#Palooka 1934

Text

The Power Broker

Above: Robert Moses in 1939 with a model of his proposed Battery Bridge Park Reconstruction; at right, 1934 Bryant Park renovation, view to the south on 6th Avenue from 42nd Street. (Wikipedia/NYC Parks Department)

The title for this entry comes from Robert Caro’s landmark 1974 biography of Robert Moses, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, which questioned the benefit of…

View On WordPress

#Abner Dean#Alan Dunn#Daniel &039;Alain&039; Brustlein#Ernest Gruening#Garrett Price#Helen Hokinson#Henry Anton#James Thurber#Jimmy Durante#John Mosher#Lupe Velez#Milton MacKaye#Palooka 1934#Peter Arno#Robert Benchley#Robert Moses

0 notes

Text

Lupe Vélez-Stewart Erwin-Jimmy Durante "Palooka" 1934, de Benjamin Stoloff.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

crossword puzzles always end up giving you the most random, most useless knowledge. like yes, thank you, i always wondered who played palooka in the 1934 film "palooka"

#stuart erwin#btw#in case you were wondering#i wasn't#cruciverbalism#crossword#crosswords#crossword puzzles#fun facts#i guess#i hate tagging#shitpost

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lupe Vélez (born María Guadalupe Villalobos Vélez; July 18, 1908 – December 14, 1944) was a Mexican actress, dancer and singer during the "Golden Age" of Hollywood films.

Vélez began her career as a performer in Mexican vaudeville in the early 1920s. After moving to the United States, she made her first film appearance in a short in 1927. By the end of the decade, she was acting in full-length silent films and had progressed to leading roles in The Gaucho (1927), Lady of the Pavements (1928) and Wolf Song (1929), among others. Vélez then made the transition to sound films without difficulty. She was one of the first successful Latin-American actresses in Hollywood. During the 1930s, her well-known explosive screen persona was exploited in several successful comedic films like Hot Pepper (1933), Strictly Dynamite (1934) and Hollywood Party (1934). In the 1940s, Vélez's popularity peaked after appearing as Carmelita Fuentes in eight Mexican Spitfire films, a series created to capitalize on Vélez's well-documented fiery personality.

Nicknamed The Mexican Spitfire by the media, Vélez's personal life was as colorful as her screen persona. She had several highly publicized romances with Hollywood actors and a stormy marriage with Johnny Weissmuller. In December 1944, Vélez died of an intentional overdose of the barbiturate drug Seconal. Her death and the circumstances surrounding it have been the subject of speculation and controversy.

Vélez was born in the city of San Luis Potosí in Mexico, the daughter of Jacobo Villalobos Reyes, a colonel in the armed forces of the dictator Porfirio Diaz, and his wife Josefina Vélez, an opera singer according to some sources, or vaudeville singer according to others. She was one of five children; she had three sisters: Mercedes, Reina and Josefina and a brother, Emigdio. According to Vélez's second cousin, the Villalobos family were considered prominent in San Luis Potosí and most of the male family members were college educated. The family was also financially comfortable and lived in a large home.

At the age of 13, her parents sent her to study at Our Lady of the Lake (now Our Lady of the Lake University) in San Antonio, Texas. It was at Our Lady of the Lake that Vélez learned to speak English and began to dance. She later admitted that she liked dance class, but was otherwise a poor student.

Vélez began her career in Mexican revues in the early 1920s. She initially performed under her paternal surname (see Hispanic American naming customs) of Villalobos, but after her father returned home from the war (he did not die in combat as some sources state), he was outraged that his daughter had decided to become a stage performer. She chose her maternal surname Vélez as her stage name. Their mother introduced Vélez and her sister Josefina to the popular Spanish Mexican vedette María Conesa, "La Gatita Blanca". Vélez debuted in a show led by Conesa, where she sang "Oh Charley, My Boy" and danced the shimmy.[6] In 1924, Aurelio Campos, a young pianist and friend of the Vélez sisters, recommended Vélez to stage producers Carlos Ortega and Manuel Castro. Ortega and Castro were preparing a season revue at the Regis Theatre, and hired Vélez to join the company in March 1925. Later that year, Vélez starred in the revues Mexican Rataplan and ¡No lo tapes! (both parodies of the Bataclan's shows in Paris). Her suggestive singing and provocative dancing was a hit with audiences, and she soon established herself as one of the main stars of vaudeville in Mexico. After a year and a half, Vélez left the revue after the manager refused to give her a raise. She then joined the Teatro Principal, but was fired after three months due to her "feisty attitude". Vélez was quickly hired by the Teatro Lirico, where her salary rose to 100 pesos a day.

Vélez, whose volatile and spirited personality and feuds with other performers were often covered by the Mexican press, also honed her ability for garnering publicity. Her most bitter rivals included the Mexican vedettes Celia Padilla, Celia Montalván, and Delia Magaña. Called La Niña Lupe because of her youth, Vélez soon established herself as one of the main stars of vaudeville in Mexico. Among her admirers were notable Mexican poets and writers like José Gorostiza and Renato Leduc.

In 1926, Frank A. Woodyard, an American who had seen Vélez perform, recommended her to stage director Richard Bennett (the father of actresses Joan and Constance Bennett). Bennett was looking for an actress to portray a Mexican cantina singer in his upcoming play The Dove. He sent Vélez a telegram inviting her to Los Angeles to appear in the play. Vélez had been planning to go to Cuba to perform, but quickly changed her plans and traveled to Los Angeles. However, upon arrival, she discovered that she had been replaced by another actress.

While in Los Angeles, she met the comedian Fanny Brice. Brice was taken with Vélez and later said she had never met a more fascinating personality. She promoted Vélez's career as a dancer and recommended her to Flo Ziegfeld, who hired her to perform in New York City. While Vélez was preparing to leave Los Angeles, she received a call from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer producer Harry Rapf, who offered her a screen test. Producer and director Hal Roach saw Vélez's screen test and hired her for a small role in the comic Laurel and Hardy short Sailors, Beware!.

After her debut in the short film Sailors, Beware!, Vélez appeared in the Hal Roach short, What Women Did for Me, opposite Charley Chase. Later that year, she did a screen test for the upcoming Douglas Fairbanks full length film The Gaucho. Fairbanks was impressed by Vélez and he quickly signed her to a contract. Upon its release in 1927, The Gaucho was a hit and critics were duly impressed with Vélez's ability to hold her own alongside Fairbanks, who was well known for his spirited acting and impressive stunts.

Vélez made her second major film, Stand and Deliver (1928), directed by Cecil B. DeMille. That same year, she was named one of the WAMPAS Baby Stars. In 1929, Vélez appeared in Lady of the Pavements, directed by D. W. Griffith and Where East Is East, playing a young Chinese woman. In the western film Wolf Song directed by Victor Fleming, she appears alongside Gary Cooper. As she was regularly cast as "exotic" or "ethnic" women that were volatile and hot tempered, gossip columnists took to referring to Vélez as "Mexican Hurricane", "The Mexican Wildcat", "The Mexican Madcap", "Whoopee Lupe" and "The Hot Tamale".

By 1929, the film industry was transitioning from silents to sound films. Several stars of the era saw their careers abruptly end due to heavy accents or voices that recorded poorly. Studio executives predicted that Vélez's accent would likely hamper her ability to make the transition. That idea was dispelled after she appeared in her first all-talking picture in 1929, the Rin Tin Tin vehicle, Tiger Rose. The film was a hit and Vélez's sound career was established.

With the arrival of talkies, Vélez appeared in a series of Pre-Code films like Hell Harbor (directed by Henry King), The Storm (1930, directed by William Wyler), and the crime drama East Is West opposite Edward G. Robinson (1930). In 1931, she appeared in her second film for Cecil B. DeMille, Squaw Man, opposite Warner Baxter, and in Resurrection, directed by Edwin Carewe. In 1932, Vélez filmed The Cuban Love Song (1931), with the popular singer Lawrence Tibbett. That same year, she had a supporting role in Kongo (a sound remake of West of Zanzibar), with Walter Huston. She also starred in Spanish-language versions of some of her movies produced by the Universal Studios like Resurrección (1931, the Spanish version of Resurrection), and Hombres en mi vida (1932, the Spanish version of Men in Her Life). Vélez soon found her niche in comedy, playing beautiful, but volatile, characters.

In February 1932, Vélez took a break from her film career and traveled to New York City where she was signed by Broadway impresario Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr. to take over the role of "Conchita" in the musical revue Hot-Cha!. The show also starred Bert Lahr, Eleanor Powell and Buddy Rogers.

In 1933, Vélez appeared in the films The Half-Naked Truth with Lee Tracy and Hot Pepper, with Victor McLaglen and Edmund Lowe. Later that year, she returned to Broadway where she starred opposite Jimmy Durante in the musical revue Strike Me Pink. In 1934, she filmed Palooka and Strictly Dynamite (both also with Durante). That same year, Vélez was cast as "Slim Girl" in Laughing Boy with Ramón Novarro. The film was quietly released and largely ignored. The few reviews it received panned the film, but praised Vélez's performance. She had more success with her brief appearance in the star packed film Hollywood Party, where she has a magnificent comic routine with Laurel and Hardy. Although Vélez was a popular actress, RKO Pictures did not renew her contract in 1934. Over the next few years, Vélez worked for various studios as a freelance actress; she also spent two years in England where she filmed The Morals of Marcus and Gypsy Melody (both 1936). She returned to Los Angeles the following year where she appeared in the final part of the Wheeler & Woolsey comedy High Flyers (1937).

