#bill borzage

Photo

Janet Gaynor on her way to lunch on the Fox lot.

Notice the escorts, Director Frank Borzage, Charlie Farrell and Director Bill Howard.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

NOIR CITY returns for its sixth year to Detroit’s historic @Redford Theatre, September 22 - 24 with a 75th-anniversary focus on films from 1948. Film Noir Foundation president Eddie Muller will host all eight screenings, as well as sign copies of his latest book "Eddie Muller’s Noir Bar: Cocktails Inspired by the World of Film Noir" at 7:00 p.m. on opening night.

Festival schedule, individual tickets for double features, and passes are available at https://redfordtheatre.com/events/

Two 35mm presentations open the festival screenings at 8:00 p.m. on Friday, September 22-- John Huston’s "Key Largo" featuring an all-star cast—Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, and Edward G. Robinson—is paired with Anthony Mann’s beautiful-but-gritty "Raw Deal". Saturday offers up a matinée and an evening double feature. Anatole Litvak’s suspenseful "Sorry, Wrong Number" starring the inimitable Barbara Stanwyck and Jean Negulesco’s love triangle gone wrong tale Road House play in the afternoon. Robert Wise’s "Odds Against Tomorrow" (1959) anchors the evening’s double bill and is preceded by a tribute to Harry Belafonte who co-starred with Robert Ryan in Wise’s explosive heist film. Nicholas Ray’s tender tragedy "They Live by Night" ends the day. A Sunday matinée double feature finishes off the festivities: John Farrow’s nail-biting "The Big Clock" and Frank Borzage’s haunting Southern Gothic noir "Moonrise".

The NOIR CITY: Detroit All-Access Pass (only $50!) provides entry to all eight films, a commemorative poster, PLUS a private reception and onstage Q&A with Eddie Muller on Saturday night, September 23, 5:30 p.m. at the Redford Theatre. The All-Access pass also grants early admission (6:30 p.m.) for the 7:00 p.m. Friday night book signing of Eddie 's book signing The All-Access Pass is only available at https://redfordtheatre.com/events/noir-city-detroit-all-access-pass/

4 notes

·

View notes

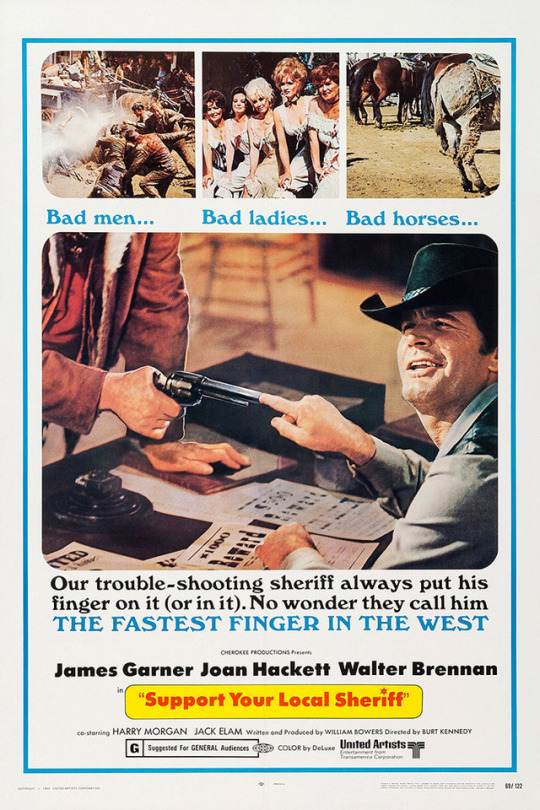

Photo

Bad movie I have Support your Local Sheriff 1969

#Support your Local Sheriff#Cherokee Productions#James Garner#Joan Hackett#Walter Brennan#Harry Morgan#Jack Elam#Henry Jones#Bruce Dern#Willis Bouchey#Gene Evans#Walter Burke#Dick Peabody#Chubby Johnson#Kathleen Freeman#Dick Haynes#Richard Alden#Robert Anderson#Bill Borzage#Forest Burns#Bill Catching#Roydon Clark#Gene Coogan#John Daheim#Fred Dale#Luis Delgado#Ken DuMain#Jaye Durkus#Marilyn Jones#Jack Lilley

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Support Your Local Sheriff 1969

#support your local sheriff#james garner#jack elam#joan hackett#walter brennen#harry morgan#henry jones#bruce dern#willis bouchey#gene evans#walter burke#dick peabody#chubby johnson#kathleen freeman#dick haynes#richard alden#robert anderson#bill borzage#danny borzage#forest burns#bill catching#roydon clark#gene coogan#john daheim#richard hoyt#john milford#joe phillips#tom reese#william tannen#jack tornek

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

i’ve always loved you (us, borzage 46)

#i've always loved you#frank borzage#catherine mcleod#bill carter#maria ouspenskaya#vanessa brown#tony gaudio

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pioneering Black Actors of Hollywood By Susan King

Clarence Muse and Rex Ingram by Susan King Thirty years ago, the legendary Oscar-winning actor Sidney Poitier reflected on the Black performers who paved the way for him in the Los Angeles Times: “The guys who were forerunners to me, like Canada Lee, Rex Ingram, Clarence Muse and women like Hattie McDaniel, Louise Beavers and Juanita Moore, they were terribly boxed in. They were maids and stable people and butlers, principally. But they, in some way, prepared the ground for me.”

Poitier prepared the ground for such contemporary Black actors and directors currently in competition during the 2021 awards season such as Regina King and Leslie Odom Jr. (One Night in Miami), Delroy Lindo (Da 5 Bloods), the late Chadwick Boseman and Viola Davis (Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom), Andra Day (The United States vs. Billie Holiday) and Daniel Kaluuya (Judas and the Black Messiah).

But it is imperative to remember the veterans from the 1930s-1960s who tried to break out of stereotypes and maintain dignity at a time when Hollywood wanted to “box” them in.

Clarence Muse

Muse appeared in countless Hollywood films often uncredited. And as Donald Bogle points out in his book Hollywood Black, Muse spoke his mind to directors if he felt he was being pushed around or when his characters were stereotypes. Bogle stated, “At another time when Muse questioned the actions of his character in director King Vidor’s 1935 Old South feature SO RED THE ROSE, Vidor recalled that Muse was quite vocal in expressing his concerns. A change was made. Vidor could not recall exactly what the issue was, but he never forgot Muse’s objection.”

The 1932 pre-Code crime drama Night World screened at the 2019 TCM Classic Film Festival to a standing-room only crowd. The film stars Lew Ayres, Boris Karloff and Muse as the doorman at a club owned by Karloff. The audience was surprised that such a stereotypical role was anything but thanks to Muse’s poignant performance. Instead of being forced to be the comic relief, Muse’s Washington is a man worried about his wife’s surgery at a local hospital. Though his boss doesn’t treat him as an equal—after all it is 1932—Karloff’s Happy shows general concern toward Washington.

Muse, said Bogle, “also worked in race movies, where he realized there was still a real chance for significant roles and narratives.” One such was BROKEN STRINGS (’40), which he also co-wrote. It’s certainly not a great film, but Muse gives a solid turn as a famed Black violinist who wants his young son to follow in his footsteps. But the son wants to play swing with his violin.

Muse, who was a graduate of Dickinson College in Pennsylvania, also co-wrote the Louis Armstrong standard “Sleepy Time Down South.” In the 1920s, he worked at two Harlem theater companies, Lincoln Players and Lafayette Players, and 23 years later he became the first African American Broadway director with Run Little Chillun. He continued to act, appearing in Poitier’s directorial debut BUCK AND THE PREACHER (’72), CAR WASH (’76) and THE BLACK STALLION (’79) and was elected to the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame in 1973. He died one day before his 90th birthday in 1979.

Rex Ingram

Tall and imposing, Ingram had a great presence on the big screen and a rich melliferous voice. No wonder his best-known role was as the gigantic Genie in the bottle in Alexander Korda’s lavish production of THE THIEF OF BAGDAD (’40). Born in 1895, he began his film career in movies such as Cecil B. DeMille’s THE TEN COMMANDMENTS (’23). Ingram also has the distinction of playing God in THE GREEN PASTURES (’36) and Lucifer Jr. both on Broadway in 1940 and in the 1943 film adaptation of the musical CABIN IN THE SKY.

Ingram also brought a real humanity to his role as the slave Jim in MGM’s disappointing THE ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN (’39), starring a miscast Mickey Rooney, who was way too old at 19 to play the part. Ingram, though, breaks your heart when he talks to Huck about how his dream is to earn enough money to buy his freedom so he could join his wife and child living in a free state. And when he runs away, Ingram explains to Huck why he had to flee the widow Douglas: “If one of them slave traders got me, I never would get to that free state. I would never see my wife, or little Joey.”

He also is superb in Frank Borzage’s noir MOONRISE (’48) as Mose Johnson, the friend of the murderer’s son Danny (Dane Clark), who lives in a shack in the wilderness with his coonhounds. Noble and thoughtful, Mose is the film’s conscience and helps guide Danny to do the right thing after he kills a bully (Lloyd Bridges) in self-defense.

Ingram was one of the busiest Black actors at the time and at one point even served on the Board of the Screen Actors Guild. But the same year MOONRISE was released, he was arrested and pleaded guilty for transporting an underage girl from Kansas to New York. He served a prison sentence and for a long time his career was derailed. He even lost his home. Though his film career was never the same upon his release, he worked in TV and on the Broadway stage, appearing in Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, and died in 1969 at 73 shortly after doing a guest shot on NBC’s The Bill Cosby Show.

