#ozites

Text

the ozites start genuinely worrying about my marc verrue obsession and none of them trust me when i say it's all a big set-up and hyperbole... they really CAN'T take a joke

#rambling#ozites#long sigh#i've set up a poll letting them decide whether i stop or not my joke MV stan twt account i'll keep y'all updated#for now (9 votes) it's a slim majority for me to keep going on with it

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

It is sad that fans did not get to see oz kids and wonderland kids interact in ever after high Canon, I can imagine the dialogue. Lizzie heart could say " everyone knows that The wizard of OZ is a American version of Alice in wonderland" then one of the OZ kids replies, ," everyone knows, we are the fun version"

。:゚゚(´∀`)・。

#eah#ever after high headcanons#sorry anon I was this but totally forgot to reply#I'm with oz here#ozite#ozmie#we really were indeed robed of this weren't we#mattel#everafterhigh#ever after high#anon#ask

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Be sure that you only buy pads of Genuine Ozite, those pads you buy on the street are often laced with uncut latex!

McCall's October - 1948

#1948#floor covering#pads#vintage ad#advertising#advertisement#vintage ads#1940s#1940s ad#1940's#1940's ad#funny#humor#humour

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Politics of Oz

Now for the upsetting conclusion to my series of Oz posts.

The entire essay will not be here on Tumblr. What you see here is a preview, just the first part of the longer whole. You can read the rest on my website here.

I sure would appreciate someone seeming to consider something I wrote. If you know people who might be interested, you could share it too. What do I have to do, grovel? What do you want from me bah whatever okay here's the preview (grumble grumble)

1. The Riches of Content: Oz as Pastoral, Feminist Socialist Utopia

In the original 1900 novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, the Land of Oz is fecund and full of friendly people but still a dangerous, socially unstable place. After Ozma ascends to rule the Emerald City of Oz in the second novel, she “civilizes” Oz. L. Frank Baum frames the civilized Oz not as a land of peril and adventure but as a land of wonder and delight. (“Civilizes” might seem like a questionable term for me to use, so put a pin in that.) Ozma’s “civilized” Oz is a counterpoint to the “big, cold, outside world” (Road to Oz 196). This outside world refers to the mundane labor and economic deprivation of the cruel, bleak United States and also the various analogous scary and unfriendly people and monsters who live outside Oz, including Evoldo, the Mangaboos, the Scoodlers, the Phanfasms, the Boolooroo of Sky Island, the Raks, Cor and Gos, and other tyrants and evil spirits. Chief among these is the Nome King, the only major recurring villain in the series.

A number of commentators have interpreted Ozma’s Oz as a utopia, including Sally Roesch Wagner in “The Wonderful Mother of Oz” and Suzanne Rahn in “Beneath the Surface of Ozma of Oz,” both of which I will return to below. Jack Zipes also understands Baum’s Oz as a socialist, matriarchal utopia in “Inverting and Subverting the World With Hope” in Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion. All three of these writers take Oz as a rejection or condemnation of American capitalism, though bizarrely Wagner and Zipes both interpret the Oz of the original novel, where travel is deadly and there are multiple slave-driving dictators, as already utopian. I will start by exploring what values distinguish Oz as good and correspondingly define the nature of evil in the Oz novels, concentrating on the first six books but drawing from Baum’s later work as well.

Content warning: This portion will not be on Tumblr, at least not now. But to spoil the big twist, this essay will quote and cite some very racist material. I will also discuss, with nothing graphic or detailed, genocide and other heavy topics that might be upsetting to some readers. I do not present these subjects to be shocking but hope to ultimately teach something or other.

Because Baum originally intended to end the series with The Emerald City of Oz, it serves to an extent as a statement of the series’ values overall. In this novel, the utopian, nonviolent Oz is pitted against the decidedly not-utopian Nome King and the Whimsies, Growleywogs, and Phanfasms, who want to pillage the land and enslave its people. Fittingly, for the first time, Baum describes the Ozite economy in detail. At least, this is the economy of Oz after Ozma and her allies “civilize” the land. The entire passage is relevant:

[The Emerald City] has nine thousand, six hundred and fifty-four buildings, in which lived fifty-seven thousand three hundred and eighteen people, up to the time my story opens.

All the surrounding country, extending to the borders of the desert which enclosed it upon every side, was full of pretty and comfortable farmhouses, in which resided those inhabitants of Oz who preferred country to city life. [Later novels contradict this claim, filling Oz with jungles, dangerous mountains, and other urban centers.]

Altogether there were more than half a million people in the Land of Oz—although some of them, as you will soon learn, were not made of flesh and blood as we are—and every inhabitant of that favored country was happy and prosperous.

No disease of any sort was ever known among the Ozites, and so no one ever died unless he met with an accident that prevented him from living. This happened very seldom, indeed. There were no poor people in the Land of Oz, because there was no such thing as money, and all property of every sort belonged to the Ruler. The people were her children, and she cared for them. Each person was given freely by his neighbors whatever he required for his use, which is as much as any one may reasonably desire. Some tilled the lands and raised great crops of grain, which was divided equally among the entire population, so that all had enough. There were many tailors and dressmakers and shoemakers and the like, who made things that any who desired them might wear. Likewise there were jewelers who made ornaments for the person, which pleased and beautified the people, and these ornaments were free to those who asked for them. Each man and woman, no matter what he or she produced for the good of the community, was supplied by the neighbors with food and clothing and a house and furniture and ornaments and games. If by chance the supply ever ran short, more was taken from the great storehouses of the Ruler, which were afterward filled up again when there was more of any article than the people needed.

Every one worked half the time and played half the time, and the people enjoyed the work as much as they did the play, because it is good to be occupied and to have something to do. There were no cruel overseers set to watch them, and no one to rebuke them or to find fault with them. So each one was proud to do all he could for his friends and neighbors, and was glad when they would accept the things he produced. (29–31)

The Tin Woodman also clarifies some of the economic system in The Road to Oz:

“If we used money to buy things with, instead of love and kindness and the desire to please one another, then we should be no better than the rest of the world,” declared the Tin Woodman. “Fortunately money is not known in the Land of Oz at all. We have no rich, and no poor; for what one wishes the others all try to give him, in order to make him happy, and no one in Oz cares to have more than he can use.” (164)

In “Beneath the Surface of Ozma of Oz,” Rahn draws parallels between Baum’s description of the Oz in these two novels and the socialist utopia in William Morris’s News from Nowhere (Rahn 26). The civilized Oz certainly resembles a utopian communist dictatorship but wears the clothing of a hereditary monarchy. There is no rule by the proletariat, for there are no proletariat, landowners, or bosses in Oz, yet there is a single ruler whose legitimacy rests on her being the daughter of the king who ruled before the advent of the Wizard and the Wicked Witches. Private property has been abolished through, paradoxically, the universal private ownership of all property by Ozma, who allows this property to be shared equitably among the people—how fortunate for the Ozites that Ozma stops aging. The abundance of material wealth, particularly gems and precious metals, is used in ostentatious displays, but these resources are common enough that they are ubiquitous among all Ozites. The people receive everything they desire. They work and produce of their own free will for nothing but satisfaction and the benefit of themselves and their neighbors. Baum might as well have included the famous socialist slogan “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.”

