#god eater vs a deity of destruction

Text

With Predathos being trapped in Ruidus as a prison, and Tharizdun having been banished to the Far Realm after the Calamity and wants to annihilate everything that's ever been created, I'm morbidly fascinated with the idea of these beings facing one another

#critical role#campaign 3#predathos#tharizdun#exandrian pantheon#god eater vs a deity of destruction#bells hells#granted this could end up with everything imploding but fuck that would be fascinating#betrayer gods#cr

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm thinking of doing a Hermit god Au, here's what I have so far, and justifications

Grian- God of war

Tends to be heavily involved in/the cause of all wars on the server, and has a tendency to start small conflicts too (tree war with mumbo, boatem vs. Big eyes)

Cleo-- god of death/ queen of the underworld

Zombie.

Scar-- god of plants/agriculture

Known for terraforming, tends to make builds with a lot of plants

Gem-- god of animals

This is entirely because of the deer she built last season

Etho-- god of music

He does some really cool stuff with noteblocks, and I feel that's pretty unique on this server

Xisuma-- god of creation

Mainly because he's the admin, so it would make sense to have him as some creator deity

Doc-- god of destruction

Mostly because of the World Eater

Bdubs-- god of sleep

I don't think I need to explain this one

So that's it so far. Might do art for this, too. If you have any suggestions for what other hermits should be the god of, that would be really helpful! I'm not doing things like god of building, redstone, or chaos, because that could apply to too many of them

#etho#ethoslab#bdubs#bdouble0#grian#geminitay#gem#doc#docm77#gooodtimeswithscar#zombiecleo#xisuma#hermitcraft smp#hermitcraft#mcyt#hermitcraft god au

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kicking things off with a post talking about Blaze and the Sol Empire.

Blaze resides in the Sol Dimension — a universe than runs parallel to Sonic's world, a.k.a the Prime Dimension. While the two obviously have their differences, there are plenty of similarities as well; chaos emeralds vs sol emeralds being an example.

The Kingdom of Sol, also known as the Sol Empire, is an extensive group of islands ruled over by the current acting monarch. It's been active for many years and carries a strong maritime tradition, due to the ocean that hugs their borders. With a powerful navy, bountiful resources, and a highly affluent economy, Sol is thriving.

In recent years, Blaze had her coronation and is now the only sovereign of Sol. Her formal title is King; one she chose herself after a long family history of Queens. During her time as Princess, she would frequently carry out royal duties by herself; not much has changed, aside from the level of responsibility.

But responsibility has never scared her, given the past she's endured.

Blaze's lineage comes with a secret. It's followed her ancestors — specifically, reigning monarchs — for many, many years, and finally found it's way to her the day of her mother's death. The gift (a burden, she used to say) of flame. A soul covered in fire. The deity called Iblis.

History tells the tale of two gods, equal halves, revered by all. Iblis the Radiant, god of the sun, and Mephiles the Dark, god of time; co-existing, never one without the other. They would maintain the harmony of this world for centuries... until one day, Mephiles went astray. Without it's other half, Iblis lost control and filled the land with a raging inferno. They brought about mass destruction, and the Sol Dimension was nearly lost.

Thankfully, a hero rose up — the original Queen of Sol. A warrior with boundless courage, who led her kingdom to prosperity and faced their demise with no fear. Using her scepter and The Power of the Stars, she sealed Mephiles away inside it, nullifying all power. With no room left in the wand, she was forced to lock Iblis away elsewhere... inside her very soul. The two became one, and both gods were now in their eternal tombs. History would remember her as The Goddess of the Flames.

Blaze doesn't remember much about her mother. She was only young when she passed, and her farewell gift was a ritual that bestowed her a god. But she remembers her sharing this story, and how proud she was of their history. It took a long time for her to even begin to understand that sentiment. On bad days, she still doesn't.

The events of Sonic Rush introduce us to the story of '06. With Sol and Prime being linked ("like the north and south poles of a magnet..."), colliding into one another, the stability between them starts to fray. It's when Blaze goes Burning Blaze, and Sonic into Super Sonic, that the dimensions finally merge, creating the stage for '06. The Sol Empire becomes Soleanna, Elise is sealed with Iblis, and the Jeweled Scepter becomes the Scepter of Darkness. Blaze is sent into the future during all of the chaos, where she meets Silver.

Blaze loses her memories during all of this and only retains her fire powers as some kind of fragmented anomaly of what once was. Her and Elise are twin flames /haha.

When Blaze seals Iblis inside herself, a part of the timeline "corrects" itself and she is sent back to the Sol Dimension. You can briefly see her turning into Burning Blaze, since she's returning to the point in time when everything broke.

Solaris is "gone" when Elise blows out the flame at the end of the game. The only version of Iblis remaining is with Blaze in the Sol Dimension, and the remnants of Mephiles turn into the Time Eater. Some things stick around, such as Soleanna, because time is weird like that. Whatever.

