NATIONAL FAMILY HEALTH & FITNESS DAY USA – NATIONAL PUBLIC LANDS DAY – SAVE YOUR PHOTOS DAY

September 24, 2022 – NATIONAL SINGLES DAY – NATIONAL PUNCTUATION DAY – SCHWENKFELDER THANKSGIVING – NATIONAL CHERRIES JUBILEE DAY – SEAT CHECK SATURDAY – NATIONAL HUNTING AND FISHING DAY – NATIONAL GHOST HUNTING DAY – NATIONAL FAMILY HEALTH & FITNESS DAY USA – NATIONAL PUBLIC LANDS DAY – SAVE YOUR PHOTOS DAY

SEPTEMBER 24, 2022 | NATIONAL SINGLES DAY | NATIONAL PUNCTUATION DAY | SCHWENKFELDER THANKSGIVING | NATIONAL CHERRIES JUBILEE DAY | SEAT CHECK SATURDAY | NATIONAL HUNTING AND FISHING DAY | NATIONAL GHOST HUNTING DAY | NATIONAL FAMILY HEALTH & FITNESS DAY USA | NATIONAL PUBLIC LANDS DAY | SAVE YOUR PHOTOS DAY

NATIONAL SINGLES DAY

National Singles Day takes place on the Saturday of Singles week in…

View On WordPress

#conservation#dessert#Grammar#NATIONAL CHERRIES JUBILEE DAY#NATIONAL FAMILY HEALTH & FITNESS DAY USA#National Ghost Hunting Day#NATIONAL HUNTING AND FISHING DAY#National Public Lands Day#National Punctuation Day#National Singles Day#paranormal#polaroids#preservation#safety#SAVE YOUR PHOTOS DAY#Schwenkfelder Thanksgiving#SEAT CHECK SATURDAY#September 24

0 notes

Text

I am once again obsessed with @skyscrapergods concept of alicorn ascension.

Just thinking about the rest of the mane six as immortal massive deities.

Applejack, goddess of orchards and agriculture, spreading good harvest of each crop as she walks, turning the seasons with her hooffalls

Fluttershy, goddess of the wild lands and animals everywhere. Wherever she steps, biomes explode into being. Her tears can heal the most grievous of wounds. Her mere presence is what drives the mating seasons of various beasts (as an act of preservation and conservation)

Pinkie Pie, goddess of mirth and joy. Where she walks there is no sadness. She also brings comfort to the grieving with soft reminders of happy memories with their loved ones, not taking their sense of loss from them but merely reminding them of the joy that causes the grief to be so profound, and in so doing, easing it.

Rainbow Dash, goddess of storms and weather. She does not walk the earth but rather the reaches of the sky. The most fickle of the goddesses, the weather changes with her mood as much as for the needs of ponies, and just like she can provide rains in a drought, she can bring storms to calm seas.

And Rarity, most unlike all the rest, goddess of gemstones and craft. She slumbers deep beneath the earth. Her dreams form veins of precious stone and metal, and her nightmares form earthquakes and cave-ins. Her spirit runs through the night, accompanying Princess Luna to provide dreams of inspiration to all those who create with their hands.

(Honestly, I'd love to make a sub-AU of your AU with your permission, credit to you ofc, skyscrapergods. I'm genuinely so obsessed with the concept.)

442 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Things We Care About

Well, Tumblr, 2022 was another big year for speaking up and supporting each other. In the past year, you took action, turned art into activism, and made your voices heard, often in support of others. We’ve analyzed your top tags and posts to determine what mattered to you in the last year.

When Ukraine was invaded, you showed your support. You continue to #stand with Ukraine, create for Ukraine, and honor Ukrainian artists caught in the crossfires.

Throughout the year, you shared many messages of body positivity and encouragement, held 5,879,971 private exchanges with @kokobot (yes, you and kokobot rlly r bestiez), and sent an inconceivable amount of anonymous, personalized messages of reassurance to each other.

You celebrated Pride with plenty of wholesome artistic offerings and showed solidarity with your peers all over the world. You stood up against the Don’t Say Gay bill in Florida and informed each other on how to vote against trans-exclusionary policies across America. When Rebel Wilson and Kit Conner were both pressured into coming out, you supported them, commiserated with them, and came to the defense of anyone who's ever been pressured to do so.

