#iceland women

Video

#cecilía rán rúnarsdóttir#glódís perla viggósdóttir#karólína lea vilhjálmsdóttir#fcb frauen#bayern munich frauen#islwnt#iceland wnt#iceland women

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

lets say hypothetically that i wanted men to die and suffer for all time

#which is more than the money made annually by the 50 biggest companies in the world btw#apparently icelandic women went on an unpaid labour strike in the 70s and it brought the whole country to a standstill can we pLEASE bring#this back!!#a;so the countries with the smallest divides#it isnt that the men do more#its countries with better social care etc#WHICH MEANS the gap still exists#just becomes a class AND gender gap#the average USamerican woman spends more than 4h a day doing unpaid work#which is literally like a second job#imagine what u coudl do with an extra four hours in ur day

623 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In the mid-1700s, a seawoman in Iceland named Björg Einarsdóttir composed a poem teasing men on her boat for their weak rowing:

Do row better my dear man,

Fear not to hurt the ocean.

Set your shoulders if you can

Into harder motion.

Einarsdóttir was not only a talented poet but an excellent fisher. She often caught more fish than other crew members, and people believed that her ability to lure the animals was supernatural. When she was dying, she reportedly passed on this uncanny skill to a farmer by writing a poem about him catching trout.

Her work at sea may seem unusual. After all, fishing is generally considered a man’s job. But recent work by an American researcher, Margaret Willson, suggests that Einarsdóttir was one of hundreds of Icelandic women in the 18th and 19th centuries who braved towering waves and icy waters to catch fish. Willson’s team combed through historical archives and publications to gather examples ranging from a female captain who led crews made up entirely of women, to expectant mothers who rowed late into pregnancy.

The sea “wasn’t a male space,” says Willson, a cultural anthropologist at the University of Washington in Seattle and a former seawoman. “It was not a feminist act in any way for them to go to sea.” It was just part of everyday life."

#history#women in history#women's history#women's history month#seawomen#iceland#icelandic history#18th century#19th century#working women#badass women#Björg Einarsdóttir

220 notes

·

View notes

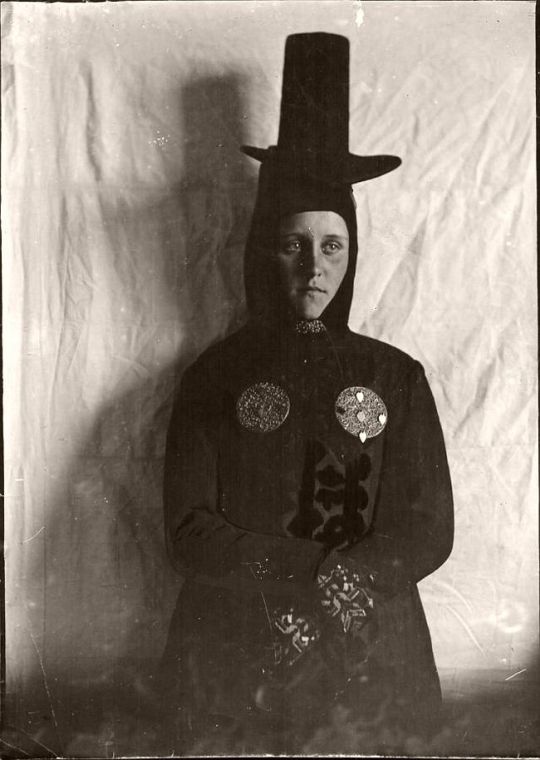

Photo

Portraits of Icelandic People by Daniel Bruun

The Danish National Museum has a large collection of photographs, many of which are available online. Since Iceland was a part of the Danish Kingdom until 1944, the museum contains a fascinating collection of old photographs taken in Iceland around the turn of the century 1900. Among these collections is the Daniel Bruun collection.

https://icelandmag.is/tags/danish-national-museum

#daniel bruun#portraits of icelandic people#photographic portraiture#portraits of women#icelandic#woman#women#1900s#daniel bruun collection

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vigdís Finnbogadóttir (born 15 April 1930) is an Icelandic politician who served as the fourth president of Iceland from 1980 to 1996.

