#fungal biomass

Text

Unlocking the Potential of Fungal Biomass: A Sustainable Innovation for Insulation

FungalBiomassInInsulation.part1.docx

#art#architecture#civil engineering#construction#insulated#ecofriendly#engineering#global warming#fungal biomass

0 notes

Text

tomorrow is the day i finally take care of my kitchen i swear i promise i hope

#theres more fungal biomass in there than. than my bodyweight i think#theres more trash covered surfaces than uncovered surfaces and that is INCLUDING the floor#m a n

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

also i finished What Moves The Dead today and just

firstly, yeah, t. kingfisher just really isnt my kind of author. dont get me wrong, the prose is delightful and easy to read and its well-written, but the actual set pieces at play here are disappointing and drab and just. boring. i hate to say it but all of the actual elements of the plot were nothing new and nothing exciting, and the answers we got felt like the most boring possible answer. it was easy and fun to read but i just felt bored and disappointed.

secondly, why is all fungal horror zombies? like. fungi is an entire kingdom of life. it has SO much diversity. why is the only fungal horror anyone is writing all reanimation of the dead?

#all the care guide says is 'biomass'#honestly when i say i hate fungal horror i dont. really mean i hate fungal horror.#i mean i hate the fungi = zombies thing that has so far#been the only thing going on within fungal horror#like annihilation does fungal horror SO much better with fungi and its more properly described as bio horror in general!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fungi stores a third of carbon from fossil fuel emissions and could be essential to reaching net zero, new study reveals - phys.org

In a meta-analysis published June 5 in the journal Current Biology, scientists estimate that as much as 13.12 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e) fixed by terrestrial plants is allocated to mycorrhizal fungi annually—roughly equivalent to 36% of yearly global fossil fuel emissions.

Because 70% to 90% of land plants form symbiotic relationships with mycorrhizal fungi, researchers have long surmised that there must be a large amount of carbon moving into the soil through their networks.[...]

Mycorrhizal fungi transfer mineral nutrients to and obtain carbon from their plant partners. These bi-directional exchanges are made possible by associations between fungal mycelium, the thread-like filamentous networks that make up the bulk of fungal biomass, and plant roots. Once transported underground, carbon is used by mycorrhizal fungi to grow a more extensive mycelium, helping them to explore the soil. It is also bound up in soil by the sticky compounds exuded by the fungi and can remain underground in the form of fungal necromass, which functions as a structural scaffold for soils.

The scientists know that carbon is flowing through fungi, but how long it stays there remains unclear. "A major gap in our knowledge is the permanence of carbon within mycorrhizal structures. We do know that it is a flux, with some being retained in mycorrhizal structures while the fungus lives, and even after it dies," says Hawkins. "Some will be decomposed into small carbon molecules and from there either bind to particles in the soil or even be reused by plants. And certainly, some carbon will be lost as carbon dioxide gas during respiration by other microbes or the fungus itself."[...]

"Many human activities destroy underground ecosystems. Besides limiting the destruction, we need to radically increase the rate of research,"

5 Jun 23

680 notes

·

View notes

Text

Categorizing the Uncategorizable

(or, the divine is stored in the infinite mystery of life on earth)

I swear this is about lichen genomics but it’s not not about gender

Recently I was asked “What do you think of species described only from DNA?” That is to say, species not morphologically distinguishable from others but when tested genetically, show up with results different enough that some people have decided they count as a different entity.

Over and over again in my (short) career as a biologist I keep running across the question “What is a species, really?” It doesn’t seem like something that would be the subject of ongoing debate. We should be able to tell the difference between different types of creatures, right? Even if they look similar, if they can’t breed and produce fertile offspring, they are not considered to be the same species. This works for most vertebrates, as far as I know, but a brief glance at botany makes everything infinitely more complicated. Different species of plants are absolutely capable of interbreeding and producing fertile hybrids (that’s how we get so many fun cultivars to grow in our gardens). And by the time one considers lichens, the concept of “species” is more of a vague suggestion, or a shorthand we’ve all agreed to use while acknowledging its drawbacks.

