Text

The Hephthalite (White Hun) art at Bamiyan 6th-8th C. CE. A lot more on my blog, link at bottom.

"Three things shine before the world and cannot be hidden. They are the moon, the sun, and the truth..." (The Essence of Buddhism, 1907)

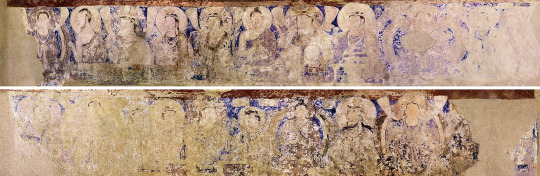

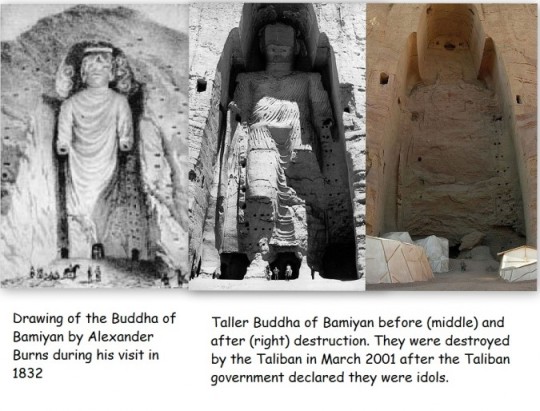

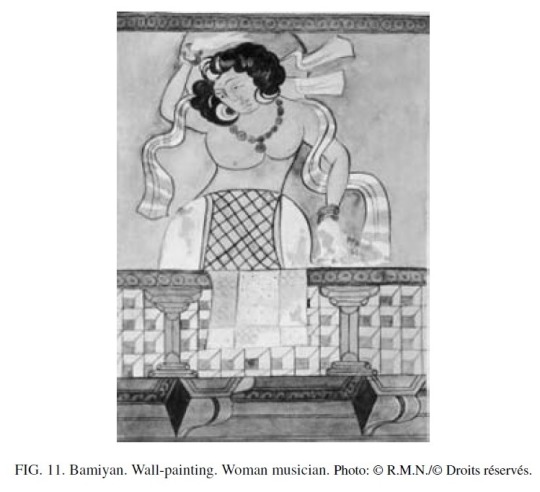

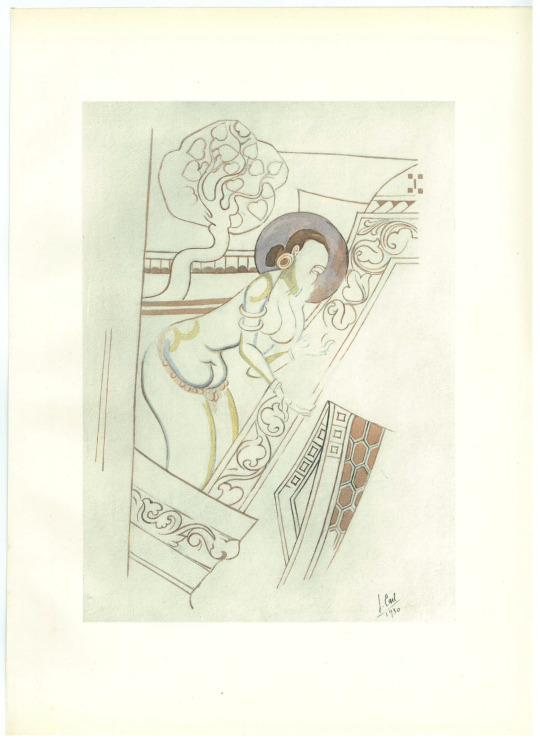

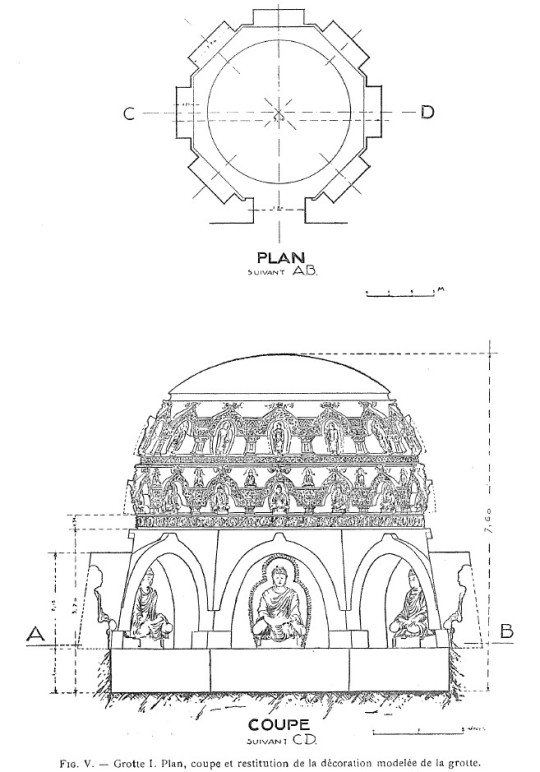

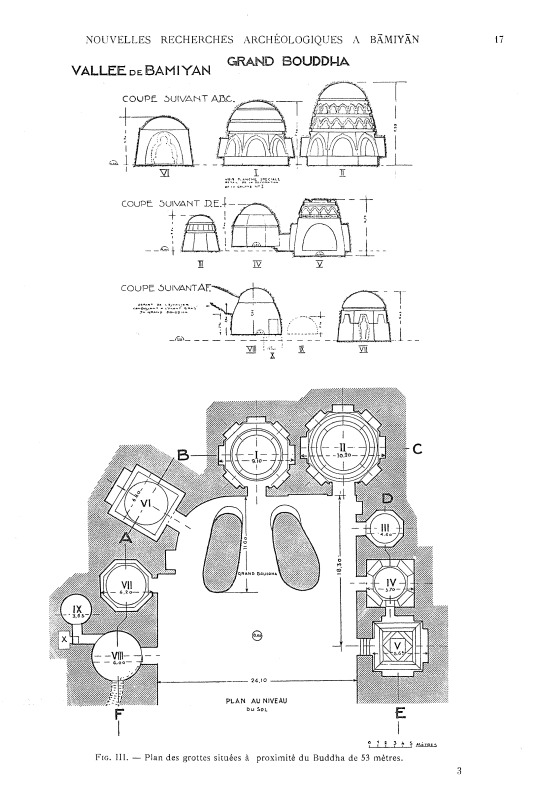

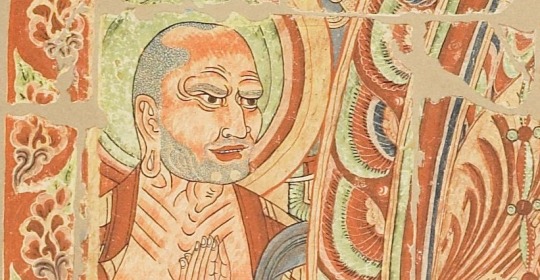

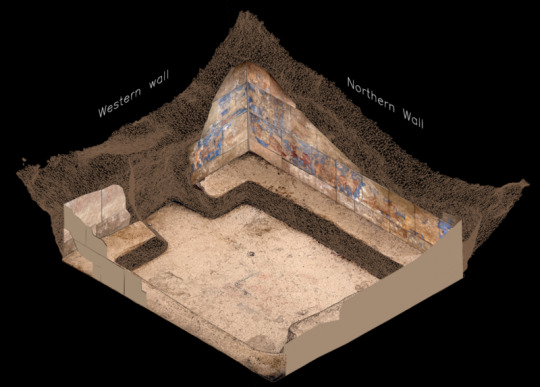

The Buddhas of Bamiyan date to the period of Hephthalite (White Hun) rule in the region. Around the Buddhas were murals of the Hunnic rulers and donors who commissioned the works of art. Carved into the mountains were chambers with additional artworks, mostly Buddhist-themed but there are also some Iranian/Zoroastrian elements. The murals of the Huns and the two giant Buddha statues were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. The Hunnic murals were probably the oldest oil paintings in the world according to the Archaeological Institute of America:

"In 2008, their research revealed that paint samples from 12 of the caves contained "drying oils," most likely walnut and poppy-seed oils, which are key ingredients in oil-based paints. In the ancient Mediterranean world, drying oils were used in medicines, cosmetics, and perfumes. Scholars long believed they were first added to paints much later in medieval Europe. "There was no clear material evidence of drying oils being used in paintings before the 12th century A.D. anywhere in the world, until now," says Yoko Taniguchi, a Japanese conservation scientist on the team. The murals at Bamiyan, which lay on the Silk Road where goods and ideas flowed between East and West, date to the mid-seventh century A.D. "This is one of the most important art-historical and archaeological discoveries ever made," she says." (Archaeology Magazine)

Chinese historians noted that the Huns had more literary records than the Sogdians, yet none have survived. Some would have been destroyed by the Turk and Persian invasions, but the primary culprits were probably the Arab Muslims and other later Muslims (such as later Turks):

"In the seventh century, after the destruction of the Hephthalite state, Tokharistan was visited by a Chinese pilgrim, Hsüan-tsang, who wrote of the Hephthalite population: [Their] language and letters differ somewhat from those of other countries. The number of radical letters is twenty-five; by combining these they express all objects around them. Their writing is across the page, and they read left to right. Their literary records have increased gradually, and exceed those of [the people of] Su-le or Sogdiana." (UNESCO: History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. III).

"Hsüan-tsang has left a detailed description of the Buddhist centres and monastic life in the period of the Huns, waxing lyrical when he visits Bamiyan. From a cultural point of view, his most valuable observation is the following: These people are remarkable, among all their neighbours, for a love of religion (a heart of pure faith); from the highest form of worship to the three jewels, down to the worship of the hundred (i.e. different) spirits, there is not the least absence (decrease) of earnestness and the utmost devotion of heart. The merchants, in arranging their prices as they come and go, fall in with the signs afforded by the spirits. If good, they act accordingly; if evil, they seek to propitiate the powers. There are ten convents and about 1000 priests. They belong to the Little Vehicle, and the school of the Lokottaravadins" (UNESCO: History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. III).

"Information about the religion of the Hephthalites is provided by the Chinese sources. Sung Yün reports that in Tokharistan ‘the majority of them do not believe in Buddhism. Most of them worship wai-shên or “foreign Gods”.’ He makes almost identical remarks about the Hephthalites of Gandhara, saying that they honour kui-shên (demons). The manuscripts of the Liang shu (Book 54) contain important evidence: ‘[the Hephthalites] worship T’ienshên or [the] heaven God and Huo-shên or [the] fire God. Every morning they first go outside [of their tents] and pray to [the] Gods and then take breakfast.’ For the Chinese observer, the heaven God and the fire God were evidently foreign Gods. We have no evidence of the specific content of these religious beliefs but it is quite possible that they belonged to the Iranian (or Indo-Iranian) group." (UNESCO: History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. III).

The Muslims had done battle with these inanimate objects for over a thousand years, even after the advent of cannons they couldn't be brought down. The Turko-Mongol ruler, Babur, attempted to destroy them in the 16th century and failed. As did the Turko-Mongol ruler Aurangzeb, in the 17th century, who only managed to damage the legs of the Buddha. The Oghuz Turk, Nader Afshar, tried to destroy them using cannons in the 18th century but failed. Afghan king Abdur Rahman Khan destroyed part of one of the faces in the 19th century. Finally the Taliban, misusing explosives technology invented by the West and China, destroyed them in 2001.

And now thanks to Western technology these idols will live on forever in digital form. The Japanese have already begun physical reconstruction of the artworks. Because the Taliban isn't trustworthy, the restored artworks will be kept in Japan.

#the huns#huns#ancient history#art history#oil painting#paintings#lost art#archaeology#wall murals#history#antiquities#art#ancient art#middle ages#medieval art#pagan#museums#sculpture#statue#hephthalites

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Avar grave goods from the burial at Kunbabony 7th C. CE. I also added a map to show where the finds came from. See the white star in the Avar Kingdom.

"The burial of an adult man at Kunbábony (AC2) contained 2.34 kilograms of gold in form of weaponry covered with precious metal foils, ornamented belt sets with so-called pseudo buckles and drinking vessels. The funerary attire and the grave goods are understood as elements of the steppe nomadic material culture of the period. The technological details and the decoration however suggest a culturally heterogeneous origin. Presented objects: 1-2. earrings; 3. armring; 4. eagle head-shaped end of a sceptre or horsewhip; 5-13. elements of the belt with the so-called pseudo buckles (9-10.); 14. crescent-shaped gold sheet; 15-18. sword fittings; 19. jug; 20. drinking horn. Pictures were first published in H. Tóth & Horváth."

-from 'Genetic insights into the social organisation of the Avar period elite in the 7th century AD Carpathian Basin'

