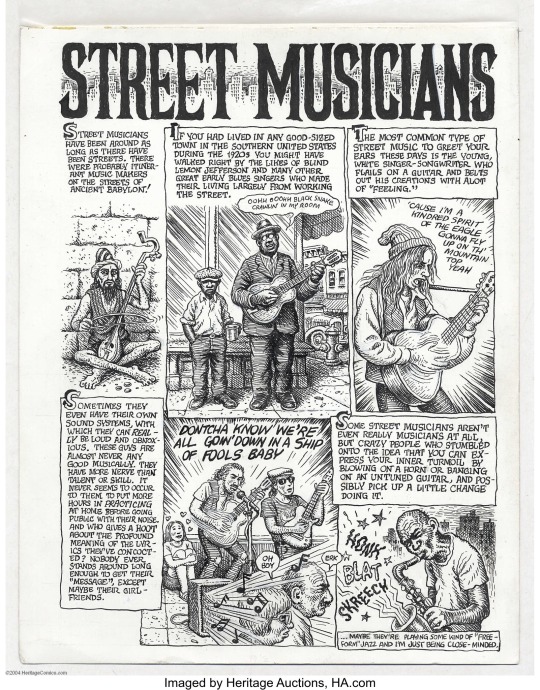

#street musicians

Text

Robert Crumb "Street Musicians" New Yorker Magazine Two Page Story Original Art (New Yorker, 1996) Source

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Musicians in #Washington_Square_Park, #Manhattan.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

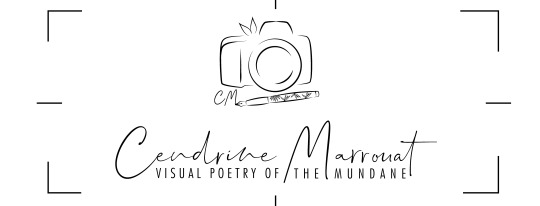

Serenata - Mexico City, 2014

#picofthenight#travel#mexico#original photographers#photographers on tumblr#street photography#interior photography#street musicians#streetphoto color#restaurant#photoofthenight

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Musicians in the streets, various years and cities.

#megan mcisaac#analog#film#photography#mamiya c330#portrait#music#musicians#street musicians#busking#los angeles#portland#artists on tumblr#black and white#medium format#art#original content#photo#made with kodak#kodak portra#samantha crain#san francisco#guitar#bass#banjo#cello#drums#street style

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

You guys need to know that the other day me and my friend were walking down the main street of my town and this busker saw my friend and was like, "I should play welcome to the black parade" and he started to play it... Only thing is he was playing a ukelele. So there's this dude and his son playing the black parade on a ukelele and a bass guitar. And you know how the song goes "to join the black parade" and then the guitar comes in really strong and it repeats that start part? Well out of fuck no where, this dude drops his ukelele PULLS OUT A FUCKING DOUBLE KAZOO THING and starts playing that for the guitar bit!!

Best day ever, thought you guys needed to know about the ukelele and kazoo black parade.

#mcr#wttbp#welcome to the black parade#the black parade#buskers#street musicians#my chemical romance#my chem

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wow! I met two godly talented guys playing their guitars in the shopping district of my city. I stopped and listened. I love people who do that. I left some money and a praise. I went shopping. When I had finished, they were still there. I stopped again and we chatted for half an hour, exchanged names and contact info.

That was a boost to my mood! Yay!

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Performers and People X Sofia Bulgaria

#sofia#europe#street musicians#busking#city#urban#cityscape#travel#nikon#candid#photographers on tumblr#photography#original#fine art

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poetry Lessons from John Ashbery's "Street Musicians"

John Ashbery has been deified by critics, but my sense is that he's divisive among young writers and poets. He's kind of a hallmark of obscure, academic white guy poetry that once ruled the literary world but is out of vogue (in many cases for a number of good reasons)—but on the other hand, he's incredibly prolific, has a tremendous vocabulary and has a silly, cerebral voice that is entirely his own.

