#Mont-Saint-Alban

Text

#Cap-Bon-Ami#Parc National Forillon#Mont-Saint-Alban#La Chute#Prélude-à-Forillon#Camping#Hiking#Nature Hikes

1 note

·

View note

Text

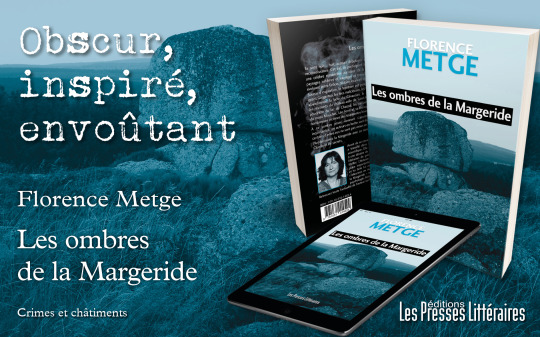

Les ombres de la Margeride - Florence Metge

Ils sont huit : huit auteurs débutants en quête de publication et de reconnaissance. Cet été, ils participent à un atelier d’écriture animé par une célèbre romancière au cœur de la Margeride. Ils découvrent des paysages sublimes et sauvages et travaillent sur leurs projets littéraires, évoluant entre fiction, histoire locale et légendes terrifiantes.

Source d’inspiration, le territoire est peuplé d’ombres et de mystères : le géant Gargantua, les fées malicieuses, les verriers de la manufacture royale abandonnée, la bête du Gévaudan, le sulfureux comte de Morangiès, les résidents du château-asile de Saint-Alban, les barons de Randon, la poudrière du lac de Charpal, les militaires de Fortunio, les maquisards du mont Mouchet, Léo Ferré et sa Baraque du Cheval mort ainsi que les nombreuses victimes des tourmentes hivernales…

À ce sombre passé viennent s’ajouter aujourd’hui des disparitions inquiétantes. Les auteurs en herbe sont-ils en danger ? De toute évidence, certains d’entre eux ne sont pas venus en Margeride que pour écrire…

(Re)découvrez la Margeride avec ce roman qui réjouira les amateurs de Cluedo et de secrets.

Avant de se consacrer à l’écriture, Florence Metge a travaillé dans le monde de la communication scientifique. Elle a écrit cinq romans et contribué à une dizaine de recueils de nouvelles. Ses genres littéraires de prédilection sont le suspense et le thriller. L’histoire et la géographie tiennent une place importante dans ses récits. Le Gévaudan et sa bête lui ont inspiré plusieurs livres. Après « Meurtres en Aubrac » (2023), « Les ombres de la Margeride » mêle intrigues, enquête policière, psychologie, histoire locale et légendes.

Retrouvez toute l’actualité de l’auteur sur Facebook et Babelio.

ISBN : 979-10-310-1452-4

11,5 X 17, 376 pages, 16,00 €

0 notes

Text

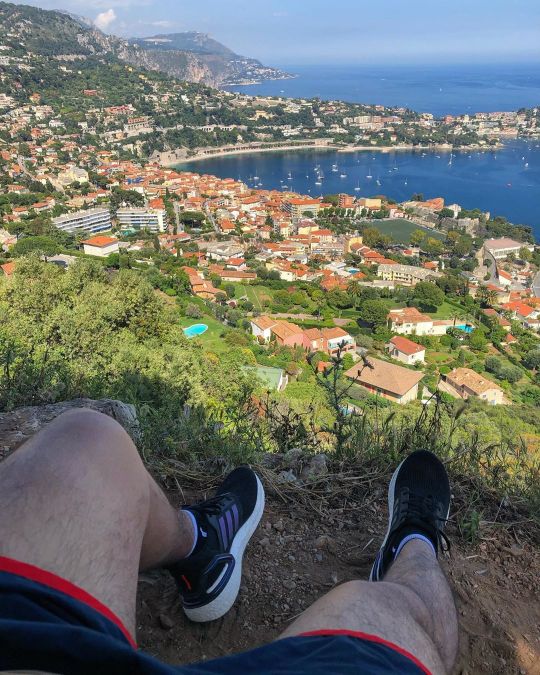

Nice

Nice est aujourd'hui la capitale des Alpes-Maritimes sur la Côte d'Azur mais elle fut pendant longtemps une ville italienne. Située au bord de la méditerranée, dans la baie des Anges, elle rend hommage à son passé avec ses façades aux couleurs chaudes.

La cité est bordée par des plages de galets où il fait bon farniente l'été mais propose aussi une importante offre culturelle avec ses nombreux musées ainsi que de jolies promenades verdoyantes, au cœur du centre-ville et dans les collines sauvages environnantes.

Comment venir ?

Nice se situe :

en avion : 1h de Paris, 1h de Toulouse

en train : 25min de Monaco, 30min d'Antibes, 40min de Cannes, 40min de Menton, 1h10 de Grasse, 1h30 Saint-Raphaël

en voiture : 30min de Monaco, 40min d'Antibes, 40min de Menton, 45min de Grasse, 50min de Cannes, 1h10 Saint-Raphaël, 1h50 de Saint-Tropez

en bus : 20min d'Antibes, 30min de Cannes

Les villes du bord de mer en région PACA étant particulièrement bien desservi par le réseau ferroviaire je vous conseille fortement de profiter d'être à Nice pour visiter d'autres cités balnéaires méditerranéennes.

