#PKK

Text

A short YDG-H / PKK propaganda music video, celebrating the fight by the Kurdish youth against the brutal Turkish occupation. Biji Kurdistan!

#ydg-h#pkk#kurdistan#biji kurdistan#occupation#anti-colonialism#war#guerrilla#guerrilla war#video#music#propganda

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

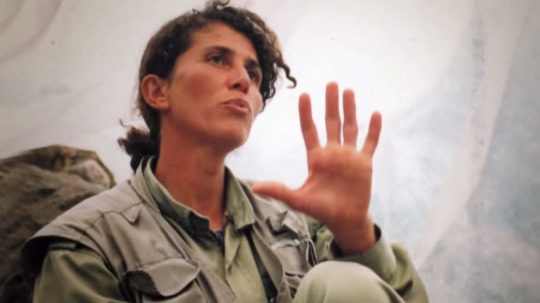

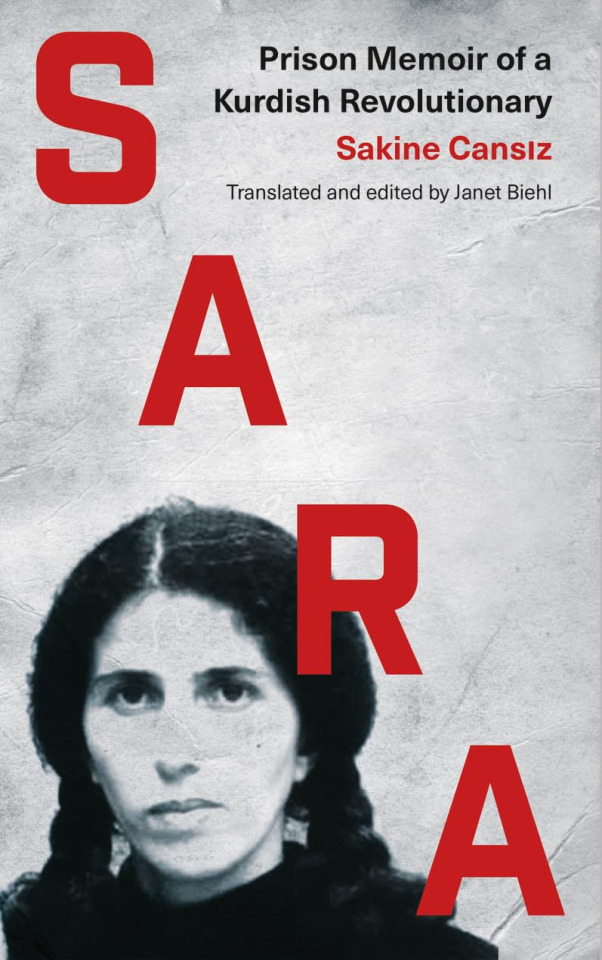

"Sara" Sakine Cansiz 1958-2013

Revolutionary and co-founder of the PKK, the political and military movement for Kurdish liberation.

"the excitement of entering the movement as a young woman--and discovering quickly that she would have to challenge traditional gender roles as she rose among its ranks. And she succeeded: total gender equality is now one of the central tenets of the PKK."

She wrote 2 memoirs about her activist youth and when she was in prison.

She was sadly assassinated by the ethnoreligious fascists in Turkey in 2013.

She survived 40 years of political involvement in a nation that didn't want her to exist.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

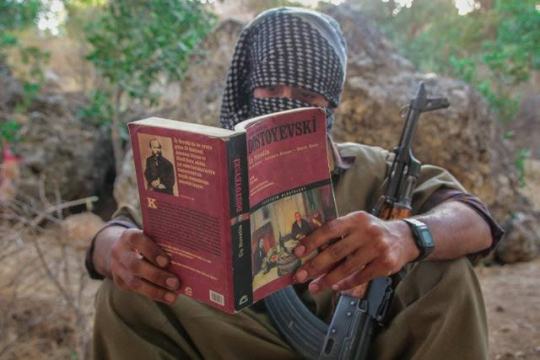

Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK)

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sakine Cansız, (1996-1997, 2015), Sara. Prison Memoir of a Kurdish Revolutionary, Translated and edited by Janet Biehl, Pluto Press, London, 2019

«Sakine Cansız with unidentified women prisoners at Çanakkale, c. 1990.» (p. 317)

In italiano: Sakine Cansiz (Sara), Tutta la mia vita è stata una lotta, Vol. I (2014), Vol. II (2015), Vol. III (2017), UIKI Onlus – Ufficio di Informazione del Kurdistan in Italia

#graphic design#book#cover#book cover#sakine cansız#janet biehl#partîya karkerén kurdîstan#pkk#jin jiyan azadî#pluto press#uiki onlus#1990s#2010s

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Türkiye has resumed bombing Rojava.

