#pausanias

Text

I love how Pausanias makes the Gauls sound mythical when he lived in a time when Gauls were part of the empire

"The Gauls live in the remotest region of Europe, on the coast of an enormous tidal sea which no ship can cross; it has sea monsters in it nothing like the other monsters of the sea. Across that country runs the river Eridanos, where people believe the daughters of the Sun are lamenting the tragedy of their brother Phaiton."

Pausanias those are your fellow subjects you live in the Roman empire what Are you talking about

145 notes

·

View notes

Photo

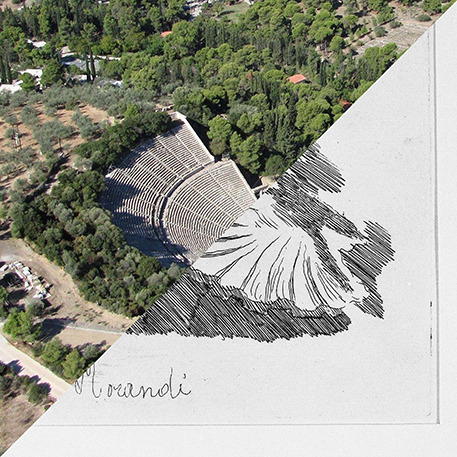

Spitallamm dam, Grimselsee, Switzerland, 1932

VS

Ancient Theatre, Epidaurus, Greece, 4th century BC

#Spitallamm#Grimselsee#dam#Arch dams#Hydropower#barrage#architecture#engineering#Epidaurus#greece#ancient greece#theatre#ancient theatre#Polykleitos the Younger#Pausanias#argolis#archaeology#greek archaeology#landscape architecture#Asclepius#World Heritage Site#UNESCO

940 notes

·

View notes

Note

You already wrote it like twice lol so I apologize for bringing it up again… but if you were to rewrite the final scene of Rise once more but from Philippos’s POV… what would you envision his final thoughts to have been when he’s killed? Or, I'm not sure if he would have even been capable of having any by that point, but, for imagination's sake really :)

Below are my thoughts about Philippos’s mindset at the time.

Before I get to that, for anyone wondering what the asker is talking about, my website for Dancing with the Lion has several “out-takes” (scenes cut from the novels), plus a few scenes (and one short story) that take place in the c. 10 months between book 1 and book 2.

Among these is a rewrite of Rise's last scene, originally done in Alexandros’s head, seen from Hephaistion’s POV. (Click image)

(Fair warning, and it probably goes without saying, but while the first set can be read after finishing Becoming, the second set should wait until you’ve finished Rise, as they naturally contain spoilers.)

So, first, at the parade’s start, Philippos would still be irked with Alexandros after their quarrel over (ironically) Pausanias. He said they’d continue the discussion later, after telling Alexandros his choices were about managing difficult personalities, especially when they’re about to be away from Macedon for some years.

Ergo, at the start of the parade, he would’ve been thinking about how to get through to his idealistic child that sometimes full justice must take a back seat to avoiding interminable blood feuds. He’d probably also have been hoping he’d live until Alexandros was more mature. He’d not be thinking assassination, of course. They’re about to embark on a serious military campaign to Persia, and Macedonian kings often died with their boots on. He’s in his mid/late 40s, his leg is lame and he’s not as fast as he used to be. He could fall in battle.

This isn’t overly morbid. These are pretty normal thoughts (ime) for parents of teens, and Alexandros is still, effectively, a teen, even if he just turned 20. You just hope the inevitable blunders of adolescence are none so bad they die before the neurons in their frontal cortexes finish fusing. Not that the Greeks understood adolescent neurology, but they certainly understood teenaged hotheadedness. And Alexandros (and the real Alexander) were more hotheaded than most. After all, how many times did his own bravery almost get him killed?

So that would’ve been on Philippos’s mind in the immediate aftermath of their quarrel, but it wouldn’t be the first time—I’m sure it was a well-worn grove of worry—so he’d have kicked it off once the parade started. After that, right up until the moment he was stabbed, he was having a great morning. It was truly his triumph. That’s the irony of his death … and why Pausanias picked that event.