I read his collection Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, which critics seem to consider his magnum opus as far as I can tell, and wasn't totally moved by it; there was interesting language and strange moments, but I found it too navel-gazey, too inward-facing and without enough footholds for readers. Unnecessarily difficult, in other words.

Even so, I picked up Houseboat Days, another collection of his, because I wanted to give him a fair shake anyway in the interest of closely reading good poets in order to improve my own writing.

With that out of the way, "Street Musicians," the first poem in the collection, actually impressed me. There are a few main things I want to take away and remember from it, which are as follows:

1. Titles, Context and "Directions" in a Poem

A common struggle for me when writing my own poems is choosing a title that speaks to what follows.

As I see it, there are different strategies you can take:

Self-consciously poetic title that speaks literally to the content (popular in older poetry, for e.g., Robert Herrick's "To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time" or Robert Frost's "The Road Not Taken")

Self-consciously poetic title that speaks figuratively to the content in varying degrees (on the more direct end of the spectrum, "Mean Free Path" by Ben Lerner comes to mind, alluding to a particle's path in physics vs. a reader's path through his elliptical writing style vs. a person's path in love and relationships and memory through their own life)

Plainspoken phrase with poetic affect, figuratively related to the poem either directly or indirectly (Elaine Kahn runs the gamut here, particularly in her collection Romance or The End—a more direct figurative example could be "You Dream of Candy Because You Want Yourself To," which does mention dreaming of candy in the poem but only as a detail, whereas a less direct one might be "Reality Steve," a reference to a blog of reality TV spoilers on a poem that doesn't seem very related to that at all; it might be a reference to The Bachelor or might not, since the poem does mention a person on TV with nice hair, or it could be a reference to a real lover in the poem the author addresses, though it might not—the title has a feel of an inside joke, though magically still works somehow)

Title that is the "first line" of the poem (Emily Dickinson has come to be known for this in retrospect, since her poems were seemingly untitled—"I felt a Funeral, in my Brain" for example)

And so on.

One thing you usually don't do is pick a non-poetic title that is strictly nominative and literal, which Ashbery does here (ie, it's about two street musicians... and it's called "Street Musicians"). Even so, it ends up working because the title still has an interesting relationship to the rest of the poem.

The main thing it depends on is the first line that follows it:

"One died, and the soul was wrenched out/ Of the other in life..."

The jump from the plain and nominative "Street Musicians" to "One died.../ Of the other..." does a lot of work with very little. Upon first reading the title, it could mean any number of street musicians; now immediately, it means only two.

Only two evokes a lot: a deep friendship, a rivalry, almost a romantic relationship. The fact that one of them has "died" in the first line also makes the poem feel very fast paced; in a way, "Street Musicians" is doing a ton of expository work and is setting up a timeline for the whole piece almost invisibly: as we see by the end of the first stanza, 90% of the story is already over when the poem starts, and the rest takes place in the twilight of that fact.

Suddenly, a boring title is actually pretty interesting—and the jump to "One died" is both tragic and kind of darkly funny (he's almost using the "jump" from title to first line as a narrative "line break," which is probably an underused technique).

Finally, as my one-time poetry teacher Elaine Kahn always stressed, you want a title that strikes the right balance between explaining and directing and providing another opening into the poem; in my own thinking, it's like thinking of the title as either a door (the only way in) or a window (one possible way) into the poem.

Direct and literal titles tend to run the risk of over-explaining or over-directing, but Ashbery elides that trap for a couple reasons: first, the title is so plainspoken and direct that it almost becomes too vague again, leaving room for interpretation; second, the poem itself actually doesn't offer many concrete clues (!) that the poem is a literal story about two street musicians other than the title (yes, there's details that lead that way, but without the title, it would be way too easy to interpret in countless other directions).

Suddenly the title is generous: it's just enough to get you started reading and interpreting, but not much more. Good start!

