#louis capet is a man

Text

I apologize for this live read of Convention minutes, but fuuuu I forgot that SJ totally says "Louis XVI" in his vote for the death. (Instead of Louis Capet).

#power move#because they are not deciding what happens to a man#but a king#louis capet is a man#he is condemning louis xvi the king#i need a moment how come i never caught this before#frev#saint-just#louis xvi

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

long post, because i'm confused and need help from my mutuals.

this. this really confused me. more well-read mutuals help me if you can:

i'm mostly sure "suggesting a constitutional monarchy" was not the sole reason de gouges was arrested, tried, and executed, and it could not be the main reason. jean-paul marat was once a supporter of constitutional monarchy. Supplément de l’Offrande à la patrie did end with a message of hope for louis xvi to sort every grievance out while still being king. (and it was not just marat, this support for constitutional monarchy was widespread before louis xvi made the questionable decision to attempt to flee the country.) de gouges was executed after louis capet was, and the possibility of having a constitutional monarchy by then was certainly not as high.

i'm not so sure about what is meant by "anarchist beheadings". beheading as a method of execution is not anarchist on its own. beheading existed before frev, as did many, many other types of executions. the english did in ireland some of those other types of executions during the last 10 years of the 18th century, that is to say, at the same time as the frev happened. and we do not use the word "anarchist" to describe english attempts at disproportionately criminalising the irish. so putting the word "anarchist" immediately next to "beheadings" is something i genuinely cannot figure out on my own.

national assembly (20 Jun - 9 Jul 1789),

national constitutional assembly (the one that michel lepeletier worked in, 9 Jul 1789 - 30 Sep 1791),

legislative assembly (the one that made divorce far more accessible than before, 1 Oct 1791 - 20 Sep 1792),

and the national convention (21 Sep 1792 - 26 Oct 1795).

i don't think there was 1 position on the rights of women in any of these four. afaik the jacobins themselves were divided on how much social equality women could achieve. and the brissotins made the questionable decision to declare war on austria, which did not just mean that a very disorganised army was to be put into action, but that working-class women's lives were then affected by inflation and possible hoarding-and-profiteering of grains and of necessities.

again i have much more reading to do on this one.

many more women (e.g. louise-renée leduc, claire lacombe, pauline léon, théroigne de méricourt, félicité fernig, théophile fernig) had more stakes in the frev than de gouges did. often they would put their very lives on the line. their perceived femininity was not their primary concern, e.g. the fernig sisters kept being soldiers even when other soldiers were aware that they were women.

maybe as a tangent: mary wollstonecraft, despite her criticism towards the frev, was still much, much more welcoming of the frev than her theoretical opponent, edmund burke, and her A Vindication of the Rights of Woman was translated into french within a year of being published. wollstonecraft lived in paris from 1792 to 1795, and was not persecuted (partly due to the protection of an american man, but still if any suspicion came upon wollstonecraft, it would be because she was english, not because she was a woman or a feminist thinker).

with the exception of leduc, every woman mentioned here died after 1793. now i am aware that this is a small sample size, and misogyny definitely existed during the 18th century (not surprisingly), but i cannot find in any primary source evidence suggesting the existence of a systematic exclusion of outspoken women or women of action or feminist thinkers.

i am aware that suffrage and/or being part of the national assembly (later national constituent assembly, later legislative assembly, later national convention) were not the only ways of participating in politics. working-class women in the 18th century not having the right to vote was sad when compared to working-class women in the 21st century having this right. but they were allowed to influence the men in their communities to vote, which was fortunate when compared to the lack of the right to vote in general in the old regime.

my general grasp so far is that, any kind of written or spoken output during the frev had very real risks attached, because literacy was quite low, and many "readers" of newspapers or pamphlets heard the contents by others retelling what was read out at cafés. spreading misinformation, or using gross invectives as marat called it, was not just unhelpful, but possibly damaging to the organisation of the urban poor.

now personally i do not believe that de gouges deserved to be executed, but that is because i do not believe anybody deserved or deserves to be executed. (that's for a different post.)

if male journalists such as hébert were losing their lives for misleading their readers and for unnecessary verbal violence, however, then de gouges being subjected to similar levels of scrutiny was a sign of equality -- for men and women of letters at the very least.

voting rights for women being granted only in the 1940s was

a) still a good thing. that it happened at all was a good thing. that it is still here is a good thing.

and

b) the result of feminist thoughts coinciding with economic and political realities. between the frev and the 1940s were three republics and two empires, and it would be reductive to blame what was delayed until the 1940s solely on the frev. feminism, as a group of schools of thoughts, did not doom itself because de gouges died.

and

c) still not equality yet. voting allows, but only allows, more women to think about the state that exercises disproportionate power over them, and to describe this state, and to study this state. i am reminded of a quote from dear Karl here.

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have proof Robspierre opposed what happened in the towns of Nantes and Lyon? Because as far as I know (and I'm no expert) there's no account of him being explicitly against what happened there, except the argument he had with Fouché in Carlotte Robespierre's mémoirs. Sorry if my question bothered you, I'm just trying to understand the whole situation.

We know Robespierre spearheaded the motion to have Carrier (the man who was in charge of the army at Nantes when the mass killings happened, and who is generally agreed to be responsible for them) recalled and removed from his position. We also know that he was against the violent dechristianizers, whom he called "fanatics".

With Fouché, the main source is Charlotte Robespierre's memoirs, and memoirs can be tricky with authentication, but I'm inclined to believe it because it lines up with the circumstances and what we know of both men. Something must've happened between the two of them for Fouché to feel so genuinely threatened by Robespierre, and we know that Robespierre abhorred excessive violence (he refused to watch executions, for example, and advocated against trying to bring the revolution to other countries through war), as well as the dechristianization movement, which he saw as both needlessly destructive and an affront to religious freedom.

Robespierre was very uncompromising when it came to actions he deemed immoral by government members (and honestly, mass slaughter is usually considered immoral by most people). He was famous for being "incorruptible" (read: not taking bribes) and due to that, there was no way to shut him up if he found out you were abusing your position, other than killing him off. So Fouché must've been scared of Robespierre exposing something about him, and the fact that he participated in semi-legal extrajudicial massacres seems a likely candidate.

Also a lot of his rhetoric in speeches hints about his complicated position on revolutionary violence. Oftentimes he condones some form of violence (like the execution of Louis Capet), but he usually tempers it with some condition about only doing it when absolutely necessary (i.e. terror without virtue is fatal). He also signed relatively few arrest warrants compared to most of his colleagues on the CSP, and was famously reluctant to arrest several people until there was better proof of their guilt (Danton and Desmoulins come to mind here; he eventually did agree to put them on trial but only after trying to dissuade Desmoulins from lawbreaking multiple times). So if he was that careful about even sending someone to trial, it's only logical that he would not be a fan of summary execution.

Sorry if this is long or if it seems like beating around the bush, I have neither the time nor the knowledge of 18th century French style/grammar conventions to comb through all the relevant documents and speeches that might hold more conclusive proof. But TL;DR: he definitely opposed Carrier's actions in Nantes, and it's very likely from what we know of his ideological positions that Fouché's actions in Lyon drove a wedge between the two as well.

(Any other French Rev folks who want to add on with more sources feel free)

#this is LONG sorry#speech for the convention for three and a half hours#you know the drill#/ref#french revolution#frev#robespierre#asks#anon#pigeon.txt#sourced

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles Mountbatten-Windsor has been crowned, by the Grace of God, King of the United Kingdom and His other Realms. Great and egregious expense has gone towards the requisite magics, gone to pay for the actors and costumes required for performing the long-since written play. The ideological farce is done, and this walking survival sits anointed above the United Kingdom, this bastard monarchy unbefitting of the union of British nations it claims to be. Do not mistake the compliant client media and reprehensible political class for a true representation of the country: a great many of us are hungry and angry and want the whole thing burned to the ground. The pageantry is a distraction, as much for themselves as for anyone else. They rule atop a fragile semblance of order that, in the coming decades, will be pushed beyond its fettered limits by forces outside its control. But it is worth remembering that there was once a time when England dared to dream for something better, dared to fight, dared to win:— that there was once a time when England and the whole Isles was a republic, commonwealth, and free state.

