#1710s fashion

Photo

ca. 1710 Anne-Thérèse de Marguenat de Courcelles, Marquise de Lambert by Nicolas de Largillière (Musée Carnavalet - Paris, France). From tumblr.com/history-of-fashion/698349975992745984/ab-1710-nicolas-de-largillière-portrait-of. Fixed spots and edges with Photoshop 2048X2594 @72 1.7Mj.

#1710s fashion#late Baroque fashion#late Louis XIV fashion#Anne-Thérèse de Marguenat de Courcelles#nicolas de largillière#curly hair fripon curls#wrap#lining#split bodice

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pocket

1710s

Fashion Museum Bath via Twitter

#pocket#fashion history#historical fashion#1710s#18th century#stuart era#georgian era#accessories#embroidery#floral#united kingdom#fashion museum bath#popular

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

A woman's gown, 1775-80, English; figured silk satin, dyed rust colour, probably Spitalfields, c1715-19

#18th century#18th century fashion#spitalfields silk#fashion history#historical fashion#1710s#1770s#1770s fashion#extant garments

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guessing the decades of random historical paintings I have saved on my phone based on the style of clothing. I might do this more often since it was quite fun.

The high waistline with a small amulet on the top of the bodice, a flared part on the bottom of the bodice, big and short sleeves with minimal decor, long and slightly wide dress, also with minimal decor, incredibly low neckline, and the (probably) pommed bangs and big curly hair make me think that this is 1630s, but it could be a bit later than that.

The big sleeves with the folded parts, the low and rounded neckline with the transparent fabric around it and the hair that is tied up on top but loose behind makes me think that this might be 1530s, I can't be very sure though.

The elegant linen sleeves, wide collar, curly hair, seemingly wide breeches (thought they're not very visible from this angle), and the wide justacorp make me believe that this is possibly 1670s.

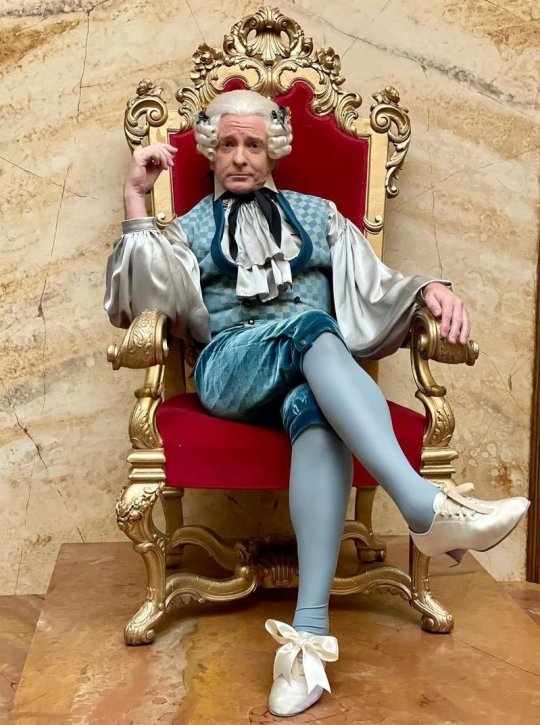

The curly and narrow powdered hair which is long at the back with devil horn bangs, the triangular neckline with a decorated bodice, the wide, puffy sleeves, low, triangular waistline, and slightly wide skirt makes me think that this is 1710s or maybe a bit later.

The short hair that is pushed downwards, big and long cravat with a bit of frill on the bottom part, long overcoat, short and tight undercoat, slightly loose sleeves, and sort of tight pantaloons make me think that this is 1810s or somewhere around that.

I want to say that this guy looks like Adam Sandler. The Chaperon is wide, his bangs are short, the jerkin is big and puffy with a gash in it, which makes the linen undershirt visible, his sleeves are puffy, and his linen sleeves slightly peak out, which makes me believe that is might be 1520s.

#art history#historical fashion#fashion history#16th century#17th century#18th century#19th century#1520s#1810s#1710s#1670s#1530s#1630s#baroque#rococo#regency#rennaissance

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kaigetsudo Dohan, Standing Woman, 1719

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

i want the kids to be plot relevant in the next seasons of ofmd if only because i think alma would love jim. i think they would be pals

#alma BROKE A PETRIFIED ORANGE IN TWO EQUAL CLEAN PARTS#THAT SHIT IS FOSSILIZED. IT IS A ROCK#HOW DID SHE DO THAT#also she wears pants when stede comes back#and in none of my extensive research of five websites on youth fashion in 1710s/20s did it say anything abt girls wearing pants#which i just think is cool :)#i want her to know that there are alternatives to just boy and girl gender yknow#also she looks like shed like knives#louis acts so much like how i would imagine a baby lucius would its scary#except with like . slightly more stede influence#i think lucius would be afraid of him#anyway that’s all ! no thoughts head empty#ofmd#our flag means death#alma bonnet

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Fair Lady: Late Baroque Era Set

(no fancy thumbnail this time, sorry) ♫ < baroque music

Please READ ALL OF THIS before downloading. I will not answer an ask if it was answered here. Read.

This is a late 17th-century/early 18th-century Baroque Set. You will get 25 items for women, girls, and toddlers! Towards the bottom, I will give you tips to start a Baroque Era Save (people to find on gallery and men/boy attire).

I would like to thank @the-melancholy-maiden @linzlu @sychik @batsfromwesteros @vintagesimstress @cringeborg @acanthus-sims @stereo-91 and sims 2 creator maya40 for the stuff I've used to make all of this. I'm sure there are more creators but I cannot recall their names off the top of my head. DM me if you see a piece of your mesh here so I can give proper credit. I would also like to thank @belleophile for testing these items for me.

The stuff in this set can work for the late 1660s-early 1710s.

WHAT YOU GET: You will get 3 hat hairs, 1 for each age I listed above, 2 Fontanges for adults that work with the hat slider mod, 4 adult hairs, an adult baroque hair comb piece, 1 adult baroque sash accessory used for court and portraits, 1 ribbon hair piece to go with a hair, and 13 dresses (2 1670s/1660s mantuas, 1 1680s-1710s Habit used for Hunting or Riding, 1 1690s-1710s court dress used for court occasions, 1 1690s-1710s jeweled portrait dress and 1 1660s-1670s portrait dress with sash, and finally 7 1690s-1710s mantuas used for everyday, formal, and seasonal wear. I've included 1 dress for a child and 1 dress for a toddler as well).