Lichens are always already at least two species – a fungus and a photosynthetic partner (green algae or cyanobacteria) – combined into one “body” that looks unlike either partner would if grown separately. They are recognizable entities, a whole that is more than the sum of its parts, but the parts are always visible in cross section, or in the genomic data. And this is without even mentioning the myriad species of other fungi and bacteria simmering in the lichenological stew. The lichenological community decided to use the Latin name of the fungal component to refer to the whole lichen, since the fungus makes up the majority of the biomass and seemed to determine the morphology while the photosynthetic partner was more or less along for the ride. The same species of alga is also known to partner with different fungi to form different lichens, which was taken as evidence of its relative non-selectiveness versus the fungal partner’s specificity (something that has more recently been called into question). Regardless of one’s stance on the fungi-centric model, we can all agree that the idea that one genome=one species does not apply to lichens.

So why do we call lichens “species” anyway? Well, what else would we call them? They are distinct entities that live and reproduce and play particular roles in an ecosystem. They can be identified by their distinctive morphological features. And when so much work in biology relies upon knowing “what lives where”, we need to have a name for the “what”. So, we’ve given imperfect names to capture some aspect of our infinitely interconnected world. This is something we need to do, for the sake of communication.

But just like words can never quite capture elusive and complex feelings, grouping a set of organisms together and calling them a Latin binomial will never quite express the reality. We are only human, after all, and as much as we learn about the world around us, we are limited in the scope of what we can understand. I don’t think we will ever unravel every mystery in the natural world, and that’s not a bad thing. The more we learn, the more questions we have. What I’m getting at is that we can never have an omniscient view of every single biological interaction ever. We research and study and we get an approximation. It might be a very good approximation that answers our questions and contributes to our body of knowledge, but it is still an approximation impacted by the limits of our perception and our implicit biases.

The way I see it, using our human perspective to apply categories to the natural world is always a functional endeavor. We do not name lichens because we think this is what the lichen would call itself, or even what god would call the lichen. We name them because we are interested in them and we need something to call them when we talk to other humans. Endangered species lists are just that – lists of species. We wouldn’t be able to protect rare lichens without assigning them a species and putting them on the list. There will always be exceptions, and edges, and individuals that don’t quite fit. Evolution is always happening; we see populations that are not quite different enough to be their own species, but we can tell that one day, thousands or millions of years from now, maybe they will be. What do we name these? Perhaps a subspecies or a variety, perhaps not. The important thing is not that we’ve discovered the One Truth of the Universe, but that we are close enough to accomplish what we need to accomplish.

But are DNA sequences enough to define a species? I think not. We must consider again not what a species is, but why we describe species. We do not describe species for the sake of making up a name for a slightly different DNA sequence, we do it to categorize an entity we are interested in. If two lichens look the same, contain the same chemicals, and fill the same ecological niche, are they really different? And if they are, are they different enough to matter?

This is not an indictment of the act of naming species, or a call to stop trying to study and understand what appears unknown and unknowable. It is simply an encouragement to think more critically about categories and why we categorize. Why is it important to tell these two things apart? In what context would it become important? What would it look like to treat them the same? How much more can we learn from thinking consciously and openmindedly about what we mean when we say “this is a species”?

