#postcolonial decolonial literature

Text

this semester's reads (spring '24)

#bookblr#book lover#diverse reads#diverse representation#my photos#my post#black representation#octavia butler#borderlands#latinx reads#english class#postcolonial decolonial literature#borders race and literature#classic reads#classic books#latine reads#english major#womens gender and sexuality studies#mexican american studies#english studies#books#books and reading#books and literature#university student#university studyblr

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

hiiii this is new blog from old user

im interested in: poetry, art, literature, postcolonialism, decolonialism, critical race studies, disability studies, gender studies, diaspora studies, marxist feminism, anarchism, and cats

#poetry#art#literature#postcolonialism#decolonialism#critical race studies#disability studies#gender studies#diaspora studies#marxist feminism#anarchism#communism#socialism#leftism#feminism

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

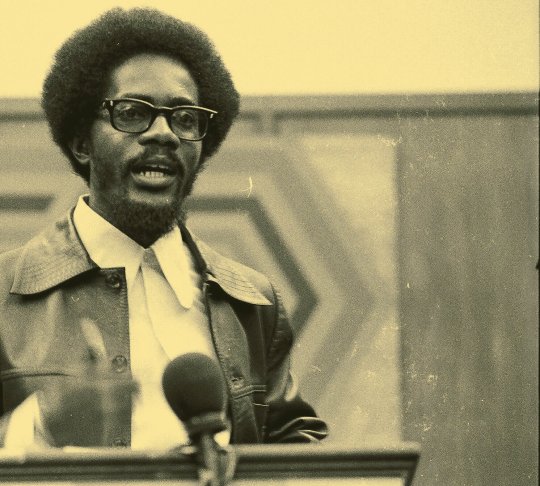

Decolonial Marxism - Walter Rodney

Hello friends!

Today's recommendation continues the focus on revolutionary thinking from important figures in the Global South with a compendium of wonderful essays that are incredibly relevant today: "Decolonial Marxism" by Walter Rodney.

Walter Rodney was am inimitable historian, educator, and political activist who forwarded Pan-Africanist and Marxist thinking and action since the 1960's. His groundbreaking historiography on Guyana and research in Tanzania produced works like "How Europe Underdeveloped Africa," his magnum opus that forwarded a rigorous analysis on the ways colonialism ransacked the African continent as a piece of postcolonial literature. He also became actively involved in the Black Power movement, fostering alliances with prominent figures like Angela Davis and Kwame Ture. His tireless efforts to unite oppressed peoples around the globe earned him admiration and support from many, alongside angering institutions like the US-backed Guyanese government which were likely sources of his assassination in 1980.

"Decolonial Marxism" delves into the intersection between Marxism and the postcolonial struggles faced by former colonies around the world, challenging the view that these theories are ultimately Eurocentric. In this collection of posthumous essays, Rodney evaluates how Marxism can be harnessed to address the structural issues perpetuated by colonialism and foster decolonization, while also criticizing actually Eurocentric views present on this revolutionary tradition.

Incredible strengths of this view lie in Rodney's analysis of how class society is intrinsically connected to the legacy of slavery and colonialism alongside a study of African history on its own terms as a Marxist, alongside his thinking of what a Pan-Africanist Marxist revolutionary struggle can look like. He takes inspiration from Tanzania's Ujamaa to flesh some of these investigations out, which I highly recommend.

"Decolonial Marxism" goes beyond theory; it provides historical examples and case studies that demonstrate the practical implications of anti-colonial Marxist thought, which makes it a must read in my book.

#book blog#book review#bookblr#decolonisation#marxism#anti colonialism#walter rodney#pan africanism#global south

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

doing a phd in literature is already enough to ostracize yourself from your liberal/conservative extended family but also specializing in political ecology/environmental humanities where marxism and postcolonial or decolonial perspectives are sort of the de facto lodestones is ensuring that you will never speak about your research with them ever again lol

#teddy.txt#i’ll never forget when i was talking to some of them and my cousin was doing his master’s as i did mine#but his was in polisci and they told me his was way more prestigious and more impressive and that i was ensuring i didn’t have a future#and now look who’s the most educated person in the whole extended family 😭

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

University of North Texas-Denton Assistant Professorship in English

Deadline:

Unstated; posted on HigherEdJobs.com 10/19

Length/Track:

Tenure track

Description:

Seeking an “Assistant Professor with a specialty in Decolonial, Postcolonial, or NAIS Literature, open period.”

URL:

https://jobs.untsystem.edu/postings/77696

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Mark John David, THU-11

for Module 5.1 Post/Decolonial Critique | IG Post

"Just like humanity, art is ever-changing. Throughout history, different forms have existed. However, it is still difficult to set an agreed definition of what constitutes art to everybody. Building an objective definition of art is futile. The rise of Artificial Intelligence led the way to diminish the gatekeeping of art and to make the production of art accessible to everyone even to those without

the right tools. Dialogues arise, however, regarding whether products of such technology are ethical.

As the world progresses, humanity also changes. The big question now is do we recognize and embrace these changes to be part of our values? Or do we reject these changes and revert to our ‘real’ heritage?"

I was assigned to week 12’s IG post with the topic Decolonial Approaches: Black Aesthetics under Module 5: Alternative Art Histories. In this topic, we discussed the lived experiences of people of color under oppression through some selected literature. The concept of diasporic experiences emerges as a

point of discourse in art history wherein the lens of postcolonial critique is instrumental.

For this week’s IG post, the goal is to make a manifesto for the future of art. To make a manifesto is to make a stand for a pressing issue in the context of art. Decolonizing art and its surrounding institutions remain a challenge. The influences of power and the identity of colonialists continue to shape the world today. In a similar concept that reaps through the fruits of the natives (in this case artists), recent artificial technologies are on the rise that could probably be

bound to shape the definition of art since the invention of photography. There have been AI developments that aim to automate with just a simple prompt and tweak the production of digital paintings, movies, scripts, etc.

Numerous discourses are also heard on whether products of AI are indeed art. For now, my activity will not argue for either side. Instead, I believe that there is a need to acknowledge that ‘AI art’ or ‘AI-produced images’ are a thing now. Unless strong policies are put in place that would gatekeep the production of such works, AI is already happening with the goal of revolutionizing production. It might even soon replace traditional artistry if the human touch is lost in the elements of art appreciation as AI imagery offers convenience, with almost no cost or skill need. In this discourse, however, one thing is certain. Most of these AI models built their frameworks using existing artworks without considering the ethics of such. Some AI image generators even blatantly aim to copy the art style of certain artists and pass it off as “appreciating the author’s work.” Kim (2022) called a recent issue after the passing of Korean Illustrator Kim Jung Gi as Orientalism in a postcolonial setting. (1)

(1) Leo Kim (December 9, 2022). Korean Illustrator Kim Jung Gi’s ‘Resurrection’ via AI Image Generator Is Orientalism in New Clothing.

https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/kim-jung-gi-death-stable-diffusion-artificial-intelligence-1234649787/

0 notes

Audio

Thanks for making your way up the great big hill from Leo’s to Lauinger Library, a trip harrowing for many Georgetown students and a common example of Georgetown’s deeply inaccessible campus. You’re now at the Brutalist doorstep of arguably the physical pinnacle of Georgetown’s role as a knowledge producing and reproducing institution, with its 1.7 million tomes. It’s a good opportunity to interrogate Georgetown’s epistemological traditions and philosophies, and what the library itself represents in this order.

For one, per Cusicanqui, Georgetown is often partaking in a type of academic ventriloquism—and a type of hierarchization that affords certain “academic heroes” a kind of epistemological ontology that lacks integrity, makes invisible Indigenous knowledge, and decontextualizes information. It’s hard to enter any classroom where critique is done where scholars like Foucault and Mignolo are not referenced, let alone not cited. Philosophy classrooms reproduce and venerate the logics of Kant and Locke and Rousseau. In fact, the library has whole shelves dedicated to each of these men and their theories, prizing them as epistemological grandfathers and unimpeachable field titans. Yet what gets lost is the roots of these work—many of these epistemological traditions are grounded in a deep sense of Eurocentrism, are undergirded by orientalism, and partake in the same eliminative logics that Dotson warns against. About Mignolo specifically, writing from an Aymara perspective, Cusicanqui problematizes the so-called “foundational” decolonialism theorist for creating an empire within an empire by adopting the language of postcolonial studies without shifting the power relations within universities.