This bombing takes place as a retaliation for the failure of Turkey's operations on the Iraqi-Syrian border along with the killing of 12 soldiers by the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK).

ترکیه بمباران روژاوا را دوباره از سر گرفته است.

این بمباران به عنوان تلافی ناکامی عملیات ترکیه در مرز عراق و سوریه همراه با کشته شدن ۱۲ سربازان توسط مبارزان حزب کارگران کوردستان (PKK) صورت میگیرد.

#روژاوا

#ترکیه

#Rojava

#Turkey

#Turkiye

#rojava#Türkiye#pkk#ypj#ypg#turkey#iraq war#iraq#syrian civil war#free syria#us shoots down armed turkish drone flying near american troops in syria#syria#syria news#syrian refugees#syrian#class war#kurdistan#waristerror#wariscapitalism#kurdistan workers party#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia#fuck neoliberals#neoliberal capitalism#anthony albanese#albanese government

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

kurdish women demonstrating after the arrest of PKK leader abdullah ocalan, london, united kingdom, 1999 by steve eason

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

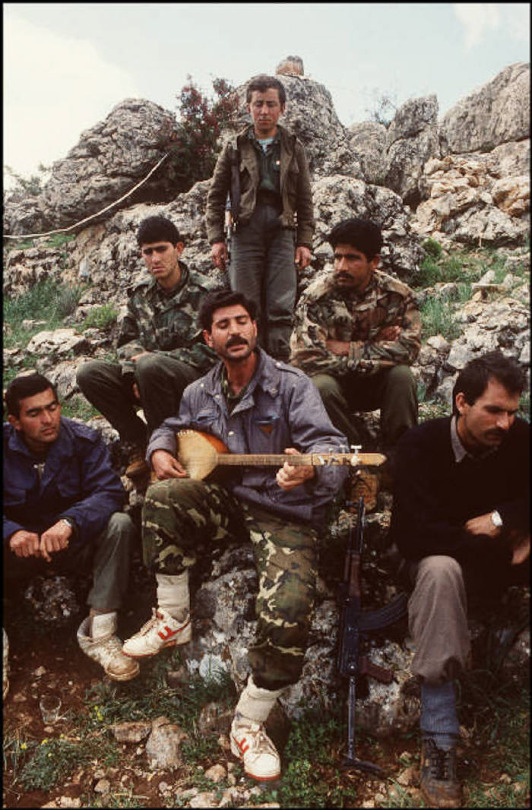

Membros do Partido dos Trabalhadores do Curdistão (PKK) em campo de treinamento no Vale do Beca, Líbano, 1991. Foto por Nikos Economopoulos.

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just leaving this here.

Feel free to reblog.

#dougie rambles#political crap#Asia#middle east#iraq#assyria#nineveh#sinjar#yazidi#yazidis#yezidi#yezidis#remembrance#fuck ISIS#pkk#hpg#sinjar resistance units#SDF#Syrian Democratic forces#bethnahrin#rojava#ypg#YPJ#anti imperialism#leftism#reblog this#reblog the shit out of this#turkey#kurdistan#fuck Erdogan

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

feel free to ignore this question. but I'm actually fr wondering what it was like to be trans in the ypg? the pkk has a notably radical policy on women's liberation, but from my understanding jineologie is very binary and clearly understood from a cis pov.

I wish I could offer a satisfying answer. Sadly, until just a year ago, I was cis and have no sweet clue. I need to read more into Apo's work to get a vibe, but that wouldn't surprise me very much. For leftist groups, the PKK and YPG are relatively conservative (at least I feel in some ways).

Notable is that the women's organizations (YJA-STAR and YPJ) are separate groups from the PKK and YPG which are male-oriented. It's actually more confusing than that because they have a sort of...parallel command structure? So for example the "base" I was at had both a male and female commander who sort of co-commanded the actual contingent of militia.

