#not a lot of overlap between them as writers but they do love their Catholic references and tbh I can easily see jrrt getting distracted

Text

one thing I like about tazmuir as an author is that at any given time she will be like "here is a character," and I will think "that's nice, but I don't care. please return me to my beautiful Gideon" and then she'll be like "no. look at this other character under a microscope. they are so fucked up and full of love in such specific ways. probably they are bad at sex also." and I make a shocked face and welcome them into the pantheon in my heart, still waiting to hear from my beautiful gideon, at which point tazmuir will show me another character. and then.

#who is forcing me to care about Babs like this#jrr tolkien#that's who#not a lot of overlap between them as writers but they do love their Catholic references and tbh I can easily see jrrt getting distracted#writing a massive adventure for an unpopular minor character's implied relatives

4K notes

·

View notes

Note

personally i love the fact that we both love fallout but our zones of focus have essentially no overlap. i always used to roll my eyes when paranormal stuff came in because i felt it got in the way of the political worldbuilding but seeing your enthusiasm has helped me see what the appeal of the supernatural fallout stuff is and im a lot more open to it than before

thanks for writing! my pulp approach is motivated by the following factors

i'm fascinated with supernatural and occult history & fallout is a great science fiction context to play with those ideas without beginning to suggest they are real

i'm fascinated with apocrypha, mistranslation, misunderstood history, etc. and became infinitely curious about fallout's origins in Wasteland and Canticle, and how different writers approached the setting.

i'm fascinated with the parallel between catholic canon and ip canon. the general comparison between scripture, legend, and pop culture.

i designed characters who travel everywhere and document anomalies so i could immersively roleplay while doing research.

a lot of fallout spaces are dominated by bullshit canon trolls who only talk about enclave power armor & consistency-gate any and all creative discussion

i became determined to build a watsonian model for the setting based on canon that reliably vibe checks them out of my face.

pylon v13 might as well have dared me. it is nothing but a giant portal to the cancelled fallout mmo, built by a character from it. one can deny it, but that's transparent. beth dryly wrote and depicted this in the most recent game. as soon as you ignore it, you're farther from canon and author intent than me. which is fine. it's all fiction, after all. :+)

if people are going to treat fallout as a military fantasy rather than a satire of american imperialism then by god under no circumstances am i going to let them treat their version of fallout as "realistic" or "definitive"

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Neocolonialism and Indigenous Communities in the Americas

Through the lens of neocolonialism, it is important to point out that this form of colonialism is mostly dependent on cultural forces and ideas in order to maintain the power and influence of white settlers (or even non-white settlers that have access to a lot of power, money, and influence; corporate capitalists, basically).

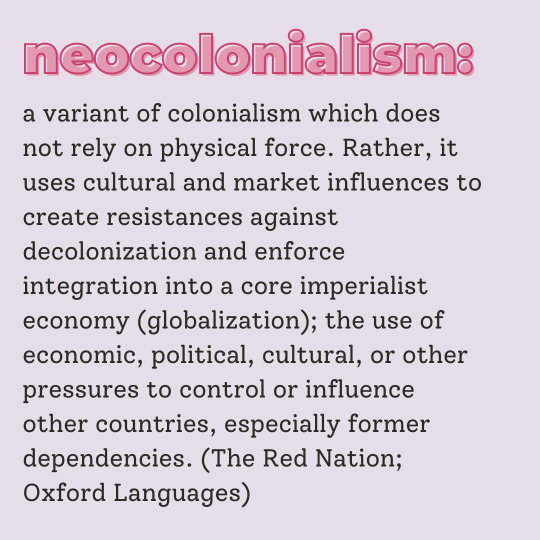

neocolonialism: a variant of colonialism which does not rely on physical force. Rather, it uses cultural and market influences to create resistances against decolonization and enforce integration into a core imperialist economy (globalization); the use of economic, political, cultural, or other pressures to control or influence other countries, especially former dependencies. (The Red Nation, Oxford Languages) [for a more expansive definition of neocolonialism and it's characteristics, please check out my other blog post here]

I would say that some of the largest of neocolonial influences are the systems and/or institutions that embrace capitalism (specifically racial capitalism), resource exploitation, labor exploitation (that happen as a result of racial capitalism), and the persisting influence of the Christian religion via religious institutions (like the Catholic Church and other religious schools). Neocolonialism intersects quite literally with the structure of the prison industrial complex (but I will talk about that a bit at the end of this blog post and write a whole blog post dedicated to those specific intersections). It is also important to note that neocolonialism argues that the systems of the colonial era are internalized in our bodies. In order for these systems to continue to function, these institutions must work to internalize these cultural forces/ideas (like basically low key brain-washing to be honest) that affect our self-concept, the relationship with our bodies, and our access to resources.

