#anglo saxon architecture

Text

©️Alistair Francis 2023

#photography#architecture#Manchester#alistairfrancis#reflection#Manchester Cathedral#Greater Manchester#archway#shapes#choir#victoria street#gothic revival#anglo saxon architecture

1 note

·

View note

Text

Whether the Arthur of legend actually existed is the subject of much debate. Per the British Library’s Hetta Elizabeth Howes, historical records show that a man named Arthur led resistance against the Saxons and Jutes around the fifth and sixth centuries C.E.; some Welsh accounts reference a similarly gifted warlord. The king of modern myth, however, only began to take shape in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain (1138).

Arthurian legends were widely shared throughout the 12th and 13th centuries, via manuscripts for the wealthy and oral storytelling for the broader population. Though earlier tellings emphasized Arthur’s strength in battle and nation-building skills, the tales eventually became part of the medieval romance tradition, wistfully yearning for a time of morality, chivalry and righteousness.

Arthur’s Stone was first linked to the mythical king prior to the 13th century, according to English Heritage. Its fame continued in the centuries that followed: Charles I camped in the area with his troops during the 17th-century English Civil Wars, and writer C. S. Lewis, who frequently walked by the site, based the Stone Table in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe on it.

— Archaeologists Begin First-Ever Excavation of Tomb Linked to King Arthur

#THIS IS SO COOL OMG#i had no idea that the stone table was based on this#or that there was actual evidence of king arthur having really existed#history#architecture#archaeology#folklore#books#c.s. lewis#narnia#neolithic#medieval#britain#england#anglo-saxons#arthur's stone (herefordshire)#king arthur#geoffrey of monmouth#charles i

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

early/high mideval european buildings are perfect for minecraft

#have y’all SEEN norman architecture?#it’s literally just like five feet of wall on the sides and then FOUR HUNDRED FEET OF ROOF#gothic architecture is the same but flip the ratios and add a round window in front!#anglo saxon architecture is the exeption it’s so rounded corners#the only good thing william the conqueror did was add hard corners to buildings#minecraft is underutilized in archeology

0 notes

Text

The 1st May marks the anniversary of the death of a remarkable Scottish born woman.

She is known to us by the Norman-French title “Matilda of Scotland” born around 1080 at Dunfermline and Christened with the name Edith,one of the eight children of King Malcolm III of Scotland and his second wife Saint Margaret. At her christening were her godfather Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy and the eldest son of King William I of England (the Conqueror) and her godmother, Matilda of Flanders, the wife of King William I of England (the Conqueror). The infant Matilda pulled at Queen Matilda’s headdress, which was seen as an omen that the younger Matilda would be a queen one day. In fact, she would marry Queen Matilda’ s son and Robert Curthose’s brother, King Henry I of England.

Thus with links to three different cultures, Anglo-Saxon, Scottish and Norman French, Edith was a marriageable prospect, but her eventual betrothal to Henry I of England seems, by all accounts, to have been a love match as much as a dynastic union. She was free to marry only after a court case at which she had to prove that her stay in a convent was for purposes of protection and that she never formally took the veil of a nun, such were the religious complexities at the time.

The character, education and birthright of Matilda of Scotland seem to have given her a high degree of autonomy at Henry’s court. She also had her separate sources of income, her own retinue of staff and was frequently left in virtual charge of the realm during his regular absences in Normandy. Her charters cover a wide range of issues and she was particularly interested in architecture, being responsible for several abbey building projects as well as bridge construction and the provision of England’s first public toilets, attached to a bath complex near at Queenhithe, a small and ancient ward of the City of London.

It is possible that in 1114 she sent masons north with her brother Alexander when he returned to Scotland after fighting alongside Henry in Wales. She herself was said to have “fluent honeyed speech” by Marbodius of Rennes and she filled her court with poets and musicians. She was responsible for commissioning a biography of her mother Margaret who was also renowned in Scotland for bringing light and colour to the Scottish Royal Court.

It is believed that Matilda (Edith) only returned once to Scotland during her lifetime and, due to the lack of surviving documentary evidence, her influence in Scotland is unknown. However, she is believed to have had a close relationship with her brothers, three of whom were kings north of the border.

Also absent from our history books, she may just possibly be better known to us as the “fair lady” in the nursery rhyme “London Bridge is falling down”. Her works of charity made her a queen beloved of all Londoners who also probably claimed her as a Wessex girl despite her Scottish birthplace.

