#chinese empress

Text

Battle of the Barbies! Round 7: Historical (Sub Round 4)

This is round 7 (sub round 4) of the bracket. All other polls in can be found here.

#Battle of the barbies#barbie#barbies#barbie doll#barbie dolls#barbie collectibles#barbie collector#barbie core#doll#dolls#dollcore#doll collector#doll collection#doll community#my post#non disney#polls#historical dolls#historical barbies#chinese empress#empress#30s

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wu Zetian

Wu Zetian, the first and only female ruler of Imperial China, lived a life marked by ambition as well as controversy. Born into a wealthy family in 624 CE, Wu was encouraged by her father to pursue education, an uncommon privilege for girls in ancient China. Selected as a concubine for Emperor Taizong at age 14, Wu's intellect and charm quickly captured the emperor's attention, leading to her elevation to the position of secretary.

Her rise to power was gradual yet strategic. Despite being sent to a convent after Taizong's death, Wu's affair with Taizong's son, Gaozong, secured her return to court as his empress consort. With Gaozong's declining health, Wu's influence grew, and she effectively ruled as the power behind the throne, manoeuvring court politics to eliminate rivals and solidify her position.

Wu's reign was marked by significant reforms and achievements. She restructured the government, reduced bureaucracy, and implemented policies to improve agriculture, education, and military efficiency. However, her later years saw a decline in her hold on power, characterised by paranoia, scandalous affairs with young lovers, and purges within her administration.

In 704 CE, Wu was forced to abdicate in favour of her son Zhongzong due to mounting discontent among court officials. After her death in 705 CE, real power shifted to Empress Wei, who played a role in influencing Zhongzong and the court.

Despite controversy surrounding her reign, Wu's legacy endures. Modern historians acknowledge her as a visionary leader whose reforms laid the groundwork for China's prosperity under Emperor Xuanzong. While remembered for her supposed crimes, including the rumoured murder of her daughter, Wu's impact on Chinese history remains profound, inspiring continued fascination and debate about her rule and legacy. She ruled during the Tang Dynasty and establishing her own Zhou Dynasty, leaving an indelible mark on the history of China.

I also highly suggest watching the series on YouTube by Extra History

youtube

this is the link for part 1 ^

#wu zetian#chinese empress#chinese history#tang dynasty#zhou dynasty#imperial china#empress#women in history#women throughout history#Youtube

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Noooooooooooo, Pixabay allow AI Images like this one! AI creeps everywhere. From writing stories, to art, to music, to... writing email for you? WHY, WHY, WHY!?!

I know Tiktok allow AI stuffs too. Who next???

#ai art#anti ai#fuck ai art#fuck ai#chinese woman#china#empress#chinese empress#illustration#pixabay#ai generated#ai image#ai artwork#ai girl#ai is theft#ai is not art#ai issues

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Chinese royalty Barbies 🖤

She is the Chinese Empress from the Great Eras collection, rebodied onto a Model Muse body.

And Princess of China from the Dolls of the World Princess collection.

#thegreymoon's dolls#barbie#chinese empress#great eras#princess of china#dolls of the world#the princess collection

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Western Han (202 BC – 9 AD) Traditional Clothing Hanfu Photoshoot

“这个位子 我有何坐不得?”

“我欲问鼎天下,试问谁与争锋”

"Why can't I sit in this seat?"

"I want to conquer the world, who can compete with me?"

【About The First Empress of the Han Dynasty Empress Lü:Lǚ zhì(吕雉)】

Lü Zhi (241–18 August 180 BC), courtesy name E'xu (娥姁) and commonly known as Empress Lü (traditional Chinese: 呂后; simplified Chinese: 吕后; pinyin: Lǚ Hòu) and formally Empress Gao of Han (漢高后; 汉高后; Hàn Gāo Hòu), was the empress consort of Gaozu, the founding emperor of the Han dynasty. They had two known children, Liu Ying (later Emperor Hui of Han) and Princess Yuan of Lu. Lü was the first woman to assume the title Empress of China and paramount power. After Gaozu's death, she was honoured as empress dowager and regent during the short reigns of Emperor Hui and his successors Emperor Qianshao of Han and Liu Hong (Emperor Houshao).

