#mrs. goddard

Text

The whole Harriet Smith & Robert Martin debacle was not only Emma's doing:

a note was brought from Mrs. Goddard, requesting, in most respectful terms, to be allowed to bring Miss Smith with her

Harriet has a guardian in Mrs. Goddard, who must be aware of the association with the Martins. Harriet just stayed with them for 2 months and talks about them all the time. The Martins are welcoming Harriet into their family, with "her" cow, and height notches on the wall, and hints of Robert marrying.

So why then, does Mrs. Goddard introduce Harriet at Hartfield? Why not just keep keeping on and encourage the intimacy with the Martins? I feel like Mrs. Goddard was hoping that Emma would better Harriet's prospects. Or Mrs. Goddard is sacrificing Harriet's happiness to stay in the good graces of one of the most powerful families in the area?

Is Harriet a pawn in more than one game?

#harriet smith#re-reading Emma#Emma#emma woodhouse#mrs. goddard#Harriet is a pawn in someone's game#Robert Martin#The cow thing is so cute#And the house notches#they put Harriet on the wall of their house permanently#found family vibes

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

PARLOUR BOARDER (noun) - an archaic term for a privileged category of pupil at a boarding school.

Harriet Smith was the natural daughter of somebody. Somebody had placed her, several years back, at Mrs. Goddard’s school, and somebody had lately raised her from the condition of scholar to that of parlour boarder.

- Emma by Jane Austen, Vol. I, Ch. 03.

#langblr#language learning#english vocabulary#learning english#english studyblr#language#books and literature#vocabulary#emma#jane austen#harriet smith#i am confused as to what they mean by “a natural daughter”#are some of us unnatural or something???#mrs. goddard#boarding school#private school#school#student#studying#studyblr#study motivation

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the book ask thing — favorite book (or books, I can never pick just one), and what you’re currently reading? I’m always on the lookout for queer sci fi and fantasy recs!

For favorites, here’s one fantasy and one sci-fi:

I have to give A Marvellous Light by Freya Marske a round of applause. It’s wonderful. Joy in a box. It’s an Edwardian English missing persons/murder mystery with magic and complicated families. It also uses one of my fav magic-user tropes - the magician who does a lot with very little power. It is also rather sexy, which is often a surprise to bookclubs.

For sci-fi, I’m going to pick Record of a Spaceborn Few by Becky Chambers. It’s technically the third in a series, but the stories are only loosely connected by shared characters. They’re all worth a read, but this one is full of thoughts about memory and purpose and belonging. I’m planning a reread of this one soon.

And for what I’m currently reading:

I’ve been rereading The Hands of the Emperor by Victoria Goddard, which is massive and lovely - like a trusted friend holding your hand and saying “sometimes we can change the world with compassion and bureaucracy, and the people who love us will understand us and it will be good.”

I’m also reading From The Mixed Up Files of Mrs Basil E Frankweiler by E. L. Konigsburg for the first time right now. I found it in a used bookstore and am enjoying it. I know it’s a classic for a lot of folks, but I’d never read it before.

I hope you enjoy any of these! And I’m always happy to offer more recommendations 📚🌊

#book recs#a marvellous light#freya marske#record of a spaceborn few#becky chambers#the hands of the emperor#victoria goddard#from the mixed-up files of mrs. basil e frankweiler#e l konigsburg

