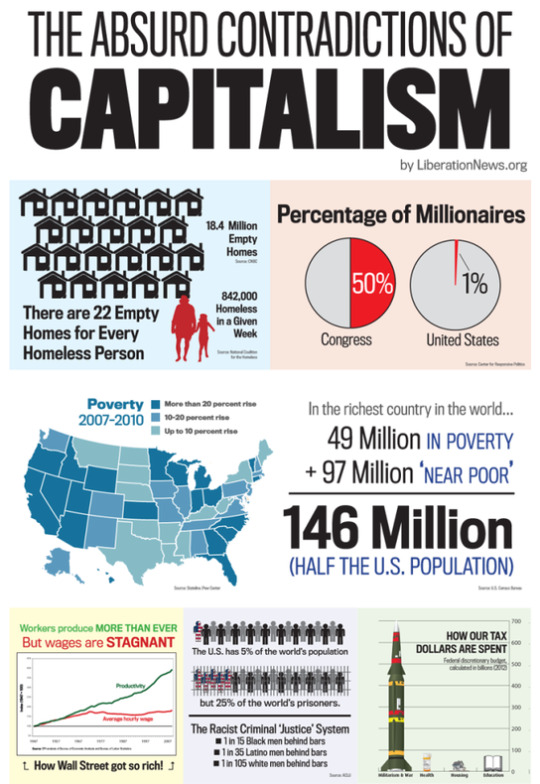

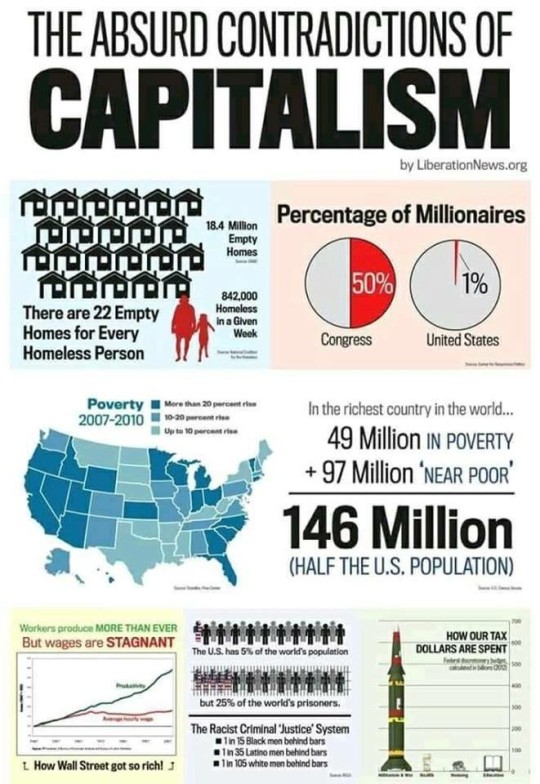

#contradictions of capitalism

Text

#contradictions of capitalism#socialist politics#marxism leninism#marxism#communism#socialism#communist#marxist leninist#socialist

381 notes

·

View notes

Text

#contradiction#republican hypocrisy#liberal hypocrisy#hypocrite#gop hypocrisy#hypocrites#funny memes#dank memes#best memes#relatable memes#memes#meme#dankest memes#dank humor#dank memage#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia#fuck neoliberals#neoliberal capitalism#anthony albanese#albanese government#usa news#usa#american indian#american#america

209 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter III. Economic Evolutions. — First Period. — The Division of Labor.

2. — Impotence of palliatives. — MM. Blanqui, Chevalier, Dunoyer, Rossi, and Passy.

All the remedies proposed for the fatal effects of parcellaire division may be reduced to two, which really are but one, the second being the inversion of the first: to raise the mental and moral condition of the workingman by increasing his comfort and dignity; or else, to prepare the way for his future emancipation and happiness by instruction.

We will examine successively these two systems, one of which is represented by M. Blanqui, the other by M. Chevalier.

M. Blanqui is a friend of association and progress, a writer of democratic tendencies, a professor who has a place in the hearts of the proletariat. In his opening discourse of the year 1845, M. Blanqui proclaimed, as a means of salvation, the association of labor and capital, the participation of the working man in the profits, — that is, a beginning of industrial solidarity. “Our century,” he exclaimed, “must witness the birth of the collective producer.” M. Blanqui forgets that the collective producer was born long since, as well as the collective consumer, and that the question is no longer a genetic, but a medical, one. Our task is to cause the blood proceeding from the collective digestion, instead of rushing wholly to the head, stomach, and lungs, to descend also into the legs and arms. Besides, I do not know what method M. Blanqui proposes to employ in order to realize his generous thought, — whether it be the establishment of national workshops, or the loaning of capital by the State, or the expropriation of the conductors of business enterprises and the substitution for them of industrial associations, or, finally, whether he will rest content with a recommendation of the savings bank to workingmen, in which case the participation would be put off till doomsday.

However this may be, M. Blanqui’s idea amounts simply to an increase of wages resulting from the copartnership, or at least from the interest in the business, which he confers upon the laborers. What, then, is the value to the laborer of a participation in the profits?

A mill with fifteen thousand spindles, employing three hundred hands, does not pay at present an annual dividend of twenty thousand francs. I am informed by a Mulhouse manufacturer that factory stocks in Alsace are generally below par and that this industry has already become a means of getting money by stock-jobbing instead of by labor. To SELL; to sell at the right time; to sell dear, — is the only object in view; to manufacture is only to prepare for a sale. When I assume, then, on an average, a profit of twenty thousand francs to a factory employing three hundred persons, my argument being general, I am twenty thousand francs out of the way. Nevertheless, we will admit the correctness of this amount. Dividing twenty thousand francs, the profit of the mill, by three hundred, the number of persons, and again by three hundred, the number of working days, I find an increase of pay for each person of twenty-two and one-fifth centimes, or for daily expenditure an addition of eighteen centimes, just a morsel of bread. Is it worth while, then, for this, to expropriate mill-owners and endanger the public welfare, by erecting establishments which must be insecure, since, property being divided into infinitely small shares, and being no longer supported by profit, business enterprises would lack ballast, and would be unable to weather commercial gales. And even if no expropriation was involved, what a poor prospect to offer the working class is an increase of eighteen centimes in return for centuries of economy; for no less time than this would be needed to accumulate the requisite capital, supposing that periodical suspensions of business did not periodically consume its savings!

The fact which I have just stated has been pointed out in several ways. M. Passy [13] himself took from the books of a mill in Normandy where the laborers were associated with the owner the wages of several families for a period of ten years, and he found that they averaged from twelve to fourteen hundred francs per year. He then compared the situation of mill-hands paid in proportion to the prices obtained by their employers with that of laborers who receive fixed wages, and found that the difference is almost imperceptible. This result might easily have been foreseen. Economic phenomena obey laws as abstract and immutable as those of numbers: it is only privilege, fraud, and absolutism which disturb the eternal harmony.

M. Blanqui, repentant, as it seems, at having taken this first step toward socialistic ideas, has made haste to retract his words. At the same meeting in which M. Passy demonstrated the inadequacy of cooperative association, he exclaimed: “Does it not seem that labor is a thing susceptible of organization, and that it is in the power of the State to regulate the happiness of humanity as it does the march of an army, and with an entirely mathematical precision? This is an evil tendency, a delusion which the Academy cannot oppose too strongly, because it is not only a chimera, but a dangerous sophism. Let us respect good and honest intentions; but let us not fear to say that to publish a book upon the organization of labor is to rewrite for the fiftieth time a treatise upon the quadrature of the circle or the philosopher’s stone.”