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

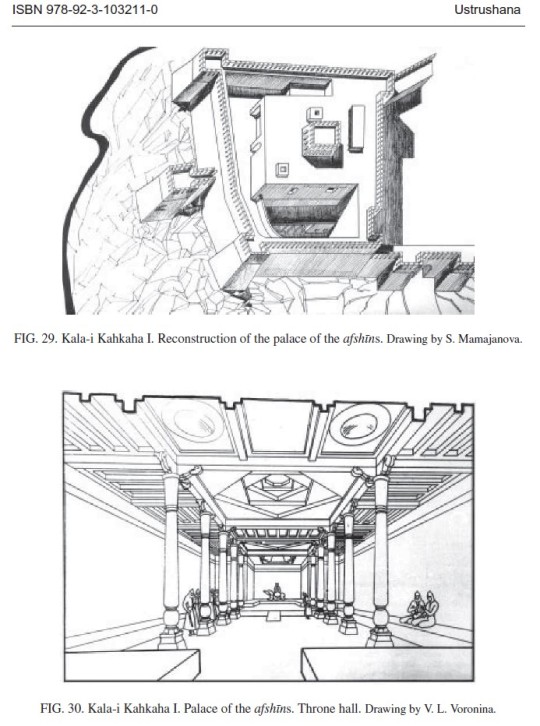

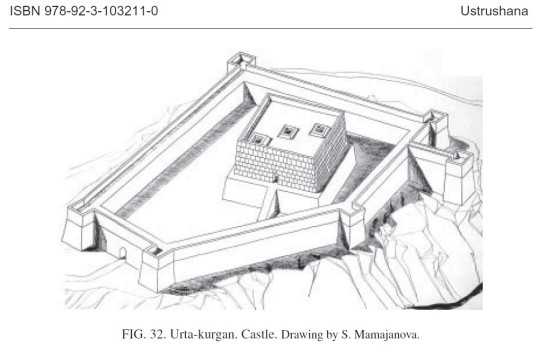

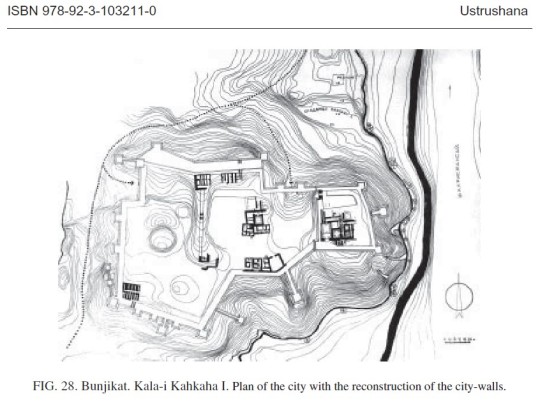

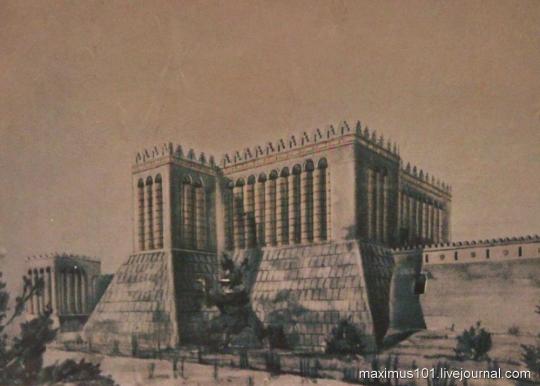

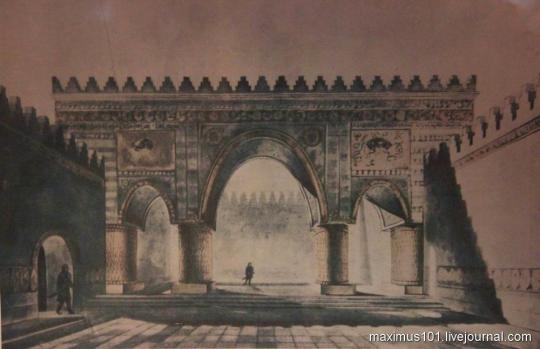

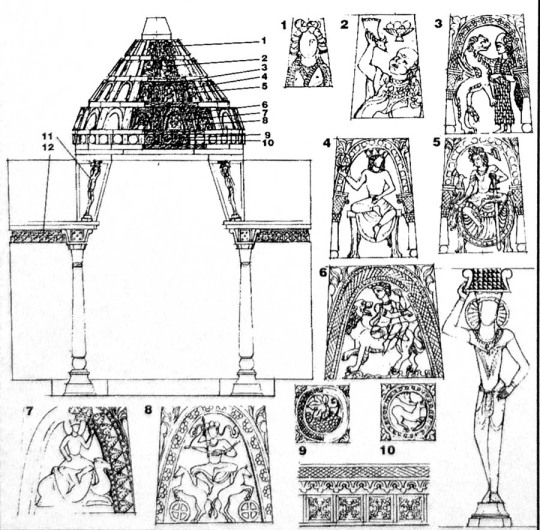

Ushrusana: City of Bunjikat, Kala-i Kahkaha I & II Palaces, etc. 5th-9th C. CE. More on my blog, link at bottom.

Ushrusana was a Sogdian principality. From the 5th-7th C. CE it was ruled by the Hephthalites (White Huns). It was briefly ruled by the Turks from 560-600 CE. From 600-892 CE it was ruled by the Afshins who were rulers of Sogdian or Hunnic ancestry. Despite the Arab Muslims invading the region in the 600s CE, the Ushrusanians were able to hold onto their independence and traditions until almost the 10th C. CE. The inhabitants were said to practice "The White Religion" according to written sources (UNESCO publication: History of civilizations of Central Asia, v. 3: The Crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750).

From Wikipedia:

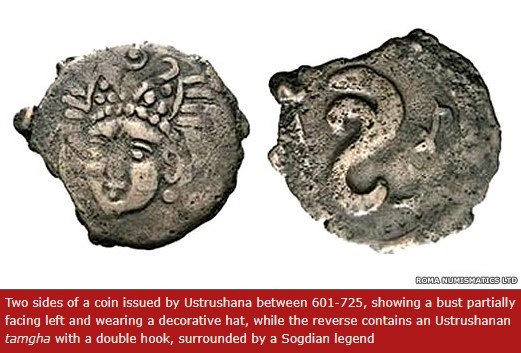

"The Principality of Ushrusana (also spelled Usrushana, Osrushana or Ustrushana) was a local dynasty ruling the Ushrusana region, in the northern area of modern Tajikistan, from an unknown date to 892 CE. The rulers of the principality were known by their title of Afshin. Ushrusana may have been associated with remnants of the Kidarites in Eastern Sogdiana. The Kidarites, who are otherwise known for their rule in Gandhara in the 4-5th century CE, may have survived and possibly established a Kidarite kingdom in Usrushana. This connection may be apparent from the analysis of the coinage, and in the names of some Ushrusana rulers such as Khaydhar ibn Kawus al-Afshin, whose personal name is attested as "Khydhar", and was sometimes written wrongly as "Haydar" in Arabic. In effect, the name "Kydr" was quite popular in Usrushana, and is attested in many contemporary sources. The title Afshin used by the rulers of Usrushana is also attested in a Kidarite ruler of Samarkand of the 5th century named Ularg, who bore the similar title "Afshiyan" (Bactrian script: αφϸιιανο)."

From UNESCO:

"Ustrushana was closely linked to Sughd ( Sogdiana) by its historical destiny and ethnic, linguistic and cultural history. It originally formed part of the territory of Sughd, but then developed its own historical and cultural identity as the area became more urbanized. To the west and southwest it bordered on Sughd, to the east and north-east on Khujand and Ferghana and to the north on Ilak and Chach (present day Tashkent). The discovery and deciphering of the Sogdian documents from Mount Mug on the upper Zerafshan established that the correct form of the name is Ustrushana.

The population of Ustrushana consisted of tribes and clans, speaking a dialect of Sogdian, with an economy based on settled agriculture and urban crafts. The Chinese Buddhist pilgrims Hsüan-tsang and Huei-ch’ao note a certain community of culture – language, mores and customs – between the people of Ustrushana and the Sogdians of the Zerafshan valley, Ferghana, Chach and the adjacent regions. Hsüan tsang calls the whole land between Suyab and Kish by the name ‘Su-le’, and its population ‘Sogdians’. Archaeological excavations show common traits in the artefacts of the region’s culture.