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

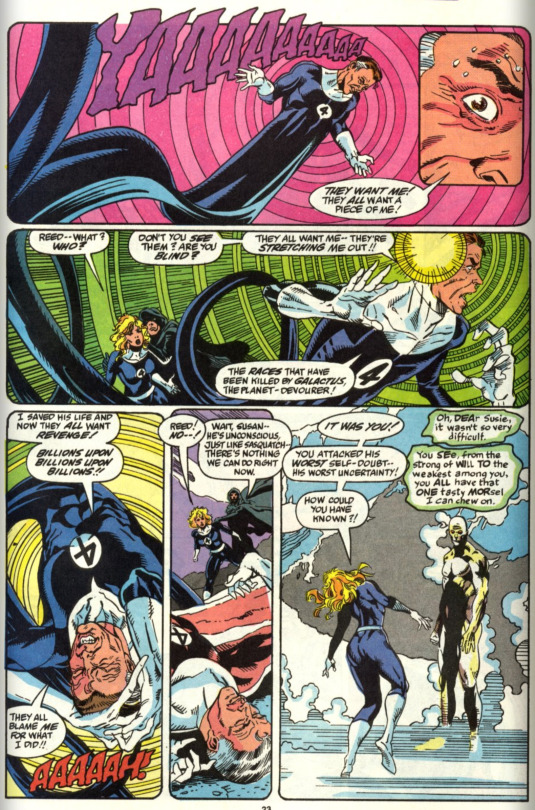

Not sure what it is, but something looks off about Sasquatch's face here...

#Marvel#Alpha Flight#Walter Langkowski ~ Sasquatch#Reed Richards ~ Mr. Fantastic#Ben Grimm ~ Thing#Sue Storm ~ Invisible Woman#Johnny Storm ~ Human Torch#Arthur Goddard ~ Headlok

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Break My Face by AJR has Cutter and Pryce energy thank you for coming to my TED Talk

#''you run your mouth/your tounge fell out/it's right there on the ground./but now you'll never drown/you can't you got no mouth''#I Am Right And You All Know It#''life gives you lemons at least it gave you something'' seems like a very Goddard sentiment I'm just saying#wolf 359#Marcus cutter#miranda pryce#Mr cutter#curio chatter

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Fic] “Winternight” - Nine Worlds

12. For violsva, in response to the prompt: any, any, and you're not even here / on the coldest night of the year, written 1/24/22

Winternight (420 words)

Fandom = Nine Worlds/Greenwing & Dart/The Return of Fitzroy Angursell

-----

The first Winternight after the Silver Forest, Jullanar was far too busy to think further than a week into the future. Scrimping her way through the bitter East Oriolan winter as an unaccompanied young woman, in a province made tight-fisted and suspicious of strangers by the protracted siege of Galderon and the slowly spiraling civil unrest that the siege had touched off, was difficult enough. Doing so as a wanted outlaw (though she managed to keep that secret mostly under her hat -- aside from one brief indulgence in the wild lay to help some local highwaymen fleece a truly asinine Voonran notable on a grand tour of the Empire, which had won her a newer, more interesting hat) was even more demanding.

By the second winter, however, she was beginning to feel the weight of expectations looming over her future like the shadow of some great carrion bird -- all the narrow straits she had sidestepped and outrun for years, now gathering pace and lapping at her heels. She was safe (and known, and respected) within Galderon's walls, but once she finished her exams... oh she didn't technically need to return home to Fiella-by-the-Sea, but what kind of daughter and sister would she be to not at least visit? And she knew herself well enough to see that once she visited, once she set so much as a finger back into the strictures of her former life, it would be next to impossible to leave again.

Not without a friend. With Ayasha or Damian, Pali or Sardeet, Masseo or Pharia, Gadarved or Faleron, to say nothing of Fitzroy, she knew how to be brave, how to turn a moment of outrage into a steady flame that could withstand an empire's scorn, but on her own she was gnawingly certain she would fold.

She lit a candle at sunset, a fat beeswax pillar (no smoky tallow, not for this), and murmured, "White Lady, you who guard us through the winter dark, help me stand strong. I was born Jullanar Thistlethwaite, but I chose -- I choose -- to be Jullanar of the Sea. Help me know myself. Help me remember."

For a breathless, scorching moment the wick flared like a falling star. Jullanar sprang back, patting her eyebrows with reflexes trained by years of Fitzroy's more experimental spells, which had a distressing tendency to explode. (Fire was always his truest element.)

"Thank you," she whispered, unsure whether she meant the words for the Lady or her absent friend.

Either way, she would keep faith.

#three sentence ficathon#liz writes stuff#nine worlds#victoria goddard#jullanar of the sea#mrs. etaris

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Economics! Economics! Read all about it! : 1974 : Mr Hodges, Strode’s College

“Each of you will subscribe to ‘The Times’ newspaper and read it every day,” Mr Hodges told us. “In class, we will discuss one of its news stories about economics.”