#lichen#lichens#lichenology#lichensplaining#science#biology#species concept#species#evolution#taxonomy#genomics#gender

233 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stellarangia elegantissima

Namib sun, yellow star

It is HOT here in Europe today, so I’ve been laying around in my underwear all day doing nothing because I am a large mammal and not adapted to do things in this kind of weather. Really wishing I was a desert lichen right now like S. elegantissima so I could thrive in this shit. This absolutely stunning lichen is one of many species of lichen that form the dominant biomass of the Namib desert in Namibia. That bright red-orange color comes from special pigments in the thallus that protect the algae and fungal hyphae within. And there are a lot of cool biochemical processes within that help the lichen adapt to extreme heat and desiccation. God I wish that were me.

images: source | source

#lichen#lichens#lichenology#lichenologist#lichenized fungus#fungus#fungi#mycology#ecology#biology#botany#bryology#systematics#taxonomy#adaptation#life science#environmental science#natural science#Namib desert#Namibia#Stellarangia elegantissima#Stellarangia#I'm lichen it#lichen a day#daily lichen post#nature#the natural world#I love lichens#lichen subscribe

304 notes

·

View notes

Text

A leviathan evoking deer, sauropods and stegosaurs. Felt a terrestrial take could be interesting.

-

BISANOLICH

Title - Fungal drake wyvern

Monster class - Leviathan

Known locales - Savannah, occasional forays to grassland and forest

Element/ailment - Dragon + Effluvium

Elemental weakness - Fire (3), Dragon (2), Ice (1), Water (1), Thunder (1) Ailment weakness - Poison (2), Stun (1), Paralysis (1), Sleep (1), Blast (1)

Bisanolich is a unique leviathan adapted to a terrestrial lifestyle in desert environments, predominantly taking control of grasslands and occasionally migrating to forest regions. Past a lack of aquatic features, it is distinguished by its enormous antlers and thagomisers, alongside a strange fungus growing upon its back. With its pillar-like legs, Bisanolich is appropriately slow and sturdy, but the reflexes on swinging its neck and tail cannot be underestimated.

Bisanolich is a herbivore that feeds on myriad plant and tree species, the seeds and saplings of which it nurtures with a unique mutalistic fungus. This fungus is feed on nutrients from the leviathan and has chunks of its biomass jostled loss to serve as a fertilizer for flora that Bisanolich prefers. In this way, Bisanolich can be a boon to its environment, cultivating vast 'farms', but unfortunately this leads the monster to be terribly aggressive in defending its turf. However large or small, other creatures are not tolerated and Bisanolich will lash out at anything that comes close to its farm. Humans are just as quickly expulsed from its territory, so field researchers must keep a safe distance and avoid its attention. Bisanolich is only relatively safe to approach if it is migrating or otherwise away from its farm, where it doesn't feel so protective.

The success of Bisanolich's farming is as much due to its reservoir of dragon energy as the use of its fungus. Fuelling its power on dragonfell berry and other high-energy plant species, Bisanolich channels dragon energy through its antlers and thagomisers. It discharges it in powerful bursts that tears the ground, making for dangerous area-of-effect attacks. In addition, charging dragon energy through the spines lining its body triggers a reaction in the mutalistic fungus, causing it to release choking effluviual gases. These spores are believed to be related to a variant utilised by the elder dragon Vaal Hazak, but no such link has been proven. Combining its formidable size and strength with these ailments, Bisanolich is a force to be reckoned with.

Bisanolich is sexually dimorphic; only the males produce antlers. The males with the largest farms attract more females, and also rivals. Competition is fierce and males have been known to kill each other for control of the best territory. After mating with several females, a dominant male will shed his antlers and leave for new pastures, altruistically leaving his farm for the females to feed their young. During these times of migrations, males have been spotted in other locales, where they will rebuild their power and antlers. The potential for them spreading the fungus or introducing invasive plant species is a concern to the Guild, so hunting these males is often necessary.

A formidable apex monster (Low Rank - 5, High/Master Rank - 4), Bisanolich is well deserved of its reputation as a mighty challenge. Hunters must constantly be aware of how its dragon energy affects the fungus it releases and use fire weapons to nullify their influence. Such a heavy monster is vulnerable to pitfall traps, and targeting the spines along its body can disrupt its dragon charge.

Wherever it wanders, Bisanolich's size and ailments usually repels any predators. Though occasionally harassed by the likes of Anjanath, or competing for plant space against Diablos and Monoblos, Bisanolich knows little fear from other monsters. It has even been known to successfully repel attacks from the elder dragon Karakagau, who finds its resilience to paralysis and sheer strength hard to overcome.

