#Anglo-Irish Treaty

Text

#OTD in 1922 – Michael Collins secretly authorised the formation of a specially paid unit of seventy IRA volunteers, known as the Belfast City Guard, to protect districts from loyalist attack.

In the north of Ireland there were continual breaches of the Truce by ‘unauthorised loyalist paramilitary forces’. The predominantly Protestant, Unionists government supported polices which discriminated against Catholics in which, along with violence against Catholics, led many to suggest the presence of an agenda by an Anglo-ascendancy to drive those of indigenous Irish descent out of the…

View On WordPress

#Anglo-Irish Treaty#Arthur Griffith#Belfast#Dublin#England#Footage of Michael Collins in Armagh#History of Ireland#IRA#IRB#Ireland#Irish Civil War#Liam Lynch#Mater Hospital#Michael Collins#National Army#Northern Ireland#Prime Minister#Sinn Fein#Sir James Craig#Winston Churchill

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think the anglo-irish treaty and the dail eireann debates afterwards would make the most hilarious reality tv show.

youre telling me you wouldnt want to watch everyone argue about literally every single part of the treaty but in like a more modern language? that sounds hilarious. barton and duffy would have absolutely called someone a stupid ass cunt during the argument about signing and it would be hilarious

#anglo-irish treaty#history stuff#lloyd george is being dramatic and collins looks directly into the camera and rolls his eyes dramatically#irish history

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode 53 – The Provisional Government and the Anti-Treaty Side

What should have been a cause for celebration – the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, ending 800 years of British dominance – was the final strike needed to shatter the Irish movement for liberation. Eamon DeValera, president of the Dail and leader of the Irish Republican movement, so incensed by the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, renounced his presidency and led a number of Dail members out in protest. Arthur Griffith was elected the new Dail President and seven days later, Michael Collins was named Chairman of the Provisional Government. Griffith and Collins, who spearheaded the efforts to negotiation the Anglo-Irish treaty, were now responsible for handling the transition from being a British colony to British dominion and prevent a civil war.

During the Dail debates, Collins described the Anglo-Irish Treaty as a “steppingstone” towards Irish independence. I would tweak that thought slightly by calling it a series of steppingstones, the first one being the creation of the Provisional Government of Ireland. What was the Provisional Government?

The Provisional Government was created by Article 17 of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. It was meant to be a temporary government to handle the transition from being purely a colonized nation to the Irish Free State. Once a constitution was passed, the Provisional Government would step down for the constitutionally sanctioned government of the Irish Free State. The Provisional Government would go through two different governments: the first government led by Collins lasted from January 14th until the June General Election, which elected the second government. This was led by William Cosgrave, Minister of Home Affairs, and ruled until the approval of the Irish Constitution on December 6th, 1922. Despite being created by the treaty, Britain did not actually confer any powers to the Provisional Government until April 1922. Additionally, the Provisional Government was supposed to be answerable to a House of the Parliament, but did not specify a specific parliament or even create one.

The first Provisional Government consisted of the following members:

Michael Collins: Chairman

Eamonn Duggan: Minister for Home Affairs

W. T. Cosgrave: Minister for Local Government

Kevin O’Higgins: Minister for Economic Affairs

Fionan Lynch: Minister for Education

Patrick Hogan: Minister for Agriculture

Joseph McGrath: Minister for Labour

J. J. Walsh: Postmaster-General

While Britain did not acknowledge the Dail as a legitimate form of government, Ireland was ruled by both the Provisional Government and the Dail. The Dail considered of a president, Arthur Griffith, and his own cabinet. The Provisional Government, technically, was not answerable to the Dail until a new election was called. This election would be held in June and took their oaths in September 1922. Still both sides worked closely together since many of their ministers served in both governments.

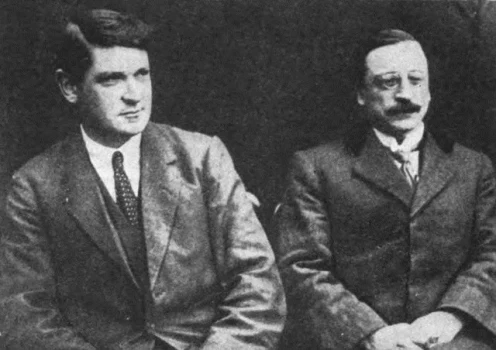

Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith

[Image Description: A picture of two white men in suits. The man on the left is leaning to the left. He is a white man with brown hair. He is wearing a white button down shirt and a black tie with small dots. he is wearing a dark grey vest and a light grey suit. The man on the right is sitting straight with his hand in his lap. He is white with brown hair, a thick brown mustache, and round, wire frame glasses. He is wearing a white, button down shirt, a light tie, and a dark suit with black lapels]

The dual government could create awkward situations such as when Richard Mulcahy, Minister of Defense in the Dail’s cabinet, had to “arrange” with the “Provisional Government to occupy for them all vacated military and police posts for the purpose of their maintenance and safeguarding”. While Mulcahy did not hold an official position within the Provisional Government, he attended many meetings to organize the country’s defense and deal with the schisming IRA. The British never understood this arrangement but were forced to accept it even though Churchill observed that it was “an anomaly unprecedented in the history of the British Empire” (Charles Townshend, The Republic, pg 386).

Florrie O’Donoghue, a Republican IRA member, described the dual government as a master-stroke by the pro-treaty side. The pro-treaty side used the continued existence of the Dail and Irish republicanism to distract people from the core dispute around the treaty all the while allowing the Provisional Government and National Army to strengthen its political and military power. He claimed that:

“if Dail Eireann had been extinguished by the vote on the Treaty the issue would have been much more clear-cut, and many of the subsequent efforts to maintain unity would have taken a different direction. Despite Republican hopes, time was on the side of the pro-treaty party” - Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green

P. S. O’Hegarty, however, felt that the provisional government was a disaster for the pro-treaty side, revealing a weak government eager to appease an intransigent opposition. Similarly, Griffith warned that a dual government would create chaos. What actually happened was that the Dail existed in name and basically merged with the Provisional Government by the time of the general election in June.

The National Army

The Provisional Government created the National Army on January 21st, 1922, even though legally it wouldn’t be formally recognized by the Irish Free State government until August 1923. The National Army structure was based on the British Army and it employed many men who had served In the British army to help with organization and discipline. However, it used the IRA ranks until January 1923, when they switched to a rank system that utilized by most armies. The National Army got most of its equipment, uniforms, and ammunition from the British Government. Once the treaty was signed the British government was invested in preserving the Provisional government. They even offered to send troops to help curb the civil war. About half of the National Army were half-trained troops thrown into counter-insurgency work. The army would have issues with discipline, human rights violations, and ill-discipline. Many in the National Army had combat experience, but little administration, training, and logistical experience. It wasn’t like the IRA could properly train or equipment their forces during the Irish War of Independence. However, core units, such as the Dublin Guard, proved themselves disciplined and effective military units.