Ernest Anderson

Anderson never achieved the notoriety of Muse and Ingram, but the actor gave an extraordinary performance in the Bette Davis-Olivia de Havilland melodrama IN THIS OUR LIFE (’42) directed by John Huston. Born in 1915, Anderson earned his BA at Northwestern University in drama and speech. He was recommended for his role in the movie by Davis, who saw the young man working at the commissary on the Warner Bros.’ lot.

Anderson plays Parry, the son of the Davis-de Havilland family’s maid who aspires to be a lawyer. Davis’ spoiled rotten Stanley Timberlake gets drunk, and while driving she kills someone in a hit-and-run accident. Stanley throws Parry under the bus telling authorities he was the one driving the car.

Initially, the script depicted Parry in much more stereotypical terms, but Anderson went to Huston and discussed why he wanted to play the character with dignity and intelligence. Huston agreed. And for 1942, it’s rather shocking to see a studio film look at racism as in the scene where Parry tells de Havilland’s Roy why he wants to be an attorney:

“Well, you see, it’s like this, Miss Roy: a white boy, he can take most any kind of job and improve himself. Well, like in this store! Maybe he can get to be a clerk or a manager. But a colored boy, he can’t do that. He can keep a job, or he can lose a job. But he can’t get any higher up. So, he’s got a figure out something he can do that no one can take away. And that’s why I want to be a lawyer.”

Needless to say, such monologues were cut when the movie was shown in the South. Despite strong reviews for his performance, Anderson never got another role with so much substance. But he continued working through the 1970s and died in 2011 at the age of 95.

#Clarence Muse#Rex Ingram#Ernest Anderson#Bette Davis#Warner Bros#Black actors#Hollywood Black#TCM#Turner Classic Movies#black representation#Susan King

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

films on youtube: part i

Updated on September 29th 2021.

Below is a selection of films available on YouTube. As I try to update this list as regularly as possible (for this is a lenghthy process), please refer to the original post for the newest version.

IMPORTANT NOTE: Apparently, Tumblr restricts the number of links you can have all on one post. Therefore, this list is divided into two parts. You can access part two by clicking on the link below:

PART II HERE.

For a visual reference of all the movies available, click here.

Titles are alphabetized by director, and organized by year of release.

Gozāresh (1977), Abbas Kiarostami

Close-Up (1990), Abbas Kiarostami

Taste of Cherry (1997), Abbas Kiarostami

Shirin (2008), Abbas Kiarostami

Dreams (1990), Akira Kurosawa

Trans-Europ-Express (1966), Alain Robbe-Grillet

L'Homme Qui Ment (1968), Alain Robbe-Grillet

Rien Que Les Heures (1926), Alberto Cavalcanti

They Made Me a Fugitive (1947), Alberto Cavalcanti

Downhill (1927), Alfred Hitchcock

The Lodger (1927), Alfred Hitchcock

Elstree Calling (1930), Alfred Hitchcock and Adrian Brunel

The 39 Steps (1935), Alfred Hitchcock

Sabotage (1936), Alfred Hitchcock

Young and Innocent (1937), Alfred Hitchcock (Part I / Part II)

The Lady Vanishes (1938), Alfred Hitchcock

Rebecca (1940), Alfred Hitchcock

Spellbound (1945), Alfred Hitchcock

Notorious (1946), Alfred Hitchcock

The Paradine Case (1947), Alfred Hitchcock

Under Capricorn (1949), Alfred Hitchcock

The Trouble with Harry (1955), Alfred Hitchcock

Salomé (1923), Alla Nazimova and Charles Bryant

Goodbye Again (1961), Anatole Litvak

Ivan’s Childhood (1962), Andrei Tarkovsky

Andrei Rublev (1966), Andrei Tarkovsky (Part I / Part II)

Solaris (1972), Andrei Tarkovsky (Part I / Part II)

Stalker (1979), Andrei Tarkovsky

Nostalghia (1983), Andrei Tarkovsky

The Sacrifice (1986), Andrei Tarkovsky

Very Nice, Very Nice (1961), Arthur Lipsett

21-87 (1963), Arthur Lipsett

A Trip Down Memory Lane (1965), Arthur Lipsett

The Chase (1946), Arthur Ripley

A Separation (2011), Asghar Farhadi

Werckmeister Harmonies (2000), Béla Tarr

The Turin Horse (2011), Béla Tarr

Un Homme Qui Dort (1974), Bernard Queysanne

Il Conformista (1970), Bernardo Bertolucci

By the Bluest of Seas (1936), Boris Barnet

Sherlock Holmes Jr. (1924), Buster Keaton

The General (1926), Buster Keaton

Steamboat Bill (1928), Buster Keaton

Mikaël (1924), Carl Theodor Dryer

Love One Another (1922), Carl Theodor Dryer

Night Train to Munich (1940), Carol Reed

The Way Ahead (1944), Carol Reed

Odd Man Out (1947), Carol Reed

The Running Man (1963), Carol Reed

Behind the Screen (1916), Charles Chaplin

The Gold Rush (1925), Charles Chaplin

City Lights (1931), Charles Chaplin

Modern Times (1936), Charles Chaplin

Monsieur Verdoux (1947), Charles Chaplin

Statues Also Die (1953), Chris Marker, Alain Resnais and Ghislain Cloquet

La Jetée (1962), Chris Marker

Sans Soleil (1983), Chris Marker

If I Had Four Dromedaries (1966), Chris Marker

The Seventh Veil (1945), Compton Bennett

Come Back, Little Sheba (1952), Daniel Mann

Brief Encounter (1945), David Lean

Oliver Twist (1948), David Lean

Madeleine (1950), David Lean

Summertime (1955), David Lean

Il Sorpasso (1962), Dino Risi

The Monsters (1963), Dino Risi

Shockproof (1949), Douglas Sirk

Interlude (1957), Douglas Sirk

Man With a Movie Camera (1929), Dziga Vertov

Twenty Years Later (1984), Eduardo Coutinho

Mikey and Nicky (1976), Elaine May

Agony: The Life and Death of Rasputin (1981), Elem Klimov

Come and See (1985), Elem Klimov

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945), Elia Kazan

A Face in the Crowd (1957), Elia Kazan

The Kreutzer Sonata (1956), Éric Rohmer

Stéphane Mallarmé (1968), Éric Rohmer

Ninotchka (1939), Ernst Lubitsch

That Uncertain Feeling (1941), Ernst Lubitsch

Journey Into the Night (1921), F.W. Murnau

Faust (1926), F.W. Murnau

Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), F.W. Murnau

City Girl (1930), F. W. Murnau

Tabu (1931), F. W. Murnau

Love in the City (1953), Federico Fellinni …

La Strada (1954), Federico Fellini

The Swindlers (1955), Federico Fellini

Nostos: The Return (1989), Franco Piavoli

Voices Through Time (1996), Franco Piavoli

Landscapes and Figures (2002), Franco Piavoli

Fragments (2012), Franco Piavoli

7th Heaven (1927), Frank Borzage

A Farewell to Arms (1932), Frank Borzage

Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), Frank Capra

Meet John Doe (1941), Frank Capra

Marketa Lazarová (1967), František Vláčil

Die Nibelungen: Siegfired (1924), Fritz Lang

Die Nibelungen: Kriemhilds Rache (1924), Fritz Lang

Metropolis (1927), Fritz Lang

M (1931), Fritz Lang

Hangmen Also Die (1943), Fritz Lang

Scarlet Street (1945), Fritz Lang

Cloak and Dagger (1946), Fritz Lang

House by the River (1950), Fritz Lang

Major Barbara (1941), Gabriel Pascal

The Cigarette (1919), Germaine Dulac

The Battle of Algiers (1966), Gillo Pontecorvo

Coração Materno (1951), Gilda de Abreu

Death Laid an Egg (1968), Giulio Questi

Intermezzo: A Love Story (1939), Gregory Ratoff

Simple Men (1992), Hal Hartley

Hamlet (1921), Heinz Schall and Svend Gade

Kiss of Death (1947), Henry Hathaway

Woman in the Dunes (1964), Hiroshi Teshigahara

After Life (1998), Hirozaku Kore-eda

Bringing Up Baby (1938), Howard Hawks

His Girl Friday (1940), Howard Hawks

Hard, Fast and Beautiful (1951), Ida Lupino

The Hitch-Hiker (1953), Ida Lupino

Crisis (1946), Ingmar Bergman

Summer Interlude (1951), Ingmar Bergman

Summer With Monika (1953), Ingmar Bergman

The Seventh Seal (1957), Ingmar Bergman

Wild Strawberries (1957), Ingmar Bergman

The Virgin Spring (1960), Ingmar Bergman

Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Ingmar Bergman

The Silence (1963), Ingmar Bergman

Winter Light (1963), Ingmar Bergman

Persona (1966), Ingmar Bergman

Hour of the Wolf (1968), Ingmar Bergman

Shame (1968), Ingmar Bergman

The Passion of Anna (1969), Ingmar Bergman

Cries and Whispers (1972), Ingmar Bergman

La Belle Noiseuse (1991), Jacques Rivette

Playtime (1967), Jacques Tati

Man Friday (1975), Jack Gold

Diamonds of the Night (1964), Jan Němec

Who Saw Him Die? (1968), Jan Troell

The Flight of the Eagle (1982), Jan Troell

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1970), Jaromil Jireš

7K notes

·

View notes

Photo

I’ve always loved you (Frank Borzage, 1946)

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hedy Lamarr, born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler (November or September 9, 1914 – January 19, 2000), was an Austrian-American actress, inventor, and film producer. She appeared in 30 films over a 28 year career, and co-invented an early version of frequency-hopping spread spectrum communication.