From Bolivia, she has watched Mignolo and other postcolonial scholars turn the North American university into a practitioner of this sort of ventriloquism, repeating political theory without political urgency. To be more specific to Georgetown, it’s common for Georgetown administration and faculty to partake in discussions of radical theory without reflecting it in structural practice. It’s easy to speak about the settler colonial state and Eurocentric knowledge systems without interrogating faculty structures that reproduce said Eurocentrism, or challenging the day-to-day actors that perpetuate said systems. At the library, we see a lot of passive regurgitation of ideas without effectual implications on student or faculty behavior.

Forbes, writing from California in the 1970s after the AIM movement, notes how biased and/or racist scholarship is much more insidious than moral wrong: “such propaganda kills,” he says in Columbus and Other Cannibals. Some white authors—many of whom are sanctified as neutral objects in Lau—have, as he writes, been responsible for doing “irreparable damage” to Indigenous people, how they are perceived, and therefore how they are treated. He likens this sort of literature—fictional and nonfiction—to “ammunition” for racist teachers, missionaries, and other actors to justify elimination and indignification.

Part of this is also reflected in terms of absence. There is a dearth of Indigenous literature in Lau, especially specific to discussion of the displacement of Piscataway and Nacotchtank peoples from the land Georgetown occupies. Though a number of Native American hymnbooks exist in the Shea Collection, Lau too easily erases Indigenous knowledge systems from the epistemological traditions of Georgetown. And in prizing archives, Lau frames epistemology as fixed rather than held in communities and peoples, which bucks against a number of Indigenous theories about knowledge and knowledge passage.

NEXT: Observatory

0 notes

Text

Recommended reading for leftists

Introduction and disclaimer:

I believe, in leftist praxis (especially online), the sharing of resources, including information, must be foremost. I have often been asked for reading recommendations by comrades; and while I am by no means an expert in leftist theory, I am a lifelong Marxist, and painfully overeducated. This list is far from comprehensive, and each author is worth exploring beyond the individual texts I suggest here. Further, none of these need to be read in full to derive benefit; read what selections from each interest you, and the more you read the better. Many of these texts cannot truly be called leftist either, but I believe all can equip us to confront capitalist hegemony and our place within it. And if one comrade derives the smallest value or insight herefrom, we will all be better for it. After all... La raison tonne en son cratère. Alone we are naught, together may we be all. Solidarity forever.

***

(I have split these into categories for ease of navigation, but there is plenty of overlap. Links included where available.)

Classics of socialist theory

~

Capital (vol.1) by Karl Marx

Marx’s critique of political economy forms the single most significant and vital source for understanding capitalism, both in our present and throughout history. Do not let its breadth daunt you; in general I feel it’s better to read a little theory than none, but nowhere is this truer than with regards to Capital. Better to read 20 pages of Capital than 150 pages of most other leftist literature. This is not a book you need to ‘finish’ in order to benefit from, but rather (like all of Marx’s work) the backbone of theory which you will return to throughout your life. Read a chapter, leave it, read on, read again.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Capital-Volume-I.pdf

The Prison Notebooks by Antonio Gramsci

In our current epoch of global neoliberal capitalism, Gramsci’s explanation of hegemony is more valuable than much of the economic or outright revolutionary analyses of many otherwise vital theory. Particularly following the coup attempt and election in America, as well as Brexit and abusive government responses to Covid, but the state violence around the world and the advent of fascism reasserts Gramsci as being as pertinent and prophetic now as amidst the first rise of fascism.

https://abahlali.org/files/gramsci.pdf

Imperialism: The Highest Stage Of Capitalism by V.I. Lenin

Like Marx, for many Lenin’s work is the backbone of socialist theory, particularly in pragmatic terms. In much of his writing Lenin focuses on the practical processes of revolutionary transition from capitalism to communism via socialism and proletarian leadership (sometimes divisively among leftists). Imperialism is perhaps most valuable today for addressing the need for internationalist proletarian support and solidarity in the face of global capitalist hegemony, arguably stronger today than in Lenin’s lifetime.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1916/imp-hsc/imperialism.pdf

Socialism: Utopian And Scientific by Friedrich Engels

Marx’s partner offers a substantial insight into the material reality of socialism in the post-industrial age, offering further practical guidance and theory to Marx and Engels’ already robust body of work. This highlights the empirical rigour of classical Marxist theory, intended as a popular text accessible to proletarian readers, in order to condense and to some extent explain the density of Capital. Perhaps even more valuable now than at the time it was first published.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1880/soc-utop/index.htm

In Defense Of Marxism by Leon Trotsky

It has been over a decade since I have read any Trotsky, but this seems like a very good source to get to grips with both classical Marxist thought and to confront contemporary detractors. In many ways, Trotsky can be seen as an uncorrupt symbol of the Leninist dream, and in others his exile might illustrate the dangers of Leninism (Stalinism) when corrupt, so who better to defend the virtues of the system many see as his demise?

https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/idom/dm/dom.pdf

The Conquest Of Bread by Pyotr Kropotkin

Krapotkin forms the classical backbone of anarchist theory, and emerges from similar material conditions as Marxism. In many ways, ‘the Bread book’ forms a dual attack (on capitalism and authoritarianism of the state) and defence (of the basic rights and needs of every human), the text can be seen as foundational to defining anarchism both in overlap and starkly in contrast with Marxist communism. This is a seminal and eminent text on self-determination, and like Marx, will benefit the reader regardless of orthodox alignment.

https://libcom.org/files/Peter%20Kropotkin%20-%20The%20Conquest%20of%20Bread_0.pdf

Leftism of the 20th Century and beyond

~

Freedom Is A Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, And The Foundations Of A Movement by Angela Davis

This is something of a placeholder for Davis, as everything she has ever put to paper is profoundly valuable to international(ist) struggles against capitalism and it’s highest stage. Indeed, the emphasis on the relationship between American and Israeli racialised state violence highlights the struggles Davis has continually engaged since the late 1960s, that of a united front against imperialist oppression, white supremacists, patriarchal capitalist exploitation, and the carceral state.

https://www.docdroid.net/rfDRFWv/freedom-is-a-constant-struggle-pdf#page=6

Postmodernism, Or, The Cultural Logic Of Late Capitalism by Frederic Jameson

A frequent criticism of Marxism is the false claim that it is decreasingly relevant. Here, Jameson presents a compelling update of Marxist theory which addresses the hegemonic nature of mass media in the postmodern epoch (how befitting a tumblr post listing leftist literature). Despite being published in the early ‘90s, this analysis of late capitalism becomes all the more pertinent in the age of social media and ‘influencers’ etc., and illustrates just how immortal a science ours really is.

https://is.muni.cz/el/1423/jaro2016/SOC757/um/61816962/Jameson_The_cultural_logic.pdf

The Ecology Of Freedom: The Emergence And Dissolution Of Hierarchy by Murray Bookchin

I have not read this in depth, and take issue with some of Bookchin’s ideas, but this seems like a very good jumping off point to engage with ecosocialism or red-green theory. Regardless of any schism between Marxist and anarchist thought, the importance of uniting together to stem the unsustainable growth of industrialised capitalism cannot be denied. Climate change is unquestionably a threat faced by us all, but which will disproportionately impact the most disenfranchised on the planet.

