#Smithsonian NMAI

Text

For #Woodensday:

#Seal figure by Melvin Olanna, 1968

Inupiat Eskimo, Shishmaref, Alaska, USA

Yellow cedar wood, L 32 x W 18.5 x H 20.5 cm

25/6106 Indian Arts & Crafts Board Collection, DOI, at Smithsonian NMAI

#animals in art#museum visit#20th century art#1960s#woodwork#effigy#sculpture#carving#seal#indigenous art#native american art#First Nations art#Melvin Olanna#Smithsonian NMAI

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paige Pettibon (American, b. 1987), Soren Lake, 2021, acrylic on canvas, featured in the online exhibition Ancestors Know Who We Are.

Paige Pettibon is a Tacoma, Washington based multidisciplinary artist of Black, Salish, and white descent. Her artistic practice represents her diverse background and amplifies the voices of people in her community.

#paige pettibon#women artists#portraits#smithsonian#nmai#national museum of the american indian#contemporary artist

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Naa Kahídi (Clan House) Part of the “Preston Singletary: Raven and the Box of Daylight” exhibition at the #smithsonian #nmai Entryway was created with kiln-cast and sand-carved glass; water-jet cut, inlaid, and laminated medallion. Eight pieces of hand-made glass and metal bracketed together; I don’t even want to think how heavy each piece is. 😳 #museumofthenativeamericanindian #washingtondc #tingit #glassart #sonya7iii #lowlightphotography #prestonsingletaryglass #sonnartfe2835 #zeisslens (at National Museum of the American Indian) https://www.instagram.com/p/CoFYEUgLYMV/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#smithsonian#nmai#museumofthenativeamericanindian#washingtondc#tingit#glassart#sonya7iii#lowlightphotography#prestonsingletaryglass#sonnartfe2835#zeisslens

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

["Since the establishment of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in 1989 and the implementation of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in 1990, US museums involved in repatriation efforts have been grappling with the dilemma of sacred Indigenous objects and remains contaminated by toxic pesticides and preservatives."

.....For tribal members, this history can pose hazards. Those interested in incorporating previously held items such as repatriated regalia back into ceremonial practice worry that contaminated objects might endanger their health. For others seeking the reburial of ancestral remains, there are concerns that preservatives and pesticides could potentially poison the surrounding environment."]

Something the article doesn't talk about is how this is a major issue that plagues museums in general and is a health and safety hazard to museum workers. Paraphrasing my professor who said something like; "It's actually a good sign if you have to manage and fight off pests eating away at your natural history collections, because that means they aren't saturated with arsenic. Taxidermy is scary if it's in good condition."

Ensuring the safety of museum workers, the communities repatriated items belong to, and the environment are big issues. If you are getting an occupational/environmental health and safety degree and looking for a thesis topic, have I got some ideas for you....

258 notes

·

View notes

Text

Holy shit that was amazing!

"What If...Kahhori Reshaped the World?" is almost entirely in Mohawk (and Spanish).

Some good representation, Marvel!

They worked in close collaboration with members of the Mohawk Nation and the Smithsonian's NMAI!

My head is exploding with so many thoughts and feelings I can't organize them right now.

Like, so sorry about Asgard but the Tesseract giving its powers to the land and its people and literally changing the past 400-500 years of world history for the better?

Yes

Fucking yes

All of the yeses!

Now if you'll excuse me, I have to go research Mohawk culture:

"What kind of clay are you made of?"

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw

“THE HARBINGER OF CATASTROPHE” (DETAIL) BY MARIANNE NICOLSON, 2017. GLASS, WOOD, HALOGEN-BULB MECHANISM. COLLECTION OF THE ARTIST. JOSHUA VODA/NMAI, SMITHSONIAN

#kwakwakawakw#indigenous art#northwest coast native art#formline#marianne nicolson#native art#contemporary art#art#2010s#m

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Smithsonian Institution holds human remains from more than 30,000 individuals in its collections. Most of these holdings—including bones, teeth, tissues and about 250 brains—were acquired in the 19th and early 20th centuries under dubious circumstances.

The charge of correcting these historical injustices now falls to 21st-century stewards. This week, the Smithsonian published a report from its Human Remains Task Force, which offered recommendations regarding the future of these holdings.

“We are committed to being a leader in all respects, and that means addressing the wrongs of our past by taking steps to ethically return collections and humanely steward any human remains in our care,” says Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch III in a statement. “The work of repatriation began several decades ago, and we recognize that it requires a long-term commitment to complete. In recent months, we have made significant progress in this area.”

