#the way the narrative frames those things is inherently different even if the reader already knows

Text

Reparative Reading

I would love, and indeed have been meaning for a long time, to talk about a piece of academic writing from one of my favourite theorists that I think has an ongoing relevance. This is Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading,” first published in the mid-to-late 1990’s and compiled in her 2003 monograph, Touching Feeling. There’s a some free PDFs of it floating around (such as here) for those who want to read it in full – and I would recommend doing so, despite its density in places, because Sedgwick has a marvelous critical voice.

Sedgwick’s topic of contention in this essay is the overwhelming tendency in queer criticism to employ what she thinks of as a paranoid methodology – that is, criticism based around the revelation of oppressive attitudes, and that sees that revelation not only as always and inherently a radical project, but the only possible anti-oppressive project. This methodology is closely related to what Paul Ricoeur termed the “hermeneutics of suspicion” and identified as central to the works of Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud, which were all progenitors of queer criticism. Sedgwick objects to the fact that the hermeneutics of suspicion had, at her time of writing, become “synonymous with criticism itself,” rather than merely one possible critical approach. She questions the universal utility of the dramatic unveiling of the presence of oppressive forces, pointing to the function of visibility itself in perpetuating systemic violence, and identifying the work of anti-oppression as one based in a competition for a certain type of visibility. She also rejects the knowledge of the presence of oppression alone as conferring a particular critical imperative, instead posing the question, “what does knowledge do?”

As an example, Sedgwick critiques Judith Butler’s commentary on drag in Gender Trouble, one of the works that she uses as an example of a reading based in a paranoid approach. She identifies Butler’s argument that drag foregrounds the constructed aspect of gender as a paranoid approach, due to its focus on revelation of structures of power and oppression, and she finds Butler’s argument lacking in its neglect in acknowledging the role that joy and community formation play in the phenomenon of drag. Near the end of the essay, she also does an example of a reparative reading of the ending of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, claiming that the narrator’s remove from the traditional familial structure and its temporality is precisely what confers his particular moment joy and insight upon discovering that his friends have aged. Broadly, Sedgwick rejects the implication that readings based in joy, hope, or optimism are naïve, uncritical, or functionally a denial of the reality of oppression.

Now, it’s important to note that the message of this essay is not that paranoid readings are bad, and reparative readings are good. Sedgwick is drawing on a body of affect theories (most prominently Melanie Klein’s) that posit the reparative impulse as dependent on and resulting from the paranoid impulse – reparation by definition is something that can only occur after some kind of shattering, and Kleinian trauma theories generally posit that process as something that produces a new object or perspective than pre-trauma. (Something I love about Sedgwick is that she often sets up these binaries that seem at odds with each other, but end up being mutually dependent.) Furthermore, the critical tradition in queer studies that Sedgwick is critiquing in this essay is one that was itself, in many ways, a manifestation of communal trauma, particularly with the impact of the AIDS crisis. Sedgwick herself acknowledged this last point in a later essay, “Melanie Klein and the Difference Affect Makes,” claiming that she didn’t feel she did a good enough job of identifying the AIDS crisis as a driving force behind this trend. So Sedgwick is not discounting the utility of paranoid readings, but rather rejecting the notion that they ought to encompass all of criticism. (In fact, a running theme in Touching Feeling is her representation of various perspectives and methods as sitting beside one another, rather than hierarchically.) And reparative reading, as Sedgwick portrays it, is not the denial of trauma or violence, but a possibility for moving forward in its wake.

Why am I taking the time to outline all of this? Because, while the original essay was written almost 25 years ago, with the academic community in mind, it reflects a similar pattern that I see now in online fandom.

Queer fandom (as that’s what I feel the most qualified to talk about) has a considerable paranoia problem. Queer fandom is brimming with traumatized people who carry varying degrees of personal baggage and are afflicted by the general neuroses that come from existing in a heterosexist, cissexist society. And many people in fandom have been repeatedly burned by the treatment of queer people in media – Bury Your Gays, queerbaiting, queercoded villains, etc. And in such a media landscape, and within such a communal sphere, much of fandom has developed the kind of “anticipatory and reactive” method of media criticism that Sedgwick identifies in this essay.

Fandom gets very excited for new media, certainly, and is prone to adulation of media that seems to fit its ideological beliefs. But it is also very quick to hone in on any potential representative flaw, and use that as a vehicle for condemnation. (This cycling between idealization and extreme, bitter jadedness has been widely commented on). Not only is there a widespread moralistic approach in fan criticism that is very invested in deeming whether or not a piece of media is harmful or not, “problematic” or not, within a simplistic binary framing, but that conclusion is so frequently the end of the conversation. “This is problematic,” “this is bad representation,” “this falls into this tired and harmful trope,” etc, is treated as the endpoint of criticism, rather than a starting point. This is the spectacle of exposure that Sedgwick critiques as central to the paranoid approach – simply identifying the presence of oppressive attitudes in a text is not only treated as an analytic in and of itself, but as the only valid analytic. So often I have seen people jump to take the most pessimistic possible approach to a piece of media, and then proceed to treat any disagreement with that reading as in and of itself a denial of structural homophobia, as naïve, and as not being a critical enough reader/viewer. “Being critical” itself has been taken on as a shorthand for this particular process, which many others have commented on as well.

Now, again, I want to stress that taking issue with this totalizing impulse is not discounting the legitimate uses of identification and exposure, or even of reactivity and condemnation. There are particular contexts in which these responses have their uses – in Sedgwick’s words, “paranoia knows some things well and others poorly.” But that approach has a finite scope. And rejecting the universal application of this particular analytic does not itself constitute a denial of the existence of oppression, or its manifestation in media and narratives. Nor is it about letting particular works “off the hook” for whatever aspects they may have that are worthy of critique. Rather, it’s a call to acknowledge that other critical approaches exist, and that the employment of a more optimistic approach is not necessarily a result of ignorance or apathy about the existence of oppression. It is one that invites us not to lay aside paranoia as an approach, but recognize that it has limited applicability, and question when and how our motives might be better served by another approach.

I think that “is this homophobic, yes or no?” or “is this good representation, yes or no?” are reductive critical approaches in and of themselves. But I think there’s also room for acknowledgment that not everything needs to be read through a revelatory lens regarding societal oppression at all. Rather than “what societal attitudes does this reflect back?” being the approach, I think there could be a good bit more “What does this do for us? What avenues of possibility does this have?” I think there’s already been leanings in this direction with, for example, the reclaiming of queercoded villains, with dialogues that treat those characters not as reflections of societal anxiety and prejudice, but rather as representative of joy and freedom and possibility in their rejection of norms and constraints. I’d like to see that approach applied more broadly and more often.

Let’s try to read more reparatively.

#alpha speaks#alpha's literary opinions#eve sedgwick#literary criticism#queer studies#help me sedgwick#also apparently 'reparatively' isn't actually a word but sedgwick invented words in a similar way all the time so#lord i hope this is all coherent...#these concepts are always more complicated and harder to convey than they seem#my meta#big sigh.#queue#for pillowfort#(when it comes back online)

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bakudeku: A Non-Comprehensive Dissection of the Exploitation of Working Bodies, the Murder of Annoying Children, and a Rivals-to-Lovers Complex

I. Bakudeku in Canon, And Why Anti’s Need to Calm the Fuck Down

II. Power is Power: the Brain-Melting Process of Normalization and Toxic Masculinity

III. How to Kill Middle Schoolers, and Why We Should

IV. Parallels in Abuse, EnemiesRivals-to-Lovers, and the Necessity of Redemption ft. ATLA’s Zuko

V. Give it to Me Straight. It’s Homophobic.

VI. Love in Perspective, from the East v. West

VII. Stuck in the Sludge, the Past, and Season One

Disclaimer

It needs to be said that there is definitely a place for disagreement, discourse, debate, and analysis: that is a sign of an active fandom that’s heavily invested, and not inherently a bad thing at all. Considering the amount of source material we do have (from the manga, to the anime, to the movies, to the light novels, to the official art), there are going to be warring interpretations, and that’s inevitable.