Quand et combien de temps ?

Pour un grand week-end de découverte de la ville ou pour une petite semaine de vacances de repos, Nice s'adaptera à vos envies. En été comme en hiver l'ancienne cité italienne et celles à proximité vous offriront du soleil, de jolies couleurs et de quoi vous occuper.

Attention toutefois aux périodes de vacances scolaires, notamment celles d'été, et de jours fériés où la ville risque d'être prise d'assaut par les touristes.

Quoi voir à Nice ?

Des lieux et bâtiments historiques : Vieux Nice, marché aux fleurs du cours Saleya, Palais de la Préfecture, place Saint-François, place Rossetti, tour Saint-François, place Masséna, quartier Belle Époque, palais Lascaris, place Garibaldi, Villas Castor et Pollux, boulevard Franck Pilatte, tour Saint-François, ruines romaines (les arènes et les thermes), port Lympia

Des promenades et espaces verts : Promenade des Anglais, Promenade du Paillon, Château de Valrose et son parc, Colline de Cimiez, mont Boron et le mont Alban, promenade du phare, sentier littoral, cascade de Gairaut, colline du château de Nice, parc Vigier, jardin Albert Ier, jardin de la villa Masséna, jardin du monastère

Du patrimoine religieux : chapelle de la miséricorde, cathédrale Sainte-Réparate, église Sainte-Jean-d’Arc, cathédrale orthodoxe russe, cimetière du château, église Sainte-Rita, église Saint-Jacques-le-Majeur, cathédrale Sainte-Répérate, église du Gesu, monastère des Franciscains, église Notre-Dame-Auxiliatrice

Des musées : musée Chagall, musée d’arts asiatiques, musée masséna, musée Terra Amata, musée de la photographie Charles Nègre, musée des Beaux-Arts Jules Chéret, musée International d’Art Naïf Anatole Jakovsky, (musée des instruments de musique de Nice), musée Matisse, musée archéologique

Quoi voir dans les environs de Nice ?

Des villes et villages : St Jean Cap Ferrat, la Corse, Menton, Monaco, Saint Agnès, Eze, Antibes, Grasse, Îles de Lérins, Saint-Tropez, Juan-Les-Pins, Mougins, Saint Paul de Vence, Biot, Cagnes-sur-Mer, Villefranche-sur-Mer, Vence, Rimplas, Clans, Utelle, La Tour-sur-Tinée, Ilonse, Marie, Tournefort, Saint-Sauveur-Sur-Tinée et Bairols

Des espaces naturels : bords de la baie des anges, l'Estérel, vallée de la Vésubie, vallée de la Tinée, Camps des Fourches, Col de Pouriac, Auron, Lacs de Vens, Isola, Arboretum de Roure, canyon du Vallon du Moulin , la Colmiane

Des lieux uniques : Villa Rothschild, villa Kérylos

crédits photos @lilstjarna

0 notes

Photo

Les samedi 17 et dimanche 18 septembre 2022 se sont tenues la 39ème édition des Journées Européennes du Patrimoine, sur le thème « Patrimoine Durable » 🇫🇷 🇪🇺 J'ai visité des sites patrimoniaux à Nice (certains n'ouvrent que pendant cet événement): Hôtel de Ville, Cathédrale Sainte-Réparate, Théâtre de la Photographie et de l'Image Charles Nègre, Palais des Rois Sardes, Exposition « Eileen Gray et le Corbusier : deux génies créateurs sur la Côte d’Azur », Archives départementales, Fort du Mont Alban, Palais Lascaris, et Tour Saint-François 💙🤍❤️ #amazingadventuresofbeaujethro #journeesdupatrimoine #heritage #nice #alpesmaritimes #ilovenice #cotedazur #frenchriviera #france #patrimoinefrancais #culture #history (at Nice, France) https://www.instagram.com/p/Ciw1J3er5Q0/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#amazingadventuresofbeaujethro#journeesdupatrimoine#heritage#nice#alpesmaritimes#ilovenice#cotedazur#frenchriviera#france#patrimoinefrancais#culture#history

0 notes

Text

Les Dix Mille Martyrs sur le Mont Ararat, 1515 de Vittore Carpaccio : 1465-1526, Italy

More Saints of the Day June 22

St. Thomas More

St. Alban

St. Alban of Britain

St. Consortia

St. Eberbard

St. Flavius Clemens

St. John Fisher

Martyrs of Ararat

St. Nicetas

St. Nicetas of Remesiana

St. Paulinus of Nola

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Fragment of an Architectural Frieze

ARTIST CULTURE Zapotec

PERIOD Late Classic period, 600–909

DATE c.600–909

MATERIAL Terracotta with whitewash and buff pigment

FROM Oaxaca state, México

PROVENANCE Private collection [1]

by 1966 -

William Spratling (1900-1967), Taxco, Guerrero, Mexico [2]

- 1966

Harry A. Franklin Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA, USA

1966 - 1978

Morton D. May (1914-1983), St. Louis, MO, purchased from Harry A. Franklin Gallery [3]

1978 -

Saint Louis Art Museum, given by Morton D. May [4]

Notes:

This object is one of 18 architectural fragments accessioned by the Museum in 1978 [351:1978.1-.18]. Although all the fragments were donated by Morton D. May, May purchased them from two different sources. 351:1978.3, .5, .6, .8, .9, .10, .11, .12, .14, .17, .18 share the same provenance.

