#the living son of the triple goddess and embodiment of magic itself

Text

Pagan Paths: Wicca

Wicca is the big granddaddy of neopagan religions. Most people who are familiar with modern paganism are specifically familiar with Wicca, and will probably assume that you are Wiccan if you tell them you identify as pagan. Thanks to pop culture and a handful of influential authors, Wicca has become the public face of modern paganism, for better or for worse.

Wicca is also one of the most accessible pagan religions, which is why I chose to begin our exploration of individual paths here. Known for its flexibility and openness, Wicca is about as beginner-friendly as it gets. While it definitely isn’t for everyone, it can be an excellent place to begin your pagan journey if you resonate with core Wiccan beliefs.

This post is not meant to be a complete introduction to Wicca. Instead, my goal here is to give you a taste of what Wiccans believe and do, so you can decide for yourself if further research would be worth your time. In that spirit, I provide book recommendations at the end of this post.

History and Background

Wicca was founded by Gerald Gardner, a British civil servant who developed an interest in the esoteric while living and working in Asia. Gardner claimed that, after returning to England, he was initiated into a coven of witches who taught him their craft. Eventually, he would leave this coven and start his own, at which point he began the work of bringing Wicca to the general public. In 1954, Garner published his book Witchcraft Today, which would have a great impact on the formation of Wicca, as would his 1959 book The Meaning of Witchcraft.

Gardner claimed that the rituals and teachings he received from his coven were incomplete — he attempted to fill in the gaps, which resulted in the creation of Wicca. Author Thea Sabin calls Wicca “a New Old Religion,” which is a good way to think about it. When Gardner wrote the first Wiccan Book of Shadows, he combined ancient and medieval folk practices from the British Isles with ceremonial magic dating back to the Renaissance and with Victorian occultism. These influences combined to create a thoroughly modern religion.

Wicca spread to the United States in the 1960s, at which time several new and completely American traditions were born. Some of these traditions are simply variations on Wicca, while others (like Feri and Reclaiming, which we’ll discuss in future posts) became unique, full-fledged spiritual systems in their own right. In America, Wicca collided with the counter-culture movement, and several activist groups began to combine the two. Wicca has continued to evolve through the decades, and is still changing and growing today.

There are two main “types” of Wicca which take very different approaches to the same deities and core concepts.

Traditional Wicca is Wicca that looks more or less like the practices of Gerald Gardner, Doreen Valiente, Alex Sanders, and other early Wiccan pioneers. Traditional Wiccans practice in ritual groups called covens. Rituals are typically highly formal and borrow heavily from ceremonial magic. Traditional Wicca is an initiatory tradition, which means that new members must be trained and formally inducted into the coven by existing members. This means that if you are interested in Traditional Wicca, you must find a coven or a mentor to train and initiate you. However, most covens do not place any limitations on who can join and be initiated, aside from being willing to learn.

Most Traditional Wiccan covens require initiates to swear an oath of secrecy, which keeps the coven’s central practices from being revealed to outsiders. However, there are traditional Wiccans who have gone public with their practice, such as the authors Janet and Stewart Farrar.

Eclectic Wicca is a solitary, non-initiatory form of Wicca, as made popular by author Scott Cunningham in his book Wicca: A Guide for the Solitary Practitioner. Eclectic Wiccans are self-initiated and may practice alone or with a coven, though coven work will likely be less central in their practice. There are very few rules in Eclectic Wicca, and Wiccans who follow this path often incorporate elements from other spiritual traditions, such as historical pagan religions or modern energy healing. Because of this, there are a wide range of practices that fall under the “Eclectic Wicca” umbrella. Really, this label refers to anyone who considers themselves Wiccan, follows the Wiccan Rede (see below), and does not belong to a Traditional Wiccan coven. The majority of people who self-identify as Wiccan fall into this group.

Core Beliefs and Values

Thea Sabin says in her book Wicca For Beginners that Wicca is a religion with a lot of theology (study and discussion of the nature of the divine) and no dogma (rules imposed by religious structures). As a religion, it offers a lot of room for independence and exploration. This can be incredibly empowering to Wiccans, but it does mean that it’s kind of hard to make a list of things all Wiccans believe or do. However, we can look at some basic concepts that show up in some form in most Wiccan practices.

Virtually all Wiccans live by the Wiccan Rede. This moral statement, originally coined by Doreen Valiente, is often summarized with the phrase, “An’ it harm none, do what ye will.”

Different Wiccans interpret the Rede in slightly different ways. Most can agree on the “harm none” part. Wiccans strive not to cause unnecessary harm or discomfort to any living thing, including themselves. Some Wiccans also interpet the word “will” to be connected to our spiritual drive, the part of us that is constantly reaching for our higher purpose. When interpreted this way, the Rede not only encourages us not to cause harm, but also to live in alignment with our own divine Will.

Wiccans experience the divine as polarity. Wiccans believe that the all-encompassing divinity splits itself (or humans split it into) smaller aspects that we can relate to. The first division of deity is into complimentary opposites: positive and negative, light and dark, life and death, etc. These forces are not antagonistic, but are two halves of a harmonious whole. In Wicca, this polarity is usually embodied by the pairing of the God and Goddess (see below).

Wiccans experience the divine as immanent in daily life. In the words of author Deborah Lipp, “the sacredness of the human being is essential to Wicca.” Wiccans see the divine present in all people and all things. The idea that sacred energy infuses everything in existence is a fundamental part of the Wiccan worldview.

Wiccans believe nature is sacred. In the Wiccan worldview, the earth is a physical manifestation of the divine, particularly the Goddess. By attuning with nature and living in harmony with its cycles, Wiccans attune themselves with the divine. This means that taking care of nature is an important spiritual task for many Wiccans.

Wiccans accept that magic is real and can be used as a ritual tool. Not all Wiccans do magic, but all Wiccans accept that magic exists. For many covens and solitary practitioners, magic is an essential part of religious ritual. For others, magic is a practice that can be used not only to connect with the gods, but also to improve our lives and achieve our goals.

Many Wiccans believe in reincarnation, and some may incorporate past life recall into their spiritual practice. Some Wiccans believe that our souls are made of cosmic energy, which is recycled into a new soul after our deaths. Others believe that our soul survives intact from one lifetime to the next. Many famous Wiccan authors have written about their past lives and how reconnecting with those lives informed their practice.

Important Deities and Spirits

The central deities of Wicca are the Goddess and the God. They are two halves of a greater whole, and are only two of countless possible manifestations of the all-encompassing divine. The God and Goddess are lovers, and all things are born from their union.

Though some Wiccan traditions place a greater emphasis on the Goddess than on the God, the balance between these two expressions of the divine plays an important role in all Wiccan practices (remember, polarity is one of the core values of this religion).