Vélez last Broadway performance was in the 1938 musical You Never Know, by Cole Porter. The show received poor reviews from critics, but received a large amount of publicity due to the feud between Vélez and fellow cast member Libby Holman. Holman was also irritated by the attention Vélez garnered from the show with her impressions of several actresses including Gloria Swanson, Katharine Hepburn and Shirley Temple. The feud came to a head during a performance in New Haven, Connecticut after Vélez punched Holman in between curtain calls and gave her a black eye. The feud effectively ended the show.

Upon her return to Mexico City in 1938 to star in her first Mexican film, Vélez was greeted by ten thousand fans. The film La Zandunga directed by Fernando de Fuentes, co-starring Mexican actor Arturo de Córdova, was a critical and financial success and Vélez was slated to appear in four more Mexican films. She instead returned to Los Angeles and went back to work for RKO Pictures.

In 1939, Vélez was cast opposite Leon Errol and Donald Woods in a B-comedy, The Girl from Mexico. Despite being a B film, it was a hit with audiences and RKO re-teamed her with Errol and Wood for a sequel, Mexican Spitfire. That film was also a success and led to a series of Spitfire films (eight in all). In the series, Vélez portrays "Carmelita Lindsay", a temperamental yet friendly Mexican singer married to Dennis "Denny" Lindsay (Woods), an elegant American gentleman.[26] The Spitfire films rejuvenated Vélez's career. Moreover, they were films in which a Latina headlined for eight movies straight –a true rarity.

In addition to the Spitfire series, she was cast in another musical and comedy features for RKO, Universal Pictures, and Columbia Pictures. Some of these films were Six Lessons from Madame La Zonga (1941), Playmates (1941), opposite John Barrymore, and Redhead from Manhattan (1943). In 1943, the final film in the Spitfire series, Mexican Spitfire's Blessed Event, was released. By that time, the novelty of the series had begun to wane.

Vélez co-starred with Eddie Albert in a 1943 romantic comedy, Ladies' Day, about an actress and a baseball player. In 1944, Vélez returned to Mexico to star in an adaptation of Émile Zola's novel Nana, which was well-received. It would be her final film. After filming wrapped, Vélez returned to Los Angeles and began preparing for another stage role in New York.

On the evening of December 13, 1944, Vélez dined with her two friends, the silent film star Estelle Taylor and Venita Oakie. In the early morning hours of December 14, Vélez retired to her bedroom, where she consumed 75 Seconal pills and a glass of brandy. Her secretary, Beulah Kinder, found the actress's body on her bed later that morning. A suicide note addressed to Harald Ramond was found nearby. It read:

To Harald, May God forgive you and forgive me too, but I prefer to take my life away and our baby's before I bring him with shame or killing him. – Lupe.

On the back of the note, Vélez wrote:

How could you, Harald, fake such a great love for me and our baby when all the time, you didn't want us? I see no other way out for me, so goodbye, and good luck to you, Love Lupe.[

The day after Vélez's death, Harald Ramond told the press that he was "so confused" by Vélez's suicide, and claimed that even though the two had broken up, he had agreed to marry Vélez.[33] He admitted that he once asked Vélez to sign an agreement stating that he was only marrying her to "give the baby a name", but claimed he only did so because he and Vélez had had a fight, and he was in a "terrible temper". Actress Estelle Taylor, who was with Vélez from 9:00 the previous night until 3:30 the morning Vélez died, told the press that Vélez had told her of her pregnancy, but said she would rather kill herself than have an abortion (Vélez was a devout Roman Catholic). Beulah Kinder, Vélez's secretary, later told investigators that after Vélez broke off the relationship with Ramond, she planned to go to Mexico to have her baby. Kinder said Vélez soon changed her mind after concluding that Ramond "faked" the relationship and considered having an abortion.

The day after Vélez's death, the Los Angeles County coroner requested that an inquest be opened to investigate the circumstances surrounding her death. On December 16, the coroner dropped the request, after determining that Vélez had written the notes, and that she had intended to kill herself. On December 22, a funeral for Vélez was held at the mortuary at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Los Angeles. Among the pallbearers were Vélez's ex-husband, Johnny Weissmuller, and actor Gilbert Roland. After the service, Vélez's body was sent by train to Mexico City, where a second service was held on December 27. Her body was then interred at Panteón Civil de Dolores Cemetery.

Despite the coroner's ruling that Vélez committed suicide to avoid the shame of bearing an illegitimate child, some authors have theorized that this was not entirely true.

In the book From Bananas to Buttocks: The Latina Body in Popular Film and Culture, Rosa-Linda Fregoso wrote that Vélez was known for her defiance of contemporary moral convention, and that it seems unlikely that she could not have reconciled having a child out of wedlock. Fregoso believes that in the final year of her life, Vélez exhibited signs of extreme mania and depression. Fregoso goes on to speculate that Vélez's death may have been the result of an untreated mental illness such as bipolar disorder.

Robert Slatzer (who later claimed to have been secretly married to Marilyn Monroe) claimed that a few weeks before Vélez's death, he interviewed her at her home and she confided in him that she was pregnant with Gary Cooper's child (by that time, Cooper was married to socialite Veronica "Rocky" Balfe). According to Slatzer, Vélez said that Cooper refused to acknowledge the child, believing that Harald Ramond was the father. After Vélez died, Slatzer said he asked Cooper about the situation and Cooper confirmed that it was possible he might have been the father. Slatzer further claimed that he also interviewed Clara Bow (who had also dated Cooper in the 1920s), who revealed that shortly before Vélez's death, Cooper called her and screamed that he was going to kill Harald Ramond for impregnating Vélez. Slazter claimed that Bow told him that she never believed Vélez's baby was fathered by Ramond, and that she was convinced that Vélez had attempted to get Ramond to marry her to protect Cooper's reputation. Biographer Michelle Vogel speculated that if Cooper was the father, his rejection of Vélez and their child coupled with the idea of having to raise a child alone may have sent Vélez "over the edge".

In the 2002 book Tarzan, My Father Johnny Weissmuller Jr recounted the events surrounding Vélez's death as a mystery caused by an attempt to "put a lid" on what happened. It states her housekeeper discovered her body and called Bo Roos, Vélez's business manager, who called his friend and Beverly Hills Police Chief Anderson to the scene. The book states after Vélez arranged to meet Ramond, decorated her room and dressed in a negligee, her ingestion of Seconal was either to calm her nerves to meet him or a failed dramatic gesture to scare him. The book also suggested the baby was fathered possibly by Cooper not Ramond.

Vélez's death was recounted in the 1959 book Hollywood Babylon by Kenneth Anger and has become urban legend. In his telling, Vélez planned to stage a beautiful suicide scene atop her satin bed, but the Seconal did not mix well with the "Mexi-Spice Last Supper" she had eaten earlier that evening. As a result, she became violently ill, stumbled to the bathroom to vomit, slipped on the bathroom floor tile and fell head first into the toilet, where she subsequently drowned. Anger claimed that Vélez's "chambermaid" Juanita found her the next morning. Despite the fact that his version of events contradicts published reports and the official ruling, his story is often repeated as fact or for comedic effect – it was recounted in the pilot episode of the television comedy series Frasier, and also referenced in an episode of the cartoon The Simpsons. Vélez's biographer, Michelle Vogel, points out that it would have been "virtually impossible" for Vélez to have "stumbled to the bathroom" or even get off her bed after having consumed such a large amount of Seconal. Seconal, a barbiturate, is noted for being fast acting even in small doses and Vélez's death was likely instantaneous. Her death certificate lists "Seconal poisoning" due to "ingestion of Seconal" as the cause of death, not drowning. Further, there was also no evidence to suggest Vélez had vomited.

Throughout her career, Vélez's onscreen persona of a hot tempered, lusty "wild" woman was closely tied to her off screen personality. The press often referred to her by such names as "The Mexican Spitfire", "The Mexican It girl" and "The Mexican Kitten". Publicly promoted with the "Whoopee Lupe" persona that tried to define her, she dismissed the idea that she was uncontrollably wild. In an interview, she said:

What I attribute my success?, I think, simply, because I'm different. I'm not beautiful, but I have beautiful eyes and know exactly what to do with them. Although the public thinks that I'm a very wild girl. Actually I'm not. I'm just me, Lupe Vélez, simple and natural Lupe. If I'm happy, I dance and sing and acted like a child. And if something irritates me, I cry and sob. Someone called that 'personality'. The Personality is nothing more than behave with others as you really are. If I tried to look and act like Norma Talmadge, the great dramatic actress, or like Corinne Griffith, the aristocrat of the movies, or like Mary Pickford, the sweet and gentle Mary, I would be nothing more than an imitation. I just want to be myself: Lupe Vélez.

Vélez's off-screen behavior blurred the line between her onscreen persona and her real personality. After her death, journalist Bob Thomas recalled that Vélez was a "lively part of the Hollywood scene" who wore loud clothing and made as much noise as possible. She attended boxing matches every Friday night at the Hollywood Legion Stadium and would stand on her ringside seat and scream at the fighters.

Vélez's temper and jealousy in her often tempestuous romantic relationships were well documented and became tabloid fodder, often overshadowing her career. Vélez was straightforward with the press and was regularly contacted by gossip columnists for stories about her romantic exploits. One such incident included Vélez chasing her lover Gary Cooper around with a knife during an argument and cutting him severely enough to require stitches. After their breakup, Vélez attempted to shoot Cooper while he boarded a train. During her marriage to actor Johnny Weissmuller, stories of their frequent physical fights were regularly reported in the press. Vélez reportedly inflicted scratches, bruises, and love-bites on Weissmuller during their fights and "passionate love-making".