When Mahsa Amini was killed, you spoke out and posted in support of protests in Iran, learning about and spreading awareness of what women, girls, and protestors endure in the name of tradition in Iran.

When Roe v. Wade was overturned, you shared countless resources for those affected by reproductive rights infringement in the US, again turning to art as a means to share stories and ignite action. You commemorated the victims of the Uvalde shooting, saying enough is enough when it comes to gun-related violence in America. You turned your rage into art that inspires and nudged others to make their voices heard at the US polls.

You reminded users that the “civil rights movement isn’t as “ancient” as we’re taught in class,” that Black lives still matter, and always will matter. You celebrated Black Joy and Black Excellence, illuminating stories of resilience in the face of racial injustice.

You celebrated your Indigenous culture and took a stand for the preservation of Indigenous lands.

You continued to be planet-conscious by sharing ideas, resources, and knowledge of mending and making, and celebrated conservation efforts along the way.

And finally, under the continued stresses of COVID, you looked to the future with resilience, turning pain and uncertainty into hope and connection.

And that’s definitely something to be proud of. What will you stand for in 2023?

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy National Bison Day!

Buffalo (culturally and historically correct) / Bison (scientifically correct) were almost driven to extinction, but conservation efforts preserved them. From a treacherous 325 wild bison left to half a million today, we now have a sustainable population.

But they're not back in the numbers they once were--50 MILLION-- and they're not really back the way they were, an ecological keystone species that changed the landscape and fed the people in ways that they never would again.

In fact, that version of the west is pretty much a memory, a former glory impossible to re-create in a world where cattle and cattlemen reign.

That said, there are a handful of organizations that are trying to preserve some land to be somewhat like the old American shortgrass prairie, with some bison fulfilling their roles on those lots. Andrew McKean in Outdoor Life explains.

475 notes

·

View notes

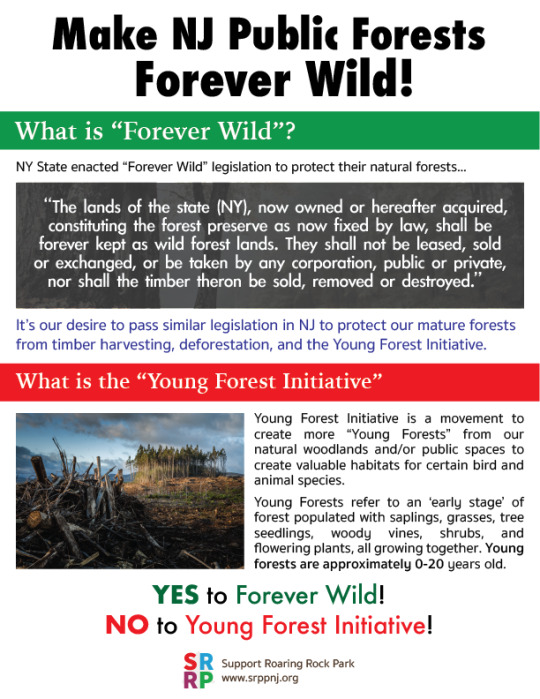

Text

#nj#new jersey#land conservation#wildlife conservation#climate change#climate crisis#land preservation#climate action#hidden

0 notes

Text

Existence Value: Why All of Nature is Important Whether We Can Use it or Not

I spend a lot of time around other nature nerds. We’re a bunch of people from varying backgrounds, places, and generations who all find a deep well of inspiration within the natural world. We’re the sort of people who will happily spend all day outside enjoying seeing wildlife and their habitats without any sort of secondary goal like fishing, foraging, etc. (though some of us engage in those activities, too.) We don’t just fall in love with the places we’ve been, either, but wild locales that we’ve only ever seen in pictures, or heard of from others. We are curators of existence value.

Existence value is exactly what it sounds like–something is considered important and worthwhile simply because it is. It’s at odds with how a lot of folks here in the United States view our “natural resources.” It’s also telling that that is the term most often used to refer collectively to anything that is not a human being, something we have created, or a species we have domesticated, and I have run into many people in my lifetime for whom the only value nature has is what money can be extracted from it. Timber, minerals, water, meat (wild and domestic), mushrooms, and more–for some, these are the sole reasons nature exists, especially if they can be sold for profit. When questioning how deeply imbalanced and harmful our extractive processes have become, I’ve often been told “Well, that’s just the way it is,” as if we shall be forever frozen in the mid-20th century with no opportunity to reimagine industry, technology, or uses thereof.