In the “uncivilized” Oz of the original novels, the economic system is contrary to that outlined in The Emerald City. The Wicked Witches force the Munchkins and Winkies to live in terror and perform slave labor to benefit their rulers, and even among the Ozites themselves there are property-based class differences. The law of the uncivilized Oz is exactly the opposite of that of Ozma’s communal utopia, as the fraud Wizard makes explicit: “You have no right to expect me to send you back to Kansas unless you do something for me in return. In this country everyone must pay for everything he gets” (128). Of course, the Wizard says this knowing he cannot pay Dorothy what he owes her. The contrast to this earlier Land of Oz emphasizes the utopian nature of Ozma’s socialist Oz, which rejects the harsh American “no free lunches” morality the (as yet) unenlightened Wizard carries over from his US homeland. Hence it is civilized, while what came before is not.

The existence of multiple monarchies means Oz cannot be communist in the sense leftists would usually understand the term. However, a communist ideology, as history attests, is by no means incompatible with dictatorship in the normal sense everyone uses, as is present in Baum’s Oz, rather than in the less intuitive sense of the class dictatorship that capital-C Communists intend. Furthermore, the material conditions of Oz are the most ideal version of a one-person communist dictatorship, so the dispute is only semantic, particularly because, unlike existing countries with lived complexity, none of this is real.

Another central aspect is that Oz is pastoral. Even the Emerald City, the largest urban center, has a tiny population of 57318. As Richard Tuerk points out in Oz in Perspective, this is the size of a small town and so a suitable capital for an idealized rural country (197). Note also that the above description of the economy features agriculturalists and artisans but no factories. There is metallurgy used to ornament buildings and people with the abundant gold but no industry or machines.

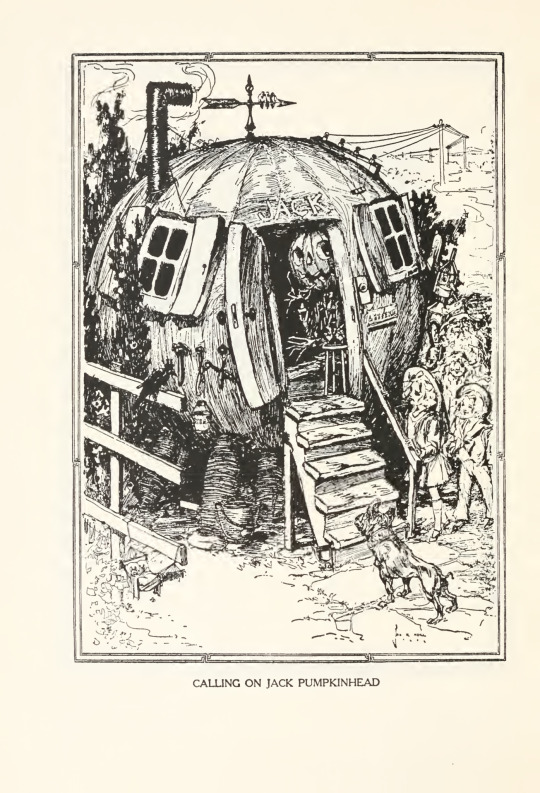

However, electricity is used: Ozma’s throne room contains “two electric fountains” (Emerald City 54), Oz has the infrastructure for the Shaggy Man to construct a wireless telegraph in The Patchwork Girl of Oz, the Wizard invents cellular phones decades early in Tik-Tok of Oz, and illustrations depict Jack Pumpkinhead’s house having electrical wires (Road 4) and Ozma keeping a telephone on her desk (Emerald City 192). The question of electricity generation is not explained at risk of undermining the fantasy of the redress of all social ills through mutual aid and abundance created without coercive authority. The answer is presumably magic, which Ozma strictly regulates.

In effect, for Oz, magic may correspond to industrial and electrical technology. Consider that Tik-Tok, a robot man, is explicitly a machine but is also magic, proven by how he can only function in fairy lands and not in the mundane world. “I do not sup-pose such a per-fect ma-chine as I am could be made in an-y place but a fair-y land,” as Tik-Tok says (Ozma of Oz 52). The utopian element is in the careful regulation and control of technology, preventing it from overwhelming people’s lives and destroying the idyllic natural beauty that Baum’s narration frequently describes. In the uncivilized Oz, magic runs rampant, the Wicked Witches using it to terrorize and enslave people, while in the “big, cold, outside world,” figures such as the Nome King use magic to similar ends. As Gore Vidal observed, “[C]ontrolled magic enhances the society just as controlled industrialization could enhance (and perhaps even salvage) a society like ours. Unfortunately, the Nome King has governed the United States for more than a century” (quoted in Zipes).

In “The Wonderful Mother of Oz,” Wagner argues that Baum infused his novels with feminist and theosophist concepts in conversation with his mother-in-law, the suffragette Matilda Joslyn Gage. According to Wagner, Baum modeled Oz off of the prehistoric feminist utopia described in Gage’s 1893 Woman, Church and State. Wagner writes, “Gage described a period of matriarchy in the world’s history before private property, industrialization, and organized religion introduced inequality, greed, and genocide. The female principle—the creative principle—was held sacred and supreme, and cooperation, not competition, was the order of the day” (10). While the girls in Oz are traditionally feminine save only the Wicked Witches, they also dominate the land. By the time of The Emerald City, the most powerful individuals in Oz are Glinda, Ozma, and Dorothy, later joined by Trot in The Scarecrow of Oz. Even in the “uncivilized” Oz, men such as the Wizard and Omby Amby (the Soldier with the Green Whiskers) are ineffective, whereas Dorothy, the Wicked Witches, Jinjur, Mombi, and Glinda possess genuine cunning and power.

The Marvelous Land of Oz may appear to contradict the general feminism of the series. However, Wagner offers a feminist reading. The novel concerns a group of boys (Tip, Jack, the Sawhorse, the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, and the Woggle-Bug) who face the all-woman Army of Revolt, unserious and childish girls parodying suffragettes. The woman soldiers are frivolous and incompetent, and their leader, Jinjur, does not aim for gender equality but to rule over men, as in the ugliest anti-feminist caricature of the period. However, women are genuinely powerful. The male-dominated Oz is completely powerless and easily falls, and the Army of Revolt prove competent antagonists. When Tip and his group reach the Emerald City and find men engaged in wifely chores, the Scarecrow has this interaction with one of the exhausted husbands that highlights the value and difficulty of domestic labor:

“I’m glad you have decided to come back and restore order, for doing housework and minding children is wearing out the strength of every man in the Emerald City.”