-

Thank you for reading and take care.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“So, really think about this one for a second- How many people does the average ghoul eat? When you stop and do the math, you realize that it can’t really be that many, right? Like less than one percent of any given person. They can infect people, sure, kill em’ slowburn, but if it’s one ghoul attacking one living person, the odds are good the person’ll get away with just a couple bites taken out, or turn the tables outright. And if they’re taking someone down through sheer force in numbers, again, they probably only get a couple bites in the feeding frenzy.

So you’d be forgiven for not knowing. About the chimaera. About what happens one of them is left alone to eat a whole human person. The first couple we created by accident under laboratory conditions. We were feeding captured ghouls, uh, you know, we were feeding them medical cadavers. That we had. And we were trying, uh, we were trying to see if they had any genuine caloric needs, or if they’re just eating to eat, and, uh. Neither. It turns out, they’re eating to grow.

Nothing they eat leaves their body. Consumed biomass becomes part of their biomass. They get stronger, tougher, smarter. A diffuse nervous system, auxiliary brains sprouting in their abdomen like fungal growths. We were able to purge the ones we made on accident. They were already in containment, we fucked them up pretty bad when we were capturing them, we had incendiary failsafes, they barely cracked the glass. But I’m getting worried that we’re gonna start seeing natural chimaera in the exclusion zone soon, born from a thousand cuts- because you don’t need to eat a whole person all at once for this to work, that’s just what’s necessary to make the process visible. Lucky fucker just need to pull a mouthful off twenty morons, and it’s off to the goddamn races.”

#my art#my writing#zombie#zombies#gotta start tagging stuff from this setting#eventually#untitled zombie project

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

So you've heard of the fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, which famously parasitizes ants and turns them into "zombies," controlling their movements? Well a research team wanted to know how that works so they looked at the structure of the fungus in ants right before it kills them.

They found that, "As much as 40 per cent of the biomass of an infected ant is fungus. Hyphae [fungal threads] wind through their body cavities, from heads to legs, enmesh their muscle fibres and coordinate their activity via an interconnected mycelial network. However, in the ants' brains, the fungus is conspicuous by its absence... The researchers suspect that the fungus is able to puppeteer the ants' movements by secreting chemicals that act on their muscles and central neverous system." (Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake, illustrated edition, page 123.)

So instead of turning ants into mindless zombies, the fungus leaves their brains alone and just takes over control of their limbs, leaving the ants fully aware (to whatever extent ants are self-aware) but unable to control their bodies.

That is SO MUCH WORSE than zombies! Imagine The Last of Us but the infected still have their thoughts, personalities, and desires intact even as the fungus forces them to attack and kill their friends and family. Imagine having to protect yourself against them. Someone please write this so I can read it.

#body horror#fungus#mushrooms#ants#entomology#horror#zombies#the last of us#entangled life#merlin sheldrake

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Tell me about your trees!

Oof this has been sitting in my inbox for a while. Sorry for the delay, wanted to make sure I had the time to give yall a real banger.

Back in my hometown of Fortree there is a subspecies of nincada called Branchcutter Nincada. They will crawl their little asses up into the tree canopy to harvest fresh branches from trees. And they are INCREDIBLY efficient at it - one colony of branchcutters can harvest anywhere between 50-70% of a tree's branches in an hour. They inject a special chemical into the branch that causes it to stiffen and crack, making it much easier to hack through. They also stay on the branch as it is falling out of the tree, clinging desperately to it until they hit the ground. Very silly, but they can't really fly so I guess it's the fastest way to the ground.

Once they have their branches the colony will start to head home all together. This helps protect them from predators, but man it is a sight to see. They carry their branches overhead, so you can't really see the buggies. You just see a HUGE swath of the forest apparently moving on its own. Branches crawling along the ground like they've gained sentience. Quite a lot of folklore around that phenomena, as you can probably guess.

