#tenet web weaving

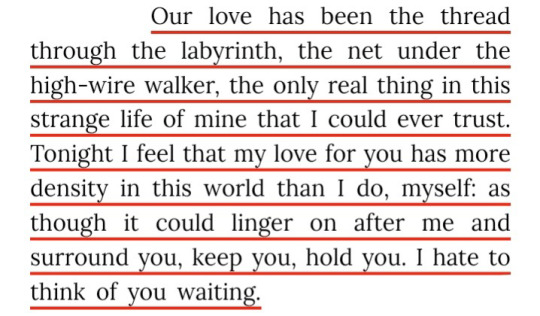

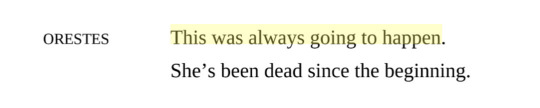

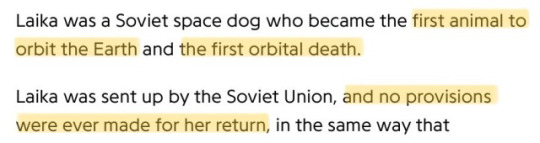

Text

tenet (2020), christopher nolan / the time traveller’s wife, audrey niffenegger / the oresteia, aeschylus / legend, marie lu

#tenet#tenet web weaving#christopher nolan#robert pattinson#john david washington#tenet movie#web weaving#words#film#red string of fate#someone has to leave first#time travel#time web weaving#this movie was so bad for me

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

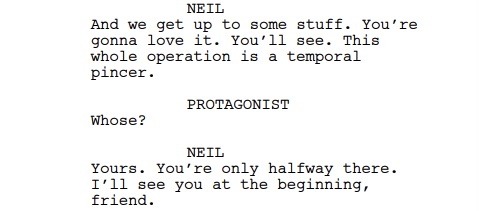

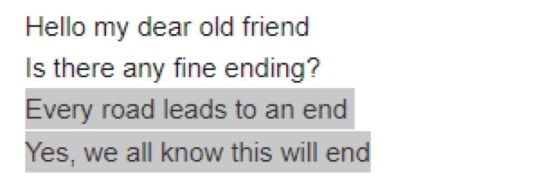

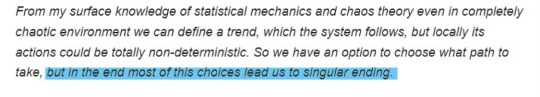

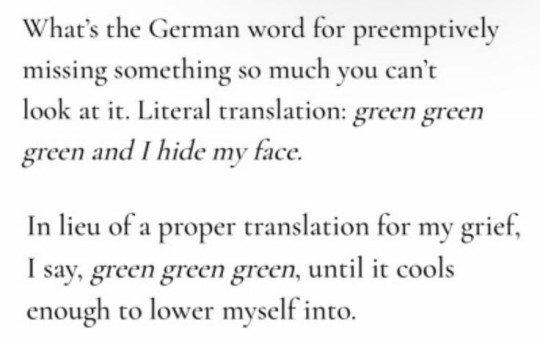

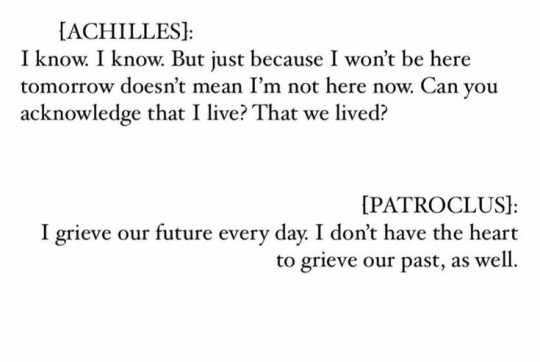

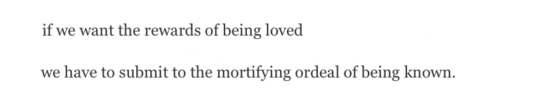

on mourning an ending that isn’t an ending

gang gang schiele, hyukoh / reddit user fridge_escaped on determinism vs free will / tenet, christopher nolan / margaret atwood / war of the foxes, richard siken / tumblr user fairycosmos / angels in america, tony kushner / champion, marie lu

#tenet#tenet 2020#christopher nolan#the protagonist#protagoneil#neil my beloved#web weave#webweaving#like idk if this makes sense or if anyone cares but i just watched this movie and it made me want to DIE#time travel#words#poetry#this is my first web weave AND post ever so be nice#literally ive been obsessed with web weaving for years and now i finally found something worth making one for god bless#mine#web weaving

