#bight of biafra

Text

Afro-Jamaicans are Jamaicans of predominant African descent. They represent the largest ethnic group in the country.

The ethnogenesis of the African Jamaican people stemmed from the Atlantic slave trade of the 16th century, when enslaved Africans were transported as slaves to Jamaica and other parts of the Americas. During the period of British rule, slaves brought into Jamaica were primarily Akan, some of whom ran away and joined with Maroons and even took over as leaders

West Africans were enslaved in wars with other West African states and kidnapped by either African or European slavers. The most common means of enslaving an African was through abduction.

Based on slave ship records, enslaved Africans mostly came from the Akan people (notably those of the Asante Kotoko alliance of the 1720's: Asante, Bono, Wassa, Nzema and Ahanta) followed by Kongo people, Fon people, Ewe people, and to a lesser degree: Yoruba, Ibibio people and Igbo people. Akan (then called Coromantee) culture was the dominant African culture in Jamaica.

Originally in earlier British colonization, the island before the 1750s was in fact mainly Akan imported. However, between 1663 and 1700, only six per cent of slave ships to Jamaica listed their origin as the Gold Coast, while between 1700 and 1720 that figure went up to 27 per cent. The number of Akan slaves arriving in Jamaica from Kormantin ports only increased in the early 18th century. But due to frequent rebellions from the then known "Coromantee" that often joined the slave rebellion group known as the Jamaican Maroons, other groups were sent to Jamaica. The Akan population was still maintained, since they were the preference of British planters in Jamaica because they were "better workers", according to these planters. According to the Slave Voyages Archives, though the Igbo had the highest importation numbers, they were only imported to Montego Bay and St. Ann's Bay ports, while the Akan (mainly Gold Coast) were more dispersed across the island and were a majority imported to seven of 14 of the island's ports (each parish has one port).

Myal and Revival

Kumfu (from the word Akom the name of the Akan spiritual system) was documented as Myal and originally only found in books, while the term Kumfu is still used by Jamaican Maroons. The priest of Kumfu was called a Kumfu-man. In 18th-century Jamaica, only Akan gods were worshipped by Akan as well as by other enslaved Africans. The Akan god of creation, Nyankopong was given praise but not worshipped directly. They poured libation to Asase Ya, the goddess of the earth. But nowadays they are only observed by the Maroons who preserved a lot of the culture of 1700s Jamaica.

"Myal" or Kumfu evolved into Revival, a syncretic Christian sect. Kumfu followers gravitated to the American Revival of 1800 Seventh Day Adventist movement because it observed Saturday as god's day of rest. This was a shared aboriginal belief of the Akan people as this too was the day that the Akan god, Nyame, rested after creating the earth. Jamaicans that were aware of their Ashanti past while wanting to keep hidden, mixed their Kumfu spirituality with the American Adventists to create Jamaican Revival in 1860. Revival has two sects: 60 order (or Zion Revival, the order of the heavens) and 61 order (or Pocomania, the order of the earth). 60 order worships God and spirits of air or the heavens on a Saturday and considers itself to be the more "clean" sect. 61 order more deals with spirits of the earth. This division of Kumfu clearly shows the dichotomy of Nyame and Asase Yaa's relationship, Nyame representing air and has his 60 order'; Asase Yaa having her 61 order of the earth. Also the Ashanti funerary/war colours: red and black have the same meaning in Revival of vengeance. Other Ashanti elements include the use of swords and rings as means to guard the spirit from spiritual attack. The Asantehene, like the Mother Woman of Revival, has special two swords used to protect himself from witchcraft called an Akrafena or soul sword and a Bosomfena or spirit sword

Jamaican Patois, known locally as Patwa, is an English creole language spoken primarily in Jamaica and the Jamaican diaspora. It is not to be confused with Jamaican English nor with the Rastafarian use of English. The language developed in the 17th century, when enslaved peoples from West and Central Africa blended their dialect and terms with the learned vernacular and dialectal forms of English spoken: British Englishes (including significant exposure to Scottish English) and Hiberno English. Jamaican Patwa is a post-creole speech continuum (a linguistic continuum) meaning that the variety of the language closest to the lexifier language (the acrolect) cannot be distinguished systematically from intermediate varieties (collectively referred to as the mesolect) nor even from the most divergent rural varieties (collectively referred to as the basilect). Jamaicans themselves usually refer to their use of English as patwa, a term without a precise linguistic definition.

Jamaican Patois contains many loanwords of African origin, a majority of those etymologically from Gold Coast region (particularly of the Asante-Twi dialect of the Akan language of Ghana).

Most Jamaican proverbs are of Asante people, while some included other African proverbs

Jamaican mtDNA

A DNA test study submitted to BMC Medicine in 2012 states that "....despite the historical evidence that an overwhelming majority of slaves were sent from the Bight of Biafra and West-central Africa near the end of the British slave trade, the mtDNA haplogroup profile of modern Jamaicans show a greater affinity with groups found in the present-day Gold Coast region Ghana....this is because Africans arriving from the Gold Coast may have thus found the acclimatization and acculturation process less stressful because of cultural and linguistic commonalities, leading ultimately to a greater chance of survivorship and a greater number of progeny."

More detailed results stated: "Using haplogroup distributions to calculate parental population contribution, the largest admixture coefficient was associated with the Gold Coast(0.477 ± 0.12 or 59.7% of the Jamaican population with a 2.7 chance of Pygmy and Sahelian mixture), suggesting that the people from this region may have been consistently prolific throughout the slave era on Jamaica. The diminutive admixture coefficients associated with the Bight of Biafra and West-central Africa (0.064 ± 0.05 and 0.089 ± 0.05, respectively) is striking considering the massive influx of individuals from these areas in the waning years of the British Slave trade. When excluding the pygmy groups, the contribution from the Bight of Biafra and West-central rise to their highest levels (0.095 ± 0.08 and 0.109 ± 0.06, respectively), though still far from a major contribution. When admixture coefficients were calculated by assessing shared haplotypes, the Gold Coast also had the largest contribution, though much less striking at 0.196, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.189 to 0.203. When haplotypes are allowed to differ by one base pair, the Jamaican matriline shows the greatest affinity with the Bight of Benin, though both Bight of Biafra and West-central Africa remain underrepresented. The results of the admixture analysis suggest the mtDNA haplogroup profile distribution of Jamaica more closely resembles that of aggregated populations from the modern-day Gold Coast region despite an increasing influx of individuals from both the Bight of Biafra and West-central Africa during the final years of trading enslaved Africans.

The aforementioned results apply to subjects whom have been tested. Results also stated that African Jamaicans (that make up more than 90% of the population) on an average have 97.5% of African MtDNA and very little European or Asian ancestry could be found. Both ethnic and racial genetic results are based on a low sample of 390 Jamaican persons and limited regional representation within Jamaica. As Afro-Jamaicans are not genetically homogeneous, the results for other subjects may yield different results.

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brownskin#brown skin#afrakans#african culture#afrakan spirituality#asante#jamaican#benin#bight of biafra#gold coast#mtdna#afro jamaicans#twi#west africa#africa#algeria#uganda#ethiopia#ghana#myal#rastafari#rasta#rastaman#rasta love#kisumi amau#tegan and sara

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐈𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐚𝐜𝐭 𝐚𝐛𝐨𝐮𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐈𝐠𝐛𝐨𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐍𝐢𝐠𝐞𝐫𝐢𝐚 🇳🇬

Did you know that the Igbos were previously referred to as “red eboes“ in the 15th and 18th centuries? This was due to their distinctive light skin complexion. Originating primarily from what was known as the Bight of Biafra on the West African coast, Igbo people were taken in relatively high numbers to Jamaica as a result of the Transatlantic Släve Trade, beginning around 1750AD. Due to their predominance in Jamaica, they were referred to as red Eboes or simply Eboe. Today “Eboe” in Jamaica means red or someone with light skin as a result of this. There is a town in Belize named Eboe town due to the high presence of Igbos.