Shenanigans continue like normal.

#* ∙ ♕ / blaze : headcanons.#* ∙ ♕ / blaze : character study.#readmore for length so i don't suffocate your dash#anyways having blaze on this multi means i finally get to share all these headcanons#welcome to my personal hell (mashes 06 and rush together like barbie dolls)

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

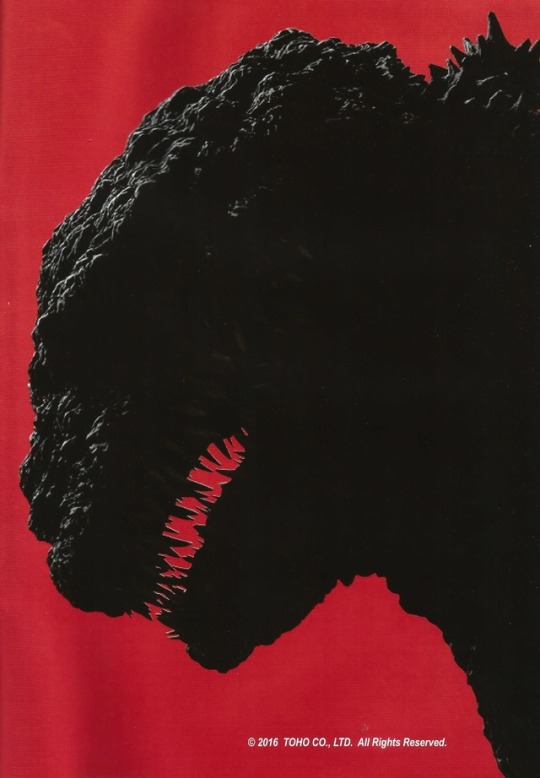

I wrote an article on Shin Godzilla and its place within the franchise for the Glasgow Film Festival/FrightFest brochure! It’s a thrill to have something I’ve written included in an official screening programme, especially since the Big G himself adorns the cover. The article as it appears in the brochure is an abridged version of my original copy (including an irritating factual error). My original unabridged article can be read under the cut below:

“Shin”: a Japanese adjective with different connotations dependent upon context, among them “true”, “new”, “real”, and even “God”. Within the context of Hideaki Anno and Shinji Higuchi’s Shin Godzilla, however, perhaps the meaning we can most appropriately attribute is “pure”. Far from a competitive statement of superiority aimed at Gareth Edwards’ 2014 Hollywood Godzilla film, the “shin” in Shin Godzilla – the Japanese box office record-setting, critically acclaimed reboot to Toho’s iconic monster series - can be interpreted as referring to the title creature itself as portrayed in Anno and Higuchi’s film: a “perfect organism” that rapidly evolves to adapt to and counter whichever environment it finds itself in. “Truly a God incarnate”, Kayako Ann Paterson (Satomi Ishihara) observes, when faced with the devastating reality of Godzilla’s resurgence.

Paterson’s observation harkens back to the creature’s cinematic debut in Ishiro Honda’s 1954 masterpiece Godzilla, which deserves to be ranked alongside Dr. Strangelove and Hiroshima, Mon Amour as one of cinema’s finest anti-nuclear protests. In the film, Godzilla is portrayed as nothing less than a vengeful, malevolent deity, and is even worshipped as such by the residents of Odo Island, where he first makes landfall. Among the most versatile and allegorically fluid characters in cinema, Godzilla has been a world-threatening tyrant in films such as 1962’s King Kong vs. Godzilla and 1964’s Mothra vs. Godzilla, to a titanic superhero to a whole generation of Japanese children, as seen in later films like Godzilla vs. Hedorah (1971) and Godzilla vs. Megalon (1973). The original series of films lasted from 1954 to 1975, but Godzilla would return to his villainous, destructive roots in the 1984 series reboot The Return of Godzilla (re-edited in the US as Godzilla 1985), and would remain this way through to 1995’s Godzilla vs. Destoroyah. After a controversial detour to Hollywood in 1998, the Japanese Godzilla would return in 1999’s Godzilla 2000: Millennium, in a series of movies that lasted through to 2004, the franchise’s fiftieth anniversary. Godzilla would return to the big screen (and Hollywood) for his sixtieth anniversary in 2014, in Gareth Edwards’ Godzilla. Inspired by the international success of Edwards’ film, Toho decided it was time to resurrect their Godzilla.

Hideaki Anno, most commonly known worldwide as the creator of the anime mega-hit Neon Genesis Evangelion, is a natural fit for Shin Godzilla, Toho’s first domestically produced Godzilla film since Godzilla: Final Wars in 2004. Outside of his studying at the Osaka University of Arts (from which he was eventually expelled), Anno would toil in creating independent tokusatsu (a Japanese term roughly meaning “special effects film”) features of his own, including one in which he himself portrays the iconic Japanese superhero Ultraman, harnessing creativity within financial constraints by substituting a snazzy red and silver jacket and blue jeans in place of Ultraman’s traditional space-age inspired look. Ever the postmodernist, Anno is among the founders of GAINAX Co., Ltd., a critically acclaimed animation studio, and co-directed Shin Godzilla, as well as writing the screenplay.

