#thinly-veiled allegories for direct expressions of affection

Text

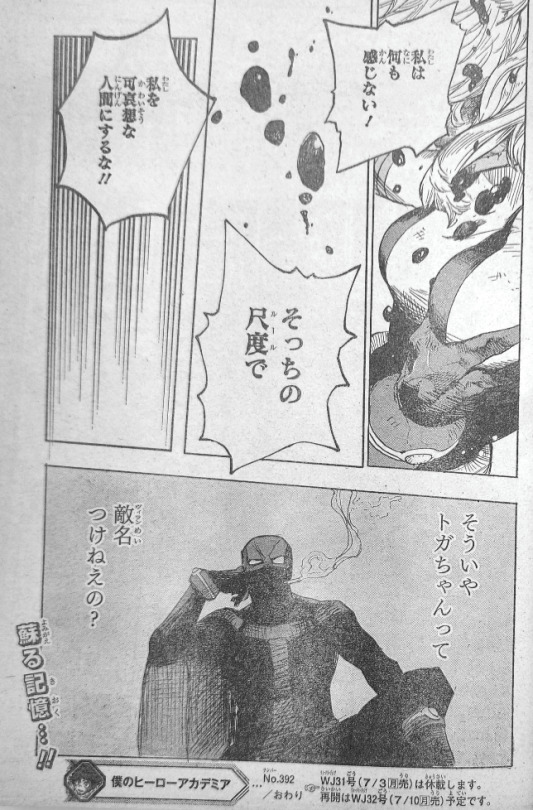

MHA Chapter 392 spoilers translations

This week’s initial tentative super rough/literal translations under the cut.

1-2

私の何を知ってるの⁉︎

わたしのなにをしってるの⁉︎

watashi no nani wo shitteru no!?

“What do you know about me!?”

tagline 1

大軍にのまれ!

たいぐんにのまれ!

taigun ni nomare!

Swallowed by a giant army!

tagline 2

No.392 ヴィラン名 堀越耕平

ナンバー392 ヴィランめい ほりこしこうへい

NANBAA 392 VIRAN mei Horikoshi Kouhei

No. 392 Villain Name Kouhei Horikoshi

3

フロッピーーー‼︎

FUROPPII--!!

“Froppy--!!”

4

奥渡島のダメージで

オクトじまのダメージで

OKUTO jima no DAMEEJI de

The damage I got at Octo Island,

5

くっ…うまく捌けなかった…!

くっ…うまくさばけなかった…!

gu...umaku sabakenakatta...!

ggh...I didn’t handle it well...!

1

何一つ不自由なんかなかったくせに

なにひとつふじゆうなんかなかったくせに

nani hitotsu fujiyuu nanka nakatta kuse ni

“Even though you had not even one inconvenience,”

2

ルールに合ってただけのくせに‼︎

ルールにあってただけのくせに‼︎

RUURU ni atteta dake no kuse ni!!

“even though you only followed the rules!!”

3

生きやすく産まれただけのくせに‼︎

いきやすくうまれただけのくせに‼︎

iki yasuku umareta dake no kuse ni!!

“Even though you were born only to live easily!!”

(Note: This grammar pattern sounds more accusatory than it might sound in translation. The overall message is basically: “How could someone like you, who has only ever had such an easy life, know anything about me!?”)

1

スズメを殺して血を啜って

スズメをころしてちをすすって

SUZUME wo koroshite chi wo susutte

You killed a sparrow to drink its blood,

2

笑ってるなんて…

わらってるなんて…

waratteru nante...

and then you smile...

3

違うの

ちがうの

chigau no

No, it’s different.

4

お庭に落ちてたの

おにわにおちてたの

oniwa ni ochiteta no

It had fallen in the garden.

5

ハイ矯正していきましょう"普通"に

ハイきょうせいしていきましょう"ふつう"に

HAI kyousei shite ikimashou “futsuu” ni

All right, let’s go and correct you to normal.

6

あ ハイもうちょっと待ってください

あ ハイもうちょっとまってください

a HAI mou chotto matte kudasai

Ah, yes, please wait a little longer.

7

すぐそっち行きます

すぐそっちいきます

sugu socchi ikimasu

I’ll be right there.

8

えっと…

etto...

Um...

9

ええ大丈夫です

ええだいじょうぶです

ee daijoubu desu

Yes, it’s fine.

10

そうですね…

sou desu ne...

That’s right...

11

強い"個性"を持つ子にありがちな倒錯ですよ

つよい"こせい"をもつこにありがちなとうさくですよ

tsuyoi “kosei” wo motsu ko niarigachi na tousaku desu yo

It’s a perversion common to children who have strong quirks.

12

この社会ではよくあることです

このしゃかいではよくあることです

kono shakai de wa yoku aru koto desu

It’s a thing that happens often in this society.

13

正して消していきましょう

ただしてけしていきましょう

tadashite keshite ikimashou

Let’s go correct and erase it.

1

ヒミコちゃんの顔コワーイ!

ヒミコちゃんのかおコワーイ!

HIMIKO-chan no kao KOWAAI!

Himiko-chan’s face is scaaary!

2

やめなさい‼︎何をしてるの

やめなさい‼︎なにをしてるの

yamenasai!! nani wo shiteru no

Stop it!! What are you doing?

3

まるでーー異常者だ!

まるでーーいじょうしゃだ!

maru de--ijousha da!

It’s like--you’re a deviant!

(Note: I feel obligated to point out that the word for “deviant” also works as a word for “pervert.”)

