#1760s britain

Text

Yellow Silk Robe à la Française, 1760-1765, British.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#yellow#womenswear#extant garments#dress#silk#1760#1760s#robe à la française#1760s dress#1760s extant garment#1760s britain#V&A

159 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hand-painted Chinese silk robe and petticoat, probably English, c. 1760-1765. Tunbridge Wells Museum & Art Gallery.

234 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Late Louis XV portraits:

Suzanne Necker, née Curchod by Etienne Aubry (Artcurial - 15Feb22 auction Lot 59). Removed spots and cracks with Photoshop 2641X3306 @150 1.6Mj.

ca. 1764-1770 Augusta of Great Britain, duchess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel by Johann Georg Ziesenis (Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum - Braunschweig, Niedersachsen, Germany). From Wikimeia 1440X2060 @300 550kj.

#Rococo fashion#Louis XV fashion#curled hair#high coiffure#Suzanne Necker#Etienne Aubry#U décolletage#ruching#close sleeves#1760s fashion#Princess Augusta of Great Britain#Johann Georg Ziesenis#cap#bow#lace wrap#décolletage#lace bertha#fur-trimmed stomacher#fur-trimmed bodice#fur-trimmed over-skirt#fur-trimmed skirt

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

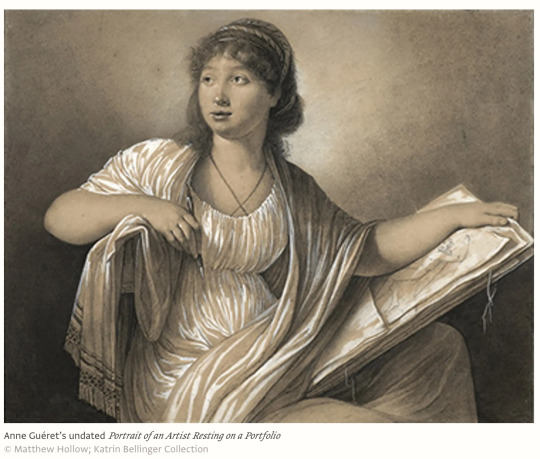

When talking about women artists, it is usual to reference Linda Nochlin’s groundbreaking 1971 essay, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? As Paris Spies-Gans—independent scholar and author of this new book—rightly says, it was a call-to-arms to make them visible. But that was over 50 years ago. One may ask now, what has changed since then? In recent years, the answer is a lot.

Around the world there has been a mini-flood of monographs and exhibitions on historic women artists, and their work is suddenly a profitable art market commodity. How to assess their careers remains a question, however. What was their place in and contribution to the art worlds they inhabited? Of what we know of them, what is inherited stereotyping on the one hand or over-eager feminist reading on the other? And to what extent is the current vogue for their work merely diversity box-ticking rather than genuine recognition?

This book sets out to place women artists working in Britain and France between 1760 and 1830—the “Age of Revolutions”—firmly within the art-historical narratives of the period. The task, Spies-Gans argues, demands more intellectual rigour than simply enhancing knowledge of their existence; and in an ideal world it should go beyond dealing with their careers as separate, simply because of their gender. A detailed analysis of the records of public exhibitions in London and Paris, chiefly the Royal Academy of Arts and the Académie Royale respectively, lies at the heart of this survey.

When talking about women artists, it is usual to reference Linda Nochlin’s groundbreaking 1971 essay, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? As Paris Spies-Gans—independent scholar and author of this new book—rightly says, it was a call-to-arms to make them visible. But that was over 50 years ago. One may ask now, what has changed since then? In recent years, the answer is a lot.

Around the world there has been a mini-flood of monographs and exhibitions on historic women artists, and their work is suddenly a profitable art market commodity. How to assess their careers remains a question, however. What was their place in and contribution to the art worlds they inhabited? Of what we know of them, what is inherited stereotyping on the one hand or over-eager feminist reading on the other? And to what extent is the current vogue for their work merely diversity box-ticking rather than genuine recognition?

This book sets out to place women artists working in Britain and France between 1760 and 1830—the “Age of Revolutions”—firmly within the art-historical narratives of the period. The task, Spies-Gans argues, demands more intellectual rigour than simply enhancing knowledge of their existence; and in an ideal world it should go beyond dealing with their careers as separate, simply because of their gender. A detailed analysis of the records of public exhibitions in London and Paris, chiefly the Royal Academy of Arts and the Académie Royale respectively, lies at the heart of this survey.

Consistent presence

Unusually for an art history book, data is presented in the form of charts and graphs. It is a powerful way of pressing home the point that the handful of prominent names that make it into standard art histories, such as Angelica Kauffman and Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, are not exceptions in a male-dominated world, but part of a much wider and neglected story. Women, it is demonstrated, were a consistent presence in public exhibitions throughout the period. More than 800 individual women artists exhibited in London, and at least 400 in Paris. This is an astonishing statistic. It blows apart the clichéd but hard-to-shift notions of women artists as few in number, pursuing careers that blurred the lines between professional and amateur.

In fact, Spies-Gans sees this period as one that witnessed the first collective rise of the professional female artist. Women used public exhibitions for exposure and opportunity. How they trained, what they chose to exhibit, their networks and commercial acumen, and the strategies they devised to overcome obstacles because of their gender, are examined over six chapters. Preconceptions are regularly challenged.

