#Clytemnestra wants revenge on her daughter's murderer

Text

The contrast between Clytemnestra's prayer for Agamemnon to come home safely from Troy vs. Elektra's...

#please feel free to ignore this#I'm reading Elektra#Elektra misses her beloved father#Clytemnestra wants revenge on her daughter's murderer#The description of her grief on her return to Mycenae is almost like overwhelming#Originally I got the impression that Iphigenia was the favorite but she's also just like#How am I supposed to look at my children and know I can't protect them? Am I just raising more cattle for slaughter?#Better not to have precious memories to hurt me someone else raise them#Also her description of like looking at Orestes and feeling nothing#She wishes Iphigenia had died as a child so Clytemnestra wouldn't have had to hear her daughter's wishes for her own future#Jennifer Saint gets it

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Originally performed in 458 BC, Agamemnon is the first play in Aeschylus' Oresteia trilogy, which also includes Libation Bearers and Eumenides. The play is set in front of the palace of Argos and begins with a Watcher noticing a beacon fire which signals the return of Argos’ king, Agamemnon, ten years after sailing away to conquer Troy. The information is subsequently confirmed by a Herald, soon after which Agamemnon arrives in a chariot that also carries Cassandra, the Trojan princess, a spoil of war and a new bedmate of Agamemnon. Regardless of this, Clytemnestra welcomes her husband gushingly, eventually even persuading him to enter his palace by treading over a purple tapestry more becoming for gods than humans. It is a hubristic act, with which Clytemnestra tries to give further justification to what she intends to do next: murder Agamemnon. Left behind, Cassandra, a prophetess cursed not to be believed by anyone, senses this outcome. Even so, she decides to enter the palace as well, believing this to be her inevitable fate. Indeed, it is: Clytemnestra murders both Agamemnon and his lover, and defends this decision before the Chorus as a just act of revenge for Agamemnon having sacrificed their daughter, Iphigenia, to appease the gods for a transgression of his own – namely, killing Artemis’ sacred deer. However, that’s not the whole story, as we soon learn from Clytemnestra’s lover (and Agamemnon’s cousin) Aegisthus, who unexpectedly appears on stage. He is in on the murder plot as well, as a way to avenge his brothers, who had been not only slaughtered by Agamemnon’s father, Atreus, but also cooked and served as dinner to Aegisthus’ father, Thyestes. The Argive Elders bemoan this sudden turn of events and warn that Agamemnon’s son, Orestes, will inevitably return to look for v3ngeance. Source: greekmythology.com

Want to own my Illustrated Greek myth book? Support my kickstarter for my book "lockett Illustrated: Greek Gods and Heroes" coming in October.You can also sign up for my free email newsletter for free hi-res art and a big discount on my etsy print shop. please check my LINKTREE 🤘❤️🏛😁

https://linktr.ee/tylermileslockett

#pagan#hellenism#greek mythology#tagamemnon#mythology tag#percyjackson#dark academia#greek#greekmyths#classical literature#percy jackon and the olympians#pjo#homer#iliad#classics#mythologyart#art#artists on tumblr#odyssey#literature#ancientworld#ancienthistory#ancient civilizations#ancientgreece#olympians#greekgods#agamemnon#troy#trojanwar

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

poll time!! you guys voted here, and now the poll’s ready!

no gods included in the poll haha but if you want some background to the characters who made it in, check below the poll!!

AGAMEMNON (king of Mycenae, see: the Iliad)

Filicide (kills his daughter Iphigenia, albeit at the request of Artemis)

Dishonours his allies (takes Achilles’ war prize Briseis)

Murder (kills his wife Clytemnestra’s first husband and her infant son)

Rape (Cassandra became his concubine after the sack of Troy)

ATREUS (king of Mycenae, Agamemnon’s father)

Murder (kills his half-brother Chrysippus)

Hubris (promises Artemis a golden lamb, but then hides it from her to avoid having to sacrifice it)

Cooked his brother Thyestes’ sons and forced his brother to eat them

THYESTES (king of Olympia, brother of Atreus)

Murder (kills his half-brother Chrysippus in order to take the throne of Olympia from him)

Adultery (sleeps with his brother Atreus’ wife Aerope)

Rape + Incest (rapes his own daughter Pelopeia in order to conceive a son to kill his brother Atreus, as prescribed by an oracle)

NIOBE (daughter of Tantalus, and wife of Amphion who, with his brother Zethus, built the walls of Thebes)

Hubris (boasted of her great blessedness in having produced 7 sons and 7 daughters where the titanide Leto had only managed to produce a single son and a single daughter (Apollo and Artemis)

TANTALUS (ancestor of Atreus, Thyestes, Agamemnon, and Niobe)

Filicide (kills his son Pelops)

Hubris (steals ambrosia and nectar from the table of Zeus, and then tricks the gods into consuming his son Pelops’ flesh to test their omniscience)

MINOS (king of Crete)

Betrayal (tricks Scylla into sharing with him the secret to killing her father, and then punishes her for betraying her father for him by tying her to a boat and dragging her till she drowned AND imprisons Daedalus and his son Icarus within the labyrinth they built for Minos purely to protect the secret of the labyrinth)

Hubris (substitutes the white bull Poseidon sends him as a sacrifice for another bull, against the god’s wishes)

Murder (orders Athens to sacrifice 7 young men and women from the city in return for Minos not attacking them)

THESEUS (king of Athens)

Betrayal (abandons Ariadne on the island of Naxos after she betrays her country to help him navigate the labyrinth (though this may have been at the behest of the gods, sources differ))

Kidnapping (kidnaps Helen (future queen of Sparta, pre-Iliad) to make her his bride)

Hubris (dares to kidnap the goddess Persephone from the Underworld as a bride for his friend Pirithous)

Filicide (has Poseidon kill his son Hippolytus after hearing that the boy attempted to force himself on Phaedra, Theseus’ wife and Hippolytus’ step-mother, which was not true)

LYCAEON (king of Arcadia)

Filicide (kills his son Nyctimus)

Hubris (attempts to trick Zeus into consuming his son Nyctimus’ flesh to test his omniscience)

LAIUS (king of Thebes)

Rape + Kidnapping (defiled and abducted Chrysippus who was the son of Pelops, the king who welcomed Laius into his city after Amphion and Zethus usurped Laius’ father’s throne in Thebes)

Attempted filicide (tries to kill his infant son Oedipus when a prophecy warns Laius that the only way to save his city is for him to die childless)

MEDEA (princess of Colchis)

Murder (kills her brother to distract her father while her lover Jason escaped with the Golden Fleece from Colchis AND tricks Pelias’ own daughters into murdering him (though these things may be credited to the influence of Eros’ arrow which had struck Medea by the will of the gods))

Petty revenge (curses all Cretans to never be able to tell the truth after the Cretan Idomeneus judges the Nereid Thetis to be more beautiful than her)

Filicide (kills her children by Jason in revenge for him abandoning her for Creusa, princess of Corinth)

Conspirator (attempts to deny Theseus of his royal birthrights by trying to convince Theseus’ father Aegeus that Theseus was not his son but an imposter who needed to be killed)

#medea has done some pretty nasty things and i wanted more women in the poll so she’s here. i still love her thoughNn#no Circe because i’m on the fence about whether she’s a goddess or not and couldn’t decide if she was eligible for the poll#poll

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

masterpost of boe name references/sources

I really wanted to make a post about the names of certain (and by certain I mean Wake, We Suffer, Crown Him with Many Crowns, and Unjust Hope) BoE members because I’m

a) a huge-ass nerd who loves doing research and

b) super fascinated by all Tazmuir’s references so here goes nothing lmao

(If we get any of the other names in full, I’ll add them here too!)

First on the docket: Griddle’s mom (has got it going on). Wake’s name has been pretty thoroughly “decrypted,” for lack of a better word, so I’m just going to compile it all here for funsies.

Awake Remembrance of These Valiant Dead Kia Hua Ko Te Pai Snap Back to Reality Oops There Goes Gravity

Awake Remembrance of These Valiant Dead

A reference to Shakespeare’s Henry V, Act I, Scene II. For context: in the scene, Henry demands to know if his claim to the French throne is legitimate. His advisors, the Bishops of Ely and Canterbury and 2 other nobles (Exeter and Westmoreland), state that it is, and encourage him to pursue war with France, reminding him of the glory of his ancestors, “the former lions of [his] blood” (I.II. sorry I don’t have line numbers!)

