#magadha

Text

Siddhartha Gautama, the latest Buddha. नमो बुद्धाय (1/2)

Born in Lumbuni Nepal, travelling through Magadha - Indo-Gangetic Plain. His teachings were mainly based on local Sramana philosophical concepts. Somewhat influenced by Vedic Brahmanism, Ajivika and Jainism, Buddhism started as an alternative for the new Indo-Europeans from the west and the Dravidian populations in the South of the sub-continent.

In the first two hundred years the teachings were spread by Oral traditions such hymns and stories. Later on around it was written down as more influences on the teachings were being made. The different divisions of the Buddha Dharma meant isolated influences on the Dharma but also reactions to each other resulting in complete different schools. The most distinctive difference is between de so called Theravada Buddha Dharma and the Gandhara Buddha Dharma. Heavily influenced for at least 400 years by Hellenism, the Gandhara Buddha Dharma spread towards the West via the Silk Road and the East, towards China and Korea.

What form or how to express 'Buddhism' is not a real problem as long the Sramana Dharma and the essence, goals and behaviour codes are not being changed.

Namo Buddhaya 🙏🏾📿

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

They spoke from the margins – socially, because most stood on the lower rungs of the elite; and geographically, because most cake from small states on the fringes of power.*

*Not all, though. The Mahavira (roughly 497-425 BCE), founding father of Jainism, came from Magadha, India's most powerful state. Zoroaster, whom some historians include among the Axial Age masters, was Iranian, although he lived – probably some time between 1400 and 1600 BCE – while Persia was still marginal to the Western core. (I do not discuss Zoroaster here because the evidence is so messy.)

"Why the West Rules – For Now: The patterns of history and what they reveal about the future" - Ian Morris

#book quote#why the west rules – for now#ian morris#nonfiction#marginalized#mahavira#jainism#magadha#india#zoroaster#axial age#iran#persia

0 notes

Text

Magadha Empire | The kingdom of Magadha

Magadha Empire | The kingdom of Magadha

Magadha Empire | The kingdom of Magadha

Magadha Was The Most Powerful Mahajanapada Among The Sixteen Mahajanapadas Of BC.

Means To Know The History Of Maurya Dynasty

(A) Indica By The Greek Ambassador Megasthenes

(B) Economics Of Kautilya

(C) Ashoka’s Inscriptions

(D) Buddhist Texts Deepvansh And Mahavansh

(E) Mudrarakshas Natak Of…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

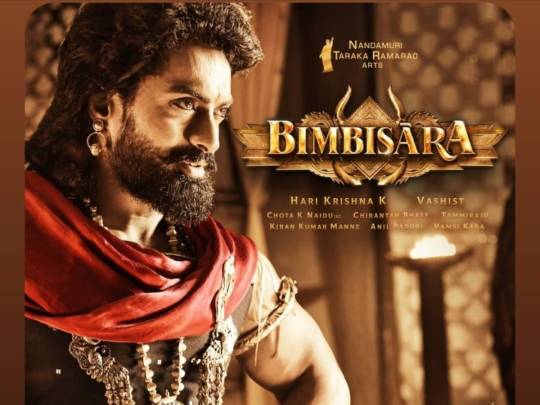

Bimbisara Official Trailer

Bimbisara is an upcoming Indian Telugu-language fantasy action film written and directed by Mallidi Vashist, and produced by N. T. R. Arts. It stars Nandamuri Kalyan Ram, Catherine Tresa, Samyuktha Menon, and Warina Hussain. Kalyan Ram plays King Bimbisara who ruled the Magadha Empire in the 5th century BCE.

Starring #NandamuriKalyanRam, #CatherineTresa, Samyuktha Menon, Warina Hussain, Vennela…

View On WordPress

#Bimbisara Official Trailer#Catherine Tresa#Director Mallidi Vashist#King Bimbisara#Nandamuri Kalyan Ram#Samyuktha Menon#the Magadha Empire#Warina Hussain

0 notes

Text

Sawan 2022:बाबा सिद्धनाथ मंदिर में मगध सम्राट जरासंध चढ़ाते थे जल, सावन में लगती है भीड़

Sawan 2022:बाबा सिद्धनाथ मंदिर में मगध सम्राट जरासंध चढ़ाते थे जल, सावन में लगती है भीड़

आगामी 14 जुलाई से श्रावणी मेला शुरू होने वाला है। सावन महीने में राजगीर की वैभारगिरि पर स्थित जरासंध कालीन बाबा सिद्धनाथ मंदिर में हजारों भक्तों की भीड़ उमड़ती है। सावन में यहां पर जलाभिषेक व दर्शन के ल

Source link

View On WordPress

#Astrology Today#Astrology Today In Hindi#Baba Siddhanath Temple#Hindi News#Hindustan#Magadha Emperor Jarasandh#News in Hindi#sawan#sawan 2022#Sawan Shiva#बाबा सिद्धनाथ मंदिर#मगध सम्राट जरासंध#सावन#सावन 2022#सावन शिव#हिन्दुस्तान

0 notes

Text

[Image above: Gobajo statue with a crown of elephant, the largest animal on land, on its head. One of the Eight Legions.]