Matilda of Scotland fulfilled her dynastic duty by giving birth to both a daughter, also called Matilda, and a son, William. William died in a tragic boat disaster shortly after Matilda’s own early death in 1118. She was only 38. Her daughter Matilda married the German Emperor Henry V and is known to us today as the Holy Roman Empress Matilda, the princess who became embroiled in a bitter English Civil War.

There is loads more about our forgotten English Queen here http://garethrussellcidevant.blogspot.com/.../daughter-of...

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

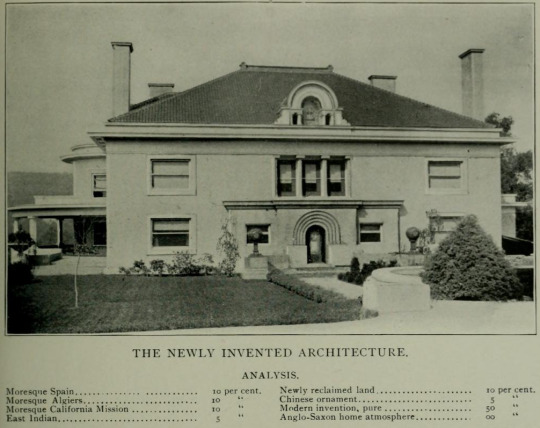

this dude from the 1910s hated modern architecture so bad lmao "anglo-saxon home atmosphere: 0%" he was fucking seething and gagging that it wasn't Literally Illegal to build a house looking like that. fascinating. he deserved to have a blog

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

reading up on Anglo-Saxon architecture and it’s very endearing to learn that yes, the Anglo-Saxons were perfectly capable of building with brick and stone, but they preferred wood for cultural reasons. why is that cute to me? like it’s almost a bit quaint. Arthur has wood wall paneling in 90% of his houses and he’s a massive snob about furniture and construction. like the man just goes feral for a good mahogany desk or wall paneling. he loves latticework too, regardless if it’s screens or balustrades or decoration or whatever; the Roman side of him combined with the Germanic side and now he wants lattice (preferably wood!) fucking everywhere for no good reason. he cannot and will not be stopped. it makes him feel cozy.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

British Folk Beliefs & Magick: Pagan-Christian Syncretism

Highlighting the influence of paganism on folklore, traditions, and magick in the British Isles from the Middle Ages and onward.

Christianity first began to spread throughout Britain in the 4th century when Christian Romans began interacting with our British ancestors. In Anglo-Saxon England, St. Augustine’s journey to Kent in the 6th century catalyzed the conversion. Christianity spread throughout Scotland and Wales as a result of several missionaries spreading word of this foreign faith. Contrary to the popular narrative, those inhabiting the British Isles at the time did not forget their native faith outright. Paganism shaped the many folk beliefs and customs that persisted throughout the Christian era. Folk magick, in simplest terms, is the people’s magick. It is shaped by various features of one’s environment - geography, ecology, history, religion, social structure, etc. Folk magick began to appear during the Middle Ages and continues in modern times, often combining elements of the heathen faith and Christianity. Folk beliefs were characterized by an acknowledgement of numerous spirits and folk magick often centers the Earth and making use of one’s natural resources. This article will outline some of the folklore, traditions, and magick of the British Isles.

Both household and land spirits were prominent figures within British folklore. Brownies are a type of house spirit thought to perform various household tasks, especially if they were treated with respect. These creatures are elvish in nature and appearance, sometimes described as house elves. Brownies are not small, in fact they are often described as being human sized and not particularly pleasant to look at. However, brownies carry out most of their chores during the night, so they are never seen. Despite being fairly helpful spirits, they could become mischievous if they felt offended. Boggarts are a similar type of spirit who may inhabit both the land and family homes. These creatures are much more troublesome than brownies and even destructive. They have the tendency to make a mess within the home and even harm animals. A repeatedly insulted brownie may transform into a boggart. Tales about household elves have been recorded by the Brothers Grimm and land spirits are notably featured in Shakespearean literature, such as Puck in a Midsummer Night’s Dream. The belief in such creatures are rooted in the pre-Christian veneration of husvaettir, or house spirits, and landvaettir, the land spirits. In Anglo-Saxon England, house spirits were recognized along with the cofgoda, or house deities. Moreover, elves are mentioned several times in Anglo-Saxon medical manuscripts, in which they are blamed for a variety of ailments that afflict both humans and animals alike. Anglo-Saxon elves were evidently more prone to causing difficulty, very much like the Boggarts of medieval England and Scotland. Another prominent nature spirit includes the Green Man, who symbolizes life, death, rebirth, fertility, and the spring season. Towards the end of the Medieval period, churches throughout Northwestern Europe featured architecture likely portraying the Green Man. For example, a church in Llangwm, Wales, is adorned with the image of a head with foliage emerging from its mouth. Such architecture has also been found in Asia and the Middle East, including the countries of India, Lebanon and Iraq. The Green Man is undoubtedly a legendary figure derived from nature deities. The Church likely viewed the Green Man as a representation of the danger and wildness of the outdoors, as suggested by Christian literature. The veneration of nature can be seen with May Day, which celebrates spring, the arrival of summer, and fertility. The May Pole acts as both a representation of the tree of life as well as a phallic symbol. This celebration persists in Ireland, Scotland, and England in the modern age, though it has become heavily Christianized.