I started watching and reading MHA pretty recently, and just got into the fandom. I was weary for a reason, and honestly, based on what I’ve seen, I’m still weary now. I’ve seen a lot of anti posts, and these are basically my thoughts. This entire thing is in no way comprehensive, and it’s my own opinion, so take it with a grain of salt. If I wanted to be thorough about this, I would’ve included manga panels, excerpts from the light novel, shots from the anime, links to other posts/essays/metas that have inspired this, etc. but I’m tired and not about that life right now, so, this is what it is. This is poorly organized, but maybe I’ll return to fix it.

Let’s begin.

Bakudeku in Canon, And Why Anti’s Need to Calm the Fuck Down

There are a lot of different reasons, that can be trivial as you like, to ship or not to ship two (or more) characters. It could be based purely off of character design, proximity, aversion to another ship, or hypotheticals. And I do think that it’s totally valid if someone dislikes the ship or can’t get on board with his character because to them, it does come across as abuse, and the implications make them uncomfortable or, or it just feels unhealthy. If that is your takeaway, and you are going to stick to your guns, the more power to you.

But Bakudeku’s relationship has canonically progressed to the point where it’s not the emotionally (or physically) abusive clusterfuck some people portray it to be, and it’s cheap to assume that it would be, based off of their characterizations as middle schoolers. Izuku intentionally opens the story as a naive little kid who views the lens of the Hero society through rose colored glasses and arguably wants nothing more than assimilation into that society; Bakugou is a privileged little snot who embodies the worst and most hypocritical beliefs of this system. Both of them are intentionally proven wrong. Both are brainwashed, as many little children are, by the propaganda and societal norms that they are exposed to. Both of their arcs include unlearning crucial aspects of the Hero ideology in order to become true heroes.

I will personally never simp for Bakugou because for the longest time, I couldn't help but think of him as a little kid on the playground screaming at the top of his lungs because someone else is on the swingset. He’s red in the face, there are probably veins popping out of his neck, he’s losing it. It’s easy to see why people would prefer Tododeku to Bakudeku.

Even now, seeing him differently, I still personally wouldn’t date Bakugou, especially if I had other options. Why? I probably wouldn’t want to date any of the guys who bullied me, especially because I think that schoolyard bullying, even in middle school, affected me largely in a negative way and created a lot of complexes I’m still trying to work through. I haven’t built a better relationship with them, and I’m not obligated to. Still, I associate them with the kind of soft trauma that they inflicted upon me, and while to them it was probably impersonal, to me, it was an intimate sort of attack that still affects me. That being said, that is me. Those are my personal experiences, and while they could undoubtedly influence how I interpret relationships, I do not want to project and hinder my own interpretation of Deku.

The reality is that Deku himself has an innate understanding of Bakugou that no one else does; I mention later that he seems to understand his language, implicitly, and I do stand by that. He understands what it is he’s actually trying to say, often why he’s saying it, and while others may see him as wimpy or unable to stand up for himself, that’s simply not true. Part of Deku’s characterization is that he is uncommonly observant and empathetic; I’m not denying that Bakugou caused harm or inflicted damage, but infantilizing Deku and preaching about trauma that’s not backed by canon and then assuming random people online excuse abuse is just...the leap of leaps, and an actual toxic thing to do. I’ve read fan works where Bakugou is a bully, and that’s all, and has caused an intimate degree of emotional, mental, and physical insecurity from their middle school years that prevents their relationship from changing, and that’s for the better. I’m not going to argue and say that it’s not an interesting take, or not valid, or has no basis, because it does. Its basis is the character that Bakugou was in middle school, and the person he was when he entered UA.

Not only is Bakugou — the current Bakugou, the one who has accumulated memories and experiences and development — not the same person he was at the beginning of the story, but Deku is not the same person, either. Maybe who they are fundamentally, at their core, stays the same, but at the beginning and end of any story, or even their arcs within the story, the point is that characters will undergo change, and that the reader will gain perspective.

“You wanna be a hero so bad? I’ve got a time-saving idea for you. If you think you’ll have a quirk in your next life...go take a swan dive off the roof!”

Yes. That is a horrible thing to tell someone, even if you are a child, even if you don’t understand the implications, even if you don’t mean what it is you are saying. Had someone told me that in middle school, especially given our history and the context of our interactions, I don’t know if I would ever have forgiven them.

Here’s the thing: I’m not Deku. Neither is anyone reading this. Deku is a fictional character, and everyone we know about him is extrapolated from source material, and his response to this event follows:

“Idiot! If I really jumped, you’d be charged with bullying me into suicide! Think before you speak!”

I think it’s unfair to apply our own projections as a universal rather than an interpersonal interpretation; that’s not to say that the interpretation of Bakudeku being abusive or having unbalanced power dynamics isn’t valid, or unfounded, but rather it’s not a universal interpretation, and it’s not canon. Deku is much more of a verbal thinker; in comparison, Bakugou is a visual one, at least in the format of the manga, and as such, we get various panels demonstrating his guilt, and how deep it runs. His dialogue and rapport with Deku has undeniably shifted, and it’s very clear that the way they treat each other has changed from when they were younger. Part of Bakugou’s growth is him gaining self awareness, and eventually, the strength to wield that. He knows what a fucked up little kid he was, and he carries the weight of that.

“At that moment, there were no thoughts in my head. My body just moved on its own.”

There’s a part of me that really, really disliked Bakugou going into it, partially because of what I’d seen and what I’d heard from a limited, outside perspective. I felt like Bakugou embodied the toxic masculinity (and to an extent, I still believe that) and if he won in some way, that felt like the patriarchy winning, so I couldn't help but want to muzzle and leash him before releasing him into the wild.

The reality, however, of his character in canon is that it isn’t very accurate to assume that he would be an abusive partner in the future, or that Midoryia has not forgiven him to some extent already, that the two do not care about each other or are singularly important, that they respect each other, or that the narrative has forgotten any of this.

Don’t mistake me for a Bakugou simp or apologist. I’m not, but while I definitely could also see Tododeku (and I have a soft spot for them, too, their dynamic is totally different and unique, and Todoroki is arguably treated as the tritagonist) and I’m ambivalent about Izuocha (which is written as cannoncially romantic) I do believe that canonically, Bakugou and Deku are framed as soulmates/character foils, Sasuke + Naruto, Kageyama + Hinata style. Their relationship is arguably the focus of the series. That’s not to undermine the importance or impact of Deku’s relationships with other characters, and theirs with him, but in terms of which one takes priority, and which one this all hinges on?

The manga is about a lot of things, yes, but if it were to be distilled into one relationship, buckle up, because it’s the Bakudeku show.

Power is Power: the Brain-Melting Process of Normalization and Toxic Masculinity

One of the ways in which the biopolitical prioritization of Quirks is exemplified within Hero society is through Quirk marriages. Endeavor partially rationalizes the abuse of his family through the creation of a child with the perfect quirk, a child who can be molded into the perfect Hero. People with powerful, or useful abilities, are ranked high on the hierarchy of power and privilege, and with a powerful ability, the more opportunities and avenues for success are available to them.

For the most part, Bakugou is a super spoiled, privileged little rich kid who is born talented but is enabled for his aggressive behavior and, as a child, cannot move past his many internalized complexes, treats his peers like shit, and gets away with it because the hero society he lives in either has this “boys will be boys” mentality, or it’s an example of the way that power, or Power, is systematically prioritized in this society. The hero system enables and fosters abusers, people who want power and publicity, and people who are genetically predisposed to have advantages over others. There are plenty of good people who believe in and participate in this system, who want to be good, and who do good, but that doesn’t change the way that the hero society is structured, the ethical ambiguity of the Hero Commission, and the way that Heroes are but pawns, idols with machine guns, used to sell merch to the public, to install faith in the government, or the current status quo, and reinforce capitalist propaganda. Even All Might, the epitome of everything a Hero should be, is drained over the years, and exists as a concept or idea, when in reality he is a hollow shell with an entire person inside, struggling to survive. Hero society is functionally dependent on illusion.

In Marxist terms: There is no truth, there is only power.