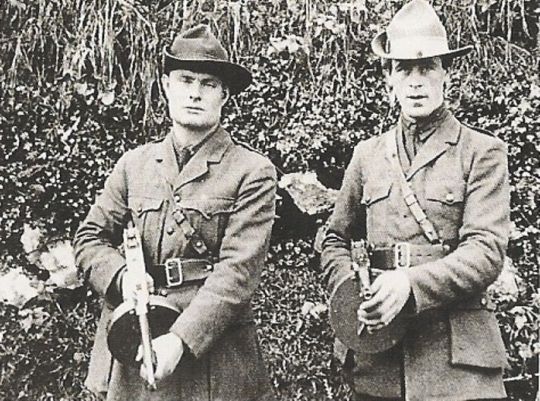

Fionan Lynch and National Army Soldiers

[Image Description: A black and white photo of a group of white soldiers in grey military tunics and pants. They are standing on loose dirt and there is an old fashion truck behind them]

The first core unit of the National Army was the Dublin Guards, who were a mixture of IRA veterans loyal to Collins (many who came from the Squad, Collins’ assassins) and ex-Royal Dublin Fusiliers who are known for their brutality in Co. Kerry. Their commander, Brigadier Paddy Daly, who once served as officer commanding of the Squad, said, “nobody had asked me to take kid gloves to Kerry, so I didn’t.” (Diarmaid Ferriter, Between Two Hells, pg 24).

As the army grew, it relied on men with British army experience such as General W. R. E. Murphy, Major-General Dalton while Lt-General J.J. O’Connell and Major-General John Proust served in the US Army during WWI, which would create problems for Richard Mulcahy and William Cosgrave during and after the civil war.

The Provisional Government knew they couldn’t rely on the army to keep civil order, so they created the Civic Guards to replace the withdrawn British Army and RICs. They played a small roll in the civil war itself except for a mutiny later in 1922, which we’ll talk about in another episode.

Finally, the British withdrew all forces except for 5000 men under General Macready, who was there, Churchill claimed because:

“We shall certainly not be able to withdraw our troops from their present positions until we know that the Irish people are going to stand by the Treaty, neither shall we be able to refrain from stating the consequences which would follow the setting up of a Republic." - Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green

The British either sensing that civil war was imminent or simply being racist and assuming the Irish “couldn’t rule themselves” constantly pestered the Provisional Government to do a better job at governing. While they acknowledged that to interfere in Irish affairs before the Irish Free State was created would only exasperate things, they had no problem threatening the Provisional Government with the return of British forces whenever they didn’t respond as quickly as the British expected.

The British had some right to be concerned as the National Army was weak. It’s estimated that about 70% of the IRA disapproved of the Treaty, while others supported it simply because Collins said to. This left Mulcahy with the difficult task of keeping together a republican army that didn’t respect or acknowledge the powers of the provisional government and felt the Dail was being co-opted. We’ll get into this more in the next episode, but by February 1922, the Provisional Government was facing the unsettling truth that the National Army was in a race with the IRA to claim ownership of the abandoned British barracks and large swaths of the country.

The Provisional Government gained its first victory on January 16th, just two days after it’s creation, when Michael Collins took the keys for Dublin Castle from the British. For centuries Dublin Castle as served as a citadel for British forces and one of the most distinct symbols of British colonial rule. The fact that it was now in Irish hands was maybe the first true sign that Ireland was free of British control. The Times described the moment as follows:

“All Dublin was agog with anticipation. From early morning a dense crowd collected outside the gloomy gates in Dame Street, though from the outside little can be seen of the Castle, and only a few privileged persons were permitted to enter its grim gates… [At half past 1] members of the Provisional Government went in a body to the Castle, where they were received by Lord FitzAlan, the Lord Lieutenant. Mr. Michael Collins produced a copy of the Treaty, on which the acceptance of its provisions by himself and his colleagues was endorsed. The existence and authority of the Provisional Government were then formally and officially acknowledged, and they were informed that the British Government would be immediately communicated with in order that the necessary steps might be taken for the transfer to the Provisional Government of the powers and machinery requisite for the discharge of its duties. The Lord Lieutenant congratulated … expressed the earnest hope that under their auspices the ideal of a happy, free, and prosperous Ireland would be attained… The proceedings were held in private, and lasted for 55 minutes, and at the conclusion the heads of the principal administrative departments were presented to the members of the Provisional Government.” - The Times, 17 January 1922 – Dublin Castle Handed Over, Irish Ministers in London Today, The King’s Message.

Later that day, Collins would issue the following telegram:

“The members of the Provisional Government of Ireland received the surrender of Dublin Castle at 1.45 p.m. today. It is now in the hands of the Irish nation. For the next few days the functions of the existing departments of the institution will be continued without in any way prejudicing future action. Members of the Provisional Government proceed to London immediately to meet the British Cabinet Committee to arrange for the various details of handing over. A statement will be issued by the Provisional Government tomorrow in regard to its intentions and policy." - Michael Collins, Chairman, The Times, 17 January 1922 – Dublin Castle Handed Over, Irish Ministers in London Today, The King’s Message.

As monumental as this victory was, it did little to ease the many issues facing the Provisional Government. They were responsible for

taking the executive from the British

maintaining public order during the transition

drafting a constitution

preparing a general election

preventing a civil war

Win over their furious, anti-treaty colleagues who refused to acknowledge the Provisional Government or the Dail as a legitimate government.

As much shit as the Provisional Government and later the Cosgrave Administration gets (and I will give because wow they make some terrible decisions), I think it can be easy to overlook what they were facing and how overwhelmed they must have been. Many of the members of the Provisional Government had either been violent rebels since 1916 or had been ministers in an illegal ministry risking arrest and death since 1916. They didn’t have any real government experience, they hadn’t dealt with any of their trauma, and the tools that had worked for them for the past few years are not necessarily the best tools when you’re trying to build a nation state.

Kevin O'Higgins

[Image Description: A black and white picture of a white man with a a receding hairline and a high forehead. He is wearing a white button down shirt, a thin tie, and a black suit coat. Behind him is an out of focus tan building and black metal gate.]

Another thing to keep in mind, because this will be an undercurrent to the entire war, is the relationship between the IRA and the IRB and the Dail. In season one, I spent a lot of time analyzing the tension between Cathal Brugha’s civilian ministry of defense and Mulcahy and Collin’s more militant Squad and IRA as well as the limited control GHQ actually had over its own units. This culture of might makes right and violence is ok if Collins says it is, is one of the reasons the civil war occurs and will plague Ireland for a long time. It was up to the Provisional Government to handle this problem, but how can the Provisional Government do that when it’s run by Michael Collins, a bit of a strong man himself who never had issues with assassins, disappearances, and violent solutions to irritating problems.