SMALL NOTICE ABOUT THE PIECES: The hairline on the hairs will not behave correctly if you have head shape presets on the sim. I've tried fixing that but no luck. If I manage to fix it, I will update it. The Hat Hairs are found in the HAT category and are not compatible with hairs you MUST download the hair files that I'll be including with them. This being said, if you remove sim clothing while they have the hat hair on, it removes the hair override too. It's strange, but just put the hat back on and it should fix. The comb, and ribbon accessory are also found in the hat category. The Sash is found in the GLASSES category. The 1660s-1670s Mantuas are not compatible with shoes, leggings, or socks. I've removed these options in CAS tools so you shouldn't have to worry about clipping. The Barbara 1670s Dress has a sash meshed onto it, and because of this does not behave well with bigger bodies. The same applies to the Henrietta 1670s Dress, as the pearls don't behave with bigger bodies. Same with the Sarah 1670s Dress jewels. The 1690s-1710s Mantuas will have small gaps if the sim is plus-sized. I have tried to fix these issues, but no luck. The hat hair fontange looks a bit gray without reshade or a lighting mod. @northernsiberiawinds has some good lighting mods. Other than that, it's fine. Below, is how it will look white with a lighting mod.

Everything has AT LEAST 20 swatches. Some things have more. There are only a few things that don't have this many swatches.

Here are some pics up close of what you are getting.

Here are some pics/fashion plates from this era.

Did I forget the 1680s mantua..? Oh no! Luckily, I've included this surprise 1680s dress you'll be getting as well for reading all of that. So 26 items! (here you can see hat hair fontange without lighting mods installed)

BAROQUE SAVE TIPS: These dresses will work for winter, summer, and traveling wear. Just add a fichu for summer wear or a shawl. For winter wear just add some long gloves and a cape. For men's stuff from this era, @stereo-91 has recolored some acanthus outfits which can be found here. I'll show you how they look below. I also recommend going to his gallery (ROTAMETERS91) as he has AMAZING builds for this era. For a little boy, @acanthus-sims has some stuff that can work.

DOWNLOAD

#baroque ts4#baroque sims 4#sims 4 baroque#sims 4 decades#my cc#historical cc#ts4 cc#historical sims 4#sims 4 historical#historical sims#sims 4 cc#the sims cc

344 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I'm trying to draw something for a friend. Both of our characters live in the late 1720s. They both have regular outfits, but I want to draw them wearing something fancy. My friend has described his character as having a very bad sense of fashion. I can't really picture what a bad outfit back then would look like. Do you?

Hello!

Well I haven't got all that much of a feel for what might have been considered a bad outfit back then, but there is one image that immediately comes to mind of someone who's very definitely badly dressed, and it's this guy. From the 4th panel of Hogarth's Marriage A la Mode (1743-45).

His individual garments look fine to me, but they're horribly mismatched! (And a bit old fashioned for the mid 40's.)

You'll note that the coat cuffs are made of a large brocade that contrasts with the main body of the coat, which was very popular in the first half of the century, but that style was meant to be worn with a matching waistcoat in the same brocade. Instead he's got a completely plain waistcoat that doesn't match at all.

And the breeches should match the main coat fabric, but his don't! The black and brown and beige clash awfully.

He's also got a lot more rings and a much bigger & sparklier earring than I've seen on any other guy from the era, which I speculate might have been tack and/or un-masculine, but I have no sources so don't quote me on that.

I just know that when 18th century guys are wearing rings in a portrait it's usually just one, and I've only ever seen simple little hoop earrings in a very few portraits. But again, emphasis on the "speculate" part of that sentence.

(And I've just noticed that the guy next to him has curling papers in his hair, which I think is probably also meant to make him look silly and not properly dressed. No idea what the opinion would have been about the folding fan dangling from the wrist of the next guy over, but it is intriguing. The very large beauty spot on his lip is probably meant to look bad though.)

That painting is a bit later than what you're asking about, but the style of matching cuffs & waistcoat was popular in the 20's too, so here are some examples of what it's supposed to look like.

A lot of them are very elaborate brocades paired with a solid dark coloured velvet, but sometimes it's a contrasting plain fabric with a ton of metal embroidery.

(1725)

(1723)

And an extant c. 1730's example from the NMS collection.

You might also look at 1710's images, because being a decade behind the current fashions would certainly make you badly dressed for the era.

(c. 1715-20)

So, I guess just put them in clashing parts of 2 or 3 different matched suits? (I am assuming you're asking about suits, since this ask was sent to me and I do not know very many things about dresses. Mostly only what I absorb from other costumers who post about it, and barely anyone does early 18th century.)

Please note that this does not apply to the 1780's-90's, fashion plates from those decades are incredibly full of clashing and mismatched suits. (Though it would probably still be bad to wear those ones on a very formal occasion.)

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

One thing I tend to see really disparate takes on is how much of Stede's presentation is masculine or feminine, and I keep thinking about it. The tricky thing is that of course standards of masculinity have changed between the early eighteenth century and now, and at the same time this production is very much not one that's going to be historically accurate in such a way that it confuses the audience!

So, 1717 masculinity first.

There's a stereotype that prior to Beau Brummell, there was no sense that men should be restrained in dress, but it's not true at all. Even in the 1710s and 1720s, English gentlemen were expected to have a certain soberness in their clothing - portraits show a preponderance of browns, as well as darker blues, greys, and occasionally reds; there's not that much trim, either, beyond buttons and occasionally a line of gold or silver braid. John Blathwayt is among the flashier, with a waistcoat and massive cuffs made out of a silvery damask - but attached to a brown silk (and really, grey-on-grey isn't that flamboyant). To a modern eye, the flowing wigs and stockinged calves relate to women's fashion, but both were symbols of masculinity in the period - women's hairstyles were more contained and natural, and their legs were covered with skirts.

The clothes Stede wears in the scenes set before he goes to sea generally reflect these norms. They're in darker tones, and cut fairly loose and not showing off his body. The orangey-brown anniversary outfit has the lightest colors and the closest fit, and it's still shades of brown and a pretty boxy shape. His cravat is often lacy, which really isn't very masculine for the period, but it's partially covered with a colored tie/secondary cravat - along with his lacy shirt cuffs, that's definitely something that can be read as a small expression of his style/queerness, which he's also half-concealing. In the betrothal scene, his cravat is actually a strangely rough fabric in a light grey, and I think it's tucked into his waistcoat so we can't actually see the ends.

