#we need to treat it as a mainstream topic and that includes not only examining the history there

Text

look maybe this is cringe or something but god what i wouldn't give to be a professor who teaches film, literature, and a few courses on the intersection of digital culture around media through a sociological and creative lens

#is fandom studies cringe? maybe so but also with the rise of fandom culture becoming less insular and more mainstream#we need to treat it as a mainstream topic and that includes not only examining the history there#but discussing the inherently messy elements of it#let me write a goddam thesis on migratory slash fandom or what it means to be transformative when it comes to work#fandom is a blessing and it is a curse and i want to teach it#and then ill teach a course on like. fucking horror movies or some shit#queer horror literature and film and the modern era#tbh id also teach a bitching course on the mystery box show - let me teach a course on lost's legacy on modern television or something#just let me get to stand in front of a room and academically analyze shit and read papers and engage with people#yeah ill write my silly little novels on the side but also....

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could you expand a bit on the "death of expertise"? It's something I think about A LOT as an artist, because there are so many problems with people who think it isn't a real job, and the severe undercutting of prices that happens because people think hobbyists and professionals are the same. At the same time, I also really want people to feel free to be able to make art if they want, with no gatekeeping or elitism, and I usually spin myself in circles mentally thinking about it. So.

I have been secretly hoping someone would ask this question, nonny. Bless you. I have a lot (a LOT) of thoughts on this topic, which I will try to keep somewhat concise and presented in a semi-organized fashion, but yes.

I can mostly speak about this in regard to academia, especially the bad, bad, BAD takes in my field (history) that have dominated the news in recent weeks and which constitute most of the recent posts on my blog. (I know, I know, Old Man Yells At Cloud when attempting to educate the internet on actual history, but I gotta do SOMETHING.) But this isn’t a new phenemenon, and is linked to the avalanche of “fake news” that we’ve all heard about and experienced in the last few years, especially in the run-up and then after the election of You Know Who, who has made fake news his personal brand (if not in the way he thinks). It also has to do with the way Americans persistently misunderstand the concept of free speech as “I should be able to say whatever I want and nobody can correct or criticize me,” which ties into the poisonous extreme-libertarian ethos of “I can do what I want with no regard for others and nobody can correct me,” which has seeped its way into the American mainstream and is basically the center of the modern Republican party. (Basically: all for me, all the time, and caring about others is a weak liberal pussy thing to do.)

This, however, is not just an issue of partisan politics, because the left is just as guilty, even if its efforts take a different shape. One of the reason I got so utterly exasperated with strident online leftists, especially around primary season and the hardcore breed of Bernie Bros, is just that they don’t do anything except shout loud and incorrect information on the internet (and then transmogrify that into a twisted ideology of moral purity which makes a sin out of actually voting for a flawed candidate, even if the alternative is Donald Goddamn Trump). I can’t count how many people from both sides of the right/left divide get their political information from like-minded people on social media, and never bother to experience or verify or venture outside their comforting bubbles that will only provide them with “facts” that they already know. Social media has done a lot of good things, sure, but it’s also made it unprecedently easy to just say whatever insane bullshit you want, have it go viral, and then have you treated as an authority on the topic or someone whose voice “has to be included” out of some absurd principle of both-siderism. This is also a tenet of the mainstream corporate media: “both sides” have to be included, to create the illusion of “objectivity,” and to keep the largest number of paying subscribers happy. (Yes, of course this has deep, deep roots in the collapse of late-stage capitalism.) Even if one side is absolutely batshit crazy, the rules of this distorted social contract stipulate that their proposals and their flaws have to be treated as equal with the others, and if you point out that they are batshit crazy, you have to qualify with some criticism of the other side.

This is where you get white people posting “Neo-Nazis and Black Lives Matter are the same!!!1” on facebook. They are a) often racist, let’s be real, and b) have been force-fed a constant narrative where Both Sides Are Equally Bad. Even if one is a historical system of violent oppression that has made a good go at total racial and ethnic genocide and rests on hatred, and the other is the response to not just that but the centuries of systemic and small-scale racism that has been built up every day, the white people of the world insist on treating them as morally equivalent (related to a superior notion that Violence is Always Bad, which.... uh... have you even seen constant and overwhelming state-sponsored violence the West dishes out? But it’s only bad when the other side does it. Especially if those people can be at all labeled “fanatics.”)

I have complained many, many times, and will probably complain many times more, about how hard it is to deconstruct people’s absolutely ingrained ideas of history and the past. History is a very fragile thing; it’s really only equivalent to the length of a human lifespan, and sometimes not even that. It’s what people want to remember and what is convenient for them to remember, which is why we still have some living Holocaust survivors and yet a growing movement of Holocaust denial, among other extremist conspiracy theories (9/11, Sandy Hook, chemtrails, flat-earthing, etc etc). There is likewise no organized effort to teach honest history in Western public schools, not least since the West likes its self-appointed role as guardians of freedom and liberty and democracy in the world and doesn’t really want anyone digging into all that messy slavery and genocide and imperialism and colonialism business. As a result, you have deliberately under- or un-educated citizens, who have had a couple of courses on American/British/etc history in grade school focusing on the greatest-hit reel, and all from an overwhelmingly triumphalist white perspective. You have to like history, from what you get out of it in public school, to want to go on to study it as a career, while knowing that there are few jobs available, universities are cutting or shuttering humanities departments, and you’ll never make much money. There is... not a whole lot of outside incentive there.

I’ve written before about how the humanities are always the first targeted, and the first defunded, and the first to be labeled as “worthless degrees,” because a) they are less valuable to late-stage capitalism and its emphasis on Material Production, and b) they often focus on teaching students the critical thinking skills that critique and challenge that dominant system. There’s a reason that there is a stereotype of artists as social revolutionaries: they have often taken a look around, gone, “Hey, what the hell is this?” and tried to do something about it, because the creative and free-thinking impulse helps to cultivate the tools necessary to question what has become received and dominant wisdom. Of course, that can then be taken too far into the “I’ll create my own reality and reject absolutely everything that doesn’t fit that narrative,” and we end up at something like the current death of expertise.

This year is particularly fertile for these kinds of misinformation efforts: a plague without a vaccine or a known cure, an election year in a turbulently polarized country, race unrest in a deeply racist country spreading to other racist countries around the world and the challenging of a particularly important system (white supremacy), etc etc. People are scared and defensive and reactive, and in that case, they’re especially less motivated to challenge or want to encounter information that scares them. They need their pre-set beliefs to comfort them or provide steadiness in a rocky and uncertain world, and (thanks once again to social media) it’s easy to launch blistering ad hominem attacks on people who disagree with you, who are categorized as a faceless evil mass and who you will never have to meet or negotiate with in real life. This is the environment in which all the world’s distinguished scientists, who have spent decades studying infectious diseases, have to fight for airtime and authority (and often lose) over random conspiracy theorists who make a YouTube video. The public has been trained to see them as “both the same” and then accept which side they like the best, regardless of actual factual or real-world qualifications. They just assume the maniac on YouTube is just as trustworthy as the scientists with PhDs from real universities.

Obviously, academia is racist, elitist, classist, sexist, on and on. Most human institutions are. But training people to see all academics as the enemy is not the answer. You’ve seen the Online Left (tm) also do this constantly, where they attack “the establishment” for never talking about anything, or academics for supposedly erasing and covering up all of non-white history, while apparently never bothering to open a book or familiarize themselves with a single piece of research that actual historians are working on. You may have noticed that historians have been leading the charge against the “don’t erase history!!!1″ defenders of racist monuments, and explaining in stinging detail exactly why this is neither preserving history or being truthful about it. Tumblr likes to confuse the mechanism that has created the history and the people who are studying and analyzing that history, and lump them together as one mass of Evil And Lying To You. Academics are here because we want to critically examine the world and tell you things about it that our nonsense system has required years and years of effort, thousands of dollars in tuition, and other gatekeeping barriers to learn. You can just ask one of us. We’re here, we usually love to talk, and we’re a lot cheaper. I think that’s pretty cool.