She played a role in the rise and foundation of her husband, Emperor Gaozu, and his dynasty, and in some of the laws and customs laid down by him. Empress Lü, even in the absence of her husband from the capital, killed two prominent generals who played an important role in Gaozu's rise to power, namely Han Xin and Peng Yue, as a lesson for the aristocracy and other generals. In June 195 BC, with the death of Gaozu, Empress Lü became, as the widow of the late emperor and mother of the new emperor, Empress Dowager (皇太后, Huángtàihòu), and assumed a leadership role in her son's administration. Less than a year after Emperor Hui's accession to the throne, in 194 BC, Lü had one of the late Emperor Gaozu's consorts whom she deeply hated, Concubine Qi, put to death in a cruel manner. She also had Concubine Qi's son Liu Ruyi poisoned to death. Emperor Hui was shocked by his mother's cruelty and fell sick for a year, and thereafter no longer became involved in state affairs, and gave more power to his mother. As a result, Empress dowager Lü held the court, listened to the government, spoke on behalf of the emperor, and did everything (臨朝聽政制, "linchao ting zhengzhi"). With the untimely death of her 22-year-old son, Emperor Hui, Empress dowager Lü subsequently proclaimed his two young sons emperor (known historically as Emperor Qianshao and Emperor Houshao respectively). She gained more power than ever before, and these two young emperors had no legitimacy as emperors in history; the history of this 8-year period is considered and recognized as the reign of Empress Dowager Lü. She dominated the political scene for 15 years until her death in August 180 BC, and is often depicted as the first woman to have ruled China. While four women are noted as having been politically active before her—Fu Hao, Yi Jiang, Lady Nanzi, and Queen Dowager Xuan—Lü was the perhaps first woman to have ruled over united China.

Lü Zhi was born in Shanfu County (單父; present-day Shan County, Shandong) during the late Qin Dynasty. Her courtesy name was Exu (Chinese: 娥姁; pinyin: Éxǔ). To flee from enemies, her father Lü Wen (呂文) brought their family to Pei County, settled there, and became a close friend of the county magistrate. Many influential men in town came to visit Lü Wen. Xiao He, then an assistant of the magistrate, was in charge of the seating arrangement and collection of gifts from guests at a banquet in Lü Wen's house, and he announced, "Those who do not offer more than 1,000 coins in gifts shall be seated outside the hall." Liu Bang (later Emperor Gaozu of Han), then a minor patrol officer (亭長), went there bringing a single cent and said, "I offer 10,000 coins." Lü Wen saw Liu Bang and was so impressed with him on first sight, that he immediately stood up and welcomed Liu into the hall to sit beside him. Xiao He told Lü Wen that Liu Bang was not serious, but Liu ignored him and chatted with Lü. Lü Wen said, "I used to predict fortunes for many people but I've never seen someone so exceptional like you before." Lü Wen then offered his daughter Lü Zhi's hand in marriage to Liu Bang and they were wed. Lü Zhi bore Liu Bang a daughter (later Princess Yuan of Lu) and a son, Liu Ying (later Emperor Hui of Han).

Liu Bang later participated in the rebellion against the Qin Dynasty under the insurgent Chu kingdom, nominally-ruled by King Huai II. Lü Zhi and her two children remained with her father and family for most of the time during this period.

Even after Emperor Gaozu (Liu Bang)'s victory over Xiang Yu, there were still unstable areas in the empire, requiring the new government to launch military campaigns to pacify these regions thereafter. Gaozu placed Empress Lü Zhi and the crown prince Liu Ying (Lü Zhi's son) in charge of the capital Chang'an and making key decisions in court, assisted by the chancellor Xiao He and other ministers. During this time, Lü Zhi proved herself to be a competent administrator in domestic affairs, and she quickly established strong working relationships with many of Gaozu's officials, who admired her for her capability and feared her for her ruthlessness. After the war ended and Emperor Gaozu returned, she remained in power and she was always influential in many of the country's affairs.