I also want to note that the suit fabric really matches the upholstery in Stede's father's carriage. It's hard for me to not read this outfit as being chosen by Bonnet the elder to repress anything non-masculine about Stede, and also to show him as a possession, just like the carriage. On the other hand, the anniversary suit seems to be the brightest and most fitted, with a contrasting and I think floral-patterned waistcoat, and that was the scene where Stede tries to be more open than he's ever been with Mary about what he likes and wants.

There's a similar thing in the scene where Mary tells Stede to play with Alma and Louis. He starts off reading and ignoring Mary in a plain dark green coat, the ends of his cravat hidden behind his book and the top of it largely covered with a green tie. Then we jump cut to him playing with the kids and he has taken off the plain coat to reveal a patterned, light blue waistcoat (short and fitted), and he's tied the green tie around his head to uncover the white cravat, which is also revealed to have intricate lacy ends. Likewise, when he runs away to sea, he wears a fairly yellow waistcoat, embroidered with flowers - the only embroidery we see on him in the flashbacks apart from a little bit on his nightshirt right before he runs away.

So, how does this compare to what he wears as Captain Bonnet? (Part II)

#ofmd#ofmd costuming#our flag means death#ofmd meta#our flag means death costuming#stede bonnet#18th century english masculinity

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

1700's fashion?? OOHOHOH I might have to do another 1700's clan inspired by yours >:3

If you do please tell me so our cats can interact!

There's not a lot of resource on 1700-1710 in colonial American fashion since Americans were a bunch of bumpkins and not wearing fine garments of the upper class (I.e. the stuff that survives and stays in museums). So I'm kind of borrowing from late 1600s / some 1780s even. Expect settler fashion to always be like 50 years behind what's couture.

All that text jumble to say I'm rawdogging this.

#jcooc#jcasks#it's 3 am at an airport and I been up since 12 gimme a break#I'm too tired to make sense#thank you tho I love historical kitties#join us

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

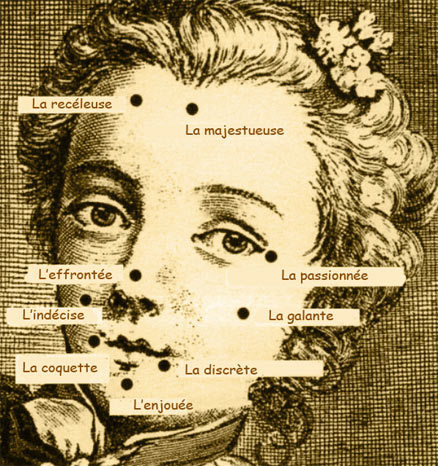

Thinking about how Izzy’s X tattoo can be read not only as Ed’s signature on account of his illiteracy, but also as a highly-fashionable 18th century beauty mark with all the codes contained therein.

Particularly popular in the 18th century French court, ‘mouches’ were patches of dark silk or taffeta in various shapes that were attached to the face (sometimes neck and bust, too) originally to cover scars but later as a hugely popular way to communicate flirtatious messages. They caught on in England, too. The diarist Samuel Pepys hated mouches until his wife got some and then he started to associate them with sexiness. Both men and women of fashion wore them, but they were much more popular with the girls as mouches allowed them to flirt without endangering their reputation. Plausible deniablity - oh this? It’s just a freckle.

In the context of mouches, the placement of Izzy’s tattoo by the eye means the wearer is ‘passionate’, and the X shape can mean ‘discreet’. HOWEVER. Some women, once engaged, placed a beauty patch high on their left cheek, like Izzy, to indicate they were taken. Once married, the wearer would swap the patch to the right side. Which of course Izzy can’t do - always the bridesmaid, never the bride.

In the 1710s, mouches were at the height of their popularity, and heavily satirised in popular culture. So it’s plausible that even Ed knew what the placement meant and thought it would be terribly funny to commemorate Izzy’s passionate nature, his discretion in keeping Blackbeard’s secrets, and his devotion… with a mouche tattoo. Just the thing for his dapper first mate.

743 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mantua

c.1709-1710

England or the Netherlands

Royal Ontario Museum (Object number: 973.214)

#mantua#fashion history#historical fashion#1700s#1710s#stuart#stuart era#18th century#gold#blue#silk#damask#england#the netherlands#royal ontario museum

309 notes

·

View notes

Text

OFMD Stede Bonnet as a Macaroni: Wealth, Gender and Sexuality in the 18th Century Fashion World

Historical Inaccuracy in Our Flag Means Death? Never!

Historical inaccuracy! I hear you cry. A Macaroni in 1717!?! It is true macaroni fashion was really a late-18th century fashion trend, seemingly reaching its peak in the 1770s. However Our Flag Means Death is nothing if not historically inaccurate. Stede’s costumes seem to take inspiration from across the 18th century rather than worrying about what would have actually been worn in 1717.

Early 18th century suits tended to have round necklines, loose-fitting sleeves with wide cuffs, long waistcoats that stoped just above the knee, and coats with full skirts just a little longer that the waistcoat.

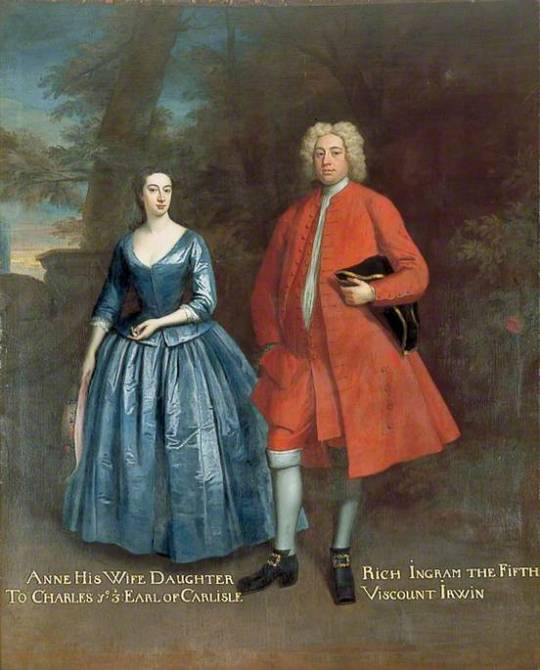

[Left: Matthew Prior, oil on canvas, c. 1713-1714, by Alexis-Simon Belle, photo credit: St John's College, University of Cambridge, via Art UK.