Although Bakugou does change, and I think that while he regrets his actions, what is long overdue is him verbally expressing his remorse, both to himself and Deku. One might argue that he’s tried to do it in ways that are compatible with his limited emotional range of expression, and Deku seems to understand this language implicitly.

I am of the opinion that the narrative is building up to a verbal acknowledgement, confrontation, and subsequent apology that only speaks what has gone unspoken.

That being said, Bakugou is a great example of the way that figures of authority (parents, teachers, adults) and institutions both in the real world and this fictional universe reward violent behavior while also leaving mental and emotional health — both his own and of the people Bakugou hurts — unchecked, and part of the way he lashes out at others is because he was never taught otherwise.

And by that, I’m referring to the ways that are to me, genuinely disturbing. For example, yelling at his friends is chill. But telling someone to kill themselves, even casually and without intent and then misinterpreting everything they do as a ploy to make you feel weak because you're projecting? And having no teachers stop and intervene, either because they are afraid of you or because they value the weight that your Quirk can benefit society over the safety of children? That, to me, is both real and disturbing.

Not only that, but his parents (at least, Mitsuki), respond to his outbursts with more outbursts, and while this is likely the culture of their home and I hesitate to call it abusive, I do think that it contributed to the way that he approaches things. Bakugou as a character is very complex, but I think that he is primarily an example of the way that the Hero System fails people.

I don’t think we can write off the things he’s done, especially using the line of reasoning that “He didn’t mean it that way”, because in real life, children who hurt others rarely mean it like that either, but that doesn’t change the effect it has on the people who are victimized, but to be absolutely fair, I don’t think that the majority of Bakudeku shippers, at least now, do use that line of reasoning. Most of them seem to have a handle on exactly how fucked up the Hero society is, and exactly why it fucks up the people embedded within that society.

The characters are positioned in this way for a reason, and the discoveries made and the development that these characters undergo are meant to reveal more about the fictional world — and, perhaps, our world — as the narrative progresses.

The world of the Hero society is dependent, to some degree, on biopolitics. I don’t think we have enough evidence to suggest that people with Quirks or Quirkless people place enough identity or placement within society to become equivalent to marginalized groups, exactly, but we can draw parallels to the way that Deku and by extent Quirkless people are viewed as weak, a deviation, or disabled in some way. Deviants, or non-productive bodies, are shunned for their inability to perform ideal labor. While it is suggested to Deku that he could become a police officer or pursue some other occupation to help people, he believes that he can do the most positive good as a Hero. In order to be a Hero, however, in the sense of a career, one needs to have Power.

Deviation from the norm will be punished or policed unless it is exploitable; in order to become integrated into society, a deviant must undergo a process of normalization and become a working, exploitable body. It is only through gaining power from All Might that Deku is allowed to assimilate from the margins and into the upper ranks of society; the manga and the anime give the reader enough perspective, context, and examples to allow us to critique and deconstruct the society that is solely reliant on power.

Through his societal privileges, interpersonal biases, internalized complexes, and his subsequent unlearning of these ideologies, Bakugou provides examples of the way that the system simultaneously fails and indoctrinates those who are targeted, neglected, enabled by, believe in, and participate within the system.

Bakudeku are two sides of the same coin. We are shown visually that the crucial turning point and fracture in their relationship is when Bakugou refuses to take Deku’s outstretched hand; the idea of Deku offering him help messes with his adolescent perspective in that Power creates a hierarchy that must be obeyed, and to be helped is to be weak is to be made a loser.

Largely, their character flaws in terms of understanding the hero society are defined and entangled within the concept of power. Bakugou has power, or privilege, but does not have the moral character to use it as a hero, and believes that Power, or winning, is the only way in which to view life. Izuku has a much better grasp on the way in which heroes wield power (their ideologies can, at first, be differentiated as winning vs. saving), and is a worthy successor because of this understanding, and of circumstance. However, in order to become a Hero, our hero must first gain the Power that he lacks, and learn to wield it.

As the characters change, they bridge the gaps of their character deficiencies, and are brought closer together through character parallelism.

Two sides of the same coin, an outstretched hand.

They are better together.

How to Kill Middle Schoolers, and Why We Should

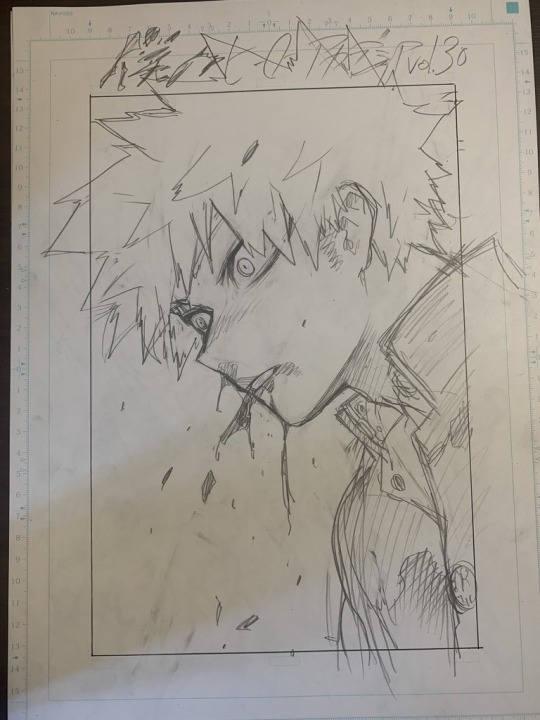

I think it’s fitting that in the manga, a critical part of Bakugou’s arc explicitly alludes to killing the middle school version of himself in order to progress into a young adult. In the alternative covers Horikoshi released, one of them was a close up of Bakugou in his middle school uniform, being stabbed/impaled, with blood rolling out of his mouth. Clearly this references the scene in which he sacrifices himself to save Deku, on a near-instinctual level.

To me, this only cements Horikoshi’s intent that middle school Bakugou must be debunked, killed, discarded, or destroyed in order for Bakugou the hero to emerge, which is why people who do actually excuse his actions or believe that those actions define him into young adulthood don’t really understand the necessity for change, because they seem to imply that he doesn’t need/cannot reach further growth, and there doesn’t need to be a separation between the Bakugou who is, at heart, volatile and repressed the angry, and the Bakugou who sacrifices himself, a hero who saves people.

Plot twist: there does need to be a difference. Further plot twist: there is a difference.

In sacrificing himself for Deku, Bakugou himself doesn't die, but the injury is fatal in the sense that it could've killed him physically and yet symbolizes the selfish, childish part of him that refused to accept Deku, himself, and the inevitability of change. In killing those selfish remnants, he could actually become the kind of hero that we the reader understand to be the true kind.

That’s why I think that a lot of the people who stress his actions as a child without acknowledging the ways he has changed, grown, and tried to fix what he has broken don’t really get it, because it was always part of his character arc to change and purposely become something different and better. If the effects of his worst and his most childish self stick with you more, and linger despite that, that’s okay. But distilling his character down to the wrong elements doesn’t get you the bare essentials; what it gets you is a skewed and shallow version of a person. If you’re okay with that version, that is also fine.

But you can’t condemn others who aren’t fine with that incomplete version, and to become enraged that others do not see him as you do is childish.

Bakugou’s change and the emphasis on that change is canon.

Parallels in Abuse, EnemiesRivals-to-Lovers, and the Necessity of Redemption ft. ATLA’s Zuko

In real life, the idea that “oh, he must bully you because he likes you” is often used as a way to brush aside or to excuse the action of bullying itself, as if a ‘secret crush’ somehow negates the effects of bullying on the victim or the inability of the bully to properly process and manifest their emotions in certain ways. It doesn’t. It often enables young boys to hurt others, and provides figures of authority to overlook the real source of schoolyard bullying or peer review. The “secret crush”, in real life, is used to undermine abuse, justify toxic masculinity, and is essentially used as a non-solution solution.

A common accusation is that Bakudeku shippers jump on the pairing because they romanticize pairing a bully and a victim together, or believe that the only way for Bakugou to atone for his past would be to date Midoryia in the future. This may be true for some people, in which case, that’s their own preference, but based on my experience and what I’ve witnessed, that’s not the case for most.

