#prophet adam story

Text

youtube

#islamic stories#prophet stories#stories of the prophets#islamic#prophet stories islam#quran stories#islamic videos#emotional islamic lectures#islam#islamic stories in urdu#islam stories#islamic video#Islamic channel launch#english islamic stories#prophet is islam#quran story#quran#prophet adam story#prophet adam#english story#prophet#one islam#koran#muslims#allah#Alzarrar#inspiring stories#good deeds#dhul hijjah#ramadhan

0 notes

Text

youtube

#islamic stories#prophet stories#stories of the prophets#islamic#prophet stories islam#quran stories#islamic videos#emotional islamic lectures#islam#islamic stories in urdu#islam stories#islamic video#Islamic channel launch#english islamic stories#prophet is islam#quran story#quran#prophet adam story#prophet adam#english story#prophet#one islam#koran#muslims#allah#Alzarrar#inspiring stories#good deeds#dhul hijjah#ramadhan

0 notes

Note

Wait I'm a little misplaced about MP AU

so there are more parasites? since according to what I read there is Thacher, Eve and Adam.

But how did Thacher and Evelin get the parasite? because according to what I read in the fic it's because Gabriel gave it to Adam

The Parasite is. constantly changing and adapting. even from just coming out of the back, to eventually being able to come out of the chest, to even the mouth. Things like that.

Near the end of this au's main storyline, Thatcher gets injured by the parasite, and it's blood makes it into his bloodstream, making him the second victim of it.

Eve was a similar case, probably infected by Thatcher's already mutated version of the parasite, and. it just mutated further and now she's. that-

#asks are neat#mandela prophet#Now I'm gonna make it clear. Adam is STILL the main focus of the au.#If anything. Thatcher and Eve's parasites are like. post main story stuff.#Adam's parasite is also the ONLY prophet. the other parasites don't really give people MAD or listen to Gabriel.#So Adam. still has the most important parasite.#Prophet Adam (tmc)#Parasite thatcher#Parasite Evelin

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I swear Christianity (and islam!! and islam!!!!!! PLEASE LOOK AT ISLAM!!!) has so many themes that can be esxplored in art and literature but they choose the same Noah, Moses, David, and Jesus stroylines (or the good ol modern christians puritan plot of atheist bad christ good) that Im so ready to snap back with catholic blasphemy.

#'oh but you can't draw anything of the prophets in islam!' you ever heard of refrences?? allegories??#the quoran also has a lot of added information from the other prophets of judaism and christianity.#in the same way new indie works are starting to reference agnosticism or the book of enoch others could also reference prophets by#using them as inspirations for characters in other stories.#side rant but Iblis seems more of a cool character to explore than lucifer. mainly because The Devil#in chritianity is vague and also a metaphor for all encompassing evil#whereas Iblis can be seen as Evil but still have more than just a textbook defintion of Evil.#One ource states he asked directly to disway adam from Allah.#other sources state than he does have free will. as any other jinn. to be neutral or good or evil. but mainly chooses to turn people#away from Allah.#He is also more likely to be in hell whereas The Satan from the bible is more just trhown into a lake of fire. his second death.#and God knows what the heck any of the Apocalypse is supposed to mean#so yeah Iblis. and other jinns. I need more media (mainly western media) to focus on these little guys.#omg and yeah#THEY ARENT EVEN FALLEN ANGELS so the whole theology of whenever or not angels can revel is just#thrown into the lake of fire

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hello,

I apologize in advance if you've already answered something like this but my cursory look didn't show anything. I am looking for a game system that has an emphasis on the feeling of a wild west movie while still retaining general fantasy elements from DND. The wild spaces are slowly becoming tamed, increasing technological/magical advancement are pushing disparate communities together, and of course cocky assholes with guns (or a magical equivalent).

Thanks in advance

Theme: Wild West Fantasy

Hello friend, you might want to check out my Fantasy Westerns rec post, to see if anything there fits what you’re looking for. I especially recommend checking out the rec for We Deal In Lead and Clink. For the rest of this post, I try to span a very broad range, so I don't expect everything to stick - but perhaps one or two do!

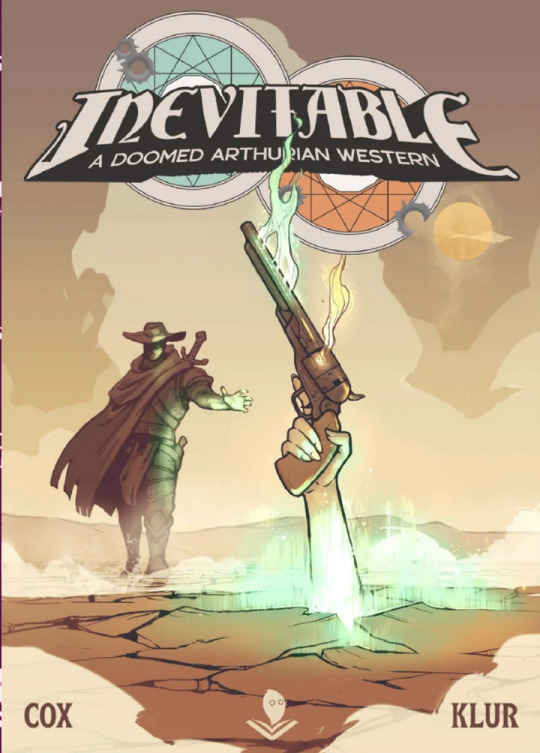

Inevitable, by Soul Muppet Publishing.