#blacktumblr#black history#black liberation#african history#igbo#nigeria#west africa#africa#jamaica#belize

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

MON 29th JAN: Benin 'Bronzes'

Masterlist

BUY ME A COFFEE

Further reading: Annie E. Coombes, Reinventing Africa: Museums, Material Culture and Popular Imagination in Late Victorian and Edwardian England, ‘Material Culture at the Crossroads of Knowledge: The Case of the Benin “Bronzes”, 1994

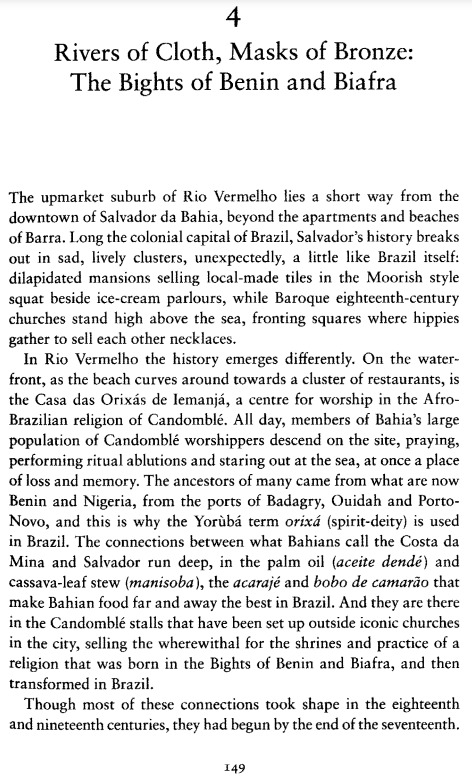

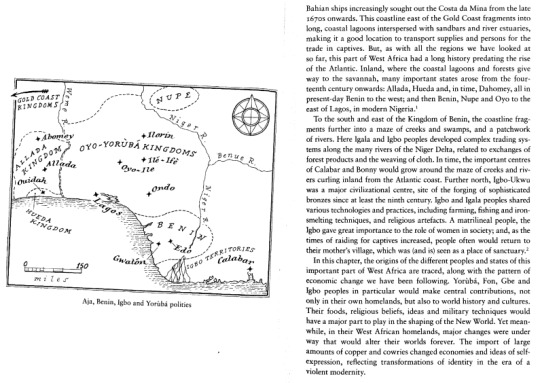

Toby Green, A Fistful of Shells: West Africa from the Rise of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution, ‘Rivers of Cloth, Masks of Bronze: The Bights of Benin and Biafra’, 2019

More and Other

Building off artwork from around the world, art of Africa is rarely explored. Or when it is, it is mislabelled as being art when its purpose was something completely different. Or served as both.

The second part of our lesson consisted of looking at Benin Bronzes and going to The British Museum to look at them in person before the lesson. Now while it was beneficial to see them up close, it was hard to find and understand what you were looking at, especially without a reference point to the history.

These are examples of the Benin Bronzes:

Resources linked to a 2019 exhibition about trans Saharan trade.

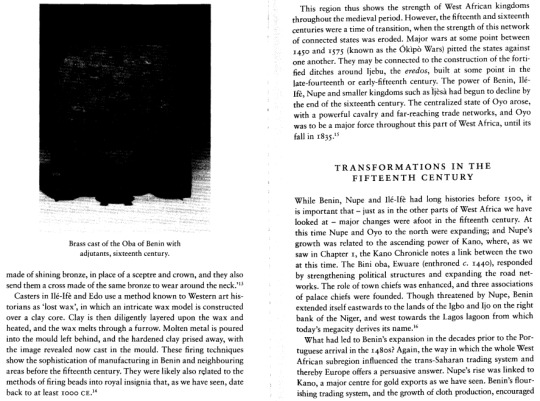

Looking closely at this piece specifically reveals hidden information to us about the Benin Bronzes, especially what they were used for and part of decoration on columns and panelling on roof. Historians love pictures in pictures as it reveals greater insight into purpose and time period.

A big question that comes up when discussing them is: Should they be returned?

Another question that comes from looking at them, and after tackling the previous question asked is: How do we reconstruct it? Is there a way to?

Bronze is a high statues object and material; these Bronzes were taken from a palace.

A comparison visually has been made to Ancient Egyptian art but there aren’t a lot of compelling references and links. Although there are records of artists travelling between these countries. How do we compare different cultural and societal developments?

These Bronzes cannot be admired without discussing the deep-rooted colonial history that became part of them due to colonisation by the British Forces, and while this is a great point and history to them, the museum does a lot to make the Bronzes about the West and colonisation, rather than giving great details about the Bronzes and their purpose, and functionality etc.

While this may not be surprising to those more educated on the topic of colonisation/colonial power, an aspect that may terrify and surprise you, that our professor said he had an unfortunate encounter with a curator of the British Museum in the late 70’s saying proudly that “nothing that was in the Museum was stolen or acquired illegally due to those countries belonging to Britain”.

While this may have some merit, only in the fact that legality is flexible historically, when tackling historical artifacts. Which makes acquisition and keeping them complicated.

And while the British Museum has people advocating for it, that it’s educational…Well, I just wonder what the countries their stolen goods and artifacts come from have to study from and display for education or other.

A book on the topic of Museum perpetuating certain ideas and views: The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution, 2020 by Dan Hicks (an anthropologist)

Art History stands in a strange place when it comes to non-European art, as it is studied by Anthropologists and Ethnologists rather than Historians or even Art Historians.

Who are the artists we collect? And what do those artists represent and how do we perpetuate it?

While Anthropology museums can argue that they appreciate the culture and house it, it’s hard to defend a place like The British Museum (which I’m very much not going to do). I am an immigrant to England and we actually refer to The British Museum as the “Museum of stolen goods”, or “The British Empire Museum”.

"A photograph in an album in the National Army Museum, perhaps taken at Portsmouth or in London shortly after the return of some of the Benin soldiers, shows 45 soldiers and officers in blackface. They have raffia capes, wigs, clubs, staffs, spears, bows and arrows and drums, and one holds a skull aloft on a stick. In the foreground, the group look on while one of the ceremonial swords looted from Benin City is held to the back of the neck of a kneeling man, in a parody of human sacrifice. […] Benin was presented as ‘degenerate’.” (Hicks, 192)

Film theorist Bill Nichols argues that re-enactment ‘forfeits its indexical bond to the original event. It draws its fantasmatic power from this very fact’ (74). For Nichols, the re-enactment gains in force because of this lost bond. The ‘very act of retrieval’ does not retrieve the original event itself but rather ‘generates a new object’ (74). Nichols, Bill. ‘Documentary Reenactment and the Fantasmatic Subject’. Critical Inquiry, vol. 35, no. 1, 2008, pp. 72-89.

What might be the new object generated by this re-enactment in 1897? Perhaps some form of rebirth or rediscovery?