The Goddess is the Divine Mother. She is the source of all life and fertility. She gives birth to all things, yet she is also the one who receives us when we die. Although she forms a duality in her relationship with the God, she also contains the duality of life and death within herself. While the God’s nature is ever-changing, the Goddess is constant and eternal.

The Goddess is strongly associated with both the moon and the earth. As the Earth Mother, she is especially associated with fertility, abundance, and nurturing. As the Moon Goddess, she is associated with wisdom, secret knowledge, and the cycle of life and death.

Some Wiccans see the goddess as having three main aspects: the Maiden, the Mother, and the Crone. The Maiden is associated with youth, innocence, and new beginnings; she is the embodiment of both the springtime and the waxing moon. The Mother is associated with parenthood and birth (duh), abundance, and fertility; she is the embodiment of the summer (and sometimes fall) and of the full moon. The Crone is associated with death, endings, and wisdom; she is the embodiment of winter and of the waning moon. Some Wiccans believe this Triple Goddess model is an oversimplification, or complain that it is based on outdated views on womanhood, but for others it is the backbone of their practice.

Symbols that are traditionally used to represent the Goddess include a crescent moon or an image of the triple moon (a full moon situated between a waxing and a waning crescent), a cup or chalice, a cauldron, the color silver, and fresh flowers.

The God is the Goddess’s son, lover, and consort. He is equal parts wise and feral, gentle and fierce. He is associated with sex and by extension with potential (it could be said that while the Goddess rules birth, the God rules conception), as well as with the abundance of the harvest. He is the spark of life, which is shaped by the Goddess into all that is.

The God is strongly associated with animals, and he is often depicted with horns to show his association with all things wild. As the Horned God he is especially wild and fierce.

The God is also strongly associated with the sun. As a solar god he is associated with the agricultural year, from the planting and germination to the harvest. While the Goddess is constant, the God’s nature changes with the seasons.

In some Wiccan traditions, the God is associated with plant growth. He may be honored as the Green Man, a being which represents the growth of spring and summer. This vegetation deity walks the forests and fields, with vines and leaves sprouting from his body.

Symbols that are traditionally used to represent the God include phalluses and phallic objects, knives and swords, the color gold, horns and antlers, and ripened grain.

Many covens, both Traditional and Eclectic, have their own unique lore around the God and the Goddess. Usually, this lore is oathbound, meaning it cannot be shared with those outside the group.

Many Wiccans worship other deities besides the God and Goddess. These deities may come from historical pantheons, such as the Greek or Irish pantheon. A Wiccan may work with the God and Goddess with their coven or on special holy days (see below), but work with other deities that are more closely connected to their life and experiences on a daily basis. Wiccans view all deities from all religions and cultures as extensions of the same all-encompassing divine force.

Wiccan Practice

Most Wiccans use the circle as the basis for their rituals. This ritual structure forms a liminal space between the physical and spiritual worlds, and the Wiccan who created the circle can choose what beings or energies are allowed to enter it. The circle also serves the purpose of keeping the energy raised in ritual contained until the Wiccan is ready to release it. Casting a circle is fairly easy and can be done by anyone — simply walk in a clockwise circle around your ritual space, laying down an energetic barrier. Some Wiccans use the circle in every magical or spiritual working, while others only use it when honoring the gods or performing sacred rites.

While it is on one level a practical ritual tool, the circle is also a representation of the Wiccan worldview. Circles are typically cast by calling the four quarters (the four compass points of the cardinal directions), which are associated with the four classical elements: water, earth, fire, and air. Some (but not all) Wiccans also work with a fifth element, called spirit or aether. The combined presence of the elements makes the circle a microcosm of the universe.

Casting a circle requires the Wiccan to attune themselves to these elements and to honor them in a ritual setting. This is referred to as calling the quarters. When a Wiccan calls the quarters, they will move from one cardinal point to the next (usually starting with east or north), greet the spirits associated with that direction/element, and invite them to participate in the ritual. (If spirit/aether is being called, the direction it is associated with is directly up, towards the heavens.) This is done after casting the circle, but before beginning the ritual.

What happens within a Wiccan ritual varies a lot — it depends on the Wiccan, their preferences, and their goals for that ritual. However, nearly all Wiccan religious rites begin with the casting of the circle and calling of the quarters. (Some would argue that a ritual that doesn’t include these elements cannot be called Wiccan.)

When the ritual is completed, the quarters must be dismissed and the circle taken down. Wiccans typically dismiss the quarters by moving from one cardinal point to the next (often in the reverse of the order used to call the quarters), thanking the spirits of that quarter, and politely letting them know that the ritual is over. The circle is taken down (or “taken up,” as it is called in some traditions) in a similar way, with the person who cast the circle moving around it counterclockwise and removing the energetic barrier they created. This effectively ends the ritual.

There are eight main holy days in Wicca, called the sabbats. These celebrations, based on Germanic and Celtic pagan festivals, mark the turning points on the Wheel of the Year, i.e., the cycle of the seasons. By honoring the sabbats, Wiccans attune themselves with the natural rhythms of the earth and actively participate in the turning of the wheel.

The sabbats include:

Samhain (October 31): Considered by many to be the “witch’s new year,” this Celtic fire festival has historic ties to Halloween. Samhain is primarily dedicated to the dead. During this time of year, the otherworld is close at hand, and Wiccans can easily connect with their loved ones who have passed on. Wiccans might celebrate Samhain by building an ancestor altar or holding a feast with an extra plate for the dead. Samhain is the third of the three Wiccan harvest festivals, and it is a joyous occasion despite its association with death. (By the way, this sabbat’s name is pronounced “SOW-en,” not “Sam-HANE” as it appears in many movies and TV shows.)

Yule/Winter Solstice (December 21): Yule is a celebration of the return of light and life on the longest night of the year. Many Wiccans recognize Yule as the symbolic rebirth of the God, heralding the new plant and animal life soon to follow. Yule celebrations are based on Germanic traditions and have a lot in common with modern Christmas celebrations. Wiccans might celebrate Yule by decorating a Yule tree, lighting lots of candles or a Yule log, or exchanging gifts.

Imbolc (February 1): This sabbat, based on an Irish festival, is a celebration of the first stirrings of life beneath the blanket of winter. The spark of light that returned to the world at Yule is beginning to grow. Imcolc is a fire festival, and is often celebrated with the lighting of candles and lanterns. Wiccans may also perform ritual cleansings at this time of year, as purification is another theme of this festival.