Middle: Matthew Hutton of Newnham, Hertfordshire, oil on canvas, c. 1715, by Johannes Verelst, photo credit: National Trust Images, via Art UK.

Right: William Leathes, Ambassador Brussels, oil on canvas, c. 1710-1711, by Herman van der Myn, photo credit: Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council Collection, via Art UK.]

As the century continued we get standing collars and turned down collars but round necklines were still around as well, sleeves got tighter with smaller cuffs, the waistcoats got shorter and the coats lost their skirts.

[Left: Thomas ‘Sense’ Browne, oil on canvas, c. 1775, by Nathaniel Dance-Holland, photo credit: Yale Center for British Art, via Art UK.

Middle: Sir Brooke Boothby, oil on canvas, c. 1781, by Joseph Wright of Derby, photo credit: Tate, via Art UK.

Right: David Allan, oil on canvas, c. 1770, by David Allan, photo credit: Royal Scottish Academy/National Galleries of Scotland (Antonia Reeve), via Art UK.]

Stede’s collars are inconstant some are rounded but others are turned down and Ed’s purple suit has a standing collar. Many of Stede’s coats have wide cuffs, but most have little skirt to them. His teal suit from the pilot has a bit of a skirt but its paired with a short waistcoat.

Most of Stede’s waistcoats are short with the exception of his suits from both the wedding portrait with Mary and the the family portrait. Both suits are very straight giving him a boxy appearance and are pretty different from most of the suits we see him in.

All in all I don’t think they were aiming for historically realistic clothes but with the collars, short waistcoats, and lack of skirts I get more of a late-18th century vibe.

So what was a Macaroni?

A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1785), defined macaroni as follows:

An Italian paste made of flour and eggs; also a fop, which name arose from a club, called the maccaroni club, instituted by some of the most; dressy travelled gentlemen about town, who led the fashions, whence a man foppishly dressed, was supposed a member of that club, and by contraction stiled a maccaroni.

The macaroni club was said to have comprised of young men who had gained a taste for French and Italian textiles on their Grand Tour (a traditional trip taken tough Europe by upper class men when they came of age). The earliest reference to the club is from a letter from Horace Walpole to Lord Hertford on the 6th Feb 1764:

at the Maccaroni Club (which is composed of all the travelled young men who wear long curls and spying-glasses),

In his book Pretty Gentleman: Macaroni Men and the Eighteenth-Century Fashion World Peter McNeil suggest the club was actually Almack’s. Almack’s was a private club at 50 Pall Mall that was attended by prominent Whigs including Sheridan, Fox and the Price of Wales. (p52) While the name may have originated from the men at Almack’s it was soon used to describe any man who followed the associated fashion trends.

So what were these trends?

Hair

“Still lower let us fall for once, and pop

Our heads into a modern Barber’s shop;

What the result? or what we behold there?

A set of Macaronies weaving hair.”

~ The Macaroni by Robert Hitchcock

Probably the most iconic aspect of macaroni fashion was the hair. “It was the macaroni attention to wigs that caused most consternation” explains Peter McNeil. The macaroni hair “matched the towering heights of the female coiffure, with a tall toupee cresting at the centre front. The wig generally had a long tail at the neck (’queue’), which when folded double was called the ‘cadogan’, all of which required regular dressing with pomade and powder, sometimes in the colours of pink, green or red.” (p45)

The height of the macaroni hair was a point of particular fascination in macaroni caricature exaggerating it beyond what the macaroni were probably actually wearing. Compare below Tom’s hair in the satirical print What is this my son Tom to the self portrait of Richard Cosway, who was satirised by Mary Darly as “The Miniature Macaroni” (a reference both to his height and his career as a miniature painter).

[Left: What is this my son Tom, print, c. 1774, published by Sayer & Bennett, via The British Museum.

Right: Self-Portrait, Ivory, c. 1770–75, by Richard Cosway, via The Met.]

The way Stede usually wears is hair is not particularly macaroni nor particularly 18th century for that matter. The exception to this is his wig from The Best Revenge Is Dressing Well though even this doesn’t have the iconic macaroni hight.

Interestingly both Stede and Ed are wearing flowers in their hair. While there are certainly depictions of women with flowers in there hair I’m not aware of this being a trend in mens fashion at all. However macaroni were known for wearing large nosegays.

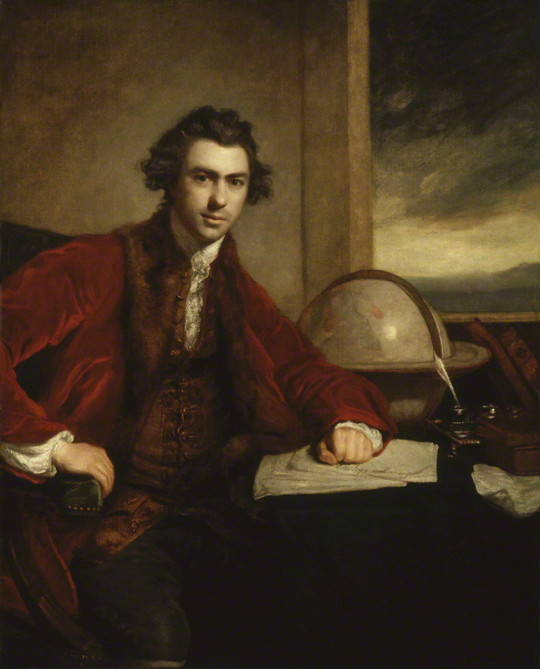

While the tall hair was certainly iconic not all macaroni wore their hair tall. Joseph Banks, who was satirised as “The Fly Catching Macaroni” by Matthew Darly, is depicted in his portrait with a fairly typical 18th century hairstyle. Its not the hair alone that makes a macaroni, it was just one aspect of the fashion.

[Sir Joseph Banks, oil on canvas, c. 1771-1773, by Sir Joshua Reynolds, via Wikimedia.]