4

普通しなさい!

ふつうしなさい!

futsuu shinasai!

Be normal!

5

あの子ぜんぜん話合わないんだもん

あのこぜんぜんはなしあわないんだもん

ano ko zenzen hanashiawanainda mon

That kid just doesn’t speak on the same wavelength [as us].

1

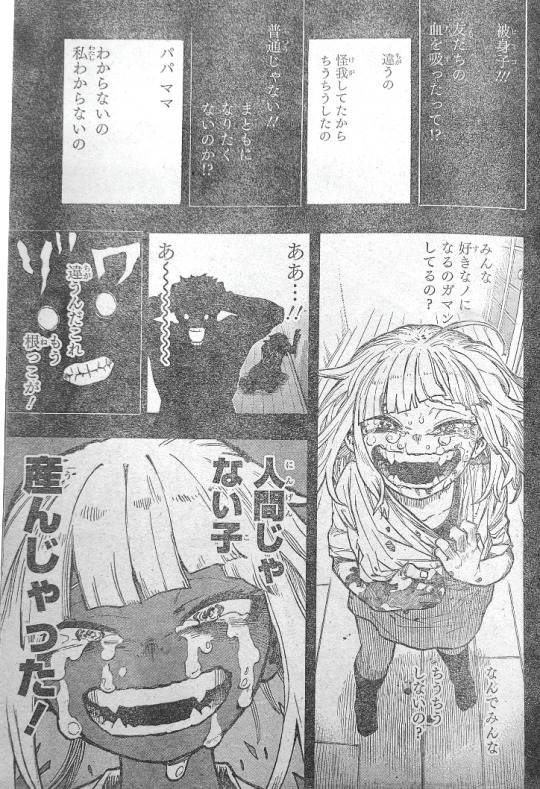

被身子‼︎

ヒミコ‼︎

HIMIKO!!

Himiko!!

2

友だちの血を吸ったって⁉︎

ともだちのちをすったって⁉︎

tomodachi no chi wo sutta tte!?

You sucked your friend’s blood!?

3

違うの

ちがうの

chigau no

No, it’s different.

4

怪我してたからちうちうしたの

けがしてたからちうちうしたの

kega shiteta kara chiuchiu shita no

I kissed it because they were injured.

(Note: The onomatopoeia here for “kissed” also sounds like the one for “sucked.”)

5

普通じゃない‼︎

ふつうじゃない‼︎

futsuu ja nai!!

That’s not normal!!

6

まともになりたくないのか⁉︎

matomo ni naritakunai no ka!?

Don’t you want to be normal!?

(Note: This word for “normal” also means “decent, upstanding.”)

7

パパ ママ

PAPA MAMA

Papa, Mama.

8

わからないの 私わからないの

わからないの わたしわからないの

wakaranai no watashi wakaranai no

Don’t understand, I don’t understand.

9

みんな好きなノになるのガマンしてるの?

みんなすきなノになるのガマンしてるの?

minna suki na NO ni naru no GAMAN shiteru no?

Is everyone restraining how they want to become the ones they like?

10

なんでみんな

nande minna

Why won’t everyone

11

ちうちうしないの?

chiuchiu shinai no?

kiss?

(Note: Again, this is that same onomatopoeia that means both “kiss” and “suck.”)

12

ああ…‼︎

aa...!!

Aah...!!

13

あ〜〜〜〜〜〜〜

a~~~~~~~

Aaaaaaaaah!

14

違うんだこれ

ちがうんだこれ

chigaunda kore

This is so wrong.

15

もう根っこが!

もうねっこが!

mou nekko ga!

Her core is already--!

(Note: This “core” word means literally “roots,” and it’s the same word Katsuki uses to describe what Izuku is like “at his core” in chapter 284. I also can’t remember where but I’m pretty sure someone used the same word to describe Tomura at some point this arc. Maybe Dabi too.)

16-17

人間じゃない子産んじゃった!

にんげんじゃないこうんじゃった!

ningen ja nai ko unjatta!

We went and gave birth to a child that isn’t human!

1

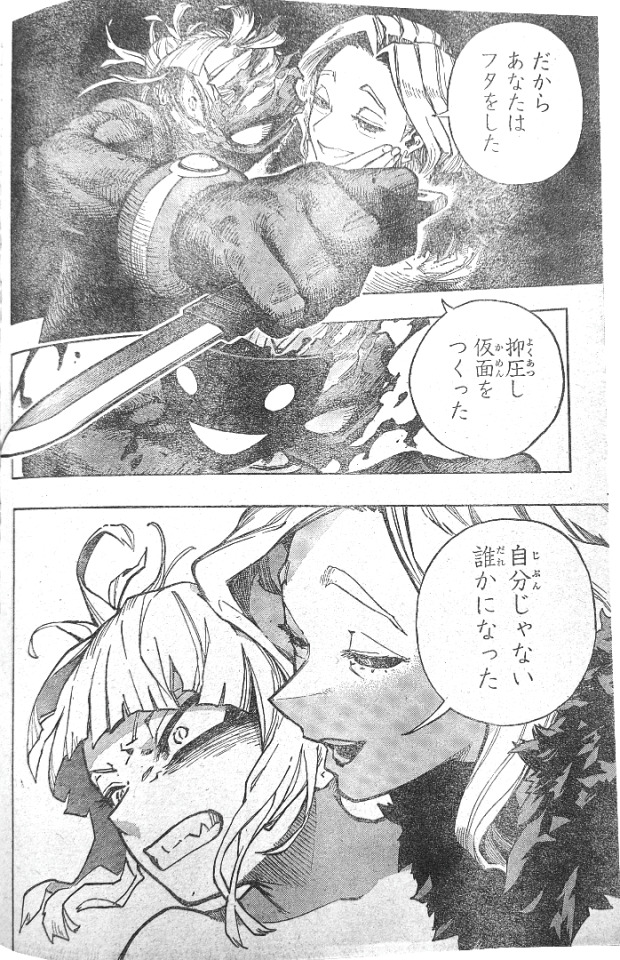

だからあなたはフタをした

dakara anata wa FUTA wo shita

“That’s why you covered it up.”