ELY

Awake remembrance of these valiant dead

And with your puissant arm renew their feats:

You are their heir; you sit upon their throne;

The blood and courage that renowned them

Runs in your veins; and my thrice-puissant liege

Is in the very May-morn of his youth,

Ripe for exploits and mighty enterprises.

EXETER

Your brother kings and monarchs of the earth

Do all expect that you should rouse yourself,

As did the former lions of your blood.

Kia Hua Ko Te Pai

A reference to Aotearoa’s (New Zealand’s) national anthem, in te reo (Maori), “E Ihowā Atua.” The line translates as “may/let goodness flourish.”

Snap Back to Reality Oops There Goes Gravity

you better LOSE YOURSELF IN THE MUSIC THE MOMENT YOU OWN IT YOU BETTER NEVER LET IT GO (OH)

Moving on! We Suffer under the cut (pun not intended but I’m sorry this is so text-heavy!)

We Suffer and We Suffer

We Suffer and We Suffer

(Likely) a reference to Robert Fagles’ translation of Aeschylus’s Agamemnon. The line, as Fagles translates it, is “but Justice turns the balance scales, sees that we suffer and we suffer and we learn” (250-1).

For context: A watchman waits for a signal confirming a Greek victory in Troy. He laments his boredom and the current state of Mycenae and the House of Atreus, and complains of Clytemnestra, Agamemnon’s wife, and her apparent lack of femininity: “She in whose woman's breast beats heart of man” (I.I.still no fucking line numbers!), not knowing of her plot to kill Agamemnon as he returns home from war, in revenge for his sacrifice of their daughter Iphigenia for favorable winds to sail for Troy. The chorus then enters, and praises the gods while catching everyone up on the story thus far, including Agamemnon’s sacrifice of Iphigenia at the behest of Calchas, the seer.

(If interested in Iphigenia’s story, check out Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides.)

It’s also worth keeping in mind that Agamemnon is the first play in a series of three by Aeschylus, the Oresteia, which details the murder of Agamemnon and its fallout, the downfall of the House of Atreus and the end of its curse, and thematically discusses questions of justice, retaliation, and revenge. Very apropos.

Note: the translation of this line, as far as I’ve dug (so not super far), seems to be specific to Fagles. Other translators of Agamemnon, such as Anne Carson and E.D.A Morshead translate it differently.

Anne Carson: “Justice tips her scales so that we learn by suffering” (I.I.179-180)

E.D.A Morshead: “This wage from justice' hand do sufferers earn / The future to discern ” (I.I.deep sigh)

Moving on!

Crown Him with Many Crowns

Crown Him with Many Crowns

A reference to a Christian hymn of the same name, written by Matthew Bridges. Traditionally set to the tune of a song called “Diademata” (itself derived from the Greek word for “crown”) by English organist and composer Sir George Job Elvey (the song was apparently composed for the hymn), but arrangements have been updated in the recent past.

This one is tricky, because this song is Very John, so... perhaps Crown is the link between the upper echelons of the empire and BoE?

Much to think about. Next!

Some relevant verses:

Crown him with many crowns,

The Lamb upon his throne;

Hark! how the heavenly anthem drowns

All music but its own:

Awake, my soul, and sing

Of him who died for thee,

And hail him as thy matchless king

Through all eternity.

[...]

Crown him the Lord of peace!

Whose power a scepter sways,

From pole to pole,--that wars may cease,

Absorbed in prayer and praise:

his reign shall know no end,

And round his pierced feet

Fair flowers of paradise extend

Their fragrance ever sweet.

Crown him the Lord of years!

The Potentate of time,--

Creator of the rolling spheres,

Ineffably sublime!

Glassed in a sea of light,

Where everlasting waves

Reflect his throne,--the Infinite!

Who lives,--and loves--and saves.

[...]

Crown him with crowns of gold,

All nations great and small,

Crown him, ye martyred saints of old,

The Lamb once slain for all;

The Lamb once slain for them

Who bring their praises now,

As jewels for the diadem

That girds his sacred brow.

Crown him the Son of God

Before the worlds began,

And ye, who tread where He hath trod,

Crown him the Son of Man;

Who every grief hath known

That wrings the human breast,

And takes and bears them for His own,

That all in him may rest.

Crown him the Lord of light,

Who o'er a darkened world

In robes of glory infinite

His fiery flag unfurled.

And bore it raised on high,

In heaven--in earth--beneath,

To all the sign of victory

O'er Satan, sin, and death.

Crown him the Lord of life

Who triumphed o'er the grave,

And rose victorious in the strife

For those he came to save;

His glories now we sing

Who died, and rose on high.

Who died, eternal life to bring

And lives that death may die.

[...]

Unjust Hope

Unjust Hope

Te Whaea, according to my search, is te reo (Maori) for “the Mother,” but... I think more in the sense of a title than a relationship, in context?

A reference to the poem “The Ikons” by New Zealand poet James K. Baxter. The line is as follows:

“Hard, heavy, slow, dark,

Or so I find them, the hands of Te Whaea

Teaching me to die. Some lightness will come later

When the heart has lost its unjust hope

For special treatment.” [...] (1-5)

There is soup made in this poem

And a river used in good old TLT context! (the context is death btw)

On a meta note, James K. Baxter was raised as not practicing any particular faith, or so I understand, but was a devout Catholic in his later years. He was also passionate about Maori culture in New Zealand and heavily embraced it, likely most exposed to it by his wife Jacquie Sturm, who was Maori herself - however, his reputation is not spotless and his treatment of women (including Jacquie) has been heavily criticized.

That said, this poem... oof

h e l p

“[...] and the fist of longing

Punches my heart, until it is too dark to see” (21-22)

And that’s all I have so far! As more information comes out (or the book) I’ll update this post as needed!

Thanks for reading!

#the locked tomb#tlt#blood of eden#awake remembrance of these valiant dead#gideon the ninth#nona the ninth#harrow the ninth#boe#god help me i went OVERBOARD will anyone actually read this? idk man you tell me#also i am SO SORRY if these look weird on mobile - it would be best to view this post on a desktop lol#also - should i put this on ao3? just for fun/easier to update?

178 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why do you think of Clytemnestra? I find her one of the most misunderstood characters because of comparisons between her and Penelope. She is worse because she cheated on Agamemnon and then killed him. Not many people seem to find the point of avenging their daughter Agamemnon sacrificed valid. As if she were supposed to be fine with it because her child's death served a great purpose and allowed Greeks to win. He cheated on her multiple times, he even had the nerve to bring Cassandra to his own home and expect Clytemnestra to welcome her. And she is the villain in this story. I've always preferred her over Penelope.

Oh I'm so glad that someone asked about my favorite Greek heroine ever. I'm a big Penelope fan, but this is a pro-women's violence account first.

Plagiarizing a bit from my Goodreads review, but: it's important to note here that the questions of "Was Agamemnon right to kill Iphigenia," "Was Clytemnestra right to kill Agamemnon," and "Was Orestes right to kill Clytemnestra" are all ENTIRELY separate questions. Each has its own considerations. Even if you concede that Agamemnon had no choice but to sacrifice his daughter, that doesn't change what his wife must do. A father kills a daughter, so this demands an answer, even if it is justified. Thus, a wife kills her husband, and this demands an answer, even if it is justified. The whole idea here is that once blood has been spilt, you can't just resolve things peaceably.

And the text absolutely supports this reading via the chorus saying “the father who breaks heaven’s law ruins his children [...] Evil begets evil." Which is the EXACT SAME LOGIC that Orestes uses to kill Clytemnestra in his own revenge. HE'S allowed to take vengeance, but she isn't. God forbid women do anything.

Orestes points out "For taking human life there is a payment that has to be paid." But he doesn't apply this logic to Clytemnestra's own killing. The chorus does make this connection, after describing Iphigenia's killing, "He takes what he wants - and he pays for it" implying that the payment is fate. The chorus even justifies it, "Evil for evil is justice. And justice is holy." So the point seems obvious; it's okay to do an evil thing as long as it is in exchange for an evil thing. But this logic just doesn't get to excuse Clytemnestra?? If she was wrong, so was everyone else.