Historically speaking, it seems he was stabbed in the back, or perhaps from the side, so I doubt he saw it coming—or who stabbed him. Now, we get into a bit of speculation and back to my fictional take. I wrote it so that he died almost immediately. Pausanias was a soldier, and even with a cloak in the way, he could find the heart fairly accurately, I think. (Whether this was true in history, we don’t actually know. The historical Philip may have taken a few minutes to die if Pausanias was off target by an inch or two.)

In any case, the heart is delicate. A direct wound by arrow, sword, spear, knife, bullet is almost always fatal without immediate medical intervention, due to extreme bleeding into the chest cavity. Ergo, shock takes over in under half a minute, more like 15-20 seconds.

In the novel, in those, let’s say, 20 seconds, Philippos was able to call his son’s name, and would have seen Alexandros turn and call him Pappa, reaching for him. The surprise on his son’s face would tell Philippos he wasn’t involved. Philippos would know he was a dead man, so I think it would matter to him that Alexandros wasn’t behind it.

I don’t say in the novel, but Pausanias could have whispered something in his ear at the end. I describe him as right behind the king, one hand on his elbow. Alexandros thinks he’s helping to hold his father up (not realizing the other hand had the knife). And, again, as a soldier, Pausanias would have twisted that knife, once it went in, to be sure, even if he’d hit off center, that it would do maximum damage. Then, of course, he’s off like a shot, shoving Philippos at Alexandros.

Philippos was probably still conscious enough to feel his son grab him and hear him shout, “Get him!” But after that, shock would’ve kicked in and he’d have lost consciousness. He’d look dead to Alexandros (and be as good as).

In reality, the brain still survives for a few minutes even after the heart stops. He’d no doubt have had the “life flashes before your eyes” experience. He might have felt fury at Pausanias, but largely, I think, for interrupting his plans. I suspect his main concern would be the safety of his son and of his kingdom. At the approach of death, things pare down to the most basic and most important. I doubt that included Pausanias except peripherally (probably to Pausanias’s dismay, if he knew).

So that’s my take on what Philippos probably thought at the end.

#asks#Philip of Macedon#assassination of Philip of Macedon#Dancing with the Lion#DwtL#Alexander the Great#historical fiction#ancient Macedonia#Pausanias

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Venus Pandemos by Marc Charles Gabriel Gleyre 1852

"Aphrodite Pandemos (Ancient Greek: Πάνδημος, romanized: Pándēmos; "common to all the people") occurs as an epithet of the Greek Goddess Aphrodite. This epithet can be interpreted in different ways. In Plato's Symposium, Pausanias of Athens describes Aphrodite Pandemos as the Goddess of sensual pleasures, in opposition to Aphrodite Urania, or "the heavenly Aphrodite". At Elis, she was represented as riding on a ram by Scopas. Another interpretation is that of Aphrodite uniting all the inhabitants of a country into one social or political body. In this respect she was worshipped at Athens along with Peitho (persuasion), and her worship was said to have been instituted by Theseus at the time when he united the scattered townships into one great body of citizens. According to some authorities, it was Solon who erected the sanctuary of Aphrodite Pandemos, either because her image stood in the agora, or because the hetairai had to pay the costs of its erection. The worship of Aphrodite Pandemos also occurs at Megalopolis in Arcadia, and at Thebes. A festival in honour of her is mentioned by Athenaeus. The sacrifices offered to her consisted of white goats. Pandemos occurs also as a surname of Eros. According to Harpocration, who quotes Apollodorus, Aphrodite Pandemos has very old origins, "the title Pandemos was given to the Goddess established in the neighborhood of the Old Agora because all the Demos (people) gathered there of old in their assemblies which they called agorai." To honour Aphrodite's and Peitho's role in the unification of Attica, the Aphrodisia festival was organized annually on the fourth of the month of Hekatombaion (the fourth day of each month was the sacred day of Aphrodite). The Synoikia that honoured Athena, the protectress of Theseus and main patron of Athens, also took place in the month of Hekatombaion."