Lamarr was born in Vienna, Austria-Hungary, and acted in a number of Austrian, German, and Czech films in her brief early film career, including the controversial Ecstasy (1933). In 1937, she fled from her husband, a wealthy Austrian ammunition manufacturer, secretly moving to Paris and then on to London. There she met Louis B. Mayer, head of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) studio, who offered her a Hollywood movie contract, where he began promoting her as "the world's most beautiful woman".

She became a star through her performance in Algiers (1938), her first United States film.[5] She starred opposite Clark Gable in Boom Town and Comrade X (both 1940), and James Stewart in Come Live with Me and Ziegfeld Girl (both 1941). Her other MGM films include Lady of the Tropics (1939), H.M. Pulham, Esq. (1941), as well as Crossroads and White Cargo (both 1942); she was also borrowed by Warner Bros. for The Conspirators, and by RKO for Experiment Perilous (both 1944). Dismayed by being typecast, Lamarr co-founded a new production studio and starred in its films: The Strange Woman (1946), and Dishonored Lady (1947). Her greatest success was as Delilah in Cecil B. DeMille's Samson and Delilah (1949). She also acted on television before the release of her final film, The Female Animal (1958). She was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960.

At the beginning of World War II, Lamarr and composer George Antheil developed a radio guidance system using frequency-hopping spread spectrum technology for Allied torpedoes, intended to defeat the threat of jamming by the Axis powers. She also helped improve aircraft aerodynamics for Howard Hughes while they dated during the war. Although the US Navy did not adopt Lamarr and Antheil's invention until 1957, various spread-spectrum techniques are incorporated into Bluetooth technology and are similar to methods used in legacy versions of Wi-Fi. Recognition of the value of their work resulted in the pair being posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2014.

Lamarr was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in 1914 in Vienna, Austria-Hungary, the only child of Emil Kiesler (1880–1935) and Gertrud "Trude" Kiesler (née Lichtwitz; 1894–1977). Her father was born to a Galician-Jewish family in Lemberg (now Lviv, Ukraine), and was a successful bank manager. Her mother was a pianist, born in Budapest to an upper-class Hungarian-Jewish family. She converted to Catholicism as an adult, at the insistence of her first husband, and raised her daughter Hedy as a Catholic as well, though she was not formally baptized at the time.

As a child, Kiesler showed an interest in acting and was fascinated by theatre and film. At the age of 12, she won a beauty contest in Vienna. She also began to associate invention with her father, who would take her out on walks, explaining how various technologies in society functioned.

After the Anschluss, she helped get her mother out of Austria and to the United States, where Gertrud Kiesler later became an American citizen. She put "Hebrew" as her race on her petition for naturalization, a term that had been frequently used in Europe.

Still using her maiden name of Hedy Kiesler, she took acting classes in Vienna. One day, she forged a permission note from her mother and went to Sascha-Film, where she was hired at the age of 16 as a script girl. She gained a role as an extra in Money on the Street (1930), and then a small speaking part in Storm in a Water Glass (1931). Producer Max Reinhardt cast her in a play entitled The Weaker Sex, which was performed at the Theater in der Josefstadt. Reinhardt was so impressed with her that he arranged for her to return with him to Berlin, where he was based.

Kiesler never trained with Reinhardt nor appeared in any of his Berlin productions. After meeting Russian theatre producer Alexis Granowsky, she was cast in his film directorial debut, The Trunks of Mr. O.F. (1931), starring Walter Abel and Peter Lorre. Granowsky soon moved to Paris, but Kiesler stayed in Berlin to work. She was given the lead role in No Money Needed (1932), a comedy directed by Carl Boese. Her next film brought her international fame.

In early 1933, at age 18, Hedy Kiesler, still working under her maiden name, was given the lead in Gustav Machatý's film Ecstasy (Ekstase in German, Extase in Czech). She played the neglected young wife of an indifferent older man.

The film became both celebrated and notorious for showing the actress's face in the throes of an orgasm. According to Marie Benedict's book The Only Woman In The Room, Kiesler's expression resulted from someone sticking her with a pin. She was also shown in closeups and brief nude scenes, the latter reportedly a result of the actress being "duped" by the director and producer, who used high-power telephoto lenses.

Although Kiesler was dismayed and now disillusioned about taking other roles, Ecstasy gained world recognition after winning an award in Rome. Throughout Europe, the film was regarded as an artistic work. However, in the United States, it was banned, considered overly sexual, and made the target of negative publicity, especially among women's groups. It was also banned in Germany due to Kiesler's Jewish heritage. Her husband, Fritz Mandl, reportedly spent over $300,000 buying up and destroying copies of the film.

Kiesler also played a number of stage roles, including a starring one in Sissy, a play about Empress Elisabeth of Austria produced in Vienna in early 1933, just as Ecstasy premiered. It won accolades from critics.

Admirers sent roses to her dressing room and tried to get backstage to meet Kiesler. She sent most of them away, including an insistent Friedrich Mandl. He became obsessed with getting to know her. Mandl was a Viennese arms merchant and munitions manufacturer who was reputedly the third-richest man in Austria. She fell for his charming and fascinating personality, partly due to his immense wealth. Her parents, both of Jewish descent, did not approve, as Mandl had ties to Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini, and later, German Führer Adolf Hitler, but they could not stop their headstrong daughter.

On August 10, 1933, at the age of 18, Kiesler married Mandl, then 33. The son of a Jewish father and a Catholic mother, Mandl insisted that she convert to Catholicism before their wedding in Vienna Karlskirche. In her autobiography Ecstasy and Me, Mandl is described as an extremely controlling husband. He strongly objected to her having been filmed in the simulated orgasm scene in Ecstasy and prevented her from pursuing her acting career. She claimed she was kept a virtual prisoner in their castle home, Castle Schwarzenau in the remote Waldviertel near the Czech border.

Mandl had close social and business ties to the Italian government, selling munitions to the country, and, despite his own part-Jewish descent, had ties to the Nazi regime of Germany. Kiesler accompanied Mandl to business meetings, where he conferred with scientists and other professionals involved in military technology. These conferences were her introduction to the field of applied science and she became interested in nurturing her latent talent in science.

Finding her marriage to Mandl eventually unbearable, Kiesler decided to flee her husband as well as her country. According to her autobiography, she disguised herself as her maid and fled to Paris. Friedrich Otto's account says that she persuaded Mandl to let her wear all of her jewelry for a dinner party where the influential austrofascist Ernst Stahremberg attended, then disappeared afterward. She writes about her marriage:

I knew very soon that I could never be an actress while I was his wife. ... He was the absolute monarch in his marriage. ... I was like a doll. I was like a thing, some object of art which had to be guarded—and imprisoned—having no mind, no life of its own.

After arriving in London in 1937, she met Louis B. Mayer, head of MGM, who was scouting for talent in Europe. She initially turned down the offer he made her (of $125 a week), but booked herself onto the same New York-bound liner as he. During the trip, she impressed him enough to secure a $500 a week contract. Mayer persuaded her to change her name from Hedwig Kiesler (to distance herself from "the Ecstasy lady" reputation associated with it). She chose the surname "Lamarr" in homage to the beautiful silent film star, Barbara La Marr, on the suggestion of Mayer's wife, Margaret Shenberg.

When Mayer brought Lamarr to Hollywood in 1938, he began promoting her as the "world's most beautiful woman". He introduced her to producer Walter Wanger, who was making Algiers (1938), an American version of the noted French film, Pépé le Moko (1937).

Lamarr was cast in the lead opposite Charles Boyer. The film created a "national sensation", says Shearer. Lamarr was billed as an unknown but well-publicized Austrian actress, which created anticipation in audiences. Mayer hoped she would become another Greta Garbo or Marlene Dietrich. According to one viewer, when her face first appeared on the screen, "everyone gasped ... Lamarr's beauty literally took one's breath away."

In future Hollywood films, Lamarr was often typecast as the archetypal glamorous seductress of exotic origin. Her second American film was I Take This Woman (1940), co-starring with Spencer Tracy under the direction of regular Dietrich collaborator, Josef von Sternberg. Von Sternberg was fired during the shoot, and replaced by Frank Borzage. The film was put on hold, and Lamarr was put into Lady of the Tropics (1939), where she played a mixed-race seductress in Saigon opposite Robert Taylor. She returned to I Take This Woman, re-shot by W. S. Van Dyke. The resulting film was a flop.

Far more popular was Boom Town (1940) with Clark Gable, Claudette Colbert and Spencer Tracy; it made $5 million MGM promptly reteamed Lamarr and Gable in Comrade X (1940), a comedy film in the vein of Ninotchka (1939), which was another hit.

She was teamed with James Stewart in Come Live with Me (1941), playing a Viennese refugee. Stewart was also featured in Ziegfeld Girl (1941), in which Lamarr, Judy Garland, and Lana Turner played aspiring showgirls; it was a big success.

Lamarr was top-billed in H. M. Pulham, Esq. (1941), although the film's protagonist was the title role played by Robert Young. She made a third film with Tracy, Tortilla Flat (1942). It was successful at the box office, as was Crossroads (1942) with William Powell.

She played the seductive native girl Tondelayo in White Cargo (1942), top-billed over Walter Pidgeon. It was a huge hit. White Cargo contains arguably her most memorable film quote, delivered with provocative invitation: "I am Tondelayo. I make tiffin for you?" This line typifies many of Lamarr's roles, which emphasized her beauty and sensuality while giving her relatively few lines. The lack of acting challenges bored Lamarr, and she reportedly took up inventing to relieve her boredom. In a 1970 interview, Lamarr also remarked that she was paid less because she would not sleep with Mayer.