For example, rather than “still-life” and “flowers” (the lesser genres), most women exhibited portraiture. Maria Cosway’s striking image of the Duchess of Devonshire as the moon goddess Cynthia (1781-82) shows the sitter wrapped in ethereal clouds in a clever blend of “celebrity”, history and literary narrative. The French Academician (one of only four women) Adélaïde Labille-Guiard depicts herself at her easel with two attentive female pupils behind her. It is one of many self-portraits, or images of fellow female artists reproduced in the book that show women proudly in the act of creation. And it is one of many painted on a large scale, demonstrating ambition and painterly skill.

Another preconception, the idea that (broadly speaking) women did not practise history painting as they had no access to essential life-drawing classes, or, put about at the time, because they lacked the capacity for “invention”, is here successfully critiqued. Angélique Mongez, a pupil of Jacques-Louis David, was one of many French women to exhibit large, complex classical narratives that incorporated nude figures while placing the focus on female protagonists. In this context, Kauffman’s decision to represent “Design”—one of four allegorical paintings for the ceiling of the Royal Academy—as female rather than male suddenly assumes more weight.

In support of its central and forceful point not to pigeonhole women along conventional lines, A Revolution on Canvas is illustrated mainly with portraits and historical works: those by Marie-Victoire Lemoine, Marie-Nicole Dumont (showing herself juggling painting and motherhood), Marie-Geneviève Bouliar and Marie-Denise Villers, or Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Adèle Romany and Constance Mayer, may come as a revelation to most readers. And yet, while applauding this desire to avoid stereotypes, perhaps the emphasis towards history and portrait painting, despite the data showing they were the two most exhibited genres (narrative in Paris was second to portraiture), has meant a drift from the complete truth. For the reality is that women did paint still-life, flowers and portrait miniatures. It was what artists such as Anne Vallayer-Coster did brilliantly. And where is landscape? The second most exhibited genre in London, we learn, but not discussed at all by Spies-Gans.

Revolutionary turmoil

Setting the context for women’s growing ambition to pursue creative, public careers was the era itself—the revolutionary turmoil that prompted debates about democracy and citizenship, which in turn shone a light on women’s rights. It was the age of the philosophical writings of Olympe de Gouges and Mary Wollstonecraft. Spies-Gans acknowledges the paradox in charting women’s increasing creative freedom at a time when political democracy did not extend to them. Another inevitable contradiction – in a book devoted to women artists—is the author’s call to embed their histories into broader art-historical narratives, rather than to continue to treat them separately. That, surely, is the ultimate goal.

But how many of the artists that are discussed in this book are genuinely recognisable names, and how many of the 1,200 named exhibitors are represented in public collections? It is still the case that when female artists are mentioned, the question “Were they any good?” still hovers. Books focused on gender are arguably still necessary. By making its points compellingly and driving the agenda forward, A Revolution on Canvas is an important contribution to the field.

Paris Spies-Gans, A Revolution on Canvas: The Rise of Women Artists in Britain and France 1760-1830, Paul Mellon Centre/Yale, 384pp, 157 col and b/w illustrations, £45/$55 (hb), published 28 June (UK) and 5 July (US)

• Tabitha Barber is the curator of British Art 1500-1750 at Tate and was the lead curator and catalogue editor/contributor of British Baroque: Power and Illusion (Tate, 2020). She is currently preparing an exhibition on historic women artists to be staged at Tate Britain in 2024

#Women’s history#women in art#books for women#A Revolution on Canvas: The Rise of Women Artists in Britain and France 1760 - 1830#Maria Cosway#Anne Vallayer-Coster#Anne Guéret

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Travel back [...] a few hundred years to before the industrial revolution, and the wildlife of Britain and Ireland looks very different indeed.

Take orcas: while there are now less than ten left in Britain’s only permanent (and non-breeding) resident population, around 250 years ago the English [...] naturalist John Wallis gave this extraordinary account of a mass stranding of orcas on the north Northumberland coast [...]. If this record is reliable, then more orcas were stranded on this beach south of the Farne Islands on one day in 1734 than are probably ever present in British and Irish waters today. [...]

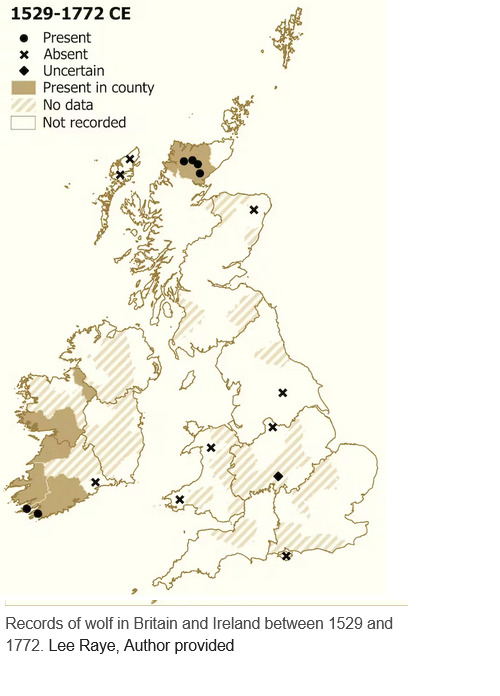

Other careful naturalists from this period observed orcas around the coasts of Cornwall, Norfolk and Suffolk. I have spent the last five years tracking down more than 10,000 records of wildlife recorded between 1529 and 1772 by naturalists, travellers, historians and antiquarians throughout Britain and Ireland, in order to reevaluate the prevalence and habits of more than 150 species [...].