Capitalism, labor exploitation, and parallels today from the "Colonial" era

There is a connection between how labor exploitation plays out today and the exploitative history of slavery during the colonial era, a lot of it is apparent in various industries (like the fashion/textile industry, prison labor, etc.) But in this blog post I'm going to mostly talk about the exploitative labor practices of the Hollywood/film industry and how they exploit indigenous communities through labor and the use of their land. I will also be talking about the capitalization of other natural resources such as water, which is a huge problem indigenous communities are facing today.

An example of the exploitative labor practices in the film industry can be found through the analysis of the film Even the Rain. In Fabrizio Cilento's article "Even the Rain: A Confluence of Cinematic and Historical Temporalities, Cilento breaks down how the film "takes a metacinematic approach to the the story of a Mexican film crew in Bolivia shooting an historic drama on Christopher Columbus's conquest. With the water riots as a background, Bollaín uses different cinematic styles to establish disturbing parallels between old European imperialism, the recent waves of corporate exploitation,... and the exploitation of Bolivian actors for the benefit of the global film industry.... Bollaín warns that these productions can fall into a colonialist dynamic by reproducing the imbalances between the 'visible' countries in the global film market, and 'invisible' countries whose native actors and visually appealing locations are exploited...." It is important to note how the persistence of capitalism and the exploitation of resources (whether that be land or labor) continue to work against decolonization and creates similar power imbalances between indigenous communities and corporate capitalists that allude to the colonial era. This is also a prime example of how there is a continued rift between the indigenous people's relationship to the land, especially through the limited access to water.

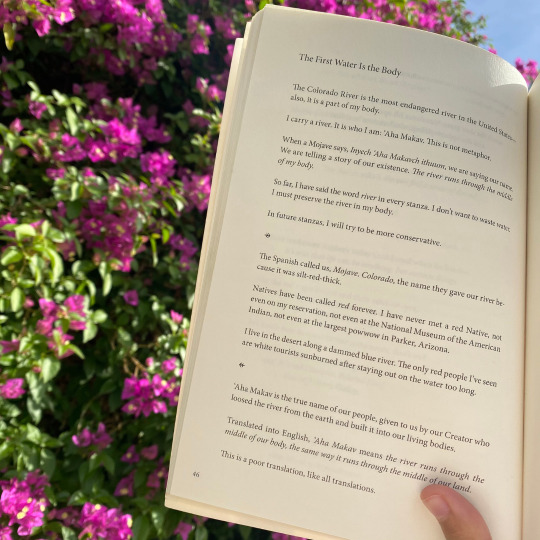

(Postcolonial Love Poem by Natalie Diaz)

So, I would like to make the point that capitalism and corporate interests play a huge role in working against decolonization. We do not live in a "Postcolonial" world, but rather, a neocolonial world that continues to exploit indigenous communities for their (quite frankly already limited) resources. Today, many Native Americans/Indigenous people have trouble accessing water like the First Nations in Canada, the indigenous tribes in the United States, and indigenous communities in Latin America and the Caribbean (whom are 10 to 25 percent less likely to have access to piped water than the region’s Non-Indigenous populations according to this page/report).

For more in depth discussion about the water and land crises indigenous communities are currently facing. All My Relations podcast, which is a podcast run by Matika Wilbur (a visual storyteller/photographer from the Swinomish and Tulalip peoples of coastal Washington) and Adrienne Keene (a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and blogger that discusses cultural appropriation and stereotypes of Native peoples in fashion, film, music, and other forms of pop culture, and a faculty member in American Studies and Ethnic Studies at Brown University.), have done an episode about this topic named Healing The Land IS Healing Ourselves in which they discuss with Kim Smith (a Diné woman, community organizer, citizen scientist, activist, water protector, entrepreneur, and writer) about indigenous' communities relationship with the land, how it relates to the current environmental and water crisis, and the relationship it has with healing our bodies, in which Smith discusses that "violence on the land is violence on our bodies".

The Catholic Church, colonialism, sexuality, and it's influence today

When we're talking about colonialism in the Americas and the remnants of the colonial era today, the conquest of indigenous sexuality/eroticism via the Catholic Church and the repression of indigenous sexuality has played a huge part in colonialism and is still an issue today that perpetuates the erasure of indigenous identity.