Moreover, we often assign positive or negative value to a being or place based on whether it directly benefits us or not. Look at how many people want to see deer and elk numbers skyrocket so that they have more to hunt, while advocating for going back to the days when people shot every gray wolf they came across. Barry Holstun Lopez’ classic Of Wolves and Men is just one of several in-depth looks at how deeply ingrained that hatred of the “big bad wolf” is in western mindsets, simply because wolves inconveniently prey on livestock and compete with us for dwindling areas of wild land and the wild game that sustained both species’ ancestors for many millennia. “Good” species are those that give us things; “bad” species are those that refuse to be so complacent.

Even the modern conservation movement often has to appeal to people’s selfishness in order to get us to care about nature. Look at how often we have to argue that a species of rare plant is worth saving because it might have a compound in it we could use for medicine. Think about how we’ve had to explain that we need biodiverse ecosystems, healthy soil, and clean water and air because of the ecosystem services they provide us. We measure the value of trees in dollars based on how they can mitigate air pollution and anthropogenic climate change. It’s frankly depressing how many people won’t understand a problem until we put things in terms of their own self-interest and make it personal. (I see that less as an individual failing, and more our society’s failure to teach empathy and emotional skills in general, but that’s a post for another time.)

Existence value flies in the face of all of those presumptions. It says that a wild animal, or a fungus, or a landscape, is worth preserving simply because it is there, and that is good enough. It argues that the white-tailed deer and the gray wolf are equally valuable regardless of what we think of them or get from them, in part because both are keystone species that have massive positive impacts on the ecosystems they are a part of, and their loss is ecologically devastating.

But even those species whose ecological impact isn’t quite so wide-ranging are still considered to have existence value. And we don’t have to have personally interacted with a place or its natural inhabitants in order to understand their existence value, either. I may never get to visit the Maasai Mara in Kenya, but I wish to see it as protected and cared for as places I visit regularly, like Willapa National Wildlife Refuge. And there are countless other places, whose names I may never know and which may be no larger than a fraction of an acre, that are important in their own right.

I would like more people (in western societies in particular) to be considering this concept of existence value. What happens when we detangle non-human nature from the automatic value judgements we place on it according to our own biases? When we question why we hold certain values, where those values came from, and the motivations of those who handed them to us in the first place, it makes it easier to see the complicated messes beneath the simple, shiny veneer of “Well, that’s just the way it is.”

And then we get to that most dangerous of realizations: it doesn’t have to be this way. It can be different, and better, taking the best of what we’ve accomplished over the years and creating better solutions for the worst of what we’ve done. In the words of Rebecca Buck–aka Tank Girl–“We can be wonderful. We can be magnificent. We can turn this shit around.”

Let’s be clear: rethinking is just the first step. We can’t just uproot ourselves from our current, deeply entrenched technological, social, and environmental situation and instantly create a new way of doing things. Societal change takes time; it takes generations. This is how we got into that situation, and it’s how we’re going to climb out of it and hopefully into something better. Sometimes the best we can do is celebrate small, incremental victories–but that’s better than nothing at all.

Nor can we just ignore the immensely disproportionate impact that has been made on indigenous and other disadvantaged communities by our society (even in some cases where we’ve actually been trying to fix the problems we’ve created.) It does no good to accept nature’s inherent value on its own terms if we do not also extend that acceptance throughout our own society, and to our entire species as a whole.

But I think ruminating on this concept of existence value is a good first step toward breaking ourselves out first and foremost. And then we go from there.

Did you enjoy this post? Consider taking one of my online foraging and natural history classes or hiring me for a guided nature tour, checking out my other articles, or picking up a paperback or ebook I’ve written! You can even buy me a coffee here!

#nature#natural history#ecology#wildlife#animals#environment#environmentalism#conservation#existence value#deep ecology#science#scicomm#environmental philosophy#climate change

556 notes

·

View notes