From Plato's Symposium:

"Such in the main was Phaedrus' speech as reported to me. It was followed by several others, which my friend could not recollect at all clearly; so he passed them over and related that of Pausanias, which ran as follows: "I do not consider, Phaedrus, our plan of speaking a good one, if the rule is simply that we are to make eulogies of Love. If Love were only one, it would be right; but, you see, he is not one, and this being the case, it would be more correct to have it previously announced what sort we ought to praise. Now this defect I will endeavor to amend, and will first decide on a Love who deserves our praise, and then will praise him in terms worthy of his Godhead. We are all aware that there is no Aphrodite or Love-passion without a Love. True, if that Goddess were one, then Love would be one: but since there are two of her, there must needs be two Loves also. Does anyone doubt that she is double? Surely there is the elder, of no mother born, but daughter of Heaven, whence we name her Heavenly; while the younger was the child of Zeus and Dione, and her we call Popular. It follows then that of the two Loves also the one ought to be called Popular, as fellow-worker with the one of those Goddesses, and the other Heavenly. All Gods, of course, ought to be praised: but none the less I must try to describe the faculties of each of these two. For of every action it may be observed that as acted by itself it is neither noble nor base. For instance, in our conduct at this moment, whether we drink or sing or converse, none of these things is noble in itself; each only turns out to be such in the doing, as the manner of doing it may be. For when the doing of it is noble and right, the thing itself becomes noble; when wrong, it becomes base. So also it is with loving, and Love is not in every case noble or worthy of celebration, but only when he impels us to love in a noble manner.

“Now the Love that belongs to the Popular Aphrodite is in very truth popular and does his work at haphazard: this is the Love we see in the meaner sort of men; who, in the first place, love women as well as boys; secondly, where they love, they are set on the body more than the soul; and thirdly, they choose the most witless people they can find, since they look merely to the accomplishment and care not if the manner be noble or no. Hence they find themselves doing everything at haphazard, good or its opposite, without distinction: for this Love proceeds from the Goddess who is far the younger of the two, and who in her origin partakes of both female and male. But the other Love springs from the Heavenly Goddess who, firstly, partakes not of the female but only of the male; and secondly, is the elder, untinged with wantonness: wherefore those who are inspired by this Love betake them to the male, in fondness for what has the robuster nature and a larger share of mind. Even in the passion for boys you may note the way of those who are under the single incitement of this Love: they love boys only when they begin to acquire some mind—a growth associated with that of down on their chins. For I conceive that those who begin to love them at this age are prepared to be always with them and share all with them as long as life shall last: they will not take advantage of a boy's green thoughtlessness to deceive him and make a mock of him by running straight off to another. Against this love of boys a law should have been enacted, to prevent the sad waste of attentions paid to an object so uncertain: for who can tell where a boy will end at last, vicious or virtuous in body and soul? Good men, however, voluntarily make this law for themselves, and it is a rule which those ‘popular’ lovers ought to be forced to obey, just as we force them, so far as we can, to refrain from loving our freeborn women. These are the persons responsible for the scandal which prompts some to say it is a shame to gratify one's lover: such are the cases they have in view, for they observe all their reckless and wrongful doings; and surely, whatsoever is done in an orderly and lawful manner can never justly bring reproach.

“Further, it is easy to note the rule with regard to love in other cities: there it is laid down in simple terms, while ours here is complicated. For in Elis and Boeotia and where there is no skill in speech they have simply an ordinance that it is seemly to gratify lovers, and no one whether young or old will call it shameful, in order, I suppose, to save themselves the trouble of trying what speech can do to persuade the youths; for they have no ability for speaking. But in Ionia and many other regions where they live under foreign sway, it is counted a disgrace. Foreigners hold this thing, and all training in philosophy and sports, to be disgraceful, because of their despotic government; since, I presume, it is not to the interest of their princes to have lofty notions engendered in their subjects, or any strong friendships and communions; all of which Love is pre-eminently apt to create. It is a lesson that our despots learnt by experience; for Aristogeiton's love and Harmodius's friendship grew to be so steadfast that it wrecked their power. Thus where it was held a disgrace to gratify one's lover, the tradition is due to the evil ways of those who made such a law— that is, to the encroachments of the rulers and to the cowardice of the ruled. But where it was accepted as honorable without any reserve, this was due to a sluggishness of mind in the law-makers. In our city we have far better regulations, which, as I said, are not so easily grasped."