Once the nincada have brought their branches home they use them to set up a huge, underground fungal farm. And they are incredible farmers, they fertilize their gardens, clear out the dying and decayed sections, and produce a bacterium that helps clear out unwanted mold, and has the added benefit of protecting the nincada from molds as well. They are so sensitive to their fungal garden's needs that they can sense how the fungi is responding to certain food and change things up accordingly. The fungi they grow they then feed to their larva, who feed on it until they grow big enough to gather their own food (typically tree sap).

Branchcutter Nincada are a really incredible species. REALLY harmful to the trees though, on account of all the branch cutting. Left unattended, they can clear something like 20% of an ENTIRE forest's biomass in a day, and have underground nests spanning over a kilometer in length. They are extremely important to the ecosystem, but the Fortree rangers have a hell of a time monitoring and adjusting their populations, especially since nincada don't tend to be a particularly popular pick for trainers, so we can't really rely on trainers to do the one thing their useful for (catching pokemon).

Quick aside, to bash the pokemon league of Hoenn. I swear, if the league was sooooo insistent on putting a gym in a city that didn't want it the least they could have done was try and find a way to make it work with the local community instead of directly against it. Having a grass or a psychic gym there to encourage trainers to catch some of those buggies would have been the one non-awful thing the league could have done. But they aren't interested in the communities they stick on the gym circuit, they've made that much PERFECTLY clear.

Bleh. Anyway. Branchcutter Nincada. Efficient pest, incredible farmers, very cool little bastards.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

SpecBio concept #5: Plantworld

A planet resembling Earth in its late Archean state (higher temperature, no free oxygen, dense atmosphere, extensive salty oceans, thick coat of carbon dioxide), perhaps more tectonically stable, extensively seeded with Earth plants and bacteria. Not a single animal or fungal species is brought.

The first green settlers struggle to get a hold on the barren continents, in absence of fungi to erode bare rock and worms to aerate the ground. But some ground is more hospital than other, the first layer of debris provides soil for the survivors, and eventually plant life starts to grow properly.

For many millions of years the plants thrive, thanks to the abundance of carbon and water, the higher temperatures, and the lack of oxygen to interfere with carbon fixation; but eventually oxygen starts piling in the atmosphere, gigatons of carbon are locked into wood and buried debris (to be released in pulses only when wildfires burn out uncontrollably), and the diminished greenhouse effects starts to cool down the planet sensibly. The forests start to shrink.

There’s an obvious niche to be exploited there. Parasite plants without chlorophyll exist on Earth right now, such as the very unfortunately named broomrape. They’ve always thrived on Plantworld in many lineages, with the bounty of hosts to exploit, but now they can do one better: they find out how to secrete acids and enzymes to break apart cellulose, much like fungi did on a forgotten planet, and start consuming the vast dead biomass.

The decomposer plants scatter their pollen and seeds to the wind (no animal disperser to exploit), gliding away on wing-blades like maple seeds, but why stop there? If they gather enough energy, they can manipulate osmotic pressure inside the seeds to move the blades, until they can flap them like wings. This consumes enormous amounts of sugar and oxygen: each plant can afford very few seeds. The strands of turgid cells become analogues of muscles, and soon Planetworld’s forests are abuzz with little flying seeds, flying as far as possible from the mother plant to avoid competing against their own kin.

Each incremental improvement to fitness suggests others. If you sharpen your chemical senses, you could detect the places were there is fewest competition... if you steal back some photosynthetic pigments from your prey (which are but light detectors, after all) you can repurpose them into crude eyes to look for better ground... if you can move your wing-flaps, you can move them on the ground to place yourself in a better germinating position.