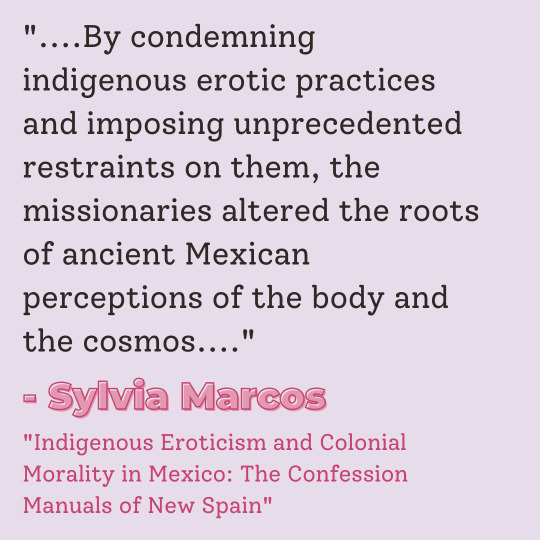

In Sylvia Marcos's article "Indigenous Eroticism and Colonial Morality in Mexico: The Confession Manuals of New Spain" Marcos explains that "....By condemning indigenous erotic practices and imposing unprecedented restraints on them, the missionaries altered the roots of ancient Mexican perceptions of the body and the cosmos...." Marcos further unpacks this through probes of confession manuals from the colonial era "....The confession manuals of Molina, Baptista, Serra, and others seem to indicate the missionaries' uneasiness over the diversity of sexual pleasures enjoyed by the souls in their charge. The priests had to repeatedly describe their limited idea of sexuality so that the vital Indians could understand that what for them was often a link with the gods was, in their new religion, always a sin, fault, or aberration.... The morality of negation and abstinence propagated by the missionaries became one more weapon used in the violent process of violent acculturation...." It's important to point out that the repression of the sexual pleasures of indigenous peoples has contributed to the erasure of indigenous identity, especially since they considered it as a means of connecting to their gods. This was used as a weapon to conquer indigenous people's bodies through shame and disconnection from their bodies and spiritual practices.

This is still an issue that persists today, this article by the Washington Post, talks about how transgender Native Americans experienced disproportionately higher rates of rejection by immediate family. It also talks about the state-sponsored Christian schools that have affected indigenous for generations in the United States. So, basically the expansion of Christianity/Catholicism culturally and institutionally and the repression of indigenous sexuality has contributed to the erasure of indigenous identity. And indigenous people that fall outside of the gender binary experience stigma still to this day, which perpetuates colonialism.

To further build upon this point and how to begin explaining the intersection of this with prison abolition and the experience of being Black and/or BIPOC in an imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchal society, Estelle Ellison, a Black Trans disabled writer and transformative justice practitioner, in their essay "Gender, Time, and Other Methods of Policing the Body", Ellison unpacks the intersections between exploitative racial capitalism and how it connects to gender, time, and sexuality, and also explains how it is connected to being policed through our bodies by stating that "By design, each of us is expected to participate in gendering other people's bodies...." and that "....of all the possible ways that a person may live their life at any given moment, the infinite combinations of features, experiences, aspirations, and expressions; gender attempts to reduce our possible identities by half. But half of infinity is still infinity..." Ellison also talks about how time has been colonized (via capitalism through wage labor) and is "made possible by overlapping systems of white supremacy, anti-blackness, patriarchy, ableism, misogyny, transphobia, homophobia, exploitation, and countless other forms of oppression..."

instagram

Ellison's analysis of the intersecting systems of neocolonialism explains how these systems are internalized in our bodies and how it is connected to exploitation (whether that be from our bodies some other form under these systems) and that we are being policed through our bodies due to societal, cultural, or institutional pressures, such as the prison industrial complex and the military industrial complex, or I would argue through religious beliefs.

Do you enjoy my content?

If you find my content to be interesting, please consider donating (but only if you can/would like/able to) so I can continue to post content with free resources and/or low-cost and accessible resources :)

Venmo: @Rebecca-Hiraheta

CashApp: $RebeccaHiraheta

Or if not, please feel free to support me by giving me a follow here or my other social media accounts

insta: @beccuhboo

personal blog: @beccuhboo

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Looking at the posts I’ve accumulated so far for #500 reasons and counting, I realized I need to frame the various subjects I’m tackling. I’d rather post more quotes than original posts, but the trouble with a complicated history like the Reformation (and the internet in general) is taking things out of context causes problems. To do this right, we need a clear conceptual framework in which to lay those quotes (and my inevitable commentary on them). So while in my first post I talked about where I’m coming from personally, in this post, call it intro 2.0, let’s lay out some history and approach parameters.