A revolutionary army of the downtrodden and the oppressed fought for England to be free from kings and popes, for the wealth of this land to be held in common, for its leaders to belong to the people. This army defeated those who opposed it, both in revolutionary war to take power and in a coup d’état to purge the government of those who would not follow through on the victory. 374 years ago, a king of England, Scotland, and Ireland—a man the revolution called Charles Stuart, an act of glorious contempt to later be echoed by the lèse-majesté of the French address “Citizen Louis Capet”—was tried by a revolutionary tribunal for crimes against the people, found guilty of tyranny, treason, and murder, and executed. What ecstasy the common people must have felt that day! To see the heavens evaporate and all the possibilities of history open up to you now the divinely ordained tyranny was ended! To have sought the impossible and succeeded!

The tragedy of England is that her revolution died in its success: unable to cut the Gordian knot of the balancing act between aristocracy, bourgeoisie, and common people, and therefore unable to go far enough to secure its long-term survival by breaking the power of the nobility once and for all, the regime never found real stability, the radicals were sidelined, promises were broken, and all that had been achieved slowed to an inertia and a Restoration. But for a decade the British Isles were free from the stain of monarchy, and even at the last moment, as it all came crashing down around them, the loyal revolutionaries were willing to fight and tried to resist. The revolution ended, as it were, in the person of Daniel Axtell: a fervent revolutionary who had participated in the coup against the Long Parliament and served as captain of the guard during the trial of Charles Stuart, Axtell went to his death on the scaffold—went to be hung, drawn and quartered by the counterrevolution—unrepentant and proud, promising: ‘If I had a thousand lives, I could lay them all down for the Cause.’ The name of the Good Old Cause was still in the psyche of working-class politics in Britain as late as the nineteenth century and the Chartist movement.

How did it all come to this? Britain is a green and pleasant land, bleached white-yellow by the dying its masters have inflicted upon the earth; an island nation, fed by raging seas and rivers flowing off the snow-capped mountains and through the hedge-lined fields, that has been turned to a land of drought and shit-filled waterways; a rich country, grown fat off plunder and war and exploitation, in which a third of its children are malnourished; a country which led the world in rejecting the feudal order, in fighting for something new and free and good, which is today one of the most backwards regimes on earth and the most fragile and decrepit member of the imperialist chain that still encircles the world. Capitalism was born here. One day, it will die here. And when it does, the British people will have rediscovered the radicalism with which they once led history, and proclaimed again that their state will be a commonwealth, belonging to the working people, without a king or a house of lords. And when they do, we can look back and smile, knowing that we have relegated the likes of Charles and his palaces to oblivion. Should we ever get the chance, with delight and in the memory of those who came before us, we shall make no excuses for the terror, and for the republic: ‘We have no compassion and we ask no compassion from you. When our turn comes, we shall not make excuses for the terror. But the royal terrorists, the terrorists by the grace of God and the law, are in practice brutal, disdainful, and mean, in theory cowardly, secretive, and deceitful, and in both respects disreputable.’

#history#politics#socialism#leftism#communism#marxism#charles iii#united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

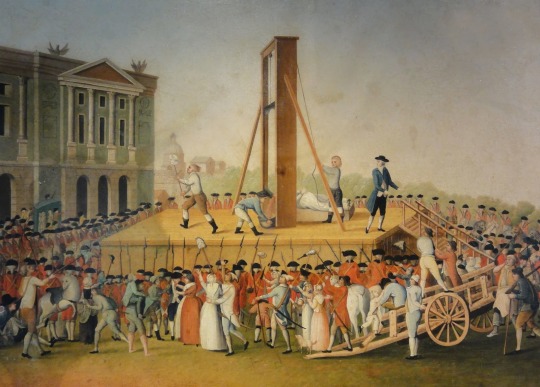

Contemporary descriptions of the Robespierrist execution compilation

(from description closest in time to the execution to the one furthest away)

Today, Monday afternoon, Robespierre and his 21 conspirators are taken to the Revolutionary Tribunal to have their condemnation confirmed, because, being outlaws, their trial is over. It is decreed that they will be put to death at Place Louis XV, today Place de la Révolution. They were taken there and passed along rue Saint-Honoré and everywhere they were insulted by the people, indignant at seeing how they had deceived them. And they had their heads cut off at 7 o'clock in the evening. In 24 hours it was done; they hardly expected to die so quickly, those who wanted to massacre 60 000 men in Paris. This is how God lets the scoundrels, at the moment of executing their projects, perish. Robespierre was the soul of the conspiracy with another villain, Couthon, who assisted him. It is said that he wanted to recognize himself as King in Lyon and in other departments and marry Capet's daughter. How can a private individual put such a project in his head? Ambitious villain, that's where your pride has led you. With him dying as leader of the conspiracy, everything falls with him.

Journal de Célestin Guittard de Floriban, bourgeois de Paris, sous la Révolution, présenté et commenté par Raymond Aubert (1974) page 437-438. Cited in Comment Sortir de la Terreur - Thermidor et la Révolution. Diary entry July 28 1794.

It was around six o'clock in the evening that the tyrant and twenty-one of his principal accomplices left the Conciergerie to advance towards the scaffold. They were in three tumbrils: Hanriot, drunk, as usual, was beside Robespierre the younger; the tyrant was next to Dumas, the instrument of his fury; Saint-Just sat close to the mayor of Paris; Couthon was in the third tumbril. Hanriot and Robespierre the younger had their heads smashed and were covered in blood; Couthon had a bandeau; the tyrant had his whole head, except his face, bandaged, because he had received a pistol shot in the jaw. It is not given to a man to be more hideous and more cowardly: he was dull and downcast. Some compared him to a muzzled tiger, others to Cromwell's valet, for he no longer had the countenance of Cromwell himself. All those around him had, like him, lost their audacity. Their baseness added to the indignation against them. We remembered that, at least, the conspirators who preceded them had known how to die. They did not even have the strength to speak to each other, nor to address the slightest word to the people. The crowd was innumerable; the accents of joy, the applause, the cries of: A bas le tyran! Vive la République!, imprecations of all kinds resounded from all sides along the way. The people thus avenged themselves for the eulogies commanded by terror, or for the homage usurped by a long hypocrisy. It was about half past seven when the traitors arrived at the Place de la Revolution. Couthon was executed first; then Robespierre younger; the head of the tyrant was the penultimate, and that of Fleuriot Lescot the last. They were shown to the people, who made the air resound with long prolonged cries of Vive la Convention! Vive la République!”

Suite de journal de Perlet number 675 (July 30 1794)

From 11 Thermidor — Yesterday, around half-past seven in the evening, the twenty-two conspirators arrived at the place of execution, Place de la Révolution, amid prolonged and unanimous cries of Vive la République! Robespierre the elder had his head wrapped in a bandage and bloodied from a pistol shot he had fired at himself when he saw himself abandoned by the traitors Hanriot had arranged for him. This one was also all scarred on the face and injured in the arms from the defense he had put up against the gendarmes responsible for arresting him. Only Lebas, former deputy, killed himself. The heads of Robespierre, Hanriot, Dumas and a few others were shown to the people, who, during the whole course of the journey of these infamous conspirators, from the Palais de Justice to the scaffold, bore witness to them in the most energetic of all its indignation and all its horror.

Courrier républican, July 30 1794

It was the evening before last, at seven o'clock, that Maximilien Robespierre, his brother, Saint-Just, Couthon, Hanriot, Fleuriot, mayor, Payan, national agent, Dumas, Lavaleyte, Coffinhal, Bernard, Gobeau, Geney, Vivier, Simon, Laurent, Wouarmé, Forestier, Guérin, D'Hazard, Bourgon and Quenet, municipal, were executed. Lebas had killed himself. Never have we seen such a crowd of people as at this performance. Women, children, old people, all of Paris was there. Who could return the joy which burst on all faces? In all the streets through which the conspirators passed, in the whole extent of the Place de la Révolution, everywhere there was only a unanimous cry: Ah! the scoundrels! Vive la République! Vive la Convention! and all the hats were up in the air in satisfaction. Eyes were particularly fixed on Maximilien Robespierre, Couthon and Hanriot, whose heads were bloody from the wounds they had received at the time of their arrest.