Ostara/Spring Equinox (March 21): Ostara is a joyful celebration of the new life of spring, with ties to the Christian celebration of Easter. Plants are beginning to bloom, baby animals are being born, and the God is growing in power. Wiccans might celebrate Ostara by dying eggs or decorating their homes and altars with fresh flowers. In some covens, Ostara celebrations have a special focus on children, and so may be less solemn than other sabbats.

Beltane (May 1): Beltane is a fertility festival, pure and simple. Many Wiccans celebrate the sexual union of the God and Goddess, and the resulting abundance, at this sabbat. This is also one of the Celtic fire festivals, and is often celebrated with bonfires if the weather permits. The fae are said to be especially active at Beltane. Wiccans might celebrate Beltane by making and dancing around a Maypole, honoring the fae, or celebrating a night of R-rated fun with friends and lovers.

Litha/Midsummer/Summer Solstice (June 21): At the Summer Solstice, the God is at the height of his power and the Goddess is said to be pregnant with the harvest. Like Beltane, Midsummer is sometimes celebrated with bonfires and is said to be a time when the fae are especially active. Many Wiccans celebrate Litha as a solar festival, with a special focus on the God as the Sun.

Lughnasadh/Lammas (August 1): Lughnasadh (pronounced “loo-NAW-suh”) is an Irish harvest festival, named after the god Lugh. In Wicca, Lughnasadh/Lammas is a time to give thanks for the bounty of the earth. Lammas comes from “loaf mass,” and hints at this festival’s association with grain and bread. Wiccans might celebrate Lughnasadh by baking bread or by playing games or competitive sports (activities associated with Lugh).

Mabon/Fall Equinox (September 21): Mabon is the second Wiccan harvest festival, sometimes called “Wiccan Thanksgiving,” which should give you a good idea of what Mabon celebrations look like. This is a celebration of the abundance of the harvest, but tinged with the knowledge that winter is coming. Some Wiccans honor the symbolic death of the God at Mabon (others believe this takes place at Samhain or Lughnasadh). Wiccan Mabon celebrations often include a lot of food, and have a focus on giving thanks for the previous year.

Aside from the sabbats, some Wiccans also celebrate esbats, rituals honoring the full moons. Wiccan authors Janet and Stewart Farrar wrote that, while sabbats are public festivals to be celebrated with the coven, esbats are more private and personal. Because of this, esbat celebrations are typically solitary and vary a lot from one Wiccan to the next.

Further Reading

If you want to investigate Wicca further, there are a few books I recommend depending on which approach to Wicca you feel most drawn to. No matter which approach you are most attracted to, I recommend starting with Wicca For Beginners by Thea Sabin. This is an excellent introduction to Wiccan theology and practice, whether you want to practice alone or with a coven.

If you are interested in Traditional Wicca, I recommend checking out A Witches’ Bible by Janet and Stewart Farrar after you finish Sabin’s book. Full disclosure: I have a lot of issues with this book. Parts of it were written as far back as the 1970s, and it really hasn’t aged well in terms of politics or social issues. However, it is the most detailed guide to Traditional Wicca I have found, so I recommend it for that reason. Afterwards, I recommend reading Casting a Queer Circle by Thista Minai, which presents a system similar to Traditional Wicca with less emphasis on binary gender. After you learn the basics from the Farrars, Minai’s book can help you figure out how to adjust the Traditional Wiccan system to work for you.

If you are interested in Eclectic Wicca, I recommend Wicca: A Guide for the Solitary Practitioner and Living Wicca by Scott Cunningham. Cunningham is the author who popularized Eclectic Wicca, and his work remains some of the best on the subject. Wicca is an introduction to solitary Eclectic Wicca, while Living Wicca is a guide for creating your own personalized Wiccan practice.

Resources:

Wicca For Beginners by Thea Sabin

Wicca: A Guide for the Solitary Practitioner by Scott Cunningham

Living Wicca by Scott Cunningham

A Witches’ Bible by Janet and Stewart Farrar

The Study of Witchcraft by Deborah Lipp

#paganism 101#pagan#paganism#baby pagan#wicca#wiccan#traditional wicca#eclectic wicca#scott cunningham#thea sabin#janet and stewart farrar#witch#witchcraft#witchblr#baby witch#long post#mine#my writing#witches of tumblr

727 notes

·

View notes

Text

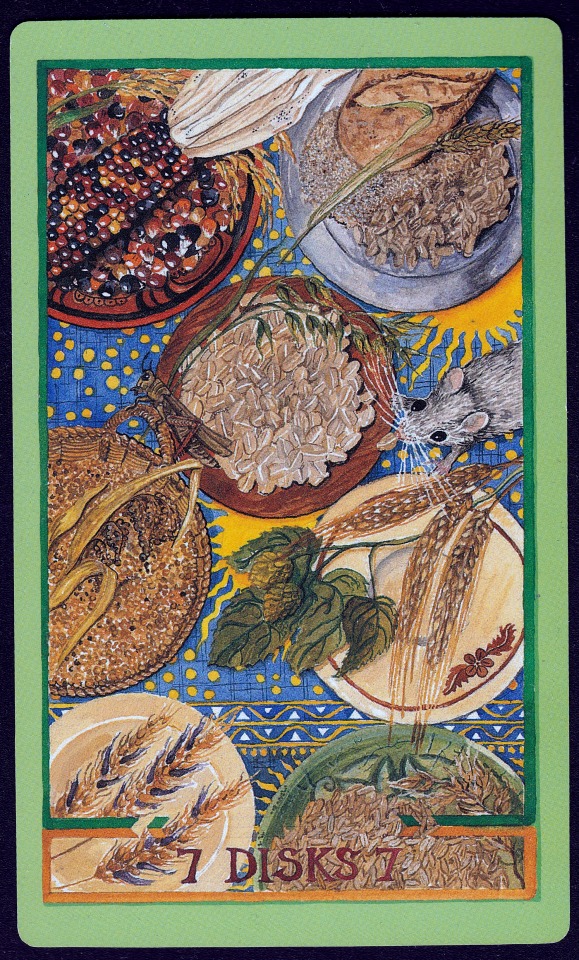

7 of Pentacles ~ Wheel Of Change Tarot

Grains from Around the World

Seven is the product of three and four, and it therefore symbolizes the combination of the solar four with the lunar three. Seven is the number of synthesis and the number of the macrocosm because of its relation to the seven ancient planetary bodies for whom the days of the week are named. Seven was the number of Athena, the virgin goddess of practical woman’s knowledge, and in the Pythagorean system it was considered the number of wisdom.

The heavenly sphere in which the seven planetary bodies moved was often thought of by the ancients as the heavenly corn mill. In Greek and Norse mythology there was a great goddess at the center of the cosmic millstone turning this cosmic wheel. Its continual turning was like the action of the mill; as it revolved again and again the Great Wheel created time while the earthly grain mill turned the grain to flour for bread.