The difference being is that as these are characters, we as readers or viewers are meant to analyze them. Not to justify them, or to excuse their actions, but we are given the advantage of the outsider perspective to piece their characters together in context, understand why they are how they are, and witness them change; maybe I just haven’t been exposed to enough of the fandom, but no one (I’ve witnessed) treats the idea that “maybe Bakugou has feelings he can’t process or understand and so they manifest in aggressive and unchecked ways'' as a solution to his inability to communicate or process in a healthy way, rather it is just part of the explanation of his character, something is needs to — and is — working through. The solution to his middle school self is not the revelation of a “teehee, secret crush”, but self-reflection, remorse, and actively working to better oneself, which I do believe is canonically reflected, especially as of recently.

In canon, they are written to be partners, better together than apart, and I genuinely believe that one can like the Bakudeku dynamic not by route of romanticization but by observation.

I do think we are meant to see parallels between him and Endeavor; Endeavor is a high profile abuser who embodies the flaws and hypocrisy of the hero system. Bakugou is a schoolyard bully who emulates and internalizes the flaws of this system as a child, likely due to the structure of the society and the way that children will absorb the propaganda they are exposed to; the idea that Quirks, or power, define the inherent value of the individual, their ability to contribute to society, and subsequently their fundamental human worth. The difference between them is the fact that Endeavor is the literal adult who is fully and knowingly active within a toxic, corrupt system who forces his family to undergo a terrifying amount of trauma and abuse while facing little to no consequences because he knows that his status and the values of their society will protect him from those consequences. In other words, Endeavor is the threat of what Bakugou could have, and would have, become without intervention or genuine change.

Comparisons between characters, as parallels or foils, are tricky in that they imply but cannot confirm sameness. Having parallels with someone does not make them the same, by the way, but can serve to illustrate contrasts, or warnings. Harry Potter, for example, is meant to have obvious parallels with Tom Riddle, with similar abilities, and tragic upbringings. That doesn’t mean Harry grows up to become Lord Voldemort, but rather he helps lead a cross-generational movement to overthrow the facist regime. Harry is offered love, compassion, and friends, and does not embrace the darkness within or around him. As far as moldy old snake men are concerned, they do not deserve a redemption arc because they do not wish for one, and the truest of change only occurs when you actively try to change.

To be frank, either way, Bakugou was probably going to become a good Hero, in the sense that Endeavor is a ‘good’ Hero. Hero capitalized, as in a pro Hero, in the sense that it is a career, an occupation, and a status. Because of his strong Quirk, determination, skill, and work ethic, Bakugou would have made a good Hero. Due to his lack of character, however, he was not on the path to become a hero; defender of the weak, someone who saves people to save people, who is willing to make sacrifices detrimental to themselves, who saves people out of love.

It is necessary for him to undergo both a redemption arc and a symbolic death and rebirth in order for him to follow the path of a hero, having been inspired and prompted by Deku.

I personally don’t really like Endeavor’s little redemption arc, not because I don’t believe that people can change or that they shouldn't at least try to atone for the atrocities they have committed, but because within any narrative, a good redemption arc is important if it matters; what also matters is the context of that arc, and whether or not it was needed. For example, in ATLA, Zuko’s redemption arc is widely regarded as one of the best arcs in television history, something incredible. And it is. That shit fucks. In a good way.

It was confirmed that Azula was also going to get a redemption arc, had Volume 4 gone on as planned, and it was tentatively approached in the comics, which are considered canon. She is an undeniably bad person (who is willing to kill, threaten, exploit, and colonize), but she is also a child, and as viewers, we witness and recognize the factors that contributed to her (debatable) sociopathy, and the way that the system she was raised in failed her. Her family failed her; even Uncle Iroh, the wise mentor who helps guide Zuko to see the light, is willing to give up on her immediately, saying that she’s “crazy” and needs to be “put down”. Yes, it’s comedic, and yes, it’s pragmatic, but Azula is fourteen years old. Her mother is banished, her father is a psychopath, and her older brother, from her perspective, betrayed and abandoned her. She doesn’t have the emotional support that Zuko does; she exploits and controls her friends because it’s all she’s been taught to do; she says herself, her “own mother thought [she] was a monster; she was right, of course, but it still [hurts]”. A parent who does not believe in you, or a parent that uses you and will hurt you, is a genuine indicator of trauma.

The writers understood that both Zuko and Azula deserved redemption arcs. One was arguably further gone than the other, but that doesn’t change the fact that they are both children, products of their environment, who have the time, motive, and reason to change.

In contrast, you know who wouldn’t have deserved a redemption arc? Ozai. That simply would not have been interesting, wouldn’t have served the narrative well, and honestly, is not needed, thematically or otherwise. Am I comparing Ozai to Endeavor? Basically, yes. Fuck those guys. I don’t see a point in Endeavor’s little “I want to be a good dad now” arc, and I think that we don’t need to sympathize with characters in order to understand them or be interested in them. I want Touya/Dabi to expose his abuse, for his career to crumble, and then for him to die.

If they are not challenging the system that we the viewer are meant to question, and there is no thematic relevance to their redemption, is it even needed?

On that note, am I saying that Bakugou is the equivalent to Zuko? No, lmao. Definitely not. They are different characters with different progressions and different pressures. What I am saying is that good redemption arcs shouldn’t be handed out like candy to babies; it is the quality, rather than the quantity, that makes a redemption arc good. In terms of the commentary of the narrative, who needs a redemption arc, who is deserving, and who does it make sense to give one to?

In this case, Bakugou checks those boxes. It was always in the cards for him to change, and he has. In fact, he’s still changing.

Give it to Me Straight. It’s Homophobic.

There does seem to be an urge to obsessively gender either Bakugou or Deku, in making Deku the ultra-feminine, stereotypically hyper-sexualized “woman” of the relationship, with Bakugou becoming similarly sexualized but depicted as the hyper-masculine bodice ripper. On some level, that feels vaguely homophobic if not straight up misogynistic, in that in a gay relationship there’s an urge to compel them to conform under heteronormative stereotypes in order to be interpreted as real or functional. On one hand, I will say that in a lot of cases it feels like more of an expression of a kink, or fetishization and subsequent expression of internalized misogyny, at least, rather than a genuine exploration of the complexity and power imbalances of gender dynamics, expression, and boundaries.

That being said, I don’t think that that problematic aspect of shipping is unique to Bakudeku, or even to the fandom in general. We’ve all read fan work or see fanart of most gay ships in a similiar manner, and I think it’s a broader issue to be addressed than blaming it on a singular ship and calling it a day.

One interpretation of Bakugou’s character is his repression and the way his character functions under toxic masculinity, in a society’s egregious disregard for mental and emotional health (much like in the real world), the horrifying ways in which rage is rationalized or excused due to the concept of masculinity, and the way that characteristics that are associated with femininity — intellect, empathy, anxiety, kindness, hesitation, softness — are seen as stereotypically “weak”, and in men, traditionally emasculating. In terms of the way that the fictional universe is largely about societal priority and power dynamics between individuals and the way that extends to institutions, it’s not a total stretch to guess that gender as a construct is a relevant topic to expand on or at least keep in mind for comparison.

I think that the way in which characters are gendered and the extent to which that is a result of invasive heteronormativity and fetishization is a really important conversation to have, but using it as a case-by-case evolution of a ship used to condemn people isn’t conductive, and at that point, it’s treated as less of a real concern but an issue narrowly weaponised.

Love in Perspective, from the East v. West

Another thing I think could be elaborated on and written about in great detail is the way that the Eastern part of the fandom and the Western part of the fandom have such different perspectives on Bakudeku in particular. I am not going to go in depth with this, and there are many other people who could go into specifics, but just as an overview:

The manga and the anime are created for and targeted at a certain audience; our take on it will differ based on cultural norms, decisions in translation, understanding of the genre, and our own region-specific socialization. This includes the way in which we interpret certain relationships, the way they resonate with us, and what we do and do not find to be acceptable. Of course, this is not a case-by-case basis, and I’m sure there are plenty of people who hold differing beliefs within one area, but speaking generally, there is a reason that Bakudeku is not regarded as nearly as problematic in the East.