Suit

“If I went to Almack’s and decked out my wrinkles in pink and green like Lord Harrington, I might still be in vogue.” ~ Horace Walpole to Lord Hertford, 25 Nov 1764

Menswear of the period consisted of the same basic elements; shirt, stockings, breeches, waistcoat and coat. What differentiated the macaroni from others was the fabric, cut, colour and trimmings of the suit. “At a time when English dress generally consisted of more sober cuts and the use of monochrome broadcloth,” explains Peter McNeil “macaronism emphasised the effects associated with French, Spanish and Italian textiles and trimmings”. Popular amongst macaroni were brocaded and embroidered silks and velvets, sometimes further embellished with metallic sequins, simulated gemstones and raised metallic threads. Popular colours included pastels, pea-green, pink, red and deep orange. (McNeil, p30-32)

Far from wearing “monochrome broadcloth” Stede likes a “fine fabric” and dresses in a range of colours, we see him in teal, pink, purple, green, white, red, peach &c.

Tightly cut French style suits known as habit à la française were popular with macaroni. (McNeil, p14) Stede’s suits vary somewhat in cut but some are very French. The peach suit Stede wears in We Gull Way Back particularly has a very macaroni feel to me. Compare it to the English suit (left) and the French suit (right).

From the back you can see the English suit has more of a skirt to it.

Both Stede’s suit and the French suit are somewhat plain but have been paired with a floral embroidered waistcoat, while the English suit has a matching plain black waistcoat.

[Left: English suit, wool, silk, c. 1755–65, via The Met, number: 2009.300.916a, b.

Right: French suit, Silk plain weave (faille), c. 1785, via LACMA, number: M.2007.211.47a-b.]

Fabric covered button’s were common in the 18th century, you can see them on both the French and English coats above. In contrast Stede wears a lot of metal buttons. Steel buttons were popular amongst macaroni, a trend that was satirised in Steel Buttons/Coup de Bouton.

[Steel Buttons/Coup de Bouton, print, c. 1777, by William Humphrey, via The British Museum.]

Pumps and Parasols

“Maccaronies who trip in pumps and with Parasols over their heads” ~ Mrs Montagu

High heels had been popular amongst men during the 17th century. The Royal Collection Trust explains:

In the first half of the 17th century, high heeled shoes for men took the form of heeled riding or Cavalier boots as worn by Charles I. As the wearing of heels filtered into the lower ranks of society, the aristocracy responded by dramatically increasing the height of their shoes. High heels were impractical for undertaking manual labour or walking long distances, and therefore announced the privileged status of the wearer.

(Royal Collection Trust, High Heels Fit for a King)

In 17th century France Louis XIV popularised red-heels by turning them into a symbol of political privilege, which in turn spread the fashion to England. But with the sobering of menswear in England around the turn of the century the high heel and the red-heels went out of fashion. (see Bata Shoe Museum Toronto, Standing TALL: The Curious History of Men in Heels)

The high heel had a bit of a resurgence in the 1770s with macaroni fashion. The Natural History of a Macaroni snipes that the macaroni’s “natural hight is somewhat inferior to he ordinary size of men, through by the artificial hight of their heels, they in general reach that standard”. (Walker’s Hibernian Magazine, July 1777, p458)

Red-heels were reintroduced to England by young men returning from their Grand Tours. A young Charles James Fox (satirised by Mathew Darly as “the Original Macaroni”) wore such French style red-heeled shoes. The Monthly Magazine recalls a young Fox as a “celebrated “beau garçon” with “his chapeau bras, his red-heeled shoes, and his blue hair-powder.” (Oct 1806) and The Life of the Right Honorable, Charles James Fox recalls him in his “suit of Paris-cut velvet, most fancifully embroidered, and bedecked with a large bouquet; a head-dress cemented into every variety of shape; a little silk hat, curiously ornamented; and a pair of French shoes, with red-heels;” (p18) And in Recollections of the Life of the Late Right Honorable Charles James Fox B.C. Walpole recalls him as “one of the greatest beaus in England,” who “indulged in all the fashionable elegance of attire, and vied, in point of red heels and Paris-cut velvet with the most dashing young men of the age. Indeed there are many still living who recollect Beau Fox strutting up and down St. Jame’s-street, in a suit of French embroidery, a little silk hat, red-heeled shoes, and a bouquet nearly large enough for a may-pole.” (p24)

Compare the French style red-heeled shoes of Louis XIV to Stede’s red-heeled shoes.

[Left: detail of Louis XIV, oil on canvas, c. 1701, by Hyacinthe Rigaud, via Wikimedia.]

However most macaroni were depicted wearing the more standard late 18th century low-heeled bucked shoes. Where they distinguished themselves was the size and decoration of the buckles. “Such buckles could be set with pate (lead glass) or ‘Bristol stones’ (chips of quartz), or diamonds if you were very rich.” Explains peter McNeil, “The new macaroni fashion was for huge silver or plated Artois shoe buckles which the Mourning Post claimed weighed three to eleven ounces.” (p90)

While certainly not as iconic has his heels Stede also wears these sorts of shoes. Compare below the shoes from a macaroni caricature to Ed wearing Stede’s shoes (I couldn’t get a good shot of Stede wearing them).

[Left: detail of How d'ye like me, print, c. 1772, published by: Carington Bowles, via The British Museum.]

“A great many jewelled accessories accompanied the macaroni look”, writes Peter McNeil, “They included hanger swords, very long canes, clubs, spying glasses and snuff-boxes.” (p68) Tragically we don’t see Stede with a fashionable dress sword or a cane but we do see him with another accessory popular amongst macaroni; a parasol.

Popular in France parasols/umbrellas were adopted by the macaroni. They were popular amongst both men and woman in France but in England they had a feminine connotation. (McNeil, p129) In the 1780s as umbrellas became more popular amongst men there was a cultural pushback to the perceived gender transgression. On the 16th of August 1780 the Morning Post complains of of the “canopy of umbrellas” bemoaning that “the effeminacy of the men, inclines them to adopt this necessary appendage of female convenience”. On the the 4th Oct, 1784, the Morning Chronicle published a letter complaining of “that vile foppish practice of sheltering under a umbrella”. The author of this tirade writes that while “the ladies should be allowed to secure their beauty and persons from the heat of the sun, or the inclemency of the weather,” because “it is natural, and has a striking effect”, that “to see a great lubberly cit, bounce from his shop, with a coat, hat, and wig that are not together worth one groat,” sheltering “from the influence of the solar beam” was “intolerable.” However:

The macaroni being of the doubtful gender, may in part claim a feminine right; his dress is too delicate to bear an heavy shower, perhaps his person is so too; but a coach, if a clean one is to be found would serve his purpose much better, as there would be less likelihood of his being washed away into the kennel, which he deserves to be kicked into for his d-----d affectation.