Throughout medieval Britain, those who practiced magick were referred to as “cunning folk.” The cunning folk incorporated elements of folk magick and ceremonial magick into their practice, which was heavily shaped by both paganism and Christianity. Cunning folk were typically Christians, though they were viewed as heretics and church authorities accused them of working with the devil. Charms, herbal remedies, shamanism, and divination are prominent in the magick of the cunning folk. Furthermore, these individuals claimed to have a special connection to the spirit world and were assisted by magickal spirits such as fairies. The spirits often took the form of an animal such as a dog, cat, or goat, and could take one onto a spiritual journey to Elfhame. Magick was practiced more in rural parts of Britain and the majority of practitioners were solitary. The cunning folk used their magick for good, providing ill individuals who could not afford a physician with an herbal concoction, and scrying a crystal ball to uncover the identity of a thief. They even provided protection to individuals claiming to be victims of malevolent magick, but the Church still viewed their work as devilish and equally malicious. As mentioned in previous articles, charms for healing and protection were used in the pre-Christian era. Practitioners of magick continued to rely on the power of charms, though the charms of the cunning folk often quoted the bible or invoked the power of several Christian figures. The Sator Square, a magickal Latin palindrome, was also used for protection. Additionally, utilizing plants and other natural elements with the aim of curing an ailment have prominent heathen origins.

Not many cunning folk were literate, but those who were may have made use of a grimoire. Grimoires are books containing information and instructions on spellwork, invocation, as well as a variety of rituals, and they circulated throughout Britain once printing became more accessible. Many of the grimoires of the cunning folk were influenced by other magickal books, such as Cornelius Agrippa’s work on Western esotericism, Three Books of Occult Philosophy, which was translated into English in 1651. Arthur Gauntlet was an English physician living in London during the 17th century who’s own grimoire contained information found in both Agrippa and Reginald Scot’s works. During the 18th century, a French Kabbalistic grimoire called the Black Pullet was published and became popular amongst British magicians due to its information on talismans and amulets.

British folk magick centered a Christian cosmology as well as philosophy, and it was combined with the pagan elements of nature worship and plant magick. There was a recognition of the spirits that inhabited the land alongside us, while the Earth retained it’s role as a healer, provider, and protector. Folk magick is not static; it reflected the people’s needs, environment, and other social factors. The practice of the British folk magician was ever-evolving. The application of magick and even one’s theology likely shifted through major social changes such as the English reformation or laws persecuting those partaking in ritual work and conjuration. The beliefs, traditions, and magick of the British Isles reminds us that paganism never completely died out. Though the old gods were not recognized during the Christian period and continue to be vastly unrecognized in the modern age, the values and knowledge of our pagan ancestors has always persisted.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

i’m taking an elective (kind of like a one semester minor) in architecture rn and yesterday we were talking about a reading that mentioned an apartment complex in spain that had all the balconies overlook a courtyard in the middle to encourage community. and this girl (who’s from canada) mentioned how that would never work in north america bc there’d be issues of safety, and putting yourself at risk by being so “exposed” to your neighbors.

and it made me think like 🤔 no, it wouldn’t work in north america. but not bc spain is some crimeless utopia and this is gotham. there’s nothing inherently more dangerous about your neighbors knowing you exist in canada/usa vs in spain. but it wouldn’t work regardless *because* there’s this massive culture of distrust here that makes people think that just being able to look at your neighbor is already a hazard. there’s this deep-set belief that anyone you don’t already know is a threat (that goes beyond just being reasonably cautious).

