#or position the narrator was writing from especially with it being non-chronological

Text

i think subconsciously i always knew i didnt want to move to nyc though like The Fantasy is always appealing but reading the words 'trailer park-themed bar in chelsea' in this book solidified that further

#txt#it's a very good book fucking whirlwind of a read though#idk if having it being in first person made it better or worse#very much read as not a stream of consciousness it was much too intentional for that but it was very hard to discern from what timeframe#or position the narrator was writing from especially with it being non-chronological#like it doesnt read as recounting memories that connect in some way to the next one from a point in the narrator's future#the experiences are being lived through and the emotions described as something thats happening at the time of writing#which is something i always struggle with concerning first person point of view#along with undefined timelines like the scenes themselves as they are written are very short but comprised together they make up like#six months of a relationship and boom all of a sudden theyre not just fucking but theyre going through the 'i love you' and breakup stages#which i THINK is intentional considering the character's proclivity for those kinds of cycles#what i liked the most was the descriptions of the recovery center and the ones of childhood#but i dont want to shy away from the romantic relationships bc thats like (arguably) the messiest part of the character#if i have the capacity for it i'd like to look at the usage of time bc i really do think thats the most intriguing part of it#or maybe it's a genre marker that i just dont know about lol

0 notes

Note

YAY :D! OK, I wanted to please ask what your thoughts were on Dick and Shawn's relationship. Did you feel it was in character? Did you feel it made sense? Did you want them to last or did you feel it came out of left field and didn't make any sense? How did you feel about the pregnancy scare and how they broke up ("I know what I said/did was shitty but we can fix this. We can make this work!") - does it sound like Dick? I'm also happy ur still here. I'm so used to asking you & Shelly so thank u!

I'll be honest with you, anon--DC burnt me hard with the Spyral travesty and then putting Tom King on Batman and keeping Seeley on Nightwing, so I don't keep up with current DC comics. I don’t enjoy them and nearly without exception I don’t find them to be written well or in character. However, you're very sweet and I want to help fill the meta void in your life, so I read through Dick and Shawn's arc together and here's my analysis.

I’m dividing this into two parts. The first half will be as objective as possible and analyze your questions on whether Dick seems in character, what he says during the break up, etc. It’s roughly chronological, starting when we first meet Shawn and continuing through to the break up itself.

The second half I’ll put under a readmore, as it’ll answer your questions about my more subjective opinions about the arc.

Let’s start by looking at Dick’s previous and most happy relationships to see what good indicators for an in-character relationship would be.

Getting physically involved with someone -before- having a secure emotional connection with them is not in character for him. All of Dick's major relationships have been preceded by extended periods of mutual flirtation and bonding before physical overtures. His most significant and longest lasting romantic connections began by building emotional and romantic attachment before sexual intimacy, frequently paired with a shared history together that precedes even the flirtation.

There’s significant canon evidence that he’s demi sexual: a comprehensive, though hardly exhaustive, collection of it can be found here and here (the latter half of the second link relates to the Grayson series specifically, but overall it offers a nice long view on his relationship history since character creation and also addresses beyond-canon factors at DC that impacted some relevant canon writings.) Whether you use the label demi for him or not, it’s canon that he’s not comfortable jumping into bed without a secure emotional connection.

So let’s look at Shawn’s relationship with Dick through the lens of relationships in which he was the happiest and most comfortable. Those relationships have these things in common:

He has a stable, safe emotional connection to the individual.

He is willing and comfortable engaging in banter and flirtation.

Relationship is based on mutual respect and affection, often paired with shared history together.

Now, let’s look at Shawn’s relationship.

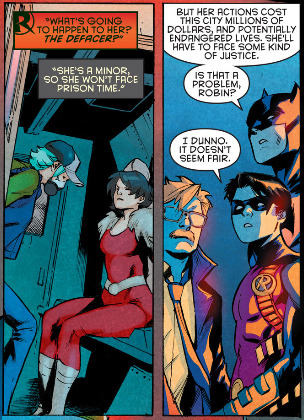

Their ‘history’ together (as Defacer and Robin) is antagonistic, and their interaction in the past leave Dick feeling uneasy. Sure, he seems to think about her situation, but as this panel reads, the kindest that can be said of any emotional connection there seems to be here is one-sided pity.

Nightwing #10 (Nightwing: Back to Bludhaven)

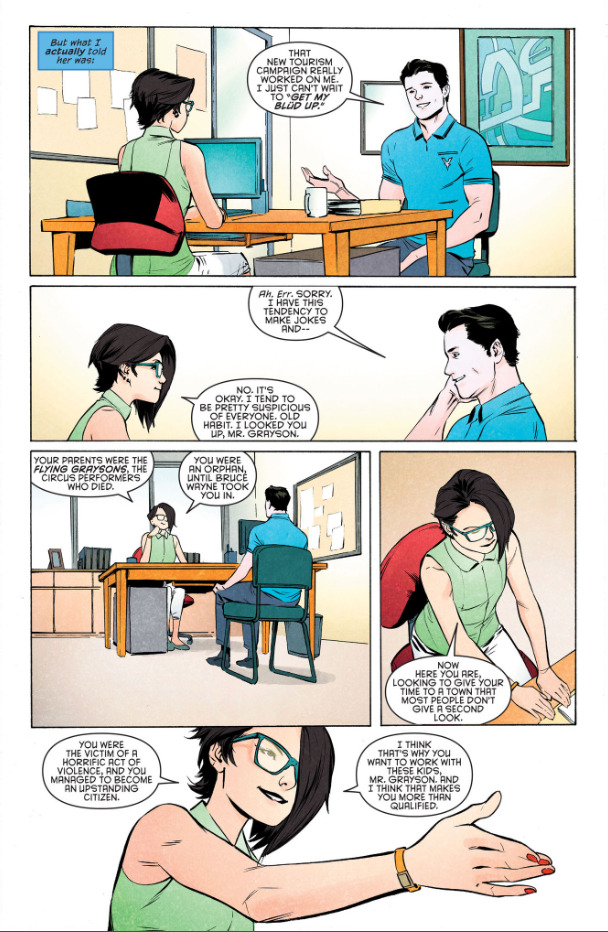

Once they meet again, she’s his boss. Even or perhaps especially in the world of #MeToo, it’s important to address workplace relationships, particularly boss/employee scenarios, with care and sensitivity. Seeley sidesteps this by just…having her later quit the non-profit she founded and giving Dick her position for a while. However, even if she’d just worked in HR at an equal level with him when they met instead of being his boss, let’s look at the amount of participation he shows in their first meeting:

Nightwing #10 (Nightwing: Back to Bludhaven)

There is a lot of her talking and almost none of him. He’s not engaged in their interaction here. Where he tries later as Nightwing to engage more personally, he’s immediately shut down. The most dialogue we hear from him is in his own head—in their first meeting, the ratio of her dialogue to his is literally 22 sentences to 9. Of those 9 sentences, one is a lie he gives to avoid establishing an emotional connection with her, another she interrupts, and three of which were less than five words long: “Sorry.” “You can call me Dick” and “Thanks, Ms Chang”. Even taking the workplace environment into account as best we can, this is not meeting any of the three criteria for Dick to be feeling emotionally attachment or attraction. No one would look at those 9 almost-sentences and that flashback and say, “Ah yes, this man is deeply infatuated with her.”

This is made even more jarring by the fact that the internal narration frequently doesn’t match the actual scenes we’ve witnessed.

