#Pausania

Text

Eugeni d'Ors ~ La valle di Josafat - 2. Figure dell'antichità classica

Eugeni d’Ors ~ La valle di Josafat – 2. Figure dell’antichità classica

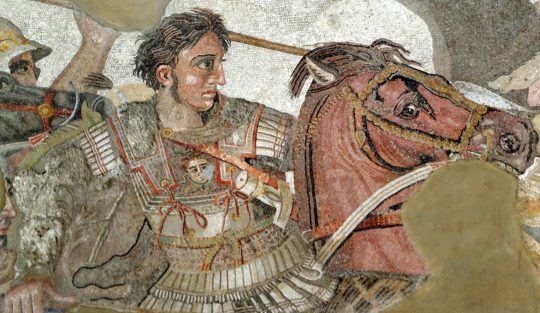

Alessandro Magno il Macedone

La coppa di sangue di bue che, volontariamente bevuta, mise termine alla feconda esistenza di Temistocle era la stessa che piena di cicuta, doveva bere Socrate più tardi. Alcuni mercanti la riportarono di nuovo ad Atene con il cadavere dell’eroe. (Lasciatemi inventare questa leggenda e credere in essa, come un greco, immediatamente dopo di averla…

View On WordPress

#Alessandro Magno#Aristide#Diogene Cinico#Eugenio d&039;Ors#Fabio Massimo#Fidia#Ippocrate di Chio#Lucano#Luciano di Samosata#Marziale#Parmenide#Pausania#Pirrone#Plotino#Plutarco#Publio Virgilio Marone#Seneca#Sesto Empirico#Sibilla di Forcia#Simeone Stilita#Talete#Temistocle#Teocrito#Tucidide#Zankara#Zenone di Elea

0 notes

Text

I love how Pausanias makes the Gauls sound mythical when he lived in a time when Gauls were part of the empire

"The Gauls live in the remotest region of Europe, on the coast of an enormous tidal sea which no ship can cross; it has sea monsters in it nothing like the other monsters of the sea. Across that country runs the river Eridanos, where people believe the daughters of the Sun are lamenting the tragedy of their brother Phaiton."

Pausanias those are your fellow subjects you live in the Roman empire what Are you talking about

145 notes

·

View notes

Photo

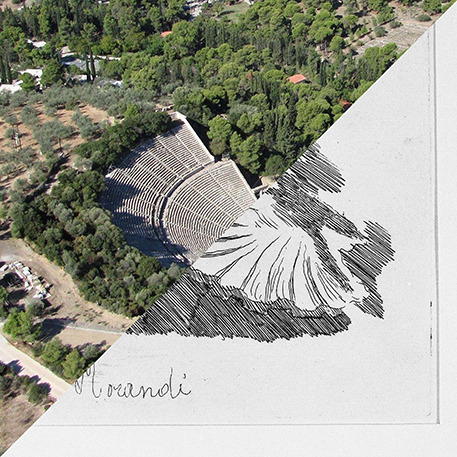

Spitallamm dam, Grimselsee, Switzerland, 1932

VS

Ancient Theatre, Epidaurus, Greece, 4th century BC

#Spitallamm#Grimselsee#dam#Arch dams#Hydropower#barrage#architecture#engineering#Epidaurus#greece#ancient greece#theatre#ancient theatre#Polykleitos the Younger#Pausanias#argolis#archaeology#greek archaeology#landscape architecture#Asclepius#World Heritage Site#UNESCO

941 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think it's so funny how in the symposium you have Alcibiades and Socrates having that whole drama about Agathon while Pausanias is just. Sitting there.

#they had a very secure relationship or something#Pausanias doesn't need to throw a hissy fit he knows who Agathon belongs to at the end of the day#good for them

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Venus Pandemos by Marc Charles Gabriel Gleyre 1852