Grain is symbolic of the total life of the plant. It embodies all forms of the Triple Goddess within it, for it is the death of the plant and embodies the crone, it is the edible fruit of the the nurturing mother, and it is the new seed and is symbolic of the virgin, not yet planted. Grain was a child of the Great Goddess and embodied her son as the universal grain god, who was sacrificed yearly and returned in the form of nourishing food and sacred beer. In Native American myth, Corn Woman was killed and dragged around a field, and where her blood spilled the first corn plants grew.

The grain embodies the soul of a people because life is dependent on it as the staple food of all. The sacrifice of the corn god symbolizes the cutting and harvest of something valued and sacred. The harvest is made with ceremony so as not to offend the spirit of the corn and to insure that the next harvest will be bountiful. In every culture the grain is honored; it is planted, reaped, milled, and used with respect for the spirit that lives within it. In cultures where alcohol is made from the grain—beer and whiskey from barley, sake from rice, and vodka from rye—the potent spirit of the god lived within the alcohol and entered you when you drank of his resurrected body.

In the Seven of Disks both the grain itself and the plate or basket are apt symbols for the disk. Any foodstuff may represent the suit of Disks, for food nourishes us and helps the physical body grow. The plate offers the food to us, frames the food, and keeps it from the ground; it is a way of distinguishing the food as sacred.

These seven grains from around the world—corn, wheat, oats, millet, barley, rye, and rice—show that although we all come from different cultures we are, in essence, the same. We all need grain to survive, and we all cultivate and honor the food we grow, investing it with symbolic value so that its nourishment is complete. This is a mirror of our unique qualities within the framework of humanity. People have such a strong relationship to their cultural grain that we automatically associate rice with China, oatcakes with Scotland, and corn with the native people of the Western Hemisphere.

The addition of the mouse and grasshopper is a reminder of the smaller creatures of the earth and their needs. The grasshopper is a summer pest and sometimes arrives in great swarms as the locust and destroys the grain crop. He is a symbol of chance and of the unpredictable nature of the world. He is the reminder that we are not the only species here and that nature is beyond our control. The grasshopper’s ownership of the land and its grasses is supreme, and we borrow the land from him.

The grain-loving mouse is a representative of the god Apollo, who originally had oracular shrines of mouse priestesses under the title Apollo Smin the us (“Mouse Apollo”). The mouse, bringer of disease, in sympathetic magic also brought its cure, and Apollo was credited as the god of medicine. Apollo was the god of the most famous oracular shrine at Delphi, which he got by challenging and defeating the goddess Python. To this day the snake perpetually chases the mouse, hoping for the return of her oracular shrine.

By classical times the little mouse god who ate the summer grain grew in importance and was associated with the sun as his twin sister Artemis was with the moon. Apollo was the lord of all that was bright: art, music, poetry, and the dance, and he was called Phoebus Apollo (“Shining Apollo”). Apollo was associated also with the Egyptian Horns (the son of the sun), and through these associations, in later classical times, Apollo was the personification of the sun. Apollo’s sun shines on the tablecloth beneath the plates as a symbol of the yearly course of the sun in the planting and harvesting of the grain. The sun is also like the grain in that its representative hero undergoes the sacrifice symbolized in the harvest of the grain. The life of the sun and the life of the grain are analogous, for many grains are planted in the dark of the year—buried in the darkness of the earth near the solstice—grow while the sun’s power grows, and are cut down as the sun reaches its peak in summer. The potent energy of the shining sun lives within the grain.

Δ When this card is a part of your reading, be aware of people’s unique qualities; just as rice is different from millet, so you are different from others. In doing this, see the golden sun within them and be sure to discover it within yourself as well. Recognize the little creatures and do them honor by seeing them as part of the web of life. When others need what you have, help them to provide for themselves by teaching them and showing the way.

This is also a card of personal nourishment, reminding you that you need nurturance both on the simple level of the physical and on the more complex levels as well. This is the macrocosmic view demanded by the seven. Find what feeds your soul: read, dance, write poetry, paint, eat well. Remember to honor that which feeds you, by ritual or with simple respect, treating whatever you use well: the paper you draw and write on, the instrument you play—and respect yourself. Live in the Apollonian mode of rational creativity. Like those who planted the grain and could see the yearly cycle, remember the cycles of time and honor them.

Alexandra Genetti. The Wheel of Change Tarot.

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

I saw your r recent contribution to the post about hard vs soft magic systems and I agree wholeheartedly. You also mentioned having a bunch of worldbuilding and stuff about the magic system, and I was wondering if you'd be willing to share some?

(For reference, this is the post in question)

Certainly! While the worldbuilding/magicbuilding hellscape i was describing in the notes is actually in regards to an original-content wip I've been working on, i also have a LOT of headcanons regarding the BBCM magic system too! (Do not ask about my wip's magic system, because i won't be able to shut up about it)

WARNING: long post ahead and mobile won't let me include a cutoff/read-more line. If you're not interested, get ready to scroll down like your life depends on it (and it does).

So! First things first. Here's what we know about the BBCM magic system:

Magic requires spells, most of the time. This seems like a no-brainer, but still an important distinction. There are a lot of magic systems that don't require vocalized spells - Avatar: the Last Airbender, Fullmetal Alchemist, and Ninjago, to name a few. Spells are rather common for wizard/witch/medieval fantasies, and are typically used to control and channel the intent of the magic. This suggests that the magic of BBCM is some kind of force or energy that needs spoken commands to control.

Spells are repurposed words from Old English, aka the language of the Old Religion. (Let's ignore the obvious anachronistic nightmare of the fact that Old English is exactly the same language they would've been speaking in this time period.)

The use of a spell causes someone's eyes to flare gold, plus that fancy wooshing sound effect that Arthur miraculously never hears. This suggests that magic somehow changes your physiology, although it could be also just be a side effect of channeling.

However, magic doesn't always require a spell. Though never fully explained, it appears to be something only innate magic users are capable of - Merlin, Morgana, Mordred. It is something less controllable than spellwork, typically governed by moments of strong emotion rather than logical intent.

The show consistently flip-flops between the idea that magic is something you're born with, and that Merlin is rare for being born with magic. It's never clarified just how someone acquires magic. Gaius asks Merlin where he studied, suggesting that it's something you can learn, while Balinor claims that you either have it or you don't. Though not confirmed fact, i suspect it's similar to how it works in the show Supernatural. There, some witches are natural-born, while others are taught (and some get their powers from spooky demon deals).

It has a life-for-a-life policy. Basically like the Law of Equivalent Exchange from Fullmetal Alchemist, a life cannot be created without another one being sacrificed first. This rule only canonically applies to creating life/the Cup of Life, and any other possible applications aren't addressed.