Nightwing #11 (Nightwing: Back to Bludhaven)

Nothing about the few sentences Dick has managed to finish around Shawn when this narration comes up has said ‘attraction’, physical or otherwise, but the dialogue here reads like Dick was laying the flirtations on thick every time he saw her. Same with when they talk about the flashback scene later. There’s a lot of cognitive disconnect between what Seeley wants to tell us happened and what we actually see and hear and have evidence of between the characters.

If you’re wondering why I’m examining these initial interactions with particular depth, it is because frankly, these are the most interactions the two have together for roughly the first five issues of their ‘getting to know each other’ phase...and when they reunite at the end of those issues, we are supposed to believe they are already heavily, life-changingly in love. So, for all intents and purposes, this scattered handful of conversations is all we have to analyze to examine whether this fits the qualifications for whether Dick would feel comfortable and emotionally attached enough to approach a physical relationship.

We have three chances in their various guises for Dick and Shawn to meet and start developing that all-important rapport. This is our first initiation to their relationship and it certainly doesn’t read as a positive one. The next one, she yells at him and kicks him out—again, a whole page of her dialogue to a fragmented sentence of his. The third one, the flashback panel posted above, they don’t even speak to each other. Two of them are actively red-flags of being unable to establish a closer connection with that person; the third is a neutral connection. This is not the kind of two-way interaction we see where he’s comfortable and interested in someone, and this is not an emotionally secure connection.

Shawn disappears for three issues or so, during which they have, obviously, no interactions.

The very next after that, by the end of it, she lunges into him to kiss him.

The next issue after that, they’re evidently in honeymoon heaven and already shacking up.

Trust me, we’ll be going over that under the readmore later.

Back in the area of the objective, if you ever need to know the number of days Tim Seeley thinks is needed for two people with self-admitted enormous trust issues to form the ideal Hollywood manic pixie dream girl relationship, we were given a careful timeline.

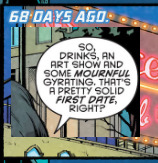

68 days—first date

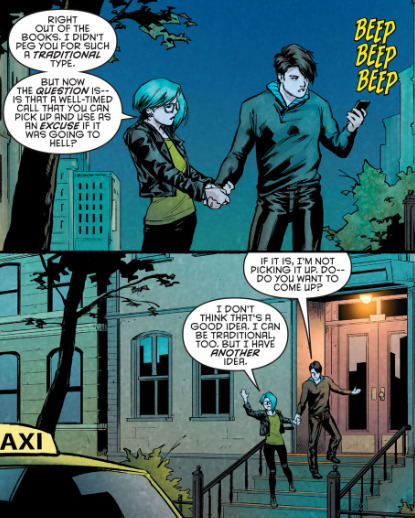

Nightwing #15 (Nightwing: Back to Bludhaven)

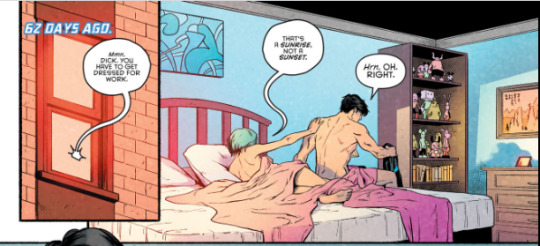

62 days—first intercourse.

Nightwing #15 (Nightwing: Back to Bludhaven)

Six days. Not even a week.

They’ve met each other, then met each other’s parents and are living together and are one baby scare away from the suburbs in less time than it takes for someone to finish a semester at college. It took literally longer for the issues of Nightwing where Shawn was an absent character in her own arc to get published in our real lives than it did for their on-panel romance to go from not even knowing each other to Nightwing (not Dick, but Nightwing) kissing Shawn (not Defacer, but Shawn) upside down in the middle of the city.

Trust issues, amirite?

Nightwing #15 (Nightwing: Back to Bludhaven)

Meanwhile during that mostly off-panel ‘dating’ period we have these wildly out of character moments. In particular, there are two noteworthy things.

Shawn says she never would have pinned Dick for being a traditionalist.

That directly contradicts…well…most of the statements people close to him have made of his dating views, and also his own self-stated views of them, whose top tracks include things like “…this might sound unhip, but I feel strange about living with someone I’m not married to”, “I gotta be honest, Roy—I couldn’t make love to someone I didn’t really love”, and “Love should be between two people”.

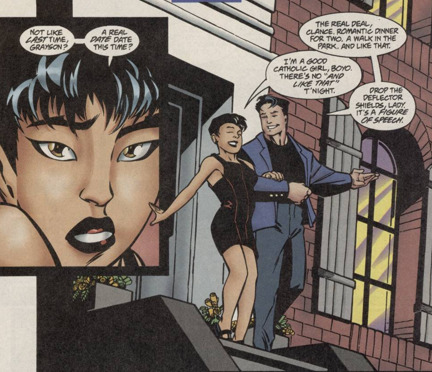

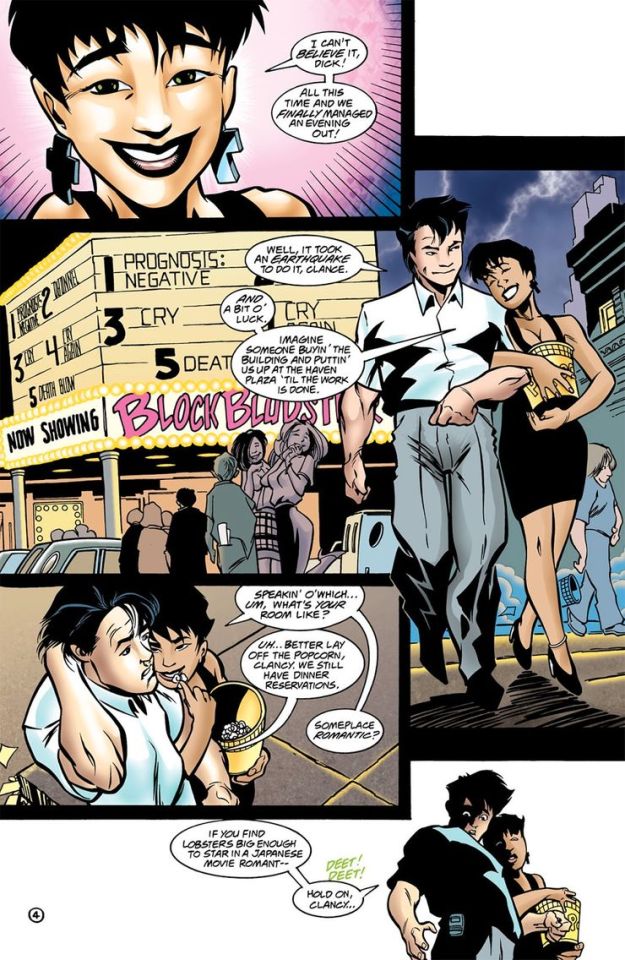

We have a direct parallel of an in-character Dick moment walking someone home after an early date to use for comparison.

Nightwing #31

Things Dick does in this panel: reassures his date there is no pressure for sex and the night will not be ending that way, plan out just about the most traditional date experience, and engage in light-hearted mutual bantering.

Additional relevant context around this panel: Dick and Clancy have known each other for months and have a friendly, mutually respectful connection. Dick’s turned down a sizable number of invitations from her because despite living in the same building, the vigilante life made it difficult for him to make and keep plans. This is their second date because Dick had to bail in the middle of their first. It took months both in comics-time and in real-time of developing a mutual interest to lead up to that first real date. And by then, the reader is invested in the status of that relationship, too.