"Aphrodite Pandemos (Ancient Greek: Πάνδημος, romanized: Pándēmos; "common to all the people") occurs as an epithet of the Greek Goddess Aphrodite. This epithet can be interpreted in different ways. In Plato's Symposium, Pausanias of Athens describes Aphrodite Pandemos as the Goddess of sensual pleasures, in opposition to Aphrodite Urania, or "the heavenly Aphrodite". At Elis, she was represented as riding on a ram by Scopas. Another interpretation is that of Aphrodite uniting all the inhabitants of a country into one social or political body. In this respect she was worshipped at Athens along with Peitho (persuasion), and her worship was said to have been instituted by Theseus at the time when he united the scattered townships into one great body of citizens. According to some authorities, it was Solon who erected the sanctuary of Aphrodite Pandemos, either because her image stood in the agora, or because the hetairai had to pay the costs of its erection. The worship of Aphrodite Pandemos also occurs at Megalopolis in Arcadia, and at Thebes. A festival in honour of her is mentioned by Athenaeus. The sacrifices offered to her consisted of white goats. Pandemos occurs also as a surname of Eros. According to Harpocration, who quotes Apollodorus, Aphrodite Pandemos has very old origins, "the title Pandemos was given to the Goddess established in the neighborhood of the Old Agora because all the Demos (people) gathered there of old in their assemblies which they called agorai." To honour Aphrodite's and Peitho's role in the unification of Attica, the Aphrodisia festival was organized annually on the fourth of the month of Hekatombaion (the fourth day of each month was the sacred day of Aphrodite). The Synoikia that honoured Athena, the protectress of Theseus and main patron of Athens, also took place in the month of Hekatombaion."

From Plato's Symposium:

"Such in the main was Phaedrus' speech as reported to me. It was followed by several others, which my friend could not recollect at all clearly; so he passed them over and related that of Pausanias, which ran as follows: "I do not consider, Phaedrus, our plan of speaking a good one, if the rule is simply that we are to make eulogies of Love. If Love were only one, it would be right; but, you see, he is not one, and this being the case, it would be more correct to have it previously announced what sort we ought to praise. Now this defect I will endeavor to amend, and will first decide on a Love who deserves our praise, and then will praise him in terms worthy of his Godhead. We are all aware that there is no Aphrodite or Love-passion without a Love. True, if that Goddess were one, then Love would be one: but since there are two of her, there must needs be two Loves also. Does anyone doubt that she is double? Surely there is the elder, of no mother born, but daughter of Heaven, whence we name her Heavenly; while the younger was the child of Zeus and Dione, and her we call Popular. It follows then that of the two Loves also the one ought to be called Popular, as fellow-worker with the one of those Goddesses, and the other Heavenly. All Gods, of course, ought to be praised: but none the less I must try to describe the faculties of each of these two. For of every action it may be observed that as acted by itself it is neither noble nor base. For instance, in our conduct at this moment, whether we drink or sing or converse, none of these things is noble in itself; each only turns out to be such in the doing, as the manner of doing it may be. For when the doing of it is noble and right, the thing itself becomes noble; when wrong, it becomes base. So also it is with loving, and Love is not in every case noble or worthy of celebration, but only when he impels us to love in a noble manner.

“Now the Love that belongs to the Popular Aphrodite is in very truth popular and does his work at haphazard: this is the Love we see in the meaner sort of men; who, in the first place, love women as well as boys; secondly, where they love, they are set on the body more than the soul; and thirdly, they choose the most witless people they can find, since they look merely to the accomplishment and care not if the manner be noble or no. Hence they find themselves doing everything at haphazard, good or its opposite, without distinction: for this Love proceeds from the Goddess who is far the younger of the two, and who in her origin partakes of both female and male. But the other Love springs from the Heavenly Goddess who, firstly, partakes not of the female but only of the male; and secondly, is the elder, untinged with wantonness: wherefore those who are inspired by this Love betake them to the male, in fondness for what has the robuster nature and a larger share of mind. Even in the passion for boys you may note the way of those who are under the single incitement of this Love: they love boys only when they begin to acquire some mind—a growth associated with that of down on their chins. For I conceive that those who begin to love them at this age are prepared to be always with them and share all with them as long as life shall last: they will not take advantage of a boy's green thoughtlessness to deceive him and make a mock of him by running straight off to another. Against this love of boys a law should have been enacted, to prevent the sad waste of attentions paid to an object so uncertain: for who can tell where a boy will end at last, vicious or virtuous in body and soul? Good men, however, voluntarily make this law for themselves, and it is a rule which those ‘popular’ lovers ought to be forced to obey, just as we force them, so far as we can, to refrain from loving our freeborn women. These are the persons responsible for the scandal which prompts some to say it is a shame to gratify one's lover: such are the cases they have in view, for they observe all their reckless and wrongful doings; and surely, whatsoever is done in an orderly and lawful manner can never justly bring reproach.

