#americus georgia

Text

StoryCorps: Leesburg Stockade Girls Recall Time As Civil Rights-Era Prisoners : NPR

Taken in 2016, (left to right) Emmarene Kaigler-Streeter, Carol Barner-Seay, Shirley Green-Reese and Diane Bowens stand outside the stockade building in Leesburg, Ga., where they were jailed in 1963.

The day Martin Luther King Jr. gave his landmark "I Have a Dream" speech in August 1963, a lesser known moment in civil rights history was unfolding in southern Georgia.

More than a dozen African-American girls, ages 12 to 15, were being held in a small, Civil War-era stockade set up by law enforcement in Leesburg, Ga., as a makeshift jail.

Though they were never charged with a crime, the girls had been arrested for challenging segregation in demonstrations in nearby Americus, Ga. For about two months, the girls slept on concrete floors; there was no working toilet or shower. There were minimal food and water deliveries each day.

"The place was worse than filthy," recalled Carol Barner-Seay at StoryCorps in 2016.

Barner-Seay, who's now 68, had been imprisoned there along with Shirley Green-Reese, Diane Bowens and Emmarene Kaigler-Streeter. At StoryCorps, the four women recounted their time together in the stockade.

"Being in a place like that, I didn't feel like we was human," Shirley Green-Reese, now 70, said.

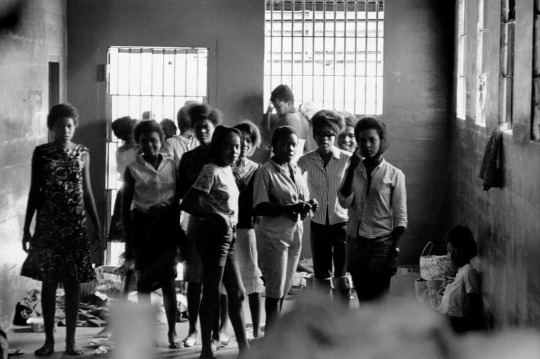

In August 1963, African-American girls were held in a Georgia stockade after being arrested for demonstrating segregation. Left to right: Melinda Jones Williams (13), Laura Ruff Saunders (13), Mattie Crittenden Reese, Pearl Brown, Carol Barner Seay (12), Annie Ragin Laster (14), Willie Smith Davis (15), Shirley Green (14), and Billie Jo Thornton Allen (13). Sitting on the floor: Verna Hollis (15).

Bowens, who's 68, was especially concerned about one of the girls, Verna Hollis. "I was scared Verna was going to die. If she ate, it would just come right back up."

Hollis didn't know that she was pregnant at the time. "We didn't know because we were children," Green-Reese said.

Looking back, Barner-Seay remembered Hollis' strength. "If she complained to anybody, it was under her breath to God, but we never heard it," she said.

Hollis' son, Joseph Jones III, is now 54 years old. A year before Hollis died in 2017, she recorded a StoryCorps interview with him, reflecting on those months she'd been jailed as a teen.

"I was scared and mad that you could treat a human being like they treated us," said Hollis, then 68. "We both could have died in there."

Jones told his mom he, too, was inspired by her strength. "I'm proud of that, and I try to live from that," he said.

'This is us'

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee eventually learned where the girls were and sent photographer Danny Lyon to the stockade to photograph them. When Lyon's photographs documenting their squalid living conditions were published, the girls were released.

When Green-Reese went back home, she says she didn't feel welcomed. "When we got out of that stockade, my classmates and my teachers never asked me where I was coming from," she said. "I felt like I didn't fit in, so after high school, I left the area and moved forward."

She took a job with a library in Savannah, Ga. In the archives at work one day, she saw for the first time one of Lyon's photos of the imprisoned girls, including herself, behind bars at the stockade.

"I said, 'This is us.' "

But Green-Reese didn't share the photo with her coworkers. "I didn't want them to know I was in that jail," she said.

It wasn't until 2015 that the women who had been imprisoned in the stockade got together to discuss their time there.

Bowens says she doesn't do well in confined spaces. "Today, when I got in this elevator, I was about to have a heart attack," she said in 2016. "I just don't want to be closed in, and I don't want to be in the dark."