To contrast the then vs now, we also have in that same moment with Shawn Dick, of all people, ignores a phone call without a second thought in favor of trying for a booty call. On the first date. Let’s take a look at Dick and Clancy’s first date, 9 issues earlier than the one we just saw.

Nightwing #22

Dick is a chronic workaholic, with all the associated inability to disconnect from his work while in relationships even during date night or intimate moments. It’s perfectly reasonable, considering that with his lifestyle choice, that phone call could be life or death for someone he loves, a stranger, or many, many someones, and it’s put significant strain on his past relationships when dating those not actively in the superhero lifestyle. Clancy is, again, a great example of this--despite genuine interest on both sides, he blew her off at least half a dozen times because of vigilante emergencies before they even got to their first date. And then despite their great rapport and a genuine interest in being there, he still ditched her in the middle of it when his phone rang.

What we see in Seeley’s Nightwing #15 not only runs directly contrary to significant chunks of his history and personality, it also tells a deeply upsetting story of a world where exists a horndog Dick Grayson who would risk other people’s lives to get laid with a chick he’s known less than a week.

They handle vigilante interruptions more in character in later issues once the relationship is established, but...yikes.

Not in character.

We’re going to take a little jump here to move from discussing whether their relationship is in character for Dick to whether their breakup was in character.

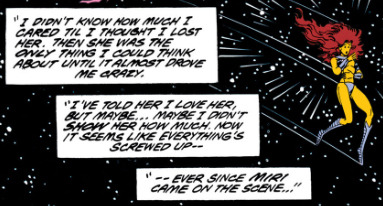

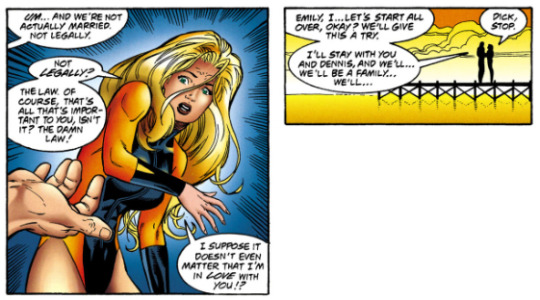

In general, it actually is pretty in character for Dick to panic himself into commitment in a romantic relationship even if he’s not really sure about it. Dick is very interesting that way: he runs away from platonic relationships under tension, either by throwing himself into casework or by literally setting up in a new location. If his romantic relationship is undergoing trauma, however, he's very capable of reacting the opposite, like in this example with Kory.

Team Titans #2

There’s even an awkward Devin Grayson incident where he thinks a woman is serial-murdering her husbands, fake-marries her to solve the case, uncovers the real killer who wasn’t her, and feels bad enough afterward that he offers to date her for real. (An interesting side-note: this makes Devin Grayson responsible for not one but two of Dick’s emotionally compromised almost-marriages. This one, at least, came before she jumped the shark with the dreaded Catalina Flores arc.)

Nightwing Annual #1

So let’s take a look at where Shawn’s exact circumstance falls in against those.

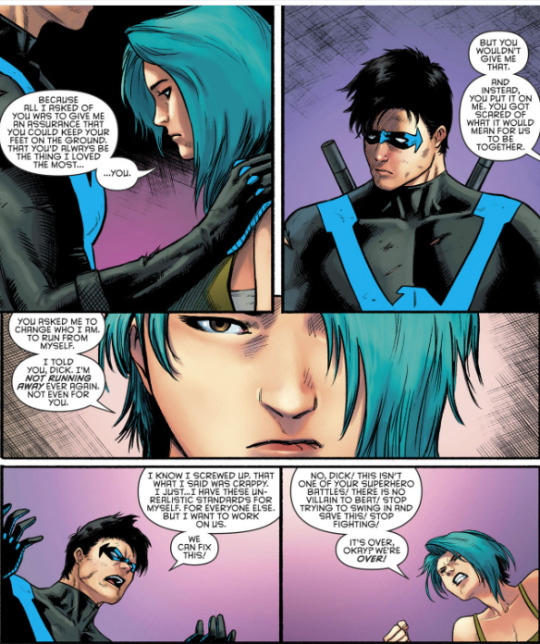

To me, the lines that sound the most like Dick are actually the lines he says that cause their break-up.

Nightwing #23 (Nightwing: Back to Bludhaven)

Dick has a lot of darkness and anger in him. He’s a lot like Bruce and he’s a lot scared of how much he’s like Bruce. We’ve seen several timelines where Dick’s had biological children and we’ve also seen how he tempered Damian’s darkness when Bruce was lost in the timestream. Though this arc and timeline does not show it well (and that’s a whole different meta), we have the advantage of having known how Dick behaves as a father in a way this particular Dick has never had to experience. And we know that when kids are in the picture he does work hard at repressing or concealing his anger and darkness to be a good role model, often in a way he isn’t sure he has the capacity to do when there are no children involved. Despite some of the specific phrasings being iffy, the general sentiments here do feel like legitimate concerns Dick would have.

With this knowledge, that moment felt significantly more honest to Dick Grayson’s character than most of the rest of their relationship.

Nightwing #25 (Nightwing: Back to Bludhaven)

The actual break-up dialogue itself is…well, it’s not out of character, exactly, because as shown, Dick has been known to clutch onto potential romances hardest when he feels they’re about to slip away. But the delivery of it isn’t in character. Yes, in general, Dick has a temper and he lashes out. However, he’s clearly aggressive and angry in this panel, where previous experience has showed us he should be at his most emotionally vulnerable and pleading. Dick, who is a generally emotionally closed-off person despite his extroverted demeanor, reacts to these kind of romance scares by showing emotional vulnerability in ways he frequently is unable to do during the relationship itself. And the panel that he’s apologizing for as being a crappy thing to have said, is…as mentioned, the panel that comes closest to a consistent Dick Grayson.

And the thing they’re fighting about is that Dick missed a job interview because he was doing Nightwing things. Shawn fell in love with Dick knowing he was Nightwing (somehow), he’s been Nightwing the whole time they dated, constant interruptions and all, but she breaks up with him because somehow 'the thing I always loved most…you.’ apparently wasn’t one that included the Nightwing schedule. She also seems to be both blaming him for wanting the baby and also accusing him of not wanting it. At the risk of getting off-topic and subjective, I’ll be honest and say Shawn’s dialogue here makes no sense to me at all.

Dick’s tried not being Nightwing, in both pre-52 and new-52. Dick spends a fair amount of pre-52 time either bouncing from job to job or lacking a day job entirely. In both pre-52 and new-52, the Dick she’s claiming is the one she’s always loved the most…doesn’t exist anywhere I can think of. Certainly not anywhere during their on-panel relationship.

Now that we’ve looked at what we see of Dick and Shawn on-panel, it’s time to talk about the impact this has off-panel.

I happen to have been re-reading a lot of Chuck Dixon’s original Nightwing’s run lately. And here’s the thing. Clancy’s been showing up consistently in that run as someone Dick could be attracted to for for oh, about...two full graphic novels now (that’s 17 single-issues) and they haven’t so much as gone on a date, let alone shared a smooch. It takes 20 issues before they make it to the first date we saw from Nightwing #22. I don’t remember if she’s in every single issue of that period, so I’m going to round down by probably a lot and say that’s a minimum of a year when this was getting published for us as readers to get to know her and how she interacts with Dick, to get interested and invested in a potential relationship. In comics-time, it’s weeks before Dick actually sees her face, not just hears her voice. Even if you’re reading post-publication like me, that’s hours and hours where we watch she and Dick bond and banter and develop a mutual interest.

