#this is what doctors who have hypochondriac patients like myself probably feel like

Text

LOVE working in ops and having to troubleshoot dev's issues that they dont know how to describe and is also their fault

#i get it not everybody knows docker#but i went through a web dev bootcamp that didnt even cover docker and somehow i know enough about docker soooooooooo#i feel like if youre developing on certain platforms. you have a responsibility to know what youre setting up. before pointing fingers#and learn how to ask proper questions!!!! 2 hours of digging couldve been 10 mins if you point at the thing thats broken#dont assume you know whats wrong (something we did). just. describe the issue first#this is what doctors who have hypochondriac patients like myself probably feel like#at least thats not blaming the doctor as much as it is just panicking tho#hate it when devs are like. WELL OBVIOUSLY YOU CHANGED SOMETHING. no we didnt. you fucked up#somebody shut me up#WORK RANTS WITH BIANX#thats a tag now

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tw: mentions of self-deleting, brief r-word mention, self harm mention

‼️‼️while I'm depressed, I am NOT going to self-delete. I am in treatment.‼️‼️

Also this format may be weird, I'm on my phone

Post: I need to rant/vent. I did have some thoughts of self delete. I'm just so tired. Tired of having to act happy and being "better" because my ex-fiance doesn't fucking get that being depressed isn't easy. especially after I have told him before what was bothering and was causing it, and he still continues to it. I'm tired of being his "mother/maid/therapist/doctor". I'm tired of having to be in the same room and can't even do what I want without him bothering me or wanting to watch whatever he wants. He has told me multiple times that doesn't really want to watch what I want because it "always has death in it". I have stopped playing games I loved because of him. He got into a couple but bitches about them. "Why did they do this?" "This is so stupid" "the creators are fucking r****ds" "this controls are fuckinf stupid" He is more CoD/1st person shooting gaming, I'm more into rpgs. I'm so tired of it. I can't even watch anything I want because he'll turn his phone on and play really loud music or shows. At least have the fucking decency to put headphones in.

And his fucking backhanded compliments. I know I have body image issues. But he has made it worse. I cut my hair recently because I was trying not to harm myself and cuz men kept touching me and my hair. He said i looked like a Karen. Then got made cuz I didn't laught at his "joke".

Hell I'm getting sick again cuz of him. he won't quit smoking in my van and he keeps turning the light on when I'm trying to sleep. He'll play his phone real loud or call his family or friends then. It's like dude after 10:30pm put your damn headphones in and don't fucking put your phone on speaker! And I'm not telling him any of my symptoms because he is such a fucking hypochondriac. One time we got into an argument. he said he was sick and agreed that he had what I had cuz. I told him that was impossible. He said it couldn't be and I probably plbrought something home (I work in a hospital but I don't work around patients). I told him it was impossible and I didn't get him sick because I'm having my period. He tried to play it off but I was done after that. I was done when he didn't want me in the bedroom because I got a really bad virus or something. But then when I was feeling just marginally better, I had to take care of him because he wasn't feeling good.

I'm tired of him telling his friends and family about my childhood trauma. "Well (they) needed to know" I didn't fucking give you permission to tell anyone!!!!! That was to be kept between the two of us!

And I'm tired of being touched. I want to claw my skin off when someone touches me now. (Yes I'm getting treatment for that too) and this guy at work, who I have told multiple times and in front of other coworkers, I don't want to be touched. Keeps touching my hair "hold still. You have something in your hair." Like dude I don't fucking care! I grew up in the hood and homeless. Something in my hair isn't going to bother me, quit fucking touching me! If he does it today, I'm going to fucking punch him. I warned him over and over again.

I just want to be left alone. I want to be me. I want to do things I enjoy. I wonder when I'll get that chance again.

0 notes

Text

A rambly post about ADHD and my BPD diagnosis

I was evalued for Borderline Personality Disorder twice, despite being pretty sure I didn’t have it myself. The first time I was actually diagnosed with BPD. I didn’t know that much about it, so I just accepted it. Then I started looking a bit more into it, reading about other people’s experience with BPD and started to relate less and less to them. Sure, I had some of the symptoms that former the diagnostic criteria, but my experience of life was so much different than that of people who had BPD.

About a year later, I was - once again - hospitalized for severe depression and suicidal ideation. I told the psychiatrist at the hospital that I was officialy diagnosed with Borderline, but that I didn’t think I actually had it. She thought I probably had it anyways, so she ordered another diagnostic evaluation. This time, I was diagnosed with a Borderline Personality Accentuation, which isn’t a proper diagnosis, but it means that you have symptoms similar to a person with BPD, just less severe. I could live with that - I knew I met some of the critera, and I did relate to people with BPD a little bit after all. But it didn’t feel like “the truth”.

The main reason doctors so often insisted that I had Borderline was that I self harm(ed) quite severely. And it seems like BPD can be the only explanation for SH in adults. At least that’s where their minds jump to usually. It seems like when young women come to them with depression, self harm and some emotional regulation difficulties and they don’t really know what’s going on, they diagnose them with BPD just to diagnose them with something.

Even before I was misdiagnosed with BPD, I had a different disorder on my mind, a disorder that made much more sense to me. But I didn’t want to bring it up with my psychiatrist or even my therapist, I didn’t want to just diagnose myself, I didn’t want to seem like a hypochondriac. So I never mentioned that I suspected I could have ADHD to anyone. And for several years, no one suspected I could have it. And must that not mean that I can’t have ADHD? Wouldn’t someone figure it out over the years of therapy, three hospitalizations, and multiple psychiatrists? I did some reading on the topic, but I stopped myself from researching the disorder in too much depth, after all, if I wasn’t affected by it, why should I?

Finally, a new therapist mentioned ADHD after I described my struggles to her. She recommended I should get evaluated. And finally - I had the permission to do so. I got diagnosed with ADD, or ADHD-PI according to the DSM-5.

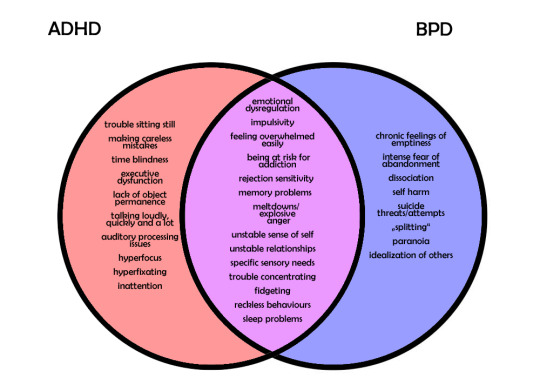

I started researching ADHD more, and discovered something that I didn’t expect: A distinct overlap in the experiences of people with ADHD and people with BPD. Let’s look at some of the symptoms of the two disorders:

Additionally, ADHD and BPD share many common comorbidities, such as depression, anxiety disorders, sleep disorders and substance abuse disorders.

Note that these aren’t the official diagnostic critera, but rather symptoms that many people with these disorders experience. These aren’t all possible symptoms, and not everyone with ADHD or BPD experiences all these symptoms.

As you can see, there is a significant overlap. After looking at the diagram, is it really so surprising I was first diagnosed with BPD? Especially since I don’t exhibit overtly hyperactive symptoms, it was relatively easy for the doctors and psychologists to focus on my emotional instability self harm issues rather than my inattention and executive dysfunction.

I just wish that they had listened to me when I told them I didn’t identify with the experiences of people with BPD. Unfortunately, not even mental health professionals always listen to their patients.

If I was diagnosed correctly earlier, I could have been spared from much suffering. Primarily inattentive ADHD is criminally underdiagnosed, and often misdiagnosed. Untreated ADHD can lead to severe mental health imparements. In my case, it lead to problems with my education, which in turn lead to many depressive episodes, severe self harm and even suicide attempts. If anyone of the dozens of people who were in charge of taking care of my mental health had considered even for just a moment a differend disorder than BPD, maybe they could have diagnosed me with ADHD much sooner.

The health care system in my country is not that bad, compared to others, but it’s still lacking in the mental health area. How many others are just like me? Misdiagnosed and suffering. I don’t wish that on anyone.

ADHD is a disorder with many faces, not at all just a “little boy who screams and can’t sit still” disorder. Unfortunately, it’s not taken very seriously and mental health professionals who really know enough about it are few and hard to come by. But if you think you might be affected by ADHD, don’t be discouraged just because you haven’t been diagnosed yet. It took me many years from first suspection it to actually getting diagnosed with it. You don’t need to wait for anyone’s permission, if you think you have it, make an appointment for a diagosis. Knowing is worth it, I promise. And when you know, you can start working on it.