Knights and wizards have defended the Kingdom of Myth for centuries. These lands have known peace and prosperity, but soon the kingdom shall be destroyed. The Prophets have declared that your city shall burn and Myth will fall. All those who follow your King shall die. It is INEVITABLE.

But you shall defy fate. Myth will not end while you bear arms.

You will fail, but as long as there are still stories, they will sing of you!

Inevitable is a Arthurian Western roleplaying game for 2-6 players and a GM, where your party of disastrously sad cowboy knights fail to stop the apocalypse. This 284 page book contains all the rules, character creation and the setting for your campaign, thoroughly and evocatively detailing The Barren, the lands surrounding the Kingdom of Myth.

This game might be way you’re looking for: it describes itself as a fantasy kingdom, with western aesthetics. There are wizards, prophets, and rune-carved revolvers. Your reputation in the kingdom is important; it determines how well you can face challenges, and roll pools of d6 on a table of staggered success. If you want a taste before you buy, there’s a Quickstart with some evocative set pieces, a quick overview of the rules, and a quick adventure to run through with a list of pre-generated characters.

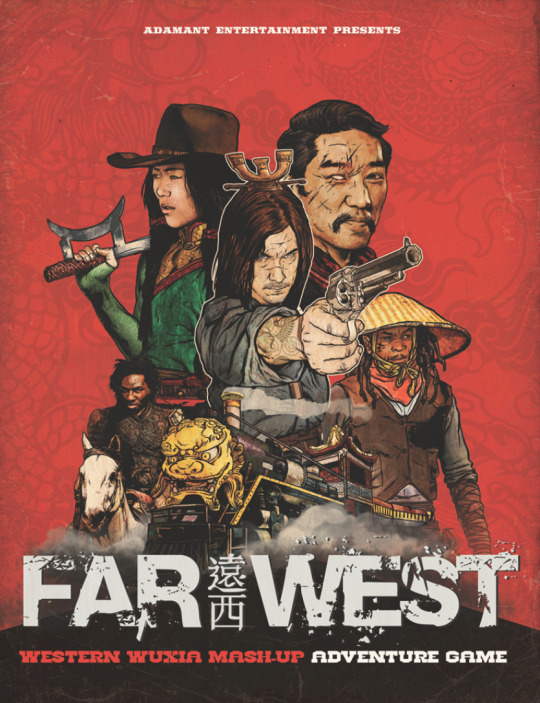

Far West, by Adamant Entertainment.

Imagine a fantasy setting that shatters the tropes of Medieval Europe.

Imagine a collision of Spaghetti Westerns and Chinese Wuxia by way of Steampunk.

Imagine a world where gunslingers and kung fu masters face off against Steam Barons and the August Throne.

Imagine fantastic machines powered by the furies comprising the fabric of the universe.

Imagine an endless frontier where wandering heroes fight for righteous causes while secret societies engage in shadow wars.

Imagine…

This game is a combination of Wild Western tropes and Wuxia fantasy. Your characters are wandering heroes, defending the small and helpless against the strong and powerful. I look at this game and I think of movies like The Magnificent Seven. Mechanically, it’s its own system, but it draws heavily from Fate, using positive and negative aspects to boost rolls and spark complications.This game relies on some tropes that require entire table buy-in: I’m not sure how many assumptions the game makes about the cultures it takes inspiration from.

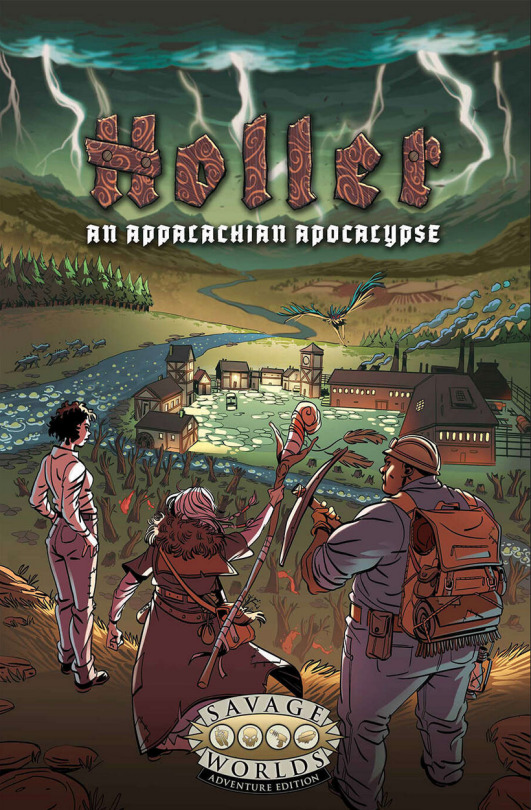

Holler: An Appalachian Apocalypse (Savage Worlds), by Pinnacle Entertainment.