Vélez often targeted fellow actresses whom she deemed as rivals, professionally or otherwise, a habit which began back in her vaudeville days and continued in films. Vélez's image was that of a wild, highly sexualized woman who spoke her mind and was not considered a "lady", while fellow Mexican actress Dolores del Río projected herself as sensual, but classy and restrained, often hailing from aristocratic roots. Vélez hated del Río, and called her "bird of bad omen". Del Río was terrified to meet her in public places. When this happened, Vélez was scathing and aggressive. Vélez openly mimicked del Río, ironically making fun of her elegance. Vélez also disliked Marlene Dietrich whom she suspected of having an affair with Gary Cooper while filming Morocco in 1930. Her rivalries with Jetta Goudal, Lilyan Tashman and Libby Holman were also well documented. In retaliation, Vélez would perform scathing impersonations of the women she disliked at Hollywood parties. Also notable are her imitations of figures such as Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Fanny Brice, Gloria Swanson, Katharine Hepburn, Simone Simon, and Shirley Temple.

Vélez was involved in several highly publicized and often stormy relationships. Upon arriving in Los Angeles, she was linked to actors Tom Mix, Charlie Chaplin and Clark Gable. Her first long-term, high-profile relationship was with Gary Cooper. Vélez and Cooper met while filming 1929s Wolf Song and began a two-year relationship that was passionate and often stormy. When angered, Vélez was reported to have physically assaulted Cooper. Cooper eventually ended the relationship in mid-1931, at the behest of his mother Alice who after meeting her, strongly disapproved of Vélez.[51] With plans to marry him gone, she spoke to the press in 1931: "I turned Cooper down because his parents didn't want me to marry him and because the studio thought it would injure his career. Now its over, I'm glad I feel so free ... I must be free. I know men to well they are all the same, no? If you love them they want to be boss. I will never have a boss." The rocky relationship had taken its toll on Cooper, who had lost 45 pounds and was suffering from nervous exhaustion. Paramount Pictures ordered him to take a vacation to recuperate and while he was boarding the train, Vélez showed up at the station and fired a pistol at him.

After her breakup with Cooper, Vélez began a short-lived relationship with actor John Gilbert. They began dating in late 1931, while Gilbert was separated from his third wife Ina Claire. Rumors of an engagement were fueled by the couple, but Gilbert ended the relationship in early 1932, and attempted to reconcile with Claire.

Shortly thereafter, Vélez met Tarzan actor Johnny Weissmuller while the two were in New York. They dated off and on when they returned to Los Angeles, while Vélez also dated actor Errol Flynn.[63] On October 8, 1933, Vélez and Weissmuller were married in Las Vegas. There were reports of domestic violence and public fights. In July 1934, after ten months of marriage, Vélez filed for divorce citing "cruelty". She withdrew the petition a week later after reconciling with Weissmuller. On January 3, 1935, she filed for divorce a second time and was granted an interlocutory decree. That decree was dismissed when the couple reconciled a month later. In August 1938, Vélez filed for divorce for a third time, again charging Weissmuller with cruelty. Their divorce was finalized in August 1939.

After the divorce became final, Vélez began dating polo player Guinn "Big Boy" Williams in late 1940. The couple were engaged, but never married. In late 1941, she became involved with author Erich Maria Remarque. Actress Luise Rainer recalled that Remarque told her "with the greatest of glee" that he found Vélez's volatility wonderful when he recounted to her an occasion where Vélez became so angry with him that she took her shoe off and hit him with it. After dating Remarque, Vélez was linked to boxers Jack Johnson and Jack Dempsey.

In 1943, Vélez began an affair with her La Zandunga co-star Arturo de Córdova. De Córdova had recently moved to Los Angeles after signing with Paramount. Despite the fact that de Córdova was married to Mexican actress Enna Arana with whom he had four children, Vélez granted an interview to gossip columnist Louella Parsons in September 1943 and announced that the two were engaged. She told Parsons that she planned to retire after marrying de Córdova to "cook ... and keep house". Vélez ended the engagement in early 1944, after de Córdova's wife refused to give him a divorce.

Vélez then met and began dating a struggling young Austrian actor named Harald Maresch, whose stage name was Harald Ramond. In September 1944, she discovered she was pregnant with Ramond's child. She announced their engagement in late November 1944. On December 10, four days before her death, Vélez announced she had ended the engagement and kicked Ramond out of her home.

For her contribution to the motion picture industry, Lupe Vélez has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, at 6927 Hollywood Boulevard.

Lupe Vélez has a sculpture in her honor located in San Luis Potosí, Mexico. The sculpture was done by artist Emilio Borjas in 2017 and is located in the Garden of San Sebastian, the neighborhood where the actress was born.

#lupe velez#silent era#silent hollywood#silent movie stars#golden age of hollywood#classic hollywood#classic movie stars#1920s hollywood#1930s hollywood#1940s hollywood

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lupe Vélez (born María Guadalupe Villalobos Vélez; July 18, 1908 – December 14, 1944) was a Mexican actress, dancer and singer during the "Golden Age" of Hollywood films.

Vélez began her career as a performer in Mexican vaudeville in the early 1920s. After moving to the United States, she made her first film appearance in a short in 1927. By the end of the decade, she was acting in full-length silent films and had progressed to leading roles in The Gaucho (1927), Lady of the Pavements (1928) and Wolf Song (1929), among others. Vélez then made the transition to sound films without difficulty. She was one of the first successful Latin-American actresses in Hollywood. During the 1930s, her well-known explosive screen persona was exploited in several successful comedic films like Hot Pepper (1933), Strictly Dynamite (1934) and Hollywood Party (1934). In the 1940s, Vélez's popularity peaked after appearing as Carmelita Fuentes in eight Mexican Spitfire films, a series created to capitalize on Vélez's well-documented fiery personality.

Nicknamed The Mexican Spitfire by the media, Vélez's personal life was as colorful as her screen persona. She had several highly publicized romances with Hollywood actors and a stormy marriage with Johnny Weissmuller. In December 1944, Vélez died of an intentional overdose of the barbiturate drug Seconal. Her death and the circumstances surrounding it have been the subject of speculation and controversy.

Vélez was born in the city of San Luis Potosí in Mexico, the daughter of Jacobo Villalobos Reyes, a colonel in the armed forces of the dictator Porfirio Diaz, and his wife Josefina Vélez, an opera singer according to some sources, or vaudeville singer according to others. She was one of five children; she had three sisters: Mercedes, Reina and Josefina and a brother, Emigdio. According to Vélez's second cousin, the Villalobos family were considered prominent in San Luis Potosí and most of the male family members were college educated. The family was also financially comfortable and lived in a large home.

At the age of 13, her parents sent her to study at Our Lady of the Lake (now Our Lady of the Lake University) in San Antonio, Texas. It was at Our Lady of the Lake that Vélez learned to speak English and began to dance. She later admitted that she liked dance class, but was otherwise a poor student.

Vélez began her career in Mexican revues in the early 1920s. She initially performed under her paternal surname (see Hispanic American naming customs) of Villalobos, but after her father returned home from the war (he did not die in combat as some sources state), he was outraged that his daughter had decided to become a stage performer. She chose her maternal surname Vélez as her stage name. Their mother introduced Vélez and her sister Josefina to the popular Spanish Mexican vedette María Conesa, "La Gatita Blanca". Vélez debuted in a show led by Conesa, where she sang "Oh Charley, My Boy" and danced the shimmy.[6] In 1924, Aurelio Campos, a young pianist and friend of the Vélez sisters, recommended Vélez to stage producers Carlos Ortega and Manuel Castro. Ortega and Castro were preparing a season revue at the Regis Theatre, and hired Vélez to join the company in March 1925. Later that year, Vélez starred in the revues Mexican Rataplan and ¡No lo tapes! (both parodies of the Bataclan's shows in Paris). Her suggestive singing and provocative dancing was a hit with audiences, and she soon established herself as one of the main stars of vaudeville in Mexico. After a year and a half, Vélez left the revue after the manager refused to give her a raise. She then joined the Teatro Principal, but was fired after three months due to her "feisty attitude". Vélez was quickly hired by the Teatro Lirico, where her salary rose to 100 pesos a day.

Vélez, whose volatile and spirited personality and feuds with other performers were often covered by the Mexican press, also honed her ability for garnering publicity. Her most bitter rivals included the Mexican vedettes Celia Padilla, Celia Montalván, and Delia Magaña. Called La Niña Lupe because of her youth, Vélez soon established herself as one of the main stars of vaudeville in Mexico. Among her admirers were notable Mexican poets and writers like José Gorostiza and Renato Leduc.

In 1926, Frank A. Woodyard, an American who had seen Vélez perform, recommended her to stage director Richard Bennett (the father of actresses Joan and Constance Bennett). Bennett was looking for an actress to portray a Mexican cantina singer in his upcoming play The Dove. He sent Vélez a telegram inviting her to Los Angeles to appear in the play. Vélez had been planning to go to Cuba to perform, but quickly changed her plans and traveled to Los Angeles. However, upon arrival, she discovered that she had been replaced by another actress.

While in Los Angeles, she met the comedian Fanny Brice. Brice was taken with Vélez and later said she had never met a more fascinating personality. She promoted Vélez's career as a dancer and recommended her to Flo Ziegfeld, who hired her to perform in New York City. While Vélez was preparing to leave Los Angeles, she received a call from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer producer Harry Rapf, who offered her a screen test. Producer and director Hal Roach saw Vélez's screen test and hired her for a small role in the comic Laurel and Hardy short Sailors, Beware!.

