#gzhi

Text

Tonight, GZHI at Abstand

Tonight GZHI, trio formed by Novatron’s Itta and Tatsumi together with Adam at bass. They are truly amazing don’t miss them!

0 notes

Text

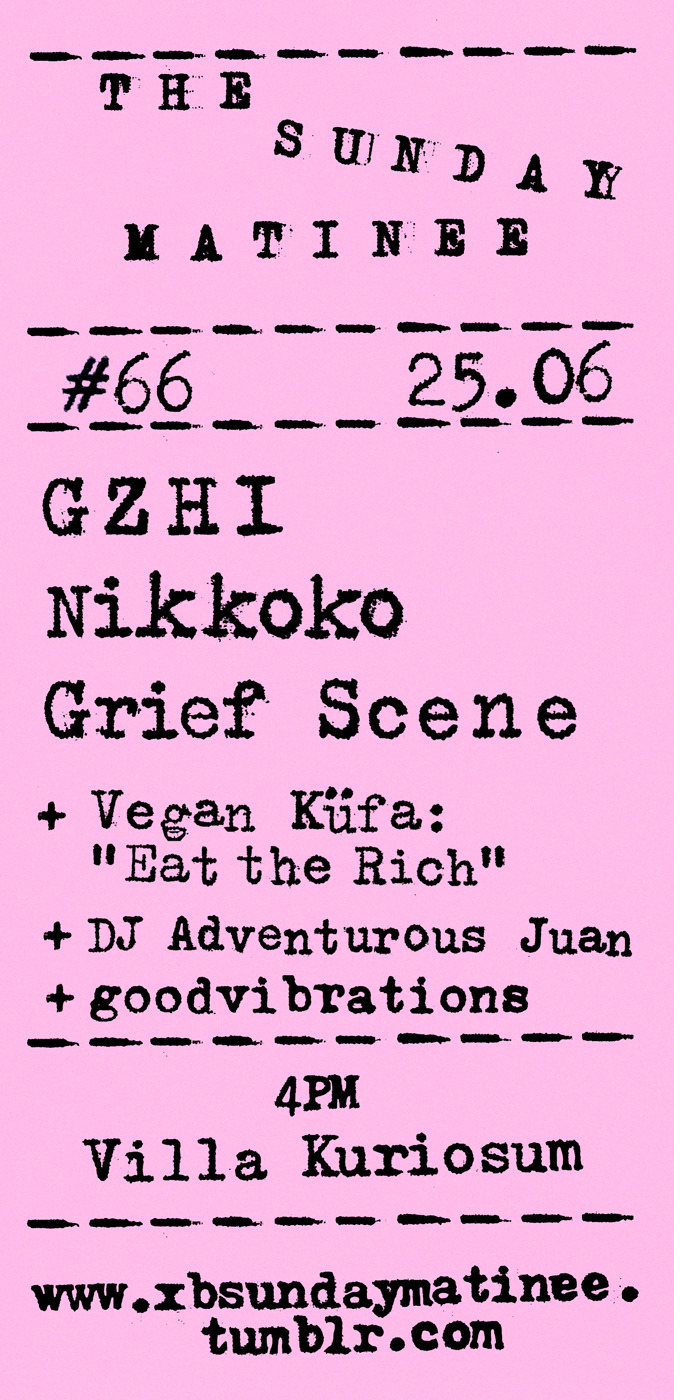

Sunday Matinee #66 on June 25th... and bro, it’s gonna be OPEN AIR!

On Sunday 25th of June it’s Sunday Matinee #66!

also known as The First Open-Air edition of the season.

On stage from 4PM and in no particular order:

Grief Scene is a indie trio composed by Berlin’s usuals: the people you’ve already seen in other bands and you’re like: “Holy schnapps! I’ve seen that guy already!” ...and a few minutes later you pleasantly find yourself thinking:

“Nice tune... This guy! When does he find time to do the dishes, or buying groceries? I’ve seen him play drums with that other band and has that other solo experimental-ambient (or industrial?) thingy project, and here’s playing indie guitar music with a surprising vibrato singing! Jeez! I grew moustache for a whole month after seen him play last year at a open-air Sunday Matinee”

…or: “I’ve seen her playing in... in?… Grußedamen! why I can’t bloody remember %&$§?” Or again, “oh! That’s the guy doing paradiddle on instagram! I saved that video willing to practice along, but I still haven’t.”

Check them out and singalong Grief Scene pop tunes as in this super funny video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bfsCl92Ho-E&ab_channel=GriefScene

https://www.facebook.com/griefscene/

https://griefscene.bandcamp.com

https://instagram.com/griefscene

https://open.spotify.com/artist/5jrEWAStN1xMQwMHDR1mnl

Nikkoko (aka @JUNG_KNIK on the instagram) is our guest of honour on tour from Switzerland land of DADA and Cabaret Voltaire.

Nikkoko is the solo act of Nik.

Nik-plays-the-sax

And

Blows-all-he’s-got

From-his-lungs

To-his-horn

You’ll get minimal sounds, experiments, loops, glitches, free-jazz, love and anarchy.

https://www.instagram.com/jung_knik/

https://nikokko.bandcamp.com/track/schoona

https://www.nikolajangross.ch/

GZHI

Tatsumi Ryusui is back at the matinee and we cannot wait for it!

Probably the artist who played the most number of editions at our events (slightly ahead of Yury and DuChamp in terms of presences).

Each time under a different “spell” and/or part of different ensembles, Herr Ryusui will join this edition of The Sunday Matinee with GZHI: a fresh new project out of Berlin composed by Tatsumi on electric guitar, Adam Goodwin on electric bass and Itta Nakamura on drums. Adam and Itta too have been seen a bunch playing at the matinee through the years.