I find this quote from Kevin O’Higgins as capturing the feeling of the Provisional Government in 1922 both moving and enlightening: The Provisional Government was:

“simply eight young men in the City Hall standing amongst the ruins of one administration, with the foundations of another not yet laid and with wild men screaming through the keyhole” - Diarmund Ferriter, A Nation and Not a Rabble, pg 268

For the anti-treaty side, the acceptance of the treaty and the creation of the Provisional Government was nothing short of the very betrayal of everything they had fought for both in 1916 and during the Irish War of Independence. Worst, the anti-treaty side saw the Provisional Government co-opting the many institutions that were supposed to belong to the “Irish Republic” such as the Dail, Sinn Fein, and the Irish Republic Army. In an attempt to buy time to win over more people to the pro-treaty side and to work a compromise that would prevent civil war, Collins, during a Sinn Fein meeting, delayed the general election from February to June. On one hand, this could be seen as a pragmatic thing to do, especially if he feared he didn’t have the votes to uphold the treaty and he thought he could legitimately find a compromise that would satisfy everyone. However, many anti-treatyites saw this as election rigging. Mary MacSwiney ruefully wrote:

“When Collins saw he had a majority against him…he put up the unity plea to stave off the vote.” - Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green

Many blamed DeValera for agreeing to this compromise. Katheen O’Connell, DeValera’s secretary, wrote of the meeting were the compromise took place:

“The vast majority were Republicans. What a pity a decision wasn’t taken. We could start a new Republican Party clean. Delays are dangerous. Many may change before the Ard-Fheis meets again” - Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green

The thing was that no one wanted a civil war. Collins was desperate to prevent a military conflict and he believed that if he could craft a constitution before the next election, he could prove that the Treaty was only a steppingstone meant to placate the British. The constitution would be closer to a republican ideal. Similarly, DeValera, who even during the Irish War of Independence disliked guerilla warfare, wanted to avoid war. He believed he could use the next three months to win over the Provisional Government and tweak the treaty itself.

February 21, 1922 Sinn Fein meeting

[Image Description: A sepia toned photo of a gathering of mostly white men with a handfuil of white women. They are organized in three rows, the people in the front row are sitting, the people in the second and third row are standing. They are outside, in a park with bare branched trees.]

Sinn Fein fell apart shortly after the treaty was ratified and DeValera created his own party, Cumman na Poblachta. Despite wanting compromise, DeValera went on the offensive as he campaigned for the upcoming general election, claiming, on March 18th, 1922, that the IRA would have to “wade through Irish blood, the blood of the soldiers of the Irish Government, and, perhaps, the blood of some of the members of the Government” to achieve Irish freedom. (Charles Townshend, The Republic, pg 361)

The developing split wasn’t simply a matter of semantics or principles. This was a clear divide between those who were willing to work with what they managed to wrangle from the British and those who wanted to fight until all of their goals were achieved. These goals included complete separation from Britain, a return to a glorified Gaelic past, and an Irish republic, not a parliament that swore its loyalty to a British king. If the Provisional Government saw themselves as the protectors of Ireland’s future, the Anti-Treaty side saw themselves as the protectors of Ireland’s republican past. They draped themselves in the rhetoric and principles of Easter Rising, believed that the Dail under DeValera was the last legitimate government in Ireland, and that they alone had Ireland’s true interests as heart.

I want to save the in depth discussion about the IRA’s feelings for the next episode, where we talk about the taking of barracks and the army convention, but the army’s growing disgruntlement and anger with everything political, its disrespect for the Dail and GHQ, and its firm belief it “won” the war and thus had a right to determine Ireland’s future, also played a huge role in sparking the civil war. The Irish Civil War was both a legitimate political argument but also a huge army mutiny.

In his magnificent book, Vivid Faces, R. F. Foster explains the treaty split in class terms. He writes that one can see the Irish Civil War as a long brewing divide between those who were influenced by Catholic piety and social conservatism and pragmaticism against those who were ardently revolutionary and radical and socialist. Liam Mellows argued that:

“We do not seek to make this country a materially great country at the expense of its honour. We would rather have this country poor and indigent, we would rather have the people of Ireland eking out a poor existence on the soil, as long as they possessed their souls, their minds, their honour” - R. F Foster, Vivid Faces, pg 282

Liam Mellows

[Image Description: A black and white photos of a white man with curly blonde hair that is shaped upwards. He has a faint mustache. He is wearing a white, collared, button down shirt with a black tie and a black suit. The wall behind him is grey]

This sounds great on paper, but how do you sell that to a people who have been colonized, gone through a world war, and spent the last few years in a guerilla war? Ireland had been economically, physically, socially, and culturally brutalized during the Irish War for Independence and it makes sense that while some people would want to fight until everything they desired was achieved, others simply wanted a break and a chance to recover and heal. But even healing was a matter of contention because what did healing really mean when you still had to take an oath of loyalty to your colonizer? When your national army is being armed by your former oppressor so you can fire on the disgruntled members of your own society? When your island is split in two and the only way to unite it is still through violent intervention? When so many of the heady promises made during the revolutionary period are put aside for more practical concerns?

I would add that there is something that happens when people are presented with the opportunity to form a state. We saw this in our Season 2, Central Asia during the Russian Civil War. The minute the Jadids, Alash Orda, Soviets, and others were given the chance to form their own definition of their boundaries and identities, is the moment we see this idea of “us” vs “them” and the “other” form as well as the concept of elites who control political and economic power.The Treaty shifted the debate that was occurring in Ireland during the Irish War for Independence. No longer were the IRA fighting a guerrilla war that they could lose at any moment and they needed lofty ideals such as a Republic and a Free Gaelic Ireland. Or an Ireland cleansed of all British influence. The Treaty gave the people of Ireland a real tangible chance to build something and that changed a lot of desires, hopes, and plans for a lot of people.

Mary MacSwiney

[Image Description: A black and white picture of a white woman wearing a simple, black, long sleeved dress. Her wavy, brown hair is pulled back into a bun. Behind her is a grey wall]

The anti-treaty side were not wild people who wanted to destroy simply to destroy. The split tore them apart. Many simply couldn’t understand how their comrades could give up on their republican dreams so easily. Many anti-treatyites wrote to their pro-treaty friends, begging them to support the Republic. Mary MacSwiney, one of the most vehemently anti-treaty women, wrote to none other than Richard Mulcahy, claiming:

“No matter what good things are in the Treaty, are they worth all this unhappiness, Dick? Do you not realize we hold the Republic as a living faith – a spiritual reality stronger than any material benefits you can offer – cannot give it up. It is not we who have changed it is you.” - R. F. Foster, Vivid Faces, pg 280

Formerly close family members found themselves bitterest of enemies. For example, the Ryans family found themselves torn apart as Min, Mulcahy’s wife, along with Agnes and Denis McCullough supported the treaty, while their siblings Phyllis, Chris, Nell, and James and Mary Kate were against it. Some would spend time in jail and even go on hunger strike while Mulcahy was minister of defense. He would refuse to release them or give into their demands during the war. Phyllis at one point told Min to leave Mulcahy, but Min refused.

The treaty nearly ruined Mabel and Desmond Fitzgerald’s marriage and shattered friendships, the most famous being Michael Collins and Harry Boland. Others, like Liam Lynch, bent themselves into pretzels trying to find a way to avoid a split. Both sides appealed to the Catholic Church to support their side as they grew closer and closer to war.

