#shabti

Text

Faience ushabti of Painedjem II. Artist unknown; ca. 1070-664 BCE (21st-25th Dynasty, Third Intermediate Period). Now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

#art#art history#ancient art#Egypt#Ancient Egypt#Egyptian art#Ancient Egyptian art#Egyptian religion#Ancient Egyptian religion#kemetic#sculpture#faience#ushabti#shabti#shawabty#hieroglyphics#Metropolitan Museum of Art

355 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shabti (Funerary Figurine) of Nebseni

Thebes, Egypt, New Kingdom, early Dynasty 18, about 1570 BCE

To assure themselves a comfortable afterlife, Egyptians stocked their tombs with at least one figurine called an ushabti, who acted as a servant in the afterlife. The message carved on each of the figurines explained that if the deceased is called on to do any work in the afterlife, the ushabti will respond with “Here I am” and will do the job. Some tombs had as many as one ushabti for every day of the year and another 36 overseers to keep order. All but the poorest citizens provided themselves with some kind of funerary furnishings. Products for burial and the labor to produce them made up a large industry in Egypt.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

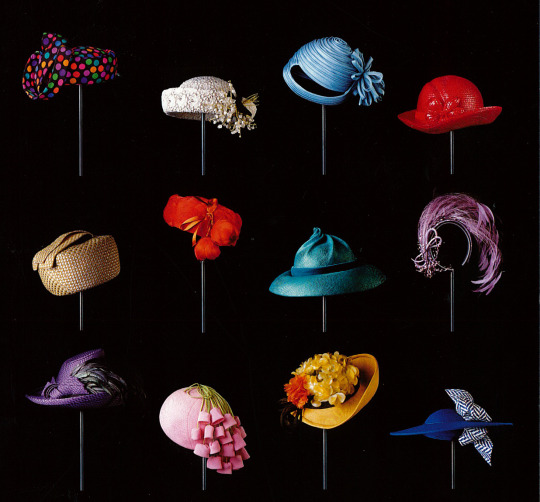

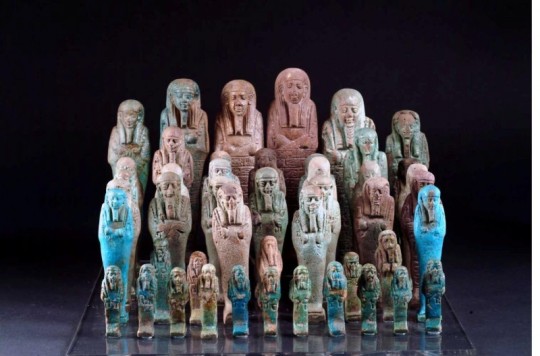

-> Ton of Typology <-

Typology of Presidential stamps. Smithsonian Postal Museum collections.

Typology of fossil shark teeth.

Typology of surf boards from the book by Richard Kenvin & exhibit at the Mingei Museum.

Typology of hats from the Kensington Palace Royal collection.

Australian spear points. britishmuseum collection.

Clovis point typology.

Typology of Southeast Asian shields. Thomas Murray gallery.

Typology of African shields. Thomas Murray Gallery.

Typology of pots. Mid-late 19th century. Native American, Acoma. Smithsonian collections.

Typology of Native American bandolier bags. milwaukeepublicmuseum collection.

Egyptian Shabti TYPOLOGY, Archaeological Museum of Zagreb.

Typology of snakes. Photography by Guido Mocafico.

#photography#typology#snakes#shields#bandolier bags#spear points#pottery#hats#stamps#surfboards#shabti#shark teeth

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prestige Class Spotlight 13: Aspis Agent

(art by LoranDeSore on DeviantArt)

Ah, the Aspis Consortium, an organization in the Lost Omens setting as insidious as they are greedy. With a mission statement that can be boiled down to “Make a Profit no Matter the Cost”, this organization is every bit of every bad thing about a worldview centered around money. Exploitation, theft, smuggling, slavery… If it can make them money, the Consortium will take advantage of it, all while maintaining the veil of goodwill through charitable works that are in the end infinitesimally tiny compared to the profit the organization makes exploiting the very people they’re supposedly caring for.

Remind you of anything in real life?