GZHI’s music oscillate between noise, industrial and doom, but not exactly.

https://gzhi.bandcamp.com/

Plus:

—>>> DJ Adventurous Juan will play J-pop, Indie, Latin and more.

—>>> Food will be provided by Eat The Reach

**2G rules no longer apply in Berlin, however, we would be very glad if you test yourself before coming, and if you have cold-like symptoms we suggest you having a cup of tea and stay put! thank you**

**The Sunday Matinee is smoke free, children friendly, wheelchair accessible**

**Check out the Matinee double cassette mix tape here. Copies are still available and can be purchased at our events:

https://thesundaymatinee.bandcamp.com/album/the-sunday-matinee-sampler-1

To sign up for the newsletter and more info, please visit:

https://xbsundaymatinee.tumblr.com/

Villa Kuriosum

Scheffelstraße

21

10367

Berlin

#DJ Adventurous Juan#eat the reach#kufa#küfa#berlin#berlingigs#xbsundaymatinee#the sunday matinee#gzhi#nikkoko#nikokko#tatsumi ryusui#adam goodwin#itta nakamura#punk#diy punk#free jazz#berlin shows#diy shows#JUNG KNIK#grief scene#open air concert#sunday concert

1 note

·

View note

Text

快|三精准计划导师qq-

快|三精准计划导师qq-(网站g866.cc)快|三精准计划导师qq--快|三精准计划导师qq-GZhIS

0 notes

Text

Кировская ГЖИ обучает

Кировская ГЖИ обучает активных жителей многоквартирных домов http://vybor-naroda.org/lentanovostey/230315-kirovskaja-gzhi-obuchaet-aktivnyh-zhitelej-mnogokvartirnyh-domov.html

0 notes

Text

Black Snake Discourt

The Black Snake Discourse

by Rongzom Chökyi Zangpo

The specific views and conducts of the higher and lower vehicles may be understood, in short, as follows. Their various views are posited based on the appearance of bodies, environments, and spheres of activity, all of which can be subsumed under body, speech, and mind. However, as to the question of whether things do or do not appear: No matter if you are an individual who upholds the various textual traditions, or someone ranging from a beginner up to a bodhisattva on the tenth bhūmi, there is no debate. This is because no one can exaggerate or denigrate direct, immediately experienced appearances. Therefore, all debates about this arise from the status of the defining characteristics of appearances.

In brief, there are five positions. Let us first offer an example. Consider, by way of analogy, a black snake reflected in water.

One type of individual regards this as an actual snake and, driven by fear, actively seeks to get rid of it.

One type of individual recognizes the snake as a reflection. Even though they know that it is not actually a snake, they see the reflection as capable of harm and, therefore, exert themselves in applying a remedy with skilful means.

One type of individual recognizes the snake as a reflection, without the material support of the coarse elements and, therefore, lacking the ability to perform any action. However, driven by the force of previous anxiety, this individual is unable to touch or destroy it.

One type of individual realizes the snake is a reflection and therefore incapable of performing any action. But, in order to swiftly free themselves of anxious thoughts, such individuals rely on ascetic discipline to touch and destroy the reflection.

One type of individual knows the snake is a reflection and therefore has no thoughts of rejection or acceptance, and does nothing whatsoever.

In this way, the philosophical tenets of the various Buddhist vehicles correspond with the meaning of the previous examples.

The first of these is the tradition of the Śrāvakas. The Śrāvakas posit that phenomena, such as suffering and its sources, exist both relatively and ultimately, and exist as substantial entities. This belief compels them to see phenomena as genuinely real and to accept and reject them. This is like seeing the snake’s reflection as real and trying to get rid of it. In this system, among the four kinds of existence, the Śrāvakas affirm three: “ultimate existence,” “relative existence,” and “the substantial existence of both.”

The second example corresponds to the Mādhyamikas of the Mahāyāna, since, for them, appearances are not substantially established but are like illusions. However, just as illusory poison can perform a function, thoroughly afflicted phenomena are likewise capable of harm if they are not embraced with skillful methods. When they are so embraced, phenomena perform beneficial functions. Because phenomena substantially exist at the relative level, the Mādhyamikas assert that they should be accepted and rejected. This is like asserting that although the snake is a reflection, its ability to perform a function substantially exists. Of the four kinds of existence, this system negates “ultimate existence” but retains “relative existence” and “imputed existence.”

The third example corresponds to the outer ascetic tantras, Kriyā and Yoga. As all apparent phenomena are illusion-like, they are utterly without substance. Despite phenomena posing no fault or problem, through the force of previous anxiety, yogis in this tradition dare not act themselves, but they are able to summon an external hero. This is like knowing the snake’s reflection to be harmless, yet still being unable to touch it. In this system, among the four kinds of existence, “ultimate existence” and “substantial relative existence” are both refuted. However, “imputed relative existence” is retained. On top of asserting merely this system of the commonly held two truths, proponents of this tradition know there is no substantial relative existence. Through this system, one first attains, to a small degree, the view of equality in which the relative and the ultimate are realized to be inseparable.

The fourth concerns the view of the inner tantras of Mahāyoga. Having mostly realized that all thoroughly afflicted phenomena are like illusions, and in order to swiftly put into practice the view of equality, the yogi engages in wonderous conduct. This is like swiftly eliminating fear for the mere reflection of the snake by practicing asceticism to destroy it. In this system, any grasping to imputed relative existence is extinguished even further, and these individuals are mostly free from grasping which views the truth dualistically. The yogis of this system attain, to a middling degree, an understanding of the inseparability of the two truths.