In the StoryCorps podcast, Emmarene Kaigler-Streeter shared what she'd tell the men who locked her up: that she feels sorry for them. "Because they were not looking at us as children," she said. "They were not looking in the hearts. All they were looking at was the fact that we were black."

Green-Reese says the experience is in her "fibers."

"And I still don't like to talk about it," she said, "but this is a part of all of our lives forever."

#They Were Jailed In Squalor For Protesting Segregation#leesburg stockade#civil rights activists#Black Lives Matter#Black History Matters#georgia#americus georgia#systemic racism#falsely detained#adultification

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Navigating the Not-so-Peachy: The 21 Worst Cities to Live in Georgia, 2023"

Introduction

Life is a mosaic of decisions, with one of the most significant being the choice of where to call home. Our previous article illuminated the “Top 10 Best Cities to Live in Georgia, 2023,” but we understand that knowing where not to settle can be equally crucial. This inspired us to delve into the less illustrious side of Georgia’s cities, and in the spirit of comprehensive…

View On WordPress

#albany#Americus#bainbridge#Brunswick#College Park#Commute Times#Cordele#Cost of Living#Crime Rates#Cusseta#Dublin#education#Entertainment#Environmental Quality#forest park#georgia#Georgia Analysis#Georgia Challenges#georgia cities#Georgia City Comparison#Georgia City Data#Georgia City Grades#Georgia City Rankings#Georgia City Scores#Georgia Issues#Georgia living#Georgia Lows#Georgia Population#Georgia Problems.#Georgia rankings

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Campbell Chapel AME Church-Americus, Georgia

Designed by Louis H. Persley, the first Georgia-registered Black architect, the Romanesque Revival church was built in 1920. It is still an active congregation for the Americus community.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Danny Lyon Teenage Civil Rights Activists Imprisoned in the Leesburg Stockade for Trying to Desegregate a Theater in Americus, Georgia, Leesburg, GA 1963

74 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Americus, Georgia

built in 1910

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Flight of Four Mustangs Celebrates WWII Fighter Pilot’s 100th Birthday

March 20, 2024 Vintage Aviation News Warbirds News 0

The formation of four Mustangs flying over Lake Lanier, north of Atlanta.

United Fuel Cells

Mission accomplished! On Tuesday, March 19, World War II pilot Paul Crawford fulfilled his dream of flying in a P-51 Mustang like the one he commanded 79 years ago in China, where he flew 29 missions until he was shot down in 1945. Now 100, Buckhead resident Crawford was delighted when the Liberty Foundation and Inspire Aviation Foundation took him up in a TF-51D on a perfect blue-sky day for flying.

TF-51 “E Pluribus Unum” piloted by owner Bob Bull with Paul Crawford in the back leads the formation over Lake Lanier. The camera ship was a Bonanza piloted by long time Liberty Foundation’s pilot Cullen Underwood.

For the occasion, four P-51 Mustangs landed at the Dekalb-Peachtree Airport and parked at Atlantic Aviation, the FBO that supported this unique event. Mr. Crawford lovingly touched the nose and wing of one of the Mustangs when he first walked up to it, reuniting after a 79-year separation. LtCol Ray Fowler, Liberty Foundation Chief Pilot, and pilot Bob Bull helped Crawford into the back seat of the TF-51 and gave him an exhilarating 30-minute ride.

The organizers envisioned the participation of only one P-51, but a quick round of calls sparked the interest of other owners who enthusiastically decided to participate in the event. Bob Bull, Steve Maher, and Rodney Allison flew their Mustangs to Atlanta bringing the total number to four:

P-51D “Old Crow” (N451MG) – Pilot Ray Fowler – Liberty Foundation P-51D “Rebel” (N3BB) – Pilot Rodney Allison P-51 “E Pluribus Unum” (N351B) – Pilot Bob Bull – P-51 “Ain’t Missbehavin” (N51K) – Pilot Steve Maher

The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and Paul graduated six months later, during which time Congress passed the law to draft 18-year-olds. “I knew that I was going to be drafted so I went to Atlanta to talk with the Army Air Corps [sic] and the Navy about flying,” shared Mr. Crawford. ”The Navy said they would accept me for flight training but wanted me to go right then to their Great Lakes training center. The Air Corps told me they would accept me, but to go on back to college and they would notify me when to report.” said Crawford. Paul went back to Americus, entered Georgia Southwestern College, and shortly thereafter he received his draft notice to report to Fort McPherson in Atlanta on January 2, 1942.