In his late years, Emperor Gaozu started favouring one of his younger consorts, Concubine Qi(戚夫人), who bore him a son, Liu Ruyi, who was instated as Prince of Zhao in 198 BC, displacing Lü Zhi's son-in-law Zhang Ao (Princess Yuan of Lu's husband). Gaozu had the intention of replacing Liu Ying with Liu Ruyi as crown prince, reasoning that the former was too "soft-hearted and weak" and that the latter resembled him more. Since Lü Zhi had strong rapport with many ministers, they generally opposed Gaozu's decision but the emperor seemed bent on deposing Liu Ying. Lü Zhi became worried and she approached Zhang Liang for help, and the latter analysed that Gaozu was changing the succession on grounds of favouritism. Zhang Liang invited the "Four Whiteheads of Mount Shang", a group of four reclusive wise men, to persuade Gaozu to change his decision. The four men promised to assist Liu Ying in future if he became emperor, and Gaozu was pleased to see that Liu Ying had their support. Gaozu told Concubine Qi, "I wanted to replace (the crown prince). Now I see that he has the support of those four men; he is fully fledged and difficult to unseat. Empress Lü is really in charge!" This marked the end of the dispute over the succession and affirmed Liu Ying's role as crown prince.

In June 195 BC, Emperor Gaozu died and was succeeded by Liu Ying, who became historically known as Emperor Hui of Han. Lü Zhi was honoured by Emperor Hui as empress dowager. She exerted more influence during the reign of her son than she had when she was empress, and she became the powerful and effective lead figure in his administration.

Lü Zhi did not harm most of Gaozu's other consorts and treated them according to the rules and customs of the imperial family. For example, consorts who bore male children that were instated as princes were granted the title of "Princess Dowager" (王太妃) in their respective sons' principalities. One exception was Concubine Qi, whom Lü Zhi greatly resented because of the dispute over the succession between Liu Ruyi (Qi's son) and Liu Ying. Liu Ruyi, the Prince of Zhao, was away in his principality, so Lü Zhi targeted Concubine Qi. She had Qi stripped of her position, treated like a convict (head shaved, in stocks, dressed in prison garb), and forced to do hard labour in the form of milling rice.

Roles in the deaths of Concubine Qi and Liu Ruyi

Lü Zhi then summoned Liu Ruyi, who was around the age of 12 then, to Chang'an, intending to kill him together with his mother. However Zhou Chang (周昌), the chancellor in Liu Ruyi's principality, whom Lü Zhi respected because of his stern opposition to Emperor Gaozu's proposal to make Liu Ruyi crown prince, temporarily protected Liu Ruyi from harm by responding to Lü Zhi's order that, "The Prince of Zhao is ill and unfit for travelling over long distances." Lü Zhi then ordered Zhou Chang to come to the capital, had him detained, and then summoned Liu Ruyi again. Emperor Hui tried to save Liu Ruyi by intercepting his half-brother before the latter entered Chang'an, and kept Liu Ruyi by his side most of the time. Lü Zhi refrained from carrying out her plans for several months because she feared that she might harm Emperor Hui as well.

One morning in the winter of 195-194 BC, Emperor Hui went for a hunting trip and did not bring Liu Ruyi with him because the latter refused to get out of bed. Lü Zhi's chance arrived, so she sent an assassin to force poisoned wine down Liu Ruyi's throat. The young prince was dead by the time Emperor Hui returned. Lü Zhi then had Concubine Qi killed in an inhumane manner: she had Qi's limbs chopped off, eyes gouged out, ears sliced off, nose sliced off, tongue cut out, forced her to drink a potion that made her mute, and had her thrown into a latrine. She called Qi a "human swine" (人彘). Several days later, Emperor Hui was taken to view the "human swine" and was shocked to learn that it was Concubine Qi. He cried loudly and became ill for a long time. He requested to see his mother and said, "This is something done not by a human. As the empress dowager's son, I'll never be able to rule the empire" From then on, Emperor Hui indulged himself in carnal pleasures and ignored state affairs, leaving all of them to his mother, and this caused power to fall completely into her hands.