The long-anticipated report is the culmination of work conducted by the task force, which includes Smithsonian employees and outside experts, since its formation in April 2023. The group crafted Smithsonian-wide recommendations regarding the ethical return of human remains, which the Institution will ultimately use to create and implement new official policies. These changes will primarily affect the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH), where the majority of these holdings reside, and the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), which houses the rest.

The recommendations emphasize that consent is a vital prerequisite for using human remains in any capacity. Going forward, the report advises, the Smithsonian should not collect, display or use remains for research purposes without the informed consent of the deceased or their descendants.

The Smithsonian should also offer to return remains taken without consent to the descendants of those individuals; per the task force, “reasonable efforts” should be made to locate those descendants. If no descendants can be found, the remains should be offered to appropriate community representatives or organizations. In cases where no community can be determined, the Smithsonian should create a process for respectfully burying the remains.

Like many other cultural institutions around the world, the Smithsonian has grappled in recent years with mounting pressure to expedite efforts to repatriate human remains. Last summer, the Washington Post published an investigation into the Smithsonian’s holdings—particularly those collected under the watch of Aleš Hrdlička, the Institution’s first curator of physical anthropology. Hrdlička harbored ambitions of proving now-debunked theories of white superiority known today as scientific racism.

Days later, the Post published an op-ed by Bunch addressing the investigation. It ran under the headline “This is how the Smithsonian will reckon with our dark inheritance.” Bunch described Hrdlička’s legacy as “abhorrent and dehumanizing work [that was] carried out under the Smithsonian’s name.”

“As Secretary of the Smithsonian, I condemn these past actions and apologize for the pain caused by Hrdlička and others at the Institution who acted unethically in the name of science, regardless of the era in which their actions occurred,” Bunch wrote. “I recognize, too, that the Smithsonian is responsible both for the original work of Hrdlička and others who subscribed to his beliefs, and for the failure to return the remains he collected to descendant communities in the decades since.”

Bunch noted that the Smithsonian’s work to repatriate human remains goes back more than 30 years. Early efforts intensified after the 1989 passage of the National Museum of the American Indian Act, which requires the Smithsonian to inventory its Native American human remains and repatriate them upon request.

“To date, we have focused on the repatriation of Native American remains to comply with federal law,” Bunch wrote. “The Smithsonian established its Human Remains Task Force to develop an institutional policy that addresses the future of all human remains still held in our collections.”

The Smithsonian has repatriated the remains of more than 5,000 individuals to date, with many thousands of human remains still to be processed. In a December follow-up to its initial investigation, the Post published a report in which former Smithsonian employees spoke of facing internal resistance on repatriating remains during the 1990s. Other staff from that period acknowledged that the process, by necessity, takes time to ensure the proper descendants receive the remains. The Post also cited a 2011 government report that said “it could take several more decades to complete” repatriating all the human remains in the collections.

In the new report, the task force suggests expediting returns under the NMAI Act, adding that NMAI and NMNH “should proactively engage descendants and tribes rather than waiting for them to initiate requests.” Because nearly half of the human remains still held by the Smithsonian are not covered by the NMAI Act, the report also recommends creating a repatriation team at NMNH that’s not linked to the law.

The changes arrive amid similar repatriation efforts nationwide. In January, new federal regulations requiring museums to “obtain free, prior and informed consent” from tribal officials before putting certain Native American artifacts on view went into effect. (This rule is an update to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which does not apply to the Smithsonian, though the new report notes that the 1990 law “enshrined many of the same principles” as the NMAI Act.)

“Historic inequities facilitated the expropriation, curation and unconsented use of human bodies,” writes the task force. “This is our unfortunate inheritance. … As the Smithsonian moves forward, it should do so thoughtfully and as rapidly as possible without doing further harm to individuals, families or communities.”

#history#current events#racism#colonialism#eugenics#anthropology#museums#native americans#usa#aleš hrdlička#smithsonian institution