Paul Crawford in his P-51 ‘Little Rebel’ ( photo by Paul Crawford Collection)

Paul had an older brother, Tim, who had gone into the Air Corps before Pearl Harbor and was flying B-26s, a medium bomber. He ended up flying combat in the B-17 Flying Fortress out of North Africa. The older brother influenced Paul’s choice, convincing him that the Air Corps had better aircraft, “I thought the water was, as they say, too deep and too wide to swim!” said Mr. Crawford.

With about 100 hours on the P-51 and 250-275 hours total, Mr. Crawford was sent off to Chengtu, China assigned to the 311th Fighter Group, 529th Fighter Squadron protecting the B-29 bases. As these B-29s transferred to the Pacific Theater, his squadron was transferred to Hsian headed for combat. At the time, Mr. Crawford was estimated to have only accumulated another 60 hours of flying time.

On his 29th mission, Mr. Crawford was shot down by ground fire while strafing a small railroad facility. After getting hit, he bailed out and was picked up by Chinese Communist guerillas. A few days earlier one of his housemates had been shot down and captured by the Japanese who cut his head off and put it up on a gate post. After a 200-mile-long walk, chased by the Japanese a couple of times, yet still evading capture, Mr. Crawford ended up at a compound owned by a wealthy family. A few miles from the compound was an airstrip where the OSS (U.S. Office of Strategic Services) brought downed airmen out. After the flight, Mr. Crawford talked about his experience: “When I recall my time in World War II, I always start by saying, I was not a hero! I was just there! That is not false modesty because it is the way I have always felt. I flew the P-51 Mustang.”

Mr. Crawford who has time in P-40, P-47, A-24, and P-51C, believes that the P-51 was the best fighter plane of its day. “There’s nothing in the world like that airplane,” Crawford said. “I loved doing the maneuvers again.” Paul Crawford was surrounded by several friends, his son-in-law, Tommy, and dozens of Liberty Foundation and Inspire Aviation Foundation members eager to have their pictures taken with him, shake his hand, and thank him for his service.

Ezoic

After serving in WWII, Paul Crawford finished college at Georgia Tech with a degree in Industrial Management. That’s also where he met his wife, Jean. They had a daughter and were married for sixty-one years when Jean passed away. Paul worked in the paper industry and for the U.S. Envelope Company until he retired in 1988. Paul currently lives in Atlanta and participates in aviation and historical WWII events.

This special event was made possible thanks to the support of Bob Bull, Ray Fowler Chief Pilot of The Liberty Foundation, Steve Maher, Atlantic Aviation FBO, Cullen Underwood with Vintage Flights, and Inspire Aviation Foundation.

Paul Crawford after the successful flight with (L to R), Cullen Underwood (Camera ship pilot), Bob Bull, Ray Fowler, and Rodney Allison.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

・。 [ madison bailey . cis woman . she && her ] - [ theodora ‘theo’ castor ] was blasting [ noah by noah cyrus ] on the sidewalk in austin today . according to other atx residents , the [ twenty five ] year old [ journalist ] has been given a reputation of being [ - sensitive ] , but also [ + honest ] . [ a camera that hangs around her neck almost always, the smell of the ocean and being outside, a free spirit searching for belonging ]

tw ;; childhood death

name: theodora "theo" castor

age: 25 years old

sexuality: pansexual

hometown: americus, georgia

career: photojournalist

+dedicated, honest, friendly, free-spirited, spontaneous

-stubborn, tempestuous, sarcastic, impulsive, fiery

adopted at a young age by a couple who seemingly have everything together, theo grew up in a middle class household. a fairly normal upbringing, she had a few other foster siblings who she grew incredibly close to.

her youngest brother, marcus, passed away when theo was fifteen and it shaped the way she saw the world. seeing it as an unfair place, she lost a piece of innocence and peace that she'd once had.

knowing that life was unfairly short, she knew that she wanted to take a gap year to travel before devoting herself to college pursuits.

traveling lit a fire inside of her and she knew she wanted to do it for the rest of her life. photography had always been a passion and she decided to turn her gap year into several years of travel while selling her photographs to magazines over the years.

now, she's settled in austin whilst earning a degree from the university of texas in photojournalism.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

It would be easy to drive right by the Lee County Stockade. The decrepit white concrete building sits in the shadow of a school bus depot and looks like the kind of place that long ago outlived its purpose. On a breezy, overcast day in mid-January, Shirley Green Reese, dressed in a white pantsuit and silver accessories, stood at the stockade door, directing a stream of reporters, filmmakers and locals to step inside.