As a historian, I have been trained in a certain skill set: finding, reading, analyzing, using, and criticizing primary sources, ditto for secondary sources, academic form and style, technical skills like languages, paleography, presentation, familiarity with the professional mechanisms for reviewing and sharing work (journals, conferences, peer review, etc), and how to assemble this all into an extended piece of work and to use it in conversation with other historians. That means my expertise in history outweighs some rando who rolls up with an unsourced or misleading Twitter thread. If a professor has been handed a carefully crafted essay and then a piece of paper scribbled with crayon, she is not obliged to treat them as essentially the same or having the same critical weight, even if the essay has flaws. One has made an effort to follow the rules of the game, and the other is... well, I did read a few like that when teaching undergraduates. They did not get the same grade.

This also means that my expertise is not universal. I might know something about adjacent subjects that I’ve also studied, like political science or English or whatever, but someone who is a career academic with a degree directly in that field will know more than me. I should listen to them, even if I should retain my independent ability and critical thinking skillset. And I definitely should not be listened to over people whose field of expertise is in a completely different realm. Take the recent rocket launch, for example. I’m guessing that nobody thought some bum who walked in off the street to Kennedy Space Center should be listened to in preference of the actual scientists with degrees and experience at NASA and knowledge of math and orbital mechanics and whatever else you need to get a rocket into orbit. I definitely can’t speak on that and I wouldn’t do it anyway, so it’s frustrating to see it happen with history. Everybody “knows” things about history that inevitably turn out to be wildly wrong, and seem to assume that they can do the same kind of job or state their conclusions with just as much authority. (Nobody seems to listen to the scientists on global warming or coronavirus either, because their information is actively inconvenient for our entrenched way of life and people don’t want to change.) Once again, my point here is not to be a snobbish elitist looking down at The Little People, but to remark that if there’s someone in a field who has, you know, actually studied that subject and is speaking from that place of authority, maybe we can do better than “well, I saw a YouTube video and liked it better, so there.” (Americans hate authority and don’t trust smart people, which is a related problem and goes back far beyond Trump, but there you are.)

As for art: it’s funny how people devalue it constantly until they need it to survive. Ask anyone how they spent their time in lockdown. Did they listen to music? Did they watch movies or TV? Did they read a book? Did they look at photography or pictures? Did they try to learn a skill, like drawing or writing or painting, and realize it was hard? Did they have a preference for the art that was better, more professionally produced, had more awareness of the rules of its craft, and therefore was more enjoyable to consume? If anyone wants to tell anyone that art is worthless, I invite you to challenge them on the spot to go without all of the above items during the (inevitable, at this rate) second coronavirus lockdown. No music. No films. No books. Not even a video or a meme or anything else that has been made for fun, for creativity, or anything outside the basic demands of Compensated Economic Production. It’s then that you’ll discover that, just as with the underpaid essential workers who suffered the most, we know these jobs need to get done. We just still don’t want to pay anyone fairly for doing them, due to our twisted late-capitalist idea of “value.”

Anyway, since this has gotten long enough and I should probably wrap up: as you say, the difference between “professional” and “hobbyist” has been almost completely erased, so that people think the opinion of one is as good as the other, or in your case, that the hobbyist should present their work for free or refuse to be seen as a professional entitled to fair compensation for their skill. That has larger and more insidious effects in a global marketplace of ideas that has been almost entirely reduced to who can say their opinion the loudest to the largest group of people. I don’t know how to solve this problem, but at least I can try to point it out and to avoid being part of it, and to recognize where I need to speak and where I need to shut up. My job, and that of every single white person in America right now, is to shut up and let black people (and Native people, and Latinx people, and Muslim people, and etc...) tell me what it’s really like to live here with that identity. I have obviously done a ton of research on the subject and consider myself reasonably educated, but here’s the thing: my expertise still doesn’t outweigh theirs, no matter what degrees they have or don’t have. I then am required to boost their ideas, views, experiences, and needs, rather than writing them over or erasing them, and to try to explain to people how the roots of these ideas interlock and interact where I can. That is -- hopefully -- putting my history expertise to use in a good way to support what they’re saying, rather than silence it. I try, at any rate, and I am constantly conscious of learning to do better.

I hope that was helpful for you. Thanks for letting me talk about it.

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

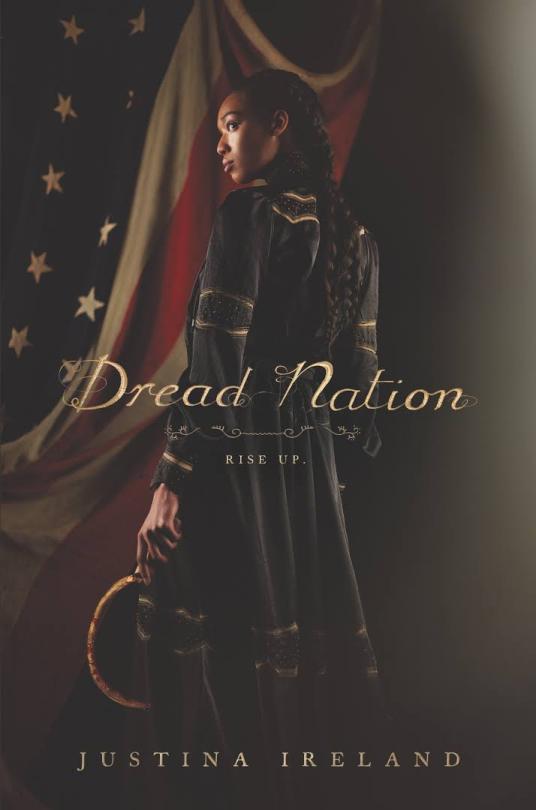

Dread Nation

by Justina Ireland

What it is: a novel where the dead start rising at the battle of Gettysburg. Yes, you read that right. it’s zombies, and the Native and Negro Reeducation Act, which is what ‘ended’ slavery and forced young Black children to go to schools to learn how to fight the undead instead.

Why it’s on this list: Although the identity language isn’t there, considering the era, it is still made explicit that the main character is attracted to boys and girls, and a secondary character admits to being attracted to no one at all. Having a Black leading lady say so, and so matter of fact, makes this even more significant.

Where you can find it: In any bookstore. It just hit the NYT Bestsellers List, it should be absolutely everywhere. The author is also on twitter here, and has a website over here.

Official Synopsis | Goodreads

I have been thinking about this book nonstop since I finished it.

I read it in one sitting. It was breathtaking, it was intense, it was all consuming in the way the best books are.

Whether you are interested in history, zombies, or just a good story, this is a book to pick up.

Now, this is going to be a bit of a different review. Honestly, I feel like I could talk about this book for hours, but I want to take a moment to link to another review, first.

As a white reader and reviewer, I think it’s important to use this platform as a way to highlight the experts. Black women are going to be able to talk about the details of this alternate history novel and how it examines racism, slavery, and Black lives being treated as a commodity in a way that I can’t. And in reading the reviews of Black people reading Dread Nation, it’s made me want to reread the whole book again, because my understanding deepens with each review I read. Alex Brown’s review (warning for general spoilers) is an excellent read, really looking at and comparing some of the things in the book - things that might, to a unknowing reader, feel unrealistically cruel - with real life equivalents. For real, after reading her review I might just pick up the book and read it again tonight.

This book follows Jane, who was sent to a school that is supposed to mold her into an Attendant - a Black girl who is hired by a white woman to protect her, both her virtue and her flesh from the undead who would like to feed on it.

I feel like to even go into the plot much is to spoil it, and since I’ve already linked the synopsis and Alex’s review, I’m just going to jump right in to how this book made me feel.