I still have a long way in front of me, I haven’t found the right medication for myself yet, but I have hope. Now I know it’s not my fault that I struggle more with studying than others. I can work on not blaming myself for it so much. And learing to forgive yourself for being a bit scatterbrained is the most important part about having ADHD.

#adhd#add#adhd-pi#adhd-phi#adhd-c#bpd#borderline#borderline personality disorder#mental heal#mental illness#misdiagnosis#misdiagnosed#living with adhd#life with adhd#discussion of self harm#self harm tw#self harm#cw self harm#venn diagram#symptoms#self harm mention#sorry for the long post#long post

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

First time in a while (years) I read a list of schizophrenia symptoms and boy oh boy am I glad I never disclosed almost anything to my shrinks (thank you, trust issues) back when I didn't realize I'm chronically ill because they could've so easily diagnosed my EDS and POTS symptoms as schizophrenia, and left me to try and become content with that "answer" + probably medicated with shit that at best would've done nothing for me which, who knows, might've had me Extra Pathologized™ as treatment resistant or some shit.

Still wouldn't have explained the pain and dislocations, you say? Even physicians tell us those are all "in our heads" all the time! You think shrinks wouldn't have done the same? When those bitches are known to discredit their patients' perceptions and decisions even when they're diagnosed with like, regular anxiety, let alone one with a MUCH more stigmatized diagnosis? Please lol.

A doctor at the ER did think that (thank you MCAS for the following it was so fun) me getting THE most intense palpitations I've EVER had along with being unable to breathe, passing out on the floor for a while, nearly shitting myself and actually pissing myself while unconscious on the floor as my family tried to drag my dead weight of a body to the car, AND MORE, all from a bee sting, was just me being a hypochondriac because the bee sting scared me. :) I was just "anxious". :) Even though anxiety IN ME manifests as anger and aggression, not as helplessness, and how we told him that I initially didn't take the sting seriously. You think a SHRINK wouldn't tell me my symptoms are all a result of me being bonkers too having such a diagnosis stamped on me? lmaaaooo

Being oddly flexible and my blood dropping to my feet and getting intense tachycardia from like, going upstairs 0.1% faster than normal? Just my body being quirky (basically what regular doctors did tell me). Hair falling off in hordes? *shrugs* Stop being a vain bitch. Bruising at the glance of a feather? Did it to myself or some shit like that. Insomnia? Crazy people are just like that. Dislocations? Combo of did it to myself + All In My Head.

Me dissociating from my body 24/7? More proof of the diagnosis. Definitely not a coping mechanism to avoid killing myself from the pain and fatigue by trying to ignore by any means necessary how much my body was objectively suffering.

And once the lethargy (brain fog + fatigue), disinterest in socializing (trauma + fatigue), anhedonia (brain fog + chronic pain + fatigue), inability to focus, speak properly or Think (brain fog itself + it exacerbating my cognitive autistic traits by a thousand), declining dedication to personal care (FATIGUE + CHRONIC PAIN), apathy (fatigue, brain fog, allistics being stupid) etc, kept getting worse and worse? Who knows, maybe they would've hospitalized me and I was at some point so lost and miserable with my chronic illnesses that I would've said "Fuck it, at least they may give me frequent baths there". Or like, they might have accused me of not taking my medication, which at the time I did take religiously.

Meanwhile, my body would've still been going to shit except I would've had an even harder time at considering that maybe something was wrong with my body and not my "brain" (as if the brain isn't part of the body anyway). It was already hard to do that with the psych diagnoses I did get (especially the bipolar) but had I had that one I would've doubted my own perceptions so much more than I already do and would've chalked up Feeling Like Shit to just my psychiatric diagnosis a bitch of a thousand times harder than I did in reality. I only stopped blaming a lot of shit that's legit just my body being being chronically ill on (supposedly) Just Being Bipolar VERY recently.

Who knows, maybe having had my chronic illnesses + trauma + autism + Reactions To Being Actively Abused At The Time treated as bipolar and before that as BPD (never taking me seriously when I mentioned autism 🙃) wasn't the most damaging thing shrinks could've done to me.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Rant into the Void

I am so fucking sick of my body right now. Actually, no, that’s not the problem at all. I am actually fucking sick of the response of medical professionals to my body. My body itself is doing its fucking best, all things considered.

Put simply, I can’t face going to the doctor anymore. I’m too afraid. Which isn’t exactly a great place to be, mentally or physically, when you have a genetic condition that can (though rarely) result in life threatening complications.

I’ve never fucking liked it. Not one bit. It’s been built into me from a young age to suck things up and carry on. My dad used to passively scold me for ever taking a day off school by reminding me that he never did and telling me about all the days he’d gone to work with one ailment or another. He’s also the reason I’m so afraid of taking any medication now after years of me hearing how “taking paracetamol isn’t good for you. If you take it enough it stops working. It damages your liver too.” Even though painkillers do barely work, I can’t remember the last time I gave them a try. Now I’m older I know that he probably has his own deep seated issues that led to the things he said, but the things he said still stick like glue.

My mum was no better. As a nurse, she never took any shit from me and I would never have been able to skive off school. At one point I went to school for a week with an unknown broken arm, despite my protests. It’s rare that she explicitly called me a “hypochondriac”, but I could always tell that she was exasperated by my numerous visits to the GP, hospital and A&E. It’s only in the past year, now that my EDS has been confirmed for a second time (within the new guidelines) that she’s started to take me more seriously. I still don’t often feel able to tell her about my health concerns though, despite her having (a more mild version of) the same condition. I think she feels guilty for passing it onto me, but her responses usually comes across as frustration and annoyance.

In the past year, my fear of doctors has grown even more. Firstly, now I’ve seen what a real illness faker looks like and does, I’m forever terrified that I look like I’m doing the same. I’ve almost obsessively started taking photographic evidence of my various ailments for fear of being accused of Munchhausen's by a medical professional (despite the difficulty of convincing others of a real case of fii). Given I have also spoken out about this girl, I also live in fear of seeming like a hypocrite. Those close to me say “we know you’re really ill, we’ve seen it, we know you aren’t faking it and you’re nothing like her” but still I can’t shake the fear.

Doctors have been pretty shit lately, too. I’d had bad experiences in the past: a GP that couldn’t identify a broken elbow and a gastro consultant who suggested my pain was all in my head, but for a while I’d had a good run. The past year has been fucking awful though. One particular GP at the surgery has been the cause of almost all of it, to the point where I was going to make a formal complaint before corona got in the way. For the first time ever I had gone to an outpatients appointment alone (something I’d be afraid of due to the potential for gaslighting) and for once the consultant was amazing- he gave me a reason for my pain that had been found on an MRI and reassured me he would explain it all to my GP. However, the consultant had lied. He didn’t write in the letter anything that he said to me and GP soon decided that I was lying about my account, to the point where I questioned my own memory. Contrary to the advice of the consultant, and later my physio (who confirmed what the consultant has originally said), he advised me to walk more to solve my issue. It also took me refusing to leave his room until I got a referral to a rheumatology consultant for him to allow it. That was after him patronizing me consistently and insisting that “there’s no EDS cure you know?” and “physio is your only option”. The arrogant cunt obviously thought his single lecture had taught him more than 10 years learning about this condition had taught me. I knew my rights and got what I wanted, but I live in fear of my record being marked with “fii” or “anxious patient” that would virtually destroy any further chances of me getting treatment.

This becomes a problem, of course, when I seem to acquire a new co-morbidity or complication every month at the minute. A few weeks ago I had it confirmed that I have a bladder (and potentially pelvic) prolapse. The doctor I had spoken to before the examination though was Dr. Self Important Prick, and he had seemed doubtful of the whole thing. So even though it was proven, I’m still too afraid to call again. This week I have had a bingo card full of the symptoms of a cerebrospinal fluid leak (and not for the first time). I don’t know what to do though. Given the susceptibility of EDS patients to them, I’m fairly certain that’s what it is. Given it’s recurring, I’m also pretty sure I need to see someone. But it’s unstoppable force meets immovable object: if I go in there having done my research I seem like a hypochondriac, yet one study showed that 0% of csf leaks are diagnosed correctly the first time. These are the complications of living with a rare condition. It’s impossible to walk the fine line between advocating for yourself and seeming like a fake because you weren’t a whole chapter in the doctor’s textbook.