When Lu first came to the court, she planned to establish the Lu family members as "kings (nobles)". This was not only to commemorate her deceased relatives, but also to strengthen her power in the court. However, Wang Ling, the prime minister at the time, immediately pointed out that the great ancestor Liu Bang(Husband of Lu, founding emperor of Han Dynasty)once killed the white horse and agreed that "if someone who are not Liu family be come the king, the whole world should attack them." Therefore, the move of establishing a foreign surname as the king violated the ancestral system established by Liu Bang and was really inappropriate.

Faced with the obstruction of Wang Ling, Empress Lu responded by deposing him and insisting on honoring her deceased father and two brothers as King Lu Xuan, King Wu Wu, and King Zhao Zhao. After setting this precedent, Lu was out of control. She not only named her three nephews Lu Tai, Lu Chan, and Lu Lu as King Lu, King Liang, and King Zhao respectively, but also named her grandnephew Lu Tong. He was the King of Yan, and his grandson Zhang Yan was granted the title of King of Lu.

In addition, there are also quite a few people with the surname Lu who have been granted the title of marquis. As a result, it can be said that many princes surnamed Lu appeared in the court in the blink of an eye. They controlled the government and became the cornerstone and support for Empress Lu to control the right to speak in the court.

Empress Lu's life was emblematic of the intricate power dynamics of the Han Dynasty in ancient China. Born into a modest family, Lu rose to prominence through her marriage to Emperor Gaozu. Her astute political acumen and strategic alliances allowed her to wield significant influence behind the throne. As the mother of several emperors, she orchestrated their ascensions and manipulated court politics to consolidate power for her family. However, her ruthless pursuit of control and elimination of rivals earned her both admirers and enemies. In the end, her ambitions led to her downfall, as her unchecked power and manipulation of succession angered the nobility.As a result, after her death, the Lu family was retaliated and killed by the nobles and courtiers who supported the Han Dynasty, and the family was almost exterminated.Empress Lu's life illustrates the delicate balance of power, ambition, and intrigue in ancient Chinese imperial courts.

Literati in every dynasty in China often likened women who attempted to participate in government affairs and influence national policies to Empress Lü, saying they were vicious. One of them was Wu Zetian, the first official female emperor of China. However, compared with Empress Lü, Wu Zetian was more talented. Unlike Empress Lü, who was simply vicious, she ignored the system and stability of the empire and put personal and family interests first.

________________

📸Photo & Model :@金角大魔王i

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/1763668330/NFVOXthxX

________________

#chinese hanfu#Western Han (202 BC – 9 AD)#hanfu#Empress Lü#Lǚ zhì(吕雉)#china history#chinese history#hanfu accessories#hanfu_challenge#chinese traditional clothing#china#chinese#woman in history#漢服#汉服#中華風#金角大魔王i#historical fashion

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women in History Month (insp) | Week 1: Leading Women

#historyedit#perioddramaedit#women in history#women in history month challenge#lady of birka#marie madeleine d'aiguillon#empress gongsheng#elizaveta petrovna#jayadevi#zenobia of palmyra#margrete of denmark#viking age#scandinavian history#french history#cambodian history#song dynasty#chinese history#russian empire#3rd century#7th century#8th century#10th century#14th century#15th century#16th century#17th century#18th century#my edits#mine

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women warriors in Chinese history - Part 1

“In the nomadic tribes of the foreign princesses from the Steppes northwest to the northeast of the Chinese borders, women habitually rode horses and were frequently also skilled militarily. They had to be able to survive on their own and defend themselves when their men left camp to herd animals for months on end. Thus, unsurprisingly, many daughters of nomadic and semi-nomadic tribal chiefs were also capable fighters. Madam Pan 潘夫人 of “barbarian origins” during the Wei dynasty, the semi-barbarian Princess Pingyang 平陽公主 who helped establish the Tang dynasty, and the “barbarian queen,” Empress Dowager Xiao, are historical examples of this category of female generals.

While the barbarians to the north were known as fan 番, those belonging to peripheral areas from the southwest to the southeast were known as man 蠻. Like the nomadic princesses, these women of non-Chinese or Chinese ethnic minority groups did not bind their feet and could thus become formidable opponents. Indeed, the female battle units within the Taiping 太平 rebel forces that actually entered combat – rather than merely providing labour as most of the female units did –were reportedly made up in the main of women from the Miao 苗 tribes, aside from the Hakka (Kejia 客家) women of Guangxi.