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/murray-bookchin-the-ecology-of-freedom.pdf

Why Marx Was Right by Terry Eagleton

I’ve only read excerpts of this; I know Eagleton better for his extensive work on Marxist literary criticism, postmodernity, and postcolonial literature, so I’m including this work of his as a means of introducing and engaging directly with Marxism itself, rather than the synthesis of diverse fields of analysis. But Eagleton generally does a very good job of parsing often incredibly dense concepts in an accessible way, so I trust him to explain something so obvious and self-evident as why Marx was right.

https://filosoficabiblioteca.files.wordpress.com/2018/12/EAGLETON-Terry-Why-Marx-Was-Right.pdf

By Any Means Necessary by Malcolm X

Malcolm X is one of the pre-eminent voices of the revolutionary black power movement, and among the greatest contributors to black/American leftist thought. This is a collection of his speeches and writings, in which he eloquently and charismaticly conveys both his righteous outrage and optimism for the future. Malcolm X’s explicitly Marxist and decolonial rhetoric is often downplayed since his assassination, but even the title and slogan is borrowed from Frantz Fanon.

Feminism and gender theory

~

Sister Outsider: Essays And Speeches by Audre Lorde

The primary thrust of this collection is the inclusion of ‘The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle The Master’s House’, probably Lorde‘s most well known work, but all the contents are eminently worthwhile. Lorde addresses race, capitalist oppression, solidarity, sexuality and gender, in a rigourously rhetorical yet practical way that calls us to empower one another in the face of oppression. Lorde’s poetry is also great.

http://images.xhbtr.com/v2/pdfs/1082/Sister_Outsider_Essays_and_Speeches_by_Audre_Lorde.pdf

Feminism Is For Everybody by bell hooks

A seminal addition to Third Wave Feminist theory, emphasising the reality that the aim of feminism is to confront and dismantle patriarchal systems which oppress - you guessed it - everybody. This book approaches feminism through the lens of race and capitalism, feeding into the discourse on intersectionality which many of us now take as a central element of 21st Century feminism.

https://excoradfeminisms.files.wordpress.com/2010/03/bell_hooks-feminism_is_for_everybody.pdf

Gender Trouble: Feminism And The Subversion Of Identity by Judith Butler

Butler and her work form probably the single most significant (especially white) contribution to Third Wave Feminism, as well as queer theory. This may be a somewhat dense, academic work, but the primary hurdle is in deconstructing our existing perceptions of gender and identity, which we are certainly better equipped to do today specifically thanks to Butler. Vitally important stuff for dismantling hegemonic patriarchy.

https://selforganizedseminar.files.wordpress.com/2011/07/butler-gender_trouble.pdf

Trans Liberation: Beyond Pink Or Blue by Leslie Feinberg

Feinberg is perhaps the foundational voice in trans theory, best known for Stone Butch Blues, but this text seems like a good point to view hir push into mainstream acceptance where ze previously aligned hirself and trans groups more with gay and lesbian subcultures. A central element here is the accessibility and deconstruction of hegemonic gender and expression, but what this really expresses is a call for solidarity and support among marginalised classes, in a fight for our mutual visibility and survival, in the greatest of Marxist feminist traditions.

The Haraway Reader by Donna Haraway

Haraway is perhaps better known as a post-humanist than a Marxist feminist, but in all honesty, I am not sure these can be disentangled so easily. My highest recommendation is the essay ‘A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century‘, but it is in many ways concerned more with aesthetics and media criticism than anything practical, and Haraway’s engagement with technology has only become more significant, with the proliferation of smartphones and wifi, to understanding our bodies and ourselves as instruments of resistance.

https://monoskop.org/images/5/56/Haraway_Donna_The_Haraway_Reader_2003.pdf

Postcolonialism

~

The Wretched Of The Earth by Frantz Fanon

Perhaps my highest recommendation, this will give you better insight into late stage (postcolonial) capitalism than perhaps anything else. Fanon was a psychologist, and his analyses help us parse the internal workings of both the capitalist and racialised minds. I don’t see this work recommended nearly enough, largely because Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks is a better source for race theory, but The Wretched Of The Earth is the best choice for understanding revolutionary, anti-capitalist, and decolonial ideas.

http://abahlali.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Frantz-Fanon-The-Wretched-of-the-Earth-1965.pdf

Orientalism by Edward Said

This is probably the best introduction to postcolonial theory, particularly because it focuses on colonial/imperialist abuses in media and art. Said’s later work Culture And Imperialism may actually be a better source for strictly leftist analysis, but this is the groundwork for understanding the field, and will help readers confront and interpret everything from Western military interventionism to racist motifs in Disney films.

https://www.eaford.org/site/assets/files/1631/said_edward1977_orientalism.pdf

Decolonisation Is Not A Metaphor by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang

In direct response to Fanon’s call to decolonise (the mind), Tuck and Yang present a compelling assertion that the abstraction of decolonisation paves the way for settler claims of innocence rather than practical rapatriation of land and rights. The relatively short article centres and problematises ongoing complicity in the agenda of settler-colonial hegemony and the material conditions of indigenous groups in the postcolonial epoch. Important stuff for anti-imperialist work and solidarity.

https://clas.osu.edu/sites/clas.osu.edu/files/Tuck%20and%20Yang%202012%20Decolonization%20is%20not%20a%20metaphor.pdf

The Coloniser And The Colonised by Albert Memmi

Often read in tandem with Fanon, as both are concerned with trauma, violence, and dehumanisation. But further, Memmi addresses both the harm inflicted on the colonised body and the colonisers’ own culture and mind, while also exploring the impetus of practical resistance and dismantling imperialist control structures. This is also of great import to confronting detractors, offering the concrete precedent of Algerian decolonisation.

https://cominsitu.files.wordpress.com/2020/05/albert-memmi-the-colonizer-and-the-colonized-1.pdf

Can The Subaltern Speak? by Gayatri Spivak

This relatively short (though dense) essay will ideally help us to confront the real struggles of many of the most disenfranchised people on earth, removing us from questions of bourgeois wage-slavery and focusing on the right to education and freedom from sexual assault, not to mention the legacy of colonial genocide.

http://abahlali.org/files/Can_the_subaltern_speak.pdf

Wider cultural studies

~

No Logo by Naomi Klein

I have some qualms with Klein, but she nevertheless makes important points regarding the systemic nature of neoliberal global capitalism and hegemony. No Logo addresses consumerism at a macro scale, emphasising the importance of what may be seen as internationalist solidarity and support and calling out corporate scapegoating on consumer markets. I understand that This Changes Everything is perhaps even better for addressing the unreasonable expectations of indefinite and unsustainable growth under capitalist systems, but I haven’t read it and therefore cannot recommend; regardless, this is a good starting point.

https://archive.org/stream/fp_Naomi_Klein-No_Logo/Naomi_Klein-No_Logo_djvu.txt

The Black Atlantic: Modernity And Double Consciousness by Paul Gilroy

This is an important source for understanding the development of diasporic (particularly black) identities in the wake of the Middle Passage between African and America, but more generally as well. This work can be related to parallel phenomena of racialised violence, genocide, and forced migration more widely, but it is especially useful for engaging with the legacy of slavery, the cultural development of blackness, and forms of everyday resistance.

https://dl1.cuni.cz/pluginfile.php/756417/mod_resource/content/1/Gilroy%20Black%20Atlantic.pdf

Imagined Communities: Reflections On The Origin And Spread Of Nationalism by Benedict Anderson

This text is important in understanding the nature of both high colonialism and fascism, perhaps now more than ever. Anderson examines the political manipulation and agenda of cultural production, that is the propagandised, artificial act of nation building. This analyses the development of nation states as the norm of political unity in historiographical terms, as symptomatic of old school European imperialism. Today we may see this reflected in Brexit or MAGA, but lebensraum and zionism are just as evident in the analysis.

https://is.muni.cz/el/1423/jaro2016/SOC757/um/6181696/Benedict_Anderson_Imagined_Communities.pdf

Discipline And Punish: The Birth Of The Prison by Michel Foucault

Honestly, I am not sure if this should be on this list; I would certainly not call it leftist. That said, it is a very important source to inform our perceptions of the nature of institutional power and abuse. It is also unquestionable that many of the pre-eminent left-leaning scholars of the past fifty years have been heavily influenced, willing or not, by Foucault and his post-structuralist ilk. A worthwhile read, especially for queer readers, but take with a liberal (zing!) helping of salt.

https://monoskop.org/images/4/43/Foucault_Michel_Discipline_and_Punish_The_Birth_of_the_Prison_1977_1995.pdf

Trouble In Paradise: From The End Of History To The End Of Capitalism by Slavoj Žižek

Probably just don’t read this, it amounts to self-torture. Okay but seriously, I wanted to include Žižek (perhaps against my better judgement), but he is probably best seen as a lesson in recognising theorists as fallible, requiring our criticism rather than being followed blindly. I like Žižek, but take him as a kind of clown provocateur who may lead us to explore interesting ideas. He makes good points, but he also... Doesn’t... Watch a couple youtube videos and decide if you can stomach him before diving in.