Y’all, this book is triumphant. I feel like I should say that. Yes, it does not sugarcoat when looking at the intense racism, colourism, and sexism of the time (echoes of which we still feel today - none of these things are things we have left behind). But there is so much hope and strength in this book as well. Was it hard to read at times? Yes, absolutely. Was it also hopeful, did it have me punching the air at times when Jane, the lead, emerges from something victorious? Yes, yes, yes it did.

I’ve been reading mostly queer books. I picked this one up because it was history and zombies. So when the Conversation happened, where Jane talks about being attracted to girls as well as boys, had me doing a doubletake. Especially with how straight forward it was. This wasn’t implication, this was on the page confirmation. Another excellent example of how you can make queerness explicit and on the page, even in worlds and times where the vocabulary we are used to doesn’t exist.

“Is this your way of telling me you fancy women?” Not that I mind. I’ve been distracted by a pretty face every now and again myself...

...My face heats. “Well, Merry was very pretty and she had that amazing right hook.” Merry was also a very good kisser, taught me everything I know, but Katherine doesn’t need to hear about that.

And also Katherine discussing her lack of interest in anyone, and how quick Jane is to say there’s nothing wrong with that.

“But I don’t feel that way about anyone, Jane. I never had and I’m not sure I ever will.”

“Oh, well, there’s nothing wrong with that.”

Just... such cool stuff to find, especially since I wasn’t expecting it. And that makes this story one about two queer Black girls and their relationship growing from frenemies into genuine friends and supporters of each other, which is incredible, because finding that, especially in a speculative fiction book, is basically unheard of.

Jane’s agency in terms of her sexuality in general is something I love in this story. She is very blunt when she comes across someone she finds attractive, and we meet a few boys she is attracted to, and I don’t think I’ve ever read a book that let a lady lead talk so honestly about being attracted to multiple people in a way that didn’t paint it as wrong or at the very least shallow. Jane is a badass female lead, she’s Black, and she is not desexualized or softened/made weaker by being interested in people.That’s really cool and refreshing to see, again made especially so by the fact that this is a historical setting and you could totally explain away if she wasn’t allowed to do this based on the setting.

Jane and Katherine are also allowed the space to be angry, which Black girls aren’t often allowed to do in media and in real life without really racist things being said about it. This is another topic I’d love to see written about by a Black woman, so I’m going to keep an eye out for any awesome reviews or articles talking about this and I’ll come back and edit this with some links when I do find some.

Also, can I just say... This is the only piece of fiction I’ve ever read by a non-Indigenous author that’s mentioned residential schools. The author goes so far as to include additional information and resources on the subject in her author’s note at the end of the book. That was... That was so cool to see. And can I just remind you that this is in a zombie book. Like, everyone else? Do better. Damn.

It’s funny, because so many of the things people say ‘can’t be in historical stories’, because it would be ‘unrealistic’, are included in here. We have amazing Black women leads. We have a really interesting Native American character that I am so hoping we get to see more of in the sequel. This story takes so many people that are dismissed in genre fiction and creates such complex and diverse characters. Including a really rad disabled character (a scientist and potential love interest of Jane?), and a lady named Duchess and her girls, who are sex workers. In most books, these characters would be nameless, maybe used to colour in the background of the world the white leads walk through. But Dread Nation takes great care with all of its characters, especially the ones with identities often dismissed.

Seriously, if I see those kind of arguments, I’m gonna chuck this book at them.

The fact that this is all happening in what is technically a horror book is especially important, because horror as a genre is so often garbage. Mainstream horror so often relies on biases based in sexism, racism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, etc. It’s notorious for this. But horror can be so damn good, when in the hands of marginalized folk. Look at Get Out, for another example. Horror in the hands of the downtrodden or ignored is such a powerful tool, and that is why I say I’m a fan of horror. Because of stuff like this.

On that note, it is a zombie book. There is definitely violence, and some horror elements. So if that’s something you’re sensitive to, be careful. If you want to read it, but fear of character deaths are what’s stopping you, you’re welcome to message me. Sometimes, you need something spoiled in order to enjoy it with less stress, and I do not judge.

Seriously. Go and get this book.

Reading Dread Nation? Let us know what you think! And if you’re looking for more great queer content, reminder that this is Day 10 of 365 queer reviews, one for each day of 2018.

(We’re very behind, but we’re doing our best)

You can find all the reviews here.

#dread nation#justina ireland#bisexual main character#asexual main character#bisexual girl#asexual girl#novel

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dr. Jess O-Reilly Plays 20 Questions with SHA!

Dr. Jess O-Reilly Plays 20 Questions with SHA!

“You’re the ultimate expert in your own sexuality and pleasure.”

The Sexual Health Alliance (SHA) is centered around providing Provocative Dialogue and Radical Collaboration. What would radical collaboration look like for you?

To me, radical collaboration involves sharing my business and working with industry peers who don’t have the same opportunities and privilege as I do. This might involve referring out services to folks who are better qualified to speak on specific issues (e.g. Black sexuality, sex for people with disabilities). It also involves sharing resources, insights and experiences for low/no cost to those in financial need. And at times, it involves sharing the financial profits on specific projects (e.g. collaborating on products like books, video courses and speaking engagements).

As a prominent sexuality professional, you have made a wonderful career as a sex educator. What would you recommend to young educators or therapists wanting to follow in your footsteps?

Ask for help. Don’t be afraid to reach out and ask for the support of your peers and potential mentors. Many of us want to help and if you’re very specific with your request (e.g. Can I pick your brain? is too broad, but Could you look over this introductory paragraph of my book proposal? is more manageable), you’ll probably receive a positive reply.

What book(s) are you reading right now?

I’m rereading Life and Death in Shanghai.

What’s the most important thing you talk about with your clients?

Custom-designing their relationships. There is no one-size-fits-all approach and you can make almost any arrangement work if you’re not burdened by social pressure.

What are the top 3 items on your bucket list?

1. I’d like to build an affordable housing building in my hometown of Toronto and see if we can grow the project to be sustainable; eventually, I’d like to continue to build additional units.

2. I’d like to adopt a child.

3. I want to live to be 100+.

One of our goals is to provide all therapists and healthcare providers with high quality sexuality training because they often receive little to no education in sexual health. What is the most important piece about sex that you want all providers to know? What would you want them to incorporate into their practice?

I’d like every professional to understand that our personal sex and relationship lenses can be completely irrelevant to our clients/patients’ lived experience. This doesn’t mean that our work isn’t shaped by personal experience, but simply that we need to be aware of our own biases and limits. And we need to be more aware of our layers of privilege related to race, gender, income, education, ability, nation of birth, relationship status, social status and professional roles.

What are your top 2 books that have influenced you and why?

Give and Take by Adam Grant. This was an affirming read, as he shares stories and data suggesting that good people do finish first in life and in business.

Our Bodies, Ourselves. I read this many, many years ago when I was in school and it offered such an important perspective on so many different topics. I know they’ve updated it since then and I’ve been meaning to go back to it and read the new version, so thanks for the reminder!

What is bad advice you have heard other people in our field give?

I still hear professionals talk about other cultures and countries as though they’re monoliths that they understand because they worked with clients from a specific culture or they lived in a place for a few months or years. If you’re not a part of a group or culture, elevate the voice of someone from that group instead of speaking for or about them. Nothing about us without us.

Who is your sexual role model?

That’s a great question! I’m not sure I know enough about anyone else’s sex life to call them a role model. Marla Renee Stewart is a general role model — personally and professionally — and I believe she has very happy relationships — sexual and otherwise.

SHA utilizes social media to reach our members as well as to find new sexuality content and research, how do you think social media has influenced our culture’s sexuality?