Lamarr was reunited with Powell in a comedy, The Heavenly Body (1944). She was then borrowed by Warner Bros. for The Conspirators (1944), reuniting several of the actors of Casablanca (1942), which had been inspired in part by Algiers and written with Lamarr in mind as its female lead, though MGM would not lend her out. RKO later borrowed her for a melodrama, Experiment Perilous (1944), directed by Jacques Tourneur.

Back at MGM, Lamarr was teamed with Robert Walker in the romantic comedy Her Highness and the Bellboy (1945), playing a princess who falls in love with a New Yorker. It was very popular, but would be the last film she made under her MGM contract.

Her off-screen life and personality during those years was quite different from her screen image. She spent much of her time feeling lonely and homesick. She might swim at her agent's pool, but shunned the beaches and staring crowds. When asked for an autograph, she wondered why anyone would want it. Writer Howard Sharpe interviewed her and gave his impression:

Hedy has the most incredible personal sophistication. She knows the peculiarly European art of being womanly; she knows what men want in a beautiful woman, what attracts them, and she forces herself to be these things. She has magnetism with warmth, something that neither Dietrich nor Garbo has managed to achieve.

Author Richard Rhodes describes her assimilation into American culture:

Of all the European émigrés who escaped Nazi Germany and Nazi Austria, she was one of the very few who succeeded in moving to another culture and becoming a full-fledged star herself. There were so very few who could make the transition linguistically or culturally. She really was a resourceful human being–I think because of her father's strong influence on her as a child.

Lamarr also had a penchant for speaking about herself in the third person.

Lamarr wanted to join the National Inventors Council, but was reportedly told by NIC member Charles F. Kettering and others that she could better help the war effort by using her celebrity status to sell war bonds.

She participated in a war bond-selling campaign with a sailor named Eddie Rhodes. Rhodes was in the crowd at each Lamarr appearance, and she would call him up on stage. She would briefly flirt with him before asking the audience if she should give him a kiss. The crowd would say yes, to which Hedy would reply that she would if enough people bought war bonds. After enough bonds were purchased, she would kiss Rhodes and he would head back into the audience. Then they would head off to the next war bond rally. In total, Lamarr sold approximately $25 million (over $350 million when adjusted for inflation in 2020) worth of war bonds during a period of 10 days.

After leaving MGM in 1945, Lamarr formed production company Mars Film Corporation with Jack Chertok and Hunt Stromberg, producing two film noir motion pictures which she also starred in: The Strange Woman (1946) as a manipulative seductress leading a son to murder his father, and Dishonored Lady (1947) as a formerly suicidal fashion designer[verification needed] trying to start a new life but gets accused of murder. Her initiative was unwelcomed by the Hollywood establishment, as they were against actors (especially female actors) producing their films independently. Both films grossed over their budgets, but were not large commercial successes.

In 1948, she tried a comedy with Robert Cummings, called Let's Live a Little.

Lamarr enjoyed her greatest success playing Delilah opposite Victor Mature as the biblical strongman in Cecil B. DeMille's Samson and Delilah (1949). A massive critical and commercial success, the film became the highest-grossing picture of 1950 and won two Academy Awards (Best Art Direction and Best Costume Design) of its five nominations. She won critical acclaim for her portrayal of Delilah. Showmen's Trade Review previewed the film before its release and commended Lamarr's performance: "Miss Lamarr is just about everyone's conception of the fair-skinned, dark-haired, beauteous Delilah, a role tailor-made for her, and her best acting chore to date."[48] Photoplay wrote, "As Delilah, Hedy Lamarr is treacherous and tantalizing, her charms enhanced by Technicolor."[49]

Lamarr returned to MGM for a film noir with John Hodiak, A Lady Without Passport (1950), which flopped. More popular were two pictures she made at Paramount, a Western with Ray Milland, Copper Canyon (1950), and a Bob Hope spy spoof, My Favorite Spy (1951).

Her career went into decline. She went to Italy to play multiple roles in Loves of Three Queens (1954), which she also produced. However she lacked the experience necessary to make a success of such an epic production, and lost millions of dollars when she was unable to secure distribution of the picture.

She was Joan of Arc in Irwin Allen's critically panned epic, The Story of Mankind (1957) and did episodes of Zane Grey Theatre ("Proud Woman") and Shower of Stars ("Cloak and Dagger"). Her last film was a thriller The Female Animal (1958).

Lamarr was signed to act in the 1966 film Picture Mommy Dead, but was let go when she collapsed during filming from nervous exhaustion. She was replaced in the role of Jessica Flagmore Shelley by Zsa Zsa Gabor.

Although Lamarr had no formal training and was primarily self-taught, she worked in her spare time on various hobbies and inventions, which included an improved traffic stoplight and a tablet that would dissolve in water to create a carbonated drink. The beverage was unsuccessful; Lamarr herself said it tasted like Alka-Seltzer.

Among the few who knew of Lamarr's inventiveness was aviation tycoon Howard Hughes. She suggested he change the rather square design of his aeroplanes (which she thought looked too slow) to a more streamlined shape, based on pictures of the fastest birds and fish she could find. Lamarr discussed her relationship with Hughes during an interview, saying that while they dated, he actively supported her inventive "tinkering" hobbies. He put his team of scientists and engineers at her disposal, saying they would do or make anything she asked for.

During World War II, Lamarr learned that radio-controlled torpedoes, an emerging technology in naval war, could easily be jammed and set off course.[53] She thought of creating a frequency-hopping signal that could not be tracked or jammed. She conceived an idea and contacted her friend, composer and pianist George Antheil, to help her implement it.[54] Together they developed a device for doing that, when he succeeded by synchronizing a miniaturized player-piano mechanism with radio signals.[40] They drafted designs for the frequency-hopping system, which they patented.[55][56] Antheil recalled:

We began talking about the war, which, in the late summer of 1940, was looking most extremely black. Hedy said that she did not feel very comfortable, sitting there in Hollywood and making lots of money when things were in such a state. She said that she knew a good deal about munitions and various secret weapons ... and that she was thinking seriously of quitting MGM and going to Washington, D.C., to offer her services to the newly established National Inventors Council.

As quoted from a 1945 Stars and Stripes interview, "Hedy modestly admitted she did only 'creative work on the invention', while the composer and author George Antheil, 'did the really important chemical part'. Hedy was not too clear about how the device worked, but she remembered that she and Antheil sat down on her living room rug and were using a silver match box with the matches simulating the wiring of the invented 'thing'. She said that at the start of the war 'British fliers were over hostile territory as soon as they crossed the channel, but German aviators were over friendly territory most of the way to England... I got the idea for my invention when I tried to think of some way to even the balance for the British. A radio controlled torpedo, I thought would do it.'"

Their invention was granted a patent under U.S. Patent 2,292,387 on August 11, 1942 (filed using her married name Hedy Kiesler Markey).[58] However, it was technologically difficult to implement, and at the time the US Navy was not receptive to considering inventions coming from outside the military.[35] Nevertheless, it was classified in the "red hot" category.[59] It was first adapted in 1957 to develop a sonobuoy before the expiration of the patent, although this was denied by the Navy. At the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, an updated version of their design was installed on Navy ships.[60] Today, various spread-spectrum techniques are incorporated into Bluetooth technology and are similar to methods used in legacy versions of Wi-Fi. Lamarr and Antheil's contributions were formally recognized in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Lamarr was married and divorced six times and had three children:

Friedrich Mandl (married 1933–37), chairman of the Hirtenberger Patronen-Fabrik

Gene Markey (married 1939–41), screenwriter and producer. She adopted a boy, James Lamarr Markey (born January 9, 1939) during her marriage with Markey. In 2001, James found out he was the out-of-wedlock son of Lamarr and actor John Loder, whom she later married as her third husband.

John Loder (married 1943–47), actor. James Lamarr Markey was adopted by Loder as James Lamarr Loder. During the marriage, Lamarr and Loder also had two further children: Denise Loder (born January 19, 1945), married Larry Colton, a writer and former baseball player; and Anthony Loder (born February 1, 1947), married Roxanne who worked for illustrator James McMullan. They both appeared in the documentary films Calling Hedy Lamarr (2004), and Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story (2017).

Ernest "Ted" Stauffer (married 1951–52), nightclub owner, restaurateur, and former bandleader

W. Howard Lee (married 1953–60), a Texas oilman (he later married film actress Gene Tierney)

Lewis J. Boies (married 1963–65), Lamarr's divorce lawyer

Following her sixth and final divorce in 1965, Lamarr remained unmarried for the last 35 years of her life.

Lamarr became a naturalized citizen of the United States at age 38 on April 10, 1953. Her autobiography, Ecstasy and Me, was published in 1966. In a 1969 interview on The Merv Griffin Show, she said that she did not write it and claimed that much was fictional. Lamarr sued the publisher in 1966 to halt publication, saying that many details were fabricated by its ghost writer, Leo Guild. She lost the suit. In 1967, Lamarr was sued by Gene Ringgold, who asserted that the book plagiarized material from an article he had written in 1965 for Screen Facts magazine.

In the late 1950s, Lamarr designed and, with husband W. Howard Lee, developed the Villa LaMarr ski resort in Aspen, Colorado. After their divorce, her husband gained this resort

In 1966, Lamarr was arrested in Los Angeles for shoplifting. The charges were eventually dropped. In 1991, she was arrested on the same charge in Florida, this time for stealing $21.48 worth of laxatives and eye drops. She pleaded no contest to avoid a court appearance, and the charges were dropped in return for her promise to refrain from breaking any laws for a year.