The fifth relates to the view of the Great Perfection. Here, as everything is like an illusion, the proponent realizes that every action, such as rejection or fear, or actual destruction, arises from a view that clings to things as real. As phenomena are illusion-like, the yogi realizes they are without any basis to act upon; one neither rejects nor strives for anything whatsoever. In this system, the understanding of the illusion-like reaches its pinnacle through the awareness of the absence of defining characteristics of appearance. The yogi is liberated from even the subtlest clinging to ultimate or relative truths and is thereby liberated from any view whatsoever. This is termed the “view of the inseparability of the ultimate and relative, the realization of equality itself.”

Actual, direct appearances arise through the force of latent tendencies and, therefore, do not immediately subside. Clinging, on the other hand, arises from adventitious, mistaken conceptions, and is easily reversed. Furthermore, clinging comes from grasping at defining characteristics, and this comes from a view of real entities. If these three concepts are overturned, a dualistic view of the truth will not arise, even if the appearances of intrinsically real entities are not reversed.

Here, some might say, “The Mādhyamaka scriptural tradition does not ultimately divide the truth into two, and the Secret Mantra scriptural traditions do not refute appearance.” To this, we would answer:

Individuals might evaluate objects of knowledge while keeping in mind that the defining characteristics of the two truths are truly established, but by doing so, they will never be able to abandon dualistic thinking. When they evaluate the position, “ultimately, the two truths are indivisible,” even the assertion that the relative truth exists as mere illusion has not been relinquished due to their strongly held belief in true establishment. Therefore, even when establishing the nondual nature of reality, their thinking arises dualistically.

When evaluating the statement, “relatively, like an illusion,” we can see that “illusion-like” refers to conceptual elaborations, since the imputations of ultimate existence made by the Śrāvakas and Yogācārins have been pacified. However, “illusion-like” does not mean that phenomena are devoid of substantial functionality on a relative level.

Here, even at the time of such evaluation, directly focusing on defining characteristics that are relatively established as substance, it is then claimed that “these are not actually established as real entities.” Therefore, the mind at this moment has not even given up the two systems.[1] This means that appearance—a property-possessor (Skt. dharmin, Tib. chos can)—is posited as an instance of characteristics (Skt. dṛṣṭānta, Tib. mtshan gzhi). As long as there exists in the mind the notion of being free from the properties or the conceptual elaborations of the instance, and as long as the property-possessor is perceived to exist as mere illusory appearance, then the obsessive mind that grasps to the defining characteristics of appearance has not been reversed. Someone like this cannot be said to possess the view of great equality.

Consequently, investigating objects of knowledge by focusing the mind on the distinction between the two truths was taught as an antidote for those people with excessive, obsessive clinging to real entities. However, in the very nature of phenomena, there are no dual characteristics. Whosoever reverses grasping to characteristics is free from this obsessive clinging. When one experiences no craving or wishful thought toward anything that appears, this is called “the view of great equality.”

There might be a further question: “Is not mere appearance itself relative?” This was already explained above with regard to any person who believes appearance to be relative and that freedom from conceptual elaborations regarding this is the ultimate. For the mind that does not believe in the reality of the two truths, the scriptures teach that to ask whether the truths are one or two is analogous to asking whether the son of a barren woman is blue or white.

Someone might then ask: “Well then, what does your tradition assert?” We merely refute your wrong views without at all establishing any point of our own. This, conventionally speaking, is called “the view of great equality,” but there is no clinging whatsoever to it as a metaphysical view.

| Translated by Patrick Dowd, 2021

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The "shoot" in my username it's from "photoshoot" 👀 why? No idea. I needed a name and that's what my brain found (and I never changed it) . So no, it's not from gunshot or something similar. . O "shoot" do meu username é de "photoshoot" (sessão de fotos). Pq? Não sei, foi s única coisa que veio na minha cabeça no momento (e eu nunca mudei). Não é de "gunshot", recebo muito essa pergunta de estadunidenses, pq "shoot" pode ser tiro 👀🤦🏾♀️ #kyliejenner https://www.instagram.com/p/CENe91-gZHI/?igshid=1msb5rmw7qnm0

13 notes

·

View notes

Video

Boeing 737-86J ‘F-GZHI’ Transavia France by Alan Wilson

Via Flickr:

c/n 36120, l/n 4358 Built 2013 Seen arriving on flight TO3069 / TVF72ZL from Casablanca. Paris Orly Airport, France 9th June 2019

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

u think my url is nu tong zhi? no it’s nut on gzhi my friend gzhi

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tibetan Tantric carpet from the mid-20th century with a pictorial design of a flayed man. The macabre motif sits atop a deep blue field. Employed by Vajrayana Buddhists as seats of power during the practice of esoteric rites associated with protective deities. It shows a flayed man (Tibetan: g.yang gzhi) with "artery patterns" surrounded by his butchered bones, carefully arranged. The peculiar imagery depicted in these rugs symbolize the power of detachment from one's body, representing the ultimate achievement attainable by the advanced practitioners of Buddhist ritual meditation.

0 notes

Photo

जयश्री राधे कृष्णा राधे कृष्णा राधे गोविंद. भजो राधे गोविन्द राधे गोविन्द राधे गोविन्द, रटो राधे कृष्णा राधे कृष्णा राधे गोविन्द, जयश्री राधे कृष्णा राधे कृष्णा राधे गोविंद..🙏 https://www.instagram.com/p/CJXR-R-gzhI/?igshid=vblj6kiqzk5d

0 notes

Photo

I'm gay; I'm third sex kind of night. #OBGMNL ft Shaid 🍻🥃 SAYA-SAYA, WALANG UUWI NANG BUHAY!!! 😂😂😂 https://www.instagram.com/p/B441aC-gZhI/?igshid=1wyuuodsxwbol

0 notes

Photo

Oral Instructions on the Practice of Guru Yoga (Part 5)

by Chogye Trichen Rinpoche

THE VIEW: THE SINGLE ESSENCE

The final result or fruition (drebu; ‘bras bu) of the View within all the schools of secret mantra (sang ngak), whether we call it the Indivisibility of Samsara and Nirvana, Mahamudra, or Dzogchen, is the same; they are of one single essence (ngowo chig; ngo bog cig). If they were not of the same essence, we would have to speak of Sakyapa realisation, of Kagyupa realisation, and so forth. Then if we took Sakya empowerment, we would not get the Kagyu result. But it really is not like this.

