#odysseus and penelope make the world go round

Text

Isn't it freaking adorable how both Odysseus and Penelope could remember down to exact detail what clothing she had packed for Odysseus before he left for war even 20 years later?!

😭😭😭😭😭😭😭😭😭

And she packed them herself. She didn't use the help of any servant or slave to do it. She wanted to prepare her husband herself. What is even more is that all the clothes were of vibrant colors which had me thinking;

What if Penelope deliberately prepared vibrant colored clothes for Odysseus solely so that she could see him from afar for as long as possible?! And man I can so imagine her doing the same! Like standing on the top of the hill where the palace is, wearing a vibrant dress that floats in the wind, holding baby Telemachus in her arms and watch Odysseus's bright tunic on the ship and Odysseus turning his head to look up at that aetherial figure on the hill almost leaning over the ship to see her JUST FOR A LITTLE LONGER until he cannot see her anymore and this is where he keeps looking at his island becoming smaller and smaller to the horizon, shedding tears of goodbye

🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺

Man ninjas are cutting onions around me again!!!

#greek mythology#odysseus#the odyssey#greek myth#odyssey#the iliad#iliad#odypen#odysseus and penelope#the odyssey 1997#trojan war#ithaca#telemachus#tears of goodbye#war#odysseus leaving ithaca is probably one of the saddest moments in greek mythology#odysseus the sailor#odysseus the master mariner#penelope won't see her husband's face for another 2 decades#sad separation#separation#odysseus and penelope make the world go round#tagamemnon#odysseus father of telemachus#homeric poems#homecoming odysseus#homeric epics#homer

288 notes

·

View notes

Text

|| Steven Grant vs. You : III ||

A tiny story where you discover that your sweet, handsome coworker is just as much into Egyptology as you are into ancient Greece- and the playful battle that ensues.

PART I - PART II - PART III

Word Count: 2.9K

Tag List

Read this on A03!

Referenced works-

Hesiod. Theogony and Works and Days (Oxford World's Classics) OUP Oxford.

Richard Mayde. Ancient Egypt, Dodd, Mead

Gerald D. Waxman, Astronomical Tidbits: A Layperson's Guide to Astronomy

Let us begin our singing. It will haunt this great and holy mountain, and we will dance on our soft feet round the violet-dark spring and the altar of the mighty son of Kronos. We will bathe our gentle skin in Permessos. Then, on the highest slope we will make our dances, fair and lovely, stepping lively in time. From there we go forth, veiled in thick mist, and walk by night, uttering beautiful voice.

So said mighty Zeus’ daughters, they breathed into me wondrous voice, so that I should celebrate things of the future and things that were aforetime. Come now, from the Muses let us begin, as they tell of what is and what shall be and what was aforetime, voices in unison. The words flow untiring from their mouths, and sweet.

“I mean… just wow…” Steven sighed, eyes twinkling at you from across your desk.

“I know.” You nodded with deep satisfaction.

“You’re right, too.” he continued, “You really do get this sense that they were there.”

“It feels like it, huh?” you agreed, “With ancient Egypt, you have Pharaoh as the representative of higher power, but there isn’t this deep and messy interaction with the gods that I’ve come to love so much out of Greek myth. Especially when historical artists made work where they themselves interacted with gods, or were at least in conversation with them, like this or like Sappho.”

Lately, when Steven worked mornings, he had taken to peering into your cubicle on his breaks to see if you weren’t too busy for him to visit. It was quickly becoming your favorite ritual, and you found yourself often looking past your cubicle’s entrance as if you could will his curly head of hair to appear.

“I think the closest equivalent I can come to is the temple of Philae…” Steven thought aloud, he leaned over your desk excitedly. You smiled, nodding as you thought of the description of it in the book Steven lent you.

Close by this temple of Osiris at Philae was a small one, dedicated to his queen and sister, Isis. A later writer speaks of it as “the most strangely wild and beautiful spot he ever beheld. Here spreads a deep drift of silvery sand, fringed by rich verdure and purple blossoms; there, a grove of palms, intermingled with flowering acacia; and there, through vistas of craggy cliffs and gloomy foliage, gleams a calm blue lake, with the sacred island in the midst, green to the water’s edge, except where the walls of the old temple city are reflected.”

“From the little I’ve glimpsed so far, it seems like Osirus and Isis’ marriage is a very popular story?”

“Oh, yea, super.” Steven nodded significantly. “And for good reason too- I mean sewing your husband’s body back from fourteen pieces is quite a testimony to your love, I think.” There was a quiet pause as you took a moment to make sure the two of you were still being ignored, before Steven continued, “Is there a love story you like from Greek mythology?”

“Oh-” you took in a deep breath, overwhelmed by the question. “There are so many… I mean so, so many. You have the big ones, you know- like Odysseus and Penelope, Patroclus and Achilles, Hades and Persephone, the love triangle of Aphrodite, Ares and Hephaestus… the Greeks adored a good love story. They had 8 different kinds of Love, after all.”

“Eight, really?” Steven asked, leaning even further over your desk, his smile unfading.

“Yes! You have Storge, familial love. Philautia, self love. Agape, which I quite like, that’s love for everyone.”

“Ooh that’s very grand.” Steven chuckled.

“It is! Philia is also lovely- that’s deep friendship.”

“Alright, that was four.” he counted, tilting his head as he looked into your eyes. If there were any emails or phone calls incoming you would have never known. You met Steven’s gaze, smiling back at him and feeling, strangely, as if you couldn’t inhale as much air as you would like to.

“Mhm… then we have Mania, which is obsessive love. You know, when you can’t stop thinking about someone and you’re just-” you shook your head, grinning, “kinda like when you first fall in love for someone, really hard, and you can’t think about anything else, you’re just tortured?”

A change passed over Steven’s face that was initially hard for you to read. At first, you thought the brightness of his eyes dimmed at your last words, but as you searched his face you realized that his eyes weren’t less bright due to dismay or boredom, they were less bright because his pupils were dilating as he watched you. Steven was so close to you that you could even see your own silhouette in his widening gaze.

“Um…” you continued on, swallowing dryly, “A..Another favorite of mine, Ludus… which is playful love, or like- young love. Eros, probably the best known, as it’s the spicy one. And lastly you have the love I’m certain Osirus and Isis shared…”

“What’s that one called?” Steven asked, eyes widening.

“Pragma, longstanding love… kind of the end goal, really.”

You jumped with a start as your desk phone began to ring loudly. Steven cleared his throat, pulling himself off of your desk and back into his chair, rubbing the side of his face with one hand as you twisted to pick up your phone. You frowned as you recognized the number on caller i.d. to be the gift shop’s extension. “Ut oh Steven…” you mumbled, picking up the phone. “Reception- how can I help you?” you answered as neutrally as possible, but you almost lost your professional composure as you glanced nervously at Steven, and found him staring at you like a child caught with their hand in the proverbial cookie jar.

“Hello- could you please tell me if there is a gift shop employee in the office? His name is Stevie?”

“Stevie?” you repeated, confused. Steven rolled his eyes, exasperated. “No, there is definitely no Stevie here I’m sorry to say… office is pretty empty. Is there something I can help you wi-” the phone clicked in your ear. Frowning, you pulled the receiver away from you to look at it, before hanging up the line and looking at Steven.

“Did Donna just hang up on you?” he asked, startled.

“I think she did?” you replied laughing, aghast.

“Oi- I hate that, I’m sorry.” Steven grimaced, standing up. “I don’t want you getting into trouble.”

“I’m not concerned, we work in two totally separate departments.” you shrugged. This seemed to reassure Steven as he patted down his pants pockets and made sure he had everything.

“Time to go sell some plastic ankhs?” you teased, grinning.

“Oh yes.” Steven replied lamely. “Some Nike of Samothrace snow globes as well.”

“Ouch- you got me.” you laughed, standing up too. You opened your mouth to ask about seeing him for lunch before you stopped yourself- what if you were being too demanding of his attention? With these new visits, any free time Steven had was being claimed by you. It felt presumptive to assume he wouldn’t like some time for himself. “Um… do you have any plans you're looking forward to, today?”

“Finishing the Theogony, that’s about it.” Steven replied, stepping out of your cubicle. “Talk about it over lunch, yea?”

You felt yourself blush. “If you want to!”

“Cheers!” Steven exclaimed, before darting away.