[1] A letter dated July 25, 1966 from author Frank H. Boos to Museum curator Philippa D. Shaplin notes this tile was previously in an unnamed private collection [Curatorial Office, Primitive and Precolumbian Art Departmental Correspondence, Archives, Saint Louis Art Museum].

[2] A letter dated October 20, 1966 from Boos to Shaplin identifies Spratling as owning this tile after the private collector [SLAM document files]. In a letter dated May 8, 1967 from Boos to Shaplin regarding the purchase of an additional tile [218:1978], Boos stated the tile [218:1978] was "in the possession of the one who owned the first lot [351:1978.3, .5, .6, .8, 9, .10, .11, .12, .14, .17, .18] of them" [Curatorial Office, Primitive and Precolumbian Art Departmental Correspondence, Archives, Saint Louis Art Museum]. A letter dated May 11, 1967 from Shaplin to Boos clearly identifies the tile [218:1978] was "obtained from Spratling" [Curatorial Office, Primitive and Precolumbian Art Departmental Correspondence, Archives, Saint Louis Art Museum]. Two additional letters from Boos to Shaplin dated May 29, 1967 and June 3, 1967 identify the tile [218:1978] as "Spratling's "newly-discovered" tile" and "Spratling's new found tile" [SLAM document files].

[3] An invoice dated March 30, 1966 from Harry A. Franklin Gallery to May documents this purchase, listed as "Monte Alban (Zapotec) frieze terracotta" [May Archives, Saint Louis Art Museum].

[4] A letter dated September 19, 1978 from May to James N. Wood, director of the Saint Louis Art Museum, includes the offer of this object as part of a larger donation [SLAM document files]. Minutes of the Acquisitions Committee of the Board of Trustees, Saint Louis Art Museum, December 13, 1978.

SLAM

#archaeology#arqueologia#zapotec#oaxaca#mesoamerica#mexico#art#arte#history#historia#native american

53 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hodie XX aprilis... Sanctae Agnes Monte Politiano St. Agnes of Monte Pulciano, Virgin and Abbess A.D. 1317. THIS holy virgin was a native Monte Pulciano, in Tuscany. She had scarcely attained to the use of reason, when she conceived an extraordinary relish and ardour for prayer, and in her infancy often spent whole hours in reciting the Our Father and Hail Mary, on her knees, in some private corner of a chamber. At nine years of age she was placed by her parents in a convent of Sackins, of the order of St. Francis, so called from their habit, or at least their scapular, being made of sackcloth. Agnes, in so tender an age, was a model of all virtues to this austere community: and she renounced the world, though of a plentiful fortune, being sensible of its dangers, before she knew what it was to enjoy it. At fifteen years of age she was removed to a new foundation of the Order of St. Dominic, at Proceno, in the county of Orvieto, and appointed abbess by Pope Nicholas IV. She slept on the ground, with a stone under her head in lieu of a pillow; and for fifteen years she fasted always on bread and water, till she was obliged by her directors, on account of sickness, to mitigate her austerities. Her townsmen, earnestly desiring to be possessed of her again, demolished a lewd house, and erected upon the spot a nunnery, which they bestowed on her. This prevailed on her to return, and she established in this house nuns of the Order of St. Dominic, which rule she herself professed. The gifts of miracles and prophecy rendered her famous among men, though humility, charity, and patience under her long sicknesses, were the graces which recommended her to God. She died at Monte Pulciano, on the 20th of April, 1317, being forty-three years old. Her body was removed to the Dominicans’ church of Orvieto, in 1435, where it remains. Clement VIII. approved her office for the use of the Order of St. Dominic, and inserted her name in the Roman Martyrology. She was solemnly canonized by Benedict XIII. in 1726. Rev. Alban Butler (1711–73). Volume IV: April. The Lives of the Saints. 1866.

27 notes

·

View notes

Link

A local’s guide to Melbourne suburb (and other Victorian place) names:

Beaumaris: Beau-MAURICE, not Beau-MARRIS

Berwick: Berrick, not BER-wick

Cranbourne: Cran-BURN, not Cran-BORN

Doncaster: Don-CASTER, not Don-CASS-TER

Jan Juc: Jan JUCK, not ZHAN ZHUKE

Kallista: Kal-LIS-ta, not KALL-is-TA

Lalor: LAY-lor, not LAW-ler

Maidstone: Maid-stone, not Maid-ston

Malvern: MOL-vern, not MAUL-vern or MAL-vern

Melbourne: Mel-BEN, not Mel-BORN

Moorabbin: Mor-ABB-in, not MOO-rab-in

Murrumbeena: Murum-BEE-na, not Moo-RUM-beena

Narre Warren: Narry (As in ‘Harry’) Warren, not Nara Warren or Nar-ray War-REN

Niddrie: Nid-djree, not Nid-rie

Northcote: North-CUT, not North-COAT

Ormond: OR-mond, not Or-MUND

Prahran: Pr-AAN, not Pra-RAN or Pra-RAHN

Reservoir: Reser-VWORR, not Reser-VWAH

St Albans: St ALL-bans, not Saint AL-bans

Travancore: Travan-CORE, not Trav-VAN-core

Truganina: Trug-A-NINE-A, not Trug-A-NINA

Vermont: Ver-MONT, not VER-mont

1 note

·

View note

Photo

This view is why I drove up and explore this peninsula. The view of Cap Gaspé on the hiking trail to Mont Saint Alban. #capgaspé #montsaintalban #forillonnationalpark #parkscanada #keepexploringcanada #explorecanada #exploring #adventure #view #milliondollarview (at Cap Gaspé) https://www.instagram.com/p/B1Z-_NmAKwd/?igshid=w3opnn3ze327