1 note

·

View note

Text

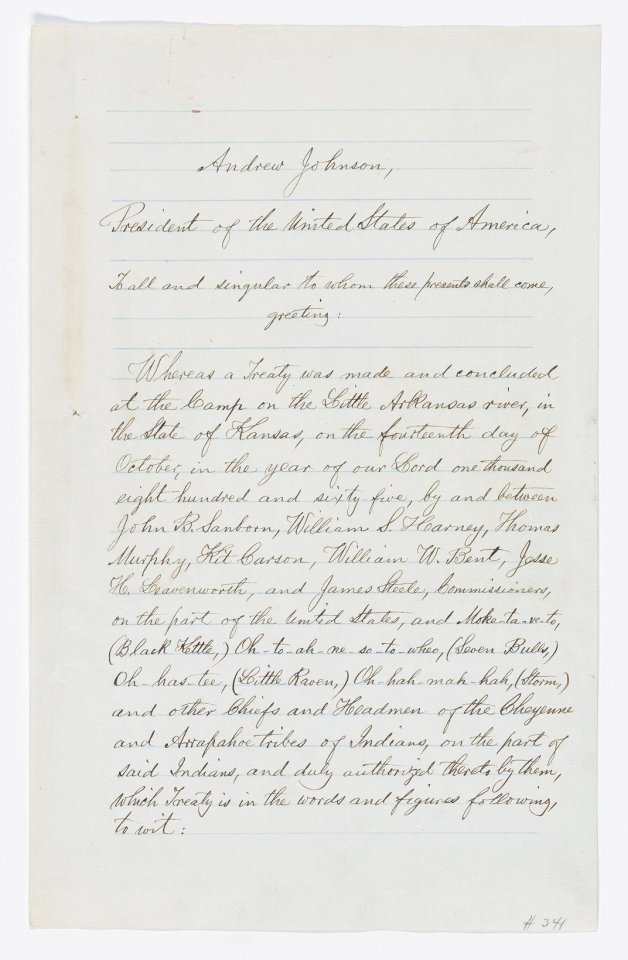

Was der Cheyenne-Arapaho-Vertrag von 1865 über die gebrochenen Versprechen der Vereinigten Staaten gegenüber den amerikanischen Ureinwohnern aussagt

Das wichtige Dokument ist jetzt im National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. zu sehen

Foto: Cheyenne und Arapaho Delegation, Camp Weld, 28. September 1864

"Vor 158 Jahren wurde dem Volk der südlichen Cheyenne und Arapaho an den Ufern des Arkansas River im Vertrag von Little Arkansas 1865 Wiedergutmachung für das Sand Creek Massaker versprochen. Die Regierung der Vereinigten Staaten hat ihre Verpflichtungen aus diesem Vertrag nicht erfüllt. Wir wurden aus dem Land des vorherigen Vertrags vertrieben und in das heutige Oklahoma umgesiedelt. Die Worte unserer Großeltern und Urgroßeltern bleiben für immer in unserem Bewusstsein. Wir dürfen nie vergessen, wer wir sind und warum wir hier sind. Bis heute erinnern wir die Regierung daran, dass sie für ihre Versprechen gegenüber unserem Volk verantwortlich ist." - Cheyenne und Arapaho Gouverneur Reggie Wassana

Die Anführer der Cheyenne und Arapaho sehen sich ihren Vertrag aus der Nähe an, bevor er in der Nation to Nation Gallery ausgestellt wird. NMAI Foto

Am 14. Oktober 1865 versammelten sich berühmte Persönlichkeiten, die Westernfans und Historikern bekannt sind, am Little Arkansas River im Bundesstaat Kansas, um einen historischen Vertrag auszuhandeln, der das Leben des Volkes der Cheyenne und Arapaho für immer verändern sollte. Mehrere Vertreter und Kommissare vertraten die Vereinigten Staaten. Unter ihnen waren Kit Carson, William W. Bent (zusammen mit seinem Bruder Charles, nach dem Bents Fort in Colorado benannt wurde) und Jesse H. Leavenworth (sein Vater Henry war der Namensgeber des Leavenworth-Gefängnisses). Die Cheyenne und Arapaho wurden von Cheyenne-Häuptling Black Kettle (Moke-ta-ve-to) und Arapaho-Häuptling Little Raven (Oh-has-tee) und anderen Häuptlingen vertreten.

Little Raven, Oberhäuptling der Arapaho. William S. Soule Photographs 1868 - 1875, National Archives, NAID: 518894

Dieser Vertrag wurde 11 Monate nach dem Massaker von Sand Creek am 29. November 1864 ausgehandelt, einem Tag, der im Leben der modernen Cheyenne und Arapaho für immer in Vergessenheit geraten ist. In Sand Creek griffen etwa 675 Freiwillige der US-Armee ein Lager der Cheyenne und Arapaho an, während diese die Flagge der Vereinigten Staaten hissten und damit signalisierten, dass sie in Frieden lebten. Mehr als 150 Männer, Frauen und Kinder der Cheyenne und Arapaho wurden ermordet. Als Vergeltung nahmen die Cheyenne und Arapaho anderer Stämme die Überfälle auf Siedler, die in ihr Gebiet eindrangen, wieder auf. Um diese Aufstände zu unterdrücken, schickten die USA Kommissare und andere offizielle Vertreter zum Little Arkansas River in der Nähe des heutigen Wichita, um einen Vertrag mit den Cheyenne und Arapaho auszuhandeln, der einen "ewigen Frieden" vorsah.