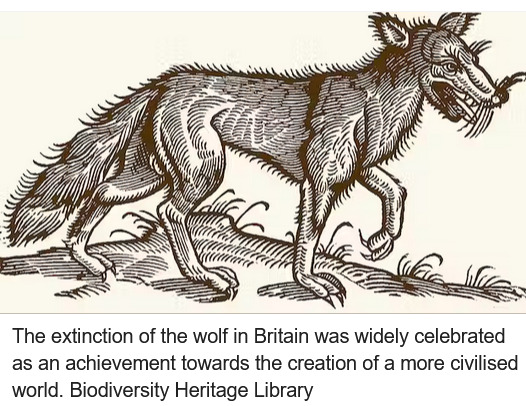

In the early modern period, wolves, beavers and probably some lynxes still survived in regions of Scotland and Ireland. By this point, wolves in particular seem to have become re-imagined as monsters [...].

Elsewhere in Scotland, the now globally extinct great auk could still be found on islands in the Outer Hebrides. Looking a bit like a penguin but most closely related to the razorbill, the great auk’s vulnerability is highlighted by writer Martin Martin while mapping St Kilda in 1697 [...].

[A]nd pine martens and “Scottish” wildcats were also found in England and Wales. Fishers caught burbot and sturgeon in both rivers and at sea, [...] as well as now-scarce fishes such as the angelshark, halibut and common skate. Threatened molluscs like the freshwater pearl mussel and oyster were also far more widespread. [...]

Predators such as wolves that interfered with human happiness were ruthlessly hunted. Authors such as Robert Sibbald, in his natural history of Scotland (1684), are aware and indeed pleased that several species of wolf have gone extinct:

There must be a divine kindness directed towards our homeland, because most of our animals have a use for human life. We also lack those wild and savage ones of other regions. Wolves were common once upon a time, and even bears are spoken of among the Scottish, but time extinguished the genera and they are extirpated from the island.

The wolf was of no use for food and medicine and did no service for humans, so its extinction could be celebrated as an achievement towards the creation of a more civilised world. Around 30 natural history sources written between the 16th and 18th centuries remark on the absence of the wolf from England, Wales and much of Scotland. [...]

In Pococke’s 1760 Tour of Scotland, he describes being told about a wild species of cat – which seems, incredibly, to be a lynx – still living in the old county of Kirkcudbrightshire in the south-west of Scotland. Much of Pococke’s description of this cat is tied up with its persecution, apparently including an extra cost that the fox-hunter charges for killing lynxes:

They have also a wild cat three times as big as the common cat. [...] It is said they will attack a man who would attempt to take their young one [...]. The country pays about £20 a year to a person who is obliged to come and destroy the foxes when they send to him. [...]

The capercaillie is another example of a species whose decline was correctly recognised by early modern writers. Today, this large turkey-like bird [...] is found only rarely in the north of Scotland, but 250–500 years ago it was recorded in the west of Ireland as well as a swathe of Scotland north of the central belt. [...] Charles Smith, the prolific Dublin-based author who had theorised about the decline of herring on the coast of County Down, also recorded the capercaillie in County Cork in the south of Ireland, but noted: This bird is not found in England and now rarely in Ireland, since our woods have been destroyed. [...] Despite being protected by law in Scotland from 1621 and in Ireland 90 years later, the capercaillie went extinct in both countries in the 18th century [...].

---

Images, captions, and text by: Lee Raye. “Wildlife wonders of Britain and Ireland before the industrial revolution – my research reveals all the biodiversity we’ve lost.” The Conversation. 17 July 2023. [Map by Lee Raye. Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

1K notes

·

View notes

Video

Kings Arms Inn Norfolk by Adam Swaine

Via Flickr:

Blakeney is an idyllic and largely unspoiled seaside village on the famously beautiful North Norfolk coast. It is also a thriving community with outstanding services and facilities. The Kings Arms is a traditional Norfolk inn just yards from the Quay, and is enduringly popular with locals and visitors alike

#inns#village inns#english inns#1760#pubs#village pubs#blakeney#norfolk#norfolk coast#norfolk villages#NORTH NORFOLK#Coastal#coast#east coast#Village#england#english#english villages#britain#british#uk#uk counties#UK VILLAGES#rural#rural villages#AONB#Adam Swaine#2022#Free House 1760

0 notes

Text

Dress. Scotland, Glasgow (place of manufacture), circa 1863. Wool, cotton.

Glasgow Museum Collections

Woman’s dress in light purple wool embroidered with in purple and white thread in tambour-work in an abstract pattern. High round neckline trimmed with lace, bodice loosely pleated from shoulders to wide v-shape at straight waistline with two narrow vertical pieces of gauze with tambour-work centre front with fastening behind of nine metal hooks and thread eyes attached to lining. Full-length sleeves with short pointed frill at shoulder edged with tambour-work, applied narrow piece of gauze around lower arm to suggest folded back cuff, hem edged with white lace. Skirt, full-length, pleated into waistband with tambour-work border around lower half, opening at front fastened by two metal hooks and thread eyes with small watch pocket in waistband. Bodice and sleeves lined with glazed cotton, skirt lined with cotton.

This beautiful dress is made from light purple wool. The silhouette follows the fashions of the early 1860s with a softly draped bodice and wide, full-length skirt that would have been held out by a steel-framed cage-crinoline.