So here I am. Fed up. Angry at myself for not having the balls to get myself the help I need and angry at the medical profession for scarring me so badly. And with a lovely clear, metallic, currently unidentified liquid dripping down the back of my throat.

Since it seems these rants may get more regular, I’ve made a dedicated page to fill with my void rants @thatangryedsbitch

#eds#ehlers danlos syndrome#heds#hypermobile eds#hypermobile ehlers danlos#classic eds#kyphoscoliotic eds#ehlers danlos zebra#ehlers danlos type 3#ehlers danlos life#ehlers danlos problems#eds problems#spoonie#medical trauma#medical gaslighting#medical ptsd#doctor trauma#spoonie community#gaslighting#trauma#ptsd#afraid#trapped#csf leak#fii#munchausens#hypochondriac

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everything Afflicting Lil’ Ol’ Me…

Sleep Paralysis:

Starting off with the basics here because this has been what sort of started it all. When I was little, I was super into the whole idea of spirits. I honestly still am for different reasons, but it started when I was young and having sleep problems. The doctors still don’t know why it started, but I’ve always thought I sensed ‘presences’ so I told ghost stories…because I saw ‘ghosts’ in my sleep, some of which were terrifying and would sit on my chest and I’d still feel that feeling when I woke up, so duh it was real.

When I was a teenager, I started getting these hallucinations far more vividly and the doctors started to take it a lot more seriously, especially when I was getting depressed and suicidal on top of it all. Turned out I had ‘Old Hag’s Syndrome’, or ‘Sleep Paralysis’, and there was now a logical explanation for it. Basically my brain wakes up sometimes before my body does, and I’m paralyzed but I can still see the hallucinations. Feeling pinned down and violated is honestly the worst, and it fucks me up for the rest of the day mentally when it happens. It is why I’m against lucid dreaming, and why I vehemently believe in demons and evil spirits even if doctor’s wanna just call it a hallucination induced by stress. Either way, I have insomnia sometimes too and my sleep is all over the place and that never helps one’s body.

Hormone Imbalances

My hormones have probably been all over the place my whole puberty experience? Like, my periods started out being heavy, irregular and painful. I know that’s mostly normal--we women handle cramps like a boss, okay?--but I would have to stay home from school once or twice in a row every time I got my period, because I was curled up in a ball hurling: much like I do now. Going on birth control helped for a while and then started to make it worse, so we took me off of the birth control and my period started to even out and I stopped getting so sick, unless I ovulated from both sides and not just one, which they found out was also happening. Yay for the possibility of twins naturally, but yikes to the extra hormone surges.

Paraxysmol AFib:

I went through a whole stint of my early 20′s having palpitations in my chest. I just attributed it to my anxiety, and to stress because I had just finished a whole High School career of only honor’s classes, and I had switched from Pre-Med to Early Childhood Development, and so even when the doctors from an arrhythmia, I just sort of dismissed it. I didn't have the time, I was working twelve hours days as a nanny, I was doing college, and I didn't have time...and then I had an AFib attack after exercising and ended up having chest pain.

That pain lasted a month and a half without going away or getting any better, I had a bunch of doctors tell me I was being a hypochondriac, and then I got put on a heart monitor. The heart monitor caught not one but two episodes in the span of three weeks, and it was only then that they took me seriously. So even though I was ‘too young’ and ‘healthy’, I ended up becoming a heart patient at the ripe old age of 25, and it has been part of my life ever since. I take medicine daily to keep my heart rate down, because it beats too fast on its own, and I had to cut down on coffee, which...I was a caffeine addict so that was rough, lol. I’ve had to change dosages, which stresses my body out for a week each time that happens, and it has just been who I am now. I have heart patient jewelry and everything, just in case of emergencies.

Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome

So this all brings me to the next big thing: cyclic vomiting syndrome. I have been sick for 6 months now, nauseous basically every day, vomiting stints every once in a while that land me in urgent care to get IV fluids and meds because nothing will stay in my stomach, it all comes up. This started back in August, now known actual cause, and it has been my main affliction these days. I am on antacid medications, my heart medicine still, and anti nausea I have to take every single day. My body is exhausted, and that’s not even the half of it.

The doctors aren’t even fully sure this is what is going on with me, this is just how they are treating me because they can’t find anything. I have had an MRI, CT scans, ultrasounds, blood tests of all sorts (food allergies, diabetes, etc.), and everything says I am healthy. I have had a tumor removed from my esophagus when they did the endoscopy in the beginning, and I had a history of cysts (I’ve had one in my head, in my arm pits, and now one in my right nasal cavity), and I have a second and third tumor growing in my right arm. They aren’t convinced any of this is related, they just know that my period problem from high school is happening again, so they’re convinced it is hormone induced cyclic vomiting syndrome...which has no for sure cause or cure, so, that has been nice, and has triggered my depression, but I’ve been dealing with my depression my entire life.

Depression/Abuse

Since I was a kid, I’ve had a messed up home life. My uncle did some truly horrible things before he ended up eventually in jail for four life sentences, and short story on that because I simply don’t talk about it, is he used to tape my sister and I shut in boxes, and threaten us with his pet snake. He even through a knife at my cousin once, and would put my sister and up on the top shelf of the closet and leave us there.

On top of that, my Dad was never around much, and he left for good when I was 7, the same year that my grandmother died from the chemo for her ovarian cancer. He is a whole other story in itself, but he only added to my abandonment issues when I was 21 and he showed back up ONLY to talk my sister and I out of making him pay off the back child support he owed (it was a whole thing), and having the audacity to say he stayed away because he loved us...but raised our half siblings, so...just. I don’t like talking about him either.

Then I had a mother who was constantly verbally abusing my sister and I--she still does--and calling us fat even when we were skinny. Telling us we wasted our potential, telling us we’re useless, etc., and only recently getting herself the help she needs for her own emotional issues because she too was abused. Our family is filled with abusers, and she’s much better now that we’ve all addressed we have some problems, but dealing with that on top of all the other things that I deal with now, has been rough.

I feel broken. My mother tells me not to say that, but all of my health issues, and my failed past relationships with boys that have thus kept me single the last three years, make me feel that way. I’m a demisexual person who had two boyfriends cheat because they couldn’t wait for me to be ready for sex, and one basically admit after a little while that he just wanted sex and was “putting up with my feelings until then”, and I dunno, I delved farther into writing and honestly, it has been my only constant.

I’ve been writing stories since I was 6, and this is a hobby, yes, but it is also an escape when I’m not working on my stuff to get published (I’ve actually been a published author since 2011). I’m editing my second book right now and it gets priority sometimes when I’m in a funk, but I have been so sick lately because of my stomach, and just so tired and stressed with work really only keeping me on because they can’t fire me when I have medical reasons and doctor’s notes, and I just thought you guys should know.

I try to be on because writing helps me not think about all of my issues, but sometimes I’m so tired, or so sick, that I just can’t do replies. Plus, my arm with the tumors has been hurting more and more lately, and I may have to get them removed, which will mean another two weeks of a sling and pain meds, and crying myself to sleep because recovery from arm surgery hurts.

So if I’m ever slow, something is up. I love being around to write--it’s my safe space--but I’ve been dealing with a lot lately. I really do love and appreciate all of you, and I’m so grateful that you guys are so patient with me. <3

#out of mystic falls // ooc#damn writing it all out makes me feel a tad sad lmao#tw: sleep paralysis#tw: heart problems#tw: depression#tw: swearing#tw: vomiting mention#tw: period talk#tw: long post#that isn't even all of it because i didn't go into a whole bunch of detail#but that is the just of it guys

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

I miss you! 😘 Hope you are all good there.