I’m so thankful for the reach and impact of social media. Putting the power of broadcast into individual hands (instead of allowing it to rest in the hands of a few corporations) has shifted and broadened the content we consume. Accounts like @SexPositiveFamilies, for example, disseminate essential information that mainstream (old) media would never have touched. Research shows that digital consumption and connections can foster digital empathy, galvanize support, create feelings of belonging and build community. Of course, social media is still owned by a few corporations and we don’t have access to how they disseminate our posts, so we have to be mindful that new media also has its limitations.

Our team finds podcasts, youtube and other social media platforms sometimes more educational and useful than traditional models. Do you think social media should have a place in formal training, and if so, how much?

There are accounts that offer high-quality, evidence-based information and there are also powerful accounts that provide misinformation. I think it’s important to analyze media (including social media) in all training and examine messages and biases. Part of all learning processes involves developing and tuning our critical thinking skills and I believe that we can certainly use social media as both a lens and subject.

What made you create your Happily ever after approach to working with couples?

I work primarily with folks who run or own businesses. They’re passionate about their work and they claim that their family is the most important aspect of their lives, but they don’t always act like it. Our Marriage As a Business approach involves applying business practices and acumen to intimate relationships. This might entail hosting board meetings (relationship check-ins), building a support team (e.g. therapists and babysitters), respecting timelines (e.g. showing up to dinner on time), planning ahead (e.g. carving out time weeks, months or even a year in advance).

As a Canadian born, Chinese-Jamaican and Irish by descent person, what has been the most challenging aspect of working in this field?

My gender, appearance and (perceived) ethnicity provide me with both privilege and challenges. As a woman talking about a sensitive topic in the public eye, I draw considerable criticism, harassment and personal attacks — on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, my website contact form and even on LinkedIn. I ignore most of it, but sometimes it does feel like death by a thousand paper cuts. Luckily, I have a lot of support too. And I love life and I’m lucky in so many ways, so I try not to expend my energy on the harassment.

Where is your next dream vacation?

I’m not sure. I have a big birthday coming up in February and I’m deciding between Tuscany, Japan and Jamaica. Help me choose!

What are 2 of the most important things you do everyday?

If I’m home, my partner makes me a decaf macchiato or cortado in a small double-wall glass, which I try to take the time to enjoy without reading, working or scrolling. The glassware and all the details add to my enjoyment; he weighs the beans, grinds them with a beautiful manual grinder, pulls the shots at the right pace and warms the milk to the perfect temperature. It sounds pretentious, but I don’t care, because it’s delicious.

I don’t have many rituals, because I’m on the road most of the time and everything is always changing. But I do make time to enjoy myself wherever I go — even if I only have a few hours in a new city or country, I try to walk to a local third-wave coffee shop or market to get a pulse on local life. If I have time for lunch, I always treat myself to something delicious. Food is my love language and working in the food industry is a part of my family background.

What’s your favorite place you’ve traveling to for you job and why?

It’s hard to pick a favorite place, but Istanbul certainly stands out as a highlight. The people are always so warm and gracious. The rich culture, history and architecture overwhelm me. And the food is so delicious and varied. I hope to return again soon.

What’s the most challenging aspect of being in business with your partner, Brandon? (They are married)

Me. I’m the most challenging aspect. He’s much easier to work with.

We don’t work together full-time. He helps out to co-host the podcast, but he has his own unrelated business that keeps him very busy.

The most challenging aspect relates to my travel schedule. I love travel and I love flying and dealing with the unpredictability of new surroundings, but I do miss being physically together. This was a challenge for several years, but he travels with me far more often now, as he has more flexibility with his business.

What’s your favorite story to tell?

I’m a storyteller. As they say, a story doesn’t have to be true to be good. Ha!

But here’s a true one:

On a flight from Denver to Albuquerque a few years ago, a guy threw up all over me as the plane landed. Instead of just vomiting, he tried to keep it in his cheeks and so the trajectory changed and it sprayed everywhere — all over me and in the hair of the couple in front of us. People were dry heaving all around us and I was just hoping that no one else would vomit. I remember thinking that if one more person vomits, the whole plane is going to become a vomit comet. I don’t know why I picked that story, but it just popped into my head.

If you want something sexuality-related:

One time I was at a sex club and two people high fived on the bed next to us while exclaiming, “Oh yeah. This is so hot! And it’s a great workout, so we can skip the gym tomorrow!”. This was their dirty talk and it got them all riled up, but it killed the vibe for me and some of the others in close proximity.

Another time, as lady who was 7+ months pregnant stopped me and asked if I could help her figure out a good position for DP (double penetration) given her big belly. This was a time when I was reminded that they definitely don’t teach you everything you need to know in school.

Your bio says you like airplane turbulence! Can you tell us more about why you like it?

I just love airplanes — I love flying in them, talking about them, reading about them. And I like the physical thrill of a little turbulence — especially in a bigger plane. I will reroute to fly on a cool plane (e.g. the 787-9) and I hope to train as a pilot someday.

Being trained in sex & disabilities, can you give us some tips on why discussing disability is important?

All sexual health education needs to be inclusive and this includes talking about sex as it relates to race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, relationship arrangement, income, and disability. I facilitated sessions on sex and disability early on in my career and now I’ve learned that I should pass the mic and advocate for paying opportunities for fellow sexologists who have disabilities. There are many qualified folks who simply don’t get the same paid opportunities as I do because of ableism.

When we leave folks with disabilities out of the conversation, we reinforce inaccurate stereotypes and put them at greater risk, as sexual health education produces positive health outcomes regardless of whether or not you have a disability.

What's an important take away from your new book The New Sex Bible?

Do what feels good for you. Don’t worry about what the experts or your friends have to say. You’re the ultimate expert in your own sexuality and pleasure.

About Dr. Jess

Jess O’Reilly began working as a sexuality counsellor in 2001 and she has never looked back! Her PhD studies involved the development of training programs in sex education for teachers and her education and undergraduate degrees focused on equity and sexual diversity.

Her training includes courses in counselling skills, healthy relationships, resolving sexual concerns, sex education, clinical sexology, sexual development, sex and disability, group therapy and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy.

Alongside her academic and television credits, Dr. Jess is also an accomplished author with three best-selling titles. Her latest, The New Sex Bible, has received rave reviews from professionals and clients alike and her first book Hot Sex Tips,Tricks and Licks is in its fourth print! Look for her monthly column in Post City or catch her on Tuesday mornings on Global TV’s The Morning Show, Wednesdays on 102.1 The Edge and Saturdays on PlayboyTV.

Dr. Jess’ work experience includes contracts with school boards, social services agencies, community health organizations and private corporations. A sought-after speaker, her sessions always attract a full-house at conferences and entertainment events alike.

Check out more about Dr. Jess!

Follow Dr. Jess on Twitter & Instagram

Dr. Jess O-Reilly Plays 20 Questions with SHA! published first on https://spanishflyhealth.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

Ayat and Hadith that Prove Islam is a Religion of Peace

Critics of Islam often brand it as a barbaric and brutal religion. Their argument is generally based on a select few ayat (Quaranic verses) and hadith (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad) which seem to promote violence.

There are indeed a number of ayat and hadith which encourage Muslims to turn to combat in certain situations. It is important to remember, however, that much of the Quran was revealed during a time of war. The vast majority of seemingly pro-violence ayat and hadith were revealed to Muhammad PBUH while his followers were being persecuted by those who did not believe his message.

Despite bias interpretations from fringe extremist sects, the Quran encourages Muslims to remain cordial and non-violent in times of peace. Evidence to support Islam's preference for peace can be found in a great many ayat and hadith.

The peaceful ayat and hadith far outnumber those calling for bloodshed. There are so many, in fact, that we could not possibly examine them all in this article. For that reason, we have gathered a few of the most noteworthy here and encourage you to seek out additional examples during your own scripture study. Here are just some of ayat and hadith which prove Islam is a religion of peace,

Ayat Promoting Peace

The Quran is made up of a mammoth 6,236 verses. In the Muslim world, these verses are more formally known as "ayat" (or "ayah" individually). The ayat are spread out over 113 surahs (or chapters) and deal with a variety of topics. Below, you'll find some of the most memorable ayat encouraging peace.