Had this been written by a Western creator, marketed primarily to and within the West (for reference, while I am Chinese, but I have lived in the USA for most of my life, so my own perspective is undoubtedly westernized), I would’ve immediately jumped to make comparisons between the Hero System and the American police system, in that a corrupt, or bastardized system is made no less corrupt for the people who do legitimately want to do good and help people, when that system disproportionately values and targets others while relying on propaganda that society must be reliant on that system in order to create safe communities when in reality it perpetuates just as many issues as it appears to solve, not to mention the way it attracts and rewards violent and power-hungry people who are enabled to abuse their power. I think comparisons can still be made, but in terms of analysis, it should be kept in mind that the police system in other parts of the world do not have the same history, place, and context as it does in America, and the police system in Japan, for example, probably wasn’t the basis for the Hero System.

As much as I do believe in the Death of the Author in most cases, the intent of the author does matter when it comes to content like this, if merely on the basis that it provides context that we may be missing as foreign viewers.

As far as the intent of the author goes, Bakugou is on a route of redemption.

He deserves it. It is unavoidable. That, of course, may depend on where you’re reading this.

Stuck in the Sludge, the Past, and Season One

If there’s one thing, to me, that epitomizes middle school Bakugou, it’s him being trapped in a sludge monster, rescued by his Quirkless childhood friend, and unable to believe his eyes. He clings to the ideology he always has, that Quirkless means weak, that there’s no way that Deku could have grown to be strong, or had the capacity to be strong all along. Bakugou is wrong about this, and continuously proven wrong. It is only when he accepts that he is wrong, and that Deku is someone to follow, that he starts his real path to heroics.

If Bakudeku’s relationship does not appeal to someone for whatever reason, there’s nothing wrong with that. They can write all they want about why they don’t ship it, or why it bothers them, or why they think it’s problematic. If it is legitimately triggering to you, then by all means, avoid it, point it out, etc. but do not undermine the reality of abuse simply to point fingers, just because you don’t like a ship. People who intentionally use the anti tag knowing it’ll show up in the main tag, go after people who are literally minding their own business, and accuse people of supporting abuse are the ones looking for a fight, and they’re annoying as hell because they don’t bring anything to the table. No evidence, no analysis, just repeated projection.

To clarify, I’m referring to a specific kind of shipper, not someone who just doesn’t like a ship, but who is so aggressive about it for absolutely no reason. There are plenty of very lovely people in this fandom, who mind their own business, multipship, or just don’t care.

Calling shippers dumb or braindead or toxic (to clarify, this isn’t targeting any one person I’ve seen, but a collective) based on projections and generalizations that come entirely from your own impression of the ship rather than observation is...really biased to me, and comes across as uneducated and trigger happy, rather than constructive or helpful in any way.

I’m not saying someone has to ship anything, or like it, in order to be a ‘good’ participant. But inserting derogatory material into a main tag, and dropping buzzwords with the same tired backing behind it without seeming to understand the implications of those words or acknowledging the development, pacing, and intentional change to the characters within the plot is just...I don’t know, it comes across as redundant, to me at least, and very childish. Aggressive. Toxic. Problematic. Maybe the real toxic shippers were the ones who bitched and moaned along the way. They’re like little kids, stuck in the past, unable to visualize or recognize change, and I think that’s a real shame because it’s preventing them from appreciating the story or its characters as it is, in canon.

But that’s okay, really. To each their own. Interpretations will vary, preferences differ, perspectives are not uniform. There is no one truth. There are five seasons of the show, a feature film, and like, thirty volumes as of this year.

All I’m saying is that if you want to stay stuck in the first season of each character, then that’s what you’re going to get. That’s up to you.

This may be edited or revised.

#bakudeku#meta#my hero academia#boko no hero academia#bnha#mha#bakugou katsuki#izuku midoriya#ok these are just my general thoughts in response to the people who have hang ups about this ship#like y’all need to pls chill tf out ok#this is also not comprehensive and could definitely be elaborated on#but it’s just general thoughts#it’s just addressing general opposition I’ve seen#I never thought I’d ever write this much about this ship wtf

128 notes

·

View notes

Note

That beautiful writer ask meme: Imagery, Juxtaposition, Symbolism, Allegory, Repetition

This got long, so I’m putting it under a cut.

Imagery: How much do you worldbuild in your current writing project? How do you make your setting seem real and vivid?

I have to admit: world-building is actually not one of my strong suits as a writer. I think I’m better at crafting characters than I am at crafting the worlds they live in. Which makes fanfic pretty great for me, because I can be lazy and piggy-back off of an already established world. 😉 I don’t have to do much world-building for Undertow, since a lot of that is already done for me, but I do have some original projects that involve more creativity on that front. I think when I do world-building I often focus most on cultural things: local beliefs and ideology, art, politics, etc.

As for the setting, I like to highlight sensory/impressionistic details as the character experiences them. The same setting can be experienced very differently depending on a character’s frame of mind and what sorts of things they tend to pay attention to. Specificity is also really helpful in making the world seem real. I like to try and zero in on a few small/specific details when writing my descriptions.

Juxtaposition: Do you include subplots in your writing? How do you balance them alongside your main plots?

I usually do have subplots. A lot of times what I like to do with my stories is focus on an overarching theme, and then find ways to express those ideas on both a macro and micro level, or as both symbolic and literal. With Undertow, that theme is trauma and recovery, specifically how it relates to personal agency and growth. And so I have multiple interwoven plot threads that all deal with that same theme. So it isn’t so much like... separate plots, as it is one big plot tapestry.

Symbolism: What does writing mean to you? How has it impacted your life?

Oof, man. This is a big one. I think growing up I always really struggled to express myself and to have a voice. And writing became my outlet for that. I wasn’t naturally good at it, but I kept working at it, and over time I improved a lot. I think a lot about narrative, and the role it plays in human culture. Both as individuals and as a society, we define our reality through storytelling: the stories we tell ourselves, and the stories we tell to others. I very much want those stories to be as real and true and organic as possible, even when crafting these totally fantastical, fictional realities. Because every story we tell and every story we consume influences our reality... even if it’s just in these subtle, fractional ways.

So there’s the personal, of course: I want to have a voice, I want to be able to reach out to people and show them what I see and feel. I want to be able to point to something and say: “Look at this. This is important. This matters.”

Then there’s the social: knowing that people are engaging with the things I wrote and making it their own.

Then there’s the bigger narrative: I want to make a ripple in our shared reality, even if only a very small one.

But I struggle to do that. Because... well, because of a lot of things. Mental health, physical health, life circumstances, etc. So writing is both this super important thing that I love and a lifelong struggle to overcome massive personal obstacles.

But I genuinely believe that I would not be alive today without it.

Allegory: What is the theme of your current writing project? Is there a message you’d like readers to consider?

I talked about this a bit under Juxtaposition, so I’ll try not to get too repetitive. I also don’t necessarily want to state all of the messages outright, because as a writer I kind of like to just let the subtext speak for itself. But yes, there are definitely themes and messages that I hope readers will pick up on. Some of it involves a bit of meta-criticism over the whole good vs. evil, black and white worldview of D&D and similar fantasy worlds. Which ties into the overarching trauma theme because... hmm, how do I explain this? We cannot as a society take ownership of our sins if we refuse to claim them. People are not inherently good or bad. It’s our actions that matter.

Also, trauma doesn’t have to mean an end to things like love and happiness. Sometimes those things just come to us in unexpected and complicated ways.

Repetition: Is there anything you find you repeat across your witting projects? Symbols, tropes, descriptions, themes?

Oh gosh, so many things. I use water symbolism a lot. I talk about trauma a lot. Most of my writing is pretty angsty. I also have a penchant for using theories in astrophysics as emotional metaphors. 😏

I love to plant little seeds that end up bearing fruit later on in the story. Like, a character will say something, and then that thing will get repeated later by another character, but with added nuance/weight/irony. I love to connect things. Seemingly disparate characters and stories might all eventually link up in some way.