The names of the Views are different, but the meaning behind them is not different. This is because the final result of all the vehicles of secret mantra (drebu sang ngak kyi thegpa; bras bug sang sngags kyi theg pa) is to realise the nature of one’s own mind. One who realises this may express it in different ways, as Mahamudra or Dzogpa Chenpo, and so on.

The only real difference is that the different schools have different methods, such as methods of introducing the nature of mind, methods of practising the path, and so on. Once you know the real meaning (don) of the View (tawa; Ita ba), they are the same in essence (ngowo chig).

For this reason, I can teach according to the Nyingma tradition, according to the Sakya, or by one of the other ways of explanation. From the master’s experience in practice, he has found that once the real meaning is known, these teachings are not really very different.

I do feel that Sakya Pandita’s words are truly wonderful when he says, “My Mahamudra is the experience of the descent of primordial wisdom at the time of empowerment.” Sakya Pandita means that Mahamudra is not a doctrine or tenet belonging to the Sakya, Kagyu, or Gelug. “Mahamudra” refers to the one who recognises the true nature of mind. This Mahamudra is introduced through the power of the lineage of experiential realisation (thugdam nyam zhay kyi gyupa; thugs dam nyams bzhes kyi brgyud pa), through the power of the ultimate blessing lineage (jinlab don gyi gyupa; byin rlabs don gyi brgyud pa).

Whether we speak of the Inseparability of Samsara and Nirvana (tawa khordey yermey), or of naked awareness (rig pa jen pa) ; or whether we refer to Mahamudra (chagya chenpo), or to recognising awareness (rigpa rang ngo shepa), the meaning is the same for them all, they are of a single essence (ngowo chig).

Some traditions may introduce more generally with few words, some may introduce very nakedly with many explanations, but their intention is the same. All of these teachings are speaking of the same point, to recognise the true nature of mind. The words are different, but if you really know the meaning, it is the same.

For example, sometimes Dampa Rinpoche meditated on the View of the Inseparability of Samsara and Nirvana (tawa khordey yermey), sometimes he meditated according to the View of Dzogchen. For him, the result of these was the same realisation of the View.

The introductions to the nature of mind (ngotro) and sustaining the View (tawa kyongwa; Ita ba skyong ba), which I received from Khyentse Chokyi Lodro according to the Dzogchen teachings, were the same in essence as the introductions and instructions I received from Dampa Rinpoche when he would explain these teachings according to the Sakya tradition. There was no real difference between them.

Different traditions may emphasise different stages of meditation (gom rim). Some put more emphasis on the earlier stages, some on the later stages of meditation practice, according to the needs of beings. The methods of introducing and of explanation may differ in some ways, but once you understand it, they all introduce the same fundamental Buddha nature (zhi desheg nyingpo; gzhi bde gshegs snying po).

In the philosophical schools of Buddhism, the Views of the different traditions are debated. Students of philosophy try to distinguish their View from that of other schools. But, it is not like that in the practice lineage (drub gyu). All schools of the practice lineage arrive at the same essence (ngowo chig), and express it in very similar ways.

Sakya Pandita said that he had a special way of understanding the ground (zhi), the path (lam), and the fruition or result (drebu). In the Sakya tradition of explaining the View, it is said that the ground, the path, and the result are inseparable (yermay), meaning that they share the same essence (ngowo chig).

However, these special words of Sakya Pandita are not based on theoretical understanding or written treatises. They can only be understood through one’s own experience of meditation practice. This is because the ground, path, and result (zhi lam dre sum) are only the same for one who has recognised emptiness, the true nature of mind (sem nyid).

Practicing Guru Yoga Throughout the Day and the Night

KYAB NAY KUN DU LA MA RIN PO CHE

DRIN CHEN CHO KYI JE LA SOL WA DEB

NYAM MAY KA DRIN CHEN GYI LHUG JE ZIG

DI CHI BAR DO KUN TU JIN GYI LOB RANG SEM

RANG NGO SHAY PAR JIN GYI LOB

Precious Guru, embodiment of all refuges,

Greatly kind lord of Dharma, to you I pray.

Unequalled in your kindness, look upon me with compassion,

Bless me in this life, at death, and in the bardo.

Bless me to recognise the essence of my own mind.

This is a traditional four-line prayer often chanted during Guru Yoga practice. I have included a fifth line for those who wish to pray for blessings to be able to recognise the true nature of mind. It is a prayer one can add to one’s practice of Guru Yoga at any time. It is very short, and has all the key points within it so, night and day, you can rely on this prayer for your practice of Guru Yoga.

When we chant this praise, as it belongs to the Vajrayogini tradition, we visualise the Guru in the form of Buddha Vajradharma, red in color. If one is practicing the Hevajra tradition, one visualises the Guru as Buddha Vajradhara, blue in colour. One may visualise the Guru in whatever form is appropriate to one’s practice. Visualise the Guru while you supplicate, and then dissolve the Guru into light, which is absorbed into your heart. Through this, you merge your mind with the mind of the Guru. Having dissolved the Guru into you, the Guru no longer has any form, but you are merging with his wisdom mind (thug gong; thugs dgongs).

This prayer includes all the sources of refuge, the Three Jewels of Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, and the three roots of Guru, Deity, and Dharmapala. Everything included in the Guru, the jewel that embodies all.