Al-Qasas, Ayah 56

When Islam was in its infancy, the pagan leaders of Mecca viewed Muhammad as a minor annoyance. As his following increased, however, his status was elevated to legitimate public enemy. Those who opposed Islam sought to stop it in its tracks by slaughtering even the most inconsequential Muslim.

When one considers the hardships Muhammad and his followers endured to practice their faith, it should come as no surprise that the Quran stresses the importance of freedom of religion. Despite what jihadi groups may believe, Islam teaches that each person should have the right to practice their religion. This is never stated more clearly than it is in the 56th verse of the 28th Surah, Al-Qasas. It reads as follows:

"Indeed, [O Muhammad], you do not guide whom you like, but Allah guides whom He wills. And He is most knowing of the [rightly] guided." (Quran 28:56)

Al-Baqarah, Ayah 190

The ayat that are often cited as "proof" of the Quran's violent nature rarely call Muslims to violence. In most cases, they merely encourage followers of Muhammad to defend themselves when attacked. So, according to traditional Islamic belief, a Muslim may only resort to violence if it is the sole way they can shake an aggressor. An example of this teaching can be found in Al-Baqarah, the second surah of the Quran. Ayah 190 of Al-Baqarah reads:

"Fight in the way of Allah those who fight you, but do not transgress. Indeed. Allah does not like transgressors." (Quran 2:190)

Al-Baqarah, Ayah 195

A lot of the Quran's peaceful ayat simply advise Muslims to avoid conflict and violence. While they are admirable in their message, they often draw criticism for their failure to encourage behavior which lends itself to the progression of a community.

Of course, as any Muslim knows, it is not enough to merely avoid doing bad deeds. To enter the gates of paradise, a Muslim must also improve the lives of others through their words and acts. This is reflected in numerous ayat throughout the Quran, including Quran 2:195.

In surah Al-Baqarah, just five ayat after advising Muslims to avoid violence whenever possible, the Quran does so again. This time, however, it also encourages readers to perform good deeds. The ayat reads as follows:

"And spend in the way of Allah and do not throw [yourselves] with your [own] hands into destruction [by refraining]. And do good; indeed, Allah loves the doers of good." (Quran 2:195)

Al-Insan, Ayat 8-9

We have all heard about the grizzly videos of jihadi soldiers torturing prisoners of war. Disguising their blood lust as obedience to Allah, members of ISIS and similar extremist groups behead, drown, and even burn their prisoners. Unsurprisingly, their actions are responsible for much of the negative press Islam have received in recent years.

In reality, these jihadi fighters are directly violating the commands of Allah. Although the Quran does permit the keeping of prisoners in a time of war, it states unequivocally that all prisoners of war must be treated justly. An example of this can be found in surah Al-Insan, ayat 8 to 9.

"And they offer food to the needy, the orphan and the captive. [Saying] "We feed you for the sake of Allah alone; we wish for neither reward nor gratitude from you.'" (Quran 76:8-9)

Hadith Promoting Peace

In Islam, the Quran is complimented by hadith. Hadith are accounts of sayings and actions of the Prophet Muhammad. Just like the Quran, the hadith come out strongly in favor of peace and kindness. Some of the most popular peace-promoting hadith are outlined below.

Entertain Your Guests And Keep Peace With Your Neighbors

Arabs are famous for their hospitality. If you have traveled to the Middle East - or even paid a visit to your local mosque - you likely have first-hand experience of that fact.

Arabs prided themselves on their hospitality even in the pre-Islamic age. Once Muhammad gained a following, however, showing kindness to your neighbors and visitors became even more important. In the eight book of Sahih Bukhari, you'll find one of many sayings of Muhammad on the importance of being a good host.

"Anyone who believes in Allah and the Day of Judgement should not harm his neighbor. Anyone who believes in Allah and the Day of Judgement should entertain his guests generously and should say what is good, or keep quiet." (Sahih Bukhari)

You Cannot Hate And Be A Muslim

Critics of Islam often point towards its opposition to same-sex marriage as evidence of its supposed hateful nature. While mainstream Islam teaches that same-sex relations go against the commands of Allah, it does not call on Muslims to hate members of the LGBTQ community. In fact, the Prophet Muhammad clearly stated that anybody who hates another person cannot be a Muslim, let alone enter Paradise.

Islam is very much about loving your neighbor, regardless of what they do or who they love. Evidence of this can be found in a passage of Sahih Bukhari, which reads:

"You will not enter Paradise until you believe and you will not believe until you love each other. Shall I show you something that, if you did, you would love each other? Spread peace among yourselves." (Sahih Bukhari)

Arguments Are Not Constructive

While Muhammad was known to enjoy a hearty discussion about theology, he made sure his followers understood the difference between a debate and an argument. While a debate can contribute to the development of a community, an argument can have the exact opposite effect. An argument would have been particularly destructive in the early days of Islam, when Muhammad needed Muslims to stand together against the non-believers.

According to Sahih Muslim, Muhammad warned his followers that consistent disagreements among them would prevent the expansion of Islam, saying:

"Verily, those before you were ruined by their differences over the Book". (Sahih Muslim)

Avoid Selfish Acts

As a child, Muhammad was fascinated by fallen civilizations, such as the Biblical lands of Sodom and Gumorrah. As exhibited in both the previous and following hadith, the Prophet was ever mindful of these tales even in adulthood. He often reminded his followers of the mistakes made by the people of these once-great civilizations, which had ultimately led to their destruction. If Muslims were not careful, Muhammad warned, a similar faith would befall them.

Selfishness and miserliness were particularly ripe in 7th-century Arabia. Muhammad went through great efforts to ensure such issues did not infect his community of believers. In Riyad as-Salihin, he states:

"Avoid cruelty and injustice, and guard yourselves against miserliness, for this has ruined nations who lived before you." (Riyad-us-Salihin)

We Should Actively Seek To End ConflictEnter heading here...

When our friends are having an argument, it can be tempting to just sit it out and let them sort things out for themselves. This is understandable. However, Muhammad advised against such indifference.

According to the Prophet, if two warring people are left to argue, it is unlikely that a mutually-beneficial resolution will be reached. Those involved in the dispute will be too blinded by emotion to conceive of a solution that will please both parties. For that reason, Muhammad encouraged his followers to act as a mediator in disputes among their family and friends, saying:

"Shall I inform you of something that holds a higher status than fasting, praying, and giving charity? Making peace between people, for verily sowing dissension between people is indeed calamitous." (Kenzul Ummal)

0 notes

Text

So apparently I wanna talk about Secret Empire

[Shows up a month late with Pete’s Coffee]

There’ve already been a lot of well-written thinkpieces and entries about this comic, about Nick Spencer, about it all. But I wanted to maybe throw my two-cents into the pile because, to this day, I think most people are still a little confused about where the outrage is coming from, what exactly is making people uncomfortable, and why it all just keeps snowballing on itself.

And honestly I don’t blame those people; this whole situation is kinda hard to parse. You think it’d be easy to understand why “They turned Captain America into a Nazi” makes people upset, but the thing about Secret Empire is that it honestly does a good pretty job of covering its own ass, of not doing anything overtly offensive, of leaving in all the loopholes and technicalities and escape clauses to its own premise. “It’s going to be undone in the end.” “He’s not actually a Nazi, he’s just brainwashed (even though the story goes on and on for pages about how he’s actually not brainwashed and is in fact a Nazi).” “We’re treating Nazis as bad guys, not glorifying them.” “And they’re not really Nazis, they’re Hydra, it’s totally different.” “We’re tackling topical issues! Aren’t we brave! And daring!”