In Holler, the mysterious “Big Boys” own the mines, mills, and logging operations. They rule over every aspect of their workers’ lives—subjecting them to extraordinary dangers on the job and crushing oppression outside of it. The Big Boys have transformed the land of the Holler—rivers bubble with strange chemicals, strip-mined mountains crumble into valleys, and the air is choked with a toxic fog known as the Blight. The flora and fauna of the Holler grow more monstrous by the day. Demons of every description lurk in the forests. Mutant cryptids haunt villages with their strange cries and appetites. Vengeful haints leer from abandoned shacks and lonely cliffs. No one is coming to save the people of Holler.

The goal of the resistance is to build a coalition, to bring together diverse factions—humble workers, roustabouts, mountain men, dirt track racers, cultists, and even strange creatures of myth and legend to raze the works of the Big Boys and drive them from the Holler forever. Holler draws deeply on Appalachian history, mythic folklore, and culture to create a dark fantasy world of apocalypse and vengeance.

This sounds a little more grim and gritty, with cryptids, toxic fog and demons lurking in the forest. It uses the Savage Worlds system, so you’ll have to pick up the codebook to play with it, but the setting is very very fleshed out. This is a little less Wild West and a little more Appalachia, and the setting is a bit more on the horror side than most of the other games on this list, but there’s certainly a lot of wildness out there for you to fight!

TROUPE, by TheOriginalCockatrice.

A game about travel, discovery, and outsiderness, a combination of the best of Old-School and Story Games. Complete with 6 Jobs, including the Ghelf, the Hedge, and the Ogra, and includes a system for holistically coming up with a character from scratch.

The designer describes this game as an exploration of the road; the odd and unknown of the wild, what it means to belong, and what it means to be on the outside. You’re not heroes - you’re entertainers, jokers, healers and bards. There isn’t exactly magic, but there is myth and legend. This is a great game for folks who want plenty of challenges that exist outside of combat. Each character playbook comes with a balance of mechanical elements and descriptive options, and you’ll be rolling 2d6 plus your stat in order to determine success.

I’m not sure how much of a Western this is, but the designer actually hacked this game for BXLLET, a game about gunslingers in the apocalypse, in the zine Bxllet Clip, so it might be worth checking out!

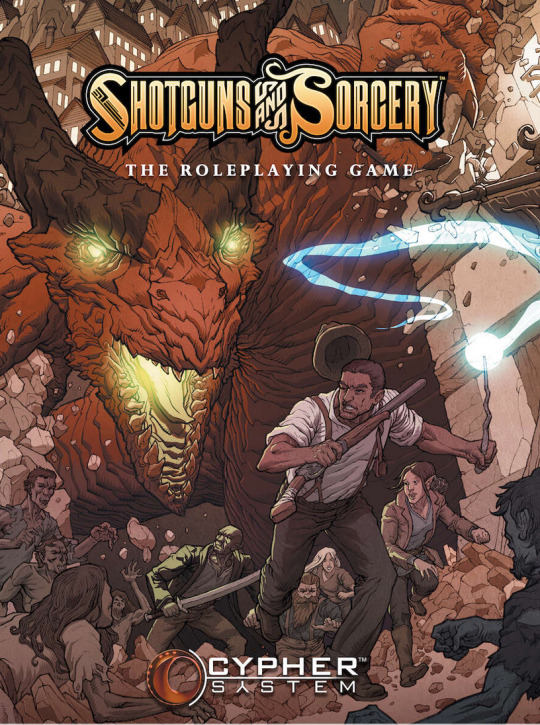

Shotguns & Sorcery, by Full Moon Enterprises.

Welcome to Dragon City, a grim, gritty metropolis ruled over by the Dragon Emperor, with legions of zombies scratching at the city walls by night.

Whether in the streets of Goblintown or the prestigious halls of the Academy of Arcane Apprenticeship, people try to scrape by, make a living, and survive from one day to the next. You, however, are looking for something more than simple survival. And in this city, if you don’t make your own adventure, another adventure is sure to find you.

Shotguns & Sorcery is a fantasy noir game complete with Dragon City Intrigues, roving hoards of undead, and unexplored mountains rife with magical creatures. You’ll see magical staffs alongside light pistols, bows alongside submachine guns, and greatswords alongside canteens, playing cards and a camp stove. The game uses the Cypher System, with an additional character option alongside the three-part character sentence: your race. This includes the signature hafling, elf, dwarf etc.

Games I’ve Recommended in the Past

Knights of the Road, by bordercholly.

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can any Hazbin hotel fans come here? I have genuine questions about the setting of the show.

1: Why Adam is even the leader of these demon slayer angels? Why him being the first man makes him qualified for this kind of postion?

2: Talking of Adam, how is he the first person to go to heaven? No matter which testament you base the show on it should've been Abel the first murdered person to be the first human in heaven (also if they never show Cain and Abel it'd be a huge missed potential)

3: Does god exist? Helluva boss makes it seem like he does but in Hazbin hotel the show implies high ranking angels created the universe.

4: Where are the rest of the biblical figures? No other prophets, no saints (except that horrible rendition of Saint Peter) no mention of archangels considering being the first man made Adam a celebrity and head of the exorcist angels they should be even more popular than him.

4: Talking of prophets biblical imagery is everywhere, Saint Peter is here so Jesus also must exist in this universe, yet show never mentions him once, I think the story is missing a huge potential by not making any use of these religious figures.