Hi! Thank you so much for checking in and I am sorry to have responded so late, but I was preparing an exam and I was stressing a little bit. To be honest, I would really like to say everything is going well and in theory it is. It’s just not going really well in my head. And honestly, at this point I am at a loss.I know I am not a very pleasant person when I am stressed. I know I exaggerate and whatever and of course one doesn’t have to have studied psychiatry to recognize what is a symptom, but since I come fresh from that exam I definitely know that sometimes it’s just my anxiety or depression that’s talking to me.BUT, I have recently changed GP since my previous one got retired and this morning I called to fix an appointment, since I’ve been having some coughs after swallowing and they’ve been there from quite sometimes. And mind you, I have NEVER seen this GP before (so I thought I also ought to introduce myself, you know? Like I wouldn’t be happy if my phantom patient came to me for the first time after x time they’re under my care and I haven’t seen them once) and the second thing she says to me on the phone is “couldn’t this be just stress? Because I know you suffer from stress” (I don’t know who/how does she know it, but she probably had the chart on the computer, and even though I don’t have a formal diagnosis, I have been taking some medicine for some periods of time that would clue her in).To contextualize: I haven’t been to my GP for YEARS unless there was something VERY wrong with me (namely, pneumonia, like two years ago or something). And from just A CALL I’ve basically been classified into the “hypochondriac” category (I know exactly how doctors think and it’s not “normal” for someone my age or for anyone in general to be willing to go to their GP, especially for something this “minor”. The point is, my mum has a slow lower esophageal sphincter and reflux and I think I am kinda starting on that path too, but ofc I cannot magically diagnose myself because THAT would be being a true hypochondriac).In summation: I probably have social anxiety. I hate having it. I probably have symptoms associated with it. And my doctor has made me feel super worse and like an imaginary patient in just one sentence.I already feel totally worthless and I managed to feel even worse.Wonderful.And this is not the place for these discussions and I totally expect the resident hate anon to get me for this, but now I got this out of my system.It’s not the smart choice, but it’s what I wanted to write right now.Hey, all in all I am alright, bodily speaking, it’s just that my mind that has to catch up.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

So it's gonna be a health blog now.

My name is Pola, but people usually call me Corona-chan (how ironic!) or Gerardine Way. I'm a 14 year old female (even though I don't fully identify with that gender, mentally I'm genderfluid, but we're talking about physical health, aren't we?). Actually I DO have a secret (hah! no longer) interest in medicine.

Yeah, let's umm... update MY health today!

Well the situation has been very concerning lately, because I feel really sick for about a week. I hadn't checked if I maybe have a fever, because I would probably start panicking because of the pandemic, but I got chills. And the most concerning thing is that I rarely sneeze, but have a dry cough and - well - trouble breathing. I am also really tired and my head and throat hurts. But I am a hypochondriac, so maybe it's just a delusion.

My mother keeps saying I'm fine, but I'm already too scared, but I have a funny personality, so I continue to laugh at myself. I hope it's only my hypochondriasis, because I checked and this is not exactly how a flu or a cold looks like, but almost the same as COVID-19. Unhappily, I love in a small village, but there are people who may have coronavirus in the closest town! As you can guess I am very frightened, but as I am young and I don't have any long lasting illnesses, even if I got coronavirus, I would most likely make it.

Also here are some facts:

1. Wearing masks WON'T protect you from catching the virus, but if you are already infected it may protect the others, but not 100%.

2. The most important part is to WASH YOUR HANDS. Soap and disinfection fluid kill bacteria and viruses.

3. The most microorganisms can be found on the handles, toilets etc. in PUBLIC, especially the hospitals logically.

4. If you feel sick or have been to a place infected with COVID-19 or just suspect you may catch the virus, CALL (not visit) your doctor or the coronavirus hotline and follow the instructions. If you can't, STAY HOME and if you live with someone else WEAR A MASK.

What symptoms to look after?

Main coronavirus symptoms are fever, dry cough and shortness of breath. It also often causes fatigue and muscle aches. In most cases patients experience headaches and sore throat. It can also cause abdominal discomfort and diarrhea. In rare cases it causes vomiting and even bloody cough. Sneezing and runny or stuffy nose are not common symptoms, but they CAN happen. The most common complication of COVID-19 is pneumonia. Some people nearly lost their lungs and had to get a transplant. Happily the death rate is only 3.5% and nearly EVERYONE who dies is in their old age, is an infant or has some other diseases (like asthma, cancer or is after chemo). Remember! More people die of the flu every year, even though the flu infects millions and kills 0.1% or them, it is more common and it makes it more dangerous.

So I think that's all you have to know about the novel coronavirus.

How about you? How are you doing? Share in the comments!

0 notes

Text

Battling disease

This is probably one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to sit down and write. Being a naturally optimistic person, I don’t exactly like interacting with my demons or the pain that has plagued me in the past. In some aspects, I enjoy living in denial and ignoring what is bad. I try to cling to the fact that maybe if I’m blissfully unaware then the pain will just go away. It’s my coping mechanism and it doesn’t work. It’s like playing hide and seek with your shadow; it’s impossible because it doesn’t go away, it’s always with you. I can’t will the world to just be good to me. I have to be able to handle the harsh realities and chronic illness does just that. It forces you to feel it and not turn away from it. Lyme disease transformed my life; It completely rocked my body, my heart, my soul. And although there were many times I cursed my illness, I’ve landed in a place in my journey where I’m grateful for it. I don’t think anything else could have transformed my life the way my disease has.

Over the years people have asked me about sharing what I've learned about dealing with Chronic Lyme disease. What has helped me? What has hindered? How have I made progress? And I’ve always been terrified to open the floodgates of explaining and getting deep about Lyme. It was the monster in the dark that I couldn’t see but knew it was there. And I just couldn’t bring myself up to opening myself up and diving in to what really has happened to me. But it’s so healing and I need to talk about it.

Lyme disease is a tick borne disease that is very hard to diagnose and then treat. It can come in all different types of shapes and forms. Funny, when I was diagnosed with it, I was THRILLED because I had always had silly little sicknesses that were treated with antibiotics, and I would get better within days. I thought the same with Lyme disease. I wasn't quite aware that this disease would take years of my life and make me quite miserable. I was blissfully unaware and hopeful.

One thing that is most frustrating is the fact that Lyme is INVISIBLE. One minute I feel okay, then all of a sudden it seems like the floor has been ripped out from underneath me and I need to sit or lie down immediately or else I will collapse. This can be confusing to most people because we looked fine just a few minutes ago. Most of the time people think it’s all in my head but they don't understand the dynamic of being chronically sick! It's a huge balance of managing your emotions, your diet, your supplements, medicine and knowing what you can put your time into. Some days all I can do is just sit around, take care of my body, crochet, or do some minor activity. It's rather depressing, especially if you've planned out your day and had wanted to be productive, but no, you're sick and you'll only get worse if you keep pushing yourself too hard so you stay at home.

I’m hoping that this blog post will shed some light on this disease and help others who have it, or have a loved one that has it. Mind you, I’m not going into all the details about it but I wanted to open up about my frustrations with people (mainly loved ones) that didn’t understand and struggled to support me. In fact, most of the time I had to worry about not getting their feelings hurt amongst dealing with pain, anxiety and depression. It was a bit of a nightmare and I became more and more of a recluse because I hated seeing people disappointed. I wish I had a safe, easy way of expressing that pain so someone would understand and that’s what I’m hoping this will be. It’ll either help you, or someone you love.

Things that have helped me with Lyme:

1) Although it is often overlooked, emotional health is absolutely essential to your physical health and healing. After about two years of treatment, I had become quite depressed. I didn’t want to get out of bed, I didn’t want to see people that I loved, I would barely get anything done and honestly, some days I just wanted to fall asleep and never wake up again. That’s when I started to see a counselor and began the hard journey of working through emotional hold ups. I was amazed at the relief that I felt when I realized this. Our emotions toll our bodies so easily and they can also fester in certain places in our bodies and cause disease. When I had breakthroughs, I began healing and feeling better. I was amazed how much my emotions were hurting my body and not giving it the right energies to actually heal properly. You should definitely look up emotions and how they are linked with chronic disease.

2) Understanding your limits is vital! What you are capable of doing, emotionally, mentally and physically is something that anyone needs to be aware of! When I was really sick and I would have a random good day, I would fill it up with everything and anything I possibly could and then I would go down hill fast. If I was a better manager of that day then I would have another good day until I pushed myself too hard, depleted my body and boom, I wasn't doing well again. It’s hard to find what works but don’t stop trying. You have to try almost everything and anything in the book to figure out what works for you and what doesn’t.

3) Feed yourself with good food and surround yourself with good people. When I switched to a predominantly vegan, gluten free, sugar free diet and started eating more fruits and vegetables, along with a smoothie loaded with supplements every morning, I found myself getting better! My body wasn't weighed down by bad food that would frequently make me sicker. On top of that, I began weeding out the people I hung out with and set firm boundaries. If I felt someone was sucking out the limited energy that I had, I would take a step back and analyze the situation, trying to figure out if it was a situation that could be fixed or if it was someone that just needed to go from my life. It definitely helped.