What?? It was my first lesson of a two-year Economics A-level course taught by a newly appointed young teacher wearing a dapper suit that could have been hiding a Che Guevara T-shirt underneath. His thick moustache signified the educational wind of change in the air. A revolution had torn through our school during the summer holidays and life for us students would never be the same. Ye olde buildings remained intact but events within had unexpectedly fast-forwarded to the late twentieth century.

A modest name-change from ‘Strode’s School’ to ‘Strode’s College’ failed to communicate the extent of the transformation. When I had arrived five years earlier, it was a grammar school whose calendar seemed to be set in 1869. The all-male teaching staff wafted around in faded black gowns as if momentarily materialised from the staff room of the University of Transylvania. Girls had ne’er been enrolled since Henry Strode founded the school in 1704. Latin lessons were compulsory. Boys wore bottle-green blazers, shorts and caps that were not permitted to be removed until we reached home. Pupils had to choose ‘arts’ or ‘science’ A-levels but not mix the two.

Headmaster James ‘Jock’ Brady would cane the bare backsides of boys in his office without the inconvenience of parental pre-approval. When carpeted for my first minor demeanour, as neither my parents nor my primary school teachers had ever laid a hand on me, I refused point blank to bend over and submit to Brady’s corporal punishment. Thereafter I was sanctioned with detentions, mediocre termly school reports and passed over for school prizes. Some of Brady’s staff seemed to be competing with him in a Strode’s league table of sadism. Writing on the blackboard, our biology teacher would suddenly spin around and hurl the wooden board eraser like a missile at the head of a student he suspected was not paying sufficient attention.

Our raised-from-the-dead English Literature tutor seemed to both teach and dwell in a dimly lit cobwebbed outbuilding that daylight had never touched, a hovel straight out of ‘Tom Brown’s School Days’. He would pace along our aisles of Victorian wooden desks, eager to whack his cane across our hands if we failed to recite our homework word-perfect. I can still reel off passages from ‘Henry V’ without the faintest notion of their meaning because the school never contemplated showing us a production. Neither were my parents of assistance since the only theatres I had been dragged to were a West End pantomime with Cliff Richard playing Buttons and appearances at Camberley Civic Hall by Lenny the Lion and Pinky & Perky.

For the first five years, my school ‘short break’ had passed standing beneath the window of the enigmatic Sixth Form Common Room hut at the edge of the Playing Field, hearing records played at extreme volume and banging on the window to be handed down a chilled bottle of Coke in exchange for some pocket money. Sixth-form prefects randomly picked on us younger students for minor infractions and handed out after-school detentions like confetti. I was once sent home by a teacher for wearing brown, instead of regulation black, socks. My slip-on Hush Puppies were deemed unlawful because shoes were required to have laces. My long journey home would result in missing an entire day of classes, and for what educational purpose? ‘Discipline over learning’ should have been the school motto … in Latin, of course.

I passed those years daydreaming of being chosen as a Prefect once I reached the Sixth Form. But the revolution denied me that power. Prefects were abolished. The Head Boy position was abolished. Girls were admitted. Uniforms were abolished. Morning and afternoon registration ended. Students were only required on-site when their timetable required attendance for a class. The Sixth Form Common Room was closed. A new teaching block was built for girls to learn Domestic Science. A host of new teachers, including women (gasp!), were employed for previously unknown subjects. Female toilets were built. Headmaster Mr Brady retired to his mansion in the nineteenth century from whence he had come. The canes were put away. One entire century of enlightened progress had been compressed into a single school summer holiday.

In our first Economics lesson, Mr Hodges gave each of us a text book but insisted the economic news stories we would read in ‘The Times’ were equally important. A discount student subscription enabled it to be delivered by a local newsagent every morning. My parents had always read ‘The Daily Express’ which I skimmed but found unedifying, exemplified by its anti-Common Market ‘Back Britain, Buy British’ masthead. However, ‘The Sunday Times’ had been my parents’ weekend preference since the 1960’s for its ground-breaking ‘Magazine’ colour supplement, permitting me to devour the newsprint sections they discarded unread and which introduced me to investigative journalism on topics such as the thalidomide scandal.