Alle anwesenden Häuptlinge unter der Führung von Black Kettle und Little Raven verurteilten die Soldaten und Freiwilligen, die ihr Volk am Sand Creek ermordet und verstümmelt hatten. Es wird berichtet, dass ein Häuptling der Cheyenne die Flagge der Vereinigten Staaten gut sichtbar über seiner Hütte hisste, während andere im Dorf weiße Fahnen schwenkten. Die sichtbaren Zeichen des Friedens ignorierend, wurde das Signal gegeben, das Feuer mit Gewehren und Kanonen zu eröffnen. Als die Körper ihrer Opfer leblos auf dem Boden lagen, brannten die Truppen das Dorf nieder, verstümmelten die Toten und trugen Körperteile als Trophäen davon. Der Cheyenne-Häuptling Black Kettle, der die Flagge der Vereinigten Staaten in Frieden gehisst hatte, überlebte das Massaker und trug seine schwer verwundete Frau vom Ort des Massakers nach Osten über die kalten Ebenen des Winters. Das Smithsonian Magazin hat ausführlichere Details über das Sand Creek Massaker berichtet, die du hier nachlesen kannst.

Die erste Seite des 29-seitigen handschriftlich ratifizierten Vertrags 341: Cheyenne und Arapaho - Little Arkansas River, Kansas, 14. Oktober 1865. National Archives Foto #183517077

Die Regierung der Vereinigten Staaten drückte Reue aus und verzichtete auf das Massaker am Sand Creek. Um Wiedergutmachung zu leisten, wurde 1865 ein neuer Vertrag zwischen den Cheyenne und Arapaho ausgehandelt, der Zahlungen für 40 Jahre, Entschädigung für gestohlenes und zerstörtes Eigentum, Landzuweisungen für diejenigen, die Angehörige verloren hatten, und ein Reservat an der Grenze zwischen Kansas und dem Territorium der Natives (dem heutigen Oklahoma) versprach. Dieser 1867 unterzeichnete Vertrag war voller gebrochener Versprechen. Kansas weigerte sich, das Reservat zuzulassen, Reparationen wurden nie geleistet und ein dauerhafter Frieden wurde nicht erreicht. Im Jahr 1868 wurde Häuptling Black Kettle getötet, als die Siebte Kavallerie von Oberstleutnant George A. Custer sein friedliches Lager am Washita River angriff. Heute hoffen die Nachfahren der Opfer des Sand Creek Massakers, dass die Vereinigten Staaten die Versprechen, die sie ihren Vorfahren gegeben haben, einhalten werden.

Lesen Sie den ganzen Artikel von Dennis Zotigh:

Unterrichtseinheit über Verträge der USA mit den Ureinwohnern

Read the full article

0 notes

Photo

On this day 15 years ago, the first National Powwow was held at the National Mall!

The National Powwows began in September 2002. They were organized by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in anticipation of the opening of the museum. The events were attended by thousands from the US and Canada to celebrate American Indian culture through dancing, music, food, clothing, and events. Hundreds of tribes participated in a dance competition at the powwow, where members of the tribe wore traditional clothing. Subsequent powwows were held in 2005 and 2007.

Learn more at Histories of the National Mall.

#national powwow#National Museum of the American Indian#Smithsonian NMAI#NMAI#american indian#washington dc#Washington DC History#National Mall#on the mall

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

National Museum of the American Indian... • • #nationalmuseumoftheamericanindian #nmai #americanindian #americanindianmuseum #americanindianhistory #americanindianculture #indigenous #nativeamericans #history #culture #historyandculture #respect #smithsonian #smithsonianmuseum #smithsonianinstitution #washington #washingtondc #nationallmall #iphonex #spectreapp #spectreshot #motionblur #timelapse #waterfall (at Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian) https://www.instagram.com/p/B26upI3BVUW/?igshid=894kr224xzgb

#nationalmuseumoftheamericanindian#nmai#americanindian#americanindianmuseum#americanindianhistory#americanindianculture#indigenous#nativeamericans#history#culture#historyandculture#respect#smithsonian#smithsonianmuseum#smithsonianinstitution#washington#washingtondc#nationallmall#iphonex#spectreapp#spectreshot#motionblur#timelapse#waterfall