508 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Restropect: January was a train wreck

via Pinterest // Aeschylus tr. Robert Icke // Tenet (2020) dir. Christopher Nolan // Euripides tr. Anne Carson // @sikenarthistory // Anne Lamott // Richard Siken // Panic! at the Disco // via Pinterest // My Chemical Romance

#yes the ''the end'' part is at the beginning on purpose. what of it#Lu rambles#web weaving#uhhh let's see. aesthetic tags#compare case histories#red string of faith#tenet

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

Usher Pt III-Ghost Quartet Dave Malloy// The Kingdoms Natasha Pulley// Tenet Christopher Nolan// The Photograph-Ghost Quartet Dave Malloy//

#web weaving#ghost quartet#the kingdoms#tenet#I am probably one of 20 people who cares about all three of these pieces of media but like they live in my head

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

The famous "birds and bees" speech is an complex and witty lead-in to the song "Monstrance Clock". In any variation, it leads to the celebration of orgasm, which is the hidden content of the song. I've always marveled at how cleverly Papa weaves the web of his reflection, managing to covertly lay out in 9 minutes not only the banal "let's fuck" message but also a whole range of ideas that are very likely his personal beliefs. If you remember this speech well in its various versions, you can pick them out:

Censorship is hypocritical and useless: children will learn all the taboo topics anyway, or they already have.

Societies that censor sexual pleasure are backward and imbecilic. Enjoying sex is a good thing, and should not be restricted.

The conservative stratum thinks rock music and worship of evil (black mass) are the same thing. Just look at these narrow-minded people!

All forms of love are equal (support of gays and lesbians); encouragement of healthy equal relationships.

In fact, these are tenets of liberal ethics. What appears to be chatter actually contains ideological messages. Papa is not just an ambassador of female orgasms and a sex doll on stage. He is a preacher of liberal values: progressive social ideas, respect for individuals and their diversity, freedom of speech and self-expression. He opposes outdated medieval prejudices and narrow-minded conservatives. I think we can say that he is a man with strong convictions and an equally strong intention to promote them to the masses. I'll give more examples of that next time.

And he also said in plain text that he gets turned on by inexperienced partners 👀 fic-writers, you know what to do.

[part 3] ... [part 5]

#terzo: observations#papa emeritus iii#terzo#the band ghost#ghost#papa emeritus 3#papa emeritus#papa emeritus lll#ghost band#ghost bc#papa iii#terzo emeritus#ghost lore

127 notes

·

View notes

Note

🌟 (and also sending the most love my dear darling friend!! 💖💖💖)

omg Eden!!! Thank you for playing!!!!

Your Austen heroine: Jane Bennet

I feel like this choice will not surprise you though I'm pleasantly hopeful that my reasons will be interesting and new at least! Jane is often a character who is slapped onto the sweetest and most supportive people without much thought but I've really had time to reflect on her character more as I've started teaching Pride and Prejudice and I think she fits on a deep level for you!! And yes, I absolutely think that the sweetness and the general Belovedness of Jane are so right for you as is the determination to see the good, celebrate the good, define the good, and love the good. That is a central tenet of Jane's life AND yours and is the reason (and a very good one) for the Belovedness. Jane would make web weaves i KNOW SHE WOULD. She would remember (does remember!) everything about everyone the way that you do and she's such a kind friend and SISTER. You and Jane: I feel like your central essence is that of sister!!!!!

But it's actually also the deep thoughtfulness in her approach to life combined with a refusal to let go of the optimism that really strikes me as being so Eden-coded. Jane is the not the way that she is because she doesn't think about things. She simply want to think about things in the kindest and best light. It's a choice made every single day. Also !!!! She does have an arc!!! Jane's arc is so gentle in comparison to Lizzy's because Jane did NOT need her entire worldview upended the way that Lizzy did. But it is there! And I think her story, as it involves change, revolves around Caroline. That moment at the end when Jane admits to Lizzy that Caroline never wanted to be her friend and was wrong for pretending she did is the moment where we know Jane at the end is not Jane at the beginning. The thing I love about it is that Jane is still Jane, the sweetness, the optimism, the hope don't disappear with her acknowledging Caroline's villainy. And she does so simply and with so much grace. She also doesn't want to stay in the moment lol. She is quick to move on to happier things. Tumblr is not the place where I would see that moment for you playing out in real time, because you, unlike me, do not air all your bitternesses and hurts here. You're not a ranter! but I imagine that it has happened to you and the thing is: I think you would be so Jane about it!! I think that you are so Jane about it!! You don't let go of that central tenet even as you take in all the information to keep expanding your worldview, which unfortunately includes the reality of evil and fakeness. My alternate pick for you was Cathy! For this very reason. Because Cathy goes on that journey too but I think the core is more Jane.