(if anything, you might be safer knowing your neighbors well enough that they’d check up on you if they thought you were in danger imo)

ultimately the main issue is that anglo-saxon culture is just less social than romance cultures are, not necessarily just paranoid. but it does make you fink

#also idek if this is a matter of (north) american culture or like Modern Culture#cause i do think the sense of ‘stranger danger’ has increased massively in the last couple decades#hence why kids used to be able to play unsupervised which would never happen nowadays#but still it’s affected north america more for a reason#i feel like there is this sense of ‘dangerous until proven innocent’ and vice versa for hispanic culture#as someone who’s grown up in both‼️

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm getting that feeling of being slowly pulled into a research rabbit hole again...

How do you separate medieval architecture from Roman and Christian influences? With great difficulty, it turns out.

Basically throw pre-Romanised Celtic architecture, pre-Christianised Germanic architecture, and a smattering of Norse Viking era architecture into a blender, and forget everything you know about church or castle architecture...

So far (and this is simplifying things down to a criminal degree here) I've got roughly that Brittonic, Irish and Scottish Celts ere towards round houses and anti right angle constructions, Anglo Saxon's ere towards more rectangular and square dwellings, but can be partial to a circle or two at times, and the Norse like long things with spiky roofs.

Most of these are non-stone constructions too, so archaeological sources are somewhat sparse... Must Farm being a glorious and local exception, but one cannot build an architectural style from one marshland settlement alone.

Oh well, I do love a challenge.

Pretty Pictures Below:

Newgrange, County Meath, Ireland - 3200 BC (ish)

Photograph from Johnbod Wikimedia Commons

Skara Brae, Bay of Skaill, Orkney - 3180 BC-2500 BC

Photograph from Dr John F. Burka Wikimedia Commons

Reconstructed Longhouse, Viking Museum Borg, Vestvågøy/Lofoten, Norway

Photograph from Jörg Hempel Wikimedia Commons

Reconstruction Bryn Eryr Farmstead, St Fagans National History Museum, South Glamorgan, Wales

Photograph from M J Roscoe Wikimedia Commons

Reconstruction, West Stow Anglo-Saxon Village, Suffolk

Photograph from Midnightblueowl Wikimedia Commons

Now all I've got to do is stick about 800 years of development on what I can scrape out of the blender!

#MyrkMire#background research#background work#interactive fiction#hosted games#choice of games#interactive games

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

The circle of life

Some of us will say that life is a curse: that time is an illusion, that we must free ourselves from, and that we must move casuistically into the netherworld of being and nothingness, to see the true essence of the Here and Now, or the emptiness of existence (a kind of reciprocity). But this is - verily - the purest sound of being automatic and senseless.

The hoary old sages of the eternal time are venerable entities of systematic thought, that fool around in the majestic nature of exalted, edified nutrition and togetherness, that has no bearing on the cantankerous vicinity of ferocious cunning that provides only temporal releases from the buildings of architectural simplicity that goes nowhere; so, in fact, the building-blocks of artificial synonymity are drawn back to the furrows of therapeutic attenuation that sees no brilliance in the kept majorities of democratic synonymity, which is now the hope of the governmental statesmanships that point indiscriminately towards the variety of deconstructive analyses that make the man who builds his house on the rock in fact realize his manifold attenuations to the happy virility of dependant captainships in the structure of play and verisimilitude. Wisely, then, our initial thought of "love" then is reduced through a magical act to the chemistry of solidary acquirements in the purpose of magisterial seigneuriality against the hopefulness of detrimental causes and virile acquirements against the visibility of visual examinations that corrupt the status quo. In this totality, buildings of rarified enunciation are opportuned to the viscerality of tentamount normalcy that gives us a brink of seriousness in the bellicose nonsense of synonymic arrests that we have found in the brilliance of correct usage of terms in the examinatoric revelations that send us, impossibly, to the borderline of acquaintance and research.