Let’s get the approach parameters out of the way first:

A) I’m trained in theology, not history, and I’m blogging about this as someone learning, not an expert. B) please charitably correct me (with sources!) if I get something wrong, but C) we should go into this realizing there’s a lot of room for disagreement (as you’ll see if you finish reading this post). D) I always try to represent the source I’m summarizing/working from accurately. That means: D-1) if you disagree with something I say, let’s first go back to the source and make sure I’m conveying it as they said it, and D-2) A good debater should understand the opposing POV so well that they can word their opponent’s argument to the satisfaction of their opponent. If I misrepresent an argument, it is not intentional. Please bring it to my attention and we’ll work it out.

That said, now we can talk about bias. If we’re going to talk about the Reformation, its causes and effects, how it influenced our civilization and still affects people today - even, yes, all those pesky theological “details” many would say no one cares about and don’t matter anymore! - then we need to ask some pointed questions: Just what do we mean by the Reformation? Whose version of the Reformation and its legacy is correct? What exactly is it, septembersung, that you’re taking issue with and arguing against?

Well, if you ask three historians “what happened,” you’ll get thirty answers...

To a large extent, Catholics, Protestants, and secular historians tell the story of medieval Christianity (i.e., Catholicism) and the Reformation differently. Extremely differently. (There is a lot of overlap in some areas between Protestant and secular approaches, however.) You might think that “facts are facts,” but history isn’t primarily facts; history the story we tell ourselves about facts as we know them. Sometimes an assumption, or a “fact” that’s actually false, or a matter of opinion, or disputed, gets enshrined as truth, embedded in how the subject is approached and handed down, and then everything from that is skewed. (This is an exceptionally important point we will come back to frequently.)

Everyone has a bias; this is unavoidable. In this context, bias means “where you stand to see the rest of the world.” Everyone has to stand somewhere. What’s important is to be able to identify your bias and see how it affects the story as you’ve received it and as you tell it. And, equally importantly, to differentiate bias, a fact of being an individual human person, from prejudice, which in this context means unfair and probably incorrect negation of a point of view you don’t share. An illustration of the difference: A secular, that is, non-believing, historian writes a history of the Reformation. Their bias is that they are not Christian, neither Catholic or Protestant. Their prejudice is shown in privileging the Protestant side of the story. To pick just three examples of how that prejudice could play out: using slurs against Catholics, the Church, and Catholic beliefs; accepting Protestant claims about Catholicism and Christian history a priori, as factual premise, without investigation or explanation; taking it for granted, as an accepted truth that does not need proving, that the Reformation did the world a favor. Here’s the kicker: this is not an invented example, but a summary of a large swath of writings on the Reformation.

As you know, I’m Catholic; that’s my bias. You should ask yourself: what’s yours? Do you know how it affects what you’ve been taught and the way you perceive history and the world around you? What prejudice might you be participating in that you don’t even realize is a prejudice?

(Sidebar: In addition (and related to) to the bias issue: intense specialization and the ways history as a whole is conceived and taught has led to such an overabundance of “facts” and narratives, particularly about this stretch of history, that there is little cohesion, and simply so much that trying to get a handle on the big picture can be completely overwhelming. You can drown in data and never learn a thing. (I always picture a cartoon child opening a stuffed closet and being buried in toys.) There’s a super good, though technical, layout of this problem in the introduction to Brad S. Gregory’s book The Unintended Reformation: How a Religious Revolution Secularized Society. I’m going to talk about that book a lot.)

The takeaway so far should be: the story of history that we receive varies by which community we’re in and which community delivered the story to us. I am not arguing that no objective truth about the matter exists. Quite the opposite: the first step to finding the truth is recognizing that what has been uncritically accepted as fact is an interpretation based on unreliable ideas. What I would most like to show my readers through this project, especially my Protestant readers, is that the reality and significance of the Reformation has been greatly misunderstood across the majority of communities. It’s pretty unlikely you’ll read my posts and come away deciding to convert to Catholicism. What is possible, and I hope it will happen, that you’ll walk away with a different understanding of Catholicism itself and Protestantism’s role the last 500 years of Christian history.