While the villainous and underhanded side of the Aspis Consortium can make them suitable antagonists for nearly any campaign, the most likely branch of the Consortium that members of the Pathfinder Society are likely to run into would be their agents. These explorers and plunderers seek out the same sort of ancient sites that the Society is interested in, but purely for the purpose of acquiring the relics within to either keep for personal power or sell to buyers without a thought or care about the impact they cause by doing so, be it disrupting sites held sacred by the locals or outright curses and magical traps on the relics they seek.

Which isn’t to say that the Aspis won’t have their field agents also participate in more domestic crimes as well, of course, but their training focuses on tomb robbing first and foremost.

Which is where this archetype comes into play. While primarily meant for villains, it can also be used for villainous protagonists in evil games, or even by former Aspis members who became (or are becoming), more heroic.

And outside the Lost Omens setting, this archetype could be quite useful for representing a character that is a professional temple delver, particularly one that often has to fight off other expeditions as well.

Delving into this training requires a whole suite of skills revolving around deceit and dungeon delving, as well as basic training with a whip and either keen senses honed around noticing traps or the ability to cast magic that reveals secret doors. The whip training in particular is due to the weapon being a signature combat style of the Aspis Consortium for it’s ability to cause nonlethal pain and control the battlefield.

True to their roguish talents, these agents learn the art of recognizing and avoiding traps if they don’t already have it, and improving upon their skills if they do.

Periodically as they grow in mastery, these agents pick up little tricks or improvements as they grow, drawing upon a short list.

Some stand fearlessly against larger beings and prove shockingly imposing against them, while others learn various advanced combat techniques ranging from setting up traps, using combat maneuvers, and even turning a whip into a deadly weapon. Others learn to ward their thoughts against intrusion so that foes only learn the thoughts they want them to know, while others with bardic training continue that to gain new and better performances. Some learn the art of concealing small objects and can even suppress their magic, which others still learn how to continue their bardic, inquisitor, or mesmerist training into spellcasting. Others learn techniques associated with rogues, while others learn enough magic to shrink an item down for easy carrying and concealment. Some who are also vigilantes can learn an additional technique for their social or vigilante identities.

They also learn how to conceal their aura so that magic that senses particular moralities fail to reveal anything. Later on, they can sense such attempts and even later provide a false aura in case their detection is sophisticated enough to sense all moral alignments.

Not content to merely bypass the traps they find, these tomb breakers learn how to rig both traps they’ve disabled or set up personally so that they can trigger them with a touch. After all, such ingenious mechanisms shouldn’t go to waste, whether they be used against rival delvers or particularly dull denizens. Later on, they can even trigger these traps from a distance with a deftly thrown rock or a nearly-invisible pullcord.

These agents also learn the art of striking for vulnerable points as a rogue would, or improving upon that skill.

Aspis agents know how to throw off the game of others, letting them demoralize or feint foes with clever words. Better yet, they can set such things up days in advance, calling back to a throwaway statement made days ago that sheds it in a new light and leaves a foe infuriated or reeling.

This prestige class certainly points the character in the direction of being the snarky rival archaeologist or treasure hunter, but the fact you can customize it to better suit several different base classes is a real boon. Not having true spellcasting increases is disappointing, forcing you to rely on the more roguish aspects of the class, and as such, your spellcasting choices will likely be built with that in mind, focusing more on buffs and utility than damage or debuffs. Still, this class can be a veritable bag of tricks, ranging from better casting to weaponizing and building portable traps, to performing all sorts of combat and utility tricks with a whip.

In the hands of an antagonist, this archetype can be quite effective for giving an adventure a villain or even recurring villain that isn’t inherent to the dungeon itself, which has the dual benefit of expanding the world and also give your villains and bosses somewhere to be that isn’t behind the final door. In the hands of a protagonist, however, it can a great way to have a morally dubious character in your game, or even a penitent one using their talents for good. Heck, aside from the lore there’s no reason this can’t be used with a swashbuckling hero that isn’t afraid to fight dirty to defeat evil.

Though most shabti, those beings created as surrogate souls to take the burden the souls of the wealthy after death, have a healthy respect for the dead and the world beyond due to how they are rescued form their fate by the psychopomps, not all feel this way. Some are bitter indeed for the cultures that invented the process of creating them to suffer in place of wicked rulers. Such is the case with Nayobi, who has become a professional tomb robber, not just for the riches therein, but to rob the dead she blames for her creation and suffering of their dignity.

For a month, the party has been racing against their rivals from tomb and ruin site trying to find the clues to the temple of the Horizon Eye, and they’ve both finally made it. However, the fight that erupts threatens to activate the Eye itself, a complex and powerful portal mechanism, and it’s guardian, a Lhaksharut inevitable!