This rule apparently doesn't apply to animals, as Merlin brought a dog statue to life without killing anyone (that we know of), and Valiant's shield had three live snakes in it. However, it's possible that lives were taken as payment in the process of animation without Merlin's knowledge, but it never happens on screen so we don't know. So either a) animals don't have souls to exchange in the life-for-a-life policy, b) they do but it happens off-screen, or c) those animated animals aren't actually alive.

The Cup of Life infuriates me from a magicbuilding perspective. Ignoring the obvious question of how it came into the druids' possession, its existence isn't clearly defined. Does it require the fancy rain ritual that Nimueh gave it, or was she just extra? Why does drinking from it give you life, while bleeding into it makes you undead and also mindlessly obedient to the sorcerer who made you as such? Were there life-for-a-life consequences for creating an immortal army? Wtf happened on the Isle of the Blessed to allow Merlin to "master life and death", and what does that even mean? All valid questions that never get answered.

Spells sometimes need need a 'source'. Think the staff from "The Tears of Uther Pendragon" and Morgana from "The Fires of Idirsholas." It is unclear what makes these spells different/special.

There is a power hierarchy. Some spells are too powerful for some practitioners to cast, although the reason for this is unclear. Does it drain you of energy/life force? Do you exhaust/overwork your magic muscles? Do you get a little pop-up that says 404 Magic Not Found? Unclear.

Magic is something that can be trained and improved. For example, Morgana gradually became more powerful over time. Merlin naturally had a lot of power straight off the jump and just had to discipline it, but he's a ~special~ case so he doesn't count.

There are some subsets of magic that are definitively born traits. Morgana is a Seer, possessing this capability even before her magic manifested. Likewise, Merlin is a dragonlord, which he inherited from Balinor. Although Balinor did mention that it wasn't a sure thing he would have the ability until he faced a dragon, so there may be some variation in whether or not someone lucks out in the Magic Gene Pool. This may suggest that natural-born magic is hereditary, as both Morgana and her sister Morgause had it. Vivienne and Gorlois both probably didn't have it, otherwise you'd hear Uther bellyaching about it, which raises the question of where they got it? A grandparent, perhaps? Maybe they both carried a recessive magic gene or something...

Unless you're Merlin, magic can be taken away by the Gean Canagh. It's not explained how this is possible, though, as it's never explained how you acquire magic in the first place. But Merlin never lost his magic because he's "magic itself" which if you ask me is just a deus ex machina wrapped inside a headache wrapped inside a heaping load of chosen one bullcrap. But it's canonical lore, so we have to consider it.

Despite my previous complaints, i actually find the idea of Merlin being "magic itself" rather intriguing. Is he a creature of magic, like a dragon or a questing beast? Is his body made of magic, like how a statue might be made of clay? Does it run through his veins like blood? If this is the case, then why didn't he suffer more severe ramifications for losing his magic? Why didn't it kill him? How did it restrict his magic in the first place? Placebo effect? The fanon explanation is that he's "the living embodiment of magic" but that makes my bullcrap richter scale shoot off the charts because that makes NO sense whatsoever. "Son of the earth, sea, and sky?" What does that MEAN?

There is a vivid link between magic and the Old Religion, which has its own beliefs and rituals and deities. Primarily, the Triple Goddess. The Triple Goddess is actually an existing deity in Neopaganism and Wicca. This also suggests the existence of the Horned God, another entity from neopagan lore and her masculine consort/counterpart, but that is never confirmed.

WHO. OR. WHAT. IS. THE. FREAKING. DOCHRAID. She's described as a creature of magic, which suggests that humans/humanoids can be creatures of magic, fueling my theory that 'Emrys' isn't human.

Destiny exists. It is unclear who creates/writes destiny, who controls it, who or what is privy to knowing about it, and what that means for the concept of free will.

The crystal cave is a thing, i guess. It's the heart of magic, is haunted by Taliesin, and is filled with prophetic crystals. I actually skipped the episodes that involve this stuff because i disliked them, so i don't know much about the Crystal Cave. Apparently ghosts can manifest there tho???

The veil is a thing too. It is unclear how some spirits can retain their human figure and mentality, like Balinor and Uther, but others become dorocha. I imagine its also like Supernatural - being a ghost for long enough will drive you insane, and though it takes a while all spirits eventually turn into dorocha.

Creatures of magic exist. These are normal creatures who have magic imbued into them somehow.

Okay, i think that's everything we know. It seems like a lot, but keep in mind that all of those rules are VERY nebulous. But that at least gives us a jumping-off point!

So here's my working theory/headcanon.

Magic comes from a connection to the spiritual energies of the Triple Goddess. Kinda like a third eye, and for the sake of simplicity that's what we'll call it. The druids have adapted a way of life that revolves around faith and magic, likely in an attempt to cultivate and one day attain this Third Eye. Like Gaius, who trained with the High Priestesses, you can study and practice and discipline yourself into acquiring it.

Magic is a cosmic force owned by the Triple Goddess, accessible to anyone with the Third Eye link. Imagine the Triple Goddess as a milkshake and the so-called Third Eye as a straw. The studying and training that people dedicate their whole lives to is basically just looking for/building a straw.

However, some people are just naturally born with a straw in hand, but require practice and study to be able to properly use it. Or like Morgana, it takes a few years for them to even find it/activate it.

Spellcasting is essentially just sucking through the straw, and the vocalized spells gives that Magic Milkshake some purpose/intent/shape.

The bigger the spell, the more Magic Milkshake is required. Some people have bigger/wider straws than others, so magic comes easier for them. But with enough training and practice anyone can widen their straw/strengthen their straw-sucking muscles to cast with the big leagues.

The Gean Canagh devours your straw/Third Eye. Perhaps you have to rebuild a new spiritual connection from scratch, or perhaps it permanently severs any and all connection to the Triple Goddess. Like getting excommunicated from the Church, only worse.

The Crystal Cave was/is the Triple Goddess's home, but she's out of town on a business trip atm so she left the spirit of her most loyal follower, Taliesin, to look after the place. It's super powerful and has all those cool crystals because it's hella steeped in her magic juices.

While most magic users get a standard-issue straw, others get Fancy Premium Membership Straws. Normal joe shmoes like Gilli have plastic straws, while a Seer like Morgana has a metal one or something (can you tell this metaphor is starting to get out of hand?). Those Premium Straws are only hereditary in nature. So there's a Seer Straw, or a Dragonlord Straw, or a Disir Straw, but it's also not a sure thing you'll even inherit it at all. It's all luck of the straw draw.