That’s build up. That’s emotional investment developed over time.

I’m not saying every single relationship has to take more than a year’s worth of issues on-panel to develop. However, she does summarize one of the single biggest struggles for DC’s cadre of writers over the last few years. Basically, the problem I have with this beyond just the characterizations is the same that made me stop reading from New 52 onward: DC constantly trying to skip out on the process of creating meaningful emotional build-up or connections but still expecting to cash in on an emotional payoff.

You can’t go from ‘kissed once’ to ‘been together for years like an old married couple couple vibes’ off-pages like Nightwing #15 tries to do. Even if you expect the readers to believe the protagonist now feels that connection (which, frankly, I don’t), we don’t have that connection to the relationship. It’s a cheap paper cutout with no actual emotional content behind it--why should we care if it tears under pressure? We have no stake in it; we don’t know why the protagonist has a stake in it. It’s meaningless.

As a reader, my experience with Shawn and Dick’s relationship is as follows: a) they meet in a scenario where she is his boss (strong do not date vibes) b) they meet as vigilante and paroled ex-villain and she doesn’t even let him finish a sentence (would not date) c) they show a flashback where they don’t even speak to each other (Robin pities her; no ‘date/no date’ vibe data gathered), d) they share a confusingly out of nowhere ‘emotional’ moment that didn’t match up with my prior understanding of either what I extrapolated from the flashback or what I saw in their on-panel interactions (vibe check, please??) then she disappears for several issues into police custody (no ‘date/no date’ vibe data gathered) The very next time she sees him, she betrays him (STRONG do not/would not date). Then all of a sudden at the end of that issue she kisses him.

My context for their relationship is based on two ‘emotional’ conversations of dubious quality and consistency, one ‘look’ where their dialogue contradicts my own understanding of the on-panel events, a shouting match or two, and a very major betrayal that just happened to work out alright for everybody but is never actually addressed. Most of her introductory arc where we’d be piecing out how she fits in with Dick and how they interact together, she isn’t even there for. They’ve known each other for less than a week. I the reader have known them for, in my case, maybe an hour of read-time.

And the very next time I see them, I’m supposed to believe, and more importantly, feel emotionally attached to the fact that They Are The Most In Love Couple To Ever Be In Love.

Trying to put a timeline on intimacy as a gimmick instead of establishing genuine emotional connection never works. Yes, maybe we knew that one person in high school or know someone in college who falls hard and often and met and married someone within two months, but Dick Grayson has never been that person. Maybe this style of flashback manic pixie romance would be more believable if they’d tried it on a different character with a different history and personality, but it especially never works on a character like Dick Grayson with a strong history of being slow to decide his feelings and even slower to jump into bed.

In order to work, the entire arc that follows with the kidnapping by Pyg is predicated on the fact that I, the reader, am supposed to already care about Shawn’s relationship with Dick, and that I, the reader, believe in the validity of Shawn’s relationship with Dick and in Dick’s commitment to it. But I haven’t been given time or reason to do either of those things by the time that arc starts.

You cannot shortcut relationships and expect them to be meaningful to the reader.

So they threw in a baby. Because even if you don’t care about a relationship, everyone cares about babies.

Throwing in a baby to up the emotional stakes is just a further step up that same problematic cheap-shortcuts ladder I was talking about: like in a stereotyped failing marriage, if you feel like you have to add a kid just to put meaning into your relationship again, maybe what you actually need to do is take time and consider what that relationship is built on.

#dick grayson#dc#nightwing#meta#tim seeley#panels#o.c.#relationships#asks#anonymous#analysis#shawn tsang#character analysis#relationship analysis#long post#love and relationships#I realized toward the end I hadn't addressed the pregnancy itself very much but I covered the jyst of my thoughts on it in the readmore#Dick's reaction to it felt like it was separate from his relationship to Shawn so I stuck to what it seemed like you were more interested in

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grappling with State Violence at UW

Rena Yehuda Newman (They/Them), Student Historian

As part of my research in the UW Archives, I’ve been reading through the Subject Files of the Black Student Strike, from Fall 1968 - Spring 1969. During the Black Student Strike, hundreds of students boycotted classes, marched, and disrupted business-as-usual in pursuit of 13 Demands drafted by the Black People’s Alliance. The 13 Demands included the admittance of 500 more black students, a Black Studies Department, and student control over the proposed department and the Black Cultural Center, along with several other proposals.

While the events of Black Student Strike took place over a period of months in the ‘68 - ‘69 school year, student actions came to a head around February 1969 -- and consequently, violent state actions followed.

“13 Demands”, Black Protest February 1969 Subject File, UW Archives

Most of the materials that speak to student perspective on the strikes, like protest pamphlets and literature, are in the Wisconsin Historical Society. The The UW Archives collections heavily include the administration’s perceptions of the strike, providing an intimate and harrowing look into the perspectives of the powerful during this era.

In the Black Student Strike archival subject folder there is a chronology of events narrated from an administrative perspective, likely created by the chancellor’s office from the voice and tone of the document, which frequently describes Chancellor Young’s personal schedule and other internal commentary, though the official source is not stated. The chronology details administrative interactions with black student leaders, starting in November 1968. The document narrates these events largely as inconveniences for then-Chancellor H. Edwin Young.

Using a chronology created by people in a position of power creates historical dilemmas, or at least a number of important opportunities for questioning. The chronology consistently lacks concern for student well-being, especially those of student protesters. The report often reads like a crime report against black student activists. While the record of events is helpful in providing a clear timeline of events, what is included and excluded (and what is known and unknown) by the administrative writer is informative of agenda. My selective recounting of the document is a further redaction. Do I trust the writer of this chronology? Do you trust me as a student writing about these events?

According to the document, in November and December, students engaged in talks with Young and began their protests and class boycotts. By February, the 13 Demands were brought to Chancellor Young’s office. On February 8th, “several blacks demonstrate[d] inside Field house during Ohio State-Wisconsin Basketball game, while police hold 300 demonstrators at bay outside.” The report includes that 4 policemen were injured. It does not include whether or not students were harmed.

On February 9th, the Student Senate of the Wisconsin Student Association “votes to support strike and to provide bail money.”

On February 10th, “1,500 students and sympathizers peacefully picket major classroom buildings while strike leaders emphasize at rallies that their aim is a non-violent confrontation with the University administration.”

On February 11th, “180 city policemen and county sheriff’s deputies and traffic officers -- all riot equipped -- clear demonstrators from Bascom Hall and four nearby classroom buildings.”

On February 12th, “Governor Knowles activates 900 Wisconsin National Guardsmen at the request of UW President Fred Harvey Harrington and Chancellor Edwin Young.”

On February 13th, “1,000 more guardsmen called up” in addition to to the 900 from the previous day. That day there were “ten arrests, several injuries.”

“Chronology of Activity Regarding Black Students” p.2, Black Protest February 1969 Subject File, UW Archives.

The Chancellor and President of the UW called in 1,900 armed National Guardsman against unarmed student protestors.

According to the newspapers, the UW Regents advocated heavily on behalf of this decision as well. One regent even called for budget cuts to the UW “unless University takes prompt action” ( “Legislators Label Protestors at UW ‘Long Haired Creeps’”, Wisconsin Rapids Tribune, February 12th 1969). A headline from the Madison Capitol Times intoned, “Troops to Remain at UW ‘As Long as Needed’: [Says Chancellor] Young”. Armed guardsmen "used clubs as they made their way through demonstrators” and left unrecorded numbers of students “injured in strife”, according to the Milwaukee Sentinel. (“Knowles Calls Out Guard to Restore Order at UW,” Milwaukee Sentinel. February 13th, 1969.)