-taken from wikipedia and Plato's Symposium 180c-182d

#aphrodite#venus#cupid#pagan#paganism#european art#literature#history#paintings#plato#pausanias#ancient greece#Marc Charles Gabriel Gleyre

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

GUYS, DID YOU KNOW THAT THERE IS ONE TIME ARTEMIS REJECTED A GUY WITHOUT KILLING HIM???

According to Pausanias' Description of Greece, a river god named Alpheus fell in love with Artemis. And Artemis knows this. Instead of giving him the "scorpion sting" or "devoured by your dogs" treatment, she decided to prank him.

Artemis hosts a party for her nymph friends, and when Alpheus sneaks in to abduct her, Artemis covers her and her friends' faces with mud. Alpheus gets confused and can't find the real Artemis, so he just leaves ALL IN ONE PIECE (maybe except for a broken heart).

See, Artemis isn't always vengeful against men.

Source if you're interested.

#artemis#alpheus#greek mythology#greek goddesses#greek deity#description of greece#pausanias#things i found on Theoi.com

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The meal after the victorious battle of Plataea

According to Herodotus, the historian who described the Greek-Persian wars in detail, when the Spartan Commander-in-Chief Pausanias, after the victorious battle of Plataea, entered the scene of the killed Persian General Mardonius:

"... he ordered the bakers and the cooks to prepare the dinner Mardonius usually enjoyed. When Pausanias saw the luxurius daybeds, as well as the gold and silver tables loaded with the majestic dinner, he was surprised. As a joke, he ordered his own servants to prepare a Spartan dinner. The difference was so great that he laughed, called all the Generals of the Greeks and said to them, pointing to the two dinners: "Greeks, I called you here to show you the foolishness of the Median ruler who dines like this everyday and moved against us to steal our poverty."

We know today many nutritional details of the above scene, namely that the Greek General's meal did not stand out from the hoplites battling under his command. The ration was based on barley bulgur and unleavened barley bread, olives preserved in brine, onions and cured fish wrapped in fig leaves. In his haversack every soldier had salt and thyme to flavor the food, dried figs and a small spit perhaps, for the rare occasion that he would find meat. The army's logistics provided also goat cheese, fresh fruit (figs and grapes in the case of the Battle of Plataea, which took place in late August) and wine diluted with water to give courage to the fighters.

The Persians, who, in their vast and multinational troops, served Greeks, Indians and Ethiopians, were supplied by their Theban allies. They also ate barley bread, along with some goat meat, dried dates and almonds. However, the pyramidal structure of the Persian army required Mardonius and his high rank officers to enjoy roasted ducks and peacocks, pilaf flavored with cardamom, honey dripping sweets, wine made from dates and strong barley beer.”

Source: https://olyrafoods.com/blogs/wisdom-treats-blog/the-meal-after-the-victorious-battle-of-plataea

Olyra is the site of a Greek businessman who makes alimentary products inspired by the ancient Greek diet. The information he provides about the culinary habits of ancient Greeks and Persians when these peoples campaigned seems trustworthy.

I remind here that the question of the motivation of the Persian attempt to conquer Greece is a complex one in Herodotus. But the story reported here illustrates well the theme of the imperial hybris, i.e., of the desire of empires and elites which have already too much to acquire even more through further conquest and expansion.

I remind also that this report is not a simplistic illustration by Herodotus of some cliché of “Oriental decadence”, as Mardonius is portrayed in the Histories as aggressive and prideful, but also as competent and brave.

And of course the tragic irony of the same story is that Pausanias, the victor of Plataea and savior of the Greek freedom, the defender of the austere Greek way of life face to the Persian culinary luxury, not only adopted some time later the lavish lifestyle of the Persian nobility, but he was even accused of plotting with Xerxes for the subjugation of Greece and was put to death for this reason by the Spartans - through starvation...