Additional highly recommended authors (with whom I am not familiar enough to give meaningful descriptions or specific recommended texts) (let me know if you find anything of significant value from among these, as I am likely unaware!):

Theodor Adorno (of the Frankfurt School, which also included Herbert Marcuse, Erich Fromm, and Walter Benjamin, all of whom I’d likewise recommend but with whom I have only passing familiarity) was a sociologist and musicologist whose aesthetic analyses are incredibly rich and insightful, and heavily influential on 20th Century Marxist theory.

Sara Ahmed is a significant voice in Third Wave Feminist criticism, engaging with queer theory, postcoloniality, intersectionality, and identity politics, of particular interest to international praxis.

Mikhail Bakhtin was a critic and scholar whose theories on semiotics, language, and literature heavily guided the development of structuralist thought as well as later Marxist philosophy.

Mikhail Bakunin is perhaps the closest thing to anarchist orthodoxy. Consistently involved with revolutionary action, he is known as a staunch critic of Marxist rhetoric, and a seminal influence on anti-authoritarian movements.

Silvia Federici is a Marxist feminist who has contributed significant work regarding women’s unpaid labour and the capitalist subversion of the commons in historiographical contexts.

Mark Fisher was a leftist critic whose writing on music, film, and pop culture was intimately engaged with postmodernity, structuralist thought, and most importantly Marxist aesthetics.

Che Guevara was a major contributor to revolutionary efforts internationally, most notably and successfully in Cuba. His writing is robustly pragmatic as well as eloquent, and offers practical insight to leftist action.

Hồ Chí Minh was a revolutionary communist leader of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, and a significant contributor to revolutionary communist theory and anti-imperialist practice.

C.L.R. James is a significant voice in 20th Century (especially black) Marxist theory, engaging with and criticising Trotskyist principles and the role of ethnic minorities in revolutionary and democratic political movements.

Joel Kovel was a researcher known as the founder of ecosocialism. His work spans a wide array of subjects, but generally tends to return to deconstructing capitalism in its highest stage.

György Lukács was a critic who contributed heavily to the Western Marxism of the Frankfurt School and engaged with aesthetics and traditions of Marx’s philosophical ideology in contrast with Soviet policy of the time.

Rosa Luxemburg was a revolutionary socialist organiser, publisher, and economist, directly engaged in practical leftist activity internationally for a significant part of the early 20th Century.

Mao Zedong was a revolutionary communist, founder and Chairman of the People’s Republic of China, and a prolific contributor to Marxism-Leninism(-Maoism), which he adapted to the material conditions outside the Western imperial core.

Huey P. Newton was the co-founder of the Black Panther Party and a vital force in the spread and accessibility of communist thought and practical internationalism, not to mention black revolutionary tactics.

Léopold Sédar Senghor was a poet-turned-politician who served as Senegal’s first president and established the basis for African socialism. Also central to postcolonial theory, and a leader of the Négritude movement.

***

I hope this list may be useful. (I would also be interested to see the recommendations of others!) Happy reading, comrades. We have nothing to lose but our chains.

#original#leftism#leftist#Marxist#Marxism#socialist#socialism#literature#reading list#critical theory

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

I have a question about your opinion as a historian about how to deal with problematic past. I am French, not American, so not quite as aware of what is happening right now in the US regarding statues as I probably should. My question is the following: many of the politicians who promoted (admittedly white) social equality in France, worked on reforming labor laws, etc, in the 19th / 20th century were certainly not anti-colonialist. How to deal with this "mixed legacy" today? Best wishes to you!

First off, I am honoured that you would ask me this question. Disclaimer, my work in French history is largely focused on the medieval era, rather than modern France, and while I have studied and traveled in France, and read and (adequately?) speak French, I am not French myself. So this should be viewed as the perspective of a friendly and reasonably well-informed outsider, but not somebody from France themselves, and therefore subject to possible errors or otherwise inaccurate statements. But this is my perception as I see it, so hopefully it will be helpful for you.

(By the way if you’re interested, my post on the American statue controversy and the “preserving history!” argument is here. I originally wrote it in 2017, when the subject of removing racist monuments first arose, and then took another look at it in light of recent events and was like “WELP”.)

There’s actually a whole lot to say about the current crisis of public history in a French context, so let me see if I can think where to start. First, my chief impression is that nobody really associates France with its historical empire, the same way everyone still has either a positive or negative impression of the British Empire and its real-world effects. The main international image of France (one carefully cultivated by France itself) is that of the French Revolution: storming the Bastille, guillotining aristocrats, Liberté, égalité, fraternité, a secular republic overcoming old constraints of a hidebound Catholic aristocracy and reinventing itself as a Modern Nation. Of course, less than a generation after the Revolution (and this has always amused/puzzled me) France swung straight back into autocratic expansionist empire under Napoleon, and its colonialism efforts continued vigorously alongside its European counterparts throughout the nineteenth and well into the twentieth century. France has never really reckoned with its colonialist legacy either, not least because of a tendency in French public life for a) strong centralization, and b) a national identity that doesn’t really allow for a hyphen. What I mean by that is that while you can be almost anything before “American,” ie. African-American, Latino-American, Jewish-American, Muslim-American, etc, you are (at least in my experience) expected to only be “French.” There is a strong nationalistic identity primarily fueled by language, values, and lifestyle, and the French view anyone who does not take part in it very dimly. That’s why we have the law banning the burka and arguments that it “inhibits” Muslim women from visually and/or emotionally assimilating into French culture. There is a very strong pressure for centralization and conformity, and that is not flexible.

Additionally, the aforementioned French lifestyle identity involves cafe culture, smoking, and drinking alcohol -- all things that, say, a devout Muslim is unlikely to take part in. The secularism of French political culture is another factor, along with the strict bureaucracy and interventionist government system. France narrowly dodged getting swept up in the right-wing populist craze when it elected Emmanuel Macron over Marine Le Pen (and it’s my impression that the FN still remains relatively popular) but it also has a deep-grained xenophobia. I’m sure you remember “French Spiderman,” the 22-year-old man from Mali who climbed four stories of a building in Paris to rescue a toddler in 2018. He was immediately hailed as a hero and allowed to apply for French citizenship, but critics complained about him arriving in France illegally in the first place, and it happened alongside accelerated efforts to deny asylum seekers, clear out the Calais migrant camp, and otherwise maintain a hostile environment. The terror attacks in France, such as 2015 in Paris and the 2016 Bastille Day attack in Nice, have also stiffened public opinion against any kind of accommodation or consideration of non-French (and by implication, non-white) Frenchpeople. The Académie Française is obviously also a very strong linguistic force (arguably even more so than the English-only movement in America) that excludes people from “pure” French cultural status until they meet its criteria. There really is no French identity or civic pride without the French language, so that is also something to take into consideration.