Annales de la République française, July 30 1794

The torment of a tyrant is truly a feast for the world. The French have made it a decade-long celebration, and the joy of yesterday proved how long and strong the oppression had been under which all souls, all hearts, all spirits had groaned. Yes, public joy developed yesterday in all its fullness and guarantees us freedom forever. Neither the punishment of Louis XVI, nor that of his wife and of all the traitors who have since suffered the fate of treason, nor any celebration, not even those of victories, had had so many spectators, had inspired a joy as felt, as universal, as expansive as the misery of Robespierre, Couthon, Saint-Just, etc. How horrible must the long passage from the Palais de Justice to the Place de la Révolution, in front of an immense people applauding, shouting incessantly: Vive la République! Perish the traitors and the hypocrites always speaking of virtue, and having crime in their hearts! have been for them (if they were still susceptible to any shame). If they had been able to see in the National Garden all the citizens returning from their torture, throwing themselves into each other's arms, embracing each other, congratulating each other on finally being delivered from an odious yoke, crying out , repeating everywhere: ”Finally, we are free, we will no longer poison our thoughts, our intentions; our mistakes will no longer be turned into crimes; the interior of our households will at least be a safe haven against the espionage of denunciation; sweet intimacy, brotherhood, friendship and their consoling charms will be returned to us; the tyrant is no more!” If they could have seen all this, I say, they would have shuddered with rage at having so grossly deceived themselves by counting on a perished people to serve their projects of domination and subjugation.

Journal des hommes libres de tous les pays, July 31 1794.

Robespierre and his principal accomplices had been arrested towards the middle of the night between 9th and 10th Thermidor. They were handed over to the executioners on the morning of the 10th. The procession left the Palace of Justice, and set off about five o'clock in the evening. Never had one seen, on the passage of the tortured, such an influx of people. The streets were clogged. Spectators of all ages and sexes filled the windows; men were seen climbing up to the tops of the houses. Joy was universal. It manifested itself with a kind of fury. The more the hatred felt for these scoundrels was suppressed, the louder the explosion. Everyone saw in them his enemies. Everyone applauded drunkenly, and seemed to regret not being able to applaud more. One thanked Heaven, one blessed the Convention. The horsemen who escorted the patients shared the universal joy; one even saw, in this meeting, what one had never seen before: these horsemen waved their sabers in sign of joy, and accompanied this movement with the cry: Vive la Convention! Eyes were especially attached to the cart which carried the two Robespierres, Couthon and Hanriot. These poor things, mutilated and covered with blood, resembled bandits whom gendarmes had surprised in a wood, and could therefore only seize by wounding them. Robespierre, extraordinarily pale, and covered with the same coat he wore on the day when he had dared to proclaim, at the Champ de Mars, the existence of the Supreme Being, lowered his eyes, and leaned his head, which looked horribly deformed by the dirty, bloody linen that enveloped him, on his chest. Hanriot, having no clothing but a shirt and a waistcoat, was covered with mire and blood. His hair, his bloody hands, the eye which was only held together by filaments, formed a picture so disgusting and so appalling, that one didn’t dare to stare at him for a long time. “Here he is, here he is,” said the people, “as he was when he left St-Firmin, after having cut the throats of the priests there!” Robespierre the younger and Couthon were likewise disfigured by bruises, and covered with blood. The horrible deformity with which all these unfortunates presented themselves to the eyes of their fellow citizens at the last moment of their lives, appeared to even the least religious man a chastisement from heaven. Men, in fact, who after having bathed in blood, were completely defiled by descending to the tomb, testified in a striking manner that divine justice exercised its terrible vengeance on them, and wished to inspire great horror in their assassinations. The procession having arrived in front of the house where Robespierre was staying, the people compelled the executioners to stop. They obeyed. A group of women then performed a dance in front of the cart carrying Robespierre. When the patients had reached the middle of the former royal street which leads to the execution, a woman of middle age, neatly dressed, and showing by her manners and her countenance an education above the common, sprung from the crowd , seized with one hand the bars of the cart where Robespierre was, and threatened him with the other, and cried to him: "Monster spewed up from hell, your supplication intoxicates me with joy. I have only one regret, you don't have a thousand lives to enjoy the pleasure of seeing them all snatched one after the other. Go away, scoundrel; descend to the tomb with the curses of all the wives, of all the mothers!” Robespierre had without a doubt deprived this woman of a husband or son. He looked languidly at her, and without saying a word, shrugged. On the scaffold, Robespierre had a new suffering to endure. The executioner, before stretching him out on the board where he was going to receive death, abruptly tore from him the bandage placed on his wounds. The lower jaw was thus detached from the upper jaw, causing waves of blood to flow, which made the head of this unfortunate man a monstrous object. When this head had been cut off, it presented the most horrible picture that one can paint. Hanriot had to suffer a no less painful torture: one of the executioner's servants, before he mounted the scaffold, brutally tore out his eye where he had been wounded. Each falling head excited loud applause. The number of those executed that day was twenty-two.

Histoire de la conjuration de Maximilien Robespierre (1795) page 221-225. The descriptor, Galart de Montjoie, was 48 years old by the time of the execution. According to wikipedia, he was forced to go into hiding in Bièvres in April 1793 due to writing royalist pamplets. This means he might not have actually been an eye witness during thermidor.

At four o'clock in the evening the sinister procession left the courtyard of the palace. Never have we seen such an affluence of people. The streets were clogged. Spectators of all ages and sexes filled the windows; men were seen climbing up to the tops of the houses. Joy was universal. It manifested itself with a kind of fury. The more the hatred felt for these scoundrels was suppressed, the louder the explosion. Everyone saw in them his enemies. Everyone applauded drunkenly, and seemed to regret not being able to applaud more. Eyes were especially attached to the cart which carried the two Robespierres, Couthon and Hanriot. These poor things, mutilated and covered with blood, resembled bandits whom gendarmes had surprised in a wood, and could therefore only seize by wounding them. It was noticed that Robespierre had, in going to scaffold, the same tailcoat as he had had on the day when he had proclaimed the existence of the Supreme Being at the Champ de Mars. It is difficult to paint his appearance. Nothing recalled the idea of the supreme power which he exercised twenty-four hours earlier. He was no longer the tyrant of the Jacobins, nor the insolent ruler of the Convention; he was a wretch, whose face was half covered by a dirty and bloody linen. What one perceived of his features was horribly disfigured. A livid paleness completed his frightful appearance. Whether he was overwhelmed by the pains caused by his wounds, or whether his soul was disheartened by the remorse caused by the memory of his crimes, he affected to have his eyes lowered and almost closed. It was in this condition that he crossed the streets and Rue Saint-Honoré. Arriving in the middle of the former royal street, he was pulled from the lethargy in which he was by a circumstance which deserves to be preserved by history. A woman was waiting for him in this place. She was neatly dressed and of middle age. Seeing the tumbrel carrying Robespierre, she pushed through the crowd and seized the bars of the tumbrel with one of her hands. The countenance and expression of this woman announced that she had received the best education. Attached to the tumbrel by one of her hands and shaking Robespierre with the other, she cried out to him: "Monster spewed up from hell, your supplication intoxicates me with joy." At these words, Robespierre half opened his eyes and shrugged his shoulders. “Abominable monster,” continued this woman, ”I have only one regret, you don't have a thousand lives to enjoy the pleasure of seeing them all snatched one after the other. ” This new apostrophe seemed to importune Robespierre; but he did not open his eyes. Then the brave woman said to him as she left him near the scaffold: ”Go away, scoundrel; descend to the tomb with the curses of all the wives, of all the mothers!” It has been presumed that Robespierre saw this woman deprived of a husband or a son. Her painful accents must have penetrated his soul. This moral torture was no doubt very weak to expiate crimes as enormous as those of which Robespierre had been guilty; but it was at least a satisfaction for sensitive souls to learn that this monster had experienced it, and that it had been able to increase the horror of the too severe torture which he had to undergo. When the tumbril arrived at the foot of the scaffold, the executioner’s assistants lifted down the tyrant and laid him on the ground until it was his turn to meet death. One observed that during the time his accomplices were being executed, he didn’t show any sign of sensibility. His eyes were constantly closed, and he didn’t reopen them until he felt himself transported to the scaffold. They say that in perceiving the fatal instrument he uttered a painful sigh, but before receiving death, he had a cruel suffering to endure. After having thrown away his tailcoat, which was crossed over his shoulders, the executioner teared off the bandage that the surgeon had put on his wounds. The lower jaw was thus detached from the upper jaw, causing waves of blood to flow, the head of this poor thing wasn’t more than a monstrous and disgusting object. Once this appalling head had been cut off, and the executioner took it by the hair to show it to the people, it was the most horrible image one can imagiene.