2. Abstract vs. Concrete, Open vs. Closed Language and "The Rules"

Some common writing rules are "show, don't tell," "use concrete language," "be specific," "avoid excess abstraction" and so on. They apply to almost all writing, but they have some special application in poetry.

Apart from its history as CIA propaganda, "show, don't tell" is a misunderstood rule and it breaks down when it comes to poetry (more accurate might be "balance showing and telling"), and the other three rules I mentioned basically follow this one rule.

The problem is in other forms of writing, "concrete language" means specific and descriptive language when painting scenes or pictures, but typically it leans towards a realist aesthetic (ie, use language that helps readers reproduce reality in their minds). In poetry, what is or isn't "concrete language" has a different sense—it means more juicy words and fewer filler words, more words that point to richer or multivariate meanings, more arrangements of words and lines that evoke than those that don't, and so on.

In essence, poetry already has a broad license to be abstract; it is encouraged in a way that it isn't in many other forms of writing. Even so, it's a question of where the abstraction comes from in poetry. Generally speaking, if it comes from the language you've chosen itself rather, it's a counter-productive kind of abstraction.

Again, thinking on Elaine Kahn's advice I've heard in the past (and her admission of being a fan of Ashbery, which surprised me), she says the key is to be "very concrete about abstract things," and that you can "get away" with abstraction if you can make it real somehow.

Ashbery is still too abstract in general for my taste, but I have to admit that he's kind of a master of this. Consider his description of the life and times of the surviving street musician:

Wrapped in an identity like a coat, sees on and on

The same corners, volumetrics, shadows

Under trees.

First of all, "wrapped in an identity like a coat" is almost disarming in how basic it is. The idea animating the metaphor is basic and well-understood: identity is illusory or "false" in some way, a rationalization. But "a coat"?

But then we get the description that follows: the seeing "on and on" evoking a dread of mortality, "corners" taking on the literal meaning of street corners and the figurative meanings of being "cornered"—and then the pivotal "volumetrics," which in my estimation, basically breaks "the rules."

What exactly is a "volumetric"? The definition is "relating to the measurement of volume," which is about as un-concrete and abstract as a noun can get (it's doubly breaking a rule because "volumetric" as an adjective might be evocative, but pluralizing it into a noun makes it seem like it would be bland again). So, why is it not bland here?

The concrete words Ashbery uses here around it are so concrete that they are almost mundane: the corners, the coat, the shadows, the tree. On the one level, we get the day-in, day-out existence of the unfulfilled street musician. Then, tying all of these things together, we get volumetrics.

Where it is, the word gives a whole new dimension (pun intended) to all the other daily observations of this would-be musician—and it gives a vivid inner voice to the musician at the same time. Suddenly, "corners" is evoking math formulas and trigonometry, "shadows" is evoking physics, vectors, light, heat.

Finally, the way the line breaks leaving "under trees" alone is interesting as well. Having "corners, volumetrics, shadows" together is important for these connotations to fly, but really what the musician is remembering or thinking of are the "shadows under trees," which is actually quite a specific image: he is thinking of the specific public places in parks and street corners where he can find shade on a hot day, and how the romance of that has drained with repetition. What was once a welcome respite, a secret performance space for those in-the-know has now been reduced merely to mathematics and logistics.

From Ashbery here, maybe we have a new rule: you can make your concrete language abstract, but it depends on context; you can do it if doing so will open more avenues and interpretations than it will close, which it does here.

From this and other examples, we can see that there are rules, and then there are rules. There are rules beneath the rules, and we ought not to take them (or the world, if we are to describe it evocatively) at face value.

3. Be Proportional with Vocabulary; Evoking Over Stating

Finally, Ashbery is thought of as an extremely verbose and dense poet (and sometimes he is), but "Street Musicians" shows a lot of restraint. There are a handful of moments that make you want to reach for the dictionary:

volumetrics

chattels

declamation

And none of these are really too much of a reach for any average reader. The moments that make you really sit up in your seat actually use quite plain language, combined or deployed in an arresting way. The moments that pop out for me are:

suburban airs/ and ways

beached/ glimpses

So I cradle this average violin

In November, with the spaces among the days/ more literal, the meat more visible on the bone"

The first two use line breaks to create puns and multiple meanings. The "average violin" is so crushing in what it evokes given what precedes it, but the language is entirely plain.