Vigdís is the first woman in the world to be democratically elected as president.

#radfem#radical feminism#radfem safe#radblr#radfems do interact#feminism#radfems do touch#women's rights#women's liberation#Vigdís Finnbogadóttir#iceland#icelandic#female president#female politician#female leader#women in history#herstory#important women#women in politics

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Giulia Gwinn

Germany vs Iceland (26/09/2023)

#Giulia Gwinn#Germany vs Iceland#UWNL#UEFA Women's Nations League#Women's football#Woso#German WNT#GER WNT#DFB Frauen#My gif

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

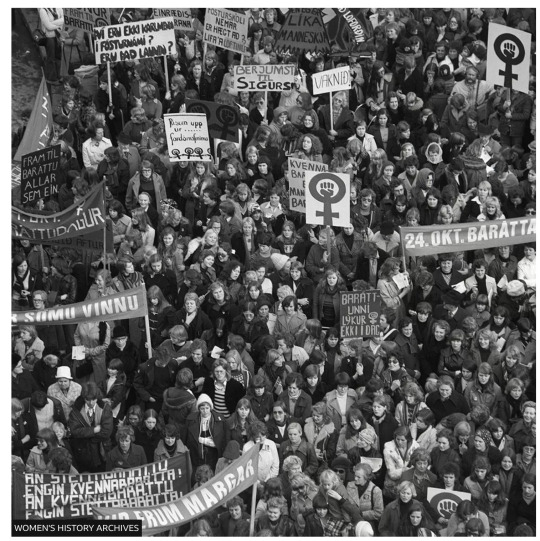

Any other ladies out there think International Women’s Day would have more impact if it was moved to October 24th?

“But Vigdis insists she would never have been president had it not been for the events of one sunny day - 24 October 1975 - when 90% of women in the country decided to demonstrate their importance by going on strike.“

The idea of a strike was first proposed by the Red Stockings, a radical women's movement founded in 1970, but to some Icelandic women it felt too confrontational.

"The Red Stockings movement had caused quite a stir already for their attack against traditional views of women - especially among older generations of women whom had tried to master the art of being a perfect housewife and homemaker," says Ragnheidur Kristjansdottir, senior lecturer in History at the University of Iceland.

But when the strike was renamed "Women's Day Off" it secured near-universal support, including solid backing from the unions.

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Glódís Perla Viggósdóttir wins Icelandic Women’s Footballer of the Year

#so deserved queen!#glodis perla viggosdottir#glódís perla viggósdóttir#islwnt#iceland wnt#iceland women

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

my grandfather’s kitchen

iceland | @hannalchemy

#iceland#film#film photography#fujifilm#black and white#35mm#35mm film#35mm camera#analogue#analog#Analog Vibes#nikon#nikon camera#nikon f100#women photographers#Women Artists

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The day women shut down Iceland | Vox

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Strong seawomen

You can read more about Iceland's seawomen here!

"Born in 1829, Ísafold Runólfsdóttir grew up on a remote farm in East Iceland near present-day Vopnafjördur. From a family celebrated for their singular strength, Ísafold was known as the best and strongest of the bunch. She was so renowned for her strength that she became part of the folk history of the area, with accounts of her taking on the form and style of the traditional Icelandic narrative tales. She is described as very intelligent, tall, broad-shouldered, handsome with a firm expression, bold, eager in her work, unsparing in her words, unafraid to speak her mind (her language sometimes a bit crass) and overall considered a hero both at sea and on land.

Ísafold went to sea when she was “very young,” first rowing with her father Runólfur. Fishing became her main source of income. She often went out alone, and only the “hardest workers could hope to match her.” As with so many of the seawomen in the historical record, it was not so much for her fishing that Ísafold is remembered but for her personality and phenomenal strength. This included her ability to pull her heavy wooden boat ashore alone—an unheard-of feat. One young seaman recalled that once, when the boat was getting in danger upon encountering rough waves as they neared shore, Ísafold jumped from the boat into the waves, grabbed him, and then tossed him with such a throw that he landed safely on shore. Then she dragged the boat ashore after her. Another account describes how, when unloading hundred-pound bags from the boats with the men, who carried one bag each, Ísafold would often remark, “Well, you are not so strong,” and grab two bags, one in each hand.6 Some speculated that it was the fish oil she took religiously that aided her famous strength—but that she was stronger than almost anyone else, man or woman, was undisputed.