Bust of Pausanias, in the Capitoline Museums, Rome.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Front and (a rare) back photo of the 10ft tall "Athena Velletri" a Roman marble copy of an original Greek bronze. The original bronze statue was mentioned by the Roman traveller Pausanius as being situated on the Acropolis in Athens. Her right arm originally held a spear whilst her left is generally believed to have held a phiale (a libation bowl), although a statue of Nike has also been suggested. Found in Italy, she currently resides in the Louvre 🏛🏺

#athena#athena velletri#greek goddess#goddess#ancient greece#ancient greek#bronze#athens#acropolis#daughter of zeus#marble copy#pausanias#louvre#louvre museum#greece#antiquity#nike#phiale#lady athena#goddess of wisdom

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

new evil ancient horse just dropped

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pausanias must be mentioned, that indefatigable traveller and sightseer of the second century AD, for he is a source of the utmost importance from more than one standpoint. He is invaluable not only because of the spontaneous, if somewhat naive, religiosity in his approach to myths relating to the sites he visited and described in the course of his travels, but also because he brings us in touch with the local beliefs still astonishingly alive in his days and full of regional rivalries.

— River Gods of Greece by Harry Brewster

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

part of why Pausanias feels so conversational is because he just stops in the middle of describing a temple and tells the reader he's stopping because it came to him in a dream that he should shut up about it. You're looking through a little window into the far past and suddenly the author's hand reaches in front of you to close the curtain.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Theatre, Epidaurus, Greece, 4th century BC

VS

Giorgio Morandi, Shell and other objects, 1948

#giorgio morandi#italian art#modern art#Etchings#etching#still life#epidaurus#greece#ancient greece#archaeology#greek archaeology#pausanias#Peloponnese#Argolis#asclepius#unesco#world heritage site#landscape architecture#world heritage#architeture#polykleitos the younger

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

“There is also a beast called the elk, in form between a deer and a camel, which breeds in the land of the Celts. Of all the beasts we know it alone cannot be tracked or seen at a distance by man; sometimes, however, when men are out hunting other game they fall in with an elk by luck. Now they say that it smells man even at a great distance, and dashes down into ravines or the deepest caverns. So the hunters surround the plain or mountain in a circuit of at least a thousand stades, and, taking care not to break the circle, they keep on narrowing the area enclosed, and so catch all the beasts inside, the elks included. But if there chance to be no lair within, there is no other way of catching the elk”.

- Pausanias, Descriptions of Greece, [9.21.3] On Fabulous Animals

#pausanias#elk#ancient greece#i am tickled pink by the description of it being between a deer and a camel#oh elk#you mysterious bastards#celtics#history

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aphrodite putting on a sword, unknown date/artist. Marble statue in Florence, Accademia di Belle Arti.

"On the left of the Lady of the Bronze House they have set up a sanctuary of the Muses, because the Lacedaemonians used to go out to fight, not to the sound of the trumpet, but to the music of the flute and the accompaniment of lyre and harp. Behind the Lady of the Bronze House is a temple of Aphrodite Areia (Warlike) The wooden images are as old as any in Greece."

-Pausanias, Description of Greece 3.17.5

#aphrodite#venus#ancient greece#pagan#paganism#european art#antiquities#sculpture#literature#history#pausanias#ancient history#art

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been thinking.

In Pausanias's "Description of Greece", he mentioned an altar with the picture of Hyacinthus and Polyboea being taken to "heaven" (or maybe Olympus) by many deities.

And by many deities, I mean Aphrodite, Athena, Artemis, Demeter, Persephone, Hades, the Fates, and the Seasons. These are four Olympians, the King and Queen of the Underworld, the incarnations of Fates and Seasons themselves.

Like, not every heroes and heroines get that much special treatment. What did Hyacinthus and Polyboea do that a bunch of important gods decided to help them? How come we never get to know what great deed or sacrifice they had made for this enormous blessing???

I don't need sleep I neED ANSWERS!!!

#hyacinths#polyboea#greek mythology#pausanias#description of greece#the ancient people leave us the ultimate ending and give zero explanation like that

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Se pourrait-il que les Grecs, ces sages ancêtres qui nous ont transmis la raison, aient cru aux titans, aux cyclopes et aux héros dont ils ont peuplé leur mythologie ? Et, à supposer qu’ils aient tenu le Minotaure pour un mensonge de poète, doutaient-ils conséquemment de l’existence de Thésée ? À travers ces questions, Paul Veyne entreprend une enquête passionnante sur le statut de la vérité, l’expérience « la plus historique de toutes ». En étudiant la nature des mythes, leurs modalités de réception, leurs critères de vraisemblance et le scepticisme ambigu qu’ils suscitaient, il interroge les liens que ces récits entretiennent avec l’histoire, cet autre discours revendiquant un savoir sur le passé. Il s’agit donc moins dans ce livre d’interroger la crédulité des Grecs anciens que nos propres croyances."