The dress is decorated with an abstract pattern in purple and white thread tambour-work. The stitch resembles chain-stitch but is worked with the cloth stretch over a hoop, known as tambour, using a small hook rather than a needle. The technique originated in India and reached Britain the 1760s. By the early 19th century the west of Scotland was a leading centre for manufacturing tamboured muslins, with up to 20,000 women and girls in total working in the British industry.

475 notes

·

View notes

Text

For #NationalTeaDay 🫖☕️:

Teapot with Fossil Decoration

British, Staffordshire, c. 1760–65

Salt-glazed stoneware with enamel decoration

4 1/4 × 7 1/4 in. (10.8 × 18.4 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 37.22.6a,b

“Though it's got a surprisingly modern look, this teapot was made in the 18th-century in Staffordshire—the heart of Britain's pottery industry. The area’s limestone yielded prehistoric fossils, and potters often turned them into whimsical motifs for teapots.”

#animals in art#european art#British art#decorative arts#ceramics#Staffordshire#pottery#teapot#National Tea Day#tea kettle#monochrome#black and white#fossil#fossils

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

READY TO PLAY: chapter four.

Oblivious Melodies is an interactive fiction game, set in the in the fictional country of Angria, based on early industrial-era Britain. Following the Horne siblings and their emergence into gentry society, you will delve into a country divided by class, religious dissent, political factionalism, and the ever-encroaching interests of empire.

previous chapters: chapter one | chapter two | chapter three

Banner illustration: Richard Wilson, "Wilton House from the Southeast", 1760, Wilton House, Salisbury.

Thank you to everyone who has played so far - please reblog & share if you enjoy my work!

#interactive fiction#if#oblivious melodies#om game#interactive fiction wip#text adventure game#twine game#if game

83 notes

·

View notes

Photo

George I of Great Britain

George I of Great Britain (r. 1714-1727) succeeded the last of the Stuart monarchs, Queen Anne of Great Britain (r. 1702-1714) because he was Anne's nearest Protestant relative. The House of Hanover secured its position as the new ruling family by defeating several Jacobite rebellions which supported the old Stuart line.

King George may have struggled with both English and the English, often preferring his attachments in Germany, but his reign was a relatively stable one. His greatest legacy was as a patron of the arts, in particular, his support of musicians like Handel and such lasting cultural institutions as the Royal Academy of Music. He was succeeded by his son George II of Great Britain (r. 1727-1760).

Succession: The House of Hanover

The Glorious Revolution of 1688 saw the end of the reign of the male Stuarts and placed William, Prince of Orange on the throne as William III of England (r. 1689-1702) with his wife, the daughter of the exiled James II of England (r. 1685-1688), made Mary II of England (r. 1689-1694). Mary's sister became the ruling monarch in 1702 as Anne, Queen of Great Britain. When Anne died, so ended the Stuart royal line, which had begun with Robert II of Scotland (r. 1371-1390).

Queen Anne outlived her husband Prince George of Denmark (1653-1708) by six years; she died at the age of 49 on 1 August 1714 at Kensington Palace after suffering two strokes. Queen Anne had had many children, but all died in infancy. The greatest hope for an heir had been William, Duke of Gloucester (b. 1689), but he died in 1700, aged 12. Anne's official heirs, the Hanoverian family, were selected as such in the 1701 Act of Settlement.

The Hanovers were connected to the British royal line as descendants of Elizabeth Stuart (d. 1662), daughter of James I of England (r. 1603-1625) and brief Queen of Bohemia through her husband Frederick V of the Palatinate. The chosen successor – although she was not permitted by Anne to even visit England – was Elizabeth Stuart's daughter Sophia (l. 1630-1714), wife of the Duke of Brunswick and Elector of Hanover (a small principality in Germany the size of Yorkshire). Sophie of Hanover was Queen Anne's nearest relation of the Protestant faith, a vital consideration given that Parliament had already passed a law forbidding a Catholic to take the throne. For this reason, more than 50 other claimants to the throne had been deemed unsuitable. When Sophia died in 1714, her son, George Ludwig, took over the role of heir apparent to the British throne.

Continue reading...

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vails

I haven't actually talked about it here a lot, partly because I try not to do heavy history stuff here - this blog is meant to be a hobby, after all - and it's something I'm frankly too passionate (obsessed) about, but my main area of historic interest and focus, especially when it comes to my own personal research, is the history of domestic service. It is not an exaggeration to say it is my life's work.

Another reason I don't write about it often is I don't really know where to start. My breadth of knowledge on the subject is quite broad, so there's a lot I could say, but I think I'll try to write some small things about specific aspects of it.

Vails were, in the 18th (and I believe also 19th) century, basically what we could today call tips, often paid to servants. And when you read things written by the 'master class' of people being served, while they're obviously biased and exaggerating, it does become clear that servants rather enforced them. There wasn't a guild system for servants like there were for trades, but there were informal clubs and groups, and this is one of the ways they seem to have acted together, almost as a form of unionization. There's a letter to a British newspaper where the write says that he estimates many servants are doubling, tripling, or even quadrupling their annual salaries through vails. I could write more but I'll just transcribe some of my favourite passages on this subject from the book Life in the Country House in Georgian Ireland by Patricia McCarthy:

I will add too, while this is specifically talking about paid servants in Britain, you do see vails paid to enslaved people in America as well. Probably not as often, but Philip Vickers Fithian, who wrote a diary about his experiences in Virginia in the 1770s, writes about similar things of the enslaved people at the plantation he's staying at expecting their "Christmas boxes" of vails, although they weren't quite as beholden to the actual date of Boxing Day.