Les Crimes de Robespierre et de ses principeax complices (1797) page 121-126. The descriptor, Nicolas Toussaint Le Moyne Des Essarts (1744-1810), was 49 by the time of the execution. This is clearly a variation of Montjoie’s account to some extent.

Where shall I find the true colors with which to paint a picture of the public happiness that existed in the midst of this terrible spectacle, to describe the explosion of burning joy that spread and resounded as far as the scaffold itself? His name, accompanied by curses, is in every mouth; they no longer called him the Incorruptible, the virtuous Robespierre, the mask has fallen away. They execrate him, they blame him for every crime of both committees, they surge forward from the shops, boutiques, and windows. Rooftops are covered with people, thronged by a huge mob of spectators drawn from every class of society, all with only one desire, to see his death. Instead of sitting on a dictator’s throne, he is half-sitting, half-lying in the tumbrel that also holds his accomplices, Couthon and Hanriot. The noise and tumult that accompanies him is composed of a thousand cries and mutual congratulation. His head is enveloped in dirty bloodstained bandages; only half of his pale, ferocious face is visible. His mutilated, disfigured companions look less like animals than wild beasts caught in a trap. Even the burning sun cannot deter the women from exposing the lilies and roses of their delicate cheeks to its rays; they want to see the executioner of these citizens… On the scaffold, the executioner, as if spurred by the public’s hatred, roughly tears away the bandage covering his wounds; he roars like a tiger; his lower jaw snaps off from the upper jaw and blood spurts out, changing this human head into the head of a monster, the most horrible sight imaginable. His two companions, no less hideous in their torn, bloodstained clothing, were the acolytes of this famous criminal, for whose suffering no one can summon a vestige of pity… The crowd surged forward, so as not to miss witnessing the exact second when his head would go beneath the blade, that blade to which he himself had sent so many others. The applause lasted for more than fifteen minutes. 22 heads fell with his.”

Le nouveau Paris (1797) volume 6 page 101-104. The descriptor, Louis-Sébastin Mercier (1740-1814) was 54 by the time of the execution. Note that he was actually in prison during Thermidor, and thus cannot really be considered an eye witness.

Taken to the Conciergerie, and a few hours later brought before the Revolutionary Tribunal, which was only to establish his identity, he (Saint-Just) was sent to the scaffold on the evening of 10 Thermidor (July 28, 1794). He marched to the execution with calm and firmness, casting his gaze disdainfully over the immense crowd which served as his escort, and seeming entirely insensitive to the vociferations of the multitude, as well as to the insults heaped upon him by some men who, a few days before, were his accomplices or the servile instruments of his crimes. When his guilty head fell on the scaffold, which he himself had so long watered with innocent blood, Saint-Just was still only 26 and a half years old.

Biographie nouvelle des contemporains (1827) volume 18 page 558. The descriptor, Antoine Vincent Arnault, was 28 by the time of the execution.

The pen can only give an imperfect idea of what passed around this poor thing, from the tribunal, where his identity was ascertained, to the place where he satisfied the national vindictiveness. On this road, still deserted the day before when the condemned men passed by, everywhere he met the crowd who, to see him, crowded under the wheels of the tumbrel, slowing down its progress. There wasn’t a look that didn't strike him down, a mouth that didn't insult him, a fist that didn't rise to threaten him. The tongues, so long chained, were loosed; hatred had broken the silence which terror had commanded for twenty months; and as each had only a short time to satisfy such long resentments, each hastened to expectorate the curses heaped up for so long in his heart. Terrifying concert! We had never seen the example of such unanimity: no voice rose to pity him; no face expressed compassion; and yet he was in a pitiful state! A pistol shot had shattered his head, leaving him only enough life to suffer, to feel the pain of his wound and the terror of his inevitable fate. Isolated in the midst of his party, he did not even have the friends that crime gives. Struck with the same blow as he, his accomplices had no more pity for him than he had pity for them. As ferocious as everyone else, I ran to the place of execution, less, however, to feast my eyes on the sufferings of this monster than to convince myself with my eyes of the death of the one whose life threatened that of anything that had life. I ran there to seek certainty that he had not escaped like the day before. I found it. A cry which the pain wrung from him, when the device which covered his wound was removed, broke for the first and the last time the silence which he had kept for twenty-four hours; and at the same moment, from the same place where I had seen Danton disappear, I saw Robespierre disappear. That day did not stop the shedding of blood, but from that day, at least, innocent blood ceased to flow. Before Robespierre's head, several heads had fallen, and among others those of the proud Saint-Just, the sweet Couthon, the ignoble Henriot, and also that of Robespierre the younger, who, accomplice in his revolt, had not been of his tyranny. Public exasperation was so great on this day of revenge, that so generous a devotion, however odious its object, did not even obtain pity. No circumstance, no incident, moreover, gave the execution of Robespierre a character different from that which it was to have had. Danton is ennobled in his last moments; Danton mounted as a hero the horrible trestles to which crime had led him; his courage turned it into a theatre. There was only a scaffold for Robespierre. The universal feeling about the end of this forever execrable man is quite well expressed in this naive epitaph: “Passerby, do not mourn my fate; If I lived, you would be dead.”

Souvernirs d’un sexagénarie (1833) volume 2 page 105-108. The descriptor, Antoine Vincent Arnault, was 28 by the time of the execution.

”During the fatal journey, Robespierre’s head was wrapped in a bloody linen, so that you could see only half of his pale and livid face. The horsemen of the escort showed him with the points of their sabers to people eager to see him in this horrible state. When he had arrived at the scaffold, the executioners ripped of the bandage that supported his lower jaw, and snatched from him, with the deepest pain, the only cry that he had uttered during his long agony. This man, that his enemies without cease had represented as shy and even heartless, retained his firmness until the last moment, and fell under the blade without having given the slightest sign of terror. Saint-Just, whom Robespierre draggad with him in his downfall, died with his full constance. None of the outlaws showed weakness. With each cut of the blade, the applause testified the ferocious joy of the spectators, since long too accustumed to eagerly contemplate scenes of carnage. Maximilien Robespierre was 35, Saint-Just 26, Robespierre the younger the same age.”

Historie complète de la Révolution française (1834) volume 5 page 325-326. The descriptor, Pierre-François Tissot (1768-1854), was 26 years old by the time of the execution.

The scaffold had been erected in the Place de la Révolution. An immense crowd covered the streets where the procession was to pass, as well as the place of execution. Among Robespierre's enemies, who followed the cart in which he was dragged, and who overwhelmed him with insults and imprecations, Carrier distinguished himself by this continual and furious cry: Death to the tyrant! Robespierre and those who shared his destiny showed perfect impassivity. When he had ascended the steps of the scaffold, the executioner violently tore from him the apparatus which covered his wounds, and delivered him up for a time, pale, disfigured and bleeding, to the gaze of the multitude. 21 of his supporters were guillotined that day with him. We give their names in the lists of the Revolutionary Tribunal.

Portrait de Robespierre by anonymous, cited in Histoire Parlamentaire de la Révolution Française (1834-1838) volume 34 page 96-97

I can never forget the day of his execution. The crowd that lined the streets he passed through was immense, and the shouts of joy and vengeance were deafening. I could not make my way to witness his last moments; but it is said to have been a most horrid sight. The executioner tore off the dressings of his fractured jawbone with such brutal violence, that his roar of agony, like that of a wounded lion, or rather tiger, was heard at an incredible distance.

Recollections of Republican France 1790 to 1801 (1848) page 317. The descriptor, J.G Millingen, was twelve years old by the time of the execution.

I saw the carts containing the doomed men with their escort proceed on their way through the Rue Saint-Honoré to go to Place de la Révolution. The immense throng obstructed the streets and was an obstacle to the rapid progress of the procession, but the prevailing feeling was not only that of unanimous rejoicing, but of deliverance, and yet this feeling did not venture to break out in words and escape from the hearts so long oppressed until it had become a recorded fact that the ”head of Robespierre had really fallen on the Place de la Révolution.” The baskets of the executioner were then carries away to the cemetery of the Madeleine, and interred in the place designated as the tombe capétienne.