Then, carried away by his zeal, M. Blanqui finishes the destruction of his theory of cooperation, which M. Passy already had so rudely shaken, by the following example: “M. Dailly, one of the most enlightened of farmers, has drawn up an account for each piece of land and an account for each product; and he proves that within a period of thirty years the same man has never obtained equal crops from the same piece of land. The products have varied from twenty-six thousand francs to nine thousand or seven thousand francs, sometimes descending as low as three hundred francs. There are also certain products — potatoes, for instance — which fail one time in ten. How, then, with these variations and with revenues so uncertain, can we establish even distribution and uniform wages for laborers?....”

It might be answered that the variations in the product of each piece of land simply indicate that it is necessary to associate proprietors with each other after having associated laborers with proprietors, which would establish a more complete solidarity: but this would be a prejudgment on the very thing in question, which M. Blanqui definitively decides, after reflection, to be unattainable, — namely, the organization of labor. Besides, it is evident that solidarity would not add an obolus to the common wealth, and that, consequently, it does not even touch the problem of division.

In short, the profit so much envied, and often a very uncertain matter with employers, falls far short of the difference between actual wages and the wages desired; and M. Blanqui’s former plan, miserable in its results and disavowed by its author, would be a scourge to the manufacturing industry. Now, the division of labor being henceforth universally established, the argument is generalized, and leads us to the conclusion that misery is an effect of labor, as well as of idleness.

The answer to this is, and it is a favorite argument with the people: Increase the price of services; double and triple wages.

I confess that if such an increase was possible it would be a complete success, whatever M. Chevalier may have said, who needs to be slightly corrected on this point.

According to M. Chevalier, if the price of any kind of merchandise whatever is increased, other kinds will rise in a like proportion, and no one will benefit thereby.

This argument, which the economists have rehearsed for more than a century, is as false as it is old, and it belonged to M. Chevalier, as an engineer, to rectify the economic tradition. The salary of a head clerk being ten francs per day, and the wages of a workingman four, if the income of each is increased five francs, the ratio of their fortunes, which was formerly as one hundred to forty, will be thereafter as one hundred to sixty. The increase of wages, necessarily taking place by addition and not by proportion, would be, therefore, an excellent method of equalization; and the economists would deserve to have thrown back at them by the socialists the reproach of ignorance which they have bestowed upon them at random.

But I say that such an increase is impossible, and that the supposition is absurd: for, as M. Chevalier has shown very clearly elsewhere, the figure which indicates the price of the day’s labor is only an algebraic exponent without effect on the reality: and that which it is necessary first to endeavor to increase, while correcting the inequalities of distribution, is not the monetary expression, but the quantity of products. Till then every rise of wages can have no other effect than that produced by a rise of the price of wheat, wine, meat, sugar, soap, coal, etc., — that is, the effect of a scarcity. For what is wages?

It is the cost price of wheat, wine, meat, coal; it is the integrant price of all things. Let us go farther yet: wages is the proportionality of the elements which compose wealth, and which are consumed every day reproductively by the mass of laborers. Now, to double wages, in the sense in which the people understand the words, is to give to each producer a share greater than his product, which is contradictory: and if the rise pertains only to a few industries, a general disturbance in exchange ensues, — that is, a scarcity. God save me from predictions! but, in spite of my desire for the amelioration of the lot of the working class, I declare that it is impossible for strikes followed by an increase of wages to end otherwise than in a general rise in prices: that is as certain as that two and two make four. It is not by such methods that the workingmen will attain to wealth and — what is a thousand times more precious than wealth — liberty. The workingmen, supported by the favor of an indiscreet press, in demanding an increase of wages, have served monopoly much better than their own real interests: may they recognize, when their situation shall become more painful, the bitter fruit of their inexperience!

Convinced of the uselessness, or rather, of the fatal effects, of an increase of wages, and seeing clearly that the question is wholly organic and not at all commercial, M. Chevalier attacks the problem at the other end. He asks for the working class, first of all, instruction, and proposes extensive reforms in this direction.

Instruction! this is also M. Arago’s word to the workingmen; it is the principle of all progress. Instruction!.... It should be known once for all what may be expected from it in the solution of the problem before us; it should be known, I say, not whether it is desirable that all should receive it, — this no one doubts, — but whether it is possible.

To clearly comprehend the complete significance of M. Chevalier’s views, a knowledge of his methods is indispensable.

M. Chevalier, long accustomed to discipline, first by his polytechnic studies, then by his St. Simonian connections, and finally by his position in the University, does not seem to admit that a pupil can have any other inclination than to obey the regulations, a sectarian any other thought than that of his chief, a public functionary any other opinion than that of the government. This may be a conception of order as respectable as any other, and I hear upon this subject no expressions of approval or censure. Has M. Chevalier an idea to offer peculiar to himself? On the principle that all that is not forbidden by law is allowed, he hastens to the front to deliver his opinion, and then abandons it to give his adhesion, if there is occasion, to the opinion of authority. It was thus that M. Chevalier, before settling down in the bosom of the Constitution, joined M. Enfantin: it was thus that he gave his views upon canals, railroads, finance, property, long before the administration had adopted any system in relation to the construction of railways, the changing of the rate of interest on bonds, patents, literary property, etc.

M. Chevalier, then, is not a blind admirer of the University system of instruction, — far from it; and until the appearance of the new order of things, he does not hesitate to say what he thinks. His opinions are of the most radical.

M. Villemain had said in his report: “The object of the higher education is to prepare in advance a choice of men to occupy and serve in all the positions of the administration, the magistracy, the bar and the various liberal professions, including the higher ranks and learned specialties of the army and navy.”

“The higher education,” thereupon observes M. Chevalier, [14] “is designed also to prepare men some of whom shall be farmers, others manufacturers, these merchants, and those private engineers. Now, in the official programme, all these classes are forgotten. The omission is of considerable importance; for, indeed, industry in its various forms, agriculture, commerce, are neither accessories nor accidents in a State: they are its chief dependence.... If the University desires to justify its name, it must provide a course in these things; else an industrial university will be established in opposition to it.... We shall have altar against altar, etc....”

And as it is characteristic of a luminous idea to throw light on all questions connected with it, professional instruction furnishes M. Chevalier with a very expeditious method of deciding, incidentally, the quarrel between the clergy and the University on liberty of education.

“It must be admitted that a very great concession is made to the clergy in allowing Latin to serve as the basis of education. The clergy know Latin as well as the University; it is their own tongue. Their tuition, moreover, is cheaper; hence they must inevitably draw a large portion of our youth into their small seminaries and their schools of a higher grade....”

The conclusion of course follows: change the course of study, and you decatholicize the realm; and as the clergy know only Latin and the Bible, when they have among them neither masters of art, nor farmers, nor accountants; when, of their forty thousand priests, there are not twenty, perhaps, with the ability to make a plan or forge a nail, — we soon shall see which the fathers of families will choose, industry or the breviary, and whether they do not regard labor as the most beautiful language in which to pray to God.

Thus would end this ridiculous opposition between religious education and profane science, between the spiritual and the temporal, between reason and faith, between altar and throne, old rubrics henceforth meaningless, but with which they still impose upon the good nature of the public, until it takes offence.

M. Chevalier does not insist, however, on this solution: he knows that religion and monarchy are two powers which, though continually quarrelling, cannot exist without each other; and that he may not awaken suspicion, he launches out into another revolutionary idea, — equality.

“France is in a position to furnish the polytechnic school with twenty times as many scholars as enter at present (the average being one hundred and seventy-six, this would amount to three thousand five hundred and twenty). The University has but to say the word.... If my opinion was of any weight, I should maintain that mathematical capacity is much less special than is commonly supposed. I remember the success with which children, taken at random, so to speak, from the pavements of Paris, follow the teaching of La Martiniere by the method of Captain Tabareau.”