2

抑圧し仮面をつくった

よくあつしかめんをつくった

yokuatsu shi kamen wo tsukutta

“You suppressed [yourself] and made a mask.”

3

自分じゃない誰かになった

じぶんじゃないだれかになった

jibun ja nai dare ka ni natta

“You became someone other than yourself.”

1

ああ

aa

“Aagh!”

2

麗日ぁあああ‼︎

うららかぁあああ‼︎

Urarakaaaaa!!

“Urarakaaaaa!!“

3

梅雨ちゃん!

つゆちゃん!

Tsuyu-chan!

“Tsuyu-chan!“

1

ケロ!

KERO!

“Ribbit!”

2

違うそっちじゃな

ちがうそっちじゃな

chigau socchi ja na

“No, not over there!”

3

え

e

“Eh?”

4

ゲゴッ

GEGO

“Ribbi-cough!”

5

トガだ!

TOGA da!

“That’s Toga!”

6-7

ヒーローは殲滅する

ヒーローはせんめつする

HIIROO wa senmetsu suru

“Annihilate the heroes!”

8

飛び散った血を分身が摂取してるんだ!

とびちったちをぶんしんがせっしゅしてるんだ!

tobichitta chi wo bunshin ga sesshu shiterunda!

“The doppelgangers are ingesting the blood that’s splattering everywhere!”

1

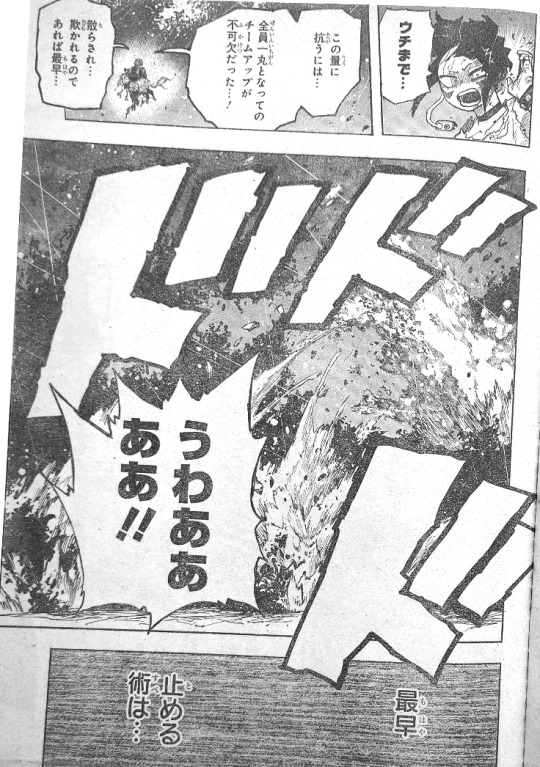

ウチまで…

UCHI made...

“Even me...”

2

この量に抗うには…

このりょうにあらがうには…

kono ryou ni aragau ni wa...

“To oppose these numbers...”

3

全員一丸となってのチームアップが不可欠だった…!

ぜんいんいちがんとなってのチームアップがふかけつだった…!

zen’in ichigan to natte no CHIIMUAPPU ga fukaketsu datta...!

“it was essential for everyone to team up all together...!”

4

散らされ…欺かれるのであれば最早…

ちらされ…あざむかれるのであればもはや…

chirasare...azamukareru node areba mohaya...

“We’ll be scattered...and deceived, so the quickest way...“

5

うわああああ‼︎

uwaaaaa!!

“Waaaaah!!”

6

最早

もはや

mohaya

The quickest way

7

止める術は…

とめるすべは…

tomeru sube wa...

to stop her is...

1

そいつを殺せ

そいつをころせ

soitsu wo korose

Kill him!

2

殲

せん

sen

Anni-

3

滅

めつ

metsu

-hilate!

4

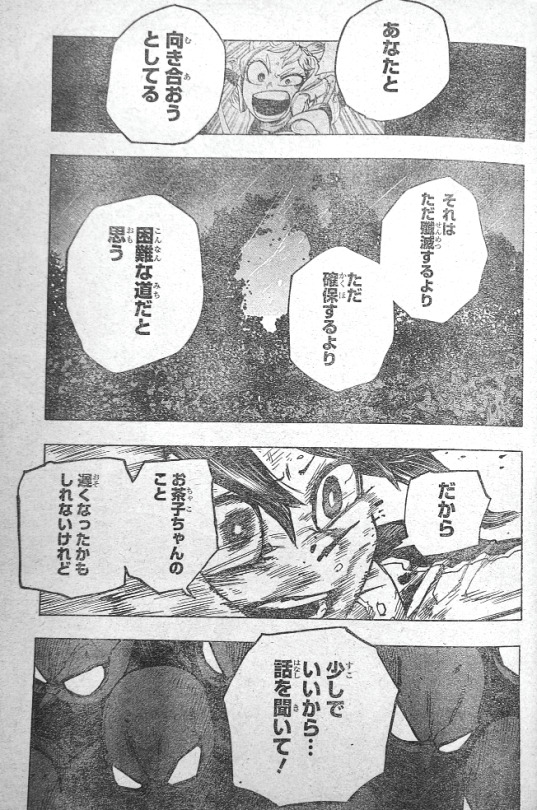

トガ…ヒミコちゃん…聞いてっ

トガ…ヒミコちゃん…きいてっ!