(Important sidebar: “Protestants” and “Protestantism” can only ever be a generalization. Not only do the vast number of denominations disagree with each other about Christian doctrine, on points big and small, but they have different biases, different understandings of history, different views of Catholicism - you get the idea. Whenever we use the term “Protesant/ism”, we should be aware that is a generalization.)

With all that said: here is a simplified summary of the story of the Reformation as popularly understood. What does that mean? It means this summary doesn’t cover everything, but it does encompass the broad spectrum of “not-Catholic” opinion, including both Protestant and secular views, which vary from each other and among themselves. And, of course, scholars and academia tend to acknowledge more nuance and complexity in the events of history than non-specialists. I spell this out to avoid tiresome arguments that I’m setting up a straw man or objections like “but I don’t believe that/all of that/that in that way,” etc. So as I said: the broad gist of the Reformation story as popularly understood by much of the world today:

The Catholic Church was pure institutionalized corruption. The hierarchy and religious lived immoral lives and oppressed the lay people. The Church was unChristian in deep and significant ways that were harming people. When Luther (et al) realized this, and that what the Church taught as religious truth was just a means of perpetuating its control and corruption, they got up and pushed, and the whole rotten structure came tumbling down. Suddenly the common people had access to the Bible, Jesus, real catechesis, spiritual and political freedom, genuine community, and (to use the modern terms) freedom and agency. There was some resistance, but the populace more or less welcomed the Reformation and joined in enthusiastically. The Reformation was a movement who’s time had come. With the suppression of “priestcraft,” superstitious practices and beliefs, and man-made ritual, the accumulated debris of centuries of ”Romish inventions” was swept aside and Christianity was given a clean slate. With this demolition of the Church, thus (believers would say) true, original Christianity triumphed; all the excess (at best) and demonic distractions (at worst) that led people away/separated people from Jesus was gone. With the demolition of the Church, thus (some believers and the vast majority of secular analyses would say) the road to modern society was paved: separation of church and state, the triumph of the thinking mind/rationality/logic over and against the deadening religious/organized religion influence, the growth of the sciences, freedom, tolerance, pluralism, etc.; the goods and wonders of the modern world exist because the iron grip of the Church was broken. Shedding the past launched us into the future. We’re lucky it’s over and done with and not relevant to us, in our secular society, anymore.

There’s just one problem with this narrative: it’s almost entirely wrong.

That’s a large chunk of what I’m taking issue with and arguing against.

I can’t guarantee this tag is going to be particularly organized or exhaustive - I decided to do this just a few days ago and, despite being a fast reader, can only cram in so much - but I’m going to examine these kinds of claims (in their originals, please note, not from my general gist summary) through my own writing and through sharing the content of scholars and writers more qualified than myself, to argue for a contrary thesis: Not only is that understanding of Catholicism and Christian history factually incorrect, but the Reformation was not an organic, welcomed event/process but rather a violent uprooting of a strong, loved religious tradition and past that cut Christians off from their heritage, fragmented and splintered society, blew the foundation out of Christendom (society as Christian society,) putting Western civilization on the road to society’s secularization, the marginalization and oppression of religion in the public life, and opened the door to the moral, rational, and political chaos we know today. I will absolutely address issues like “but wasn’t the Church corrupt?” but to a certain extent I don’t think that’s actually helpful until some of the fundamental falsehoods in what is generally assumed about the Reformation have been examined. In addition, as we follow the ramifications of the Reformation down the centuries, we’ll get to talk about politics, American exceptionalism, Dracula and turn-of-the-20th-century English culture (it’s amazingly relevant), and - my personal favorite - iconoclasm and incarnation.

I highly recommend reading Karl Keating’s short article “Not a reformation but a revolution.” (Quotes are coming.) He says it better than I do.

The queue starts tomorrow, Sunday October 1st!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I was a kid, I loved monsters. I dressed up as a monster or an alien (i.e., stealth monster) every Halloween. I watched monsters movies on weekends and tokusatsu shows or whatever featured monsters after school. I loved kaiju and the monsters on Sesame Street and The Muppet Show. I sat in the aisles of both my school and my city’s libraries, staring at pictures of monsters in books. I devoured books on mythology, mostly because of the monsters. (There’s nothing like Jason of Jason and the Argonauts to make you side with monsters). I would make towns out of my toys and rampage, laying waste to entire municipalities. I say all this not to establish my monstrous bona fides, but to provide some context. My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, Vol. 1 (Fantagraphics, 2017) feels eerily parallel to my own life, though I did not grow up in 1960s Chicago, like both artist/writer Emil Ferris and her protagonist, Karen Reyes. But I feel the book’s mix of horror movies and comics, mythology, private detectives and painting. Chicago was just across the lake and I spent a lot of time with my mom at the Art Institute of Chicago. On Saturdays, I would watch Creature Features like Emily Ferris and My Favorite Thing Is Monsters‘ protagonist, Karen. And I would have loved to be a monster.