Absorbing matter through roots is agonizingly slow for these increasingly energic parasites. It would be much quicker to take food in bulk. The flying seeds secrete powerful saliva-like enzymes to degrade the matter on which they germinate; they use their osmotic muscles to grind shell-plates against each other like tiny jaws; they develop internal specialized glands... And eventually they discard the roots at all, which have lost their use. Why bother growing into a plant form? You can just stay a flying seed all your life, and sprout your flowers directly there. Actually, now that you’re so nimble, you can just seek out your mates directly.

Half a billion year later, Plantworld has a rich biosphere full of animal life; swift-footed grazers and silent ambush predators, swarming minute plankton and giants feeding on them by the millions, industrious hive-builders and devious endoparasites; and perhaps some creature with inquisitive brains and dexterous hands who is in for a big surprise or two when they finally chart the history of life on their world.

EDIT 26-11-23: used to be #4, but then I remembered the actual fourth concept

SpecBio concept #4 (a biosphere feeding on sound, inspired by @cromulentenough)

SpecBio concept #3 (children falling from the “sky”)

SpecBio concept #2 (liquid brain, chemical memory)

SpecBio concept #1 (double silicate biosphere, one hot, one cold)

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

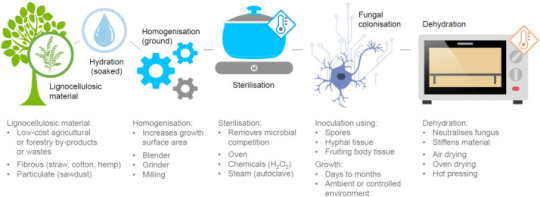

Copy of Can Fungal Biomass Make Construction More Sustainable?

The construction industry is an ever-growing problem when it comes down to sustainability. The population continues to grow and this requires more and more buildings to accommodate people's lives. More and more materials are required to construct buildings, and so naturally, more and more carbon is emitted into our atmosphere from these construction processes. But we can't just put a pause on population growth, or ban new buildings from being built, and we certainly can't just pretend this problem doesn't exist either.

How about focusing on improving the sustainability of the materials that are used in construction? What alternatives might there be to ensure more sustainable construction processes are used?

… that's where fungal biomass comes in.

Fungal Biomass... what is that exactly?

Biomass is a renewable material that's made from plants and animals. It can be used as energy or turned into useful materials. With fungal biomass, agricultural waste and other low-grade discarded materials (stalks, straw, sawdust, etc.) are used as substrates which are introduced to a fungus to create a material bound together by mycelium.

To create the mycelium material, a process must be followed to ensure good performance of the material.

For an explanation of this process check here, and refer to section 2.

Here are some important material properties of mycelium materials:

Handles tensile loading well

Has some compressive loading capabilities

Highly flame resistant

It has a very low thermal conductivity

Very high moisture uptake

Okay, sounds great! But what can the mycelium material be used for?

Structural application:

Mycelium has shown an ability to handle tensile loading well, however it has a low ability to withstand compressive loads, meaning the material is weak compared to traditional construction materials. Since structural materials are required to transfer heavy loads, this material wouldn't be effective and therefore is not being considered for structural use.

Thermal insulation:

Mycelium composite is a low-density material, which makes it an excellent insulator as low-density materials conduct heat slower. It performs similarly to other traditional insulators such as glass wool, extruded polystyrene, sheep wool etc.

Water absorption:

Moisture content will also have an impact on the thermal conduction. If mycelium insulation is exposed to moisture for more than a few hours, it can absorb it quickly and in large amounts. Luckily a large increase in moisture content results in just a small increase in heat conductivity. Check here for more(section 3.0).

Other risks resulting from moisture absorbency has delayed the journey of this type of insulation making it into people's homes, but hopefully solutions can be found as this type of insulation would make some amazing competition.

Fire safety:

Mycelium composite out-performs many conventional insulation materials. A mycelium composite can even perform so well under exposure to fire that its only competitor is phenolic formalhyde resin foams.

"Mycelium has been found to possess certain flame-retardant properties (e.g. high char residue and release of water vapour)"

More on that quote here.