TOGA...HIMIKO-chan...kiite!

“Toga...Himiko-chan...listen!”

5-6

私は…!"ルール"を守ることが…

わたしは…!"ルール"をまもることが…

watashi wa...! “RUURU” wo mamoru koto ga...

“I...! [Thought that] following the rules...”

7

ヒーローだと思ってた…‼︎外れる事が…敵だと思ってた…!

ヒーローだとおもってた…‼︎はずれることが…ヴィランだとおもってた…!

HIIROO da to omotteta...!! hazureru koto ga...VIRAN da to omotteta...!

“I thought that’s what a hero is...!! I thought that deviating [from them]...is what a villain is...!”

8

でもねトガヒミコちゃん

demo ne TOGA HIMIKO-chan

“But you know, Himiko Toga-chan,”

9

私のお友だちは今

わたしのおともだちはいま

watashi no otomodachi wa ima

“my friend right now,”

10

そんなルールより何より

そんなルールよりなにより

sonna RUURU yori nani yori

“more than the rules, more than anything,”

1-2

あなたと向き合おうとしてる

あなたとむきあおうとしてる

anata to mukiaou to shiteru

“is trying to face you.”

(Note: The word here literally means “to face, oppose, face off with, confront,” but the meaning implied here is that this confrontation is not a merely physical battle but an attempt to address Toga philosophically.)

3

それはただ殲滅するより

それはただせんめつするより

sore wa tada senmetsu suru yori

“Rather than just annihilating you,”

4

ただ確保するより

ただかくほするより

tada kakuho suru yori

“rather than securing you,”

5

困難な道だと思う

こんなんなみちだとおもう

konnan na michi da to omou

“I think it’s the more difficult path.”

6

だから

dakara

“So,”

7

お茶子ちゃんのこと

おちゃこちゃんのこと

Ochako-chan no koto

“about Ochako-chan,”

8

遅くなったかもしれないけれど

おそくなったかもしれないけれど

osokunatta kamo shirenai kedo

“maybe she was late, but”

9

少しでいいから…話を聞いて!

すこしでいいから…はなしをきいて!

sukoshi de ii kara...hanashi wo kiite!

“just a little is fine...listen to what she has to say!”

1

構造が違う‼︎

こうぞうがちがう‼︎

kouzou ga chigau!!

Literal: “The structure is different!!”

Contextual: “We’re built differently!!”

2

おまえ達が言う祝福も喜びも

おまえたちがいうしゅくふくもよろこびも

omaetachi ga iu shukufuku mo yorokobi mo

“The blessings and joy you all speak of,”

1

私は何も感じない!

わたしはなにもかんじない!

watashi wa nani mo kanjinai!

“I feel none of them!”

2-3

そっちの尺度で私を可哀想な人間にするな‼︎

そっちのルールでわたしをかわいそうなにんげんにするな‼︎

socchi no RUURU (kanji: shakudo) de watashi wo kawaisou na ningen ni suruna!!

“Don’t make me a pitiable person by those rules (read as: standards)!!”

(Note: In an incredibly well-timed turn of events, this ask has become extremely relevant. The sentence above, in content and structure, resembles Twice’s narration directed at Hawks in chapter 266.)

4

そういやトガちゃんって

souiya Toga-chan tte

“Come to think of it, Toga-chan,”

5

敵名つけねえの?

ヴィランめいつけねえの?

VIRAN-mei tsukenee no?

“can’t you [use] a villain name?”

tagline

蘇る記憶…‼︎

よみがるきおく…‼︎

yomigaeru kioku...!!

A memory revives...!!

#my hero academia leak translations#mha 392#bnha 392#my hero academia manga spoilers#final showdown spoilers#himiko toga#thinly-veiled allegories for direct expressions of affection#and how japan is so painfully allergic to them#the fact that toga's affection was so repulsive to society#that society so utterly failed to teach her anything about consent#THE MESSY WEB HATH BEEN WOVEN SO INTRICATELY#THAT IS _SOME SHIT_ MY DUDES

202 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reflecting the Author

Ok, now referencing this post and, more importantly, the video behind it for a broader subject, the opening quote gets me thinking.

I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations… I much prefer history - true or feigned - with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse applicability with allegory, but the one resides in the freedom of the reader and the other in the purposed domination of the author.

-JRR Tolkien

This dovetails nicely with other opinions I have heard that trying to force a meaning on readers tends to malfunction. Along with the idea that trying to make a direct reference to current events tends to only last as long as the current events while making something more universal can reflect current events and then go on to reflect other later events as well.

The problem, I suspect is in the definition of allegory though I also suspect JRR Tolkien is right now turning over in his grave to snap at me, “Did I F*ing Stutter?”

Allegory can be the metaphorical recreation of other culturally significant stories by characters, figures, or events as a reference within a narrative, drama or picture. Aslan acts out the Christian narrative of Christ’s sacrifice. It’s not meant to be interpreted any other way. That is the purposed domination of the author as in the quote. C.S. Lewis has a specific interpretation that he wants the reader to walk away with.