Others couldn’t find it in themselves to blame their comrades and turned their anger on the British, Protestants, and the “other”. Muriel MacSwiney, wife to Terence, wrote to Mulcahy, stating:

“I don’t feel anything against anybody but England for what has happened…Although I think this treaty is by a long way the greatest infamy that the enemy has ever perpetrated on us & I will always oppose it or anything like it I feel nothing against any Irishman; the whole weight of my venom is directed against the English people…I shall spend my life not, as up to this, working for the complete independence of Ireland’s Republic, but also working for the destruction & downfall of England & of every single English person I come across. The English people are to me now a plague of moral lepers. - R. F. Foster, Vivid Faces, pg. 280

Finally, I would argue that trauma played a huge role in the split. You simply can’t take a majority of young men and women who have spent the last few years fighting to survive and tell them use this new political process to register your disagreements with this government that we’re building on the fly. The sense of betrayal – on both sides – was very real and very vivid and there wasn’t any mechanism to deal with it.

For the Provisional Government, they couldn’t believe their comrades were willing to risk their very state over something as “miniscule” as an oath. The hatred of the treaty and the government that would follow must have also felt quite personal since so many former members of DeValera’s government transferred to the Provisional Government. All of a sudden they weren’t trusted to lead Ireland into a liberated future.

For the anti-treaty, apparently everything they fought for was a lie and the comrades they thought they could trust were traitors to the very idea of an Irish Republic. Old, festering personal clashes rose to the surface with sudden ferocity, because the treaty released the pressure of war.

All these the differences and issues that had been developed during the Irish War of Independence could be ignored as long as survival was paramount. But now that the war was over, the pressure that kept all that shit down, was gone, and the world isn’t better. In fact, it looks like it’s either going to be more of the same or a compromised reality which doesn’t really justify all the shit you went through to get to this point.

It’s like when you’re working on your own trauma and you dive really deep and you accidentally ram into a deep, dark trauma and now it’s out and all these emotions your brain was protecting you from, rises to the surface and so now you’re a swirl tornado of emotions with no tools to handle it and nothing seems to help. The biggest tragedy is that both sides tried so hard to avoid war, but it wasn’t enough. The sense of betrayal was too strong and the promised achievements of the treaty were too minuscule.

References

The Republic by Charles Townshend

Between Two Hells by Diarmaid Ferriter

Vivid Faces by R. F. Foster

Irish Civil War 1922-23 by Peter Cottrell

Richard Mulcahy: From the Politics of War to the Politics of Peace, 1913-1924 by Padraig O Caoimh

Eamon De Valera: a Will to Power by Ronan Fanning

Green Against Green by Michael Hopkinson

#irish history#irish civil war#anglo-irish treaty#michael collins#richard mulcahy#eamon devalera#Kevin O'Higgins#W. T. Cosgrave#queer historian#queer podcaster#Spotify

0 notes

Text

Today in 1921, the Anglo Irish treaty was signed.

Effectively rubber stamping the partition of Ireland.

And some fuckers out there still think we deserved it!

Why don’t we split THEIR countries in half and see how they like it! (HYPOTHETICAL!)

And no I’m not lionising the anti-treaty faction.

Most of them were dogshit reactionaries what didn’t give a shit about the north either.

#dougie rambles#personal stuff#ireland#vent post#political crap#history#irish history#partition#fuck loyalism#politics#irish politics#irish civil war#Anglo Irish treaty

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not me making Ace Attorney fanart out of the Anglo-Irish Treaty Negotiations of 1921 (I have a test on Friday, this is how I memorise quotes)

860 notes

·

View notes

Text

the line "one hundred years from the empire now" is so powerful because it both highlights the progress we've made and the things that are still left to do. it's been 102yrs since the 1921 anglo-irish agreement, a treaty that should've given ireland independence, but the devastating effects of the fallouts from it (e.g the troubles and religious divide) are still being felt. one hundred years from when the fight for freedom started and another hundred years to go

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stances of IRA divisions on the Anglo-Irish treaty, which ended the Irish War of Independence.

by oglach:

For background, what made the treaty so controversial was the fact that it gave Ireland partial independence as a dominion (akin to Canada at the time), where politicians still had to swear loyalty to the crown. As well as effectively guaranteeing the partition of the island, and the creation of Northern Ireland.

Many within the IRA rejected these compromises and wanted to keep fighting for complete freedom, causing a civil war between pro-treaty and anti-factions. This was eventually won by the pro-treaty side with British support, with the pro-treaty IRA going on to become the new Irish military.

The anti-treaty faction was driven underground, but continued to wage a low-level insurgency against both Britain and the new Irish government until the 60s, when they split again into communist and nationalist factions. The latter of which became known as the Provisional IRA, and obviously experienced a huge "revival" during the Troubles.

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Thompson Submachine Gun and Irish Independence

In the final month of World War I a US Army officer named Brig. Gen. John T. Thompson began development of a submachine gun which he called the "trench broom". Spitting out 800 rounds a minute of .45 caliber lead the trench broom was to be used to clear World War I trenches of German soldiers, however the war ended before work on the Thompson could be finished. Development continued after the war until in April of 1921 production of the Model 1921 Thompson began.

Among the first buyers of the Thompson were secret agents of the Irish Republican Army who were looking to buy weapons for Irish forces fighting for independence against the British. At the time there were no laws in the US restricting the sale of fully automatic firearms and thus any civilian could buy one as long as the had the cash ($200 or around $3000 in today's money). Some of the earliest produced Thompsons were purchased, serial numbers 46, 50, and 51, and smuggled to Ireland. There they were tested in a soundproofed basement Dublin. IRA leader Michael Collins, who attended the test firing was like, bruh we need more of these! So a call went out to buy and ship as many Tommy guns as possible.

Most Thompsons were purchased by immigrant Irish fraternal groups and patriotic groups who organized fundraisers and pooled their money together to cover the steep cost of buying the submachine guns. In some cases they disappeared from government armories. An Irish immigrant who was sheriff of San Mateo, California donated two Thompsons for the cause. Many of the weapons as well as magazines and ammunition made their way to New York City, where 495 of them were loaded onto one ship. Unfortunately for the IRA local police and Federal authorities seized the weapons in a raid after a captain grew suspicious of the cargo that was being loaded onto his ship.

While 495 Thompsons were seized, another 158 were smuggled out of the US to Ireland by other means. Most only arrived in the final months of the Irish War for Independence as a truce was agreed upon on the 11th of July and the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed in December guaranteeing Irish independence. The Thompson did see plenty of action in the Irish Civil War of 1922-1923 when factions of the IRA began fighting among each other due to disagreements over the terms of the treaty. In 1925 the 495 Thompsons that were seized by the US Government were returned as there were no neutrality laws at the time and it was not illegal to send weapons to foreign powers overseas. Most of those Thompsons went into government armories without ever being fired in anger until they were decommissioned in the 1960's-1970's. Some remained in private hands, even being used by IRA fighters as late as the 1970's and 1980's

227 notes

·

View notes

Text

TIL that the first female Member of Parliament in the UK was Constance Markievicz who was a countess born into an upper class family of Protestant Anglo-Irish origin but she never actually sat at Westminster because Markievicz was elected as a member of Sinn Fein and a lifelong supporter of the Irish nationalist movement and supported the anti-Treaty side during the civil war. So like, if the UK doesn’t commemorate her as much as you’d think the first woman elected to parliament would be, I think that’s why

Also

In 1908, Markievicz became actively involved in nationalist politics in Ireland. She joined Sinn Féin and Inghinidhe na hÉireann ('Daughters of Ireland'), a revolutionary women's movement founded by the actress and activist Maud Gonne, muse of WB Yeats. Markievicz came directly to her first meeting from a function at Dublin Castle, the seat of British rule in Ireland, wearing a satin ball gown and a diamond tiara. Naturally, the members looked upon her with some hostility. This refreshing change from being ‘"kowtowed" to’ as a countess only made her more eager to join, she told her friend Helena Molony.