Clytemnestra calls out this hypocrisy directly. As though on trial, she defends with "Why didn't you judge Agamemnon? He murdered his own daughter, my daughter [...] This man here was the criminal to be punished" implying that her actions are justified by the same logic as Orestes, the same logic as the chorus, evil for evil.

So to summarize, either everyone in this play is justified, or none of them are - because they’re all using the same excuse. And Aeschylus is not unconscious of this!! The play literally ends in a hung jury trial in which they can't decide who is justified.

History might have simplified Clytemnestra, but Aeschylus and the original audience saw her for the nuanced character she is.

#tagamemnon#Clytemnestra#all quoted from the Ted Hughes translation btw#The Orestia#can you believe there were no women in the original audience. fuck.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Observation

I'm reading a bunch of books about plot structure again, and one of them was specifically about breaking down plots to their basic elements in a way that lets you see how two works can have the same 'skeleton' while appearing wildly different. Looking at it from that angle, it occurred to me:

The stories of Demeter and Clytemnestra follow roughly the same plot - they just have different outcomes.

In the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, we get the story of Demeter and Persephone - the story that formed the basis of the Eleusinian Mysteries. Persephone is picking flowers when she is lured astray by one planted as a trap for her; once she tries to get it, Hades pops up from nowhere, yanks her onto his chariot, and goes off to the Underworld with her, having gotten permission from Zeus to forcibly marry her without consulting with Demeter, her mother. There's scholarly discussion about how this could be symbolic of the real grief experienced by ancient Greek mothers and daughters, who might well never see each other again after the daughter is married off, but in its own context - the lord of the Underworld claims the Maiden, plunging her mother into grief and anger, which turns into Demeter blighting the world until the other gods come to an accommodation with her which partially restores Persephone to her. Ultimately, however, Demeter is plunged back into mourning every half-year when Persephone must once more return to Hades, which results in winter for everyone else.

In the Oresteia, we open with Clytemnestra plotting murder; this is because, in the backstory, her husband Agamemnon tricked her into bringing their daughter Iphigeneia to him by pretending he has arranged an honorable marriage for the girl, only to sacrifice Iphigeneia to the goddess Artemis instead once he has her. Cue Clytemnestra plotting her revenge: she spends the whole Trojan War fantasizing about tricking Agamemnon into a position where she can kill him, just as he tricked her into putting Iphigeneia into a position to be sacrificed to Artemis. Fast-forward ten years; the Trojan War is over, Agamemnon comes home, Clytemnestra proceeds to get her revenge, and she and her boyfriend (who also wanted to avenge wrongs done to his family - specifically, he had some older siblings who met a rather gristly end at the hands of Agamemnon's already-deceased father) take over the government, with negative results for the polis, if we're to believe Electra in Libation-Bearers, anyway.

Agamemnon is, in a way, roughly analogous to Hades: a superior being (Zeus, Artemis) gives a powerful Figure From Greek Mythology (Hades, Agamemnon) permission to send a young woman to the Underworld, and in the process, her mother is tricked and bereaved. As a result, both Demeter and Clytemnestra go nuclear in their pursuit of revenge: Demeter inflicts massive crop damage, fully prepared to commit genocide upon humanity solely because the other gods enjoy receiving offerings from humans, and Clytemnestra breaks her marriage vows and then lures Agamemnon to his death. However, at that point, their stories diverge pretty sharply: even Zeus himself is apparently unable to force Demeter to come to Olympus or to allow anything to grow again against her will, and he is not able to prevent her from bringing winter back down upon the world every half-year whenever Persephone is re-removed from her due to the laws of godly physics as applied to pomegranates, because why not. Clytemnestra, however, is not a goddess - she is not even the child of a god or goddess, even though her own twin sister, Helen, is. Clytemnestra is a powerful woman...but just, at the end of the day, a human woman. Therefore, her revenge backfires onto her horribly: she who committed murder to avenge one of her daughters (Iphigeneia) is murdered by her son (Orestes) as part of a plot which included her surviving daughter (Electra). As a shade, she raises the Furies against Orestes, so that these ancient goddesses of vengeance drive him nearly mad...but because a greater power (Athena) can and does exert power (at one point, she threatens the Eumenides with Zeus's lightning-bolts, which she has access to, if they don't agree to her arbitration of the quarrel) over everyone else involved. Zeus could not curb Demeter, but his daughter can curb the Furies and bring them fully into line with the patriarchal system***.

There's stories in there. I know it. More than one. Just to sift them out and find something to do with them....

***For an interpretation of Oresteia which makes some sense out of the ending of Eumenides other than "lol, women unimportant and stupid," there's an interesting lecture by the Canadian classicist Ian Johnston, which can be viewed here: http://johnstoniatexts.x10host.com/lectures/oresteialecture.html

I quite like it, along with much of Professor Johnston's work, though it's still hard to come away without the impression that Aeschylus miiiiight have had Issues with women. However, this would hardly make Aeschylus the last writer whose skill (and point) was undermined by his prejudices.

#over analysis#greek mythology#greek gods#greek pantheon#homeric hymn to demeter#the orestia#demeter#zeus#hades#persephone#aeschylus#clytemnestra#orestes#agamemnon#electra#eumenides#athena#parallels#unexpected paralells#classics are fun#ancient greek drama#classical tragedy#tragedy

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

Not really a question but you know this trope of the son, once he grows up, killing/hurting/taking revenge on his father for abusing the mom? (I can't think of examples right now but it is a thing, right.)

So Claudia killing Lestat to free her and Louis is sort of a sex swapped version of this, which I find really interesting. Also kind of plays into the idea of how Claudia views Louis as the weaker one, at least mentally.

(Sorry, you've unlocked a Classics Rant)

I agree with the general principle and it feels very Greek tragedy, like a twist on Clytemnestra's murder of Agamemnon. In Aeschylus's play Agamemnon, the titular king is murdered by his wife in revenge for his sacrifice of their daughter, Iphigenia.

Like Claudia, she bides her time, playing up her "love" and waiting for Agamemnon to become vulnerable (him in the bathtub, Lestat while feeding), before betraying and killing him. In doing so, she also takes the throne from him and publicly unites with the lover Agamemnon had kept her from embracing. I think the parallels are pretty obvious, just a shuffling of rolls from a wife killing her husband as revenge and elevating her lover to a daughter killing one parent as revenge and elevating the other.

There's also a possible connection in the Oresteia between Claudia and Electra. In this case, we end up with Louis as Agamemnon and Lestat as Clytemnestra. In the play, Electra helps kill Clytemnestra, her mother, in revenge for the murder of her father, Agamemnon. Through this lens, Claudia sees Lestat as Louis' metaphorical "killer" and she takes revenge on Lestat for dragging him into vampirism and keeping him (and her) from having a life.

The story of Salome from the Bible (or the Oscar Wilde play, if you prefer) is another comparison I like, though it's less beat for beat. Salome, daughter of Herod Antipas, was promised anything she wanted by a doting father. Knowing her mother's grudge against John the Baptist, she asks for his head on a silver platter and receives it.

If Claudia is Salome, she's acting on behalf of a beloved parent, the mother or Louis. In this case, I see Herod as more a representation of her own power via Lestat and John the Baptist as the reality of Lestat, a figure beloved by the public but a direct threat to the preferred parent. It's not a perfect one-to-one, but I like the comparison anyway.

As to the second thing you mentioned, it's interesting how Claudia almost...infantilizes Louis? It's such a strange dynamic given how Louis treats Claudia, like a doll in his words. He kind of indicates that he knows how Claudia feels about that, but I don't know if he understands to what extent. It goes back to the question of where Claudia’s genuine love for her father ends and the manipulation begins. Maybe she herself doesn't know.

I think that's really because of her lack of humanity. All she's ever known is how to get what she needs from others through manipulation, luring kind adults into her trap. In the same way, an adult Claudia knows she can't survive on her own, so she ensures that Louis is where she wants him, wrapped around her little finger. I do believe she has real love for him, as least to the point that she's capable of that kind of emotion (we see it in her breakdown after realizing how disgusted and angry Louis is by her murder of Lestat), but I don't think she's even capable of selfless love.