I’ve read over this section of the chronology several times. Each time something inside me sinks. Right now, I can’t look at this piece of history with cool eyes. I am not removed from it, rather, I inherit it. As a student, how do I reckon with the knowledge that the leaders of my school called for state violence against their own students?

The response I have to anticipate from modern readers is common: “But that was 50 years ago. Things are different now.”

But they aren’t.

The UW Board of Regents just last year proposed and passed a piece of legislation ironically titled “The Free Speech Bill,” (SB 250) which could suspend or expel students for “disrupting” speakers invited to the UW, never mind the fact that what constitutes “disruption” remains ambiguously defined. Administrators in power within the UW system remain unfriendly to expressions of civil disobedience and free speech via protest, despite UW being a public school. Last year, I heard many professors and law students describe this policy as possibly unconstitutional, and dangerous due to its potential to create a “chilling effect” and reducing civic protests writ large. Outside of “The Free Speech Bill”, echoes of withdrawing funding from the UW because of the political actions of its students are loud and clear today. I wrote about my fears regarding the policy in a Letter to the Editor published the Daily Cardinal.

The Regents’ modern policy is not removed from the UW Administration’s past. To understand this modern connection to the armed troops employed by UW administrators during the Black Strike is to more intimately understand a legacy of state violence against student activism at UW.

As a student historian, I find it important to grapple with this legacy. If students brought these grievances up to the UW Regents and UW-Madison Chancellor’s office today, would they be remorseful or would they stand behind the violent decisions of their predecessors? Would they seek reparations? Most saliently, and perhaps most hauntingly, I need to ask: would they do it again?

For students in a particularly politically tumultuous time, when the impacts of local, state, and national policy directly harm members of student body, and the tensions between school and state seem to grow each year, the answer to that question is precarious and high stakes.

Would they do it again?

- Rena Yehuda Newman (They/Them), Student Archivist

#StudentHistory

#Student History#Student Historian#student#UW#UW-Madison#Wisconsin#Archives#UW-Archives#State Violence#Protest#Strike

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nonfiction before ‘nonfiction’

Q: The earliest citation that my OED CD-ROM has for “nonfiction” (it’s hyphenated there) is from 1903. What was it called before then? And why doesn’t “nonfiction” have its own name instead of being defined as not something else?

A: The term “nonfiction” (or “non-fiction”) is older than you think. The online Oxford English Dictionary, which is regularly updated, has an example from the mid-19th century.

As we say in a 2008 post, Oxford cites a passage from the 1867 annual report of the trustees of the Boston Public Library: “This, as we have seen, is above the proportion of our circulation between fiction and non-fiction.”

But how did English speakers refer to factual writing before the term “nonfiction” showed up?

In the past, people used terms for specific types of nonfiction writing: “history” (early Old English), “epistle” (early Old English), “story” (before 1200), “chronicle” (1303), “treatise” (before 1375), “tract” (1432-50), “diary” (1581), “essay” (1597), “journal” (1610), “dissertation” (1651), “memoir” (1659), and others. The dates are for the earliest OED citations of the terms used in their usual literary senses.

We don’t know of a word other than “nonfiction” that encompasses all kinds of writing about facts, real events, and real people, but several of the terms mentioned above, especially “history,” were used broadly in the past, embracing some of the senses of “nonfiction.”

“History,” for example, was used as a factual counterpart to “fiction” in this example from Devereux, an 1829 novel by Edward Bulwer-Lytton:

“ ‘To be sure,’ answered Hamilton, coolly, and patting his snuff-box—’to be sure we old people like history better than fiction.’ ” (The comment concerns whether a description of a person is factual or false.)

English adopted the word “history” from the classical Latin historia in Anglo-Saxon times. In Latin, the word had many senses, including an investigation, a description, a narrative, a story, and a written account of past events.

In Old English, the word (usually spelled “stær,” “ster,” or “steor”), referred to a “written narrative constituting a continuous chronological record of important or public events (esp. in a particular place) or of a particular trend, institution, or person’s life,” according to the OED.

An early Old English translation of Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica, for example, refers to “þæt stær Genesis” (“the history of Genesis”), while the Harley Glossary defines istoria, medieval Latin for historia, as “gewyrd uel stær” (“event or history”) in late Old English.

In Middle English, the “stær” spelling gave way to the Anglo-Norman and Old French spellings istorie, estoire, historie.

An Oxford citation from The Boke of Noblesse, an anonymous patriotic work written in the mid-1400s, says England’s right to Normandy is supported “by many credible bookis of olde cronicles and histories.”

“History” has sometimes been used loosely, from Middle to modern English, in the sense of a “narration of incidents, esp. (in later use) professedly true ones; a narrative, a story,” the OED says.

In this Oxford example from a 1632 travel book, the Scottish writer William Lithgow uses “history” in the sense of a true story: “all hold it to bee a Parable, and not a History.”

Why, you ask, “doesn’t nonfiction have its own name instead of being defined as not something else”?

Well, you can blame the Boston library trustees who used “nonfiction” a century and a half ago. Or you can blame the rest of us for not coming up with a positive word since then.

Some writers use the terms “creative nonfiction,” “literary nonfiction,” or “narrative nonfiction” to describe the more literary factual writing. John McPhee’s writing class at Princeton University has been called “Literature of Fact” as well as “Creative Nonfiction.”

However, the poet and essayist Phillip Lopate has described the term “creative nonfiction” as “slightly bogus.”

In a 2008 interview in Poets & Writers magazine, he says, “It’s like patting yourself on the back and saying, ‘My nonfiction is creative.’ Let the reader be the judge of that.”

Lopate prefers “literary nonfiction,” though he acknowledges that there’s “a bit of self-congratulation” in it.

In an article in the summer 2015 issue of Creative Writing magazine, the author and educator Dinty W. Moore describes some of the ways writers of nonfiction refer to their work.

Moore traces the term “creative nonfiction” to a contribution by David Madden in the 1969 Survey of Contemporary Literature.

Madden, a writer and teacher, uses the term in calling for a “redefinition” of “nonfiction” in the wake of books by Truman Capote, Jean Stafford, and Norman Mailer.

He cites Making It, the 1968 memoir by Norman Podhoretz, who says the postwar American books that mattered most to him were “works the trade quaintly called ‘nonfiction,’ as though they had only a negative existence.”

Help support the Grammarphobia Blog with your donation.

And check out our books about the English language.

from Blog – Grammarphobia https://www.grammarphobia.com/blog/2017/07/nonfiction.html

0 notes

Text

G. Thomas Couser, Body Language: Illness, Disability, and Life Writing, 13 Life Writing 3 (2016)

As much as we may like to evade or minimise them, illness and disability inescapably attend human embodiment; we are all vulnerable subjects. So it might seem natural and inevitable that the most universal, most democratic form of literature, autobiography, should address these common features of human experience. And yet self-life writing has reckoned with embodiment only relatively recently. In the Western tradition, we can date first-person life writing about illness and disability (which I have named autosomatography) from classic texts like John Donne's Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, and Several Steps in My Sickness (1624) and the essays of Michel de Montaigne. But such texts are rare—few and chronologically far between—until well after the birth of the clinic in the eighteenth century.