The greedy often say that everyone has a price, that anyone will do anything if the reward is great enough. However, the counterargument is that there are lines that some people will not cross. Such was the case when the relic hunter Miriam Albrax learned what her employers planned to do with a dark relic she had procured, going into hiding as a hermit in one of the oldest forests in the world, watching over the relic with trap and forest ally alike.

#pathfinder#prestige class#aspis agent#shabti#lhaksharut#inevitable#Adventurer's Guide#Paths of Prestige

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

pottery barn was essentially a shabti. this thought is ever so slightly horrifying. please dont ask me why, it just is

#pottery barn#alex fierro#magnus chase#mcga#kane chronicles#shabti#pottery#magnus chase and the gods of asgard#riordanverse#help

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

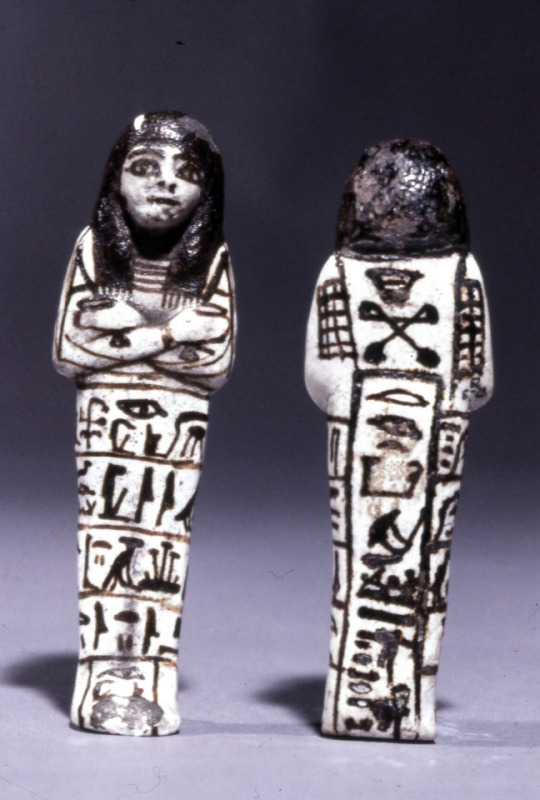

White glazed composition shabti of Anu. British Museum. EA30003

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Worker Shabti of Nauny, 1050BC, Egypt.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drawer full of ushabtiu! Typical New Kingdom dress.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Starting now, I will refer to any little guys or friendshaped creatures I collect as shabtis.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Individually inscribed with a spell that described their particular job or function the broad collars were worn while a person was living, after death and ritual embalming mummies were also buried wearing them. Details are now beginning to emerge about the Boy-King Tutankhamen as an Intersex individual.

Shabti dolls from ancient Egypt. Shabti dolls were the surrogate workers for the deceased in the afterlife.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Egyptian mud coffin containing a wooden ushabti. Artist unknown; ca. 1580-1479 BCE (17th-18th Dynasty, late Second Intermediate Period or early New Kingdom). Found at Thebes; now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

#art#art history#ancient art#Egypt#Ancient Egypt#Egyptian art#Ancient Egyptian art#Egyptian religion#Ancient Egyptian religion#kemetic#shabti#ushabti#shawabty#coffin#woodwork#carving#earthwork#Second Intermediate Period#New Kingdom#Egyptian Thebes#Metropolitan Museum of Art

237 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Is a Shabti, Anyway? (An Egyptologist Answers Your Burning Questions)

So, I wrote a novel called The Shabti (coming summer 2024!). In case you’re wondering what a shabti is—and why you might want to read a story about one—make yourself comfortable and let me fill you in. This might take a few minutes to explain.

The basics:

A shabti is a type of ancient Egyptian funerary figurine. If you’ve spent any time looking at Egyptian artifacts, you’ve probably seen one of these little guys. They usually* look like tiny mummies, with their legs fused together and their arms crossed over their chests. Sometimes they carry tools, such as hoes, adzes, and baskets. They can be made from a variety of materials, including stone, wood, pottery, faience, or even glass. For a typical example, check out this guy--a limestone shabti dating to the 18th Dynasty (ca. 1550-1295 BCE) that now resides in the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

There are many similar types of figurines (more on that below), but the shabti was specific to funerary contexts and served a particular purpose. It was intended to act as a stand-in for its owner that would step in if the deceased was called upon to do various types of labor in the afterlife.