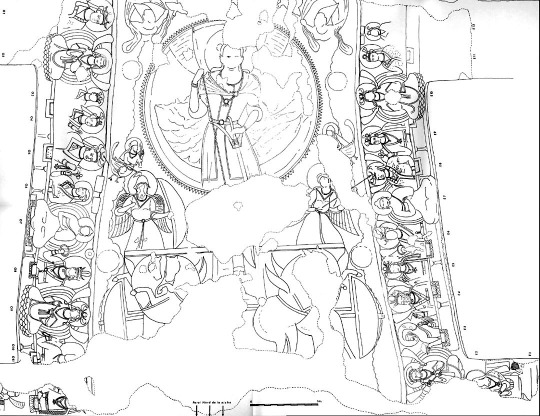

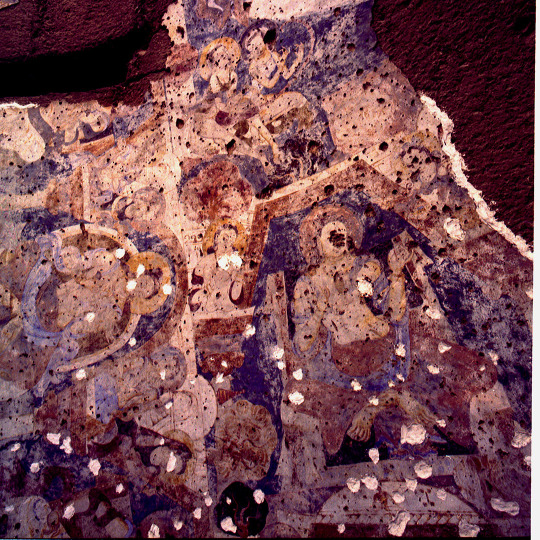

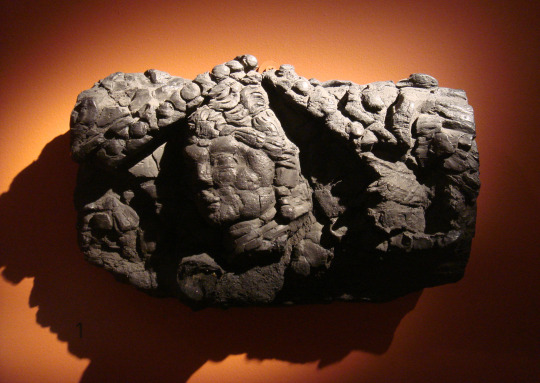

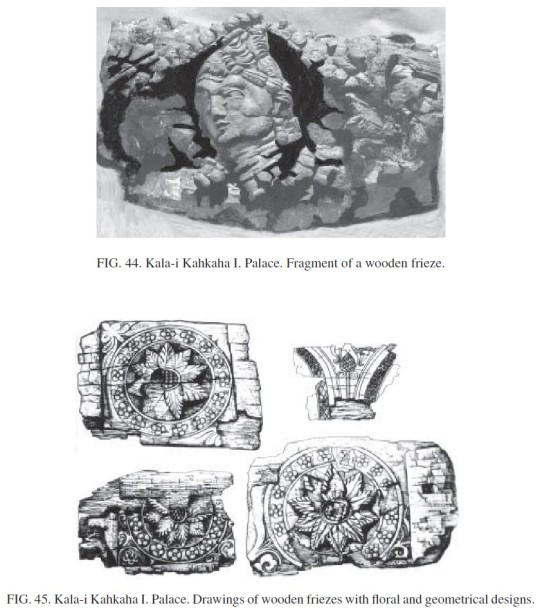

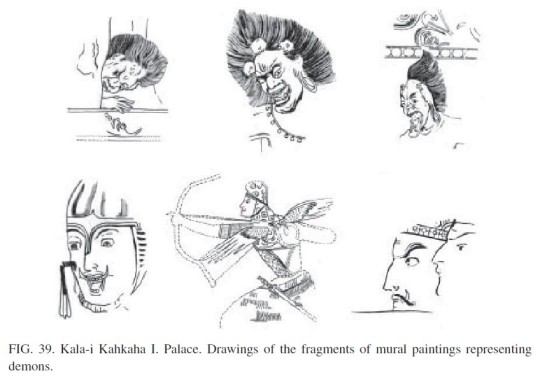

The architectural ornamentation and monumental art of Ustrushana are rich and varied. Murals of high artistic quality with floral and geometric patterns and depictions of secular, epic-heroic, mythological and cultural scenes were an important feature of the interior decoration of palaces, castles and other buildings (Figs. 35–39). Many examples of wood-carving and clay-moulding have survived: columns, beams, cornices, friezes, thresholds, door posts and door frames, lintels, window grilles, entrance screens, artistic clay mouldings and patterned fired bricks (Figs. 40–45). The capital, Bunjikat, was the main centre for the development of architecture and the applied arts.

Ustrushana also had a rich variety of spiritual and cultural traditions, for the most part purely local. According to written sources, the Ustrushanians practised the so-called ‘white religion’, in which carved wooden idols were adorned with precious stones. Idols of this type were kept in the palaces of Haidar (the Ustrushanian ruler) in Samarra, in Ustrushana itself and in Buttam, and they were also brought to Ustrushana by refugees from Khuttal. Many toponyms in this region included the word mug (fire-worshipper). So far archaeologists have discovered the castle and palace shrines mentioned above and an urban idol temple. Other finds include wooden idols in Chilhujra (Fig. 46), a house of fire at Ak-tepe near Nau, a dakhma at Chorsokha-tepe near Shahristan, rock burial vaults near Kurkat with human remains in khums (large jars) and ossuaries, and a number of other burials in khums and ossuaries in various regions of Ustrushana.

All these finds are evidence of a particular local form of Zoroastrianism that incorporated the worship of idols and various divinities and other religious practices, and is also reflected in the monumental art of Ustrushana.

The worship of the ancestor of a family line and dynasty is known from written sources. It is also known that religious as well as secular power was concentrated in the hands of the afshins of Ustrushana and that they were almost deified, as is clear from the formula by which they were addressed – ‘To the lord of lords from his slave so-and-so the son of so-and-so’."

#sogdiana#the huns#huns#ancient history#goddess#asian history#antiquities#history#art#pagan#paganism#sculpture#museums#statue#woodworking

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hephthalite (White Hun) bronze administrative seal of an official 4th-6th C. CE

"Rare bronze stamp seal of the Hephthalites or the White Huns as they're also known. Hunnic Empire of the Hindu Kush, 4th.-6th. century CE. Likely an administrative seal for an important official, due to it's size and fine workmanship. Diameter of the base 32-33 mm. max and it's c. 32 mm. tall. Very heavy and in solid bronze weighing 53.39 grams.

Provenance: Johan Dæhnfeldt Estate Collection, 2012, acquired in the 1990s in Copenhagen."

-info from Senatus Consulto

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

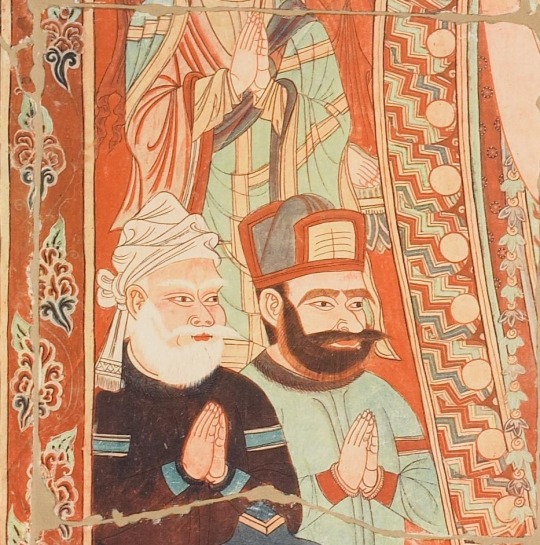

Detail of the Indo-European people in the Praņidhi scenes I just posted from the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves near Turfan, Xinjiang 9th C. Probably Sogdians and Tocharians. All of the original artworks were destroyed by the Allies in WW2, but were preserved by German photography.