#capgaspé#montsaintalban#forillonnationalpark#parkscanada#keepexploringcanada#explorecanada#exploring#adventure#view#milliondollarview

0 notes

Photo

Le Parc du Forillon, c'est :

- un parc accessible gratuitement avec la carte “Parcs Canada”

- la plage du Cap-Bon-Ami où l'on peut pique-niquer en regardant les phoques se marrer

- la tour d'observation du Mont Saint-Alban d'où on peut voir des baleines

- le sentier du bout du monde qui donne une vue imprenable sur le golfe du Saint Laurent et l'île d'Anticosti

- le petit phare de Cap Gaspe

- la fin du Sentier des Appalaches, premier GR nord américain, long de 650 km, pour les courageux qui l'auraient commencé à Matapedia

- le fleuve Saint-Laurent qui se prend pour une mer

- des sentiers forestiers où l'on peut croiser des ours (paraît-il)

- un véritable bol d'air et de nature

- et une bière bien méritée !

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

i found a new chill spot at the edge of a small rugged cliff just in front of Fort du Mont Alban ❤️ it’s hidden in plain sight 😅 awesome view of Villefranche-sur-Mer and Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat from this spot ❤️ Nice, France 🇫🇷 #amazingadventuresofbeaujethro #nice #nice06 #france #frenchriviera #france #ilovenice #nicetourisme #lesud #fierdusud #villedenice #alpesmaritimes #cotedazur #villefranchesurmer #saintjeancapferrat #randonnée #chill #sunday #montboron #montalban #europe #nissalabella #ultraboost #ultraboost20 #adidas #summer #spring #soleil #sun #mediterranean (at Fort du mont Alban) https://www.instagram.com/p/CAkt1E2KNCN/?igshid=7n0ofwd3j96z

#amazingadventuresofbeaujethro#nice#nice06#france#frenchriviera#ilovenice#nicetourisme#lesud#fierdusud#villedenice#alpesmaritimes#cotedazur#villefranchesurmer#saintjeancapferrat#randonnée#chill#sunday#montboron#montalban#europe#nissalabella#ultraboost#ultraboost20#adidas#summer#spring#soleil#sun#mediterranean

0 notes

Text

La colline du château, un incontournable

La colline du Château L’"Acropole" antique :

Les premiers témoignages de vie d'une tribu autochtone datent du Xe siècle Av JC. Dès le IIIe siècle de notre ère, ils avaient des contacts avec les Grecs Phocéens, à qui l'on attribut le nom du site "Nikaïa", la victorieuse. On pense aujourd'hui que ce nom ne renvoie pas à une "victorieuse" bataille entre Les Grecs et les Ligures mais que le nom de Nice renvoie à une racine ligure "nis", qui signifie la source. Or, au pied du Château, et jusqu’à une époque récente, une source jaillissait sur la plage, permettant l’approvisionnement en eau douce des navires de passage et des pêcheurs. Cette source explique sans doute pourquoi les Grecs s’attardèrent ici.

Dans l'antiquité, Nikaïa s'étale définitivement au pied de la colline, et quand les invasions barbares rendent la plaine dangereuse et Cemenelum la romaine inhabitable, les habitants se réfugient sur son sommet.

Au moyen-âge, la ville haute :

Depuis le IXe siècle, Nice est sous la domination des comtes de Provence.

Dès le XIe siècle, on trouve trace du "castrum" de Nice. Une enceinte protégeait la plate-forme inférieure au nord du Château. A l’intérieur de cette enceinte s’établit une ville de quelques milliers d’habitants, avec ses églises, ses couvents, son marché, ses hôpitaux, ses tours nobles. Au XIIIè siècle encore, toute la ville de Nice est concentrée sur la colline.

Au cours du XIVe siècle, la ville basse s’est développée dans la plaine, jusqu'au cours du Paillon. Elle est dotée d’un rempart longeant partiellement le fleuve. Le château des comtes occupe sur la colline l’emplacement le plus élevé, le belvédère actuel. Il abrite l’administration de la viguerie*. Autour de la citadelle où sont les officiers et la garnison qui défendent la ville, se trouvent la cathédrale Sainte-Marie et des habitations de notables niçois.

Au temps du baroque, la forteresse des Ducs de Savoie :

Suite à la dédition de Nice à la Savoie, en 1388, le Château, " Castrum Magnum ", sera modifié, vers 1440 par le Duc Amédée VIII puis par Louis Ier. En 1520 des remaniements sont exécutés sur le flanc nord de la citadelle avec l’adjonction de trois bastions semi-circulaires destinés à en renforcer la partie la plus vulnérable.

Après le siège de Nice de 1543 (Catherine Ségurane), le Duc Emmanuel Philibert décide de renforcer le système défensif : entre 1550 et 1580, toute la population de la colline doit la quitter et s’installer dans l’actuel Vieux-Nice.