This four-line prayer is very profound. I have added a fifth line in order for practitioners of to pray to the Guru for wisdom. Really, it is a prayer that may be used by followers of any tradition of secret mantra (sang ngak). If you wish to pray elaborately, you can just change one line of the prayer slightly, in order to pray to each of the sources of refuge individually, leaving the other three lines the same. In that way, you can pray to the Three Jewels and the Three Roots one by one.

If you wish to do so, then, following from the verse as it is written here, you recite the verse again, praying “YI DAM KUN DU LA MA RIN PO CHE”, “Precious Guru, embodiment of all deities”; then, thirdly, you would pray “CHO KYONG KUN DU LA MA RIN PO CHE”, “Precious Guru, embodiment of all Dharmapalas”, and so on. This is how to pray to the Guru as embodying the three roots one by one. In the same way, you can add the word “SUNG MA” for the guardian deities, and then “KHAN DRO” for the Dakinis, and so on.

Similarly, for the Three Jewels, you can say “SANG GYE KUN DU LA MA RIN PO CHE”, “Precious Guru, embodiment of all Buddhas”; then the same with “CHOS KUN DU…” for the “Dharma” and “GEN DUN KUN DU…” for the “Sangha”. When you chant each verse, call to mind the spiritual qualities of each of the sources of refuge, and consider how these qualities are embodied in the Guru. This is the elaborate way to meditate on the qualities of our Gurus with a single verse.

There is another a very famous four-line prayer of Guru Yoga that may also be used day and night for the practice of Guru Yoga. The verse below is generally chanted at the beginning of a session of meditation, while the verse above that we have already discussed comes from the section on Guru Yoga. Both may be chanted at any time throughout the day and the night.

It is said that you may visualise the Guru above your head in the daytime, or in your heart at night, such as at the time of going to sleep. This is a special instruction. Either of these visualisations is also appropriate at any time. In connection with this visualisation, you may recite the four-line prayer of Guru Yoga.

Supplicate the Guru with heartfelt longing and devotion. Generate faith in the immeasurable qualities of the Guru and the Enlightened Ones. If you wish to gain more benefit from Guru Yoga, recite a short supplication prayer and do the prescribed practice as often as you can. Receiving the blessings of the Guru and remembering the true nature of mind are practices that can be performed continually, day and night.

Glorious root-Guru, precious master,

Please be seated on the lotus throne above my head.

Accept me through your immense kindness,

And bestow the siddhis of your body, voice.

During the practice of Guru Yoga, first generate faith (depa; dad pa) and devotion (mogu; mos gus) while offering prayers and supplications. The best way to receive the blessings that introduce the true nature of mind is to give rise to faith in the Guru. Through faith, you can have an experience of emptiness, the true nature of mind. Pray again and again to the Guru with intense, fervent devotion (mogu dragpo). Then dissolve the Guru and lineage Gurus into your heart. As you do this, merge your body, speech, and mind with those of the Guru and lineage masters.

Now rest your mind in emptiness, remaining without grasping. Within emptiness, clear luminosity (osal) arises through the power of blessings. As it arises, you are able to apply the Guru’s introduction, recognise it, and continue on with the sustaining of the View (tawa kyongwa; Ita ba skyong ba). This is the essence of the practice of Guru Yoga.

ALL EXPERIENCE IS THE PLAY OF THE GURU

For your practice of Guru Yoga, it will be a great enhancement for sustaining the View (tawa kyongwa) if you are able to regard everything you see and experience as the display of the Guru’s body, speech, and mind. Understanding all experience to be the play of the Guru allows us to take Guru Yoga as the path. As we unite with the Guru’s body, speech, and mind in Guru Yoga, all that we see and experience is included within our View, within the recognition of the empty essence (ngowo tongpa).

The most precious teaching of the Dharma is the introduction to the View of the true nature of mind. This teaching is not something that we can grasp or comprehend through making great efforts. Once we receive the teaching, its meaning will naturally occur through our practice of Guru Yoga, just as cream naturally rises to the top of milk. The pure essence (dangma; dwangs ma) of your mind, clear luminosity (osal), will naturally emerge from your Guru Yoga practice of mingling with the Guru’s mind, as a pure essence naturally separates from an impure sediment.

While the View does arise naturally, we need to induce or assist this process by purifying our minds and practicing pure vision. In Guru Yoga, the practice of pure vision (dag nang) means to regard everything we experience as the play of the Guru. Everywhere we look we are seeing the face of the Guru, everything we feel is the heart of the Guru, everything we touch is the Guru’s body, everything we hear is the Guru’s speech, and so on.

When we join this way of experiencing everything with the practice of merging with the Guru’s awareness wisdom (rigpai yeshe) within the recognition of the View, this is the way to practice Guru Yoga throughout the day and the night. As we learn to remain with the View, everything will begin to arise as the play of the Guru’s wisdom. This has similarities with the creation stage, where everything is a manifestation of the deity.

As Tilopa said to Naropa,

“If you can understand everything you experience

To be the play of the Guru,

This is the practice of Guru Yoga.”

In practicing Guru Yoga, some may chant the Guru’s mantra, and some may chant verses of praise such as the one we have just described. If you do not wish to supplicate the Guru in the elaborate way just described, simply recite the five lines by way of supplication. Then dissolve the Guru into your heart, and merge your body, speech, and mind with those of the Guru.

Dissolving the blessings of the Gurus into yourself, now unify with the Guru’s mind. Your mind and the Guru’s mind merge indistinguishably, so that they are non-dual with one another. Let the View be sustained (tawa kyong; Ita ba skyong) for as long as you are able to remain with it. This is the most important point of Guru Yoga. Once you have learned this point well, you are on the right path. It is difficult to get on the right path, but once we do find the right path, everything will go very smoothly. This is known as taking the Guru’s blessings as the path (jinlab lama’i lam khyer; byin rlabs bla ma’i lam khyer).