She began describing the early morning hours of July 1963 when she and a wagonload of at least 14 other girls ranging in age from 12 to 15 were dropped at the jail more than 20 miles from their homes. They had been arrested just a day earlier during a nonviolent civil rights protest at a movie theater in Americus. Holed up in the stockade for weeks, they waited and wondered if their efforts would have an impact.

“I feel very honored that we can share the story and that some people are excited about it and are accepting of it,” Reese said. “Some can’t believe it happened in 1963, and some still have questions about it.”

Known as the Girls of Leesburg Stockade, their story has been shared by news outlets and in books, films and lectures for the past several decades, but to most Americans, including many residents in the southwest Georgia counties where the events took place, the women are largely unknown. They had joined the movement to be seen as Americans with the full force of civil rights, and like many other young protesters of the era, the details of their stories were subsumed by the larger narrative of the civil rights movement.

Caption

Caption

In 2015 Reese and the nine living Leesburg women collectively broke their silence about the time they spent in the Leesburg Stockade.

Now their memories have worn thin. Some of the women recall details that the others do not, and there are disputes about who was actually jailed in the stockade and for how long. But what the girls from Leesburg Stockade now collectively possess that they did not in the past is the desire for their efforts to be seen, heard and understood.

The stockade is now owned by the local school district. There is talk of preserving the building as a historic landmark. Last year, students at the high school worked to have the girls of Leesburg recognized on a historical marker. The marker, in partnership with the Georgia Historical Society, will be dedicated later this year to commemorate the spirit and sacrifice the girls showed during the summer of 1963.

The young seek a role

The road to the Leesburg Stockade began miles away and years before the girls were locked up.

A nascent civil rights effort had been brewing in that pocket of southwest Georgia as the 1950s gave way to the turbulent ’60s. It centered around Albany, and by 1962 had made its way to Americus, 38 miles north.

Children were encouraged to be part of the movement, as they had been in Albany and in Birmingham. It was a controversial tactic, but one that became a signature of the resistance. If a town could lock up its black children to avoid integration, what would it do to their parents?

“Around April of ’63 is when we started asking the SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) workers, ‘When are we going to go and test these places and restaurants to serve us?’” said Sam Mahone, one of the early leaders of the Americus-Sumter County Movement. “At first, SNCC didn’t think Americus was ready, but the students didn’t want to wait.”

After a series of mass meetings were held at local black churches to energize the crowds, direct action protests began. The first target was the town’s segregated movie theater.

Having slipped away from home on a Saturday afternoon while her parents were downtown, Reese and her best friend Mae Smith-Davis decided to attend the mass meeting at Friendship Baptist Church. When they arrived, the group was already planning to go to Martin Theater.

The pastor and SNCC workers gave them instructions. Don’t talk to anybody. Follow everyone closely. They joined the line and marched toward downtown.

Law enforcement in Americus responded with brute force: water hoses, cattle prods, nightsticks. They arrested protesters by the scores. Some were adults, but the overwhelming number of those taken into custody were teenagers, some as young as 12. When the city jail filled, surrounding counties offered space. Boys and girls were separated, although they were often held in the same building.

‘No swinging doors in Leesburg’

As the protests continued, the stockade in Leesburg filled with girls.

Paddywagons brought them to the stockade, a remote, low-slung structure surrounded by woods and bordered on one side by a lonely stretch of country road.

The building was by then a relic, gloomy and filthy. Bars covered the windows, but much of the glass was broken, giving easy access to bugs. The stockade’s sole toilet would not flush. There was no soap. Water from the shower head trickled in a thin stream. Day in and day out, the girls were fed either scrambled egg sandwiches or four rare hamburgers a day.