While a lot of shabtis were inscribed only with the name and title(s) of their owners, others bore a spell explaining their function. This spell is usually identified by modern Egyptologists as Chapter 6 of the Book of the Dead, but it actually goes back to the earlier Coffin Texts of the First Intermediate Period and Middle Kingdom.

There are several variants of the Shabti Spell, and an even greater number of translations. But the gist is always the same: if the owner should be called upon to do various types of corvée labor in the realm of the dead (including things like tilling the fields and ferrying sand around), the shabti would step in to do the dirty work.

“I will do it,” promises the shabti. “Here I am!”

Some Egyptologists contend that in order to count as a true shabti, the figure in question must 1) be from a burial context and 2) be inscribed with at least a partial form of the Shabti Spell. But, like so many concepts in Egyptian religion, the shabti defies easy categorization. Shabtis have a lot in common, for example, with the votive statuettes inscribed with the names of their owners that pilgrims sometimes left as offerings at sacred sites. They may even share an affinity with the wax figurines described in several Egyptian magical texts and literary tales that could be animated and sent to do the bidding of the magicians who created them.

As representations of the dead in the form of Osiris, they could also serve a secondary purpose as a backup home for the Ka, or life essence, of their owner.

--

*There's actually a fair bit of variation in the appearance of shabtis. There was a brief fad for putting them in the “dress of life” during the Ramesside period (ca. 1295-1075 BCE), which means they are dressed in the equivalent of white tie formalwear instead of being bundled up like a mummy. Some of the earlier ones just look like, well, sticks. These might have a square-ish approximation of a face and maybe a blocky unifoot, like some kind of Minecraft mummy. You can see examples of both types, along with the more common mummiform shabti, here.

A brief history of the shabti:

The shabti represents one stage in the long, complex evolution of funerary statuary in ancient Egypt. It is the result of a melding together of several earlier traditions in Egyptian funerary art and religion.

One of the earliest types of statuary from Egyptian tombs is the Ka statue, a formal representation of the deceased person that was housed in the tomb chapel. Some Ka statues depicted single individuals, while others depicted couples or family groups (consisting of spouses, parents and children, or siblings, for example). These statues served as interfaces between the dead person (or people) represented in the statue and the living people who maintained their funerary cult. They were also meant to serve as a sort of backup body, a place where the person’s life-force (Ka) could go to rest and receive offerings.*

The ancient Egyptians liked to feed and entertain their dead. They envisioned an afterlife that was not too different from life-life, where dead people required sustenance and enjoyed the same kinds of luxuries and diversions that they did when they were alive. It also wasn’t without its dangers and inconveniences—hence the need for various forms of magical protection and assistance for the tomb owner.

In the later Old Kingdom, the serdab (“statue chamber”) that housed the Ka statue was also home to an assortment of other figures, commonly called “serving statuettes.” These statues are less formal and more naturalistic than the Ka statues. They show people engaged in various kinds of work, entertainment, and, sometimes, play. Serving statuettes can represent men and women, adults and children, and they depict a range of activities from slaughtering animals, grinding grain, or brewing beer to playing music, wrestling, and dancing.

These statuettes seem to have been intended as a sort of support staff for the dead. In the event that the supply of offerings from the living dried up, the serving statues were there to act as backup—much like the Ka statue itself served as a replacement home for the soul if anything should happen to the body. These representations of people preparing food and engaging in various other acts of service had the magical potentiality of becoming “real” in the realm of the dead.

Interestingly, not all of these statues represented nameless, generic servants. Some of them were inscribed with the names of the tomb owner’s children or other relatives. Perhaps this was both a way of honoring a deceased family member and a ticket to ride along with the tomb owner’s funerary cult. (Want to read about a couple examples of these named serving statues? Check out the writeups on pages 108-109 of this special exhibit catalog, written by yours truly.)

The serving statuettes were phased out after the end of the Old Kingdom in favor of elaborate wooden tomb models depicting whole tableaux of people at work. These models portray everything from crews manning ships to weavers toiling in textile workshops. Sometimes the tomb owner is depicted as well, carrying out the kinds of duties they would have done in life (such as overseeing cattle counts).

In the Middle Kingdom we also see the development of “estate figures,” an evolution of a type of two-dimensional imagery common in Old Kingdom tomb chapels. These are personified representations of the estates that supported the tomb owner’s funerary cult, and they were intended to keep providing for the soul of the deceased for eternity. They take the form of offering bearers carrying food, drink, and luxury goods for the dead.