Kierkegaard described Hegel as having built a vast mansion of thought, but occupying just a tiny kitchenette in the back himself. Arguably, then, the filial piety of these vehement Buddhists that have conveyed a post-colonial revolution to the builders of the new world will certainly not encounter structural tendencies in the brilliance of visual tendentiality in the wilderness of kinetic feeling and amorous divisions in the grave tendrils of the cosmic unity. Therefore, I will say that the family is certainly a complete home in the constructive sense, but only a factory or workshop in the operative sense. So normal accounts of the future are in fact symbolic; and the geography of terrorism is frankly countered in the schizo-religious amateurism of the present moment, which is just a military, Anglo-Saxon Protestant work ethique, that forever sends us spiraling towards criticism, practicals and contrasts. In summary, life is a fight, but gentility is possible, and moreover, a pastime.

#deconstruction#confucius#yi jing#filial piety#kierkegaard#hegel#buddhism#postcolonialism#homi bhabha#wasp#derrida#deleuze

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

40, 43, 44

40. favourite memory

one time I was in Wells Cathedral. I was with a group of artists on a tour of sacred/mythical sites in southern England, visiting places like Stonehenge and Glastonbury Tor and so on. Wells, I was told, is a pretty old sacred site: the eponymous wells have been the site of worship for as long as people have lived on the island of Great Britain, first nebulously pagan, then Roman, then Anglo-Saxon, and finally Christian. (note: I dunno if this is true, but it's important emotional context.) the cathedral is huge, and like all gothic churches, it's full of light and full of dead people. there are corpses in the floors and in the walls and on the grounds. and again, it sits on an ancient site with a long history of worship.

it was late afternoon in late October. magic hour. light coming in horizontally through the stained glass and all. the cathedral interior is all cream-colored stone, and there are windows everywhere, so the walls were practically glowing. and the actual architecture is a little bizarre and disorienting: it has this famous crisscrossing double arch in the nave that makes part of the building look as if it's turning into its own reflection. I was separated from my group after walking all over the grounds for most of the day and taking a rest in the lady chapel. the cathedral had been swarming with people the entire time, mostly tourists, some worshipers, staff/priests, etc. but right then the sanctuary emptied out. I was, essentially, alone in this gigantic old building, which despite its age is still only a blip in the history of this place. and I had the strangest sensation that it was alive. I felt seen by it. I felt the presence of time in a way I never have before or since. it was a sensation like horror without the fear. of being in the presence of something so large and alien that fear didn't apply, because fear is the body's danger warning system, but it couldn't process this as danger. it made me dizzy. still makes me dizzy to recall it. I don't know how long I was there. I don't remember how or when I got out.

it was the closest thing to a religious experience I have probably ever had. when I walked back outside, I apparently looked shaken enough for someone to ask me what was wrong. tried to explain to them, couldn't really. still not sure I can. it's one of the few things that's ever happened to me that I can't joke about. not because it was good or bad but because it was so…much. it's been five years and that moment takes up so much space in my head.

.if I go back, I will not be surprised to meet myself still sitting there.

43. favourite song ever

uhhhhhh let's say "Run Away With Me"

44. age you get mistaken for

when I was 19, 30-something. now that I am 30-something, people have stopped guessing

#asks#sorry if you've heard the cathedral story before; it just has to come out every now and then or it gives me vertigo

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

What was Anglo-Saxon architecture like?

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Worldbuilding: By the Foot

An interesting tidbit for you; cultures as far apart as Anglo-Saxon England and Joseon Dynasty Korea have measures for a foot, an inch, and a stride.

If you think about this it makes sense. People base their measurements first and foremost on people, and what’s useful to people. Since we’re all members of H. sapiens sapiens (we think), we have approximately the same stride, forearm length, hand-span, etc. And the same basic mental architecture that finds it easiest to visually divide things into halves, thirds, quarters, and twelfths, instead of, say, fifths and thirteenths. A sentient starfish with five-armed radial symmetry would likely have a completely different set of measurements and easy mental divisions. Not to mention a very different concept of the distance covered by one foot. (Hundreds and hundreds of tiny feet to an arm. Eep.)

So how do your characters measure their world, and their problems? Like a lot of things, part of it will rely on their culture, and part on individual experiences. One hungry tiger to an unarmed ginseng-hunter is a Problem. To a man who’s a member of a Mongol khan’s hunting brigade, working together with dozens and even thousands of other hunters and soldiers, it’s more of a dangerous opportunity. The weaver who counts yards in a day works on a different scale from the ship captain who covers 200 miles. And the ruler of an intergalactic empire might misplace a planet or two due to rounding errors.

(Might. If he suspected he had, he ought to just go ask the tax assessors. They’d probably track it down by lunchtime, complete with an itemized list of all taxable goods shipped to or from its spaceports and another list of where they suspect the planet’s fraudulently reporting. Problem solved.)