Les travaux de fortification, effectués à partir de 1560, englobent la citadelle de Nice, ses remparts, le fort du Mont-Alban, la citadelle de Villefranche et celle de Saint-Hospice au Cap-Ferrat. L’antique muraille médiévale est conservée, le plateau inférieur (où se trouvent les cimetières aujourd’hui), est doté d’une muraille bastionnée " moderne ", épaisse et basse, moins sensible aux tirs de l’artillerie. Cette muraille se verra complétée d’ouvrages supplémentaires tout au long du XVIIe siècle. Pour le ravitaillement en eau, on creusa un puits quidescendait du sommet de la colline jusqu’au niveau de la mer, atteignant la source fondatrice, et qui est aujourd’hui occupé par la cage de l’ascenseur.

Cet ensemble fortifié découragera les adversaires des Savoie un siècle et demi durant.

Mais l’armée française de Catinat, forte de 10 000 hommes, met le siège devant Nice en mars 1691. Les défenseurs de la citadelle, très inférieurs en nombre, ne se rendent qu’après un bombardement intense qui entraîne l’explosion de la poudrière du donjon. La place forte demeure aux mains des Français pour cinq années jusqu’au traité de Turin en 1696 qui rendit ses domaines au duc de Savoie.

Lors de la guerre de Succession d’Espagne, en avril 1705, la ville capitule devant les assauts français, de même que Villefranche, le Mont-Alban et Saint-Hospice. La forteresse ne résiste que quelques semaines et capitule au début de 1706.

Louis XIV décide alors d’en finir avec la redoutable place forte de Nice et en ordonne la destruction complète, qui sera exécutée à partir du printemps 1706, en quelques mois.

Aujourd'hui, le jardin romantique :

Le conseil de la Ville crée dès 1821, un premier jardin public. Sa gestion est confiée à Antoine Risso, célèbre naturaliste et botaniste niçois, qui transforme le terrain vague parsemé de ruines en un jardin botanique doublé d’un parc destiné à l’agrément des premiers touristes et hivernants.

Après 1860 on y acclimate des essences variées de conifères et de feuillus. De nouveaux escaliers aménagés depuis les Ponchettes desservent la tour Bellanda, reconstruite en 1825.

La cascade est construite en 1885 sur le site de l’antique donjon.

Depuis les années 1860, à l’initiative d’un résident écossais, sir Thomas Coventry More, résonne du canon de Midi.

Dans les années 1950-1960, les vestiges de la cathédrale sont mis à jour par plusieurs campagnes de fouilles.

0 notes

Text

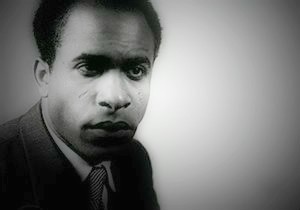

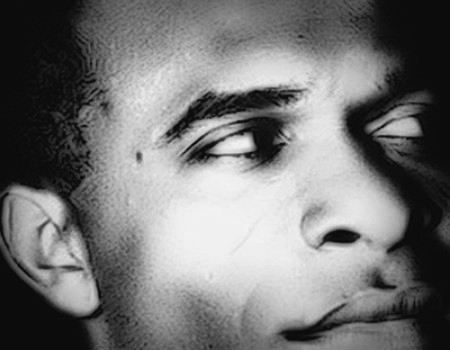

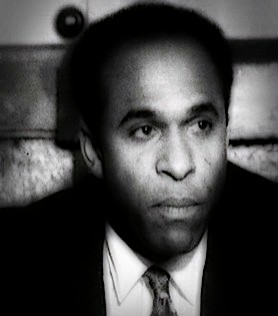

Franz Fanon

Frantz Omar Fanon (French pronunciation: [fʁɑ̃ts fanɔ̃]; 20 July 1925 – 6 December 1961) was a Martiniquais-French psychiatrist, philosopher, revolutionary, and writer whose works are influential in the fields of post-colonial studies, critical theory, and Marxism. As an intellectual, Fanon was a political radical, Pan-Africanist, and Marxist humanist concerned with the psychopathology of colonization, and the human, social, and cultural consequences of decolonization.

In the course of his work as a physician and psychiatrist, Fanon supported the Algerian War of Independence from France, and was a member of the Algerian National Liberation Front. For more than five decades, the life and works of Frantz Fanon have inspired national liberation movements and other radical political organizations in Palestine, Sri Lanka, South Africa, and the United States. In What Fanon Said: A Philosophical Introduction To His Life And Thought, leading Africana scholar and contemporary philosopher Lewis R. Gordon remarked that "Fanon's contributions to the history of ideas are manifold. He is influential not only because of the originality of his thought but also because of the astuteness of his criticisms...He developed a profound social existential analysis of antiblack racism, which led him to identify conditions of skewed rationality and reason in contemporary discourses on the human being."

Biography

Early life

Frantz Fanon was born on the Caribbean island of Martinique, which was then a French colony and is now a French département. His father, Félix Casimir Fanon, was a descendant of enslaved Africans and indentured Indians and worked as a customs agent. His mother, Eléanore Médélice, was of black Martinician and white Alsatian descent and worked as a shopkeeper. Fanon was the youngest of four sons in a family of eight children, two of whom died in childhood. Fanon's family was socio-economically middle-class. They could afford the fees for the Lycée Schoelcher, then the most prestigious high school in Martinique, where Fanon had the writer Aimé Césaire as one of his teachers.