France also has a strong anti-authority and labor rights movement that America does not have (at least the latter). When I was in France, the joke was about the “annual strike” of students and railway workers, which was happening while I was trying to study, and we saw that with the yellow jacket protests as well. Working-class France is used to making a stink when it feels that it’s being disrespected, and while I can’t comment in detail on how the racial element affects that, I know there has been tension and discontent from working-class, racial-minority neighborhoods in Paris about how they’ve been treated (and during the recent French police brutality protests, the police chief rejected any idea that the police were racist, despite similar deaths in custody of black men including another French Malian, Adama Traoré.) All of this adds up to an atmosphere in which race relations, and their impact on French history, is a very fraught subject in which discussions are likely to get heated (as discussions of race relations with Europeans and white people tend to get, but especially so). The French want to be French, and feel very strongly that everyone else in the country should be French as well, which can encompass a certain race-blindness, but not a cultural toleration. There’s French culture, the end, and there isn’t really an accommodation for hybrid or immigrant French cultures. Once again, this is again my impression and experience.

The blind spot of 19th-century French social reformers to colonialism is not unlike Cold War-era America positioning itself as the guarantor of “freedom and liberation” in the world, while horrendously oppressing its black citizens (which did come in for sustained international criticism at the time). Likewise with the American founding fathers including soaring rhetoric about the freedom and equality of all (white) men in the Constitution, while owning slaves. The efforts of (white) social reformers and political activists have refused to see black and brown people as human, and therefore worthy of meriting the same struggle for liberation, for... well, almost forever, and where those views did change, it had to come about as a process and was almost never there to start with. “Scientific” white supremacy was especially the rage in the nineteenth century, where racist and imperialist European intellectuals enjoyed a never-ending supply of “scientific” literature explaining how black, brown, and other men of color were naturally inferior to white men and they had a “duty” to civilize the helpless people of Africa, Asia, Latin America, and so on, who just couldn’t aspire to do it themselves. (This is where we get the odious “white man’s burden” phrase. How noble of them.) So the nineteenth-century social reformers were, in their minds, just doing what science told them to do; slavery abolitionists and other relief societies for black and brown people were often motivated by deeply racist “assimilationist” ideas about making these poor helpless people “fit” for white civilization, at which point racial prejudice would magically end. This might have been more “benevolent” than outright slave-owning racism, but it was no less damaging and paternalistic.

If you’re interested in reading about French colonialism and postcolonialism from a Black French perspective, I recommend Frantz Fanon (who you may have already heard of) and his 1961 magnum opus The Wretched of the Earth/ Les Damnés de la Terre. (There is also his 1952 work, Black Skin, White Masks.) Fanon was born in Martinique, served in World War II, and was part of the struggle for Algerian liberation from France. He was a highly influential and controversial postcolonial theorist, not least for his belief that decolonialization would never be achieved without violence (which, to say the least, unnerved genteel white society). I feel as if France in general needs to have a process of deep soul-searching about its relationship to race and its own imperial history (French Indochina/Vietnam being another obvious example with recent geopolitical implications), because it’s happy to let Britain take the flak for its unexamined and triumphalist imperial nostalgia. (One may remark that of course France is happy to let Britain make a fool of itself and hope that nobody notices its similar sins....) This is, however, currently unlikely to happen on a broad scale for the social and historical reasons that I discussed above, so I really applaud you for taking the initiative in starting that conversation and reaching out for resources to help you in doing it. Hopefully it will help you put the legacy of these particular social reformers in context and offer you talking points both for what they did well and where their philosophy fell short.

If there does come a point of a heightened racial conversation and reckoning in France (and there have been Black Lives Matter protests there in the last few weeks, so it’s not impossible) I would be curious to see what it looks like. It’s arguably one of the Western countries that has least dealt with its racial issues while making itself into the standard-bearer for secular Western liberalism. France has also enthusiastically joined in the EU, whereas Britain has (rather notoriously....) separated from all that, which makes Britain look provincial and isolated while France can position itself as a global leader with a more internationalist outlook. Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel are currently leading the effort for the $500 billion coronavirus rescue package for the EU, which gives it a sense of statesmanship and stature. It will be interesting to see how that continues to change and develop vis-a-vis race, or if it does.

Thanks so much for such an interesting question, and I hope that helped!

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caretaking and resistance. Thinking again about the quote from ‘Aha Makhav/Mojave writer Natalie Diaz, in an interview about her book Postcolonial Love Poem (March 2020), discussing how love can be practiced both as a part of and apart from resistance (”A dangerous way of thinking lately is that we love as resistance. I understand that, but I refuse to let my love be only that. I am not loving against America or even in spite of it. I am loving because I was made to love, love was made for me.”)

Reminds me of a few related comments from other Indigenous women.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg): This continual pattern of the gutting of mass mobilization by royal commissions, national inquiries, or this time, the promise of a couple of “high level meetings”, is not a trick we can continually fall for [...]. Here we are two years later, with the components of the movement that were begging for colonial recognition [...], it matters how change is achieved. What happens when we build movements that refuse colonial recognition as a starting point and turn inwards building a politics of refusal that isn’t just productive, but that is generative [...]. Movement building is a productive or generative politics of refusal [...]. We recognize when particular animals return to our territory in the spring, and when plants and medicines reappear after winter rests. Recognition for us is about presence, about profound listening and about recognizing and affirming the light in each other, as a mechanism for nurturing and strengthening internal relationships to our Nishnaabeg worlds. It is a core part of our political systems because they are rooted in our bodies and our bodies are not just informed by but created and maintained by relationships of deep reciprocity. [...] Recognition within Anishinaabeg intelligence is a process of seeing another being’s core essence, it is a series of relationships. It is reciprocal, continual and a way of generating society. It amplifies Anishinaabewin -- all of the practices and intelligence that makes us Anishinaabeg. It cognitively reverses the violence of dispossession, because what’s the opposite of dispossession in Indigenous thought again? Not possession because we’re not supposed to be capitalists, but connection -- a coded layering of intimate interconnection and interdependence that creates a complicated algorithmic network of presence, reciprocity, consent, and freedom.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Deanna Reder (Cree-Metis): “[A] sole focus on narratives of resistance replicates the founding ideas in much criticism about Native American literature that all Indigenous texts only exist because of the existence of the colonizer […]. [T]here is more to the politics of self-determination than resistance to oppression.”

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Melanie K. Yazzie (Dine/Navajo): Pauline Whitesinger, a Big Mountain matriarch who was prominent in the struggle on Black Mesa to resist forced relocation in the 1970s and 1980s, likened this network of extractive practices to “putting your hand down someone’s throat and squeezing the heart out”. […] Indigenous feminist and Dine land defenders […] draw connections between the everyday lived material realities of environmental violence and larger structures of colonialism [and] capitalism […]. These connections are key for understanding the politics of life espoused by Big Mountain matriarchs like Whitesinger and Ruth Benally that emerged to contest these material realities of environmental violence and death […].

The land-based paradigm that emerged from the context of these women’s resistance to forced removal had, at its center […] both an unwavering critique of the almost totalizing death that extractive practices represented […] and a framework for Dine conceptions of life rooted in one’s relationships with the land and responsibilities to life-giving forces and beings like sheep, corn, family […] an entire web of relations that have specific connections to specific places. In other words, through the act of resisting forced removal, these women enacted a politics of life that was both defensive (as in to defend life against the destruction of extraction) and generative (as in to caretake life through an ethos and practice of kinship obligation).

This dual move of defending and caretaking relational life is at the heart of the Dine concept of k’e, which is still widely practiced as a social and ontological custom in both Dine resistance struggles and in everyday Dine life. […] Our decolonial aspirations are not just about sovereignty and exerting independence over energy development […]. Our politics of [...] decolonization must thus not only act as a form of resistance to the death drive of capitalism and settler colonialism, but also function as a vehicle for imagining a politics of life that will refuse death and instead secure a future for all our relations. […] I see the work emerging from […] Indigenous feminism as a sign that intellectuals writing from both the front lines of Indigenous resistance [...] are formulating a politics of relational life that can serve as a form of multispecies justice […].

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

“WE ARE ALL SOMEWHAT COLONIZED IN OUR EXISTENCE”: JAMIE CHIANG IN CONVERSATION WITH ZAHRA PATTERSON

UDP apprentice Jamie Chiang interviewed writer and educator Zahra Patterson in February 2019 after the release of her UDP title Chronology, recent winner of the Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Memoir/Biography. They discussed Zahra's journaling in Cape Town; her friendship with Liepollo Ranekoa, who passed away in 2012; the impact of language choice in postcolonial literature; tattoos; and more.