And that’s the kind of stuff I wanna try to cut through here, but it’s gonna require...well...yet another thinkpiece. Sorry about that.

So I think that Tumblr has covered much of this pretty well, but something to be aware of is that, for a while now, genre media has had A) really iffy mindsets about Jewish issues and B) a sort of casual flirtation with "cool Nazis" as some edgy cool thing to hype and market. It’s not glorifying Nazis exactly, but it’s using that kind of imagery and ideology as tools to sell your books and movies and TV. And when I say "genre media" has been doing these things, I actually am specifically referring to Marvel comics and studios for a notable chunk of these instances.

When you combine those instances with the state of the world where Nazism has been regaining traction with the 'chans and redditors and within the White House itself, with Holocaust denialism and Jewish defamation being a regular fixture of the news cycle...it's no wonder that members of the Jewish community and blogosphere has been feeling disenfranchised by a lot of the old entities and structures that had seemed like they should be able to count on as a matter of course. That includes the government, that includes our fellow citizens, and it also includes the media.

(sidebar, I am not Jewish, I just enjoy their comics!)

That's what readers mean when they say this feels like the worst sort of climate for a story that reveals and is marketed on the premise that Captain America was secretly a Nazi all along. It's not that people don't want the current political climate to be examined and lampshaded in media, it's that this specific method of examination comes across scarily comparable to all the antisemitic media and rhetoric that's been released throughout the years which has led us to this current political climate in the first place. It's the media-slash-rhetoric where Jewish (and other) characters have their origins retconned and whitewashed into homogeneity, where pontificating supervillains are just misunderstood revolutionaries who might have a point or something, where fascist police-states are shock value tropes to engender hype and interest amongst audiences.

Spencer's argument is that this story, which depicts a universe where the fascists win, is intended to incite discourse and criticism against such a universe. Hydra are still clearly the bad guys of the story, we're obviously intended to want to see them lose, of course they're going to lose by the end. But the way that the story has been constructed up to this point exhibits a lot of the same signatures of various antisemitic story beats we've had throughout the years. Captain America being retconned from a stalwart defender of Jewish people into being a Nazi agent, for instance, evokes Wanda and Pietro Maximoff being changed from prominent Jewish-Romani superheroes into whitewashed Hydra recruits on the big screen...and there was certainly no secret message or hidden allegory behind the Maximoffs' change; all it was was offensive and tone-deaf and that was it.

For another instance, Nazi Steve delivering issues-long sermons about how the heroes of this world have gotten complacent and misguided and that the world needs someone willing to make the tough choices, to do what it takes to protect it, is reminiscent of Tony Stark and Carol Danvers making fascism-apologia for months on end throughout the two Civil War event comics, like, hey maybe these guys playing the hardball roles have a point right? Hey aren't we so hardcore and edgy for tackling the hardcore and edgy topics? CHOOSE YOUR SIDE!...and in the end this fascism-apologia is just played completely straight, no hidden critique, no last-minute swerve, just Marvel turning its heroes into borderline supervillains and that was the end of the story. But hey, this story here and now will be totally different from that! Becuuuz...for some reason.

To be direct about his: This isn’t our first rodeo, Marvel Comics. Let’s not pretend that Marvel...and DC, let’s be fair...haven't in fact made a lot of legitimately terrible in-canon offensive character assassinations of iconic characters and that it's not that unreasonable to be afraid of it happening again at any given point. Let’s not pretend that Marvel hasn’t done a lot of those things for the specific reason of angering readers and then feeding off of that anger and attention.

At the very least, there's been this weird romanticizing of Hydra Cap from Spencer in what I've read of these books so far; it doesn’t exactly refute the premise that Steve being Hydra is bad, but Steve is still the protagonist of these books no matter how brainwashed he is, so these issues seem to have come across less like "Our heroes have to prevail against this nefarious schemer and his nefarious schemes!" and more like "Watch in wonder as this shadowy agent prevails against all the clueless establishment and does badass things throughout his mission!" It falls into the "cool Nazi" trend where it's like, of course we're consciously aware that he's the bad guy here, but isn't he so edgy and hardcore and badass anyway? I haven't read as many issues of Hydra Cap as Spencer would probably like so, I dunno, let me know if I'm way off here.

So, to summarize...well, not summarize exactly, but to organize these points, lets’ do a list. Everyone likes lists, right?

1) Showing the "bad guys" losing in, like, probably the very last issue of this year long storyline (which also included the main Captain America book which led up to the actual event) doesn't suddenly omit all those issues where the "bad guys" were shown being edgy and hardcore and badass and smart and powerful and pulling one over on all those dense clueless liberal "good guys," except in this case the bad guys are people who directly abetted in the Holocaust and not the guys who stole forty cakes.

2) This is during a time in the world where antisemitic rhetoric is seeing a startling resurgence -- or maybe just coming back into the light again after hiding away for a bit -- and Holocaust denialism, vandalism of public Jewish spaces, and outright physical violence being more and more common occurrences.

3) Readers in general have been consistently burned by Marvel's consistently tone-deaf depictions of moral or social narratives throughout their events (Civil War: police states are great!) (Civil War II: police states are great!) (IvX: Cyclops is goddamn HITLER for some reason). Jewish readers, in particular, have good reason to not to trust Marvel to be respectful and tactful of their issues. Any such complaints or concerns have been responded to with derision or misunderstanding on Spencer's part, which only makes everyone angrier and more wary.

4) Indeed, Marvel and Spencer's go-to insistence that Hydra are totally not Nazis at all and you're just being nitpicky if you say they're Nazis just further makes them come across as tone-deaf and bullish on the matter, on top of (probably unknowingly, if I’m feeling generous) mirroring the talking points of actual real life Nazis, who've been trying to rebrand themselves as something different for years in order to come across more fluffy and palatable to mainstream sensibilities.

5) I mean there's also the fact that Hydra is -- as currently depicted in this very event by the very writer who keeps saying they're not Nazis on Twitter -- a completely fascistic political regime that stifles free thought and rewrites history through fear, violence, and propaganda and oh hey did someone mention concentration camps? ‘Cuz there are concentration camps in this book. Hydra is functionally indistinguishable from Nazis in this actual book. This is not a book about Captain America being brainwashed by Saturnians to plant death lasers on the moon, this is a book about Captain America being a Nazi and doing things associated with Nazis in absolutely every respect. But sure let’s get comic shop owners to dress up like them and stuff

6) "I don’t care if this gets undone next year, next month, next week. I know it’s clickbait disguised as storytelling. I am not angry because omg how dare you ruin Steve Rogers forever. I am angry because how dare you use eleven million deaths as clickbait." Copypasted directly, because how can you get clearer than that.

7) Spencer's work with Sam Wilson Captain America, which generally turns him into a centrist apologist at best who couldn't believe that he himself was ever that much of an annoying liberal activist or something and occasionally fights literal "social justice warriors" on college campuses throwing bombs and internet slang, isn’t a particularly encouraging thing to have hanging on the back of your mind while reading this story about how Steve Rogers was actually a Nazi all along.

8) In a world where an X-Men artist is literally sneaking secret antisemitic propaganda into books that are supposed to celebrate diversity and civil activism, can you really blame people for being antsy about a comic book that is making members of Stormfront cream themselves by revealing that Steve Rogers was a secret Nazi all along?

So yeah, I dunno if I have any great point to make with any of this. I just felt like collating all the outrage and shedding a little light on how the situation comes across to me. Secret Empire isn’t exactly the sort of clear-cut idiocy where, y’know, some dense writer fridged yet another female character or replaced yet another hero of color with his white predecessor from forty years ago. Its problems are a bit more intricate, which means the blowback is a bit more intricate as well.