#indo european#tocharian#sogdiana#ancient history#history#antiquities#art#paintings#ancient art#art detail#lost art

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

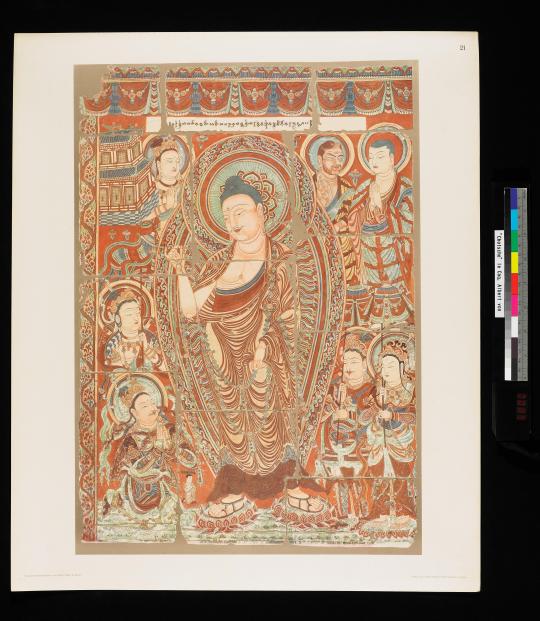

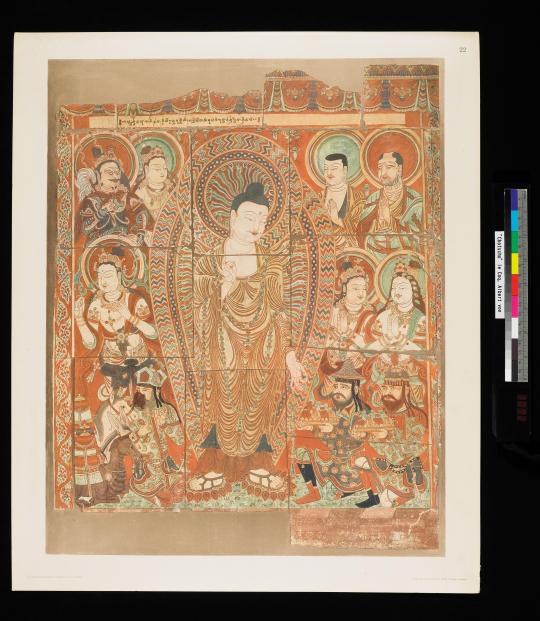

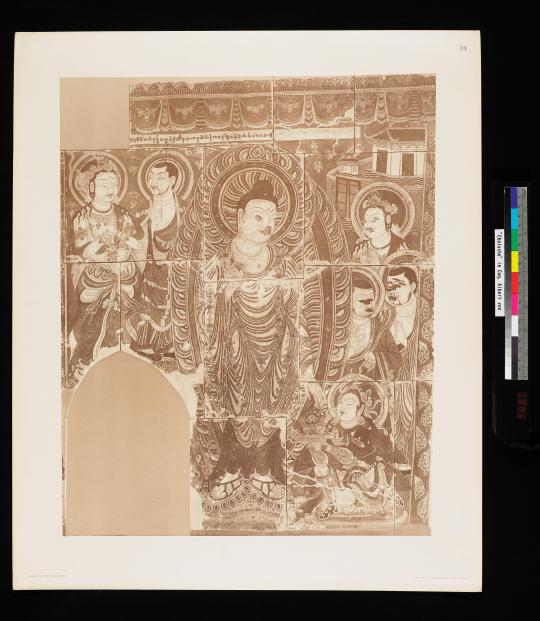

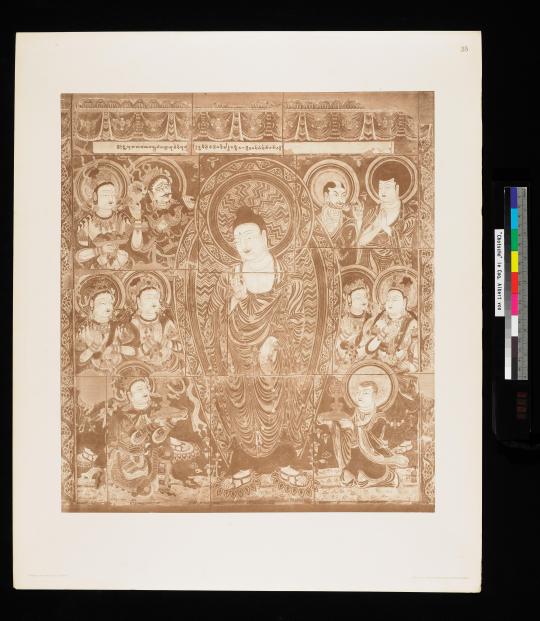

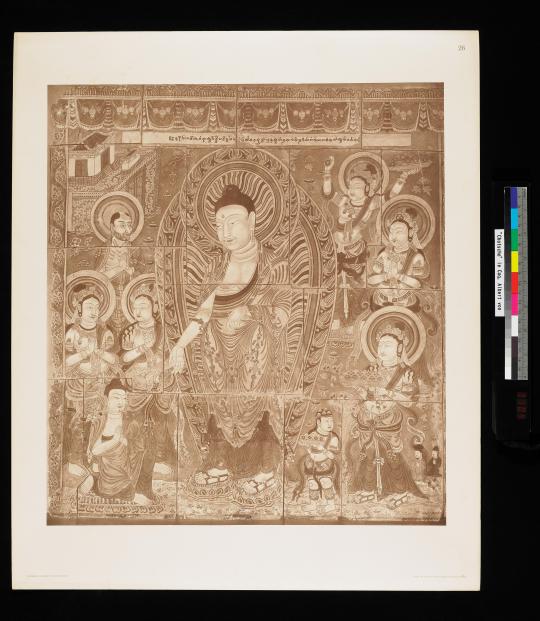

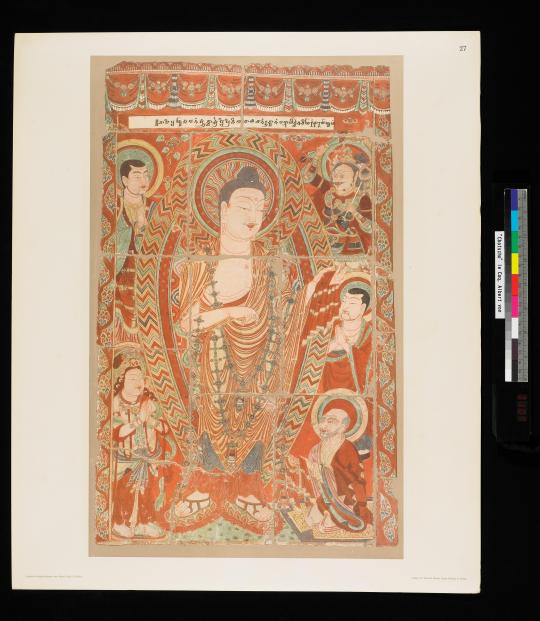

These are from "Chotscho - Facsimile Reproduction of Important Findings of the First Royal Prussian Expedition to Turfan in East Turkistan". The book is free online. All of these artworks were destroyed by the American, Russian, British, and French bombings of Berlin in WW2. Luckily the Germans took high resolution photos before the Allies destroyed them.

Description from book: "A magnificent broadsheet catalogue containing the results of the Second German Turfan Expedition (1904-1905) led by Le Coq. Contains a wealth of photographs of wall paintings, statues and ancient documents found in the Turfan region at Chotscho (the ancient city of Gaochang), the Bezeklik Caves, and the Toyuk Caves. The original prints of pictures from the Bezeklik Caves, which make up the majority of this volume, were destroyed in the Second World War air raid, making this volume the only remaining record."

There are both people with East Asian and Caucasian facial features in the artworks. From what I gathered, this seems to be dated to the Uyghur ruling period. The people with East Asian features seem to be Uyghurs. The people with Caucasian features seem to be either Sogdians or Tocharians. I'm not sure what alphabet is present.