If the higher education, reconstructed according to the views of M. Chevalier, was sought after by all young French men instead of by only ninety thousand as commonly, there would be no exaggeration in raising the estimate of the number of minds mathematically inclined from three thousand five hundred and twenty to ten thousand; but, by the same argument, we should have ten thousand artists, philologists, and philosophers; ten thousand doctors, physicians, chemists, and naturalists; ten thousand economists, legists, and administrators; twenty thousand manufacturers, foremen, merchants, and accountants; forty thousand farmers, wine-growers, miners, etc., — in all, one hundred thousand specialists a year, or about one-third of our youth. The rest, having, instead of special adaptations, only mingled adaptations, would be distributed indifferently elsewhere.

It is certain that so powerful an impetus given to intelligence would quicken the progress of equality, and I do not doubt that such is the secret desire of M. Chevalier. But that is precisely what troubles me: capacity is never wanting, any more than population, and the problem is to find employment for the one and bread for the other. In vain does M. Chevalier tell us: “The higher education would give less ground for the complaint that it throws into society crowds of ambitious persons without any means of satisfying their desires, and interested in the overthrow of the State; people without employment and unable to get any, good for nothing and believing themselves fit for anything, especially for the direction of public affairs. Scientific studies do not so inflate the mind. They enlighten and regulate it at once; they fit men for practical life....” Such language, I reply, is good to use with patriarchs: a professor of political economy should have more respect for his position and his audience. The government has only one hundred and twenty offices annually at its disposal for one hundred and seventy-six students admitted to the polytechnic school: what, then, would be its embarrassment if the number of admissions was ten thousand, or even, taking M. Chevalier’s figures, three thousand five hundred? And, to generalize, the whole number of civil positions is sixty thousand, or three thousand vacancies annually; what dismay would the government be thrown into if, suddenly adopting the reformatory ideas of M. Chevalier, it should find itself besieged by fifty thousand office-seekers! The following objection has often been made to republicans without eliciting a reply: When everybody shall have the electoral privilege, will the deputies do any better, and will the proletariat be further advanced? I ask the same question of M. Chevalier: When each academic year shall bring you one hundred thousand fitted men, what will you do with them?

To provide for these interesting young people, you will go down to the lowest round of the ladder. You will oblige the young man, after fifteen years of lofty study, to begin, no longer as now with the offices of aspirant engineer, sub-lieutenant of artillery, second lieutenant, deputy, comptroller, general guardian, etc., but with the ignoble positions of pioneer, train-soldier, dredger, cabin-boy, fagot-maker, and exciseman. There he will wait, until death, thinning the ranks, enables him to advance a step. Under such circumstances a man, a graduate of the polytechnic school and capable of becoming a Vauban, may die a laborer on a second class road, or a corporal in a regiment

Oh! how much more prudent Catholicism has shown itself, and how far it has surpassed you all, St. Simonians, republicans, university men, economists, in the knowledge of man and society! The priest knows that our life is but a voyage, and that our perfection cannot be realized here below; and he contents himself with outlining on earth an education which must be completed in heaven. The man whom religion has moulded, content to know, do, and obtain what suffices for his earthly destiny, never can become a source of embarrassment to the government: rather would he be a martyr. O beloved religion! is it necessary that a bourgeoisie which stands in such need of you should disown you?...

Into what terrible struggles of pride and misery does this mania for universal instruction plunge us! Of what use is professional education, of what good are agricultural and commercial schools, if your students have neither employment nor capital? And what need to cram one’s self till the age of twenty with all sorts of knowledge, then to fasten the threads of a mule-jenny or pick coal at the bottom of a pit? What! you have by your own confession only three thousand positions annually to bestow upon fifty thousand possible capacities, and yet you talk of establishing schools! Cling rather to your system of exclusion and privilege, a system as old as the world, the support of dynasties and patriciates, a veritable machine for gelding men in order to secure the pleasures of a caste of Sultans. Set a high price upon your teaching, multiply obstacles, drive away, by lengthy tests, the son of the proletaire whom hunger does not permit to wait, and protect with all your power the ecclesiastical schools, where the students are taught to labor for the other life, to cultivate resignation, to fast, to respect those in high places, to love the king, and to pray to God. For every useless study sooner or later becomes an abandoned study: knowledge is poison to slaves.

Surely M. Chevalier has too much sagacity not to have seen the consequences of his idea. But he has spoken from the bottom of his heart, and we can only applaud his good intentions: men must first be men; after that, he may live who can.

Thus we advance at random, guided by Providence, who never warns us except with a blow: this is the beginning and end of political economy.

Contrary to M. Chevalier, professor of political economy at the College of France, M. Dunoyer, an economist of the Institute, does not wish instruction to be organized. The organization of instruction is a species of organization of labor; therefore, no organization. Instruction, observes M. Dunoyer, is a profession, not a function of the State; like all professions, it ought to be and remain free. It is communism, it is socialism, it is the revolutionary tendency, whose principal agents have been Robespierre, Napoleon, Louis XVIII, and M. Guizot, which have thrown into our midst these fatal ideas of the centralization and absorption of all activity in the State. The press is very free, and the pen of the journalist is an object of merchandise; religion, too, is very free, and every wearer of a gown, be it short or long, who knows how to excite public curiosity, can draw an audience about him. M. Lacordaire has his devotees, M. Leroux his apostles, M. Buchez his convent. Why, then, should not instruction also be free? If the right of the instructed, like that of the buyer, is unquestionable, and that of the instructor, who is only a variety of the seller, is its correlative, it is impossible to infringe upon the liberty of instruction without doing violence to the most precious of liberties, that of the conscience. And then, adds M. Dunoyer, if the State owes instruction to everybody, it will soon be maintained that it owes labor; then lodging; then shelter.... Where does that lead to?

The argument of M. Dunoyer is irrefutable: to organize instruction is to give to every citizen a pledge of liberal employment and comfortable wages; the two are as intimately connected as the circulation of the arteries and the veins. But M. Dunoyer’s theory implies also that progress belongs only to a certain select portion of humanity, and that barbarism is the eternal lot of nine-tenths of the human race. It is this which constitutes, according to M. Dunoyer, the very essence of society, which manifests itself in three stages, religion, hierarchy, and beggary. So that in this system, which is that of Destutt de Tracy, Montesquieu, and Plato, the antinomy of division, like that of value, is without solution.

It is a source of inexpressible pleasure to me, I confess, to see M. Chevalier, a defender of the centralization of instruction, opposed by M. Dunoyer, a defender of liberty; M. Dunoyer in his turn antagonized by M. Guizot; M. Guizot, the representative of the centralizers, contradicting the Charter, which posits liberty as a principle; the Charter trampled under foot by the University men, who lay sole claim to the privilege of teaching, regardless of the express command of the Gospel to the priests: Go and teach. And above all this tumult of economists, legislators, ministers, academicians, professors, and priests, economic Providence giving the lie to the Gospel, and shouting: Pedagogues! what use am I to make of your instruction?

Who will relieve us of this anxiety? M. Rossi leans toward eclecticism: Too little divided, he says, labor remains unproductive; too much divided, it degrades man. Wisdom lies between these extremes; in medio virtus. Unfortunately this intermediate wisdom is only a small amount of poverty joined with a small amount of wealth, so that the condition is not modified in the least. The proportion of good and evil, instead of being as one hundred to one hundred, becomes as fifty to fifty: in this we may take, once for all, the measure of eclecticism. For the rest, M. Rossi’s juste-milieu is in direct opposition to the great economic law: To produce with the least possible expense the greatest possible quantity of values.... Now, how can labor fulfil its destiny without an extreme division? Let us look farther, if you please.

“All economic systems and hypotheses,” says M. Rossi, “belong to the economist, but the intelligent, free, responsible man is under the control of the moral law... Political economy is only a science which examines the relations of things, and draws conclusions therefrom. It examines the effects of labor; in the application of labor, you should consider the importance of the object in view. When the application of labor is unfavorable to an object higher than the production of wealth, it should not be applied... Suppose that it would increase the national wealth to compel children to labor fifteen hours a day: morality would say that that is not allowable. Does that prove that political economy is false? No; that proves that you confound things which should be kept separate.”