Taking as its starting point an ultimately failed attempt to translate a Sesotho short story into English, Chronology explores the spaces language occupies in relationships, colonial history, and the postcolonial present. It is a collage of images and documents, folding on words-that-follow-no-chronology, unveiling layers of meaning of queering love, friendship, death, and power.

Can you talk about the background of your decision to go to Cape Town to find who you are or the meaning of life? Did you find it? (In Chronology, Zahra refers to her journey to Cape Town as a search for herself.)

Yeah, I mean sometimes I get a little dramatic perhaps when I'm writing in my journal.

How old were you? How many years ago was that?

It was the end of 2009 into 2010, so I would have been in my late twenties. I feel a journal is a place to express one's ideas, but it's also a creative space. I wouldn't take myself totally seriously in everything that comes out in a journal. I think there's definitely some self-awareness of one's own—my self importance, but also the quest to find oneself is not just to be made fun of. I think it's an important concept.

How long did you stay in Cape Town?

I was there for around five weeks. As far as the decision to go, it was more spur of the moment. I was in South Africa for a wedding. My cousin got married and instead of going off traveling that far for a week, I thought I would just spend a couple of months if I had to go to that part of the world; there's no point in going for a week, so I was going to stay. I hadn't actually decided where I was going after the wedding until I got there, and Cape Town seemed to make the most sense to me.

It perhaps felt the least imperialistic to go and spend time in such a cosmopolitan, international city as opposed to going somewhere more remote. You're either a tourist or a local, whereas Cape Town is an easy city to integrate into.

I see. On page 33, you mention that you have a tattoo, and in the caption there is this word ke nonyana. What does ke nonyana mean?

It means I'm a bird.

That's the first word you spoke in Sesotho?

Yes. I found the words in Liepollo’s English-Sesotho dictionary one day, and when she came home I spoke them. It meant a lot to her that I’d engaged with her language.

If you don’t mind, could you elaborate the story behind Liepollo’s colleague’s Facebook profile picture. What happened?

It was the day she died, and his Facebook profile changed to her picture. It was an image of her. That was jarring because why somebody would put an image of a friend up, and there are very few circumstances that someone would do something like that and usually it's because they're dead. So when I saw that his Facebook picture changed to her face, it occurred to me that something terrible had happened. And I was at work at the time, so it was just very disorienting.

Sorry to hear that. Did you get your tattoo because of this?

Yeah, so I didn't have anybody to mourn with because I had met Liepollo in Cape Town and we didn't have friends in common. Actually, we had a friend in common—an American who interned at Chimurenga while I was staying with Liepollo who I met once at the house in Observatory and once for coffee in Brooklyn—but she had moved to D.C. by that time, so I didn't reach out to her. It was a very isolated mourning experience. That's kind of why I got the tattoo, just to have her with me and to have that symbol and to think of her every day. Because when you have a long distance friendship, you're not going to think of the person every day. We were in touch every few months. I don’t want to forget her due to not having a lot of people to remember who she was with, so I needed to make her memory permanent on me. I think everybody thinks about getting tattoos in this day and age. My rule for tattoos is if I want it for a full year, then I'll get it, and I've never wanted anything for a year. So it’s my only tattoo.

And ke nonyana sounds beautiful.

Thank you. I think it's beautiful also.

And on page 37 and 38, there’s an interesting conversation you had with a Muslim guy named Saed. I found some of his talk kind of sexist. What was your reaction when you were talking to him? It sounds like he's almost preaching to you, trying to change your idea about what a woman's purpose is in this world.

Exactly! But he also wasn't that; he was as if playing the role that he thought he was supposed to play and open to other ways of thinking. We're socialized beings, all of us. He wasn't terribly dogmatic. I don't think he'd been challenged too much in his way of thinking, but at the same time maybe he had because he was open to being challenged. So yeah, it was very interesting.

On page 47 to 48, you write about the panel What is the value of age and wisdom? at the Bronx Museum of Art. The five panelists are: Vinie Burrows, Boubacar Boris Diop, Yusef Komunyakaa, Achille Mbembe and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. There’s a quotation from Mbembe: “If the language we use is in itself a prison...We have to put a bomb under the language. Explode language!” Could you tell us more about the context?

Achille Mbembe is a leading postcolonial theorist. I think his words are also quite poetic, so he's speaking metaphorically. The context of that part of the conversation is imperialism and language. That intellectuals from formerly colonized nations use the colonial language to express decolonial ideas is problematic, but it's still very accepted. And even these intellectuals who are on the panel, they write in English and they write in French, but they also find it problematic that they do that; however, it's also part of their survival. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o wrote Decolonizing The Mind in the early eighties, where he swore off ever writing in English again, but then he is put into prison and he's exiled, so he can't actually exist in his mother tongue and his mother land; the government there has ostracized him because he speaks out against what they're doing to the people. Therefore, he has to make his life in English in America, he teaches in California.

Circumstances don't necessarily allow a person to decolonize their lives because in order to survive in this society, we are all somewhat colonized in our existence. I think that saying to put a bomb under language is saying that we need to just get our ideas out there. There’s also the visual aspect of it, I see words and letters, like, splattered. Like fucking. . .we need to fuck with language; we need to push the boundaries of language.

As Diop said “Teaching Wolof enhances self-esteem.” Does Wolof have a writing system?

I’m not positive about the history of Wolof’s writing system but I know some, especially in more northern Sub-African countries had created writing systems using Arabic script and maybe some of them now use the Latin alphabet, so I would have to look that up for Wolof specifically.

You use your mother tongue to express yourself because ideas in a specific language can't be translated. When you lose the language, you lose the culture and the history of people. Also if you're writing in any of the indigenous languages to Africa, you're not writing for the colonizer; you're writing for the people who speak that language, which is also important.

A lot of this theory, especially academic theory that is taught in universities, is very limited in its reach. I think even though these are serious intellectuals who write academic works for academia, they're aware and they're problematizing the limits of writing scholarly work for institutions that isn't necessarily reaching the people.

What other languages do you speak?

I speak French. I lived in France for awhile. I would say I used to be bilingual; I'm kind of monolingual at this point in my life.

What about in Sesotho?

I was working on the project (an attempt to translate Lits'oanelo Yvonne Nei's short story “Bophelo bo naka li maripa” from Sesotho to English) originally, but the access to the language was limited. I wasn't able to access decent grammar books, I wasn't able to access the orthography that I wanted to access so I gave up pretty quickly...but it wasn't as simple as giving up. I stepped back because I didn't really feel it was totally appropriate for me to do what I was doing. I think that’s a hugely important part of my text, the part where I put myself into conversation with Spivak and she tells me, via an essay she wrote about translation, that what I’m doing is wrong. I want to learn a language in which I'm going to be able to speak to people. I’m still not totally sure if I should have published what was supposed to be such a personal exercise, so that section with Spivak is essential to me.

On page 72, you wrote Liepollo an email about a friend who taught you how to say Your sister is a whore in Tagalog?

A friend of mine, her first love was Filipina so she knew how to insult people in Tagalog. When she said it, it sounded Spanish to me so I was wondering if that kind of insult comes with colonialism...also a misogynistic perspective can come. Not to say that misogyny doesn't exist in all cultures, although I think there are probably some cultures where it doesn't exist. Just problematizing the way language can infiltrate into a culture and then become part of the existing language but isn't part of that cultural history—the etymology isn’t actually Filipino; the etymology is Spanish.

Are there any books and authors that inspire you a lot?

For this work, Dictee by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, that was a huge inspiration. Mouth: Eats Color by Sawako Nakayasu in terms of thinking about different ways, different things that can be done with form and then different things that can be done with translation. It was very liberating to read those two authors. I don't identify as a translator nor as a poet, so most of the things I've read are novels. My background is primarily in postmodern and postcolonial pieces of literature. I also thought about the nature of collage while I was working on Chronology. I looked at Wangechi Mutu’s work specifically for inspiration, but I’ve loved Romare Bearden’s work for years.