During the 1970s, Lamarr lived in increasing seclusion. She was offered several scripts, television commercials, and stage projects, but none piqued her interest. In 1974, she filed a $10 million lawsuit against Warner Bros., claiming that the running parody of her name ("Hedley Lamarr") featured in the Mel Brooks comedy Blazing Saddles infringed her right to privacy. Brooks said he was flattered; the studio settled out of court for an undisclosed nominal sum and an apology to Lamarr for "almost using her name". Brooks said that Lamarr "never got the joke". With her eyesight failing, Lamarr retreated from public life and settled in Miami Beach, Florida, in 1981.

In 1996, a large Corel-drawn image of Lamarr won the annual cover design contest for the CorelDRAW's yearly software suite. For several years, beginning in 1997, it was featured on boxes of the software suite. Lamarr sued the company for using her image without her permission. Corel countered that she did not own rights to the image. The parties reached an undisclosed settlement in 1998.

In 1997, Canadian company WiLAN signed an agreement with Lamarr to acquire 49% of the marketing rights of her patent, and a right of first refusal for the remaining 51% for ten quarterly payments. This was the only financial compensation she received for her frequency-hopping spread spectrum invention. A friendship ensued between her and the company's CEO, Hatim Zaghloul.

Lamarr became estranged from her son, James Lamarr Loder (who believed he was adopted until 2001), when he was 12 years old. Their relationship ended abruptly, and he moved in with another family. They did not speak again for almost 50 years. Lamarr left James Loder out of her will, and he sued for control of the US$3.3 million estate left by Lamarr in 2000. He eventually settled for US$50,000. James Loder was the Omaha, Nebraska police officer who was charged but then acquitted of the killing of 14 year old Vivian Strong in 1969.

In the last decades of her life, Lamarr communicated only by telephone with the outside world, even with her children and close friends. She often talked up to six or seven hours a day on the phone, but she spent hardly any time with anyone in person in her final years. A documentary film, Calling Hedy Lamarr, was released in 2004 and features her children Anthony Loder and Denise Loder-DeLuca.

Lamarr died in Casselberry, Florida, on January 19, 2000, of heart disease, aged 85. According to her wishes, she was cremated and her son Anthony Loder spread her ashes in Austria's Vienna Woods.

In 1939, Lamarr was voted the "most promising new actress" of 1938 in a poll of area voters conducted by a Philadelphia Record film critic.[95]

In 1951, British moviegoers voted Lamarr the tenth best actress of 1950,[96] for her performance in Samson and Delilah.

In 1960, Lamarr was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for her contribution to the motion picture industry, at 6247 Hollywood Blvd adjacent to Vine Street where the walk is centered.

In 1997, Lamarr and George Antheil were jointly honored with the Electronic Frontier Foundation's Pioneer Award.

Also in 1997, Lamarr was the first woman to receive the Invention Convention's BULBIE Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award, known as the "Oscars of inventing".

In 2014, Lamarr and Antheil were posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame for frequency-hopping spread spectrum technology.

Also in 2014, Lamarr was given an honorary grave in Vienna's Central Cemetery, where the remaining portion of her ashes were buried in November, shortly before her 100th birthday.

Asteroid 32730 Lamarr, discovered by Karl Reinmuth at Heidelberg Observatory in 1951, was named in her memory. The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on August 27, 2019 (M.P.C. 115894).

On 6 November 2020, a satellite named after her (ÑuSat 14 or "Hedy", COSPAR 2020-079F) was launched into space.

The 2004 documentary film Calling Hedy Lamarr features her children, Anthony Loder and Denise Loder-DeLuca.

In 2010, Lamarr was selected out of 150 IT people to be featured in a short film launched by the British Computer Society on May 20.

Also during 2010, the New York Public Library exhibit Thirty Years of Photography at the New York Public Library included a photo of a topless Lamarr (c. 1930) by Austrian-born American photographer Trude Fleischmann.

The 2017 documentary film Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story, written and directed by Alexandra Dean and produced by Susan Sarandon,[108] about Lamarr's life and career as an actress and inventor, also featuring her children Anthony and Denise, among others, premiered at the 2017 Tribeca Film Festival.[40] It was released in theaters on November 24, 2017, and aired on the PBS series American Masters in May 2018. As of April 2020, it is also available on Netflix.

During World War II, the Office of Strategic Services invented a pyrotechnic device meant to help agents operating behind enemy lines to escape if capture seemed imminent. When the pin was pulled, it made the whistle of a falling bomb followed by a loud explosion and a large cloud of smoke, enabling the agent to make his escape. It saved the life of at least one agent. The device was codenamed the Hedy Lamarr.[109]

The Mel Brooks 1974 western parody Blazing Saddles features a male villain named "Hedley Lamarr". As a running gag, various characters mistakenly refer to him as "Hedy Lamarr" prompting him to testily reply "That's Hedley."

In the 1982 off-Broadway musical Little Shop of Horrors and subsequent film adaptation (1986), Audrey II says to Seymour in the song "Feed Me" that he can get Seymour anything he wants, including "A date with Hedy Lamarr."

On the Nickelodeon show Hey Arnold!, there is a running gag in which whenever something unfortunate happens to Arnold's grandfather, Phil, he constantly states how things would have been different if he had "married Hedy Lamarr instead!". In one episode, it is revealed that he carries a photo of her in his wallet.

In the 2003 video game Half-Life 2, Dr. Kleiner's pet headcrab, Lamarr, is named after Hedy Lamarr.

In 2008, an off-Broadway play, Frequency Hopping, features the lives of Lamarr and Antheil. The play was written and staged by Elyse Singer, and the script won a prize for best new play about science and technology from STAGE.

In 2011, the story of Lamarr's frequency-hopping spread spectrum invention was explored in an episode of the Science Channel show Dark Matters: Twisted But True, a series that explores the darker side of scientific discovery and experimentation, which premiered on September 7.

Batman co-creator Bob Kane was a great movie fan and his love for film provided the impetus for several Batman characters, among them, Catwoman. Among Kane's inspiration for Catwoman were Lamarr and actress Jean Harlow. Also in 2011, Anne Hathaway revealed that she had learned that the original Catwoman was based on Lamarr, so she studied all of Lamarr's films and incorporated some of her breathing techniques into her portrayal of Catwoman in the 2012 film The Dark Knight Rises.

In 2013, her work in improving wireless security was part of the premiere episode of the Discovery Channel show How We Invented the World.

In 2015, on November 9, the 101st anniversary of Lamarr's birth, Google paid tribute to Lamarr's work in film and her contributions to scientific advancement with an animated Google Doodle.

In 2016, Lamarr was depicted in an off-Broadway play, HEDY! The Life and Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, a one-woman show written and performed by Heather Massie.

Also in 2016, the off-Broadway, one-actor show Stand Still and Look Stupid: The Life Story of Hedy Lamarr starring Emily Ebertz and written by Mike Broemmel went into production.

Also in 2016, Whitney Frost, a character in the TV show Agent Carter, was inspired by Lamarr and Lauren Bacall.

In 2017, actress Celia Massingham portrayed Lamarr on The CW television series Legends of Tomorrow in the sixth episode of the third season, titled "Helen Hunt". The episode is set in 1937 "Hollywoodland" and references Lamarr's reputation as an inventor. The episode aired on November 14, 2017.

In 2018, actress Alyssa Sutherland portrayed Lamarr on the NBC television series Timeless in the third episode of the second season, titled "Hollywoodland". The episode aired March 25, 2018.

Gal Gadot is set to portray Lamarr in an Apple TV+ limited series based on her life story.

A novelization of her life, The Only Woman in the Room by Marie Benedict, was published in 2019.

#hedy lamarr#classic hollywood#classic movie stars#golden age of hollywood#old hollywood#1930s hollywood#1940s hollywood#1950s hollywood#hollywood legend

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lucy and John Wayne

S5;E10 ~ November 21, 1966

Synopsis

Mr. Mooney asks Lucy to deliver some important contracts to the studio, where she meets John Wayne and worms her way onto the set of his latest picture. Naturally, Lucy doesn't behave and causes more trouble than a barroom brawl!

Regular Cast

Lucille Ball (Lucy Carmichael), Gale Gordon (Theodore J. Mooney), Mary Jane Croft (Mary Jane Lewis)

Guest Cast

John Wayne (Himself / “Tall”) was born Marion Morrison in 1907. He made his film debut in 1926 and rose to become an iconic presence in the Western film genre. He was nominated for three Oscars, winning in 1969 for True Grit. He epitomized rugged masculinity and was famous for his distinctive voice and walk. His nickname ‘Duke’ came from his own pet Airedale. Wayne previously worked with Lucille Ball in a 1955 episode of “I Love Lucy,” also titled “Lucy and John Wayne” (ILL S5;E2). He died in 1979 at the age of 72.

In the film he is shooting, Wayne's character is named Tall. Wayne was 6'4” and appeared in the 1944 film Tall in the Saddle.

Joseph Ruskin (Joe, the Director) appeared in four of the “Star Trek” series, the first being shot at Desilu. This is his only appearance on “The Lucy Show,” but he also does a 1968 episode of “Here's Lucy.”

Bryan O'Byrne (Bryan, the Assistant Director) was an actor and (later) acting teacher who appeared in over 200 commercials. This is his only appearance with Lucille Ball.

Morgan Woodward (“Pierce”) was seen on many TV Westerns but is perhaps best remembered as Gibbs on “The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp” (1958-61). This is his only appearance with Lucille Ball.

Joyce Perry (Joyce, Studio Receptionist) makes the second of her two appearances on the series. She was also a screen writer, receiving Emmy nominations for “Days of Our Lives” and winning a WGA (Writers Guild of America) Award in 1975 for “Search for Tomorrow.”