She seems cool

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, Flynn's lore dump time

The 4th generation of his family trade, Flynn James Luton was born in 1893 in Dublin, Ireland to Cathal Luton, a weaponsmith, and Martha Cassidy-Luton along with his younger brother, Thomas. He enjoyed a relatively quiet childhood with his father teaching him about the art of gunsmithing, hoping for him to follow in his forefather's footsteps. However, he was distant to Flynn otherwise due to the nature of his work. But his mother's death from pneumonia when he was 17 drove him into a deep depression and that led him to join the British Army in the hopes of getting a purpose in life. He would be trained as an armorer and ascend to the rank of Corporal before the outbreak of the Great War. He would then be transferred to the Royal Dublin Fusiliers regiment, 16th (Irish) Division, and be shipped to France.

He would be fortunate to survive the war, although he would not speak much about his experiences. The nature of the 16th Division, mostly comprised of Irish Volunteers, would mean that Flynn would begin having nationalistic thoughts and wishing for Irish independence in his time with the unit. During the Battle of Passchendaele, a German artillery shell landed near his position, the resulting shrapnel cutting off half of his jaw and taking away his nose, hospitalizing him for 3 months and requiring him to wear a prosthetic mask from there on. After the Armistice, Flynn would be discharged with the rank of Sergeant Major, disfigured, suffering from shellshock, and returned to an Ireland teetering on the brink of war. War did break out, the Irish War of Independence, and Flynn would fight in it on the side of the Volunteers, renamed the Irish Republican Army. With the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the war's end, Flynn is one of many who thought the treaty went against what they had fought for. But rather than fighting in the upcoming Irish Civil War, Flynn was just tired of war, and therefore in late 1921, he boarded a ship headed for America, determined to start again.

When he disembarked in Boston in January 1922, he initially wanted to settle down, but after a week's stay, he realized that the city wasn't for him. With little other choice, Flynn decided to take to the roads and wander through the Continental United States, trading his skills for a living, hoping to find a suitable place to settle down and to find himself and his purpose again. The journey would take him 3 years, going through 25 major cities and countless small towns from the East Coast to the Pacific Northwest. His drifting days would be filled with lessons, memories, experiences, and a few bodies, from a bar crawl in San Francisco, a duel leading to a carjacking in El Paso, an encounter with a death cult in rural Montana, and the most notable, a hit job in New Orleans that spiraled into a massive assault on a mansion compound, where he would first meet the siblings Nicodeme and Serafine Savoy. The assault by the three would be the start of a deep friendship that would continue to the present day.

Arriving at St. Louis in early 1925, the atmosphere convinced him that this was the place, and using the funds he had saved throughout the years, he bought a building in the city's downtown and founded Luton's Gunsmithing and Sporting Goods. In this gun store, he would sell both legal firearms, and later in his basement, illegal weapons. Through his customers, he heard of the main criminal organizations in the city, Lackadaisy and Marigold. His first time in the Lackadaisy Speakeasy doesn't go well, with a drunk patron mocking his appearance, eventually leading to a brawl. When the dusk settles, the patron is thrown out and Flynn is cared for by the staff, who introduces him to the proprietor, Atlas May. Atlas has known of Flynn since he opened his shop, and offers a partnership in which Flynn would become the gang's unofficial main armorer, while Atlas would use his contacts to connect Flynn to more products and customers. This partnership would continue after Atlas's death, although Flynn then decided to stay neutral in the rivalry between Lackadaisy and the new kingfish of the city, the Marigold gang. His reunion with the Savoys does come as a surprise, but a welcoming one nonetheless, with the siblings inviting him to their jobs, explaining the matter to their boss, Asa Sweet, as an old freelance partner. He has been offered to join the Marigold gang, a decision he still hasn’t fully made. Nevertheless, his business is still running smoothly, though, with the simmering situation in the city's underground, he's preparing himself for the next big thing that will be happening...

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in 1868 – Birth of Irish patriot and revolutionary, Countess Constance Markievicz, née Gore-Booth in London.

Countess Markievicz, born Constance Georgine Gore Booth, politician, revolutionary, tireless worker with the poor and dispossessed, was a remarkable woman. Born into great wealth and privilege, she lived at Lissadell House in Co Sligo. She is most famous for her leadership role in the 1916 Easter Rising and the subsequent revolutionary struggle for freedom in Ireland.

Born in 1868, Constance was…

View On WordPress

#1916 Easter Rising#Ailsbury Gaol#Anglo-Irish Treaty#anti-Treaty#Casimir#Casimir Dunin-Markievicz#Co. Sligo#Constance Markievicz#Countess#Dáil Eireann#Dublin#Dublin Lock Out#England#Fianna Fáil#Glasnevin Cemetery#Irish Citizen Army#ITGWU#James Connolly#Kilmainham Gaol#Liberty Hall#Lissadell#Maeve Allys#Michael Collins#née Gore-Booth#Sir Josslyn Gore Booth#Ukraine#W.B. Yeats#Westminster Parliament

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Video footage of the Irish delegates who signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty

#Dunno why it gets so sped up at the end#History#European history#Irish history#World history#Ireland#Irish War of Independence#Michael Collins#Arthur Griffith#Robert Barton#Eamon Duggan

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recap of the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The Anglo-Irish Treaty is a very controversial document that sparked the Irish Civil War. But how was it created and what did it actually do?

Truce

A truce between Britain and the IRA was declared on July 11th, 1921. According to the truce, the British agreed to:

Stop the raids and searches

Restrict military activity to support police during their normal duties

Remove the curfew restrictions

Suspend reinforcements from England

Replace the RIC with the Dublin Metropolitan Police

The IRA agreed to

Avoid provocative displays

Prohibit the use of arms

Cease military maneuvers

The IRA released a bulletin, announcing the truce which added additional terms. The British also agreed to:

No incoming troops or munitions

No military movements

No pursuit of Irish officers or men or war material

No secret agents spying

No pursuit of lines of communication

The IRA agreed to:

No attacks on crown forces and civilians

No provocative displays of forces

No interference with government or private property

No disturbing of the peace

Neither side was happy. The British claimed that waving the Sinn Fein flag was provocative and that they had to exert all discipline while the Irish didn’t have to. GHQ complained that according to the treaty the military couldn’t move freely in Ireland. After several disagreements, the British backed down and recalled its forces into their barracks. Meanwhile the IRA believed this was a temporary truce and continued to recruit, drill, and prepare for the resumption of war.