In My Favorite Thing is Monsters, Emil Ferris creates the notebook of 10-year-old Karen Reyes using what appear to be the school supplies that would be available to Karen at the time. Ferris also renders Karen’s recreations of paintings at the Art Institute of Chicago and the covers of horror magazines Karen likes. (I would read any of the magazines). My Favorite Thing Is Monsters is burly book, and I am only on the first volume. Together the two volumes come to something like 800 pages.* And it is a masterpiece. When I first came on to the Gutter, I wrote about how I was interested in the parallels of fine and disreputable art. My Favorite Thing Is Monsters hits their overlap on a Venn diagram just right. Great art inspires art in response. It’s part of how you know it’s great. That and there is always more to say about it. There are a million things that could be written about My Favorite Thing Is Monsters. And when they were written and you picked up the book again and read it one more time, there would probably be a million more.

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters reminds me a lot of Lynda Barry’s work. Barry’s art is much looser and she tends not to vary her style depending on the content. Ferris style is generally tighter and more meticulous. Her range goes from very cartoony depictions to recreations of paintings that have caught Karen’s attention–in the style she has created for Karen. But Ferris reminds me of Barry in other respects. As in Barry’s Marlys comics, Ferris focuses on a school-aged girl in the 1960s. And both are willing to show the ugliness and the beauty in their characters’ lives. Though we mostly see Karen’s life outside of school. My Favorite Thing Is Monsters reminds me of Barry in its density of art and text, particularly with Barry’s memoir/creativity teaching guide/graphic novel, What It Is (2008). Ferris is not afraid to fill a page with text if it serves the story. And she is willing to mix in the pain of childhood. She remembers what it’s like to be 10-years-old.

On spiral bound, blue-lined ruled and using ballpoint pen, felt tip marker, what looks like number 2 / HB graphite and hard-leaded colored pencils, Karen Reyes records her story and the stories around her. She loves monsters and drawing and she draws herself as a werewolf girl who is not completely transformed. She lives in a basement apartment with her mom and her older brother, Deeze. Deeze protects her and teaches her about art history. They spend a lot of time at the Art Institute. Her father, “The Invisible Man,” is out of the picture. Karen goes to Catholic school, but is not particularly devout. Karen deliberately tempts monsters by going out at night to give her “the bite” that would fully transform her. At first she wants to be bitten just for herself. Later she wants the bite so she can save her family from the draft, death and “The Invisible Man.”

You tell ‘im, Sphinx!

Karen identifies with monsters not just as something as powerful when she is not, but as the shunned and despised. Karen is not like the other girls in her school or her neighborhood. She has stepped on the cootie step and is ritually polluted forevermore. But Karen was different even before that. Besides being a freak for liking monsters and reading horror comics, Karen likes her best friend Missy as more than a best friend. They watch horror movies together. They have modified their Barbie Dolls making them a werewolf and Countess Alucard. In Karen’s notebook, Countess Alucard tells Karen that she is braver than the countess because, at a sleepover, Karen dared kiss Missy’s hand when Missy was asleep.

There are a lot of problems in Karen’s life. The newest is the death of her upstairs neighbor, Anka Silverberg. Anka might have been murdered. Karen, wearing a trenchcoat and fedora, decides to investigate—looking for clues in paintings, exploring the cemetery and interviewing a specter and recordings of Anka recounting her life. Karen swipes the cassettes from Anka’s husband Joseph. But what starts out as one mystery that seems solvable proliferate into so many more.

Relatable. “I was passing a painting by Goya when it hit me.”