#tocharian#sogdiana#uighur#indo european#ancient history#history#antiquities#art#lost art#paintings#old books

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

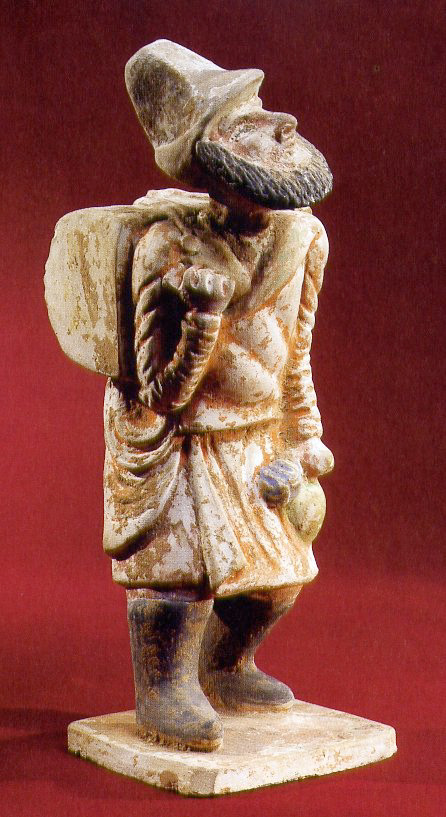

Foreign merchant (with Sogdian appearance) in China 618-907 CE

By the time the Hephthalites (White Huns) were destroyed the Sogdians had such a widespread influence that they were able to continue to enjoy their prosperity for another century. However, the crippling of the Hun's power by the Turks and Persians also eliminated Sogdiana's safety net and made them vulnerable. The chaos created to the east by the Turkic An Lushan rebellion in China and the chaos created to the west by the Sassanid's blundered aggression closed the doors on the Sogdian era of prosperity that had begun under Hunnic rule. Even after the An Lushan rebellion ended, China [one of the Sogdian's most important trading partners] was in ruins and vulnerable to other threats. Trade routes were choked off by hostile armies. Instability meant more danger for travelers. Sassanid rule had become so dysfunctional that the primitive Arab Muslims were able to conquer Persia, afterward pushing on into Sogdiana. The Hephthalites were no longer there to stabilize the Persian government as they had done in the time of Peroz and Khuvad. The Sassanids had gained their financial freedom from the Hephthalites and then, less than a century later, used that freedom to destroy themselves.

"In July of 751, a Tang army was defeated at the battle of Talas at the hands of a Turgesh-Arab alliance. The defeat effectively ended the Tang’s ability to intervene in Asia beyond the Tarim Basin. This defeat and the Tang’s subsequent inability to project force beyond the Tarim Basin played as important role in the downfall of the Sogdians as the Arab invasions themselves. With the Tang military held behind the Pamirs, the Tibetans moved to occupy the passes leading into China and into Kashmir, creating a chokehold on valuable trade networks the Sogdian merchants depended on for their livelihoods. Campaigns in 747 CE and 753 CE served to ease these Tibetan holds on the passes, but relief was only temporary. The Tang loss at Talas freed the invading Arabic forces to take control of Central Asia as well as weakening the Tang’s ability to cope with longstanding enemies closer to home. The situation for both the Sogdians and the Tang was only going to worsen. Taking advantage of the inner turmoil caused by An Lushan’s rebellion, Tibetan troops marched on and captured Chang’an in 763 CE. Rather than attempting to hold the city the Tibetans gradually withdrew along the Gansu corridor. Movement up this major trade artery by a hostile army could only have disrupted the Sogdian’s trade network, which was already likely in poor condition due to rebellions and the depredations of preceding armies. As the Tibetans withdrew they occupied the cities they encountered along the way, taking first Liangzhou (764) in the east and eventually Hami (781–782) in the west. At least two key Sogdian colonies at Hami and Chang’an, would have been seriously damaged by the rampaging Tibetans.

It is also quite likely that throughout their operations in China, Sogdian wealth would have proved a tempting target for looting by invading armies such as the Tibetans or rebelling generals. The Tibetan occupation of the passes restricted any influx of Sogdian immigrants into China to bolster the reeling Sogdian communities. With China wracked by invasions and rebellions, their Chinese colonies in ruins, the mistrust of the Sogdian people by the Tang due to the rebellion of An Lushan, and their homeland occupied by invading armies, the Sogdian trade network and nation could not but have suffered grievously. Previously the Sogdians had shown a remarkable ability to escape destruction, but the combination of forces besieging them eventually proved too great.

The Sogdians embodied the spirit of the Silk Road perhaps better than any other people. The Silk Road functioned as a conduit for exchange of both ideas and goods. The Sogdians for hundreds of years served as an invaluable vehicle for that exchange."

-The "Silk Roads" in Time and Space: Migrations, Motifs, and Materials. Edited by Victor H. Mair. Sino-Platonic Paper 228.

#sogdiana#tang dynasty#chinese art#ancient history#silk road#history#antiquities#art#sculpture#statue#ancient art

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sogdian and Chinese men of the Tang Dynasty 618-907 CE

Despite the An Lushan revolt probably primarily consisting of populations physically similar to modern-day East Asians, as shown by the leadership overwhelmingly of Kumo Xi and Turkic ancestry, Caucasoid populations such as the Sogdians were targeted for their foreign appearance. The butchers actually seem to have been initially on the Turkic side and were defectors who switched sides to join the Tang Chinese side later. Tian Shengong was initially a supporter of the Turkic rebellion but defected to China later, he was the leader behind the Yangzhou Massacre of 760.

Gao Juren was the leader behind the ethnic cleansing of Sogdians in Fanyang and Youzhou. He initially supported the Turkic rebellion and appears to have been of Goguryeo origins (one source said he came from present day North Korea precisely) but defected to China later. Gao Juren was killed a short time after this: "The former Yan rebel general Gao Juren of Goguryeo descent ordered a mass slaughter of West Asian (Central Asian) Sogdians in Fanyang, also known as Jicheng (Beijing), in Youzhou identifying them through their big noses and lances were used to impale their children when he rebelled against the rebel Yan emperor Shi Chaoyi. High nosed Sogdians were slaughtered in Youzhou in 761. Youzhou had Linzhou, another "protected" prefecture attached to it, and Sogdians lived there in great numbers. Because Gao Juren, like Tian Shengong wanted to defect to the Tang dynasty and wanted them to publicly recognize and acknowledge him as a regional warlord and offered the slaughter of the Central Asian Hu "barbarians" as a blood sacrifice for the Tang court to acknowledge his allegiance without him giving up territory, according to the book, "History of An Lushan" (安祿山史記). (taken from Wikipedia)

From Medium:

"Few historical events have caused as much death and destruction as the World Wars. The An Lushan rebellion was one of them. The An Lushan revolt, also called the An-Shi rebellion, occurred in China from 755 to 763 AD. It was one of the bloodiest wars in human history. In 754, 52 million people lived in China, but after the war, that number dropped to 16.3 million in 764.

You may wonder if a fight in the eighth century killed as many people as the First World War.

If Chinese censuses are to be trusted, the answer is yes. Steven Pinker, a rationalist thinker, called the disaster “the biggest atrocity in history,” since it wiped away one-sixth of humanity.

Historians are divided about the death toll. Many of the deaths happened during the period because the empire was in chaos. Some experts suggest people leaving Tang China and taking refuge in neighboring regions caused the drop in population.

At Fanyangn, the Tang general Gao Jure killed all the Sogdians, even the children. He distinguished them by recognizing them by their eyes and noses. This is one of the earliest documented cases of ethnic cleansing in history, in which the rulers targeted citizens based on their ethnicity.

Tang forces slaughtered thousands of Persian and Arab merchants during the Yangzhou massacre (760) on the suspicion of assisting the rebels.

In Chinese society, the trust had completely broken down.

One of the worst tragedies happened in the city of Suiyang. After a brutal siege by the Yan forces, the Tang defenders ran out of food. The Tang soldiers, however, refused to submit. Zhang Xun, the general defending the city, murdered his concubine in front of his men and fed her to them. The troops cried, but when commanded by the general, they ate the poor woman.