After her debut in the short film Sailors, Beware!, Vélez appeared in the Hal Roach short, What Women Did for Me, opposite Charley Chase. Later that year, she did a screen test for the upcoming Douglas Fairbanks full length film The Gaucho. Fairbanks was impressed by Vélez and he quickly signed her to a contract. Upon its release in 1927, The Gaucho was a hit and critics were duly impressed with Vélez's ability to hold her own alongside Fairbanks, who was well known for his spirited acting and impressive stunts.

Vélez made her second major film, Stand and Deliver (1928), directed by Cecil B. DeMille. That same year, she was named one of the WAMPAS Baby Stars. In 1929, Vélez appeared in Lady of the Pavements, directed by D. W. Griffith and Where East Is East, playing a young Chinese woman. In the western film Wolf Song directed by Victor Fleming, she appears alongside Gary Cooper. As she was regularly cast as "exotic" or "ethnic" women that were volatile and hot tempered, gossip columnists took to referring to Vélez as "Mexican Hurricane", "The Mexican Wildcat", "The Mexican Madcap", "Whoopee Lupe" and "The Hot Tamale".

By 1929, the film industry was transitioning from silents to sound films. Several stars of the era saw their careers abruptly end due to heavy accents or voices that recorded poorly. Studio executives predicted that Vélez's accent would likely hamper her ability to make the transition. That idea was dispelled after she appeared in her first all-talking picture in 1929, the Rin Tin Tin vehicle, Tiger Rose. The film was a hit and Vélez's sound career was established.

With the arrival of talkies, Vélez appeared in a series of Pre-Code films like Hell Harbor (directed by Henry King), The Storm (1930, directed by William Wyler), and the crime drama East Is West opposite Edward G. Robinson (1930). In 1931, she appeared in her second film for Cecil B. DeMille, Squaw Man, opposite Warner Baxter, and in Resurrection, directed by Edwin Carewe. In 1932, Vélez filmed The Cuban Love Song (1931), with the popular singer Lawrence Tibbett. That same year, she had a supporting role in Kongo (a sound remake of West of Zanzibar), with Walter Huston. She also starred in Spanish-language versions of some of her movies produced by the Universal Studios like Resurrección (1931, the Spanish version of Resurrection), and Hombres en mi vida (1932, the Spanish version of Men in Her Life). Vélez soon found her niche in comedy, playing beautiful, but volatile, characters.

In February 1932, Vélez took a break from her film career and traveled to New York City where she was signed by Broadway impresario Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr. to take over the role of "Conchita" in the musical revue Hot-Cha!. The show also starred Bert Lahr, Eleanor Powell and Buddy Rogers.

In 1933, Vélez appeared in the films The Half-Naked Truth with Lee Tracy and Hot Pepper, with Victor McLaglen and Edmund Lowe. Later that year, she returned to Broadway where she starred opposite Jimmy Durante in the musical revue Strike Me Pink. In 1934, she filmed Palooka and Strictly Dynamite (both also with Durante). That same year, Vélez was cast as "Slim Girl" in Laughing Boy with Ramón Novarro. The film was quietly released and largely ignored. The few reviews it received panned the film, but praised Vélez's performance. She had more success with her brief appearance in the star packed film Hollywood Party, where she has a magnificent comic routine with Laurel and Hardy. Although Vélez was a popular actress, RKO Pictures did not renew her contract in 1934. Over the next few years, Vélez worked for various studios as a freelance actress; she also spent two years in England where she filmed The Morals of Marcus and Gypsy Melody (both 1936). She returned to Los Angeles the following year where she appeared in the final part of the Wheeler & Woolsey comedy High Flyers (1937).

Vélez last Broadway performance was in the 1938 musical You Never Know, by Cole Porter. The show received poor reviews from critics, but received a large amount of publicity due to the feud between Vélez and fellow cast member Libby Holman. Holman was also irritated by the attention Vélez garnered from the show with her impressions of several actresses including Gloria Swanson, Katharine Hepburn and Shirley Temple. The feud came to a head during a performance in New Haven, Connecticut after Vélez punched Holman in between curtain calls and gave her a black eye. The feud effectively ended the show.

Upon her return to Mexico City in 1938 to star in her first Mexican film, Vélez was greeted by ten thousand fans. The film La Zandunga directed by Fernando de Fuentes, co-starring Mexican actor Arturo de Córdova, was a critical and financial success and Vélez was slated to appear in four more Mexican films. She instead returned to Los Angeles and went back to work for RKO Pictures.

In 1939, Vélez was cast opposite Leon Errol and Donald Woods in a B-comedy, The Girl from Mexico. Despite being a B film, it was a hit with audiences and RKO re-teamed her with Errol and Wood for a sequel, Mexican Spitfire. That film was also a success and led to a series of Spitfire films (eight in all). In the series, Vélez portrays "Carmelita Lindsay", a temperamental yet friendly Mexican singer married to Dennis "Denny" Lindsay (Woods), an elegant American gentleman.[26] The Spitfire films rejuvenated Vélez's career. Moreover, they were films in which a Latina headlined for eight movies straight –a true rarity.

In addition to the Spitfire series, she was cast in another musical and comedy features for RKO, Universal Pictures, and Columbia Pictures. Some of these films were Six Lessons from Madame La Zonga (1941), Playmates (1941), opposite John Barrymore, and Redhead from Manhattan (1943). In 1943, the final film in the Spitfire series, Mexican Spitfire's Blessed Event, was released. By that time, the novelty of the series had begun to wane.

Vélez co-starred with Eddie Albert in a 1943 romantic comedy, Ladies' Day, about an actress and a baseball player. In 1944, Vélez returned to Mexico to star in an adaptation of Émile Zola's novel Nana, which was well-received. It would be her final film. After filming wrapped, Vélez returned to Los Angeles and began preparing for another stage role in New York.

On the evening of December 13, 1944, Vélez dined with her two friends, the silent film star Estelle Taylor and Venita Oakie. In the early morning hours of December 14, Vélez retired to her bedroom, where she consumed 75 Seconal pills and a glass of brandy. Her secretary, Beulah Kinder, found the actress's body on her bed later that morning. A suicide note addressed to Harald Ramond was found nearby. It read:

To Harald, May God forgive you and forgive me too, but I prefer to take my life away and our baby's before I bring him with shame or killing him. – Lupe.

On the back of the note, Vélez wrote:

How could you, Harald, fake such a great love for me and our baby when all the time, you didn't want us? I see no other way out for me, so goodbye, and good luck to you, Love Lupe.[

The day after Vélez's death, Harald Ramond told the press that he was "so confused" by Vélez's suicide, and claimed that even though the two had broken up, he had agreed to marry Vélez.[33] He admitted that he once asked Vélez to sign an agreement stating that he was only marrying her to "give the baby a name", but claimed he only did so because he and Vélez had had a fight, and he was in a "terrible temper". Actress Estelle Taylor, who was with Vélez from 9:00 the previous night until 3:30 the morning Vélez died, told the press that Vélez had told her of her pregnancy, but said she would rather kill herself than have an abortion (Vélez was a devout Roman Catholic). Beulah Kinder, Vélez's secretary, later told investigators that after Vélez broke off the relationship with Ramond, she planned to go to Mexico to have her baby. Kinder said Vélez soon changed her mind after concluding that Ramond "faked" the relationship and considered having an abortion.

The day after Vélez's death, the Los Angeles County coroner requested that an inquest be opened to investigate the circumstances surrounding her death. On December 16, the coroner dropped the request, after determining that Vélez had written the notes, and that she had intended to kill herself. On December 22, a funeral for Vélez was held at the mortuary at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Los Angeles. Among the pallbearers were Vélez's ex-husband, Johnny Weissmuller, and actor Gilbert Roland. After the service, Vélez's body was sent by train to Mexico City, where a second service was held on December 27. Her body was then interred at Panteón Civil de Dolores Cemetery.

Despite the coroner's ruling that Vélez committed suicide to avoid the shame of bearing an illegitimate child, some authors have theorized that this was not entirely true.

In the book From Bananas to Buttocks: The Latina Body in Popular Film and Culture, Rosa-Linda Fregoso wrote that Vélez was known for her defiance of contemporary moral convention, and that it seems unlikely that she could not have reconciled having a child out of wedlock. Fregoso believes that in the final year of her life, Vélez exhibited signs of extreme mania and depression. Fregoso goes on to speculate that Vélez's death may have been the result of an untreated mental illness such as bipolar disorder.

Robert Slatzer (who later claimed to have been secretly married to Marilyn Monroe) claimed that a few weeks before Vélez's death, he interviewed her at her home and she confided in him that she was pregnant with Gary Cooper's child (by that time, Cooper was married to socialite Veronica "Rocky" Balfe). According to Slatzer, Vélez said that Cooper refused to acknowledge the child, believing that Harald Ramond was the father. After Vélez died, Slatzer said he asked Cooper about the situation and Cooper confirmed that it was possible he might have been the father. Slatzer further claimed that he also interviewed Clara Bow (who had also dated Cooper in the 1920s), who revealed that shortly before Vélez's death, Cooper called her and screamed that he was going to kill Harald Ramond for impregnating Vélez. Slazter claimed that Bow told him that she never believed Vélez's baby was fathered by Ramond, and that she was convinced that Vélez had attempted to get Ramond to marry her to protect Cooper's reputation. Biographer Michelle Vogel speculated that if Cooper was the father, his rejection of Vélez and their child coupled with the idea of having to raise a child alone may have sent Vélez "over the edge".