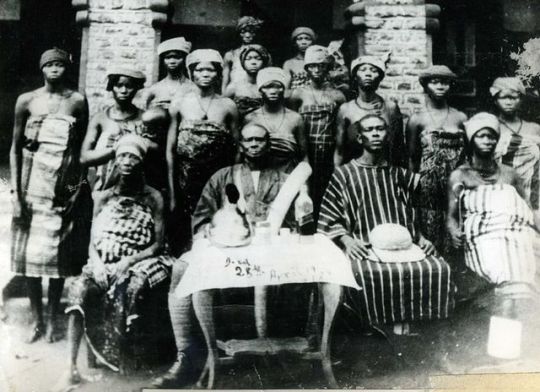

"Immediately after Benin forces ambushed and killed the Acting Consul-General Phillips and most of his entourage, the Illustrated London News of the 23 January 1897 published an article denouncing Benin society as having 'a native population ofgrovelling superstition and ignorance', together with an apparently unrelated photograph entitled 'A Native Chief and His Followers', showing a group of women sitting around the single figure of a man (fig. 3). The group of figures seem, from a contemporary European perspective, to be impassive and static. In the foreground, two women are literally arranged to frame the image. While the 'native chief' is the central figure compositionally, it is the women who predominate and who arrest the eye. The nudity of the foreground women is both masked and accentuated, because their objectification is reinforced by the fact that this is clearly not a natural posture. They have evidently been 'put' there. To cement this objectification, their bodies signify as the human equivalent of the 'trophy' display which was so popular at this time with both ethnographer and big-game hunter alike (fig. 4). This is a recurrent feature of representations, not only of the Edo but other African women, in the British illustrated press.” (Coombes, 12)

5.’Benin girls with aprons of Bells’, Rehquary, vol. VI (October 1900)

“a photograph in the Reliquary, a serious antiquarian publication with a readership of archaeologists, ethnographers and folklorists, employed the same motif ostensibly to illustrate bells on Benin women's girdles. The bells seem a rather precarious alibi for voyeurism since they are difficult, if not almost impossible, to make out. It is again the body which is actually held up for inspection. The 'scientific' aegis of the journal operated here in a specific way in relation to the image. Together with the same compositional framing device as the previous illustration, this photograph's additional status as 'document' rendered even more respectable such overt nudity and any sexual connotation implied, in much the same way that the familiar convention of mythologising the nude in western fine art supposedly masked the sexuality of the sitter sufficiently to render nudity inoffensive to bourgeois sensibilities.” (Coombes 12-13)

Images were often adapted, reproduced, replicated — thus circulating in several forms and in varying contexts. For example…

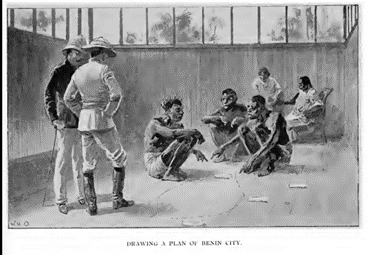

(Left) Joseph Holland Tringham, Chief Dore and Three Other Natives Drawing a Rough Plan of Benin City with Matches, Paper and Cork on the floor of the ViceConsulate, New Benin, before the Vice-Consul and Commander Bacon, engraving, published in the Illustrated London News (27 March 1897

(Right) “W.H.O.”, Drawing a Plan of Benin City, illustration in Commander R. H. Bacon, Benin the City of Blood (London and New York, 1897), p. 30.

Images in public circulation, e.g. in the illustrated press Are images constitutive or reflective? In other words: do they create new perceptions, or do they reveal existing ones?

Some quotes from the gallery

“Sainsbury African Galleries dedicated to Henry Moore OM CH”

“early Western accounts of Benin and the size and splendour of its capital, Benin City, were highly favourable. However, as Western interests encroached on the area in the late 19th century, Benin was increasingly depicted as a place of oppression and human sacrifice.”

“When the British attacked Benin City in 1897, the plaques were found in a storehouse, having been previously removed from the palace walls.”

Interior of the Royal Palace during looting, showing Captain Charles. Herbert Philip Carter, ‘E.P. Hill,’ and an unnamed man in February 1897. Pitt Rivers Museum, accession number 1998.208.15.11

“The Benin plaque is no mere work of art but rather the residue of a vast cultural experience that is now decontextualized. It was removed from its proper place in the aftermath of a mass killing, amid the stench of human bodies. It emerged from a landscape with a burning city. To describe it was being part of the “Robert Owen Lehman Collection”—to center its history on its having been purchased at auction by a wealthy American—is to suppress the plain truth of why such a thing is in other people’s keeping. To speak even of a ‘punitive expedition’, as is commonly done in the literature on Benin, is to accept the British version: that vengeance for the deaths of five or seven white men justified the destruction of the life-worlds of hundreds of thousands of people. It is to tacitly accept that the mission to ‘civilize’ Benin was worth the destruction of Benin’s civilization and the mass murder of its people. […] We know not to touch objects in museums. We are all obsessed with preservation and we revere scholarship and curation. But we have not been concurrently taught to value the life-worlds of others, their autonomy, their ancestral rights. Particularly if the people in question are from the African continent, their ingenuity can be appreciated, their artifacts can be acquired and subjected to analysis, but their actual lives cannot be valued. What does it mean to care about art but not about the people who made that art?” Teju Cole, Tremors (2023) — in which the narrator is speaking about the Benin “Bronzes” in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

#art#art gallery#artwork#writing#art tag#essay#paintings#art exhibition#art show#art history#colonial violence#colonization#colonialism#artists#history lesson#historical#history#world building#world#world politics#words#essay writing#writers#writeblr#writers and poets#drawings#lecture#dark academia#colonial history#colonial art

0 notes

Photo

''THE RISING SUN” The demand for palm oil exploration refered to as Red Gold in West Africa and exportation to Great Britain became very high in the 1700. In a slave camp at the heart of the Bight of Biafra (Igbo land), a woman champions the course and stands up to British tyranny even in the face of death. Based on true events, After trying to negotiate a coordinated effort between the Arochukwu kingdom which was a powerful kingdom and the NRI Kingdom, an unexpected stranger offers to help. Can she trust the son of the very man she calls master in her quest to liberate and restore their dignity in the land of The Rising Sun? #RISINGSUNTHEMOVIE DIRECTED/PRODUCED BY @Bakiatthomas DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY 1 @reneettat DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY 2 @grantfimz EDITOR @ukaegbuchikezie ASSISTANT DIRECTOR @tonia_obieze SCRIPT SUPERVISOR @obede97 PRODUCTION MANAGER @Richardking ART DIRECTOR @seleosele COSTUME DESIGN @ogeozobu MAKE-UP ARTIST/HAIR STYLIST @prettyambrose MAKE-UP ASSISTANT 1 @officialogoopatrick MAKE-UP ASSISTANT 2 @glorytogloryokor MAKE-UP ASSISTANT 3 @bella judith MAKE-UP ASSISTANT 4 @odiagbejane SFX MAKE-UP @_angelictouch8700_ ASSISTANT SFX @bollababy_b PROPS/SET DESIGN @uduogwujude81 ASSISTANT PROPS/SET @marleyking SOUND ENGINEER @izuchukwuanozie951 CHIEF GRIP @Imeh_etetim CAST DIRECTOR @official_promise_chidi FOCUS PULLER @akeemedia CAMERA ASSISTANT 1 @sunday_okogho CAMERA ASSISTANT 2 Naza_ĺens STILL PHOTOGRAPHER/BTS @Nonnyvisual PRODUCTION CONDINATOR @nwafadaofficial PRODUCTION ASSISTANT 1 @Mrbeejay_comedian PRODUCTION ASSISTANT 2 @brodajoker PRODUCTION ASSISTANT 3 @Chiboix_Conq CAST @peteedochie @charlesndawurum @ebelleokaro @smithnnebe @farielysian @adaeze.onuigbo @cesar8m @maximusjohn47 @chioma_okafor @gigi_boo_official @snowwhiteey @officialkingsley_black @temperature3d @jojomagbisa1 @zeal.ibibia @cubaking01 @uzoamakaotuadinma @adesuweh71 @zeezeezee57 @elvisgift948 @amakailoke @officialblessingdickson @ojiegentle @josephkrystel @officialmoses24 @blessingossai @onyii_giftedofficial @stephensarah2022 @akumsinachi_ @chima.daniels @precious_egbuchiri8 @officialemperorchima @okoye_reginaldnelson @effiongjuliet @ngonadi_chinenye https://www.instagram.com/p/CqVIyzKNuNr/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Which Country You Think You're From..