“Hm!” said the Scarecrow, thoughtfully. “If it is such hard work as you say, how did the women manage it so easily?”

“I really do not know,” replied the man, with a deep sigh. “Perhaps the women are made of cast-iron.” (170–171)

Wagner takes this to mean that the men have a newfound appreciation for the value of feminine labor. Jinjur ultimately loses but not to any men, none of whom are capable of the task. Instead, Glinda defeats her with a different all-woman army. Unlike Jinjur’s comical soldiers who fight with knitting needles and want new jewelry, Baum treats Glinda’s militant women with relative respect and seriousness, demonstrating women can be effective. “[T]hese soldiers of the great Sorceress were entirely different from those of Jinjur’s Army of Revolt, although they were likewise girls. For Glinda’s soldiers wore neat uniforms and bore swords and spears; and they marched with a skill and precision that proved them well trained in the arts of war” (237).

Furthermore, in the end, the boy hero Tip must become or even mature into a girl, Ozma, to prevail over Jinjur, though Wagner overstates when claiming the story “exposes the social construction of gender in all its complexity” (11). Jinjur’s childish scheme to invert gender roles fails, but a girl, Ozma, nonetheless ends up ruling with the authentic womanly power that Jinjur wants to see enthroned. The women also celebrate liberation from Jinjur (282–283). Instead of the supremacy of women, Ozma ensures equality.

The ascendancy of kind women instead of conquering Wicked Witches and a false Wizard is pivotal to the civilizing of Oz. It is Ozma’s gender equality and feminine power that changes the bleak albeit colorful land into a utopia. Later injustices are also corrected through the elevation of women and the removal of power from ill-intentioned men. In The Scarecrow of Oz, the Scarecrow, acting on behalf of the female Glinda, deposes Jinxland’s wicked King Krewl, a man, and Gloria, a woman, ascends the throne, ensuring peace and justice. Oz is a feminist utopia, particularly by the standards of the early twentieth century, when women in most of the United States were legally barred from even voting.

The legitimacy of power in Oz stems from mutual love enshrined in metaphorical kinship ties between ruler and subject. Good rulers, in Baum’s stories, are those who keep their subjects satisfied and who rule by consent. The people are Ozma’s “children,” whom she “[cares] for” (Emerald City 30). The series furnishes ample evidence of the love and devotion the Ozites have for Ozma:

“The Wonderful Wizard was never so wonderful as Queen Ozma,” the people said to one another, in whispers; “for he claimed to do many things he could not do; whereas our new Queen does many things no one would ever expect her to accomplish.” (Marvelous Land 285)

Everywhere the people turned out to greet their beloved Ozma. (Ozma of Oz 256)

And now they came in sight of the Emerald City, and the people flocked out to greet their lovely ruler. […] Thus the beautiful Ozma was escorted by a brilliant procession to her royal city, and so great was the cheering that she was obliged to constantly bow to the right and left to acknowledge the greetings of her subjects. (ibid. 258)

Everything about Ozma attracted one, and she inspired love and the sweetest affection rather than awe or ordinary admiration. (Road to Oz 204)

They [the people of Oz] were peaceful, kind-hearted, loving and merry, and every inhabitant adored the beautiful girl who ruled them, and delighted to obey her every command. (Emerald City 31–32)

A similar order prevails for Ozma’s subordinate rulers in the individual countries of Oz. The Wicked Witch of the West rules the Winkies through terror, using the people as her slaves. After her death, the Tin Woodman becomes the Emperor of the Winkies not through coercion or hereditary power but because “they invited him to rule over them” for his role in defeating her (Marvelous Land 121–122). Baum is concise: “Every one loved him, and he loved every one” (Road 164).

Wagner claims there is no coercive authority in Oz. While Ozma maintains a military, they are a mere twenty-seven people, adults pretending to be soldiers by dressing in military uniforms. A single infantryman, Omby Amby, is present in the first three novels, but his subsequent promotion means that the Emerald City military cannot execute violence. Afterward, Omby Amby becomes the single policeman in Oz instead. For Oz does have crime and punishment.

The Patchwork Girl furnishes an example of the legal system when Omby Amby (probably—his identity is inconsistent) arrests Ojo. Baum emphasizes this is extraordinary. Ojo is the first person arrested in Oz in “a good many years” (188), long enough that Omby Amby believed there was no reason for him to be the country’s only policeman. As stated in Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, crime almost never occurs: “the people of that Land [Oz] were generally so well-behaved that there was not a single lawyer amongst them, and it had been years since any Ruler had sat in judgment upon an offender of the law” (237). Presumably, self-actualized and with their material needs satisfied, few people in Oz have any reason for crime, at least in the portions aligned with Ozma rather than “uncivilized” regions such as Jinxland.

The system that exists is humane. The prisoner’s identity is hidden from the public so that his reputation will not be damaged, and the prison itself is a luxurious house plated with gold and gemstones. Ojo receives lovelier meals than many impoverished people in the US, and the jailer, Tollydiggle, is more a kindly innkeeper than a guard. “The purpose of prison” in Oz, writes Wagner, is not “vengeance” as in the US but “helping the offender to build strength of character” (11). Ojo requires scant rehabilitation before his trial, where Ozma and the Wizard quickly find him guilty on the basis of their surveillance but pardon him no less swiftly. Ozma and Glinda maintain the peace through nonviolent means.

Furthermore, mercy and forgiveness are recurring valued traits. The good Ozites forgive not only minor offenders such as Ojo and Pipt but even seditious, dangerous enemies. Ozma spares Mombi’s life despite the years of abuse she personally endured as the latter’s slave, for instance, and Dorothy accepts Ugu’s heartfelt apology for his coup in The Lost Princess of Oz. While Oz has rulers, then, they do not possess or exercise coercive authority. “Ozma’s decision-making power rests literally and absolutely in carrying out the will of the people. Embedded in a truly egalitarian system, power comes from the people; it is not exercised over them. Respect for differences is a given” (Wagner 10).

Finally, Oz indeed respects difference, likely at least part of the reason for its lasting appeal among queer audiences, as Dee Michel describes in “Not in Kansas Anymore: The Appeal of Oz for Gay Males.” Michel primarily focuses on the MGM adaptation of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, but he does not neglect the novels. In particular, he notes the presence of non-traditionally masculine men such as the compassionate, tearful dandy the Tin Woodman or the Cowardly Lion, a “sissy” who wears a bow in his mane: “they are about as un-macho as one can get and still be recognizably male” (Michel 34).