Cannibalism was rampant during the siege of Suiyang. People began devouring the dead, and families began exchanging their children for food. The soldiers soon started eating the old women and then turned on young women and men of all age groups. Estimates suggest that 20,000 to 30,000 people were eaten. Yet, the Tang army refused to submit.

The number of people who died during the An Lushan rebellion could have been anywhere from 13 million to 36 million. It is easy to argue that the civil war was one of the most catastrophic disasters in human history."

-Prateek Dasgupta, The Bloody 8th Century Conflict That Wiped Out One-Sixth of the Human Population

#ancient china#tang dynasty#ancient history#history#antiquities#art#indo european#museums#statue#sculpture#chinese history#ancient art

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sogdian general of Tang, Li Baoyu, by unknown artist

"Li Baoyu (Chinese: 李抱玉) (703 – April 15, 777), né An Chongzhang (安重璋), known for some time as An Baoyu (安抱玉), formally Duke Zhaowu of Liang (涼昭武公), was an ethnic Sogdian general of the Chinese Tang Dynasty. He was known for his contributions to Tang during the Anshi Rebellion and for his subsequent defense of the western border against Tufan.

An Chongzhang was born in 703, during the reign of Wu Zetian. His family was originally from Parthia but had lived for generations in the Hexi region, and his great-grandfather An Xinggui (安興貴) was a contributor to Tang Dynasty's establishment, having overthrown one of the contenders for supremacy during the transition from Sui to Tang, Li Gui the Emperor of Liang and united Li Gui's Liang state to Tang. The An family was known for its capability in tending horses, and a number of An family members moved to the region around the Tang capital Chang'an and became students of literature, having intermarried with scholar-bureaucratic families. An Chongzhang, however, grew up in the western regions and was capable in horsemanship and archery. He started serving in the military early in his life, and was said to be full of tactics, careful, and faithful. Toward the end of the Tianbao era (742–756) of Wu Zetian's grandson Emperor Xuanzong, for An Chongzhang's accomplishments in the army, Emperor Xuanzong bestowed on him a new name—Baoyu (meaning, "one who holds jade"). At the time that the general An Lushan rebelled at Fanyang (范陽, in modern Beijing) in 755 and soon established a new state of Yan, An Baoyu was defending Nanyang (南陽). When An Lushan sent messengers to try to persuade him to submit to Yan, he killed An Lushan's messengers."

-taken from Wikipedia

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Statue of Yang Guifei at Huaqing Pool 20th-21st C. CE

"The waters of the [Huaqing pool] hot springs were smooth, and washed over her pale white skin.

The palace maids helped her to leave the pool, because she was too delicate and lacked strength.

She had dark black hair, and the face of a flower, with golden jewelry dangling from her hair.

The sound of the war drums from Yuyang began to shake the earth,

And broke the spell of the Song of rainbow skirts and feather robes.

Smoke and dust descended upon the nine layered watchtowers of the imperial palace,

Traveling more than one hundred li from the western gate of the capital.

The six armies of the emperor refused to advance any further, so the emperor was left without a choice,

The writhing fair maiden, whose long and slender eyebrows resembled the feathery feelers of a moth, died in front of the horses.

Her ornate headdress fell to the ground, and nobody picked it up;

Then her kingfisher hair ornament, her gold sparrow hairpin and her jade hair clasp.

His Majesty covered his face, for he could not save her.

Looking back, he saw a stream of blood and tears mixing together."

-Composed by Bai Juyi in the year 806, The Song of Everlasting Regret (or Sorrow) details the events surrounding the death of the lady Yang Guifei during the Anshi [An-Lushan] Rebellion in 755.

#chinese art#chinese history#tang dynasty#ancient history#ancient china#history#literature#poems and poetry#art#antiquities#sculpture#statue#ancient literature

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yang Guifei by Uemura Tsune 1922. Shohaku Art Museum, Nara, Japan.

Yang Guifei was one of the Four Beauties of China. She was also one of the victims of the era of the An Lushan rebellion, an eight year civil war that radically transformed China from a tolerant nation to an anti-foreigner one. An Lushan was a Turkic rebel that had served as a general in Tang China. He bore a Sogdian name, likely due to childhood adoption by a Sogdian step-father that had wed his Turkic mother from the elite Ashide clan. He was also adopted by Chinese consort Yang Guifei. Though, because Yang Guifei's cousin feuded with An Lushan prior to his rebellion the Tang emperor's soldiers sought her execution. They accused her cousin of causing An Lushan to rebel and also accused him of treason via conspiracy with the Tibetans. The Tang emperor sat idle while the soldiers killed his favorite consort, fearful they would depose him if he defended her too fiercely. Her family was also killed, regardless of their innocence:

"When tourists go to Huaqing Springs in Xi’an today, they can bathe in hot water as she allegedly did when the aging Emperor first saw her among the court women. She is said to have formed a friendship with An Lushan, who became a general of Chinese troops despite his Central Asian origins; she may have even adopted An Lushan as a son. Both Yang Guifei and An Lushan are described as dancing the “whirl,” a Central Asian dance which can be seen in pictures of the Tang court preserved in Dunhuang’s caves on the Silk Road. The Emperor is believed to have been so in love with Yang Guifei, he neglected his duties. The location of Yang’s death is as famous as that of her bath; guidebooks will tell you exactly the location of Ma Lei Station, the place where she was throttled, hanged, or forced to commit suicide by the Emperor’s disgruntled associates." (taken from Columbia.edu)

"In this tense situation, soldiers of the imperial guard declared that Yang Guozhong was planning treason in collaboration with the Tibetan emissaries. They killed Yang Guozhong, his son Yang Xuan (楊暄), Consort Yang's sisters, the ladies of Han and Qin, and Wei Fangjin. (Wei Jiansu was severely injured and nearly killed, but was spared at the last moment.) Yang Guozhong's wife Pei Rou (裴柔) and his son Yang Xi (楊晞), along with Consort Yang's sister, the Lady of Guo, and her son Pei Hui (裴徽) tried to flee, but were killed. The soldiers then surrounded Emperor Xuanzong's pavilion and refused to leave, even after the Emperor came out to comfort them and ordered them to disperse. Emperor Xuanzong then sent Gao Lishi to ask General Chen Xuanli for his advice. Chen's reply was to urge the Emperor to put Consort Yang to death." (taken from Wikipedia)

#ancient china#tang dynasty#chinese history#japanese art#ancient history#history#art#paintings#museums

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chinese woman in traditional costume from the Tang Dynasty 618-907 CE

#chinese art#tang dynasty#ancient china#antiquities#ancient art#ancient history#art#statue#sculpture#history

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tang Dynasty figurine of a Sogdian man 7th C. CE (above). Drawings of Sogdian costumes (below).

#sogdiana#ancient china#museums#statue#sculpture#ancient history#history#antiquities#art#ancient art#tang dynasty#indo european

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

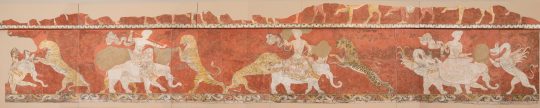

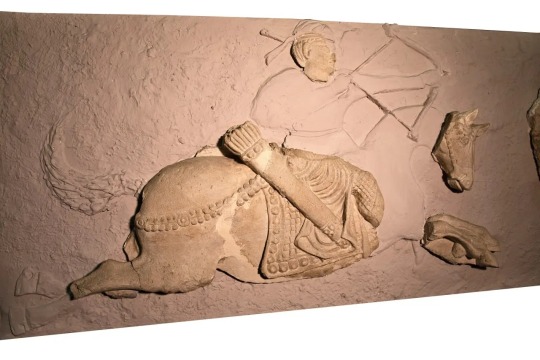

Varakhsha, the Red Hall and other artworks, 6th-8th C. CE

"Varakhsha, also Varasha or Varahsha, was an ancient city in the Bukhara oasis in Sogdia, founded in the 1st century BCE. It is located 39 kilometers to the northwest of Bukhara. Varakhsha was the capital of the Sogdian dynasty of the kings of Bukhara, the Bukhar Khudahs. It ultimately never recovered from the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana.