Veyne's book about the Greeks and their myths is for sure a classic, but I will reproduce here a rather severe review of it by Dana L. Burgess. I find Burger's criticism largely valid, but I don't think that it "cancels" the thought provoking character of Veyne's essay (Burgess, Dana L. Review of Did the Greeks Believe in Their Myths? An Essay on the Constitutive Imagination. Philosophy and Literature, vol. 13 no. 1, 1989, p. 184-185. Project MUSE, available on https://muse.jhu.edu/article/418899):

"Did the Greeks Believe in Their Myths? An Essay on the Constitutive Imagination (review)

Dana L. Burgess

Philosophy and Literature

Johns Hopkins University Press

Volume 13, Number 1, April 1989

pp. 184-185

"Did the· Greeks Believe in Their Myths? An Essay on the· Constitutive Imagination, by Paul Veyne; translated by Paula Wissing; xii& 161 pp. Chicago: University of Chicago Press...On the final page of his essay Veyne responds to his title's question, '"But of course they believed in their myths!' We have simply wanted also to make it clear that what is true of 'them' is also true of ourselves . . ." (p. 129). According to Veyne the Greeks, like us, were able both to believe and to disbelieve aspects of their myths. "They believe in them, but they use them and cease believing at the point where their interest in believing ends" (p. 84). Veyne begins his book with some hard-headed analyses of ancient historiography . He dwells mostly on Pausanias, but uses various historians' statements on credulity to establish the idea that ancient historians are little concerned with the accuracy of their sources. Veyne asserts that the historian's phrase "it is said" may automatically mean "it is true," given a certain understanding of truth. On the other hand, both Pausanias and Herodotus make curious statements which suggest their incredulity of the very stories they relate. Veyne understands from the tension between credulity and incredulity that the nature of ancient belief was complex and dynamic. From this notion of Greek credulity Veyne develops his own ideas about the nature of truth. He is thus able, by the end of the essay, to affirm that our own varieties of belief resemble those of the Greeks precisely because truth is, and always was, "plural and analogical" (p. 87).

But are the statements of these ancient historians valid grounds for an understanding of the nature of ancient mythological belief? In the jump from historiography to theory of myth, Veyne has depended more upon his own notions of the plural nature of truth than he has on ancient evidence for the nature of mythological belief. This book is not about Pausanias, or anything else in antiquity. The author really wants to talk about the "plural and analogical" (p. 87) nature of truth; so these discussions of ancient thought finally seem nothing more than a peg for his own assertions. He has used his own understanding of the nature of truth to argue for an ancient similarity between historical and mythological credulity.

"An ancient historian does not cite his authorities, for he feels that he is a potential authority himself" (p. 9). So too does Veyne feel that his own notions of truth are more important than the precise analysis of ancient historiography and mythography (And, like the ancient historians whom he discusses, Veyne does not feel compelled to cite his authorities with any rigor. There are at least twenty-four instances in which Veyne fails to give an adequate reference for a quotation or discussion of another author's work.) By the time we have reached the final chapter we have wholly lost Pausanias and ancient thought. The argument and its language have become quite vague: "Our hypothesis can be stated in this way as well: At each moment, nothing exists or acts outside these palaces of the imagination. . . . These palaces are not built in space, then. They are the only space available" (p. 121). This reader was much more interested in Veyne's analysis of ancient historiography than in his philosophical speculations . Finally, it is not clear that Veyne's musings on the mutability of truth are particularly illuminated by his discussion of Pausanias's doubt. Certainly Pausanias had notions of truth which merit a detailed examination. Ancient authors are done a disservice when a precise examination of their thought is replaced by a critic's own assertions about the nature of truth.