But Allegory can also be the broader representation of just abstract ideas or principles by characters, figures, or events in narrative, dramatic, or pictorial form. A form put in to the story by the author without a demand for a specific interpretation.

This is one of the things I fold under the idea of MORAL. That if I make my text reflect the idea that “Power Corrupts,” then any time the real world throws up that truth - and I wouldn’t use it if I didn’t think it was true - then the story incidentally mirrors the real life events and feels more real because of that. The abstract representation and the real world events mesh to create something stronger than I feel I could create with purpose.

And here I think this may be what Tolkien might mean by applicability. That instead of trying to reproduce a unique event in metaphor, it may be a stronger tactic much of the time, to apply the lesson of the event. In the video about the ring, Power is Corruptive as a statement of principle. The internal logic of the story states that as fundamentally true and hews close to it.

One of the things I loathe about the Peter Jackson movies is that Faramir succumbs to the corruptive influence of the ring rather than being resistant as he is in the books. I get why the movies did it. Philippa Boyens has been clear that they did it to preserve dramatic tension that they didn’t think they could keep if Faramir simply helped Frodo. And it doesn’t actually contradict this principle. Faramir is corrupted by the opportunity for power, it’s just interpersonal social power, the capability to force his father’s affections by deeds, rather than a desire for rulership or military might. And that has merit and is a good discussion.

But I loathe it because it takes away one of the very few contrary sophistications of that moral. What Tolkien himself expresses is much closer to the idea that power corrupts but that also the refusal of power insulates you from corruption in an unequal way. You may still get power thrust upon you but the lack of corruption makes it possible then to be a “good” wielder of power. Tolkien shows over and over again that those who wish power the least are the most effective at wielding it.

That’s not terribly controversial. But Tolkien goes the extra mile with it, particularly with Faramir, changing it from a vague moral based on a general truism to something he actually personally believes. And I think that’s a fair part of Tolkien’s authorial power. Tolkien is a monarchist, he did believe in the concept of the good king and what made one, which means the application of his ideals ring true not only in the work but also as applied to the real world. It’s fairly difficult to work oneself around from reading about Faramir and Aragorn to the idea that the very idea of monarchical power is bad.

Which I think is the other element: the more you, as the author, buy it, the more you, as the author, delve into the idea to the spaces where you do not share the general opinion, the more polished your reflection will be because it is brightened by specific application.

I can see this in my own work. One of my constant struggles is getting into the morality of my character JJ. I love JJ. AND I am under no delusions that she is a good person. JJ was originally designed to be a monster and she is. So, the question becomes, what do I say morally about her. And I feel that the application, the reflection that peers deepest into me, even where I am very uncomfortable, so that it will reflect brightest to others is putting in my own actual attitude toward her. That she is awful AND she gets away with it. JJ doesn’t get punished. JJ isn’t defeated. JJ gets loved, treated like a hero, and vindicated. Which I honestly feel guilty about. And would not want expressed as a moral, little m. I dislike that monsters just get away with it. That they might even succeed because of it. But that statement also feels true. And by looking at how she gets pardoned that to me gives a greater reflection of who we are if not who we would like us to be. It also generally means that what I produce will not look like what someone else produces because I’m not quite falling in line with either usual camp.

And for many others, who might be trying to depict thinly veiled political leaders, that deep dive might be better reflective for you as well. I am definitely not saying to excuse them in your work. But by getting deep into where you are uncomfortably comfortable with how they run things if it were somebody else and by getting deep into where you might be uncomfortably comfortable with how their opposition acts, even though it might not be exactly that political leader, it might end up reading as many more and reflecting better how you view it all.

The point, I think, is that by delving deep into what you personally deeply feel, good or bad or both, you’ll generate something much more resonant than you will by taking the prepackaged allegory of someone else’s story that most people might already have made their moral decision on.

It’s a thought anyway. Or at least a ramble.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brodsky, Brodsky Everywhere

It may seem strange that Seamus Heaney addressed but one poem to his lover, Joseph Brodsky — and even then, he did so only after the latter's death. Some people might even leap to the conclusion that this is proof of the insignificance of their relationship. But the more observant reader will realise that Brodsky permeates the entirety of Heaney's poetic work from their first meeting in 1972 onwards, superficially hidden in a wealth of allegory, symbolism and thinly veiled figurative language. Let us explore, then, the tip of that iceberg.

We have already noted the prevalence of birds in Heaney's poems, as well as their significance as a representation of sexual freedom, constantly longed for and occasionally attained. Not infrequently, they are also imbued with a more direct allegorical meaning; an example of this would be The Blackbird of Glanmore, in which the titular blackbird stands in for Brodsky. Heaney's love of the blackbird is contrasted with his neighbour — representing society at large — stating: "I never liked yon bird." The bird is linked with death, especially with that of Heaney's younger brother, who was killed in an accident at the age of four — this is because the poem was written several years after Brodsky passed away, and in Heaney's mind the two deaths that affected him the most are merged as one. The unusual description of the blackbird's personality — "your ready talkback,/Your each stand-offish comeback" — is perfectly consistent with that of Brodsky, who was sent to a Soviet prison camp after a cheeky remark to a judge.1

With this allegorical insertion of Brodsky as a blackbird, it is difficult not to make the connection between this poem and the earlier St Kevin and the Blackbird, in which a blackbird nests in St. Kevin's palm, forcing him to remain still for weeks until the eggs hatch. If we reasonably assume that the blackbird represents Brodsky once again, then it is logical to observe that Heaney is St. Kevin. Brodsky's appearance into his life links Heaney "Into the network of eternal life," which also justifies the presence of "love's deep river". Until their love fledges, Heaney is filled with a mixture of self-forgetfulness and pain; while the beginnings of any love can be fraught with uncertainty and difficulty, it is clear that the queer nature of the relationship in question left Heaney agonising over its implications to an exceptional extent. As we will see again, Heaney's acceptance of his own sexual identity came slowly and hesitantly, and the first stages of his journey of self-discovery were full of fear and suffering.