Ísafold also had exceptional skill and strength at a wrestling and martial art form called glíma. Brought from Norway by the early Icelandic settlers, glíma was played in medieval times by men, women, and gods alike—and considered fundamental for a warrior. In the 1800s, it was still popular, and as Ísafold’s reputation at glíma grew, many men came to test themselves against her, including some of the area’s best-known fighters. But always these men found themselves facedown in the “cow muck” in the barn, defeated by Ísafold. Eventually, Ívar Jónsson, a “mountain of a man in both size and strength” came to challenge Ísafold. Their fight was both “long and even,” but “being an experienced fighter,” he was eventually able to take Ísafold to the ground, where she admitted defeat. Even so, Ívar affirmed that “he had never before or since fought a worthier opponent”.

Ísafold was clearly both attractive and independent, and the descriptions of her thwarting sexually aggressive men (usually reported as foreigners), repeated to the delight of the town, take on the tone of parable. These accounts always start by outlining a situation in which some very foolish man or men decide to harass Ísafold. (...).

At this juncture in each account, someone goes running to Ísafold’s father, warning him that his daughter is in danger. Each time he declines to budge, saying that his “little girl” can take care of herself. And each time she competently does. On the ship, some men flee but the rest she sends “one by one rolling down the gangway.” In the other cases, she comes down the stairs holding the man under her arm with his head hanging down. As for the man who wished to “enjoy” her, Ísafold stomps down the stairs with him under her arm, his trousers around his ankles as he ineffectually screams and curses at her. She strides out of the house with him, down to the sea, and, with a grin, tosses him into the water. The laughter of their audience reportedly “rang around them.” The man manages to wade to land, pulling his trousers up as he goes, loudly cursing the woman who did this to him. After this incident, he was reportedly not seen in public for a long time. At each story’s conclusion, various townspeople thank Ísafold, saying that the men are known for their uncontrolled temper or have “been a bother to other women before her.”

Beyond using her physical strength to protect herself, it was clear that Ísafold, like other seawomen such as Foreman Thurídur, stood up for her rights and voiced her opinions—sometimes in fairly outrageous ways. One week in church, Ísafold found the pastor’s sermon objectionable (the account, sadly, neglects to tell us what he said). After the communion service had concluded, she darted outside ahead of the pastor and squatted by the church door, as if to relieve herself. As the pastor walked by, she said, “I guess this was rather pointless. The sacrament has already passed through.”

Ísafold eventually took over the family farm, and adopted her sister’s child after that sister’s death. Although, sadly, Ísafold’s first love died of illness—after she had braved trekking through deep snow and a blizzard trying to save him—she later married and had one son, whom she named after the Saga hero Úlfar the Strong. In addition to her amazing strength and fishing abilities, Ísafold had great skill for natural medicine, healing wounds, and even surgery; when her adopted son tore off two fingers in an accident, she successfully reattached them. According to a local pastor, Ísafold remained strong, living to be “an old lady,” and was still living on a farm as late as 1901. Another source, while agreeing that she had a long life, recorded that after her father died in 1870, Ísafold left farming and moved to a home by the sea.

These stories of Ísafold are rollicking and fun, but they remind us that in the rowboats, the ability and strength to row against wind and current could make the difference between a safe homecoming and death. Even in the early Icelandic Sagas, women with such skills were recognized, though not glorified in the way the men were. In the Saga of Gísli Súrsson, Gísli, who is being hunted down by numerous enemies, travels to Breidafjördur to take refuge with his friend Ingjaldur. When his enemies get wind of his whereabouts, fifteen of them board a ship and head across the bay in pursuit. Meanwhile, Gísli has gone out fishing with Ingjaldur and two of his slaves, a man Svartur and a woman Bóthildur. Sighting the enemy ship, Gísli hurriedly changes places and clothes with Svartur, who rows away with Ingjaldur. Gísli, however, joins Bóthildur, pretending to be Ingjaldur’s well-known “half-wit” son. Ingjaldur and Svartur head for a nearby island, while Bóthildur rows toward the enemies. Through cleverly implying doubt as to the identity of Ingjaldur’s companion, she misleads them into pursuing the other men, thereby saving Gísli’s life. By the time the enemies realize they have been fooled, Bóthildur is already far down the channel. With many men rowing, the enemies rapidly gain on them, but Bóthildur rows so fast that the “steam comes off her,” getting Gísli ashore just before the enemies catch up to them. In thanks, Gísli gives Bóthildur gold to take to Ingjaldur and his wife, along with his request that they free not only her but Svartur as well.