1 note

·

View note

Photo

From #nativeamerican culture to #newyork #subculture ( well, #chinatown and #soho ) with #family and then #ues #dinner with #friends #friday #fridaynight #nyc #bigapple #frenchiesinthecity #brother #cousins #boys #tccannon #nmai #smithsonian #chinesefood #shopping #drinks #thewritingroom #thankful #happy #love https://www.instagram.com/p/B1jVkNXA7vR/?igshid=1xq1qhoomxdst

#nativeamerican#newyork#subculture#chinatown#soho#family#ues#dinner#friends#friday#fridaynight#nyc#bigapple#frenchiesinthecity#brother#cousins#boys#tccannon#nmai#smithsonian#chinesefood#shopping#drinks#thewritingroom#thankful#happy#love

1 note

·

View note

Text

#MetalMonday:

Rabbit Mask

Guerrero Nahua (Mexico)

1940-1960

Copper, cotton cloth, paint

26.5 x 18.2 cm

Smithsonian NMAI 24/5904

#animals in art#20th century art#museum visit#rabbit#mask#metalwork#Metal Monday#copper#Indigenous art#Mesoamerican art#Mexican art#Smithsonian NMAI

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Very briefly on the museums I went to

I first went to the National Museum of the American Indian. There were a lot of cool exhibits and it was clear that it's done with a lot of love, with cultural exhibits curated by members of the actual cultural group. In other words, an emic perspective rather than an etic. I don't recall which were permanent and which were special ones (I do know one of the exhibits was a special one, but that will get its own post since I have a lot of personal stake in that one) but I really enjoyed the "Our Universes" one that discussed ideologies and philosophies of different indigenous American cultures. There were also some cools ones about The Battle o Little Bighorn (and why it was so memorable), Matoaka (aka Pocahontas), and the Trail of Tears. While I was in the gift shop actually, they also had a live performance by one of the cultural curators doing different songs from different cultures. Really cool stuff.

The other museum I went to was the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. That is a beautifully designed and laid out museum. The flow is really good, the material was handled in a way that balanced being immersive, educational, and interactive with being respectful and not sugar-coating anything. I will say that my only negative is that I was expecting myself to be more emotionally ravaged than I was. But I firmly believe this wasn' the museum's fault. I was physically exhausted from my trip and I just kept comparing it to my experience at the Anne Frank Museum in Amsterdam. It's really difficult to top the way your heart gets put through the ringer there. That said though, I honestly believe that the USHMM is one of the best museums I have EVER been to and considering how I am with museums, that's really saying something. I sincerely recommend it to anyone and everyone.

#smithsonian#washington dc#united states holocaust memorial museum#ushmm#national museum of the american indian#nmai#boldly going somewhere

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The National Museum of the American Indian at the Smithsonian is a gorgeous building.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

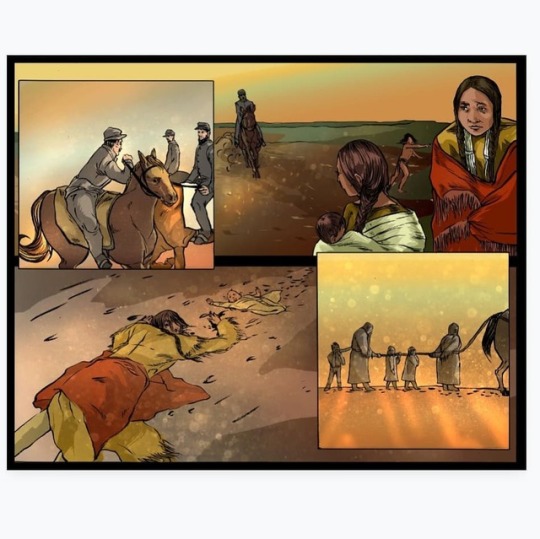

These are the completed pages for last year's project with the #smithsonian #museumoftheamericanindian #NMAI. They used these in their Nk360 online curriculum to teach historical events nationwide. Educators had access to a timeline with key historical events told in sequential art panels. I did everything from pencils, inks to full colors. #sequentialart #education #national #teachingaid #native #history #illustration #museum #curated #comicart

#smithsonian#curated#illustration#museum#museumoftheamericanindian#sequentialart#teachingaid#education#national#nmai#history#comicart#native

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Purepecha (Tarascan) gourd vessel, 1940s (Smithsonian NMAI)

14 notes

·

View notes