5: Vaggie says she never knew angelic weapons could hurt angels, and well... Her back story is literally her being harmed by an angelic weapon.

6: Power scaling is so weird, so this entire time Lucifer could take on Adam but didn't do anything about it? Did he just not give a shit about these exterminations?

7: So for the entire history of humanity not even one person has risen from hell to heaven? These angels are probably billions of years old, if they didn't make the rules who the fuck did?

There's just so many holes in this setting it drives me crazy.

#hazbin hotel#vivziepop#lucifer#charlie morningstar#Adam#vaggie#I dunno#Christianity#I guess?#someone please answer these I'm genuinely trying to be in good faith but the holes are way too big

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pictured are selections from the digital version of mothy's novel, Original Sin Story: Crime. All art is done by Ichika.

The picture at the top is the cover of the novel, featuring Adam and Eve, and is the same as the paperback copy of the book. Below that is a black title page with gears that says "Original Sin Story". The kanji in the white circle below and upside-down at the top is the kanji for crime / sin.

Next, is the table of contents, and can be translated as follows:

Prologue: Prophet Merry-Go-Round

Chapter 1: Queen of the Glass

Chapter 2: Project "Ma" - Eve

Chapter 3: Project "Ma" - Adam

Chapter 4: Project "Ma" - Seth

Chapter 5: Escape of Salmhofer the Witch

Chapter 6: moonlit bear <E>

Chapter 7: moonlit bear <A>

Epilogue: And, Towards Punishment

Afterward, and commentary

The two screenshots after that are pictures. The first one features Adam Moonlit standing in front of Gammon Loop Octopus, while the second shows Kiril and Meta together.

At the end are two small excerpts of text. The first is from the prologue, and are referencing the section of Queen of the Glass where Alice asks how to make human bodies for God. The second has a line from the song "Project 'Ma'", with Eve wishing for a wedding in Held's Forest.

This novel is available for digital purchase on Booth. After payment, a PDF will be offered for download.

Purchase the digital version from Booth here.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#quran#prophet adam story#english story#one islam#koran#abu bakr#first khalifah#caliphate#islamic story#caliph#prophet muhammad story#prophet muhammad death#prophet muhammad (saw)#history#islamic cartoons#prophet stories for kids#1st caliph#iqracartoon#prophet muhammad (s)#first caliph#prophet story#islamic history#prophet muhammad#yaqeen institute#muslim#victory#prophet stories muhammad#prophet's death#mecca#islam

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

#quran#prophet adam story#english story#one islam#koran#abu bakr#first khalifah#caliphate#islamic story#caliph#prophet muhammad story#prophet muhammad death#prophet muhammad (saw)#history#islamic cartoons#prophet stories for kids#1st caliph#iqracartoon#prophet muhammad (s)#first caliph#prophet story#islamic history#prophet muhammad#yaqeen institute#muslim#victory#prophet stories muhammad#prophet's death#mecca#islam

0 notes

Text

Lilith

recently I saw a post where someone was claiming that since Lilith is traditionally in Jewish mythology a demon associated with death of children, death in childbirth, etc that its wrong to do modern feminist re-imaginings of her, as if it's like a white cultural appropriation that doesn't support Jewish interpretation

And this felt off to me but since I haven't really been a religious Jew (I'm a cultural/ethnic Jew) I didn't comment.

But the thing is: Jewish feminists have recognized for YEARS the subversive potential of re-interpreting Lilith. There is even a feminist Jewish magazine named after her.

As a general rule, while its important to be careful of modern appropriation and interpretation of other religions, its also important that especially with Jewish religion and culture that people don't fall for the idea that there is this monoculture or single set of interpretations, or that the ability to recognize subversive or feminist or suspect aspects of a story are like uniquely modern/white/western traits.

Jews have been interpreting and reinterpreting our own stories for as long as we've had them and plenty of rabbis talk about reinterpreting Lilith through a feminist and sex-positive lens.

Another very interesting aspect of the Lilith story is that Lilith originates/was codified in the medieval text the Alphabet of Ben Sirah, and seems to have been created to explain why there are 2 creation 'stories' listed in Genesis; Genesis 1:27 describes god creating humans in male and female forms, and Genesis 2 describes god again creating eve from adam's rib (or side) because he was lonely. (Again I'm mostly reporting from what Rabbis like Danya Ruttenberg and others have said).

Lilith is one of those figures who is not accepted as a real part of the mythology by all Jews, and her presence in the actual Torah and writings of the prophets is mostly by 'implication' or interpretation. There is a lilith mentioned in Isaiah in a more generic way, but this lilith appears to be treated more as a generic demon if i recall.

Again, there are plenty of modern scholarship that also criticizes the use of Lilith as a feminist icon, and there are good reasons for both positions! But I do want to push back against the idea that somehow Jews are not a part of our own modern midrash.

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you know who is going to be in MP?

The aus set in the canon universe. But a different timeline. So pretty much everyone in canon tmc is in it.

Adam is of course the main character in this au. He and Sarah. Other than that I’m unsure, as. The MP was supposed to be a one off character design but. Fixation.