Milton Berle (Himself, uncredited) was born Milton Berlinger in New York City on July 12, 1908. He started performing at the age of five. He perfected his comedy in vaudeville, early silent films, and then on radio, before taking his act to the small screen, where he would be proclaimed “Mr. Television” and later “Uncle Miltie.” He hosted “Texaco Star Theater” on NBC from 1948 to 1956. The variety show was re-titled "The Milton Berle Show” in 1954 when Texaco dropped their sponsorship. The program was briefly revived in 1958, but lasted only one season. In 1959 he played himself in “Milton Berle Hides out at the Ricardos.” This is the second of his three episodes of "The Lucy Show,” the first being “Lucy Saves Milton Berle” (S4;E13). He also did two episodes of “Here’s Lucy.” On all but one, he again played himself. He died of colon cancer in 2002.

Berle makes a walk-through cameo appearance with no dialogue.

Kay Stewart (Commissary Waitress) was the subject of a feature story in the first edition of Life Magazine, which focused on the fact that she was apparently the first female cheerleader at a major university (Northwestern). This is her only appearance with Lucille Ball.

Ed Nelson (Ed Nelson, uncredited) was seen in several episodes of Desilu’s “The Untouchables”. This is his only appearance with Ball and Wayne.

Nelson is a married actor friend of Mary Jane’s. He appears wearing a Civil War uniform with an arrow through his chest and sticking out his back.

Danny Borzage (Accordionist, uncredited) appeared in 13 films with John Wayne from 1939 to 1967. He also appeared with Wayne on a 1960 episode of “Wagon Train” directed by John Ford. Both Borzage and Wayne were favorites of Ford's. This is his only appearance with Lucille Ball.

Victor Romito (“Bartender”, uncredited) makes the first of his two appearances on “The Lucy Show.” He also appeared in four episodes of “Here's Lucy.” . He was seen as an extra in the 1960 Lucille Ball / Bob Hope film Critic's Choice. That same year he was seen with John Wayne in North to Alaska, and in 1962's How the West Was Won.

Jerry Rush (Cameraman, uncredited) makes the fifth of his nine (mostly uncredited) appearances on the series. He also did two episodes of “Here’s Lucy.”

Rush can also be seen in the background having lunch in the commissary scene. He wears a white shirt over his red shirt.

Joan Carey (Script Girl, uncredited, above, lower right corner) appeared as a background performer in many episodes of “I Love Lucy” and “The Lucy Show” also serving as stand-in for Lucy and others.

The 'Barflys' (aka Stunt Men) are played by:

Jerry Gatlin was an actor and stunt man who later turns up in the Lucille Ball film Mame (1974). He appeared with John Wayne in 13 films between 1961 and 1975.

Bill Hart was an actor and stunt man who appeared in three films with John Wayne between 1960 and 1963. This is his only appearance with Lucille Ball.

Boyd 'Red' Morgan is an actor and stunt man who will also be seen in four episodes of “Here's Lucy.” He did 11 films with John Wayne between 1956 and 1970.

Chuck Roberson was an actor and stunt man who played minor roles in many films. He was a stunt double for John Wayne in more than 35 films and television shows. He played one of the firemen who rescues Lucy and Viv from their roof when “Lucy Puts Up a TV Antenna” (S1;E9), four years earlier.

In the commissary, Mr. Simon “a director” (who Lucy mistakes for Burt Lancaster), the studio doctor (who Lucy mistakes for Richard Chamberlain), an actor named Will, and more than a dozen other background players appear – all uncredited.

The episode indulges the old trope that movie actors eat lunch at the studio commissary in full costume and make-up. The commissary is named the Studio Cafe. We are reminded that Mary Jane works at the studio, although which studio is not made clear. Could it be Desilu?

Mr. Mooney dictates a letter to John Wayne about his bank's financial participation in a “film about a war wagon.” Gale Gordon emphasizes the words “war wagon” because that is the actual title of the film, which was released in May 1967. It co-starred Kirk Douglas, who made a cameo appearance in “Lucy Goes to a Hollywood Premiere” (S4;E20). It also featured Chuck Roberson and Boyd 'Red' Morgan who appear as Barflys in this episode.

Lucy mentions to Wayne that he usually stars opposite Maureen O'Hara, who also had red hair. Ball and O'Hara were both in the 1940 film Dance, Girl, Dance. Lucy also mentions that Wayne is usually directed by John Ford. Ford and Wayne collaborated on 23 films between 1928 and 1963. Ford directed Lucille Ball in the 1935 film The Whole Town's Talking.

Fawning over John Wayne, Lucy mentions his recently released films Cast a Giant Shadow (March 1966), In Harms Way (1965), and the Oscar-nominated The Sands of Iwo Jima (1949).

Lucy says that Wayne has played characters who've served in every branch of the service and that Bob Hope should play a Christmas show just for him! Lucy's film co-star and friend Bob Hope was known for performing in USO shows overseas during the holidays to entertain the American troops. Hope had a cameo in “Lucy and the Plumber” (S3;E2).

In the saloon scene, the accordionist plays “Golden Slippers,” a song penned by James A. Bland in 1879. It was famously used in the 1948 John Ford film Fort Apache starring John Wayne.

In the Studio Cafe, Lucy mistakes a man named Mr. Simon for Burt Lancaster. They both are roughly the same build. She then mistakes the studio doctor for Richard Chamberlain, a joke referring to Chamberlain's most popular role as “Dr. Kildare” (1961-66) which ended its run on NBC a few months earlier. She then mistakes Milton Berle for the janitor. Berle is oddly dressed in an ill-fitting suit, a straw hat, and has a blacked-out tooth. He has a bewildered expression on his face, as if he's still in character for a hillbilly movie. It is unclear how Lucy might mistake him for a studio janitor.

Coincidentally, “The Lucy Show” stunt coordinator was named Jesse Wayne (no relation).

Callbacks!

John Wayne previously guest-starred as himself on "I Love Lucy" in 1955. The episode was also titled "Lucy and John Wayne” (ILL S5;E2).

Hanging on the wall in the studio commissary is a black and white headshot of Bob Crane from “Hogan's Heroes” (1964-71), a TV show filmed at Desilu. Crane played himself in a parody of “Hogan's Heroes” in “Lucy and Bob Crane” (S4;E22).

Lucy Carmichael was previously on the film set of a movie western when she assumed the identity of Iron Man Carmichael in “Lucy the Stunt Man” (S4;E5). Curiously, while Lucy Carmichael is telling the director how to shoot the picture, she doesn't mention her experience as Iron Man. In 1954, Lucy Ricardo made her own western movie in her apartment in “Home Movies” (ILL S3;E20).

Blooper Alerts!

Who Am I? Lucy reveals that her maiden name is MacGillicuddy, same as Lucy Ricardo. At “Lucy's College Reunion” (S2;E11), Lucy Carmichael said her maiden name was Taylor. This is the second week in a row that the Lucy character has “forgotten” key information about her past. In the previous week's “Lucy Gets Caught Up in the Draft” (S5;E9) she said her son's name was 'Jimmy' when in fact it was 'Jerry.' Geoffrey Mark Fidelman’s The Lucy Book, says that although the production staff told Lucille Ball of her error, she insisted that she was right and would not change the reference. Perhaps this inconsistency about her birth name is also attributable to the staff's deference to Ball's faulty memory?

Sitcom Logic Alert! When Lucy sees Milton Berle in the commissary she says “Wait'll I tell the girls I nearly saw Milton Berle!” This line sounds very much like Lucy Ricardo speaking, not Lucy Carmichael. Lucy Carmichael has already met TV star Milton Berle in “Lucy Saves Milton Berle” (S4;E13). Here, he looks directly at Lucy and Mary Jane but does not acknowledge them despite the chaos they previously brought to his life. Also, it is unclear which “girls” Lucy is talking about since Mary Jane seems to be her only female friend. Perhaps she is referring to the unseen secretarial pool at the bank? Lucy Ricardo, however, would have bragged to all the “girls” of the Wednesday Afternoon Fine Arts League!

Lucy the Director! When the Assistant Director calls the scene to be slated, he cups his hand over his mouth and purposely garbles the title of the film. This was a tactic Lucy Ricardo used many times on “I Love Lucy” when she wanted to be purposely vague about important details like her age. Later, when the Assistant Director shouts “Scene 856, Take One!” Lucy corrects him under hear breath: “Take Four!” Lucy is right, but it is hard to determine if this was Lucy Carmichael or Lucille Ball talking! This scene, with Lucy Carmichael standing behind the camera and correcting the crew, probably mirrored Ball's own interactions with her “Lucy Show” staff.

On a purely technical note, it is unlikely that any film would have 856 scenes!

“Lucy and John Wayne” rates 2 Paper Hearts out of 5

#The Lucy Show#Lucy and John Wayne#Lucille Ball#John Wayne#Gale Gordon#Mary Jane Croft#Milton Berle#Joseph Ruskin#Bryan O'Byrne#Kay Stewart#Joyce Perry#Danny Borzage#Victor Romito#Jerry Rush#Jerry Gatlin#Bill Hart#Red Morgan#Chuck Roberson#The War Wagon#Maureen O'Hara#John Ford#Cast a Giant Shadow#In Harm's Way#The Sands of Iwo Jima#Bob Hope#Golden Slippers#Burt Lancaster#Richard Chamberlain#Bob Crane#The Lucy Book

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Academy Awards through the years: PT. 1

By Los Angeles Times Staff

Feb. 26th, 2017

The first ceremony made the Los Angeles Times’ front page under the headline “Film-Merit Trophies Awarded.” Coverage was all of one photograph and two paragraphs. Since then, the Academy Awards have become an event watched around the world. Scroll down for a year-by-year look at the Oscars.