Granted, in the United States, the post-Civil War period saw a flurry of narratives of institutionalisation by former mental patients, a subgenre that adapted older American life writing genres, the captivity narrative and the slave narrative, to protest the injustice of the confinement of those deemed insane. But for the most part, autobiographical writing expressive of illness and disability remained quite uncommon until the second half of the twentieth century, when it flourished concurrently with successive civil rights movements. Women's liberation, with its signature manifesto Our Bodies Ourselves, supported the breast cancer narrative; the gay rights movement encouraged AIDS narrative in response to a deadly epidemic; and the disability rights movement stimulated a surge in narratives of various disabilities. Conversely, the narratives helped to advance the respective rights movements. Such writing, then, has been representative in two senses of the term: aesthetic (mimetic) and political (acting on behalf of). It has done, and continues to do, important cultural work.

Academics began to pay attention to these subgenres of autosomatography only around 1990. Although I was hardly aware of it at the time, I realise in retrospect that my interest in illness narrative had autobiographical stimuli. My mother survived breast cancer in her fifties only to succumb to ovarian cancer at the age of 64, in 1974, when I was a graduate student; a cousin my age died of breast cancer several years later. So I was intimately acquainted with stories I thought deserving of inscription and publication. For that and other reasons, as memoirs of illness and disability proliferated in the 1980s, I became convinced they were a significant new form of life writing, worthy of scholarly scrutiny.

Though not a scholar of British literature, nor a devotee of Virginia Woolf, when I stumbled on Woolf's marvellous essay ‘On Being Ill', I was struck by its recognition of ‘how tremendous [is] the spiritual change that [illness] brings, how astonishing when the lights of health go down, the undiscovered countries that are then disclosed’ (9) and by its related claim that, ‘considering how common illness is … it becomes strange indeed that illness has not taken its place … among the prime themes of literature’ (9). As Susannah Mintz's recent Hurt and Pain: Literature and the Suffering Body has demonstrated, Woolf was not entirely correct even about what she considered ‘literature’ (imaginative genres like poetry, drama, and fiction); as Mintz shows, canonical texts in those genres have been more amenable to the expression of illness and disability than recent critics (following Elaine Scarry) have claimed. Still, this was not as true of imaginative literature when Woolf made her claim, and, since her time, autobiographical writing has come to the fore as a medium in which to make sense of suffering, illness, and disability—and, more broadly, to express the experience of anomalous (but not necessarily painful) embodiment.

In 1990, I proposed and edited a special issue on illness, disability, and life writing for a/b: Auto/Biography Studies, a young journal open to new ideas (the issue ‘Illness, Disability, and Life-Writing,’ was published in 1991). In my own contribution, ‘Autopathography: Women, Illness, and Lifewriting,’ I wrote,

Though Woolf's remarks are concerned with imaginative literature, they are certainly relevant to life writing. Especially to the predicament of the female autobiographer, for [Woolf's] account of the suppression of illness in literature has as its subtext the domination of discourse by masculinist assumptions … the Western privileging of mind over body, the tendency to deny the body's intervention in intellectual and spiritual life. (68)

In the 1990s, other critics mapped this new territory. Adapting the clinical term to refer to non-clinical narratives, Ann Hunsaker Hawkins's Reconstructing Illness: Studies in Pathography (1993) was the first monograph to pay sustained attention to this sort of life writing, beginning with Donne. Not long after her pioneering book appeared, Arthur Frank published the Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, Ethics (1995). A sociologist, Frank had survived a heart attack and cancer in early middle age; indeed, he had written an illness memoir of his own, At the Will of the Body (1991). His scholarly book, then, reflected the point of view of someone with personal experience of mortal illness, on the one hand, and, on the other, a social scientist's perspective on the roles assumed and assigned in medicalisation. He supplemented Hunsaker Hawkins's mythic approach with a tripartite division of illness narratives into ‘restitution', ‘quest', and ‘chaos’ stories—a distinction that has continued to be useful to students in the field.

In Recovering Bodies: Illness, Disability and Life Writing (1997), I examined life writing generated by four conditions—breast cancer, HIV/AIDS, paralysis, and deafness. At the time, there was still not much in the way of secondary source material; my method was to read all the book-length narratives of each condition that I could find, including some that were self-published. Given the context of the various rights movements, I was particularly interested in whether, and how, these narratives (mostly, but not all, first-person in point of view) responded to the dominant discourses (sexist, homophobic, and ableist) of the bodies in question. In addition, I exposed a more general rhetorical imperative that I termed ‘the tyranny of the comic plot’—the strong preference in the literary marketplace for a positive ‘narrative arc', i.e., a happy ending. Obviously, that demand militated against first-person narratives of HIV/AIDS, which was not survivable in the early days of the epidemic; it was similarly repressive of narratives of worst-case scenarios of cancer, chronic illness, and some impairments (what Frank labeled ‘chaos narratives’).

While this special issue addresses narratives of illness and disability, the two are not the same, and we should be wary of confusing or conflating them. Illness is properly addressed by the ‘medical model', which interpellates subjects as ‘patients', assigning them the ‘sick role’ and, ideally, bringing medical intervention to bear in a beneficial way. But disability often does not require or respond to biomedical treatment. Central to Disability Studies is a distinction pertinent here, between impairment (a dysfunction in the body, which may be amenable to cure, rehabilitation, or prosthetic modification) and disability (environmental features that exclude or impede those with impairments; these require altering the context—legal, social, and architectural—in which the impaired body functions). Hence the ‘social model', which defines ‘disability’ as culturally and socially constructed.

And yet, though distinct in concept, illness and impairment often coexist in the same individuals. Indeed, in practice illness and impairment have a reciprocal relation: each may cause the other. Moreover, like disability, some illnesses—especially chronic or terminal ones—carry powerful stigmas. Illnesses, too, are susceptible to damaging social and cultural construction. For that and other reasons, recent work in Disability Studies questions the sharp distinction between illness and disability and indeed the utility of the social model. Having initially advanced the argument that disability is a harmful social construction, like race and gender, then, Disability Studies scholars are now reckoning with the limitations and flaws of that analogy. For instance, unlike other minority conditions manifest in the body, like race and gender, impairment involves disadvantages that are intrinsic, rather than extrinsic, and thus not amenable to discursive or institutional reform. Disability Studies is increasingly acknowledging that impairment may entail traumatic effects: chronic pain, progressive degeneration, and early death. Disability studies is coming around to a somewhat more favourable view of the biomedical model—at least, an acknowledgment that it is indispensable.

Given the ubiquity of illness and disability, it is notable that the distribution of narratives of anomalous physical conditions does not track their currency in the general population. A very few conditions still account for very large numbers of narratives: to the four I examined in Recovering Bodies, we could add depression (among mental illnesses), eating disorders, and, recently, autism spectrum disorders and dementia. Of course, parents continue to write narratives of severely disabled children, and most dementia narratives are written by carers, usually daughters or wives of male subjects. But with conditions that might seem to preclude first-person narration—like autism, other developmental disabilities, and dementia—the mere existence of autobiography and memoir itself challenges harmful preconceptions. Such texts are performative utterances; their composition enacts their message: there's a person here, capable of self-understanding and self-expression.

