#örvar-odds saga

Text

Hjalmar bids farewell to Örvar-Oddr after the Battle of Samsø

by Mårten Eskil Winge

#mårten eskil winge#hjalmar#örvar oddr#duo#swedish#hervarar saga#tyrfing#art#sagas#saga#norse mythology#gesta danorum#germanic#mythological#europe#samsø#history#mythology#european#scandinavian#scandinavia#old norse#nordic#sweden#northern europe#germanic heroic legend#battle of samso#orvar oddr#örvar-odds saga#blood brothers

183 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I was wondering, do you have any information about the word goðlauss? I've seen it mentioned online a couple of times on pages that defined it as the attitude of a man who didn't rely on the gods but only on himself and his luck to achieve his goals, and I know it apparently appears at some point in Landnámabók. But is there any wider context around it? Like, do we know anything else about it, does it appear anywhere else, was it a historical thing or a literary invention, was it just an Icelandic thing, was it regarded as a positive or a negative quality or was it more of a neutral thing, etc.? Thank you in advance!

The word literally means 'godless,' goð being specifically a heathen god (in contrast to guð, which can be used for the Christian God). The word seems to only occur in the nicknames of Bersi guðlauss and Þorir guðlauss; we get a little bit of context in the case of the latter where Landnámabók says that Þórir and his son Hallr didn't blót but "believed in their own might and main" (trúðu á mátt sinn ok megin). Other than Old Icelandic having two words for "god/God," there's no reason to believe goðlauss would mean anything different from what godless does in English, and I don't think this one co-occurrence is reason to import the entire complex of [at trúa á mátt sinn ok megin] into the definition of goðlauss.

At trúa á mátt sinn ok megin is a sort of formulaic phrase that recurs in the sagas to describe a sort of "noble heathen" (see also: belief in "the one who created the sun"). While there's nothing unlikely about pre-Christian people not worshiping the gods, generally when someone is described this way in the sagas it's a literary device that reframes the heathen past of Scandinavia so that it prefigures the coming of Christianity. For example, Hrólfr kraki and his entourage are all said to have believed in "their own might and main" while all of their enemies are the bad kind of heathen, sacrificing and doing evil magic. It would be too much of an anachronism for Hrólfr kraki -- a Migration Age Danish hero -- to be Christian, but he could prefigure the coming of Christianity to Scandinavia and give the Christian audience a hero that would allow them to see their own belief as the completion of a potential that was always there. Whenever one of these "might and main" heathens does encounter Christianity (e.g. Færeyinga saga, Ólafs saga helga, Örvar-Odds saga), they convert pretty much immediately.

Again, this isn't to say that there weren't really pre-Christians who didn't believe that worshiping the gods was a good idea, and its use as a literary device could easily be secondary to its existence as a historical phenomenon. But with the possible exception of Þórir, about whom we have very little information generally, we don't really get to read it in isolation from its use as a literary device.

For more see "The Noble Heathen: A Theme in the Sagas" by Lars Lönnroth.

The word goðlauss does also appear in Barlaams saga ok Jósafats, not as a nickname, but is most likely a scribal error, as it's a variant reading and the other variants make more sense (it's calling gods "godless").

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

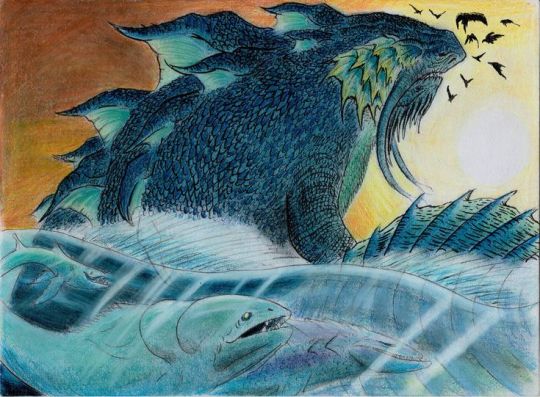

Hafgufa

Hafgufa is a sea creature, purported to inhabit Iceland's waters (Greenland Sea) and southward towards Helluland. Although it was thought to be a sea monster, research suggests that the stories originated from a specialised feeding technique among whales known as trap-feeding.