But around the same time as these tomb models, another type of funerary statuette appeared on the scene. The earliest proto-shabtis were simple wax or clay figurines which eventually developed into miniature mummies, sometimes complete with wrappings and/or tiny coffins. While the earliest examples usually weren’t inscribed with much more than a name and titles, some of them carried an abbreviated version of the longer Shabti Spell.

By the New Kingdom, the more elaborate tomb models and serving statuettes had fallen out of favor altogether, to be replaced by the more streamlined and standardized shabti figurines.

While larger, more formal statues of the tomb owner were still a standard feature of most tomb chapels, the shabtis also served to combine the functions of the earlier Ka statues and the serving statuettes. The shabti both represented the deceased and served as a replacement or stand-in that was bound to do its owner's bidding; the master and servant combined into a single figure.

Up until the end of the New Kingdom, most burials contained only a handful of shabtis. These earlier examples tended to be individualized and highly variable in their appearance. As time went on, the number increased, and some people were buried with hundreds of mass-produced shabtis—a whole army of tiny henchpeople.

During the later New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period, overseer shabtis were produced to manage the more generic worker shabtis. These super-shabtis were depicted carrying symbols of authority, such as whips and staves. A wealthy Third Intermediate Period burial might have 365 standard shabtis--one for each day of the year--with 36 overseer shabtis to manage them all. The overseer type eventually fell out of fashion with the return to more classical forms in the Late Period, but the tradition of mass-producing shabtis by the hundreds continued.

Around the same time, the spelling of the word “shabti” changed to reflect their evolving nature. More on that in a minute.

--

*Another weird possible spinoff of the Ka statue and/or precursor to the shabti is the so-called “reserve head,” a type of object that was in vogue very briefly, during the 4th Dynasty. What were these for? Well, like so many things in Egyptology, all we have are educated guesses. But the most popular theory is that they were literally spare heads. You know, in case something happened to the dead person’s real one.

What does the word “shabti” mean?

Hahaha! Wouldn’t we all like to know.

Okay, so in the early Third Intermediate Period, the spelling of the word changed from SAbty (shabti) to wSbty (ushebti). The explanation of the latter spelling is clear. It’s a backformation based on a folk etymology from the word “wesheb,” which means “to answer.” The ushebti is an “answerer,” an entity that responds when called upon to do work. This change may reflect a loss of the shabti’s earlier status as a representation of the deceased as well as a stand-in. The sole purpose of the ushebti was to do labor on behalf of its owner. These figures were simple worker-drones for the dead.

But what about the earlier form of the word? Well, speculations run the gamut from shabti being a form of the word SAb (meaning “food” or “meal”) to a Semitic loanword meaning “stick” or even a form of SAwAb (meaning “persea tree”). There might also be a connection with a word attested in Late Egyptian, Sby (meaning “to replace”). Any one of these meanings could make sense if you squint enough, but we may never know with certainty which one is correct.

What’s the deal with the shabti in your book?

Well, obviously I’m hoping you’ll read it and find out. For now, suffice it to say that it’s a particularly troublesome shabti. So troublesome, in fact, that the mild-mannered professor who curates the museum in which it now resides is starting to suspect that its original owner isn’t quite finished with it yet . . .

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me while listening to Coptic chanting in Moon Knight:

I KNOW THAT WORD!!!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deep Shaman (Shaman Archetype)

(art by LuigiL on DeviantArt)

The power of the ocean is not one to be trifled with, and shamans in particular are well-aware of the power of water and its spirits. However, the traditional spirits of waves tend to grant powers more useful for those that dwell on land primarily, such as the ability to breathe underwater. While this is useful for such surface-dwellers, it is not so much for the aquatic races.

Deep shamans, as they are known, instead ask for a modified version of the pact with the waves, gaining abilities that more suit their aquatic nature. Additionally, many of their abilities that are not replaced are instead enhanced underwater.

These are the shamans that call upon the power of deep water, where the light does not touch. Indeed, many also revere the goddess Besmara, honoring her former aspect as a spirit of the sea, before her worship transformed her into the goddess of piracy and sea monsters.

While technically terrestrial shamans can make similar pacts, they have more difficulty, since their spirit-granted powers no longer grant them the ability to survive or swim at speed in the depths, requiring they use traditional magic to supplement those losses of abilities.