4) Find something that uplifts you! During my illness, I always had to do SOMETHING so that I wouldn't go crazy. I had to lift my spirits. Before I got sick, I was a pretty active person, and I had always wanted to fill my days up with a lot of things, especially horses. But after I got sick, I couldn't go ride my horse, and if I could, it was only for a few minutes or else I would get very sick. It was depressing. I turned to being loved on by my dog and putting a lot of work into my art and talents that didn't require a lot of physical input from me and gave me immense joy. After awhile, I found that my depression was easier to manage because I could see how my dog would figure out I wasn't feeling well and would love on me and not let me leave his sight. On top of that, I could see what my hands were creating with art. I could write something down, a short story, or write a song and I could see that I created something through my hardship. Find what brings you joy, makes you laugh and don't let yourself get so focused on other things that you forget it.

5) Try anything and everything. It took my awhile to find something that worked for me. I tried all sorts of different treatments, antibiotics, IVs, Picc lines, oxygen therapy, etc and I didn’t really find that much helped me except for going to a kinesiologist weekly, taking a lot of supplements, diet and taking a homeopathic designated for Lyme disease.

6) Know how to detox. Make sure you drink plenty of water and have a bath with epsom salts at least once a day. It will help detox your body and you will feel better. In the early stages you will probably have a very overwhelmed body that when it detoxes just a little it will go into a full blown herxheimer reaction due to all the die off and the detoxing you’re experiencing. But it gets better.

7) Last but not least, you WILL GET BETTER. Say that with me again, YOU. WILL. GET. BETTER. Write it on your wall, have a reminder in your phone or somewhere obvious where you are reminded that your life is not over and you WILL get better. Positivity is the biggest factor.

Things to know if someone you love has Lyme:

1) When someone with Lyme is feeling absolutely horrible they are likely looking no different on the outside than they do on one of their “really good days”. This disease usually does not present itself with obvious visible symptoms, and if it does, we’re normally thrilled and want to show it off because battling a predominantly invisible disease is horrible -mainly because people just don’t understand. Be kind to us, don’t think we’re a bunch of hypochondriacs; that just makes us feel even worse.

2) People with Lyme disease quickly become amazing actors because otherwise no one would be our friend! Most people believe that a round of antibiotics will heal us and we will be normal again but they don’t realize how there is no “magic shot” or quick fix for chronic Lyme disease. What is most frustrating about this disease is that one treatment won’t fix all. Each Lyme case is unique and will respond differently to treatment. Often times we need months of treatment, an assortment of different doctors and health care practitioners before we find SOMETHING that works. It’s a frustrating journey, and no matter how upset you as a loved one may feel, know that the person you love feels it 100 times worse. We often feel disappointed and depressed that we aren’t better yet. We need your reassurance to stay hopeful so we can persevere through the hardships that are bound to happen with this awful disease.

3) Lyme treatment causes something known as a “herxheimer reaction”. Or a “herx” for short. Similar to how chemotherapy makes a cancer patient feel worse, when someone with Lyme disease takes antibiotics, it can cause a large amount of die off which releases a huge amount of toxins into the body. This basically results in all of our regular symptoms being amplified as it takes some work for our bodies to get rid of these newly circulating toxins. Often times our bodies are so overburdened that they are not efficient at detoxing these toxins well, so it’s a difficult process, and definitely not an easy one to endure at all. Unfortunately, it is often necessary to push through this in order to make improvements.

4) Lyme disease treatment is extremely expensive, and likely not covered by insurance. Most treatment that can be covered by insurance is the newly bitten person that has gotten a small amount of symptoms and begins taking a round of antibiotics. In most of these cases a few weeks or few months of antibiotics are all that is needed to regain health. But when you have late term chronic Lyme disease, you aren’t so lucky. We have to try almost everything to find something that works. Sometimes this means traveling to doctors on the other side of the continent, maybe even the world. Or trying new cutting edge treatment options that are pricey and paid for out of pocket. This is a bit of a nightmare for us, as we already have the huge burden of failing health to carry, and don’t need the added stress of coming up with enough money to get better.

5) If you want to help your friend, or loved one, offer to host a bake sale or fundraiser to help raise money for their treatments, or just be there to listen and love on them. It will probably mean more to them than you know. Company, even if it’s not much, is extremely appreciated with someone that is dealing with Lyme.

6) Be your friend or loved one’s cheerleader! Keep them persevering and don’t let them give up! We need all the support we can get!

9 notes

·

View notes

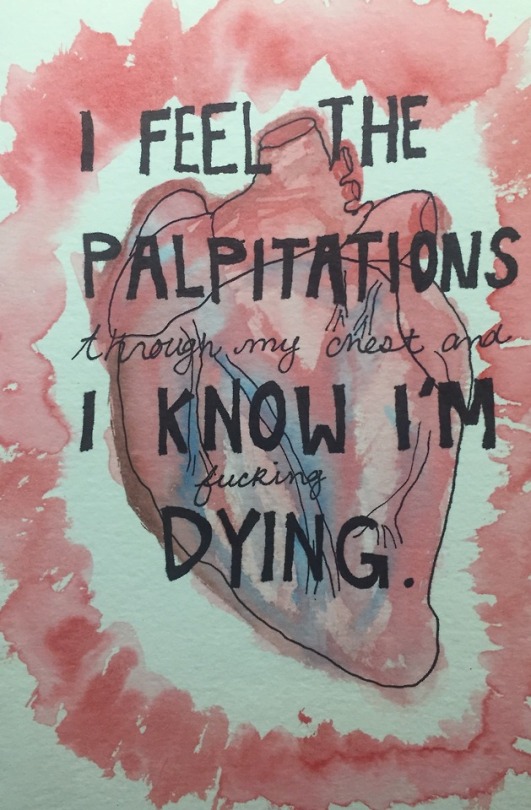

Photo

#4

This is a painting I did recently after learning more about tachycardia and palpitations and afib, and of course after I convinced myself I had all three. It was very therapeutic to sit down and paint this out without having to do an entire journal entry. Sometimes, art can speak much louder than a narrative of any sort.

In my last post, I mentioned that with more medical knowledge comes more stress for a lot of people. While a rather small sample size, of the 23 people I know who are pre-med, 21 agreed that they have thought at least one time that they had a serious rare illness they have read about. Interestingly enough, of the 7 doctors I asked at work, all of them said that since accepting their job years ago, they have not had any health related anxiety, as there are too many patients to worry if they have something or not. Also, they know exactly what to look for, while most medical students in the early stages are reading broad literature and have no clinical experience. So lesser educated students have an easier time jumping to crazier conclusions.

“Hypochondriacs tend to latch onto diseases with common or ambiguous symptoms or that are hard to diagnose” as per https://www.webmd.com/balance/features/internet-makes-hypochondria-worse#2. And this is true. A brain cancer is hard to diagnose, but everyone has headaches. A stroke can sometimes be hard to diagnose in a healthy adult, but everyone feels random sharp pains sometimes / general fatigue.

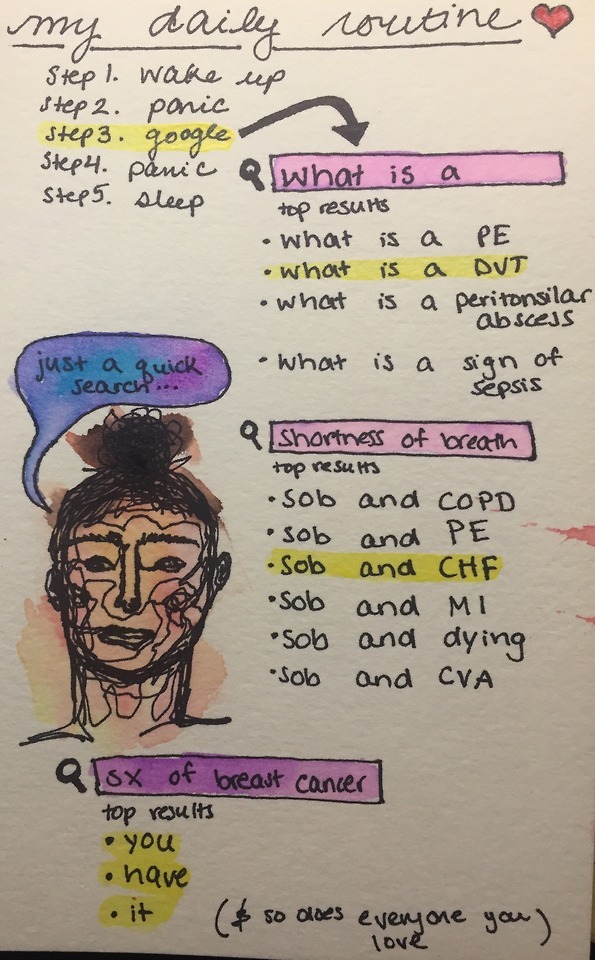

So it seems that there is a cap to medical knowledge causing hypochondria in students, until they become a doctor and then the stress goes away to make room for new work stresses. However, most people aren’t becoming doctors. Most people are in business, retail, engineering, teaching, or what have it. So a lot of people will acquire knowledge from online sources like Wikipedia, WebMD, or the Mayo Clinic and freak out, running to their doctor saying they think they have HIV, or Diverticulitis, or kidney stones, but it turns out they actually just had too many tacos at dinner and had a little stomach ache.