Legends of the humanoids

Reptilian humanoids (10)

The Eight Great Dragon Kings – Dragon tribes who listened to the Buddha's teachings.

They are the eight kings of the dragon races, who belong to the Eight Legions of Buddhist dieties. They protect the Buddha Dharma.

In Buddhism, Nagaraja (lit. 'king of the nagas') in Hindu mythology was incorporated as various dragon deities, including the Eight Great Dragon Kings.

Nagarajas are supernatural beings who are kings of the various races of Nagas, the divine or semi-divine, half-human, half-serpent beings that reside in the netherworld (Patala), and can occasionally take human form. The duties of the Nāga Kings included leading the nagas in protecting the Buddha, other enlightened beings, as well as protecting the Buddha Dharma.

Some of the most notable Nagarajas occurring in Buddhist scriptures are Virupaksa, Mucalinda, Dhrtarastra, and the following Eight Great Dragon Kings:

Nanda (Ananta, lit. joy): Ananta and Upananda were brother dragon kings who once fought against the Dragon King Sagara.

Upananda (lit. sublime joy): Brother of Nanda. Together with King Nanda, he protected the country of Magadha, ensuring that there was no famine, and when the Buddha descended, he sent rain to bless it and attended all the sittings where he preached. After the Buddha's death, he protected the Buddha Dharma forever.

Sagara (lit. 'Great Sea'): king of the Dragon Palace. King of the Great Sea Dragon.The 8-year-old Dragon Lady in the Lotus Sutra was the third princess of this Dragon King and was known as the Zennyo Ryuo (lit. "goodness woman dragon-king").

Vasuki (lit.'treasure'): sometimes referred to as the Nine-Headed Dragon King with the 'nine' meaning the extremity of yang and extremely large and powerful in number. Thus, he was thought of as the "Nine-Headed Dragon King". In the original legend, he was seldom called the 'Many-headed Dragon King' because there were a thousand of heads. Originally, he protected Mt. Meru (Ref1) and took tiny dragons to eat.

Takshaka (lit. ‘polyglot' or 'visual poison'): When this dragon is angrily stared at, the person is said to die out. From the Golden Light Sutra, the Seven-faced Tennyo is said to be the daughter of this Dragon King.

Anavatapta (lit. "cool and free from heat"): was said to live in the mythical pond in the northern Himalayas, Anuttara (lit. "free from heat"), which emitted great rivers in all directions to moisten the human continent of Jambudvīpa. A pond that stretches for approx. 3142 km, the banks of the pond were said to be made of four treasures, including gold, silver and others. This Dragon King was venerated as an incarnation of a Bodhisattva.

Manasvin (lit. 'giant' or 'great power'): When Asura (See2 & See3) attacked Kimi Castle with seawater, he twisted himself around and pushed the water back. Kimi Castle is the castle in Trayastrimsa at the top of Mt. Meru, where Sakra (Indra:Ref) resides.

Uppalaka (Utpala: lit. blue lotus flower): blue lotus flower dragon king. He is said to dwell in a pond that produces blue lotus flowers. In India, the shape of the petals and leaves is used metaphorically to represent the eye, especially the blue water lily (nilotpala), which is a metaphor for a beautiful eye. In Buddhism, the Buddha's eyes are considered to be dark blue (nila), one of the 32 phases (ref4) and 80 kinds of favourites (ref5), "eye colour ".

伝説のヒューマノイドたち

ヒト型爬虫類 (10)

八大龍王〜釈迦の教えに耳を傾けた龍族

彼らは、天龍八部衆に所属する龍族の八柱の王である。仏法を守護している。

仏教では、インド神話におけるナーガラジャ (ナーガの諸王の意) が、八大龍王をはじめさまざまな龍神として取り入れられた。ナーガラージャとは、冥界 (パタラ) に住む神または半神半人の蛇のような存在であるナーガ (参照) の様々な種族の王であり、時には人間の姿をとることもある超自然的な存在のこと。

ナーガ王たちの任務は、ナーガたちを��いて仏陀や他の悟りを開いた存在たちを守護し、仏陀の教えを守ることであった。

仏教経典に登場するナーガラージャの中で最も有名なものには、ヴィルパクサ、ムカリンダ、ドルタラストラ、そして以下の八大龍王たちである:

難陀 (アナンタ:歓喜の意): 難陀と跋難陀は兄弟竜王で娑伽羅 (サーガラ:大海の意) 龍王と戦ったことがあった。

跋難陀 (ウパナンダ: 亜歓喜の意): 難陀の弟。難陀竜王と共にマガダ国を保護して飢饉なからしめ、また釈迦の降生の時、雨を降らしてこれを灌ぎ、説法の会座に必ず参じ、釈迦仏入滅の後は永く仏法を守護した。

娑伽羅 (サーガラ:大海の意): 龍宮の王。大海龍王。法華経に登場する八歳の龍女はこの龍王の第三王女で「善女龍王」と呼ばれた。

和修吉 (ヴァースキ: 宝��の意):「九頭龍王」と呼ばれることもある。「九」は陽の極まりを意味し、数が非常に多く強力であることから、「九頭龍王」と考えられた。そのため、彼は「九頭の龍王」と考えられていた。元の伝説では、頭が千個あったため、稀に「多頭龍王」と呼ばれることもあった。もともとは、須弥山(参照1)を守り、細龍を捕らえて食べていた。

徳叉迦 (タクシャカ: 多舌、視毒の意): この龍が怒って凝視された時、その人は息絶えるといわれる。身延鏡と金光明経から七面天女は、この龍王の娘とされている。

阿那婆達多 (アナヴァタプタ: 清涼、無熱悩の意): ヒマラヤ山脈北部にある神話上の池、阿耨達池 (無熱悩池) に住み、四方に大河を出して人間の住む大陸 閻浮提 (えんぶだい) を潤していた。 全長800里 (約3142 km)にも及ぶ池の岸辺は金・銀などの四宝よりなっていたという。この龍王は菩薩の化身として崇められていた。

摩那斯 (マナスヴィン: 大身、大力の意): 阿修羅(参照2 & 参照3)が海水をもって喜見城を侵したとき、身をよじらせて海水を押し戻したという。喜見城とは須弥山の頂上の 忉利天にある 帝釈天 (梵: インドラ参照) の居城。

優鉢羅 (ウッパラカ: 青蓮華の意): 青蓮華龍王。青蓮華を生ずる池に住まうという。インドでは花弁や葉などの形状を比喩的に眼を現すことに用いるが、特に青睡蓮(nilotpala)は美しい眼に喩えられる。仏教では仏陀の眼は紺青色(nila)とされ、三十二相八十種好(参照4)の一つ「眼色如紺青相」となっている。

#eight dragon kings#dragon#humanoids#legendary creatures#hybrids#hybrid beasts#cryptids#therianthropy#legend#mythology#folklore#nature#art#reptilian#snake

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Have just a little desire and knowing what's enough.”

- that is, you have to have a little less "desire". It's about having a heart that is grateful that it's enough, a heart that knows it's about enough.

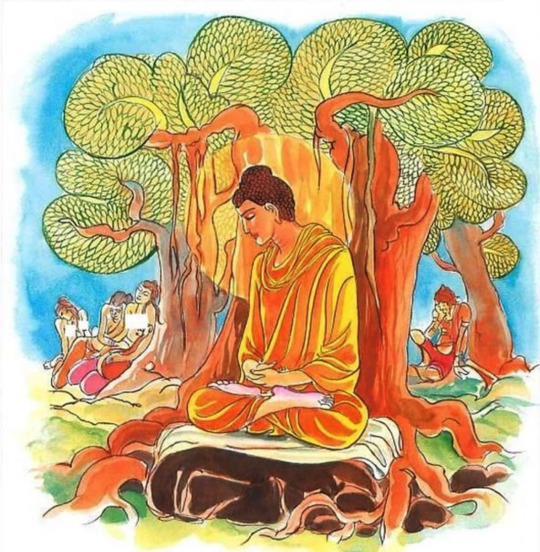

The Buddha was ordained at the age of 29. To be ordained means to leave home and become homeless, in other words, a recluse.

The first place the Buddha went to after his ordination was Rajagriha in Magadha (now Rajgir, Bihar), the capital and bustling metropolis of what was then India's greatest power. One day, the king of Magadha saw the Buddha walking gracefully through the streets, in distance. The king was so moved by his nobility that he immediately met with the Buddha and offered him half of Magadha on the extraordinary condition that he would renounce his ordination, and serve as an officer in Magadha. The Buddha refused unreservedly.

"I did not to be ordained to fulfil my desires. I have left to know that desire is dangerous." These were the words of the Buddha.

So, what is 'desire'?

The desire to eat well, to wear "beautiful clothes", to live in a comfortable place, to get ahead, to be honoured, to have power... There are many desires. These desires are, in essence, the desire to be happy.

The trouble with these desires is that there is no limit to them. We want to be happy, and we try to get money to do it. But as soon as they get a bit of money, they want more and more.