Some of the girls were ill and afraid.

Lulu Westbrook Griffin, 69, had joined the group of protesters at the church knowing she would likely end up in jail, but she wasn’t prepared for the trauma she would feel.

“We weren’t used to going off and staying overnight anywhere,” said Griffin, who was 12 at the time. “We went to church, to school. We didn’t even walk out of the house without our parents’ permission.”

Though she was in the company of other girls, Griffin said the experience left her with bouts of crying and nightmares that would persist well into adulthood. She had joined the movement to feel empowered, but her one act of protest left her feeling weak.

Diane Bowens’ activism had been brewing long before she attended the protest at the theater. By then, she was fully invested in the movement. In the stockade, her commitment didn’t waver, said Bowens, then 13. “If you were going to be a part of it, you were going to be a part of it,” she said. “There were no swinging doors in Leesburg.”

Outside world takes notice

As the days turned into weeks, other girls arrived, a signal to the ones already there that the protests continued back in Americus, 27 miles north. But here, the story of the girls of Leesburg Stockade gets muddled. Some reports have said there were more than 30 girls at the stockade arriving and leaving between mid-July and mid-September, but the only visual evidence of girls being held in the stockade, an image shot by a SNCC photographer, pictures 15 girls. Some girls, those from wealthier families in town, have said their parents paid a fee and got them out before the others.

SNCC kept tabs on what counties the children were taken to and where they were being kept, but they didn’t always have names for every child, especially if the child gave a false name. Which is what Carolyn DeLoatch did.

DeLoatch, then 15, had begged her parents to let her get involved in the movement and they’d relented, telling her she could go to mass meetings but to not intentionally get arrested. But there DeLoatch was in August, locked up.

Their days in the stockade were filled with talking, sleeping, praying, singing and wondering when they’d go home, DeLoatch, now 70, said. The monotony was about as intolerable as the food. But by being in Leesburg, she felt she was doing something important.

“It was bearable because it was all of us together,” DeLoatch said. “We were all demonstrating and we wanted people to know that we wanted to be free.”

After several days, her father paid a fine, possibly $45, she said, and she was brought back to Americus. Her father told her he was proud of her, she said, but within three days, her parents shipped her off to a South Carolina boarding school for black girls.

>> RELATED | More historical markers in Georgia, along with more scrutiny

Reese was still in the stockade when Danny Lyon, a young white photographer for SNCC, showed up. Though their parents had come to look in on them and pass fresh clothing and food through the bars, they didn’t have the means or influence to get them out. “Nobody had any rights. Who were they going to go to?” said Reese.

It was mid-to-late August and the girls pressed their faces against the bars staring at Lyon and stretching their arms through the panes framed with broken glass. He lifted his Nikon and started shooting. “I remember touching them through the bars and we said ‘Freedom’ — that was a code word for the civil rights movement,” Lyon said. “The fact that someone from the outside world was there was incredible to them.”

His visit lasted less than 15 minutes, he thinks, but it resulted in the only known images of the girls and the conditions in which they were being held. Not long after the pictures appeared in the black press, the girls were released. It would be the last time for several decades many of them would acknowledge their connection to the Leesburg Stockade.

Readjusting to their lives

On their return to Americus, the girls were dropped right back into their lives.

“I just remember being happy to get out of there,” Bowens said. Though her arrival home was celebrated, Bowens grappled with her feelings. Her mom pressed to know if anyone had sexually assaulted the girls. Her brother threatened to hurt anyone who had, though no one did.

“I just closed off that part of my life,” said Bowens, 69, who would go outside and sit under the house for hours crying. “Just knowing that someone would treat you like that and do that to you. I was feeling sad. I felt like, Is this it? Is this all there is to life?”

As they journeyed from teens to young women, many of the Leesburg girls’ worlds spread beyond the confines of southwest Georgia to New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and beyond. The 15 girls captured in Lyon’s now famous photo would go on to become pastors, civil servants, educators, authors and public speakers.

When Bowens met her husband, she began to feel better. He had been in the movement as well, and they would talk about all the things that happened in Americus. Raising her four children and building a long career as an inspector in the automotive industry changed her outlook, but Bowens still feels sad sometimes. “Things are better now, but basically things are still the same,” she said.