But people suffering from hypochondria read these symptoms - abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, nausea, malaise, weight loss, etc, and they convince themselves they have it until some physical interpretation of it manifests. But before the advent of easy access medical information, people did not have the proper words to diagnose themselves, which makes it harder to convince yourself you have something wrong with you.

I’m not sure that makes 100% sense, but let me try to clarify: you have stomach pain that would otherwise resolve in a day without any intervention. Before WebMD, you would probably either just ride it out, taking at home laxatives or something, and call it a day. But with technology, one google search of abdominal pain can quickly lead to a pancreatic cancer diagnosis. And then panic sets in. You’ve vomited before, sure. And you haven’t seen a doctor recently. And maybe you made some bad lifestyle choices. And you’ve given your symptom a name. A real medical term. It is no longer abdominal pain, but rather a Big Something that requires attention.

My point here is that giving your symptoms a name makes them feel maybe more real than they are, perpetuating the notion that you are sick.

Plot twist - you are sick - just not in the way you think (health anxiety is a sickness within itself!)

But no conclusive studies have been done that links the internet with increased hypochondria, however, after working in an emergency department for about a year, I can safely say, at least in the Hoboken/Union City/Jersey City area, people are definitely using the internet to self diagnose diseases that they do not have. I think this also creates more crowded emergency departments, as there are mothers who bring their babies in for one episode of vomiting and she is convinced her baby is suffering clinical dehydration and an electrolyte abnormality, when in actuality she overfed her kid in a breastfeeding session and the kid puked a little up. But the doctors, already incredibly stretched thin, have to do an entire workup for this child, because well it’s the ED and if they don’t catch something, they could get their asses sued so quick. And you know that entitled Hoboken mother would absolutely.

On another note, I know the internet has influenced hypochondriacs because well, hi there. My most frequented website happens to be WebMD. And I will search their site until I have successfully diagnosed myself from one symptom of a runny nose. Seasonal allergies? Never heard of it. It’s obviously the swine flu.

-EA

0 notes

Text

The Strange, Isolated Life Of A Tuberculosis Patient In The 21st Century

New Post has been published on https://kidsviral.info/the-strange-isolated-life-of-a-tuberculosis-patient-in-the-21st-century/

The Strange, Isolated Life Of A Tuberculosis Patient In The 21st Century

While volunteering for the Peace Corps in Ukraine in 2010, I contracted a severe version of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Two years of painful, isolating treatment taught me the vital role social media may play in finally eradicating this disease.

One of the loneliest nights of my life was when I masturbated for an Australian stranger on the only webcam chat site that would load on the shitty hospital Wi-Fi. He didn’t want to show his face on camera, and I didn’t care whether it was because he was famous, married, or ugly. The internet was so slow that the sound stalled, so the dirty talk had to be typed.

It was a terse, space-economizing raunch, pounded out letter by letter with his left index finger, since his dominant hand was busy. I WANT TO VERB YOUR NOUN. But the artlessness was a relief. The more work it took to type, the less likely he’d waste time asking about my hospital bed and IV rack. If I didn’t mind him being headless and talking like a filthy grown-up “see spot run,” couldn’t he handle a naked stranger in a tuberculosis sanatorium?

Nor did he mention the armband, which hid the nozzle nurses screwed to dripping sacks of drugs during infusions. Three times a week, amikacin seeped down the skinny 2-foot-long tube inside and up my arm, leading behind my collarbone to splash into a big fat artery over my heart.

Just please don’t fucking ask, I thought. It was exhausting to explain. Screw this guy. Wouldn’t it be weirder if he had inferred a medical emergency, but resolved not to let it ruin his hard-on? Do virtual strangers without heads even have cognition? What the hell was wrong with this guy’s face, anyway?

Who cares? I had been in that room in Denver for almost a month. I was days away from lung surgery to remove my upper right lobe, where the bulk of the disease was headquartered. This was the last goddamned time I’d ever get to show my tits to a stranger without any scars. And it was the skinniest I’d ever been.

I had contracted extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis, or XDR-TB (a severe version of multidrug-resistant, or MDR tuberculosis), while serving as a Peace Corps volunteer in Ukraine. The National Jewish Health Center is no longer a sanatorium, but it is still one of the country’s top TB research facilities, staffed by worldwide mycobacteria experts and equipped with properly ventilated rooms for the infrequent consumptives who turn up there.

When I was admitted to the hospital, the state of Colorado dispatched a guy to my hospital room to read me my legal quarantine order. I’d be in isolation for however long I was contagious.

During my stay, I started a two-year course of harsh antibiotics, including an IV drip. I had two surgeries, which flanked a blood transfusion and peskily recollapsing lung. I lost 12 pounds and half my blood, which have been replaced, and the upper lobe of my right lung, which hasn’t. I wish I could be more inspiring. But I didn’t use that time to write a novel, learn yoga, or even plow through a beach read. Falling into a trance and getting off strangers was all I felt capable of.

Objectifying? Sure. So is being sick.

Such isolation — both physical and emotional — takes a serious toll on TB patients. From the 18th century glory days up to the modern rise of MDR, tuberculosis went from being a relatively universal human experience to being a profoundly lonely one. Isolation and stigma make long treatments even harder to endure and inhibit public consciousness that could lead to more meaningful progress. But we may be approaching a new historical moment: Social media makes it easier than ever for patients to find and support one another. These connections can improve patient morale and treatment outcomes and ultimately raise the profile of MDR-TB in global health policy.

Because I was never as alone as I thought: Five thousand miles away in Siberia, a woman my age named Ksenia Shchenina was also suffering. So are patients in dozens of other countries, and more and more of them are beginning to use the internet to combat the solitude that has long not only defined the disease and its treatment, but kept it from being eradicated for good.

View this image ›

Most people don’t spend much time thinking about tuberculosis. If pressed, they might make a few basic generalizations. It was a very serious disease in the olden days. It killed your great-great-grandfather, all of the Brontës, and Nicole Kidman’s character in Moulin Rouge. But then it was cured. It doesn’t exist anymore. So we’ll all just have to get Ewan McGregor’s attention some other way and die of something else.

Tuberculosis has been on the scene since ancient times, but it only reached menace status in filthy, urbanizing mid-17th century Europe. It went on to dominate the continent’s “cause of death” list for over two centuries. This makes sense, if you know how germs work. Poverty and bad sanitation — e.g., the Industrial Revolution’s toxic work conditions and shantytowns — made toppling immune systems a cinch. Before germ theory caught on, some people even saw TB as a sort of moral retribution for the sins of modernity.

Even the disease’s classic name — consumption — implied a physical and spiritual connection. It consumed you; it devoured you from within. Before the scientific consensus on how an infectious disease was transmitted, many people assumed a person could be predisposed to consumption. (They caught on to genetics before they unraveled epidemiology.) An entire family of consumptives probably meant they were ill because they had all inherited the proper preconditions for the illness — not because they lived together and coughed fatal microbes into one another’s food. Similarly, researchers couldn’t help but notice that consumption disproportionately seized writers and artists, whose lifestyle was practically synonymous with urban poverty. But when it was still assumed that the disease grew from within, many scientists searched for a link between consumption and genius. This is the kind of factoid that makes you feel smug when modern doctors are really, really surprised that you got this.

The jig was up in 1882. A German bacteriologist named Robert Koch zeroed in on the Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterial cause of consumption. It spread from person to person by air.

View this image ›

Robert Koch Ann Ronan Pictures / Getty Images

Koch’s early attempts to develop a vaccine failed, but his efforts did yield a valuable diagnostic tool: the tuberculin skin test. It’s a shot that scans for TB antibodies. If you’ve been exposed to the disease, the injection site on your forearm will flare up into a BRIGHT RED SKIN MOUNTAIN. The test is still part of routine checkups today among grade-schoolers, teachers, cops, and — as I would learn — Peace Corps volunteers.