Pic by berloga-workshop.com

The hafgufa is mentioned in the mid-13th century Norwegian tract called the Konungs skuggsjá ("King's Mirror"). Later recensions of Örvar-Odds saga feature hafgufa and lyngbakr as similar but distinct creatures.

According to the Norwegian didactic work, this creature uses its own vomit like chumming bait to gather prey fish. In the Fornaldarsaga, the hafgufa is reputed to consume even whales or ships and men, though Oddr's ship merely sailed through its jaws above water, which appeared to be nothing more than rocks.

In the Speculum regale (aka Konungs skuggsjá, the "King's Mirror"), an Old Norwegian philosophical didactic work written in the mid-13th century, the King told his son of several whales that inhabit the Icelandic seas, concluding with a description of a large whale that he himself feared, but he doubted anyone would believe him about without seeing it. He described the hafgufa as a massive fish that looked more like an island than like a living thing. The King noted that hafgufa was rarely seen, but always seen in the same two places. He concluded there must be only two of them and that they must be infertile, otherwise the seas would be full of them.

The King described the feeding manner of hafgufa: The fish would belch, which would expel so much food that it would attract all the nearby fish. Once a large number had crowded into its mouth and belly, it would close its mouth and devour them all at once.

Its mention in the Speculum regale was noted by Olaus Wormiaus (Ole Worm) in his posthumous Museum Wormianum and by another Dane, Thomas Bartholin the senior. Ole Worm classed it as the 22nd type of Cetus, as did Bartholin, but one difference was that Ole Worm's book printed the entry with the skewed spelling hafgufe. Odd's saga

In the later version of Örvar-Odds saga dating to the late 14th century, hafgufa is described as the largest sea monster of all, which fed on whales, ships, men, and anything it could catch, according to the deck officer Vignir Oddsson who knew the lore. He said it lived underwater, but reared its snout above water for a duration until the tide changed, and that it was the nostril and lower jaw which they had sailed in-between, although they mistook these for two massive rocks rising from the sea.

Örvar-Oddr and his crew, who started from the Greenland Sea were sailing along the coast south and westward, towards a fjord called Skuggi on Helluland (also given by the English-translated name of "Slabland"), and it is on the way there that they encountered two monsters, the hafgufa ('sea-reek') and lyngbakr ('heather-back').

The aspidochelone of the Physiologus is identified as the potential source for the hafgufa lore.

Although the original aspidochelone was a turtle-island of warmer waters, this was reinvented as a type of whale named aspedo in the Icelandic Physiologus. In the Icelandic aspedo was described as a whale being mistaken for an island, and as opening its mouth to issue a perfume of sorts to attract prey. Halldór Hermannsson observed that these were represented as two distinct illustrations in the Icelandic copy; he further theorized that this led to the mistaken notion of separate creatures called hafgufa and lyngbakr in existence, as occurs in the saga.

Contrary to the saga, Danish physician Thomas Bartholin in his Historiarum anatomicarum IV stated that the hafgufa ('sea vapor') was synonymous with 'lyngbak'. He added that it was on the back of this beast that St. Brendan read his Mass, causing the island to sink after their departure. The Icelander Jón Guðmundsson's Natural History of Iceland also equated the lyngbakr and hafgufa with the beast mistaken for an island in St. Brendan's voyage. The island-like creature is indeed told of in the legend of Brendan's voyage, though the giant fish is named Jasconius/Jaskonius.

Hans Egede writing on the kracken (kraken) of Norway equates it with the Icelandic hafgufa, though has heard little on the latter. and later, the non-native Moravian cleric David Crantz's History of Greenland treated hafgafa as synonymous with the krake in the Norwegian tongue. However, Finnur Jónsson for instance has expressed skepticism towards the notion which developed that the krake had its origins in the hafgufa.