I tend to use a lot of subtext. The things characters don’t say are often just as important as the things they do. That can also be true of the narrative itself. I convey a lot of things by implication. (I tend to stress a lot over whether any of that is actually clear to readers. Ideally I’d like to be one of those authors who rewards close/repeat reading, but it’s also possible I’m just being way too opaque.)

A lot of my characters have bad relationships with their parents.

A lot of my characters have intense/complicated sexualities.

I use a lot of visceral imagery. I often talk about the body (and the breaking open of it) as a metaphor for emotional intimacy. (Hoo boy is this relevant for my current fic.) Blood isn’t just blood. It’s also feelings.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Weekend Warrior Christmas - New Year’s Edition – WONDER WOMAN 1984, NEWS OF THE WORLD, PROMISING YOUNG WOMAN, ONE NIGHT IN MIAMI..., PIECES OF A WOMAN, HERSELF, SYLVIE’S LOVE and More!

Welcome to the VERY LAST Weekend Warrior of the WORST YEAR EVER!!! But hopefully not the last column forever, even though I already plan on taking much of January off from writing 8 to 10 reviews each week. It just got to be too much for a while there.

Because it’s the last week of the year, there are a lot of really good movies, some in theaters but also quite a few on streaming services. In fact, there are a good number of movies that appeared in my Top 10 for the yearover at Below the Line, as well as my extended Top 25 that I’ll share on this blog sometime next week. I was half-hoping to maybe write something about the box office prospects of some of the new movies, but after the last couple weeks, it’s obvious that box office is not something that will be something worth writing about until sometime next spring or summer.

(This column is brought to you by Paul McCartney’s new album “McCartney III” which I’m listening to as I finish this up… and then other solo Beatles ditties picked for me randomly by Tidal.)

First up is easily one of the most anticipated movies of the year, or at least one that actually didn’t move to 2021, and that’s WONDER WOMAN 1984 (Warner Bros.), Patty Jenkins’ sequel to the 2017 hit, once again starring Gal Gadot as Diana Prince. I reviewed it here, but basically the sequel introduces Wonder Woman arch-nemeses Barbara Minerva aka Cheetah, as played by Kristen Wiig, and Pedro Pascal’s Max Lord and how an ancient artifact gives them both their powers, as well as helps to bring Diana’s true love Steve Trevor (Chris Pine) back despite him having disappeared presumed dead in WWI. As you can see by reading my review, I thought it was just fine, not great and certainly not something I’d make an attempt to see a second time in a 25% capacity movie theater. Fortunately, besides debuting in around 2,100 movie theaters across the nation, it will also be on HBO Max day and date, which has caused quite a stir. Being Christmas weekend with no work/school on Monday, I can see it still making somewhere between $10 and 12 million, but I can’t imagine it doing nearly what it might have done with most theaters only 25-30% full at the maximum and that theater count being roughly half the number it might have gotten during the “normal times.”

Paul Greengrass’ Western NEWS OF THE WORLD (Universal) reteams him with his Captain Phillips star Tom Hanks, this time playing Captain Jefferson Kidd, a Civil War soldier who travels from town to town in the Old West reading from newspapers to anyone who has a dime and time to listen. After one such reading, he discovers a young girl (Helena Zengel) on her own, having spent the last few years with a family of Native Americans who were killed by soldiers. Together, they travel across America as Kidd hopes to bring the girl to her last surviving family members.

I already reviewed Greengrass’ movie for Below the Line, and I also spoke to Mr. Greengrass, an interview you can read that right here (once it goes live), but I make no bones that this was one of my favorite movies I’ve seen this year, and it’s not just due to the fine work by Greengrass and his team. No, it’s just as much about the emotion inherent in the story, and the relationship between the characters played by Hanks and Zengel.

I’ve watched the movie three times now, and I’m still blown away by every frame and moment, the tension that’s created on this difficult journey but also where it leaves the viewers at the end that promises that there can be hope and joy even in the most difficult and turbulent times. It’s a wonderful message that’s truly needed right now.

Listen, I’m not gonna recommend going to a movie theater if you don’t feel it’s safe – I’ve already spoken my peace on this at a time when COVID numbers were much lower – but this is a movie that I personally can’t wait to see in a movie theater. I honestly can’t see the movie making more than $3 or 4 million in the open theaters considering how few people are willing to go to movie theaters. Obviously, this isn’t as big a draw as Wonder Woman, but it is a fantastic big screen movie regardless.

Also opening in theaters this Friday is Emerald Fennell’s directorial debut PROMISING YOUNG WOMAN (Focus Features), starring the wonderful Oscar-nominated Carey Mulligan as Cassie Thomas, a woman who has revenge on her mind. Cassie spends her nights picking up guys in bars by pretending she’s so drunk she can barely walk, then humiliating them and presumably worse. When she encounters an acquaintance from med school in the form of Bo Burnham’s Ryan, the two begin dating, though he ends up awakening a darker side to Cassie that seeks revenge for something that happened back during their school days. (Honestly, if you’re already sold, just skip to the next movie. That’s all I want you to know before watching it.)

I was ready to love Fennell’s movie when it opened with a disgusting shot of gross stock market bros in loose-fitting suits gyrating in slow motion before one of them tries to pick up a totally soused Cassie at the club. It’s a scene that really plays itself out quite well, and then leads into Mulligan’s character allowing another clear scumbag (played by Christopher Mintz-Plasse, maybe as a slight-older McLovin?) before turning the tables on him as well.

There’s going to be a lot of talk about this movie after people see it, since it’s one of those great films that begins a lot of conversations. I imagine most women of a certain age will love it, but some men might see themselves in some of the characters (even Burnham’s) and wonder whether Cassie just won’t take crap from any man or if she’s a full-on misandrist. One thing we do know a lot is that she does this sort of thing a lot, and there’s something from her past that has driven her involving something that happened to her female friend in med school. I’m going to stop talking about the plot here, because I definitely don’t want to spoil anything who hasn’t seen the movie, but the second half of the movie is as deeply satisfying as Tarantino’s Kill Bill in terms of the surprises.

You’ll realize while watching what a treat you’re in for when you first watch Mulligan’s amazing transformation from pretending to be drunk to being completely cognizant and just all the emotions we see her go through after that. Of course, we never really know what she’s actually doing to the guys she lets pick her up -- she keeps a notebook with guy’s names and a quizzical counting system, so we can only imagine.

Fennell’s screenplay is fantastic but her work as a first-time director in maintaining the the tone and pacing of the movie is really what will keep you captivated, whether it’s the amazing musical choices or how Cassie dresses up to lure men. There’s also a great cast around Mulligan whether it’s comic Burnham in a relatively more serious role, but one that also allows him a musical number. (No joke.) Fennel’s amazing casting doesn’t just stop there from, Jennifer Coolidge as Cassie’s mother to Laverne Cox as Gail, her workmate/boss at the coffee shop – both of them add to the film’s subtle humor elements. Alfred Molina shows up to give a show-stopping performance, and Alison Brie also plays a more dramatic role as another one of Cassie’s classmates. I can totally understand why the Golden Globes might have deemed the movie a “comedy/musical” (for about two days before going back) , but putting so many funny people in dramatic roles helps give Promising Young Woman its own darkly humorous feel. All that darkness is contrasted by this sweet romance between Cassie and Ryan that’s always in danger of imploding due to Cassie’s troubled nature.

The biggest shocking surprise is saved for the third act, and boy, it’s going to be one that people will be talking about for a VERY long time, because it’s just one gut punch after another. I loved this movie, as it’s just absolutely brilliant – go back and see where it landed in my Top 10. As one of the best thrillers from the past decade, people will be talking about this for a very long time

Promising Young Woman hits theaters on Christmas Day, and presumably, it will be available on VOD sometime in January, but this is not one you want to wait on. If you do go see it in theaters, just be safe, please. No making out with random men or women, please.