The blackbird as a symbol for Brodsky crops up in several other poems. The "perfect eye of the nesting blackbird" in Field Work represents the ability to see the hidden truth about Heaney's sexuality. The "dart and dab" of blackbirds around the scribe in Alphabets symbolises Brodsky's role in Heaney's attainment of wisdom and self-understanding. The "young priest, glossy as a blackbird" of Station Island shows Heaney's reconciliation of his sexual identity and his religious beliefs. We also see the bird in the poem Drifting Off, in which many different species of the avian family are described and personified. I speculated before that each bird is meant to represent a different person, which I consider still plausible — it makes sense that Heaney "overrated the composure of blackbirds," since he managed to connect with Brodsky at a deeper lever than the latter's typical outward harshness — but I now suspect that each bird sybolises a different element of Brodsky's personality. Analysing the poem in the view of this idea would be productive, but this blessay is not the place for such an in-depth piece of work. A quick read of the poem, however, should make it apparent that each of the traits describes adds up to a cohesive whole, accounting for the various facets of character — both the good and the bad.

After interpreting all these birds as representing Brodsky, a wider interpretation of Heaney's figurative approach leads us to consider other animals as allegorical characters. The sexualisation of the badger in Badgers — "The unquestionable houseboy’s shoulders/that could have been my own" — and the similar treatment of The Otter — "I loved your wet head and smashing crawl,/Your fine swimmer’s back and shoulders" — are both clear expressions of queer love. The voyeuristic observation in The Skunk leaves no doubts to Heaney's true intentions. The communion-as-gay-sexual-union of the titillating Oysters is about as subtle as an elephant with an airhorn:

My tongue was a filling estuary,

My palate hung with starlight:

As I tasted the salty Pleiades

Orion dipped his foot into the water.

Alive and violated

They lay on their beds of ice

If we decide to include one of the most common queer symbols — flowers, which may not be animals, but are nonetheless alive — we can add Heaney's "erotic mayflowers" in Bone Dreams; his soul weeping as he touches the violets in His Dawn Vision; the "pined-for" orchid in After a Killing; the "Lupin spires, erotics of the future" of Lupins; the plainly sexual "high stream-roof that moved in silence over/Rhododendrons in full bloom" in The Walk; the phallic "comet’s pulsing rose" of Exposure... I could keep going, but anyone who finds the mountain of evidence presented here insufficient is clearly blinded by prejudice and will categorically refuse to see reason, so it is futile to continue.

It is impossible to fail to notice that Brodsky became the focal point of Heaney's poetic output after their love-at-first-sight meeting, and that he is present — more or less conspicuously — in almost every one of his poems. I have presented here but a small selection of examples, and I have no doubt missed some important symbols in my research, yet what we have already is overwhelming — and I still have to apologise for the insufficient time and effort put into this exposé, because in truth, every poem mentioned here in passing warrants at the very least its own paragraph, and most should be accorded their own blessay. This relentless torrent of Brodskian allegory is a testament to the fact that Heaney's œuvre is, in essence, one massive — elaborate — intricate — mammoth monument of queer love.

For more information about the incident, see here. ↩︎

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I am Made of Love and It’s Stronger than You”: Steven Universe and Alternative Models of Queer Resistance in Science-Fiction.

I needed to motivate myself because I have been working on this for ages - so here, have the prospectus to my M.A thesis. Maybe you’re interested in talking about it, or reading more as the thesis is being developed?

How do we resist oppression? Even before the emergence of queer theory as an academic discipline, authors and activists alike have wondered how the persistent structures of hegemonic discourse can be opposed. Aside from important endeavours to organise and dismantle political ideology and its effect on the material world, fiction is slowly recognised as a possible tool for queer resistance. By representing marginalised groups and opening discussions about different kinds of subjectivity, fiction provides new frameworks for dreaming queer revolution. Stressing the importance of conjuring imaginative scenarios to explore societal issues, it is no surprise that the genre of Science-Fiction has risen to the challenge. Its visions of both utopian and dystopian futures speculate upon how issues of marginalisation might be dealt with going forward and is therefore meaningfully engaging with the Other.

A particularly interesting outlet for social commentary is constituted in the figure of the alien. By taking the concept of the outsider to its most literal meaning, Science Fiction is able to extricate itself from reality and use imaginary cultures to draw parallels to our own world. In some texts, the alien is meant to incite the Freudian concept of the uncanny. The relative proximity to humanity is here meant to signify cultural lines and warn the audience against transgression. In other works, the distance between human and alien is reduced further, until a certain level of identification with the strange Other is reached. This strategy is most often employed to show the alien as a bringer of progress and incite positive change in how the audience sees what it cannot understand. Due to the multiplicity of the alien’s symbolic meaning, utilising the concept to interrogate the nature of gender identity and sexual desire has been proven quite fruitful. From feminist utopias where all men go extinct to allegories of same-sex relationships, extra-terrestrial characters are useful metaphors to discern how we view queerness. More than this, the ways in which queerness is constituted in alien cultures, technologies and biologies can be utilised to point towards strategies to free marginalised groups from oppression. One recent work of Science Fiction stands out in its attempt to interrogate the nature of queerness and rebellion by employing the alien as a symbol for human society: The Cartoon Network’s children’s program Steven Universe. My paper will examine how Steven Universe reflects on queerness through alien characters and, furthermore, offers a unique model of radical empathy as a viable way to resist oppressive structures.