We all live in stories, our own and the stories we tell about ourselves together. Karen uses stories of monsters and private detectives to make sense of her self and everything happening around her. Karen believes receiving “the bite” would solve all her problems. She imagines her friend Franklin as a frankenstein. One filled wih a beautiful light revealed beneath the network of scars covering his face. Her brother Deeze has a dragon self, that is dangerous and possibly self-destructive. Her friend Sandy appears and disappears like a ghost. She sees neighbor Sam “Hotstep”** Silverberg looks much like Boris Karloff as Imhotep in The Mummy (1932). They are both tormented by the loss of their beloved. But Anka Silverberg, the woman who dies in the beginning of the book, is more protean. Sometimes Anka seems like a ghost or a zombie. But other times she is Medusa or an Egyptian queen. Like Karen, Anka used stories to make sense of her own life. Instead of horror movies and comics, Anka used mythology to understand her life in Weimar Berlin, in Nazi Germany and, later, in Chicago.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

I appreciate how compassionate the book is for one that goes into so many dark basements of life and history. It could easily become nihilistic, and Karen is briefly tempted by St. Christopher the Werewolf to give in to an impulse to destroy everything she loves because it could not protect her from the awful parts of being alive. In a dream she kills all the monsters, but realizes it is a terrible mistake. Because the monsters in her life are good. It’s the humans in the story who are “monsters.” And we call them that to try to distance any human capacity to do terrible things from human beings. We do it to feel safer and less implicated.

But if there’s anything the last two hundred years or so of history have taught me, it’s that Dracula has nothing on human beings when we go bad. I think that’s why monsters have become ever more sympathetic, despite the unhappiness of horror fans who want them to stay scary. In My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, Karen sees and hears about human beings who are capable of so much worse than Dracula or the Wolf-Man. She lives through the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King. She sees the smoke from Chicago’s West Side as it burns down after King’s assassination. And she listens to Anka’s story of growing up in a brothel in Berlin and being shipped to a concentration camp. Karen is afraid her brother will be drafted to fight in Vietnam. And she is angry that no one will talk to her about any of this.

Karen explains good monsters and bad monsters

It is easy to try to separate everything into good or bad and choose a side. But things are complicated and people are complex. And the stories that save us sometimes justify doing terrible things. There are the monsters who can’t help what they are or how they look. They are all hair and teeth or sewn together corpses and galvinism. And there are the monsters who choose to be cruel, to try to control the world and tell us the worst stories about ourselves. I make this same differentiation between monsters and “monsters” not only because I love monsters and have always hated to call awful human beings with their name. It allows people the space to be more complex than simply good or bad. The same person can do wonderful and terrible things–sometimes at the simultaneously. It is a human conceit that if somehow we can identify the monsters, we can drive them out or slay them and then live happily ever after. But these are usually the most dangerous stories, the ones that lead to genocide. Humans are not as straightforward as monsters. Dracula drinks blood to survive. Werewolves bite because they are cursed. Frankenstein*** was created and then neglected. Frankenstein can’t help what he is, what his mad scientist father made him, but after reading a lot, he can choose what he does. It is his fault that he murders, but it isn’t his fault that he doesn’t have the emotional maturity to make good choice. Like Karen, I’m with the werewolves.

*I would really like a book stand for books this burly.