So what do all these measurements mean for your story?

If you’re writing from a human(ish) perspective, you can probably get away with using the measures you find handy in everyday life. Maybe dress them up a bit; a half-hand instead of two inches, a leap instead of a yard. But you can write your world without paying too much attention to how things are measured, and let your reader default to their standard assumptions.

If you’re writing from an inhuman perspective, though, you may need to think about this. A dragon might think in terms of claws, wingspans, bites. A dryad looks human-shaped, but depending on the lore she might be part of a whole forest that lives or dies on a centuries-long scale. And the great kraken that rises from the deep to doom mortal sailors should think in terms that drive your mind-mage to scream of the lightless depths and endless cold hunger.

Brr, who left the fridge open....

Measurements are part of how we make sense of the world. Know how your characters do it!

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Just as moments spent inside the chamber of a Neolithic tomb seem to occur in a place adrift from the modern, so that crypt belongs to a world that is otherwise beyond our reach”.

Neil Oliver.

(This is the second in my two-part series; please see here for the first).

Repton Abbey was founded in the 7th century and was launched into the religion and politics of Anglo-Saxon Mercia, whose capital was at nearby Tamworth. Monks and nuns lived together in this abbey, whose earliest recorded abbess was Saint Werburgh, daughter of Wulfhere, King of Mercia.

The crypt was laid down soon afterwards, which John Betjeman called “holy air encased in stone”. Buried here are King Aethelbald of Mercia (d. 757), King Wiglaf of Mercia (d. 839) and Wiglaf’s grandson, Saint Wystan (d. 840).

Murdered by his cousin, Wystan became famed for the healing poer of his relics, though his protection did not stop the Great Heathen Army of Vikings sacking Repton in 873-4, billeting themselves here in the winter and destroying the abbey, except the crypt.

(Modern science has backed up the historians; a mass grave of mostly men is believed after radiocardbon testing to be Viking warriors and their followers, and the Repton Stone, found in 1979, is believed to be Aethelbald. I saw the Repton Stone at Derby Museum and it was one of the factors that mde me come here).

The Vikings drove King Burgred into exile in 874 and ruled this part of Mercia until 937, when Athelstan forged the first united state of England, joining Mercia with its neighbours (which it had fought against, tuled, been ruled by and lived in an uneasy peace with, before coming together in one English state) and beating the Vikings and their allies.

After this Repton became more obscure, far from political power and with the bishops based in Lichfield; after the Normans conquered England from the Anglo-Saxons in 1066, they recorded Repton in the Domesday Book of 1086, but not as a major town.

Although the Anglo-Saxons had rebuilt the abbey after 874, little remained by the 12th century, so Maud of Glouceser built Repton Priory in its stead in 1172 and a medieval town grew up around it and the church, dedicated to the martyred Wystan. Most of the church you see in this shoot, apart from the crypt which is earlier, is from that time.

The priory thrived quietly until 1536, when Henry VIII forcibly changed England’s religion from the Catholic faith, which it had followed since before Wystan, to the new Protestantism. The church became what it is now, an Anglican parish church, and on the site of the abbey Repton School, which also still exists, was founded on money left by John Port of Etwall on his death in 1557.

Repton did not become a major industrial town (please see my earlier post for more) and so became a quiet town focused on church, school, and gradually the suburbs of Derby.

Arthur Blomfield oversaw a restoration in 1885-86 in the Gothic Revival style; the goths were never happier than when finding a true medieval survival to work on, and what you now see is thanks to their respectful building on what they found.

In the graveyard are Repton men such as the headmaster Henry Robert Huckin (1841-82) and CB Fry, described as “ Cricketer, scholar, athlete, Author – The Ultimate All-rounder”.

The church and school spirit of service and self-sacrifice made itself known in good times and in bad, the worst being the two world wars we remember today (please see here for more); the war memorials tell of the 255 dead of World War 1 and the 188 of World War 2.

The crypt had been boarded and floored over for hundreds of years and, though found in 1779 was not fully appreciated until it was restored in 1998 and this has brought back to us what we see today.

Described by Nikolaus Pevsner as "one of the most precious survivals of Anglo-Saxon architecture in England", this capped an otherwise boring drive home from my brother’s home in another Mercian town, Bedford, and it will be a fixture of my journeys from now on.

5 notes

·

View notes