#asks are neat#Mandela prophet#should I start tagging this as au?#also. thinking of having this story change right after the events of volume 2#like Adam talks to six and leaves Cesar’s house only to encounter Gabriel#who’s basically like. hey stop listening to that smelly tv guy. you should totally follow me#and cursed him to be the prophet?#and then the au goes from there#thinking of it. I don’t think it’ll be as complex as the alt au of course#but still.

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why do you think the biblical god always chose men. Why is it that we get such a small handful of women who really had a story in the bible. Is it favouritism? To whom anyway, isn't it safer not to be picked by god? Men dropping left and right while the women watch, silent, unnamed, anonymous. Unseen? Forgotten?

Anyway, thoughts?

i don't see this god always choosing men. i see prophetesses chosen by god. i see prophetesses feared by him: they have power that rivals his. they do resurrections, they trap souls. i see judges raised by god. i see this god sitting with women as they fall victim to bans, as they benefit from bans. god sits with queens, with mothers. god has a womb, is a womb. i am thinking of ruth, naomi, deborah, jael, rachel and leah, not-adam/eve, bathsheba. on and on, this god is and has a matrix. women, in the hebrew bible, have phalli, have prophetic dreams. women do sign-acts, speak god's word.

it is true that in this ancient world, the category of woman was fraught, and sexual difference itself a leaky signifier. patrilineality prevailed and violence was done unto and across the feminine body. but this god does not watch idly as it happens. this god won't let us colonize the text with our frameworks, even and including those of sex. this god is dis-membered just as the non-con of judges 19 is. this god loses her children to sacrifice. this god is a sacrifice—a young female one. but 'female' isn't right here, is it, because this god creates in (or, indeed, gives-birth through) a rubric of difference that elides two-sexes. this god's breasts pang after a still-birth. this god is barren and lamenting it. this god is dying in the wilderness with her sisters, with you

#ask#the ancient world did not have a two sex system we cannot read sexism into it#we also should read the hb very carefully bc there is so much femininity here

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aurora Borealis (1865), oil on canvas by Frederic Edwin Church

A masterlist of my completed HDM fics (mostly Masriel):

The Day Before (M, 12 100 words)

A Nutcracker-coded Chaos Family Christmas story

The Space Between (E, 12 300 words)

The only thing more destructive than Asriel and Marisa going up against each other is them collaborating. (The Magisterium has a new research station in the North and Asriel is curious.)

There is a Sea (M, 79 100 words)

Marisa centric. Marisa's childhood backstory

Memento (E, 28 000 words)

How Asriel lost Lyra / why Marisa started wearing a locket for Lyra (Plus lots of Masriel being dysfunctional soulmates)

Son of the Dawn (M, 63 100 words)

Asriel centric. Asriel's backstory, from his childhood to the airship crash that took his brother's life, with prophetic dreams/a thread of destiny throughout. (He was always destined to change the world, just not in any way he would've imagined.)

In Winter, in Oxford (T, 47 600 words)

How Asriel and Marisa met

Unholy (E, 24 800 words)

Masriel Affair Era. Lyra is conceived in the North

A Nativity Scene in Late Summer (M, 7 900 words)

Baby Lyra's arrival, from Asriel's POV

Clemency (M, 11 400 words)

Why Marisa spared Thorold's life at the end of S1, from Thorold's POV, with an appearance by baby Lyra

Your Fortress (E, 17 100 words)

Based on book canon: Asriel and Marisa's missing scenes in the Adamant Tower

In-progress fics and any new fics I write will be added as they're completed

#hdm fanfic#masriel#asriel x lyra#lyra x marisa#asriel belacqua#marisa coulter#masriel fic#chaos family#my fic#hdm fanfiction#his dark materials#🌌🌌🌌

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Allah mentions the story of Prophet Adam ‘alayhis-salaam and Iblis in several places in the Qur’an. They both fell due to their mistakes; the fall of one of them was temporary, but the other fell to a much different and greater degree, and continues to fall until the end of time. From this, we learn two reasons on how a person can turn away from guidance: Desire, and Kibr (Arrogance).

In the case of the temporary slip of Prophet Adam, it was due to his simple desire. If we let our desires get the best of us, for example if we put dunya as our main focus in life, we will miss out on Allah’s guidance.

But in the case of Iblis, it was his kibr. And when a person suffers the disease of kibr, he will find it much harder to return and repent to Allah. For Iblis, it was his destructive characteristic of arrogance that has caused him to permanently turn away from guidance.

🌟 Sufyan ibn 'Uyaynah rahimahullah said: ❛He whose sin is due to desires [al-shahwah], then have hope for him; and he whose sin is due to pride [al-kibr], then fear for him. For verily Adam sinned due to desires, and he was forgiven; and Iblis sinned due to pride, and he was cursed.❜ [Siyar A'lam al-Nubalaa' 8/462 | Translated by Tulayhah Blog]

🌟 And Rasulullah salla Allahu ‘alayhi wa sallam said: ❛No one, who has an atom's weight of arrogance in his heart, will enter Jannah.❜ A man asked: ❛But a man likes to have nice clothes and nice shoes.❜ Rasulullah ﷺ said: ❛Verily, Allah is beautiful and He loves beauty. Arrogance is to disregard the Truth, and to look down upon people.❜ [Sahih Muslim 91a]

We can’t even see an atom with our eyes, yet this much weight of arrogance is extremely heavy in the Sight of our Rabb. May Allah protect us from both kibr and following our evil desires, and enter us into Jannah.