If M. Rossi had a little more of that Gallic simplicity so difficult for foreigners to acquire, he would very summarily have thrown his tongue to the dogs, as Madame de Sevigne said. But a professor must talk, talk, talk, not for the sake of saying anything, but in order to avoid silence. M. Rossi takes three turns around the question, then lies down: that is enough to make certain people believe that he has answered it.

It is surely a sad symptom for a science when, in developing itself according to its own principles, it reaches its object just in time to be contradicted by another; as, for example, when the postulates of political economy are found to be opposed to those of morality, for I suppose that morality is a science as well as political economy. What, then, is human knowledge, if all its affirmations destroy each other, and on what shall we rely? Divided labor is a slave’s occupation, but it alone is really productive; undivided labor belongs to the free man, but it does not pay its expenses. On the one hand, political economy tells us to be rich; on the other, morality tells us to be free; and M. Rossi, speaking in the name of both, warns us at the same time that we can be neither free nor rich, for to be but half of either is to be neither. M. Rossi’s doctrine, then, far from satisfying this double desire of humanity, is open to the objection that, to avoid exclusiveness, it strips us of everything: it is, under another form, the history of the representative system.

But the antagonism is even more profound than M. Rossi has supposed. For since, according to universal experience (on this point in harmony with theory), wages decrease in proportion to the division of labor, it is clear that, in submitting ourselves to parcellaire slavery, we thereby shall not obtain wealth; we shall only change men into machines: witness the laboring population of the two worlds. And since, on the other hand, without the division of labor, society falls back into barbarism, it is evident also that, by sacrificing wealth, we shall not obtain liberty: witness all the wandering tribes of Asia and Africa. Therefore it is necessary — economic science and morality absolutely command it — for us to solve the problem of division: now, where are the economists? More than thirty years ago, Lemontey, developing a remark of Smith, exposed the demoralizing and homicidal influence of the division of labor. What has been the reply; what investigations have been made; what remedies proposed; has the question even been understood?

Every year the economists report, with an exactness which I would commend more highly if I did not see that it is always fruitless, the commercial condition of the States of Europe. They know how many yards of cloth, pieces of silk, pounds of iron, have been manufactured; what has been the consumption per head of wheat, wine, sugar, meat: it might be said that to them the ultimate of science is to publish inventories, and the object of their labor is to become general comptrollers of nations. Never did such a mass of material offer so fine a field for investigation. What has been found; what new principle has sprung from this mass; what solution of the many problems of long standing has been reached; what new direction have studies taken?

One question, among others, seems to have been prepared for a final judgment, — pauperism. Pauperism, of all the phenomena of the civilized world, is today the best known: we know pretty nearly whence it comes, when and how it arrives, and what it costs; its proportion at various stages of civilization has been calculated, and we have convinced ourselves that all the specifics with which it hitherto has been fought have been impotent. Pauperism has been divided into genera, species, and varieties: it is a complete natural history, one of the most important branches of anthropology. Well I the unquestionable result of all the facts collected, unseen, shunned, covered by the economists with their silence, is that pauperism is constitutional and chronic in society as long as the antagonism between labor and capital continues, and that this antagonism can end only by the absolute negation of political economy. What issue from this labyrinth have the economists discovered?

This last point deserves a moment’s attention.

In primitive communism misery, as I have observed in a preceding paragraph, is the universal condition.

Labor is war declared upon this misery.

Labor organizes itself, first by division, next by machinery, then by competition, etc.

Now, the question is whether it is not in the essence of this organization, as given us by political economy, at the same time that it puts an end to the misery of some, to aggravate that of others in a fatal and unavoidable manner. These are the terms in which the question of pauperism must be stated, and for this reason we have undertaken to solve it.

What means, then, this eternal babble of the economists about the improvidence of laborers, their idleness, their want of dignity, their ignorance, their debauchery, their early marriages, etc.? All these vices and excesses are only the cloak of pauperism; but the cause, the original cause which inexorably holds four-fifths of the human race in disgrace, — what is it? Did not Nature make all men equally gross, averse to labor, wanton, and wild? Did not patrician and proletaire spring from the same clay? Then how happens it that, after so many centuries, and in spite of so many miracles of industry, science, and art, comfort and culture have not become the inheritance of all? How happens it that in Paris and London, centres of social wealth, poverty is as hideous as in the days of Caesar and Agricola? Why, by the side of this refined aristocracy, has the mass remained so uncultivated? It is laid to the vices of the people: but the vices of the upper class appear to be no less; perhaps they are even greater. The original stain affected all alike: how happens it, once more, that the baptism of civilization has not been equally efficacious for all? Does this not show that progress itself is a privilege, and that the man who has neither wagon nor horse is forced to flounder about for ever in the mud? What do I say? The totally destitute man has no desire to improve: he has fallen so low that ambition even is extinguished in his heart.

“Of all the private virtues,” observes M. Dunoyer with infinite reason, “the most necessary, that which gives us all the others in succession, is the passion for well-being, is the violent desire to extricate one’s self from misery and abjection, is that spirit of emulation and dignity which does not permit men to rest content with an inferior situation.... But this sentiment, which seems so natural, is unfortunately much less common than is thought. There are few reproaches which the generality of men deserve less than that which ascetic moralists bring against them of being too fond of their comforts: the opposite reproach might be brought against them with infinitely more justice.... There is even in the nature of men this very remarkable feature, that the less their knowledge and resources, the less desire they have of acquiring these. The most miserable savages and the least enlightened of men are precisely those in whom it is most difficult to arouse wants, those in whom it is hardest to inspire the desire to rise out of their condition; so that man must already have gained a certain degree of comfort by his labor, before he can feel with any keenness that need of improving his condition, of perfecting his existence, which I call the love of well-being.” [15]

Thus the misery of the laboring classes arises in general from their lack of heart and mind, or, as M. Passy has said somewhere, from the weakness, the inertia of their moral and intellectual faculties. This inertia is due to the fact that the said laboring classes, still half savage, do not have a sufficiently ardent desire to ameliorate their condition: this M. Dunoyer shows. But as this absence of desire is itself the effect of misery, it follows that misery and apathy are each other’s effect and cause, and that the proletariat turns in a circle.

To rise out of this abyss there must be either well-being, — that is, a gradual increase of wages, — or intelligence and courage, — that is, a gradual development of faculties: two things diametrically opposed to the degradation of soul and body which is the natural effect of the division of labor. The misfortune of the proletariat, then, is wholly providential, and to undertake to extinguish it in the present state of political economy would be to produce a revolutionary whirlwind.

For it is not without a profound reason, rooted in the loftiest considerations of morality, that the universal conscience, expressing itself by turns through the selfishness of the rich and the apathy of the proletariat, denies a reward to the man whose whole function is that of a lever and spring. If, by some impossibility, material well-being could fall to the lot of the parcellaire laborer, we should see something monstrous happen: the laborers employed at disagreeable tasks would become like those Romans, gorged with the wealth of the world, whose brutalized minds became incapable of devising new pleasures. Well-being without education stupefies people and makes them insolent: this was noticed in the most ancient times. Incrassatus est, et recalcitravit, says

Deuteronomy. For the rest, the parcellaire laborer has judged himself: he is content, provided he has bread, a pallet to sleep on, and plenty of liquor on Sunday. Any other condition would be prejudicial to him, and would endanger public order.