**Nice play on “Hotep.”

***You can read some of my thoughts on Frankenstein and his crappy dad Victor here.

~~~

In many a distant village, there exists the Legend of Carol Borden, a legend of a strange person with the hair and fangs of an unearthly beast… her hideous howl, a dirge of death.

I’m with the Werewolves When I was a kid, I loved monsters. I dressed up as a monster or an alien (i.e., stealth monster) every Halloween.

#1960s#2010s#art#art history#Chicago#Dracula#Emil Ferris#feminism#Frankenstein#gender#Germany#horror#Illinois#Latinx#Lesbians#LGBTQ#Midwest#monsters#My Favorite Thing Is Monsters#mysteries#Queerness#the Holocaust#the ladies#undead#USA#vampires#werewolves#WWII

0 notes

Link

While most of us have never fallen prey to a cult, that doesn't mean we've escaped their allure entirely. Many of us are still captivated by the mythologies behind these dubious and sometimes dangerous sects, and the wealth of films, television shows and books on the subject is surely proof of our enduring fascination

Recent years have seen the likes of HBO's "Big Love" and "Going Clear," as well as Louis Theroux's "My Scientology Documentary" and the eerie "Martha, Marcy, May, Marlene" delve into the disturbing world of cults. Netflix's "Wild Wild Country" is the latest entry into the genre.Studio 54: The disco playground where sex and glamour reignedThe six-part documentary series tells the bizarre story of how Indian guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, also known as Osho, and his followers took up residence in rural Oregon, embarking on a campaign of bioterrorism against the enraged local community.Aside from all the poisoning, politics and preaching, Rajneesh's followers were notable in the way they presented themselves in quasi-Buddhist red and orange robes, occasionally combined with a turtleneck and beads. In contrast to the wide collars and kipper ties of the native Oregonians, the "orange people" as they were sometimes referred to looked like from a different planet.

The Rajneeshan's sartorial efforts weren't fully appreciated at the time, but they've recently found many fans on the internet. Enthusiasts of the show cheerfully share images, and a number of fashion sites run pieces on how to get the Rajneeshan look. In fact, looking at pictures of the cult, you could be forgiven for believing you'd been given a preview of the latest Alessandro Michele collection for Gucci, with all the 70's glad rags and lustrous manes of hair.Why all music festival-goers look the sameSuch a strong focus on visual identity isn't unusual in cults. Leaders are often keen to create a distinct image, combing through historical and religious iconography to draw people into their ranks.

How uniforms attract followers History has long shown that if you want to get people to behave as you want, a uniform can go a long way. "A uniform is usually a clean slate, a starting point," said Alex Esculapio, a writer and Ph.D. candidate with a focus on fashion and sociology. "It shows you're not alone and you belong to a group of people. It becomes your new identity, and really signals a new start."Whether it's cults, terrorist groups or paramilitary organizations, violent fringe factions often like to create a recognizable visual identity. Right wing demagogues Oswald Mosley and Mussolini used drab colors, like black and brown, to create an image of militaristic strength, while Marxist groups seem to favor berets and fatigues. At protests around the world you can find the instantly recognizable hoodies of the anti-fascist Black Bloc group. Religious cults might be more spiritual than political, but they clearly understand the power of uniform.

"The thing that all cults, religions, or any social groups looking to distinguish themselves from mainstream culture have in common is a uniform that really sets them apart and makes all the members look alike. It creates a group identity, which is a signal to outsiders," said Esculapio."They're similar to an organized religion, who often have specific uniforms, such as Buddhist monks or Catholic priests, and there's also an overlap with the fashion mentality in general, the idea of style tribes. I think it's a dynamic that is present in all social life, but it becomes heightened in the case of cults."Fashion's potential to influence politics and culturePerhaps the best-known example of this practice is the most violent and notorious cult of all, the so-called Manson family. In their early days at Spahn Ranch, Charles Manson cultivated a carefree, almost pastoral look for his family. The girls grew their hair long and uncombed, wore floral dresses and walked in bare feet. They could almost have been mistaken for a church group on an outing.But after a series of brutal killings and a guilty verdict, Charles Manson shaved his head and his remaining supporters followed suit, creating a peculiar pseudo-Eastern look.The flip side of the sartorial choices of cultsManson was using aesthetic to both lure people in and to push them away. He created a pastoral, utopian, hippie version of his followers for when they needed to attract lost souls and runaways, and then turned them into a violent, freakish nightmare version for when they were put on a world stage.Another infamous American cult who used uniform and stylistic language to create a feeling of purpose and vision was the suicide sect Heaven's Gate.The group shot to worldwide attention in 1997 when 39 members, including group leader Marshall Applewhite, took a lethal dose of phenobarbital and vodka, before laying down to die in adjoining bunk beds. But the most striking element of the photos splashed across the media was that every member was wearing the same pair of Nike Decade trainers and black jogging bottoms.As morbid as these images were, the pictures of the cult members' feet almost resembled a controversial fashion campaign, a feeling which was cemented when Saturday Night Live splashed Nike's famous '"Just Do It" motto across the images and created a proto-meme straight from the realm of gallows humor.Alex Esculapio, who has written about Heaven's Gate, believes that the trainers and uniforms were a way to create an identifiable and relatable aesthetic."They were different from a lot of what people might expect from a cult, because they were in touch with fashion. They were really keen on creating a visual identity and had been since the beginning. They had a few different incarnations, but they always used a specific style of clothing to emulate what they saw as aspirational. Nike shoes were particularly popular in the US in the 90's. They had specific grooming rituals, [for example] none of the men had a beard and they shaved their heads."Their neighbor at the time described them as looking like tech-nerds, so obviously they were in touch with what was happening at the time. There was a tension between isolation and hyper-awareness of modern culture, they knew they needed to stay in touch to survive," said Esculapio

However, some of the most dangerous and violent cults of all didn't need to enforce identifiable dress codes on their followers. Reverend Jim Jones may have carefully cultivated his own preacher-in-sunglasses image, but his followers looked like they could have been pulled from any mall in America.That lack of a distinct visual identity didn't stop more than 900 members from killing themselves in his name. The same goes for David Koresh's Branch Davidians, who visually resembled almost any other community in Texas, yet believed their leader to be the second coming and were willing to die for that.

0 notes