Creatures of magic aren't just animals that possess straws, though. They've been made/produced using magic rituals and processes and spells. Like Nimueh's afanc, nathairs, wraiths, shades, etc. So probably like a thousand years ago, some especially powerful shmuck came by and invented dragons. Which leads me to an important question: WHO THE HELL THOUGHT THE DOCHRAID WAS A GOOD IDEA.

Im reluctant to say these creatures were invented by the Triple Goddess, though, for reasons I'll get to in a moment.

So this still leaves the whole Cup of Life, life-for-a-life policy thing to be explained. I do believe that the policy is universally applicable to the creation of souls, and i do believe that animals have souls too. But individuals get their souls exchanged for those of equal value. So every soul has a certain weight to it, and you need to exchange souls of equal weight to create one. So when Merlin brought the dog to life, some random dog somewhere dropped dead against his knowledge.

Creating undead armies involves killing them and then resurrecting them. That's what 'undead' means. Zombies. So yes, to raise an immortal zombie army, Morgause's spell probably caused a bunch of people around the world to mysteriously drop dead.

Which leaves two last things to explain: destiny and Merlin.

Destiny is, i think, a combined effort between human choice and supernatural predeterminism. That is, for the most part humans make their own choices, but there are occasions where the Triple Goddess has to step in and do some course correction. Uther starting the Purge was free will, but Arthur and Merlin's destiny was an act of divine damage control. The Triple Goddess sets destiny into motion and informs a chosen few about it.

Okay SO. That leaves Merlin. And this is the bit im kinda excited about.

The Triple Goddess is a reservoir of power, a cosmic force of spiritual energy intrinsicallu linked to the fabric of the universe. People can spiritually reach out and tune into/channel her supernatural frequencies. But as a milkshake cannot suck itself through a straw, the Triple Goddess likewise cannot cast a spell. She can influence destiny, but she can't physically cast any magic on her own. That's why she didn't create the creatures of magic.

So a few years ago, Uther hecked up big time. And people of magic, the Triple Goddess's followers and acolytes and straw connections, were dying in droves. I can imagine that all those Third Eye tethers snapping en masse was painful for her to go through. She relies on the tethers to remain connected to the real world, and if all the tethers snap then she will be cut off from Earth altogether. And Earth requires magic to continue existing/thriving, so that's kind of a no-no.

So, the Triple Goddess knew that the only way to save the world was through divine intervention. Thus began the destiny of the Once and Future King and Emrys. She knew humanity is bigoted so there was bound to eventually be a repeat of Uther, so she made OaFK resurrectable, so they could keep him on the bench in case anyone ever needs him again.

Where does Merlin/Emrys fall into things?

Well. The Triple Goddess knew that saving her people and the world would require an immense magical undertaking, something no ordinary magic user would be able to pull off. But she has the power, if only she could use it. But a human can. So the Triple Goddess decided to be reborn into the body of a dragonlord's son. Merlin. Emrys. Magic itself.

Of course, this whole Being Born As A Human Thing is tricky, and as anyone familiar with reincarnation knows, you don't usually recall your past lives. So she became Merlin, unaware that he was ever the Triple Goddess. (Although she did add a clause saying she'd be destined to remember her past life eventually, which got hecked up for reasons ill explain later)

That's why so many creatures of magic/magic users recognize Merlin by his presence, why thr druids carry such reverence for him. Whereas the sidhe and other individuals don't recognize him, because they are blinded by heresy. They may have a spiritual connection to the Triple Goddess, but do not use her magic as she intended, and she's too busy wearing jaunty scarves to excommunicate them herself.

Why get the Once and Future King involved when she could just save everyone herself? Well, the Triple Goddess prefers to let the humans keep their agency and save themselves, and would rather remain in the role of protector/helper. Its just her nature.

But if that's the case, then why did Arthur's destiny fail? It's simple: Kilgharrah.

Remember what i said about the Horned God, counterpart to the Triple Goddess? Yeah, that's Kilgharrah. Like the Triple Goddess, he's another power reservoir, but he's jealous because people worship her and not him. He is against everything she does and actively seeks the destruction of the Triple Goddess's magic/influence for Jealous Evil Reasons. To stop him, the Triple Goddess enlisted some of her followers to bind him into the body of a dragon (perhaps this is how dragons were created) so he would never be able to do that. Years later, the Purge happened and "Kilgharrah" got locked away, further cut off from his power.

When Merlin walked in, unaware that he used to be the Triple Goddess, Kilgharrah seized his chance at revenge and manipulated Merlin into setting him free. Then, once free, he decided to lay claim to the power vacuum left by the Triple Goddess's quasi-absence. He began controlling destiny in whatever limited capacities he could, using magic of his own to permanently bury Merlin's knowledge of his past life. Then he ensured that Arthur would die and the Triple Goddess's magic would never return. But since he doesn't have FULL control over destiny (his powers are still limited by his dragon form, after all), he couldn't rewrite the bit where Arthur gets benched in Avalon. He's probably conspiring with the sidhe to ensure Arthur stays trapped there forever, or else he would've come back a long time ago.

As for how the Gean Canagh took Merlin's magic...well, yes, it devoured his Third Eye straw, but those are created by a strong spiritual connection to the Triple Goddess. And since he's literally the big TG himself, all he had to do was find himself again (by returning to his old home, the Crystal Cave) to recreate a new one.

Over the last 1500 years, Kilgharrah/the Horned God has been steadily accruing followers and worshippers in the hopes that one will become strong enough to release TG's bonds on him. Then he can kill her once and for all and claim full dominion over the universe, with the sidhe to support him.

I imagine that's how Arthur's resurrection would happen - Arthur and the rest of the dead Round Table are in Avalon when they learn about the treachery and plot to kill Merlin/take over the world, and spend the next few hundred years fighting their way out of Avalon.

Okay, I think that just about covers it. God, that was long. Any questions?

#i should probably write a fic for this huh#bbc merlin#merlin bbc#merlin#bbcm#ask#magicbuilding#fish post

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

santa muerte: seeking the divine feminine

The changing of aeonic trends points at the unconscious embrace of a particular power or concept. What does that mean in the case of embracing the divine feminine? In most of nature, the male seeds the female of his species, enabling her to bear and raise her young. Feminine energy is thus often characterized as attractive and sexual, full of the creative fertile power that enables physical manifestation. It also encompasses the nurturing impulse, lending the wisdom and patience needed to raise the young of any species. When provoked, the female animal can be incredibly ferocious in defense of her young.

Of course, humans enjoy a greater role than animals, and in humans: the breadth of the divine feminine can be wholly explored. Often a Triple Goddess model is used, since the three different ages of the Goddess — maiden, mother and crone illustrate the different ages of a woman's natural life span and the roles most undertake in their lives.