#Captain America#Secret Empire#Nick Spencer#Marvel Comics#Marvel#Steve Rogers#Hydra#Nazis#comics#Overthinking

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 Things TV Can Teach Gaming about Queer Storylines

Even though television had a head start on the first generation of video games, these two art forms have found themselves on an even playing field within the last decade. Graphically, games may have evolved a bit slower over the decades but, that didn’t stop them from leaving as much of a cultural mark on the world as popular TV shows. Motion capture technology has allowed games the ability to deliver cinematic experiences in a far more immersive setting. One thing that is truly holding back major video games from exploring a range of gender and sexual identity, is the production process. In many cases, big name game developers can take two to four years to produce one title, and that’s if they’re lucky. Television shows take far less time to produce and thus, have done more to advance stories of the queer community by simply providing more of them over time. This is not to say that games have not attempted to include queer characters at all. In fact, indie game developers have been leading the charge in intersectional diversity for years. The only time queer characters come close to being the sole lead of a multi-platform gaming franchise is if it’s a massive RPG and you get to create your own avatar. While these kinds of games are enjoyable, they do not provide the same definite representation that a game with a set protagonist does. If we look back at the Tomb Raider reboot we can see a clear example of an opportunity for representation that was missed. In a 2013 interview with Kill Screen, Rihanna Prachet stated that she wished she could make Lara Croft gay, and went on to make very clear points about representation beyond including more female characters in games: “Whenever anybody talks about a need for more female protagonists I say: “There’s a need for more female protagonists, but there’s a need for characters of different ethnicities, ages, sexual orientation, ability, et cetera.” We are very narrow when it comes to our characters.” This interview gave many fans, including myself, hope that the reboot would establish Lara Croft as queer, especially with Lara spending the first game rescuing her best friend Sam, whom she clearly had a deep connection with. Since this interview, we’ve had one more installment of the reboot that side stepped Lara’s sexuality entirely. This didn’t make the game any less enjoyable but the complete disconnect from the events of the first game was not unnoticed by fans. Not only was Sam nowhere to be found in game, her Wiki page stated that she was in a mental ward. Now with Pratchet leaving the post of lead writer for the third installment there is not much hope left that we may see a queer Lara Croft anytime soon. It’s my belief that if major game developers studied three key factors of how queer storylines have been handled well (and poorly) on TV, they may be more willing to consider writing queer protagonists. Maybe even some that fall under that “et cetera” category Pratchet was talking about nearly four years ago. I find that most forms of mainstream entertainment relegate any serious exploration of gender identity to the fringes. Independent filmmakers, indie games devs, premium or non-cable TV networks. Billions, a Showtime original series, is introducing the first major genderqueer supporting character in a drama series. The character’s name is Taylor, and will be played by Asia Kate Dillon, an androgynous actor that identifies with they/them pronouns. In 2016, the now canceled MTV show, Faking It, featured many queer characters within one plot. It also had the first intersex character in a supporting role on a TV show. There are far more examples to pull from in television these days, with many shows including at least one queer character and sometimes even multiple queer storylines and once. It seems like an odd thing to dwell on because nobody ever says “look at all these hetero people in my plotline” but if we really think about the number of mainstream shows or movies in recent years with more than one or two queer protagonists who aren’t in a relationship with each other, it’s not as common. A current instance of this is Orange is the New Black. While not without its faults, there are a range of queer identities throughout the show. This does not make it exempt from failing its audience by killing off queer characters in misguided ways or failing to uphold a character’s sexual identity, however. Piper, the main character of the show, is clearly established as a bisexual woman through her various romances and yet, is never referred to directly as a bisexual. She is often referred to as a “former lesbian” “dyke” and so on, but she never corrects anyone. Oddly enough, the best onscreen conversation about bisexuality didn’t happen in a show like this, it happened on a now canceled show that aired on ABC family, Chasing Life. In episode seven of the second season of Chasing Life, Brenna Carver attends an LGBTQ club meeting and her bisexuality is brought up. The conversation that ensues showcases many of the most common misconceptions that bisexuals face. The conversation Brenna has reminded me of the conversation Krem in Dragon Age Inquisition has with the Inquisitor if they choose to have drinks with Iron Bull and his crew. The primary difference being that once the conversation is over in Dragon Age Inquisition, Krem turns back into NPC set dressing and in Chasing Life, Brenna is still a full-fledged member of the plot. Krem’s presence in Inquisition was incredibly important, but the impact he would have had if he had been a romanceable party member would have been astounding. Many people probably wouldn’t scoff at a trans male character like Krem at the helm of a major video game plot. Adding queer characters to a story is as important as actually utilizing them within it. It would also be ideal to include more than one queer character, to increase the likelihood that a queer character might end up alive at the resolution of a story. They often end up in shows or movies where “anyone can die” and due to the low number of queer people present, usually take the entirety of the stories queer representation with them if they get killed or written off. When this happens, it creates a bitter fan base and usually leads them to stop watching a show or seeing a filmmaker’s next 90-minute dramedy. It’s simple: don’t write queer storylines like an episode of Highlander. There can be more than one. Anyone who has spent any amount of time in the closet knows the depths to which one will claw at any scrap of positive representation they can identify with, even if that means reading into things only they can see. Often we are forced to create our own worlds within the restrictions put forth by the storytellers. Games like Final Fantasy XIII, while widely regarded as the most unfavorable game in the franchise, is also considered being the queerest one due to subtext. This is the result of the seemingly over-affectionate nature of characters Vanille and Fang. For those who didn’t pay too much attention to the development of the game, like me, you probably were unaware that Fang was first developed as a male character. This could explain why the relationship between Vanille and Fang reads as romantic. Intentional or not, if Fang had remained a male character, it’s highly likely that we wouldn’t be having debates over whether or not her and Vanille were a couple. We can only imagine the impact that game could have had if the relationship between them had been at the forefront. This “close female friendship” phenomenon is a very common form of subtext. A TV show notorious for subtext of this kind is Rizzoli and Isles. Ending in 2016 after seven seasons, plenty of beards and a hefty amount of queerbaiting, our heroines found themselves relaxing in a bed planning a trip to Paris together. Completely normal non-romantic behavior right? Let’s put things into perspective here. Bones, a show that has been on air since 2005, featured almost the same dynamic, a cop and a medical examiner working together with a rag tag group of scientists and detectives. The difference being that the heterosexual relationship between the two lead characters is acknowledged and fully actualized with them going on to marry each other in season 9 and even have children. Bones got to marry her quippy lovable detective friend, while Jane Rizzoli and Maura Isles were constantly being bounced around to romantic storylines severely lacking in chemistry in order to deflect from the fact that they were perfect for each other. Had the relationship been made explicit it would have been the first major network detective show of its kind to put a queer female romance at the forefront. The resolution of the hero’s journey often relies on martyrdom or some other form of doom and gloom to wrap up a story. This is never more true than for the queer individual. If it wasn’t, then the Bury Your Gays Trope wouldn’t exist. It is very real, and self-explanatory but if you truly don’t know what it is, you’re one Google search away from being fully briefed on the topic. I’m one of those people who love a great ambiguous ending or twilight zone twist at the end of a story, but when it comes to queer characters, I would take riding off into the sunset over death any day. Games like The Last of Us provide us with Ellie, a queer supporting character who ultimately rises to equal footing with her male counterpart Joel but, her story is still rooted in tragedy. Many responses from showrunners have been that death is just part of the show and if we want to be treated like everyone else we should except it. Sure, that might make sense for Game of Thrones but not for shows like Last Tango in Halifax, which grew in popularity between 2013 and 2015, due to its inclusion of a genuine late-in-life coming out story and romance between two women. In the finale of the third season, Caroline marries her pregnant live-in girlfriend Kate, only to be widowed within 24 hours. Kate gets into a car accident off screen and dies, and a little piece of every fan rooting for them dies too. These types of “sudden death” storylines occur across television and film far too often. At a certain point, it stops being about just one character. Each new death rubs the salt deeper into an already open wound, a wound that constantly throbs with anger. An anger rooted in the fact that queer people have been around as long as there have been stories to tell and yet, we still live in a world that consistently fails at replicating our experiences. It’s 2017, and the only shows where there are well established queer female romances that will most likely not end with one of them dead are featured in shows like Wynonna Earp and Supergirl. Everyone involved in the creation of these two shows including the actors, has openly stated that they are invested in the characters that make up their queer representation, treating them as they would a heterosexual couple. SyFy even created an entire section of the Wynonna Earp website dedicated to the relationship between Waverly Earp and Nicole Haught. Games have the unique ability to sidestep the restraints of having to seek out crowd drawing actors or shooting in expensive locations because they can literally mold characters out of polygons and build their worlds out of code. This uniquely positions them to create something we have never seen before, someone we’ve never seen before. As Rhianna Pratchet put it: “Exploring something about what it means to be a gay character, bisexual character, transgender character, in games, that would create some interesting stories.” I couldn’t agree more http://dlvr.it/NKvGm1