In 2023, scientists reported observed behaviour of whales resembling that of the Hafgufa of legends, by staying stationary on the sea surface with their jaws open and waiting for fish to swim into mouths. The whale may also use chewed up fish to attract more fish. The scientists noted that the earliest description of Hafgufa described it as a type of whale, and proposed that this behaviour of whale as the origin of the Hafgufa myth which became more fantastic in later centuries.

Pic by MonsterKingofKarmen

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cryptober Day 19: The Kraken.

The Kraken is a famous sea monster said to dwell off the coasts of Norway and Greenland. The colossal size and fearsome appearance attributed to the Kraken have made it a very common ocean-dwelling monster in various fictional works. It is also one of the largest (if not the largest) cryptids that may have ever existed.

The 13th century Icelandic saga Örvar-Odds tells of two massive sea-monsters called Hafgufa ("sea mist") and Lyngbakr ("heather-back"). The Hafgufa is believed to be a reference to the Kraken. They are said to be the biggest creatures in the ocean, and it swallows up everything that it can.

It is very possible the legend of the Kraken could have been attributed to early sightings of a colossal squid. In 2012, scientists discovered a giant squid that matched the physical description of the Kraken through deep sea exploration. Giant squids are estimated to grow to about 13-30+ meter, or 43-100+ feet in length, including the tentacles. These creatures normally live at great depths, but have been sighted at the surface and have reportedly attacked ships. Also, "Kraken dung" that was found on the shores by Vikings has been proven to actually be amber.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

“…Militarism is closely associated with the social legitimization of hegemonic masculinity —a dominant form of masculinity that many individuals strive toward but only a few attain. While hegemonic masculinity nominally places men in a social position superior to women, it also serves to create socially exclusive hierarchies among men through the marginalization and subordination of both femininity and nonconformist forms of masculinity (Connell 2000, 2005; Connell and Messerschmidt 2005; Hooper 2001). Hegemonic masculinity, by its nature, forces all other men to position themselves in relation to the form of masculinity that is being promoted or honored at any given time.

Traditional traits of hegemonic masculinity might include risk-taking, the enforcement of command structures and disciplinary hierarchies, physicality, aggression, violence, and overt expressions of heterosexuality (Hinojosa 2010). Lower-status men who conform to this status quo can receive benefits from those men who occupy the top of social hierarchies, thereby legitimizing and reinforcing the hegemonic status of the latter (Connell and Messerschmidt 2005). Today, hierarchies of hegemonic masculinity can be easily identified in numerous contexts, such as militaries, militia organizations, and professional sports teams (Bickerton 2015; Connell and Messerschmidt 2005; Higate and Hopton 2005; Hinojosa 2010; Hooper 2001).

There is good evidence for a culture of hegemonic masculinity among Viking Age societies. While perceptions of masculinity were undoubtedly imbued with their own shades of nuance across space and time, cultural similarities in the material record speak to broadly homogenous attitudes toward masculinity and its associations with militarism (Hadley 2016:262). Political power lay in the hands of war leaders and their retainers, who were most able to exploit and perpetuate hierarchies of masculinity to reinforce their influence. Expressions of masculinity may also have been closely associated with religious ideologies that reflected the sacral power and status of the elite. It has been suggested, for example, that the mediating role that Germanic kings held between the gods and populations before the Christianization process was expressed sexually through demonstrations of masculinity and virility (Clunies Ross 1985).

…When considered within a wider context, the perpetuation of hegemonic models of masculinity may have legitimized and fueled expressions of power and competitive behavior (Connell 2000), with significant implications for sociopolitical hierarchies and perceptions of gendered power. There has been some debate as to how gender was conceptualized and expressed among Scandinavian societies (Back Danielsson 2007; Clover 1993; Norrman 2000). Carol Clover (1993) has argued that Viking Age societies possessed a “one sex” perspective of gender that, instead of polarizing femininity and masculinity, equated masculinity with power. As a result, expressions of masculinity were celebrated and emphasized. Clover’s hypothesis is borne out in saga narratives that contrast the Old Norse term hvatr (vigorous or manly), used most often in reference to men, with the term blauðr (weak or cowardly), which often refers to women.