Since the material would mainly char rather than burn, it would take longer for flames to travel through a cavity if it were filled with it. The material is also non-toxic therefore it is much safer than other insulators.

Read here for more information on thermal degradation and fire reaction properties of mycelium composites.

Why is this new material so important?

Mycelium material is completely biodegradable and renewable, it has a perfect life cycle and its cheap, what's more to love?

Discovering uses for fungal biomass and applying them is super important for the construction industry as it hopefully will kickstart a greater interest in building with sustainable materials. The current applications of this product are limited; however this material makes promise for the future of sustainability in construction.

Take a look at some videos and other helpful sources if you're still interested!

Engineered mycelium composite construction materials from fungal biorefineries: a critical review

Is Mycelium Fungus the Plastic of the Future?

Can Mycelium Fungus replace Concrete & Plastic?

Biohm

Ecovative

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi Maggie!! Congrats on 1500, this is HUGE!

I'm here for the rolls! Let's see what the dice gods have in store today:

Of course gotta ask for Percy and Vax'ildan, both HCs?

And then maybe two rolls of the d8??

Congrats again! And thank you!! I hope you have a lovely rest of your day. ☺️💕

Thank you so much! You're always a delight to see in my notes, reminds me to get a little chaotic. Keep em guessing >:D

Miss Thing is really helping out with rolling dice:

Let's say the blueish with silver is Percy and the edgy is for Vax:

2.Angst for Percy

God, what rock haven't I turned over with him? ... ah: I think he'd initially have a lot of difficulty handling when the children Not as babies, though baby howls are practically designed to cause distress. No, it's when they're older: teenagers sobbing over heartbreak, or raising their voice to talk back, or whimpering after a hunting accident. Even a laugh that turns into a shriek of delight can be too close on some days. (The screams from the dungeon, from the cells next door, from across the dining room, from his own throat. And just enough of Vex (and thys Vax) in the tones to turn them from memory to nightmare)

3.Fluff for Vax

I fucking adore Vax cutting Kiki's hair after the Thordak fight!!! so!! much!! I HC that Vax is the main hair guy for VM during their early days - he's the most at ease with daggers and knives, and likely already has experience tending to his and Vex's hair on the road (potentially learned from Elaina giving them haircuts at home). Of course Percy will not let him touch a hair, and Keyleth never really wants a cut until then - but I like him sprucing up Scanlan before a bar crawl, cutting burrs off Trinket, keeping Pike's hair from getting too long and messing with her armor, making sure Grog didn't miss a spot shaving his head (he's never allowed to do it again after shaving half the beard tho 🤣). And then following Kiki's initial cut he cleans it up a bit in the days after, less of a necessary job and more getting it to her liking.

This but ~magic~

I think more druid magic should feature plant communication and mycorrhizal networks! They already feel so close to magic, it's fascinating. Waterbending plants and Caduceus' fungal-flavored healing are favorites of mine, but just consider: a lesser version of Transport via Plants limited to plants who are, if distantly, connected to the sane network, or specific plants used for Grasping Vines and other such spells to cause photosensitive blisters, or nasty thorns, or just fucking trigger allergies.

Hot take or tea

I don't care how many degrees someone has, if they start spouting 'oh we can exterminate all of X species I don't like itd be fine'. Even in a hypothetical magic world where you can bamf all mosquitoes out of existence, a huge host of insectivores are now without a huge amount of biomass to eat and larger animals' movements (to avoid mosquitoes) are impacted, resulting in changes in browsing/hunting/use of that environment. In a more realistic scenario, there's huge financial and manpower costs to factor in, as well as problems of specificity. We're struggling to deal with the invasive, 100% destructive species in many ecosystems (ignoring for this those that are actually not entirely detrimental) - how do you expect we'll erradicate X pest you don't want? It's also just so arrogant to assume we know everything and know what's best- I think of that parasite driveb to extinction because their endangered hosts were given treatments to remove them.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tagged by @tathrin

3 Ships: Thranduil x Celeborn, Legolas x Gimli, Irmo x Estë

First ever ship: Nicolas de Lenfent x Lestat de Lioncourt

Last song:

youtube

Last movie: To Wong Fu, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar

Currently reading: Thermal Degradation and Fire Properties of Fungal Mycelium and Mycelium - Biomass Composite Materials

Currently watching: A download bar.