Thanks for sharing. The last question, what are you working on now?

I've started writing and hopefully I'm able to continue it. It's a piece that will potentially be called Policy. I'm an educator and I'm pretty passionate about how distorted and messed up the reality of public school systems is in this country. Although one could say I've been researching since I've been an adult, I started specific research for Policy last summer and I didn't start writing it until a couple of weeks ago. It's experimental in form. I'd say it's fiction meets theory, whereas Chronology is memoir meets theory. I'm not sure exactly where it's going but I'm thinking critically about charter schools and desegregation efforts in New York City and also the history of that. So going back to Brown versus the Board of Ed. . .I'll probably address school shootings, the school-to-prison pipeline, school lunches, teachers’ strikes; it’s about as intersectional an issue as there is—how we educate ourselves as a nation, and on the stolen land of our nation.

I think right now, especially with the current administration, though public schools have been in danger for a very long time, our current secretary of education is a billionaire who wants to privatize education, so her agenda is to destroy our public school infrastructure. It's worrisome. Processing this information in a way makes me very angry because it's systemic. It's how you keep people oppressed. If you don't give people access to education, you're not giving them access to themselves. Never mind the tools they need to achieve and succeed in a capitalist society.

I don't feel the United States has a liberatory agenda for education and I want to explore that a little bit in the history of curriculums and pedagogy because there have been, at the turn of the century, there were some really interesting education theorists like John Dewey and Ella Flagg Young, and their ideas for public education were very progressive, such as student driven classrooms, and not having really punitive systems. You find that education in private schools but rarely in public schools, so why are we not educating our youth in ways that let them think critically about the world that they're living in? Educating children to just follow rules and memorize doesn't work for most children. How many do you know in public schools who are excited to go to school every day? I think humans naturally are curious and want to learn and know things. So why is education taking that away from children?

I don't know exactly how the project is going to manifest. It will be weird.

Zahra Patterson’s first book, Chronology (Ugly Duckling Presse 2018), won the 2019 Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Memoir/Biography and received a Face Out Fellowship from CLMP. Her short works have appeared in Kalyani Magazine The Felt, and unbag (forthcoming). A reading of her play, Sappho's Last Supper, was staged at WOW Café Theatre. She is the creator of Raw Fiction and currently teaches high school English at a Quaker boarding school. Her writing has been supported by Mount Tremper Arts and Wendy’s Subway, and her community work has been supported by Brooklyn Arts Council, The Pratt Center, and many individuals. She holds an MFA in Writing from Pratt Institute.

6 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

Not Today's Yesterday - Seeta Patel

Seeta Patel is a force to be reckoned with. Her strong will, magnetic presence and passionate ideas come across equally as powerful on and off stage. But the life of a dance artist isn’t as glamorous as it may seem. Seeta is extremely busy with multiple projects on the go at once but I manage to catch her during a brief lunch break while rehearsing with a group of rising Bharatanatyam dancers in Birmingham as part of #TheNatyaProject, to chat about her exciting new tour.

Not Today’s Yesterday is an international collaboration between UK award-winning Bharatanatyam artist Seeta Patel and Australian choreographer Lina Limosani. This work blends classical Indian dance (Bharatanatyam) & contemporary dance in a striking, intelligent and engaging evisceration of ‘pretty’ and ‘suitable’ historical stories. It is a one-woman show which subversively co-opts whitewashing against itself.

“The inspiration stems from our concerns that revisionist and airbrushed histories have become a central issue of tension throughout the world, in particular in Western democracies.”

I first asked Seeta how the idea of the work came about as I was aware that it had been a number of years in progress.

“It started with my feeling that the history of Bharatnatyam has been white-washed. Having read Unfinished Gestures by Davesh Soneji, it really blew my mind that many of us going through the system are not often taught about the social and political history of the art form in its entirety. There’s more niceness rather than the grit of it. This is basically how history is white-washed in order to make it more palatable.”

I’d seen the work in progress around a year ago and it was haunting, hypnotic and extremely clever in its execution. Through the medium of a fairy-tale story, it draws people in with eerie familiarity, but as with any fairy-tale there are always dark undertones. Parts are grotesque and exaggerated with caricatures of colonial supremacy but other parts are gentle and vulnerable as Seeta gazes wide-eyed into the depths of what was.

The collaboration between Seeta and choreographer, Lina Limosani was first funded by the Arts Council’s Artist International Development Fund 2016 where Seeta travelled to Australia where Lina is based, to research and develop the work.

“Britain and Australia, amongst others, have sordid histories and relationships with indigenous and migrant communities. Skewed histories fuel a distorted sense of nationalism. This work aims to open up conversation through a clever appropriation of whitewashed histories.”

The following year, Seeta was able to gain further funding to develop the work in Poland, as another one of the collaborators was based there and perform previews of ‘Not Today’s Yesterday’ around the UK. Being based in a foreign country during this process really fuelled the creative ideas and themes, which fed into the piece.

Earlier this year they were able to sharpen the work to a fine point and received funding to perform ‘Not Today’s Yesterday’ at Adelaide Fringe Festival. During that period, they were successful in gaining a UK touring grant for this Autumn, so it has been through several stages and Seeta envisions it to live on in many different contexts, as the work deals with some of the most pressing issues of our time.

“This piece is a part of my wider work. Along with my classical work, whatever I do is political on a certain level. I can’t wake up in the morning and change the colour of my skin or the country that I’m born and live in, I am political. It’s not something I can choose to remove. I’m not of that privilege. Not in this country.”

As Seeta’s career rises and expands, I’m interested to learn about what advice she has to offer the next generation who look up to her as a role model and as an example of someone with a successful career as an Indian classical dancer or dancer from a South Asian background in this country. She’s brutally honest and explains that this career is by no means conventional, in any sense of the word. Her path has forced her to challenge the accepted ‘norms’ that we are socialised into as first and second generation South Asian immigrants who constantly strive to over-achieve. So to have to find temporary or casual work through the ebbs and flows is perfectly acceptable as it means that you can earn money, which doesn’t have to eat into the time that you want to work on dance.

“Certain professions require just as much energy as dance does, so I don’t personally believe that you can do both and give each job the commitment that it deserves.” says Seeta. “You have to understand what you really want and sometimes take scary steps to get there that you’re not confident or comfortable with.”

The interactive element of the work is the carefully curated post-show talks, as Seeta hopes that the audience becomes lured into a dark fantasy and taken on an experiential journey during the performance then the discussion afterwards is a chance for reflection and transformation.

Each performance has specifically relevant researchers, academics and powerful personalities who will help to uncover the themes behind the performance and welcome the audience to share their thoughts and ideas too.

So don’t miss out on a very special chance to experience a dance theatre work by such a phenomenal BROWNGIRL and book your tickets to a performance near you.

TOUR DATES

Seeta is on a UK Tour of her one woman dance theatre work Not Today's Yesterday this Autumn 2018. A collaboration with Limosani Projects. Tour details as follow:

- 2nd Oct - The Place

- 3rd Oct - The Place

booking info

+44 (0)20 7121 1100

SPEAKERS

2nd October

Gurminder K Bhambra is Professor of Postcolonial and Decolonial Studies in the School of Global Studies, University of Sussex.

Alice A. Procter is an art historian and museum educator. She runs

Uncomfortable Art Tours, unofficial guided tours exploring how the UK’s major art institutions came into being against a backdrop of imperialism.

Tanika Gupta - Over the past 20 years Tanika has written over 20 stage plays

that have been produced in major theatres across the UK. She has written 30

radio plays for the BBC and several original television dramas, as well as scripts

for EastEnders, Grange Hill and The Bill.

3rd October

Kenneth Tharp - Kenneth Tharp is the former Chief Executive of The Place, the

UK’s premier centre for contemporary dance.