In the 2002 book Tarzan, My Father Johnny Weissmuller Jr recounted the events surrounding Vélez's death as a mystery caused by an attempt to "put a lid" on what happened. It states her housekeeper discovered her body and called Bo Roos, Vélez's business manager, who called his friend and Beverly Hills Police Chief Anderson to the scene. The book states after Vélez arranged to meet Ramond, decorated her room and dressed in a negligee, her ingestion of Seconal was either to calm her nerves to meet him or a failed dramatic gesture to scare him. The book also suggested the baby was fathered possibly by Cooper not Ramond.

Vélez's death was recounted in the 1959 book Hollywood Babylon by Kenneth Anger and has become urban legend. In his telling, Vélez planned to stage a beautiful suicide scene atop her satin bed, but the Seconal did not mix well with the "Mexi-Spice Last Supper" she had eaten earlier that evening. As a result, she became violently ill, stumbled to the bathroom to vomit, slipped on the bathroom floor tile and fell head first into the toilet, where she subsequently drowned. Anger claimed that Vélez's "chambermaid" Juanita found her the next morning. Despite the fact that his version of events contradicts published reports and the official ruling, his story is often repeated as fact or for comedic effect – it was recounted in the pilot episode of the television comedy series Frasier, and also referenced in an episode of the cartoon The Simpsons. Vélez's biographer, Michelle Vogel, points out that it would have been "virtually impossible" for Vélez to have "stumbled to the bathroom" or even get off her bed after having consumed such a large amount of Seconal. Seconal, a barbiturate, is noted for being fast acting even in small doses and Vélez's death was likely instantaneous. Her death certificate lists "Seconal poisoning" due to "ingestion of Seconal" as the cause of death, not drowning. Further, there was also no evidence to suggest Vélez had vomited.

Throughout her career, Vélez's onscreen persona of a hot tempered, lusty "wild" woman was closely tied to her off screen personality. The press often referred to her by such names as "The Mexican Spitfire", "The Mexican It girl" and "The Mexican Kitten". Publicly promoted with the "Whoopee Lupe" persona that tried to define her, she dismissed the idea that she was uncontrollably wild. In an interview, she said:

What I attribute my success?, I think, simply, because I'm different. I'm not beautiful, but I have beautiful eyes and know exactly what to do with them. Although the public thinks that I'm a very wild girl. Actually I'm not. I'm just me, Lupe Vélez, simple and natural Lupe. If I'm happy, I dance and sing and acted like a child. And if something irritates me, I cry and sob. Someone called that 'personality'. The Personality is nothing more than behave with others as you really are. If I tried to look and act like Norma Talmadge, the great dramatic actress, or like Corinne Griffith, the aristocrat of the movies, or like Mary Pickford, the sweet and gentle Mary, I would be nothing more than an imitation. I just want to be myself: Lupe Vélez.

Vélez's off-screen behavior blurred the line between her onscreen persona and her real personality. After her death, journalist Bob Thomas recalled that Vélez was a "lively part of the Hollywood scene" who wore loud clothing and made as much noise as possible. She attended boxing matches every Friday night at the Hollywood Legion Stadium and would stand on her ringside seat and scream at the fighters.

Vélez's temper and jealousy in her often tempestuous romantic relationships were well documented and became tabloid fodder, often overshadowing her career. Vélez was straightforward with the press and was regularly contacted by gossip columnists for stories about her romantic exploits. One such incident included Vélez chasing her lover Gary Cooper around with a knife during an argument and cutting him severely enough to require stitches. After their breakup, Vélez attempted to shoot Cooper while he boarded a train. During her marriage to actor Johnny Weissmuller, stories of their frequent physical fights were regularly reported in the press. Vélez reportedly inflicted scratches, bruises, and love-bites on Weissmuller during their fights and "passionate love-making".

Vélez often targeted fellow actresses whom she deemed as rivals, professionally or otherwise, a habit which began back in her vaudeville days and continued in films. Vélez's image was that of a wild, highly sexualized woman who spoke her mind and was not considered a "lady", while fellow Mexican actress Dolores del Río projected herself as sensual, but classy and restrained, often hailing from aristocratic roots. Vélez hated del Río, and called her "bird of bad omen". Del Río was terrified to meet her in public places. When this happened, Vélez was scathing and aggressive. Vélez openly mimicked del Río, ironically making fun of her elegance. Vélez also disliked Marlene Dietrich whom she suspected of having an affair with Gary Cooper while filming Morocco in 1930. Her rivalries with Jetta Goudal, Lilyan Tashman and Libby Holman were also well documented. In retaliation, Vélez would perform scathing impersonations of the women she disliked at Hollywood parties. Also notable are her imitations of figures such as Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Fanny Brice, Gloria Swanson, Katharine Hepburn, Simone Simon, and Shirley Temple.

Vélez was involved in several highly publicized and often stormy relationships. Upon arriving in Los Angeles, she was linked to actors Tom Mix, Charlie Chaplin and Clark Gable. Her first long-term, high-profile relationship was with Gary Cooper. Vélez and Cooper met while filming 1929s Wolf Song and began a two-year relationship that was passionate and often stormy. When angered, Vélez was reported to have physically assaulted Cooper. Cooper eventually ended the relationship in mid-1931, at the behest of his mother Alice who after meeting her, strongly disapproved of Vélez.[51] With plans to marry him gone, she spoke to the press in 1931: "I turned Cooper down because his parents didn't want me to marry him and because the studio thought it would injure his career. Now its over, I'm glad I feel so free ... I must be free. I know men to well they are all the same, no? If you love them they want to be boss. I will never have a boss." The rocky relationship had taken its toll on Cooper, who had lost 45 pounds and was suffering from nervous exhaustion. Paramount Pictures ordered him to take a vacation to recuperate and while he was boarding the train, Vélez showed up at the station and fired a pistol at him.

After her breakup with Cooper, Vélez began a short-lived relationship with actor John Gilbert. They began dating in late 1931, while Gilbert was separated from his third wife Ina Claire. Rumors of an engagement were fueled by the couple, but Gilbert ended the relationship in early 1932, and attempted to reconcile with Claire.

Shortly thereafter, Vélez met Tarzan actor Johnny Weissmuller while the two were in New York. They dated off and on when they returned to Los Angeles, while Vélez also dated actor Errol Flynn.[63] On October 8, 1933, Vélez and Weissmuller were married in Las Vegas. There were reports of domestic violence and public fights. In July 1934, after ten months of marriage, Vélez filed for divorce citing "cruelty". She withdrew the petition a week later after reconciling with Weissmuller. On January 3, 1935, she filed for divorce a second time and was granted an interlocutory decree. That decree was dismissed when the couple reconciled a month later. In August 1938, Vélez filed for divorce for a third time, again charging Weissmuller with cruelty. Their divorce was finalized in August 1939.

After the divorce became final, Vélez began dating polo player Guinn "Big Boy" Williams in late 1940. The couple were engaged, but never married. In late 1941, she became involved with author Erich Maria Remarque. Actress Luise Rainer recalled that Remarque told her "with the greatest of glee" that he found Vélez's volatility wonderful when he recounted to her an occasion where Vélez became so angry with him that she took her shoe off and hit him with it. After dating Remarque, Vélez was linked to boxers Jack Johnson and Jack Dempsey.

In 1943, Vélez began an affair with her La Zandunga co-star Arturo de Córdova. De Córdova had recently moved to Los Angeles after signing with Paramount. Despite the fact that de Córdova was married to Mexican actress Enna Arana with whom he had four children, Vélez granted an interview to gossip columnist Louella Parsons in September 1943 and announced that the two were engaged. She told Parsons that she planned to retire after marrying de Córdova to "cook ... and keep house". Vélez ended the engagement in early 1944, after de Córdova's wife refused to give him a divorce.

Vélez then met and began dating a struggling young Austrian actor named Harald Maresch, whose stage name was Harald Ramond. In September 1944, she discovered she was pregnant with Ramond's child. She announced their engagement in late November 1944. On December 10, four days before her death, Vélez announced she had ended the engagement and kicked Ramond out of her home.

For her contribution to the motion picture industry, Lupe Vélez has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, at 6927 Hollywood Boulevard.

Lupe Vélez has a sculpture in her honor located in San Luis Potosí, Mexico. The sculpture was done by artist Emilio Borjas in 2017 and is located in the Garden of San Sebastian, the neighborhood where the actress was born.

#lupe velez#silent era#silent movie stars#silent hollywood#classic hollywood#golden age of hollywood#classic movie stars#old hollywood#1920s hollywood#1930s hollywood#1940s hollywood

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jews in Comic Books

How American Jews created the comic book industry.

Jews built the comic book industry from the ground up, and the influence of Jewish writers, artists, and editors continues to be felt to this day. But how did Jews come to have such a disproportionate influence on an industry most famous for lantern-jawed demigods clad in colorful tights?

First Comic Books

The story begins in 1933. During that year, the world experienced seismic changes in politics and pop culture. An unemployed Jewish novelty salesman named Maxwell Charles “M.C.” Gaines (née Max Ginzberg) had a brilliant idea: if heenjoyed reading old comic strips like Joe Palooka, Mutt and Jeff, and Hairbredth Harry so much, maybe the rest of America would, too. Thus was born the American comic book, which in its earliest days consisted of reprinted newspaper funnies. Gaines and his colleague Harry L. Wildenberg at Eastern Color Printing soon published February 1934’s Famous Funnies #1, Series 1, the first American retail comic book.