<3

#Also I'd never thought about it but I hope you do have a Lizzy (or many Lizzy's!) around you!#but maybe that is the tumblr circle#love you honey#send me a star and I'll tell you which Austen hero/heroine you are!

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well, Victor Timely sure knows how to draw attention and eventually make some money. And make me write another post on a partially scientific topic. I’m not an expert tho!

On the right side of the stage there's a sign, 'Electrifying achievement to harness the power of time'

And then he explains what the Loom does. 'My temporal loom inverts the temporal decay of the electricity flowing through it, lowering its entropy and gathering it into fine threads of power. Which it then weaves into elegant ropes of voltage. A chaos of particles is transformed into order.'

(I'm gonna assume he quotes OB's guidebook and not just wings it all randomly, because at least a part of what he says made sense to me)

In short, he says that the Loom can arrange matter into an ordered state. And that it not only uses electricity but also reproduces it in a form of threads and ropes. That would explain how the TVA operates outside of uh time and why it has power surges in s2e1. But it still leaves the question from where comes the initial energy to kick start the loom.

I believe that the temporal decay is synonimous to the increasing entropy. Entropy is a measure of how many ways there are possible to rearrange the same amount of matter without changing its 'shape'. Simply put, objects with low entropy can't be rearranged without being broken/reassembled. And those with high entropy can be rearranged without changing its form or shape, so to speak. Prof. Brian Cox compares the former with a sand castle and the latter with a pile of sand 👌 Another important point is that entropy inevitably increases over time: order becomes disorder. BUT. If we go back in time — and not like in Doctor who but like in Tenet — then we would observe entropy again, increasing relative to us (and not decreasing if we observe it from the present into the past).

Now, I think that raw time, as OB named it, is energy with high entropy and a physical timeline is rearranged energy with low entropy. When a timeline branches, entropy increases again. Also, temporal radiation means a form of energy that travels from a source through space.

(Side note. My initial guess was: to isolate a timeline HWR would need to have something threaded. Which would mean that the Loom came first. But when the timeline branches it creates more input INTO the Loom. And what’s more, in the end of s1 the Sacred timeline branches into a web which resembles the raw time. Just like Timely said, ‘the energy of the past, present and future flows all around us.’ And HWR managed to harness it to sustain his big project. So, raw time/sacred/other timelines exist as they are, and the Loom is just a tool to operate the former)

(Side note 2. The Sacred timeline doesn’t consist of just one universe. It’s weaved from multiple but strictly selected multiversal timelines. Otherwise we’d see minutemen in previous movies)

I can accept temporal auras which can help track and pull someone across space-time. Or temporal radiation, which is itself a fun concept. But what puzzles me the most is time being a form of matter. In our reality, at least according to the current physics, it’s a dimension. I can’t wrap my head around it. Even in a fictional way, i can’t explain it to myself. Because I experience time the same way people do in the show. I think here Timely either simplifies so to make people understand and buy his Loom or he doesn’t know what he’s talking about.

And that’s why, until proven otherwise or explained by OB, I think that the Loom is first of all just a big power generator. The timelines are being pruned manually by time cops setting time bombs and arresting variants. Resetting a timeline means removing entropy that was created by a variant’s actions. The Loom generates energy for the TVA, people working there and their equipment. And maybe it charges Kang’s time chair.

The multiverse doesn’t need the Loom to function. Time flows on its own, entropy increases all the time, it’s far more inevitable than Thanos. Loom is a tool, it can be removed, repaired or upscaled. The TVA as organisation and people and city (?) all need it but, most of all, the person behind it.

#loki series#loki season 2#loki spoilers#kang the conqueror#victor timely#he who remains#loki meta#LWR's theories

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Neoscatology: Unveiling the Transgressive Frontier

Origins and Core Tenets:

Neoscatology emerged as a response to the rapid advancements in technology and their impact on human consciousness. Siratori defines Neoscatology as a fusion of technology, post-humanism, and the exploration of the grotesque. The term "scatology" refers to the study of excrement, symbolizing the darker aspects of human existence. Neoscatology aims to transcend traditional narrative structures and embraces a fragmented, nonlinear approach to storytelling.

Themes Explored in Neoscatology:Post-Humanism and Technological Integration: Neoscatology delves into the dissolution of the boundaries between humans and technology. It envisions a future where individuals merge with artificial intelligence, genetic modification, and virtual realities. Siratori's works portray a dystopian world where characters grapple with their fading humanity in the face of a technologically dominated society. Hyperconnectivity and Information Overload: Neoscatology reflects the hyperconnected nature of modern society. It explores the overwhelming influx of information, blurring the lines between reality and the virtual realm. Siratori's narratives present characters entangled in a web of fragmented data, highlighting the challenges of navigating a digitally saturated environment. Transgression and the Grotesque: Neoscatology confronts societal taboos and pushes the boundaries of acceptability in art. Those works embrace extreme violence, sexual deviancy, and visceral imagery, aiming to expose the darkest recesses of human consciousness. By delving into the abject, Neoscatology challenges established norms and provokes a visceral response from readers.