Inua Elams - Born in Nigeria, Inua Ellams is a cross art form practitioner, a poet,

playwright & performer, graphic artist & designer and founder of the Midnight Run — an international, arts-filled, night-time, playful, urban, walking experience.

Tobi Kyeremateng - Tobi Kyeremateng is a theatre, festival and live

performance producer. She is currently Producer at Apples and Snakes,

Executive Producer (Up Next) at Bush Theatre, and Programme Coordinator at

Brainchild Festival.

- 5th Oct - Amata Theatre Falmouth University

booking info

Phone: 01326 259349

Email:

SPEAKERS - TBC

- 12th Oct - Watermans Arts Centre

booking info

Box Office: 020 8232 1010

SPEAKERS

Bidisha Mamata: Bidisha is a British writer, film-maker and broadcaster/presenter for BBC TV and radio, Channel 4 news and Sky News and is a trustee of the Booker Prize Foundation, looking after the UK's most prestigious prizes for literature in English and in translation.

- 13th Oct - Kala Sangam, Bradford

booking info

SPEAKERS

Pauline Mayers Associate Artist with the West Yorkshire Playhouse Pauline produces her own shows as The Mayers Ensemble themed around participation, intimacy and identity.

Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan is a writer, speaker,

playwright, award-winning spoken-word activist and founder of the political blog www.thebrownhijabi.com

- 23rd Oct - Patrick Centre, Birmingham

booking info

Box Office: 0844 338 5000

SPEAKERS

Dr Kehinde Andrews: is Associate Professor of Sociology, and has been leading

the development of the Black Studies Degree at Birmingham City University.

Abeera Kamran: is a visual designer and a web-developer based in Birmingham

and Karachi, Pakistan. Her creative practice is research-based and lies at the

intersections of design, archiving practices and the internet.

“Once upon a time... in a faraway land... it happened... did not happen... could have happened.”

Supported by Chats Palace, Arts Council England, Country Arts SA, Arts SA, The Place London, Adelaide Fringe Artists Fund, LWD Dance Hub, British Council, The Bench UK and NA POMORSKIEJ Artist residency.

#bharatanatyam#bharatnatyam#indian dance#indian classical dance#classical dance#dance#dancer#dancers#theatre#colonialism#white supremism#white supremisist#white superiority#australia#britain

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Recomended literature for understanding the context of coloniality in German Architectural Modernism:

Kenny Cupers´ On the Coloniality of Architectural Modernism in Germany

Itohan Osayimwese´s From Postcolonial to Decolonial Architectural History: A Method

0 notes

Text

University of Texas-San Antonio Assistant Professorship in English -- Latina/ o/ x Literatures

Deadline:

November 6

Length/Track:

Apparently tenure track

Description:

“Candidates may specialize in any aspect of Latina/ o/ x Literatures, preferably with an emphasis on the literatures of the U.S./ Mexico border; postcolonial/ decolonial theory; literary and cultural formations of Latinidad both regionally and globally; and/ or trans- and multi-disciplinary approaches to Latinx…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The Lone Wolf and Cub: A Learning Developer’s Nurture of Decolonial Pedagogy in a UK Higher Education Institution. Written by Dr Ryan Arthur,FHEA

First published in 1970, Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima’s Lone Wolf and Cub depicts the perilous journey of a swordsman and his three-year-old son (Pusateri, 2001). Set in the Tokugawa period, Koike and Kojima’s manga offers the reader an apt metaphor for a learning developer’s journey of discovery. This journey seeks to go beyond the slogans and metaphors of the ‘decolonising the curriculum’ movement to understand how these very young and ‘cub-like’ decolonial pedagogies can be deployed by learning developers in British higher education institutes (HEIs). This will involve engaging with the decolonial literature to extract a definition, present a rationale, articulate principles and provide a tangible example. This essay is significant because it seeks to contribute to the minuscule literature base of decolonial pedagogies in British HEIs. More specifically, it offers a critical review of how decolonial pedagogies can be operationalised in the learning development sector.

Introduction

This study utilises Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima’s gripping story of the Lone Wolf and Cub as a metaphor for an enlightening journey. As Giroux (1988, p.162) cites, ‘We are living out a story. There is no way to live a storyless… life’. This story adopts the funnel approach; it starts very broadly by looking at the parallels between Koike and Kojima’s manga and the subject at hand. This will lead to a focus on the matter of decolonisation; though this study’s focus is on decolonial pedagogies, the broader theme of decolonisation informs and shapes the pedagogies. Moving on, it is crucial that the author distinguishes between decolonial pedagogies from other pedagogies of disruption to give a better understanding of the field. Funnelling down even further, the author seeks to move from pedagogies to pedagogy by specifying an approach. The approach selected was the Critical Inquiry Approach, which prompted the development of six principles that will guide its usage. Also, the focus on the Critical Inquiry Approach required a rationale and an explanation of its deployment in the Learning Development sector, all of which completes a ‘general to specific’ journey of discovery. This study will commence with some parting thoughts about the practical usage of the Critical Inquiry Approach.

Lone Wolf and the Cub

First published in 1970, Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima’s Lone Wolf and Cub depicts the perilous journey of a swordsman and his three-year-old son. Set in the Tokugawa period, Koike and Kojima’s manga offers the reader an apt metaphor for not only a learning developer’s journey of discovery but also a metaphor for the nature of decolonisation itself. Koike and Kojima were captivated by the American cinematic western (Pusateri, 2001). Instead of just recreating what captivated them, the Japanese authors sought to repurpose the mythic West for their own mythic purposes (Pusateri, 2001).[1] This repurposing of Western artefacts was not simply a matter of exchange, it was also a critique of those artefacts.

Moreover, parallels between decolonisation and the Lone Wolf and Cub can also be drawn from the violence of both. Lone Wolf, in its effort to establish itself as a ‘counter-myth’, is violent ‘at an unparalleled level of extremity and departure from realism’ (Pusateri, 2001, p. 88). Likewise, decolonial projects are violent, as Sefa Dei and Simmons (2010, p. XVIII) stated in the Pedagogy of Fanon, ‘Decolonisation is violent and is a creative urgent necessity. Such violence has a cleansing force to rinse the oppressor detoxify the oppressed, and make both the oppressor and oppressed human again’. However, it must noted that it is ‘not the violence of billy clubs, bullets, or bombs but the violence of ripping a plant out of the ground, roots and all, the violence of plowing the earth to make it receptive to new seeds (Fujino et al., 2018 p. 71). Lastly, Lone Wolf is a difficult read, there are many problematic themes and unsavoury sections. Correspondingly, decolonial projects do not hold any illusions of universal and utopian ideals, ‘it is a paradigm that harbors an element of unpredictability and uncertainty’ (Mendieta, 2003, p. 159). Smith (1999, p. 186) pointed to the ‘real-life ‘dirtiness’ of political projects, or what Fanon and other anti-colonial writers would regard as the violence entailed in struggles for freedom’.

Decolonisation

The broader notion of decolonisation rests on the assumption that British Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) are sites where the transmission and production of knowledge are wholly embedded in Eurocentric epistemologies that are ‘presented’ as objective and universal (Cupples and Grosfoguel, 2018; Domínguez, 2019). It is argued that the fetishisation of Eurocentric ways of thinking, knowing and researching has prevented ‘a broader recognition and appreciation’ of an epistemic, ontological and cultural plurality (Domínguez, 2019. p. 49). This has been referred to as the ‘hubris of the zero point’ which renders alternative epistemologies as subaltern (Castro-Gómez, 2020; Domínguez, 2019).

In a direct challenge to the ‘zero point’, decolonial projects seek to deconstruct dominant Eurocentric forms of intellectual production and transmission whilst promote the pluralisation of the knowledge field (Zembylas, 2018; Mignolo, 2007; Domínguez, 2019). Such projects have a long history; (Mignolo and Escobar, 2013, p116) notes, ‘Decolonisation is an idea that is probably as old as colonisation itself. But it only becomes a project in the twentieth century’ (Mignolo, 2007; Stanek, 2019).