At Lyons there is a class of men who, under cover of the monopoly given them by the city government, receive higher pay than college professors or the head-clerks of the government ministers: I mean the porters. The price of loading and unloading at certain wharves in Lyons, according to the schedule of the Rigues or porters’ associations, is thirty centimes per hundred kilogrammes. At this rate, it is not seldom that a man earns twelve, fifteen, and even twenty francs a day: he only has to carry forty or fifty sacks from a vessel to a warehouse. It is but a few hours’ work. What a favorable condition this would be for the development of intelligence, as well for children as for parents, if, of itself and the leisure which it brings, wealth was a moralizing principle! But this is not the case: the porters of Lyons are today what they always have been, drunken, dissolute, brutal, insolent, selfish, and base. It is a painful thing to say, but I look upon the following declaration as a duty, because it is the truth: one of the first reforms to be effected among the laboring classes will be the reduction of the wages of some at the same time that we raise those of others. Monopoly does not gain in respectability by belonging to the lowest classes of people, especially when it serves to maintain only the grossest individualism. The revolt of the silk-workers met with no sympathy, but rather hostility, from the porters and the river population generally. Nothing that happens off the wharves has any power to move them. Beasts of burden fashioned in advance for despotism, they will not mingle with politics as long as their privilege is maintained. Nevertheless, I ought to say in their defence that, some time ago, the necessities of competition having brought their prices down, more social sentiments began to awaken in these gross natures: a few more reductions seasoned with a little poverty, and the Rigues of Lyons will be chosen as the storming-party when the time comes for assaulting the bastilles.

In short, it is impossible, contradictory, in the present system of society, for the proletariat to secure well-being through education or education through well-being. For, without considering the fact that the proletaire, a human machine, is as unfit for comfort as for education, it is demonstrated, on the one hand, that his wages continually tend to go down rather than up, and, on the other, that the cultivation of his mind, if it were possible, would be useless to him; so that he always inclines towards barbarism and misery. Everything that has been attempted of late years in France and England with a view to the amelioration of the condition of the poor in the matters of the labor of women and children and of primary instruction, unless it was the fruit of some hidden thought of radicalism, has been done contrary to economic ideas and to the prejudice of the established order. Progress, to the mass of laborers, is always the book sealed with the seven seals; and it is not by legislative misconstructions that the relentless enigma will be solved.

For the rest, if the economists, by exclusive attention to their old routine, have finally lost all knowledge of the present state of things, it cannot be said that the socialists have better solved the antinomy which division of labor raised. Quite the contrary, they have stopped with negation; for is it not perpetual negation to oppose, for instance, the uniformity of parcellaire labor with a so-called variety in which each one can change his occupation ten, fifteen, twenty times a day at will?

As if to change ten, fifteen, twenty times a day from one kind of divided labor to another was to make labor synthetic; as if, consequently, twenty fractions of the day’s work of a manual laborer could be equal to the day’s work of an artist! Even if such industrial vaulting was practicable, — and it may be asserted in advance that it would disappear in the presence of the necessity of making laborers responsible and therefore functions personal, — it would not change at all the physical, moral, and intellectual condition of the laborer; the dissipation would only be a surer guarantee of his incapacity and, consequently, his dependence. This is admitted, moreover, by the organizers, communists, and others. So far are they from pretending to solve the antinomy of division that all of them admit, as an essential condition of organization, the hierarchy of labor, — that is, the classification of laborers into parcellaires and generalizers or organizers, — and in all utopias the distinction of capacities, the basis or everlasting excuse for inequality of goods, is admitted as a pivot. Those reformers whose schemes have nothing to recommend them but logic, and who, after having complained of the simplism, monotony, uniformity, and extreme division of labor, then propose a plurality as a SYNTHESIS, — such inventors, I say, are judged already, and ought to be sent back to school.

But you, critic, the reader undoubtedly will ask, what is your solution? Show us this synthesis which, retaining the responsibility, the personality, in short, the specialty of the laborer, will unite extreme division and the greatest variety in one complex and harmonious whole.

My reply is ready: Interrogate facts, consult humanity: we can choose no better guide. After the oscillations of value, division of labor is the economic fact which influences most perceptibly profits and wages. It is the first stake driven by Providence into the soil of industry, the starting-point of the immense triangulation which finally must determine the right and duty of each and all. Let us, then, follow our guides, without which we can only wander and lose ourselves.

Tu longe seggere, et vestigia semper adora.

#organization#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#the system of economic contradictions#the philosophy of poverty#volume i#pierre-joseph proudhon#pierre joseph proudhon

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

so I remember the outage at Kate in this update the first time around. she's a nurse and should know better than to tell John what Dean said, especially when Dean is stuck in this very isolated place with him. and that's all true, she should know

but we don't know how exactly the conversation started. there's just one clue for us: Dean's been working in the barn for some time before he decides to pick up the phone and call Cas. he hasn't heard the phone ring, or he might wonder about the line being in use

this tells us that John called Kate, not the other way around

the rest below a cut because it's what I think, but it's not in the text for a few reasons, and as is my calling, it just makes things complicated with no black or white resolution

John called Kate. not because he knows anything has gone on, just to have a chat. his kid just stormed out and it's time to work on his other family, where he can start fresh. (Sam called it in his last scene. he's astute that way.) but this means Kate's plan to take some time and think about everything she just learned goes out the window. not ready to talk to John, she probably tried to get off the line, but he needled. picked up there was something off and tried to ask if there was some issue between them (with Sam walking out, a statement of failure on John's part, he's not gonna play the loser twice in a row)

not wanting to draw attention to the fact that there IS an issue, maybe she thought she could be clever. confirm the truth of the surprising things Dean told her. maybe she started by asking about Sam, thinking she'll catch John in a lie. and oh, Sam, he's gone back to school, yeah, they start early there. has John said how proud he is of that kid, how he could get into any college in the world from here? and Adam will be a smart one like Sam, no doubt about it, and go to a smartypants school too, or whatever school Kate wants him in. it's hard when the kids are far from home but at least Dean's stayed close by and John's always got him for the farm, he's invaluable for that

and this is. not what she expected. during her visit, they seemed like such a put-together household, which is what John is reflecting now. which is not what Dean said over the phone. and I think she's still cautious, but now she's confused, and she tries asking another canny question but she slips up. it wouldn't take much to trigger John's suspicion, and he has one goal, which is: don't lose Kate

and he says he can tell something's the matter and she tries to say there isn't and that's when we get into the kind of back and forth where John is playing to his strength. hell, he'd even offer to hang up and give her some time, but in a way that now she's the one apologizing (just like Dean apologizes in another scene, when he isn't the one who should be saying sorry). and when he asks what's changed she admits she had a strange call from Dean and she doesn't know what to make of it. she still doesn't intend to say anything about the content of that call, but John knows enough. he knows what to ask, what to plant, what to make her question Dean's motives until she is revealing more and he's twisting up her doubts and reflecting them back and insisting Dean's story doesn't add up, which, maybe it doesn't? and this is confusing, upsetting, she doesn't know which way is up, and John is just so certain. has an explanation for everything

by the time the call is ending she's just agreeing with everything John's saying because he's shot down every single other point so efficiently that it seems there's no purpose in searching for exhausting counterarguments with him. and she's confused and defeated. and once she hangs up, she knows less than when she started. she doesn't know if the sick feeling in her stomach is worry that Dean was telling the truth and she's just betrayed him or if it's the distaste of Adam having a half-brother, one he's met and adores, who's a sociopath that would make up anything to keep her away. she's stuck between two realities because she knows someone is lying to her very well but can't tell which one

she doesn't speak to John again, letting his calls go to voicemail. if she thinks about making a tip, she doesn't know who it will help or hurt. a week after this, she gets a call from Dean at a different number. she is partly relieved to hear his voice because she's been concerned she got it all wrong, but also unsure at the start of whether she'll be hearing another fabulation to keep her away