Female bandit leaders or daughters and sisters of bandit leaders who occupied mountains or established strongholds in marginal lands are almost indistinguishable from the man barbarian princesses of tribal chieftains in novels and shadow plays. Such barbarian women generals and female bandit leaders were rarely privileged enough to be recorded by the historians. The three found most frequently, Madam Xi 洗夫人 (502– 557), Madam Washi 瓦氏夫人 (1498–1557),95 and Madam Xu 許夫人 (1271–1368), were all pro-Chinese. While the first two cooperated with the Chinese government, the third joined Chinese forces against the Mongols. A certain Zhejie 折節 or Shejie 蛇節, a female leader of the Miao tribe, also led a rebellion against Mongol troupes, but she eventually surrendered to them and was subsequently executed.

Real enemies of the Chinese empire, such as the Trv’vy sisters of Vietnam, are hardly ever mentioned by the Chinese, even though they are first recorded in the Han dynastic history. Even under such circumstances, of the women commanders in Chinese history studied by Xiaolin Li, a hefty per cent were from “minor nationalities.”

Female rebel leaders and women warriors in rebel forces tended to rise from peasantry and marginal groups such as families of itinerant performers, robbers, boatmen, and hunters. Many of them are beautiful and charismatic. Most of the rebel groups were basically bandits (known as haohan 好漢, “bravos” euphemistically) – how else could they have survived without a continuous source of income? Many of the bandit groups, like the sworn brothers of the Water Margin, lived in mountains and marshlands, awaiting a chance to start or join in an uprising with the hope of gaining power and legitimacy through either pardon (when they posed too great a threat to the state) or founding a new dynasty. Many had sisters, wives, or daughters who were also capable of leading armies.”

Chinese shadow theatre: history, popular religion, and women warriors, Fan Pen Li Chen

#history#women in history#warrior women#women's history#historyblr#warriors#quotes#women warriors#china#chinese history#asian history#Princess Pingyang#empress dowager chengtian#lady washi#taiping rebellion#trung sisters

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

🔥👑 Fearsome empress 👑🔥

180 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Legend of Zhen Huan :: Zhen Huan’s red jifu

#legend of zhen huan#cdrama#perioddramaedit#cdramanet#cdramaedit#cdramagifs#gzh#empresses in the palace#qing dynasty#甄嬛传#sun li#孙俪#betty sun#wardrobe#zhcostumes#gifshistorical#costumesource#asiandramanet#perioddramasource#onlyperioddramas#chinese drama

71 notes

·

View notes

Note

empress is so spoiled (as she should be) compared to the reader in other AUs 😭😭

Well, the Empress is royalty, she is used to being ridiculously spoiled 😅

The courtesans do not help with trying to get the Empress to be less spoiled, by the way. They offer to do almost everything for her, even brush her hair as that’s Ganyu and Keqing’s favorite thing to do when the Empress wakes up.

What’s funny is that the Empress is gifted in school smarts. She’s exceptionally smart when dealing with wars, trade negotiations, reading people, etc. but she can’t really cook, clean, or navigate her way through a large area without getting lost 😭😭

Well, I suppose she can’t be good at everything…

#🫧feeding the fishes#empress au#empress au lore dump#but she’s a prodigy in the arts as well#other than being able to do sew and play a variety of chinese instruments#she is not very street smart

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

🦚 Phoenix Crown (Fengguan) | 鳳冠 🦚

A type of Chinese crown worn by noble women for official ceremonies. It’s made out of kingfisher feather, gold, pearls, and precious gems like rubies, sapphires, and more.

2+3+4 drama title: Palace of Devotion 大宋宫词

#chinese culture#chinese history#crowns#jewelry#asian culture#east asia#China#precious gems#gold#pearls#culture#empress#chinese hanfu#hanfu#chinese drama#cdrama#east asian cultures#dynastic china#fengguan#Phoenix crown

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

Battle of the Barbies! Round 7: Historical (Sub Round 2)

This is round 7 (sub round 2) of the bracket. All other polls in can be found here.