Regina King’s narrative feature debut, ONE NIGHT IN MIAMI... (Amazon Studios), will ALSO be in theaters on Christmas Day, and though I’ve reviewed it over at Below the Line, but I’ll talk a little more about it here just for my loyal Weekend Warrior readers.

Yet another movie that made my Top 10, this one stars a brilliant quartet of actors -- Kingsley Ben-Adir, Leslie Odom Jr., Aldis Hodge and Eli Goree—as four legendary black icons: Malcolm X, Sam Cooke, Jim Brown and Cassius Clay, on the night after the last of them wins the World Boxing Championship against Sonny Liston in February 1964. The four men meet in Malcolm X’s hotel room to discuss what’s happening in their lives and the world in general, as well as Clay’s decision to join the Nation of Islam, just as Malcolm X is getting ready to leave the brotherhood due to philosophical differences with the group. In fact, all four men have philosophical differences that are discussed both in good humor and in deep conflict as they disagree on their place in a white-dominated world in a year before the Civil Rights Act would be signed.

First of all, there’s no way to talk about this movie without discussing the Kemp Powers play on which it’s based, and we can’t mention that without mentioning that Powers also co-wrote and co-directed Pixar’s Soul, which will be available on Disney+ this Friday. It’s a fantastic script and King put together a fantastic cast of actors who really give their all to every scene. In the case of Leslie Odom, Jr., you really can believe him as Cooke, especially in a number of fantastic performances pieces. Likewise, Goree looks a lot like Clay both in the ring and out, carrying all of the swagger for which he would become more famous as Ali.

I’ve seen the movie twice already and if you’ve looked at my Top 10, then you already know this is another one that made my cut, so I don’t think I need to give it a much harder sell. I’m sure you’ll be hearing a lot about this one on its journey to Oscar night when hopefully, King becomes the first woman of color to be nominated in the directing category. Or rather, she’ll probably tie for that honor with Nomadland director Chloé Zhao.

If you don’t feel like going to theaters for this one, you’ll be able to catch it on Amazon Prime Video on January 15, too… you’ll just have to wait a little longer.

Also, the new Pixar animation movie, SOUL, directed by Pete Docter (Up, Inside Out) and co-directed by Kemp Powers (remember him?), will hit Disney+ on Christmas Day, and I reviewed it here, so I probably don’t have lot more to say about it, but it’s great, and if you have Disney+, I’m sure you’ll be watching it.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t get a screener for Matteo Garrone’s PINNOCHIO (Roadside Attractions), which also opens in about 700 theaters on Christmas Day. This adaptation stars Robert Benigni as Geppeto, who famously starred as Pinocchio in his own version of the classic fairy tale from 2002. That other movie was “Weinsteined” at a time when that just meant that a movie was ruined by Harvey Weinstein’s meddling, rather than anything involving sexual assault.

Another great movie hitting streaming this week is Eugene Ashe’s SYLVIE’S LOVE, which streams on Amazon Prime Video today. It stars Tessa Thompson as Sylvie and Nnamdi Asomugha (also a producer on the film) as Robert, who meet one summer in the late 50s while working at Sylvie’s father’s record store. He is a jazz musician who is on the rise, but their romance is cut short when he gets a gig in Paris but she refuses to go with him. Also, she’s pregnant with his child. Years later, they reconnect with her now being married with a young daughter (clearly Robert’s) and they realize that the love between them is still very real and true.

This is the first of three movies I watched this week where I went in with very little knowledge and absolute zero expectations. Like everyone else on earth, I am an avid fan of Ms. Thompson’s work both in movies like Thor: Ragnarok and smaller indies. She’s just a fantastic presence that lights up a screen. While I wasn’t as familiar with Asomugha’s acting work – he’s produced some great films and acted in a few I liked, included Crown Heights – there’s no denying the chemistry between the two.

What’s kind of interesting about the movie is that it combines a few elements from other great movies released this week, including Soul and A Night in Miami, but in my opinion, handles the music business aspect to the story better than the much-lauded Netflix movie, Ma Raimey’s Black Bottom. Frankly, I also think the performances by the two leads are as good as those by Boseman and Davis in that movie, but unfortunately, Amazon is submitting this to the Emmys as as “TV movie” rather than to the Oscars, so that’s kind of a shame.

This is a movie that’s a little hard to discuss why I enjoyed it so much without talking about certain scenes or moments, or just go through the entire story, but I think part of the joy of appreciating what Ashe has done in his second original feature film is to tell the story of these two characters over the course of a decade or so in a way that hasn’t been done before. That alone is quite an achievement, because we’ve seen many of those types of movies over the years (When Harry Met Sally, for instance).

What I really liked about Sylvie’s Love over some of the other “black movies” this year is that it literally creates its own world and just deals with the characters within it, rather than trying to make a big statement about the world at the time. Maybe you can say the same about Soul in that sense, but you would be absolutely amazed by how much bigger an audience you can get by telling a grounded story in a relatable world, and then throw in a bit of music, as both those movies do.

So that’s all I’ll say except that this will is now on Amazon Prime Video , so you have no excuse not to check it out while you wait for Regina King’s equally great One Night in Miami to join it in mid-January.

Hitting Netflix on Christmas day is Robert Rodriguez’s WE CAN BE HEROES, his sequel to his 2005 family film The Adventures of Shark Boy and Lava Girl – not his best moment -- which follows the kids of the Heroics, a Justice League-like super group. They’re all in a special school for kids with powers but they have to step up when the Heroics are captured by aliens. Want to know what will happen? Well, you’ll just have to wait for Christmas Day for when my review drops to find out whether I liked it more or less than Rodriguez’s earlier film which SPOILER!! I hated.)

The first thing you need to get past is that Shark Boy and Lava Girl are now man and wife, and just that fact might be tough for anyone who only discovered the movie sometime more recently. There are other familiar faces in the Heroics like Pedro Pascal, Sung Kang, Christian Slater, Priyanka Chopra Jonas and more, so clearly, Rodriguez is still able to pull together a cast.

The movie actually focuses on YaYa Goselin’s Missy Moreno, daughter of the Heroic’s leader (Pascal) who has also retired. Just as aliens are invading the earth, Missy is put into a school of kids with superpowers, all kids of various Heroic members. Sure, it’s derived directly from The X-Men and/or Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children, so yeah… basically also the X-Men. We meet all of the kids in a great scene where we see them using their powers and learn their personalities, and honestly, they really are the best part of the movie.Probably the most adorable is Guppy, the very young daughter of Shark Boy and Lava Girl, played by Viven Blair. Oddly, Missy doesn’t have any powers so she feels a bit fish-out-of-water in the group even though, like her father, she proves to be a good leader.

As much as I really detested Rodriguez’s Shark Boy and Lava Girl movie, I feel like he does a lot better by having a variety of kids in this one, basically something for everyone, but also not a bad group of child actors. (There’s also a fun role for Adriana Barraza.) There are definitely aspects that are silly, but Rodriguez never loses sight of his audience, and wisely, Netflix is offering this as a Christmas Day release which should be fun for families with younger kids who might see this as their first superhero movie.

More discerning viewers may not be particularly crazy about visual FX, all done as usual in Rodriguez’s own studio but some of them look particularly hoaky and cheap compared to others. (I mean, that’s probably the appeal for hiring Rodriguez because he’s able to do so much in-house. In this case, he got all four of his own kids involved in various capacities of making the film.)

We Can Be Heroes is clearly a movie made for kids, so anyone expecting anything on part with Amazon’s The Boys will be quite disappointed. It’s probably Rodriguez getting slightly closer to Spy Kids than he has with any of his other family-friendly movies, but one shouldn’t go in with the expectations that come with any of the much bigger blockbusters released these days. Personally, I enjoyed that fact, and I totally would watch another movie with this superteam.

Michel Stasko’s BOYS VS. GIRLS (Gravitas Ventures) is a fun retro-comedy that follows a war between the male and female counselors at Camp Kindlewood, which has just gone co-ed. At the center of it all is Dale (Eric Osborne) and Amber (Rachel Dagenais) as two teens who are in the middle of a meet-cute romance in the middle of a inter-gender competition called “Lumberman vs. Voyagers,” which I have no idea whether it’s a real thing or not.