Naturally, their focus on the depths means that these shamans universally form a bond with a spirit of the waves. What’s more, they also must take an aquatic animal as their spirit familiar, which does mean they need special considerations when carrying the creature on land, such as an aquarium ball.

Many of the hexes these shamans use are modified by their connection to the depths, such as weakening the strength of those harmed by the chill, and entangling foes in water with their damaging water hexes. Additionally, the crashing wave hex, which normally enhances water spells, also applies to their spirit powers and hexes that utilize water.

They also gain two new hexes, which replace the hexes that hide them in mist or let them peer through murky water. Instead, they gain the power to control the buoyancy of themselves and others, letting them swim with ease and making others rise or sink at their whim. The other hex lets them regain the ability to breath and swim underwater since they do not get it naturally, but it also lets them resist water pressure much more easily as well.

Other shamans of the waves can push foes away with a touch, blasting them forcefully with water. For a deep shaman, however, the injuries are much more severe than the nonlethal blast, and much more forceful. What’s more, instead of quenching flame with their weapons, they use water to increase the mass and force of their weapon, striking harder.

Meanwhile, their mastery of water no longer automatically gives them swimming speed and the ability to breathe underwater. However, they do gain the ability to sense vibrations in the water, and their blast of freezing cold water becomes stronger and farther-reaching while in the water.

Rather than turn into an elemental, these shamans instead turn into a brine dragon, the epitome of elemental water in dragon form, a form they can maintain for hours, or indefinitely if they remain below the surface of the water.

This is one of the more fun ways that an archetype modifies another character option choice, as it makes the waves spirit, which one would think would be very useful for an aquatic character, into something that does not provide redundant or useless abilities to such sea-dwelling characters. It even has an option so that landbound races can still use it. As for its utility, it provides much the same as the standard waves spirit, but makes them much more potent in their preferred turf. As a final note, I recommend also supplementing this archetype with the aquarium ball item from Familiar Folio, as well as the expanded underwater rules from Aquatic Adventures, the same book this archetype comes from.

It would be erroneous to assume that these shamans are of a higher rank or class than other shamans of the wave. It is merely that they express their powers in different ways. However, the spirits of water that they bond with might have different personalities compared to others, perhaps being less relatable or knowable compared to those that see the sun, assuming there is any difference at all.

The frozen seas of the world of Akkus are patrolled by all sorts of deadly arctic predators, including the insectile ursikkas. However, beneath its surface lies aquatic folk of various races that rarely ever venture above the ice except to hunt. These cultures are often led or advised by mystics and shamans with a particularly impressive command of the water around them.

Perhaps derived from a wealthy sailor or pirate captain, the shabti Tuvi’tib has always been fascinated by the sea, and had an affinity for its depths and the creatures that live there. However, even being an otherworldly facsimile, they still need air. To that end, they sought out a spirit of the water to bond with.

Seeking answers about a curious artifact, the party must brave the depths to find a powerful merfolk shaman who might have the answers they are looking for. However, the shaman is in self-imposed exile, and may react violently to the intrusion.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unbound Boxes Limping Gods: Disconnected Stories: Issue # 594: The Guild Master’s Genie

After receiving her second consecutive orders from Guild Master Merek, a furious future Alexand transported herself from the sanctuary of her bedroom in Los Angeles, to her sister Heyem’s apartment in Cairo, ready to fight with Heyem about the relentlessness and frequency of her missions.

Future Alexand’s back story, set in Egypt, Civil Earth (1277 FD)

View On WordPress

#Alexand Merek#art#Cairo#Egypt#Eric Mehmed#feminist fiction#future#graphic story#Heyem Merek#Identical twins#Inajda Rekaya#Katherine De Somme#science fiction#shabti#speculative fiction#Unbound Boxes Limping Gods#Zero Merevija

0 notes

Text

Ushabti of Pahemnetjer

New Kingdom 19th Dynasty

Faience, ink

Egyptian

------------------------------------------

This shabti is from the 19th dynasty, time of Ramesses II. It is made for the "master craftsman" (which refers to the High Priest of Ptah at Memphis), specifically Pahemnetjer (referred to as the "Priest"). This priest is known from other sources, providing the date, and probably would have been buried at Saqqara.

The problem with this ushabti is its source. University of Michigan excavators found it in a street context in the Graeco-Roman town of Karanis, over 100 miles (160 km) away from its original burial place at Saqqara.

Located at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology

0 notes