School had been in session for weeks when Reese walked into Sumter High after her release from the stockade. “Not even the teachers asked where I was coming from,” Reese said. “My grades started falling.”

Reese began diving into extracurricular activities — choir, dance, basketball — to keep her mind off those weeks during the summer. “When I first got out, I didn’t feel whole,” she said. She fed off the energy of close friends who were talented, had a positive attitude and were accepting of her.

After high school, her mother sent her to Savannah to live with her aunts. Reese enrolled in Savannah State University and embarked on an educational journey — ultimately earning a doctorate in philosophy from Florida State University — that would bring her some measure of solace and success. She went on to become the first black female athletic director in the state of Georgia.

“I pushed the stockade out of my mind because I had to get an education. That is what my parents had pushed all our lives,” she said.

Though she spent less time in the stockade, DeLoatch was nonetheless marked by the experience. For her, it was an “awakening.” Before Leesburg, she was sheltered by her educator parents, her father a school principal and her mother a librarian in Americus’ segregated school system. They were part of the town’s tiny black middle class.

Leesburg and the Americus movement taught DeLoatch that civil rights would only come with a sustained fight. She went from being voted “most civic minded” at her boarding school to later participating in the Poor People’s Campaign while a college student at Virginia Union in Richmond, she said. Eventually she became a city planner in Chicago and the mother of two. She watched with pride as her son decided to register to vote as soon as he turned 18: no literacy test to pass; no poll tax to pay.

“There was no problem,” DeLoatch said.

Making their voices heard

Leesburg was a moment in DeLoatch’s life but not the only important one.

“I moved on but I used that to help me become the person I am: the kind of person who doesn’t let anybody push them around; the kind of person who is secure in my personhood,” she said.

But the impacts of childhood trauma can linger, said Vincent Willis, assistant professor of interdisciplinary studies at the University of Alabama. Willis is writing the book “Audacious Agitation,” on the experiences of student protesters in southwest Georgia during the civil rights movement. He’s including a chapter on the larger Americus movement and has interviewed some of the women who were jailed in the stockade as girls, he said.

“That 14-year-old girl is still in there somewhere,” Willis said. “The idea that time heals all wounds, I argue against it. They’re told to get over it, that the battle was won, but there are always lingering effects. There’s always psychological damage.”

Griffin was first among the girls of Leesburg Stockade to share her story on a national platform. In 1996, she saw a book, “Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement,” with the photographs Lyon had taken at the stockade. “The pictures had no names. I thought, wow, I need to put a name to these faces,” said Griffin, a retired educator.

She would later write a book and hold speaking engagements at schools. When she began planning a documentary, which premiered in Americus in 2003, she contacted some of the other women, she said. Some of them were still reluctant to speak out about the past, fearing repercussion from locals. A few years later, in 2006, a reporter from Essence magazine wrote a story, and some of the women who had previously been reluctant began to speak out.

Reese returned to Americus for good in 2002. She got involved with local civic organizations, including the Boys and Girls Clubs of Americus-Sumter County and the City Council. “I felt I needed to get back in there and help the kids move forward so they would not have to go through what we went through,” Reese said. For years, she had suppressed her feelings about the stockade, but since returning to Americus, she has vowed to keep telling their story.

“We as a people don’t want to address something like this because they feel like things are better now. But we can’t let them forget the past,” Reese said. “Even if they don’t care, I care.”

#Leesburg Stockade Girls#Danny Lyon#americus georgia#civil rights activists#Black Lives Matter#american history#white supremacy#qualified immunity#badges of slavery

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This 1850 home in Americus, Georgia has so much to see. It’s built in the Louisiana French or "Creole" style, and it’s gorgeous. ($660k)

Isn’t this a beautiful big porch?

The interior is just stunning. That wall of books has a door in it, which isn’t something you see that often.

A 2nd sitting room is just as beautiful.

It has a lovely big formal dining room.

The kitchen is galley style, but it’s very long with lots of features. I think that’s a small sink for washing veggies, and it also has two large professional stoves.

This bedroom- look at the bookshelves. It even has a little library ladder.

Upstairs is this classy office.