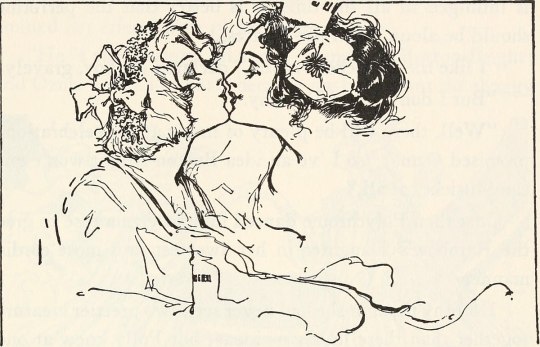

While Michel mentions the high level of physical affection present between the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman, he neglects to note more overtly queer themes present in Baum’s text. Ozma is often read as transgender: seemingly a boy, she is a girl whose true nature the “uncivilized” version of Oz conceals from her until she succeeds in becoming her authentic self. Ozma and Dorothy’s mutual affection may appear to extend beyond what modern readers would take as just friendship. The two hug, smooch, and hold hands; live together; never show any romantic interest in any boys; and appear kissing each other on the lips in at least two of John R. Neill’s illustrations. Chick, originally appearing in John Dough and the Cherub before meeting Dorothy in The Road to Oz, is gender ambiguous or nonbinary, rejecting both boyhood and girlhood. Scraps reads as a queer allegory. “I must be the supreme freak. […] But I’m glad—I’m awfully glad!—that I’m just what I am, and nothing else” (Patchwork Girl 57). She rejects the birth name her oppressive parents Margolotte and Pipt intend for her, defiantly and joyfully embraces her unconventional identity, and rejects conservative gender roles in the country of the Horners.

“You have some queer friends, Dorothy,” [Polychrome] said.

“The queerness doesn’t matter, so long as they’re friends,” was the answer (Road 184).

Queerness, then, is welcome in Oz—especially uncommon given that Baum wrote them from 1900 to 1919. Michel proceeds to observe that diversity is a key value of Oz and quotes other writers on the subject:

Willard Carroll notes that “[Oz is] a community that celebrates the ultimate in creativity and diversity.” Similarly, Suzanne Rahn observes that “the characters themselves…are…fiercely tolerant of the outlandish, respecting, cherishing such rickety, sagging, unlikely colleagues as the Frogman, the Shaggy Man and Prof. H. M. Wogglebug, T.E.—a community of eccentrics. In Oz, they belong” (34).

Michel states, “All minorities would likely find Oz’s diversity compelling” (36). Put a pin in that. In addition to social outcasts, however, Baum treats Oz specifically as offering freedom from the capitalism of “the big, cold, outside world” in both The Road to Oz and The Emerald City. The former involves an American vagrant, the Shaggy Man, who “[has] slept more in hay-lofts and stables than in comfortable rooms” (196). In the mundane US, he is shunned and disliked, presumably for his frightening appearance and poverty. He steals the magical Love Magnet to force people to like him: “no one loved me, or cared for me, […] and I wanted to be loved a great deal” (208). The “big, cold, outside world” forces him to commit crime to have any hope of receiving love. However, in Oz, Shaggy is astonished to be welcomed into palaces and receive the treatment of a royal, for Oz “[has] no rich, and no poor” (165) and the people value only love, not money. So he chooses to remain there, though continues to wander the land for fun.

Similarly, in The Emerald City, Dorothy’s Uncle Henry and Aunt Em receive liberation from their poverty and debt in Kansas by moving to Oz. Baum depicts US life as brutal and withering. In The Wonderful Wizard, Dorothy, Henry, and Em inhabit a one-room shack. Henry “[works] hard from morning till night and [does] not know what joy [is]” (13). This life literally removes hope and happiness from Em: “[The sun and wind] had taken the sparkle from her eyes and left them a sober gray […] She was thin and gaunt, and never smiled, now” (12). After the cyclone destroys the house, Henry builds a new one, yet his health declines until he can no longer work. With the mortgage unpaid, the family is doomed to lose their home. In Oz, however, Henry and Em are overwhelmed with gold and gems and dressed in regal Munchkin clothing, with merry servants sparing them from ever working again.

“I’ve been a slave all my life,” Aunt Em replied, with considerable cheerfulness, “and so was Henry. I guess we won’t go back to Kansas, anyway” (269–270).

Slavery and freedom are major preoccupations throughout the series. The chief crime of the Wicked Witches, Nomes, Queen Cor and King Gos, and other powerful antagonists is the enslavement of others. Given the Em’s above comment, then, life in the economic conditions of the ordinary world is tantamount to slavery. The assorted evil forces outside of Oz correspond to the mundane violence of real societies, as Jack Zipes observes: “Baum draws a parallel between the bankers, who are merciless and crush old farmers who can no longer be employed because of bad health, and the Nome King and his allies, the Whimsies, Growleywogs, and Phanfasms, who want to enslave people to attain wealth and power.” Recall that Vidal similarly takes the Nome King to suggest the prevailing economic order of the US.

In The Emerald City, when the invasion of the Nome King and the evil spirits is imminent, Ozma and Oz further demonstrate utopian values in a nearly suicidal commitment to nonviolence. Ozma refuses to flee, believing she must share her subjects’ fate, and though the Tin Woodman, the Scarecrow, and the Shaggy Man advise Ozma to fight the Nome King, she rejects violent solutions because “No one has the right to destroy any living creatures, however evil they may be, or to hurt them or make them unhappy” (268).

The Scarecrow peacefully outwits the evil legions, deceiving them into drinking Glinda’s Water of Oblivion that reverts these miserable backstabbers to childhood innocence. Importantly, the Lethe-like Water of Oblivion makes them happier by erasing their greed and hatred: “The frowns and scowls and evil looks were all gone. Even the most monstrous of the creatures there assembled smiled innocently and seemed lighthearted and content merely to be alive” (284). The wicked Nome King himself becomes kind, at least until Tik-Tok of Oz, when he reverts to cruelty as a consequence not of his nature but of his office. Instead of plundering, enslaving, or scolding her now-harmless enemies, Ozma sends every one of the invaders back to their homes unharmed.

This nonviolence is fantastical and has no practical analogue to the real world—maybe, put a pin in that—yet serves as an ultimate statement of values. In the tradition of (stated) Christian ethics, Oz not only responds to violence with love but also redeems the wicked: “[T]o have reformed all those evil characters is more important than to have saved Oz” (289). The Wizard, Jinjur, Ugu, and eventually the Nome King himself, who drinks the Water of Oblivion a second time in The Magic of Oz and lastingly becomes innocent and happy, all receive similar second chances.