“Further, it is easy to note the rule with regard to love in other cities: there it is laid down in simple terms, while ours here is complicated. For in Elis and Boeotia and where there is no skill in speech they have simply an ordinance that it is seemly to gratify lovers, and no one whether young or old will call it shameful, in order, I suppose, to save themselves the trouble of trying what speech can do to persuade the youths; for they have no ability for speaking. But in Ionia and many other regions where they live under foreign sway, it is counted a disgrace. Foreigners hold this thing, and all training in philosophy and sports, to be disgraceful, because of their despotic government; since, I presume, it is not to the interest of their princes to have lofty notions engendered in their subjects, or any strong friendships and communions; all of which Love is pre-eminently apt to create. It is a lesson that our despots learnt by experience; for Aristogeiton's love and Harmodius's friendship grew to be so steadfast that it wrecked their power. Thus where it was held a disgrace to gratify one's lover, the tradition is due to the evil ways of those who made such a law— that is, to the encroachments of the rulers and to the cowardice of the ruled. But where it was accepted as honorable without any reserve, this was due to a sluggishness of mind in the law-makers. In our city we have far better regulations, which, as I said, are not so easily grasped."

-taken from wikipedia and Plato's Symposium 180c-182d

#aphrodite#venus#cupid#pagan#paganism#european art#literature#history#paintings#plato#pausanias#ancient greece#Marc Charles Gabriel Gleyre

172 notes

·

View notes

Note

You already wrote it like twice lol so I apologize for bringing it up again… but if you were to rewrite the final scene of Rise once more but from Philippos’s POV… what would you envision his final thoughts to have been when he’s killed? Or, I'm not sure if he would have even been capable of having any by that point, but, for imagination's sake really :)

Below are my thoughts about Philippos’s mindset at the time.

Before I get to that, for anyone wondering what the asker is talking about, my website for Dancing with the Lion has several “out-takes” (scenes cut from the novels), plus a few scenes (and one short story) that take place in the c. 10 months between book 1 and book 2.

Among these is a rewrite of Rise's last scene, originally done in Alexandros’s head, seen from Hephaistion’s POV. (Click image)

(Fair warning, and it probably goes without saying, but while the first set can be read after finishing Becoming, the second set should wait until you’ve finished Rise, as they naturally contain spoilers.)

So, first, at the parade’s start, Philippos would still be irked with Alexandros after their quarrel over (ironically) Pausanias. He said they’d continue the discussion later, after telling Alexandros his choices were about managing difficult personalities, especially when they’re about to be away from Macedon for some years.

Ergo, at the start of the parade, he would’ve been thinking about how to get through to his idealistic child that sometimes full justice must take a back seat to avoiding interminable blood feuds. He’d probably also have been hoping he’d live until Alexandros was more mature. He’d not be thinking assassination, of course. They’re about to embark on a serious military campaign to Persia, and Macedonian kings often died with their boots on. He’s in his mid/late 40s, his leg is lame and he’s not as fast as he used to be. He could fall in battle.

This isn’t overly morbid. These are pretty normal thoughts (ime) for parents of teens, and Alexandros is still, effectively, a teen, even if he just turned 20. You just hope the inevitable blunders of adolescence are none so bad they die before the neurons in their frontal cortexes finish fusing. Not that the Greeks understood adolescent neurology, but they certainly understood teenaged hotheadedness. And Alexandros (and the real Alexander) were more hotheaded than most. After all, how many times did his own bravery almost get him killed?

So that would’ve been on Philippos’s mind in the immediate aftermath of their quarrel, but it wouldn’t be the first time—I’m sure it was a well-worn grove of worry—so he’d have kicked it off once the parade started. After that, right up until the moment he was stabbed, he was having a great morning. It was truly his triumph. That’s the irony of his death … and why Pausanias picked that event.

Historically speaking, it seems he was stabbed in the back, or perhaps from the side, so I doubt he saw it coming—or who stabbed him. Now, we get into a bit of speculation and back to my fictional take. I wrote it so that he died almost immediately. Pausanias was a soldier, and even with a cloak in the way, he could find the heart fairly accurately, I think. (Whether this was true in history, we don’t actually know. The historical Philip may have taken a few minutes to die if Pausanias was off target by an inch or two.)

In any case, the heart is delicate. A direct wound by arrow, sword, spear, knife, bullet is almost always fatal without immediate medical intervention, due to extreme bleeding into the chest cavity. Ergo, shock takes over in under half a minute, more like 15-20 seconds.

In the novel, in those, let’s say, 20 seconds, Philippos was able to call his son’s name, and would have seen Alexandros turn and call him Pappa, reaching for him. The surprise on his son’s face would tell Philippos he wasn’t involved. Philippos would know he was a dead man, so I think it would matter to him that Alexandros wasn’t behind it.