These are not the only characteristics that the divine feminine embodies. Children usually learn the language and stories of their people at their mother's knee, and these teachings lay the foundations for how we relate to people and society as a whole.

As the creators and arbiters of these social connections, women also step into roles such as caregivers for the sick and for the elderly. When they themselves grow old, women become free to teach their grandchildren from the depths of their knowledge, or contemplate their own rebirth and renewal. When women pass on, they may take this depth of understanding with them.

Empathy and emotional intelligence are also both gifts of the divine feminine. These characteristics reduce conflict and maintain social cohesion, which can make the bonds formed between women incredibly strong. These strong social connections, coupled with the inborn desire to stay creative and a natural industriousness, created many lady merchants out of simple spinners and potters.

The underlying theme of all these characteristics is that feminine energy creates order out of chaos by giving chaos form and often by giving form in abundance. This is the idea behind goddesses of fertility, after all, who frequently found themselves associated with animals like pigs because they birth particularly large litters. The worship of the goddess Cybele from Neolithic Turkey is an excellent example. This mother goddess sprang into form from primordial chaos and then promptly gave birth to her own son and lover, Attis. With Attis's aid, Cybele gave birth to the rest of the gods and filled creation with her wonders. This concept is likewise echoed in the story of the Greek mother goddess, Gaia, whose own story is based on Cybele’s.

This ability to create from apparently nothing echoes in the other common functions of early goddesses that were revered worldwide. Many ancient goddesses were revered as the mistresses of the hearth and home, as well as the technical arts such as weaving and pottery that were often produced by women. These basic technologies made it possible for early tribes not only to clothe themselves, but also to store food for long periods. This capability freed them to develop the stories and traditions that laid the foundations of every society. Because mothers teach their children not only these skills but also the language and culture of their people, the divine feminine is also associated with wisdom and learning. This is another way in which the divine feminine also creates stability and growth out of chaos, and likewise why it is associated with earthly manifestation.

Many of the characteristics of the divine feminine — such as creative industry, empathy, and wisdom — are typically attributed to goddesses of form and fertility, such as Cybele and Freya. Their underlying concept is that they create out of nothing. Santa Muerte obviously takes a feminine form, but can she really be considered a particularly feminine figure given that death's principal power is to destroy?

While the female divine current is usually associated with creation and fertility, it also has an undeniable relationship with the force of death. The divine feminine current is recognized as the bearer of life and source of the earth's fertile abundance. It has likewise always been associated with the power of death. The animals that are born in the spring will be killed for meat that autumn, and the earth accepts the blood of their birth and slaughter both equally. The spilling of blood renews the earth's creative ability, preparing it for greener and more fertile crops in the coming spring.

The recognition of this ancient and powerful relationship dominated early human cultures. Some of the earliest recorded human rites were festivals dedicated to Cybele. These festivals featured soaking seeds in the blood of sacrificed animals to guarantee their strength and vigor. Male devotees of Cybele would even castrate themselves and bury their severed organs in the ground in an attempt to impregnate the earth itself. The idea that the earth was also the medium for human rebirth was likewise well established. This is also the reason some cultures buried their dead in a fetal position. Burying useful items such as food, clothing, weapons, and tools with the dead is also a common funerary practice. These grave goods were necessary for the dead s comfort and success in the next world.

Blood, birth, and death also have a special significance for people. In women, the relationship between blood, birth, and death is easily seen during their monthly menstrual cycles, a feature that is unique among humans. Childbirth itself is also a bloody and dangerous process. Birth trauma and puerperal infection have been leading causes of death for pregnant women even up until the 20th century. They remain a leading cause of death for women in poorer nations worldwide.

Numerous examples of birth and life arising from death and sacrifice exist within Aztec culture. The Aztec society was built on this fact. Without death, there could be no continuation of the cycles of birth and renewal, this idea was strongly represented in their mythology. One excellent example lies in the story of how the heavens and the earth were made. The Aztecs revered another goddess named Tlaltecuhtli, whose body made up the universe. Desiring to create a place for mankind, the other Aztec gods descended on her and tore her to pieces, stacking the parts together in such a way that made the earth and sky. The gods tried to console her that she would be fruitful and covered in trees and flowers, but she wept and refused to blossom. The gods resorted to drenching her in blood to appease her, and so repeated offerings of blood were thought to be the only way that the earth would remain in bloom.

The ancient Aztecs in particular recognized the struggle between life and death that played itself out during birth. Women giving birth were seen as brave warriors who were fighting the force of death itself. Those who survived childbirth were hailed as warriors. Those who died were revered as if they had been slain in battle. Their spirits were thought to be especially fierce and powerful. They were called mociuaquetzque (Nahuatl, “warrior in the shape of a woman”), and they were thought to guard the western passage into the underworld into which the sun was forced to descend every night. This was the precise same location that the goddess Mictecacihuatl ruled, according to the Aztec calendar.

Death and birth also have a very specific magical relationship. Without death, nothing new can be created. Decay feeds new life. Giving birth also plucks a person awaiting birth (or rebirth) out of the spirit world and gives him or her a body. Thus, goddesses of death become the gateway through which one passes at the end of life in order to be born into a new one. This makes goddesses of death just as necessary to turn the wheels of creation as the goddesses of life. The idea of creation requiring both birth and death is a common cultural concept.

While the goddesses of death make excellent gatekeepers to the next life, would you want them present at a birth also? Many cultures went to great pains to bribe the gods and spirits of the dead to stay away from birthings because both mother and baby were at risk of being taken by them. In some cases, their attendance was required, though. For the Romans, the three Parcae, or Fates, attended the birth of every child to measure and cut the thread of his or her destiny. The goddess that cut the thread was normally called Parca Morta, but in the circumstances surrounding a birth, she was referred to as Parca Partula instead. We derive words such as postpartum from the same goddesses from whom we get words like mortuary.

The vast majority of Santa Muerte's origin stories give her a strong maternal foundation. This nature is seen clearly in her European roots where the goddess who cuts the threads of fate lends her name to the words surrounding birth. Mictecacihuatl was charged with protecting all the future infants of the next age of humanity. The Codex Borgia also groups her among a variety of goddesses who are shown breastfeeding their infants. The orishas with which she is typically grouped among the African ritual traditions, such as the fiery patroness of the cemeteries, Oya, also have strongly maternal characteristics. The followers of Santa Muerte recognize that death is present at all times and therefore welcome her at the births of their children. Because Santa Muerte is seen as fiercely maternal, many devotees routinely ask the Saint of Death to guard and guide their children.