And this fabulous bedroom.

Outside by the pool is a guest house.

The guest house is so pretty, too. It’s like a big open studio apt.

But, that’s not all- there’s also this guest house.

This one is even larger.

Then there are the tennis courts.

The property is magnificent- all 39.36 acres.

It’s really a stunning property that I would expect to cost over $1m.

https://www.zillow.com/homedetails/523-Us-Highway-19-S-Americus-GA-31719/105388147_zpid/

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

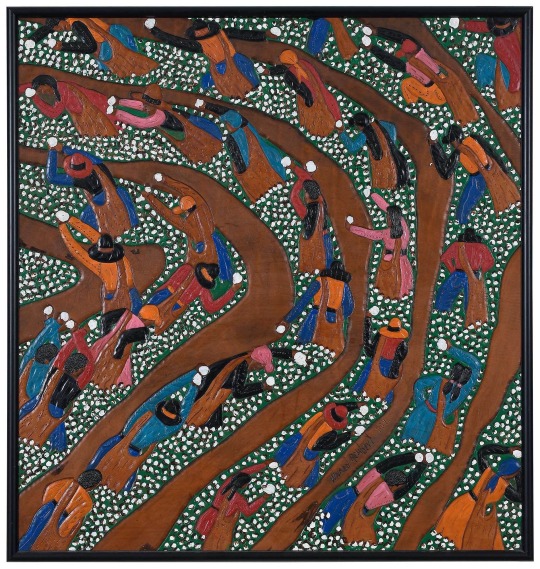

Winfred Rembert

(American/Georgia, 1945-2021)

dye on carved and tooled leather

Note:

Born in rural Georgia, raised in a community tied to the cotton fields, Winfred Rembert survived a childhood of poverty in the segregated South of the 1940s. He would go on to be a nationally recognized artist, and his biography - Chasing Me to My Grave: An Artist's Memoir of the Jim Crow South - was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 2022.

It was not a well paved path. In 1966, after a demonstration in Americus, Georgia, Rembert was arrested and put in jail without being charged. A year later, he escaped but was caught and hung up by a group of deputy sheriffs. They stuck him with a knife but did not kill and burn him as he had anticipated. He spent the next seven years in a chain gang. Remarkably, he met his wife while building roads and bridges in rural Georgia as part of his prison sentence. While in prison, a man named TJ taught him how to carve wallets out of leather, a skill that he would use decades later in his embossed leather paintings.

After his release, Rembert and Patsy married and they moved to New York, then Connecticut, where he worked a variety of jobs. Not until in his 50s after a second round in prison, did he begin to draw and paint the scenes of his youth, carving the stories into tactile leather canvases.

In 2000, Rembert had a well publicized show at the Yale University Art Gallery. In 2002, he was introduced to Peter Tillou after speaking about his artwork at a school in Waterbury, Connecticut. A short time later they agreed to a working relationship that included numerous exhibitions and his 2010 "coming out" show at Adelson Galleries in New York. His work has entered major museum and private collections.

Brunk Auctions

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bartow Cafe-Americus, Georgia

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Roland L Freeman Millard Fuller, His Wife and Children Harvesting Grapes on the Koinonia Farm. Near Americus, Georgia 1971

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Americus, Georgia

built in 1890

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

9:22 COMM YENSEY: It's almost 9:30 and you promised you'd have this done by noon.

9:22 TRM PIERS HALL: shit.

9:22 TRM PIERS HALL: watch this.

10:45 TRM PIERS HALL ATTACHED A FILE

Royal Georgia and the Zones of Safety [NYTF]

(a/n Sorry I don't have a better map, I haven't drawn one yet. I think this one does the trick)

Hello and welcome back!

I am Their Majesty, Monarch Piers Hall of the Royal State of Georgia, and I am glad to have you back for the next part of our (brief) series overviewing what the "Royal State of Georgia" is all about! In our last part, we briefly overviewed the Atlanta Zone of Safety, but today we zoom out to look at Royal Georgia as a larger whole.