At the same time, a large number of conditions have prompted small numbers of narratives. Over the years, my informal tally of these conditions has grown steadily longer; it now includes (in alphabetical order) amputation, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig's disease), anorexia, anxiety, asthma, bipolar illness, borderline personality disorder, cerebral palsy, chronic fatigue syndrome, chronic pain, Crohn's disease, cystic fibrosis, deformity, diabetes, Down syndrome, epilepsy, insomnia, irritable bowel syndrome, locked-in syndrome, multiple sclerosis, Munchausen syndrome by proxy, obesity, obsessive-compulsive disorder, pancreatic cancer, Parkinson's, prosopagnosia (face-blindness), prostate cancer, schizophrenia, stroke, stuttering, Tourette syndrome, and vitiligo. Some of these conditions are very rare, or mysterious one-offs, like those impelling Susannah Calahan's Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness (an unusual autoimmune disorder that defied initial diagnosis) and Head Case: My Brain and Other Wonders, by Cole Cohen (a hole in her brain the size of a lemon, which accounted for her difficulty with spatial and temporal relationships). Other conditions, like large-breastedness or having undergone a lobotomy, don't qualify as illnesses or disabilities, but they involve unusual bodily configurations or experience. Collectively they constitute what I have dubbed ‘some body [two words] memoirs’ or ‘odd body memoirs’: they register the experience of living in, with, or as a particular kind of anomalous body. The appeal of such narratives is not so much to others with the condition in question (as with the narratives of more common, or more symbolically loaded, conditions) or even to those who may fear experiencing it themselves, but rather to a broader audience (which includes me) curious about what it's like to live in a body functionally or formally different from their own.

This list is not comprehensive; nor could it be: it seems that every time I browse a biography/memoir section in a large bookstore, I come across a new example. And if I think of a condition I am not aware of having been narrated, Google often proves me wrong. During the so-called memoir boom in North America, an unusual impairment or illness was considered a valid basis for a full-length memoir. Indeed, some popular examples, like Susanna Kaysen's Girl, Interrupted, have been adapted into film, and reached even wider audiences. Like Kaysen, the writers of these memoirs are often young women; like Cole Cohen and Lucy Grealy, author of Autobiography of a Face, some have earned MFA degrees from prestigious programs. Thus, professional writers have begun to flaunt bodily conditions they might once have hidden, or camouflaged in fiction. Illness and disability memoirs have achieved great popularity, critical esteem, and currency in contemporary media. Along with gay, queer, and transgendered people, ill and disabled people are coming out in life writing.

In the Internet age, the ease, decreased cost, and increasing respectability of self-publishing further facilitate such testimony. As a result, autosomatography proliferated dramatically around the turn of the millennium. Life writing about illness and disability has expanded—one might say exploded—into new modes and media as well. Beyond the realm of print stretches the vast expanse of cyberspace, which hosts blogs, online support groups, and other forms of self-representation. In addition, social media like Facebook and Twitter offer venues in which people with various medical conditions can issue running accounts of their welfare in real time, giving new simultaneity and immediacy to illness and disability narrative.

These phenomena should not be dismissed as facile or narcissistic. Whether a particular condition is heavily stigmatised or not, illness and disability can be isolating, and such isolation is inherently toxic. In this case, ‘virtual’ does not mean attenuated or artificial; virtual communities can provide vital resources, emotional support, encouragement, and stimulation in ways that actual communities sometimes fail to do. Indeed, in the case of rare conditions, face-to-face community may be simply unavailable. So the Internet provides a new kind of accessibility, especially important for those with mobility impairments. Social media can provide a sense of community that is itself therapeutic and healing.

In the United States, even mainstream media have participated in this dissemination of autosomatography. Susan Gubar, a feminist scholar best known as co-author (with Sandra Gilbert) of The Madwoman in the Attic, has followed up her 2013 Memoir of a Debulked Woman: Surviving Ovarian Cancer with occasional blog posts in the New York Times. Similarly, diagnosed with terminal cancer at the end of a literary career spent writing about others’ neurological impairments, Oliver Sacks narrated his dying in several essays published in the Times. More democratically, and more significantly, its online edition has hosted multiple sets of brief oral accounts of nearly 50 conditions under the rubric ‘Patient Voices'. Readers can hear several ordinary people of different genders, races, and backgrounds discuss their experience of each condition. Clearly, autosomatography has come of age. I welcome this phenomenon, as it expands our sense of the range of bodily experiences humans may have. It begins to address, and redress, the Cartesian privileging of mind over body.

An additional aspect of illness narrative worthy of mention here is the advent and spread of Narrative Medicine—an approach to clinical care conceived and articulated by Dr. Rita Charon and institutionalised in the Program in Narrative Medicine at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at the Columbia University Medical Center (Narrative Medicine). This approach involves training medical professionals (not solely physicians) in narrative competence (both as readers and as writers) in order to make them more empathetic and attentive to the way in which patients experience and understand their conditions. Thus, it builds on the distinction between ‘disease’ and ‘illness', where ‘disease’ refers to a disorder in the abstract, viewed through a biomedical lens, and ‘illness’ refers to a patient's particular experience of a disorder: the way it affects their life narrative, family dynamics, and so on. It approaches the patient's condition in a broad perspective comprehending its spiritual and emotional, as well as physical, dimensions. To borrow a coinage I only recently came across, we might call the goal ‘empathography', rather than pathography (Lammer). The method imagines narrative not as the bald recapitulation of a series of events—ideally, from symptoms to examination, diagnosis, treatment, and recovery—but as the construction of meaning out of the distressing, disorienting, experience of bodily disorder. In Arthur Frank's terms, the former approach yields a ‘restitution narrative', whose protagonist is the physician, rather than the patient; the latter approach, a ‘quest narrative', whose protagonist is the patient as a person.

On the face of it, this approach is consistent with what I see as the deep subtext or, to put it differently, the ‘work’ of autosomatography—not the mere expression of experiences of illness and disability but the active reclaiming of them from medicalisation (this was the implication of the title of Recovering Bodies: that illness narrators can regain authority over their bodily lives). But as Charon has herself acknowledged, Narrative Medicine entails the risk of enhancing physicians’ narrative competence at patients’ expense: it may unintentionally augment biomedical authority over the illness narrative (‘Listening’). Moreover, giving practitioners greater access to patients’ private lives can invite, and may even encourage, ethical abuses, violations of the privacy of very vulnerable subjects. In any case, while it aspires to treat the whole person, Narrative Medicine is still and only a variant of the medical model; unlike the social model, it has no designs on the world.

Ultimately, illness and disability narrative are too important to be left to physicians; as much as possible, such narrative should be authored by those with the conditions in question. And perhaps more useful to clinicians than narratives they may co-construct as practitioners of Narrative Medicine would be the careful study of illness and disability narratives, beginning in medical school. I have long been a believer in, and advocate for, the clinical value of non-clinical narratives of illness and disability. In this context I refer to autosomatography as ‘quality of life writing'—combining the sometimes problematic term ‘quality of life’ with the generic term ‘life writing’—because this body of work has great potential to demystify and destigmatise the conditions it recounts from the inside.

The essays in this issue sample, rather than survey, this rich, ever-expanding field. Because they discuss diverse kinds of materials from a variety of perspectives, they indicate numerous areas for future work. The first contribution, Ann Jurecic's ‘The illness essay', looks at once backward and forward. Glancing backward, its opening line informs us that ‘the essay was born out of suffering, injury, and recovery'. She is referring here to the inventor of the personal essay, Michel de Montaigne. I regard Montaigne's ‘On a Monster-Child’ as marking the moment in Western culture when it became possible to view a highly anomalous body not as a ‘wonder'—an omen—but rather as a mere freak of nature, so I am glad to lead off the issue with this acknowledgment of him. Jurecic's essay is forward-looking as well, however, in its focus on an emerging genre, the lyrical essay, which can address illness and disability in ways that sidestep the need for a narrative arc. As the term ‘lyrical’ suggests, her exemplary texts—Leslie Jamison's The Empathy Exams, Eula Biss's On Immunity: An Inoculation, and Rebecca Solnit's The Faraway Nearby—draw on the resources of poetry to express aspects of embodiment in original and challenging ways.