#Battle of the barbies#barbie#barbies#barbie doll#barbie dolls#barbie collectibles#barbie collector#barbie core#doll#dolls#dollcore#doll collector#doll collection#doll community#my post#non disney#polls#historical dolls#historical barbies#chinese empress#elizabethan queen

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Coat, said to have belonged to Empress Dowager Cixi

c.1890-1900 (Qing Dynasty)

China

Royal Ontario Museum (Object number: 919.6.128)

#coat#fashion history#historical fashion#cixi#chinese fashion#non western fashion#1890s#1900s#blue#embroidery#19th century#20th century#silk#satin#empress cixi#empress dowager cixi#royal ontario museum#popular

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Married Mongolian Women’s Hairstyle in the Yuan Dynasty

Mongolians have a long history of shaving and cutting their hair in specific styles to signal socioeconomic, marital, and ethnic status that spans thousands of years. The cutting and shaving of the hair was also regarded as an important symbol of change and transition. No Mongolian tradition exemplifies this better than the first haircut a child receives called Daah Urgeeh, khüükhdiin üs avakh (cutting the child’s hair), or örövlög ürgeekh (clipping the child’s crest) (Mongulai, 2018)

The custom is practiced for boys when they are at age 3 or 5, and for girls at age 2 or 4. This is due to the Mongols’ traditional belief in odd numbers as arga (method) [also known as action, ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠤᠯ, арга] and even numbers as bilig (wisdom) [ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ, билиг].

Mongulai, 2018.

The Mongolian concept of arga bilig (see above) represents the belief that opposite forces, in this case action [external] and wisdom [internal], need to co-exist in stability to achieve harmony. Although one may be tempted to call it the Mongolian version of Yin-Yang, arga bilig is a separate concept altogether with roots found not in Chinese philosophy nor Daoism, but Eurasian shamanism.

However, Mongolian men were not the only ones who shaved their hair. Mongolian women did as well.

Flemish Franciscan missionary and explorer, William of Rubruck [Willem van Ruysbroeck] (1220-1293) was among the earliest Westerners to make detailed records about the Mongol Empire, its court, and people. In one of his accounts he states the following:

But on the day following her marriage, (a woman) shaves the front half of her head, and puts on a tunic as wide as a nun's gown, but everyway larger and longer, open before, and tied on the right side. […] Furthermore, they have a head-dress which they call bocca [boqtaq/gugu hat] made of bark, or such other light material as they can find, and it is big and as much as two hands can span around, and is a cubit and more high, and square like the capital of a column. This bocca they cover with costly silk stuff, and it is hollow inside, and on top of the capital, or the square on it, they put a tuft of quills or light canes also a cubit or more in length. And this tuft they ornament at the top with peacock feathers, and round the edge (of the top) with feathers from the mallard's tail, and also with precious stones. The wealthy ladies wear such an ornament on their heads, and fasten it down tightly with an amess [J: a fur hood], for which there is an opening in the top for that purpose, and inside they stuff their hair, gathering it together on the back of the tops of their heads in a kind of knot, and putting it in the bocca, which they afterwards tie down tightly under the chin.

Ruysbroeck, 1900

TLDR: Mongolian women shaved the front half of their head and covered it with a boqta, the tall Mongolian headdress worn by noblewomen throughout the Mongol empire. Rubruck observed this hairstyle in noblewomen (boqta was reserved only for noblewomen). It’s not clear whether all women, regardless of status, shaved the front of their heads after marriage and whether it was limited to certain ethnic groups.

When I learned about that piece of information, I was simply going to leave it at that but, what actually motivated me to write this post is to show what I believe to be evidence of what Rubruck described. By sheer coincidence, I came across these Yuan Dynasty empress paintings:

Portrait of Empress Dowager Taji Khatun [ᠲᠠᠵᠢ ᠬᠠᠲᠤᠨ, Тажи xатан], also known as Empress Zhaoxian Yuansheng [昭獻元聖皇后] (1262 - 1322) from album of Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk, Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368). National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan [image source].

Portrait of Unnamed Imperial Consort from album Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk. Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368). National Palace Mueum in Taiper, Taiwan [image source].