Shinji Higuchi, likewise, cut his teeth on the tokusatsu scene for decades before working on Shin Godzilla. A near-lifelong friend and colleague of Anno’s, Higuchi is also a founding father of GAINAX, and his most celebrated accomplishment within the Japanese special effects scene continues to be his masterful work bringing Japan’s other “Big G” to the big screen in the 1990s in Shusuke Kaneko’s internationally acclaimed Gamera trilogy, from 1995 to 1999. Among other directing credits throughout the years (including Sinking of Japan, Hidden Fortress: The Last Princess, and The Floating Castle), in 2015 Higuchi landed the job of directing a two part live-action Attack on Titan adaptation for Toho, based on the wildly popular manga and anime of the same name (many of the cast from which he brought with him to Shin Godzilla), providing a very natural segue to the job of resurrecting Toho’s Godzilla. Higuchi co-directs with Anno on Shin Godzilla, and also directs the film’s visual effects.

Shin Godzilla features Toho’s first all-digital Godzilla, with relatively few practical and miniature effects employed in bringing the creature and its destruction to life. Godzilla films have historically faced scorn and mockery in the Western world for the unfair perception of featuring “cheap” and “primitive” special effects (in reality, the series’ utilising of practical effects is a creative choice by its filmmakers and not, as often incorrectly assumed, a compromise stemming from lack of budget). Shin Godzilla’s decision to create a digital King of the Monsters is not, however, a move to counter that stigma, and is instead simply a creative decision on the parts of Anno, Higuchi, and Toho themselves. The film’s Godzilla is certainly the most viscerally horrifying ever portrayed on-screen, and audiences should prepare to truly see the monstrous icon as they have never before.

Opting to completely reboot the series devoid of any continuity from previous films (a first in the Japanese series), Anno and Higuchi are allowed the freedom to boldly reinvent one of cinema’s most iconic characters for a new generation of Japanese moviegoers, while also paying respect and homage to the sixty-year legacy that came before them. Outside influences as far-flung as Lucio Fulci’s Zombie Flesh Eaters to The West Wing are discernible in Shin Godzilla, but make no mistake: this is a Godzilla film through and through. As evidenced in the film itself, Anno and Higuchi live and breathe Godzilla: this series and its monster star are as much a part of their DNA as their own blood. Both of these men’s entire careers have been shaped by their lifelong obsession with Godzilla, Gamera, Ultraman, and any and all Japanese monsters, and it is only fitting that Toho eventually saw fit to trust them with the resurrection of Japan’s most famous movie export.

One of the most prominent threads running through Shin Godzilla is the infuriating inefficiency of bureaucracy, and in this regard it is dishearteningly fitting that the film was released in 2016. In a year which saw the Western world face mass disillusionment with current electoral systems and democratic conventions, the scenes of seemingly-endless negotiation and compromise between any and all systems of government in Shin Godzilla take on an all-too-real and somewhat uncomfortable quality in our current global political climate. One almost expects Malcolm Tucker to burst into a scene at any given moment as a voice of impassioned, aggressive reason. Indeed, when a bureaucrat laments the obscene amount of destruction caused by Godzilla in a mere two hour period, Rando Yaguchi (Hiroki Hasegawa) retorts that the government instead had two hours to mount a response, and came up with nothing. As the series always has, the latest Godzilla film uses the appearance of a near-mythical creature to remind of us how disastrous the consequences of petty political squabbles can be in the face of annihilation.

(Note - I’m disappointed this paragraph didn’t make it into the final edit, but I understand why)

Shin Godzilla marks the beginning of a new age for Godzilla, not only as a character and film franchise, but as a cultural icon. In a bleak new world increasingly devoid of reason and compassion, Godzilla returns to prove once again that we merely inhabit this Earth. Anno and Higuchi stress to perhaps not only their audiences, but to the governments and peoples of the world that only international cooperation and the willingness to help those in need will be our salvation. To quote Raymond Burr in the closing monologue of Godzilla 1985: “Nature has a way sometimes of reminding man just how small he really is. She occasionally throws up the terrible offsprings of our pride and carelessness to remind us of how puny we really are in the face of a tornado, an earthquake… or a Godzilla”.

#shin godzilla#glasgow film festival#frightfest#glasgow film theatre#kaiju#godzilla resurgence#toho#hideak anno#shinji higuchi#godzilla#hideaki anno#kaiju eiga#daikaiju#japan#film#japanese cinema#world cinema#toku#tokusatsu#cinema of japan#cinema#my writing

231 notes

·

View notes