Martinique and World War II

After France fell to the Nazis in 1940, Vichy French naval troops were blockaded on Martinique. Forced to remain on the island, French sailors took over the government from the Martiniquan people and established a collaborationist Vichy regime. In the face of economic distress and isolation under the blockade, they instituted an oppressive regime; Fanon described them as taking off their masks and behaving like "authentic racists." Residents made many complaints of harassment and sexual misconduct by the sailors. The abuse of the Martiniquan people by the French Navy influenced Fanon, reinforcing his feelings of alienation and his disgust with colonial racism. At the age of seventeen, Fanon fled the island as a "dissident" (the coined word for French West Indians joining Gaullist forces), traveling to British-controlled Dominica to join the Free French Forces.

He enlisted in the Free French army and joined an Allied convoy that reached Casablanca. He was later transferred to an army base at Béjaïa on the Kabylie coast of Algeria. Fanon left Algeria from Oran and served in France, notably in the battles of Alsace. In 1944 he was wounded at Colmar and received the Croix de guerre. When the Nazis were defeated and Allied forces crossed the Rhine into Germany along with photo journalists, Fanon's regiment was "bleached" of all non-white soldiers. Fanon and his fellow Afro-Caribbean soldiers were sent to Toulon (Provence). Later, they were transferred to Normandy to await repatriation.

During the war, Fanon was exposed to severe European anti-black racism. For example, white women liberated by black soldiers, often preferred to dance with fascist Italian prisoners, rather than fraternize with their liberators.

In 1945, Fanon returned to Martinique. He lasted a short time there. He worked for the parliamentary campaign of his friend and mentor Aimé Césaire, who would be a major influence in his life. Césaire ran on the communist ticket as a parliamentary delegate from Martinique to the first National Assembly of the Fourth Republic. Fanon stayed long enough to complete his baccalaureate and then went to France, where he studied medicine and psychiatry.

Fanon was educated in Lyon, where he also studied literature, drama and philosophy, sometimes attending Merleau-Ponty's lectures. During this period, he wrote three plays, which are lost. After qualifying as a psychiatrist in 1951, Fanon did a residency in psychiatry at Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole under the radical Catalan psychiatrist François Tosquelles. He invigorated Fanon's thinking by emphasizing the role of culture in psychopathology.

After his residency, Fanon practised psychiatry at Pontorson, near Mont Saint-Michel, for another year and then (from 1953) in Algeria. He was chef de service at the Blida–Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in Algeria. He worked there until being deported in January 1957.

France

In France while completing his residency, Fanon wrote and published his first book, Black Skin, White Masks (1952), an analysis of the negative psychological effects of colonial subjugation upon Black people. Originally, the manuscript was the doctoral dissertation, submitted at Lyon, entitled "Essay on the Disalienation of the Black"; the rejection of the dissertation prompted Fanon to publish it as a book. For his doctor of philosophy degree, he submitted another dissertation of narrower scope and different subject. Left-wing philosopher Francis Jeanson, leader of the pro-Algerian independence Jeanson network, read Fanon's manuscript and insisted upon the new title; he also wrote the epilogue. Jeanson was a senior book editor at Éditions du Seuil, in Paris.

When Fanon submitted the manuscript of Black Skin, White Masks (1952) to Seuil, Jeanson invited him for an editor–author meeting; he said it did not go well as Fanon was nervous and over-sensitive. Despite Jeanson praising the manuscript, Fanon abruptly interrupted him, and asked: "Not bad for a nigger, is it?" Jeanson was insulted, became angry, and dismissed Fanon from his editorial office. Later, Jeanson said he learned that his response to Fanon’s discourtesy earned him the writer's lifelong respect. Afterward, their working and personal relationship became much easier. Fanon agreed to Jeanson’s suggested title, Black Skin, White Masks.

Algeria

Fanon left France for Algeria, where he had been stationed for some time during the war. He secured an appointment as a psychiatrist at Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital. He radicalized his methods of treatment, particularly beginning socio-therapy to connect with his patients' cultural backgrounds. He also trained nurses and interns. Following the outbreak of the Algerian revolution in November 1954, Fanon joined the Front de Libération Nationale, after having made contact with Dr Pierre Chaulet at Blida in 1955.

In The Wretched of the Earth (1961, Les damnés de la terre), published shortly before Fanon's death, the writer defends the right of a colonized people to use violence to gain independence. In addition, he delineated the processes and forces leading to national independence or neocolonialism during the decolonization movement that engulfed much of the world after World War II. In defence of the use of violence by colonized peoples, Fanon argued that human beings who are not considered as such (by the colonizer) shall not be bound by principles that apply to humanity in their attitude towards the colonizer. His book was censored by the French government.

Fanon made extensive trips across Algeria, mainly in the Kabyle region, to study the cultural and psychological life of Algerians. His lost study of "The marabout of Si Slimane" is an example. These trips were also a means for clandestine activities, notably in his visits to the ski resort of Chrea which hid an FLN base. By summer 1956 he wrote his "Letter of resignation to the Resident Minister" and made a clean break with his French assimilationist upbringing and education. He was expelled from Algeria in January 1957, and the "nest of fellaghas [rebels]" at Blida hospital was dismantled.