Rival comic book publishers sprang up immediately. However, by the mid-1930s publishers were already starting to exhaust the backlog of daily and Sunday strips that could be reprinted. The easiest way to fill the demand for new comic book features was for publishers to tap writers and artists who couldn’t get work anywhere else, either because they were too young, too inexperienced, or Jewish–in most cases, all three. Advertising agencies had anti-Semitic quotas, and newspaper syndicates only occasionally took on a token Jewish cartoonist like Milt Gross or Rube Goldberg. But the comic book companies were mostly run by Jewish publishers like Timely Comics’s Martin Goodman or DC Comics’s Harry Donenfeld. It was a situation similar to that of the early motion picture industry, in which Jewish directors, producers, and studio executives who’d faced anti-Semitism in other industries built an industry of their own.

Because the comic book stories were being written and drawn largely by inexperienced teenagers, they were often crude rip-offs of the popular newspaper strips of the day, such as Tarzan or Buck Rogers. Enter writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster, the creators of Superman. In 1938, DC Comics published the Man of Steel’s first adventure in the pages of Action Comics #1. Superman was an instant hit. Literally dozens of Superman clones were rushed into production by rival comic book publishers, and suddenly the comic book industry had a future.

According to most comic book historians, Superman’s creation heralded the beginning

of the so-called “Golden Age” of comic books, the era during which the visual grammar of the medium was established. It was also a time when many classic characters were created. There was nothing overtly Jewish about the characters created during this era. However, occasionally a comic book character would emerge that had certain Jewish signifiers. After America became involved in World War II, Timely Comics superhero Captain America’s Jewish creators Joe Simon and Jack Kirby pitted their star-spangled warrior against the Nazi agent Red Skull. Captain America’s alter ego Steve Rogers could be seen as a symbol for the way Jews were stereotypically depicted as frail and passive. That is, until he took a serum that transformed him into the robust Captain America. The serum was created by “Professor Reinstein,” an obvious nod to famed Jewish physicist Albert Einstein. And Superman gave such a pounding to Nazi agents from 1941-45 that, according to legend, Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels jumped up in the midst of a Reichstag meeting and denounced the Man of Steel as a Jew.

Read More: Here

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

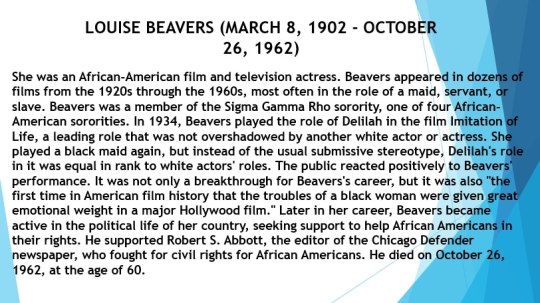

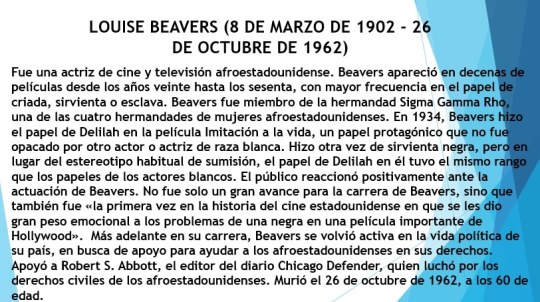

LOUISE BEAVERS.

Filmography

1923: The Gold Diggers

1927: Uncle Tom's Cabin

1929: Election Day, extra.

1929: Coquette

1929: Glad Rag Doll.

1929: Gold Diggers of Broadway.

1929: Barnum Was Right.

1929 - Wall Street.

1929: Nix on Dames.

1930: Second Choice

1930: Wide Open.

1930: She Couldn't Say No.

1930: True to the Navy.

1930: Safety in Numbers.

1930: Back Pay.

1930: Recaptured Love.

1930: Our Blushing Brides.

1930: Manslaughter.

1930: Outside the Law.

1930: Bright Lights.

1930: Paid.

1931: Scandal Sheet

1931: Millie.

1931: Don't Bet on Women.

1931: Six Cylinder Love.

1931: Up for Murder.

1931: Party Husband.

1931 - Annabelle's Affairs.

1931: Sundown Trail.

1931: Reckless Living.

1931: Girls About Town.

1931: Heaven on Earth.

1931: Good Sport.

1931: Ladies of the Big House.

1932: You're Telling Me, extra.

1932: Hesitating Love, extra.

1932: The Greeks Had a Word for Them.

1932: The Expert.

1932: It's Tough to Be Famous.

1932: Young America.

1932: Night World.

1932: The Midnight Lady.

1932: The Strange Love of Molly Louvain.

1932: Street of Women.

1932: The Dark Horse.

1932: What Price Hollywood ?.

1932: Unashamed.

1932: Divorce in the Family.

1932: @ #! *% 'S Highway.

1932: Wild Girl.

1932: Too Busy to Work.

1933: The Midnight Patrol

1933: Grin and Bear It, extra.

1933: She Done Him Wrong.

1933: Her Splendid Folly.

1933: Girl Missing.

1933: 42nd Street.

1933: The Phantom Broadcast.

1933: Pick-Up.

1933 - Central Airport.

1933: The Big Cage.

1933: What Price Innocence ?.

1933: Midnight Mary.

1933: Hold Your Man.

1933: Her Bodyguard.

1933: A Shriek in the Night.

1933: Notorious But Nice.

1933: Bombshell.

1933: Only Yesterday.

1933: In the Money.

1933: Jimmy and Sally.

1934: Palooka

1934: Bedside.

1934: I've Got Your Number.

1934: Gambling Lady.

1934: A Modern Hero.

1934: The Woman Condemned.

1934: Registered Nurse.

1934: Glamor.

1934: I Believed in You.

1934: Cheaters.

1934: Merry Wives of Reno.

1934: The Merry Frinks.

1934: Dr. Monica.

1934: I Give My Love.

1934: Beggar's Holiday.

1934: Imitation of Life.

1934: West of the Pecos.

1934: Million Dollar Baby.

1935: Annapolis Farewell

1936: Bullets or Ballots.

1936: Wives Never Know.

1936: General Spanky.

1936: Rainbow on the River.

0 notes

Link

Shemp Howard Solo, Open Season For Saps 1944, starring Shemp Howard of The Three Stooges. Greetings from Australia. Follow for the best variety of classic films, cartoons and funny videos.StorylineAfter his wife complains about the number of nights Woodcock (Shemp Howard) spends at the Hoot Owl Lodge, he takes her on a belated honeymoon. The first person they meet is lodge member Joe Wilson, who asks Woodcock to help him retrieve some ill-advised letters to lovely hotel guest Irene (Christine McIntyre). Woodcock soon finds himself caught between his jealous wife, and Irene's Latin-tempered fiancee Ricardo.Cast Members(Woodcock Q. Strinker)Shemp Howard(Mrs. Strinker)Early Cantrell(Irene)Christine McIntyre(Joe Wilson)Harry Barris(Ricardo Montell)George J. Lewis(House detective)Jack 'Tiny' Lipson(Desk clerk)Eddie Laughton(Bearded guest)Al Thompson(Waiter)Al MorinoShemp Howard Solo YearsShemp Howard, like many New York-based performers, found work at the Vitaphone studio in Brooklyn. Originally playing bit roles in Vitaphone's Roscoe Arbuckle comedies, showing off his comical appearance, he was given speaking roles and supporting parts almost immediately. He was featured with Vitaphone comics Jack Haley, Ben Blue and Gus Shy, then co-starred with Harry Gribbon, Daphne Pollard and Johnnie Berkes, and finally starred in his own two-reel comedies. A Gribbon-Howard short, Art Trouble (1934), also features then-unknown James Stewart in his first film role. The independently-produced Convention Girl (1935) featured Shemp in a very rare straight role as a blackmailer and would-be murderer.Shemp seldom stuck to the script. He livened up scenes with ad-libbed dialogue and wisecracks, which became his trademark. In late 1935, Vitaphone was licensed to produce short comedies based on the "Joe Palooka" comic strip. Shemp was cast as "Knobby Walsh," and though only a supporting character, he became the series's comic focus, with Johnny Berkes and Lee Weber as his foils. He co-starred in the first seven shorts, released in 1936–1937. Nine of them were produced, the last two done after Shemp's departure from VitaphoneBorn Samuel HorwitzMarch 11, 1895Manhattan, New York City, U.S.Died November 22, 1955 (aged 60)Hollywood, California, U.S.Resting place Home of Peace CemeteryOccupation Comedian, actorYears active 1923–1955Known for The Three StoogesSpouse(s) Gertrude Frank (m. 1925)Children 1Relatives Moe Howard (brother)Curly Howard (brother)Joan Howard Maurer (niece)

#the three stooges#stooges#the three#the#curly howard#shemp howard#moe howard#open season for saps#comedy#solo shorts#parody#spoof#satire#slapstick#comical#mirthful#droll#hilarious#humor#funny#laugh

0 notes

Video

youtube

Palooka 1934 Comedy Music

0 notes

Text

'Funny pages': long part of Vindicator tradition – Youngstown Vindicator

Related Stories

By ROBERT McFERREN

Vindicator Graphic Arts Director

While newspapers are traditionally where readers turn for hard news, information, sports and features, one of the more popular pages in the newspaper is what readers affectionately refer to as ‘the funny pages.’

The Vindicator has run comic strips for 112 of its 150 years. And believe it or not, some of the first strips were in color. Here are some of the highlights of all the comic strip artists who have worked hard to make you smile each day:

The Sunday Vindicator started running a weekly color comic supplement as part of the newspaper. In 1911, the first daily comic strip, “Doings of the Van Loons” by Fred Leipziger (Detroit News) began.

A second strip, “Felix & Fink” from North American Press Syndicate, was added in 1912.