Stylistic Elements of Neoscatology:Fragmented Narratives and Nonlinear Structures: Neoscatological works employ a fragmented narrative style, weaving together multiple perspectives, thoughts, and emotions. The nonlinear structure mimics the disorienting nature of human cognition in an increasingly digital world. Disjointed Syntax and Unconventional Language: Neoscatology disrupts traditional language structures, employing disjointed syntax, unconventional grammar, and neologisms. This experimental use of language reflects the fragmented and disorienting aspects of a technology-driven society. Collage Aesthetics and Multimedia Integration: Neoscatological works often incorporate collages, blending different media, including text, images, and symbols. This collage-like approach symbolizes the fragmented nature of reality, incorporating multiple perspectives and voices to create a chaotic yet cohesive narrative.

Impact and Significance:

Neoscatology stands as a significant and influential movement within cyberpunk literature. Its transgressive nature challenges societal norms and pushes the boundaries of acceptability in art. Neoscatology offers a critique of our technologically driven society, raising questions about the potential consequences of unchecked technological progress.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Digital Revolution: Insights into the Core Concepts of Computer Science

Introduction:

In the whirlwind pace of technological evolution, the Digital Revolution stands as a catalyst, reshaping the very fabric of our existence. At its core, this revolution is fuelled by the foundational tenets of computer science, propelling transformative innovations in information technology that now permeate every facet of our daily lives.

Delving into the Foundations of Computer Science:

At the epicentre of the Digital Revolution lies computer science, an expansive discipline weaving together a tapestry of concepts instrumental in shaping the technologies that define our contemporary world. From the intricacies of algorithms and data structures to the groundbreaking realms of artificial intelligence and machine learning, computer science is the architect of the innovation landscape within information technology.

Decoding Algorithms and Data Structures:

Algorithms, the meticulous blueprints for problem-solving, and data structures, the architects of data organization and storage, are the elemental constituents of computer science. These concepts are pivotal in sculpting efficient and optimized solutions, influencing realms as diverse as search engine algorithms and the intricate dance of data processing in information technology.

The Rise of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning:

In the ever-evolving landscape of the Digital Revolution, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) emerge as the stars of the show. These branches of computer science empower machines to learn from data, make informed decisions, and execute tasks without explicit programming. AI and ML applications, ranging from natural language processing to cutting-edge image recognition, stand as the driving force behind the relentless innovation in information technology.

Coding and the Symphony of Programming Languages:

The soul of computer science resonates in the symphony of coding and programming languages, serving as the communication bridge with computers. From foundational languages like C and Python to specialized tongues like SQL for database management, mastery of these languages is a prerequisite for those embarking on the journey into the expansive universe of information technology.

Navigating the Web of Computer Networks and Cybersecurity:

In the intricate web of the Digital Revolution, computer networks act as the connective tissue facilitating communication and data exchange. Profound insights into network protocols, security mechanisms, and the principles of cybersecurity are imperative for safeguarding the expansive landscape of information technology.

The Symbiosis of Computer Science and Information Technology:

Interwoven like threads in a tapestry, computer science and information technology form a symbiotic relationship. While computer science lays the theoretical foundation, information technology executes practical applications. This seamless integration has birthed technological marvels, including the rise of cloud computing, the ubiquity of the Internet of Things (IoT), and the transformative potential of big data analytics.

Conclusion:

As we navigate the uncharted waters of the Digital Revolution, the imperative for a robust understanding of computer science fundamentals becomes increasingly apparent. From the poetry of coding and algorithms to the dynamism of artificial intelligence and the vigilance of cybersecurity, these core concepts are the architects shaping the contours of our digital destiny. Embracing these fundamentals not only opens the door to innovation but also empowers individuals to be active contributors to the ongoing metamorphosis of the Digital Revolution.

0 notes

Text

Can't believe that it's gonna be a web weaving thing that will convince me actually watch Tenet (because it makes a parallel (?) with Arrival).

Tumblr really is much stronger than any marketing team.

1 note

·

View note

Text

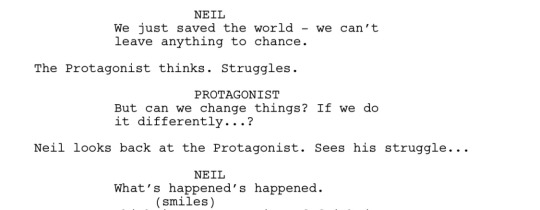

it's written down. you are the beginning of my end. i am the end of your beginning.

howl's moving castle / richard silken / tenet / ouroboros / anne carson

#web weaving#parallels#compilation#webweaving#tenet#howls moving castle#richard silken#anne carson#made by maju#robert pattinson

798 notes

·

View notes

Text

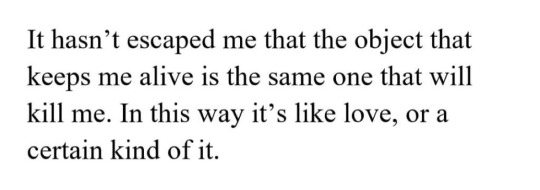

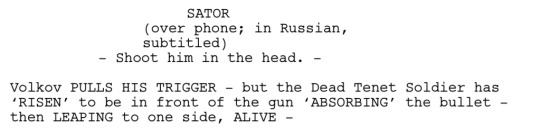

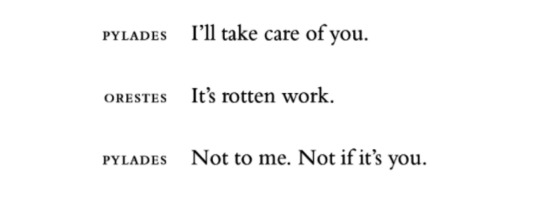

on sacrifice

1 samuel 20:3 / tenet, christopher nolan / animals that changed history / margaret atwood / the leash, ada limón / st. jude, florence and the machine / prayer, jorie graham

#tenet#tenet 2020#protagoneil#web weaving#web weave#sacrifice#another one bc im insane#is this coherent?? rofl#im too busy to write fics lately so this is my new outlet#never thought that i would bring the bible into this but jonathan and david is an exception#mine

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

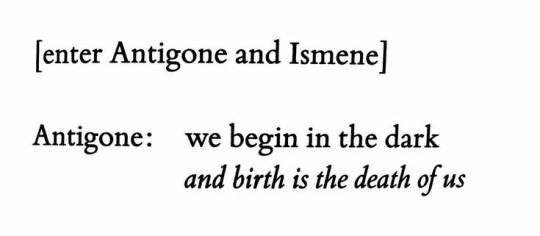

τραγῳδίες | Goat Songs

Sophokles tr. Anne Carson // Aeschylus tr. Robert Icke // Franny Choi // Quora answer // Richard Siken // source not found // Muse Lee & Aaron Reed // Richard Siken

#btw whenever i say ''source not found'' please know that I've usually spent like an hour searching for a source and still not found it#so if anyone knows where those quotes are from let me know so i can fill in those source slots#Lu rambles#web weaving#no this isn't about anything specific haha no why would you think that haha... ha....#actually it is kinda just an expansion of the set of quotes i dug up for magpie a while back#only vaguely related to my tenet thoughts tbh i just got thinking about tragedies and circular narratives again#however if i can find a way to apply planet of love (you're going to die in your best friend's arms) to anything? trust me i WILL#you didn't think you'd feel this way..#compare case histories

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

i want you by mitski is literally the perfect, most protagoneil song ever of course im crying as i type this

#protagoneil#neil tenet#the protagonist#tenet#mitski#need to make them a web weaving or something theres so many thing i can play with

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

1. phoebe bridgers - “savior complex” // 2. penny and sparrow - “duet” // 3. tim krieder - “i know what you think of me” // 4. anne carson - “euripidies, from ‘orestes’, an orestia” // 5. tim kreider - “i know what you think of me” // 6. @giidas - “the only way to measure time”

#phoebe bridgers#penny and sparrow#anne carson#euripides#tim kreider#i know what you think of me#giidas#protagoneil#tenet#my post#poetry#poetry compilation#web weaving#parallels#compilation

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Treat Your S(h)elf

The Places In Between by Rory Stewart

“I offered Asad money but he was horrified. It seemed a six-hour round trip through a freezing storm and chest deep snow was the least he could do for a guest. I did not want to insult him but I was keen to repay him in some way. I insisted, feeling foolish. He refused five times but finally accepted out of politeness and gave the money to his companion.Then he wished me luck and turned up the hill into the face of the snowstorm."

- Rory Stewart

Just weeks after the fall of the Taliban in January of 2002 Scotsman Rory Stewart began a walk across central Afghanistan in the footsteps of 15th Century Moghul conqueror Emperor Babur and along parts of the legendary Silk Road, from Herat to Kabul. He'd find himself in the course of twenty-one months encountering Sunni Kurds, Shia Hazala, Punjabi Christians, Sikhs, Kedarnath Brahmins, Garhwal Dalits, and Newari Buddhists. He said he wanted to explore the "place in between the deserts and the Himalayas, between Persian, Hellenic, and Hindu culture, between Islam and Buddhism, between mystical and militant Islam." He described Afghanistan as "a society that was an unpredictable composite of etiquette, humour, and extreme brutality."

The Places in Between is Stewart's account of walking across Afghanistan from Herat to Kabul in January 2002. The book was the winner of the Royal Society of Literature Ondaatje Award and the Spirit of Scotland Award and shortlisted for the Guardian First Book Award, the John Llewellyn Rhys Memorial Prize and the Scottish Book of the Year Prize.

I first read the book as a teenager a few years after it came out when I was spending a few months doing voluntary work for an Afghan children’s charity in Peshawar, Pakistan with my older sister who was a junior doctor at the time.

I read it on the rocky bus ride from Peshawar, Pakistan and into Afghanistan from Jalalabad to Kabul with my sister and her colleagues. I avidly read the book because I already knew the author through my oldest brother but from a distance because of our respective ages. Little did I realise then that I would be back in Afghanistan a few years later but this time in uniform doing my tour in Afghanistan flying combat helicopters against the Taliban.

I had the book with me (but a newer copy) and it took on a greater prescience precisely because as soldiers, even from the most senior officers on down, we privately questioned what the hell were we really accomplishing in a country ravaged by war since the Soviet invasion in 1979 (and that’s being generous given how history has buried empires into the graveyard of Afghanistan as a testament to their hubris).

Maybe it was hubris or perhaps it was that adventurous strain that needs to be scratched that led Rory Stewart to undertake his madcap journey. Stewart did the entire journey on foot, refusing any other form of transportation (and at one point going back and redoing a section of the walk when he couldn't turn down a vehicle ride). He took an uncommon route straight through the centre of the country and the heart of the mountains, instead of the more common route through the south that bypasses the dangerous mountain passes. This choice was partly because it was shorter, partly because the south was still partially controlled by the Taliban, and partly I suspect (though he doesn't say this explicitly) because it's the less-discussed and less-known route, even today.

This is, therefore, a sort of travel book, describing places that 99.99% of readers in the Western world are very unlikely to ever go. It's also unavoidably political, since Afghanistan is unavoidably political. However, unlike many travel books and many books with political overtones, it's carefully observational, documentary, and quietly understated in a way that gives the reader room to analyse and consider. Stewart focuses on his specific journey and concise, detailed descriptions of what he encountered and lets any broader implications of what he saw emerge from the reader's evaluation. He describes how he reacts to the remarkable natural beauty and almost-forgotten ruins that he encounters, giving the reader a frame and a sense of the emotional impact, but he's not an overbearing presence in the book. The story is clearly personal, but he doesn't dominate it. This is a very difficult line to walk, and I don't recall the last time I've seen it walked as deftly.

Instead there is a real sense that the author has gotten over the novelty of travelling and is more focused on the fundamental circumstances he encounters. The book overall is a fascinating read and there is much to be learned about the epistemologies driving the Afghan people and how different interpretations of Muslim teachings (and likewise, any teachings) can create small, but significant differences between neighbours. He has a gift for vividly describing the people and the landscape without injecting himself too much into the scene.

I suspect every reader will take different things from The Places in Between.

For some readers unaccustomed to the culture of Afghanistan, they would find it distressing to read how dogs are treated in Afghanistan. It's said Prophet Muhammad once cut off part of his own garment rather than disturb a sleeping cat. Unfortunately, he didn't feel equal affection for dogs, and they're "religiously polluting." They're not pets, and they're never petted. A quarter of the way in his journey Stewart has a toothless mastiff pressed upon him by a villager and he named him Babur. The evidence of past abuse could be seen in missing ears and tail, and someone told Stewart the dog was missing teeth because they'd been knocked out by a boy with rocks. Stewart found the dog a faithful companion and said he'd call him "beautiful, wise, and friendly" but that an Afghan, though he might use such terms to describe a horse or hawk would never use it to describe a dog.

But I knew all this growing in Pakistan and India as a small girl. Friends would look perplexed that we Brits - or any Westerners - have dogs or cats as pets and even see them as part of the family.

For me though two big themes stuck out when I first read the book.

One of the things that struck me most memorably is the spider’s web of personal loyalties, personal animosities, different tribes and history, and complexity of Afghan politics that Stewart walks through. Afghanistan is not coherent or cohered in the way that those of us living in long-settled western countries assume when thinking about countries. While there are regions with different ethnicities or dominant tribes, it doesn't even break down into simple tribal areas or regions divided by religion. The central mountain areas Stewart walked through are very isolated and have a long history and a complex web of rivalries, differing reactions to various central governments, and different connections. Stewart meets people who have never traveled more than a few miles from their village, and people who can't go as far as his next day's stop because they'd be killed by the people in the next village. It becomes clear over the course of his journey why creating a cohesive western-style country with unified national rule is far less likely and more difficult than is usually portrayed in the Western news media. The reader slowly begins to realise that this may not be what the Afghans themselves want, and some of the reasons why not.

A large part of that recent history is violent, and here is where Stewart's ability to describe and characterise the people he meets along the way shines. It is a tenet of both Islam and the local culture to give hospitality to travellers, which is the only thing that makes this sort of trip possible. Stewart is generally treated exceptionally well, particularly given the poverty of the people (meat is extremely rare, and most meals are bread at best), but violence and fighting fills the minds and experiences of most people he meets. He memorably observes at one point that one of his temporary companions describes the landscape in terms of violent events. Here, he shot four soldiers. There, two people were killed. Over there is where they ambushed a squad of Russians. It's striking how, after decades of fighting either for or against first the Russians and then the Taliban shapes and marks their mental map of the world. It's likely that few of the people Stewart meets are entirely truthful with him, but even that is an intriguing angle on what they care to lie about, what they think will impress him, and how the Afghan people he encounters display status or react to the unusual.

The second big theme that stuck out for me on a personal note was how Stewart respectfully weaves the wonder of history with the sad lament of the destructive loss heritage on his travels. In the book, Stewart followed roughly the same path as Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire, did in 1504 at roughly the same time of year. He quotes occasionally from the Baburama, Babur's autobiography, which adds a depth of history to the places Stewart passes through. The Minaret of Jam in the mountains of western Afghanistan is one of the (unfortunately rare) black and white pictures in the centre of this book, and Stewart describes the legendary Turquoise Mountain, the lost capital of a mountain kingdom destroyed by the son of Genghis Kahn in the 1220s, of which the minaret may be the last surviving recognisable remnant. He describes the former Buddhist monasteries at Bamyan in Hazarajat (the region of central Afghanistan populated by the Hazara) and the huge empty alcoves where giant statues of the Buddha had stood for sixteen centuries until destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. This book then is full of history of which is described with a discerning eye for necessary detail.

How Afghanistan's precious historical and cultural legacy was being destroyed even back in 2002 is heart breaking to read. I think many Westerners certainly know about how the Taliban dynamited the giant Bamiyan Buddha statues over a millennium old because they considered them "idols." Just as profound a loss is discovered by Stewart in his travels. There is a legendary lost city, the "Turquoise Mountain" of the pre-Moghul Ghorid Empire. Archeologists couldn't find it - but when passing through the area, Stewart had found villagers who had, and were looting artefacts with no care for the archeological context or the damage they were doing to the site, selling the priceless wares for the equivalent of a couple of dollars on the black market. This is what he tells us about his discussion with the villagers about the lost city:

"It was destroyed twice," Bushire added, "once by hailstones and once by Genghis."

"Three times," I said. You're destroying what remained."

They all laughed.

Even as I write this I can’t help but think this episode eerily echoes the madness gripping us in Britain, Europe, and the US (albeit for different reasons) in defacing and pulling down historical statues in wanton in acts of extreme ideological vandalism.

Overall I enjoyed the ‘peace’ of this book as there is a constant tone of a simple purpose. There are some moments along the way that are quite confronting and even frustrating, but so many that are warm and celebratory of the Afghan belief in hospitality.

Perhaps others will differ but I didn’t find too many irritating passages that wax-poetic on the evolution of the traveller. Stewart’s writing style is clinical; completely void of sentimentality, he never allows his own initial or personal meditations on these places overtake his observations, written with much hindsight. Whether being harassed by local soldiers or struggling through snowdrifts Stewart does not bridge a gap with the reader to really get a sense of who he his, as if his own story would detract from the crucial timing of his recordings of this landscape and its people.

His own biography is something out of John Buchan. The son of Scottish colonial civil servant who was born in Hong Kong and grew up in the Far East (and subsequently the second most senior official in the British secret intelligence) before being packed off back to England to Dragon School, Eton and onto Balliol, Oxford to study PPE. A short stint with the Black Watch regiment (as his father and uncle before him) before joining the British Foreign Office and work in some hot spots of the world, including a stint as deputy governor in the Coalition Provisional Authority in Iraq after 2003. He went on to work at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at Harvard before returning to the UK to successfully run as a Conservative MP in his native Scotland. Served as a minister in different ministries under Prime Minister Theresa May’s government and improbably came close to upsetting the coronation of Boris Johnson as the next leader of the Conservative party. He resigned from the party rather than be purged and made an unsuccessful bid to run as an independent candidate for London Mayor. He continues to writer and author travel books and front documentaries. He has a storied background but he wears it very lightly.

