#jean de wavrin

Text

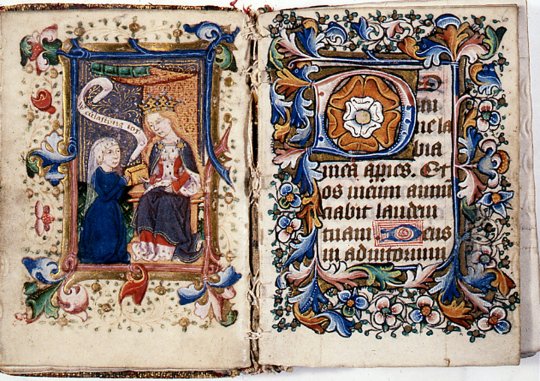

guy sitting by a fire

in a manuscript of jean de wavrin's "anciennes chroniques d'angleterre", flanders, c. 1470-90

source: Paris, BnF, Français 75, fol. 198r

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

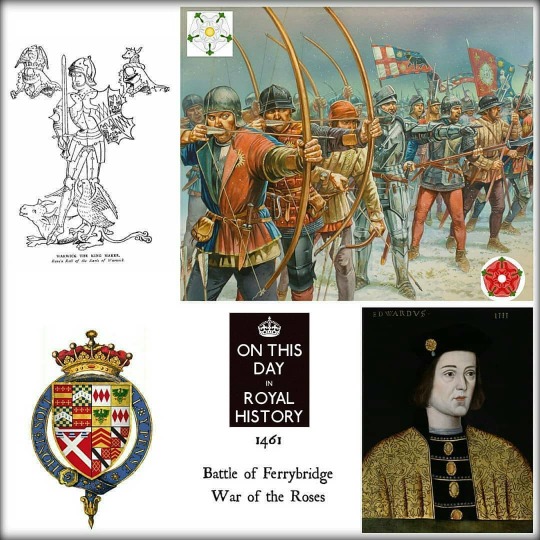

The Battle of Aljubarrota 1385

Detail from the Illuminated manuscript "Anciennes chroniques d'Angleterre" by Jean de Wavrin

#medieval#art#history#europe#european#spain#portugal#england#france#hundred years war#middle ages#knights#archers#infantry#manuscript#castilian#portuguese#english#french#castile#battle of aljubarrota#battle#bruges#miniature#jean de wavrin#illuminated manuscript#vanguard#king#armour

145 notes

·

View notes

Note

Don't Edward IV of England and Elizabeth Woodville have any contemporary portraits left?

Hi! Portraits - no, but there are contemporary stained glass and imagines in the manuscripts.

Anthony Woodville presents a book to Edward IV, Elizabeth Woodville and Prince Edward. Lambeth Palace MS 265 (1477)

Elizabeth Woodville in her coronation robes (Worshipful Company of Skinners’ Fraternity Book)

Liverpool Cathedral MS Radcliffe 6, Hours of the Guardian Angel. Joan Luyt presents the book to Elizabeth Woodville.

Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville in the Royal Window, Canterbury Cathedral (commissioned by Edward in 1480)

Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville - The Luton Guild Book. Frontspiece, circa 1475.

Edward IV at his court receiving Jean de Wavrin's book (from Les Anchiennes et Nouvelles Chroniques d'Angleterre c.1470-80)

The coronation of Edward IV (from Les Anchiennes et Nouvelles Chroniques d'Angleterre c.1470-80)

#edward iv#elizabeth woodville#15th century#history#illuminated manuscript#stained glass#wars of the roses#kings and queens

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Speaking of Elizabeth Woodville's appearance, I was always confused with which descriptions of her were contemporary and which weren't. I know none of her portraits are contemporary, and Thomas More was only a child when she was queen (although he might have seen her after that, so ultimately I guess that his description was probably based on how she looked in her 40s and 50s, meaning she was very clearly still attractive at that point) and published his work years later. But I can't find anything on her other descriptions, namely "most beautiful woman in the isle of britain" and "heavily lidded eyes like that of a dragon", so I wondered if you knew who said them and when? And if we had any other descriptors of her?

I'm interested because beauty was often extremely exaggerated and embellished when it came to nobility and royals, but Elizabeth Woodville seems to have been genuinely considered very attractive (so was Edward for that matter lol), and it's clearly proven by Edward desiring/falling in love with her. So I wondered if there was anything specific we knew about her appearance from contemporary sources.

Hi! I would have to look deeper into this, but the comments about Elizabeth’s appearance that I can find at the moment are few. Jean de Wavrin, Burgundian chronicler who may have met Elizabeth (he describes the account of an embassy from France as if he was there at the scene, for example), called Elizabeth ‘la plus belle fille d'Engleterre’ (the most beautiful woman in England) and claimed that the king had chosen her for ‘sa très grande beauté’ (her very great beauty). An anonymous contemporary chronicler (Hearse’s fragment) who claimed to be Edward’s servant, said that the king ‘could not perceive none of such constant womanhood, wisdom and beauty, as was Dame Elizabeth’. Mancini, who may have seen her at court before Edward died, said the queen possesed ‘beauty of person and charm of manner’. I can’t find anything about the ‘heavily lidded eyes’ description, but I would bet it’s not contemporary as late medieval accounts did not dwell on the specifics that made a woman beautiful. The earliest reference we have of Elizabeth Woodville’s ‘fayre here’ (fair hair) is in Edward Hall's mid-16th-century chronicle when the author described Elizabeth mourning her sons (he might have seen a portrait of the queen, who knows, but he also may have relied on the stereotypical image of a queen etc). I’m afraid we don’t have anything too specific about Elizabeth Woodville coming from people who might have actually seen her in person.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coronation of Richard II aged ten in 1377, from the Recueil des croniques of Jean de Wavrin. British Library, London.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miniature de Jean Wavrin de 1480 du duel entre Jacques Le Gris et Jean de Carrouges.

0 notes

Photo

Round dance at the court of King Diodicias of Syria during the engagement party of his 33 daughters. Miniature from the Chroniques d'Angleterre written by Jean se Wavrin, c. 1470. Paris

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

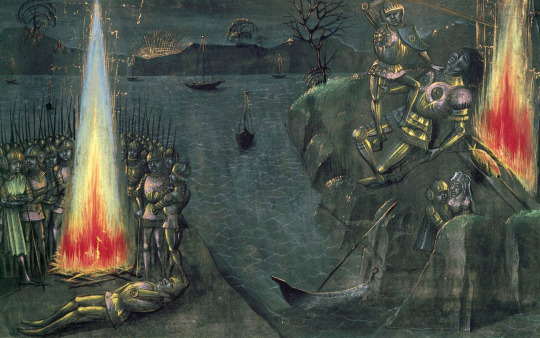

The trusty governor Vlad Dragul and his three sons, Mircea, Vlad and Radu.

The name of Vlad is first mentioned in his father's letter of 20 January 6940 (that is, in modern parlance 1432, the document was later corrected to 1437, given the dates of other documents.

"... and not in the days of our dominion, nor in the days of my sons, the first-born Mircea and Vlad", 20 January 1432, Targoviste.

Later the governor mentioned his two sons more than once (2 August, 10 August and 23 August 1437). And a little later, in 1439, August 2, the letter will consistently mention Mircea, Vlad and Radu, indicating that Radu appeared only in 1438-39. The historian Professor Andreescu mentions that Vlad was always second in the sequence.

Duca, a 15th-century Greek historian, writes in his work that in the spring of 1442 the voivode Dragul was summoned to the court, suspecting him of conspiring with other Christians. By deceit he was forced to come (see the chronicle of Jean de Vavrin),

"In order to impress the governor with the magnanimity of a high ranking Turk, his ambassador brought with him splendid gifts and offerings as a sign of welcome, informing him who his lord was and that he saw it imperative to further his friendship and collaboration with the governor of Wallachia. And in order to achieve this, the high-ranking Turk begged the governor of Wallachia as insistently as he could to come to him in Adrianople, and in order that the governor could stay in his country in complete safety, the Subashi gave the governor a corresponding guarantee from the high-ranking Turk".

(Jean de Wavrin, Anciennes Chroniques d'Angleterre, chapter "How a High-Ranking Turk called the Ruler of Wallachia to talk to him and sneakily deposed him").

So, the Turks captured him and threw him in prison at Gallipoli.

Deceit was in the Turks' esteem, for they knew no honor and held not their word:

"But if they swear on books of soap, as it is written above, they do not perform this oath, nor any other oaths when they can; they make the innocent guilty, so that they may always carry out their malice."

"But if the Sultan makes peace or truce with anyone, he always plots its violation, and when he makes peace with one, then he wrestles with another, but he always blames his subjects, and therefore they are wicked, as if they were spinning in a wheel, so that always the Christians are oppressed, as we shall describe below, and those who ate the broth with them must pay them with meat," from the Janissary's notes, chapter "O TURKISH JUSTICE AND THEIR DEFAULTY AND Cunning".

The 15th century Turkish military historian Asık Pasha-zade (Asık Pasha-oğlu) recorded that the janitor arrived not alone but in company of his two sons who were also captured and locked up in the Eğrigöz fortress (see also Neşri's chronicle). The two sons mentioned by the 15th century historians were Vlad and the little Radu:, because the firstborn, Mircea, remained in Walachia.

Thus, the Serbian chronicles of the 15th century note that "in 1442 the Turks captured Vlad's governor, and left his son Mircea in Walachia in his place". But, as we considered earlier, most likely by the summer Hunyadi, still the voivode of Transylvania, went with an army to Walachia and drove young Mircea (14-15 years old) from the throne, bringing with him his pretender of the Daneshti family at that time, Basarab, who would already be busy signing the letters in Kurtia de Ardzesh on January 9, 1443. Duca notes that the governor Vlad regained power already in 1443, and his "young", as the historian stresses, his children will remain in captivity with the Turks. Elder son Mircea will be reunited with his father and already in 1444-45 take an active part in the Crusade:

"My father called me to him and asked for the following. My father told me, if I on behalf of him will not pay vengeance subashi from the fortress Djurdzhu, he will deny me, and I will no longer be worthy to be called his son. The reason for this is the treachery of the subashi. He brought his father to a high-ranking Turk, promising him escort

and safety, but instead he was imprisoned at Gallipoli, where he kept him prisoner in iron fetters for a long time. Now that Subashi and his Saracens are before us, surrendering to their father in return for their lives and property being spared and brought safely to Bulgaria. But I will cross the river, two leagues from here, taking two thousand Vlachs with me, and I will set a trap for them, so that the Saracens will think that they go to Nicopolis, but I will be on their way, and their death will be there", the words of Mircea, recorded from a dialogue with him by Mr. Wavrin, from the chronicle of Jean de Wavrin, chronicler of the crusade of 1444-45, Jean de Wavrin, Anciennes Chroniques d'Angleterre).

It was then that Mircea would avenge his family and the culprit who had forced his father to come to the Turks by lying was executed.

In 1445 all three sons also appear in the charter, in the same order.

#Google Translated#Vlad Tepes#history#wallachia#romania#vlad dracula tepes#article#Vlad Dracul#Mircea#Vlad#Radu

35 notes

·

View notes

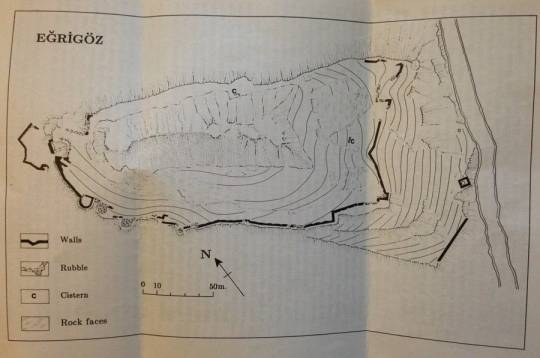

Photo

On This Day In Royal History

.

In association with English Heritage

.

28 March 1461

.

The Battle of Ferrybridge - war of the roses

.

.

◼ The Battle of Ferrybridge, 28 March 1461, was a preliminary engagement between the houses of York & Lancaster before the larger battle of Towton, during the period known as the Wars of the Roses.

.

◼ After proclaiming himself king, Edward IV gathered together a large force & marched north towards the Lancastrian position behind the Aire River in Yorkshire.

.

▪️ On 27 March the Earl of Warwick (leading the vanguard) forced a crossing at Ferrybridge, bridging the gaps (the Lancastrians having previously destroyed it) with planks. In the process he lost many men, both to the freezing winter water & to the frequent hail of arrows coming from a small but determined Lancastrian force on the other side. Once the crossing was managed & the Lancastrians seen off, Warwick had his men repair the bridge while camp was established on the north side of the river.

.

◼ Early next morning the Yorkists were ambushed by a large party of Lancastrians under Lord Clifford & John, Lord Neville (Warwick’s cousin). Completely surprised & confused Warwick’s forces suffered many losses. Warwick’s second-in-command at camp, Lord FitzWalter was mortally wounded while trying to rally his men (he died a week later). The Bastard of Salisbury, Warwick’s half-brother was slain & in the process of retreating the Earl of Warwick himself was injured, struck by an arrow in the leg. Jean de Wavrin states that nearly 3000 men perished in the fighting.

.

◼ After the battle Edward arrived with his main army & together Warwick & Edward returned to the bridge to find it in ruins. Warwick sent his uncle, Lord Fauconberg with the Yorkist cavalry upstream to where they crossed the ford at Castleford & pursued Lord Clifford. Fauconberg pursued Lord Clifford, in sight of the main Lancastrian army & defeated him after a fierce struggle. Clifford was killed by an arrow in the throat, having unaccountably removed the piece of armour that should have protected this area of his body.

.

.

. (at Ferrybridge)

https://www.instagram.com/p/B-SRCoFj5_L/?igshid=kohojmmhwpzf

#On this day#On This Day In History#History#Wars of the Roses#House of Lancaster#House of york#Plantagenet#Plantagenets#England#Edward iv#Henry vi#Medieval#British Monarchy

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Art of the Day: Leaf from Chronicles of England, Volume IV: French and English representatives meet at Leulighem, the "Peace of Duke Philip"

This manuscript is volume IV in a set of five from the collection "Recueil des chroniques et anchiennes istories de la Grant Bretaigne," written by Phillip the Good's counselor and chamberlain Jean de Wavrin. It chronicles the history of England from the early years of the reign of Richard II in 1377 to the demise of Henry IV, his successor, between 1400 and 1413. This volume, produced in Flanders between 1470 and 1480, was part of a set of which volumes II, III and V were recorded in the inventory of the library of William III of Orange in 1686, and was later rebound during the seventeenth or eighteenth century. Six three-quarter-page miniatures open the text of each book and depict events documented therein (with the exception of that of Book 1, portraying Richard II's coronation, which occurs prior to the period detailed in that book). The manuscript's margins are wide and relatively pristine throughout the textblock, but show significant signs of use on illuminated folios, indicating that this manuscript was primarily used for display and not as a historical text. Although few volumes of the Chroniques remain, this manuscript is particularly rare in that it is one of the two surviving exemplars of the text of volume IV, the other being part of the complete set in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BN fr. 74-85). Volumes II, III, and V of the set to which this volume originally belonged are now in the collection of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek (Den Haag, KB : 133 A 7). Learn more about this object in our art site: http://bit.ly/2vUgFLC

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

reflection of a horse on a fallen knight's armor

detail of a miniature from the "anciennes chroniques d'angleterre" (vol. 1) by jean de wavrin, flanders, c. 1470-90

source: Paris, BnF, Français 74, fol. 161v

#if you look closely you can see the reflection of the nearby trees on the mounted guy's armor :)#15th century#anciennes chroniques d'angleterre#jean de wavrin#battlefields#armor#horses#mirrors#medieval art#illuminated manuscript

317 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Detail of a miniature of Arthur slaying the Spanish giant on the island of Mont-Saint-Michel (1471-1483), by Jean de Wavrin. Royal 15 E IV f. 156. Courtesy the Trustees of the British Library

0 notes

Photo

«Those chronicles that give a date for Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville’s marriage each specify the same one: 1 May. This date is compatible with the known movements of Edward, who was at Stony Stratford the night of 30 April 1464 and could have made an excursion to and from Grafton that morning, as claimed by Fabyan in the sixteenth century:

«[I]n most secret manner, upon the first day of May, King Edward spoused Elizabeth […] which spousals were solemnised early in the morning at a town called Grafton, near Stony Stratford; at which marriage were no persons present but the spouse, the spousess, the Duchess of Bedford her mother, the priest, two gentlewomen, and a young man to help the priest sing. After which spousals ended, he went to bed, and so tarried there three or four hours, and after departed and rode again to Stony Stratford, and came as though he had been hunting, and there went to bed again. And within a day or two after, he sent to Grafton to the Lord Rivers, father unto his wife, showing to him he would come and lodge with him a certain season, where he was received with all honour, and so tarried there by the space of four days. In which season, she nightly to his bed was brought, in so secret manner, that almost none but her mother was of counsel.»

Several historians, however, have questioned the May Day date. As David Baldwin notes, ‘The idea of a young, handsome king marrying for love on Mayday may have been borrowed from romantic tradition’. J.L. Laynesmith agreed that ‘1 May is a suspiciously apt day for a young king to marry for love. May had long been the month associated with love, possibly originating in pre-Christian celebrations of fertility and certainly celebrated in the poetry of the troubadours’.

Whether the couple were married on May Day or later, the scant record does bear out Hall’s claim that a priest was present at the wedding. A Master John Eborall, whose church of Paulspury was close to Grafton and Stony Stratford, is said to have offered in 1471 to intercede in a land dispute involving the queen ‘supposing that he might have done good in the matter, forasmuch as he was then in favour because he married King Edward and Queen Elizabeth together’. A chronicle known as Hearne’s Fragment adds that the priest who married the couple was buried at the high altar of the Minories in London, but leaves a blank space for the man’s name.”

- «The Woodvilles: The Wars of the Roses and England's Most Infamous Family» by Susan Higginbotham.

Pictured: The marriage of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. Illuminated miniature from Vol 6 of the Anciennes chroniques d'Angleterre by Jean de Wavrin, 15th century.

#historyedit#edward iv#elizabeth woodville#history#15th century#the wars of the roses#wars of the roses#medieval#the middle ages#kings and queens#on this day in history#my edit

106 notes

·

View notes

Note

I read somewhere that you said Elizabeth Woodville was disliked and one of the reason is because she was a widow but didn't historically women marry despite being windowed women and windowed women did remarry in royalty like Mathilda, elenoar of acquitine, etc. Also wasn't Anne Neville herself windowed? Their virginity wasn't brought up. I thought she was mainly disliked because she was a commoner and had secret marriage with Edward iv. P. S Sorry if this is a stupid question 😖

Hi, anon! This is not a stupid question at all, it’s a topic that still remains so debated. I think you're referring to this ask + discussion? I was mainly citing Joanna Laynesmith's argument about how Elizabeth's status as a widow (and non-virgin) counted as one of the factors against her, but it wasn't the only factor—for example, the fact that Edward IV married without the consent of his lords was also brought up in contemporary reports. Anne Neville's case doesn't apply here because her husband married her before he became king himself, but there were indeed other women before Elizabeth Woodville who had been previously married and that later became queens of England: Eleanor of Aquitaine and Joanna of Navarre come to mind, as well as Joan of Kent even though she never actually became queen.

As I talked in the ask I linked, there were moral concerns about a widow's lack of virginity/chastity but there were practical concerns as well. The thing about a widow’s remarriage to the king was the possibility that they would come with children from their previous marriage. Basically, the queen's family/affinity and any countrymen that might come over with her to England (if they were a foreigner like Joanna of Navarre's case) were always held in suspicion. In the case the queen in question bore the king's heir, there were fears of how much the heir's (maternal) half-siblings could influence them, for example. Indeed, this is what happened in Elizabeth Woodville's case, whose sons Thomas and Richard Grey were disliked/antagonised by certain factions at court.

As to Elizabeth's status as a commoner, it’s more ambiguous. All chroniclers and ambassadors agreed that people in England were offended by the king’s marriage but the cause for the offence wasn’t exactly clear: if it was Elizabeth’s lack of suitability as queen (widow or lineage status), the fact that Edward married without the consent of the lords or the fact that the two of them married in secret. The only contemporary English chronicle to link the nobles’ discontent to Elizabeth’s ‘comparatively humble lineage’ was the Croyland continuator. He also acknowledged that her mother was a duchess and never called Elizabeth a commoner, though, so even his report demonstrated that things weren’t as black and white in England. Chroniclers on the continent were more divided about Elizabeth’s status and suitability.

For example, the 1469 continuator of Monstrelet’s Chronicle did not consider Elizabeth a commoner, for he considered her father Sir Richard Woodville of ‘middling rank’. He commented extensively on Elizabeth and Jacquetta’s background and family who were, after all, members of the Burgundian nobility: the counts of St Pol. ‘To disparage Elizabeth would therefore disparage them, something a Burgundian chronicler was unlikely to do’ as Pidgeon remarks. In the eyes of the Monstrelet continuator, who was the one who reported that Edward IV sent for Elizabeth’s Burgundian family to come to her coronation, Jacquetta’s status and lineage made Elizabeth suitable to be queen.

For another Burgundian chronicler, Jean de Wavrin, however, Elizabeth’s mother’s status as a duchess was insufficient.

… [Elizabeth] was beautiful and good, but not the sort of woman appropriate in any way for such a high prince as he is, as he knows well, because she was not the daughter of a duke or earl, her mother had been married to a knight … even though she was the daughter of a duchess and niece of the count of St. Pol, not withstanding all things considered she was not the woman for him, nor to such a prince ought to appertain.

Wavrin’s issue with Elizabeth Woodville is that, even though her mother was a duchess, she wasn’t the daughter of a peer of the realm. Pidgeon speculates that given how Wavrin maintained contact with Warwick and ‘for a while admired him’, Wavrin was actually reporting Warwick’s view of Elizabeth but there’s no way of knowing this for sure.

To complicate matters further, there’s the possibility that Elizabeth’s first husband’s status as a mere knight might have counted against her too. Caspar Weinreich, the writer of the Danzig Chronicle, did call Elizabeth a ‘gentleman’s wife’. Around that time, Eleanor of Poitiers commented that in France ‘all women had to be ranked according to their husbands, however great their own estate was, save for the daughters of kings’. As Lynda Pidgeon comments:

Status is a complex issue and was much discussed at the time [...] A study of status in the Burgundian Netherlands has shown that ‘a distinction was made between higher and lower nobility.… “High” and “low” are concepts with a relative meaning that is difficult to define’. Knights and squires were included in the nobility, and it was accepted that families could rise and fall with new families entering the nobility through service to the ruler. Such new families would then go on to make noble marriages without objection [...] Wavrin and Monstrelet seem to reflect these conflicting views. Monstrelet was simply saying that Sir Richard came from the lower nobility—hence his ‘inferior’ position to his wife and her family who were from the higher nobility. Wavrin took the French view based on a man’s rank in society.

So what I mean to say is that there were many factors that might have explained why people in England were (temporarily at least) dissatisfied with Edward IV’s marriage. That they were dissatisfied is the only thing all chroniclers and ambassadors agreed on. I hope this helps! 🌹x

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Battle of Verneuil was a battle of the Hundred Years' War, fought on 17 August 1424 near Verneuil in Normandy. The battle was a significant English victory. It was a particularly bloody battle, described by the English as a second Agincourt.

The battle started with a short archery exchange between English longbowmen and Scottish archers, after which a force of 2,000 Milanese heavy cavalry on the French side mounted a cavalry charge that brushed aside the ineffective English arrowstorm and wooden archer's stakes, penetrated the formation of English men-at-arms and dispersed one wing of their longbowmen. The Milanese went on to rout the English baggage train and its defenders, looting the train and quitting the field. Fighting on foot, the well-armoured Anglo-Norman and Franco-Scottish men-at-arms clashed in the open in a ferocious hand-to-hand melee that went on for about 45 minutes. The English longbowmen reformed and joined the struggle. The French men-at-arms broke in the end and were slaughtered, with the Scots in particular receiving no quarter from the English. The Milanese heavy cavalry returned to the field at the end of the battle but fled upon discovering the fate of the French force.

Altogether some 6,000 French and allied troops were killed and 200 taken prisoner.[6][7] The Burgundian chronicler Jean de Wavrin estimated 1,600 English killed, although the English commander, John, Duke of Bedford claimed to have lost only two men-at-arms and "a very few archers". The Scots army, led by the earls of Douglas and Buchan (both of whom were killed), was almost destroyed. Many French nobles were taken prisoner, among them the Jean II, Duke of Alençon and Marshal de La Fayette. After Verneuil, the English were able to consolidate their position in Normandy. The Army of Scotland as a distinct unit ceased to play a significant part in the Hundred Years' War, although many Scots remained in French service.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Verneuil

1 note

·

View note

Text

Parliament of 1327

Assassination of Yvain de Galles at the siege of the castle of Mortagne-sur-Gironde – from Jean de Wavrin’s ‘Chronique d’Angleterre’

Wikipedia - "The Parliament of 1327, which sat at the Palace of Westminster between 7 January and 9 March 1327, was instrumental in the transfer of the English crown from King Edward II to his son, Edward III. Edward II had become increasingly unpopular with the English nobility, predominantly because of the excessive influence of unpopular court favourites, the patronage he devoted to them, and his perceived ill-treatment of the nobility. By 1325, even his wife, Queen Isabella, despised him. Towards the end of the year, she took the young Edward to her native France, where she joined and probably entered into a relationship with the powerful and wealthy nobleman Roger Mortimer, whom her husband had exiled. The following year, they invaded England to depose Edward II. Almost immediately, the King's resistance was beset by betrayal, and he eventually abandoned London and fled west, probably to raise an army in Wales or Ireland. He was soon captured and imprisoned. Isabella and Mortimer summoned a parliament to confer legitimacy on their regime. ..."

Wikipedia

amazon: The Origins of the English Parliament, 924-1327

Mortimer and Isabella's invasion route in 1326, Their landing and attack is in green; the King's retreat westward is in blue.

0 notes