I'm Banking On Angola..

Or The Bight Of Biafra (Nigerian Coast)..

I Study Them All..

Just In Case..

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Igbo people (English: /ˈiːboʊ/; also Ibo, formerly also Iboe, Ebo, Eboe, Eboans, Heebo; natively Ṇ́dị́ Ìgbò [ìɡ͡bò] ) are an ethnic group native to the present-day south-central and southeastern Nigeria. Geographically, the Igbo homeland is divided into two unequal sections by the Niger River – an eastern (which is the larger of the two) and a western section. The Igbo people are one of the largest ethnic groups in Africa.

Before British colonial rule in the 20th century, the Igbo were a politically fragmented group, with a number of centralized chiefdoms such as Nri, Arochukwu, Agbor and Onitsha. Frederick Lugard introduced the Eze system of "Warrant Chiefs". Unaffected by the Fulani War and the resulting spread of Islam in Nigeria in the 19th century, they became overwhelmingly Christian under colonization. In the wake of decolonisation, the Igbo developed a strong sense of ethnic identity. During the Nigerian Civil War of 1967–1970 the Igbo territories seceded as the short-lived Republic of Biafra. MASSOB, a sectarian organization formed in 1999, continues a non-violent struggle for an independent Igbo state.

Small ethnic Igbo populations are found in Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea, as well as outside Africa. Chambers (2002) argued that many of the slaves taken from the Bight of Biafra across the Middle Passage would have been Igbo. These slaves were usually sold to Europeans by the Aro Confederacy, who kidnapped or bought slaves from Igbo villages in the hinterland. Igbo slaves may have not been victims of slave-raiding wars or expeditions, but perhaps debtors or Igbos who committed within their communities alleged crimes. The Igbo were dispersed to colonies such as Jamaica, Cuba, Saint-Domingue, Barbados, the future United States, Belize and Trinidad and Tobago, among others. Elements of Igbo culture can still be found in these places.

1. Igbo Nigerian wedding

2. Igbo man with facial scarifications, called ichi. Photo by by Northcote Thomas, late 19th-early 20th century

3. Igbo brides (click to enlarge)

4. Igbo woman from Awka, Nigeria ca. 1935

5. Three Igbo women, early 20th century

6. Igbo Roman Catholics in the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels, Los Angeles, California

7. A modern Igbo wedding, Nnewi, Nigeria

10. An Igbo woman wearing brass anklets called ogba. These are fashion, not punishment.

11. Igbo people celebrating the New Yam festival in Dublin, Ireland

#fashion#igbo#nigeria#nigerian fashion#africa#african fashion#jewelry#subsaharan africa#subsaharan african fashion#headdress#i mean#you could argue the anklets are BOTH fashion AND punishment#that's how i feel about high-heeled shoes

218 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Decks of a Slave Ship of the Middle Passage

The Middle Passage was the leg of the Atlantic slave trade that transported people from Africa to North America, South America and the Caribbean. It was called the Middle Passage because the slave trade was a form of Triangular trade; boats left Europe, went to Africa, then to America, and then returned to Europe. They also made a stop in the West Indies for food, supplies, or traded molasses or rum for the slaves.

Slave traders acquired slaves by purchasing them from numerous ports in Africa. They were able to pack nearly 300 slaves and approximately 35 crew into most slave ships. The men were normally chained together in pairs to save space - right leg to the next man's left leg - while the women and children may have had somewhat more room. The captives were fed very small portions of corn, yams, rice, and palm oil, normally just enough to sustain them. Sometimes captives were allowed to move around during the day, but many ships kept the shackles on throughout the journey.

It is estimated that of the 15 million that made the journey, 3 million did not survive. Disease, starvation, and the length of the passage were the main contributors to the death toll. Many believe that overcrowding caused this outrageously high deathrate, but amoebic dysentery and scurvy were the main problems. Additionally, outbreaks of smallpox, measles, and other diseases spread rapidly in the close-quarter compartments. Slave ships might take anywhere from one to six months to cross the Atlantic depending on the weather conditions at sea. The death rate rose steadily with the length of voyage, as the risk of dysentery increased with longer stints at sea, and the quality and amount of food and water diminished with every passing day.

Precise records are not available to provide an actual death toll, but it is estimated that as many as 8 million slaves may have perished to bring 4 million to the Caribbean islands. This number does not include the slaves brought to North or South America. Here we have a holocaust that is hardly mentioned and acknowledged by the western world. yet is ever bit as significant as the Jewish holocaust. And has had far more a impact on a group of people, than the vile acts of the second world war

The Atlantic

The Atlantic slave trade was the purchase and transport of Africans into bondage and servitude in the New World. It is sometimes called the Maafa by African Americans. This term means holocaust or great disaster in kiSwahili. The slaves were one element of a three-part economic cycle-the Triangular Trade and its infamous Middle Passage-which ultimately involved four continents, four centuries and the lives and fortunes of millions of people.

Research published in 2006 [1] reports the earliest known presence of slaves in the New World. A burial ground in Campeche, Mexico suggests slaves had been brought there not long after Hernán Cortés completed the subjugation of Mexico. Contemporary historians estimate some 12 million individuals were taken from west Africa to North, Central and South America and the Caribbean Islands by European colonial/imperialist powers.

Origins

The slave trade originated in a shortage of labour in the new world. The first slaves used were Aboriginal peoples, but they were not numerous enough and were being decimated by European cruelty and diseases. It was also difficult to get Europeans to emigrate to the colonies, despite incentives such as indentured servitude or even distribution of free land (mainly in the English colonies that became the United States). Massive amounts of labour were needed for mining, and especially for the plantations in the labor-intensive growing, harvesting and (semi-)processing of sugar (also for rum and molasses), cotton and other prized tropical crops which could not be grown profitably - in some cases, could not be grown at all - in the colder climes of Europe. (It was cheaper to import them American colonies than to import them from the Ottoman empire, etc.) To meet this demand for labour European traders thus turned to Western Africa, especially Guinea as a source of slaves.

There, Europeans tapped into the African slave trade that saw slaves transported to the coast of Guinea where they were sold at European trading forts in exchange for muskets, manufactured goods, and cloth. As a rule [citation needed], they were not stolen by the Europeans but captured in tribal wars, in many cases even started with a view to the capture of fellow Africans- given the modest prices they asked, African labor was clearly considered abundant, not very valuable.

The principal areas of the slave trade in Africa were Senegambia (present day Senegal, Gambia, Guinea and Guinea Bissau), Sierra Leone (including the area that later became Liberia), Windward Coast (modern Ivory Coast), Gold Coast (Ghana), Bight of Benin (Togo, Benin and western Nigeria), Bight of Biafra (Nigeria south of the Benue River, Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea), Central Africa (Gabon, Angola, Democratic Republic of the Congo) and Southeast Africa (Mozambique and Madagascar).

The number of slaves sold to the new world varied throughout the slave trade. The most widely accepted statistics [citation needed] claim Senegambia provided about 5.8%, Sierra Leone 3.4%, Windward Coast 12.1%, Gold Coast 14.4%, Bight of Benin 14.5%, Bight of Biafra 25%, Central Africa 23% and Southeast Africa 1.8%.