As I noted in a previous ask, it's been almost ten years. There is the very real possibility of change on the ground since I've been there. I don't think that members of the PKK or YPG are trans- or homophobic as part of their ideology. However I have to be clear that this topic didn't really come up (or if it did I missed it because of the language barrier) so heaping grains of salt and all that.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

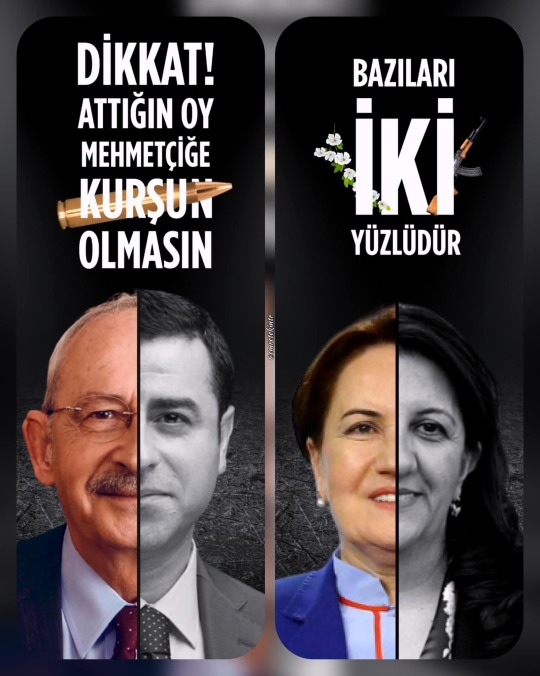

#hdp#pkk#hdpkk#chp#selahattin demirtaş#kemal kılıçdaroğlu#ali babacan#iyi parti#meral akşener#millet i̇ttifakı#gelecek partisi#ahmet davutoğlu#gültekin onay#dp#temel karamollaoğlu#demokrasi ve atılım partisi

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Marxist-Feminist prisoners resisted prison uniforms

Yes, tension had diminished for a while, but now it came roaring back. The enemy didn’t implement all our demands. He withdrew many of the rights we’d fought for or never put them into practice at all. He censored the newspapers—he cut out the most important articles before we got them. Books we ordered arrived after months of waiting because they were supposedly being “examined.” He rejected requests made by the prisoners’ representatives. He wanted to keep us from knowing that our resistance could ever succeed, and to keep us in constant fear.

Uncertainty was brewing. Communication between the wards remained difficult, but some messages from the men reached us, verbal and written, saying that the enemy now insisted on them singing the national anthem once a week, addressing the captain as “commander,” and counting off. What did we think about it? they asked. “If you don’t go along with it, then we won’t either,” the men wrote. But another message said they’d decided: “We decided to stick to the agreement for a while, to see what the administration would do.” That bothered me. So far, the enemy had failed to force us [women] to address him as “commander.”

For a time, our representative had said “commander” during roll call, when she called out her number, but we’d stopped that too. We’d sidestepped a lot of rules or just ignored them. For us to start following that rule now, when we hadn’t before, would be a big setback, and it would mean we were submitting to military discipline. I wrote back, “We won’t abide by your decision. It puts the whole resistance in a bad light.” The men criticized that but let us decide for ourselves. We communicated our decision to the representatives, to the other prisoners, and to the families, who made a joint petition to the military commander.

We informed the lawyers, but they were even more useless than our families—they did nothing. The prison authorities issued a new order: “Every prisoner is a soldier and is to be treated like a soldier.” It went on and on. And then finally a rumor started that we were to get prison uniforms. Uniforms! We couldn’t imagine it—we thought of the striped convict garb in American films. Were they going to make us wear standardized blouses and skirts or shorts? We laughed about it, but seriously, what did it signal about the prison? The men friends warned all wards: “The purpose of the uniforms is to create a unitary human type. They are an attack on the resistance. We will refuse to wear them.”

We took to wearing several layers of underwear under our normal clothes, in case the enemy tried to take them away. The idea of being stripped made us cringe. The soldiers would certainly attack if they set eyes on naked or half-naked women. It would be ugly. But we were determined to refuse the uniforms. Nor would we take a step backwards or give up improvements we’d gained in the death fast. Then we heard that some of the men had been isolated for defying or insulting the soldiers. When we saw them in the courtroom or the infirmary, they looked pale because they were being denied time in the exercise yard. Diseases were spreading. None of the TKP women prisoners were forced to comply with the new rules, due to their conciliatory attitude toward the enemy.