I think the movie does a great job of portraying and contrasting her moments of genuine connection with Louis with the times she's using his love for her to get something (or blending the two, like her plea for Madeline). The two aren't mutually exclusive, but I think the choice of Louis as her primary guardian was as much about his weakness for her as it was her hatred for Lestat. He's more like a pet to her than a parent by the end, and her love is almost condescending. Maybe she resents that she's so dependent on someone she doesn't seem to think very highly of.

I definitely believe if she thought Lestat's presence was a more viable option for her long term wellbeing, she would've tolerated him. Instead, he was an obstacle, a barrier keeping Louis from being fully hers and I think that motivated her almost as much as hatred or a desire for freedom. Louis is her best bet and also all she has in the world. As long as Louis is Lestat’s partner, he can't be dedicated 100% to being her father, she'll never be the sole influence on him like she feels she needs to be.

Anyway, Claudia is an amazing character and we should talk about her more.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alecto, Atreus, and Analogues: Parallels between The Oresteia and The Locked Tomb

Okay, so mostly I just wanted an excuse to write a title with a colon in it.

what it says on the tin

So, some backstory. The Atreus house is a pretty famous and very cursed Greek Family (think Agamemnon and Menelaus (of Iliad fame), Clytemnestra (of Tumblr Girlboss fame) and Orestes (of “It’s rotten work / Not to me, not if it’s you” fame) and Electra (not really famous, but beloved in my heart). It all started when the original member of the Atreus house, Tantalus, decided that it would be a super great idea to feed one of his sons to the gods. He wanted to test their omniscience. The gods, naturally, didn’t really like this and threw Tantalus into Tartarus and resurrected his son Pelops (who was missing a shoulder because Demeter wasn’t paying attention).

This original sin, as it were, passed down through Pelops’ descendants, and they kept doing terrible deeds and getting punished for them. Essentially, don’t do cannibalism guys, it will make everyone including the gods hate you and your children ! And, in the TLT universe, when we think of cannibalism what do we think of? Well, Ianthe being freaky, but besides that: Lyctorhood. John says “Ten thousand years since I’ve eaten another person”; Gideon’s “All I ever wanted you to do is eat me.” Lyctorhood really is the purest form of cannibalism.

Generations down, this family just keeps murdering each other -- and it seems like the cycle will never stop. During the events of the Oresteia Agamemnon is murdered by Clytemnestra (because Agamemnon sacrificed their daughter Iphigenia to sail the Greek fleet to war against Troy), so Orestes murders her. And, because of this terrible matricide, Orestes is pursued by the Furies throughout the events of the Oresteia. He has to flee his homeland and eventually ends up in Athens.

And a name of one of the Furies relentless pursuing him? Not identified in the Oresteia, but later by Vergil: Alecto (side note: her name means endless rage, which is just so...)

So I was a little torn here, because these Furies’ constant pursuit of someone who committed the sin of the Atreus house (murder and/or cannibalism) reminds me a lot of the Resurrection Beasts and the “indelible sin” John talks about them sensing.

But then I’m reminded of a very good theory -- that Alecto is a resurrection beast -- that of Earth.

How on earth does Orestes get this to stop? And how might this play into the events of AtN?

Basically, Athena holds a trial! They all go to Athens and Orestes begs forgiveness (something none of his ancestors did) and Athena puts Orestes on the stand and has a jury decide his fate. Eventually, he is acquitted after a tie. And those furies -- are transformed in the Eumenides (the kindly ones) and are worshipped as goddesses, no longer creatures of revenge, instead protectors of justice.

Now, The Locked Tomb is really a series that revolved around forgiveness. The aggressive Catholicism really shines through in this matter. Does Gideon forgive Harrow for her years of abuse? Does Harrow deserve that? Will the original Lyctors forgive John for what he did to them? Is he sorry? Will Coronabeth ever forgive Ianthe for not choosing her to be her cavalier? Will Harrow ever forgive Gideon for sacrificing herself? Not all of these are on the same level, but it just goes to show how much the concept of forgiveness and whether it’s deserved adds a lot of tension.

Muir I think even said in an interview that in AtN, people will not be getting their comeuppance. I think that aligns with the themes of the Oresteia and the fact that this cycle has to get broken through forgiveness, otherwise it will continue into perpetuity. I think a lot of us saw that interview and figured it was talking about Ianthe just being awful and never getting punished by the narrative for it, but I think there’s a pretty solid chance that it’s going to be about God.

We might have all our characters repent for their crimes, and be found not guilty.

And Alecto, an alleged monster we all love for her monstrosity, might just be transformed.

#the locked tomb meta#tlt#gideon the ninth spoilers#harrow the ninth spoilers#the locked tomb spoilers#gtn spoilers#htn spoilers#tlt spoilers#tlt meta#alecto the ninth#atn#atn theories#alecto the ninth theories#atn predictions#did this instead of my physics hw due tomorrow morning#and very much needs to be done#oh well#the locked tomb

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

In this story, Clytemnestra learns of her husband’s plan.

She sees the altar and knows it’s not for marriage. She breaks free, saves her daughter, steals the dagger. She screams “the gods want a sacrifice? I’ll give them one!” as she slices Agamemnon’s throat open. The wind ruffles her hair as his blood, and not the blood of Iphigenia, soaks into the ground.

She doesn’t care what happens next, as long as her daughter is safe.

The Greeks don’t care, as long as the wind is at their backs and they can sail for war.

Instead, Agamemnon lives. He kills and steals and takes women as war prizes. Clytemnestra looks out the window of her murdered daughter’s bedroom to the sea and rages any time a breeze picks up. She is all rage, these days, all rage and revenge and regret. She knows time doesn’t soothe wounds like hers.

So she waits, hones her grief like a weapon, and swears to the gods she will have her retribution.

The Greater Grief; Clytemnestra

#greek mythology#clytemnestra#agamemnon#iphigenia#poetry#the iliad#words#mywords#ibuzoo#primordialnyx#reposting for better format

679 notes

·

View notes

Note

If I may contribute to your statement about how much Agamemnon deserved death, it wasn’t just his daughters wedding day. He arranged for her to be married to Achilles so that she would be within convenient murder range. If I remember correctly, at least in Euripides’ telling of the events, even Achilles thought the whole thing was awful when he realized what was going on. So yeah, there is no telling of the story in which I feel bad for him.

oh yeah, you’re absolutely correct that Agamemnon totally set that up and arranged for her to be married solely to get her out of the house to be killed

and Achilles WAS like “hey what the fuck this is my wedding too--well. not anymore I guess >:/”

ALSO Agamemnon is the bitch who started the Biggest Dick Slap Fight with Achilles about the distribution of loot, which led to Achilles having his Big Sulk and refusing to fight, so Patroculus put on his armor and fought in his place--shout to him by the way!! he has the highest kill count in The Iliad, NOT Big Baby Achilles--and was therefore eventually killed by Hector

so the order of fuck ups is:

Agamemnon makes a stupid ass promise (to Artemis I believe) at the beginning of the war to sacrifice whatever he sees first when he arrives home

immediately sees his daughter, who ran out to welcome him first bc she loves him

realizes now he has to kill her otherwise the gods will be mad and he won’t be able to join / or will doom The War expedition

doesn’t just stay home!! like yeah, he made a regular human promise ala WWI alliances where if something happens to this other guy over here, then fucking everybody in their dog has to go to war over it, including him, but this is YOUR DAUGHTER my dude, just stay home

Decides to go ahead and kill his daughter, I guess!!

lies to his wife (Clytemnestra) and to Achilles (ally) that he’ll marry Daughter to Achilles before they go off to war

when Clytemnestra brings Daughter down to get married, he instead ties her to the alter / pyre and kills her while Achilles is like “whoaaa what the fuck”

all so he can go to this stupid war that again, Does Not Involve Him. he only promised that if Other Guy’s shit got fucked up (ie, his wife Helen getting abducted), then he’d help out but like,, Helen maybe wanted to go to Troy anyway and also still ultimately not his problem

yes breaking promises his a huge No-No but also so is literally all of these other fuck ups he does, so why not just do One (1) fuck up and also NOT kill your daughter\

Goes to war and tries his hardest to fuck THAT up too!!

so the whole point of killing his daughter is that he HAS to go help fight in this war and then when he gets there, he’s useless

coulda just stayed home, moron

he starts a Biggest Dick Slap Fight with Achilles--ACHILLES--over who gets the best loot by pulling that he technically has rank as a king or something but he didn’t do shit

Achilles Big Mad

so basically this guy made direct eye contact with the Greeks’ BESTEST most special warrior, lied to him, killed his would-be wife, snidely pulled rank, took away another woman he wanted (that’s the “loot”), and pretty much fucked her while loudly reminding The Best Warrior he ain’t shit

like,,, ?? the Greeks DID NOT need him there!!