The first slave traders were Portuguese who desired workers for their mines and sugar plantations in Brazil. When the Dutch seized much of Brazil and became the dominant trading power in seventeenth century they became the leading traders selling slaves to both their own colonies and to British and Spanish ones. As Britain rose in naval power and controlled more of the Americas they became the leading slave traders, mostly operating out of Liverpool and Bristol. By the late 17th century, one out of every four ships that left Liverpool harbour was a slave trading ship [citation needed]. Other British cities also profited from the slave trade. Birmingham was the largest gun producing city in Britain at the time, and guns were traded for slaves. 75% of all sugar produced in the plantations came to London to supply the highly lucrative coffee houses there.

The slave trade was part of the triangular Atlantic trade, which was probably the most important and profitable trading route in the world. Ships from Europe would carry a cargo of manufactured trade goods to Africa. They would exchange the trade goods for slaves which they would transport to the Americas. In the Americas, they would sell the slaves and pick up a cargo of agricultural products, often produced with slave labour, for Europe. The value of this trade route was that a ship could make a substantial profit on each leg of the voyage. The route was also designed to take full advantage of prevailing winds and currents. For example, the trip from the West Indies or the southern US to Europe would be assisted by the Gulf Stream. The outward bound trip from Europe to Africa would not be impeded by the same current.

The slave trade was supported by church teachings and the introduction of the concept of the black man's and white man's burdens. Under this black men were expected to labour because they were not Christian and white men were charged with the duty of imposing the conditions of labour upon them.

Slavery was involved in some of the most profitable industries of the time: 70% of the slaves brought to the new world were used to produce sugar, the most labour intensive crop. The rest were employed harvesting coffee, cotton, and tobacco, and in some cases in mining. The West Indian colonies of the European powers were some of their most important possessions and they went to extremes to protect and retain them. For example, in 1763, France agreed to giving the vast colony of New France in exchange for keeping the minute Antillian island of Guadeloupe (still a French overseas département).

By far the most successful West Indian colonies in 1800 belonged to the United Kingdom. After entering the sugar colony business late, British naval supremacy and control over key islands such as Jamaica, Trinidad, and Barbados and the territory of British Guiana gave it an important edge over all competitors; while many lost their shirt, some made enormous fortunes, even by upper class standards. This advantage was reinforced when France lost its most important colony, St. Dominigue (western Hispaniola, now Haiti), to a slave revolt in 1791 and supported revolts against its rival Britain, after the 1793 French revolution in the name of liberty (but in fact opportunistic selectivity). The British islands produced the most sugar, and the British people quickly became the largest consumers of sugar. West Indian sugar became ubiquitous as an additive to Chinese tea. Products of American slave labour soon permeated every level of British society with tobacco, coffee, and especially sugar all becoming indispensable elements of daily life for all classes.

End of the Atlantic slave trade

In Britain, and in other parts of Europe, opposition developed against the slave trade. Led by the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) and establishment Evangelicals such as William Wilberforce the movement was joined by many and began to protest the trade. They were opposed by the owners of the colonial holdings; despite this Britain banned the slave trade in 1807, imposing stiff fines for any slave found aboard a British ship. That same year the United States banned the importation of slaves. Denmark, who had been very active in the slave trade, was the first country to ban the trade through legislation (1792) to take effect from 1803. The Royal Navy, which then controlled the world's seas, moved to stop other nations from filling Britain's place in the slave trade and declared that slaving was equal to piracy and could be punished by death.

For the British to end the slave trade, significant obstacles had to be overcome. In the 18th century, the slave trade was an integral part of the Atlantic economy. The economies of the European colonies in the Caribbean, the American colonies, and Brazil required vast amounts of man power to harvest the bountiful agricultural goods. In 1790 the British West Indies, islands such as Jamaica and Barbados had a slave population of 524 000, while the French had 643 000 in their West Indian possessions. Other powers such as Spain, the Netherlands, and Denmark had large numbers of slaves as well. Despite these high populations more slaves were always required. Harsh conditions and demographic imbalances left the slave population with well below replacement fertility levels. Between 1600 and 1800 the English imported around 1.7 million slaves to their West Indian possessions. The fact that there were well over a million fewer slaves in the British colonies than had been imported to them illustrates the conditions in which they lived.

How did the abolition of the slave trade occur if it was so economically important and successful? The historiography of answers to this question is a long and interesting one. Before the Second World War the study of the abolition movement was performed primarily by British scholars who believed that the anti-slavery movement was probably "among the three or four perfectly virtuous pages ... in the history of nations"

This opinion was controverted in 1944 by the West Indian historian, Eric Williams, who argued that the end of the slave trade was a result of economic transitions totally unconnected to any morality. Williams' thesis was soon brought into question as well, however. Williams based his argument upon the idea that the West Indian colonies were in decline at the early point of 19th century and were losing their political and economic importance to Britain. This decline turned the slave system into an economic burden that the British were only too willing to do away with.

The main difficulty with this argument is that the decline only began to manifest itself after slave trading was banned in 1807. Before then slavery was flourishing economically. The decline in the West Indies is more likely to be an effect of the suppression of the slave trade than the cause. Falling prices for the commodities produced by slave labour such as sugar and coffee can be easily discounted as evidence shows that a fall in price leads to great increases in demand and actually increases total profits for the importers. Profits for the slave trade remained at around ten percent of investment and showed no evidence of being on the decline. Land prices in the West Indies, an important tool for analyzing the economy of the area did not begin to decrease until after the slave trade was discontinued. The sugar colonies were not in decline at all, in fact they were at the peak of their economic influence in 1807.

Williams also had reason to be biased. He was heavily involved in the movements for independence of the Caribbean colonies and had a motive to try to extinguish the idea of such a munificent action by the colonial overlord. A third generation of scholars lead by the likes of Seymour Drescher and Roger Anstey have discounted most of Williams' arguments, but still acknowledge that morality had to be combined with the forces of politics and economic theory to bring about the end of the slave trade.

The movements that played the greatest role in actually convincing Westminster to outlaw the slave trade were religious. Evangelical Protestant groups arose who agreed with the Quakers in viewing slavery as a blight upon humanity. These people were certainly a minority, but they were a fervent one with many dedicated individuals. These groups also had a strong parliamentary presence, controlling 35-40 seats at their height. Their numbers were magnified by the precarious position of the government. Known as the "saints" this group was led by William Wilberforce, the most important of the anti-slave campaigners. These parliamentarians were extremely dedicated and often saw their personal battle against slavery as a divinely ordained crusade.

After the British ended their own slave trade, they were forced by economics to press other nations into placing themselves in the same economic straitjacket, or else the British colonies would become noncompetitive with those of other nations. The British campaign against the slave trade by other nations was an unprecedented foreign policy effort. Denmark, a small player in the international slave trade, and the United States banned the trade during the same period as Great Britain. Other small trading nations that did not have a great deal to give up such as Sweden quickly followed suit, as did the Dutch, who were also by then a minor player.

Four nations objected strongly to surrendering their rights to trade slaves: Spain, Portugal, Brazil (after its independence), and France. Britain used every tool at its disposal to try to induce these nations to follow its lead. Portugal and Spain, which were indebted to Britain after the Napoleonic Wars, slowly agreed to accept large cash payments to first reduce and then eliminate the slave trade. By 1853 the British government had paid Portugal over three million pounds, and Spain over one million in order to end the slave trade. Brazil, however, did not agree to stop trading in slaves until Britain took military action against its coastal areas and threatened a permanent blockade of the nation's ports in 1852.