The last example is maybe the most instructive for me, because it is perhaps the most abstract in its concept and in its language while still working somehow. The first part of the line for me evokes a calendar, the sense of time passing (though why does November make the spaces clearer? shorter days? longer and more visible divisions of time?).

The second part evokes a kind of hunger, but almost inversely—a sense of literal "meat more visible on the bone" makes me think of when there won't be meat on the bones, of aging and eventually dying, of the hunger we have in our youth that wanes as we get older. Neither of these "images" are particularly concrete as we usually think of it, nor are they particularly related—but he orchestrates them so that they are here.

Finally, the only thing that turned me off in the poem:

"The plush leaves the chattels in barrels/

Of an obscure family being evicted

Into the way it was, and is.

For me, this is Ashbery Ashbery-ing as people usually accuse him, and I start to lose the thread. "An obscure family" doesn't do a lot for me," "into the way it was, and is" I understand but uses too many non-word words to make its point, the missing comma in the first line drives me insane, the double-s in "chattels in barrels" is frustrating for some reason and feels overly arcane.

But hey, nobody's perfect.

#john ashbery#poetry lesson#elaine kahn#street musicians#houseboat days#creative writing#poetry analysis

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Four mallets. 12/13/21

#Chicago#State Street#musicians#street musicians#vibes#bnw#black and white photography#original photography#street photography#canon photography#lensblr#pws#lux lit

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Early photography: Street Musicians - Eugène Atget

Early photography: Street Musicians - Eugène Atget

Sharing my favorite images from the early days of photography…

Title: Street Musicians

Location: France

Date: 1898-1899

Photographer: Eugène Atget (1857-1927)

Process: photography – silver (gold-toned)

French artist Eugène Atget started his career as an actor with a travelling group. A pioneer of documentary photography, he focused exclusively on the Old Paris—small trades, gardens, and the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Jose Case

Tony Robles talks with Jose Case, Main Street celebrity in Hendersonville, NC. In the video they talk about his bikes. In the audio file, Tony reads Jose a poem that he wrote about him, and interviews him WPVM Radio in Asheville, NC.

Hendersonville Celebrity

Tony Robles talks with Jose Case, Main Street celebrity in Hendersonville, NC.

Jose Case, Main Street, Hendersonville, NC

In the video they talk about his bikes. In the audio file, Tony reads Jose a poem that he wrote about him, and interviews him WPVM Radio in Asheville, NC.

Tony Robles reads a poem for Jose Case to Jose Case…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Night party at Xochimilco - Mexico City, 2014

#picofthenight#travel#mexico#original photographers#photographers on tumblr#street photography#night photography#fiesta#lakeside#streetphoto color#street musicians#photoofthenight

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hallelujah by Allie Sherlock & Fionn Whelan

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

ludinus: *has an immaculate plot crafted over the course of centuries, uniting disparate factions, puppeting heads of state and tearing apart the global status quo, frightening the gods themselves*

keyleth: *desperately throwing his lieutenant' daughters, archmages' vessels, calamity-era robots, titanlets, senior citizens, and her own Special Little Boy at his feet like caltrops* okay, now try to predict this.