My daily journey to Strode’s by bus and train was one hour in the morning, but two hours in the afternoon that included a half-hour wait at Egham railway station and forty minutes at Camberley bus station. Though this travel elongated my school day to ten hours, it offered me the ideal opportunity to read newspapers thoroughly. Even before Mr Hodges introduced me to ‘The Times’, I had been purchasing ‘The Evening News’ at Egham station to read on my way home, it being unavailable as far out of London as Camberley. I recall once pushing open the waiting room door on Egham station’s westbound platform, only to be confronted by a couple wearing the uniforms of the adjacent Catholic girls’ and boys’ schools noisily engaged in sex on the wooden bench seat. After that graphic shock, I always waited outside on the platform.

Mr Hodges’ revolutionary teaching method stimulated my fierce appetite for the daily news cycle by reading ‘The Times’ cover-to-cover (except for the sports pages). Initially, it proved challenging to grasp the detail of British government machinations and the influence of global developments on the economy. However, significant events such as the 1973 oil crisis, ‘winter of discontent’ and ‘three-day week’ provided plenty of real-world material to discuss and analyse what ‘Economics’ was all about. I loved learning about the interaction of economic policy with politics and international news stories.

In the Lower Sixth form, some of my closest school friends decided to apply to study at Cambridge University, which encouraged me to do likewise. Tim, Martin and Philip planned to first complete their A-levels and then focus during a ‘year out’ solely on their applications. This avenue was not available to me as my family’s dire financial situation meant my single-parent mother could not afford to support my studies for a further year. Despite his substantial arrears, my absent father had already persuaded Farnham court on my sixteenth birthday to reduce his maintenance obligation for me to £1 per year. I had tried desperately to find a summer job in 1974 to assist my family but to no avail.

As a result, I was required to sit Cambridge’s entrance examination papers at the same time as studying for my A-levels, with extracurricular one-to-one tutorials generously fitted around my timetable by Mr Hodges and a maths teacher. Somehow, I managed to pass by a slim margin and was called for interview. I travelled to Cambridge alone, wearing the one stiff grey suit that my mother had bought for me to attend my cousin Lynn’s church wedding. On the train, I read the day’s papers thoroughly to ensure I could confidently discuss the British government’s economic policies and the latest international affairs. After all, I had applied to study economics.

“What sort of school is Strode’s?” my elderly interviewer asked.

“It’s a sixth form college,” I replied, “that used to be a grammar school.”

“Of which school sports teams have you been captain?” he asked.

“None,” I replied.

“What positions of responsibility, such as Head Boy, have you held at school?” he asked.

“None,” I replied. “Our college does not have a Head Boy or Prefects.”

“What does your father do?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” I replied truthfully.

“What do you mean you don’t know?” he immediately shot back at me.

“My parents are divorced and I haven’t seen my father for several years, which is why I don’t know what he is doing presently.”

“But he must have a profession, like a doctor or a banker or a barrister. What is his profession? Who employs him?”

“He qualified as a quantity surveyor and used to be self-employed.”

He seemed unsatisfied by my response. My father had left school at age fourteen. What could I do? I was not my father’s keeper! My interviewer waved towards a corner of the dingy interview room.

“There’s a piano over there,” he said. “Can you play something for me?”

“Sorry but I can’t,” I admitted. In my head, I was reflecting that I could name every minister in the present British government cabinet, if asked, and every aspect of its economic policy. However, my interviewer seemed convinced I was destined to be another Jane Fairfax.

“Did you not learn piano at school?” he asked.

“No. My school is focused on academic subjects, which is how I passed nine O-levels,” I replied.

The ‘interview’ continued in this same baffling style for half-an-hour. Not a single question was asked of me about economics, current affairs, news or, indeed, anything relating to the real world in which I lived. Enquiries were wholly about my success at making myself noticed by my peers and being appointed to team responsibilities by schoolteachers. There was no opportunity for me to mention having been male head of my family for the last few years, visiting solicitors, phoning courts, responding to Final Demands, writing endless letters to the tax office, utility companies and benefit agencies. Even if I had desired, I had insufficient free time to glorify my ego because I had all these responsibilities at the same time as passing three hours a day commuting to and from school.