Strength in working at sea was always important, and people who were exceptional got noticed. Examples of women dragging the heavy medieval ships ashore do exist in the Sagas, although later it seems not to have been common until the 1707–8 Plague killed a quarter of the population. During that terrible time, the women dragged up the ships and buried the dead. From then until the early 1900s, when boat construction changed, women dragged the boats to shore alongside their crewmates. Even well into the mid-1900s, on seaside farms, people, including women, were still dragging their boats to the sea. Unnur, the seawoman featured on the cover of this book, recalled this from her youth in the 1950s:

One of my first memories of our boat was helping to push it down to the sea in spring using ribs of whales instead of wooden planks for the boat to slide on. There was a drum at the shore from which we would unwind the wire holding the boat. At the same time a flock of people were supporting the boat so it would stay upright. Then as one rib was loose above the boat it was loose above the boat it was carried down below the boat and so on every time the boat moved further down the slope. When the boat reached the water all ribs were taken and put in the shed.

Historical accounts of strong female rowers also continue throughout the centuries: women rowed record distances—with no helping wind—in record time; seawomen in their seventies exhausted their strong twentysomething-year-old sons; rescues were accomplished due to a woman’s superior rowing; and numerous women rowed in a competitive dare, changing the rhythm to see if the other rowers could keep up. The historical record is full of these women’s adventures, such as those of another seawoman from East Iceland, Helga Sigurdardóttir. Born in 1823, Helga lived to be almost ninety, and, in addition to fishing, she managed her own farm, including the haying and tending the sheep. Like Gudný Sigrídur Magnúsdóttir, Helga ran over mountains, but unless the ground was frozen or it was raining, she ran barefoot. She fished in the spring and autumn, and always wanted someone of equal strength to row with her—something apparently not so easy to find. She was particularly remembered for outrowing everyone in both boats when her boat and a companion boat got caught in a fierce storm together; her strength and encouragement were credited with getting the entire group through the danger safely."

Seawomen of Iceland: Survival on the edge, Margaret Wilson

#history#women in history#women's history#Ísafold Runólfsdóttir#iceland#icelandic history#seawomen#feminism#badass women#herstory#women's history month#Helga Sigurdardóttir#Bóthildur#18th century#19th century#working women#historical figures

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sigriður Zoëga :: Women on the Banks of the Lake, 1915 © The National Museum of Iceland, Reykjavik. From: A World History of Women Photographers. Thames&Hudson. | src l'œil de la photographie

view on wordPress

#icelandic photographer#women artists#landscape#women photographers#sigridur zoega#Sigriður Zoëga#lake#1910s#waterscape#iceland

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

iceland apparently just changed the basketball laws n now competitions n teams r no longer gender segregated!

so girl teams can go against boy teams OR! teams can have mixed genders!

link for those curious(its in icelandic tho)

#its only in the youth league apparently but its a Huge start!#so while the world cries about the Unfairness of the horrible Evil trans women wanting to play sports n how Unfair that is for the Poor Poor#little cis women qwq#icelandic women are asking to play against Cis Men#and With them!#and this also just bipasses wthe entire trans issue! since its not Womens and Mens sports now#its just Sports!'#the whole trans thing wasnt mentioned at all in the news article so i dont know if that had anything to do with this but with how hot of#a topic thats been lately#felt relevant to bring up#and also just watched a video about the whole issue that actually talks about how sports didnt use to be split between genders#and it only started happening when women started Winning stuff#but i really hope this goes well and that its the start of other sports doing the same thing#rambles

52 notes

·

View notes