Death alone might be characterized as a relentless and entropic force, giving neither credence nor care to anything that it destroys in its path. When death's capacity to destroy is tempered with feminine qualities, a far more selective form of death is created. This form is seen in Santa Muerte. Despite her having nearly limitless power to obstruct or destroy, her touch can be surprisingly gentle and selective. Because she is quite wise, she is able to empathize with the people with whom she interacts. This capacity inspires her to lean toward mercy and teaching instead of wanton destruction. Santa Muerte is less likely to viciously cull than she is to carefully prune, gently shaping the outcomes of people and their circumstances instead. Finally, the Saint of Death clears new ground so that life may flourish.

Some devotees find it useful to see Santa Muerte in terms of the common Triple Goddess model with which many magical practitioners are familiar. The most obvious association related her back to the crone because Santa Muerte is a patroness of death. Like other crones, Santa Muerte is well capable of teaching hidden wisdom and inspiring lasting spiritual transformations. She also encompasses the other two aspects of the Triple Goddess model. Santa Muerte can be easily viewed in terms of the Maiden. The reason is that Death creates the opportunity for change, allowing for new and fresh beginnings. This is a very Maidenly characteristic. Santa Muerte also famously lusts for love, beauty, and pleasure, which are things frequently attributed to the Maiden portion of the model. Finally, Santa Muerte is frequently seen as a gentle, nurturing, and empathetic character, all qualities that are commonly associated with the Mother aspect. Thus it is clear that Santa Muerte encompasses a full range of feminine characteristics in terms of the Triple Goddess model.

(Tracey Rollin. Santa Muerte: the history, rituals and magic of Our Lady of Holy Death, pages 59-66)

#santa muerte#tracey rollin#seeking the divine feminine#triple goddess#empathy#emotional intelligence#cybele#gaia

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Grains from Around the World

Seven is the product of three and four, and it therefore symbolizes the combination of the solar four with the lunar three. Seven is the number of synthesis and the number of the macrocosm because of its relation to the seven ancient planetary bodies for whom the days of the week are named. Seven was the number of Athena, the virgin goddess of practical woman’s knowledge, and in the Pythagorean system it was considered the number of wisdom.

The heavenly sphere in which the seven planetary bodies moved was often thought of by the ancients as the heavenly corn mill. In Greek and Norse mythology there was a great goddess at the centre of the cosmic millstone turning this cosmic wheel. 46 Its continual turning was like the action of the mill; as it revolved again and again the Great Wheel created time while the earthly grain mill turned the grain to flour for bread. Grain is symbolic of the total life of the plant. It embodies all forms of the Triple Goddess within it, for it is the death of the plant and embodies the crone, it is the edible fruit of the nurturing mother, and it is the new seed and is symbolic of the virgin, not yet planted.

Grain was a child of the Great Goddess and embodied her son as the universal grain god, who was sacrificed yearly and returned in the form of nourishing food and sacred beer. In Native American myth, Corn Woman was killed and dragged around a field, and where her blood spilled the first corn plants grew.

The grain embodies the soul of a people because life is dependent on it as the staple food of all. The sacrifice of the corn god symbolizes the cutting and harvest of something valued and sacred. The harvest is made with ceremony so as not to offend the spirit of the corn and to insure that the next harvest will be bountiful. In every culture the grain is honoured; it is planted, reaped, milled, and used with respect for the spirit that lives within it. In cultures where alcohol is made from the grain— beer and whiskey from barley, sake from rice, and vodka from rye— the potent spirit of the god lived within the alcohol and entered you when you drank of his resurrected body.

In the Seven of Disks both the grain itself and the plate or basket are apt symbols for the disk. Any foodstuff may represent the suit of Disks, for food nourishes us and helps the physical body grow. The plate offers the food to us, frames the food, and keeps it from the ground; it is a way of distinguishing the food as sacred.

These seven grains from around the world— corn, wheat, oats, millet, barley, rye, and rice— show that although we all come from different cultures we are, in essence, the same. We all need grain to survive, and we all cultivate and honour the food we grow, investing it with symbolic value so that its nourishment is complete. This is a mirror of our unique qualities within the framework of humanity. People have such a strong relationship to their cultural grain that we automatically associate rice with China, oatcakes with Scotland, and corn with the native people of the Western Hemisphere.

The addition of the mouse and grasshopper is a reminder of the smaller creatures of the earth and their needs. The grasshopper is a summer pest and sometimes arrives in great swarms as the locust and destroys the grain crop. He is a symbol of chance and of the unpredictable nature of the world. He is the reminder that we are not the only species here and that nature is beyond our control. The grasshopper’s ownership of the land and its grasses is supreme, and we borrow the land from him.

The grain-loving mouse is a representative of the god Apollo, who originally had oracular shrines of mouse priestesses under the title Apollo Smin the us (“ Mouse Apollo”). The mouse, bringer of disease, in sympathetic magic also brought its cure, and Apollo was credited as the god of medicine. Apollo was the god of the most famous oracular shrine at Delphi, which he got by challenging and defeating the goddess Python. To this day the snake perpetually chases the mouse, hoping for the return of her oracular shrine.

By classical times the little mouse god who ate the summer grain grew in importance and was associated with the sun as his twin sister Artemis was with the moon. Apollo was the lord of all that was bright: art, music, poetry, and the dance, and he was called Phoebus Apollo (“ Shining Apollo”). Apollo was associated also with the Egyptian Horns (the son of the sun), and through these associations, in later classical times, Apollo was the personification of the sun. Apollo’s sun shines on the tablecloth beneath the plates as a symbol of the yearly course of the sun in the planting and harvesting of the grain. The sun is also like the grain in that its representative hero undergoes the sacrifice symbolized in the harvest of the grain. The life of the sun and the life of the grain are analogous, for many grains are planted in the dark of the year— buried in the darkness of the earth near the solstice— grow while the sun’s power grows, and are cut down as the sun reaches its peak in summer. The potent energy of the shining sun lives within the grain.

Δ When this card is a part of your reading, be aware of people’s unique qualities; just as rice is different from millet, so you are different from others. In doing this, see the golden sun within them and be sure to discover it within yourself as well. Recognize the little creatures and do them honour by seeing them as part of the web of life. When others need what you have, help them to provide for themselves by teaching them and showing the way.

This is also a card of personal nourishment, reminding you that you need nurturance both on the simple level of the physical and on the more complex levels as well. This is the macrocosmic view demanded by the seven. Find what feeds your soul: read, dance, write poetry, paint, eat well. Remember to honour that which feeds you, by ritual or with simple respect, treating whatever you use well: the paper you draw and write on, the instrument you play— and respect yourself. Live in the Apollonian mode of rational creativity. Like those who planted the grain and could see the yearly cycle, remember the cycles of time and honour them.

Genetti, Alexandra. The Wheel of Change Tarot

3 notes

·

View notes