For DeValera, the preliminary negotiations were a chance to reassert himself as the leader of the Dail and Irish liberation.

Preliminary Negotiations

DeValera and an Irish delegation which comprised of Arthur Griffith, Austin Stack, Robert Barton, Count Plunkett, and Erskine Childers traveled to London on July 12th to begin preliminary discussions with Lloyd George. Dev would meet with Lloyd George 4 times between July 14th and the 21st. Lloyd George’s proposal was to turn Ireland into a Dominion but they would have no navy, no hostile tariffs, and no coercion of Ulster. Dev refused, saying that “Dominion status for Ireland would never be real. Ireland’s proximity to Britain would not allow it to develop as dominions thousands of miles away could.” Even though Dev rejected his proposal, Lloyd George continued to honor the truce and Dev returned to Dublin.

DeValera had a proposal of his own, known as Document No. 2 or External Associations, a point of controversy. This document proposed that Ireland would not be a Dominion but it would still have associations with England. When he explained it to Erskine Childers and Robert Brennan, he drew five circles inside a large circle. The large circle was England and the other circles were the Dominions it currently ruled. He then drew a circle outside of the big circle but connecting it and that was supposed to be Ireland. Unfortunately, he was either never able to properly explain his plan to his fellow Irishmen or the British cabinet or it was simply too much for people. Many of the diehard republicans found it baffling or a betrayal and the British couldn’t see how it was different from having an alliance with an independent state (and thus unacceptable). He formally shared this document with his cabinet on July 27th, but refused to share it with Lloyd George, fearing that it would be too revealing if sent to the British in its current form. It seems that Dev wanted to keep it as a compromise he might ultimately accept but wanted to see how far they could push the British before being forced to offer a compromise of their own. He sent a formal reply to Lloyd George rejecting Dominion status with a vague description of his external association plan. The British and Irish agreed to continue negotiations. A new team was to be created to represent Ireland. A team Dev refused to be a member of.

The Irish Delegation

The Irish cabinet met once more on September 9th to discuss who would go negotiate on Ireland’s behalf. This is maybe one of the most controversial moments in a rather controversial process and war. When the cabinet met that day, they were met by DeValera’s bombshell that he would not lead the Irish delegation. Additionally, he required that all of Britain’s offers be reviewed by the Dail before the Irish delegation made any agreements.

The second point of controversy was whether the goal of the negotiations was to walk away with a republic or if it was to walk away with any level of independence from Britain. Lloyd George had already made it clear that Britain would never accept a republic or full Irish independence. But where did the Irish stand?

For the entirety of the war, Dev’s title had been President of the Dail Eireann, and was changed to the President of the Irish Republic on August 26th. Was that a signal that the Republic was the goal or a formality? Members like Brugha and Mary MacSwiney were under the impression that either the British promised to recognize an Irish Republic or it was back to war. Yet, Michael Collins went on record saying that “the declaration of a Republic by the leaders of the rising was far in advance of national thought” and MacSwiney accosted Harry Boland and his and Dev’s perceived lack of commitment to a republic, and warned him to "please leave your Dual Monarchy nonsense behind you. Our oaths are to the Republic or nothing less.” Dev didn’t help at all by refusing to provide any sort of guidance to the delegation and it seems that, if Dev truly believed the republic or the External Association idea was ideal for Ireland, he never told the members of the delegation.

Finally, to make matters worse, Dev was sending the delegation as plenipotentiaries, who technically should have full powers to handle negotiations, but Dev crippled their powers by requiring that they refer back to the cabinet for major questions and with "the complete text of the draft treaty about to be signed". However, the British assumed they were normal plenipotentiaries and could not, as Viceory Lord FitzAlan told Lloyd George, “take advantage of De Valera’s absence to delay and refer back to him”

The cabinet protested Dev’s proposal strenuously, but Dev persisted and despite all this ambiguity and disbelief that Dev would not go to London, the cabinet approved the following appointments:

Arthur Griffith who would be Chairman

Michael Collins

Robert Barton, the minister of economic affairs

Eamonn Duggan, a lawyer and chief liaison officer for implementing the truce

George Gavan Duffy, another lawyer and Dail’s envoy to Rome

And Erskine Childers, Fionan Lynch, Diarmund O’Hegarty, and John Chartres as a secretaries.

DeValera dismissed Duggan and Duffy as mere legal padding, but hoped that Barton would be stubborn enough to limit the amount of compromises the Irish would have to make and trusted Childers to serve as a source of strength for Barton. Dev seems to have ignored the fact that Griffith despised Childers.

Their instructions were to negotiate and conclude a treaty of settlement, association, and accommodation between Ireland and the community of nations known as the British Commonwealth.

Treaty Negotiations

The Irish delegation arrived in London on October 8th (Collins would arrive on October 10th) and took residence at 22 Hans Place and 15 Cadogan Gardens in Kensington. The Irish representatives had accreditations that said they were negotiating on the behalf of an Irish Republic, but the British never asked to see them and Griffith never offered them, so Britain never knew it had indirectly recognized the Republic’s existence.

The first meeting took place on October 11th, at 10 Downing Street. The Irish were facing the likes of

David Lloyd George

Winston Churchill, Secretary of State for the Colonies

Lord Birkenhead, Lord Chancellor

Austen Chamberlain, Lord of the House of Commons

Sir Laming Worthington-Evans BT, Secretary of State for War

Sir Gordon Hewart, Attorney General

And Sir Hamar Greenwood, chief Secretary for Ireland

It cannot be denied the British team was more experienced and were better prepared than the Irish. They also had the benefit of being in agreement that a republic was out of the question and the goal was to get the Irish to agree to a Dominion status. They had a document all written up outlying their proposal whereas the Irish had Dev’s vague external association document and his unconnected thoughts about Ulster’s future. Yet despite their formidable reputation and skills, all were not cozy in the British delegation. For one thing, it was missing a very important player in British politics at the time: Bonar Law, the man who nearly pushed the Conservatives to civil war during the 1912 crisis and the man who would lead the Tory revolt against this very treaty that ended Lloyd George’s career. Lloyd George also had the extreme pressure from Ulster not to give an inch when it came to the Ulster exception.

David Lloyd George

[Image Description: A black and white photo of a blonde haired, white man with a thick mustache that takes over his entire lip. He is facing the camera. He is wearing a white button down shirt with a grey tie and and a grey suit]

The delegation would meet seven times between October 11th and 24th while also breaking out into three different committees: the Committee on Naval and Air Defense, the Committee on Financial Relations and the Committee on the Observance of the Truce, which consisted of members from both delegations. These committees would meet between October 12th to November 10th. After October 24th, the negotiations would be conducted through sub-conference, which met 24 times in various locations until the signing of the treaty on December 6th.