Achilles--their best warrior--refuses to fight, Patroculus fights instead, gets killed, Achilles mourns for three days, they basically come This Fucking Close to losing the war--which has already stalled for ten years btw bc they can’t actually get inside Troy, so the “war” thus far is basically just glorified yelling “meet me in the fucking parking lot you bitch” and sometimes someone from Troy would in fact come out to fist fight someone in the parking lot, aka Hector vs Patroculus (RIP)

if Achilles hadn’t been sulking, maybe he would’ve won the fist fight vs Hector, and Troy would’ve surrendered after losing their leader

but that doesn’t happen so Odysseus does the horse thing to get the soldiers inside Troy and they sack it, but the point is that Agamemnon DIDN’T DO SHIT except make things worse

Comes back home and immediately insults the gods

Clytemnestra does kind of set him up for this by asking leading questions, but they’re so Babey Basic. like,, if a woman asks “hey do you think you’re better than the gods” just say no!!

there’s a red carpet, which is a huge honor for the gods alone, and it’s Super Super Obvious Clytemnestra is goading him into hubris but Agamemnon “Can’t Think Critically” the Daughter Killer is like “oh fuck yeah I’ll accept honors only reserved for the gods because I’m just as good as them DO YOU HEAR THAT GODS I, A MORTAL, AM LOUDLY PROCLAIMING HUBRIS WHILE SYMBOLICALLY STEPPING ON YOU GEE HOW COULD THIS GO WRONG”

didn’t seem to put any thought into how Clytemnestra, a woman, was supposed to hold onto the throne for him FOR TEN FUCKING YEARS but then when he comes back, he rolls up like “hey, honey what’s up with you? me?? oh yeah, I had fun killing our daughter, going to war, fucking other women. LOTS of other women, I even fucked Achilles’s woman. yeah, yeah, that’s just the kind of leader I am Babey!! but anyway, you’re going to give the throne back to me and let me start making decisions as king for the whole country after I killed your daughter, nearly cost us the war, and loudly insulted the gods, right? Right??”

Guess who just got MURDERED

yeah it’s the asshole who deserved it. like, the Agamemnon specifically makes sure to recount how he killed his daughter as she begged for her life and then flashes forward back to the present where he insults the gods, just to make sure we know he Really Really deserves it

not even by modern standards! the audience was at least supposed to understand the promise he made to Artemis was dumb and shitty, that regardless of whether he was “”forced to do it”” he did still kill his own child, AND he committed hubris

Clytemnestra even has a monologue about what the fuck else she’s supposed to do: there are no laws she can turn to, and as a woman, she’s not allowed to get revenge, so her only other option is to just hand the kingdom back over to this Moron and keep sucking his cock or whatever while pretending he didn’t murder her child

basically, if someone kills one of your family members, you are morally obligated to kill them

Agamemnon MUST get his shit wrecked due to hubris

Orestes (their son) has been off dicking around and sulking, and he doesn’t want to kill Agamemnon, and anyway, all he did was kill his sister! does that really count?? seriously though, does it? spoiler: the ultimate answer is No, killing women does not count as killing a person bc women are not people

this message brought to you by Athena (ironically)

also some shit about how women aren’t actually involved in motherhood or creating a child, so a mother isn’t really a parent, and that’s why Orestes gets to kill Clytemnestra via The Greek Obligation For Revenge

Clytemnestra decides Fuck That

she holds Agamemnon accountable and kills him as he must be killed in order to avenge the killing of their daughter

she tosses a net on him while he’s in the bathtub and stabs him a million times with a spear, while laughing maniacally and bathing in the rain of blood that spurts out

as is her parental RIGHT for avenging her daughter

except the problem is that she’s Not A Man, so she ““isn’t allowed”“ to kill a man

and also that the reason Agamemnon deserved to die is ultimately decided to be his hubris, because Women Are Not People so it was OK or whatever for him to kill his daughter bc that didn’t count

therefore Clytemnestra double wasn’t allowed to kill him / avenge her and should have sat around waiting for the gods to kill Agamemnon I guess, but there’s no indication any of them actually planned to do that

they just used her to do their dirty work, so if anyone in this story was fucked into a corner by the gods, it’s Clytemnestra, not Agamemnon

Orestes then has a big long story about killing Clytemnestra

like fuck his sister I guess?? he wasn’t doing shit about revenge and his moral duty to kill the killer of his family when she was sacrificed but now that his shit idiot dad got himself killed, nooow he’s all about His Moral Duty

so he kills his mom

and he’s kind of sad about it and worried that now he deserves to die too because he killed his mom, and it’s a super fucked up sin in Greek World to kill your parent

hence the deus ex machina--literally, how this trope got invented

they lowered an actor playing Athena from the rafters and had her proclaim that Women Aren’t People, so it was probably OK or whatever for Agamemnon to kill his daughter and since women have nothing to do with the creation of a child, and just hold that little sperm-baby inside them like a cup until it magically comes out with zero effort or risk to them, then Women Aren’t Parents so Orestes didn’t reeeally kill his parent

#greek mythology#ancient greek#ancient greek mythology#the agamemnon#clytemnestra#ask#anon#answered#mine

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Riddle of the Sphinx as a Greek Tragedy

Warning – this essay includes spoilers (under the read more link)

It may be set in modern day Cambridge but in its referring to the story of the Sphinx of Thebes (and Oedipus) and its plot involving multiple revelations and betrayals, its exploration of revenge it deliberately calls back to the golden age of Greek tragedy, This is a point Steve Pemberton and Reece Shearsmith have commented on in interview, particularly to explain the episode.

As mentioned, the main story from Greek mythology that the episode references is Oedipus, specifically his banishing the Sphinx from Thebes by answering her riddle. However, it also references elements from Sophocles play ‘Oedipus Tyrannus/Rex’ and other Greek tragedies both in plot elements and how the narrative unfolds.

Firstly it is important to note that there are some major differences between this episode and Greek tragedies. For example there is no chorus commenting on the action and we see all the major action happen in front of us rather than key events happening off stage which then are relayed by a messenger, amongst other things (However it could be argued the crossword itself acts as a Greek chorus commenting on the action and as the messenger as it will tell others what has transpired between Squires and 'Nina')

However, there are a great number of ways in which this episode very accurately reproduces the practices of ancient Greek drama.

In Greek tragedy we usually see dialogues between two characters (Sophocles introduced a third actor, but we usually only see two characters interact in his and Euripides plays). We only see dialogue between Squires and Nina/Charlotte then Squires and Tyler. There are often long passages of exposition and monologues which are also echoed in this episode with Nina, Squires and Tyler all getting opportunities to explain what is happening.

The Riddle of the Sphinx (like many episodes of Inside No.9) conforms to the three Aristotelian unities for drama set out in in The Poetics. It has unity of action (it concerns Squires confrontation with Nina/Charlotte and Tyler with no subplots), unity of time (it occurs in real time over a half hour) and unity of place (Squire’s office). Indeed, almost two third of the episodes of Inside No.9 in the first four series also conform to these three unities.

The plot could be said to conform to three-episode structure of Greek tragedy with Squires and Nina/Charlotte’s initial interactions about crosswords being the first episode, Nina/Charlotte revealing her true motives being the second episode and Tyler’s arrival being the third episode. The Poetics also set out that a discovery should occur within a play and this certainly happens in The Riddle of the Sphinx!

The referencing of the myth of Oedipus in the story must be deliberate with Squires involvement with the death of his two children and sexual assault on a young woman who turns out to be his daughter echoing Oedipus unknowingly killing his father Laius and marrying his mother Jocasta.

Squire’s real crime like most characters in Greek tragedy is his ‘Hubris’ (ὑβρῐ́ς). This goes beyond our concept of pride or arrogance (both of which Squires is more than guilty of). In Greek Tragedy it is almost a form of blasphemy (certainly in the plays of Sophocles and Aeschylus) in that it is a form of disrespect for the gods and fate. Oedipus may be infamous for (unknowingly) killing his father Laius and marrying his mother Jocasta. But in Greek myth, this is not his actual crime. His and his parents were informed separately by oracles that Oedipus is fated to kill his father and marry his mother. They both take action to try and avoid this, but these actions only ensure that they occur. More pertinently it is flaws in all three’s personalities that allow these events to pass. All three act rashly or impulsively when told about the prophecy (Laius and Jocasta command baby Oedipus to be left to die, Oedipus runs away from his adopted parents). In spite of the prophecy Oedipus and Laius get into a violent argument when they encounter each other which leads to Laius’s death. So both had tempers that leads them to have violent arguments with apparently random strangers they encounter. Jocasta marries Oedipus almost immediately when he arrives in Thebes as a hero for having vanquished the sphinx even though she has only recently been widowed and he is quite literally young enough to be her son (despite the prophecy).

The plot of Sophocles’ ‘Oedipus Tyrannus/Oedipus Rex ‘occurs years into Oedipus’ rule of Thebes and concerns the eventual revelation of his actions. Throughout the play Oedipus behaves in high handed and arrogant manner toward all those around him, such as the sear Tiresias, in investigating the cause of the plague that has befallen Thebes and the circumstances of the death of Laius. He refuses to heed warnings of what he might uncover or that he may himself be the cause of the plague. This exacerbates his horror when his actions are eventually revealed. Jocasta kills herself offstage (hanging herself – with her scarf, rather like Simon had done) and Oedipus blinds himself.

It could be argued that Squires has his fate foretold him in Tyler apparently warning him that Nina/Charlotte plans to kill him. In trying to avoid this fate and not exploring why Nina/Charlotte wants him dead or Tyler’s motivation for telling him, he ensures his eventual death and that of his daughter.

Squires thinks he can outwit ‘Nina’ and that he will not be called to account for his behaviour toward others who have less power than him (Simon in the crossword quiz, the other young female undergraduates he presumably sexually assaulted). He refuses to show sympathy for those who have suffered because of his arrogance. In the end one of his victims, Tyler, will call him to account in the most horrendous manner possible.

Jacob Tyler in many ways acts in the role of the avenging god that we see frequently appear at Euripides’ tragedies (such as Dionysus in the Bacchae). These gods often reveal at the end of Euripides plays to the central figure the full consequences of their action and punish them accordingly. Tyler’s actions bring around the downfall of Squires and he exposes Squires hubris in his treatment of others. He could also be said to act as a Deus Ex Machina (a trope especially associated with Euripides) in supplying Squires with the bullet to kill himself with. However, these figures are frequently shown to be petulant and deeply cruel in Euripides’ dramas (particularly in plays such as The Bacchae and Hippolytus). Tyler is shown to be similarly cruel and petulant with no compassion toward Squires or even Nina/Charlotte who he raised as his daughter.

Jacob’s first name may be an allusion to Jacobean tragedy. Many Jacobean tragedies (also known as revenge dramas) were every bit as bloody and revenge driven as many Greek tragedies and undoubtably this was another influence on Pemberton and Shearsmith.

Professor Squires middle name Hector (revealed only at the end of the episode) may be another allusion to Greek myth. In the Iliad Hector was the Trojan warrior who kills Achilles’ companion Patroclus in battle. This evokes the wrath of Achilles (the stated theme of the Iliad) who in turn kills Hector.

One of the main themes of the Iliad and many Greek tragedies is ‘honour’ and its maintenance. Characters such a Medea are shown to go to extreme lengths when they perceive themselves as being dishonoured. Squires is determined to maintain his honour as a Crossword specialist over a young man even if it means cheating and abusing his position of power. Tyler feels he has lost his honour both by Squires cuckolding him and his resulting withdrawal from his promising academic career. Both men have an unhealthy preoccupation with their standing in the eyes of others and with being successful. Honour and excelling is linked to identity and power in Greek myth and is seen as almost conferring a form of immortality. The maintenance of honour becomes a deadly matter. Tyler can only see one way of restoring his lost honour- by avenging himself upon Squires and robbing him of his honour by exposing him to shame.

Nina/Charlotte has some interesting comparisons with two figures from Greek tragedy in Electra and Antigone. Electra and her brother Orestes’s killing of their mother Clytemnestra and stepfather Aegisthus in revenge for the murder of their father Agamemnon was the theme of plays by both Euripides and Sophocles (and the Oresteia). In Euripides’ play Electra’s desire for vengeance is met but she is then beset by guilt and regret. It is also worth notig that at least in Euripides plays Clytemnestra's killing of Agamemnon was in large part motivated by his apparent sacrifice of their daughter Iphigenia)

But Nina/Charlotte also has some parallels with Antigone, Oedipus’s daughter (who is herself the subject of a play by Sophocles). Antigone ensures her brother Polynices is given a proper burial after her uncle Creon expressly forbids anyone doing this. She is caught and punished by being entombed alive. Like Antigone, Nina/Charlotte is concerned with doing what she perceives as right by her dead brother. Her fate of being left completely paralysed while dying a slow death could be said to echo Antigone’s fate.

Alexandra Roach gives a powerful performance as Nina/Charlotte showing her fierce determination to avenge her brother and later her horror as the extent of Tyler’s betrayal become evident (all the more so as the character is completely paralysed – but her eyes speak volumes). She has been betrayed by both her ‘fathers’ (particularly Tyler) and her life has been lost as collateral in their power game. This echoes both Electra and Antigone having little power as women in their stories, a reflection of the highly patriarchal nature of ancient Athenian society.

There was always a clear moral purpose to Catharsis for the of any Greek tragedy. These were collective experiences whih deliberately explored religious and moral questions for the audience. To this end each play needed an act of ‘Catharsis’ (fear and pity) which Aristotle wrote was so critical to a successful drama. We get this act of catharsis. Squires is confronted with his role in the death of his two children (and the fact he assaulted his own daughter). Steve Pemberton manages to make Squires a pitiable character in the final moments of the episode. We see Squires is genuinely distraught at what he has done to Nina/Charlotte as he cradles her in her final moments. We pity Squires as a man who inadvertently destroyed the family he could have had if he had been more honest, less arrogant and less lecherous. We are also left with feelings of fear that people like Tyler are so ruthless in their quest for revenge and that our own misdeeds. The gunshot at the end resolves the action and ironically both Squires and the audience are released from the tension of the events of the episode.

The Riddle of the Sphinx may at first be nasty fun but as with much of Inside No.9 there is a moral message. Both Squires and Tyler behave in a toxic and entitled way which no one in the audience is supposed to admire. Squires may be physically destroyed by the end of the episode but Tyler is destroyed morally. Nina/Charlotte is so warped by a desire for revenge she is consumed (quite literally!) by it. All this in a story apparently about crosswords

#inside no.9#Reece Shearsmith#Steve pemberton#Alexandra Roach#Riddle of the sphinx#Oedipus#Euripides#sophocles

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think Clytemnestra was justified in killing Agamemnon?

I’ve been asked this a few times and I feel like it’s a difficult question to answer, to say the least. There are a lot of ways you could, such as:1) It’s irrelevant to try and answer because it’s not the point of this series of stories. We’re shown how eye for an eye justice completely FAILS in this house (Atreus gets revenge on Thyestes, Thyestes gets revenge on Atreus, Aegisthus gets revenge on Agamemnon, Orestes gets revenge on Aegisthus, Orestes is doomed to be Goddamn Miserable– there is never a ‘good end’ after anyone’s revenge) and though Clytemnestra’s intention may have been to end this very cycle of violence that plagues this house through killing Agamemnon, that obviously didn’t work. So from an overall plot/moral of the story standpoint, no? I guess? 2) If not in a overall story sense, is it justified to the reader at least? Dunno, depends how you look at it. Do you take stock in Euripides’ whackass, nonsensical canon (mentioned nowhere else ever) that Agamemnon violently killed Clytemnestra’s first family? Then I guess okay, you can say he had it coming. Given that he had absolutely zero reason to do that, and babies were involved, not sure what reader would miss the scum (see: why there’s no mixed feelings about King ‘I made my nephews into a soup for my bro just for the drama of it all’ Atreus’ murder)However, if we disregard that left-field one liner (as every other text does when talking about Clytemnestra’s reason), then there’s just the murder of Iphigenia to focus on. So then how does the reader interpret Agamemnon’s actions in IoA? Some people seem to come away thinking he just threw her on the altar, cut her throat and was merrily off to Troy on the same day without so much as a second thought spared (These people can not read. Some of them are even published authors. I am deeply sad.) Other readers have said: “I don’t care that he was Conflicted and Sad, he could have just like, Walked Away, you know,” which, as I’ve said in other posts, is a fallacy (there’s plenty of essays to be found on jstor on the subject). If either of these interpretations were correct, then again, I guess? you could feel his murder was justified. Yet I don’t think they are, so…. I won’t get into details here since I’ve written about it before, but his choices were more likely: (kill daughter) or (have an angry mob kill daughter and harm rest of family) or (have an angry god do both A and B and possibly smite the rest of the army as well by association). There never was a Walk Away And Everything’s All Right option. At least, not that his character would have good reason to believe. IoA is a tragedy not because it’s sad that an innocent girl dies to an Evil Man, but because of the utter hopelessness of the situation from all angles. I’ve seen some people who say that Artemis would have just let Agamemnon off the hook if he refused, and it was just a Test all along, but uh, have you read any stories with Artemis/Apollo? Very vindictive gods. The sacrifice was not just to appeal to her for favorable winds, but to apologize for unknowingly killing her sacred deer. He was already locked in to owing her repayment. Can’t just skip out on that. For more on why not to piss off this particular pair, and the bad results which follow if you think their commands can just be ignored, refer to: book 1, the iliadAnyway, getting back to the point, if Agamemnon did in fact have no better choice, if his hand was forced, and the whole catalyst for Clytemnestra’s decision is based on this, does it seem morally justified? I really don’t know. Does she have every reason to hate him all the same, sure. As a mother consumed by her grief, can we understand why she does what she does? Yes! Does his character deserve to get a free pass after the fact that it was likely his own greed in the first place that set off this series of events? Absolutely not. But I’ve never read his death as being 100% Deserved And Justified, open and shut case, either, for the reason stated above. Final verdict: It’s Complicated.3) Is the reader given indication that it was Justified after the fact? The stories of Electra and Orestes are always what throw me off especially when it comes to how we’re ‘meant’ to interpret Agamemnon’s death. Their lives end up essentially ruined after their father dies, they end up emotionally abused and neglected by the mother. Conversely, both of them are also shown to be unreasonably extreme in some points in their stories, but this also seems author dependent, and, at least for me, never pushes their characters so far to outright be interpreted as The Bad Guys (aight, except for the end of Euripides’ Orestes where Ore just goes absolutely apeshit and decides to commit arson, kidnapping and murder all at once, but…like..Euripides, man. We’ve been over this.) It always has struck an odd chord with me that the character whose whole motive is to avenge her daughter, treats her remaining children so poorly, which leaves me unable to read her as the unproblematic Justified heroine that some others do (spoilers: nearly everyone in this family is heavily flawed, and yet I would still like all of them to live). My point is, I feel like if we, the readers, were supposed to feel Clytemnestra’s choice had been the “right” one, we would either be shown a brighter future after Agamemnon’s death, or at least, Electra and Orestes’ stories likely wouldn’t cast them as such sympathetic characters opposite hers. That isn’t to say these things convey it was the ‘wrong’ choice either, necessarily, but rather that is ambiguous and pinning one of those black and white terms on it is impossible.Having said all that, I want to conclude that this is all obviously based on my own opinion alongside that I’ve put a lot of hours into researching the ins and outs of this particular series of stories. I’m not claiming I’m giving the one correct answer here. Literature can be interpreted many ways, colored by our own preferences and opinions. But I was asked for my own personal take, so there you go :^)

#thanks for sending me possibly the most loaded question you could ask on the blue hellsite#in conclusion: knife cat.jpg#one day ducky will post his good end oresteia fic and the light will be seen by all#i forgot some points here i'm sure... there's just so many#for anyone who's interested in the extended cut#send me your address so I can visit you and explain to you my passions#addictivechaos

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading Wednesday

Bears in the Streets: Three Journeys Across a Changing Russia by Lisa Dickey. A sort-of travel book by an American woman who speaks Russian. In 1995 she spent several months traveling across Russia as part of one of the very first real-time updating travel blogs; she did the same journey in 2005, then for the Washington Post; and now she's done it again in 2015, this time as the basis for this book. Each time she meets the same people (well, mostly: some have died, moved away, or simply don't want to talk to her again) and tries to assess how their lives have changed over the last ten or twenty years. I call it a "sort-of" travel book because it's not meant to be a guide for tourists or to convey the physical experience of her journey. Rather it's an attempt to explain the culture and people of Russia to her audience of Westerners, since they believe – as least according to several of her encounters – that Russia is full of "bears in the streets".

Dickey visits a wide variety of people: lighthouse keepers in Vladivostok, a rabbi in Birobidzhan (capital of the Jewish Autonomous Region), farmers in Buryatia who trace their history back to Genghis Khan, scientists studying Lake Baikal, a gay man in Novosibirsk, an excessively wealthy family in Chelyabinsk near the Ural mountains, the mother of a soldier in Kazan, a rap star in Moscow, and a 98-year-old woman in St Petersburg, old enough to remember the last tsar, among others. The selection is a bit random, but they all end up having interesting stories or perspectives, and Dickey's writing is warm, funny, and friendly. A recurring theme is Dickey worrying about telling these off-and-on friends of hers about her life: back in America, she's married to another woman. However, each time she ends up coming out, she finds acceptance and nonchalance.

My one critique of the book is that I wanted more about politics. Well, look at the news any day for the last year; of course I did. I know the American perspective, but I would have liked to hear something about the "average Russian" (as much as such a thing exists) view. But she actively avoids discussing anything remotely political; the few times someone else brings it up, she changes the topic as soon as possible. And I understand wanting to avoid fights! Whether out of fear because she's alone, respect because she's a guest, or just kindness because no one likes hurt feelings, it is completely relatable to focus on what you have in common instead of on disagreements. And yet I was just so curious and over and over again Dickey refuses to go there. Besides all of that, her trip was in 2015 – it's not her fault, but in some ways that already seems so outdated in terms of American/Russian politics.

Ah, well. It's still a very enjoyable book, if a bit shallower than I wanted it to be.

I read this as an ARC via NetGalley.

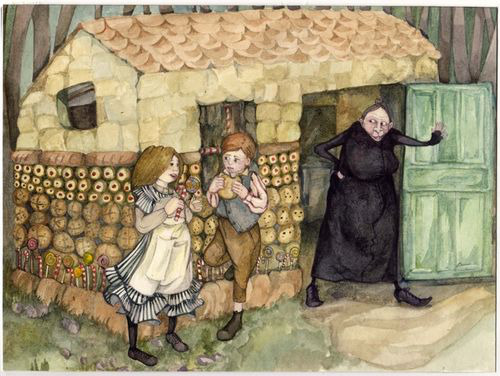

House of Names by Colm Toibin. A retelling of the Greek myth of the House of Atreus: Agamemnon, heading off to fight the Trojan War, sacrifices his daughter to gain the favor of the gods. His wife Clytemnestra is understandably not happy about this, and upon Agamemnon's (eventual) return home, she murders him with the assistance of her new lover. However their other children, Orestes and Electra, decide to get revenge for their father, and Clytemnestra is murdered in her turn.