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I May Destroy You: a Bold Show Only a Survivor Could Write

https://ift.tt/3h2mtbs

Warning: contains spoilers for the I May Destroy You finale

Michaela Coel’s I May Destroy You is a tour de force creation of laser-focused storytelling. A creator working at the current height (but clearly not yet the apex) of her power, Coel’s take on trauma and consent is the kind of prestige exploration that only a survivor could write. The series starts with Coel’s pitch-perfect take on the nuts and bolts of trauma, from the intrusive thoughts and sarcasm toward art therapy to the ringing we hear when main character Arabella is triggered to Arabella downplaying her own trauma by comparing it to various global tragedies. But Coel goes beyond that and puts every kind of consent under the microscope, pushing the audience to look at the aspects of rape culture that make us the most queasy, even if – especially if – they’re inside ourselves.

With Arabella’s drug-induced blackout in the first episode, I May Destroy You sidesteps the depiction we’re most used to seeing of sexual assault – detailed, graphic imagery of “what happened” – in favor of a more guttural and nuanced portrait of the thing that lasts: surviving sexual assault. As a result, the show has so much more to say than the usual fare, staying with Arabella and her friends for at least a year to see the changes great and small after the assault, and to examine consent across their lives from a number of different angles. Only someone who’s spent so much time swimming in this topic could write it so intensely and accurately.

Usually, when rape and sexual assault are depicted in mainstream storytelling, they are used as a storytelling device — a time-saving shorthand to further the plot for a male character who has a relationship with the victim, to show how deeply evil the perpetrator is, or perhaps to make the victim seem more sympathetic or to provide her with sufficient motivation to be an active protagonist in her own story. (Why else would LadyCops exist?) These tropes are discussed in heteronormative terms because most sexual violence on screen ignores the reality that men are survivors too, and that LGBTQ people are disproportionately affected, as are, for that matter, BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color).

Even when stories are primarily about sexual violence, the narratives tend to follow the same repetitive beats. The rape revenge movie, the Good Survivor™ who self-actualizes their way to justice—and also love! It’s lazy storytelling to retread the same arcs, but with the exception of a wonderful few, like Sweet/Vicious, The Assistant, The Magicians (which righted itself after a triggering start) and hopefully the forthcoming Promising Young Woman and Run, Sweetheart Run, it’s near-universal.

Enter I May Destroy You.

Drawing from a personal experience of sexual assault, Michaela Coel’s 12-episode show is a fictional depiction of Arabella, a millennial writer living in London who was drugged and raped while out for a drink one night when procrastinating on a deadline. Like many survivors, it takes Arabella some time to accept the label the police investigators assign to what happened to her, though they generally treat her well, certainly better than we’d expect here in the States. Don’t get too comfortable, though – for as well as Arabella is treated, her friend Kwame, a queer Black man, experiences something entirely different when he goes to report a rape.

From the beginning, it’s clear the investigator doesn’t understand sex between men and isn’t interested in taking Kwame’s information. He is afforded no privacy while the investigator takes his statement, while a door with a sign saying it must be closed is clearly left open. Kwame isn’t offered support or understanding – instead there’s a sense of judgment surrounding the circumstances, since he used a hookup app. The investigator brushes off the possibility of taking a DNA sample since, they say it wouldn’t prove anything since they had consensual sex, ignoring that at least then they would know it was the correct person. The entire interview is far too casual, with the investigator asking if he was penetrated or not almost as an afterthought, on their way out the door. We don’t have to imagine what an interview with a woman reporting sexual assault would look like, because we’ve just seen it, a few episodes ago. Even between two young Black Londoners with immigrant parents, there’s a hierarchy of privilege and treatment.

Kwame internalizes his experience and withdraws from the world. It takes his friends a long time to realize something is the matter, in part due to concern over Arabella. When they do, Arabella isn’t supportive and doesn’t equate their experiences, even going so far as to accuse Kwame of manipulating or somehow violating the consent of a woman he slept with by not disclosing his sexuality, as though anyone is entitled to that information in the first place. (Kwame primarily sleeps with men but patiently explains that it’s a spectrum and that after being raped, sleeping with men isn’t safe for him, he’s interested in sleeping with women, and he’d like to explore that.) For her part, the white woman Kwame slept with seemed all too eager to fetishize a Black man and then sing the n-word and use the f-word. He called her out on the latter, she became indignant, and she weaponized the language of consent and rape culture to turn the conversation off of her use of slurs and onto him, calling him cancelled and a predator. In her words, “I guess anything that you may have found offensive you wouldn’t have heard if you hadn’t have come into my house under false pretenses,” and I truly hope she warmed up before that stretch.

Read more

TV

I May Destroy You Review: Fresh, Frank, Fluent Drama

By Louisa Mellor

TV

Unbelievable review: an insightful masterpiece from Netflix

By Delia Harrington

The fact of being a survivor alone doesn’t make a person an expert on all things consent and sexual violence. Some survivors choose to go deep on the research, become a certified rape crisis counselor, earn their Master of Social Work degree, or otherwise advocate for survivors in a technical capacity above and beyond their personal experience. But many do not, and it takes years for those who do. Survivors are not infallible; some of the most damaging, victim-blaming things I’ve heard have come from survivors in the early days of denial or crisis, including myself. The awful things we’ve said are usually more about the internalized shame and doubt we’re feeling about our own story than anyone else.

In Arabella’s case, becoming a warrior-survivor makes her feel strong and safe. Her and Terry’s limited understanding of sexuality causes them to be confused by a gay man wanting to have sex with a woman at all, and she gets hung up on that rather than seeing kinship with Kwame and understanding that sex with men is a safety issue for him at the time. Instead, she sees kinship with the racist, sexist white woman Kwame had the misfortune of hooking up with. At this moment in time, Arabella is more comfortable placing Kwame in a box where all men are perpetrators, and any information not shared is manipulation, rather than viewing him as a fellow survivor.

It’s completely understandable. It’s sadly not all that rare. And it’s completely unfair to Kwame. It’s also the kind of messy dynamic most people would not dare to write, let alone lay at the feet of a lead character who’s a survivor of sexual assault. But there’s more humanity in Coel’s take on survivors as fumbling, imperfect, traumatized beings than some sort of beatified victim persona or the ruined/broken/fallen woman trope. Survivors aren’t perfect or magic; we’re people healing from trauma. And for a decent part of the series, Arabella, like so many of us, is pretending she either has nothing to heal from or that healing isn’t an active pursuit. Wouldn’t it be weirder if we were just completely fine?

Coel captures the difficult phenomenon of social media as a public survivor. The push-pull of receiving much-needed support from unseen online followers, while fending off disturbing efforts from trolls and an inner urge to lean too hard on strangers. Social justice can make a survivor feel powerful, and online activism is the most readily accessible for most survivors. At any time of the day or night, you can send off a tweet or post and hear back from a chorus of support – or not. But like any coping mechanism, it helps until it doesn’t.