Steven Universe has proven to be undeniably relevant to queer discourse. The show received the Media Award for Outstanding Kids and Family Programming by the GLAAD Organisation (Gay and Lesbian Association against Defamation) in 2019 and wrote history by depicting the first on-screen queer kiss in a children’s animated program. Steven Universe focusses on its titular character, Steven, a young alien/human hybrid who learns to control his supernatural powers under the guidance of his four alien surrogate mothers: Garnet, Amethyst and Pearl. The heart of the show is constituted in Steven’s engagement with the society, biology and history of his alien heritage, an extra-terrestrial species called the Gems. Throughout the show, the plot reveals a legacy of oppression and war, with the gem’s homeworld representing imperial and fascist ideology against which his late mother has rebelled. As the story continues, Steven must realise that the ancient war his mother battled against her home planet merely resulted in a stand-still and that it is his duty to find ways for resistance.

In order to see how Steven Universe uses the alien in relation to queer identity, my paper will first reflect on how queerness is represented within the show. Although the nature of queerness is notoriously hard to articulate, it will be necessary to outline the terminology and specify how the concept is used for my specific purpose. Queerness defines itself exactly through its breaking of boundaries and blurring of conventional lines, it pertains -most commonly- to matters of sexuality, identity, gender and desire: “Broadly speaking, queer describes those gestures or analytical models which dramatize incoherencies in the allegedly stable relations between chromosomal sex, gender and sexual desire. Resisting that model or stability –which claims heterosexuality as its origin, when it is more properly its effect –queer focuses on mismatches between sex, gender and desire.” (Jagose 3). In other words, I will use queerness as a direct opposition to the hegemonic discourse, which demands stable and unchanging categories of gender, sexuality and their expressions. These demands are rooted in normative assumptions about the naturalness of heterosexuality[M3] and rigid ideas about gender roles. Defining these boundaries, will furthermore be achieved by looking at Simone de Beavoirs The Second Sex and Judith Butler’s analysis on the performative nature of gender.

Using these definitions reveals the usefulness of Steven Universe in queer context. One outstanding detail is the fact that all gems, Steven himself excluded, are female presenting to human audiences, yet their internal gender identity remains ambiguous. Gems reproduce asexually, having no need for biological sex (or even gender) and are often even unable to grasp the concept itself. Their presentation as female is shown to be an unquestioned default, putting the dominant assumption of neutral masculinity into question. Characters like Amethyst, are shown to explore their gender on a deeper level, occasionally taking on masculine alter egos and preferring male pronouns while presenting this way. Steven himself is positioned in opposition to general notions of hegemonic masculinity. His weapons are defensive, his powers involve healing, and his design is dominated by soft shapes and the colour pink. More than that, Steven is empathetic, gentle, and shown to enjoy stereotypically feminine activities such as wearing dresses and planning weddings. His close connection to the figure of the mother queers him in more ways than one. Besides this being an unusual feature of a male-centred storyline, the asexual nature of the Gems negates his gender identity. Strangers to reproduction, the enemies mistake Steven for his mother, misgendering him and drawing direct parallels to lived experiences of transgender people. His fight against their oppressive regime is ultimately similar to the struggles of transgender people, who are fighting for recognition of their identities.

This explicit disconnection between sex and gender also means that various romances formed between main characters are visually presented as lesbian relationships, while simultaneously putting the essentialist nature of gender into question. Complex romances are put to the forefront, meant to interrogate issues of prejudice, authenticity and power relations. The character Pearl, formerly a servant of Steven’s mother, rebels against her home planet out of romantic affection for her master. The narrative presents the death of Steven’s mother as a traumatic event and invites questions of how her queer identity interacted with her liberation. On the one hand, “lesbian” affection was the cause for Pearl joining the rebellion, yet she is unable to shed her subservience to Steven’s mother. The narrative criticises her loss of self-worth, rooted in ideological indoctrination as much as romantic dependence.

Connecting multiple issues of gender and sexuality, the alien biology of the gems is infused with inherent queerness. Steven Universe’s alien race has a mechanism to question fixed identity itself: Fusion. Here, two gems perform a dancing routine to synchronise with each other until they fuse to form a new entity altogether. Most often employed as a strategy to gain strength in battle, fusion is also shown to be a deeply intimate and emotional matter. The resulting character is physically and mentally an amalgam of the two (or more Gems) who created them. In this way, fusion functions as an exploration of identity and relationships, deeply queer in matters of gender and sexual desire. One fusion particularly stands out when analysing gender fluidity: The fusion of Stevonnie comes into existence when Steven, and his best friend Connie fuse. Stevonnie is explicitly stated and shown to be nonbinary and intersex. They are capable, relatable and even shown to be desirable in the eyes of other characters. The fact that Steven and Connie break with gender conventions by switching masculine and feminine roles, makes analysing Stevonnie all the more fruitful. Stevonnie is also far from the only nonbinary fusion of the show. Throughout the seasons, Steven fuses with multiple gems, resulting in an array of nonbinary characters of vastly different gender representations and pronouns.