Dean's not looking for sympathy or an apology or any of that. he's not calling to accuse her or even tell her directly of her role in that final fight. he just says that he wanted her to know he's pressing charges with the police, here's the case number and this is Jody's extension, and that if Kate and Adam would like to set up no-contact orders it wouldn't be a bad idea and they could piggy-back off Dean's case. he's applying to be Sam's legal guardian, and he doesn't have a fixed place to stay yet but here's where to write or call. that if it's alright with Kate, he'd like to stay in touch with Adam, even if what they share is a rotten dad

she knows, then. she puts the pieces together and I think that guilt plagues her. she apologizes, desperately apologizes and tries to explain, and Dean goes quiet. then says he knows what his dad is like. he always believed John too. it's not an "I forgive you" but it's a sense of commiseration. he wouldn't wish John on anybody, and everything that happened was done by John, not her

#spirit of the west daily#this is a story and not a case study on helping abuse victims#people don't do the right thing in every moment#and anyone who is in John's range is going to be lied to and deliberately deceived#to Kate��� John is the father of her kid who's been reconnecting with her and hinting at marriage#Dean contradicted the version of reality John presented her for months and now John is reaffirming it and he's the one she thinks she knows#and she thought she had a read on Dean from her brief visit and she thought she had a read on John#but she's wrong about one of them and her judgement is shot and John would capitalize on that#the relationship between Dean and Kate would likely be rather cool after this#but I see him staying connected with Adam and having him out for visits in later years

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi comrades, itʼs been a minute. Sorry for being inactive on here over the past months, but I thought I would share something here that I wrote two years ago on this day.

🔹🔹🔹🔹🔹🔹🔹🔹🔹🔹🔹🔹🔹🔹🔹🔹

The ever so misanthropic and cynical arrogance of the petty-bourgeoisie is a universal class trait spun from the intensified monopolizing tendency of capitalism.

*Why did not the lousy serf chose to become a noble? The sub-human deserves no dignity nor affection in their own miserableness. It is not I who have made it the way society functions; it is their own faults for not being capable to determine her own desire.*

... Such is the rotten and mischievous mindset of the dissonantly deflecting oppressor, who steadily is on the hunt to advance in itʼs own economic, and thus hierarchical societal ranks of sorts.

Fear and trickery is constantly used as inducement by the oppressing part (again)st the oppressed part.

Capitalism is, by no (but also every) means, different than feudalism in this regard. It is only the material circumstances and structures that has developed, mainly due to the variousness of technological advancements throughout, and mainly so in the imperialist cores by the extraction and transfer of resources and labour power, which produces both value and, moreover; abundance and scarcity.

As Karl Marx described it when he so eloquently detailed the result of the increased antagonism between two conflicted, yet inbound, poles:

“Accumulation of wealth at one pole is, therefore, at the same time accumulation of misery, agony of toil slavery, ignorance, brutality, mental degradation, at the opposite pole, i.e., on the side of the class that produces its own product in the form of capital.”

Let me be perfectly clear to you who may read this: the ongoing treats and attacks against the proletariat across the bourgeois states by the capitalist class – behaviorally and rhetorically as individuals, or from the state power itself, whether it comes to austerity-packed reforms or state police and military brutality and repression — is ONLY going to intensify (grow worse and, with that, more obvious) unless the working class study to become class-conscious (awareness means vigilance) of the systematic dependency and thereafter organize, and fight back to put an end to the perpetual spiral of exploitation that is both in- and out of control.

The ruling class perpetualizes the status quo, and they hold on to it by every and any tool possible; from mass media to manufacturing consent through education and various of everyday material and holding of means of communications to productions, to mass-surveillance, to commercially glamorous nothingness, to parlamentarism to manufacturing and determining monetary value and societal laws, norms and abnorms, thus what “is” and what feels right and “is” and what feels wrong, passionate passivity, social alienation, division, wars, meaningless conflicts, better versus worse, competitions, appropriations, corruption, controlled linguistics, receptions, meaning... our very existences.

#marxism leninism#thoughts#philosophy#marxism#cultural hegemony#text post#psychological#decadence#societal abnormality#capitalism#imperialism#reflections#contradictions

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

ive spent the last 24 hours in a haze of reading momfluenced and scrolling through the instagrams of all the momfluencers the book mentions and ohhhh my god I have to delete instagram and fling my phone in the river when I’m a parent. you know how being a communist with a weird gender lets you see through the matrix of social constructs sometimes? these ladies are patching the matrix back up with cute gingham as fast as I can tear it down

#does that make sense. like. the thing I’ve found most personally clarifying about leftism is the ability to hear someone tell you#‘life is hard’ or about the contradictions of capitalism and realize it doesn have to be this way#but momfluencers are so squarely of this moment in capitalism and in misogyny and at the same time what they’re selling can be attractive#you know.#my posts#reading tag#and unfortunately I do like the momfluencer aesthetic. not the minimalism but I like linen and chunky pottery and sage green and wood. u kno

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

can this person come over so i can dig my nails into their skin instead of my own

#og#this is acutally so dumb racism is not just mere hatred it is a class/caste system unto itself#the white workers dont just hate on the black workers they actively want the black workers to work for them#you cant divorce race from capitalism like that ohhhh i hate this brand of marxist#the purpose of racial caste is to create a permanent underclass of workers. slaves. yea? its not secondary to capitalism it IS capitalism#op was responding to 'why is class the primary contradiction and not antiblackness'#now i dont rly believe in primary contradictions at all. but. this is rly bad

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Andrew is always contradicting himself. Like he goes on and on about capitalism and how it's oppressive and blah blah, but then turns around and dates a fraud witch who charges thousands of dollars to sell portions and spells. Someone please knock some sense into that boy before she makes him husband number 5.

Living sometimes makes the human being fall into contradictions. Capitalism is oppressive and shit for most working people within this system. But he and the luxury witch no longer live the routine of salaried workers. They have the comfort that money gives at hand. So it’s very easy to forget how this system fucks the lives of the majority for the benefit of a quantitative minority.

And no, I don’t think he’s going to become her fifth husband.

(warning you here, I don’t know, I might bite my tongue in the future)

#ask box#ask anon#my thoughts#capitalism sucks#andrew garfield#kate tomas#luxury witch#contradictions#ask response

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

You know, if chuck made like thousands of worlds with different versions of Sam and Dean that he gave up on when he got bored, who's to say that Steve and Robin aren't an early draft of them 🤷

#stranger things#steve harrington#robin buckley#platonic stobin#platonic with a capital p#supernatural#once again spreading my Steve and Robin are Sam and Dean coded agenda#They'd be the best hunters ever actually#stranger things au#fic ideas#I don't care if this makes no sense with Supernatural's canon I'm pretty sure Supernatural canon contradicts itself all the time

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

She wants more and less at the same time.

She lives a life of contradictions and she’s caught between her own contradictory desires. She wants more and less at the same time, just as I do. “What I really want, really really want, is to work less,” she writes. But she also wants an antique rug. She loves a particular rug owned by her godparents, who cared for her when her mother couldn’t. When she visits her godparents and sees the rug, she can’t think about anything else. She wants them to offer the rug to her, but they don’t. They have already given her a rug. She wants this rug so badly that she feels “ripped off.” It’s as if her godparents have stolen something from her by having a rug that she wants. Her desire has made it hers, and her desire has imbued it with the livingness she’s losing as she begins to hate her godparents for having the rug. She feels disgusted with herself. But still, she wants the rug. “One of the main things Marx noticed about capitalism,” she writes, “is that it really encourages people to have relationships with things instead of with other people.”

— Eula Biss, Having and Being Had (Riverhead Books, September 1, 2020)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think. we would all benefit from a real and genuine grown up level history lesson on the matryoshka of colonialism and empire in the americas. and i think we should stop meming the oppression of the irish because it is encouraging ahistorical backlash.