Of course there is a conceit to the book which in a sense all travel books of this kind that largely goes unquestioned. I don’t think it’s wrong to question a certain kind of entitlement that pervades these kind of books, no matter how much I enjoy reading them especially about countries you have traveled to and know a little bit about. Stewart after all embarks on a journey ‘planning’ to rely on the proverbial kindness of strangers because that is an Islamic cultural and religious value. Try planning a trip anywhere in Western Europe or the USA and Canada. I cannot imagine anyone walking across America, or England and Scotland for that matter, who would believe that he was entitled to expect food, shelter and assistance because he asked for it.

And he does it - as have countless travellers before and after him. Because Stewart succeeds in his journey, he is evidence of an astonishing degree of Afghan Muslim hospitality and generosity. As a back packer who has done it rough not just in Afghanistan but also neighbouring Central Asia as well as Pakistan, India, and China I can see why it might rub some up the wrong way. But I also think it’s not cultural or some sort of colonial arrogance on Stewart’s part. It’s hard to articulate but it’s really a kind of cultured sensitivity of people and lands you already are familiar with or know well from childhood.

Certainly for Rory Stewart - and myself - didn’t exclusively grow up in England and Scotland but in the Eastern post-colonial countries of the ex-British Empire that afforded a privileged childhood (privileged as in a real cultural engagement and immersion) that left a deep appreciation and respect for those countries cultures and traditions. I believe for the vast majority of Western back packers who take adventurous treks across these lands they do so partly out of genuine respect and understanding of different cultures.

For instance, the legacy of this book has been that Rory Stewart has spear headed a long term project called Turquoise Mountain. Alongside his partners, they have been re-creating the "downtown" river district in Kabul and restoring it to it's former glory. They have opened schools for people to re-learn the ancient arts of carving, weaving, architecture, etc. They have supported efforts to restoring city blocks that have been covered in a mountain of trash, and restoring homes where families have lived for centuries. And all for free. The Afghan have never been sure why someone would be doing this out of the goodness of their hearts, but that the poignant irony is that the goodness began with them through their hospitality of the stranger.

The kindness to strangers is a real thing in this part of the world. Kindness to strangers has it roots in fear that the strangers might be gods or their messengers alongside the pragmatic need that strangers in a strange land might need assistance. I sometimes wonder how is it we cannot show the same unabashed kindness to strangers to our homes?

However you slice it, you have to admire Stewart for his mostly un-aided walk across Afghanistan. It does take a certain kind of ballsiness to do it. He carried just his clothes and a sleeping bag (and money), trusting that the villagers along the way would put him up for the night and feed him. He got very sick (diarrhoea and dysentery), was at constant risk of freezing to death in the mountains, and had some very unpleasant encounters with Afghan soldiers in the last few days, after rejecting very strong advice not to walk through this section.

Strangely though nothing about this book is breathtaking of ‘Oriental exoticism’ beloved of Western imagination. Indeed nothing in this book is romanticised and nothing is placed on a pedestal. Stewart writes openly and honestly of all the people he met, those friendly, and those that would've preferred to rob him and leave him dead in a ditch. He's truthful and humorous, and I found myself walking alongside him, a sort of ghost following his rugged trail through mountains, valleys, and Buddhist monasteries.

Re-reading this book when I was doing my tour in Afghanistan with time to kill between missions, I wished George W. Bush and Tony Blair - and all the other Western leaders since these two - could have taken that walk with Stewart and learned the lessons he did. Stewart gives you a sense of the complexity and diversity of the culture and of Islam - and just how ludicrous and ignorant were the assumptions and goals imposed on the country by the invading Westerners. Indeed at the very end of his walk, Stewart reaches Kabul, the heart of the western intervention in Afghanistan and the place where all the political theorists and idealists came to try to shape the country. He describes the impact of seeing draft plans for a national government, which look ridiculous in the light of the country that he just traveled through.

It's a rare bit of political fire in the narrative that's all the more effective since it's one of the few bits of political commentary in the book. Indeed it’s all the more rich and relevant given its emergent commentary and background for the current war being fought there. Stewart necessarily tells only part of the story of Afghanistan, but he tells far more of the story than most will know prior to reading it. It should be mandatory reading for anyone making decisions about how to proceed in that region.

I would recommend anyone take a walk with Rory Stewart.

#books#reading#bookgasm#rory stewart#places in between#travel#afghanistan#trek#adventure#author#walking#treat your s(h)elf#personal#bio#army

38 notes

·

View notes