SUMMARY OF THE PRACTICE OF GURU YOGA

In brief, we should understand our root Guru to embody the four Kayas of the Buddha’s enlightened body, speech, mind, and wisdom. The Guru is the Nirmanakaya, Sambhogakaya, Dharmakaya of the Buddha. While we were not able to meet the Buddha in person, we have met the root Guru. Thus his kindness toward us personally is even greater than that of the Buddha. As explained, the Guru embodies every object of refuge, every enlightened quality. It is said that if a disciple supplicates the Guru constantly in this way, realisation will definitely be born in his or her mind.

After supplicating the Guru, all phenomena dissolve into the Guru and the Guru dissolves into you. Merge your body, speech, and mind inseparably with the enlightened body, speech, and mind of the Guru. This is like pouring water into water.

Continue to mingle your body, speech, and mind with the Guru and rest in the recognition of awareness. Merge your recognition of awareness with the Guru’s enlightened awareness. Just as there is the ultimate taking of refuge, where we dissolve the refuge objects into our heart and rest without grasping, so the practice of uniting with the Guru’s wisdom mind in the View is called the ultimate Guru Yoga (don gyi lama’i naljor).

If you practice Guru Yoga in this way, you will be able to recognise and sustain the recognition of clear luminosity. In the beginning, our recognition of clear luminosity may only last for a brief moment. We need to recognise again and again, hundreds or even thousands of times a day, while continuing to endeavour in supplicating the Guru and merging with his awareness.

Through the practice of Guru Yoga, our moments of recognition will gradually become more and more sustained. Through practice, the clear luminosity that is present in between two thoughts will arise spontaneously and begin to be naturally sustained. In this way, the practice of Guru Yoga will enhance our recognition of awareness, and our recognition of awareness will enhance in turn the blessings of the practice of Guru Yoga. The two practices will support and complement one another.

The practice of Guru Yoga is the most important means to be able to continue beyond our initial recognition of the View. Through blessings, and by uniting with the Guru’s mind, we mix our practice of sustaining the view (tawa kyongwa; Ita ba skyong ba) with all that we experience. By doing this, our recognition of awareness will last longer and become more stable. This is the key point.

Practicing this way, we will come to be more at ease. Everything will seem effortless, without hardship.

FINAL ADVICE

We must remember to be mindful of whatever teachings and precepts we have received and taken. This is drenpa, meaning mindfulness or remembering.

Maintaining mindfulness is extremely important. One important meaning of mindfulness is that whatever instructions have been given to us by the Guru must be kept clearly in mind.

Shezhin, which means watchfulness or noticing, takes note of whether we are conducting ourselves properly or improperly. Whatever the Guru has taught us must be tested, checked and verified through our own experience. This is shezhin, observing carefully.

Another extremely important point is the question of the lineage one receives and practices, as Milarepa emphasises in his teachings. In the presence of a true lineage, there is the continuity of blessings passed down through the lineage. And of course, the blessing also depends on oneself, on the practitioner. If one has pure conviction and pure devotion, then one is certain to receive the blessings of the lineage. Receiving the blessings depends on one’s own faith and pure vision, rather than simply depending on the teacher. Even if the master is a great Buddha, if the disciple lacks faith, what benefit is there?

One must resolve with certainty that all of our Gurus and all of the Enlightened Ones are condensed into (chig dril) a single one, appearing in the form of the Guru as described in our practice, and do the visualisation of the Guru Yoga.

Also, from time to time, remember to dedicate the merit of your practice. This will prevent all the merit and blessings you have received from being destroyed, and will help you to progress in the practice.

Ultimately, although we have the true nature of mind within us, some of us may resemble burnt seeds; without enough faith, it is difficult to accept the nature of mind and to recognise it. It is quite simple, but some people have a hard time accepting it because it seems too simple! Lacking faith, we do not accept and recognise the nature of mind, our own awareness wisdom (rang rigpai yeshe) within us, even if it is pointed out to us. Once we have faith, we are like a seed which will bear fruit; all the spiritual qualities can unfold from within.

The pure meditators first learn and gain knowledge, and then they clarify all their doubts and all their accepting and rejecting, progressing through contemplation and reflection, until they come to understand the words and oral instructions of their teacher through their own experience. This is the traditional way in the Sakya tradition. Finally, the yogi will find all the qualities of the teacher arising within him or herself, and these qualities will just go on increasing and increasing.

My principal Gurus for the teaching of the lineage of ultimate meaning (don gyu; don brgyud) are: Dampa Rinpoche, Zhenpen Nyingpo; Zimog Dorje Chang; Jamyang Khyentse Chokyi Lodro; Lama Ngaglo Rinpoche; and Shugseb Jetsunma. Among all of them, the most detailed teachings I received were from Dampa Rinpoche. There was no contradiction, nor any major difference, between what I received from any one of them. Their introductions to recognising the true nature of mind and how to sustain this recognition shared the same single essence (ngowo chig). While the methods of introducing varied somewhat, once you recognised the View they were introducing, you would see that it is the same.

The final advice that I received from all of these great masters was also the same: “You must be very diligent. If you are not diligent in your practice, not so much will happen. If you are diligent, you will definitely receive blessings and get results.” The final advice of my Gurus was to put a lot of energy and attention into practice.

As the great yogi Drukpa Kunleg said before the Jowo Shakyamuni statue in Lhasa, “Before, you and I were the same. You were very diligent at your practice, and became a Buddha. I have not been diligent, and I am still an ordinary sentient being. Therefore, I prostrate to you.” It is also like the final instruction of Jetsun Milarepa to his disciple Gampopa.