I probably should have known I’d like this one from the catchy New Order-ish song in the opening credits, but listen, Wet Hot American Summer is one of my all-time favorite movies, and that was basically made to satirize ‘80s movies like Meatballs. This one falls more towards to the latter in terms of humor, but it also feels authentic to the ‘80s summer camp experience.

It helps that the grown-ups at the camp are played by the likes of Kevin McDonald from New Kids on the Block, Colin Mochrie from Whose Line is It Anyway and others, but it’s really about the younger cast playing teen boys and girls in the throes of puberty, something we all can in some way relate to. The young cast play a series of stereotypical young but there are a lot of funny tropes within them, as each of the cast is given a chance to deliver some of the funnier gags. This isn’t necessarily high-brow humor, mind you, but I love the fact that you can still make a movie about a time where you could still make fun of girl’s periods in school. (I’m kidding. I just put that in there cause I feel like I need to throw things like that into this column just to see if anyone is ACTUALLY reading it.)

The presumably Canadian Stasko is another great example of an independently-spirited filmmaker who has an idea for a fun movie and then just goes about making it, regardless of having big stars or anything to sell it besides many funny moments that can be featured a trailer, so that those who like this kind of movie will find it. Listen, Wet Hot American Summer wasn’t a huge hit when it was released. I still remember it having trouble getting a single screening at the multiplex in Times Square when it was released but over the years since it became sort of a cult hit (kind of due to Netflix having it to rent on DVD, I think).

Besides a fun script and cast, Stasko also find a way to include tunes that sound so much like real ‘80s songs we would have heard on the radio but aren’t quite the big hits that would have cost him thousands of dollars, but I really just enjoyed the heck out of the tone and overall fun attitude that went into making this movie.

Also on VOD now is Ian Cheney and Martha Shane’s fascinating and funny doc, THE EMOJI STORY (Utopia), which I saw at the Tribeca Film Festival when it was called “Picture Character.” (That’s what “emoji” in Japanese means, just FYI.) As you can guess it’s about the origins and rise of the emoji as a form of communication from its humble beginning in Japan to becoming one of the biggest trending crazes on the globe. I’m not that big an Emoji guy myself – I tend to use the thumbs up just for ease, but I do marvel at those who can put together full thoughts using a string of these symbols, and if you want to know more about them, this is the movie you should watch.

Now let’s cut ahead to some of the movies that will be opening and streaming NEXT week…

Hitting select theaters on Wednesday, December 30 and what really is my “FEATURED FLICK” for this column is Hungarian filmmaker Kornél (White God) Mundruczó’s PIECES OF A WOMAN (Netflix) before its streaming premiere on Netflix January 7.

Written by Kata Wéber, who also wrote Mundruczó’s earlier film, it stars Vanessa Kirby (The Crown) and Shia Labeouf as Martha and Sean Weiss, a Boston couple who lose their baby during a particularly difficult home birth and follows the next year in their lives and how that tragic loss affects their relationship with each other and those around them.

As you can imagine, Pieces of a Woman is a pretty heavy drama, one that reminded me of the films of Todd Field (Little Children, In the Bedroom) in terms of the intensity of the drama and the emotions on screen from the brilliant cast Mundruczó put together for his English language debut. I’m not sure I could use the general plot to sell anyone on seeing this because it is very likely the worst possible date movie of the year after Netflix’s 2019 release, Marriage Story, but it’s just as good in terms of the writing and performances.

At the center of it is Kirby – and yeah, I still haven’t watched The Crown, so shut up! I’ll get to it!!! – who most of us fell in love with for her role in Mission: Impossible - Fallout, but what we see her go through as an actress here really shows the degree of her abilities. But it also shows what Mundruczó can do with material that (like many movies) started out as a play. For instance, one of the first big jaw-dropping moments is the home birth scene that goes on for a long time, seemingly all in one shot, and Kirby is so believable in terms of a woman going through a difficult birth, you’d believe she has had children herself. (She hasn’t.) I also don’t want to throw Shia Labeouf under the bus right now just because that seems like the trendy thing to do. (Without getting it, I believe FKA Twigs… but that doesn’t deny the fact that Labeouf is just the latest great actor that everyone wants to cancel.)

Anyway, to change the subject, we have to talk about Ellen Burstyn, who plays Martha’s meddling mother, who is quite clingy and overbearing, so when the couple lose their baby, she steps in to take to task the midwife she deems responsible (played by the highly-underrated Molly Parker). Or rather, she hires a family lawyer (Sarah Snook) to take her to court to get compensation for the loss of her daughter’s baby. The film’s last act culminates as their case goes to court.

Again, the film covers roughly a year after the tragedy and deals not only with how Martha and Sean’s relationship is affected and how it emotionally affects Martha in particular, but also how others around them start behaving towards them. It feels so authentic and real that you wonder where the screenwriter was drawing from, but Mundruczó has more than prove himself as as filmmaker by creating something that is visually compelling and even artsy while still doing everything to help promote the story and performances over his own abilities as a director. Doesn’t hurt that he has composer Howard Shore scoring the film in a way that’s subtle but effective.

Listen, if you’re looking for a comedy riot that will entertain you with funny one-liners and pratfalls than Pieces of a Woman is not for you. This is a devastating movie that really throws the viewer down a deep spiral along with its characters. The first time I watched it, I was left quite broken, and maybe even more so on second viewing. (As we get closer to Oscar season… in four months … I hope this film will be recognized and not just thrown under the table due to Labeouf’s involvement. That would be as big a tragedy and misjustice as much of what happens in the movie.)

So yeah, in case you wondered why this also made it into my prestigious Top 10 for the year, that is why. :)

Also in theaters on Wednesday, December 30 is another terrific drama, the Phyllida Lloyd-directed HERSELF (Amazon Studios), co-written and starring Clare Dunne, as Sandra, a mother of two young girls, trying to get out of an abusive marriage, while making ends meet and providing shelter for her kids. One day, she learns about a way that she can build her own home, and one of the women she cares for offers a plot of land

Another movie that I really didn’t know much about going into, other than Phyllida Lloyd being a talented filmmaker whose movie The Iron Maiden, which won Meryl Streep her 500th Oscar, I enjoyed much more than the popular blockbuster hit musical, Mamma Mia! This is a far more personal story that reminded me of Ken Loach’s I, Daniel Blake, a smaller and more intimate character piece that shines a light on British actor Clare Dunne, who as with some of the best and most personal movie projects, co-wrote this screenplay for herself to act in.

There are aspects to the film that reminds me of many other quaint Britcoms in terms of creating a story where one person’s challenge is taken up by others who are willing to help, and in this case, it’s Sandra’s desire to build a house for her two quite adorable daughters while also trying to keep it secret from her abusive ex.

Dunne’s performance isn’t as showy as some of the other dramatic performances mentioned in this very column, but she and Lloyd do a fine job creating an authenticity that really makes you believe and push for her character, Sandra, surrounding her with characters who can help keep the movie on the lighter side despite very serious nature of spousal abuse (which also rears its ugly head in Pieces of a Woman). Oh, and don’t get too comfortable, because this, too, leads to an absolutely shocking and devastating climax you won’t see coming. (Well, now you will… but you’ll still be shocked. Trust me.)

Still, it’s a really nice movie with the house being built clearly a metaphor. I know there’s a lot of truly fantastic movies discussed in this week’s column but don’t let this wonderful British drama pass you by, because you can tell it’s a labor of love for everyone who made it.

Herself will be in theaters for roughly a week starting December 30 before streaming on Prime Video on January 8.

In select theaters and on VOD on New Year’s Day is Roseanne Liang’s WWII thriller SHADOW IN THE CLOUD (Vertical/Redbox Entertainment), starring Chloë Grace Moretz as Flight Officer Maude Garrett, who is assigned to deliver a top-secret package on the B-17 bomber “The Fool’s Errand” with an all-male crew that throws her into a turret “for her own safety.” She ends up getting trapped down there as the plane is attacked by a creature that no one believes is out there, as they fight back against the unseen enemy, many secrets are revealed.