Memoirs of Barras, member of the directorate (1895) volume 1 page 235

#happy deathday robespierrists!#frev#frev compilation#french revolution#thermidor#maximilen robespierre#augustin robespierre#robespierre#saint-just#hanriot#couthom#georges couthon#lebas

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miraculous Lady Knight

A/N: This fic is inspired by a prompt from @hi-imgrapes. "knight in shining armor Kagami x Princess Chloe but with sass"

I hope you like this. This is probably much more historical than you expected.

~~~~

A/N: I'm only on season 3 of ML, but every character is living in 12th century france so does canon even matter at this point?

~~~~

Princess Chloe of the Capetian Dynasty is on her way to marry her beloved Adrien of Toulouse. Escorted by an entourage of knights to ensure she arrives to her destination safely. When unexpected events occur, Chloe will be left with only one knight to protect her. Kagami, an onna-musha, must now transverse hundreds of miles of unfamiliar territory, avoiding bandits and kidnappers, to deliver Princess Chloe, the most spoiled person she has ever met, to her betrothed. The biggest challenge for the duo? Trying not to kill each other before arriving.

Read Here

***

Chapter One: Utterly Ridiculous!

The year is 1142. It is the fifth year of the reign of King Louis VII of France. Tensions are rising in his kingdom, and he is at war. He hopes to gain an ally through his sister’s upcoming marriage.

***

“Ridiculous! Utterly ridiculous!” Chloe angrily strode through the castle hall, her lady’s maid trailing behind her. Two footmen stood outside her brother’s chambers, one attempted to stop her, but the girl paid no attention to them, and threw open the solid oak doors. No one, especially a lowly servant, could command her, she was a princess after all. A princess on a warpath.

“Louis!” She screamed, turning into the private offices.

“Mon Dieu, I told you not to let her in!” Cried the target of her rage, who was sitting at a desk, surrounded by his advisors.

A man wearing the simple adornments of a monk stepped forward to intercede, “My Lady, His Majesty is too busy-”

“Zip it monk!” Chloe strode up to the ornate desk, slapping her hands on it, “What is the meaning of this betrayal, brother?”

Her brother sighed, rubbing a hand across his forehead, as though he was trying to banish a headache, “Chloe I am dealing with affairs of the estate, I do not-”

“This is an affair of the estate! And it is more pressing and important than whatever charter your balding advisors are droning on about.” The comment earned her disgruntled murmurs from the men in the room.

“I am at war with the Pope!”

“And you will still be at war with the Pope next week, whereas I will be heading for Toulouse before the end of this week.” How dare her brother let his petty grievances impact the most momentous time in her life!

“Chloe-” Louis tried to interrupt her ranting.

“I was in my quarters supervising Lady Sabrine’s supervision of the maids packing my things and imagine my surprise when I learned I will not be making a detour to Champagne to purchase a new wardrobe. No, my brother Louis, King of the Franks, intends to send me to my future husband in rags!”

“You are wearing a bliaut made of the finest wool!” He gestured to her clothes, punctuating his attempt at a counter-argument.

The Princess looked down at her dress, a navy-blue pleated tunic with a flowing skirt and trumpet sleeves. A girdle made of silver accentuated her waist. She looked back up at her brother, “This is used Brother. You want me, Princess Chloe Capet, to WEAR A USED DRESS AT MY WEDDING?”

The advisors flinched at the girl’s shrieking voice, the King considered his sister for a moment, deciding on the best reply. “I must go pray.” He stood up and with a speed not quite dignified for the King of the Franks, hurried out of the room.

Chloe gathered her skirts and followed after him, “You cannot avoid me, Louis! I know where the chapel is!” Not God would not be able to spare Louis from her wrath. Why, if the Messiah had His Second Coming in this moment, Chloe knew He would take her side after seeing how badly Louis was neglecting her needs.

The King and Princess were trailed by their servants and companions, every courtier they passed stopped and bowed or curtsied in acknowledgment of the royals. Neither paid them any mind to court attendees. Louis was solely focused on seeking shelter in the chapel, gripping his rosary in his right hand, already muttering a prayer under his breath. Chloe was solely focused on berating her brother until he reversed his selfish decision.

“Why are you praying so much? You’re under an interdict.” Chloe reminded her brother.

“The interdict bans me from Church and receiving sacraments, not private prayer.” He said in an irritated voice, he was still smarting from being unable to take Communion on Sunday.

“You spend too much time in chapel, you’re not going into an ecclesiastical career anymore you know. You do not have to meet a daily quota.”

“I find it enriching.” Louis replied.

“You know what you should find enriching? Spending time in Eleanor’s chambers.” She saw her brother turn a flushed red of embarrassment that made the Princess want to roll her eyes. “To do… what your are implying… on a holy day is a sin against God.” Despite being a King, he acted as though he was a monk. Chloe knew of no other person who faithfully followed adhered to the sanctioned days of procreation the way Louis did.

“And that is why you’ve been married for five years and have zero heirs.” Some courtiers whispered about the failing of his wife, but there was not much she could do when her husband visited her once a week, when she was fortunate.

“This is not an appropriate subject for a lady.”

“Producing heirs? That is the most important role of a lady, and I intend to perform my duty well, which is why I need to go to Champagne!” If my husband is as devout as Louis is, she thought to herself, I am getting an annulment.

“Enough Chloe!” Louis snapped, unable to handle the impropriety of being criticized about his bedroom habits by his unmarried sister. Even though someone had to do it.

“Good morrow dear husband and sister,” a lively voice cut in, both heads turned to see Louis’ wife, Queen Eleanor, the Duchess of Aquitaine approaching with her own retinue of ladies-in-waiting. “It is nice to see you two spending time together before our dear sister Chloe departs for her wedding.”

Chloe sniffed, letting fake tears well up in her eyes. Louis loved pleasing his wife, in some ways, she intended to use her against him, “Well I hate to disappoint you sister, but we may as well cancel the wedding, since my brother wants to disgrace me by sending me in tatters!” She started bawling dramatically, and her ever attentive lady’s maid quickly dabbed at her eyes.

“Don’t cry my lady!” she fretted, almost as distraught as Chloe.

“We are not cancelling the betrothal!” King Louis said, real fear in his voice. He turned to one of his advisors, “Find my mother, tell her it’s happening again.” The advisor started hurrying down the hall to fetch the Dowager Queen.

“Did Father force Eleanor to be dressed in rags when you married her?” Chloe asked, her voice wavering as tears continued to well in her eyes.

Louis looked at his wife beseechingly, his wife took sympathy and stepped in to placate her sister-in-law. “Chloe you are aware this situation is different.” Chloe tried not to scowl at the traitor to women’s needs. Where was the solidarity?

She sniffed, “I am not! Why should Louis’ tiff with the Pope impact my travel to Champagne? It’s ridiculous! Utterly ridiculous!”

Eleanor’s brows furrowed in confusion, “Chloe, you are aware of the situation, are you not?” Of course she was! She had been hearing her brother complain about the Pope’s actions all week. It had made for a boring week at court.

Chloe waved her hand, “Yes, the Pope appointed a new Archbishop of Bourges, some Pierre or Jacques, you hated him, and shouted over a bunch of dusty objects-”

“Holy relics!” Louis corrected; it was so easy to rile him up.

“-That you would never enter Bourges if Pierre does. The Pope responded by banning you from taking Communion. But,” Chloe continued with feigned innocence, “that sounds solely like a you problem, does it not brother?”

Eleanor let out a small laugh, before catching her husband’s eyes and covering her mouth. Louis was anxiously thumbing at his rosary, probably praying for deliverance from his hot-tempered sister. His prayers appeared to be answered when an older voice came ringing out from the end of the hall, “Chloe! Why am I hearing about you threatening to break a proposal?”

Chloe scowled at her brother’s retreating figure. She had a chance of wearing down her brother Louis, he was better suited for silent prayer than handling his sister’s temper tantrums, but their mother? Adeliade of Maurienne had helped to rule France for over twenty years, she was a formidable force, and seething with rage as she walked towards her daughter. “My chambers, now.”

Chloe sighed; she should’ve sent Sabrine after that pompous advisor and had him shoved down a flight of stairs. Next time she would not make that mistakes.