Wealth

Born from rich young men returning from their tours with a taste for French and Italian textiles macaroni fashion was expensive. Certainly a working class man would not be able to afford Stede’s wardrobe. Both the sheer amount of clothes he has as well has the fabrics those clothes are made of are indications of wealth. However to say that Stede’s wardrobe is only an indication of wealth would be missing part of picture.

Most rich upper class English men (including colonial) wore plain monochrome suits. Even amongst the gentry macaroni fashion was not the norm. Compare bellow George Washington (left) who was a wealthy planation owner, but notably not a macaroni, to Richard Cosway (right) who was a famous macaroni.

[Left: George Washington, oil on canvas, c. 1796, by Gilbert Stuart, via Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Right: Detail of The Academicians of the Royal Academy, oil on canvas, c. 1771-72, by Johan Zoffany, via The Royal Collection Trust.]

In spite of the expense macaroni fashion was not exclusive to the upper classes. “Macaroni dress was not restricted to members of the aristocracy and gentry,” writes McNeil, “but included men of the artisan, artist, and upper servant classes, who wore versions of this visually lavish clothing with a distinctive cut and shorter jackets. Wealthier shopkeepers and entrepreneurs also sometimes wore such lavish clothing, particularly those associated with the luxury trades, such as mercers and upholsterers -” (p14)

It was possible to copy certain aspects of macaroni fashion on a cheeper budget. The hairstyle in particular was achievable without braking the bank. And there were ways to replicate the effects of certain expensive fashion trends for cheeper prices. For example patterns could be printed rather than embroidered.

[Left: printed waistcoat, cotton, c. 1770–90, via The Met, number: 35.142.

Right: embroidered waistcoat, silk, c. 1780–89, via The Met, number: 2009.300.2908.]

The Town and Country Magazine complains “we now have Macaronies of every denomination, from the colonel of the Train’s-Bands down to the errand-boy.” (McNeil, p169) The Morining Post mocks macaronies that couldn't financially keep up with the trends:

The macaronies of a certain class are under peculiar circumstances of distress, occasioned by the fashion, now so prevalent, of wearing enormous shoe-buckles; and we are well assured that the manufactory of plated ware was never known to be in so flourishing a situation.

(14 Jan, 1777)

In 18th century England, class was about more than just how much money you had. It was about pedigree. “English society was particularly alert to those whom it felt were using clothes to achieve a social status they did not merit” explains McNeil. Richard Cosway was a famous macaroni from modest background. Born to a Devonshire headmaster he was sent to London to study painting at 12. He became a very successful miniature painter and grew rich from the patronage of the Prince of Wales (later George IV) and Whig circles. In Nollekens and his Times J.T. Smith writes of Cosway:

He rose from one of the dirtiest boys, to one of the smartest of men. Indeed so ridiculously foppish did he become that Mat Darly, the famous caricature print-seller, introduced an etching of him in his window in the Strand, as ‘The Macaroni Miniature Painter’

(McNeil, p105-14)

But it was not only the Darlys that satirised Cosway Hannah Humphrey mocks Cosway as a social climber in A Smuggling Machine or a Convenient Cos(au)way for a Man in Miniature which depicts him standing under the petticoats of his much taller wife Maria. In the background there is a picture of Cosway climbing a ladder that rests upon a woman (she is believed to either be Angelica Kauffman or the Duchess of Devonshire). Below this reads:

Lowliness is Young Ambitions Ladder,

Whereto the climber upward turns his Face

But when he once attains the upmost round

He then unto the Ladder turns his back,

Looks unto the clouds - scornin [sic] the base degrees

By which he did assend.

Shak. Jul. Caesar.

[A Smuggling Machine or a Convenient Cos(au)way for a Man in Miniature, print, c. 1782, by Hannah Humphrey, via The British Museum.]

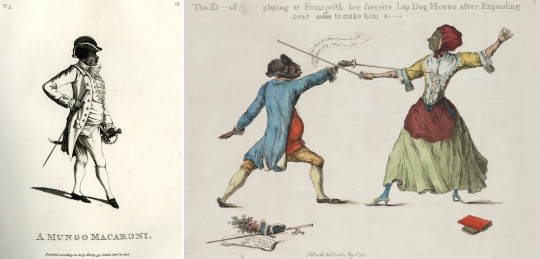

Another famous macaroni not born into the aristocracy was Julius Soubise. Brought to England from the West Indies as a slave he was taken in by Catherine Hyde, the Duchess of Queensbury. She gave him a leisured childhood, in which he was taught to play and compose for the violin, was taught to fence by Domenico Angelo, and learned oration from David Garrick. “Macaroni caricatures of Soubise parodied a foppish upstart whose outfits and entertainments, financed by the Duchess, affronted both racial and social expectations of an African male.” Writes Petter McNeil, Soubise was satirised as “a Mungo Macaroni” an “offensive term meaning a rude or forward black man.” (p118)

[Left: A Mungo Macaroni, print, c. 1772, by Matthew Darly, via The British Museum.

Right: The D------ of [...]-- playing at foils with her favorite lap dog Mungo after expending near £10000 to make him a----------*, print, c. 1773, by William Austin, via Yale Center for British Art.]

The expense of Stede’s wardrobe is a key part of the narrative. Stede has nice fancy luxurious things. Ed wants nice fancy luxurious things. Ed was born a poor brown boy and while he may be rich now he can never truly change his class. He could be as rich as Richard Cosway or Julius Soubise but to the gentry he will always be that poor brown boy.

Gender

As we have already seen in the tirade against men using umbrellas the macaroni was perceived as being of “the doubtful gender”. (The Morning Chronicle, 4 Oct, 1784)

The Natural History of a Macaroni writes that there “has within these few years past arrived from France and Italy a very strange animal, of the doubtful gender, in shape somewhat between a man and monkey,” that dresses “neither in the habit of a man or woman, but peculiar to itself”. The author states that “they are in no respect useful in this country”:

that the minister of the war department would give orders to have them enlisted for the service of America: we do not mean to put them on actual duty there. Alas! they are as harmless in the field, as they are in the chamber, but they may stand as faggots to cover the loss of real men.