Fanon left for France and travelled secretly to Tunis. He was part of the editorial collective of El Moudjahid, for which he wrote until the end of his life. He also served as Ambassador to Ghana for the Provisional Algerian Government (GPRA). He attended conferences in Accra, Conakry, Addis Ababa, Leopoldville, Cairo and Tripoli. Many of his shorter writings from this period were collected posthumously in the book Toward the African Revolution. In this book Fanon reveals war tactical strategies; in one chapter he discusses how to open a southern front to the war and how to run the supply lines.

Death

Upon his return to Tunis, after his exhausting trip across the Sahara to open a Third Front, Fanon was diagnosed with leukemia. He went to the Soviet Union for treatment and experienced some remission of his illness. When he came back to Tunis once again, he dictated his testament The Wretched of the Earth. When he was not confined to his bed, he delivered lectures to Armée de Libération Nationale (ALN) officers at Ghardimao on the Algero-Tunisian border. He made a final visit to Sartre in Rome. In 1961, the CIA arranged a trip to the U.S. for further leukemia treatment.

Fanon died in Bethesda, Maryland, on 6 December 1961, under the name of "Ibrahim Fanon", a Libyan nom de guerre that he had assumed in order to enter a hospital in Rome after being wounded in Morocco during a mission for the Algerian National Liberation Front. He was buried in Algeria after lying in state in Tunisia. Later, his body was moved to a martyrs' (chouhada) graveyard at Ain Kerma in eastern Algeria. Frantz Fanon was survived by his French wife Josie (née Dublé), their son Olivier Fanon, and his daughter from a previous relationship, Mireille Fanon-Mendès France. Josie committed suicide in Algiers in 1989. Mireille became a professor at Paris Descartes University and a visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley, in international law and conflict resolution. She has also worked for UNESCO and the French National Assembly, and serves as president of the Frantz Fanon Foundation. Olivier married Valérie Fanon-Raspail, who manages the Fanon website.

Work

Black Skin, White Masks is one of Fanon's important works. In Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon psychoanalyzes the oppressed Black person who is perceived to have to be a lesser creature in the White world that s/he lives in, and studies how navigates the world through a performance of White-ness. Particularly in discussing language, he talks about how the black person's use of a colonizer's language is seen by the colonizer as predatory, and not transformative, which in turn may create insecurity in the black's consciousness. He recounts that he himself faced many admonitions as a child for using Creole French instead of "real French," or "French French," that is, "white" French. Ultimately, he concludes that "mastery of language [of the white/colonizer] for the sake of recognition as white reflects a dependency that subordinates the black's humanity".

Although Fanon wrote Black Skin, White Masks while still in France, most of his work was written in North Africa. It was during this time that he produced works such as L'An Cinq, de la Révolution Algérienne in 1959 (Year Five of the Algerian Revolution, later republished as Sociology of a Revolution and later still as A Dying Colonialism). Fanon's original title was "Reality of a Nation"; however, the publisher, François Maspero, refused to accept this title.

Fanon is best known for the classic analysis of colonialism and decolonization, The Wretched of the Earth. The Wretched of the Earthwas first published in 1961 by Éditions Maspero, with a preface by Jean-Paul Sartre. In it Fanon analyzes the role of class, race, national culture and violence in the struggle for national liberation. Both books established Fanon in the eyes of much of the Third World as the leading anti-colonial thinker of the 20th century.

Fanon's three books were supplemented by numerous psychiatry articles as well as radical critiques of French colonialism in journals such as Esprit and El Moudjahid.

The reception of his work has been affected by English translations which are recognized to contain numerous omissions and errors, while his unpublished work, including his doctoral thesis, has received little attention. As a result, Fanon has often been portrayed as an advocate of violence (it would be more accurate to characterize him as a dialectical opponent of nonviolence) and his ideas have been extremely oversimplified. This reductionist vision of Fanon's work ignores the subtlety of his understanding of the colonial system. For example, the fifth chapter of Black Skin, White Masks translates, literally, as "The Lived Experience of the Black" ("L'expérience vécue du Noir"), but Markmann's translation is "The Fact of Blackness", which leaves out the massive influence of phenomenology on Fanon's early work.

For Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth, the colonizer's presence in Algeria is based on sheer military strength. Any resistance to this strength must also be of a violent nature because it is the only "language" the colonizer speaks. Thus, violent resistance is a necessity imposed by the colonists upon the colonized. The relevance of language and the reformation of discourse pervades much of his work, which is why it is so interdisciplinary, spanning psychiatric concerns to encompass politics, sociology, anthropology, linguistics and literature.

His participation in the Algerian Front de Libération Nationale from 1955 determined his audience as the Algerian colonized. It was to them that his final work, Les damnés de la terre (translated into English by Constance Farrington as The Wretched of the Earth) was directed. It constitutes a warning to the oppressed of the dangers they face in the whirlwind of decolonization and the transition to a neo-colonialist, globalized world.

An often overlooked aspect of Fanon's work is that he did not like to write his own pieces. Instead, he would dictate to his wife, Josie, who did all of the writing and, in some cases, contributed and edited.

Influences

Fanon was influenced by a variety of thinkers and intellectual traditions including Jean-Paul Sartre, Lacan, Négritude, and Marxism.

Aimé Césaire was a particularly significant influence in Fanon's life. Césaire, a leader of the Négritude movement, was teacher and mentor to Fanon on the island of Martinique. Fanon was first introduced to Négritude during his lycée days in Martinique when Césaire coined the term and presented his ideas in La Revue Tropique, the journal that he edited with his wife, in addition to his now classic Cahier d'un retour au pays natal. Fanon referred to Césaire's writings in his own work. He quoted, for example, his teacher at length in "The Lived Experience of the Black Man", a heavily anthologized essay from Black Skins, White Masks.

Legacy

Fanon has had an influence on anti-colonial and national liberation movements. In particular, Les damnés de la terre was a major influence on the work of revolutionary leaders such as Ali Shariati in Iran, Steve Biko in South Africa, Malcolm X in the United States and Ernesto Che Guevara in Cuba. Of these only Guevara was primarily concerned with Fanon's theories on violence; for Shariati, Biko and also Guevara the main interest in Fanon was "the new man" and "black consciousness" respectively.

Bolivian indianist Fausto Reinaga also had some Fanon influence and he mentions The Wretched of the Earth in his magnum opus La Revolución India, advocating for decolonisation of native South Americans from European influence. In 2015 Raúl Zibechi argued that Fanon had become a key figure for the Latin American left.

Fanon's influence extended to the liberation movements of the Palestinians, the Tamils, African Americans and others. His work was a key influence on the Black Panther Party, particularly his ideas concerning nationalism, violence and the lumpenproletariat. More recently, radical South African poor people's movements, such as Abahlali baseMjondolo (meaning 'people who live in shacks' in Zulu), have been influenced by Fanon's work. His work was a key influence on Brazilian educationist Paulo Freire, as well.

Fanon has also profoundly affected contemporary African literature. His work serves as an important theoretical gloss for writers including Ghana's Ayi Kwei Armah, Senegal's Ken Bugul and Ousmane Sembène, Zimbabwe's Tsitsi Dangarembga, and Kenya's Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o. Ngũgĩ goes so far to argue in Decolonizing the Mind (1992) that it is "impossible to understand what informs African writing" without reading Fanon's Wretched of the Earth.

Fanon has also influenced the formation in 2013 of a new South African political party, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) by the former president of the ANC Youth League, Julius Malema.

The Caribbean Philosophical Association offers the Frantz Fanon Prize for work that furthers the decolonization and liberation of mankind.

Fanon's writings on black sexuality in Black Skin, White Masks have garnered critical attention by a number of academics and queer theory scholars. Interrogating Fanon's perspective on the nature of black homosexuality and masculinity, queer theory academics have offered a variety of critical responses to Fanon's words, balancing his position within postcolonial studies with his influence on the formation of contemporary black queer theory.

Wikipedia

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Originally published:

http://www.phototraces.com/deconstructing-photo/forillon-national-park-from-above-at-sunrise-quebec/

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Fragment of an Architectural Frieze

ARTIST CULTURE Zapotec

PERIOD Late Classic period, 600–909

DATE c.600–909

MATERIAL Terracotta with whitewash and buff pigment

FROM Oaxaca state, México

PROVENANCE Private collection [1]

by 1966 -

William Spratling (1900-1967), Taxco, Guerrero, Mexico [2]

- 1966

Harry A. Franklin Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA, USA

1966 - 1978

Morton D. May (1914-1983), St. Louis, MO, purchased from Harry A. Franklin Gallery [3]

1978 -

Saint Louis Art Museum, given by Morton D. May [4]

Notes:

This object is one of 18 architectural fragments accessioned by the Museum in 1978 [351:1978.1-.18]. Although all the fragments were donated by Morton D. May, May purchased them from two different sources. 351:1978.3, .5, .6, .8, .9, .10, .11, .12, .14, .17, .18 share the same provenance.

[1] A letter dated July 25, 1966 from author Frank H. Boos to Museum curator Philippa D. Shaplin notes this tile was previously in an unnamed private collection [Curatorial Office, Primitive and Precolumbian Art Departmental Correspondence, Archives, Saint Louis Art Museum].

[2] A letter dated October 20, 1966 from Boos to Shaplin identifies Spratling as owning this tile after the private collector [SLAM document files]. In a letter dated May 8, 1967 from Boos to Shaplin regarding the purchase of an additional tile [218:1978], Boos stated the tile [218:1978] was "in the possession of the one who owned the first lot [351:1978.3, .5, .6, .8, 9, .10, .11, .12, .14, .17, .18] of them" [Curatorial Office, Primitive and Precolumbian Art Departmental Correspondence, Archives, Saint Louis Art Museum]. A letter dated May 11, 1967 from Shaplin to Boos clearly identifies the tile [218:1978] was "obtained from Spratling" [Curatorial Office, Primitive and Precolumbian Art Departmental Correspondence, Archives, Saint Louis Art Museum]. Two additional letters from Boos to Shaplin dated May 29, 1967 and June 3, 1967 identify the tile [218:1978] as "Spratling's "newly-discovered" tile" and "Spratling's new found tile" [SLAM document files].

[3] An invoice dated March 30, 1966 from Harry A. Franklin Gallery to May documents this purchase, listed as "Monte Alban (Zapotec) frieze terracotta" [May Archives, Saint Louis Art Museum].

SLAM

35 notes

·

View notes

Video

Sunrise at Forillon National Park by Photo Traces

0 notes