This implies that an individual’s status could have been positively or negatively influenced by words or actions considered hvatr or blauðr (see Clover 1993 and discussion below). This portrayal of gendered power aligns well with the concept of hegemonic masculinity because the competitive nature of masculine hierarchies would have encouraged individuals to constantly seek to enhance their status by discrediting others. The intense rivalries that could emerge as a result can be seen in the culture of insult, hypermasculinity, and feuding that abounded among Scandinavian societies. Eddic poems and the sagas are replete with examples of male antagonists exchanging insults (Old Norse flyting), which usually involved boasts of masculinity and the humiliation of one’s opponent, as in Örvar-Odds saga, Hárbarðsljóð, and Helgakviða Hundingsbana I (Orchard 2011; Pálsson and Edwards 1985). Some insults, such as nið, which was associated with accusations of breaking taboos, cowardice, and/or sexual deviance, were so powerful that their use was mitigated by law (Almqvist 1965, 1974; Clover 1993; Meulengracht Sørensen 1980).

The influence of hegemonic masculinity is further illustrated when we consider gendered norms among Scandinavian societies. The roles of men and women were nominally well defined by legal codes and social conventions (Jochens 1995), and acting in a way deemed inappropriate to one’s sex resulted in significant social disapproval (although in certain cases this may have imbued some individuals with a strange type of power; see Price [2002] on men who practiced sorcery). In a society that promoted hegemonic cultures of masculinity, it should not be surprising to find evidence for the nominal regulation of gender roles or the subordination of both women and marginalized men who failed to live up to masculine ideals (Connell 2005). For men, acting in a way that was considered blauðr brought shame and disgrace. In Kormáks saga (chap. 13; Hollander 1949), for example, Bersi’s wife is able to legitimately divorce him after he receives a wound to the buttocks during combat. Other incidents in the sagas indicate that the charge of “unmanliness” and the threat of divorce were frequently used by women to incite men to undertake acts of violence (Anderson and Swenson 2002; Clover 1993; Jochens 1995).

In Grænlendinga saga (chap. 7), Freydís threatens her husband with divorce if he does not avenge a fictitious assault against her (Kunz 2000a), while in Laxdæla saga (chap. 53), Þorgerðr tells her sons that they would have been better born as daughters in order to shame them into avenging the killing of their brother (Kunz 2000b). The fear of judgment for failing to act in an appropriately masculine manner can even be seen among Guðrún’s adolescent sons in Laxdæla saga (chap. 60; Kunz 2000b). Having been shamed by their mother for indulging too long in children’s pursuits, the youths acknowledge that they are at an age where they will be judged if they were to fail to avenge their father’s death. This suggests that children and adolescents were aware of the need to cultivate and preserve one’s status within hegemonic hierarchies of masculinity from an early age.

For women, acting outside of nominal gendered roles also carried social and legal repercussions. The Icelandic Grágás laws, for example, prescribed that a woman who wore a man’s clothes, cut her hair short, or carried weapons should be sentenced to outlawry (Dennis, Foote, and Perkins 2000:219). Hegemonic hierarchies, however, are not static or monolithic (Connell 2005), and the perpetuation of a “one sex” model of gendered power might have cultivated a peculiar form of social fluidity that allowed some individuals to traverse gender boundaries (Back Danielsson 2007; Clover 1993; Norrman 2000). Just as it was possible for men to increase or lose their status through their words and actions, so too might some women have attempted to achieve social ascendancy by behaving in a way considered hvatr.

The sagas indicate that some women who openly defied social conventions by wearing men’s clothing and carrying weapons, such as “Breeches Auðr” in Laxdæla saga (Kunz 2000b), were not only tolerated but also admired (Bagerius 2001). Other textual sources indicate that women participated in warfare as combatants, and in one case a woman is noted as commanding a viking fleet in Ireland (Bekker 1838–1839; Todd 1867). While such women might well have been a minority within Scandinavian society, these depictions are now potentially supported by a recent study of the human remains from grave 581 at Birka, Sweden. This burial, containing an individual accompanied by a sword, an axe, two spears, archery equipment, a knife, two shields, and two sacrificed horses, was long considered to be an archetypal burial of a male viking warrior. Recently, however, genomic analysis by Hedenstierna-Jonson et al. (2017a) has found that the individual interred within the grave was in fact female.