Milarepa told Gampopa that he had one final instruction to impart to him. They went to a high mountain place, with a vast view. When they reached there and Gampopa supplicated respectfully, Milarepa lifted his cotton skirt and showed Gampopa his bottom. It was callused like leather, from his years of sitting day and night in meditation on the stone floors of caves. Milarepa told Gampopa, “This is my final teaching. You must be diligent, just as I have been.”

As this was the final teaching of my Gurus to me, I feel that it is sufficient for my disciples. Now you have received all of the oral instructions (men ngag). It is up to you to apply them. I have asked my disciples to translate my oral instructions of the teachings on Parting from the Four Attachments, as well as those regarding the Vajrayogini practices.

You have the teachings, but it is up to your practice whether they will bear fruit. Try to remain mindful of the Guru’s oral instructions (men ngag). Study them and apply them at all times. Samaya, the sacred commitment we share with our Gurus, is maintained through faith in the Guru, and by purifying obscurations and receiving blessings. Realisation is gained through uniting this with practice.

I myself have nothing personally to be proud of, though I do feel very fortunate that I have received this kind of lineage from such highly realised masters. These are very powerful, unbroken blessing lineages that have produced realisation down to the present time. I do feel quite wealthy when it comes to lineages.

I also feel that we are all very fortunate. Although I am an ordinary being, I have had Gurus such as Dampa Rinpoche, Zhenpen Nyingpo, Khyentse Chokyi Lodro, and Zimog Rinpoche. I feel we are all very fortunate, which is why I am always saying to you that when Dampa Rinpoche gave the empowerments of the Collection of Tantras (gyude kuntu), during the descent of blessings (jinbab; byin babs), I definitely experienced the stream of the lineages of blessing. This stream of blessings is with us, and this is why we are fortunate and have reached the path.

#buddha#buddhism#buddhist#bodhi#bodhicitta#bodhisattva#compassion#dharma#dhamma#enlightenment#guru#khenpo#lama#mahayana#mahasiddha#mindfulness#monastics#monastery#monks#path#quotes#rinpoche#sayings#spiritual#teachings#tibet#tibetan#tulku#vajrayana#venerable

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

TIBETAN BUDDHIST MEDITATION - THE DHARMA OF THE ADAMANTINE MYSTERY

====================================================

Palestra e Curso sobre a Meditação Budista Tibetana das linhagens Nyingma,Dzogchen e Kalachakra

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- TÓPICOS DA PALESTRA : Os Mistérios do Planalto Tibetano e as suas heranças Atlantes *** *** A Chegada do Budismo no Tibete e a sua fusão com o Lamaísmo BON,o Tantra e o Vedanta Hinduísta *** Os Mistérios Esotéricos da Tradição NYINGMA: Os 3 Sutras;os 3 Tantras Externos e os 3 Tantras Internos *** As Linhagens Nyingma: RING BRGYUD (Distante Extensiva);NYER BRGYUD (Próxima) e ZAB BRGYUD (Profunda) ou LINHAGEM DAS VISÕES PURAS *** Os Ensinamentos Paranormais e Sobrenaturais das DAG-SNANG ("Visões Puras") para o novo Ciclo de Aquarius *** A Tradição da DZOGCHEN ("Grande Perfeição")e suas práticas advaitas não-dualistas de Meditação *** A Busca da NGO-BO ("A Natureza de Buda Essencial e primordial")de todos os seres *** A RIG-PA ou CONSCI��NCIA LÚCIDA PURA ,natural e sem mente conceitual *** As técnicas Respiratórias para obter o Estado de OD-GSAL ("Luz desobstruída") *** A Energia da Kundalini e sua fusão com a GZHI RIG-PA ("Percepção Pristina Básica")do Corpo-mente biopsiquico *** As Práticas NONDRO de Ativação da RIG-PA *** As 7 Yôgas para o contato com o ADI-BUDDHA Primordial Teocósmico *** O Segredo Alquímico das 7 THIG-LE ("Gotas Bindus") e a Transmutação Bioquímica dos 4 Corpos KAYAS *** A Obtenção da FELICIDADE SUPREMA e a Auto-divinização Búddhica *** A Arte Sagrada do KALACHAKA e a formação dos novos ASHRAMS da Era de Aquarius no Ciclo 2016-2036. =================================================

Estamos montando Turmas online e Turmas presenciais (MANHÃ E TARDE) para um Seminário Extensivo de 2 meses e formação de um grupo fixo de Meditação Budista Tibetana ====================================================

CONTATOS : (51)99212-9003 *** 3242-1387 *** PORTO ALEGRE- BRAZIL

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- O MINISTRANTE: LEONARDO DE ALBUQUERQUE (Mestre Tantraraja Sanandar)é um Canalizador ,Clarividente e Professor de Meditação que traz novas abordagens e cosmovisões sobre o Autoconhecimento Humano,nas àreas da Ufologia,da BiopsicoEnergética e da Espiritualidade da Nova Era. A mais de 20 anos organiza Grupos de Meditação,centrados no DHARMA Budista,Tântrico,Vedantino e Sufista Oriental.

0 notes

Text

Universal Ground

Longchenpa on Universal Ground and Universal Ground Consciousness

The relationship of foundational consciousness and non-awareness is thus clear in these terms – non-awareness undergrids the very possibility of samsaric existence, and the foundational consciousness attempts to provide a model for how that basic lack of awareness can serve as a working basis for other emotions, cognitive acts, and personal continuity over many lifetimes. The other three dimensions of the universal ground are a natural extension offering details on how this unconscious substratum determines the health of one’s life world, shapes emotional and cognitive details across time, and constitutes one’s bodily struc- ture. It does this primarily through acting as a repository for the trace impressions of past and present activities and emotions, and then furthermore acting as the operational basis for those trace impressions to subsequently ripen into active proclivities influencing present and future cognition, emotion, and activity. Yet how do these fundamental layers of unconscious processes relate to other unconscious dimensions in human beings described as divine, yet in ordinary existence equally far removed from introspection, reflexive awareness, and deliberate intention?