Currently consuming: ramen with a generous squirt of ghost pepper sauce.

Craving: Pizza

Tagging: Anyone who wants to use me as an excuse to fill this out. 💚

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

You cant be both lesbian and non binary considering one of those doesn’t exist

Mycelium is a root-like structure of a fungus consisting of a mass of branching, thread-like hyphae. Fungal colonies composed of mycelium are found in and on soil and many other substrates. A typical single spore germinates into a monokaryotic mycelium, which cannot reproduce sexually; when two compatible monokaryotic mycelia join and form a dikaryotic mycelium, that mycelium may form fruiting bodies such as mushrooms. A mycelium may be minute, forming a colony that is too small to see, or may grow to span thousands of acres as in Armillaria.

Through the mycelium, a fungus absorbs nutrients from its environment. It does this in a two-stage process. First, the hyphae secrete enzymes onto or into the food source, which break down biological polymers into smaller units such as monomers. These monomers are then absorbed into the mycelium by facilitated diffusion and active transport.

Mycelia are vital in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems for their role in the decomposition of plant material. They contribute to the organic fraction of soil, and their growth releases carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere (see carbon cycle). Ectomycorrhizal extramatrical mycelium, as well as the mycelium of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, increase the efficiency of water and nutrient absorption of most plants and confers resistance to some plant pathogens. Mycelium is an important food source for many soil invertebrates. They are vital to agriculture and are important to almost all species of plants many species co-evolving with the fungi. Mycelium is a primary factor in a plant's health, nutrient intake, and growth, with mycelium being a major factor to plant fitness.

Networks of mycelia can transport water and spikes of electrical potential.

"Mycelium", like "fungus", can be considered a mass noun, a word that can be either singular or plural. The term "mycelia", though, like "fungi", is often used as the preferred plural form.

Sclerotia are compact or hard masses of mycelium.

One of the primary roles of fungi in an ecosystem is to decompose organic compounds. Petroleum products and some pesticides (typical soil contaminants) are organic molecules (i.e., they are built on a carbon structure), and thereby show a potential carbon source for fungi. Hence, fungi have the potential to eradicate such pollutants from their environment unless the chemicals prove toxic to the fungus. This biological degradation is a process known as bioremediation.

Mycelial mats have been suggested as having potential as biological filters, removing chemicals and microorganisms from soil and water. The use of fungal mycelium to accomplish this has been termed mycofiltration.

Knowledge of the relationship between mycorrhizal fungi and plants suggests new ways to improve crop yields.

When spread on logging roads, mycelium can act as a binder, holding disturbed new soil in place preventing washouts until woody plants can establish roots.

Alternatives to polystyrene and plastic packaging can be produced by growing mycelium in agricultural waste.

Mycelium has also been used as a material in furniture, bricks, and artificial leather.

Fungi are essential for converting biomass into compost, as they decompose feedstock components such as lignin, which many other composting microorganisms cannot. Turning a backyard compost pile will commonly expose visible networks of mycelia that have formed on the decaying organic material within. Compost is an essential soil amendment and fertilizer for organic farming and gardening. Composting can divert a substantial fraction of municipal solid waste from landfills.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am reminded once more of how resistant the underland remains to our usual forms of seeing; how it still hides so much from us, even in our age of hyper-visibility and ultra-scrutiny. Just a few inches of soil is enough to keep startling secrets, hold astonishing cargo: an eighth of the world’s total biomass comprises bacteria that live below ground, and a further quarter is of fungal origin.

- Robert Macfarlane, Underland: A Deep Time journey.

0 notes