On the long train journey home, I was not upset because I had no understanding of what had just happened. From an early age, I had had to invest and believe in the concept of ‘meritocracy’. Otherwise, I would never have bothered struggling to succeed in life. It was only years later I fully understood that my application, having lacked the benefit of wholehearted support from my school, had been made to a Cambridge college that accepted only around a hundred new undergraduates a year. Probably between zero and five of those accepted that year would arrive from state schools such as mine, regardless of how many had applied. My answers to the interviewer had merely reinforced a prevalent belief that boys like me were unsuited to aspire to study alongside the favoured elite from private schools. It had never been about academic ability alone. It required proof that you longed to be accepted by ‘them’ as ‘one of us’.

Unsurprisingly, the college I had applied to rejected me. My name was then placed in a ‘pool’ of applicants, probably filled with young people like me who had failed to prove at interview that they were ‘gentleman’ or ‘deb’ material. Eventually, I was informed that every other Cambridge college had similarly rejected me. The dream was over. It’s just one of those things you put down to experience.

What did not end was my insatiable appetite for reading newspapers, stimulated by the amazing Mr Hodges, that led me to ravenously consume a broadsheet daily for decades to come. For that I remain eternally grateful to a teacher who broke away from our school’s usual text book rote learning and opened the door to me understanding the big world beyond.

0 notes

Text

In Emma, the incident that sparks the story isn't a death or a loss of fortune or even someone new coming to town. It's a wedding. A happy event, usually the end of a story. But I like how this acknowledges that even a happy event like a wedding can bring its own kind of sorrow. Emma's happy for Miss Taylor, but she still mourns the way that her life has to change. Marriage can massively alter social circles, especially for women, taking them away from the home sphere and into a new life, and forcing the people they leave behind to deal with the loss. Here, it's a good change, but it's still a change.

Emma's in a unique position among Austen heroines. She's got money, a comfortable home, a loving father who would prefer she stay in his household for the rest of her life. She doesn't have to consider matrimony as a business arrangement the way some heroines have to. If she marries, it's going to be almost solely for companionship.

Because that's the one thing Emma lacks. She's lonely. She loves her father, but he's not someone she can engage with socially or intellectually. She ranks above everyone in town, so there's no one who can be on an equal level with her. Her father won't travel, so she can't get involved in social events with people who are of her rank and happen to live a little further out. Her attachment to Harriet is a desperate attempt to create a companion of her own social rank, and then marry her to Elton so she can remain in Emma's social circle. Mrs. Martin would be just another farmer's wife who sits below Emma's level; Mrs. Elton can be her equal.

But we can't overlook the fact that Emma makes the situation worse through snobbery. She's not only of a higher social rank than the people around her--she feels herself superior to them. Her father has plenty of friends, but to her, Mrs. Goddard and Miss Bates are just "prosy old ladies". Which is fine--they're more of her father's age, not hers. But it does indicate a wider personality problem. There's more than a hint of Mr. Darcy about the way she goes about detaching Harriet from Mr. Martin because he's so "coarse and vulgar", and trying to raise her up to Emma's standards of what's acceptable.

So, anyway, Emma's uniquely positioned in a story where friends-to-lovers has to be the character arc. And in the process, she's got to overcome her sense of superiority that makes it so difficult for her to classify people as friends.

#the great emma reread begins!#emma#jane austen#i feel like this should have been a bullet-point list#because written out in essay form i'm just restating what everyone's said a jillion times#but i gotta get my thoughts straight to have a lens on this reread

832 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't know if I missed Period Drama Appreciation Week, but here is my entry. I love Emma 2020, especially what they did with costuming and mannerism in Harriet Smith.

Here we have the first meeting, Harriet looks very frumpy in her outfit and she often looks over at Emma for guidance on how to act:

Here is the much later meeting with Mrs. Elton, where Harriet is assimilating to how Emma looks and acts (one of the biggest changes, Harriet does not eat this time):

At Box Hill, full imitation:

The transformation is slow but sure, Harriet looks less and less like her peers at Mrs. Goddard's school and more and more like Emma. She never becomes quite as elegant (just watch the feet, Emma stands in a ballet pose which Harriet never matches), but she does become quite the little double.