Since then, The Vindicator has consistently run daily comics for the last 100 years: 1919 saw the beginning of the daily comics within The Youngstown Vindicator, starting with “Somebody Is Always Taking the Joy Out Of Life” by Briggs, followed by “That Son-In-Law’s of Pa’s” by Wellington. “School Days,” a single-panel cartoon by Dwig, also appeared.

Within years, comics appeared in most sections of the paper, including editorial cartoons (which occasionally appeared on the front page).

By 1923, the first comic page, with six strips (“Winnie Winkle,” The Bread Winner.” “Bringing Up Father,” “Cicero Sapp,” “Toots and Casper,” “Pa’s Son-In-Law” and “Polly and Her Pals”) and a columnist, began.

By the end of 1923, “Barney Google” and “Gasoline Alley” were added to lineup.

By the mid-’20s, a crossword had been added to newspaper.

In January 1930, the first serial strip, “Tailspin Tommy,” was added to comics. By 1934, 10 comic strips were running daily, including “Little Orphan Annie” and “Dick Tracy.” One year later, the newspaper continued to add new strips, with 13 daily strips, and the expansion to two pages, adding comics “Moon Mullins” and “Joe Palooka.” By the late 1930s, 15 more strips were running, including “Terry and the Pirates” and “Lil Abner.”

However, on Jan 4, 1938, The Vindicator added the most popular and longest-running strip in its history – Chic Young’s “Blondie,” starting its current 81-year-run. The strip is handled by the original artist’s son, Dean, who was born in July of the same year.

By the end of 1947, comic strips were all the rage, with “Steve Canyon” starting in the paper, followed by “Mary Worth” and “Rex Morgan, MD” in 1948.

By 1959, The Vindicator was running 20 daily strips.

The comics spent the next several decades making minor changes, adding “Peanuts,” and other new strips – such as “Hagar the Horrible,” followed by more political strips such as Garry Trudeau’s “Doonesbury.”

When a 1984 redesign reduced the number of columns per page from eight to six, this also led to the elimination of several strips – for a brief period. The Vindicator switchboard was inundated with complaints, and the paper relented and returned the strips and ran all the missed strips in one edition to get readers caught up.

The addition of new comics continued, as the number of daily strips had grown to 23.

By 1990, we were up to 30 daily comic strips. But in 1995, we saw the loss of two popular comic strips, Gary Larson’s “The Far Side” and Bill Watterson’s “Calvin and Hobbes.”

In 2002, the newspaper was changing, and so were the reading habits of our readers. The Vindicator ran a comics survey to see what comics were not as popular with readers – and you were more than happy to give us your feedback. We received nearly 1,500 opinions by letter or email – and this led to the addition of ‘Pickles” and “Zits” as our new strips.

In 2010, The Vindicator redesigned for our new press, which also meant smaller pages, and less space for all the comics on a single page.

The Vindicator dropped to 22 comics, losing “Doonesbury, “For Better or Worse,” “Shoe” and “Cathy.”

With the new press, however, came the addition of comics that were in color seven days a week.

Over the years, strips came and went – whether replaced for a more popular strip, or retired by the death of the comic or the artist. And while there is nothing funny about that, the newspaper industry itself is facing an uncertain future.

So, appreciate what you have while you have it, and remember to laugh.

Let’s block ads! (Why?)

Source link

Bài viết 'Funny pages': long part of Vindicator tradition – Youngstown Vindicator đã xuất hiện đầu tiên vào ngày Funface.

from Funface https://funface.net/funny-news/funny-pages-long-part-of-vindicator-tradition-youngstown-vindicator/

0 notes

Photo

3 Generations of Comic Artist. Ham Fisher was one of the first millionaire newspaper strip cartoonists successful off his 1930 Joe Palooka strip which was one of the top 5 comics of the 1930s. He employed Al Capp and reportedly was a cruel boss to the impoverished ghost assistant. Through a veritable school of hard knocks, Al Capp got out from his shadow and started Lil Abner in 1934, but not without a fierce amount of backstabbing and badmouthing from Fisher. As Capp worked his way out of poverty into meteoric financial success, these two toxically depicted each other in comic form or would hire away each other’s assistants and had a very public feud. In the 1950s, Fisher doctored some of Capps comics and claimed in court that Capp snuck pornography into his comics. Capp supplied originals proving Fisher lied, so Fisher was expelled from the National Cartoonist society and publicly embarrassed. Later, with failing health and depression, Fisher committed suicide. There isn’t a good person in this story though because Capp proved as bad as Fisher, hires Frank Frazetta as a star ghost artist for Lil Abner in 1952 and proved to be as cruel to him. Frazetta claimed Capp underpaid him routinely and when he left Capp in 1961 to go his own way as an artist, faced what Frazetta felt was a silent black list in the comic industry. Frazetta ascended past comics with his magazine and movie poster work, and eventually found fortune in illustration of Book Covers and paintings. Capp was later embarrassed in the early 1970s since it became known he had exposed his genitals to a variety of female college students during his speaking circuits. Frazetta came out of this without any stories of vindictive payback to people who assisted or helped him, and his reputation has still been positive years after his death.

0 notes

Text

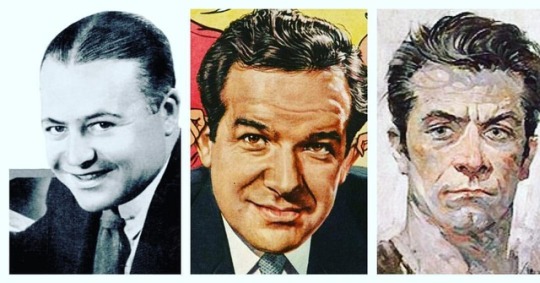

STUART ERWIN.

Filmography

1928 Mother Knows Best

1929 speakeasy

1929 Through Different Eyes

1929 The Exalted Fin

1929 Dangerous Curves

1929 The Sophomores

1929 happy days

1929 The world of rooster eyes

1929 Honey

1929 The Trespasser

1929 This Thing Called Love

1930 Men without women

1930 Young Eagles

1930 Paramount on Parade

1930 The Dangerous Nan McGrew

1930 Love Between Millionaires

1930 Paris Playboy

1930 Only Saps works

1930 Youth came together

1931 No Limit

1931 Ranch Type

1931 Up Pops the Devil

1931 The Magnificent Lie

1931 Working Girls

1932 Two Kinds of Women

1932 Strangers in Love

1932 Deceitful Lady

1932 Make me a star

1932 The Great Broadcast

1933 Face in the Sky

1933 Crime of the Century

1933 Learned about women

1933 Beneath Tonto's Edge

1933 International House

1933 Hold Your Man

1933 The Stranger Returns

1933 Before Dawn

1933 Doomsday

1933 Going to Hollywood

1934 Palooka

1934 Long live Villa!

1934 Bachelor Bait

1934 Party's Over

1934 Have a heart

1934 The band keeps playing

1935 After Office Hours

1936 Zero ceiling

1936 Absolute Silence

1936 Women are a problem

1936 Pigskin Parade

1937 Slim

1937 Dance Charlie Dance

1937 Small Town Boy

1937 Sunday Night at the Trocadero

1937 Second honeymoon

1947 Killer Dill

1947 Heaven Only Knows

1947 Heading for Heaven

1947 Doctor Jim

1948 Get Rich

1950 Father is single

1953 Main Street to Broadway

1960 For the Love of Mike

1963 Son of Flubber

1964 The Misadventures of Merlin Jones.

Créditos: Tomado de Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stuart_Erwin

0 notes

Text

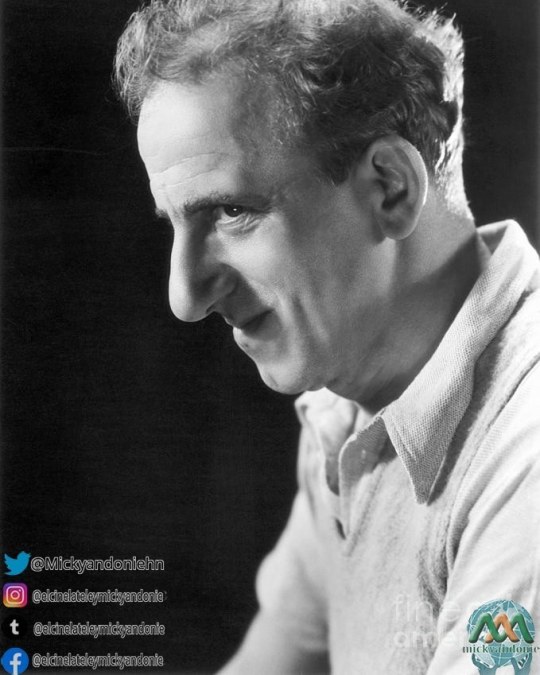

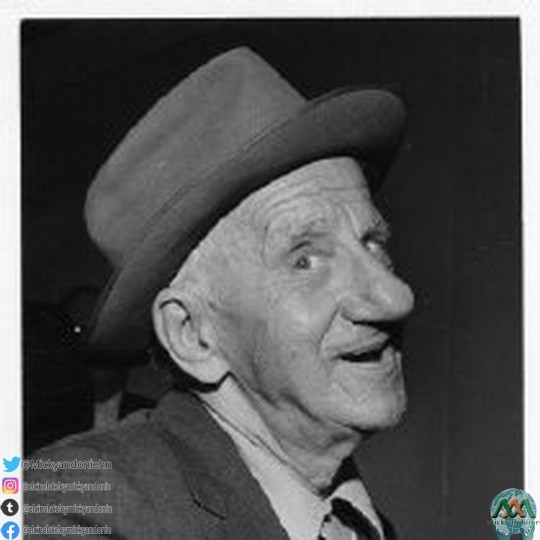

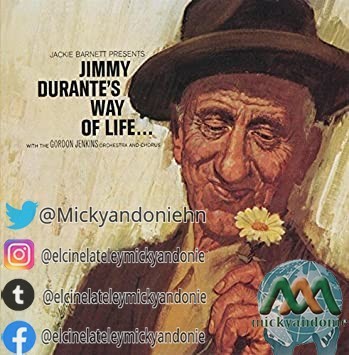

JIMMY DURANTE.