Portrait of unnamed wife of Gegeen Khan [ᠭᠡᠭᠡᠨ ᠬᠠᠭᠠᠨ, Гэгээн хаан], also known as Shidibala [ᠰᠢᠳᠡᠪᠠᠯᠠ, 碩德八剌] and Emperor Yingzong of Yuan [英宗皇帝] (1302-1323) from album Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk. Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368), early 14th century. National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan [image source].

To me, it’s evident that the hair of those women is shaved at the front. The transparent gauze strip allows us to clearly see their hairstyle. The other Yuan empress portraits have the front part of the head covered, making it impossible to discern which hairstyle they had. I wonder if the transparent gauze was a personal style choice or if it was part of the tradition such that, after shaving the hair, the women had to show that they were now married by showcasing the shaved part.

As shaving or cutting the hair was a practice linked by nomads with transitioning or changing from one state to another (going from being single to married, for example), it would not be a surprise if the women regrew it.

References:

Mongulai. (2018, April 19). Tradition of cutting the hair of the child for the first time.

Ruysbroeck, W. V. & Giovanni, D. P. D. C., Rockhill, W. W., ed. (1900) The journey of William of Rubruck to the eastern parts of the world, 1253-55, as narrated by himself, with two accounts of the earlier journey of John of Pian de Carpine. Hakluyt Society London. Retrieved from the University of Washington’s Silk Road texts.

#mongolia#mongolian#yuan dynasty#mongolian history#chinese history#china#boqta#mongolian traditions#history#gegeen khan#empress dowager taji#mongol empire#William of Rubruck#historical fashion#arga bilig#central asia#central asian culture#mongolian culture#asia

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

#the legend of zhen huan#empresses in the palace#легенда про чжень хуань#дорами українською#chinese drama#cdramaedit#perioddramaedit#onlyperioddramas#qing dynasty#sunli#bettysun#vigilante shit

22 notes

·

View notes

Video

【Historical Artifact Reference】:

Ming Dynasty Royal Portrait:

・Portrait of Empress Xiaoduanxian (Chinese: 孝端顯皇后; 7 November 1564 – 7 May 1620) In ceremonial dress (翟衣/di yi)

・Nine Dragons and Nine Phoenix Crowns of Empress Xiaoduanxian (※This Phoenix Crowns only for important ceremonial occasion which call “礼冠/Li Guan” wear with ceremonial dress(翟衣/di yi)

----

Unearthed from Ming Dynasty royal mausoleum Ming Dingling (明定陵) , is a mausoleum wehre Wanli Emperor, together with his two empresses Wang Xijie and Dowager Xiaojing, was buried.

In addition to this phoenix crown, the Empress has another phoenix crown for other occasions.

----

Collection of the National Museum of China.

This phoenix crown is 35.5 cm high, 20 cm in diameter, and weighs more than 2,000 grams. It is inlaid with hundreds of high-quality gemstones of various colors and decorated with more than 5,000 fine pearls.

[Hanfu・漢服]Chinese Ming Dynasty Traditional Clothing Hanfu (翟衣) & Phoenix Crown (鳳冠) Reference to Ming Dynasty Relics & Empress Portrait

—–

【History Note】

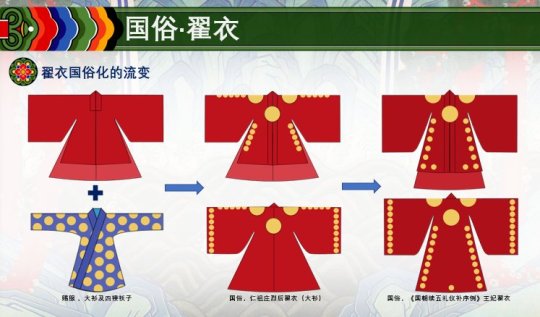

Diyi (Chinese: 翟衣), also called known as huiyi (褘衣) and miaofu (Chinese: 庙服), is the historical Chinese attire worn by the empresses of the Song dynasty and by the empresses and crown princesses (wife of crown prince) in the Ming Dynasty.