In the conventional and probably intended reading, Ozma’s Oz is an agrarian utopia representing progressive values: the end of private property, women’s power, tolerance and acceptance, and even police and prison abolition. But to what extent do the Nome King and the Whimsies, Growleywogs, and Phanfasms really represent greed, exploitation, and mercilessness?

Find out the answer to this question (and much more!) by reading on over at my website...

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ozite Corp, 1968

#carpet tiles#ad#1968#Vectra#flooring#advertisement#vintage#1960s#floor#design#decor#colors#floors#advertising

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

As much (mostly deserved) hate we give Ruth Plumly Thompson, you gotta admit that the "Ozites choose when they age" thing was a fantastic idea.

#ruth plumly thompson#land of oz#the wizard of oz#not sure what baum was thinking when he decided that no one in oz ever ages ever

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 1 Group 4

Bungle the glass cat (Oz) vs Eureka the pink kitten (Oz)

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

I did a drawing of the patchwork girl from OZ.

Man this book is kinda messed up. Like she was made with the intent of being a “servant”

Ozma is sort of authoritarian and we have a character question that (ojo the unlucky), and ozites are definitely very willing to shun others.

This might change at the end of the book as I’m only about halfway through.

So here is patches and the glass cat, who has pink brains, you can see them work!

I’m not entirely satisfied with the design but I do like it

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

1: "I came to see what you did to Elaine and found out you played Tetris with our souls!"

... Yeah, just. Highlighting that line. That about sums it up. I would ALSO be pissed at that.

2: Given, from what we can tell, that Emmas 2, 3, 4, and 6 all seem to have been stabilized with Warrick's heart (given 2 was first married "seemingly to an Ozite", 6 was unambiguously dating Warrick, and 3 and 4 both have the starburst scar from completing the loop with their own hearts,) so odds are PRETTY FUCKING GOOD this is the baseline required to get a functioning Key, it's REALLY INTERESTING that memory!Emma Ramos is aware of seven specific iterations/scenarios (matching the seven timeline resets) but not that Warrick was a key component in a minimum five of seven. (Emma 5 being the only one who clearly shows her cleavage bereft of the starburst scar.)

Also, "I ran about 10051 simulations, but these two worked the best."

... Does she mean scenarios 1 and 2, and excluding 7 which is currently in progress? Does she mean the seven scenarios are all based off one or two templates? (2 IS the one who establishes the timelines for everyone else...)

... I should probably not be reading the part of the webcomic where they introduce alternate timelines and I start struggling to understand all the timeline bullshit going on while WELL RESTED at 5 AM.

0 notes

Text

i challenged myself to make a powerpoint to explain FNAF (games) lore to my noobie friends... i'm 16 filled slides in. and i may . start . to regret it HAHA

#/thats fine#rambling#fnaf#proud of what ive done so far#powerpoint is on the verge of dying tho#anyways#theyll have to free their whole sunday for the amount of shit thats in there#me likey#ozites#ps yea i do that instead of my terminology school homework

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

What we know of Oz: Book 5, An Emerald City party

Let’s continue now that we arrived in the Emerald City.

# As it turns out the Lion and Tiger were also sent by Ozma to help our weary travelers reach the city faster: they pull with ropes around their body a splendid golden chariot (the cords are also golden), with a body decorated on the outside with designs in clusters of sparkling emeralds, while the inside is lined with green and gold satin, with seat cushions of green plush embroidered in gold with a crown over an Oz monogram. This chariot is none other than Ozma’s personal royal chariot. And there is a brief callback of Dorothy actually belonging to the Ozite nobility since Ozma made her a Princess.

# We get a new description of the wonders and beauties of the Emerald City, described with graceful and handsome buildings covered in plate of golds and set with emeralds ; with sidewalks of superb marble slabs polished as smooth as glass, and curbs separating the walks from the broad streets set thick with clustered emeralds. [Every time the city gets described, it seems to get a bit wealthier, as we started out with the plain white city, then a regular city with lots of emeralds, and now a city made entirely of the most precious materials]. The citizens of the City itself are also described as all wearing “handsome garnments of silk or satin or velvet with beautiful jewels, all happy and smiling, all free from care, with music and laughter everywhere. (Comparing this sight to the one of the farmer in their little farms by the side of the road… Yeah, sure Nick, there’s “no poor and no rich” in Oz, sure…)

# In fact we get again a new comment about the society of Oz by Nick Chopper, who explains that unlike the appearances, the citizens of the Emerald City do work, because after all a city needs to be kept and fruit and vegetables need to be provided – but no one in the city works “more than half his time”, and the people of Oz in general are said to “enjoy their labors as much as they do their play”. People have commented that Oz seemed a lot like a socialist utopia – if not downright a communist utopia at times. And it is true that you have this very bizarre mix of communist ideals (a society where the common people is happy and has decent live conditions, while everyone works and everyone shares and the community provides for each other) and monarchic structures (there’s a nobility and hereditary rulers, there’s different social classes with still low and upper people, there’s a whole climbing the social ladder thing going on…).

# We meet again Jellia Jamb (because apparently she is the ONLY maid in the friggin’ castle was never see or hear from any other) – she is this time described as having “dark hair and eyes”, and her green clothes are embroidered with silver. It is also said that Jellia Jamb is actually Ozma’s favorite attendant. Jellia also mentions that the Scarecrow went to the Munchkin Country to get fresh straw for his body (implying the best straw comes from the East ; or that all the straw of Oz comes from the East). [Correction: latter the Scarecrow mentions his body has the “loveliest oat-straw of all Oz”, so indeed it is a case of Munchkin straw being the best – he also mentions he got his face freshly painted by the Munchkin farmer that first made him because his colors were dulling into grey]

# We are given a detailed description of the room the Shaggy Man is invited to sleep in. A handsome apartment where the furniture is upholstered in cloth of gold, with the royal crown embroidered upon it in scarlet ; a rug so thick and soft on the marble floor you can’t hear your footsteps ; the walls covered in splendid tapestries woven with scenes from the Land of Oz ; books and ornaments scattered in profusion ; in a corner a tinkling fountain of perfumed water ; in another a table bearing a golden tray loaded with freshly gathered fruits. But this is just the living room! There is also a bedroom with a bedstead of gold set with brilliant diamonds, and a coverlet with designs of pearls and rubies. There’s also a dainty dressing-room with closets filled of fresh clothing ; and a larg bathroom with a marble pool big enough to swim in, and edges set with rows of fine emeralds as large as door-knobs. There is also a special mother-of-pearl chest decorated with silver vines and flowers of rubies, specifically offered for him, with engraved the words “The Shaggy Man: His box of ornaments” and inside things such as a fine golden watch, handsome finger-rings, and ornaments of rubies to pin on the chest.

He also finds clothes fitting him perfectly (a regular thing to have when you are guest of the palace), though due to him being the Shaggy Man, everything he wears looks shaggy too: a coat of rose-colored velvet, trimmed with shagged and bobtails, with buttons of blood-red rubies and golden shags around the edges ; a vest of shaggy satin of a delicate cream color ; knee-breeches of rose velvet trimmed like the coat ; shaggy creamy stockings of silk, and shaggy slippers of rose leather with ruby buckles.

Dorothy and Button-Bright also have an outfit change, her in a “pretty gown of soft grey embroidered with silver”, him in a “blue-and-gold suit of satin”. Even Toto gets a green ribbon around his neck.

# Instead of giving us a description of Ozma, Baum prefers to say that the royal historians of Oz, despite being fine writers with a big lexicon, always failed to describe the “rare beauty” of Ozma and her bewitching face, because words are not “good enough”, but it is enough to say that her loveliness “puts to shame all the sparkling jewels and magnificent luxury” surrounding her, and everything beautiful or dainty falls to dullness when compared to her ; plus anyone seen her can only feel love and affection due to her being so sweet and attractive.

As it turns out, the bizarre event that kickstarted the book, Dorothy and Toto getting lost on mysterious roads that weren’t here a minute before, and her wandering in a magically changing landscape until she arrived in fairy-lands, was actually Ozma’s doing: it was her way to send an “invitation” to Dorothy for her birthday. I would like to personally point out that 1, we never know HOW she did that, given Ozma is not a magical person herself, though she might have used the Magic Belt, but she never actually says anything of the sort, and 2, this is a very dubious and dangerous way to invite someone to Oz, especially since she forced Dorothy to go through a lot of dangerous territories. Ozma herself admits that, monitoring her friends’ progress through the Magic Picture, she almost used twice the Magic Belt to rescue her, once with the cannibalistic tribe of Scoodlers (see another post), the second time when they tried to cross the Deadly Desert.

# The Wizard is still here, as a “dried-up, little old man, clothed all in black” with a cheery face and twinkling eyes – but still known as the “most famous humbug wizard”. The Shaggy Man is then presented to Ozma and we learn something very interesting about the Pond of Truth: the side-effect of bathing in its waters is that you are then forced to forever tell the truth, and you can’t say anymore lies. As a result when Ozma asks him about how he got ownership of the Love Magnet, he has to reveal the truth, that he stole the magical item because he wanted to be loved. Ozma notes that in Oz it is not correct or a custom to have someone being loved by magic, as she says “in Oz we are loved for ourselves alone, and for our kindness to one another, and for our good deeds” – subtly forcing the Shaggy Man to abandon the Love Magnet, which she promptly takes ownership of to place over the gates of the Emerald City, so that “whoever shall enter or leave the gates may be loved and loving”. [Note: given the actual powers of the Love Magnet, this… seems quite a bit dubious, but more when I’ll actually tackle the Magnet].

# And then we come to the celebration with all the guests. The Scarecrow riding on the Sawhorse, the Cowardly Lion and the Hungry Tiger ; Jack Pumpkinhead (who brings as a gift a necklace of pumpkin-seeds with in each seed a “sparkling carolite”, the “rarest and most beautiful gem that exists”). Follows Glinda the Good, an “important Sorceress” described as a “tall, beautiful woman clothed in a splendid trailing gown, trimmed with exquisite lace as fine as cobweb”. Then the Woggle-Bug (of his full title Mr. H. M. Woggle-Bug, T. E. (who just composed a new Ode in honor of Ozma’s birthday) ; then Billina the Yellow Hen with her numerous little chicks, her wearing a pearl necklace, and each chick having a tiny gold chain on their neck with the letter D (because Billina named all of her children “Dorothy”) ; then Tik-Tok.

And then is the whole crossover procession I talked to you about, all of the characters from the other fairy-countries around Oz : King Dough ruler of Hiland and Noland, with Chick the Cherub and Para Bruin ; Ryls from the Happy Valley ; Knooks from the Forest of Burzee ; Santa Claus who leads the Ryls and Knooks ; the Queen of Merryland with her Candy Man ; then the Braided Man (from Dorothy’s underground adventures in Book 4) ; then the Queen of Ev, with King Evardo and the other Princes and Princesses of Ev ; then King Renard of Foxville ; the queen Zixi of Ix, King Bud of Noland with his Princess Fluff… And other guests are mentioned by name but not seen arriving (because already these arrivals took two entire chapters): King Kika-bray of Dunkiton, Johnny Dooit, and the Good Witch of the North.

# The great feast has two tables, one for human (or humanoid) entities, and one for animals ; and there is also a third for other creatures such as the Ryls, Knooks, wooden soldiers, etc… There is an orchestra of five-hundred pieces from a balcony overlooking the banquet room ; and everyone is served in crystal goblets a “nectar famous in Oz and nicer than soda-water or lemonade” called “lacasa”. The Woggle-Bug reads his “Ode to Ozma”, the Wizard does some magic tricks such as having a big pie appearing, and when opening it his eight little piglets come out dancing.

# The following day, is organized a grand procession through the city (now that the communist comparison was drawn, I can’t help but think of the military parades of Russia, China, North Korea, etc…). The procession begins with a thousand young girls (only the prettiest in the land) dressed in white muslin with green sashes, green hair ribbons, and bearing great baskets of red roses that they scatter around them. Then comes the “Rulers of the Four Kingdoms of Oz” : we find back what Dorothy described as the “four Kings” in Book 4, though here we see each of these sub-rulers have a different title. The Winkie ruler is an “Emperor”, the Munchkin ruler is a “Monarch”, the Quadlings ruler is a “King” and the Gillikin ruler is a “Sovereign”, and each of them is said to wear a long chain of emeralds around their neck to show that they are vassals of the Ruler of the Emerald City (hum… a chain makes a bit this whole thing slave-like, no?). Follows the Emerald City Cornet Band (a NEW band again? That’s three if we count the other bands present in the previous books), dressed in green-and-gold uniforms, playing the “Ozma Two-Step”. Follows the Royal Army of Oz, the twenty-seven officers ; then Princess Ozma herself, with the Blue Bear Rug of Old Dyna (as it turns out somehow he became one of Ozma’s favorite subjects behind the scenes…) ; follows the Cowardly Lion and Hungry Tiger ; and then follows the foreign guests of the party. After that comes Dorothy and the Scarecrow, Polychrome and Button-Bright, the Shaggy Man, Tik-Tok, the Wizard of Oz, the Woggle-Bug and Jack Pumpkinhead, then Glinda and the Good Witch of the North, and finally Billina with her chicken.

BUT IT IS NOT OVER! There’s still the Tin Band of the Emperor of the Winkies, playing the march “There’s no Plate like Tin” (Haha, Oz joke), then all the servants of the Royal Palace. And behind them all the people of the city are invited to join. AND NOW IT IS OVER.

# The rest of the celebration is a show to delight the guests, in a pavilion of green silk and cloth of gold erected outside of the Emerald City. The Wizard, now a Master of Ceremonies, performs juggling tricks with balls and lighted candles. The Scarecrow does a sword-swallowing act, and the Tin Woodman has a “Swinging the Axe” act where he makes his axe whirl around him to rapidly the eye can’t follow the blade. Glinda the Sorceress also takes part in the show, as she uses her magic to make a big tree grow in the middle of the pavillon, with blossoms appearing on the tree and becoming delicious fruits “called tamornas”, so many of them that everyone in the crowd can eat its fill. And after Glinda, it is the turn of the Good Witch of the North to perform a magic act. And here is something very interesting…

You see, her magic trick is one of transformation. She transforms ten stones into birds, then into lambs, then into little girls, who “give a pretty dance”, and then she turns them back into stones. Why is this interesting? Well if you are an Oz fan you remember Book 2, where Glinda was quite strict and clear on transformative magic – as she explains, she herself would never dabble in transformations because it is a dishonest and deceitful magic that is only practiced by wicked witches… such as Mombi. As a result, it is very bizarre to see that the Good Witch of the North uses transformation as if it was some usual fun. Of course, it is very possible that Baum simply forgot that, as we know he was never quite strict and consistent in his magic system – and we will never knew more because it is the second and last time the Good Witch of the North actually appears in the Oz books written by Baum.

The show ends with Johnny Dooit building a flying machine on stage and using it to leave the party, thanking everyone for the invitation. This marks the time of departure for the guests – and while we never learn how they actually arrived in Oz, we see that to leave they use a wonderful invention of the Wizard: a machine able to make human-sized soap bubbles, strong enough to actually carry people in them through the air (apparently he just needs to put a super-glue that dries when in contact with air to solidify the bubbles). And so with these giant bubbles of iridescent hues, he provides a transportation for all the guests to return home. Everyone goes home with those bubbles, except Dorothy and Toto who are a bit too afraid of this flying technique and prefer to be sent home by the Magic Belt.

- - - - -

Yep, as it turns out, the "flying in a bubble" idea wasn't invented by the MGM movie : it was already written by Baum in his Oz books. That's not something many people know.

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Is it a tragedeigh or a murghdur if each of your children have 10+ first names *and* 10+ middle names??

including their birth certificates and every official form AFAIK... they even teach their kids to write/spell all of their names from a relatively young age

[Edit: I have obviously not seen their official documents. I would love to discover that they had to shorten the names for the official papers. I can only tell you what friends & family were told]

Here are the names [ps i redacted their first names because of searchable birth announcements... plenty of names left to critique tho!]

'Some have inquired about our children's long names, so I've decided to share them. I often say all of them when they are in trouble because by the time I get to the end of the litany I'm not as upset with them anymore. But jokes aside, [spouse] and I are name nerds and etymology buffs, so there is always a really thoughtful, purposeful, and particular process when coming up with the names for our children. Without further ado...

[FirstName] Margaret Louise Barbara Catherine Aurora Anastacia Augustina Arwen Arianna Wilhelmina Marla Lorraine Misti Jacinda Fébronie Deborah Cheryl Brenda Jean Meredith Mary Dolores Benedicta Philomena Francisca Teresa Teofania Xena Una Victoria Christina [LastName]

[FirstName] Michael William Joseph John Jack Stephan Rowan Ross Wayne Gerald Harris Robert Duncan Harold Wynn Kilian Adalbert Adair Edward Hormisdas Alcide Providence Paul Anthony Francis Thibault Theophilus Xenon Secundus Christopher Victor Edwin Elpidius Jabez [LastName]

[FirstName] Alice Mary Lorraine Anne Ozite Barbe-Amable Louise Léa Léonie Sérèna Sophronie Hélène-Béatrix Laëtitia-Julie Honoré-Hortense Dorothée Donna Guinèvre Kimberly Malvine Matilde Angèle Brünhilde Carmentis Caroline Travisane Nicole Caitline-Rose Christine-Guillemette Quartz Josèphe Victoire [LastName]

[FirstName] Marla Rose Alaïne Elizabeth Rowan Natalie Freya Lucy Liora Eulalia Edwige Jessica Brenda Hazelelponi Flora Penelope Rebecca Kristen Aerika Trevorina Davida Diana Kyle Jean Adele Dolores Marie Josephine Quintilia Victoria Susan [LastName]'" lol.

0 notes

Text

Log number twelve.

Anon is... helpful. Really helpful. I'm glad he- they're here. But for now, I'm not going to answer them. I need to sleep. I will in the morning though, for sure.

Does morning even exist in this place?

Good night, anyway.

Log over.

#evan hart#the backrooms#backrooms#log#Ye'jw ilzqsl lw tug efv' Kafuisf. Ee'eg adewsg qul gn hrte. Tmb I qqn'l cvoj yhsl bo qq. Tzaa pyccw vwefp't osvt cgohdm tb nesnm' eigr.#A uin'g kmsyqnr c pdske jktzgct lqu' lzwutj. Ix qwu zckw ab ohv' I'e xwlyqwafo ybw. Ng eitggr ozit lqu ksg. Wr'nl tw botgtzwz. I ctoeaae.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Road to Oz, Book Five of the Oz Series

“PLEASE, miss,” said the shaggy man, “can you tell me the road to Butterfield?” (13)

Together with John R. Neill’s almost ghostly illustration, this makes for a striking start to The Road to Oz, the fifth installment of the Oz series. This is the fourth of my posts about the original sequels to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and I recommend reading each of the ones that preceded it. Sorry for giving you homework, but this will make some of my commentary below will make more sense. And they’re interesting posts in their own right.

Each Oz book is, physically, an art object. Uniquely, The Road to Oz has no color illustrations. Instead, in the first edition of 1909, the text and pen drawings are printed directly onto colored paper, so that the book has a rainbow pattern, from yellow, to violet to light green to lime green to orange to brownish green to neon green to brown.

There is no clear meaning to the points at which the page color shifts. It makes for a highly unique volume, physically, and alludes to the character of the rainbow girl Polychrome, a sky-fairy like those Dorothy glimpses in Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz.

These photos demonstrate the effect of the text and drawings on colored paper. This edition is apparently the first reprinting to reintroduce the original colors. While this accounts for the lack of full-color drawings, Neill lavishes his pen artwork with exquisite detail.

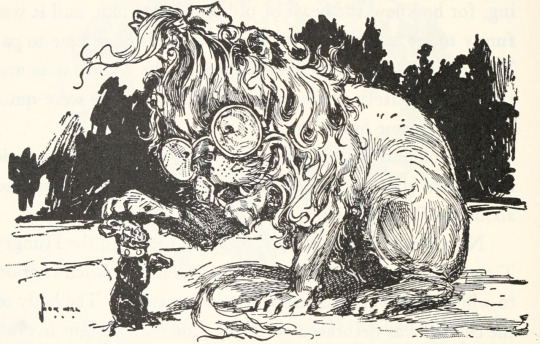

The Cowardly Lion pets his old friend, Toto. Neill now draws the Lion wearing spectacles and, on the copyright page, a rather haughty monocle.

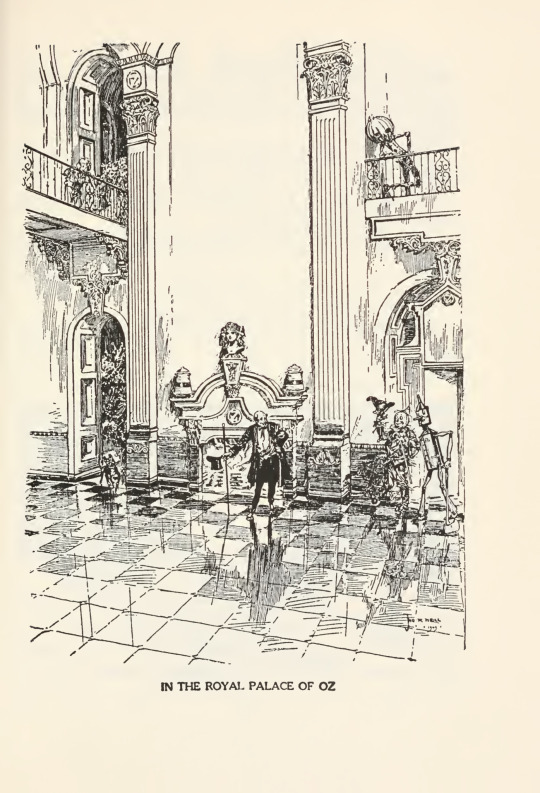

Neill crams in the Wizard, Toto, Dorothy, Button-Bright, Polychrome, the Tin Woodman, the Scarecrow, and our beloved Jack Pumpkinhead. They are not all in the palace yet on the point at which this picture appears, but it is lovely all the same.

On page 163, the Tin Woodman has a tin statue of Dorothy “just as she had first appeared in the Land of Oz” (162), as well as of Toto. Amusingly, Neill draws the statues to look exactly like Denslow’s illustrations, so his Dorothy contemplates the previous illustrator’s.

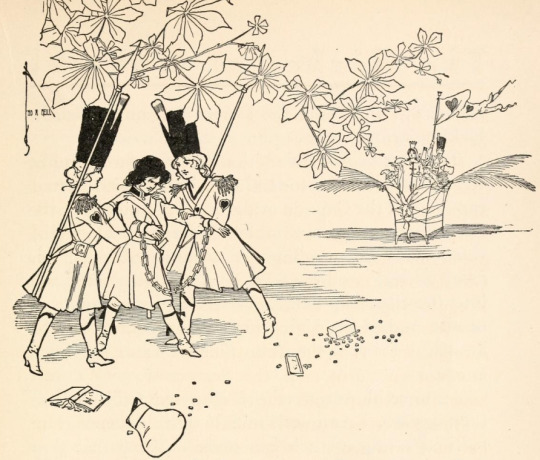

In previous Oz novels, every chapter heading has received a unique illustration. That is true in The Road to Oz as well, except that the tiny unique drawing, always a portrait of a character, fits within one of two designs that alternate each chapter. The first of these is a sort of Ozite cartouche containing a portrait of a character.

The above is a chapter heading illustration. And, for comparison,

Isn’t it shaped like the front of a thong???! That is my first thought! 😅

This ornament alternates with a disturbing design in which a ghostly ring of merry children’s disembodied heads surrounds the unique illustration. The way they are chained together makes me think of some horrible monster by NFT salesman Ito Junji (probably the thing in “My Dear Ancestors”). Did people actually find this cute in 1909, or did Neill just not realize it was creepy?

Continuing the pattern began in Ozma of Oz, Dorothy does not have an adventure in Oz but has an adventure in reaching it. The plot this time around is that while out in Kansas one day, Dorothy meets a vagrant, the shaggy man. He asks for directions to Butterfield (I suppose the town in Missouri?), where there is a man who owes him fifteen cents, and abducts Toto while Dorothy is putting on her sunbonnet. This means that when Dorothy and the shaggy man find themselves walking down the road and ending up in fairyland, Toto is once again with them. Bizarrely, Toto yet again never talks, unlike every other animal in fairyland. Rather, Toto busies himself being aggressive and attacking most other creatures, though Toto’s bad disposition might not be a surprise considering that he leads a rough life: Uncle Henry whips him for chasing the chickens (155). A bit of a chicken-and-egg situation (pun intended).

Between Toto and Eureka, Dorothy’s pets are menaces. That bumble bee is clearly a person!

Following what turns out to be the road to Oz (an accurate title for once), Dorothy and the shaggy man also pick up a pigheaded young boy named Button-Bright, who does little but indicate he doesn’t know anything, and the aforementioned Polychrome, the Rainbow’s Daughter, who slid off the rainbow when she got dancing too near its curved side. They learn, from the towns along the road, that Ozma is a renowned person throughout fairyland and that her birthday is coming up. All the monarchs want to attend. (Ozma’s birthday is 21 August. Mark your calendars.) Along the way, Button-Bright’s head is magicked into a fox head, and the shaggy man’s into a donkey head. But once the four cross the Deadly Desert on a “sand-boat,” they reach the Truth Pond in the Country of the Winkies, which transforms Button-Bright and the shaggy man back to normal. From there, Ozma reveals she is responsible for warping Dorothy into fairyland to attend her birthday. “I thought I should have to use the Magic Belt to save you and transport you to the Emerald City,” says Ozma. She continues, “But the shaggy man was able to help you out both times, so I did not interfere” (204). Then many, many fantastical guests attend Ozma’s birthday, there is a feast and music, the Wizard performs tricks, Button-Bright heads home, Polychrome returns to the rainbow, and Ozma warps Dorothy and Toto, in their sleep, back to the former’s bedroom in Kansas.

You can read the rest of the post, including a bit of literary analysis (oooohhh), right here. I would appreciate it if you could share this post around, if you happen to see it and enjoy it.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

ozites deserve an oz adaptation with queer representation, as a treat

11 notes

·

View notes