For France, the British first tried to impose a solution during the negotiations at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, but Russia and Austria did not agree. The French people and government had deep misgivings about conceding to Britain's demands. Not only did Britain demand that other nations ban the slave trade, but also demanded the right to police the ban. The Royal Navy had to be granted permission to search any suspicious ships and seize any found to be carrying slaves, or equipped for doing so. It is especially these conditions that kept France involved in the slave trade for so long. While France formally agreed to ban the trading of slaves in 1815, they did not allow Britain to police the ban, nor did they do much to enforce it themselves. Thus a large black market in slaves continued for many years. While the French people had originally been as opposed to the slave trade as the British, it became a matter of national pride that they not allow their policies to be dictated to them by Britain. Also such a reformist movement was viewed as tainted by the conservative backlash after the revolution. The French slave trade thus did not come to a complete halt until 1848.

AS THE JEWS, QUITE RIGHTLY INSIST THEIR HOLOCAUST BE REMEMBERED. SO TO SHOULD THE DESCENDANTS OF SLAVES, BLACKS / NEGROES OF THE AMERICAS INSIST THAT THE WORLD REMEMBER AND ACKNOWLEDGE THE CRIMES PERPETRATED AGAINST THEM IN THIS PERIOD AND SINCE.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Really annoyed when people constantly talk about how Black Americans don’t know where the roots are.

U know there’s this spooky thing called slavery that happened.

Also our black bothers and sisters in the Carribbean and Latin American never get their identity questioned. They don’t know there African roots either but they’re identity and culture is respected and demeaned legitimated. Black Americans aren’t.

I feel this constant neglect and disrespect for Black American culture and identity boils down to the fact we’re American. As we all know America is imperialist af and unfortunately Black Americans get lumped into that.

When it comes to roots I can confidently tell u the roots ain’t from one location. It’s literally an accumulation from various ethnic groups from West and Central Africa (with a lil bit of ancestry from Madagascar and Mozambique”. A simple google search will tell u this information.

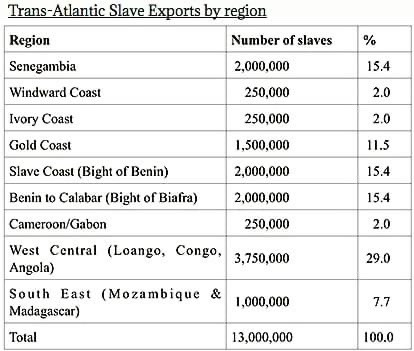

“According to the figures published by Hugh Thomas, around 13 million Africans were deported among whom 11 million arrived alive in the Americas. Less than 5% traveled to the Northern American States formally held by the British. Senegambia, the Slave Coast (Bight of Benin), and the Bight of Biafra exported each approximately 15.4% of the total of the slaves. Central Africa, where the slave trade lasted longer, contributed approximately for 29%. One million people (7.7%) were taken from South East (Mozambique & Madagascar).”

So there u have it. Here’s the ancestry/roots of Black Americans and the rest of the African diaspora who descend from enslaved Africans. Now leave my folks alone.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

BANTU PLACE NAMES IN SOUTH CAROLINA

Joseph E. Holloway, Ph.D.

California State University Northridge

When Prof. John F. Szwed wrote "Africa lies just off the coast of Georgia," he was referring to the mainland coastal areas and adjacent Sea Islands of Georgia and South Carolina. These are places where the most direct living repository of African culture anywhere in North America exists.

During the slave trade and until 1858, well after the importation of slaves was banned, there was an undetected traffic in illegally transported Africans brought directly from Africa, South America, and the Caribbean to the Sea Islands. In spite of the U.S. Navy patrols sent to enforce the ban against importing slaves, the trade infiltrated the complex watery wilderness off the southern coast of the United States, because of the geographic isolation of the Sea Islands, African culture has been retained in almost every element of Sea Island culture, including art, food, folktales, language, and oral tradition. In South Carolina, African naming practices, net making, fishing practices, the right shout, basketry, and burial ceremonies are woven into the local culture.

The Sea Islands begin north of Georgetown, South Carolina, and extend through parts of northern Florida. Approximately 1,000 islands along the coast of South Carolina and Georgia are separated from the mainland by marshes, alluvial streams, and rivers. Some of the islands are bordered by the Atlantic Ocean and are 20 miles or more from the mainland. They range in size from very small and uninhabitable islands, to the second largest island, Johns Islands, South Carolina, in the United States. South Carolina was settled by a large number of enslaved of Central Africa and as table 1 shows, imported more Africans from Central Africa than any other nation from West Africa. Because of South Carolina’s primary role in the slave trade, it is not surprising to have found 93 African place names of Bantu origin. This search has been aided by a publication of the University of South Carolina, Names in South Carolina, which has provided a wealth of place name materials.

TABLE 1. Summary of Africans Imported into Charleston, S.C.

Coastal Region Total Africans

(Estimated) Percent

Senegambia 17,575 16.5

Sierra Leone 5,593 5.3

Windward Coast 15,554 14.6

Gold Coast 13,070 12.3

Bight of Benin 1,394 1.3

Bight of Biafra 1,914 1.8

Angola 34,166 32.1

Madagascar, Mozambique 473 0.4

Others (Africa, Guinea, and Unknown) 16,767 15.7

Total 106,506

Adapted with permission from "A Reconsideration of the Sources of the Slave Trade to Charleston, S.C.," an unpublished essay by William S. Pollitzer.

Bantu Place Names in South Carolina

Place Name Origin Meanings

1. Alcolu Alakana - hope for; long for; desire exceedingly

2. Ampezan Ampeje - let him give to me

3. Ashepoo Ashipe - let him kill

4. Attakulla Atuakuile - let him intercede for us, speak on our behalf

5. Becca Beka - exaggerate; go beyond the bounds

6. Beetaw Bita - handcuffs; manacles; shackles used in slavery

7. Boyano Mbuy’enu - your friend

8. Boo-Boo Mbubu - imbecile; a stupid person

9. Booshopee Bushipi - murder; killing

10. Bossis Botshisha - be beaten down, trampled upon

11. Canehoy Kenahu - he isn’t here

12. Calwasie Kaluatshi - short battlefront; line formed for the chase

13. Caneache Kenaku - he isn’t here (at this spot)

14. Cashua Neck Kashia - river eel

15. Chachan Tshiatshiakana - not know what to do, where to turn for help

16. Chebash Tshibasu - chieftain’s seat (symbolic block of wood on which chief sits)

17. Cheeha Tshipa - make a vow; curse

18. Chepasbe Tshipese - any small portion, piece, bit broken off or taken from the whole

19. Chichessa Tshitshenza -big doing; important events; happening

20. Chick Tshika - guard; keep a secret (imperative)

21. Chinch Row Tshinji bug; insect

22. Chiahao Tshiahu - working group, field gang; family that works together

23. Chiquola Tshikole - strong; well; grown; mature

24. Chota Tshiota - the clan; extended family group

25. Chukky Tshuki - don’t answer; don’t replay; be closemouthed (imperative)

26. Cofitachequi Kufitshishi - don’t allow to pass over; don’t let cross over to the other side, go over the boundary

27. Combahee Kombahu - sweep here (imperative)

28. Cumbee Nkumbi - large, wedge-shaped, slit drum beaten on both sides

29. Coosabo Kusabo - they shake their heads, say "no"

30. Coosa Nkusa - louse, lice

31. Cooterborough Nkuda - turtle, terrapin; cooterpaw

32. Cuakles Kuakkulas - to talk, converse (slang form)

33. Cuffee Kofi Cuffee Town; Akan day name for male child born on Friday

34. Cuffie Creek Kufi -don’t die

35. Dibidue Ndubilu - it is quickness, speed

36. Dongola Ndongola - I fix, prepare, work on

Eady Town Idi they are (common form of verb to be).