#it is hard to hold the many contradictions#you see the scottish were oppressed in many ways but also big time oppressors#as were the irish#the seven ‘civilized’ tribes participated in the slave trade and some deny freedman tribal membership today#black americans exploited and colonized liberia and are being encouraged to do the same in ghana (albeit in a very 21st century way)#(i should say african americans)#and it goes on like this in many directions because that is the matrix capitalism and colonialism creates. on purpose and by design#but all of these things are very complicated beyond even the way i have described them here#we turn history into very easy historical narratives but history is not that neat#and it’s not even past

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

[i'm tired of waiting for the world to be beautiful]

2022-02-24 14:47

let's talk about the loving eyes of an old dog staring down a shotgun barrel,

the death of this author, and other things common in my workplace.

what greater harm than supplication?

the third drop of water falling on your forehead,

not yet a sledgehammer, more an irritant.

you are feeling excessively baptized.

so tired of rivers and heads on platters

you mistook the stryx for the lethe and,

in an ageless hunger for absolution,

walked into the water until your head went under

—you can live with that?

—yes, but you will never stop wanting what you can't have

the person with arrogance to think i could survive this unchanged died

and they left me behind, an unlucky echo-child born of productivity.

the other shining me: backfacing angel of history

cast a hurricane: all hungry mouth and mass homelessness

so that's what they made me and that's what i am.

—i thought it would be different this time

—why?

—i thought you would be different

—(pained laughter)

the deathly afraid butterfly cannot crawl back into the cocoon

not even if it prefers familiarity to growth, suffers from vertigo,

and would rather be loved than be free.

#this one's about capitalism#and how you think you can get a job and stay how you are which is a radical queer contradiction#you think you can work and not be consumed you think you can avoid becoming a part of the machine that wounds and kills people like you#but you can't and it makes you someone else and you can't go back because it is giving you this illusion of safety you now need to survive#the society that wounded you is profiting off the psychological dysfunction (fawn response) its cruelty gave you#and the version of you that thought it could do that watches in horror as you simper at the feet of the people who would see you dead#clavain writes#poetry#poets on tumblr#walter benjamin's text on the angel of history (paul klee) is underpinning this piece

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#contradiction#contradictory#capitalism#fascism#jerktrillionaires#jerkbillionaires#jerkmillionaires#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia#fuck neoliberals#neoliberal capitalism#anthony albanese#albanese government#anti capitalist#capitalist hell#venture capital#washington capitals#capitalist dystopia#capitalist bullshit#class war#eat the rich#eat the fucking rich#anti religion#antinazi#anti capitalism#antiauthoritarian

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter IV. Second Period. — Machinery.

2. — Machinery’s contradiction. — Origin of capital and wages.

From the very fact that machinery diminishes the workman’s toil, it abridges and diminishes labor, the supply of which thus grows greater from day to day and the demand less. Little by little, it is true, the reduction in prices causing an increase in consumption, the proportion is restored and the laborer set at work again: but as industrial improvements steadily succeed each other and continually tend to substitute mechanical operations for the labor of man, it follows that there is a constant tendency to cut off a portion of the service and consequently to eliminate laborers from production. Now, it is with the economic order as with the spiritual order: outside of the church there is no salvation; outside of labor there is no subsistence. Society and nature, equally pitiless, are in accord in the execution of this new decree.

“When a new machine, or, in general, any process whatever that expedites matters,” says J. B. Say, “replaces any human labor already employed, some of the industrious arms, whose services are usefully supplanted, are left without work. A new machine, therefore, replaces the labor of a portion of the laborers, but does not diminish the amount of production, for, if it did, it would not be adopted; it displaces revenue. But the ultimate advantage is wholly on the side of machinery, for, if abundance of product and lessening of cost lower the venal value, the consumer — that is, everybody — will benefit thereby.”

Say’s optimism is infidelity to logic and to facts. The question here is not simply one of a small number of accidents which have happened during thirty centuries through the introduction of one, two, or three machines; it is a question of a regular, constant, and general phenomenon. After revenue has been displaced as Say says, by one machine, it is then displaced by another, and again by another, and always by another, as long as any labor remains to be done and any exchanges remain to be effected. That is the light in which the phenomenon must be presented and considered: but thus, it must be admitted, its aspect changes singularly. The displacement of revenue, the suppression of labor and wages, is a chronic, permanent, indelible plague, a sort of cholera which now appears wearing the features of Gutenberg, now assumes those of Arkwright; here is called Jacquard, there James Watt or Marquis de Jouffroy. After carrying on its ravages for a longer or shorter time under one form, the monster takes another, and the economists, who think that he has gone, cry out: “It was nothing!” Tranquil and satisfied, provided they insist with all the weight of their dialectics on the positive side of the question, they close their eyes to its subversive side, notwithstanding which, when they are spoken to of poverty, they again begin their sermons upon the improvidence and drunkenness of laborers.

In 1750, — M. Dunoyer makes the observation, and it may serve as a measure of all lucubrations of the same sort, — “in 1750 the population of the duchy of Lancaster was 300,000 souls. In 1801, thanks to the development of spinning machines, this population was 672,000 souls. In 1831 it was 1,336,000 souls. Instead of the 40,000 workmen whom the cotton industry formerly employed, it now employs, since the invention of machinery, 1,500,000.”

M. Dunoyer adds that at the time when the number of workmen employed in this industry increased in so remarkable a manner, the price of labor rose one hundred and fifty per cent. Population, then, having simply followed industrial progress, its increase has been a normal and irreproachable fact, — what do I say? — a happy fact, since it is cited to the honor and glory of the development of machinery. But suddenly M. Dunoyer executes an about-face: this multitude of spinning-machines soon being out of work, wages necessarily declined; the population which the machines had called forth found itself abandoned by the machines, at which M. Dunoyer declares: Abuse of marriage is the cause of poverty.

English commerce, in obedience to the demand of the immense body of its patrons, summons workmen from all directions, and encourages marriage; as long as labor is abundant, marriage is an excellent thing, the effects of which they are fond of quoting in the interest of machinery; but, the patronage fluctuating, as soon as work and wages are not to be had, they denounce the abuse of marriage, and accuse laborers of improvidence. Political economy — that is, proprietary despotism — can never be in the wrong: it must be the proletariat.

The example of printing has been cited many a time, always to sustain the optimistic view. The number of persons supported today by the manufacture of books is perhaps a thousand times larger than was that of the copyists and illuminators prior to Gutenberg’s time; therefore, they conclude with a satisfied air, printing has injured nobody. An infinite number of similar facts might be cited, all of them indisputable, but not one of which would advance the question a step. Once more, no one denies that machines have contributed to the general welfare; but I affirm, in regard to this incontestable fact, that the economists fall short of the truth when they advance the absolute statement that the simplification of processes has nowhere resulted in a diminution of the number of hands employed in any industry whatever. What the economists ought to say is that machinery, like the division of labor, in the present system of social economy is at once a source of wealth and a permanent and fatal cause of misery.

In 1836, in a Manchester mill, nine frames, each having three hundred and twenty-four spindles, were tended by four spinners. Afterwards the mules were doubled in length, which gave each of the nine six hundred and eighty spindles and enabled two men to tend them.

There we have the naked fact of the elimination of the workman by the machine. By a simple device three workmen out of four are evicted; what matters it that fifty years later, the population of the globe having doubled and the trade of England having quadrupled, new machines will be constructed and the English manufacturers will reemploy their workmen? Do the economists mean to point to the increase of population as one of the benefits of machinery? Let them renounce, then, the theory of Malthus, and stop declaiming against the excessive fecundity of marriage.

They did not stop there: soon a new mechanical improvement enabled a single worker to do the work that formerly occupied four.

A new three-fourths reduction of manual work: in all, a reduction of human labor by fifteen-sixteenths.

A Bolton manufacturer writes: “The elongation of the mules of our frames permits us to employ but twenty-six spinners where we employed thirty-five in 1837.”

Another decimation of laborers: one out of four is a victim.