I don’t say in the novel, but Pausanias could have whispered something in his ear at the end. I describe him as right behind the king, one hand on his elbow. Alexandros thinks he’s helping to hold his father up (not realizing the other hand had the knife). And, again, as a soldier, Pausanias would have twisted that knife, once it went in, to be sure, even if he’d hit off center, that it would do maximum damage. Then, of course, he’s off like a shot, shoving Philippos at Alexandros.

Philippos was probably still conscious enough to feel his son grab him and hear him shout, “Get him!” But after that, shock would’ve kicked in and he’d have lost consciousness. He’d look dead to Alexandros (and be as good as).

In reality, the brain still survives for a few minutes even after the heart stops. He’d no doubt have had the “life flashes before your eyes” experience. He might have felt fury at Pausanias, but largely, I think, for interrupting his plans. I suspect his main concern would be the safety of his son and of his kingdom. At the approach of death, things pare down to the most basic and most important. I doubt that included Pausanias except peripherally (probably to Pausanias’s dismay, if he knew).

So that’s my take on what Philippos probably thought at the end.

#asks#Philip of Macedon#assassination of Philip of Macedon#Dancing with the Lion#DwtL#Alexander the Great#historical fiction#ancient Macedonia#Pausanias

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

hmmm..............

#pausanias in arkansas what will he describe#thoughts#<- it's bc they have greek names that are in pausanias & the map is confused but. akjhsdfkjsadf

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

18 pages of functionally creative writing for a class that was not about creative writing prefaced by an apology and concluded with another apology* I am foolish like nothing and untouchable like god

#*and a thank you! for a fun semester#but i really do feel a constant urge to apologize Dr if you’re seeing this………… sorry………………..#hope you have fun with my ocs. old butch lesbian who has not realized she’s into women and two guys with feelings for each other flirting#through email. and Fake Pausanias as well

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

GUYS, DID YOU KNOW THAT THERE IS ONE TIME ARTEMIS REJECTED A GUY WITHOUT KILLING HIM???

According to Pausanias' Description of Greece, a river god named Alpheus fell in love with Artemis. And Artemis knows this. Instead of giving him the "scorpion sting" or "devoured by your dogs" treatment, she decided to prank him.

Artemis hosts a party for her nymph friends, and when Alpheus sneaks in to abduct her, Artemis covers her and her friends' faces with mud. Alpheus gets confused and can't find the real Artemis, so he just leaves ALL IN ONE PIECE (maybe except for a broken heart).

See, Artemis isn't always vengeful against men.

Source if you're interested.

#artemis#alpheus#greek mythology#greek goddesses#greek deity#description of greece#pausanias#things i found on Theoi.com

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

daily Whistlepaw until gr becomes PoV day 1064

I am having So Much Fun with my assignments

#warrior cats#windclan#medicine cat apprentice#whistlepaw#Babygirl. Pausanias. What the fuck do you mean to say in that first line?#Οικοδόμημα ες παρασκευήν εστί των πόντων#Yeah buddy what does That mean?#Is that οικοδόμημα nominative or accusative? What is going on here#You arrived in the city. I know. But Then? House is to the preparation of the processions that (...)#The joys of Greek#And I'm not allowed to look shit up#I'll already have to tell my teacher I had to look up a few words#So yay!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

my favourite thing about doing a dissertation is how you go insane for a year about something that almost no one knows about and then when you talk about it everyone just goes "huh, cool."

#pausanias' irreparable distortion of our archaeological interpretations of ancient corinth my beloved#dissertation posting

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not going to comment on George O'Conner's series on the Olympians as a whole because I'm really not the target audience and I'm sure it's fine enough for what it is supposed to be (and also I have only read Hera's book lol), but I must say, the idea that what distinguishes Hera from previous partners of Zeus is the fact that she is not only his queen, as others also supposedly were, but also his wife,, as others supposedly were not, that somehow being the queen of the gods is more commonplace than being a wife of Zeus, is absolutely bizarre and I don't understand this choice at all.