Beautiful murals have been recovered from the palace area, dated to the 8th century CE. They show a king and his retinue riding elephants and fighting tigers and monstruous beasts."

-taken from Wikipedia

#sogdiana#ancient history#history#antiquities#art#museums#ancient art#fresco#wall murals#pagan#paganism#statue#sculpture

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

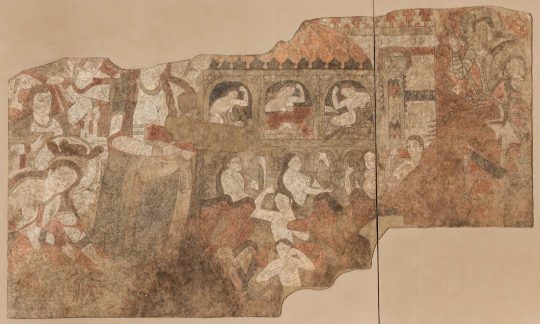

Panjakent Mural - The Blue Hall - Rustam Cycle, circa 740 CE. More images on my blog, link at bottom.

"Contrary to what one might expect, the impressive set of wall paintings known as the “Rustam Cycle” was not located in the hall of a royal palace, but in a house of average size in Panjikent, a small town sixty kilometers east of Samarkand . This painting cycle stands out among other excavated examples for its exceptionally well-preserved (and now, well-restored) murals, which can be dated to about 740. It is also, ironically, the last of the magnificent cycles to be painted at Panjikent; Fig. 1. The city’s ruler, Devastich, was killed in 722 and the city itself subjected to punitive Arab incursions. Despite this artwork and other evidence of Panjikenters resuming their way of life, the city was finally abandoned after the 770s.

Discovered in 1956–57 by archaeologist Boris J. Stavisky, the Rustam Cycle is the most famous painted hall of Panjikent. Named after its main figure, Rustam, a major hero in the great Iranian epic the Shahnameh [“Book of Kings”], it is typical of narrative cycles found at Panjikent as well as other Sogdian cities, such as Afrasiab and Varakhsha . Episodes are organized into different registers, each running horizontally along the length of the walls. Here, the two main registers contain the stories of Rustam’s exploits and are set between a lower tier, depicting scenes from fables and moral tales, and an upper tier, illustrating a religious subject, perhaps related to a family cult.

Two fragments of the Rustam story written in Sogdian have survived: one kept in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the other in the British Library. Dated to the 9th century, they predate by 200 years the first complete version of the Shahnameh written in Persian by the poet Firdowsi."

-The Smithsonian, Julie Bellemare and Judith A. Lerner

#sogdiana#ancient history#history#pagan#antiquities#art#museums#frescoes#ancient art#paganism#wall murals#muralart#mural#ancient

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

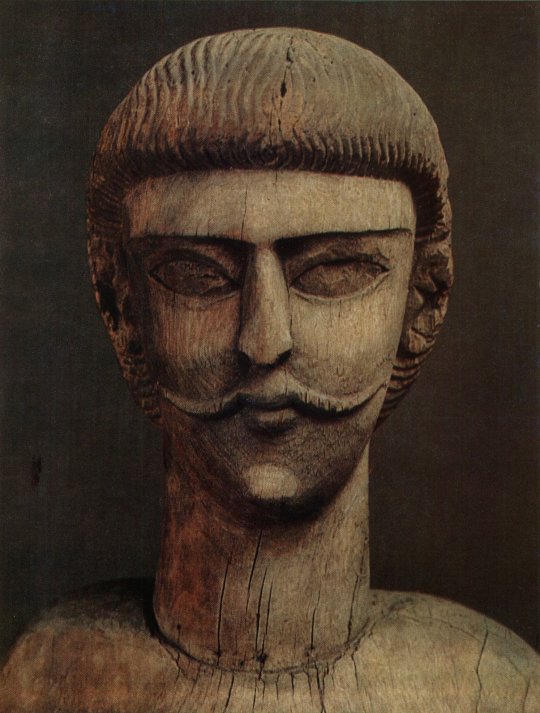

Sogdian wooden idol from Kuh-i-Surkh (Tajikistan) 5th-8th C. CE

"Head of a Sogdian carved wooden idol, found in a cave at Kuh-i-Surkh, Tajikistan. The idol was originally adorned with clothing, jewelry, a diadem, a sceptre, and an incense burner, and must have been hidden in a cave after the Arab conquest. In its heyday, the idol would have worn a crown, a long robe, boots, and carried a sceptre and a censer. At his feet were gifts donated by worshippers - swords, daggers, jewellery, armour, among other things."

-taken from Nadeem - Eran ud Turan's twitter

#sogdiana#ancient history#history#antiquities#art#sculpture#statue#museums#pagan#paganism#woodworking#woodcarving#asian art#indo european

245 notes

·

View notes

Text

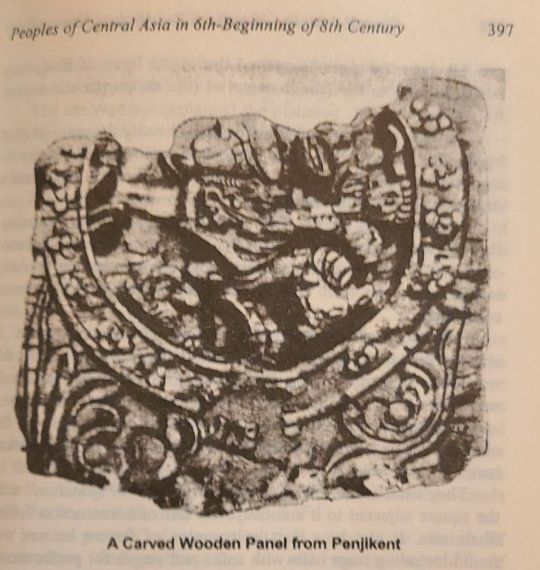

Art from the Sogdian city of Penjakent 5th-8th C. CE. The 3 people in the triple crescent crown may be Hephthalites. A lot more images on my blogspot, link below.

"The Sogdians’ keen interest in depicting the world around them (evidenced by the Hall of the Ambassadors at Afrasiab) and the mythological and supernatural worlds (in many of the Panjikent paintings just discussed) extended into portraying their own world. They did not, as Frantz Grenet points out, represent their mercantile activities, a major source of their wealth, but instead chose to show their enjoyment of it, such as the scenes of banqueting at Panjikent. In these paintings we see how the Sogdians saw themselves.

Chinese representations of Sogdians caricatured them (especially in grooms, musicians, and others of lower status) as having large noses and round eyes, and being heavy-set and generally comical or “barbaric” in appearance. In contrast, the Sogdians’ depictions of themselves show people with fine features—the men (unless rulers or nobles) usually clean-shaven, the women oval-faced and sloe-eyed."

-taken from The Smithsonian

#sogdiana#ancient history#antiquities#history#art#paintings#museums#pagan#paganism#hephthalites#ancient art#medieval art#middle ages#goddess#archaeology

281 notes

·

View notes