The Diyi also had different names based on its colour, such as yudi, quedi, and weidi. It is a formal wear meant only for ceremonial purposes. It is a form of shenyi (Chinese: 深衣), and is embroidered with long-tail pheasants (Chinese: 翟; pinyin: dí or Chinese: 褘; pinyin: hui) and circular flowers (Chinese: 小輪花; pinyin: xiǎolúnhuā). It is worn with guan known as fengguan (lit. 'phoenix crown') which is typically characterized by the absence of dangling string of pearls by the sides. It was first recorded as Huiyi in the Zhou dynasty(1050–221 BCE).

The Diyi follows the traditional Confucian standard system for dressing, which is embodied in its form through the shenyi(深衣) system. The garment known as shenyi(深衣) is itself the most orthodox style of clothing in traditional Chinese Confucianism; its usage of the concept of five colours, and the use of di-pheasant bird pattern.

【 Influence to Other Country】

Korea

Korean queens started to wear the Diyi (Korean: 적의; Hanja: 翟衣) in 1370 AD under the final years of Gongmin of Goryeo,when Goryeo adopted the official ceremonial attire of the Ming dynasty. Same as the early Korea Joseon, were bestowed by the Ming Dynasty.

According to the Annals of Joseon, from 1403 to the first half of the 17th century the Ming Dynasty sent a letter, which confers the korea queen with a title along with the following items: 翟冠(Ming womens whose husband held the highest government official posts can wear this kind of crown,different from Ming Empress Phoenix Crown 鳳冠), a vest called 褙子(Beizi), and a 霞帔(Xiapei). However, the Diyi sent by the Ming dynasty did not correspond to those worn by the Ming empresses as Joseon was considered to be ranked two ranks lower than Ming.

Instead the Diyi which was bestowed corresponded to the Ming women's whose husband held the highest government official posts. In the early Ming Dynasty period, the Diyi were given to Korea Joseon By Ming, but after the Ming Dynasty reformed the clothing system, The Ming Dynasty bestow the 大衫( Dà shān) to the Korean queen instead of Diyi. The Diyi worn by the Korean queen and crown princess was originally made of red silk; it then became blue in 1897 when the Joseon king and queen were elevated to the status of emperor and empress.

it then became blue in 1897 when the Joseon king and queen were elevated to the status of emperor and empress.

After the fall of the Ming Dynasty, the system of China granting clothing to Korea was interrupted. Korea Joseon were forced to become tributary state of the Qing Dynasty. Korea Joseon carried out "nationalization" based on the costumes bestowed by the Ming Dynasty in the past. But according <Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty Volume 46> "嬪宮冊禮時, 旣有翟衣, 則當有翟冠, 而我國匠人不解翟冠之制。 考諸《謄錄》, 則宣廟朝壬寅年嘉禮時, 都監啓以: ‘七翟冠之制, 非但匠人未有解知者, 各樣等物, 必須貿取於中朝, 而終難自本國製造, 何以爲之?’ 云則宣庙有: ‘冠則制造爲難。’ 之敎。 “

Although Korea Joseon has Diyi,but no craftsman know how to make 翟冠(Di Guan), and the materials needed for make 翟冠(Di Guan) need to be taken from China (which need money for that). After all, it is difficult to manufacture in Korea. Therefore, Korea Joseon has not worn 翟冠(Di Guan) since the fall of the Ming Dynasty and change it to 대수머리(大首머리)

Korea "nationalization" process↓

대수머리(大首머리)

Japan

In Japan, the features of the Tang dynasty-style huiyi was found as a textile within the formal attire of the Heian Japanese empresses.

————————

📝Recreation Work & Hanfu: @执月传统服饰 & @鱼墨呀

📸Photo: @执月传统服饰 & @鱼墨呀

🛍️Tabao:https://item.taobao.com/item.htm?spm=a230r.1.14.16.1edc69a6bumOJ8&id=636369495576&ns=1&abbucket=16#detail

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/7454398796/K4mehzhsg

————————

#Chinese Hanfu#Ming Dynasty#chinese fashion history#Chinese Culture#Phoenix Crown 鳳冠#Di yi/翟衣#chinese#chinese historical fashion#Empress Xiaoduanxian#Nine Dragons and Nine Phoenix Crowns#Sinosphere#hanfu history#China History

344 notes

·

View notes