...

The customary scene in the hall, as their guests waited for their carriages or horses to be brought to the door, embarrassed many. [Marshall, Domestic Servants] Hosts feigned ignorance of their guests' fumbling in their pockets to find shillings and half-crowns to distribute to the servants, who had lined themselves up expectantly. Whether the motive for allowing the practice was to salve the collective conscience of the employers at paying such low wages is not clear. [Bridget Hill, Servants: English Domestics in the 18thc.] It was not confined to great houses, but was also expected in more modest establishments, although the amounts given were less. It was also not only expected on departure from the house of a friend: vails were disbursed by 'house tourists' to whichever servant showed them around - in most cases an upper servant.

...

An army officer described how much his visit to the house of a friend would cost him: 'The moment your departure is known, all the domestics are on the qui vive; the house-maid hopes you have forgotten nothing in packing up, if so, she will take care of it till you come again; this piece of civility costs you three ten-pennies; the footman carries your portmanteau .. to the hall, three more; the butler wishes you a pleasant journey - his greate kindness in so doing of course extracts a crown-piece; the groom brings your horse, assuring you 'tis an ilegant baste, and has fed well' - three more ten-pennies go; the helper runs after you with the curb-chain, which he has 'till this moment carefull secreted - two more; making a total of seventeen, or, in English money, upwards of fourteen shillings. A heavy tax for visiting a friend!' [Benson Earle Hill, Recollections of an Artillery Officervol. 1]

...

Richard Griffith from Bennetsbridge, Co. Kilkenny, complained in c.1760 in a letter to hise wife that 'an heavy and unprofitable Tax still subsists upon the Hospitality of this Neighbourhood .. in short while this Perquisite continues, a Country Gentleman may be considered but as a generous Kind of Inn-holder, who keeps open House, at his own Expence, for the sole Emolument of his Servants .. this Extravagance is not confined, at present, solely to the Country .. ; for a Dinner in Dublin, and all the Towns in Ireland, is even in a Morning, with a Person who keeps his Port, you may levee him fifty Times, without being admitted by his Swiss Porter. So... I shall consider a great Man as a Monster, who may not be seen, 'till you have fee'd his Keppers.' [R. and E. Griffith, A Series of Genuine Letters Between Henry and Frances, vol. 4]

...

Swift gives similar suggestions in Directions to Servants: 'By these, and like Expedients, you may probably be a better Man by Half a Crown before he leaves the House.' He further urges those servants who expect vails 'always to stand Rank and File when a Stranger is taking his Leave; so that he must of Necessity pass between you; and he must have more Confidence or less Money than usual, if any of you let him escape, and according as he behaves himself, remember to treat him the next Time he comes.'

...

Card money was particularly lucrative for butlers and footmen - so much so that, in London at least, such menservants refused service in houses where gaming parties were not held. [Marshall, Domestic Servants - Two footmen at the court of Queen Anne, Fortnum and Mason, used this perquisite as capital to begin their grocery business in London. Country House Lighting 1660-1890, Temple Newsam Country House Series No. 4] But it was vails that finally undermined the authority of the employers, who virtually allowed servants to dictate whom should be received, and then pretended not to notice when the servants extracted money from the departing guests.

...

In the London Chronicle a correspondent wrote in 1762 that 'Masters in England seldom pay their servants but in lieu of wages suffer them prey upon their guests'. George Mathew of Thomastown, Co. Tipperary, a man famous for his hospitality, was one of the first employers to ban the 'inhospitable custom' of giving vails to servants, and to compensate them by increasing their wages. This was apparently as early as the 1730s. His servants were warned that, if they disobeyed, they would be discharged. He also informed his guests that he would 'consider it as the highest affront if any offer of that sort were made'. [Anthologia Hibernica, I - No date given for this account, by 'Grand George' Mathew, who died in 1737, was the man described, who was host to Jonathan Swift at Thomastown in the 1720s, a visit described by Thomas Sheridan in A Life of the Rev. Dr. Jonathan Swift] A crusade against the giving of vails began in 1760 in Scotland, where seventeen counties issued appeals to abolish them. Four years later the movement had spread to London, resulting in riots there by footmen, the servants who stood to lose the most. [Marshall, Domestic Servants] It was probably at about the same time that employers from a number of counties in Ireland agreed among themselves to abolish vails. [Griffith, Series of Letters..., IV, 'An Agreement entered into among the Gentlemen of several Counties in Ireland, not to give Vails to Servants'] Like George Mathew before them, they decided to increase staff wages in an effort to compensate them for loss of earnings. One of them was Lord Kildare: in March 1765 he issued a directive from Carton to members of his household, stating that 'In Consideration of Vails &c, which I will not permit for the future to be received in any of my Houses upon any Account whatsoever from Company lying there or otherwise I shall give in lieu thereof... five pounds per annum each to the housekeeper, Maitre D'Hotel, cook and confectioner; three pounds per annum each to the steward at Carton, the butler, valet de chambre and groom of the chambers, and two pounds to the Gentleman of Horse.

...

And I will conclude with this funny account, about the penalty for being known amongst the staff to be a spendthrift, from the same book:

...