(Walker’s Hibernian Magazine, July 1777, p458-9)

A “faggot” being “A man who is temporarily hired as a dummy soldier to make up the required number at a muster of troops, or on the roll of a company or regiment.” (see OED)

[The Masculine Gender & The Feminine Gender, etching with touches of watercolour, c. 1787, Attributed to Henry Kingsbury, via The Met.]

The macaroni wasn’t just considered effeminate because of the way they dressed but also because of their interests and the way walked and talked. Famous for playing fops and macaroni, the actor David Garrick did a lot to establish the character of the macaroni in the public mind. In his poem The Fribbleriad Garrick mocks the men who were offended by his performances asserting, perhaps accurately, that they were offended because it was them he mocked. He portrays a group of angry effeminate men meeting in order to seek revenge on him for his portrayal of them:

May we no more such misery know!

Since Garrick made OUR SEX a shew;

And gave us up to such rude laughter,

That few, ’twas said, could hold their water:

For He, that player, so mock’d our motions,

Our dress, amusements, fancies, notions,

So lisp’d our words, and minc’d our steps,

The macaroni had become more than simply an effeminate man, he had become a new sex. Something not quite man or woman. Something in-between. A new description of a macaroni asks the question:

Is it a man? ‘Tis hard to say - A woman then

- A moment pray -

So doubtful is the thing, that no man

Can say if ‘tis a man or woman:

Unknown as yet by sex or feature,

It moves - a mere amphibious creature.

(McNeil p169)

Sexuality

Much like today in the 18th century effeminacy was associated with homosexuality. Men who had sex with other men were known as mollies. A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1785), defined a molly as “A Miss Molly; an effeminate fellow, a sodomite”. In the History of the London Clubs (1709), Ned Ward characterises mollies as follows:

There are a particular Gang of Wretches in Town, who call themselves Mollies, & are so far degenerated from all Masculine Deportment or Manly exercises that they rather fancy themselves Women, imitating all the little Vanities that Custom has reconcil’d to the Female sex, affecting to speak, walk, tattle, curtsy, cry, scold, & mimick all manner of Effeminacy.

“By the 1760′s,” explains Peter McNeil, “too much attention to fashion on the part of a man was read as evidence if a lack of interest in women”. (p152)

Macaroni were often portrayed as incapable or simply uninterested in sexual relations with women. This attitude is expressed by Mr. Bate in the following dialogue from The Vauxhall Affray; Or, the Macaronies Defeated:

Mr. Fitz-Gerall: I always though a fine woman was only made to be looked at.

Mr. Bate: Just sentiments of a macaroni. You judge of the fair sex as you do your own doubtful gender, which aims only to be looked at and admired.

Mr. Fitz-Gerall: I have as great a love for a fine woman as any man.

Mr. Bate: Psha! Lepus tute es et pulpamentum quæris?

Mr. Fitz-Gerall: What do you say, Parson?

Mr. Bate: I cry you mercy, Sir, I am talking Heathen Greek to you; in plain English I say, A macaroni you, and love a woman?

Mr. Fitz-Gerall: I love the ladies, for the ladies love me.

Mr Bate: Yes, as their panteen, their play-thing, their harmless bauble, to treat as you do them, merely to look at

While lack on interest in woman does not necessarily mean attraction to men, Matthew Darly takes the implication there in his 1771 set of macaroni caricatures which induces a print entitled Ganymede, a reference to Zeus’ male lover of the same name. Ganymede is believed to be a parody of Samuel Drybutter who had been arrested for attempted sodomy in January 1770. Darly also includes the character Ganymede in Ganymede & Jack-Catch. Jack-Catch is a reference to the infamous English executioner John Ketch. In the print Jack-Catch says, “Dammee Sammy you’r a sweat pretty creature & I long to have you at the end of my String.” Ganymede replies, “You don’t love me Jacky”. Jack-Catch is holding a noose with one hand and stroking Ganymede’s chin with the other. Jack-Catch is soberly dressed in typical 18th century menswear, while Ganymede’s dress is distinguished by his lace ruffles and styled wig. The print is not only suggesting that macaroni are sodomites but making a joke of the execution of them. The punishment for a sodomy at this time in England being death by hanging.

[Left: Ganymede, print, c. 1771, Matthew Darly, via The Met.

Right: Ganymede & Jack Catch, print, c. 1771, Matthew Darly, via The British Museum]

An anonymous letter to the Public Ledger (5 Aug, 1772) says blatantly what others had already implied. “The country is over-run with Catamites, with monsters of Captain Jones’s taste, or, to speak in a language witch all may understand, with MACCARONIES”. The writer warns macaroni who have “escaped detection” as sodomites and “therefore cannot fairly be charged” that they have not avoided suspicion:

Suspicion is got abroad-the carriage-the deportment-the dress-the effeminate squeak of the voice-the familiar loll upon each others shoulders-the gripe of the hand-the grinning in each others faces, to shew the whiteness of the teeth-in short, the manner altogether, and the figure so different from that of Manhood, these things conspire to create suspicion; Suspicion gives birth to watchful observation; and, from a strict observance of the Maccaroni Tribe, we very naturally conclude that to them we are indebted for the frequency of a crime which Modesty forbids me to name. Take warning, therefore, ye smirking group of Tiddy-dols: However secret you may be in your amours, yet in the end you cannot escape detection;

Bows on His Shoes

18th century shoes were typically buckled, laces and ribbons were simply unfashionable. As mentioned previously macaroni were distinguished by the size and decoration of the buckles. So are Stede’s bows simply ahistorical? Well there are references to 18th century men wearing laces and ribbons.

Towards the end of the 18th century laces started to come into fashion. Appeal from the Buckle Trade of London and Westminster, to the Royal Conductors of Fashion (1792) complained that despite how “tender and effeminate the appearance of Shoe Strings” the “custom of wearing them has prevailed.”

Perhaps the most intriguing reference is that of Commissioner Pierre Louis Foucault’s papers where he details the surveillance, investigation and entrapment of "pederasts” in Paris. It is important to note that the word “pederasty” was used synonymously with “sodomy” in the 18th century and did not denote age simply sex. An Universal Etymological English Dictionary (1726) defines “A pederast” as “a Buggerer” and “Pederasty” as “Buggery”.