Until now, the only archaeological evidence for armed women was a corpus of so-called Valkyrie brooches and pendants, known from across the viking world, and these findings therefore provide new impetus for the targeted reanalysis of other purported burials of women accompanied by weapons (see Gardeła 2013b; Pedersen 2014). These include two individuals, both of whom have been osteologically sexed as females, who were buried with weapons and other martial equipment in Hedmark and Nord-Trøndelag, Norway (Hedenstierna-Jonson et al. 2017b). While these burials must be interpreted cautiously, the obvious corollary of these findings is that some women were active participants in the martial cultures of the Viking Age. At present, we can only speculate as to whether these individuals were perceived as “women” or as “men” or whether they perhaps occupied (either permanently or temporarily) some kind of third gender (see Back Danielsson 2007; Norrman 2000), but they nonetheless indicate that gendered boundaries were permeable. While we should not suppose that participation in martial society ubiquitously demanded active involvement in combat, these burials remind us that at least some girls may have been conditioned to adopt the persona or roles of the warrior.”

- Ben Raffield, “Playing Vikings: Militarism, Hegemonic Masculinities, and Childhood Enculturation in Viking Age Scandinavia.”

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Troll Tuesday

"The implication here is that in the beginning Ögmundr was human, but under-went some kind of ritual or at least procedure, referred to as trolling (“trylla”) but never more clearly explained, that seems to have shifted him from one state of being to another.

There is no mention of him dying in the process, but some such transformation seems nevertheless to have taken place since the saga indicates that he cannot be consid-ered a human any longer, and also that he cannot die. Ög-mundr himself later admits that he has become inhuman,“nú em ek eigi síðr andi en maðr” (now I am no less a spirit than a man), and also states “ek væra dauðr ef ek hefði øðlitil þess” (I would be dead if it were in my nature).

Ögmundr is said to be “svartr ok blár” (black and blue), a description used of many Icelandic ghosts, but he is never directly described using the words scholars commonly associate with ghosts in the sagas, although there is mention of “jǫtnar,” “fjandr,” and “troll” (giants, devils, and trolls) inthe different versions of this saga.

Even though Ögmundris referred to as a spirit (“andi”) but not a ghost, there is strong evidence which suggests he should be counted amongst the undead. Something of a medieval Frankenstein creature, having been re-animated like a revenant,it is stated that Ögmundr can no longer die — perhaps precisely because he can no longer be counted among the living.

It is left up to the audience of Örvar-Odds saga to choose how they would like to refer to Ögmundr: as a devil,demon, troll, spirit, or ghost or perhaps all of the above in chorus. Providing evidence of the common indeterminacy of medieval terminology, this example also demonstrates that, when it comes to the paranormal, the more difficult it becomes to classify or name a monster, the greater is the power that it might wield."

- The Troll Inside You: Paranormal Activity in the Medieval North, by Ármann Jakobsson.

Compare:

The Old Man

What difference is there ’twixt trolls and men?

Peer

No difference at all, as it seems to me.

Big trolls would roast you and small trolls would claw you; —

with us it were likewise, if only they dared.

The Old Man

True enough; in that and in more we’re alike.

Yet morning is morning, and even is even,

and there is a difference all the same. —

Now let me tell you wherein it lies:

Out yonder, under the shining vault,

among men the saying goes: “Man, be thyself!”

At home here with us, ’mid the tribe of the trolls,

the saying goes: “Troll, to thyself be — enough!”

The Troll-courtier[to PEER GYNT]

Can you fathom the depth?

Peer

It strikes me as misty.

The Old Man

My son, that “Enough,” that most potent and sundering

word, must be graven upon your escutcheon.

[...]