In Buddhism, the word for "desire" is "trisna". This Sanskrit word means "thirst". Suppose your ship is wrecked and you are in a lifeboat waiting to be rescued. But you have no drinking water. If you drink seawater, will it quench your thirst? No, it won't. The more you drink, the more thirsty you will become.

The more you satisfy a desire, the more it grows. The first thing to do is to recognise that this is what desire is all about.

Then it becomes clear that we have to give up our "desires".

The counter-argument is that 'some desires are good.' For example, "Isn't it good to have a desire to develop one's talents and hope for the future? It is not right to deny this in general".

But think about it. If you have such desires in the name of hope, the person you are at present becomes a useless being. The spiritual desire to progress and improve, if not the desire to earn more money, is also a 'desire, the thirst'.

In other words, there are no good desires. That is the teaching of Buddha. So we have to give up our desires. But to give up "desire" does not mean to become "desire-less". No human being can ever be completely "ascetic".

Therefore, it’s not trying to say "don't work hard" or "don't try to increase your income". If you are grateful for your current income and relaxed about it, your income may increase one day. You just have to wait for it. On the contrary, to deny the present and say, " This is not good enough!" If you deny the present and chase after greed, you are on the way to destruction. The Buddha taught us not to live in such a foolish way.

The important thing is to give up just a little bit of “desire " (to have little desire) and have a sense of gratitude (to know what is good for you). Just be grateful for the present and enjoy it.

119 notes

·

View notes

Note

What’s the name of the Indian Tamamo that Tamamo cat mentions and is she connected to any of the current Indian servants?

That'd be Madame Kayo, wife of Kalmasapada the Freckle-Feeted King. And no, she's not connected to anyone other than her fellow Tamamos. Kalmasapada's story is pretty self-contained.

"Kayo? That name sounds a lot more Japanese than Indian."

Excellent point, imaginary commenter. Madame Kayo's myth is Japanese-original.

Tamamo and Daji had already established the trend of when a king is absurdly bad, his political failings get blamed on the evil influence of his super hot wife who is a fox in disguise, so when the tale of super awful king Kalmasapada of Magadha was transmitted to Japan, the Japanese edition decided to add the fox wife trope to his myth, thus creating the character of Kayo.

Kalmasapada's story is that after inheriting the throne of Magadha, he became a faithful follower of an evil religion and swore to unify India by offering the heads of 1000 kings to his unidentified evil god. 999 kings later, he captures Samantavidyaraja (king not mentioned in any other story as far as I know) to be the 1000th sacrifice, but Samantavidyaraja explains the Buddhist truth to him and he becomes a monk.

The Japanese retelling of his story introduces the nine-tailed fox both in her usual role as his corrupting sexy wife and also makes her fox form the nameless evil god that he worshipped.

Side note: In all versions of the myth, Kalmasapada is born because his father finds a lioness in the mountains and has sex with her, so some versions like to exploit his lion lineage to make him more evil by adding that his favorite food is human flesh, which he always procures through cruel and unethical means.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Janmashtami reminded me how Vaasudev never returned to vrindavan and it really tugged on my heart strings. I spent hours questioning and grieving, trust me I felt the grief. I couldnt understand how a kid could leave his life behind like that, how did he live, how did he never look back.

How could i not feel the melancholy of his parents?

They loved him so dearly, more than their own life. Every inch of braj did.

I had no answer. I couldn't understand him. I wondered what happened to the love.

After hours of torturing myself with such thoughts, i let go. I couldn't afford to let this make me more anxious. Of course I felt a little better when i stopped putting my energy to it but a small corner of my heart held on.

I didn't realise it till I felt the first shiver of season change this morning.

I'm here with what I realised.

He had a purpose, a responsibility towards his birth parents and the bhoomi of magadha- given his relation. Once he fulfilled that, he was sent for formal education. He spent years imbibing and growing.

When he came out of the gurukul, he was no longer the kid who left vrindavan. He was changed person with new priorities, new purpose, new responsibilities and new struggles.

His life evolved and took him along the tide of existence.

In his life, his shoulders were so ladden with responsibilities, his hands were so full of duties. Despite being a free soul, life slowly circled around him with its chains and he let it because he knew, he knew that was for the best.

He understood that life wasn't meant to be standstill and rooted, esp not his.

Much like the cosmos, existence is tidal and dynamic. It sheilds itself away like ocean floor, you have to simply surrender to the flow and guide it the way you want it. That's the best you can do. That's what he did.

So in a way we're all like Krishna, we all leave our families behind. We all move forward with the spirit of our parents in our heart.

We all yearn to leave our house and go look for a life that suits us best. As we grow older, we change, evolve and become someone else.

But does that mean we no longer harbour love for our families? No. We always carry them with us in our deepest rooted sensibilities and actions.

I guess you can call me dumb that I took so long to understand this but hey, i finally got it and I'm happy. Very happy in fact.

This was a fruitful morning. Anyways thank you for attending another one of my rants and realisations. you don't have to but you do (i kinda force you by tagging y'all but you can always ignore lmao) sorry

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

Professor Irfan Habib traces the aspects of development of the caste system with respect to the agrarian history of India.

below are some passages i found interesting

Wheat and barley cultivation began in India after 7000 BC, with the earth pierced only with the manually wielded hoe, yielding, therefore, a very low rate of output. Rice seems to have come to north India from China around 2000 BC or a little earlier. (One must here be on guard against the tendency of some Indian archaeologists to assign impossibly early dates to their supposed finds. That is a habit that has unfortunately grown during the last 50 years.)

———

Now, it was during this period (around 7000 BC and later) that what Gordon Childe called the Neolithic Revolution took place in the Near East. Essentially this meant that after cattle domestication, cultivation with the plough would be the next step. But there was no iron, and therefore, where there were dense forests, neither agriculture nor urban culture could take root. Thus, the Indus Civilisation, whose dates are about 2500–1800 BC, could not advance beyond the line of 30 inches or at the most 40 inches of annual rainfall. We would like to know more about the Indus Civilisation and whether there was any form of caste system in that society, but as the inscriptions on its seals have not been deciphered, it is better not to speculate on it, and instead come to the time of the Rigveda or the early Indo-Aryan settlements, datable to about 1500 BC and thereafter. In the time of the Rigveda the “Āryas” practically occupied the same area as the Indus Valley Civilisation, perhaps with some settlements piercing the Jamuna–Ganga doab, but still not going beyond the 40-inch line of annual rainfall. That means that the major forests were still uncleared.

———

Things changed only with the coming of iron. The archaeological evidence shows that iron came to India, to south India as well as to north, around 1000 BC or a little later. It took time, of course, for ironsmiths to learn their trade and to lighten the plough by replacing the stone slab with the iron point. Ultimately, by Mauryan times, we have the standard peasant using a plough with an iron coulter, a light wooden structure drawn by two bullocks. And it was this particular technological development in the Iron Age, I think, that at last created the Indian peasant (ploughman and bullock-owner in one).

This raises the question of the association of the Shudra caste with the peasants. Since earlier the cattle-owners, being also plough-owners, were Vaishyas, the caste system was faced with this new situation, where the plough-owner was himself a worker with a pair of bullocks to feed. In the Manusmriti there is, therefore, a deprecation of the peasant’s position. It is now the Buddhist ahiṁsa doctrine that is appropriated by the author of the Manusmriti, namely, that since the iron plough injures earth’s creatures, ploughing is a condemnable occupation, and peasants therefore cannot belong to the “twice-born” castes (the first three castes) and so must remain Shudras. But still, since earlier texts had treated peasants, or at least plough-owners, as Vaishyas, that classification is not directly contested in the Manusmriti. As Professor R. S. Sharma has shown, the tendency is now increasingly – even among the Buddhists, as one can see from Yijing’s account around AD 700 – to denounce the peasants’ occupation as violative of ahiṁsa, which justified their being counted among the Shudras.

———

There is a second aspect also of the change in agrarian conditions, and that is the creation of the “outcastes.” With the introduction of iron and its increasing use – particularly after the arrival of the shafted iron axe – forests began to be cut down, so that for the first time there were large clearances made in the Gangetic basin, especially in Magadha and Kaushala. The process began long before the Buddha, but continuing in his time, involved a long process of subjugation and humiliation of the forest communities. The forests were not previously without human beings. They were full of what Gordon Childe called “gathering communities” – animal hunters, food gatherers, woodcutters, and those who trapped small animals, all of these constituting a large number of communities. These communities were now seen as enemies of the settled populations. As forests were cleared, they were either killed off or subjugated. Those who survived came to form the outcaste communities. If one looks at the list of such communities in the Manusmriti, one finds leather workers, workers in cane, fishermen, carpenters and wood workers, hunting communities, and others. About four or five communities whose names are given in the Manusmriti lived by hunting and killing animals. And then we have the general categories of Chanḍālas, Shvapāchas, etc., comprising all who were involved in what Gordon Childe called “gathering��� occupations in society.

———

The Manusmriti thus shows how, as forests were cleared, these forest communities became major components of the class of Chanḍālas (outcastes). Their members became seasonal field labourers and were assigned what were regarded as the most humiliating professions, like leather work, dirt removal, and as porters – the professions furnishing their means of survival in off-seasons. This was because in the Indian conditions, where there were two sowings and two harvests in a year, agriculture needed extra labour only at these times; there had now to be a reserve of labour for that extra work, which was provided by outcastes.

———

Buddhism has a particular role to play in this process, a role that is often overlooked. Despite the humanitarian vision one attributes to Buddhism and Jainism, and despite their condemnation of the Brahmans, we seldom find any direct condemnation of the caste system in their early texts. In fact, the Buddha is said to have taken pride in the strict endogamy practised by Kshatriyas. But there are two major new elements to consider at the ideological level. First of all, there was the doctrine of transmigration of souls initially put forward, not by Brahmanical sects, but by Buddhism and Jainism. We may recall that even in the Upanishads (the Chhandogya Upanishad, for example), the source of the doctrine of transmigration of souls is traced specifically to the Kshatriyas; and both Mahavira and Gautama Buddha, who espoused this doctrine, were Kshatriyas. When the doctrine was popularised, it immediately provided an important justification for the caste system, because one’s position by birth in the caste hierarchy could now be justified by one’s presumed deeds in a previous birth.

Secondly, the ahiṁsa doctrine, as I have already mentioned, could be used to denigrate the occupation not only of foresters but also of peasants, and thereby reduce them to the status of Shudras. One greatly admires Ashoka, and it must be said to his credit that in his Dhaṁma, the varna or caste doctrine finds no place, partly perhaps because at that time the caste system as it developed later was only established in parts of Bihar and Awadh in the Gangetic basin and not in other parts of his empire. As far as one knows, the Indus basin and the Deccan possibly did not have the varna system at that time. Certainly, the historical records of Alexander’s invasion do not make any reference to its presence in the Indus basin, although Brahmans are mentioned. It is only Megasthenes, who visited Magadha, who offers us a description of a fairly developed caste system. But still Ashoka, otherwise so peaceable, warns the forest-folk that if they persisted in their occupations, they would be killed; they are marked as the enemy in his so-called Kalinga Edicts.

———

In condemning the forest-folk for killing animals, there was surely also a major economic impulse, viz., to turn them into Chanḍālas and similar outcaste communities: reduced to extreme privation, they could provide cheap agricultural labour. And it is perhaps true to say that until the last century, it was the outcastes who provided the bulk of the agricultural labour needed by the Indian peasantry. No such institution existed anywhere else in the world. When we examine the literature that Professor R. S. Sharma has explored in his Shudras in Ancient India, and other ancient Indian sources studied by his colleagues, as well as the medieval evidence that is so profuse, we always find that agricultural labourers belong mainly to the outcastes, the “untouchables.” This constitutes a fundamental feature of India’s agrarian order.

here's a different lecture by the professor on the topic

youtube

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Royaume de Magadha

Le Magadha était un ancien royaume situé dans les plaines indo-gangétiques de l'est de l'Inde et s'étendait sur ce qui est aujourd'hui l'État moderne du Bihar. À l'apogée de sa puissance, il revendiquait la suzeraineté sur toute la partie orientale du pays (à peu près la superficie de l'Angleterre) et gouvernait depuis sa capitale, Pataliputra (l'actuelle Patna, Bihar). En 326 avant notre ère, alors qu'Alexandre le Grand campait près de la rivière Beas, dans la partie la plus occidentale de l'Inde, son armée se mutina et refusa de marcher plus à l'est. Ils avaient entendu parler du grand royaume de Magadha et étaient troublés par les récits de sa puissance. À contre-cœur, Alexandre fit demi-tour (et mourut en route). Mais ce n'était pas la première fois que la puissance de Magadha forçait des rois à se diriger vers l'ouest. L'une des premières références à Magadha se trouve dans l'épopée du Mahabharata, où l'on voit l'ensemble du clan Yadava abandonner sa terre natale des plaines du Gange pour migrer vers le sud-ouest, en direction du désert et de l'océan, afin d'éviter les batailles incessantes avec son voisin oriental, le Magadha.

Lire la suite...

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

VERSE 005 ( doors to the deathless )

The doors of the deathless are open, Brahmā, for those who have ears.

They enter with veneration, devoid of hatred, the beings in Magadha listen

Suguru's teacher verse is based on a small alteration of the canonical timeline. The main difference is that the curse at Nanako and Mimiko's village was assessed to be a grade two instead of one. So Kento Nanami was dispatched in Suguru's stead. This then leads to a chain of events that eventually land Suguru in Kyoto as a teacher. But before I venture into what I will portray Suguru's disposition to be like in this verse, I wanted to clarify something else about my portrayal.

Suguru's built up frustration was never directed towards jujutsu society. Unlike Gojo, who believes the higher-ups' schemes are to blame, Geto saw a greater problem that referred to the practice of jujutsu in general ( as long as non-sorcerers keep producing curses, jujutsu sorcerers will keep dying thankless deaths to protect them) Suguru himself has always expressed contempt towards those weaker than him in canon. However, being the other side of the coin to Gojo's vanity, this contempt translated to a responsibility to protect them, justifying the power imbalance and the suffering he had to endure.

I as a writer subscribe to this interpretation of the character and as a result Suguru's contemptuous attitude towards nonshamans continues to be evident in this verse. However, since there was one less violent experience throughout his downward spiral ( poor Nanami takes the blow instead ;~; ) we can say the proverbial glass of his hatred towards them was filled to the brim but did not overspill.

VERSE SUMMARY:

Suguru is a special training teacher in Kyoto High. Albeit his specialty being martial arts, he is very knowledgeable when it comes to curses and utilizes his technique to create simulations for his students to practice. Suguru is known for his whimsical teaching style and prompting his students to think on their ideals and goals through practicing jujutsu. Much like his Tokyo counterpart, Satoru, his practices are frowned upon by the higher-ups and he is considered a bit of a wild card, especially because of how liberally he expresses his dislike for non-shamans.

This verse will primarily be used to build dynamics with muses that can't interact much in the canon timeline as well as explore 'what-if' scenarios. Kenjaku will not be present in this verse.

Suguru's default age for this verse is 27 years old. As this is just a skeleton for the verse, the status of Mimiko and Nanako's adoption is left vague ( either took custody of them from Nanami, they are being raised in Tokyo High, they are being raised by Gojo, etc etc ) Suguru's parents are also alive in this verse ( so if anyone wants to ask for his hand in marriage you'll need permission )

Verse Timeline & Tidbits under the cut.

VERSE TIMELINE:

March-May 2006: Riko Amanai is assassinated by Toji Fushiguro. Suguru takes in his cursed inventory spirit.

Summer of 2006: Suguru begins to develop severe PTSD symptoms as a result of the encounter.

Autumn of 2006-Winter of 2007: Suguru's mental health is at a steady decline, worsened by the consumption of curses and isolation from his friend group.

August 2007: Satoru Gojo officially becomes The Strongest. Suguru's mental health has tanked severely in the previous months. A conversation with Yuki Tsukumo leads him to the inevitable conclusion that the root of the problem are non-sorcerers. Whilst bidding goodbye, Yuki tells him that a new vessel has been found for Tengen.

September 2007: Suguru is sent on a mission that is soon discovered to be staged by TVA members in order to attain Tengen's new appointed vessel. That tips the glass for Suguru, leading him to annihilate the cult's members instead of taking over — automatically being branded as dangerous and ordered for execution. A petition is signed by Jujutsu High staff members to settle a court date before the execution takes place.

October 2007: His friends and juniors vouch for Suguru's integrity and buy out his freedom, in exchange for limitations on his cursed technique. Suguru is given the choice to either retire from the frontlines and instead be given a teaching job after he graduates with a binding vow/cap on his own cursed technique, or be executed. He goes with the second option, but Gojo interferes and essentially backs him up into a teaching job. That inevitably drives a wedge between the two best friends. aka they break up in front of the KFC still

2010: Suguru officially graduates highschool and is appointed as a special training teacher in Kyoto.

CURSED TECHNIQUE BINDING VOW:

After trial, the higher-ups forced Suguru to take a binding vow that limits him from using his cursed technique, unless he or another sorcerer is under imminent threat. That implies there would always need to be another sorcerer present in order for Suguru to summon spirits, thus he'd only be able to use jujutsu under supervision. Windows and affiliates are included in this vow.

In addition, he cannot use Maximum: Uzumaki without sacrificing his own life in the process. If utilized, Uzumaki will be performed at a 300% of its standard power, but Suguru will be consumed by it first, similarly to how Mahoraga works, yet not exactly. Suguru has figured out a way to merge cursed spirits on his own accord, however there are limitations in regards to the power level of the outcome.

RELATIONSHIP WITH THE STUDENTS:

Suguru is not exactly a favorite among the students, although he is the one they flock to for most of their troubles. He has a great relationship with Noritoshi and a rocky one with Mai Zenin, especially after publicly declaring that he refuses to train her. Momo also dislikes him for that reason.

TIDBITS & CHARACTER QUIRKS:

Suguru is known for his impossibly hard training regimens. He's quite brutal when it comes to discipline routines.

Suguru maintains a relationship with Yuki in this verse, often texting back and forth or meeting up to talk outside of work. Yuki has scouted students for him at times. It's a colleague based thing. He still hasn't answered her question as to his type.

Once per year Suguru travels back to Tokyo with a heavy heart to participate in the exchange event with his students. He hates the teacher nomikai parties.

Suguru has a pet cat-like curse based on the bakeneko yokai. He has named her Wasabi. This curse is non-hostile unless the user is threatened, wears a napkin on its head and does little dances.

In addition, Suguru has kept Fushiguro's inventory spirit and does sometimes utilize it, although usually he keeps it in its shrunk form in his uniform pocket.

Suguru will still accompany his students on missions at times, in order to watch over them. His consumption of curses is very gradual and rare, technically forbidden by the higher-ups, however Suguru still makes pacts with his students to acquire higher grade cursed spirits with the pretext of ensuring they won't be respawning if consumed.

He has his own room in the Kyoto High dormitory.

#( i was gonna sit my butt down and draw for this but i wanted to rush it bc im already using this verse w peeps so- )#VERSE INFO.#꧕ 🇩🇴🇴🇷🇸 🇹🇴 🇹🇭🇪 🇩🇪🇦🇹🇭🇱🇪🇸🇸 ꒰ ᴠᴇʀꜱᴇ 005 ꒱

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The story of the young weaver - 01

Dhammapada contains 423 verses said by the Buddha in different contexts. Most of the verses have been taken from the discourses of the Buddha. It has been noted that more than two thirds of the verses are taken from the discourses contained in the two collections of the Buddha's discourses known as the Samyutta Nikaya and Anguttara Nikaya. The 423 verses are divided into 26 chapters each with a particular heading. The thirteenth chapter is named "Loka vagga" meaning the chapter on

"the World", which contains 12 verses said by the Buddha.

The back ground story to the 8th verse of the Loka vagga is about a weaver girl who used to practise reflection of death after listening to a sermon from the Buddha.

At one time, the Buddha was staying in Alavi at the Aggalava shrine. The country of Alavi was located between Savatti of Kosala and Rajagaha of Magadha in ancient India. The town of Alavi became well known in the Buddhist literature as Alavaka the Yakkha who is mentioned in the Alava sutta and one of the Buddha's chief male disciples known as Hatthaka Alavaka used to live there.

While staying in the town, the Buddha was delivering a sermon where, the Buddha was describing the impermanence of the five aggregates of clinging that a person is made of and advising the disciples to reflect on impermanence and inevitable death as follows:

My life is uncertain,

My death is certain,

I must certainly die,

My life ends in death,

Life is uncertain,

Death is certain.

The Buddha also stated: "Just like one who is armed with a stick or a spear meets with a poisonous snake, one should always be mindful of death so that one will face one's death mindfully. He will then leave this world to be born at a good destination."

Most of the audience did not heed to the Buddha's advice but there was a sixteen year girl in the audience who happened to be the daughter of a weaver. She understood the Buddha's message on uncertainty of life and the certainty of death and decided to practise reflection on death regularly. She continuously contemplated on what the Buddha taught for three years.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, so...um, I was doing some research, and in general, there are 9 wives of the Pandavas: Draupadi, Hidimba, Devika, Uloopi, Valandhara, Chitrangada, Subhadra, Karenumati, Vijaya, right?

In BORI CE, there is an unnamed princess who is mentioned as the wife of Bheem, who is also the sister of a monarch who always used to challenge Krishna. In the same para, it is stated that the princess of Magadha married Sahadeva. Also, in Harivamsa, it is mentioned that Bhanumati, daughter of Bhanu, a Yadava chieftain (not Krishna's son) married Sahadeva as well..... What do you think about this? Many people on wattpad are getting confused regarding this, and I wanna know your take on this topic...also, Do you believe that characters like Vatsala (who is only present in Tamil and Telugu folk plays, not even an authentic book), Suthanu, Pragati, Pragya, Samyukthana, Printha, Sumitra and Bhargavi exist?

Bhargavi is the daughter of ArSu in some versions, the rest are Draupadi's daughters....

Hi anon,

This can all get a bit complicated, but the main thing to remember here is:

The Pandavas were princes, and, as such, it’s likely they had several unknown wives whom we lost in the lore over time, partly because of their irrelevance to the overall narrative.

(I hate that I used the word “irrelevance”, but.)

In addition, the opposite may also be true; because of the popularity of the epic (and the Pandavas in it), many cultures around the world possibly came to associate their local histories with the princes. The result is several partners being mentioned more regionally than universally.

While I do leave room in my views to learn about and consider these things, many of my headcanons (which affect what I write and relay) about this subject were formed in my initial years with the epic:

I typically only incorporate the nine wives you have listed into my work.

Similarly, because I had heard of Suthanu and Pragati before the other daughters (I have only found the Pandavas’ daughters in regional takes), I include only them.

My aim is to keep myself from getting too overwhelmed by the information - even if that somewhat limits me.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I've got Not Quite Dyslexia (ADHD processing issues tested so badly that they're functionally dyslexia) yeah?

Well I've been reading Ahsoka as Ashoka this whole time.

And I've been desparately trying to figure out why they made a show about Ashoka, popularly known as Ashoka the Great, the third Mauryan Emperor of Magadha in the Indian subcontinent during c. 268 to 232 BCE, and why tf my Beloved Mutuals™ were so concerned about this

2 notes

·

View notes