Filmografía

1921 Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford

1930 Roadhouse Nights

1931 The New Adventures of Get-Rich 1931 Quick Wallingford

1931 The Cuban Love Song

1931 Jackie Cooper's Birthday Party

1931 The Christmas Party

1932 Hollywood on Parade: Down 19321932 The Wet Parade

1932 Hollywood on Parade

1932 Speak Easily

1932 Blondie of the Follies

1932 The Phantom President

1932 Give a Man a Job

1933 What! No Beer?

1933 Hollywood on Parade No. 9

1933 Hell Below

1933 Broadway to Hollywood

1933 Meet the Baron

1934 Palooka

1934 George White's Scandals

1934 Strictly Dynamite

1934 Hollywood Party

1934 Student Tour

1935 Carnival

1936 Land Without Music

1938 Start Cheering

1938 Sally, Irene and Mary

1938 Little Miss Broadway

1940 Melody Ranch

1940 You're in the Army Now

1942 The Man Who Came to Dinner

1944 Two Girls and a Sailor

1944 Music for Millions

1946 Two Sisters from Boston

1947 It Happened in Brooklyn

1947 This Time for Keeps

1948 On an Island with You

1950 The Great Rupert

1950 The Milkman

1955 Screen Snapshots: Hollywood Premiere

1957 The Heart of Show Business

1957 Beau James

1960 Pepe

1961 The Last Judgment

1962 Billy Rose's Jumbo

1963 El mundo está loco, loco, loco

1966 Alice Through the Looking Glass

1974 Just One More Time.

Créditos: Tomado de Wikipedia

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jimmy_Durante

0 notes

Text

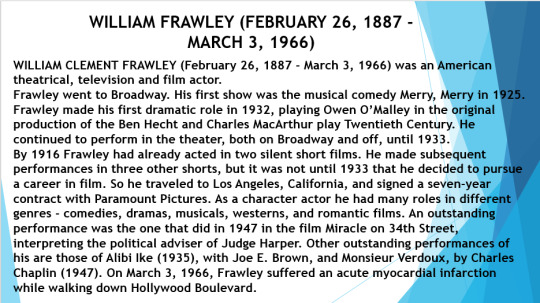

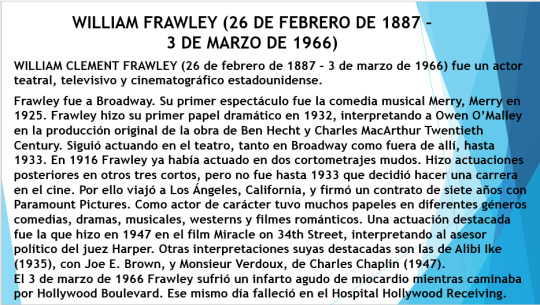

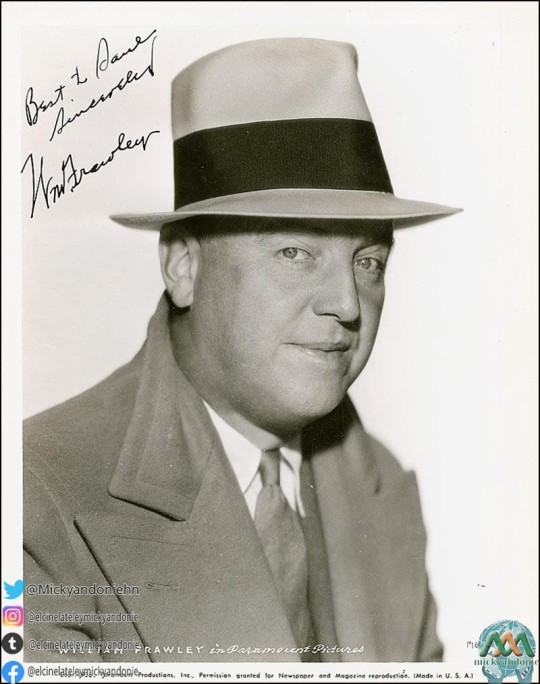

WILLIAM FRAWLEY.

Filmography

Movie theater

1916 Lord Loveland Discovers America

1916 Persisent Percival

1925 Should Husbands Be Watched?

1929 Turkey for Two

1929 Fancy That

1933 Moonlight and Pretzels

1933 Hell and High Water

1934 Miss Fane's Baby Is Stolen

1934 Bolero

1934 The Crime Doctor

1934 The Witching Hour

1934 Shoot the Works

1934 The Lemon Drop Kid

1934 Here Is My Heart

1935 Car 99

1935 Roberta

1935 Hold 'Em Yale

1935 Alibi Ike

1935 College Scandal

1935 Welcome Home

1935 It's a Great Life

1935 Harmony Lane)

1935 Ship Cafe

1936 Strike Me Pink

1936 Desire

1936 F-Man

1936 The Princess Comes Across

1936 Three Cheers for Love

1936 The General Died at Dawn

1936 Three Married Men

Rose bowl

1937 High, Wide, and Handsome

1937 Double or Nothing

1937 The Dangers of Glory

1937 Blossoms on Broadway

1938 Mad About Music

1938 Professor Beware

1938 Sons of the Legion

1939 Ambush

1939 St. Louis Blues

1939 Persons in Hiding

1939 The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

1939 Rose of Washington Square

1939 Ex-Champ

1939 Grand Jury Secrets

1939 Night Work

1939 Stop, Look and Love

1940 The Farmer's Daughter

1940 Opened by Mistake

1940 Those Were the Days!

1940 Untamed

1940 Golden Gloves

1940 Rhythm on the River

1940 The Quarterback

1940 One Night in the Tropics

1940 Dancing on a Dime

1940 Sandy Gets Her Man

1941 Six Lessons from Madame La Zonga

1941 Footsteps in the Dark

1941 Blondie

1941 The Bride Came C.O.D.

1941 Cracked Nuts

1941 Public Enemies

1942 Treat 'Em Rough

1943 We've Never Been Licked

1943 Larceny with Music

1943 Whistling in Brooklyn

1944 The Fighting Seabees

1944 Going My Way

1944 Minstrel Man

1944 Lake Placid Serenade

1945 Flame of Barbary Coast

1945 Hitchhike to Happiness

1945 Lady on a Train

1946 Ziegfeld Follies

1948 Good Sam

1948 The Babe Ruth Story

1948 Joe Palooka in Winner Take All

1948 The Girl from Manhattan

1949 Chicken Every Sunday

1950 blondie

1950 Kill the Umpire

1950 Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye

1950 Pretty Baby

1951 Abbott and Costello Meet the 1951 1951 Invisible Man

1951 The Lemon Drop Kid

1951 Rhubarb

1952 Notorious Ranch

1953 I Love Lucy

1954 The Dirty Look

1954 Better Football

1962 Safe at Home !.

TV

1951-1957 I Love Lucy

1957-1960 The Lucille Ball-Desi Arnaz Show

1960-1965 My Three Sons)

1965 The Lucy Show.

Work on broadway

1925 -1926 Merry, Merry

1927 Bye, Bye, Bonnie

1928 She's My Baby

1928 Here's Howe

1929-1930 Sons O 'Guns

1931 She Lived Next to the Firehouse

1932 Tell Her the Truth

1932-1933 Twentieth Century

1933 The Ghost Writer.

Créditos: Tomado de Wikipedia

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Frawley

#HONDURASQUEDATEENCASA

#ELCINELATELEYMICKYANDONIE

0 notes

Text

JIMMY DURANTE.

Selected filmography

1921 Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford

1930 Roadhouse Nights

1931 The New Adventures of Get-Rich 1931 Quick Wallingford (1931)

1931 The Cuban Love Song

1931 Jackie Cooper's Birthday Party

1931 The Christmas Party

1932 Lane

1932 The Wet Parade

1932 Hollywood on Parade

1932 Speak Easily

1932 Blondie of the Follies

1932 The Phantom President

1933 Give a Man a Job

1933 What! No Beer?

1933 Hollywood on Parade No. 9

1933 Hell Below

1933 Broadway to Hollywood

1933 Meet the Baron

1934 Palooka

1934 George White's Scandals

1934 Strictly Dynamite

1934 Hollywood Party

1934 Student Tour

1935 Carnival

1936 Land Without Music

1938 Start Cheering

1938 Sally, Irene and Mary

1938 Little Miss Broadway

1940 Melody Ranch

1941 You're in the Army Now

1942 The Man Who Came to Dinner

1944 Two Girls and a Sailor

1944 Music for Millions

1946 Two Sisters from Boston

1947 It Happened in Brooklyn

1947 This Time for Keeps

1948 On an Island with You

1950 The Great Rupert

1950 The Milkman

1955 Screen Snapshots: Hollywood Premiere

1957 The Heart of Show Business

1957 Beau James

1960 Pepe

1961 The Last Judgment

1962 Billy Rose's Jumbo

1963 The world is crazy, crazy, crazy

1966 Alice Through the Looking Glass

1974 Just One More Time.

Créditos: Tomado de Wikipedia

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jimmy_Durante

#HONDURASQUEDATEENCASA

#ELCINELATELEYMICKYANDONIE

0 notes

Link