You sat back in your office chair and swiveled to face your computer, smiling to yourself. Steven was good. He was so, so good. Sighing dreamily, you refreshed your email and watched your screen filled with messages.

As you clicked through your emails you couldn’t help but to keep thinking about Steven, how lucky you were to become friends after only a few weeks of working at the museum. Even though Donna and Steven’s relationship didn’t seem great, part of you envied the amount they got to interact as a team. Your role was mostly emails between curators, accountants, marketing agents, and the Liaison Department.

You straightened in your chair as something occurred to you, hadn’t Steven said that he wanted to be a tour guide? You opened an email from Marketing briefing the Liaison Department on a new collection of work that would be showcased soon, asking the liaisons to study up on the attached pdf’s of art history so they could speak about the collection. You still hadn’t figured out why you seemed to be CC’d on every single email from any department under the museum roof, but now that didn’t seem so bad. They were all there- any branch manager you needed was available to you… even the curation team for the ancient Egyptian collection.

“What have you got today?” you asked as you sat down beside Steven in the break room.

“I think what you mean is, what have I got us today!”’ Steven said triumphantly, as he pulled from his bag not one, but two lunches.

“What!” you exclaimed, eyebrows raised.

“Yea dove I made you lunch!” Steven grinned, all the more satisfied by your surprise. “It’s not bad either, we’ve got apples, some crisps, and avocado sandwiches! They’re quite good really, they’ve got lettuce and tomato in, and this spicy mustard.”

Steven set your lunch before you with a level of excitement equal to a conductor beginning a symphony. All you could do was stare, and make some strange smile with your mouth partly open, as you looked between him and the slightly crumpled, but still appetizing sandwich before you.

“I wanted to try and make this vegan caramel for the apples but I rather bungled that…” he continued, reminiscing on his caramel attempt with a cringe.

“I’m-“ you started to say, but you didn’t actually know what you were. Aside from the obvious attributes: deeply flattered, touched, and surprised. There was a tightness in your throat that you’d only usually felt when you were about to cry, but there were no tears forming in your eyes. You stared at the sandwich as if it held monumental power.

With a crunch, Steven bit into his apple. He nudged your arm with his elbow as he took another bite. You jumped a little and picked up your own.

“Cheers!” Steven said, tapping his apple against yours. Chucking, you took a bite.

You couldn’t have known how strange it was for Steven to be eating a lunch he made with a friend. He was nearly as surprised as you, that he was able to sit down with you today and provide this meal. Steven had never been very good about remembering to make himself up a lunch to take to work, but the idea of also making one for you, however modest it may be, was so exciting that it stuck in his mind. Instead of only remembering he should have packed food by the time he was clocking out for lunch, he had stopped at the market on the way home last night, imagining how this very moment would play out. As was usual, he had been hesitant to fall asleep, but the thought of having time in the morning to carefully assemble sandwiches gripped him with excitement and so he’d done his best, making sure his ankle restraint was tightly fastened to his leg no later than midnight, and stared up at his dark ceiling, silently begging it to let him sleep peacefully.

When Steven woke up it was nearly dawn. He was so bewildered by the unique light of early morning that for a moment he thought he’d only slept for a few minutes. His ankle was still securely fastened to its brace, and even more profoundly, he felt rested. Steven felt like he had won, but there was also a bitter sweetness to realizing his night had gone exactly as intended- that it was unlikely to happen again, or consistently.

He tried to brush off that anxiety though, as he watched you take the first bite of the sandwich he made. Whether you were just being angelically polite or genuinely enjoying it, he appreciated your attention nevertheless. What was better? To try and have some plans, some gifts, some special moments never materialize- or to never meet the opportunity to surprise you and make you smile?

That was an easy answer.

“You failed to mention earlier,” Steven started, chewing through a large bite of bread, “what your favorite ancient Greek love story is?”

“Oh right! Well that’s so difficult!” you groaned, grinning. “The reason may be nuanced, but I love Selene and Endymion’s story.”

“What is it?”

“Selene is the Moon goddess in the ancient Greek pantheon, and Endymion was a mortal shepherd Prince that would take his flock over hills and mountains at night. They fell in love, but because she was immortal and Endymion was not, Zeus extended his life by casting an eternal sleep upon Endymion.”

“Alright?” Steven responded, gesturing for you to keep explaining.

“That’s pretty much the whole story.” you laughed.

“Why is that your favorite then?” Steven asked, more spellbound than anything.

“Because! Okay this might sound a little cheesy but-”

“Sorry, I can’t do cheese. I’m vegan, remember?” Steven said with mock severity.

“Wow.” you replied flatly. You leaned back a little to watch Steven have a very hard time not laughing at his own joke. “Proud of yourself?”

“Go on, keep telling me why-” he choked out, bringing his hands to cover his mouth.

“No, no…” you replied, you resisted the twitch of a smile on your own face. “I don’t think I can after being eviscerated by your lactose free wit.”

“Please-” Steven wheezed faintly, nodding encouragingly, “Please, tell me.”

“Well-” you sighed haggardly, “What I was going to say is that I like it, because to me it feels metaphorical? No one should really ‘see’ the moon because it is at its best when we should be asleep, and yet we have and we do- and we have done for hundreds of years? Cultures with no connection all over the world have fallen in love with the Moon, which appears in its highest glory when our eyes should be closed? And I just think of that when thinking of Endymion. I think of how the night sky infatuates us, how humankind has always been so rhapsodic about it, even though as creatures we are useless in the dark and the night does little for anyone in a practical sense.

“Endymion is in this eternal sleep, induced by his love for the Moon… again, metaphorically, he’s fed by his affection for something so lovely? It just so simply encapsulates this understanding that people had way back then that even in a time of hardship, beauty was longed for and nourished humankind?”

Steven had stopped eating. He was simply staring at you, eyebrows raised.

“I know it sounds like I’ve thought about it too much- it’s because I do.” you qualified, embarrassed.

“No-” Steven replied, voice soft, brow furrowed. “You’re alright… that was, that’s good.”

You were not convinced that Steven was genuine in his reassurance. You cast your eyes downward, mind racing. This was an overstep on your part- you got a little too romantic, waxed a little too poetic about your favorite topic. You wanted to try to ground your thoughts. “Um… there’s an… there’s a quote from this book.” you offered weakly, pulling your phone out of your pocket for reference.

You read aloud, “There is a fundamental reason why we look at the sky with wonder and longing—for the same reason that we stand, hour after hour, gazing at the distant swell of the open ocean. There is something like an ancient wisdom, encoded and tucked away in our DNA, that knows its point of origin as surely as a salmon knows its creek. Intellectually, we may not want to return there, but the genes know, and long for their origins—their home in the salty depths. But if the seas are our immediate source, the penultimate source is certainly the heavens… The spectacular truth is—and this is something that your DNA has known all along—the very atoms of your body—the iron, calcium, phosphorus, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and on and on—were initially forged in long-dead stars. This is why, when you stand outside under a moonless, country sky, you feel some ineffable tugging at your innards. We are star stuff.“ The quiet you were greeted with felt unbearable. Quickly tucking your phone back in your pocket, you smiled, and sighed. “I mean those are the words of an astronomer, but the ancient Greeks were saying the same thing- We can’t help ourselves. We’re all in love with the moon.”

Mania. Steven thought.

“I…” Steven started, before stopping himself with a shake of his head. He still hadn’t touched any food. Sighing your name, Steven glanced into your eyes, head still shaking. “You… um, you think- You think very beautifully.”

“Hah-” you breathed, it was a sound of deepest regret. Why? Why had you been so open. You could have probably cooked an egg on your cheek, it felt so warm. You were desperate for some way out of being the talkative one. “You know, I don’t actually know if there was a Moon god in the Egyptian pantheon?”

“Oh-” Steven’s tone changed to something significantly less enchanted. “Yea. His name is Khonshu, god of the Moon, protector of those who travel at night.”

“...not a fan?” you asked, unable to help smiling at how personally offended Steven seemed by invoking Khonshu.

“Not really.” he replied, shrugging.

“Aha!” you grinned, taking a triumphant bite of your apple. “And there it is.”

“What?” Steven asked.

“The beginning of the end, Steven.” you hummed, “Greek god versus Egyptian God, Selene beats Khonshu.”