Because of the complex nature of the Irish-British relationship, a lot of time would be spent trying to figure out Irish fiscal autonomy. However, the two points that caused the most trouble between the negotiating parties was Ireland’s unity and allegiance to the Crown.

In regard to Ulster, Lloyd George had already promised the Unionists that Ulster would not be coerced and effectively recognized partition as the only solution. Lloyd George proposed creating an Ulster parliament and a boundary commission to determine the borders of the new states. Collins and Griffith hated the compromise because it was partition, but Lloyd George warned them that if they didn’t agree he would be forced to resign and they’d be facing Bonar Law, a British politician even more opposed to Irish interest than Lloyd George. They grudgingly agreed.

The nature of Ireland’s relations to the crown was a thornier problem since the Irish wanted complete legal sovereignty and the British demanded an oath of loyalty. For the British the oath represented a desperate symbol of control as they lost a part of their empire. For the Irish the oath was a literal vow of subjugation. Griffith and Collins were quick to understand that symbols meant nothing if Ireland could be guaranteed real power over her own destiny. He believed that the treaty was a stepping stone to further independence for Ireland. Put another way, what power would Britain truly have over Ireland if Ireland had an Irish government, Irish police force, Irish Army, and Irish courts?

Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith

[Image Description: A picture of two white men in suits. The man on the left is leaning to the left. He is a white man with brown hair. He is wearing a white button down shirt and a black tie with small dots. he is wearing a dark grey vest and a light grey suit. The man on the right is sitting straight with his hand in his lap. He is white with brown hair, a thick brown mustache, and round, wire frame glasses. He is wearing a white, button down shirt, a light tie, and a dark suit with black lapels]

The negotiations dragged on, pushing Lloyd George to the brink of despair. The British delegation split the Irish delegation in half and worked mostly with Griffith and Collins, creating great disgruntlement in the Irish camp. This would spell disaster for Collins and Griffith when they returned to Ireland. Fed up, Lloyd George sent the Irish an ultimatum: either they sign the treaty as it stands or refuse to sign and resume the war.

The Irish delegation was badly split. Griffith, Collins, and Duggan were in favor of the treaty while Barton and Gavan Duffy were against the treaty. Lloyd George put the pressure on the Irish delegation, claiming that he was preparing to tell Craig, his cabinet, and parliament that the negotiations had broken down. For their part, the Irish delegation was in constant communication with DeValera, insisting he come to London now and help them, but he refused. Lloyd George first got Griffith to agree to the treaty, which then forced the other Irish delegates to follow suit. The Irish delegation returned to 10 Downing Street and signed the treaty at 2:10 am on December 6th.

What exactly did they sign? In the end the treaty promised nothing that wasn’t part of the proposal prepared in July. Its main clauses were as follows:

Crown forces would withdraw from most of Ireland.

Ireland was to become a self-governing dominion of the British Empire, a status shared by Australia, Canada, Newfoundland, New Zealand and the Union of South Africa.

As with the other dominions, the King would be the Head of State of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Éireann) and would be represented by a Governor General

Members of the new free state’s parliament would be required to take an Oath of Allegiance to the Irish Free State. A secondary part of the oath was to “be faithful to His Majesty King George V, His heirs and successors by law, in virtue of the common citizenship”.

Northern Ireland (which had been created earlier by the Government of Ireland Act) would have the option of withdrawing from the Irish Free State within one month of the Treaty coming into effect.

If Northern Ireland chose to withdraw, a Boundary Commission would be constituted to draw the boundary between the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland.

Britain, for its own security, would continue to control a limited number of ports, known as the Treaty Ports, for the Royal Navy.

The Irish Free State would assume responsibility for a proportionate part of the United Kingdom’s debt, as it stood on the date of signature.

The treaty would have superior status in Irish law, i.e., in the event of a conflict between it and the new 1922 Constitution of the Irish Free State, the treaty would take precedence.

Irish Reaction

While the Treaty was celebrated in England and Lloyd George considered it a massive victory, the reaction in Ireland was quite different. DeValera refused to read the treaty and when it was published in the newspaper, he was furious it had been published without his review or approval. He publicly announced he could not “recommend the acceptance of this treaty”. Many IRA soldiers were confused and upset over the treaty’s terms, especially the oath of loyalty to the king. They couldn’t believe Collins would agree to this kind of treaty. DeValera planned to request the resignation of the three plenipotentiary members who were also in the cabinet: Collins, Griffith, and Barton, but Cosgrave convinced him to hear them out first.

Most of the military high command were in favor of ratifying the treaty, providing their reasoning during the private Dail debates on December 17th and 20th. Sean MacEoin reported that he had five hundred Volunteers and enough ammunition for seven minutes of fighting and that the British would wipe them out. Eoin O’Duffy agreed and Sean Hales, MacEoin, and O’Duffy pointed out that the intelligence situation had drastically changed as well. During the second meeting all the officers who made up GHQ and were members of the Dail and several who held commands in the country agreed that resuming the war would only end in disaster for the IRA.

Mulcahy sent out one of his many memos insisting that the army should stay out of politics and since it was an instrument of the state, it should have no opinion on public affairs. However, there were emergencies in which the State must consult with the Army heads and there were questions the army was entitled to answer. He did not believe the IRA could win militarily if the treaty was rejected and war resumed.

Griffith and Collins were under no illusions of what waited for them in London. Collins even wrote on the day he signed the Treaty:

“When you have sweated, toiled, had mad dreams, hopeless nightmares, you find yourself in London’s streets, cold and dank in the night air. Think – what have I got for Ireland? Something which she has wanted these past seven hundred years. Will anyone be satisfied at the bargain? Will anyone? I tell you this: early this morning I signed my death warrant. I thought at the time how old, how ridiculous – a bullet may just as well have done the job five years ago.” - Ronan Fanning, Fatal Path

On December 8th, the cabinet met with Collins, Barton, Griffith, and Cosgrave stating they would recommend approval of the Treaty to the Dail. De Valera, Brugha, and Stacks opposed them. They decided that the president would issue a press statement defining the position of the minority and that the Dail would hold public sessions on December 14th. During his statement Dev made it clear that he was opposed to the Treaty, starting the Dail debates on an even rockier foot and making himself the lightning rod for everyone who wanted to reject the Treaty.

The public debates broke down to two camps, the treatyites and the anti-treatyites. Those who supported the Treaty argued that the IRA had done all it could militarily do and to continue the war would be a disaster. They argued that the goal was never to drive the British to the sea but to break down that prestige which the enemy derived from his unquestionable superior force. To believe otherwise was fantasy. Collins offered his steppingstone argument and Hales argued that this was a jumping off point, and in a year or ten, Ireland will have freedom. Collins even told Hales in private that “the British broke the Treaty of Limerick [which ended the Jacobite war in 1691] and we’ll break this Treaty too when it suits us, when we have our own army.”