The detail and attention to costuming, the soundtrack, and the Knightley are all things I love about this movie.

#period drama appreciation week#period dramas#emma 2020#costumes#emma woodhouse#harriet smith#jane austen#making yourself a little clone

474 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHILBLAINS (noun) - also known as pernio, a medical condition that causes inflamed swollen patches and blistering on the hands and feet, caused by exposure to cold.

Mrs. Goddard's school was in high repute, and very deservedly; for Highbury was reckoned a particularly healthy spot: she had an ample house and garden, gave the children plenty of wholesome food, let them run about a great deal in the summer, and in winter dressed their chilblains with her own hands.

- Emma by Jane Austen, Vol. I, Ch. 03.

#langblr#language learning#english vocabulary#learning english#english studyblr#language#books and literature#vocabulary#emma#jane austen#mrs. goddard#mistress of school

0 notes

Text

Propaganda

Aleksandra Khokhlova (By the Law, The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks, The Death Ray)—aleksandra khokhlova was a russian actress, theater director, and writer, best known for her collaborations with the pioneering film director lev kuleshov. im so gay for her teeth.

Paulette Goddard (Modern Times, The Women, The Great Dictator)—she got started in the 1920s in Chaplin movies, but I actually like her best in her sound career—she's so funny and always conveys a liiiiittle bit of bitchiness in everything I've seen her in! my fave is this very genderbendy bit in "Pot O' Gold," [editor's note: some Hollywood "Latin" stereotypes in the clip] where she goes into full drag king mode to sing a song about what a lady killer she is. it blew my mind that this turned up in a 1930s movie with absolutely no context. it's so queer and I love her for it.

This is round 1 of the tournament. All other polls in this bracket can be found here. Please reblog with further support of your beloved hot sexy vintage woman.

[additional propaganda submitted under the cut.]

Aleksandra Khokhlova:

Paulette Goddard:

Perhaps best remembered as the gamine from Chaplin's movies - and she is so charming, mischievous, energetic and heartbreaking in the role

It’s impossible to watch her with Charlie Chaplin and not fall in love with her, the absolute most perfect sweetest feistiest actress

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prelim Poll 6

Propaganda here

*Yes they're all names (and appearances) of the same character. In the picture above, the character presents as Amber, she/her

#tournament polls#colornames battle#prelim 6#prelims#megaman x#mega man x#megaman#watership down#movieblr#gameblr#lord golden#rote#realm of the elderlings#dna says love you#bookblr#sam black#misfits and magic#d20 misfits and magic#d20#subaru sengoku#tiger and bunny#tiger & bunny#word of honor#gu xiang#it lives in the woods#ilitw#kaguya sama: love is war#kaguya sama wa kokurasetai#kaguya sama wo kataritai#animeblr

53 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I like the sentiment here, where they are trying to make Reed look repentant for signing the death warrant for billions of people by saving Galactus... but he himself has admitted that he felt zero belief that he had done anything wrong...

#Marvel#Alpha Flight#Reed Richards ~ Mr. Fantastic#Sue Storm ~ Invisible Woman#Arthur Goddard ~ Headlok

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

hello I am going crazy over these two exchanges

Jacobi: See, that's the part of this you all don't want to ever talk about. Goddard's done some good stuff, and it's done some deeply messed up stuff, but that's not the point.

Lovelace: What is the point?

Jacobi: Progress. And progress doesn't care about good, doesn't care about bad, it's just… forward.

- episode 52, Constructive Criticism

Rachel: You knew what you were getting yourself into.

Jacobi: No, I didn't. I didn't know I was getting into mind control. I didn't know I was getting into reducing people to nothing! There is a line. And you're almost out of chances to get on the right side of it. Please. Stay. Fight this.

Rachel: You done? Okay. There is no line, Mr. Jacobi. Forwards. Always forwards. Goodbye.

- episode 61, Brave New World

a microcosm of Jacobi's character development if I ever saw one

#help it's thinking about daniel jacobi hours today#just about to hit dirty work on my 4th listen and aaaaah#he's such a fucked up guy i love him#daniel jacobi#wolf 359

121 notes

·

View notes