Most of the boundaries of Royal Georgia are similar to pre-Fall Georgia, save for the little "tail" on the bottom being taken by Florida, and the upper right-hand corner being a sort of no-man's land passed between Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. Other that that, most of our present-day borders are the same as those in the past! Within the Royal State of Georgia, there are an assortment of Settlements and Zones. Today, we're going to briefly go over the various Zones within Georgia, although we may go over the 15 other Settlements later on.

What is and what makes a Zone?

Zones are the large settlements (not capital) within the State of Georgia. They receive direct military, financial, and political support from the state government, and get their own representative in the State Council. In order to become a Zone, Settlements (capital S) must apply to state-level government, and meet certain qualifications.

There are nine qualifications, and at least six must be met at all times for a Zone to become a Zone

Exist within the pre-Fall state borders (REQUIRED)

Have a population of at least 1 million people

Have constructed borders, like the Perimeter of ATLZoS, although this can just be a chain-link fence

Have a GDP of at least 40 billion RGD (Royal Georgia Dollar)

Have a GDP per capita of at least 40,000 RGD

Have a stable local government (any kind)

Have a food production capacity to support at least 80% of the Zone above starvation level without imports

Have access to a city-sustaining, freshwater source within 10 miles of the Zone (rivers or lakes)

Have a healthcare system capable of supporting the population (REQUIRED)

Zones of Royal Georgia

Atlanta

Acceptance Date: September 19th, 2097 (Founding)

Qualifications: 1,2,3,4,5,7,8,9

Councilor: David Rorric Johnson

Note: Atlanta is the largest and capital Zone. It used to have a City Council (local government) however it was never reelected after the Atlanta City Council bombing, with many Zone-level duties falling to the monarch instead. This is NOT considered a local government, though.

Macon

Acceptance Date: September 20th, 2097 (Founding)

Qualifications: 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 (Macon is the ONLY Zone that currently meets all qualifications)

Councilor: Fantasia Delta Mason

Government format: Commission

Presiding Commissioner: Jamir Caran Enyo

Savannah

Acceptance Date: September 20th, 2097 (Founding)

Qualifications: 1,2,4,5,6,8,9

Councilor: Shanna Blaire Miles

Government format: Mayor-Council

Mayor: James "Clay" Bunting

Athens

Acceptance Date: July 8th, 2118

Qualifications: 1,3,4,5,6,7,8,9

Councilor: Marlowe Silas Greyson Sidney

Government format: Dictatorship ("Chancellorship")

Chancellor: Silas Cosmo Argus Sidney

Albany

Acceptance Date: May 19th, 2122

Qualifications: 1,2,4,6,7,8,9

Councilor: Nyla Eliana Adel

Government format: Mayor

Mayor: Solenne Esme Santamaria

Note: Albany is not on that map but it's directly south of Americus

Valdosta

Acceptance Date: January 22nd, 2139

Qualifications: 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9

Councilor: Callum Tobias Meghan

Government format: Council-Manager

City Manager: Bryant Ryleigh Mellon

Rome

Acceptance Date: October 26th, 2178

Qualifications: 1,4,5,6,7,8,9

Councilor: Esther Amelia Green

Government format: Mayor-Council

Mayor: Liberty Maxima Redmond

Gainesville

Acceptance Date: Applied

Qualifications: 1,3,5,6,8,9

Councilor: N/A

Government format: Mayor-Council

Mayor: Vivianne Izabella Dubois-Carmen

Tag list (dm to be +/-):

@author-a-holmes @soul-write @flowerprose @ceph-the-ghost-writer @theglitchywriterboi @when-wax-wings-melt @thechaoticflowergarden @lyralit @penspiration-writing @samatedeansbroccoli @charlesjosephwrites @italiangothicwriteblr @thetruearchmagos @pineapple-lover-boy @unilightwrites @sanguine-arena @bardic-tales @joshuaorrizonte @blind-the-winds @circa-specturgia @hymnonlips @aloeverawrites @the-stray-storyteller @writeblrsupport @starlit-skys @kyuponstories @guessillcallitart @magic-is-something-we-create @talesofsorrowandofruin @writingonmymind @imslowlydisintegrating @worldsfromhoney

NYTF WIP PAGE

#writeblr#writing#worldbuilding#city building#athenswrites#wip#nytf#government making#atlzos#athzos#albzos#romzos#maczos#savzos#valzos#gavzos

6 notes

·

View notes