May 16, 1929. The first Academy Awards at the Hollywood Roosevelt's Blossom Room (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

Before a large gathering of motion-picture celebrities and other notables, the first Academy Awards ceremony is held at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel. Academy President Douglas Fairbanks handed out 15 statuettes for outstanding achievement in 1927 and 1928.

Best picture: “Wings”

Actor: Emil Jannings, “The Last Command” and “The Way of all Flesh”

Actress: Janet Gaynor, “Seventh Heaven,” “Street Angel” and “Sunrise”

Director: Frank Borzage, “Seventh Heaven”

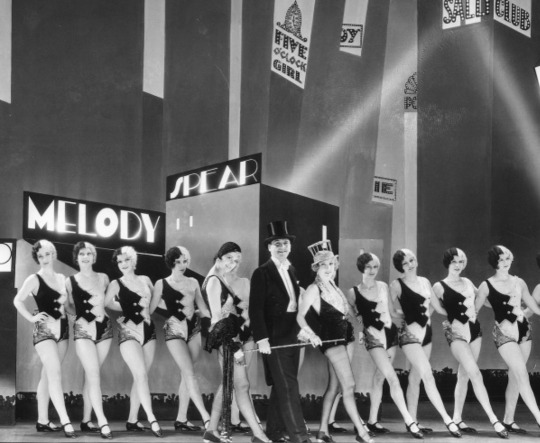

April 3, 1930. "Broadway Melody" was released in 1929 and took top honors at the Academy Awards the next year. (MGM)

The Academy Awards are announced during a banquet attended by 300 academy members and their guests at the Ambassador Hotel. Academy President William C. deMille presents seven gold statuettes.

Best picture: “The Broadway Melody”

Actor: Warner Baxter, “In Old Arizona”

Actress: Mary Pickford, “Coquette”

Director: Frank Lloyd, “The Divine Lady”

Nov. 5, 1930. Norma Shearer with her statuette for "The Divorcee." (Associated Press)

Conrad Nagel, vice president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, presents the statuettes at the third awards ceremony. The 600 attendees watch “Artistic and Otherwise,” a “sound recording film” by Thomas A. Edison on the industry’s progress in the last decade.

Best picture: “All Quiet on the Western Front”

Actor: George Arliss, “Disraeli”

Actress: Norma Shearer, “The Divorcee”

Director: Lewis Milestone, “All Quiet on the Western Front”

Nov. 10, 1931. Marie Dressler and Lionel Barrymore after their wins. (Associated Press)

The notables of Filmland gather at the Biltmore Hotel for the annual banquet. U.S. Vice President Charles Curtis tells the 2,000 gathered: “To my mind, the motion-picture industry is one of man’s greatest benefactors — it is great in size, in reputation and in worth.”

Best picture: “Cimarron”

Actor: Lionel Barrymore, “Free Soul”

Actress: Marie Dressler, “Min and Bill”

Director: Norman Taurog, “Skippy”

Nov. 18, 1932. Wallace Beery, left, and Jackie Cooper starred in "The Champ." (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

Lionel Barrymore is the toastmaster at the annual awards banquet at the Ambassador Hotel. Walt Disney is given a special award for his series of Mickey Mouse cartoons. As the ballots are turned in they are dropped into a special machine and tabulated “in full view of the assembled guests.”

Best picture: “Grand Hotel”

Actor: Fredric March, “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” and Wallace Beery, “The Champ”

Actress: Helen Hayes, “The Sin of Madelon Claudet”

Director: Frank Borzage, “Bad Girl”

March 16, 1934. Douglas Fairbanks Jr. with Katharine Hepburn in a scene from "Morning Glory" (Associated Press)

Katharine Hepburn, still a newcomer to Hollywood, wins her first Academy Award for her work in “Morning Glory.” “Little Women,” in which she also stars, finishes third in the race for best production behind “A Farewell to Arms” and the winner, a film adaptation of playwright Noel Coward’s “Calvacade.”

Best picture: “Cavalcade”

Actor: Charles Laughton, “The Private Life of Henry VIII”

Actress: Katharine Hepburn, “Morning Glory”

Director: Frank Lloyd, “Cavalcade”

Feb. 27, 1935. Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert in "It Happened One Night." (Columbia Pictures)

The humorist Irvin S. Cobb presents the gold statuettes at the Biltmore Hotel. In “a radical departure from all previous elections,” the balloting is done in the open and write-ins are allowed. Although she doesn’t win, Bette Davis receives the most write-in votes for her work in “Of Human Bondage.”

Best picture: “It Happened One Night”

Actor: Clark Gable, “It Happened One Night”

Actress: Claudette Colbert, “It Happened One Night”

Director: Frank Capra, “It Happened One Night”

*Courtesy of Los Angeles Times.

#academy awards#old academy awards#vintage academy awards#old hollywood stars#old movies#old films#old hollywood#old cinema#vintagewomen#vintagephotos#vintagefashion#vintage hollywood#vintage films#vintage cinema#early academy awards#1920s#1920s hollywood#1920sfashion#1920s film#1920s history#1930smovies#1930sfashion#1930s hollywood#1930s#1930s cinema#1930s photography#los angeles times#clark gable#film-merit trophies awarded#hollywood roosevelt hotel

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Street Angel (Frank Borzage, 1928)

El breve ciclo «Clásicos del cine mudo» (que nos ha devuelto, por un par de meses, a los tiempos en que el programa de U.H.F. «Sombras recobradas» permitía ver un film mudo a la semana) ha supuesto para mí varias revelaciones: What Price Glory (El precio de la gloria, 1926) de Walsh, Four sons (1928) de Ford, The Iron Mask (La máscara de hierro, 1929) de Dwan y, sobre todo, Street Angel (El ángel de la calle, 1928) de Borzage, cineasta al que se rescatará del olvido tan rápidamente como a Sirk en cuanto sea más conocido y exista sobre su obra un trabajo crítico menos fragmentario e ignorado que hasta ahora, ya que —por lo que he podido ver— se trata de uno de los máximos creadores de melodramas —y, por tanto, de comedias— tanto del mudo como del sonoro.

Street Angel es, de las películas suyas que conozco, quizá la mejor; tan emocionante y perfecta como Disputed Passage (Vidas heroicas, 1939), History is Made at Night (Cena a medianoche, 1937) y 7th Heaven (El séptimo cielo, 1927), es la que de modo más completo y coherente refleja la visión del mundo (ingenua, melodramática, inocente) y las creencias (de un misticismo casi surrealista) de su autor, y tiene, además, esa precaria e irrepetible magia (armonía y fluidez insuperables) que caracteriza a las postreras obras maestras del cine mudo, realizadas cuando sus días estaban contados, cuando su progreso se había visto bruscamente interrumpido por la llegada triunfal del sonoro; se diría que los grandes cineastas «mudos» quisieron despedirse en beauté de un arte condenado a desaparecer, pues de otro modo no es fácil explicarse ese glorioso «canto del cine» que representan las mejores películas mudas de los años 1927-1931: Murnau (quizá el más grande) con Sunrise y Tabu, Lubitsch con The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg, Stroheim con The Wedding March y Oueen Kelly, King Vidor con The Crowd, Borzage con 7th heaven y Street Angel, Sternberg con Underworld, The Docks of New York y The Last Command, Boris Barnet con Dievushka s korobkoi, Eisenstein con Oktiábr, Keaton con The Cameraman y Steamboat Bill, Jr., Chaplin con The Circus y City Lights, Sjöström con The Wind, Hitchcock con The Farmer's Wife y The Manxman, Ford con Four sons, Dwan con The Iron Mask, Renoir con Tire-au-flanc, Dovjenko con Arsienal y Ziemlia, el rezagado Ozu con Tokyo no gassho y (ya en 1932) con Umarete wa mita keredo, Pabst con Der Liebe der Jeanne Ney... ya sólo menciono lo más impresionante de lo que he visto, omitiendo Frau im Mond de Lang, Downhill y The Ring de Hitchcock, Love de Goulding, A Woman of Affairs de Brown, Das Tagebuch einer Verlorenen de Pabst, Show People de Vidor y otras varias excelentes.

Como Four Sons y, en general, todo el cine americano posterior a Sunrise, especialmente el producido por la Fox, Street Angel comparte con 7th Heaven (además de su admirable pareja protagonista, Janet Gaynor y Charles Farrell) una notable influencia del estilo «kammerpsiel» importado por Murnau: planos muy largos, con travellings y panorámicas sinuosos y veloces, a menudo de ida y vuelta; uso de luz, sombras, brumas, humo, ciertos escenarios privilegiados (bosques, lagos, ríos, calles, rellanos de escaleras, escalinatas, iglesias, ferias, estudios de pintores, o fotógrafos con grandes cristaleras y con vistas a los tejados, etc.); una curiosa tendencia a que tanto los movimientos de la cámara como los de los actores sean circulares o al menos curvilíneos; la mezcla de dramatismo predestinado y comedia; la sensación de suave y vertiginosa continuidad que transmiten los movimientos de cámara y el montaje; la delicada sutileza de la dirección de actores, que reenlaza con la etapa de máxima estilización de las más impresionantes y luminosas secuencias de exteriores. Sin embargo, una vez reconocida la decisiva aportación de Murnau, sería injusto no reconocer que, al igual que Four Sons es ya una película totalmente «fordiana» —casi tanto como, por ejemplo, How Green Was My Valley (¡Qué verde era mi valle!, 1941)—, lo más memorable de Street Angel es plena y exclusivamente «borzagiano». No es fácil, por desgracia, trasmitir con palabras, ni siquiera «contándola» y «describiéndola», la sublime poesía de Street Angel, su encanto, su poder de fascinación visual y dramática, su conmovedora ingenuidad, su patetismo, su ternura, su emoción, ya que todas estas características deben muy poco a la peripecia argumental (descaradamente melodramática, llena de inverosímiles coincidencias, totalmente ajena al realismo) y todo, o casi, a la tonalidad luminosa de cada escena, a los gestos y las miradas de los actores e incluso, en ocasiones, al ritmo mismo de la película. Y es que pocos cineastas han sabido filmar el amor como Borzage (tal vez sólo Griffith, Murnau, Ray y McCarey), y menos todavía han sido capaces de pintar como él la felicidad en la pobreza o la huida (sólo Nicholas Ray o el Fritz Lang de You Only Live Once), o una dicha tan intensa que se presiente con angustia y congoja que no puede durar (quizá el Sirk de A Time to Love and a Time to Die y, de nuevo, Murnau, Ray y McCarey, a veces Griffith, Chaplin, Capra, Renoir en Une partie de campagne, Dreyer en Vedrens Dag), cuando son precisamente el amor, la dicha, la adversidad y el infortunio los motores básicos, con el azar y el destino, del mundo onírico de Borzage.