An unfortunate guest in England in 1754 found his punishment [for not giving vails] truly humiliating. 'I am a marked man,' he wrote, 'if I ask for beer I am presented with a piece of bread. If I am bold enough to call for wine, after a delay which would take its relish away were it good, I receive a mixture of the whole sideboard in a greasy glass. If I hold up my plate nobody sees me; so that I am forced to eat mutton with fish sauce, and pickles with my apple pie.' [Quoted in Marshall, Domestic Servants]

feel free to tip here (and yes the irony of this is not lost on me, although it did not occur to me until about halfway through writing this)

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elizabeth Gray Otis by John Singleton Copley, c. 1764

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

September 26 2022 (p.2) - The "Phantom Cats" Of Great Britain!

Deep in the forests of England and Scotland, Folklore and Urban Legend speak of Large, Puma-Like Cats that roam the countryside.

Generally believed to be escaped zoo animals or exotic pets, these "phantom cats" have actually been caught alive on multiple occasions. For example, in 1980, a live Puma was caught in Inverness-shire, Scotland.

In 1983, Eric Ley, a farmer from South Molton, England, claimed to have had lost as many as 100 sheep at the hands (paws? Teeth?) of a large cat over the span of three months. Royal snipers were sent out into the surrounding area to hunt down this big cat.

--

quick aside, please just read this excerpt from the wikipedia article

Despite extensive media coverage and both professional and amateur hunting for the creature, which in one unfortunate case saw a cryptozoologist have to be rescued after spending two nights stuck in his own trap...

That is infinitely hilarious to me and Idk why fsdkljdfs

--

No significant evidence has ever come from this case either proving or disproving the existence of this "Beast of Exmoor", as it's come to be called.

--

"[the cat was] as big as a middle-sized Spaniel dog..."

-William Cobbett, quoting the experience of a young boy he had met (1760s)

Alleged Puma sighting in England captured via Drone.

#cryptid#cryptozoo#cryptozoology#cryptozoolologist#big cats#puma#england#scotland#united kingdom#UK#great britain#the poor cryptozoologist#what kind of trap was it??#how did he get stuck??

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hiya, thanks for indulging me in my little hyper fixation!

(╹◡╹)♡

I have more questions if you’re interested in sharing!

Is there any connection between the real Port if Yokohama and the irl authors? Did Asagiri choose Yokohama for a specific reason or something like that?

Do the authors in a specific organisation get chosen for their irl relationships or was it randomized?

How do the literary texts have connections with manifestation of the ability in universe? (Some are obvious others not so much eg. For the Tainted Sorrow = gravity???????)

Sorry for the long ask. I hope you have a nice day! :D

I've hesitated to answer this ask because I wanted to be thorough and give each question due consideration. Further, the latter two questions rely a lot on my individual interpretation and I can't offer very much objectivity. But, I think I might be overthinking it, so below, please find attempts at answering each in turn.

The Port of Yokohama

The characters in Bungo Stray Dogs are named after and inspired by authors from modern Japanese literature. The "modern" era of Japan is generally (albeit not necessarily appropriately) measured as beginning during the Meiji Restoration, during which Japan restored centralized Imperial rule, ended a centuries-long seclusion by opening its borders to the West, and rapidly industrialized. For reference, Britain's Industrial Revolution spanned eighty years, from 1760 to 1840. By contrast, Japan industrialized within, roughly, forty years.

Japan reluctantly opened to the West under duress; Commodore Perry arrived in Japan with a squadron of armed warships, a white flag, and a letter with a list of demands from US President Fillmore. A year later, Japan signed the disadvantageous and exploitive Treaty of Amity and Commerce with the United States (日米修好通商条約, Nichibei Shūkō Tsūshō Jōyaku), which opened the ports of Kanagawa and four other Japanese cities to trade and granted extraterritoriality to foreigners, among other trading stipulations.

However, Kanagawa was very close to a strategic highway that linked Edo to Kyoto and Osaka, and the then-government of Japan did not relish granting foreigners so much access to Japan's interior. So, instead, the sleepy fishing village of Yokohama was outfitted with all the facilities and accoutrements of a bustling port town (including state-sponsored brothels), and the Port of Yokohama opened to foreign trade on June 2, 1859.

Thus, Yokohama is representative of Japan's opening to the West, including Western literature. Short stories and novels as the mediums we know them were Western imports to Japan, and Western literature shaped, inspired, and became subject to cross-cultural examination by Japanese authors.

This included Russian literature: Kameyama Ikuo, a Japanese scholar of Russian literature, described Fyodor Dostovesky's enduring popularity in Japan as follows:

In Japan, there were two Dostoevsky booms during the Meiji period [1868-1912], and The Brothers Karamazov being translated into Japanese for the first time in 1917 triggered a third. After that, critics like Kobayashi Hideo led fourth and fifth waves of popularity before and after World War II, and then Ōe Kenzaburō led the sixth wave around 1968, right when the student protests were at their height. Today we might say we’re in the middle of a seventh, with Murakami Haruki writing about how he was influenced by The Brothers Karamazov.

I've oversimplified Yokohama's role in Japan's modern engagement with the West substantially for the sake of brevity, but in short, yes, Kafka Asagiri chose the Port of Yokohama for a reason. Yokohama was, for a time, Japan's most influential, culturally relevant international metropolis, before becoming eclipsed by Tokyo in more recent history.

The Organizations

There aren't bright-line rules to explain why each character is in each organization, although it isn't randomized either.

Attempts to delineate between the organizations based on the irl!authors' philosophies, legacies, literary genres, degrees of acceptance or rejection of Western influence, etc., are inaccurate oversimplifications at best. (At worst, they're orientalist and, in some cases, conflate fascist ideology with literary aesthetics -- or literary aesthetics with violence; I've seen both, oddly enough.)