If anything, it is the other way around. While it is true that only with Hera does Zeus seem to have a proper wedding (in regular Greek mythology at least, though Pindar mentions a wedding of Zeus that could just as well be with Themis), multiple goddesses (ex: Leto in the Homeric epics, Metis in Hesiod's Theogony, Themis in Pindar) and even mortal women (ex: Io in the Prometheus Bound), can on occasion be called wife of Zeus. However, Hera alone of all these women is given titles such as queen of the gods (θεῶν βασιλέα) in Pindar's Nemean 1, queen of the Olympians (βασιλειαν Ολύμπιον) in Pindar's Paean 21 and the Phoroneus, queen of the imortals (ἀθανάτην βασίλειαν) in Homeric Hymn 12, greatest queen (μεγιστοάνασσα) in Bacchylides' Ode 19, legitimate queen of Olympos (κρείουσα γνησίη Οὐλύμποιο) in Kallimachos' Hymn to Delos, homothronos (sharing the same throne) with Zeus in Pindar's Nemean 11, first enthroned bride of Zeus (Διός πρωτόθρονε νύμφη) in Nonnos' Dionysiaca, Hera who has the foremost throne in Kolouthos' The Rape of Helen, etc. The thing is that most goddesses - Aphrodite, Athena, Artemis, Demeter, etc - can occasionally be called queen in literature, but Hera has this as a cult title as well, and it is used predominantly for her.

#and her reparthenosification was hardly a story only women knew#we do know of it from Pausanias after all#ramblings#hera#zeus#greek mythology

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

part of why Pausanias feels so conversational is because he just stops in the middle of describing a temple and tells the reader he's stopping because it came to him in a dream that he should shut up about it. You're looking through a little window into the far past and suddenly the author's hand reaches in front of you to close the curtain.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Theatre, Epidaurus, Greece, 4th century BC

VS

Giorgio Morandi, Shell and other objects, 1948

#giorgio morandi#italian art#modern art#Etchings#etching#still life#epidaurus#greece#ancient greece#archaeology#greek archaeology#pausanias#Peloponnese#Argolis#asclepius#unesco#world heritage site#landscape architecture#world heritage#architeture#polykleitos the younger

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

A clarification on Athenian Laws concerning male homosexuality.

(because this particular small thing is often misunderstood, due to inability to accurately translate specific ancient greek terms into english, or lack of comprehension of context.)

In classical athens, there was a very specific set of laws, concerning ONLY male athenian citizens (so slaves, women and metics were not subject to it). These laws said that a male athenian citizen who engages in intercourse with another man IN EXCHANGE FOR PAYMENT, was not allowed to do certain things, such as hold positions of power or speak in the assembly. There were also potential penalties (not described in detail) for the person hiring an athenian citizen for this purpose. Again, this is often misunderstood, so I have to repeat, this was only when it was done in exchange for some sort of payment/recompense. The word used for these men is of the same root as εταιρα, which was the female counterpart. It is often mistranslated, there's a whole thing I could go on explaining about the different types of prostitution terms, but basically there was a distinction between prostitute and courtesan/escort/whatever you'd call them in english.

Also, this law did not forbid this, and it was not a prosecutable offense by itself. The offense was if one such man disobeyed the limitations set by the law, and it's unclear to me what the deal was with the person who paid.

SO yeh. Next time someone says there were laws against homosexuality in classical athens, here's a helpful article of a guy explaining this much better than me, and goes into more detail about all the weird intricacies of the legal system, as well as the laws set in place to protect boys from grown men:

and here's our original source about these laws:

#tagamemnon#ancient greece#this isn't my field of expertise so if i've misunderstood anything let me know#but this is why I recommend going as close to the original sources as possible#always#because it would've been easy for someone to mistranslate this one term#and someone who doesn't know the context of the entire text#might read that and think all bottoms lost their rights in classical athens or something#which would make no sense because alcibiades was publicly called a bottom in plays which would mean that ppl knew it#(or the joke wouldn't work i think)#but he held the highest possible position for a short while after his recall to athens#also to anyone who says these relationships were only for adult men and teen boys#pausanias and agathon were lover-beloved when they were both grown adults#agathon is around thirty in the symposium#and they even left athens together at the end of their lives#ANYWAYS UR WELCOME HAVE A NICE DAY

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

why do classics courses in uni make you read like. ‘canonical’ classical texts for one thousand years and not even mention the wild shit in e.g. pausanias this is so fun why did i have to read the res gestae so many times

#/J I KNOW WHY ALSO I KNOW I COULD HAVE JUST READ PAUSANIAS MYSELF BACK THEN! but i didn’t! because of lucan#howeverrrrrrr every time i’ve just read a bit of like. pliny or pausanias or ATHENAEUS? the deipnosophistae is fun you guys i promise#it has been fun! would have loved to do a module on this stuff! absolutely do not have the time to sit down and read all of any of them#though!!!#also rip i read the entire res gestae ever night for like a month before my augustan history exam#because the lecturer said it was a fun way to revise it. as a Joke but i did do it.#it did not help! i had weird res gestae dreams and barely remember any of it and then did the essay question on the aeneid.#anyway. pausanias fun. i’m enjoying it#beeps

38 notes

·

View notes