37. Ekoma Ekoma - finish up, come to an end or a conclusion

38. Elasie Elasha cause to pour, pour out; cause to throw

39. Flouricane Mvula ikenya - a storm is threatening

40. Gall Ngala - an embankment; raised walk between two flooded fields; a dam constructed in a river or steam for fishing purpose (Horse

41. Gall, Cane Gall, Spring Gall, Dry Gall)

42. Gippy or Jippy Tshipi short; Tshitupa tshipi; in a short time, in a jiffy

43. Hoot Gap Huta drag - drag away something very heavy, such as from a cleared area (imperative)

44. Jalapa Shalapa - remain here (imperative)

45. Kecklico Kekelaku - ignore, demean, deliberately snub (me) (imperative)

46. Kissah Kisa hate; be cruel, vicious, sadistic (imperative)

47. Lattakoo Luataku get dressed; put on clothes (imperative)

48. Lobeco Lobaku steal; take by stealth; nibble away at (imperative)

49. Loblolly Bay Lambulula distill, extract (turpentine, liquor, etc.)

50. Lota Lota dream (imperative)

51. Malpus Island Mapusa gun wadding

52. Mazych Majika finished, completed

53. Mepkin Mapeku shoulders

54. Muckawee ‘ Muka wee! Get out! Get gone! Scram!

55. Mump Fuss Row Mumpas! Give it to me! (slang form)

56. Oniseca Anyishaku ! traditional Luba-Kasai greeting

57. Oshila Oshila set fire to, burn up for someone else

58. Opopome Apopome let him be blind

59. Palachocolas Palua tshikole when the strong one comes

60. Palawana Palua wanyi when mine comes

61. Parachucla Palua tshikula when the old one comes

62. Peedee Mpidi dark cloth worn during mourning, during time that all sexual relations are banned

63. Pinder Town Mpinda peanut; a town where enslaved Africans grew peanuts

64. Pockoy Island Mpoka frankness, truth, sincerity

65. Pooshee Mpuishe one who always completes, finishes his tasks

66. Quocaratchie Kuokolatshi to remove a heavy object, such as a log, from the forest

67. Saluca Saluka be in disorder; society all disrupted, upset, in turmoil

68. Sauta Saula weep, cry aloud

69. Shiminally Jiminayi get lost; disappear from sight (imperative)

70. Teckle-gizzard Tukulukaji numbness in limbs from circulation cut off by tight bindings, ropes, chains

71. Toogoodoo Tukuta we are satisfied, filled (with food)

72. Toobedoo Tub-etu our language, our "Kituba"

73. Tomotely Tumutele let us name him, mention his name

74. Tucapau Tukupau we give it to you

75. Tullifinny Tula mfinu pull off, pluck off undeveloped ears of corn; undeveloped peanuts in farming

76. Una Unua drink, drinking

77. Untsaiyi Utusadila serve us, be in servitude to us; wait on us

78. Wadboo Wa ndapu place of joking, teasing, relaxed conduct, indiscretions;

African-American community

79. Wambaw Wambau say it

80. Wampee Wampe give to me

81. Wantoot Wan tutu place of the elder brother

82. Wappoo Wapu give it

83. Wappaoolah Wapaula lay waste, pillage, loot (imperative)

84. Watacoo Wataku be naked, without clothing

85. We Creek We! Hey, you!

86. Weeboo Weba chase; put to flight; make a fugitive of someone.

87. Weetaw Wetau ours, our very own!

88. Wimbee Muimbi a singer

89. Wosa Wosa do, make, produce, prepare (general verb for all types of work; imperative)

90. Yauhaney Ya uhane go that you may sell, barter

91. Yeka Yika talk, converse, have conversation with

92. Yoa Yowa be thin, emaciated, weak from hunger;

93. Zemps Zemba come to a halt, be immobile, paralyzed, unable to do or act for oneself

1 note

·

View note

Text

Igbo Slave Trade

In Jamaica, the bulk of Igbo slaves arrived relatively later than the rest of other arrivals of Africans on the Island in the period after the 1750s. The heaviest increase in forced Migrations to the Americas occurred between 1790 and 1807. Jamaica, after Virginia, became the second most common destination for slaves arriving from the Bight of Biafra. As the Igbo formed the majority from the bight, they became largely represented in Jamaica in the 18th and 19th century. Buckra" was a term introduced by Igbo and Efik slaves in Jamaica to refer to white slave owners and overseers. After the abolition of slavery in Jamaica in the 1830s, Igbo people also arrived on the island as indentured servants between the years of 1840 and 1864 along with a majority Kongo and "Nago" (Yoruba) people Igbo and Akan slaves affected drinking culture among the black population in Jamaica, using alcohol in ritual and libation. In Igboland as well as on the Gold Coast, palm wine was used on these occasions and had to be substituted by rum in Jamaica because of the absence of palm wine. Jonkonnu, a parade that is held in many West Indian nations, has been attributed to the Njoku Ji "yam-spirit cult", Okonko and Ekpe of the Igbo. Several masquerades of the Kalabari and Igbo have similar appearance to those of Jonkonnu masquerades. Specialists in "Obia" (also spelled Obea) were known as "Dibia" (doctor, psychic) practiced similarly as the obeah men and women of the Caribbean, like predicting the future and manufacturing charms. In Jamaican mythology, "River Mumma", a mermaid, is linked to "Oya" of the Yoruba and "Uhamiri/Idemili" of the Igbo In the 19th century the state of Virginia received around 37,000 slaves from Calabar. Igbo peoples constituted the majority of enslaved Africans in Maryland.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Music of African heritage in Cuba derives from the musical traditions of the many ethnic groups from different parts of West and Central Africa that were brought to Cuba as slaves between the 16th and 19th centuries. Members of some of these groups formed their own ethnic associations or cabildos, in which cultural traditions were conserved, including musical ones. Music of African heritage, along with considerable Iberian (Spanish) musical elements, forms the fulcrum of Cuban music.

Much of this music is associated with traditional African religion – Lucumi, Palo, and others – and preserves the languages formerly used in the African homelands. The music is passed on by oral tradition and is often performed in private gatherings difficult for outsiders to access. Lacking melodic instruments, the music instead features polyrhythmic percussion, voice (call-and-response), and dance. As with other musically renowned New World nations such as the United States, Brazil and Jamaica, Cuban music represents a profound African musical heritage.

Clearly, the origin of African groups in Cuba is due to the island's long history of slavery. Compared to the USA, slavery started in Cuba much earlier and continued for decades afterwards. Cuba was the last country in the Americas to abolish the importation of slaves, and the second last to free the slaves. In 1807 the British Parliament outlawed slavery, and from then on the British Navy acted to intercept Portuguese and Spanish slave ships. By 1860 the trade with Cuba was almost extinguished; the last slave ship to Cuba was in 1873. The abolition of slavery was announced by the Spanish Crown in 1880, and put into effect in 1886. Two years later, Brazil abolished slavery.

Although the exact number of slaves from each African culture will never be known, most came from one of these groups, which are listed in rough order of their cultural impact in Cuba:

The Congolese from the Congo Basin and SW Africa. Many ethnic groups were involved, all called Congos in Cuba. Their religion is called Palo. Probably the most numerous group, with a huge influence on Cuban music.

The Oyó or Yoruba from modern Nigeria, known in Cuba as Lucumí. Their religion is known as Regla de Ocha (roughly, 'the way of the spirits') and its syncretic version is known as Santería. Culturally of great significance.

The Kalabars from the Southeastern part of Nigeria and also in some part of Cameroon, whom were taken from the Bight of Biafra. These sub Igbo and Ijaw groups are known in Cuba as Carabali,and their religious organization as Abakuá. The street name for them in Cuba was Ñáñigos.

The Dahomey, from Benin. They were the Fon, known as Arará in Cuba. The Dahomeys were a powerful group who practised human sacrifice and slavery long before Europeans arrived, and allegedly even more so during the Atlantic slave trade.