These facts are taken from the “Revue Economique” of 1842; and there is nobody who cannot point to similar ones. I have witnessed the introduction of printing machines, and I can say that I have seen with my own eyes the evil which printers have suffered thereby. During the fifteen or twenty years that the machines have been in use a portion of the workmen have gone back to composition, others have abandoned their trade, and some have died of misery: thus laborers are continually crowded back in consequence of industrial innovations. Twenty years ago eighty canal-boats furnished the navigation service between Beaucaire and Lyons; a score of steam-packets has displaced them all. Certainly commerce is the gainer; but what has become of the boating-population? Has it been transferred from the boats to the packets? No: it has gone where all superseded industries go, — it has vanished.

For the rest, the following documents, which I take from the same source, will give a more positive idea of the influence of industrial improvements upon the condition of the workers.

The average weekly wages, at Manchester, is ten shillings. Out of four hundred and fifty workers there are not forty who earn twenty shillings.

The author of the article is careful to remark that an Englishman consumes five times as much as a Frenchman; this, then, is as if a French workingman had to live on two francs and a half a week.

“Edinburgh Review,” 1835: “To a combination of workmen (who did not want to see their wages reduced) we owe the mule of Sharpe and Roberts of Manchester; and this invention has severely punished the imprudent unionists.”

Punished should merit punishment. The invention of Sharpe and Roberts of Manchester was bound to result from the situation; the refusal of the workmen to submit to the reduction asked of them was only its determining occasion. Might not one infer, from the air of vengeance affected by the “Edinburgh Review,” that machines have a retroactive effect?

An English manufacturer: “The insubordination of our workmen has given us the idea of dispensing with them. We have made and stimulated every imaginable effort of the mind to replace the service of men by tools more docile, and we have achieved our object. Machinery has delivered capital from the oppression of labor. Wherever we still employ a man, we do so only temporarily, pending the invention for us of some means of accomplishing his work without him.”

What a system is that which leads a business man to think with delight that society will soon be able to dispense with men! Machinery has delivered capital from the oppression of labor! That is exactly as if the cabinet should undertake to deliver the treasury from the oppression of the taxpayers. Fool! though the workmen cost you something, they are your customers: what will you do with your products, when, driven away by you, they shall consume them no longer? Thus machinery, after crushing the workmen, is not slow in dealing employers a counter-blow; for, if production excludes consumption, it is soon obliged to stop itself.

During the fourth quarter of 1841 four great failures, happening in an English manufacturing city, threw seventeen hundred and twenty people on the street.

These failures were caused by over-production, — that is, by an inadequate market, or the distress of the people. What a pity that machinery cannot also deliver capital from the oppression of consumers! What a misfortune that machines do not buy the fabrics which they weave! The ideal society will be reached when commerce, agriculture, and manufactures can proceed without a man upon earth!

In a Yorkshire parish for nine months the operatives have been working but two days a week.

Machines!

At Geston two factories valued at sixty thousand pounds sterling have been sold for twenty-six thousand. They produced more than they could sell.

Machines!

In 1841 the number of children under thirteen years of age engaged in manufactures diminishes, because children over thirteen take their place.

Machines! The adult workman becomes an apprentice, a child, again: this result was foreseen from the phase of the division of labor, during which we saw the quality of the workman degenerate in the ratio in which industry was perfected.

In his conclusion the journalist makes this reflection: “Since 1836 there has been a retrograde movement in the cotton industry”; — that is, it no longer keeps up its relation with other industries: another result foreseen from the theory of the proportionality of values.

Today workmen’s coalitions and strikes seem to have stopped throughout England, and the economists rightly rejoice over this return to order, — let us say even to common sense. But because laborers henceforth — at least I cherish the hope — will not add the misery of their voluntary periods of idleness to the misery which machines force upon them, does it follow that the situation is changed? And if there is no change in the situation, will not the future always be a deplorable copy of the past?

The economists love to rest their minds on pictures of public felicity: it is by this sign principally that they are to be recognized, and that they estimate each other. Nevertheless there are not lacking among them, on the other hand, moody and sickly imaginations, ever ready to offset accounts of growing prosperity with proofs of persistent poverty.

M. Theodore Fix thus summed up the general situation in December, 1844:

The food supply of nations is no longer exposed to those terrible disturbances caused by scarcities and famines, so frequent up to the beginning of the nineteenth century. The variety of agricultural growths and improvements has abolished this double scourge almost absolutely. The total wheat crop in France in 1791 was estimated at about 133,000,000 bushels, which gave, after deducting seed, 2.855 bushels to each inhabitant. In 1840 the same crop was estimated at 198,590,000 bushels, or 2.860 bushels to each individual, the area of cultivated surface being almost the same as before the Revolution.... The rate of increase of manufactured goods has been at least as high as that of food products; and we are justified in saying that the mass of textile fabrics has more than doubled and perhaps tripled within fifty years. The perfecting of technical processes has led to this result....

Since the beginning of the century the average duration of life has increased by two or three years, — an undeniable sign of greater comfort, or, if you will, a diminution of poverty.

Within twenty years the amount of indirect revenue, without any burdensome change in legislation, has risen from $40,000,000 francs to 720,000,000, — a symptom of economic, much more than of fiscal, progress.

On January 1, 1844, the deposit and consignment office owed the savings banks 351,500,000 francs, and Paris figured in this sum for 105,000,000. Nevertheless the development of the institution has taken place almost wholly within twelve years, and it should be noticed that the 351,500,000 francs now due to the savings banks do not constitute the entire mass of economies effected, since at a given time the capital accumulated is disposed of otherwise.... In 1843, out of 320,000 workmen and 80,000 house-servants living in the capital, 90,000 workmen have deposited in the savings banks 2,547,000 francs, and 34,000 house-servants 1,268,000 francs.

All these facts are entirely true, and the inference to be drawn from them in favor of machines is of the exactest, — namely, that they have indeed given a powerful impetus to the general welfare. But the facts with which we shall supplement them are no less authentic, and the inference to be drawn from these against machines will be no less accurate, — to wit, that they are a continual cause of pauperism. I appeal to the figures of M. Fix himself.

Out of 320,000 workmen and 80,000 house-servants residing in Paris, there are 230,000 of the former and 46,000 of the latter — a total of 276,000 — who do not deposit in the savings banks. No one would dare pretend that these are 276,000 spendthrifts and ne’er-do-weels who expose themselves to misery voluntarily. Now, as among the very ones who make the savings there are to be found poor and inferior persons for whom the savings bank is but a respite from debauchery and misery, we may conclude that, out of all the individuals living by their labor, nearly three-fourths either are imprudent, lazy, and depraved, since they do not deposit in the savings banks, or are too poor to lay up anything. There is no other alternative. But common sense, to say nothing of charity, permits no wholesale accusation of the laboring class: it is necessary, therefore, to throw the blame back upon our economic system. How is it that M. Fix did not see that his figures accused themselves?

They hope that, in time, all, or almost all, laborers will deposit in the savings banks. Without awaiting the testimony of the future, we may test the foundations of this hope immediately.

According to the testimony of M. Vee, mayor of the fifth arrondissement of Paris, “the number of needy families inscribed upon the registers of the charity bureaus is 30,000, — which is equivalent to 65,000 individuals.” The census taken at the beginning of 1846 gave 88,474. And poor families not inscribed, — how many are there of those? As many. Say, then, 180,000 people whose poverty is not doubtful, although not official. And all those who live in straitened circumstances, though keeping up the appearance of comfort, — how many are there of those? Twice as many, — a total of 360,000 persons, in Paris, who are somewhat embarrassed for means.

“They talk of wheat,” cries another economist, M. Louis Leclerc, “but are there not immense populations which go without bread? Without leaving our own country, are there not populations which live exclusively on maize, buckwheat, chestnuts?”

M. Leclerc denounces the fact: let us interpret it. If, as there is no doubt, the increase of population is felt principally in the large cities, — that is, at those points where the most wheat is consumed, — it is clear that the average per head may have increased without any improvement in the general condition. There is no such liar as an average.