Foucault and the men working with him identified particular clothing worn by men seeking sex with other men that he called the “pederastical uniform”. In Foucault’s papers men are described as being “attired in such a way as to be recognized by everyone as a pederast”, “clothed with all the distinctive marks of pederasty”, or simply “dressed like a pederast”. This “uniform” generally included “some combination of frock coat, large tie, round hat, small chignon, and bows on the shoes.” Jeffrey Merrick in his article on Foucault speculates that these men dressed this way to signal to each other. However when questioned by police they would understandably deny such a purpose, one man when questioned about his outfit responded that everyone “dresses as he sees fit”. (Jeffrey Merrick, Commissioner Foucault, Inspector Noël, and the “Pederasts” of Paris,1780-3)

Conclusion

I’m not saying Stede is intended to be a macaroni. If that were the case they would have given him the iconic macaroni hairstyle. However the costuming team has clearly pulled from fashion trends that were associated with effeminacy and homosexuality. While OFMD is evidently wholly unconcerned with creating period accurate costumes the costumes are still clearly inspired by historical fashions. Perhaps the curtains really are just blue but maybe Stede wears bows on his shoes because he’s gay.

#I had way too much fun doing this#our flag means death#ofmd meta#stede bonnet#queer history#macaroni#historical fiction#fashion history

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historical Fashion Details in Art. ca.1710

478 notes

·

View notes

Note

was matthew sent to boarding school or was it only jack?

Just Jack and more successfully after the boom in girls schools from the 1870s, Zee (The example of Maata Mahupuku and Katherine Mansfield as classmates and likely lovers comes to mind.) Arthur probably tried a couple like Eton or Harrow for him in England. But when Alfred and Matt were in their school years so to speak, it wasn't yet as fashionable for the upper classes to send their children to institutions like the so-called 'public schools' (Private boarding schools in yanklish). I do think Alfred probably did some time at Harvard when it was a day school rather than a proper university yet. The norm for him was that private tutors were hired and kept on to teach either a single family's children or several families children. Children also learned from their parents. I think Arthur took a very keen interest in Alfred's studies and had him extremely well educated to the standards of the day.

In French Canada, the schools were run by the Catholic Church and Francis did throw in some extracurriculars like art, music, etc but he didn't show much promise in things just yet and they were mostly kaput by 1710 or so. Unlike in the British colonies where there were dozens of newspapers and Boston printing presses especially were smashing out literature left right and center, Canada didn't have a single one until the British founded Halifax and New England settlers brought one up from Boston.

Jack is a funky situation because while the hedge schools of Ireland saw something of a continuance in early Australia (I've seen this stated, refuted, restated and refuted so I'm just rolling with it( the British were very late to introducing schooling in Australia compared to how fast it happened in New Zealand just across (four thousand kilomètres) the ditch. So you have a fascinating situation where there are parchment makers and book makers and other literary trades cropping up often supporting the many European scientists who make the journey but there's very little actual formal education for the actual inhabitants well into the 1820s, 1830s and 1840s. So Jack is bounced through some schools and more than a few tutors. He got what he considers the best of his education harassing the hell out of Mary Anning and the various nerds who got into boats for six fucking months to look at kangaroos.

#the ask box || probis pateo#arthur and the children || bilge rat and his bouncing baby bilge rats#jack || a land of summer skies#matthew || my country is winter#alfred || o beautiful for spacious skies

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Speaking of ahistorical gay pirate fashion: There's something deeply weird about Stede's collars.

When he's at real ease (at sea), his shirt is gaped open, but you'll note that his collar is starched upward so that the shirt points are facing up toward his chin -- not a fashion from the 1710s, but rather from the 1770s.

Figure 1. Dandy en déshabillé.

When he's embodying his most Captain-like persona -- 'sea-faring butch,' if you will -- his neck is fully covered up with cravat, stock, jabot, whatever. Shirt points are often (always?) absent.

Figure 2. Intensely wealthy and impeccably dressed weirdo.

His neck is covered up similarly (no shirt points) when he goes back to Bridgetown in 1x10, though his cravat is tucked sensibly away beneath his waistcoat. He also had no visible shirt points before married life, though he hid bright colors and lacy cravats under drab jackets.

Figure 3. Man on brink of divorce realizing that perhaps giving up his shirt points was Not Enough.

Figure 4. Man about to make terrible life choice wonders if maybe adding more colored cravats to his wardrobe will feel sufficiently adventurous for the next sixty-odd years.

When he's actually in the middle of married life, though? Stede's collars are fucking weird. They're folded down and away, looking very much like either Peter-Pan collars or, frankly, the fashionable look for 19th century boys who hadn't yet hit puberty. On top of that, his jackets also have teeny tiny lapels, which end up doubling the effect of making Stede look a bit turtled into his own shoulders -- smaller and, ahem, spineless.

Figure 5. Authorities unsure whether local deadbeat dad was coerced into flight by own yellow cravat knotted too tightly under man's stupid collar.

Figures 6 and 7. Married men: Are they obligated to wear weirdly matching or contrasting cravats tied under tiny squished-down collars, or is it just This Fucking Guy.

And then, for people who are much cleverer than me, there are...

..the Outliers.

These are the fuckers that, imo, are the most indicative of whatever the hell self-transformation Stede is going through. But fucked if I know exactly what they're saying.

Figure 8. Recently resurrected idiots of the Caribbean wonder: how many collars can they leave open? And does wearing the solitaire anyway keep it Respectable?

Figure 9. Clueless moonlit asshole unaware that his "marriage" collar, silk cravat/shirt, not-black-but-very-dark solitaire and wtf poorly fitted double-breasted waistcoat are somehow the goddamn height of queer seduction.

Figure 10. Man attempting to regain his feeling of ease on the sea by wearing nightwear that is not buttoned up to his chin is shocked to discover that life remains stressful.

Figure 11. Newly poor but happily divorced man still somehow finds new fashion statement before seeking lost love: cotton weave gathered at the shoulder seams, wide but folded down collar, romantic lace-up that not only fastens nowhere near his chin but can also be loosened for peak nipple play, should any nearby dread pirates feel the urge.

#real talk this Figure 1 gag I've got going on right now might be my new favorite Thing#our flag means death#costume#fashion#meta#stede bonnet#and his stupid fucking collars#though this also gets perilously close to#CRAVAT THEORY

255 notes

·

View notes