Given the importance of Virginia Woolf's essay ‘On Being Ill', it seems apropos that the issue should include Janine Utell's ‘View from the sickroom: Virginia Woolf, Dorothy Wordsworth, and writing women's lives of illness'. In it, Utell explores Woolf's literary connections with Dorothy Wordsworth, and also Elizabeth Barrett Browning, as expressed in various genres, including diaries and biography. Her focus is on how women may use writing to create ‘a transgressive space’ outside ‘normal’ life in which to negotiate complex relations with their minds and bodies.

The following article, Susannah Mintz's ‘Mindful skin: disability and the ethics of touch in life ‘riting’ represents a foray into relatively unfamiliar territory (for me, at least). It focuses on the body in a very particular way—on a very fundamental, but too often ignored, sense (`the body's most primitive’ one), that of touch—but it is also attentive to the mind. The point is of course that the body and mind are not merely in touch with each other, so to speak, but inextricable elements of one entity, aspects of a single existential and ontological being. Mintz brings together seemingly disparate phenomena—Buddhist mindfulness, disability activism, and the ethics of care—in an innovative and fruitful way. She concludes with a discussion of Mark O'Brien's memoir How I Became a Human Being (the basis for the motion picture The Sessions) and Sharon Cameron's Beautiful Work: A Meditation on Pain.

One of the liveliest new venues for autosomatography has been graphic narrative, so I am grateful for Krista Quesenberry's and Susan Merrill Squier's ‘Life writing and graphic narratives'. They trace the origins of graphic memoir and speculate about its potential for the representation of illness and disability. (One significant aspect of autosomatography in graphic form is that it renders the affected body visible to readers in a way that print does not). Their collaborative contribution is innovative in form, as well: it comprises an exchange of emails between the two as they develop ideas and insights about the new genre. Graphic narrative is already being employed in medical education, and it bids to become much more common, so their analysis is particularly timely.

As my former colleague James Berger has pointed out, Disability Studies has been slow to reckon with the traumatic nature of disability—for family and friends as well as for the disabled themselves (‘Trauma’). Similarly, Trauma Studies has largely ignored disability as an arena of trauma. Margaret Torrell's contribution, ‘Interactions: disability, trauma, and the autobiography', helps to address and repair these oversights. After a discussion of the methodology of the two fields, she uses Kenny Fries's memoir Body, Remember to demonstrate how the two approaches may complement each other.

Earlier, I touched upon the critical role that illness and disability narratives can play in medical education, beyond their appeal to lay readers. And I noted that Narrative Medicine, though collaborative, tends to situate authorship and authority in the physician. Richard Freadman's and Paula Bain's ‘Life writing and dementia care: a project to assist those “with dementia” to tell their stories’ demonstrates the possibility, and profit, of having patients author their own stories, albeit with some coaching and assistance. There are ethical dangers here, of course, but it seems clear that under the best of conditions, patients—even (or especially) those who may be losing their self-narrative competence—can benefit in multiple ways from engaging in this process. The Freadman-Bain project of leading a therapeutic writing group for dementia patients illustrates the utility of self-narrative in addressing deficits in memory and cognition. These narratives serve their authors, first, by activating and exercising their memories in the process of composition; later, as records the authors can consult for reference and value as personal creations; and still later, as memorials available to posterity.

One of the features of Life Writing that I have always valued and enjoyed is its Reflection section. This issue contains two contributions under this rubric.

Hugh Kiernan's ‘“Ah, but I was so much older then, I'm younger than that now”: cancer and a virtual relationship’ is in itself a kind of double feature. It arises from Kiernan's virtual acquaintance with another cancer patient, forged in an on-line writing forum. Kiernan has published his own narrative of living with multiple myeloma. He keeps his own illness experience in the background here, though, to showcase and respond to the poetry of his much younger female friend, who has a very different kind of cancer. In addition to introducing her voice, and enriching the issue's range by including autosomatography in poetic form, this piece testifies to the value of the Internet as a site for vital connection among those with illnesses and disabilities.

The issue concludes with Joanne Limburg's ‘“But that's just what you can't do”: personal reflections on the construction and management of identity following a late diagnosis of Asperger syndrome'. Sometimes forgotten in the study of illness and disability is the subject's obligation to enact a certain role: to play disabled, to assume the sick role, to present as ill or disabled. In this case the irony is that Limburg, who was diagnosed with Asperger's as an adult, needs to perform her disability in order to ensure that she qualifies for legal benefits and accommodation. Disability rights laws are invaluable enactments of the social model, but their application may impose peculiar burdens on those they purport to benefit. In this case, writing back (and humorously) may be the best revenge.

I want to thank Maureen Perkins for inviting me to guest-edit this special issue in the first place and for ably performing all the invisible work of organising the issue and submitting the text to the publisher. And of course, I am hugely grateful to all the contributors for their provocative articles and essays.

References

Berger, James. “Trauma without Disability, Disability without Trauma: A Disciplinary Divide.” JAC 3.2 (2004): 563–82. Web. [Google Scholar]

Calahan, Susannah. My Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness. New York: Free, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Charon, Rita. “Listening, Telling, Suffering, and Carrying On: Reflexive Practice or Health Imperialism?” MLA paper. 2011.

Charon, Rita. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness. New York: Oxford UP, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Cohen, Cole. Head Case: My Brain and Other Wonders. New York: Holt, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Couser, G. Thomas, ed. Illness, Disability, and Life-Writing. Spec. issue of a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 6.1 (1991). [Google Scholar]

Couser, G. Thomas. “Autopathography: Women, Illness, and Life-writing.” a/b: Auto/biography Studies 6.1 (Spring, 1991): 65–75. doi: 10.1080/08989575.1991.10814989[Taylor & Francis Online], [Google Scholar]

Couser, G. Thomas. Recovering Bodies: Illness, Disability, and Life Writing. Madison, WI: U of Wisconsin P, 1997. [Google Scholar]

Donne, John. Devotions upon Emergent Occasions. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1959. [Google Scholar]

Frank, Arthur W. At the Will of the Body: Reflections on Illness. Boston: Houghton, 1991. [Google Scholar]

Frank, Arthur W. The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1995.[CrossRef], [Google Scholar]

Grealy, Lucy. Autobiography of a Face. Boston: Houghton, 1994. [Google Scholar]

Gubar, Susan, and Sandra Gilbert. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-century Imagination. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 1979. [Google Scholar]

Gubar, Susan. Memoir of a Debulked Woman: Enduring Ovarian Cancer. New York: Norton, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Hunsaker Hawkins, Ann. Reconstructing Illness: Studies in Pathography.West Lafayette, IN: Purdue UP, 1993. [Google Scholar]

Kaysen, Susanna. Girl, Interrupted. New York: Turtle Bay, 1993. [Google Scholar]

Lammer, Christine. Empathography. Vienna: Verlag, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Mintz, Susannah B. Hurt and Pain: Literature and the Suffering Body. New York: Bloomsbury, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Scarry, Elaine. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World.New York: Oxford UP, 1985. [Google Scholar]

Woolf, Virginia. “On Being Ill.” ‘The Moment’ and Other Essays. New York: Harcourt, 1948. 9–23.

0 notes