***

Despite the dressing down her mother administered, the Princess still attempted a few more times to badger her brother into letting her visit Champagne. The Dowager Queen had any letters she attempted to write to her betrothed about the direness of the situation intercepted. Her mother was taking no chances, Chloe had ended betrothals in the past, though that was the fault of her parents and brother’s ridiculous matchmaking. She was a princess; she should be married to another prince or king. Chloe was not unreasonable, she was amenable to marrying a noble who possessed sizeable influence and land, but she still had standards! They had to be attractive, Chloe would not suffer through childbirth only to give birth to ugly babes. Intelligent, wealthy, fashionable, not too pious, she did not want to live as Eleanor did, having a monk for a husband. And of course: location, location, location. She would not live anywhere too cold, too muggy, if the cuisine was too disgusting, or if the language was too inferior or ugly. At one point her father had considered marrying her to some Hungarian duke or count, Chloe had put an end to that. Between the obnoxious accents and the insufferable amount of paprika, she would’ve thrown herself off the highest tower in her home if she had moved there. It was not her fault the diplomat, a grown man of five-and-thirty, left in tears. His employer should have picked a more fortified man for the job.

Her father had died before finding her a suitable husband. King Louis the Fighter was no match for his daughter’s will. He had made the task harder for himself after arranging the match between his ward, Eleanor to her older brother Louis. Her sister-in-law was the Duchess of Aquitaine in her own right, possessing one-third of France at the time of their marriage. Louis had received the best in Europe for his wife. A wife he was not even supposed to have. Their oldest brother Philip had died six years earlier in an utterly ridiculous and undignified manner, Chloe did not like to think about, making monk Louis the new Dauphin.

If Louis had married the best, then she would marry the best. Her brother had finally succeeded where their father had failed. He had arranged an acceptable betrothal between her and the heir to Toulouse. It was only a county, but the man in line to inherit more than made up for the lack of a crown.

Adrien was the most handsome man in France, likely Europe. Chloe decided he would be her husband when she laid eyes on the portrait of him that Count Gabriel, Adrien’s father, had sent. They had met a few times before, but it had been a few years since the now reclusive Count had ventured to Northern France with his son. The years had been excellent to Adrien. He had flowing blond hair the color of gold and dazzling green eyes. Chloe was determined to get a necklace fitted with emeralds to match them. His green bliaut was moderately fitted over his chest. He was reported to be a knight of excellent skill and strength, Chloe wished his tunic had been tighter. She wanted to see the effect all the years of knight training had had on his glorious physique.

A young, attractive, wealthy knight for a husband? Every lady at court, with their husbands twice their age, that had whispered about her being unmarriable would soon explode into fits of rage. In a few years they would be lining up, fighting to marry their children to the little Adonis’ and Aphrodites’ a union between her and Adrien would surely create. Chloe could hardly wait.

Her beloved had started exchanging letters after their engagement. He was a poet, well-educated, and adored her. Chloe had finally been matched with a man who was her equal on every level. Marrying the perfect man meant having the perfect wedding, which meant getting to buy new perfect clothes at the best fairs, which were in Champagne.

The Queen Mother had not appreciated this sound logic, “I am at a loss for words Chloe!” She snapped! Despite being at a loss for words, she lectured me for half an hour, Chloe had thought to herself.

“Unless your trip to Champagne fixes the damage your brother has done to please his wife, you will not go!” Her mother had finished the lecture, then sent her to her chambers to finish packing. Louis grew a backbone, spurred on by their mother’s support, and continued to refuse her, the times when Chloe could corner him. Louis spent so much time in the chapel, he may as well have his bed moved there.

“Chloe!” Louis snapped a day before she was set to leave, the monk had finally reached his breaking point with his obstinate sister. “I am your King, you do not order me around! You will travel to straight to Toulouse and marry Adrien with a smile on your face. You will not whine. You will not throw a tantrum. And you will. Not. Go. To. Champagne! THAT! IS! FINAL! Do you understand?”

Chloe pursued her lips, finally acquiescing, “Yes Louis…”

“…For the last time Ser Bruel, the King has ordered for me to go to Champagne to outfit my wardrobe for my wedding. We detour to Champagne then bring me to Toulouse, do you understand?”

“His Majesty ordered you were to be brought straight to Toulouse Your Highness.” The leader of her escort replied firmly, he was riding along Chloe’s carriage on a chestnut mare in full armor. Chloe had waited till her entourage had left Paris before informing him of the new travel itinerary.

Her lady’s maid Sabine leaned forward, bristling with fake indignity, “Ser Bruel! He only said that because of the tumultuous situation in Champagne! Count Theobald is still angry about the King allowing his sister Eleanor to be repudiated. We have to maintain a low-profile because of the bad blood between the two of them. It twas a ruse Ser Bruel!”

Chloe watched the furry caterpillars Ser Bruel called eyebrows draw so close together they almost touched. His mind has probably never had to work so hard, she thought with disdain. “Her Majesty does not have a brother.” He finally said.

Both Sabine and Chloe groaned, they planned for Ser Bruel’s dimwittedness to help aid them in their subterfuge, not stall it. “Not Eleanor of Aquitaine! Eleanor of Champagne you twit! Does Sabine need to draw you a family tree?” She snapped angrily, earning a sharp look from her guard. As though he didn’t deserve it!

“The King is ending his marriage with the Queen to marry Eleanor of Champagne? But she’s married to the Count of Vermandois.” Chloe thumped her head against the wall of her carriage, the names of the nobility were wasting storage space in the man’s mind.

Sabine procured her portable writing table and started sketching a visual aid for the knight. “Ser Bruel it’s simple. The King is married to Eleanor of Aquitaine, recently he allowed Her Majesty’s sister, Petronilla, to marry his cousin Count Raoul of Vermandois.”

“Count Vermandois already has a wife.” Ser Bruel interjected while Chloe tried not to scream.

Sabine nodded patiently, “King Louis allowed Count Vermandois to put aside his first wife, Eleanor, who is the sister of Count Theobald of Champagne.” Ser Bruel nodded, though Chloe was not confident the oaf truly understood. Sabine continued, “Now His Majesty is fighting with the Pope and Count Theobald, he gave permission to her Highness Chloe to attend the fairs in Champagne, but discreetly, no one should know we were there.”

“I’m sorry milady, I can only follow direct orders from the King.”

Sabine shoved a folded piece of parchment out the carriage window towards Ser Bruel. “Will a written note suffice?” She asked curtly, Chloe had trained her well.

The knight inspected the royal wax seal, read the letter, slowly, eventually folding it, and handing it back to Sabine. “Very well,” he said, “we are headed for Champagne. Princess?”

“Yes?” Chloe replied sweetly.

“This will be a quick detour.” He stated firmly.

“Obviously Ser Bruel.” Chloe closed the curtains to her carriage window, tired of dealing with slow-witted knights. She gave a conspiratorial smile to Sabine. The lady’s maid had been lacking when she first joined Chloe’s court but had quickly risen to the high standards the Princess had laid out. A devoted, hard-working servant, who was exceptionally talented at penmanship…

Chloe opened the locket which contained a miniature portrait of her beloved Adrien, gazing lovingly at her future husband. In only a few weeks Adrienkins, you will be mine.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

This prompt was suggested over a year ago and I've been super busy and felt bad about taking so long to get to it. Now I'm finally working on it! But listen, look at me, I'm in school, I've got a test about gas exchange in two weeks. I may not be able to update consistently, but come hell or high water this fic will be finished. Have patience dear readers. xoxo

~~~~

I didn't want to do any world building so I decided to choose a time period based on a historical figure and set the story there so I could research any world building. Two documentaries later and I'm trying to pigeon-hole every reference to Eleanor of Aquitaine possible. I can't tell you how fun it is trying to weave real world historical events into this story.

~~~~

Historical Reference:

- Louis was not the oldest son and so was trained for a church career, as a result he was incredibly devout.

- Eleanor really owned Aquitaine in her own right after her father died

- Yes the Catholic Church used to have restrictions on what days it was okay to have sex!

- "at war" might be inaccurate but Louis did fight with the Pope

- Yes Louis really did allow a Count to divorce his wife to marry Eleanor's little sister. Eleanor encouraged this and it did not go over well! @Petronilla, go girlboss!

- the county of Champagne had fairs where goods were sold that made it a commericial hub in europe!

- Adrien is not the count of toulouse, but Louis' real life sister did marry the count of toulouse!