The Old Man

This same human nature’s a singular thing;

it sticks to people so strangely long.

If it gets a gash in the fight with us,

it heals up at once, though a scar may remain.

My son-in-law, now, is as pliant as any;

he’s willingly thrown off his Christian-man’s garb,

he’s willingly drunk from our chalice of mead,

he’s willingly tied on the tail to his back —

so willing, in short, did we find him in all things,

I thought to myself the old Adam, for certain,

had for good and all been kicked out of doors;

but lo! in two shakes he’s atop again!

Ay ay, my son, we must treat you, I see,

to cure this pestilent human nature.

Peer

What will you do?

The Old Man

In your left eye, first,

I’ll scratch you a bit, till you see awry;

but all that you see will seem fine and brave.

And then I’ll just cut your right window-pane out —

Peer

Are you drunk?

The Old Man[lays a number of sharp instruments on the table]

See, here are the glazier’s tools.

Blinkers you’ll wear, like a raging bull.

Then you’ll recognise that your bride is lovely —

and ne’er will your vision be troubled, as now,

with bell-cows harping and sows that dance.

Peer

This is madman’s talk!

The Oldest Courtier

It’s the Dovre–King speaking;

it’s he that is wise, and it’s you that are crazy!

The Old Man

Just think how much worry and mortification

you’ll thus escape from, year out, year in.

You must remember, your eyes are the fountain

of the bitter and searing lye of tears.

Peer

That’s true; and it says in our sermon-book:

If thine eye offend thee, then pluck it out.

But tell me, when will my sight heal up

into human sight?

The Old Man

Nevermore, my friend.” - PEER GYNT, Henrik Ibsen

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello friend. What do you know about the interactions between Odin and humans? I know all the Storys of the Edda, but it isnt enough for me. Do you have any knowledge?

Óðinn does quite a lot of interacting with humans, I believe more than any other god in Norse mythology. Any answer I give will surely fail to be exhaustive, but here are some examples.

Völsunga saga: You probably are already aware of this, considering that Völsunga saga includes portions adapted from Edda poetry. Óðinn’s interloping in this story is pretty famous and there is too much of it for me to summarize.

Hrólfs saga kraka: Óðinn appears as the old farmer Hrani and offers weapons and armor to King Hrólfr, who considers them to be of terrible quality and refuses to accept them. This turns out to contribute to the heroes’ downfall, and Böðvarr claims that Óðinn is fighting against them in the final battle.

Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks: Óðinn takes the shape of Gestumblindi in response to the latter’s sacrificing to him and asking for help getting the upper hand over Heiðrekr. Óðinn participates in the famous gátur Gestumblinda, a riddle contest that ends with Heiðrekr striking at Óðinn as he turns into a falcon and flies away and Óðinn curses him to be killed by the lowest slave.

Norna-Gests þáttr: Óðinn appears as Hnikarr standing on a rock jetty as the heroes (Gestr and Sigurðr Fáfnisbani’s troops) pass and addresses them in verse. It is implied that he either had been causing the magical storm that caused them to sail near land (previously blamed on the sons of Hundingr) or at least that he stopped it. He gives Sigurðr advice in the ship on the way to battle.

Gautreks saga: Óðinn and Þórr go tit-for-tat alternately bestowing blessings (Óðinn) and curses (Þórr) on Starkaðr.

Hálfs saga ok Hálfsrekka: Óðinn in the form of Höttr arranges to get King Alrekr and Geirhildr married.

Örvar-Odds saga: Óðinn appears as Rauðgrani who helps Örvar-Oddr defeat the fjölkunnugr half-jötunn Ögmundr (or rather, it is said after Rauðgrani drops out of the story that people believed it had really been Óðinn).

Óðinn has a lot of interaction with humans in Saxo Grammaticus’ Gesta Danorum, although some of this is Euhemerized mythology wherein the gods are human. Saxo does occasionally have trouble keeping those apart though.

Here is a paper by Stephen Mitchell about 15th-century Swedish court records involving people allegedly having a relationship with Óðinn.

66 notes

·

View notes