Toibin deviates little from this traditional plot; what value his retelling does have is supposedly in the language and psychological realism of the characters. Unfortunately neither worked for me. The writing is distancing, meandering, and flatly reactive. Orestes and Electra in particular are oddly passive; they spend most of the book having no idea of the politics or history around them, and their attempts to gain power or knowledge are halfhearted at best. Orestes explicitly prefers the life of an unknown farmer to that of the son of a king. Most of the actual action is kept offstage, and we're left with endless pages of characters remembering what happened, or planning for what will happen next, but never actually doing anything. It ends up feeling fanficcy – which is not a criticism I normally apply to retellings! But this really does read like a long series of cut scenes: we already know the plot, so here's some prettily written navel-gazing to fill the inbetweens. It's hard to imagine how anyone could take a story with such powerful themes of revenge and justice and guilt and familial entanglements and turn it into something boring and apathetic, but Toibin managed it. It's Greek myth with all the characters turned into phlegmatic Hamlets – not a great idea.

I love retellings, but they need to add something to the original: perhaps give it a new twist, or simply be a very well-done version of a favorite story. House of Names doesn't qualify. Your time would be better spent with any of the ancient Greek versions.

I read this as an ARC via NetGalley.

(Link to DW for easier commenting)

1 note

·

View note

Note

Berenice, Bianca, Elektra

(Finally getting around to this, woohoo!)

Full Name: Berenice. Gotta love the Greeks for keeping it simple. I have a vague idea that her name might have been something else at some point, but it’s always just “Berenice” or “Berenice of Alexandria” when I’m talking about her. (Funny story, though: The inspiration for her character came from my first Webkinz named Beatrice, so you could count that as an alternative name, I guess. Now read the rest of this entry with that knowledge. Go on, imagine a Webkinz doing all of this.)Gender and Sexuality: Female/Possibly straight (All her love interests have been men, but I also take a Sims approach to sexuality with my OCs so…)Pronouns:She/Her. Ethnicity/Species: About a quarter Persian, three quarters Macedonian. She’d probably be white passing by modern standards, but, considering the way things worked in her time, I’m not sold on her being considered fully “white” by ancient ones. Birthplace and Birthdate: Alexandria, sometime around 38 BCE. Guilty Pleasures: She’s a full blown Epicurean; she doesn’t have guilty pleasures. The closest thing I can think of is her affair with Bran, but that’s because (1) He’s a barbarian, (2) She was married at the time, and (3) He has *history* with her people, so it was more worry than guilt. She was perfectly happy to tap that; she just wasn’t sure about the fallout. Phobias: Deathly afraid of heights. Is also paranoid over assassination attempts, though, considering her track record, I’d say it’s not so much paranoia as taking the right precautionary procedures. What They Would Be Famous For: She’s one of the most influential, intelligent, and glamorous women of her time, and that makes her both famous and infamous. To her allies, she’s The High Queen and so is held onto this kind of pedestal as the daughter of a respected king who’s kept them from further civil wars since her accession and, later, as a symbol for their cultural continuity even after defeat, as well as a noted patron of the arts and natural philosophy. To her enemies, well… They put every single negative stereotype of women, particularly “Eastern women” onto her, making her into some oversexualized, decadent, vain sociopath who regularly twirls her mustache as she gleefully celebrates the downfall of civilization. (I lean more towards her being a little of both.) Either way, she’s an absolute icon as a ruler, for better or worse. What They Would Get Arrested For: Multiple counts of murder, including murder of at least one minor, treason, and, considering the time period, adultery. That one would actually probably be more likely to have serious consequences than the other two. OC You Ship Them With: Bran. I also lowkey ship her with Eleanor, and if Marcus weren’t so aggressively ace, I’d probably go with it. OC Most Likely To Murder Them: Well, Elektra and Theron certainly gave it their best try, with John Hawtrey and Emma continuing the grand tradition of father-daughter pairs trying to kill her. In the present, Diane is probably her biggest threat, but I don’t think she would really kill her because, on some level, she admires her too much and doesn’t see how much of a threat Berenice is even when she’s been stripped of most of her power. Favorite Movie/Book Genre: She loves tragedies with her favorite, naturally, being Agamemnon. (She’s particularly fond of the ending and might or might not have commissioned at least one writer to write fix-it fic for Clytemnestra’s fate.) I also like to think that, in the modern AU, she has a soft spot for the Sword and Sandal films, the more cringe inducing the better. Yes, including (especially?) “Alexander.” Least Favorite Movie/Book Cliche: Hates black and white morality, especially when it comes to female rulers and how they’re perceived. Like, she knows she’s a monster, she owns up to it, but she’s tired of insipidly sweet princesses triumphing over evil queens. Her take on power struggles like that is that, while they’re inevitable (she killed most of her father’s and her husband’s concubines and children to keep her own power,) they involve the princess transforming into the evil queen, not defeating her. “Virtue rewarded” narratives just don’t appeal. Talents and/or Powers: Very intelligent, witty, and manipulative. She can effortlessly go from one mode to another, adapting her mannerisms to each one. Like all of her people, she has an expanded lifespan, as well as the ability to switch between her animal form and her human one. (Though the animal form is little used by her considering it’s also very conspicuous.) Oh, and she knows, like nine languages. Why Someone Might Love Them: In a time when women aren’t expected to rule in their own rights, she managed to seize power. She has a policy of religious and cultural tolerance, appointing the best people for a given position instead of strictly keeping to Macedonian or even Hellenistic in general citizens. Despite her claims that she’s gone cold over the years, she still obviously has a spot spot for her old childhood companions, showing more of her true self in their presence than she does around almost anyone else. Why Someone Might Hate Them: She’s absolutely ruthless in the measures she takes to keep her power. She’s literally killed babies and betrayed the love of her life to the tender mercies of their enemies. Like, come on. If you’re not ready for that kind of darkness in a character, particularly one who, at least as of this moment, has had no serious repercussions (ie death) for it , that could be jarring. I do think she’s troubled by it in her own way, especially the latter one which completely broke her for a while, but, at the same time…the girl’s dark. I’ve tried to not tone down what royal women of this time did to survive, for better or worse. I’d understand hating her 100%. How They Change: The first half of her character arc (losing her father and brother, taking her revenge out on Theron for their murders, the civil wars that resulted from not having a clear line of succession, marrying her uncle to ensure that she wasn’t swept away by the power struggles, participating in the murder of her half-siblings, having to marry Theron’s nephew, saying goodbye to her childhood friend and protector, throwing Bran to the wolves, and then orchestrating the murders of her husband, his other wives and concubines, and his children by them) is about her essentially having to lose touch with her human connections in order to survive. The second half of it (saving her old childhood friend, helping Eleanor in her rebellion against her brother, devoting a considerable amount of time to Bran’s recovery even when she thinks that he’s never going to forgive her for it, offering Ada a place at her court so that Atria will be happy and then protecting her when her past comes to haunt her, deciding against taking power from Eleanor despite it potentially playing to her advantage) is showing a possible restoration of those connections and the possibility of changing how things are done. I don’t think she’ll ever get a full redemption, because I’m not sure there can be a full redemption for all she’s done, but she gets the closest thing to it that I can imagine. Why You Love Them: She’s basically my love letter to the great Hellenistic queens, specifically Olympias and Cleopatra VII, with traces of the others threading their way throughout her backstory and characterization. It’s an absolute thrill bringing the best and worst of that time to the fray and getting to write someone as complex as her from the beginning of her character development to the end. She’s the kind of female character I’ve always latched myself onto, the ones who have grand schemes and ambitions and who manipulate and scheme their way into fulfilling them (I’ll give you a hint: The first female character I can remember loving was Anck-su-Namun from “The Mummy,” the second was Cleopatra, the third was probably Morgan le Fay) and I finally have the chance to have her run free and do her own thing without having to tragically die at the end. She also makes such a fantastic foil to Eleanor, with Eleanor ultimately deciding not to go down the path Berenice went down despite being exposed to similar traumas, though I don’t think I ever want to see them set up in a traditional protagonist-antagonist way. I prefer the two of them bouncing off each other, one the older, more Machiavellian queen, the other the more humanistic queen, with both kind of drawing closer to each other by the end.

I just…really love Ber as a character, okay? She’s probably one of my all-time favorites.