That said, the namesakes' irl relationships and literary impacts are sources of inspiration for the relationships in bsd, including between and among the various organizations. For example, Jouno, Tetchou, and Fukuchi were all among Japan's first Western-style newspaper editors. Kouyou and Mori were in the same literary circles and collaborated on influential publications; such as the magazine in which they penned anonymous reviews of works by emerging authors that made or broke careers, and which established modern literary criticism in Japan. Akutagawa is such an enduring and intimidating titan in Japanese literature; the sharpness of his prose and his ability to gut me like a fish suit bsd!Akutagawa's theatric and violent role within the Port Mafia.

But, Mori Ogai and Yosano Akiko were dear friends, Chuuya Nakahara idolized Kenji Miyazaki, and modern Japanese authors weren't mafiosos, private detectives, military police, or surreptitious intelligence officers. I'd warn against (i) cramming bsd's characters into oversimplified archetypes or literary devices and (ii) overinflating the importance of or reading any certainty into the patterns and reflections of the irl!authors. bsd makes dynamic and creative use of its source material to tell a story that's very much its own.

The source material absolutely adds depth, commentary, and intention to Kafka Asagiri's storytelling, but only if read within the context and framework of the story being told.

For an example of why strict dichotomies and oversimplified metanalysis don't work for comparing the various organizations, I wrote a post explaining why it's inaccurate to compare the Port Mafia and the Agency using an East vs. West framework here.

The Abilities

Yes, the literary texts inspire how the corresponding abilities manifest in-universe. At least, I think so, based on my own interpretations. For example, I see the green light across the bay from The Great Gatsby in the Great Fitzgerald and a throughline between Fyodor's bloody ability and the symbolic eucharist in Crime and Punishment.

I speculate about Fyodor's ability manifesting as imagery from Crime and Punishment here.

I mention the potential relationship between irl!Akutagawa's literary voice and bsd!Akutagawa's ability here.

I also share some thoughts on Dazai and the manifestation of No Longer Human based on narration from No Longer Human here.

For the Tainted Sorrow, in particular, is a poem about grief, which characterized much of Chuuya Nakahara's brief life. I've always experienced grief in intense fluctuations of weight -- sometimes heavy and immobilizing, sometimes untethering and billowing, often compulsive and consuming. It has an immense gravity.

I've always thought that bsd!Chuuya's manipulation of gravity emblemized his intense and layered relationship with grief -- for irl!Chuuya, his brother, his parents' brutal expectations, his lover, his friends, his son; for bsd!Chuuya, the Sheep, the Flags, the yet-named seven taken by Shibusawa's fog. But where irl!Chuuya was seemingly crushed by the gravity of what he lost, bsd!Chuuya defiantly persists with a rougish levity, his grief galvanizing his ferocious love for others and his desire to live for and in service of their memories.

To roughly quote bsd!Chuuya's character song, "I will manipulate even the weight of this cut-short life."

But, that's only my interpretation; take it with a grain of salt. Or with the weight of several pounds of salt. The extent to which it compels you is yours to decide.

#bsd#bungou stray dogs#bsd meta#bsd analysis#i have no idea if any of this is useful to anyone given its subjectivity and cursory overview of really complex topics#i have more thorough breakdowns of things like my crime and punishment analysis and the influence of the West on modern japanese literature#but each of these answers could be a dissertation length analysis and unfortunately I do not have the bandwidth to go totally wild on them

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is a direct connection between the expansion of [...] new [coffee] consumer culture in Europe [...] and the expansion of plantation slavery in the Caribbean. [...] [S]lave-based coffee was more important to the Dutch [Netherlands] economy than previously [acknowledged] [...]. [T]he phenomenal growth of [plantation slavery in] Saint Domingue [the French colony of Haiti] was partly made possible by the export market along the Rhine that was opened up by the Dutch Republic. [...] [E]arly in the eighteenth century, the Dutch and French began production in their respective West Indian colonies [the Caribbean] [...]. [C]offee was still a very exclusive product in Europe. [...] From the late 1720s, [...] in the Netherlands [...] coffee was especially widespread [...]. From the late 1750s the volume of Atlantic coffee production [...] increased significantly. It was at that time that the habit of drinking coffee spread further inland [...] [especially] in Rhineland Germany [...] [and] inland Germany [due to Dutch shipments via the river].

Although its consumption may not have been as widespread as the tea-sugar complex in Britain, there certainly was a similar ‘coffee-sugar complex’ in continental Europe [...] spread during the eighteenth century [...]. The total amount of coffee imported to Europe (excluding the Italian [...] trade) was less than 4 million pounds per year during 1723–7 and rose to almost 100 million pounds per year around 1788 [...]. In 1790 [...] almost half of the value of [Dutch] exports over the Rhine [to Germany] was coffee. [...]

---

The rising prices in the 1760s encouraged more investment in coffee in Dutch Guiana and the start of new plantations in Saint Domingue [Haiti]. Production in Saint Domingue skyrocketed and surpassed all the others, so that this colony provided 60% of all the coffee in the world by 1789. [Necessitating more slave labor. The Haitian revolution would manifest about a decade later.] [...]

In French historiography, the ‘Dutch problems’ are considered to be the slave revolts (the Boni-maroon wars) [at Dutch plantations]. [...] France made use of the Dutch ‘troubles’ to expand its market share and coffee production in Saint Domingue [Haiti], which accelerated at an exponential rate. [...]