The Anti-treatyites refused or were unable to see Collins’ logic that this was the best they could do for now. Many did not want to accept partition, remain a part of the British empire, and especially despised the oath. And there were those in the middle, who looked to their comrades for an explanation or opinion on what to do. The problem for the anti-treatyites is that they didn’t have an alternative to offer. De Valera tried to introduce his external association idea, but it died in the water and while the anti-treatyites were full of principle, they had little else. For the treatyites it was all about accepting this limited victory in order to achieve a bigger one. As Collins put it this Treaty didn’t give the ultimate freedom, but “the freedom to achieve that end” and Mulcahy would say it provided a “solid spot of ground on which the Irish people can put its political feet.”

The Dail took a recess during Christmas and during this time, public opinion, the press, and the Church swung towards accepting the treaty. While the anti-treatyites would ignore or dismiss how the people felt, the treatyites used it to support their cause. As Christmas passed (the first Christmas Ireland had not been at war one way or another since 1914), the Dail reconvened and the attacks became increasingly personal which the Freeman’s Journal denouncing DeValera as lacking the ‘instinct of an Irishman in his blood’ and Dev accused Griffith of crookedness, and Brugha claimed that Collins was a hack who deliberately sought notoriety and had been built up as a heroic figure which he was not.

On January 7th, the final vote was taken and the Dail approved the Treaty by 64 to 57. De Valera resigned as president of the Dail Eireann on January 9th and stood for re-election. On January 10th, DeValera was defeated in the vote for the Dail presidency by 60-58 votes. He and all anti-Treaty deputies walk out, “as a protest against the election as President of the Irish Republic of the Chairman of the delegation, who is bound by the Treaty conditions to set up a state which is to subvert the republic.”

Griffith was elected President of Dáil Éireann. The Dáil was adjourned until 11 February. On January 14th the provisional government was established with Collins as Chairman.

The stage was set for Civil War

References

The Republic: The Fight for Irish Independence by Charles Townshend, 2014, Penguin Group

Fatal Path: British Government and Irish Revolution 1910-1922 by Ronan Fanning, 2013, Faber & Faber

Richard Mulcahy: From the Politics of War to the Politics of Peace, 1913-1924 by Padraig O Caoimh, 2018, Irish Academic Press

A Nation and Not a Rabble: the Irish Revolution 1913-1923 by Diarmaid Ferriter, 2015, Profile Books

Fatal Path: British Government and Irish Revolution 1910-1922 by Ronan Fanning

#irish war of independence#Ireland#Irish history#Irish Civil War#Anglo-Irish Treaty#Michael Collins#Eamon DeValera#history blog#queer historian#queer podcaster#Spotify#podcast episode

1 note

·

View note

Text

i’m no historian but the Wars of the Three Kingdoms did not end in 1653. it ended in 1691

“peace” may have occurred in 1653, as in no faction was engaging in war with another, but it absolutely was not peace. not only was the most severe genocide in early-modern europe still ongoing, but the aftermath of the 20 april coup brought brutal repressions by the military governors. conflict was still ongoing

and it’s unhelpful to label 1653 as the end of the period of actual warfare. there were the sealed knot uprisings, the naval wars with Netherland and Spain, monck’s coup (which would’ve been a violent uprising had the pro-regime forces not immediately surrendered to him), and the millenarian insurrection of january 6 (not kidding)

but my biggest gripe with the 1653 reckoning is it doesn’t encompass the revolution of 1688 and ensuing williamite-jacobite war, events which resulted in the passing and reneging of the treaty of Limerick (allowing for the anglo-protestant ascendency in Ireland), the act of settlement 1701 which de facto annexed Scotland, all of which contributed to continuing violent persecution of catholics across the isles. i’d argue that the brutality in Ireland even after the fall of Cavan fits the definition of war - the act of settlement 1652 and the ethnic cleansing and slavery of Hell-or-Connaught was a violent war on the Irish people, even though Ireland as a polity was no more

the end of the Commonwealth-Covenant-Confederation Wars (or, perhaps, war) in 1653 was a cessation of interfactional/interstate warfare but it was not a cessation of violence and belligerency and it was not the end of this period of historically impactful conflicts. the lasting realignment of the political system in the so-called three kingdoms was the revolution of 1688. this realignment brought the abolition of one of the ‘three kingdoms’, the transformation of another into a segregatory sectarian settler-colonial state (which would precipitate its total annexation 100 years later as a way of diluting the effects of the necessary climbdown on catholic persecution, which would precipitate the genocide of the great hunger, all of which ultimately led to the 1916 uprising and the partition), and the establishment in the other of the whig-tory political order which ruled the country (and over its neighbours) for 150-ish years unchallenged, and for the past 200-ish years with the pretension of electoral democracy

there was a ceasefire in 1653, yes, which was when a period of overlapping wars on the isles came to an end under the dominance of the military dictatorship. but a broader definition, a 52-year period of conflict, is needed to offer this period its necessary provenance. focusing only on the 1639-1653 wars does a disservice to the historical importance of the other conflicts, especially the revolution in England and the anti-jacobite subjugation in Ireland. acting like conflict ended in 1653 presents monck’s putsch as universally welcome, the 1688 revolution as politically inconsequential, charles stuart ii and william orange as heroes, and Irish history as irrelevant

a taxonomical term could or should exist for the 1639-1653 wars. but that which should be the wider umbrella term for this period of conflict, the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (or your favourite synonym), is way bigger than that

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐂𝐨𝐥𝐦 𝐌𝐢𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐞𝐥 𝐎’𝐒𝐡𝐞𝐚 | b. August 27, 1894

⤷ gryffindor • irish • catholic • half-blood but presumed muggleborn • estp • keeper • soldier • private • lance corporal • pro anglo-irish treaty of 1921 • ministry intelligence agent • orphan • portrayed by josh hartnett

#colm o’shea#hp ww1 era#hp wwi era#birthday: colm o’shea#*oc birthday#my aesthetic#of course he’s still open for friendships or even enemies!#happy birthday colm!!!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

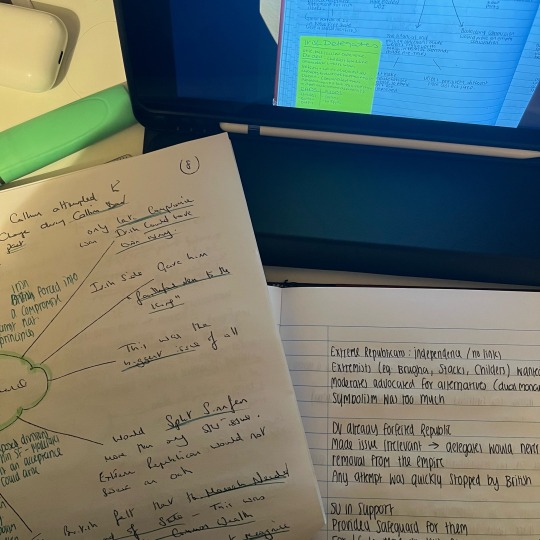

— monday 4th march

79 days until a levels

very history focused day (clearly!) today considering it got somewhat neglected last week

need to get back on my biology grind as i have basically all my flashcards made but next to none of them learnt..

2hr 43 on forest 🌲

completed today:

anglo-irish treaty essay plan

caught up on biology notes i missed

gym !!

2 notes

·

View notes