The show’s revolutionary approach is reinforced by the fact that the gem’s planet, simply called Homeworld, practically operates under a fascist dictatorship. Its society is made up of different types of gems, created for distinct purposes they are meant to fulfil without question. Remarkably, Homeworld explicitly forbids fusion between two different types of gems. Overstepping this line is not only cause for scandal but punishable by death. The show presents this as a thinly veiled allegory for the oppressed nature of LGBT relationships in the real world. In relation to that, the show examines themes of queer oppression and queer resistance in the character of Garnet. Garnet is a permanently fused gem, made up of Ruby and Sapphire who chose to rebel against Homeworld. Their romantic relationship is not weakened by its metaphorical nature, as Ruby and Sapphire’s visual resemblance to women is a constant reminder of its queerness.

As the show progresses, Steven is forced to confront Homeworld and decide upon strategies for liberation. Here, the show is ambivalent towards the usage of physical force. On the one hand, the war for independence fought by the rebellion five thousand years ago, is shown to have been effective in fighting against Homeworld’s armies. However, it also wiped out nearly all the rebellious gems and has ultimately only achieved a temporary peace. Contrarily, Steven’s innate empathy and deep desire to engage with whom he opposes is presented as inciting long-lasting change. Not only pertaining to his personality, but also encoded in his alien biology, Steven has the power to feel the emotions of his enemies. As he recognises physical force as inevitable in some instances, the real shift always occurs due to him trying to understand his opponents on an emotional level. The show hereby raises the complicated question of how to consolidate liberation and a need to cease the perpetuation of violence, offering radical empathy as a possible solution. Radical empathy, as the idea to resist oppression through understanding, is negating the more masculine realm of physical fight. Using a male character to introduce this idea, is already marked as queer. Nevertheless, radical empathy is also a contested subject and it will be necessary to evaluate how Steven Universe answers to the possibility of its ineffectiveness in queer liberation discourse. For this purpose, I will employ, among others, Jack Halberstam’s theories on Queer Violence in media and Lee Edelman’s No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Both will be used to examine whether the progressive politics of Steven Universe can truly be used as an advocate for queer resistance, or if they promote liberalism and complacency.

In conclusion, my paper will examine how the concept of the alien is shown to be queer in Steven Universe, and how alien society is utilised as a metaphor for real-world queer discourse. It will further attempt to outline the different models of resistance brought forth by the show and address criticism towards its compliance with systemic injustice and accusations of demonising more violent forms of revolution.

Bibliography: (Preliminary)

Primary Texts:

Steven Universe. Cartoon Network. 2013-2019.

Secondary Texts:

Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. New York: Vintage Books 1989, c1952. Print.

Butler, Judith. Undoing Gender. New York: Routledge, 2004.

Dunn, Eli. “Steven Universe, Fusion Magic, and the Queer Cartoon Carnivalesque.” Gender Forum: An Internet Journal of Gender Studies, vol. 56, 2016, pp. 44–57.

Edelman, Lee. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. , 2004. Print.

Jagose, Annamarie. Queer Theory: An Introduction. New York: New York University Press, 1996. Print.

Halberstam, Judith. “Imagined Violence/Queer Violence: Representation, Rage, and Resistance.” Social Text, no. 37, 1993, pp. 187–201.

Hollinger, Veronica. “(Re)Reading Queerly: Science Fiction, Feminism, and the Defamiliarization of Gender.” Science Fiction Studies, vol. 26, no. 1 [77], Mar. 1999, pp. 23–40.

Lothian, Alexis. “Feminist and Queer Science Fiction in America.” The Cambridge Companion to American Science Fiction, edited by Eric Carl Link and Gerry Canavan, Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp. 70–82.

Melzer, Patricia. Alien Constructions: Science Fiction and Feminist Thought. University of Texas Press, 2006.

Merrick, Helen. “Gender in Science Fiction.” The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction, edited by Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn, Cambridge University Press, 2003, pp. 241–252.

Moore, Mandy Elizabeth "Future Visions: Queer Utopia in Steven Universe," Research on Diversity in Youth Literature: 2.1, 2019.

Pawlak, Wendy Sue. “The Spaces between: Non-Binary Representations of Gender in Twentieth-Century American Film.” Dissertation Abstracts International, vol. 73, no. 11, U of ArizonaProQuest, May 2013.

Pearson, Wendy Gay. “Queer Theory.” The Routledge Companion to Science Fiction, edited by Mark Bould et al., Routledge, 2009, pp. 298–307.

Pearson, Wendy Gay. “Science Fiction and Queer Theory” Published as a book chapter in: The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction. Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn. (Eds.), 2003. Pp. 149-160.

Roqueta Fernandez, Marta “Posthumanism and the creation of racialised, queer identities and sexualities: An analysis of ‘Steven Universe’” Monográfico: Nuevas Amazonas, 2.7, 2019. Pp. 48-84.

Thomas, Misty. “‘I am a Conversation’: Media Literacy, Queer Pedagogy, and Steven Universe in College Curriculum”. Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy, 6.3, 2019.

Valentin, Al. “Using the Animator’s Tools to Dismantle the Master’s House? Gender, Race, Sexuality and Disability in Cartoon Network’s Adventure Time and Steven Universe.” Buffy to Batgirl: Essays on Female Power, Evolving Femininity and Gender Roles in Science Fiction and Fantasy, edited by Julie M. Still et al., McFarland & Company Publishing, 2019, pp. 175–215.

#Steven universe#su#steven universe meta#su analysis#academia#thesis#media analysis#steven universe analysis#long post

4 notes

·

View notes