On January 1, 1984, our uprising began. We built barricades, placing iron beds and tables at the doors. The steel lockers were as tall as the doors, and the inner and outer doors were separated by only a short distance. The soldiers were afraid to open the outer door. Looking in through the slot, they just saw a steel locker. [Unlike the 1983 death fast, leadership cadre did not organize this action. The morale, experience, and confidence gained by the September 1983 resistance enabled broad participation.] Knowing they’d throw smoke bombs in through the door slots, we taught all the prisoners how to cover their mouth and nose with a damp cloth. We banged plates against the iron window frames and against the doors, making a racket. We chanted slogans, and sang revolutionary songs, and recited poetry. That was how we protested torture—we didn’t have any other way. The barricades reminded me of what I’d read about the Paris Commune. The people and resistance units had built barricades on the streets and fought behind them. We knew about barricades from novels and movies.

Now we were constructing them ourselves, under very different conditions. Our only weapons were our beliefs, our will, and our naked bodies. At the moment, only our voices were fighting. The enemy could still break open the door, tear down walls, or come in through the windows—but we didn’t care. The important thing was to make it as hard as we could for him. Later we found out that barricades had been erected in many other wards as well. But prisoners were still dragged to the movie theater. Those who refused to wear uniforms were stripped naked and tortured. Those who capitulated and accepted the rules were housed in a ward together.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Free Women’s Units, shortened from the Kurdish name as YJA STAR, is the women’s military wing of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

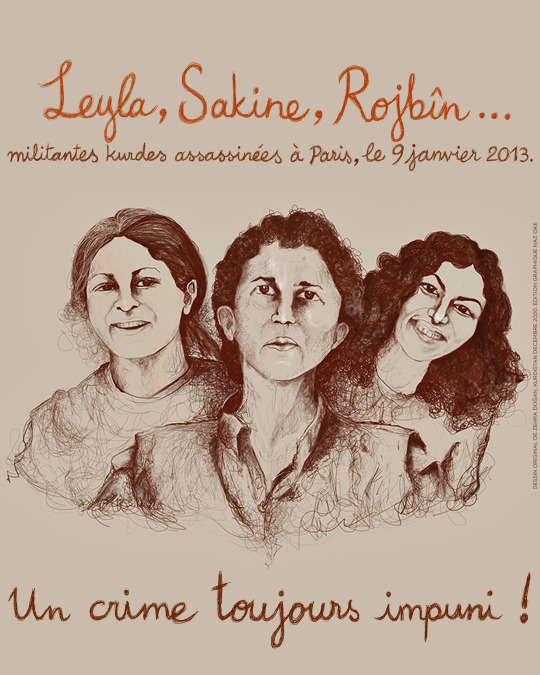

Sakine Cansız (Sara), Fidan Doğan (Rojbîn), Leyla Şaylemez (Ronahî), Paris, January 9, 2013

Sara, Rojbîn, Ronahî – Jin Jiyan Azadî

«Il 9 gennaio 2013 Sakine Cansiz, Fidan Doğan e Leyla Şaylemez, tre compagne del movimento di liberazione curdo, sono state uccise da un agente dei servizi segreti turchi (MIT) a Parigi, nel cuore della grande Europa "democratica". Nonostante siano chiari i motivi che hanno portato a questo assassinio, non ci sono ancora verità e giustizia per le nostre compagne.

Queste tre donne, che gli stati occidentali hanno chiamato "terroriste", avevano deciso di dedicare la loro vita alla lotta per la libertà. Erano bellissime, belle perché libere, belle perché amavano i popoli e le persone, belle perché credevano nella rivoluzione.» – Rete Jin

(image: Leyla, Sakine, Rojbîn... militantes kurdes assassinées à Paris, le 9 janvier 2013. Un crime toujours impuni!, Drawing by Zehra Doğan (Kurdistan, December 2020), Graphic Design by Naz Oke)

#art#drawing#jin jiyan azadî#sakine cansız#fidan doğan#leyla şaylemez#zehra doğan#naz oke#partîya karkerén kurdîstan#pkk#rete jin#2010s#2020s

8 notes

·

View notes