---

[T]he Dutch Guianas [were] producing over a third of the coffee consumed in Europe [...] [by] 1767. The Dutch were the first Europeans to bring coffee cultivation under [substantial] European control [...]. Additionally, the Dutch regularly shipped and traded about one fifth of French coffee [most of which was produced by slaves in Haiti]. The Dutch flooded the Rhine region with coffee and sugar, creating a lasting demand for both commodities, as the two are typically consumed together. [...]

[T]he history of the slave-based coffee production in Surinam and Saint Domingue [Haiti] was pivotal in starting the mass consumption of coffee in Europe. [...] Coffee was a relatively ‘new’ product to Europeans: in one century coffee changed from being a [...] novelty [...] in [...] [urban] capitals to [...] [a product consumed regularly by many people]. The Dutch merchant-bankers organised coffee investment, enslavement, and planting and selling; [all] while not leaving the town of Amsterdam [...].

[This market] expansion ends in crisis [...] - a crisis caused by uprisings and revolutions, most notably, the Haitian one. Yet Germans still liked coffee. And the Dutch colonial merchant-banker[s] [...] learned something about [...] production, and perhaps also something about the role of the state in labour control: as soon as they could, they sent Johannes van der Bosch [governor-general of the East Indies] to Surinam and Java in order to solve the labour issues [by imposing the notoriously brutal cultuurstelsel "enforced planting" labour regime] and expand the colonial production of coffee.

---

Text above by: Tamira Combrink. "Slave-based coffee in the eighteenth-century and the role of the Dutch in global commodity chains". Slavery & Abolition Volume 42, Issue 1, pages 15-42. Published online 28 February 2021. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Italicized text within brackets added by me.]

63 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why u have such a cool styleeeee ?!?!

errrrrr........ urm..... pixel brush, size 4.... fluffy cat loaf. do all the lines double, many circle. funny......uuuuuuuuuuuu

The Industrial Revolution, also known as the First Industrial Revolution, was a period of global transition of human economy towards more efficient and stable manufacturing processes that succeeded the Agricultural Revolution, starting from Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840.[1] This transition included going from hand production methods to machines; new chemical manufacturing and iron production processes; the increasing use of water power and steam power; the development of machine tools; and the rise of the mechanized factory system. Output greatly increased, and a result was an unprecedented rise in population and in the rate of population growth. The textile industry was the first to use modern production methods,[2]: 40 and textiles became the dominant industry in terms of employment, value of output, and capital invested.

On a structural level the Industrial Revolution asked society the so-called social question, demanding new ideas for managing large groups of individuals. Visible poverty on one hand and growing population and materialistic wealth on the other caused tensions between the very rich and the poorest people within society.[3] These tensions were sometimes violently released[4] and led to philosophical ideas such as socialism, communism and anarchism.

The Industrial Revolution began in Great Britain, and many of the technological and architectural innovations were of British origin.[5][6] By the mid-18th century, Britain was the world's leading commercial nation,[7] controlling a global trading empire with colonies in North America and the Caribbean. Britain had major military and political hegemony on the Indian subcontinent; particularly with the proto-industrialised Mughal Bengal, through the activities of the East India Company.[8][9][10][11] The development of trade and the rise of business were among the major causes of the Industrial Revolution.[2]: 15

The Industrial Revolution marked a major turning point in history. Comparable only to humanity's adoption of agriculture with respect to material advancement,[12] the Industrial Revolution influenced in some way almost every aspect of daily life. In particular, average income and population began to exhibit unprecedented sustained growth. Some economists have said the most important effect of the Industrial Revolution was that the standard of living for the general population in the Western world began to increase consistently for the first time in history, although others have said that it did not begin to improve meaningfully until the late 19th and 20th centuries.[13][14][15] GDP per capita was broadly stable before the Industrial Revolution and the emergence of the modern capitalist economy,[16] while the Industrial Revolution began an era of per-capita economic growth in capitalist economies.[17] Economic historians agree that the onset of the Industrial Revolution is the most important event in human history since the domestication of animals and plants.[18]

The precise start and end of the Industrial Revolution is still debated among historians, as is the pace of economic and social changes.[19][20][21][22] Eric Hobsbawm held that the Industrial Revolution began in Britain in the 1780s and was not fully felt until the 1830s or 1840s,[19] while T. S. Ashton held that it occurred roughly between 1760 and 1830.[20] Rapid industrialisation first began in Britain, starting with mechanized textiles spinning in the 1780s,[23] with high rates of growth in steam power and iron production occurring after 1800. Mechanized textile production spread from Great Britain to continental Europe and the United States in the early 19th century, with important centres of textiles, iron and coal emerging in Belgium and the United States and later textiles in France.[2]

An economic recession occurred from the late 1830s to the early 1840s when the adoption of the Industrial Revolution's early innovations, such as mechanized spinning and weaving, slowed as their markets matured. Innovations developed late in the period, such as the increasing adoption of locomotives, steamboats and steamships, and hot blast iron smelting. New technologies such as the electrical telegraph, widely introduced in the 1840s and 1850s, were not powerful enough to drive high rates of growth. Rapid economic growth began to occur after 1870, springing from a new group of innovations in what has been called the Second Industrial Revolution. These innovations included new steel-making processes, mass production, assembly lines, electrical grid systems, the large-scale manufacture of machine tools, and the use of increasingly advanced machinery in steam-powered factories.[2][24][25][26]

21 notes

·

View notes