Es posible que a muchos las películas de Borzage les hagan reír de la peor manera que cabe (lo que los franceses llaman ricaner), burlonamente, con desprecio, pero Borzage podría decir, como un gran personaje de Leo McCarey, «beauty makes me cry» («la belleza me hace llorar»), y no tenía el menor reparo en tomarse muy en serio las desventuras, los sueños, los desvelos o los deseos de sus personajes, por los que sentía tanto cariño como respeto: por eso su cine, generoso y sensible, romántico e inconformista, desesperado pero invicto, delicado pero no blando, sino peleón y obstinado, late todavía y es capaz de hacer vibrar, mientras que las películas de hace dos años (o menos) de los más celebrados ricaneurs apenas logran despertar el recuerdo de las risotadas que tan rastreramente pudieran provocar.

Borzage fue uno de los máximos exponentes de una ilustre tradición, fundada por Griffith y Chaplin, refinada por Murnau, a la que Stroheim, Lubitsch y Sternberg afluyeron ocasionalmente, que Ford, McCarey, Capra y quizá La Cava prolongaron y que tiene hoy en Billy Wilder —The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, (1970) y Avanti! (1972)— un último y tal vez inesperado heredero. Esta tradición —que tiene tanto de moral como de estética— procede, muy claramente, del cine mudo, pues se basa, fundamentalmente, en la belleza del gesto y de los sentimientos, y cristaliza en la ambición de fundir en los personajes y los espectadores, simultáneamente, la esbozada sonrisa, el nudo en la garganta y las contenidas lágrimas; no pide más (ni recurre para lograrlo a cualquier medio), pero no se contenta con menos: escenas como muchas de los mejores Griffith —Broken Blossoms (1919), Isn't Life Wonderful (1924), The Struggle (1931)—, las despedidas de los ancianos esposos de Make Way for Tomorrow (1937) y el de Bing Crosby e Ingrid Bergman en The Bells of St. Mary's (1945) o el reencuentro de Cary Grant y Deborah Kerr en An Affair to Remember (1957) de McCarey, la escena de Charlie y la ciega a través del escaparate de la floristería en City Lights (1931), las de Clavero y Claire Bloom en Limelight (1952), los desesperados gestos de coqueta —patéticos por su evidente e indisimulable inocencia— de Janet Gaynor al inicio de Street Angel, o su larga cena de despedida —él cree que de celebración— con Charles Farrell, son algunos ejemplos de la altura a que estos cineastas supieron llegar y a la que —desde que Chaplin pusiese glorioso fin a su carrera con A Countess from Hong Kong (1966)— sólo Billy Wilder logra aproximarse.

Miguel Marías

Revista “Dirigido por” nº73, mayo-1980

1 note

·

View note

Note

what are your favorite movies? I love your blog

Zerkalo, Stalker, Andrei Rublev, Nostalgia, Solaris, Sansho the Bailiff, Osaka Elegy, The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums, When A Woman Ascends The Stairs, Le Notti di Cabiria, Sans Soleil, The Red Shoes, The Third Man, 8½, Late Spring, Floating Weeds, High And Low, The Bad Sleep Well, Le Plaisir, Autumn Sonata, Winter Light, The Virgin Spring, Cries and Whispers, Hour of the Wolf, Au Hasard Balthazar, Les cousins, Le feu follet, Vivre sa vie, Yi yi, A Time To Live/A Time to Die, The Last Year at Marienbad, Les statues meurent aussi, The Fallen Idol, L'Atalante, Woman in the Dunes, Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach, All About Eve, Dark Victory, Greed, Napoléon vu par Abel Gance, The Face of Another, Babette’s Feast, Journal d'un curé de campagne, Ordet, Vampyr, Gertrud, Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, Werckmeister Harmonies, The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, Broken Blossoms, Diary of a Lost Girl, The Heiress, Ascenceur pour L'Echafaud, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, The Promised Country, La Rayon Vert, Opening Night, Faces, Love Streams, Harakiri, Léon Morin, prêtre, Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne, Orphée, Le testament d'Orphée, La Belle Noiseuse, Dr. Mabuse, der spieler, The Human Condition (I, II, III), 24 Frames, Letter from an Unknown Woman, Till We Meet Again (Borzage), Rebecca, La Notte, Jules et Jim, Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks, Ikiru, Akahige, Ivan Grozny (I, II), Un condamné a mort s'est échappé, The Trial, F for Fake, Trois couleurs: Bleu, Trois couleurs: Rouge, The Wind, Bob Le Flambeur, La peau douce, L'Histoire d'Adele H., La Grande Illusion, La maman et la putain, I Know Where I’m Going!, Faust (Murnau), Medea, Mamma Roma, The House is Black, The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, Sonatine, The Ballad of Narayama, Roma città aperta, Voyage to Italy, The Roaring Twenties, Baby Face, Design for Living, Vivre sa Vie, Brief Encounter, The Circus, City Lights, The Night of the Hunter, Monsieur Verdoux, Terje Vigen, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, From Morn to Midnight, The Lady Vanishes, Kuroneko, Play Time, Le Quai des Brumes, Apur Sansar, The Music Room, In the Mood for Love, Taste of Cherry, Through the Olive Trees, Viridiana, Tale of Tales, To Be Or Not To Be, Sherlock Jr., Our Hospitality, The General, The Apartment, Pandora’s Box, Veronika Voss, Morocco, L'Age d'Or, The Passion of Joan of Arc, Laura, Where The Sidewalk Ends, Notorious, The 39 Steps, The Big Sleep, In A Lonely Place, Easy Living, The Thin Man, The Shop Around The Corner, Knight Without Armour, As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty, Steamboat Bill Jr., Floating Clouds, Umberto D., Throne of Blood, Yojimbo, The Big Heat, Chronicle of a Summer, A Streetcar Named Desire, The Lost Weekend, La Ronde, Der amerikanische Freund, The Smiling Lieutenant, The Uninvited, Wings (Shepitko), The Ascent, Come and See, Liebelei, Ran, Le Fantôme de la liberté, The Color of Pomegranates, Les Vampires, Dr. Strangelove, Certified Copy, The Nibelung: Siegfried, Shadows of our Forgotten Ancestors, Devi, The Phantom Carriage, Russian Ark, and many, many others.

514 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Best movies -> 1940 - 1949

1. The Third Man - Carol Reed [1949] UK

2. Spellbound - Alfred Hitchcock [1945] USA

3. Ladri di biciclette - Vittorio De Sica [1948] Italy

4. The Red Shoes - Michael Powell, Emeric Pressburger [1948] UK

5. Casablanca - Michael Curtiz [1942] USA

6. Brief Encounter - David Lean [1945] UK

7. Vredens dag - Carl Theodor Dreyer [1943] Denmark

8. The Lady From Shanghai - Orson Welles [1947] USA

9. Out of the past - Jacques Tourneur [1947] USA

10. The Great Dictator - Charles Chaplin [1940] USA

11. Sotto il sole di Roma - Renato Castellani [1948] Italy

12. The Shop Around The Corner - Ernst Lubitsch [1940] USA

13. Hangmen Also Die! - Fritz Lang [1943] USA

14. The Killers - Robert Siodmak [1946] USA

15. Roma, città aperta - Roberto Rossellini [1945] Italy

16. Pursued - Raoul Walsh [1947] USA

17. The Best Years of Our Lives - William Wyler [1946] USA

18. Double Indemnity - Billy Wilder [1944] USA

19. The Ox-Bow Incident - William A. Wellman [1942] USA

20. The Treasure of Sierra Madre - John Huston [1948] USA

21. The Big Sleep - Howard Hawks [1946] USA

22. It’s a Wonderful Life - Frank Capra [1946] USA

23. 野良犬 - Akira Kurosawa [1949] Japan

24. Letter from an Unknown Woman - Max Öphuls [1948] USA

25. Portrait of Jennie - William Dieterle [1948] USA

26. A Letter to Three Wives - Joseph L. Mankiewicz [1949] USA

27. 晩春 - Yasujirō Ozu [1949] Japan

28. Fantasia - James Algar, Samuel Armstrong, Ford Beebe Jr., Norman Ferguson, Jim Handley, T. Hee, Wilfred Jackson, Hamilton Luske, Bill Roberts, Paul Satterfield, Ben Sharpsteen [1940] USA

29. La torre de los siete jorobados - Edgar Neville [1944] Spain

30. I've Always Loved You - Frank Borzage [1946] USA

Letterboxd profile

Perfil en Filmaffinity

0 notes

Link