Whitman College

Dana L. Burgess"

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

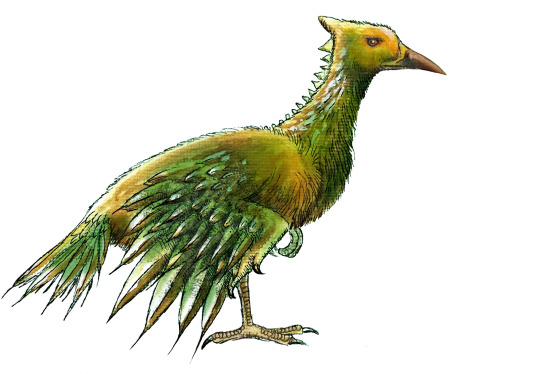

Stymphalian Bird

Stymphalian Bird

Pausanias theorized that the Stymphalian birds originated in Arabia, citing the presence of fierce desert birds known as the Stymphalides. He then admits that the population found at Stymphalos, in Arcadia, may have been the result of a few wayward birds making their way into Greece. Following this line of reasoning, Pausanias deduces that they earned the name of Stymphalides due to their fame in Greece, and the name then supplanted whatever name they originally had in Arabia!

Variations: Stymphalide, Bird of Ares

The appearance of the Stymphalian birds is no less muddled. Their most feared weapon is the sharpened, pointed tips of their wing feathers, which they fling like darts to stab their prey. Sometimes their feathers and beaks are made of bronze or iron, the better for piercing armor. Pausanias described them as about crane-sized, but resembling the ibis in shape, but with a stronger bill; elsewhere he says they are like hawks or eagles. In Greek art they have been represented as ibises, swans, and other such waterfowl; at least one obol from Stymphalos shows a bird with a short crest and a stout, powerful bill. Finally, no doubt influenced by tales of harpies and sirens, the temple of Stymphalian Diana also has stone statues of virgins with birds’ feet.

It remains true that the Stymphalian birds were first and foremost associated with Lake Stymphalia. They terrorized the region, ravaging crops, killing people, and poisoning the ground with their dung. Fox suggests that the legend originated as a glamorization of a plague or pestilence rising from the marshes, which would explain their noxious qualities. While their feathered darts could pierce armor, they were powerless against a certain type of tree bark, which held them fast like quicklime. There was only so much bark to go around, though, and the birds seemed numberless.

It was this scourge that Heracles was sent to destroy. As his sixth labor, it was one of a list of impossible tasks, and indeed the vast numbers of birds seemed beyond the hero’s strength. Heracles got around this by exploiting a simple fact – despite their numbers and ferocity, Stymphalian birds were as easily spooked as sparrows. Fashioning a pair of bronze castanets, he made such a din that the flock took off in a panic; from there he shot a great number down with his arrows, while the remainder of the birds flew off and were never seen in Arcadia again.

That was not the end of the Stymphalian birds, as from Greece they made their way to the Black Sea and populated the Island of Ares, where they became sacred guardians to the god of war. It was this flock that Jason and his Argonauts encountered on their way to Colchis. While the birds of Ares managed to wound the Argonaut Oileus with a feather projectile, they were scared off once more by the noise of rattling bronze armor, but not before pelting the Argonauts with a hailstorm of feathers.

References

- Aldington, R. and Ames, D. trans.; Guirand, F. (1972) New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology. Paul Hamlyn, London.

- Ames, D. trans.; Guirand, F. (1963) Greek Mythology. From Mythologie Generale Larousse. Paul Hamlyn, London.

- Apollonius, Coleridge, E.P. trans. (1889) The Argonautica. George Bell and Sons, London.

- Fox, W. M. (1964) The Mythology of All Races v. I: Greek and Roman. Cooper Square Publishers, New York.

- Pausanias, Levi, P. trans. (1979) Guide to Greece, volume 2: Southern Greece. Penguin Books, London.

Original Traditional Art before it gets My Surreal/Psychadelic Touch - A Book Of Creatures

PS: Btw it really sucks that tumblr doesn’t let people upload gifs with less than 10mb, makes us optimize our gifs and even then it optimizes them even further in theyr servers to 3mb i believe

#Stymphalian#greece#greek#mythology#heracles#ares#arabia#pausanias#armor#godofwar#blacksea#roman#folklore#legendary#creature#greekgods#native#trippy#surreal#psichadelic#art#artist#photomanipulation#gif#animation#macabre#monster#spirit#bird#arcadia

3 notes

·

View notes