Haiti immigrants to Cuba arrived at various times up to the present day. Leaving aside the French, who also came, the Africans from Haiti were a mixture of groups who usually spoke creolized French: and religion was known as vodú.

From part of modern Liberia and Côte d'Ivoire came the Gangá.

Senegambian people (Senegal, the Gambia), but including many brought from Sudan by the Arab slavers, were known by a catch-all word: Mandinga. The famous musical phrase Kikiribu Mandinga! refers to them.

Subsequent organization

The roots of most Afro-Cuban musical forms lie in the cabildos, self-organized social clubs for the African slaves, and separate cabildos for separate cultures. The cabildos were formed mainly from four groups: the Yoruba (the Lucumi in Cuba); the Congolese (Palo in Cuba); Dahomey (the Fon or Arará). Other cultures were undoubtedly present, more even than listed above, but in smaller numbers, and they did not leave such a distinctive presence.

Cabildos preserved African cultural traditions, even after the abolition of slavery in 1886. At the same time, African religions were transmitted from generation to generation throughout Cuba, Haiti, other islands and Brazil. These religions, which had a similar but not identical structure, were known as Lucumi or Regla de Ocha if they derived from the Yoruba, Palo from Central Africa, Vodú from Haiti, and so on. The term Santería was first introduced to account for the way African spirits were joined to Catholic saints, especially by people who were both baptized and initiated, and so were genuine members of both groups. Outsiders picked up the word and have tended to use it somewhat indiscriminately. It has become a kind of catch-all word, rather like salsa in music.

The ñáñigos in Cuba or Carabali in their secret Abakuá societies, were one of the most terrifying groups; even other blacks were afraid of them:

Girl, don't tell me about the ñáñigos! They were bad. The carabali was evil down to his guts. And the ñáñigos from back in the day when I was a chick, weren't like the ones today... they kept their secret, like in Africa.

African sacred music in Cuba

All these African cultures had musical traditions, which survive erratically to the present day, not always in detail, but in the general style. The best preserved are the African polytheistic religions, where, in Cuba at least, the instruments, the language, the chants, the dances and their interpretations are quite well preserved. In few or no other American countries are the religious ceremonies conducted in the old language(s) of Africa, as they are at least in Lucumí ceremonies, though of course, back in Africa the language has moved on. What unifies all genuine forms of African music is the unity of polyrhythmic percussion, voice (call-and-response) and dance in well-defined social settings, and the absence of melodic instruments of an Arabic or European kind.

Not until after the Second World War do we find detailed printed descriptions or recordings of African sacred music in Cuba. Inside the cults, music, song, dance and ceremony were (and still are) learnt by heart by means of demonstration, including such ceremonial procedures conducted in an African language. The experiences were private to the initiated, until the work of the ethnologist Fernando Ortíz, who devoted a large part of his life to investigating the influence of African culture in Cuba. The first detailed transcription of percussion, song and chants are to be found in his great works.

There are now many recordings offering a selection of pieces in praise of, or prayers to, the orishas. Much of the ceremonial procedures are still hidden from the eyes of outsiders, though some descriptions in words exist.

Yoruba and Congolese rituals

Main articles: Yoruba people, Lucumi religion, Kongo people, Palo (religion), and Batá

Religious traditions of African origin have survived in Cuba, and are the basis of ritual music, song and dance quite distinct from the secular music and dance. The religion of Yoruban origin is known as Lucumí or Regla de Ocha; the religion of Congolese origin is known as Palo, as in palos del monte.[11] There are also, in the Oriente region, forms of Haitian ritual together with its own instruments and music.

In Lucumi ceremonies, consecrated batá drums are played at ceremonies, and gourd ensembles called abwe. In the 1950s, a collection of Havana-area batá drummers called Santero helped bring Lucumí styles into mainstream Cuban music, while artists like Mezcla, with the lucumí singer Lázaro Ros, melded the style with other forms, including zouk.

The Congo cabildo uses yuka drums, as well as gallos (a form of song contest), makuta and mani dances. The latter is related to the Brazilian martial dance capoeira

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brownskin#brown skin#afrakans#african culture#fitness#afrakan spirituality#afro cuban music#afro cuban#igbo#yoruba#congo#african music

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

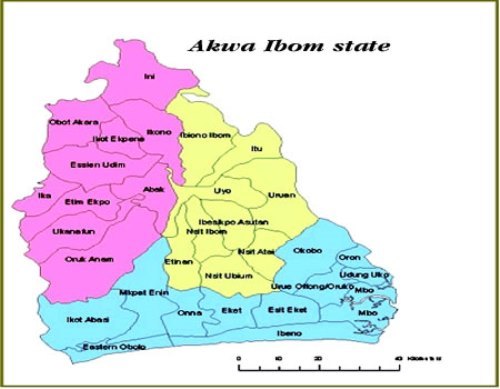

AKWA IBOM - THE PEOPLE, THE LAND AND THE NAME.

AKWA IBOM – THE PEOPLE, THE LAND AND THE NAME.

Akwa Ibom State is located in the coastal southern part of Nigeria. Its area formed part of cross Rivers state until 1987, when the state was created. Akwa Ibom is bounded by the Cross River on the east and by the Bight of Biafra of the Atlantic ocean on the south. There are extensive salt water mangrove swamps, along the coast and tropical rain forests and oil palms farther inland.

The state’s…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Toby Green, A Fistful of Shells: West Africa from the Rise of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution, 'Rivers of Cloth, Masks of Bronze: The Bights of Benin and Biafra', 2019

Masterlist

BUY ME A COFFEE

#art#art gallery#art hitory#artwork#writing#art tag#essay#paintings#art exhibition#art show#historical#art history#antiques#academic writing#essay writing#lecture#history lesson#colonialism#colonization#colonial violence#world#world politics#artists#writers#writers and poets#writeblr#history#stolen land#drawings#dark academia

0 notes

Text

“Biafra has nothing to do with Igbos, Ijaws own Biafra” – Asari Dokubo opens up

New Post has been published on https://thebiafrastar.com/biafra-has-nothing-to-do-with-igbos-ijaws-own-biafra-asari-dokubo-opens-up/

“Biafra has nothing to do with Igbos, Ijaws own Biafra” – Asari Dokubo opens up

Previous head of the Niger Delta Peoples Volunteer Force, Mujaheed Asari Dokubo has said that the name ‘Biafra’ steers clear of the Igbos.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push();

Dokubo, in a concise meeting with Arise Television, observed by POLITICS NIGERIA on Wednesday, uncovered that the term ‘biafra’ was instituted by an Ijaw man and was initially proposed by the Ijaws and not the Igbos. He additionally scrutinized the head of the Indigenous individuals of Biafra, IPOB for needing to make an ‘Igbo biafra’.

He said; “Ijaw is Biafra. Ijaws are split between the Bight of Benin and the Bight of Biafra. We are the proprietors of Biafra. Biafra is an Ijaw name, we own it”

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push();

“The region distinguished as Biafra is Ijaw. Perhaps a little ibibios towards the end and Oron individuals.”

“The genuine Biafra, the name Biafra, the geological area Biafra is Ijaw and a little Oron and a smidgen Ibibio.”

“In 1967, the eastern ijaws were important for Eastern district. An Eastern consultative gathering was assembled in Enugu and Francis, an ijaw man gave the name ‘Biafra’, moved the movement that Biafra ought to be received. Francis Opigo, and Biafra was embraced on the 30th of May 1967, the republic of Biafra was proclaimed which incorporated the eastern Ijaw inside our region.”

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push();

“In this way, Biafra steers clear of Igbos”

“The Biafran express that was proclaimed in 1967 was not an Igbo state.”, he said.

0 notes