101 notes

·

View notes

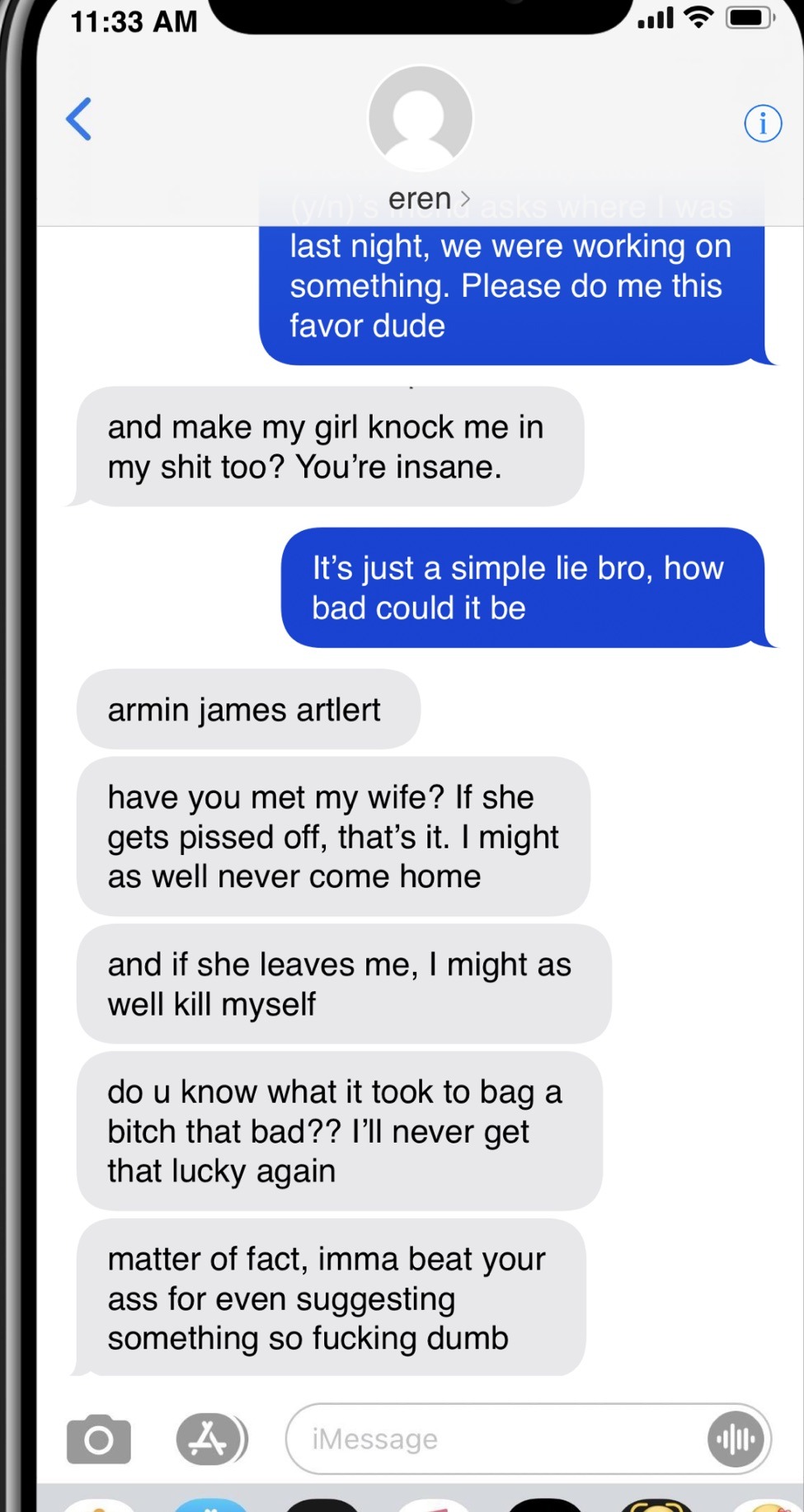

Text

I think that went over well

#eren said the streets are no place for him#he ain’t even got game like that#he just got lucky with (y/n) and he not gone fuck it up 😭#aot x black reader#cherry chats 🍒#black fem reader#musician x influencer au#musician eren#eren x black fem!reader#armin artlert#aot crack#black reader#attack on titan armin#eren jaeger aot#aot fake texts#aot anime

964 notes

·

View notes