In order to assess this question, we must examine the standard Great Perfection distinction between the terms “universal ground” (kun gzhi; alaya) and the “uni- versal ground consciousness” (kun gzhi’i rnam shes; alayavijñana), a distinction Longchenpa locates in Indian Yogacara literature. He cites a Bodhisattvabhumi passage which defines the “universal ground” as “non-conceptuality uninvolved with objects” and the “universal ground consciousness” as “non-conceptuality involved with objects” (Longchenpa 1973b, vol. 1, 85b.2). He also cites Sthiramati’s commentary to the Mahayana-sutralakkara, where he characterizes the “universal ground” as the overall basis for the accumulation of karma in the manner of their house, while the “universal ground consciousness” is that which “opens up the space...for the increase, amassing, decline, and so on of these karmic forces” (84.5). Longchenpa himself describes the universal ground consciousness as the “unceasing brightness and clarity” of the universal ground’s radiation, such that the former signifies how the latter diffuses outwards to oper- ate as the other seven aspects of typical consciousness-activity (Longchenpa 1971a, vol. 3, 120.1ff.). This subtle distinction, however, is of exceptional impor- tance when one considers its broader discursive context within the Seminal Heart’s central interest in cosmogony and divine creation stemming from pri- mordial cognition. The tradition posits an original, divine ground termed “the ground of all” (kun gyi gzhi ma), which in its contracted form leads us back to a “universal ground” (kun gzhi). This results in a fundamental ambiguity that extends throughout the system, namely whether “ground of all” with its cosmogonic primordiality signifies all of samsara and nirvaja, or simply all of samsara. Despite Longchenpa’s following the latter interpretative trajectory in The Treasury of Words and Meanings (Longchenpa 1983c), the term “primordial”(ye, ye don) typically signifies the transcendent dimension of a Buddha and nirvaja, whether referring to a Buddha’s knowledge as “primordial knowing” (ye shes) or describing the cosmogonic base as a “primordial ground” (ye gzhi). Indeed, Longchenpa’s own corpus elsewhere explicitly uses the term “universal ground” to signify the innately pure primordial ground of all reality (Longchenpa 1983d, 89.7).

This divine ground is explicitly identified as “a nucleus of enlightened movement” (de bzhin gshegs pa, S: tathagatagarbha) or Buddha-nature. While presented as a cosmogonic ground which ontologically precedes cyclic existence (saÅsara) and transcendence (nirvaja), it is also explicitly located within the human interior as an ongoing, deeply unconscious dimension. This dimension is engaged in a constant efflorescence that gives rise to both saÅsara and nirvaja, leading to the stock formulation of a single ontological ground leading to two paths, that is, interpretative trajectories resulting in a bifurcation of life-worlds. The ground itself is described as threefold – empty essence, radiant nature, and all-pervasive compassion – in a model explicitly based upon a Buddha’s three Bodies: the empty Reality Body (dharmakaya), the radiant Enjoyment Body (sambhogakaya), and the all-pervasive Emanational Body (nirmanakaya). The cosmogonic movement from the ground’s deep interiority and potential into man- ifestation is modeled after the description of the divine creation of pure lands, a process bound up with the emergence of Enjoyment Bodies and their majdalas out of the non-manifest matrix of the Reality Body. The completely interior and pure “ground” is described as undergoing a process of exteriorization and rupture resulting in this scenario, from which two paths (lam) extend: a path leading to enlightened transcendence (nirvaja) by means of the cognitive capacity recog- nizing the appearances as self, and a path leading to distorted cyclic existence (samsara) by means of a lack of such recognition. The former path is described as the mode of freedom (grol tshul) of the primordial Buddha All Good (kun tu bzang po, S: samantabhadra), while the latter path is described as the mode of deviation (‘khrul tshul) of sentient beings (sems can, S: sattva). Furthermore, the latter path is termed “non-awareness,” which is here identified as the “primordial universal ground,” that is, the basic unconscious matrix for animate life in samsara.

The inception of samsara and nirvaja is thus described as emerging in a bifurcated epistemological scenario in which an emergent cognitive capacity (shes pa, S: vijñana) develops out of a deeply unconscious state to newly encounter a lighting-up or appearances (snang ba). The bifurcation hinges on what is termed “recognition,” namely the reflexivity involved in this process of manifestation. In the case of transcendence, the interior and unconscious ground now infused with reflexive self-awareness becomes the Reality Body, the matrix of a divine creativity constituting the Buddha’s prolific forms and activity. In the case of deviation, the ground remains, albeit in a state of deep unconscious latency, while a derivative cognitive formation termed the “universal ground con- sciousness” becomes the operational matrix of a distorted and tainted creativity constituting a sentient being’s embodiment and activities. In other words, Buddha-nature is the cosmogonic ground, and the Reality Body is its transforma- tion with reflexive self-awareness, while the universal ground consciousness is a derivative unconscious matrix embedded within the even more deeply uncon- scious pure ground. In this manner, the relationship of the Buddha-nature/Reality Body and fundamental consciousness – wisdom and ignorance – is between two distinct unconscious domains in the body and mind that account for creation and agency beneath conscious reflection. The universal ground literally dissolves into the always already extant Buddha-nature, which then becomes an awakened Buddha. Thus foundational consciousness does not transform into a new type of unconscious process or cognitive constellation, but rather dissipates so that deeper movements can emerge into being, perception and emotions directly out- side of its meditating and distorting influences.

-From: A COMPARISON OF ALAYA-VIJÑANA IN YOGACARA AND DZOGCHEN

David F. Germano and William S. Waldron

8 notes

·

View notes