There is a photo of me on Facebook from early 2010, lodged between a handful of party shots with fellow volunteers. We had traveled to Kiev from across Ukraine to make a weekend out of our mid-service medical checkups. I’m 23, hamming it up in melodramatic distress, and twisting my left elbow up over my head to show off the swollen red splotch on my forearm.

A positive skin test usually doesn’t mean you have TB — less than than 10% of people with positive skin tests ever develop an active case, because healthy immune systems can usually defeat the bacterial intruder. Several volunteers each year end up with the telltale red blotch; it was really nothing to worry about. We’d need a follow-up X-ray, but an active case was highly unlikely. So I cracked a few jokes and went back to pounding flat Chernigivske beers with my friends.

I had been in Ukraine since September 2008, after studying Russian in college. I volunteered at a school in an eastern mining town called Antratsyt. The town borrows its name from anthracite coal. The region is flat, but you can see hills in the distance — they’re “slag heaps,” or piles of debris extracted from mines. The town only runs water for a few hours a day to protect the mines from mudslides or collapse. But life wasn’t as bleak as it sounds. I had students who were so excited to practice their English that they would chat with me after school, perched in a row on the edge of a Soviet-era fountain long-since bone-dry. I struck up friendships with their parents and my fellow teachers. I toasted my colleagues over champagne and chocolate on Ukrainian holidays. One time, I even gave a thickly accented speech on international education at a school assembly that ended up on the TV news. I was happy.

My follow-up X-ray was two weeks later, in Kiev. Taking yet another 17-hour train trip felt like an epic hassle. Is there a word that means the opposite of hypochondriac? There should be, because that’s what I am. In hindsight, of course I had symptoms – I just wrote them off to other things. I had a bad cough, because I was a smoker at the time. I’d lost weight, because there was no American junk food to lose my will power around. I was run-down and sluggish, because it was the Ukrainian winter!

I got a ride with Dr. Sasha, one of the Peace Corps’ Ukrainian staffers, to my screening at a tuberculosis dispensary — tubdispensar — on the edge of the city. He spoke the sort of English that made me self-conscious about my Russian. He carried my Peace Corps medical history file on his lap. The most dramatic thing in it was an allergy to mangoes. (Not exactly a significant handicap in Ukraine.)

I was X-rayed in a machine that looked like an iron colossus. In the waiting room, I tried to distract myself with a biography of John Adams. (His son, John Quincy, spent years in the Russian Empire as Ambassador and managed to stay consumption-free.) Soviet-era medical facilities are much more dimly lit than their Walmart-bright American counterparts. To see the page, I had to squint.

The head TB doctor finally called me into the office. He explained the X-ray results and prognosis to Dr. Sasha, who relayed them in English to me. But when Dr. Sasha asked a follow-up question, they flipped back to Russian and cut me out of the triangle. My Russian was good – but not “unfamiliar medical jargon” good. But this wasn’t a conversation I could stand to be excluded from. I was on the brink of a tantrum.

“Goddamn it!” I wanted to shriek at the TB doc. “Don’t say it in his Russian. Say it in mine.”

My face must have looked like a cartoon teakettle. So he slowed down and turned toward the image pinned to the light board.

“Classic pulmonary TB,” he said to me. (Words like pulmonary and tuberculosis are cognates.) “It’s strange that it advanced so quickly. Especially for a healthy young girl.”

“Are you sure?” I asked. “I heard you guys muttering about bronchitis or pneumonia before. Could it be one of those?”

“No. We assumed it could have been at first, but this is a clear case. See, on an X-ray, healthy lungs should look solid black. See the contrast down by the lower ribs? But now look up on the right. See the [blahblahblah]? The [blahblahblah] is the tuberculosis.”

“I’m sorry. I didn’t get that word. What part is the tuberculosis?”

He sighed. It would have been easier to let Dr. Sasha translate. Now he had to dumb down his lexicon for a rattled American.

“Up there. Upper right. Well, left on here. That white spot? The part that looks like a ghost.”

That night, I started treatment in a studio apartment the Peace Corps rented for me in Kiev. My prognosis was good. For two weeks, I took pills, got X-rayed, and hocked up sputum — a polite word for loogies — into sterile plastic cups for lab work. One set stayed in Ukraine; the other was shipped according to special biohazard protocol to an American facility to better coordinate my care at home.

Eight weeks later, just as life was settling down back in Chicago, I was surprised to find an ominous number of missed calls on my phone: from the diagnostic lab, my mom, my American pulmonologist, my mom, the Cook County Department of Public Health, my mom, my mom, the Cook County Department of Public Health Epidemiology Unit, my mom, my mom, my mom, my mom, my mom.

Those loogies had yielded bad news. I had XDR-TB. The bad kind.

Effective immediately, I was placed under an isolation order. I was told to stay home whenever possible — I could go outside sparingly, but any other indoor space was off-limits until I was noninfectious. A few months, at least. The police could get involved if I didn’t comply.

A month into my quarantine, my Chicago doctors were stumped. They’d rarely seen anything like this.

So I set off on a journey not unlike those taken by consumptives a century before. I left my bustling, industrial Midwestern city and headed west, to the National Jewish Health Center in Denver.

It was the National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives back then. In 1899, the brand-new philanthropic institution was brimming with needy patients. In 2010, I was the only one.

I told almost no one where I was going. I had already been avoiding friends who tried to contact me. It is exhausting to have your life flipped around by something people know nothing about. You get so damn sick of telling the story. Weird caveats demand exposition. Here is what I have. Here is why it’s bad. Here is why I had to evacuate Ukraine and leave the Peace Corps early. Here is why I can’t be in public or see anyone for the foreseeable future. Here is why I am going to some hospital in Denver for a long time. Here is why they chopped off a big chunk of my lung. Here is why I have this IV armband thing for nine months. Here is why I puke a lot. Here is why food tastes all wrong. Here is why my hearing got warped. Here is why I can’t feel my toes. Here is why I am not supposed to drink any alcohol. Here is why I’m still going to anyway.

Since I was on the no-fly list, we drove the 15 hours by car. I wore a mask the whole time so I wouldn’t infect my parents.

View this image ›

National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives c. 1920

Basic infection control, like isolating the sick and using protective gear to lower transmission risk, may seem primitive compared with modern medicine. But the truth is, public health measures like quarantine and mouth covering did more to eradicate tuberculosis than drugs did. We never did figure out a great way to cure TB; we just got better at preventing it. That is, until it caught up with us.

After Dr. Koch’s splashy 1882 debut of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the medical community was certain a surefire solution was close behind. But they were disappointed. No cure came.

Forty years later, a new vaccine — Bacillus Calmette-Guerin, or BCG — entered human testing. But BCG was never that good. Most researchers believe that adults are just as likely to wind up with TB whether they get BCG or not. It also suffered a major PR setback as the center of one of the worst vaccination disasters in history. In 1930, 73 babies died of tuberculosis meningitis after being injected with BCG in Lubeck, Germany. The vaccines had been contaminated after getting mixed up with a virulent live TB strain back at the lab. (Life hack: Always be sure your doctor has a label maker.)

It wasn’t until 1943 that a team at Rutgers University pinpointed streptomycin, the world’s first antibiotic effective against tuberculosis. TB’s staggering cultural legacy made the discovery a shoo-in for the Nobel Prize, but streptomycin was nonetheless terribly flawed. It was toxic, and patients quickly developed antibodies that resisted the drug. The only solution was to scrape around for more options and blitzkrieg every case of TB with several so-so drugs at once. The first-line regimen has hardly been tweaked in nearly 50 years. It was never a secret that such a long and tedious course of antibiotics would, like a Shakespearean hero, engineer its own demise.

But that hardly seemed to matter. By the time streptomycin ‘n’ friends showed up, barely anyone even needed them. Throughout the 20th century, people gradually stopped getting TB in the first place. We got healthier, cleaner, and smarter. We could contain disease and catch it early. It nearly disappeared.

Then, in the early 1990s, it bounced back. Two global crises — the rise of HIV/AIDS and the fall of the Soviet Union — helped resurrect the scourge of the 19th century. The World Health Organization declared a worldwide TB emergency in 1993. (It just goes to show: Don’t count your eradicated diseases before they hatch.)