Your sister in Deen,

Aida Msr ©

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't know for sure how many of these are actual parallels and which I just made up but

Here's a list of all biblical references I remember in Trigun

Story-wise:

Vash & Knives acquiring "forbidden knowledge" and bringing the literal downfall of humanity (Adam & Eve eating the forbidden fruit of knowledge and getting thrown out of Eden)

The city preying on travellers being destroyed, only a girl who had been out of town left alive. (The City of Sodom; God sends two angels to carry out his judgement on the town of sin. As all the men in town rally around to kill the angels, only Lot is left alive as he leaves the town.)

Knives getting all the dependent plants that are largely being abused by humans in an attempt to bring them all to a new promised land, bringing out revenge on those that oppose them (Moses bringing the oppressed israelites out of Egypt, "and the Lord said: But I know that the king of Egypt will not let you go unless a mighty hand compels him. So I will stretch out my hand and strike the Egyptians with all the wonders that I will perform among them.")

More literal:

The independents being referred to as "angels" and having wings (the most typical depiction of biblical angels)

The plants being created by humans (God creating humans in his own image)

The plants virgin births (The Virgin Mary giving birth to Jesus)

Wolfwood carrying a giant cross (Jesus carrying his own death sentence)

The Eye of Michael (Archangel Michael, the right hand of God and leader of God's people in the endtime battle between heaven and hell)

The Seven Cities, two of which had Vash angel-out on them (The Five Cities of the plains - Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, Zeboim, and Bela - Sodom & Gomorrah famously destroyed by two angels for their sins)

12 Gung Ho Guns (12 Disciples of Jesus.)

The independent plants created as a bridge between humanity and plants, created by plants but raised by a human mother (Jesus as half divine/half human)

Vash's unhuman levels of forgiveness (Jeezy boy taking on the sins of mankind through his suffering)

Elendira fighting with nails (Jesus being nailed to the cross rather than tied which was custom)

Vash promising Meryl that he will be back walking into what looks like a suicide mission (Jesus telling his followers that he will come back from death)

Knives ship where he brings all the saved plants being called "The Ark" (Noah building an ark (large boat) and housing a pair of every animal on it as God sends a flood over the earth, drowning all the sinners, only the people and animals on the ark being left alive)

Vaah & Wolfwood arguing about the righteousness of taking a life, Wolfwood's death at the orphanage and Vash burying him (Job 6:26-27 "Do ye imagine to reprove words, and the speeches of one that is desperate, which are as wind? (Do you reprimand those that are desperate for their views and call their words meaningless?) Yea, ye overwhelm the fatherless, and ye dig a pit for your friend.")

Meryl & Milly as reporters following Vash (The Prophets and their job of spreading the word of Jesus/the lord)

The appletree (the symbol of Eden)

Quotes that appears inspired by the bible:

Vash saying "we should never have been born" (Job, God's specialest little boy, curses his birth as misery befalls him)

Elendira comparing humanity to maggots ( "The stars are not pure in his eyes, how much less a mortal, who is but a maggot? A human being, which is a worm!)

#Vashs whole looks and Esau's description being he is ''red & hairy'' lmao#trigun#vash the stampede#millions knives#elendira the crimsonnail#nicholas d. wolfwood#biblical references#trigun maximum#trigun meta

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

The name Frantz Fanon has become inseparable from the history of decolonization. It is almost impossible to speak of anti-colonial violence or the failings of postcolonial elites without referring to the figure who inspired generations of activists to revolt against colonialism. Since the publication of his seminal work, The Wretched of the Earth, in 1961, Fanon has been idealized by generations of activists in the global south and beyond. For them, the Black Martinican and Frenchman who devoted himself to Algerian independence is the fearless and uncompromising prophet of revolution.

The subtitle of Adam Shatz’s new biography, The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon, suggests that his life was not so simple. Shatz, the U.S. editor for the London Review of Books, is an expert guide through the thicket of Fanon-lore that has emerged since his death in 1961, and his book offers a compelling account of Fanon’s transformation from a medical student into a global icon of anti-colonial revolution.

But The Rebel’s Clinic tells another, more tragic story, too: the tale of a young Black man from the French colonies who never really belonged anywhere, no matter how closely he identified with a nation or cause. Despite his deep attachment to Algeria, he could never really embody the Algerian revolution, as hagiographic accounts of his life have suggested. His life and body of work were too complicated to be branded in this way. Although Fanon was a remarkable thinker, he could be conflicted and even contradictory, and simplifying him only simplifies the difficult and often fraught work that must go into anti-colonial movements.

The first words a young Fanon learned to spell were “Je suis français.” As a child in Fort-de-France, the capital of the French colony of Martinique, in the 1920s and ’30s, he enjoyed the privileges of a typical bourgeois family: servants, piano lessons, and a weekend home outside the city. This was not uncommon for Antillean évolués, or assimilated colonial subjects whose European education let them rise up the colonial hierarchy. Like many of their class, the Fanons looked down on the “nègres” from France’s African colonies, who they believed weren’t really French.

Fanon’s parents identified so deeply with the French Republic that they behaved “more French than the French,” Shatz writes. As for Fanon, whose father was largely absent, Shatz recounts that he would collect several adoptive fathers in his short life but the “symbolic father represented by France” was by far the most important. Fanon strongly believed in the universal values of the republic: liberty, equality, and fraternity.

It was not until Fanon joined the Free French Forces in World War II that his faith in European civilization was shaken. In the army, he witnessed the French generals’ racism; the rigid separation between white, Antillean, and African soldiers; and the horrors of trench warfare. “Yet the incident that seems to have hurt him most,” Shatz writes, “was returning to Toulon [in southern France], during the celebrations marking the liberation of France, and finding that no Frenchwoman was willing to share a dance with him.” Though Fanon had risked his life for France, it would never truly accept him, and he never recovered from the rejection he experienced when he finally arrived in the métropole.

After the war, he studied medicine in Lyon, a city Shatz describes as “notorious for its suspicion of outsiders,” and eventually practiced as a psychiatrist there. His first book, Black Skin, White Masks (1952), grew out of a period of intense frustration and suffering. He dictated the book to his fiancée, Josie, in a burst of anger and creativity. (Fanon never typed anything himself.) It was his reckoning with a city, and a country, that he was beginning to despise—an attempt to make sense of what he described as the “lived experience” of Black men in white society. The desire to “become” white, he concluded, alienated racialized people from themselves, and assimilation constrained their freedom. Today, the book is celebrated as a foundational text in the study of Blackness and of alienation. But at the time, few readers appreciated or understood Fanon’s methodology—a synthesis of psychiatry, psychoanalysis, memoir, and social theory.

As Fanon’s awareness of the appalling situation of Algerians in France grew, he gradually lost “interest in the psychological dilemmas of middle-class people of color like himself,” Shatz writes. His psychiatric study of the “North African syndrome”—a mysterious illness that plagued France’s Algerian population—was a turning point. Algerians kept going to French doctors saying they were in pain but without clear physical symptoms. Fanon discovered that their pain couldn’t simply be dismissed as “imaginary,” as most French doctors had done. The racism of French society was making Algerians sick, he believed, and their ailments could only be treated by addressing this uncomfortable truth. For Fanon, mental illness could never be divorced from social conditions. He considered himself an activist and, Shatz writes, “approached psychiatry as if it were an extension of politics by other means.”

The Rebel’s Clinic is at its best when Shatz describes Fanon’s early efforts to develop an anti-colonial psychiatry. In 1953, Fanon was hired as the director of the French-run Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in Algeria. His time there opened his eyes to the brutality of colonialism, and under his guidance, the hospital transformed into a center for experiments in social therapy. Initially, the Algerian Muslim patients regarded Fanon with suspicion. To them, his cultural attitudes represented those of France. But, as Shatz writes, Fanon had a plan:

Working with a team of Muslim nurses, he created a café maure, a traditional Moorish café where men drink coffee and play cards, and later an “Oriental salon” for the hospital’s small group of female Muslim patients. Muslim musicians and storytellers came to perform; Muslim festivals were celebrated; and, for the first time in the hospital’s history, the mufti of Blida paid a visit during the breaking of the Ramadan fast.

French colonialism dehumanized Algerians by destroying their culture. By reminding them of their culture, Fanon hoped to help his patients assert a collective identity, which would give them the confidence to undergo a process of “disalienation” and fight back against the French.

At Blida, the Algerian nurses shared Fanon’s radical politics, and together, they secretly treated fighters with the National Liberation Front (FLN), which sought to overthrow French colonial rule. The hospital staff formed a militant health care collective that challenged coercive approaches to psychiatry. For them, Blida wasn’t an isolated institution where patients were locked away to recover; rather, their work in the hospital was part of the struggle waged outside its grounds. Fanon and his staff even introduced day hospitalization so patients could maintain ties to their social environment.

In Shatz’s view, Fanon’s dedication to health care was perhaps his most important contribution to the Algerian revolution. (He never engaged in active combat during the war.) Providing health care remained a priority for the FLN throughout the years of fighting.

After the French discovered Fanon was secretly an FLN member, he fled to Tunis, Tunisia’s capital, where the FLN’s provisional government would be based, and took up a new role in the movement: He still treated patients traumatized by war but also worked as a propagandist championing the FLN’s armed struggle. Although his democratic vision of a people-led revolution clashed with the FLN’s authoritarianism, he dutifully justified its policies to an international audience. As Shatz points out, the strategic use of the phrase “we Algerians” in his articles for El Moudjahid, the FLN’s French-language newspaper, was a way to prove how closely he identified with the Algerian cause. His writing and speeches during this period helped create the myth of Fanon as a leader of the revolution.

The Rebel’s Clinic pushes back against this mythologizing. Fanon’s identification with Algeria grew as the war intensified, but he was an outsider: He spoke neither Arabic nor Berber, was not Muslim, and had come to Algeria as a representative of the colonial government. And while FLN leaders respected Fanon’s medical work, they never quite trusted him. Even as they presented him as a spokesperson of the movement to international audiences, Fanon had little influence over its direction and politics. When he learned that his close friend, key FLN figure Abane Ramdane, had been assassinated by another FLN faction, he was devastated. But he never questioned the leadership’s decision and refused to break ranks. Fanon had become a captive of the revolution he’d hoped to ignite.

Shatz notes that A Dying Colonialism, Fanon’s first book about Algeria, “reads like a record of revolutionary hopes soon to be dashed.” Written in Tunis in 1959, the book gives an idealized account of Algerian liberation, pieced together from his memories of the war’s early stages. But the social changes he praised—the emancipation of Algerian women (the subject of his famous essay “Algeria Unveiled”), the dissolution of classes, and the turn toward secularism—were never realized in practice.

Fanon never really understood his adopted home, especially when it came to religion. His belief in the revolution was so absolute that he failed to consider how the conservative, Islamist forces in the FLN might shape its outcome. Like Ramdane, Fanon argued for an independent Algeria that would welcome everyone who renounced their colonial privilege. He believed that the roles of “settler” and “native” ascribed by colonialism were never fixed. After independence, he hoped, Algerians would finally be able to “discover the man behind the colonizer,” as sympathetic Europeans too became equal citizens in a secular Algeria. But, as Shatz argues, these ideals clashed with the FLN leadership’s more narrowly Arab-Islamic vision of post-independence Algeria. Even the people Fanon had hoped would lead the revolution—Algeria’s poor peasants—embraced the FLN’s social conservatism.

To avoid conflict over its social policies, the provisional government promoted secular leftists to diplomatic positions in West Africa. In 1960, Fanon was stationed in Accra, and he soon came to share the Pan-Africanist views of Ghana’s president, Kwame Nkrumah, who insisted that all Africans would be united by their common struggle against colonialism. Fanon was convinced that Algeria would lead the rest of the continent toward liberation. But ironically, his influence in the FLN waned as he became more famous, and he “would have little success in ‘Algerianizing’ the strategies of African liberation struggles,” Shatz writes.

Fanon wanted to convince African anti-colonial movements to engage in guerrilla warfare, as the FLN had done. But their leaders often chose peaceful organizing or negotiations as the preferred route to independence. Fanon rightly feared that this approach to decolonization would enable former colonial powers to “recolonize” Africa through favorable arrangements with compliant leaders. His evisceration of Africa’s post-independence bourgeoisie in The Wretched of the Earth was inspired by his work as a diplomat.

Fanon was not always prophetic about the future of African politics. As Shatz points out, he underestimated the impact of the Cold War on Africa, insisting that it was merely “a distraction from the larger drama of decolonization and the rise of the Third World.” Two of Fanon’s closest friends and political allies in sub-Saharan Africa—soon-to-be Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba and the Cameroonian communist Félix-Roland Moumié—would be assassinated in the early 1960s because of their leftist politics. (Fanon had himself survived an attempt on his life in Rome in 1959.) Another close friend, the Angolan Holden Roberto, turned out to be a CIA asset and was secretly working to undermine Lumumba, whom he described as a communist “puppet.”

The process of decolonization, then, was not only a struggle between anti-colonial movements and colonial powers but part of the global struggle among competing ideologies. As much as he tried to ignore it, the Cold War found Fanon, too. Following an FLN expedition to Mali to assess the possibility of a weapons corridor to southern Algeria, Fanon fell ill and was diagnosed with leukemia. In a show of “friendship” to the FLN, the CIA agreed to bring Fanon to the United States—a place he’d previously dismissed as “the country of lynchers”—for treatment. Fanon died in a hospital in Maryland in December 1961. A few months later, Algeria achieved its independence.

Today, various activist causes, from Black Lives Matter to the Palestinian solidarity movement, have again embraced Fanon as a leading thinker. But his work has also found favor with scholars in disciplines such as psychiatry, psychoanalysis, and philosophy. In her recent interviews with Shatz, Fanon’s former secretary, Marie-Jeanne Manuellan, mentioned that she didn’t like him “to be chopped into little pieces.” Manuellan insisted that Fanon’s “pamphlets” were “texts written in the service of a political movement, not works of philosophical reflection,” Shatz writes.

Yet this is precisely what the canonization of Fanon has too often done. Fanon’s psychiatric and philosophical writings merit renewed attention. But this attention should not come at the cost of gaining a fuller understanding of how Fanon’s anti-colonial thought builds on his earlier psychiatric studies or of his fraught and often conflicted role in the revolution. The Rebel’s Clinic is careful not to reduce Fanon’s life and thought to a single interpretation. Fanon’s advocacy of anti-colonial violence cannot be separated from his belief in a revolutionary humanism. For him, violence was a necessary step in the struggle—a kind of “shock therapy” that would restore confidence to the colonized mind. But he also understood that the traumas of the war would not disappear at independence.

Shatz does suggest that one aspect of Fanon’s work is most relevant for our world today. Fanon knew very well that the struggle for decolonization was only a first step toward the birth of a new humanity, which would allow both colonizer and colonized to finally be free. He never described exactly what the social revolution he so strongly believed in would look like, but he was certain that the poor and oppressed of the “Third World,” not liberals or the European working classes, would lead the way. This anti-colonial and universalist Fanon is, perhaps, the one Shatz would like us to remember most.

12 notes

·

View notes