#italy 1800

Text

The Battle of Marengo

… as described by one Eugène de Beauharnais in his memoirs. For context: Eugène, aide-de-camp to general Bonaparte, had left Egypt with his stepfather, in Paris had helped to reconcile his mother with general Bonaparte and assisted (according to his memoirs, without completely understanding what was going on) at the coup d’état of 19th Brumaire. However, once Bonaparte had become First Consul, Eugène gave up his post as ADC, as soon as it dawned on him that this job from now on would mostly consist of hanging out in an antechamber and politely introducing guests to the head-of-state of France. Having decided that this was totally uncool, he had gone back to the military. At the time of the second Italian campaign, he was an 18-year-old capitaine de la Garde des Consuls, commanding a compagnie of chasseurs à cheval.

We’re starting the relation a bit before Marengo, with the entry into Milan, as Eugène claims to have met Desaix there one last time.

I assisted at the combat of Buffalore, commanded by general Murat, who showed great vigour in this crossing of the Tésin [Ticino]; the enemy was pushed briskly up into Milan, where we entered in a jumble with his light troops. I made with my company a rather fine charge to force the enemy, who still held the field, to return to the citadel of Milan.

We remained three days in Milan, where the First Consul was occupied in reorganising the republican government; after which we proceeded to Pavia. General Lannes had made the crossing of the Po, about a league below this city. General Desaix had just arrived from Egypt and joined the army at Pavia, at the very moment when the First Consul left; as the troops of the guard were not to cross the Po until the night, I had time to go and see him. As a companion in arms from Egypt, we were delighted to meet again, and general Desaix treated me very well. He spoke to me much about the campaign which was opening and the command which he hoped to obtain; it seemed, moreover, that he foresaw his imminent end, for he uttered this singular statement : "Formerly, the Austrian bullets knew me, I am afraid that they may not recognize me any more."

We crossed the Po during the night, and the next day I was sent with my company, by Stradella, in the direction of Piacenza, to establish communication with general Murat, who had crossed the Po at this point and had effectively seized this city. The next day the affair of Montebello took place, which did so much honour to General Lannes; but I arrived too late to take part in it. The following evening, we pushed in the direction of Alexandria as far as Marengo, where there was a small combat to force the enemy to pass again the Bormida and to abandon this line. The day was very stormy and we had much difficulty in passing the Scrivia whose waters had become very rough. I witnessed the reports which several officers came to make, in the evening, to the first consul, at his bivouac. All agreed in saying that the enemy was withdrawing in haste and that he had broken all his bridges on the Bormida. The first consul had it repeated several times to be more sure, and it was in consequence of these false reports that he directed on Genoa the corps of troops of which he had just given the command to general Desaix in order to lift the siege of this important place, if there was still time.

But, the next morning, when a heavy cannonade was heard on the side of Alexandria, we were quickly drawn out of our error. Soon the first consul learned that the enemy was emerging in force on the plain of Alexandria, and that a great battle was inevitable. One can estimate the anxiety of the general in chief and the anger which he felt at the false reports which had been made to him the day before. Orders were dispatched in all haste to recall general Desaix, who was found near Novi, and who, in spite of this distance, still arrived in time to take part in the action and to decide the winning of the battle. I mentioned this circumstance because it exonerates the first consul from the reproach of improvidence which was made to him in several reports of the battle of Marengo. Those who have had great military commands know what the fate of battles depends on, and how an unforeseeable accident can disturb the best and most skilful combinations.

Our movement of retreat began towards midday and continued until four o'clock; it is during this time that the guard began to take a more active part in the affair. The troops of the line were tired and discouraged; the first consul sent us to support them; we carried ourselves sometimes on the left, sometimes on the right, according to the need; general Lannes, pressed a little sharply by the enemy, wanted to have us make a charge which did not succeed; he had in front of him two battalions and two pieces of artillery behind which was a mass of cavalry in close columns; his troops withdrew in disorder, so that, to give them time to breathe and to rally them, he ordered colonel Bessières, who commanded us, to charge on the enemy column. The terrain was not very favourable, because it was necessary to cross vineyards; nevertheless we passed and arrived within rifle range of these two battalions, which awaited us arms in hand and in the best of spirits. Colonel Bessières, having drawn us up, was preparing to command the charge, when he realised that the enemy cavalry was deploying on our left and was going to turn us. Consequently, he made us turn back to the left, and we crossed the vineyard under the fire of grapeshot and musketry; but, having arrived on the other side, we held our ground well enough to impose on the enemy cavalry. General Lannes was very dissatisfied with this operation and complained bitterly about it. However it is probable that, if we had carried out his orders, few of us would have returned. During the retreat, my chasseurs were charged with destroying the ammunition which we were forced to abandon, and performed this mission with great intrepidity, often waiting until they were joined by the enemy to set fire to the caissons and then jump on horseback.

Finally, towards five o'clock, General Desaix joined us, and the First Consul was able to resume the offensive. The troops of General Lannes, encouraged by this reinforcement, reformed, and soon the offensive began as well as the retrograde march of the enemy. The cavalry of General Kellermann made a very beautiful charge on our left, and, towards the evening, the cavalry of the guard made one not less brilliant. Although the ground did not favour us, since we had two ditches to cross, we rushed with vigour on a column of cavalry much more numerous than us, at the moment when it was deploying; we pushed it up to the first bridges over the waters of the Bormida, always sabering. The melee lasted ten minutes: I was happy enough to get away with two sabre blows on my chabraque. The following day, the first consul, on the account which was given to him of this affair, appointed me squadron leader. My company had suffered quite a bit, because, of one hundred and fifteen horses which I had in the morning, I had only forty-five left in the evening; it is true that a piquet of fifteen chasseurs had remained near the first consul, and that many chasseurs, dismounted or slightly wounded, returned successively.

The day after this battle (June 15, 1800), an armistice was concluded as well as an agreement for the evacuation of Italy; the first consul returned on the 16th to Milan, from where we were at a distance of forty Italian miles; I was charged to escort him from the battlefield to Milan, by following the post. This race, of more than twelve leagues always at the trot and without unbridling, was so tiring, that I arrived at Milan with only seven men.

I hope this is helpful to anyone who’s interested.

#napoleon's family#eugene de beauharnais#Jean-Baptiste Bessières#jean lannes#louis desaix#Battle of Marengo#italy 1800

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Francesco Hayez (Italian, 1791-1882)

The Repentant Mary Magdalene, 1833

Galleria d'arte moderna di Milano

#different quality and size best yet#the repentant mary magdalene#1800s#art#fine art#european art#classical art#europe#european#fine arts#oil painting#europa#mediterranean#italy#italian art#classic art#christentum#christianity#western civilization#mary magdalene#francesco hayez#hayez

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

View of the Church of San Lorenzo fuori le Mura, 1815

By Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg

#art#painting#fine art#classical art#danish art#danish painter#danish artist#19th century art#19th century#church#italy#rome#europe#architecture#european architecture#interior#european art#1800s#early 1800s

727 notes

·

View notes

Photo

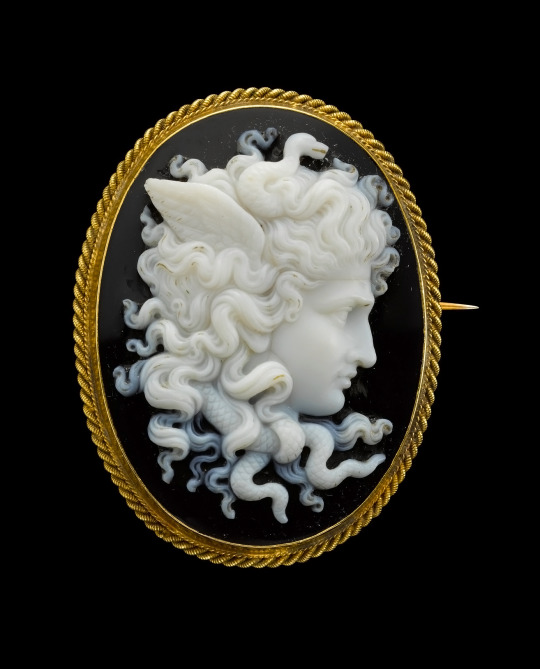

Cameo with Medusa, mid-1800s. Attributed to Luigi Saulini, 1819-1883. Sardonyx, gold mount.

#cratfs#cameo#jewelry#medusa#mythology#myths#legends#greek#craftmanship#carving#1800s#Italy#crafts#antique

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

You can file this one under "fun facts that make me feel insane"

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Gown and train of Marie Louise of Austria, second wife of Napoleon Bonaparte

(Bust of Napoleon and painting of Marie Louise in the background)

Museo Glauco Lombardi

#this dress looks way better here than in the painting for some reason lol#Museo Glauco Lombardi#dress#gown#1800s#19th century fashion#train#ball gown#Parma#Italy#Marie Louise#marie-louise#Marie Louise of Austria#napoleonic#Austria#Habsburg#habsburgs#history of fashion#fashion history#historical fashion

311 notes

·

View notes

Note

what part of italy are machete and vasco from? not their birthplace since from what i've seen you're still workshopping that. where do they live? i assume rome?

In the 1500's setting Vasco lives and was born in Florence, his family has lived there for centuries. Machete was born in Sicily, was taken to Naples to serve as an apprentice and ended up living and working in Rome (and more specifically today's Vatican city, which as you may know has been an independent country since 1929 but wasn't back then). They first met when they were both studying in Venice in their late teens/early twenties.

I think in the modern au they live together somewhere in Florence.

#characters travelling this extensively at the time#from one end of the country to another#may not be very realistic but it's more fun to include a variety of interesting historical locations#let me be greedy and self indulgent for a moment#(not to mention that Italy wasn't unified until late 1800's and was instead made of various states kingdoms and duchies#that didn't always get along with each other that well and were culturally and linguistically diverse#and some of them were actually ruled Spain and Austria for example)#I say this as lovingly as possible but the history of Italian peninsula as a whole is just a real clusterfuck#I feel like I still haven't wrapped my head around it adequately to be explaining any of this to you#but please be patient with me I promise I'm trying my best#answered#anonymous

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sissi Trilogy + Costumes

Ludovika, The Duchess in Bavaria's silver dress in Sissi - The Young Empress (1956) & Sissi - Fateful Years of an Empress (1957).

// requested by @thatmawe

#Sissi Trilogy#Sissi The Young Empress#Sissi Fateful Years of an Empress#Ludovika of Bavaria#Ludovika in Bavaria#costumes#costume drama#costumesource#period drama#perioddramaedit#1800s#19th century#silver#Budapest#Hungary#Venice#Veneto#Italy#Europe#requests

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Il tempo dell’oppressione é finito perché noi briganti combattiamo.

BRIGANTI - 23 Aprile (Netflix)

#briganti#briganti netflix#italiansedit#perioddramaedit#it’s 1800s southern italy#xix century#tvedit#netflixedit#edits*#non mi convince sinceramente ma le scene erano carine

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been wanting to make this for a while//

Basically that one painting that was referenced in the Buon San Valentino arc (’Italia und Germania’ by Overbeck), but they’re wearing suits because I love suits.

#hetalia#gerita#aph italy#aph germany#hws italy#hws germany#ary makes art#that Spaus art without lines was kinda an exercise to build up some confidence to make this although I didn't use the exact same technique#I guess I don't mind how it came out considering I'm pretty new to painting style ;w;#the background was kinda traced from the actual painting but honestly that didn't make the process any faster lmao#also I considered adding the flower/leaf crowns but idk they ended up feeling out of place to me so I didn't#while I was working on this it kept reminding me of a great GerIta fic I read some time ago by lady-lisa on ao3#I'll link it later I just LOVE vintage/historical stuff especially for some ships like GerIta and pre-WWs Germany is just adorable aaa#I mean before he got real scarred for life#and he was just some kind of prince out of a German 1800s novel

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soult being wounded

As we' ve had quite a few medical topics here lately, the story of how Soult was wounded seems to fit quite well. After all, even though he kept the leg and was later even able to make forced marches (retreat from Portugal!), it seems to have remained stiff and to have hindered him throughout his life. Above all, the disability made him appear older than he was, at least that is what several eyewitnesses note in their descriptions.

Soult received the wound on 13 May 1800, during an excursion he made from besieged Genoa to obtain food. A similar foray two days earlier had gone well, this one failed spectacularly.

Fortunately, we do have an eyewitness account of the event, that is, the main participant. We start at a moment when he hopes to have rallied his men. [Translated from “Mémoires du maréchal-général Soult, duc de Dalmatie. Partie 1, Tome 3″:]

Everything seemed to promise us, after this last effort, a decisive success. I entered the line beyond the enemy camp, where the fire was very intense and almost at point blank range. To put an end to it, I prepared to carry out a general charge, when a bullet shattered my right leg. I fall; people surround me; someone cries out that I am dead; people believe him, when they see my hat being carried away. Some want to take me away, while others want to defend me. I regain consciousness [...]

“Hey! Give me back my hat!”

[…] I order that I be left and that the enemies be repelled. At my voice, the troop revives and still shows a remnant of vigour; but that is the end of our progress: everything changes to our disadvantage. The Austrians, who had noticed some hesitation in our ranks, became audacious. On our side, the ranks falter, some soldiers begin to move away, [...].

… until everyone stops listening to the officers and starts running. At which point people with only one good leg clearly are at a disadvantage.

[...] Some soldiers wanted to carry me; but the ground was so slippery, on these steep slopes, that they could not succeed, and I compromised them too, mingled, as we were, with the enemies. I ordered them to leave me, and I charged them to hand over my sword to General Masséna; I allowed only my brother and Lieutenant Hulot, both my aides-de-camp, to remain with me. They tried in their turn, but without more success, to withdraw me at least from the midst of the fire, by carrying me on a stretcher made with rifles or on their shoulders. It was only by dragging myself on my back, and holding my broken leg in the air, that I managed to gain the shelter of a rock; I was in great pain.

That I will believe.

The rock preserved us from a first danger, but we were exposed there to the abuses of the Austrian soldiers, who, in order to get our spoils, could give us a bad time; my watch and the little money I had on me had served to satisfy the first, and we had nothing more to offer to satisfy the greed of the others. We wished to place ourselves, as soon as possible, in the hands of a guard who would answer for us; but it was not easy to find one. My brother despised the danger and went to meet the enemies. Before being recognised, he was several times almost killed by bullets; he nevertheless finally arrived, and asked for help for me. On learning that I was to be his prisoner, the Count of Hohenzollern hastened to send me some, and he had me carried to a cottage situated behind the camp, where Austrian surgeons came at once to apply the first aid to my wound.

A first aid which, however, was not quite to Soult’s likings:

I received all the assistance that could be given to me; but, either by prevention or because the Austrian surgeons who treated me lacked instruction, as their clumsiness made me fear, I asked the count of Hohenzollern for permission to have Doctor Cothenet, surgeon-major of the 25th light half-brigade, who had my confidence, come from Genoa. He granted it to me with eagerness, and I wrote to general Masséna to ask him to send him to me; at the same time I reassured general Masséna on my account, by giving him news of me. I wrote this letter, on the back of the Austrian surgeon who was putting the apparatus on me. He made me suffer horribly by his clumsiness, and he did not dare to touch my wound, to dilate it. However, the operation was necessary to prevent the accidents that could have occurred later. Impatient, I did it myself, after having taken the surgeon's scalpel out of his hands; it was easy and not very painful. I attributed the promptness of my recovery to this foresight.

I’m not sure what apparatus was applied there and why Soult had to open his own leg wound some more; I’m also not sure I want to know. But I can just see Soult, at the end of his nerves, wrestle the scalpel from the doctor in order to do whatever he considered necessary himself.

“And now turn around so I can write a letter to my commanding general on your back. I want an actual surgeon here!”

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ferdinando Andreini (Italian, 1843-1922)

Nereid, 1874

#Ferdinando Andreini#italian art#italy#italian#1800s#nereid#art#classical art#sculpture#fine art#european art#europe#european#oil painting#fine arts#europa#mediterranean#southern europe#female

438 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forst Castle on the Adige near Merano, 1873

By Alois Kirnig

#art#painting#fine art#classical art#czech painter#czech art#oil painting#19th century art#italy#nature#europe#castle#beauty#european art#czech artist#1800s

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

by suspiciousminds

301 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ladies please share to spread the word about two exhibits featuring women artists in two different cities

Artemisia Gentileschi, Self Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria (ca. 1615–17). Collection of the National Gallery, London.

Renaissance art calls to mind some of the greatest names in art history—Da Vinci, Raphael, Michelangelo, and Donatello, just to name a few. Lesser known, however, are the influential women artists who shaped the era.

Referring to a period that bridged the end of the Middle Ages and early Modernism, the Renaissance was marked by a widespread effort to recover and advance the accomplishments of classical antiquity. Originating in Florence, Italy, but soon spreading throughout Europe, Renaissance art saw the advent of advanced linear perspective and an increase in realism. Many women artists—famous in their own time—were among these great visionaries.

Though for centuries, these women artists were largely overlooked in the annals of art history, contemporary scholarship has begun a long overdue reappraisal and rediscovery of their lives and works. Evidence of this resurgence of interest in the women artists of the Renaissance can be seen in the two current major museum shows in the U.S. that are dedicated to just that. “Strong Women in Renaissance Italy” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston brings together over 100 works from the 14th through early 17th century, exploring the lives and work of Italian women artists and is on view through January 7, 2024. At the Baltimore Museum of Art, “Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400–1800” is a sweeping exhibition that aims to rectify critical oversight and bring awareness to historical women artists, and is also on view through January 7, 2024,.

In light of these two important exhibitions, we’ve brought together a brief introduction to five Renaissance women artists whom we think you should know.

Plautilla Nelli (1524–1588)

Plautilla Nelli, St. Catherine with Lily (ca. 1550). Collection of Le Gallerie Degli Uffizi, Florence.

Plautilla Nelli was a nun of the Dominican order at the convent of St. Catherine of Siena in Florence—and is considered by many scholars to be the first-known woman artist of Renaissance Italy. A self-taught painter, Nelli led a women’s artist workshop from the convent, and she was one of the few women mentioned in Vasari’s seminal treatise Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Because she developed her practice without formal training and was forbidden from studying male nudes, Nelli frequently copied works by other artists, as well as motifs from religious texts and sculpture.

Nelli’s work recently came into the limelight for her immense painting Last Supper, dating to 1568. Measuring over 21 feet long and 6 feet high, the painting remained in her convent’s refectory until the early 19th century, before being moved to another convent’s refectory and, ultimately, being placed in storage. Following an early 20th-century restoration and several more moves, it went on view to the public for the first time in over four centuries at the Santa Maria Novella Museum in 2019. Hanging alongside other masterworks by artists like Brunelleschi, it finally is getting the widespread recognition it deserves.

Catharina van Hemessen (1528–after 1565)

Catharina van Hemessen, Self-Portrait (1548). Collection of Kunstmuseum Basel.

Northern Renaissance painter Catharina van Hemessen was the daughter of prominent Mannerist painter Jan Sanders van Hemessen, and is the earliest Flemish woman painter with verified work that still exists today. Hailing from Antwerp, van Hemessen achieved success in her lifetime, including obtaining the patronage of Maria of Austria, regent of the Low Countries. She was included both in Vasari’s collection of artist biographies, as well as artist biographer Lodovico Guicciardini’s Description of the Low Countries (1567). Van Hemessen’s greatest claim to fame, however, is that she is attributed with completing the first known self-portrait of an artist at their easel—a compositional approach that has become a pillar of the art historical canon, as it has been taken up by artists ranging from Rembrandt van Rijn to Norman Rockwell.

Though she created religious images, she was most well known as a portraitist. Eight portraits and two religious compositions signed by van Hemessen have survived, dating between 1548 and 1552. Notably, there are no verifiable works dating to later than 1554, which have led scholars to believe she ceased painting following her marriage to organist Christian de Morien that year—though there are records she continued to teach three male apprentices.

Sofonisba Anguissola (ca. 1532–1625)

Sofonisba Anguissola, Self-portrait (ca. 1535–1625). Collection of Łańcut Castle Museum, Poland.

Sofonisba Anguissola was one of the most successful women artists of the Renaissance, with a reputation that rose to international acclaim in her lifetime. Born into a noble Milanese family, Anguissola was able to pursue her artistic aspirations with the support of her family, and began her formal training as a teenager; first apprenticing with Bernardino Campi for three years before working with Bernardino Gatti. Her position also allowed for her to become acquainted with Michelangelo, whom she exchanged drawings with. Her early career saw her complete numerous self-portraits as well as portraits of her sisters, including The Game of Chess (1555), which are noted for their realism and liveliness.

Sofonisba Anguissola, The Game of Chess (ca. 1555). Collection of the National Museum in Poznań, Poland.

Anguissola’s reputation as a painter quickly spread, and she was invited to join the court of King Philip II of Spain in Madrid in approximately 1559. Throughout her 14-year tenure there, she completed many official portraits of both members of the royal family and members of the court, adopting the formal and intricate style expected—though unfortunately, no work from this period survived due to a palace fire in the 18th century. Having garnered considerable royal favor, she ultimately spent the remainder of her life continuing to paint as well as teach and engage with young, up-and-coming artists. In 1624, one such young artist by the name of Anthony van Dyck visited Anguissola and recorded his visit in a series of sketches and noted that he learned more about the principles of painting from her than from anything else he had encountered.

Lavinia Fontana (1552–1614)

Lavinia Fontana, Self-portrait at the Spinet with Maid (1577). Collection of the Accademia Nazionale di San Luca, Rome.

Trained by her artist father Prospero Fontana, a teacher at the School of Bologna, Lavinia Fontana is considered the first professional woman artist insofar as she supported herself and her family solely on the income from her commissions. Unconventional for the time, her husband acted as her agent and took a primary role in childcare for their 11 children. She began her commercial practice in her mid-twenties, creating small devotional paintings, but later began and excelled at creating portraits—and became a favorite of Bolognese noblewomen who vied for her services. Unusual for the period, she also created large-scale mythological or religious paintings that occasionally featured female nudes.

Lavinia Fontana, The Visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon (1599). Collection of the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin.

In the early years of the 17th century, she was invited to Rome at the invitation of Pope Clement VIII and was soon appointed as an official portraitist at the Vatican, counting Pope Paul V as one of her sitters. Her career success continued to thrive, as evidenced by the numerous honors she received, and the bronze portrait medallion cast in her likeness by sculptor and architect Felice Antonio Casoni. She was also one of the first women elected to the Accademia di San Luca in Rome.

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1653)

Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-portrait as a Lute Player (ca. 1615–1618). Collection of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford.

Unlike many of her predecessors, Artemisia Gentileschi has maintained a level of renown over the centuries, with her dramatic and dynamic oeuvre that was unprecedented in her own time. Her Baroque compositions helped usher in a new era of painting. Today, her paintings draw the attention of global audiences. Born in Rome, her father was the painter Orazio Gentileschi, who trained Artemisia starting at an early age. Inspired greatly by the work of Caravaggio and his use of high-contrast compositions, her paintings garnered and maintained attention for their naturalism and nuance, as they broke from the idealism of generations past.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes (ca. 1623–1625). Collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts.

In 1612, Gentileschi relocated to Florence, which is where she first achieved major career success, including securing patronage from the House of Medici and being the first woman to attend the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno. From her oeuvre, Gentileschi has become most well-known for her self-portraits as well as religious scenes, specifically the story of Judith Beheading Holofernes—of which there are at least six known variations she completed. Gentileschi’s tendency to portray women as the protagonists of her works—and as equals to their male counterparts—made her innovative in her time and has subsequently secured her legacy as one of the most influential artists within Western art history—of either sex.

#Women in Art#Strong Women in Renaissance Italy#Museum of Fine Arts#Boston#There until January 7 2024#Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe 1400 -1800#Baltimore Museum of Art#Plautilla Nelli (1524–1588)#Catharina van Hemessen (1528–after 1565)#Catharina van Hemessen created a whole genre in self portraits#Sofonisba Anguissola (ca. 1532–1625)#Lavinia Fontana (1552–1614)#Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1653)

10 notes

·

View notes