#miraculous lb#miraculous ladybug#ml fanfic#ao3#ao3 writer#chloe bourgeois x kagami#chloe bourgeois#kagami tsurugi#historical au#historical fiction#eleanor of aquitaine#12th century france#lesbian romance#enemies to lovers#knight in shining armor#mine#Miraculous Lady Knight#writers on tumblr#adrien agreste

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Struck with a thought in the shower. What if Yoichi was transmigrated into Louis XVI, well-known for his love of lock-making and machines?

Yoichi looked at his…friend? Could he consider Claude-Renee his friend? The man helped him dress this morning, entirely unprompted in a way that suggested he helped Louis XVI dress every morning. Surely if a man had helped another man dress, those two men were friends. That was the bro code! If Claude-Renee ever needed it, Yoichi would help Claude-Renee dress, if the other man wanted him to help and would not feel embarrassed at wearing his stockings inside-out.

Yoichi looked at his friend and decided to do his duty as king and future hero to the French people even though he longed to go back to bed and hide under the covers. “What’s lined up for today?”

“You have an appointment with Dr. Guillotin and Dr. Louis after breakfast to discuss issues with that English decapitation machine,” Claude-Renee promptly said.

Yoichi paused. What? “What?” He asked.

“Yes, after you gave your support for the creation of a more humane and equal form of execution, they found that the blade didn’t consistently behead. They were hoping you, with your knowledge of mechanisms, would offer some advice,” was the matter of fact explanation given.

Yoichi glanced into the mirror, hoping that he didn’t look as horrified as he felt. Poor old Louis Capet looked possibly even more horrified than he felt. Fair enough; he had a good face for looking horrified. Yoichi gulped. “Any…other matters?” He asked, sweating bullets.

“Ah, well, Marquis de Laborde wanted your thoughts on the creation of a pick-proof lock for his home bank vault. Something about-“

Claude-Renee continued to speak. Yoichi didn’t hear anything over the sound of his own internal screams.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

LUIS CAPETO

Retumban tambores en torno al cadalso

que se alza velado, cual túmulo negro;

en el centro el tajo con la abierta báscula,

esperando el cuerpo. Luce la hoja blanca.

Por tejados llenos vuelan rojas flámulas,

voceros pregonan precio del balcón.

Siendo enero, el pueblo de calor se abrasa,

gruñendo a empellones. Lo hacen esperar.

Se escucha alboroto. Crece. Gritan, braman.

Llega en la carreta, Capeto, enlodado,

vejado con heces, desgreñado el pelo.

Aprisa lo arrastran en alto. Lo tienden.

Le ciñen el cepo. La cuchilla silba.

Mana sangre el cuello, preso en el boquete.

*

LOUIS CAPET

Die Trommeln schallen am Schafott im Kreis,

Das wie ein Sarg steht, schwarz mit Tuch verschlagen.

Darauf steht der Block. Dabei der offene Schragen

Für seinen Leib. Das Fallbeil glitzert weiß.

Von vollen Dächern flattern rot Standarten.

Die Rufer schrein der Fensterplätze Preis.

Im Winter ist es. Doch dem Volk wird heiß,

Es drängt sich murrend vor. Man läßt es warten.

Da hört man Lärm. Er steigt. Das Schreien braust.

Auf seinem Karren kommt Capet, bedreckt,

Mit Kot beworfen, und das Haar zerzaust.

Man schleift ihn schnell herauf. Er wird gestreckt.

Der Kopf liegt auf dem Block. Das Fallbeil saust.

Blut speit sein Hals, der fest im Loche steckt.

Georg Heym

di-versión©ochoislas

#Georg Heym#literatura alemana#poesía expresionista#revolución#guillotina#ejecución#Capeto#rey#di-versiones©ochoislas

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paris Solo Day and Wrap Up

As the final hours of our class in Paris begin to wind down, it was time to put a bow on the three week experience. Despite my continued solo adventures across Paris, even across France on one occasion, it was time for this seemingly natural action to be required. However, this excursion would be out of my hands, as I would be presented a destination that I would need to go to.

For me, this was the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers and its corresponding musée. After departing from Saint-Sulpice in the 6e, I began my stroll down Rue Bonaparte and towards the Seine. My ticket appointment was not until noon, so I took advantage of the almost two hours I had in the bank to enjoy a walk along the river and go against the gradient of the snail through the 5e, 4e, and eventually the 3e arrondissements. Along my walk, I decided to go up further and go across L'Île Saint-Louis in order to get into my district for the day. Needing to find a bathroom and stop for lunch, I made my way down the Rue de Rivoli for a mid-day break. After enjoying some fish and chips at a café, it was time to venture north and find my destination.

Upon arriving, I was quite excited by the antiquarian design of the building, which had been a priory until the revolution. The historic nature of the founding and site, as well as the dedicated works on display, were right up my alley. I made my way in and started to go through the collections, which featured a physical timeline of innovations in measurement, transportation, communication, energy, mechanics, materials, and construction. I think my favorite section would have had to have been the first one on scientific measurements. I think one of the more fascinating byproducts of the French Revolution was the way in which the metric system was developed. I also find the way in which official, but sometimes arbitrary measurements perpetuated inequality and poverty is such a fascinating principle that is often overlooked.

Another wonderful use of the space was how the old church was turned into a temple to science. With planes hanging from the ceiling, cars on display on multiple levels, and a Foucoult pendulum at the center, the best place to view everything was by climbing a ramp that led you to the top of the room, on level with the peaks of the stain-glass windows. It was an unreal sight, and you could appreciate the beauty of the art and architecture of the church from a whole new perspective.

Afterwards, I sat in the small garden on the ground to just take in the surroundings, as well as catch up on postcard writing, before setting off for another sight that had piqued my interest. On my walk to the CNAM, I had passed the Archives National and decided to go if I had time. In an old mansion with a grand courtyard, the museum itself was small and one of its two exhibitions (Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette) was closed, but I still went in and was immediately greeted with the constitution of the 5th Republic. The opening room had various sections on the history of record-keeping with examples that I was perusing when an employee offered to take us through the apartments upstairs. Whether this was a part of the museum that happens regularly or something unusual I did not know, but I went up with the other museum patrons. Here were more stunning documents within French history including: decrees from Charlemagne and Hugh Capet, the last letters of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, a sketch of Joan of Arc from the Parliament de Paris, the Edict of Nantes, the Tennis Court Oath, and a journal from Louis XIV. One document that they had that was not on display though was the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, which I was hoping would be shown when I had first passed the building earlier in the day.

It was then time to make my way to the Weeping Willow at the very tip of L'Île de la Cité. So, I embarked towards the river and headed along the right bank until I reached Pont Neuf where I crossed and descended at the Henri IV statue and met the class. We had a nice picnic and everyone shared their solo day and it was a nice wrap up for our penultimate meeting as a group.

For our last full day in Paris, I got an early start and metroed to L'Arc de Triomphe for a walk down the Champs-Élysées and towards the Concorde. Now that the Bastille Day setups were taken down, I could finally take in all of the place and fully see the Luxor Obelisk (although constructed had the walk up to it closed). I then went to the steps of the National Assembly, by the Élysées Palace and through the Tuileries before taking a train back to Luxembourg. It was nice to take in the iconic sights of Paris one last time.

For our final class meeting, we met at an Amorino in the shades of the Pantheon to get gelato to eat in the gardens, even though everyone was done eating before the walk was over. Here, it was time to wrap up A Moveable Feast as well as out time in Paris. It was a nice discussion but I was just relishing the last moment of community between the 11 strangers that I had come to befriend over the month of July. I was quite wary about this aspect coming into the trip, as was bracing for the worst, but I actually made some great friends and am thankful for everyone who made my first time in Paris so special.

After returning to Maison des Mines to pack and nap, a few of us set out for one last night in Paris. We started with a French three course meal on a side street off of Rue Saint Jacques. I started with the escargot, obviously, and tried rabbit for the first time. I then finished off with a nice crème brulée. My favorite part about French food was definitely all of the new meats that I got to try and I liked every single one of them. It is also quite fun to eat snails and tell everyone back home that they are delicious. To finish our stay, we went to the giant roue in the Tuileries for an amazing view of Paris. Thanks to a bathroom break and the opportunity to watch the ducks of Paris, we showed up at the perfect time, as we got to take in an amazing sunset, see the flashing lights of the Eiffel Tower, and enjoy one final, beautiful night. As we disembarked, it began to sprinkle, but it was the perfect amount of rain that makes you enjoy the world and brings the most wonderful smell to your nose. After taking in the Louvre lit up, we walked back along the Seine to the Petit Pont and took Rue Saint Jacques to the building that had become home.