AIDS was even harder on human bodies than the Industrial Revolution had been, and millions of centuries-won immune systems were suddenly wide open to infection anew. TB remains the leading cause of death among AIDS patients.

The collapse of the USSR spread TB in even more complicated ways. The year 1991 saw the traumatic birth of 15 brand-new post-Soviet republics. Each of these new countries was in economic and social turmoil. They were broke. They had no central government or public health system. Before their independence, everything had more or less filtered through Moscow. In some places, there were few to no supplies or institutional infrastructure, let alone money for health care workers. Alcoholism and malnourishment soared. People lost their savings. Rampant crime stuffed the prisons — notorious hotbeds of TB — to well over capacity. Released inmates carted these germs back to their communities. By the time the 15 new countries had smoothed things out, they already had a new old epidemic to battle.

Even as the immediate post-Soviet crisis improved, other factors played into treatment interruption and new infections. These have been beautifully documented by experts like Dr. Lee Reichman in his 2001 book Timebomb and are easily rattled off by every post-Soviet MDR expert I’ve come across. Treatment in prisons has been badly underfunded, so for years people didn’t get the meds they needed. There is often subpar follow-up for ill prisoners after they’re released. Infected migratory workers are tough to treat and track. The Soviet-era mentality of medical specialization has made the region slow to coordinate HIV and TB care. Both illnesses are also correlated with substance abuse, and addicts often turn out to be less-than-diligent patients. In sum, the long, hard treatment places economic, social, and physical strain on patients.

Antibiotic treatment is an all-or-nothing game. Patients need to take every dose by the book, or germs acquire resistance. Getting it done right depends on stupendous public health programs, not to mention stupendous patients. Once a strain does acquire resistance, it can’t be undone — and the stronger, harder-to-treat germ is passed on to others, like me. If the best drugs don’t work, doctors are forced to use drugs that are even harder on the body. All of these factors collude to paint a grim reality. In former Soviet countries, only around 60% of patients who begin tuberculosis treatment ever successfully finish it. The rest of them flee, slip through the cracks, fail to respond to treatment, or die before they are cured.

So it is no surprise that the region has the highest rates of MDR-TB in the world — as many as 30% of all newly detected cases are impervious to first-line drugs. (The global average is reportedly less than 5%, but statistics are widely believed to be low, especially in resource-poor countries. In the U.S., there were fewer than 100 cases of MDR in 2013.) Even in optimal conditions, the difference between a case of run-of-the-mill TB and MDR can be the difference between a moderate inconvenience and a life-threatening catastrophe. A standard case can be cured for less than $100 with a daily dose of four different drugs for six to nine months. My treatment cost taxpayers seven figures and lasted well over two years.

On paper, many of these problems have already been fixed. A decade ago, Tracy Kidder’s best-seller Mountains Beyond Mountains lauded the achievements of Dr. Paul Farmer’s Partners in Health and other global health organizations in revolutionizing worldwide MDR-TB care. The region’s TB programs are now relatively well-organized and padded with funding from global health mammoths like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. There are detailed and standardized treatment guidelines. TB drugs are fully subsidized. So why are so many patients still failing their treatments?

Without an effective vaccine or better drugs, efforts to curb MDR-TB face a serious paradox. As a strain becomes more resistant, it becomes simultaneously more painful and more urgent to treat it. Many countries have responded by adopting stringent patient monitoring policies, which improve cure rates but are nonetheless no small imposition in patients’ lives. Public safety overrides patient agency, which is a tough pill for victims to swallow (and they’ve already got plenty of those to worry about).

View this image ›

A patient receives the TB vaccine in 1949 Cornell Capa / The LIFE Picture Collection / Getty Images

During my treatment, I felt sick for two years. Nausea became my baseline. Sometimes the drugs make you puke, or give you the kind of diarrhea that makes you need a nap. One screws with your nervous system, and I permanently lost most of the feeling in my feet. I’ve tracked blood across kitchen floors because I can’t tell if I’ve stepped on shattered glass.

And I had it lucky. I had no comorbidities like HIV or diabetes, which make everything even worse. Being on amikacin cost me some low-frequency hearing, but it has caused deafness in others. And I got to take it by IV drip, instead of the painful upper-thigh injections that leave some patients too sore to sit up. And while cycloserine — a drug nicknamed “psychoserine” for its notorious mental and behavioral effects — makes some patients hallucinate and scream, I got away with confusion. I had trouble with reading, organization, and paperwork. It’s an especially tough break if you’re dealing with a workers’ comp claim for a medical disaster. I couldn’t keep it all straight, and walloped my credit.

Even worse, most patients in former Soviet countries and across the world get practically no social support during the crisis. They get little help with side effects, and suffer serious social and economic strain. Many of them have no way to make up for lost wages over the course of their treatments. Some even face lasting discrimination. In 2011, an undercover Ukrainian journalist wrote an exposé about being iced out by hiring managers after casually mentioning a past bout of TB.

The reason why boils down to one key factor: Tuberculosis remains highly stigmatized throughout the world. In the former Soviet Union, people associate it with painful memories of the lawless, chaotic ‘90s. Having it means you’re a crook, a junkie, a drunk, a bum, or a sewer rat.

Stigma makes epidemics worse — it gives people a reason not to be seen walking into a clearly labeled TB clinic to see a doctor when they should. Loneliness and despair can convince someone that health doesn’t matter, so why take these pills? And stigma shuts people up, so they’ll never organize, influence funding, or change minds about TB. Stigma means more stigma.

When patients are silenced and isolated from one another and their communities, it stymies progress against the disease. The WHO estimates more than a $1.3 billion worldwide funding gap in TB research and development, and the number threatens to grow. Even though investment in new drug research is one obvious way to improve treatment, AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Pfizer recently pulled a combined $50 million out of the fight. According to an email from the Treatment Action Group, a TB and HIV advocacy nonprofit, this steep loss amounts to a full third of private-sector TB investment since 2011.

Erasing stigma, combating TB’s chronic underfunding, and promoting new research and drug development are incredibly lofty goals. But similar barriers have been conquered before in diseases like breast cancer and HIV/AIDS, where passionate activism made incredible inroads in raising awareness and influencing policy. If former and current TB patients joined together, could they build the first real advocacy movement centered on patients?

View this image ›

llustration by Ashley Mackenzie for BuzzFeed

Tuberculosis patients haven’t always felt so alone.

After leaving Denver, I read The Magic Mountain, Thomas Mann’s sprawling 1924 classic novel about a Swiss sanatorium. I forced myself to finish it, but it’s the most boring book I’ve ever read. It’s the story of a total wiener named Hans Castorp who goes on a trip to hang out in the Alps and visit his TB-stricken cousin. Then Hans ends up sticking around and living there for seven years even though he doesn’t really have tuberculosis, just so he can do stupid crap like spend 70 pages talking about the nature of consciousness.

Ugh, I’m still so mad at him. But maybe it’s because I’m a tiny bit jealous. So what if he’s a fake person with fake tuberculosis? It would have been so nice to have someone to be sick with.

Sanatoriums, like National Jewish and the one atop The Magic Mountain, bridged the gap between the mid-19th century and the 1940s discovery of streptomycin. With no cure in sight, the ill had long made do with an iffy array of treatment options. Some doctors stuffed people’s windpipes with vacuum contraptions to simulate lazy lung capillaries. Cottage industries of miracle cures gorged on ad space in periodicals, sandwiched among serial installments of now beloved classics. (If you liked Great Expectations, you’ll love Daffy & Son’s Natural Miracle Multi-Purpose Health Elixir! Available wherever fancy wool top hats and snuff boxes are sold!!!) But the White Plague seemed to beat them all.

Tuberculosis did have one semi-formidable opponent, though — one hope that physicians agreed on. It wasn’t a cure; it wasn’t a given. The idea came from an 1840 pamphlet written by Dr. George Bodington, a British family doctor who covered a large area by making his house calls on horseback. His essay was based on a simple observation: that consumptives in wide-open spaces fared better than those packed tightly in cities.

But Dr. Bodington drew a further conclusion: It must have been the country air that healed them. Their bodies need pure, unsoiled air, shared with as few people as possible. Depending on the severity of their case, they might need months or years of it. In the disease’s final stages, Mycobacterium tuberculosis finally chews through the lung tissue, resulting in the bloody cough that famously beckoned death (but, curiously, couldn’t stop the heroines of Les Misérables, La Bohème, and La Traviata from singing). If combated early with the right dose of air, the process could drag to a halt.