“HAH!” Steven laughed so loudly the rest of your coworkers in the break room glanced over. Why did this always happen to you two? Steven grasped at his chest, his eyes closed by the strength of his giggles. “Alright dove, that one you can have.”

TAG LIST:

@oliviagreenaway @then-he-was-wrong-about-me @b0xerdancer

#steven grant#steven grant x reader#steven grant x you#steven grant fluff#steven grant / reader#moon knight x reader#moon knight#moon knight x you#mcu moon knight#moon knight fan fiction#moon knight imagines#non binary reader#non binary fan fic#steven grant vs. you#fictive-fodder#fictive fodder

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

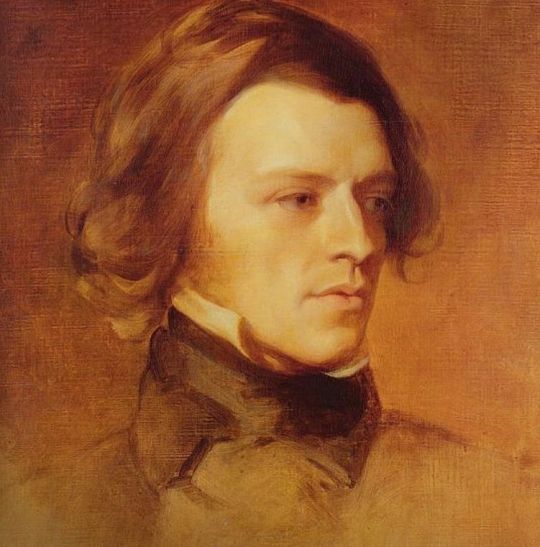

National Poetry Month #1 - Ulysses - Alfred, Lord Tennyson

[Cover Photo: Ulysses and his Bow, N.C. Wyeth]

To start us off, we will begin with familiar ground and talk about Tennyson, about dealing with adversity, and about perspective. We’ll start with the subject, then the poet, then the poem itself. It is a poem with some memorable lines, including:

I am a part of all that I have met;

And

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

Ulysses (Odysseus to us Greeks - Ulysses is the Romanization) is an unusual hero, as ancient heroes go. He was a man of many talents (“polytropos”), but few superlatives. He wasn’t the biggest or bravest or most skilled warrior. In fact he was a reluctant hero. He wasn’t the most devout - he was a doubter at times. He was, however, a good archer and a very cunning individual - clever, crafty, and above all a survivor. He lived through ten years of war and ten years of wandering that many others did not.

[ Calypso And Odysseus - a painting by Sir William Russell Flint ]

And while he may have tarried with Circe, and with Calypso (not entirely his fault), he yearned to be home with his wife Penelope. What he had to do to be with her again is one of the more gruesome tales in all literature. I would argue that Ulysses was a man whose adult life was one long series of exercises in dealing with adversity.

The same could be said for Alfred Tennyson(1809-1892). Yes, he was the longest-reigning English Poet Laureate, and yes, in his time, someone said that the only more famous people in England were Queen Victoria and Lord Gladstone. But Tennyson spent much of his first forty years in poverty and depression, putting off marriage because he could not support a wife, and because he feared he would come down with epilepsy. He didn’t - but he was treated extensively for depression, and every one of his ten siblings who made it to adulthood had at least one bout with mental illness, as did his father, who also drank heavily until his death.

That loss, the death of his close friend from his college years, Arthur Hugh Hallam, and the death of Tennyson's own son Hallam, named for his friend, all took a toll on him. He was also lambasted with searingly critical reviews - often by those taking a personal jab at him through his work. However, like Ulysses, he persevered. Whenever he was depressed or downtrodden, he wrote. He revised and rewrote. And the end product, while uneven, was voluminous, and within it were scattered many lyric gems that made him famous, and eventually wealthy, and are lines you might find familiar even now.

So what is today’s poem about? It is about Ulysses the survivor. The man who lived long, looking back at his life - perhaps wistfully rather than with regret. He has suffered greatly, but knows that he has been a part of great things, and seen much, and had great friendships and been given honor. This is a very different protagonist than the one in Locksley Hall, which appeared in the same volume. This is a man with seemingly but one regret - that he is no longer the one striving, exploring, battling, adventuring - but at the same time, he does not feel useless:

Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods.

And though he is a realist:

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

He still has the will and the fortitude that he had all his life. I hope, for Tennyson’s sake, that this was the mindset that he, too, took with him into his later years. The rest of the Tennyson collection at The Other Pages can be found HERE

.

Ulysses

It little profits that an idle king,

By this still hearth, among these barren crags,

Match'd with an aged wife, I mete and dole

Unequal laws unto a savage race,

That hoard, and sleep, and feed, and know not me.

I cannot rest from travel: I will drink

Life to the lees: All times I have enjoy'd

Greatly, have suffer'd greatly, both with those

That loved me, and alone, on shore, and when

Thro' scudding drifts the rainy Hyades

Vext the dim sea: I am become a name;

For always roaming with a hungry heart

Much have I seen and known; cities of men

And manners, climates, councils, governments,

Myself not least, but honour'd of them all;

And drunk delight of battle with my peers,

Far on the ringing plains of windy Troy.

I am a part of all that I have met;

Yet all experience is an arch wherethro'

Gleams that untravell'd world whose margin fades

For ever and forever when I move.

How dull it is to pause, to make an end,

To rust unburnish'd, not to shine in use!

As tho' to breathe were life! Life piled on life

Were all too little, and of one to me

Little remains: but every hour is saved

From that eternal silence, something more,

A bringer of new things; and vile it were

For some three suns to store and hoard myself,

And this gray spirit yearning in desire

To follow knowledge like a sinking star,

Beyond the utmost bound of human thought.

This is my son, mine own Telemachus,

To whom I leave the sceptre and the isle,--

Well-loved of me, discerning to fulfil

This labour, by slow prudence to make mild

A rugged people, and thro' soft degrees

Subdue them to the useful and the good.

Most blameless is he, centred in the sphere

Of common duties, decent not to fail

In offices of tenderness, and pay

Meet adoration to my household gods,

When I am gone. He works his work, I mine.

There lies the port; the vessel puffs her sail:

There gloom the dark, broad seas. My mariners,

Souls that have toil'd, and wrought, and thought with me--

That ever with a frolic welcome took

The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed

Free hearts, free foreheads--you and I are old;

Old age hath yet his honour and his toil;

Death closes all: but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods.

The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks:

The long day wanes: the slow moon climbs: the deep

Moans round with many voices. Come, my friends,

'T is not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

It may be that the gulfs will wash us down:

It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles,

And see the great Achilles, whom we knew.

Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho'

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

-- Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Read it once or twice out loud, and I think you’ll like it. It’s still a popular poem, and there are several dramatic readings available on the web, but I don’t like the ones I’ve found so I haven’t linked any of them. Mostly they focus on the drama and not the wistfulness. In my view they seem heavily over-acted. The part near the end about:

for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

I used as the motivating thought for the novella, “To the Gates of the Western Sea,” which hopefully will come out this summer.

--Steve

#tennyson#alfred tennyson#ulysses#odysseus#odyssey#epic#soliloquy#national poetry month#the other pages#theotherpages.org#poem#poems#poet#poets#poetry#adversity#perserverence#memory#regret#persistence

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Short bedtime stories for girlfriend -

George Sands says “There is only one happiness in life—to love and be loved.” Being one of the most famous love quotes, this also defines the feeling which has left lovers spellbound for ages. Let’s uncover the mystery of love through the famous stories of love which capture our heart every time we hear them.We have all experienced the power of love once in our lives. The unimaginable feeling when our lives revolved around that one person.

How can anyone forget the emotions which have been echoed time and again by stories of love across generations?For all of the lovers in the world, who are looking for a way to connect with their significant other before they go to sleep, this blog post is for you. It has one of the famous romantic short bedtime stories for girlfriend to read before your loved one falls asleep and then wakes up refreshed and ready to face tomorrow's challenges together.All-time Famous Romantic

Short Bedtime Stories for Girlfriend One of the most famous love stories of all time is the story of two teenagers who have become the synonym for love – Romeo and Juliet.

The tragic love story by Shakespeare strengthens the belief of Geoffrey Chaucer who famously said in his work – The Canterbury Tales that ‘Love is blind’. Shakespeare’s lovers blinded by the passion and love died for each other in the midst of their feuding families.Though Romeo and Juliet is probably one of the most famous love stories which has been captured on the silver screen many a times, another affair which has rocked the imagination of many is the historic affair of Antony and Cleopatra. As W.S. Gilbert says in Iolanthe – ‘its love that makes the world go round’, the world of these two lovers revolved around each other.

The affair abruptly ends during the war between the Egyptians and Romans when the false death news of Cleopatra shatters Antony who accidentally falls on his own sword and dies. Following this news, Cleopatra sacrifices herself. Such love and selfless act of sacrifice makes this story stand out in the list of love stories across many generations.While talking about love stories, who can forget the famous French affair of Napoleon and Josephine who parted when Napoleon left Josephine as she could not bear him an heir. Though this might seem selfish for many, the lovers never faltered in their love as their passion for each other was embalmed in their hearts till they died.

The story goes forward with a sense of urgency and passion, as the protagonist is driven by an overwhelming feeling that their partner will not be able to survive without them. This drives every action in the story - from fighting for life after being stabbed multiple times, to lying about his whereabouts so he can see her again. The passage "he wanted nothing more than just exist" reminds us how important it is live our lives passionately because death may catch up sooner or later.The love stories of all times reflect that “the course of true love never did run smooth”, but that has not deterred lovers from falling and expressing their love for each other. Be it the epic lovers of Sir Lancelot and Queen Guinevere, or the Greek love stories of Paris and Helena, Orpheus and Eurydice, and Odysseus and Penelope, or the much recent passion love stories of Juan and Evita Peron from Argentine or the Indian love epic behind the TajMahal – Shah Jahan and MumtazMahal.All stories of love express one of the finest quotes by George Eliot – “Among the blessings of love there is hardly one more exquisite than the sense that in uniting the beloved life to ours we can watch over its happiness, bring comfort where hardship was, and over memories of privation and suffering open the sweetest fountains of joy.”

It was romanticand short bedtime stories for girlfriend. It is not always easy to come up with a new story but this collection of 18 mini tales will have you covered. You'll find your way through everything from silly childhood antics, to love lost and found again, to the joys of married life. There's something here for everyone.

#best love quotes for love Syllabus#bedtime story for boyfriend#short bedtime stories for girlfriend#passionate love messages for him#romantic bedtime stories for boyfriend#bedtime-love-stories-for-couples

0 notes

Text

Imagine a Shared Cinematic Greek Mythology Universe

Franchises are a huge thing these days. Everyone wants one. Marvel did it best, DC is... trying to get the hang of it and Universal, honestly I don’t know what that mess is supposed to be at the end of the day.

Comics offer this kind of thing. And what else offers it would be mythology. I have never seen a good movie about Greek mythology. And there are so many different tales to tale and so many different heroes to introduce.

Now, let me propose to you a 13 movie shared cinematic universe for Greek mythology.

Herakles: Birth of a Hero

Of course, we’d kickstart our shared universe with the household name of Herakles. Because everyone knows that name, knows that hero. He can get butts in seats to pique the interest of the people.

But I want more than just the average tale. I want some focus on his backstory too. I mean, holy Hades the fact that he literally has a twin-brother and that Herakles is just a title and not his actual name - born Alcaeus, thank you very much - are so easily forgotten and just ignored. Do it right. Do it rich and detailed.

A simple origin story as the beginning, of Alcaeus, growing up with his big sister Laonome and his twin-brother Iphicles, listening to the heroic tales of his great-grandfather/half-brother Perseus. Dreaming to be like him. Setting out to become the great Herakles.

We cover some of his labors, after all he does have twelve of them and all twelve in one movie is just gonna overcrowd it with plot. So have a slow set-up and let’s go with maybe three or four labors. Because this is a franchise, so we can divide his tales into like a trilogy.

We know there are 12 labors to finish, but this movie ends semi-rounded up. He found one of his various lovers - let’s go with Megara, because she is the most famous and does for a great set-up for the second movie - he seems ready to settle down and be happy.

In the post-credit scene, we see a vicious Hera, watching from above - teasing that she’s not going to stand for his happiness.

Theseus: The daughters of Zeus

Theseus is up next. I also see that one as a trilogy - though, of course, as with the MCU we do not just dash all three of them out one after the other.

First movie in the franchise sees Theseus teaming up with his best friend Pirithous, son of Zeus. They got up to some shit together in the myths, among other, trying to abduct “daughters of Zeus”.

They went to the underworld to abduct Persephone and they also tried to steal Helen of Troy, being fought off by Helen’s brothers Castor and Pollux (cameo back-door introduction of Helen, Castor and Pollux and set-up for the Trojan war movie later down the line).

I think this would be a really fun way to do some world-building, by giving characters that will be important in the future already small cameos. And you get to explore a whole new world in the underworld.

Just a buddy hero movie of two friends getting up to shenanigans.

And, here’s where we get our first little crossover, because when Pirithous and Theseus ventured into the underworld, they got stuck there and then were saved by Herakles who was down there for his twelve labors. So we also have him give a very tiny cameo - really jut one scene, five to ten minutes, he’s not supposed to steal the movie but to establish that yes, these worlds are shared.

Herakles 2: The Labors of Herakles

This movie would be set up in a post-credit scene of Theseus, where after Theseus and Pirithous left the underworld, we see Herakles wrestling the three-headed guard-dog of the underworld. Zerberus, the reason he was in the underworld to begin with.

But that’s his last labor and more of a tease, really.

We start off with the whole driven mad by Hera and killing Megara thing first. And yes, I’m taking liberties with the myths a liiittle here because technically all of Herakles’ labors were given to him by Hera to appease her and to repent for “his” crimes. But as mentioned before, 12 labors in one movie is going to cram it and we do want some action in the first one already.

We cover the other left-over labors he didn’t accomplish in the first movie now. Lots of action, lots of monsters, lots of fighting - and another cameo, because labor number 9 features Herakles going to the Amazons and stealing Queen Hippolyta’s girdle. So we meet the Amazons.

Theseus 2: The Labors of Theseus

Okay, after the origin-esque first Theseus movie, we move on to the one about his more famous heroics - the whole bandit-killing, sow-slaying, wrestling and all that jazz.

The six labors of Theseus.

Throw in Theseus meeting the Amazons too, meaning Hippolyta and her little sister Melanippe get a reoccuring appearance and crossing over between the Herakles and the Theseus franchises. Because the most fun thing about a shared universe is the shared part.

Jason and the Argonauts

Whoop, time for the Avengers/Justice League! Time for the first team-up movie!

Jason assembles a team to go on a long-ass journey to find the Golden Fleece.

Including both Castor and Pollux, as well as Herakles. Among many, many others.

Like the twin sons of Hermes Eurytus and Echion, who I picture as the Weasleys of this universe. Because every good franchise needs two fun brothers.

Then there are Zetes and Calais, the sons of wind-god Boreas.

And Calais’ lover Orpheus, the son of Apollo, who will set up his own stand-alone movie in this.

Also featuring pilot Erginus, son of Poseidon, and Palaomonius, the bronze-smith and son of Hephaestus. Because there’s nothing more fun than a demigod team-up. And yes, I want them to actually use their powers.

And, of course, Jason’s lover the witch Medea (who is also the cousin of Ariadne, so there could be an Easter Egg name-dropping here).

And the most famous female Greek hero - Atalanta.

A wild fun ride follows as they search.

It also serves as a set-up for the Trojan War by re-introducing Castor and Pollux, a set-up for the stand-alone Orpheus movie and the second team-up movie led by Atalanta.

We’d also put a post-credit scene in here to tease Heracles 3, just showing Herakles happy in the arms of a woman.

Orpheus and Eurydice

Keeping it close time-wise, we tie in with the Orpheus stand-alone movie after Jason and the Argonauts.

Orpheus going to the underworld to bring back the love of his life Eurydice after she dies. Him charming Hades and Persephone, who get to make their third appearance after already encountering Herakles and Theseus, with his beautiful voice, but still failing.

Theseus 3: The Labyrinth of the Minotaur

Let’s break the flow a little and bring back Theseus for his third movie - and his most famous story.

Because just because something is the most well-known tale does not mean it has to be the first. That way, we always get stuck with the very same stories being told all the time, because most of the time it never gets past one movie. No. Let’s save Theseus’ most well-known tale to be the third in the franchise - because this is in my head and in my head, the franchise is allowed to expand this far and we do not need to worry about cancellation and such.

Theseus meeting Ariadne and Daedalus and slaying the Minotaur in the labyrinth. You know the story.

Atalanta: Huntress of Artemis

After we previously met Atalanta in Jason and the Argonauts, let’s give the greatest heroine her own stand-alone movie.

After all, she is a famous racer, a great hunter, an Argonaut, a huntress of Artemis and became a minor hunting goddess later on. She’s been busy and her story is worth telling.

In this, I’d like to focus on the huntress-aspect. Maybe include the tale of Artemis and Orion in here and tie that into how Atalanta joined the goddess’ hunt. Have her be trained by Artemis and befriend other huntresses.

Supporting cast would to me include the three daughrers of Boreas - Hekaerge, Loxo and Oupis, as well as Britomartis who’s the daughter of Zeus, and Phylonoe, who is actually not just a huntress but also a sister to Helen, Castor and Pollux.

Achilles: Hero of Sparta

Cue in Castor and Pollux again, after their small Theseus cameo and their supporting roles in Jason and the Argonauts, they are now back for the big story.

We start the story right though.

Eris, pulling a prank on the goddesses on Olympus with the golden apple for “the fairest of them all”. The goddesses pick Paris of Troy and make him chose. After he picks Aphrodite, she promises him the prettiest lady around - Helen of Sparta.

Castor and Pollux alone stand no chance. But they got friends.

Achilles, Patroclus, Odysseus, Francis Ajax and Phoenix.

The Trojan War ensues and in the end, sets up the Odyssey as our friends part ways and Odysseus claims to look forward to seeing his wife Penelope again.

Odysseus: Long Way Home

Taking place directly after Achilles: Hero of Sparta and featuring Odysseus’ ridiculous journey home. Seriously, that guy should have just asked for directions.

Visiting Circe and meeting Calypso and fighting off sirens. All the fun stuff that then pays off by the heartfelt reunion between two lovers long separated.

Atalanta 2: Hunt for the Calydonian Boar

After her supporting role in Jason and the Argonauts and her stand-alone movie, she’s now back to be the one to lead the second team-up movie.

The hunt for the Calydonian Boar was kind of a real big deal back in the day, you know. Everyone participated, everyone wanted to be the one to kill it.

And I mean everyone.

We see the return of not just Theseus but also his buddy Pirithous.

Atalanta’s fellow Argonauts Eurytus and Echion are going to bring all the fun as the comic-relief tricksters again.

Castor and Pollux are back for this one too!

And hey, even Phoenix from the Trojan war will be here.

Because the thing about those big franchises is that more characters need to cross over. If all those characters exist in the same world, how are they always so strictly separated? No. The characters who dabbled in multiple myths are also going to be recognizable crossover characters in this universe.

And in the end, of course, Atalanta was the one to kill it. That’s why this team-up movie is called Atalanta 2.

Herakles 3: God of Olympus

Because before the universe hits its finale, we need a pay-off for the man who started it all.

Last time we saw him, in a post-credit scene, he was holding his recent lover Deianira and being happy. Which, again, Hera does not like.

Deianira accidentally kinda kills him with the poisoned blood of Nessus.

He has to fight. Again. Has to prove himself. Again.

But at the end of this, there is an actual happy ending waiting for him as he is granted godhood and falls in love with the goddess Hebe to live happily ever after on Olympus.

Chiron: Trainer of Heroes

The third and maybe strongest of the team-up movies. The grand finale of the series, you could say. Also the only original idea I’m pitching here; all others are just the myths as they happened, put into a chronological order that would make for a cool movie-verse in my eyes.

The best place for this to start is Chiron.

Because the thing is, Chiron trained and raised most heroes.

Herakles, Theseus, Jason, Achilles, Patroclus, Phoenix, Ajax.

Let’s say the trainer of heroes got into a little trouble and his wife Chariclo - daughter of Apollo and mountain-nymph and also the one who did the whole raising of the heroes while Chiron only did the training because honestly everyone keeps forgetting that this centaur gets babies dumped in his lap and not teens and that it requires more than just hand-to-hand and sword training and that he had a wife who did all of that - assembles a team of the above named heroes to save their trainer, featuring cute flashbacks to them as kids during training.

#Greek Mythology#Shared Universe#Movie Idea#Achilles#Herakles#Theseus#Jason#Odysseus#Atalanta#Orpheus#all the heroes#Franchise Idea#I really want this to happen so badly

240 notes

·

View notes

Text

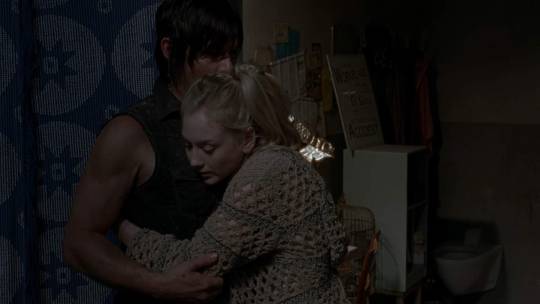

Genekie: A Familiar, But Missing Romance

In my last big Genekie meta (X), I broke down Genekie’s dynamic, the root of that dynamic, and its similarities to Bethyl. The big ships of the show, as of now, are Gleggie (r.i.p.), Richonne, Bethyl, and Carzekiel. Genekie will probably appear on that line-up next season. Season 8 will cover the All Out War arc, which will bring characters closer, and accelerate relationships already accelerated by the apocalypse. It will be the Season of Love™. @bethgreenewarriorprincess, @flying–forward, and I (also known as the Genekie Support Group) were discussing Genekie a few weeks ago. Christy and I both agreed that the Genekie hug hit us hard. It was reminiscent of the Bethyl hug from 4x01.

When we watched 7x11, we both felt an immediate shift in Eugene’s character dynamic, and suddenly possibilities had opened up. So many parallels have been made between Abraham and Frankie, in relation to Eugene, for a reason. Eugene was most loyal to Abraham, his protector and friend, and now his loyalty will shift to Frankie. He will become the protector for the woman whom he will fall in love with. We’ve never seen anyone interact with Eugene on that physical-emotional level, just as we’d never seen anyone interact with Daryl like that until Beth. Eugene did hug Abraham in 6x16, but that was because Eugene didn’t know if he would come back. He was going to sacrifice himself so the group could get Maggie to the Hilltop. Frankie initiated the contact, and she is nearly a stranger, and one of Negan’s wives. Not only a Savior, but inappropriate contact with her would carry heavy punishment. And yet Eugene let her hug him, and he didn’t flinch from her touch. He may have grunted when she smiled up at him, but he also had the trace of a smile, as she softened his hard exterior. Overall, Franke is the only person who’s been like that with him.

7x11 was like a dark mirror of 4x01 in certain ways, especially since the Sanctuary has elements of the prison. The Genekie hug is a mirror of the Bethyl hug, born out of wanting to share joy instead of shared grief. 7x11 also mirrors 4x12. Frankie called him “Dr. Eugene” as he set up the experiment, paralleling Beth calling Daryl, “Mr. Dixon.” One born out of interest, the other out of anger. bethgreenewarriorprincess even described Genekie’s experience at the Sanctuary as being “stuck in a ‘suck-ass camp’ together. On another level, Eugene and Frankie are stuck in their own version of the country club.

In the episode commentary, Angela Kang explained that Scott Gimple created a whole backstory for the former inhabitants of the country club (X). The phrase “Welcome to the Dogtrot” referred to the workers who became slaves of the country club members. There was a class struggle. While this Easter egg foreshadowed Beth’s arc at Grady, the egg also alludes to the Saviors, which Grady was a rehearsal for. The country club workers were the people “who ate shit” at Pine Vista.

Frankie represents the “Rich Bitch” at the Sanctuary. She is part of its upper class, and it’s not unreasonable that lower-level Saviors would resent her or write her off for marrying Negan. She chose him, without the need to, unlike Amber, who needed meds for her mother. There is also an element of sexual violence, as Negan rapes wives like Amber through coercion.

Frankie makes me think of Beth. It takes a strong person to remain so kind, especially in the Sanctuary. And someone who actually really has the will to survive, and to LIVE, to an extent, by becoming a wife. Because even though she’s married to Negan, she lives a pretty good life in terms of comfort and luxury. With that in mind, I also think that Frankie’s belief in the world was compromised a long time ago, hence why she hasn’t left the Sanctuary (yet). She needed to believe that Eugene was a good man, explaining why she appealed specifically to his goodness to help “Amber”. Furthermore, Elyse DuFour mentioned in an interview that Frankie doesn’t really care about anyone except the other wives. They’ve all been hurt by Negan one way or another, and they’re each other’s family. Frankie is the kind of character who doesn’t cry anymore.

As Frankie inspires Eugene to find his courage, he might inspire to find her belief and faith in the world and in people. He’s the good man that she needs in her life.

In summary, Genekie is a dark mirror of Bethyl, had they never gotten out of country club. All of Gimple’s ships go back to Bethyl, the OTP of the show. From a Team Delusional standpoint, so many parallels wouldn’t be showing up unless Bethyl was important to the story and to the writers, specifically Gimple. He is the show runner, and the man responsible for Richonne, Carzekiel, and Genekie. All of those ships parallel each other and parallel Bethyl.

From a narrative standpoint, Genekie exists to round out the story in terms of romance. In an interview, Elyse mentioned a possible romantic development between Frankie and Eugene (X). The quote always stood as strange to me because it doesn’t make sense for the actress of a tertiary character to think a romance would be possible, with a main character like Eugene, unless it was already there. Elyse probably dropped her comment about a “maybe not, maybe” romantic development because she’s discussed Frankie’s arc with the writers. She seeds the possibility while also keeping said possibility ambiguous. It’s reminiscent of the kind of statements Emily would give about Bethyl (X). Even with all of its parallels to Bethyl, Genekie would still be a fresh storyline for the audience. The relationship would be illicit, because Frankie is married and married to Negan. She could not leave him for Eugene, and so they would be forced to fall in love at a distance, hiding their true feelings. As I mentioned in a past meta (X), Genekie would be darkly ironic as Eugene and Frankie are both professional liars. Eugene lied about the cure and being a scientist, while Frankie lies about her feelings for Negan. They live their lies, and if they fall in love, then they would have to lie to protect the other. Cue the angst. The show has never done a forbidden romance, as the apocalypse kind of wipes out the reasons for something to be “forbidden”. When society falls apart, morals adapt. But Gimple is all about romance tropes, evident by how he has developed his other ships:

Bethyl: The Love That Defies the Odds, That Defies Death, and is the Damn Romance Novel. Hades/Persephone, Beauty and the Beast, the Princess and her Knight.

Richonne: The Couple That Slays Together Stays Together, Freyja/Frigga and Odr/Odin. (X)

Carzekiel: the King and his Queen, through a Hades/Persephone lens.

Gleggie: Star-crossed lovers. Because even though their relationships is from the comics, I just know that Gimple added the line “Maggie I’ll find you”. That bit is not in the comics, and that scene was pretty much directly ripped from the comics. It was added for a reason, and I think it’s because Gimple isn’t a fucking pseudo-intellectual nihilist like Kirkman. Odysseus/Penelope. (X)

That leaves Genekie. Forbidden love goes back to Greek mythology, in Western culture. The most notable story is that of Pyramus and Thisbe (X). They were a partial inspiration for Romeo and Juliet. In the myth, Pyramus and Thisbe live next door to each other, but they were forbidden to see each other let alone to marry. The couple made it work by speaking through a hole in their garden walls. Eventually they planned to run away together and were to meet at a tomb. Thisbe got to the tomb first, but she had to hide from a lioness, and she dropped her shawl in the process. The lioness, who just had killed an animal, nuzzled her shawl, bloodying it. Pyramus saw the shawl and thought the blood was Thisbe’s. He killed himself. When Thisbe saw what happened, she killed herself too.

Forbidden love stories include Romeo and Juliet (of course), Cleopatra and Mark Anthony, Anna Karenina, Tristan and Isolde. The list goes on, in fiction and in history. Genekie will balance out the relationships on the show, as they will be a different kind of power couple. They will be more like Bethyl, because Richonne and Carzekiel are more of the standard form of power couple. Genekie will be a story of two very different people completing each other, body and mind coming together, akin to the famous Leonard and Penny relationship from The Big Bang Theory. And knowing Gimple, he will find a way to incorporate mythical/archetypal traits into Genekie. I bet he will use Aphrodite and Hephaestus.

For those unfamiliar with Greek mythology, Aphrodite is the goddess of love and beauty and sex. She was born from sea foam, and Zeus married her to his son Hephaestus. Hephaestus was thrown from Mount Olympus when he was born, usually by his mother, due to his ugliness. The fall crippled one of his legs. Still, Hephaestus became a great engineer and the god of fire. Neither party loved the other, and Aphrodite was known for her affairs, most famously her affair with Ares, the god of war. If Gimple reverses the story, Frankie as Aphrodite would be married to Ares (Negan) and would fall in love with an awkward, unconventionally-attractive engineer. If you need further proof of this possibility, please also read this amazing piece on how Aphrodite and Hephaestus could be written as a love story: X.

Gimple is telling a modern epic, and he taps into our cultural, literary roots to codify his story. It is a fresh take on an age-old story of good versus evil, in which hope wars with fear and in which love conquers even the most insurmountable odds.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snake charmers: Medusa, Taylor Swift, and the prevalence of the serpentine woman

With the end of the Rep era upon us I figured I’d make my flagship post an essay I wrote about Taylor, Medusa, and the power of the snake woman.

Where were you when Kim Kardashian called Taylor Swift a snake?

In case you were living under a particularly large, particularly remote rock during this seminal moment in pop culture lore, here’s a refresher:

It’s July 2016 and Taylor Swift is fighting a war on two fronts. Her Instagram comments are flooded with snake emojis after a public breakup and copyright battle with Scottish DJ and producer Calvin Harris. Harris publicly accuses Swift of “trying to bury” him by revealing herself to be a co-writer on Harris’s hit “This Is What You Came For”. Meanwhile, in another corner of Twitter, Swift is fighting a second battle over Kanye West’s song “Famous”, where he claims “I feel like me and Taylor might still have sex / I made that bitch famous”. Swift maintains that, though West contacted her before the song was release, he never disclosed the full lyrics, namely the “bitch” line. West’s wife, Kim Kardashian West, gets involved and on July 17, National Snake Day, she administers a final blow in the form of a tweet: “Wait it's legit National Snake Day?!?!?They have holidays for everybody, I mean everything these days!” Kardashian West ended her tweet with a slew of snake emojis. Immediately concerned citizens began leaving thousands of snake emojis in Swift’s Instagram comments and, though Swift employed a St. Patrick-esque filter to drive the snakes out of her social media comments, the damage was done; the name Taylor Swift had become synonymous with “snake”.

Kardashian West’s tweet is probably the closest the 21st century will ever get to experiencing the Shot Heard Round the World. The tweet didn’t even mention Swift but it tapped into a collective understanding that Taylor Swift was a snake.

Snake imagery and folklore has existed in Western tradition in some form or another for millenia, though the meaning is as slimy and elusive as the real-life reptile. Each culture seems to have its own take on what serpents represent, whether they’re virtuous or evil, poisonous or benign.

But what does it really mean to be a snake?

Swift has reclaimed the snake motif and incorporated it into promotional material for her 2017 album reputation. Fans can buy snake rings from her website. They can wear snake t-shirts and buy concert date posters of snakes slithering through the skylines of America’s largest cities. During her reputation Stadium Tour shows, snake imagery was everywhere, from the snakeskin detail on her costumes to the giant inflatable cobras that appear periodically during her performance.

Swift has leaned into her public image as a snake woman, though she is hardly walking on new ground. Swift’s branding as a snake woman, as well as the circumstances surrounding that branding beg a comparison to the mother of all snake women, Medusa.

Even before Snakegate, Swift’s ~reputation~ was veering in a Medusa-like direction. Over the years, Swift’s tendency to write—sometimes critical—songs about her famous exes has made her a target of constant criticism. Her albums have been portrayed in much the same way Perseus describes the walk up to Medusa’s abode: eerily populated by a group of unsuspecting men frozen for all to see in the very moment they had the misfortune of coming into contact with her.

The tale of Medusa is famously recounted in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, though, of course different versions exist. In Ovid’s telling, Medusa is one of three sisters and the only mortal among them. Medusa’s beauty—bolstered by mythically great hair—catches Neptune’s attention and he rapes her in Minerva’s temple. This angers Minerva, who takes revenge upon Medusa. Medusa’s beautiful hair is “woven through with snakes”. She lives in solitude, accompanied only by her snakes and statues until the day Perseus arrives and decapitates her in her sleep. For modern readers, the myth’s blatant victim-blaming is hard to ignore, especially now in the midst of the #MeToo movement.

Medusa is the western canon’s premiere snake woman, but her relationship with the scaly creatures is intriguingly complicated. Medusa is dangerous, yes, but it is not her scalpful of snakes that makes her so. Medusa’s true weapon is her stare, which turns men into solid stone. The snakes, therefore, do not represent danger or violence or even death. Instead, they represent a loss of status and a lapse in justice.

Indeed, Swift’s reputation is built with these same materials. “My castle crumbled overnight...they took the crown but it’s alright,” she sings in “Call It What You Want”, acknowledging the massive hit her popularity took in 2016. Earlier in the album, on “I Did Something Bad”, Swift laments the unfairness of the public trial that played out on the internet, “They’re burning all the witches even if you aren’t one.” The bridge of reputation’s lead single “Look What You Made Me Do” blatantly showcases Swift’s estrangement from the world: “I don’t trust nobody and nobody trusts me”.

With reputation Swift gives us something completely missing from Metamorphoses: the snake woman’s perspective. Notably in Metamorphoses, Medusa’s origin story is told from the perspective of her murderer for the entertainment of others. Medusa’s rape is merely a plot point designed to bolster Perseus’s heroic narrative. Medusa is never allowed the opportunity to speak for herself or take control of her own narrative. On reputation, however, Swift turns the tables on the one-sided snake woman narrative and allows for a more fair interpretation.

Recently, there has been a feminist push to reevaluate the stories and circumstances of the women who populate Greek myth. This charge has been led by Madeline Miller, author of Circe, and Emily Wilson, the first female translator of The Odyssey. Miller and Wilson have repeatedly analyzed the role of translatorial and reader bias in our understanding of mythological women like Medusa.

Since most 21st century readers can’t read Homer in the original Ancient Greek, they lack the tools to critically assess semantic choices influenced by the translator’s own cultural moment and personal biases. These scruples may seem small, but they quickly add up. And, as Swift has reiterated, a bad reputation is hard to shake.

In her detailed translator’s note, Wilson gestures many different places in her translation where she has attempted to correct established misogynist language that has been present in translations of Homer’s poetry for centuries. “I try avoiding importing contemporary types of sexism into this ancient poem, instead shining a clear light on the particular forms of sexism and patriarchy that do exists in the text,” Wilson writes.

In her note and in public appearances, Wilson has particularly mentioned her handling of the scene where Telemachus, Odysseus’s son, executes women accused of sleeping with Penelope’s suitors. Previous translations have described them as maids or servants but Wilson chose to translate the term as “slave” in order to reiterate the lack of agency and freedom the women had.

In a way, reputation is doing the same work. Like Miller and Wilson, Swift is reevaluating an established understanding of an ancient myth, in this case Medusa, and presenting it from an entirely new perspective.

reputation shows that Miller and Wilson’s efforts to cast a critical eye upon the ingrained misogyny we’ve taken for granted in ancient texts are able to expand outside the realm of classical studies. We can apply this same framework to contemporary pop cultural narratives with the same result.

Though the parallels between the Medusa myth and reputation are most likely coincidental, they should prompt us all to ask, “Why?” Why is it so damaging to be labeled a snake woman? Why is that a symbol that must be reclaimed? Why have we allowed this to go on for so long?

Works Cited

Homer. The Odyssey. Edited by Emily R. Wilson, W.W. Norton Et Company, Inc., 2018.

Ovid. Metamorphoses. Edited by Charles Martin, W.W. Norton & Co., 2005.

Swift, Taylor. Reputation, Taylor Swift. 2017.

#Taylor Swift#Reputation#Medusa#Ovid#Metamorphoses#Madeline Miller#The Odyssey#Homer#Emily Wilson#Snake lady

0 notes

Text

Patriarchy and Matriarchy -- Old Testament and Related Studies -- HUGH NIBLEY 1986

Patriarchy and Matriarchy

My story begins with Adam and Eve, the archetypal man and woman, in whom each of us is represented. From the most ancient times their thrilling confrontation has been dramatized in rites and ceremonies throughout the world, as part of a great creation-drama rehearsed at the new year to celebrate the establishment of divine authority on earth in the person of the king and his companion. There is a perfect unity between these two mortals; they are “one flesh.” The word rib expresses the ultimate in proximity, intimacy, and identity. When Jeremiah speaks of “keepers of my tsela (rib)” (Jeremiah 20:10), he means bosom friends, inseparable companions. Such things are to be taken figuratively, as in Moses 3:22 and Genesis 2:22, when we are told not that the woman was made out of the rib or from the rib, but that she was the rib, a powerful metaphor. So likewise “bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh” (Genesis 2:23), “and they shall cleave together as one flesh”—the condition is that of total identity. “Woman, because she was taken out of man” (Moses 3:23; italics added) is interesting because the word woman is here mysteriously an extension of man, a form peculiar to English; what the element wo– or wif– means or where it came from remains a mystery, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. Equally mysterious is the idea of the man and woman as the apple of each other’s eye. Philological dictionaries tell us that it is a moot question whether the word apple began with the eye or the fruit. The Greek word is kora or korasion, meaning a little girl or little woman you see in the eye of the beloved; the Latin equivalent is pupilla, from pupa or little doll, from which we get our word pupil. What has diverted me to this is the high degree to which this concept developed in Egypt in the earliest times. The Eye of Re is his daughter, sister, and wife—he sees himself when he looks into her eye, and the other way around. It is the image in the eye that is the ideal, the wdjat, that which is whole and perfect. For “it is not good that man should be alone”; he is incomplete by himself—the man is not without the woman in the Lord. (See 1 Corinthians 11:11.)

The perfect and beautiful union of Adam and Eve excited the envy and jealousy of the Evil One, who made it his prime objective to break it up. He began by making both parties self-conscious and uncomfortable. “Ho, ho,” said he, “you are naked. You had better run and hide, or at least put something on. How do you think you look to your Father?” They had reason to be ashamed, because their nakedness betrayed their disobedience. They had eaten of the forbidden fruit. But Satan wanted to shock them with his pious show of prudish alarm—he had made them ashamed of being seen together, and that was one wedge driven between them.

His first step (or wedge) had been to get one of them to make an important decision without consulting the other. He approached Adam in the absence of Eve with a proposition to make him wise, and being turned down he sought out the woman to find her alone and thus undermine her resistance more easily. It is important that he was able to find them both alone, a point about which the old Jewish legends have a good deal to say. The tradition is that the two were often apart in the Garden engaged in separate tasks to which each was best fitted. In other words, being one flesh did not deprive either of them of individuality or separate interests and activities.

After Eve had eaten the fruit and Satan had won his round, the two were now drastically separated, for they were of different natures. But Eve, who in ancient lore is the one who outwits the serpent and trips him up with his own smartness, defeated this trick by a clever argument. First she asked Adam if he intended to keep all of God’s commandments. Of course he did! All of them? Naturally! And what, pray, was the first and foremost of those commandments? Was it not to multiply and replenish the earth, the universal commandment given to all God’s creatures? And how could they keep that commandment if they were separated? It had undeniable priority over the commandment not to eat the fruit. So Adam could only admit that she was right and go along: “I see that it must be so,” he said, but it was she who made him see it. This is much more than a smart way of winning her point, however. It is the clear declaration that man and woman were put on the earth to stay together and have a family—that is their first obligation and must supersede everything else.

Now a curse was placed on Eve, and it looked as if she would have to pay a high price for taking the initiative in the search for knowledge. To our surprise the identicalcurse was placed on Adam also. For Eve, God “will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception. In sorrow shalt thou bring forth children.” (Genesis 3:16.) The key is the word for sorrow, atsav, meaning to labor, to toil, to sweat, to do something very hard. To multiply does not mean to add or increase but to repeat over and over again; the word in the Septuagint is plethynomai, as in the multiplying of words in the repetitious prayers of the ancients. Both the conception and the labor of Eve will be multiple; she will have many children. Then the Lord says to Adam, “In sorrow shalt thou eat of it all the days of thy life” (that is, the bread that his labor must bring forth from the earth). The identical word is used in both cases; the root meaning is to work hard at cutting or digging; both the man and the woman must sorrow and both must labor. (The Septuagint word is lype, meaning bodily or mental strain, discomfort, or affliction.) It means not to be sorry, but to have a hard time. If Eve must labor to bring forth, so too must Adam labor (Genesis 3:17; Moses 4:23) to quicken the earth so it shall bring forth. Both of them bring forth life with sweat and tears, and Adam is not the favored party. If his labor is not as severe as hers, it is more protracted. For Eve’s life will be spared long after her childbearing—”nevertheless thy life shall be spared”—while Adam’s toil must go on to the end of his days: “In sorrow shalt thou eat of it all the days of thy life!” Even retirement is no escape from that sorrow. The thing to notice is that Adam is not let off lightly as a privileged character; he is as bound to Mother Eve as she is to the law of her husband. And why not? If he was willing to follow her, he was also willing to suffer with her, for this affliction was imposed on Adam expressly “because thou hast hearkened unto . . . thy wife and, hast eaten of the fruit.”

And both their names mean the same thing. For one thing they are both called Adam: “And [he] called their name Adam” (Genesis 5:2; italics added). We are told in the book of Moses that Adam means “many,” a claim confirmed by recent studies of the Egyptian name of Atum, Tem, Adamu. The same applies to Eve, whose epithet is “the mother of all living.”

And what a woman! In the Eden story she holds her own as a lone woman in the midst of an all-male cast of no less than seven supermen and angels. Seven males to one lone woman! Interestingly enough, in the lost and fallen world that reverses the celestial order, the ratio is also reversed, when seven women cling to one righteous man. This calls for an explanation: God commanded his creatures to go into the world “two and two,” and yet we presently find the ancient patriarchs with huge families and many wives. What had happened? To anticipate our story, it so happened that when the first great apostasy took place in the days of Adam and Eve, the women, being wise after the nature of Mother Eve, were less prone to be taken in by the enticements of the Cainite world. For one thing they couldn’t—they were too busy having children to get into all that elaborate nonsensical mischief. Seven women could see the light when only one man could.

The numerical imbalance in the Garden is caused by the presence of all the male heavenly visitors on the scene. Why are all the angels male? Some very early Christian writings suggest an interesting explanation. In the earliest Christian poem, “The Pearl,” and in recently discovered Mandaean manuscripts (the Berlin Kephalia), the Christian comes to earth from his heavenly home, leaving his royal parents behind, for a period of testing upon the earth. Then, having overcome the dragon, he returns to the heavenly place, where he is given a rousing welcome. The first person to greet him on his return is his heavenly mother, who was the last one to embrace him as he left to go down to earth. “The first embrace is that which the Mother of Life gave to the First Man as he separated himself from her in order to come down to earth to his testing.” So we have a division of labor. The angels are male because they are missionaries, as the Church on the earth is essentially a missionary organization; the women are engaged in another, but equally important, task: preserving the establishment while the men are away. This relationship is pervasive in the tradition of the race—what the geographer Jean Bruhnes called “the wise force of the earth and the mad force of the sun.” It is beautifully expressed in an ode by Sappho:

The evening brings back all the things that the bright sun of morning has scattered You bring back the sheep, and the goat and the little boy back to his mother.

Odysseus must wander and have his adventures—it is his nature. But life would be nothing to him if he did not know all the time that he had his faithful Penelope waiting for him at home. She is no stick-in-the-mud, however, as things are just as exciting, dangerous, and demanding at home as on the road. (In fact, letters from home to missionary husbands are usually more exciting than their letters from the field.)

So who was the more important? Eve is the first on the scene, not Adam, who woke up only long enough to turn over to fall asleep again; and then when he really woke up he saw the woman standing there, ahead of him, waiting for him. What could he assume but that she had set it all up—she must be the mother of all living! In all that follows she takes the initiative, pursuing the search for ever greater light and knowledge while Adam cautiously holds back. Who was the wiser for that? The first daring step had to be taken, and if in her enthusiasm she let herself be tricked by the persuasive talk of a kindly “brother,” it was no fault of hers. Still it was an act of disobedience for which someone had to pay, and she accepted the responsibility. And had she been so foolish? It is she who perceives and points out to Adam that they have done the right thing after all. Sorrow, yes, but she is willing to pass through it for the sake of knowledge—knowledge of good and evil that will provide the test and the victory for working out their salvation as God intends. It is better this way than the old way; she is the progressive one. She had not led him astray, for God had specifically commanded her to stick to Adam no matter what: “The woman thou gavest me and commanded that she should stay with me: she gave me the fruit, and I did eat.” She takes the initiative, and he hearkens to her—”because thou hast hearkened to thy wife.” She led and he followed. Here Adam comes to her defense as well as his own; if she twisted his arm, she had no choice either. “Don’t you see?” he says to the Lord. “You commanded her to stay with me. What else could she do but take me along with her?”

Next it is the woman who sees through Satan’s disguise of clever hypocrisy, identifies him, and exposes him for what he is. She discovers the principle of opposites by which the world is governed and views it with high-spirited optimism: it is not wrong that there is opposition in everything, it is a constructive principle making it possible for people to be intelligently happy. It is better to know the score than not to know it. Finally, it is the “seed of the woman” that repels the serpent and embraces the gospel: she it is who first accepts the gospel of repentance. There is no patriarchy or matriarchy in the Garden; the two supervise each other. Adam is given no arbitary power; Eve is to heed him only insofar as he obeys their Father—and who decides that? She must keep check on him as much as he does on her. It is, if you will, a system of checks and balances in which each party is as distinct and independent in its sphere as are the departments of government under the Constitution—and just as dependent on each other.

The Dispensation of Adam ended as all great dispensations have ended—in a great apostasy. Adam and Eve brought up their children diligently in the gospel, but the adversary was not idle in his continued attempts to drive wedges between them. He had first to overcome the healthy revulsion, “the enmity,” between his followers and “the seed of the woman,” and he began with Cain, who went all the way with him “for the sake of getting gain.” “And Adam and Eve blessed the name of God, and they made all things known unto their sons and their daughters. And Satan came among them, saying: Believe it not. . . . And men began from that time forth to be carnal, sensual, and devilish.” (Moses 5:12—13.) Even in the garden mankind were subject to temptation; but they were not evil by nature—they had to work at that. All have fallen, but how far we fall depends on us. From Cain and Lamech through the Watchers and Enoch to the mandatory cleansing of the Flood, the corruption spread and enveloped all the earth. Central to the drama was a never-ending tension and conflict between the matriarchal and patriarchal orders, both of which were perversions. Each has its peculiar brand of corruption.

The matriarchal cultures are sedentary (remember that the mother stays home either as Penelope or as the princess confined in the tower), that is, agricultural, chthonian, centering around the Earth Mother. The rites are mostly nocturnal, lunar, voluptuous, and licentious. The classic image is that of the great, rich, corrupt, age-old, and oppressive city Babylon, queen of the world, metropolis, fashion center, the super mall, the scarlet woman, the whore of all the earth, whose merchants and bankers are the oppressors of all people. Though the matriarchy makes for softness and decay, beneath the gentle or beguiling or glittering exterior is the fierce toughness, cunning, and ambition of Miss Piggy, Becky Sharp, or Scarlett O’Hara.

The patriarchal order lends itself to equally impressive abuses. It is nomadic. The hero is the wandering Odysseus or knight errant, the miles gloriosus, the pirate, condottière, the free enterpriser—not the farmer tied to wife and soil, but the hunter and soldier out for adventure, glory, and loot; not the city, but the golden horde, the feralis exercitus that sweeps down upon the soft and sedentary cultures of the coast and the river valley. Its gods are sky gods with the raging sun at their head. Its depradations are not by decay but by fire and sword. As predatory and greedy as the matriarchy, it cumulates its wealth not by unquestioned immemorial custom but by sacred and self-serving laws. The perennial routine calls for the patriarchal tribes of the mountains and the steppes to overrun the wealthy and corrupt cities of the plain only to be absorbed and corrupted by them in turn, so that what we end up with in the long run is the worst of both cultures.