Waking up this morning, it was a stark find to see the opposite half of my room barren, hammering the reality that my time in this city was at its present conclusion. After a shower and final packing, I set out to a nearby café, broke my fast, and took in my neighborhood for one final time. I then walked to the Luxembourg Gardens for another stroll within the beautiful grounds before retrieving my bags and heading to the RER station.

Now, I sit at Charles de Gaulle after going through security and passport control, awaiting my return to the United States. These three weeks have been the absolute best time of my life and I feel that I have grown up so much and in ways that I will not even know for some time. Going abroad on my own, learning a city in a day, planning my own trip, and just exploring a world so different from my own have been so rewarding in so many ways that I will always hold onto. I hope to be back in Paris soon, but I do not know if any time here will ever be like my first. The length of my stay has allowed me to do so much and feel like I truly know Paris; I do not feel like a small blimp in the chaotic comings and goings of the city. The memories that I made here will always be special to me and I hope to draw on them frequently as I continue to move through my own journey of life.

Until next time,

À Bientot, Paris. Je t'aime.

0 notes

Photo

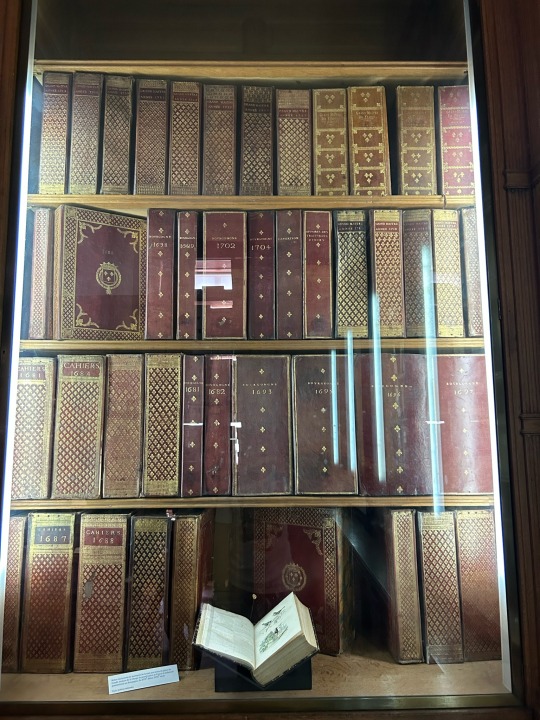

Favorite History Books || The Capetians: Kings of France 987-1328 by Jim Bradbury ★★★★☆

It was luck as well as judgement that the Capetians produced such a long line of competent kings. It required a certain amount of effort; each king had to marry, choose a suitable wife, and produce an effective heir. One or two Capetians left their marriages a little late but all succeeded in this modest effort. In the Middle Ages producing enough children to ensure an heir was a chancy business; many families failed in a very short space of time. Stillborn children, infant deaths, early deaths, fatal illness, fatal accidents, death in war - the possibilities were many, and survival into mature years by no means certain. Some Capetian kings did not live to have long reigns, but in general their survival rate was good and minorities were rare. The Capetians did their best to protect their heirs but they were also fortunate. The quality of a man that would make a competent king was another matter. Kings could do little about this beyond choosing a capable wife. Again the Capetians were remarkably fortunate. Compared to other dynasties the mental ability, common sense and general competence of the dynasty was evenly spread. There was no King John, Henry III, Edward II, Henry VI or Charles VI. One must recognize through the earlier period the importance attached to succession by the oldest son. The importance of this can be seen by comparing the Merovingian, Carolingian, and imperial practice.

In France, kings made a great point of organizing the succession for the oldest son, known as association, and it worked. It was invariable practice by all the Capetians from Hugues Capet, who associated Robert the Pious in the very year that he himself became king. The deed of association meant that the son was made king before his father died, thus validating the future succession. By the time of Philippe Auguste it had become so accepted, and the dynasty so well established, that association was no longer necessary.

The endurance of the dynasty was important. Comparison with the Holy Roman Empire makes the point. In the German case families failed to retain the crown and impose sons. The result was “election” of the new emperor, in practice a move to the strongest candidate from any of the principalities, or just as often the weakest candidate as the only one all the others would accept. The result was a series of disputed successions, lack of continuity and of stability. The relative growth of France as a power and the decline of the Holy Roman Empire through the Middle Ages owed much to the practice of succession. The family loyalty of the Capetian dynasty was another important factor. Rebellions by one member of the family against another were not unknown but they were rare. The comparison with other dynasties is telling, as the almost constant problems in this respect of the Merovingians and the Carolingians, of the civil wars in Germany or England. The granting of apanages helped this process, but there was also a strong family tradition, and nearly all younger brothers and close relatives were loyal and assisted the king of the day. As a result the reputation of the dynasty for good government stood high. Good and competent rulers were the mainstay of the dynasty - men such as Hugues Capet, Robert the Pious, or Louis VI. Philippe Auguste and Philippe IV were outstanding rulers in their own ways, while St Louis became an icon of medieval kingship throughout Christendom.

On 1 February 1328 the last Capetian monarch, Charles IV, died. The only survivors of the dynasty were female. His widow was pregnant and there was a period of uncertain waiting. On 1 April (appropriately?) she gave birth to a daughter. Recent development had excluded female succession, and it was ignored in 1328 - though some compensation was made to the surviving women of the family. The opinion of the nobles of France counted most, and they preferred Philippe de Valois as king. He became Philippe VI (1328-50) and initiated another long line of kings to 1589. They belonged to the same family as the Capetians but direct succession from father to son or brother had been broken. Philippe was the son of Philippe IV’s brother, Charles de Valois, and grandson of the Capetian Philippe III. Philippe VI was crowned at Reims on 29 May 1328.

One legacy of the dynasty was this stress upon excluding female succession, practice rather than law. The so-called Salic Law was suddenly discovered resting in the library of St-Denis in the 1350s. The uncertainty resulted in some dispute over the succession. Female members were compensated. Jehanne received the kingdom of Navarre; her son, by Philippe d’Évreux, was Charles “the Bad” of Navarre. Others received considerable cash payments. The female who created the most serious problem was Isabelle, daughter of Philippe IV, wife of Edward II of England and mother of Edward III - who in time made a claim to the French throne. It is true that this was only in response to Philippe VI claiming the confiscation of Gascony, but its consequences were great - though as an excuse rather than a reason perhaps. It initiated the Hundred Years’ War with all its horrors and instability for France. But it seems more a result of the rule of the Valois than a consequence of Capetian failure.

The Valois dynasty makes a contrast to the Capetian. Their defeats were more fundamental, notably in the war with England - at Crecy, Poitiers and Agincourt. No Capetian king had suffered such disastrous losses - King Jehan II was taken prisoner at Poitiers in 1356 and incarcerated in London. A notable point about the Capetians was continuity. One after the other the Capetians were able, competent men. They may not have been great intellectuals but they were mostly pious, hard working, and generally respected. The Valois kings were less fortunate. The unfortunate consequences of the accession of the mentally unstable Charles VI can hardly be exaggerated.

Not all matters Capetian continued to dominate. Perhaps deliberately, the Valois set some new values and changed certain aspects of rule. The Capetians had supported and raised the abbey of St-Denis as the royal abbey, and St Denis as the patron saint of France. The Valois did not exactly attack or destroy this, but they made a change. They placed more emphasis on St Michael, who became the patron saint for their dynasty, and then for France. They also replaced the oriflamme as the royal standard by the banner of St Michael. The same kind of comment could be made for all the troubles in later medieval France. They were hardly consequences of Capetian rule. Perhaps the greatest problems came from natural disasters. The late Capetian period had seen the beginnings of this trouble with bad weather followed by poor harvests, and plague. These problems increased under the Valois, particularly with the Black Death and its dreadful social and economic results - decline in population and social upheaval. Capetian times began to look like a golden age in French history.

#historyedit#litedit#house of capet#medieval#french history#european history#history#history books#nanshe's graphics

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo