#folklore and mythology

Text

thinking about how romanians described women as a light brighter than the sun in folk tales and legends, shining so blindly one couldn't even look at it. a presence so etheral, a being so mythical, magical, that not even the SUN, a real star in the sky very much worshipped all over the globe, can't compare to her, a woman.

#romanisme#women#sun#folk tales#folklore and mythology#folklore#romania#in romania#romanian folklore#romanian legends#romanian literature#the sun#woman#light academia#dark academia#romantic academia#etheral

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I’m writing a retelling of Arthurian legend because that’s just the type of gay person I am. Alongside that I decided that the follow up would be a Robin Hood retelling and since rounding things up as a trilogy is always good today I decided the final book would be a retelling of Cú Chulainn, in of itself, not so bad. Im enjoying it and think I can write something really interesting with him however- I do not speak any Gaelic language let alone old irish, I know a few words and names and their pronunciations but I by no means speak any of those languages. So for every single character I need to write myself out a pronunciation guide to make sure I pronounce every right- however I also quickly learned that the regional dialects can be quite different for some names- for instance King Conchobar which I’ve seen at least four pronunciations for, I eventually settled on con-uh-cur but that doesn’t mean I’m satisfied lol

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Under the big twisted beech tree 🌳🍂

In the wild of the rust-coloured valley, between rocky peaks and needles made of the hardest stone, there laid her kingdom of everlasting Autumn days 🍂

He's a series of photos I took back in October in one of the wildest places of my beloved Auvergne, that always reminds me of Middle-Earth, especially when it's painted in autumn colours. The vibe I wanted for these photos was something wild and ancient, that could bring the old pagan ways and Norse mythology to mind, with a fantasy twist.

I'm wearing a dress from CottonCandyWear (Etsy) and a handmade leather bag made by echoppe_du_loup (on Instagram)

You can find more photos on my Instagram page (@january-child) 🍂

#norse pagan#pagan community#autumn#auvergne#viking aesthetic#norse aesthetic#folklore and mythology#fantasycore#middle earth#autumn core#support small creators#shop small#cottagecore#fantasy landscape#medieval fantasy#Spotify

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's a new illustration! The Pùca is a shape-shifter and trickster from Scottish folklore

#art#digital art#digital drawing#drawing#illustration#artwork#digital illustration#adhd artist#artist#folklore art#folklore and mythology#scottish folklore#irish folklore#faery folk#faeires#faery faith#fae folk#faery folklore#púca#pooka#folklore illustration

49 notes

·

View notes

Link

As a boy I believed so implicitly in the Loch Ness monster that I made my dad drive us all the way from Southampton to Scotland to see it. The night before, in a dream, I saw its shape snaking through the marshes at the lake’s edge. I was terrified.

The next day the great grey waters remained unbroken by a serpentine neck, but that did nothing to dispel my belief. I filled an empty bottle with Loch Ness water, took it home to put in the cupboard under the stairs, and waited for tiny plesiosaurs to hatch out.

Humankind cannot bear very much reality, as TS Eliot said, so we reinvent the monsters already there in our heads. This week sees the screening of the TV series based on Sarah Perry’s novel, The Essex Serpent, a Victorian resurrection of the legend of a chimeric, watery beast said to emerge from the marshes in search of human prey. Perry’s story draws on the idea that something strange might exist in the space between us and the infinite – the “thin places” of Celtic myth.

In fact, our notions of residual monsters may have much to do with the way Celtic people were driven to the edges of the British Isles, to bays, lochs and islands, which seemed to retain such beliefs as gestures of defiance. In the 1940s a BBC radio producer, David Thomson, went to Scotland and Ireland in search of selkies, myths of shape-shifting seal people. He treated them not as tall tales, but as cultural artefacts, believing that the stories he recorded were “the last vestiges of pagan belief, before the onset of the nuclear world”.

In 1937 a remarkable survey of schools in Ireland had sought to catalogue such folklore. It was an uncanny version of Mass Observation, an assertion of a new republican state. “Is there a story told in your district of a serpent or large animal which lives in a certain lake or river there?” children were asked. “Are water-horses or water-bulls spoken of? Are stories told of strange animals met by night on roads?” One boy said that water-horses emerged from Drumcor Lough at night to feed, then returned to the lough and turned into animals like eels. “Customs and beliefs in a conservative country like ours,” the survey concluded, “come from the Bronze Age as well as from the early Christian period.”

Little wonder that the first reports of a monster in Loch Ness came from the Irish missionary St Columba, who ordered the beast to desist from attacking a swimmer in 564 AD.

In the 1930s, reports of Nessie poured in, spurred on by an increase in tourism and access to the loch’s shores, but also by the Great Depression in which escapism was a reaction to social and economic distress. Even Virginia Woolf was compelled to record a visit to the loch in 1938 when she met a charming couple “who were in touch with the Monster. They had seen him. He is like several broken telegraph posts and swims at immense speed. He has no head. He is constantly seen.”

He still is. Last week a couple staying in Scotland posted a video said to show a 5m-long creature with a fin swimming in the loch. That story came as a kind of antidote to terrible news of the war in Ukraine. In the 1970s sea monsters, yetis and aliens also appeared in a threatened world, whose wildernesses were rapidly shrinking and whose human lives were being overtaken by technology.

In the great extinction, we were left only with the dragons of our unconscious, as Carl Jung said. Perry’s novel has its counterpart in Iris Murdoch’s The Sea, The Sea of 1978, in which a theatre director retires to a rocky shore where he witnesses, in the broad light of day, a sea serpent emerging malevolently from the waves. “I could see the sky through its coils,” he says, horrified. Murdoch, born in Dublin, had a fascination for the uncanny and a malignancy in nature, a sensibility evident in the folk horror films of the time; a psychosexual terror expressed in the juxstaposition of flowerprint crinolines and cryptozoological creatures.

The Victorians had an obsession with sea serpents; it was the dark side to their moral certainty. The characters in The Essex Serpent declare the coming of the beast to be a punishment for their sins, or a symptom of their times, while the main character, Cora Seaborne, believes it to be a surviving dinosaur. Darwin’s theories had thrown up such uncertainties; and while the poet Matthew Arnold wrote of the “melancholy, long, withdrawing roar” of the sea of faith, newspapers carried serious sea monster reports from around the empire. Most celebrated of all was the creature seen in the South Atlantic in 1848 by the crew of HMS Daedalus. “An enormous serpent, with head and shoulders kept four feet constantly above the surface of the sea” seen in the presence of officers of Her Majesty’s Royal Navy gave the beast a delicious credibility.

In our own troubled times the sea retains its power to contain the unknown. Jung saw the sea as the repository of our collective unconscious; Jean-Paul Sartre thought its thin green film was designed to deceive people. Scientists estimate we have still identified only a third of the species in the deep ocean.

Whales and basking sharks swimming just beneath the surface can look like many-humped beasts, and the Daedalus monster is now believed to have been a sei whale, an almost eelish mammal, albeit 20m long. And in a nod to Freudian phallic symbolism, other sea serpent sightings have been attributed to whales rolling on their backs and extruding their prodigious penises.

But I decline to yield entirely to such earthy rationality. A respected whale scientist once told me his colleague had seen a large unidentified serpentine animal at sea, almost the length of the ship he was on. So long as those reports keep coming in, I’ll keep the faith. That bottle is still under our stairs.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is the meaning of Hıdırellez for Turkic People?

HistoryTraditionsSignificanceConclusion Video: The UNESCO Cultural Heritage of Hıdırellez!You may also like

Hıdırellez, also known as Hıdrellez or Hıdrellez Bayramı, is an ancient spring festival celebrated in Turkic states, Iran, and some Balkan states. This festival is observed on May 5 or 6 every year and is regarded as a time of renewal and rebirth. In this article, we will explore the…

View On WordPress

#Celebrations and rituals#Central Asian culture#Cross-cultural exchange#Cultural significance#Ethnic identity#Festivals and traditions#Folklore and mythology#History and heritage#Hıdırellez#Turkic culture

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Happens in the Fog

It is finally upon us! My fic from this year’s @batfam-big-bang!

It's been a joy to write (and mod too) and I've honestly had just the best time despite everything else that's been going on.

Massive thanks to my brilliant betas @your-worst-knightmare, @xvivon, and @theogygiaisland you were an absolute blast to work with (though if I ever wake up to 678 suggested edits again I will commit atrocities) and my wonderfully talented artists @feral-anthropologist, Jacket and @houser-of-stories who are just...insanely awesome, love you all so much.

I highly recommend reading on AO3, just because the AO3 version has linked footnotes with more info about various things and I’m proud of that, but the main text is below.

Find it on AO3 here

Summary: When Damian hears a local legend, he decides he simply must find the Fen Tiger for himself. But it’s a dangerous world out there in the fens, and bonding with Tim may have to wait when they have ghosts and demons, ditches and fog to survive.

(aka. The closest I will ever come to doxxing myself via fic)

Word Count: 8991 (one shot)

Trigger Warnings: near-death experience via falling in a ditch, supernatural elements (mostly fog, various descriptions of demons/effects thereof, wisps, spectral animals etc.)

The cock had not yet crowed, and Damian couldn’t see.

Somewhere on the floor was his shirt– which he needed to put on– and somewhere also on the floor was Timothy’s. Which he did not want to put on. And somewhere else on the floor was Timothy himself, who had fallen out of bed at some point in the night and not deigned to get up. Timothy would most certainly not appreciate being woken up before the sun.

This was Damian’s dilemma: to get up and get dressed himself and risk a clothing mishap, or to wake Timothy so he could light a lamp for them, thus avoiding any cases of mistaken ownership, but earning Timothy’s ire just the same. Damian did not consider not getting up as an option. Not today, of all days.

He was going to have to risk a clothing mishap then. The sun was, slowly, giving up its slumber, and the grey light was just enough for Damian to see by. He could establish which shirt and breeches were his own without assistance. The wardrobe was where Pennyworth had placed his jacket for safekeeping but Damian didn’t need Pennyworth’s help dressing or looking after his clothes. He was not an infant in need of coddling.

Timothy let out another sputtering snore, and Damian scoffed at the sound. Imbecile. The noise did, however, cause him to look up and to the right, which just so happened to be where his jacket hung.

The buttons on his shirt were much trickier than Pennyworth’s sure and nimble fingers made them seem, and the cravat was harder still. But Damian was nothing if not a quick learner and figured it out without asking anyone for assistance. He ran his hands down the lapels of his green coat, revelling at the feel of the intricate, twisting embroidery, and searching for imperfections before declaring it suitable. He turned to Timothy.

Timothy was not his responsibility.

Timothy was still asleep.

It was rapidly becoming clear that if Timothy was to be awake and dressed in time, Damian would need to do something about it himself. The boy simply would not wake up on his own. And so, with a sigh of contempt, Damian stalked over to Timothy’s spot on the floor, and kicked him in the stomach.

Timothy wheezed. It was a pleasant sound.

Up and dressed and eyes halfway open, Timothy stared blearily at Damian, head cocked to one side and eyebrows furrowed.

“Your cravat is wrong,” he mumbled through his drowsy haze and aching midrift.

“Your stockings don’t match and half your buttons are done up wrong,” Damian retorted. “Honestly, it’s like you’re trying to disgrace the family name.”

Timothy only blinked at him in confusion, then looked down at his chest.

“Oh,” he said, “right.” His hand didn’t move.

With a huff of annoyance, Damian reached out and refastened Timothy’s wayward buttons, and, a small smile breaking through onto Timothy’s face, he untied Damian’s cravat in return.

“Cravats aren’t so bad once you’ve got the knots down,” he told him, as he knotted the silk tightly under Damian’s chin. “You’ll learn one day, I guess.”

Damian stifled the frustration of once again being treated like a child– like he’s someone incompetent and incapable of even the simplest of tasks. He huffed a breath to show his displeasure.

“I know, Timothy,” he snapped haughtily, with his chin held high in order to retain some dignity. He tried to make it seem like he was looking down at the other boy’s antics despite being a foot shorter than him, but it only made Timothy look too fond for his liking.

Downstairs in the parlour, Pennyworth had laid out a resplendent breakfast spread, but Damian only picked at it. Father, as usual, ate his breakfast alongside the morning paper, despite the risk of spillage, and– as always– noticed when one of his boys was not eating them out of house and home.

Father was always perceptive like that.

“Nervous?” he asked, and Damian scoffed as he nibbled on a slice of bread. Nervous? What could he possibly be nervous about? Father raised an eyebrow, a habit he had no doubt learnt from Pennyworth, who was the master of it, and returned to his meal upon seeing Damian’s scowl as an answer. Damian continued to pick carefully at his food; it would not do to spill crumbs on a day like today.

Damian, as had his brothers before him, had been assigned the great honour of heading the eel for the parade, ousting Timothy from his long-held spot and taking his rightful place as leader of the local children. Timothy had pretended this did not affect him in any way, but Damian had seen the flicker of hurt, of bitterness, of anguish on his face during the hand off, and it felt good– in a perverse, spiteful way– to hurt him like that. Timothy was his brother, but not by blood, and Damian felt no real kinship with him, despite what Father told him. They did not know each other well enough yet, and Damian did not entirely want to get to know him either.

Regardless of his thoughts on the matter, Damian knew he had to integrate himself into the family somehow, follow their traditions, learn their ways, and earn his place in order to truly belong and be deserving of their care. As much as he proclaimed his right as blood son, he was no better off than the others– a bastard son was little higher regarded than adopted ones, in the eyes of society after all– and coming into the family so late meant he had a lot of work to do to catch up.

Damian, of all his father’s sons, was the one who needed to affirm his place here. He was the one who needed to follow the traditions more than anyone to stake his claim as his father’s rightful heir.

Thus, the eel.

A long cloth of a thing that hid a line of children underneath, ribbon-wrapped poles held the head, body and tail upright to simulate the way eels wriggled along the river banks. Its once vibrant colours of red, yellow and green were now more muted with age and use– the march of the eel was a yearly tradition that prayed for good harvest after all.

Damian couldn’t help but compare it to Grandfather’s stories the more he thought about the eel’s fluttering colours and hanging strips of red, yellow and green cloth. He’s grown up listening to the stories of dances in the far East– almost the same march as what was happening today, but with a dragon instead of an eel and good luck instead of good harvest.

It was apt then, he thought, to uphold the traditions and stories of both his bloodlines.

The assembly was fiddly and more frustrating than what it was worth and the costume itself was claustrophobic and overly hot, but Damian took his role with the seriousness it deserved. He refused to mess around and trip his fellow eel-walkers on purpose, unlike those behind him in the line, who shoved each other to and fro. One even had the gall to stick a foot out to trip him.

It took the adults a good half hour to wrangle them all into their starting positions, all the little children in a line with Damian in front, but once there, they were finally able to move. The parade started beneath the flagpole in the market square, and they trooped down Fore Hill towards the river where curious cows watched on the opposite bank. They swung right after that, where they marched their way back up the hill through the castle mound, where the festival was already in full swing with sounds of people cheering. Damian felt like one of the heroes from his grandfather's stories, leading armies and charging at enemies at the forefront of battle– if only battle meant the awful fond coos of the watchers, and his army consisted of rowdy children who had to be told to watch not to step in the mud puddles. They finished right in front of the cathedral, where the dean prayed for a good harvest and an abundance of fish and eels so the city might prosper. Damian thinks he saw Todd scowling at anyone who dared to skimp on their tithes, like the good, albeit scary, layman that he is.

Having finished the march and the sermon now completed, Damian relinquished his duty to the nearest adult who could pack away the eel until next year. The man who took it from him took in his now-poleless form, shook his hair in fondness and instructed him to enjoy the rest of the festivities. Damian honestly would have scowled if it were anyone but Father who did that, but as it was, he instead tried to hide the blooming warmth of pride in his chest. A drink was acquired and consumed while the eel got packed away carefully– Damian was sure because he had been watching with keen eyes– another hand ran through his hair that he pretended to be annoyed at, and then Father left him to enjoy the rest of the day, his presence requested elsewhere.

Well, left him to enjoy it but not before giving instructions to Damian to stay with Timothy the entire time– which he absolutely rankled at. He wasn’t an infant, liable to get under someone’s feet or cause a commotion; he did not need Timothy to mind him like a nursemaid.

Father was adamant however, and so Damian deferred to his rule despite how irritated it made him.

It took all of five seconds for Timothy to get dragged away by both his friends and Cassandra into some kind of scheme that Damian did not care about.

Inwardly, he tutted–Richard would be so ashamed if he knew of Timothy’s desertion mere moments after being tasked with Damian’s wellbeing. Damian was not, however, completely inept– he knew how to look after himself– and so he did not feel the slightest bit nervous wandering around the festival grounds alone for the first time.

The hill was busier than Damian had ever seen it, thronging with bodies laughing and shouting and singing. Above the din, he could hear music and see groups of people dancing to the tune in what little clear space they could find. Smoke billowed into the sky, smelling of charred wood and cooking meat, and there were even enough types of fruit pie by the tables to make his mouth water just by sight alone. Children smaller than Damian raced about, getting in everybody’s way– but no one begrudged them their joy. It was a festival, after all.

Though Damian was sure it was also a hotbed for pickpockets, so he held his money pouch closer from where he had it attached on his belt.

Towards the edge of the main gathering, Damian could finally see where all those small children had been rushing off to: there was a man sat cross-legged on top of a tree stump with a brightly-coloured mockery of a jester’s hat upon his head. He seemed to be telling a story complete with hands waving expressively around, and the children who listened, scattered about on the grassy floor in varying degrees of tidiness, seemed even more excited than they had while weaving between stalls and legs at high speeds.

Damian wondered idly what was so important about this man– his stories, his jokes, his songs– that the children adored him so much to give him so much rapt attention. He would listen in, just for a second, he decided, and then move on. It was just to see what was so interesting, after all; he’s not like these single minded children who were as gullible as they were easy to entrance.

“Well, now you've all heard the story of Hereward the Wake, and you’ve all heard of our lovely saint, Etheldreda. Now, I’ve got one last story to tell you, little ones. It’s a scary one though, that alright?” the man asked. The children clamoured at him with cheers, and his bells jingled as he laughed at their reaction.

“Well, if you’re sure,” he wheedled, voice bright in that way good story tellers were. It reminded Damian of Todd, before he outgrew bedtime story telling with them.

The children were fast working themselves into a frenzy, and as the man eased back down upon his stump, the gaggle fell eerily silent with anticipation.

“Now,” he began, his voice the perfect cadence for storytelling, and Damian had to admit, the low and secretive tone was just interesting enough by itself that you had no choice but to listen in. “I heard this one from a friend of mine, and he ain’t ever told a lie in his life, you hear me. Every word of this story is as true as poor old jolly Ollie’s lost head– and it even begins not so far from here!”

It would take a fool not to see that the children were enraptured, bright eyes wide and mutterings hushed to hear more. Against his better judgement, Damian took a step forward. If not for the way the man was looking at the crowd– which included Damian because he had walked close enough to not be confused with passers by– he would have scoffed at himself. He was not the type to get pulled in by a mere ghost story.

But that didn’t change the fact that he was there, tuned in like the other children short of being sat with them on the ground.

“The travelling menagerie had been all over, from London, to Brighton, to Bristol, to Birmingham, and even a couple o’ places that don’t start with a ‘B’. They didn’t stop here, but they did stop in the grand old city of Cambridge, to put on a show for the public.” The man told them, voice lilted up and down words to not sound as monotonous. “Now, a menagerie has all types of beasts that you could dream up, and then some! So it weren’t that surprising that they had a tiger, roaring and clawing at its cage.

“They had an elephant too, and more monkeys than you’d know what to do with! But it were the tiger that people really wanted to see. And wouldn’t you want to as well! Beautiful beast it was! Eyes like fire and a coat of gold an’ black.

“But tigers… well, they’re wild animals, my sweets; they’re not meant for cages. And this one was no different, taken from the very forests of far away India. He missed his home, you see. So one night, when the menagerie were packing up to move to their next stop, the tiger breaks out of his cage. And he runs. Runs! Runs as far away as he could!” The man said, fingers dancing along an opened palm.

“Now, a tiger breaking free ain’t exactly quiet, and the folks there knew that something were afoot, so they went to investigate what the ruckus’s about. And the tiger– it’s wild with fury by now, roaring and snarling and full of fire!” Hands were thrown in the air, fists curled up like paws and the man’s teeth bared like a cat. The kids nearest to the man gasped in horror at the jump, and Damian scolded himself for flinching as well. “And when the tiger’s keepers found it, well what was there left for a tiger to do but kill ‘em?

“CHOMP!” Several kids scream a bit, before hushing back down so the man could continue. “So, the tiger kills the men, biting, and scratching, and snarlin’ in all its fury and madness! And when it’s all over, with blood running down its maw, it runs from the market square, through the streets, and out into the farmlands around the city!

“No one saw the tiger for a week or more, and everyone thought it was dead or run off or otherwise gone for good. Tigers weren’t made for the Fen, you see. So the menagerie moved on, and everyone forgot that a tiger had ever even escaped from there.” The man nodded solemnly, his hands crossed on his chest.

The kids around his feet didn’t seem to buy the peaceful act.

“Oh that’s awful!”

“I hope it’s gone! Tigers are scary!”

A brave soul tugged at the man’s pant leg, face curious but horrified, as if she didn’t want to know the answer to the question that leaves her lips. “Was it gone?”

The man looked at her.

And then he smiled, wide, with teeth, like he was holding a very scary secret. Unnerving.

“That was their first mistake.” He took a gulp from a flagon of ale, and Damian had, almost without noticing, stepped closer until he was almost among the peasant children squatting on the floor. He took a step back, shook his head, then paused from where he was trying to get away when the man started speaking again.

“The tiger came back, you see, but not to Cambridge– no not Cambridge at all! It cropped up again in Cottenham, and killed a whole flock of sheep afore it ran off again– but it were spotted there, for sure. No one could deny seeing those beady yellow eyes anywhere!

“And then over in Over, spotted running through the fields with its big striped hide, and two dogs and five chickens were lost in the night!” He told them, voice becoming faster with every revelation.

“And then it crossed the river and cropped up in Wilburton. In Wilburton there weren’t nothing for it to eat– and so it moved on without striking, hungry, desperate– until it got to Sutton.

“In Sutton it was hungrier than it’d ever been, and it wanted to kill, kill, kill and eat, eat, eat, but everyone had already been warned and locked their animals and children away! So for two whole days, the beast stalked Sutton, roaring and wailing in the mist at night–

“–and when everything went quiet.” The man whispered, suddenly stopping from his crescendo of listing down the crimes the tiger had committed in its wake. “People thought they were safe. They were happy, and they thought it would be alright– but NO!–”

A few kids screamed, and Damian stopped himself from insulting their weakness as if his heart didn’t beat so loudly in his chest.

“They weren’t, though. No, not at all! Tigers are clever, see, and it waited until they were all nice and used to the noise before it went quiet and waited. And that night, walking home, a farmer saw a shape in the dark, and the shape in the dark followed him all the way to his door without making a sound. The shape in the dark was huge, with eyes like burning coal, and a twitching tail like a cat playing with a ball of yarn. The farmer told his wife, thought mayhaps it were the tiger, and she told him that were nonsense and had he been in the drink again ‘cause that’d certainly explain a few things. ‘The tiger’s gone!’ she told him. ‘Stop jumping at shadows.’” The man pitched his voice high in the story, mimicking a scolding wife and making some children laugh, before his voice grew grave.

“But it was the tiger, and the tiger still hadn’t fed.” A chorus of mutterings spread from the audience about the silly woman. The man waited until every kid stopped their nervous whispers, before he continued.

“The next night, it followed the local drunk off the boardwalk, but it didn’t like the taste, and left him with his guts spilling out into the reeds. The dawn following, it found the farmer again, out for a morning stroll with his wife, and they screamed and waved their arms– but the thing is, once a tiger’s got your scent it’s too late! By the time another townsman raised the alarm, they were dead and long gone.” The children gasped, but it was not one of fear, not when children love such gory stories.

“The tiger was sated, and moved on, and as far as I know, it ain’t resurfaced yet. The fen tiger, killer of man and beast, even though it’s been many years since it first escaped, is still out there somewhere, stalking folks through the droves and looking for its next victim. Maybe, one day, that victim’ll be one of you–”

Children screamed all around him, and Damian scoffed at their antics despite feeling his heart in his throat.

The story was not meant to stick with Damian.

It’s not like the other stories he’s heard of– of glory and days long past, or of the rules it was wise to follow– but regardless, the story, the tiger, the warning– it all stuck to him like the sticky weed that grew up stubbornly against the wall.

Damian had never been good at letting words pass him by or at letting things go. This story though– this tiger and the warnings that followed it… Damian was sure this was a way for him to prove himself.

The eel could be just the first step to showing Father that he was a worthy son, a true heir, and deserving of the status that came with their family name. Damian knew he had been a surprise to everyone– it was a surprise to him when mother sent him halfway across the country to live with a Father he never knew, a surprise to Father himself, and a bigger surprise to strangers who knew the only Wayne left were more partial to adopting than having a child of his own.

Far too invested in the life of a man richer than they would ever be, they muttered and whispered around corners and in alcoves, but Damian heard all of them, every hissed piece of gossip, every whispered rumour.

"How odd," the old seamstress on Cherry Hill had told the baker's wife, "that Bruce Wayne, most dutiful of night watchmen, would have a child out of wedlock."

"Ain't it queer," he heard the eeler asking the cow herd, "that he'd forget about a whole woman and son when he knows every one of our names?"

"It don't make sense," the scullery maid told fisherman number one's middle son one time when they passed and pretended not to hear, "he's such a devoted father to those other boys, what's he want a bastard for?"

Damian had heard them all, fought several who made lurid comments about his mother, viciously insulted those he deemed unworthy of a fair fight, but let their words take root regardless.

He needed to prove he was worth the trouble, that he was a better son for being blood and not just adopted in like the rest, that this family still had honour. He was the blood son– he wasn’t chosen, loved despite the fact that the only thing that made them family was the name– and he was here to prove that he was worth the same love his siblings had because of it.

As he walked home, as he ate supper, as everyone congregated in the parlour to talk about their day at the festival with joy, he mulled the story of the Fen Tiger over, and he began to plan his next steps.

By nightfall, the fog had rolled in, thick and clinging, and Pennyworth was fretting by the door as Father shrugged on his coat to leave. This was primarily because Father, for all his mental acuity and infinite wisdom, refused to take a lantern with him.

This was far from the first time they had had this fight, stood by the front door in the dark, and it would not be the last.

And like the last time, Father eventually got his way. He always got his way.

When he did, Pennyworth would make one last round of the house, checking all the rooms, all the locks, blowing out the candles. And when this was done, Pennyworth would go to his room, pray for his master’s safety, and sleep restlessly until daybreak.

Damian knew this nighttime routine as well as he knew his own name: forwards, backwards, and in several languages.

He knew exactly when Pennyworth would crack their door open and check for two sleeping boys, and he knew exactly when Pennyworth would slip down the stairs to his own rooms, and he knew exactly when the house would fall into the kind of total silence that would be eerie if it were not his home. Damian, dressed in his daytime garments under his night-shirt, and his boots tucked under his bed, knew when the best time was to sneak away into the night to begin his quest.

Right on schedule, Pennyworth cracked open the door, but Damian was prepared and so feigned sleep like the most expert of actors. He waited. Counted slowly in his head until he estimated that twenty minutes or so had passed, and then crept out from between the covers. He moved as silently as he was able, and though it did not stop the fabric of his clothes rustling, it did stop floorboards creaking.

It would not do to wake Timothy. His brother would ruin his plans with his moaning and meddling, and Damian would not be stopped in this.

He was just tying the laces on his boots (and trying again when he got it wrong the first time) when he heard a grumbling, muddled, “Damian? What’re you…” from the other side of the room.

Freezing in place, he barely breathed, and waited– heart in his throat– for Timothy to roll back over and go back to sleep.

No such luck, of course; Damian’s curse had followed him across the country apparently, for Timothy sat up in bed and narrowed his eyes at Damian, crouched in the only puddle of light from the open window.

“Why’ve you got your boots on?” he mumbled, hands rubbing at the sleep dust in his eyes, and Damian again did not reply. It was always better not to engage with Timothy– that was what Father always said. Damian blatantly ignored that this advice was normally in a context of ‘stop fighting your brother over petty, insignificant things’ and not the ‘ignoring him because he’s meddling in Damian’s affairs’. “Are you…leaving?”

Not answering apparently only made Timothy wake up more, however, and soon Timothy was also getting out of bed.

“I’m coming with you, wherever you think you’re going,” he said with a yawn and a stretch.

Damian furrowed his eyebrows. This was unlike Timothy, who was normally perfectly willing to let Damian get in trouble for all kinds of things.

“Why do you think I should let you?” Damian asked stiffly.

“Because you need someone to keep you out of trouble. I don’t know how it was wherever you grew up, but it’s dangerous to be out alone at night here.” Damian snorted. As if he couldn’t keep himself safe! The audacity!

But Timothy was already throwing on a shirt and shoving his boots over stockinged feet, though, and Damian doubted he truly had any say in the matter. This was precisely why he hadn’t wanted to wake Timothy, he thought as he listened to him whisper to himself lists of things they needed for an adventure; he never behaved as expected.

As if Timothy could read his mind, he smiled at him in the dark, pointedly keeping an eye on Damian as he walked around the room to get his bag.

Damian would never admit that this adventure was a bad idea, no matter what anyone said. It was, of course, a terrible idea, and he knew this from the moment they left the grounds, stepped onto cobbled streets and snuck out towards the river.

They moved like shadows, silent and smooth, though Damian of course hissed criticisms at Timothy’s every move– it would not do for him to get a big head or think Damian was not in charge– and after climbing over a gate, they were on the river bank.

The river snaked away further than Damian could see, and beyond it was blackness. No one ventured into the fen after dark. He tried to not let that tidbit of information weigh him down even as it rattled noisily in his head over and over again.

When they reached the bridge, Timothy stopped, put his hands on his hips, and turned to Damian with some kind of look upon his face. Damian was not quite as knowledgeable as perhaps he should be when it came to Timothy’s facial expressions, but this one was particularly ambiguous in the dim light.

“So,” he said, lips tilting into something of a grin, “what’s your plan?”

Damian stared at him for a moment, uncomprehendingly. What did he mean by ‘what’s your plan’? The plan was obvious surely from what Damian told him on the way to the riverbanks? He thinks Timothy should be old enough to not let the spooky aspects of the tale scare the logic out of him.

“I’m going to find the tiger,” he said, slowly and clearly. Evidently Timothy was missing a few of his faculties and needed a reminder of why, exactly, they were standing by a bridge in the dark.

Timothy made a rolling motion with his hand.

“Yes, and…?”

“And I’m going to catch it and bring it home to prove to Father that I am a worthy heir and a good son.” This was all obvious, he was sure, but Timothy’s eyebrows were slowly raising higher and higher up his forehead so perhaps he was missing something. That, or Timothy could really stop patronising him with his playing stupid act.

“Of course you are,” he said, as if placating a small child. It rankled Damian, to be spoken to with such condescension. “And how exactly do you plan to do that?”

Damian blinked at him slowly. He wasn’t quite sure what Timothy was implying, but he did not like it.

“With a rope?” Timothy looked like he was trying not to laugh. Damian knew he never should have let him come.

“Do you have a rope?” He looked through his own bag. A knife, a flask of water, a spare pair of stockings, a small pouch of coins, a flint and steel.

No rope.

“No.” A beat of complete silence, but for the rustling of the reeds of course. The fen was never truly silent, just resting. “Do you have a rope?”

Timothy ran a hand down his face instead of replying. Damian could see the shudders of repressed laughter in his shoulders, and already knew the answer.

“This was your idea, not mine. Why should I have the rope?”

It was not a question Damian knew how to answer, so instead he stomped forwards towards the bridge. Timothy’s arm blocked his path and he scowled. There was a serious look on Timothy’s face, protective, unyielding. He was not going to let Damian through until he had given him a satisfactory answer.

“Step aside, Timothy. I do not need your help.” Timothy was not going to stand between Damian and his prize. He would not let him.

“Not until you give me a reason to believe you are not going to get yourself killed.”

“Grandfather always told me tigers were afraid of fire. I have a flint and steel. Now, step aside.” Timothy’s arm dropped. Damian stepped onto the bridge.

“I’m still coming with you.”

Damian prayed for forgiveness for when he inevitably committed fratricide. The time was coming, he was sure.

They stomped their way through the fog in silence, neither willing to speak to each other more than a brief ‘mind that rock’. They had not fought, not really, but everything was strained enough that neither really wanted to misjudge a comment and set off a bitter row; it was clear that neither wanted to be left alone in the fen at night.

Somewhere in the distance, an owl hooted lowly, and closer by, crickets chirped, but between Damian and Timothy there was no sound. The silence was such that they could hear the creaking groan of a windmill’s broken sails shifting in an unfelt breeze, the haunting lullaby floating across the air towards them.

At the next crossroads, Damian turned left over a low bridge. Truly, he did not have the slightest clue where he was going, except away from civilisation, out into the wilds where tigers prowled. Even if he had known where he was heading to begin with, he would not now, especially with the shifting fog. It swirled and ebbed and flowed like water against the shore– sometimes so close he could feel it caressing his face and see no further than the tips of his outstretched fingers. Sometimes, it was so far away as to be forgotten– with the moon and stars suddenly visible to light his way and the river a black silk ribbon guiding him through the labyrinth towards the beast at its centre.

It made him sleepy, the quiet, the thickness of the air, and even though the path was flat, Damian found himself exhausted. With every yawn, Timothy would quip that they should turn back, that surely he was done now, and every time, Damian would snap back a sharp ‘no’. It was enough to fuel him for a while longer, despite his dragging feet.

“I wonder which came first,” Timothy mused, looking up at the tarred wood of the windmill, the slats of its sails hanging on loose nails and the sail cloth torn, “the legend you heard this afternoon, or the fen tigers who sabotaged the mills and pumps.”

Damian did not reply. He was too busy watching the fog swirl and eat a stunted tree on the opposite bank. It was becoming thick and heavy again, and they would have to watch their step when it came in fully.

When they moved on again, Damian forgot to watch his step.

More accurately, Damian saw something and was so distracted that he forgot steps were a thing he had to watch to begin with, enthralled by a distant mirage. Timothy, rambling about windmills and pumps and bridges, and concerned– distantly– with how they were going to get home, had not noticed it yet, hadn’t seen, but Damian had.

“There’s a light,” he said, bluntly, and there was indeed a light, floating a little further ahead and just around the height of Father or Pennyworth’s shoulder. It was a soft light, but penetrating, a lantern, Damian was certain.

“I’m going to see who it is. Maybe they can tell us where the best place to find a tiger is.”

He took off without waiting for a reply, purpose accelerating his steps, eyes focussed on the light, the light, the light. Whenever he thought he was drawing near, it bobbed a little further away, as if its holder were walking away from him.

He called out. The light moved once more. He began to run, and it was as if everything else had faded away.

The reeds made no noise, his footsteps were muffled and if Timothy was following, Damian could not tell. The light was ahead of him, and he was finally gaining ground. He reached out a hand…

“Damian stop! You’re about to–”

The ground fell out from beneath his feet.

Of course, the ground did not actually fall; the earth did not crumble; the earth did nothing wrong. Damian, apparently, had simply found out the hard way that if one does not watch where one is going then they are likely to step off the path and into a ditch.

The first thing Damian noticed was that his feet were wet, then that his hands stung, then that he was in the bottom of a ditch, with mud and filthy water up to his waist and surrounded by reeds so tall he could not see the sky. He did not panic, and he did not call for Timothy to help him. Timothy is a liar and an dishonourable rat if he says otherwise.

If Timothy came wading in after him, that was his choice and an unnecessary one at that.

Damian did not need help.

When they made it back up to the path, both of them were filthy and soaked, and the light was gone. Timothy’s ire burnt hotter than the sun when he rounded on Damian, as if his anger alone could evaporate the water in their clothes or turn the slime on their skin to dust.

“You,” he said, voice deceptively low, “are an utter idiot. How many times have we told you not to go wandering off? And we’ve definitely told you not to go chasing random lights! You cannot trust your eyes out here at night, Damian. The fen likes to play tricks on you.”

Damian tried not to feel like a chastised child and failed. The feeling settled in his gut like a stone, and he felt it choking him.

“Do not ever do that again, do you hear me?” Damian nodded mutely, ignoring the shame welling in his throat. His eyes itched, and he did not know why.

Abruptly, Timothy flung his arms around Damian’s shoulders and squeezed. His hands were shaking; Damian could feel them against his shoulder blades, trembling like leaves in a sudden breeze, like the reeds that shudder with the slightest breath of air.

“You don’t get to die on me,” he hissed in Damian’s ear, “What am I supposed to tell Bruce and Alfred? ‘Oh your son fell in a ditch because he got distracted by a lantern man and I did nothing, so sorry’? It wouldn’t be worth going home; I’d get murdered for sure.”

It was meant to be funny, to ease the fear of their near miss, to make Damian laugh and chase away the spectre that haunted them. Instead, Damian heard the words Timothy did not say: ‘please don’t leave me here alone’.

The guilt was more suffocating than the fear.

“The lantern man doesn’t actually exist, Timothy,” Damian said into the darkness once they had all calmed down.

Timothy stopped so abruptly Damian almost walked into him, and instead shoved his shoulder lightly in his displeasure.

Timothy turned, face a strange mixture of confusion and anger.

“You mean to tell me you do not believe in the thing that almost killed you not even an hour ago, but you do believe a tiger is wandering around out here?” The incredulity in his tone was almost funny, if it weren’t for the offence and annoyance that coloured it too.

“Well, first of all, we did not come to any harm, and even if we had it would have been the water or the reeds or the fall that did us in, not some ghostly creature of the night. Secondly, I believe in the words of others far more than yours. Thirdly, tigers actually exist; it is not such a large stretch to believe them to lurk here too.”

Timothy sighed, exasperated.“Damian, that storyteller tells a different scary tale every year and every year he claims them to be true.”

Damian stilled then, for a moment, but it did not matter, truly, how many tales the storyteller told, only their reliability.

“And that does not make them false,” he replied, to which Timothy let out an explosive breath through his nose. It was rather unbecoming for someone who claimed to be a Wayne. Damian was disappointed in him.

“Alfred told us to be wary in the fog, lest we fall prey to the lantern man.”

“Well then perhaps Pennyworth is more of a superstitious fool than I gave him credit for.” Riling Timothy up was more fun than anything, save going out with the hunting dogs, and Damian found himself laughing, deep down in the back of his mind where no one would ever know.

The insult to Pennyworth was the final straw for Timothy, who stalked off ahead grumbling unconscionable things under his breath.

Timothy was still in a terrible mood when they stopped for a drink and a rest. Sat on an old stump with their backs to the ditch, facing the desolation of the fens stretching out into the black fog, Timothy all but shoved the flask into Damian’s hands.

And Damian…Damian did not know how to make amends, how to apologise for who he was and who he was made to be; could not apologise for being the usurper without admitting that his position was not his by right– an unutterable, terrible prospect.

He had hurt Timothy, he understood now, but he could not apologise for it. Damian Wayne was not in the habit of apologising to those who were beneath him, and to do so was to admit equal ground between them and allow Timothy a victory.

And so they sat in silence, in anger and regret, and listened to the sounds of the fens.

Damian returned the flask to Timothy, and closed his eyes. It was, despite all that had happened and all that was still happening, peaceful here. Away from the hustle and bustle of the city, away from the judgemental looks and whispering voices, Damian could relax, even just a little.

He felt warm, a little sleepy, wrapped in the still night air. There was not even a breeze now, and even the whirring insects and croaking frogs had turned to silence. There was nothing, nothing, and then a rustle of reeds, as if something was watching them at their backs. Damian was not worried; he knew the fen was not dangerous. Nothing would hurt them here.

He felt Timothy stiffen beside him, and, as if in a dream, heard him say urgently–

“Damian, run.”

A thrill of fear shot through him, waking him from whatever trance he had slipped into, but it was not quick enough. Timothy grabbed him by the hand and pulled, dragging him at a flat sprint down whatever path was closest.

When they stopped, after having ran as if the hounds of hell were on their tails, Damian found himself near shaking with cold despite the warm summer air. Timothy, too, was shuddering, and between panted breaths, told Damian that the unnatural stillness, the utter silence, were signs of a demon lying in wait; and that rustle, that lurking presence, amidst all that peaceful stillness and quiet, was enough to jerk Timothy from the stupor it had put them into.

“They stalk travellers at night,” he said, loosening the grip he had on Damian’s hand, “wait for them to get tired and sit near the edge of a ditch. Then they drag them back and drown them and eat their souls.”

That drew him up short.

“Eat their souls?” he asked, voice squeaking slightly at the end. He wasn’t afraid. He refused to be afraid, but his traitorous body had not quite got the message yet.

“So they say,” Timothy replied, squeezing their joined palms once before letting go altogether. He straightened up, frowned as he looked around them, found a path apparently at random, and began to march down it.

Apparently their reprieve was over.

“Timothy,” Damian said as he stumbled along the path, tripping over holes and ruts in the dry mud, “I think we may be lost.”

The darkness made even familiar sights unrecognisable, but even so, he was convinced they had taken a wrong turn a mile or so back, and the treeline to their left was indescribably different to the one that had been on their right when they left. Timothy turned and gave him the driest, flattest glare Damian had ever seen, a truly worthy successor to Pennyworth’s deadpan disrespect.

“You don’t say, little brother,” he drawled, and Damian tried not to feel cowed by his blatant frustration.

“We should turn around. We made a wrong turn after the bridge.”

“If you want to, go for it,” Timothy told him. “But I’m not stopping that demon from eating you if you do.”

It was clear that he was utterly fed up with the whole experience, with Damian, and by this point, Damian couldn’t even blame him. He shivered in his wet clothes, kept damp by the fog despite the fact it was not truly cold.

“I do not know the way,” he admitted, the words forced out and choked. “I have not spent so much time wandering as you and do not know the paths.”

Timothy’s eyes narrowed and he turned to keep walking forward. Damian, miserable, stumbled along behind him once more. After an endless moment of silence for Damian’s dignity, Timothy responded.

“Droves,” he said, quietly.

“Excuse me?” Damian was confused. This was not a word he had heard or knew from books, nor one that could be deduced through etymology.

“It’s not a path that we’re walking on,” Timothy explained, not unkindly. Damian had to give him credit for not treating him like an imbecile, but it did little to ease the tight, frustrated feeling in his chest. “This is a drove, a road to drive livestock along and to keep them out of the flood waters when they come.”

Damian mulled this over as he listened to the reeds rustling with his footsteps.

“They’re the same thing,” he decided, and Timothy scoffed.

“No, they’re not. A path is entirely separate and not at all the same.”

“They are both a track to walk on, are they not?” he laughed, and Timothy– scandalised– stopped stock still to wave an accusatory finger in his face.

“How dare you, little monster. How dare you insult your heritage in this way. A drove is a drove, and a path is a path, and they are not and will never be the same.”

They lasted about five seconds before they burst into peals of hysterical laughter, Damian almost stumbling into the ditch once more as he shook at the absurdity of the moment. Luckily, Timothy grabbed hold of his shoulder to stay upright as he laughed and once again saved him from a watery doom.

“We’re still lost,” Damian reminded him, once they had both recovered from their hysterics.

“We’re still lost,” Timothy agreed as they continued walking in silence.

The first time Damian saw it, he discounted it wholesale. There had been so many terrifying and wondrous things that night, that he really did not want to know what that vaguely beast shaped shadow in the corner of his eye was.

It was not the tiger, and so he did not care.

The second time, when the shadow’s eyes glowed and all the hairs on the back of Damian’s neck stood on end, it was harder to ignore. But Damian was nothing if not stubbornly tenacious, and so he persisted in trudging along next to Timothy, who was attempting to turn them somewhat in the direction of home.

They were, by this time, hopelessly lost– in Damian’s eyes at least– with every drove and pathway looking identical and every bridge too similar to completely discount the idea that they were, in fact, still wandering in pointless circles. The fog and clouds had obscured the stars, though not quite the moon, and thus Damian’s only way of navigating by night. He was slowly coming to the realisation that without Timothy, he would mostly likely be dead, and it was a realisation that he did not like overmuch.

The third time was impossible to ignore, for it became suddenly less of a shadow and more of a massive black beast looming out of the fog on the other side of the bridge they were about to cross. Damian did not scream, no matter what anyone said– though Timothy let out a strange, strangled yelp of surprise– despite the shock of its appearance and despite the abject terror that coursed through his veins for no reason at all that he could fathom.

It– the shadow– the monster– did not growl, did not make a sound, and its eyes glowed like burning coals in the darkness.

Unnerved, Damian looked to Timothy, and found him standing, statue-like, with his eyes clenched shut–

When he looked back again, the beast was gone, leaving only the echoing trace of a mournful howl on the still air.

A dog such as that, Damian realised belatedly, would make a fantastic companion for him, and he wished he had had the composure to ensnare it, rather than standing gobsmacked like a fool.

“Well,” Timothy said weakly, once he’d opened his eyes, “at least we know roughly where we are now.”

Damian wasn’t quite sure how they’d made it to Littleport with all that had happened, but Timothy insisted that such was the case, that the Black Shuck only haunted the village and its surrounding area. It wasn’t just a ghost, or so they said, but also an omen of death should you gaze upon it.

“It is just a dog,” Damian told him. “A large one, yes, and not without a terrifying presence, but a dog nonetheless.”

Timothy was not comforted as Damian hoped he would be. It was curious to Damian, that Timothy believed so firmly in what Damian took to be local superstitious nonsense, especially when Timothy, like the others in their family, were usually so coldly logical.

But Timothy, he supposed, had not always been raised by father, and even when he was, had spent much more time under Pennyworth’s wisdom. As Damian had discovered, Pennyworth subscribed to his own brand of superstition, disguised as sage wisdom though it may be.

Perhaps it was not so surprising that Timothy, of everyone in the family, was most well-versed in local legends then, given all that he knew of his history. It did not mean Damian believed in it himself, or that he approved particularly of Timothy’s belief in it, but he could understand it a little more, and could see the value of the stories that came with them, the rules that came of them, and the safety they provided.

Its philosophy was undeniably sound. If one thought soul-sucking demons lived in the ditches, one was less likely to stray from the path; if there was a spectral black hound roaming the fen that was an omen of death, who in their right mind would go out at night and risk laying eyes on it?

Somehow, Timothy’s assertion that they were near Littleport was correct, and at his behest they turned towards home.

The problem was that they had not yet found the tiger.

Timothy, it seemed, had given up on that endeavour entirely, and Damian knew that his time was running out. He kept his eyes peeled, his knife at the ready, but saw nothing.

It was a keen disappointment to him, but he tried not to let it show on his face.

He knew that silence would be more beneficial for his hunt, cut short though it was, but he also could not bear the silence pressing in on him with the fog on all sides and the slowly lightening sky.

“Timothy,” he relented, “tell me a story. One I have not heard. One that I need to hear.”

Timothy gave him a level stare, suspicious, but after a few seconds of searching his face for deception, obliged.

“When I was young,” he began, as was the way of such stories, face trained on the growing buildings in the distance, but his eyes looked like he was some place else. “The ditches and rivers froze solid, as they still do every winter, and so we all took our ice skates out to race.

“This past winter was the first time I can remember that they did not freeze solid once, but they likely will again this year.” He continued on with a meandering story about his boyhood and the joys of skating with the wind in your face and tears in your eyes down the long, straight, ditches that they both now called home. He continued on, about how the ice– even when solid– could split unexpectedly, and about the boys and girls who, not knowing better how to watch the ice for malevolence, fell through. Timothy told him about how the ice froze far more solid than before above their drowning heads and frantically struggling bodies, about the water weeds that bound them, and the demons that sucked out their souls, and the monsters that ate their empty corpses.

It was a horrible story, one that left Damian on-edge with a tongue too tied to speak, and watching the sedge reeds closely, lest any demons come crawling out looking for breakfast.

He saw nothing, of course, but somewhere along the way a creeping, hunted feeling came over him. At the corners of his vision, he saw flashes of burning amber eyes, a twitch of a feline tail. Behind him, the rustling of reeds felturgent and dangerous.

He was being watched, he knew, and he hated it. So, he interrupted Timothy and his assertion that “when we get home, you have to be the one to tell Alfred why we came out here, Damian. We’re going to be in enough trouble without them thinking it was my fault so–” to tell him about the eyes and the tail and the reeds.

“I think there’s something out there, watching us, following us home.”

And Timothy looked at him with a glance full of sympathy, which Damian hated, and swung an arm about his shoulder, which he hated slightly less, and told him, in a voice full of truth:

“That’s the thing about the fens: there’s always something out there in the fog, little brother.”

#batfam big bang 2022#batfam fanfiction#Damian Wayne#Tim Drake#historical au#folklore and mythology#fenland legends#supernatural#not the fandom tho absolutely not#brotherly bonding#one shot#they're brothers your honor#this is fundamentally a celebration of everything i actually like about my home town#all the street names and places are real#all the stories are ones i have actually heard#the eel festival is also real i can post photos later if you're curious

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

This new Interpretation of Medusa in the new episode of Percy jackson, as a survivor of abuse that directs her pain, because of missing justice, against people that she associates with her abusers, shows not only how much Rick Riordan has grown as a storyteller and interpreter of mythology but also how much we as a community have grown in interpreting and understanding the deeper meaning of mythological storys and the context they were made in.

#percy jackon and the olympians#percy jackson#percy jackson tv show#percy#medusa#greek mythology#mythology and folklore#percy jackson episode 3

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

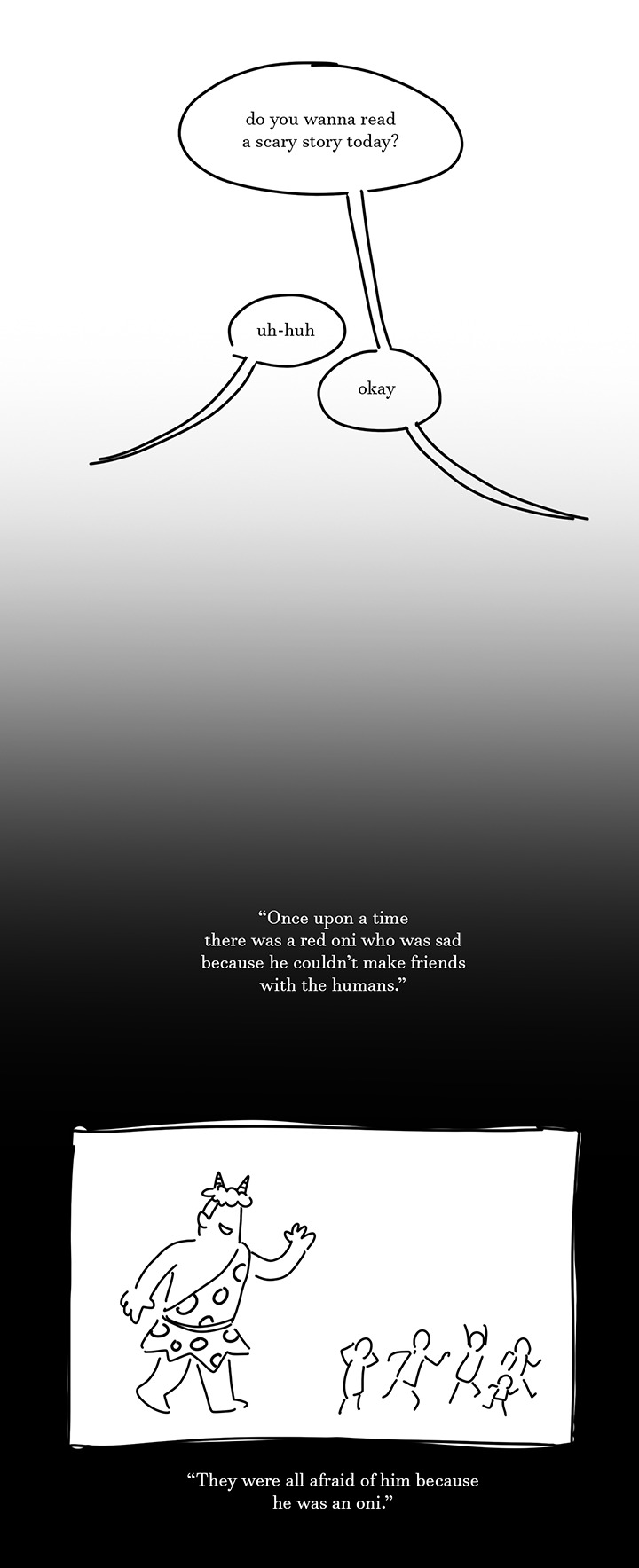

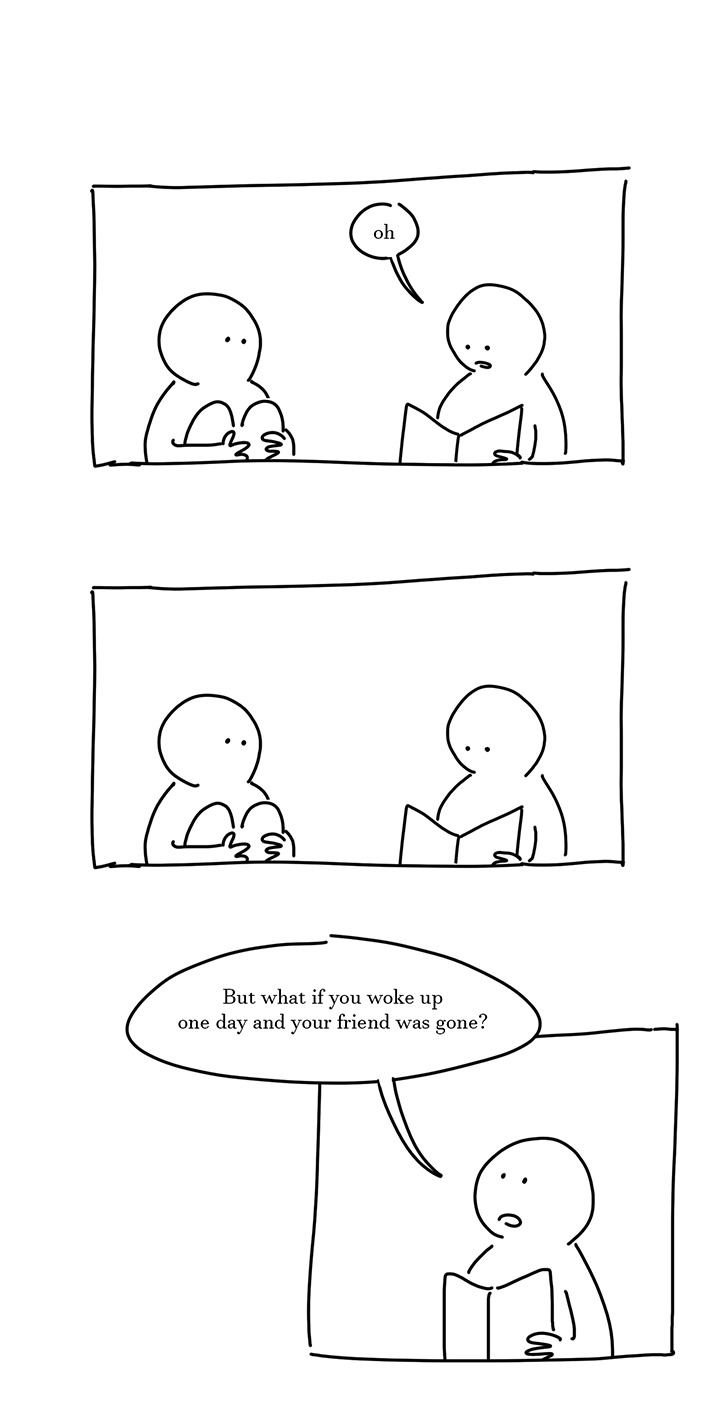

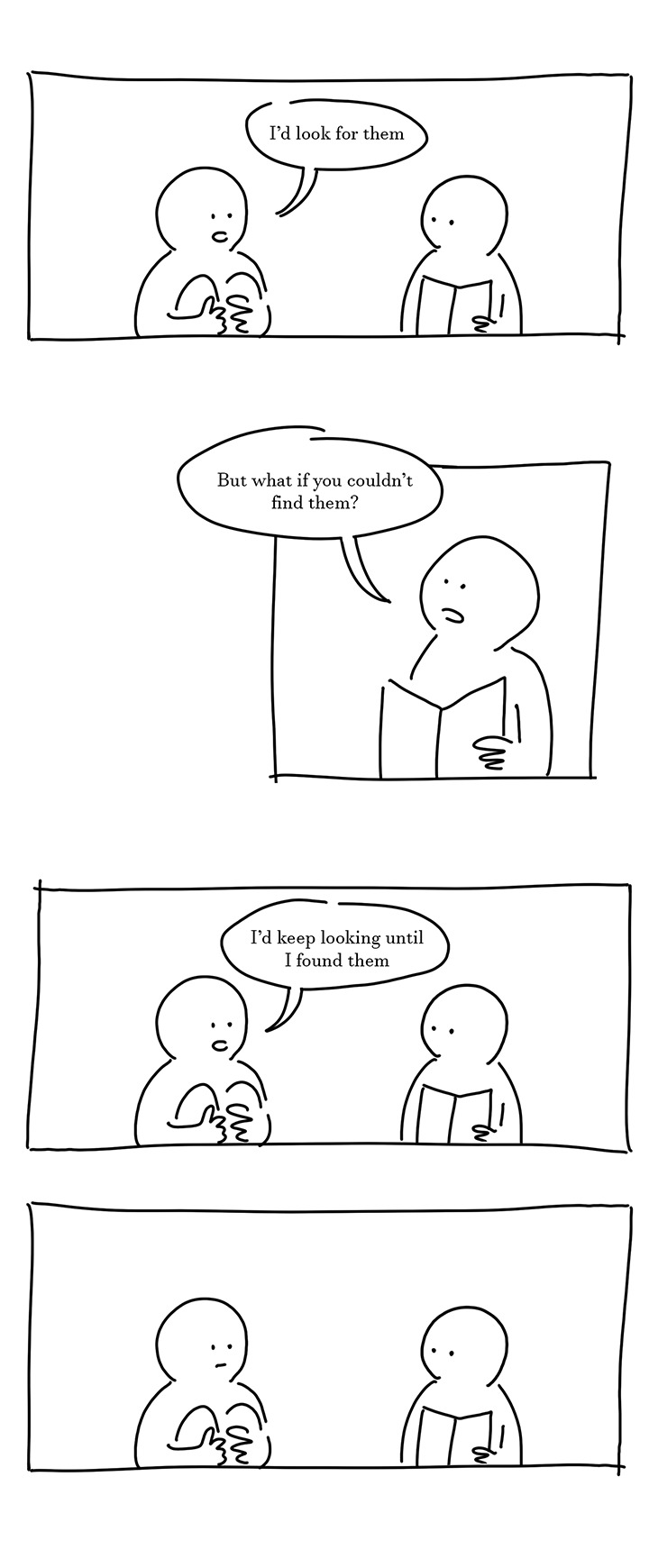

a comic about friends

in preschool someone read us the story of the red oni and the blue oni and it still gets to me a little

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Kelpie by Herbert James Draper (1913)

#herbert james draper#art#paintings#fine art#1910s#1910s art#academism#academicism#academic art#painting#english artist#british artist#mythology#scottish mythology#scottish folklore#kelpie#classic art

10K notes

·

View notes

Video

Indigenous Horror Films

#tiktok#indigenous horror films#Indigenous art#Indigenous writers#Indigenous artists#indigenous#watch this#mexican indigenous folklore#folklore#horror#horror films#movies#film#inuit#indie horror film#mythology

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

there is something refreshing to learn romanian mythology and notice that all creatures whom humans are scared of (a big majority of them) are only mean to us because we hurt them in the first place.

#romania#romanisme#romanian folklore#romanian mythology#romanian paganism#romanian culture#myths#folklore and mythology#mythology

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don’t know how many of you have read the story of Cú Chulainn and the folklore from that time that run alongside Cú Chulainn but they’re absolutely insane. Half the time these people are just murdering eachother for the most (to a modern audience) nonsensical reasons. Like what do you mean you guys are going to war because this one Bull, like the literal animal, is just like super great breeding stock. WHAT DO YOU MEAN THE BULL USED TO BE A FAIRY?!?! Why is Fergus banished not for getting tricked into giving up his position as king but because he decides to defect because the current king Conochbar tricks a group that kidnapped his fiancé and had them killed which is I guess apparently bad manners because three people defected over it. Also the way women are treated in these stories is terrible, it’s so so interesting and I’m obsessed with it.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

a shortcut through the swamp

#orignal character#oc#harpy dude#slavic folklore#slavic mythology#illustration#dark art#art#harpy#artists on tumblr#artwins#severin#seva

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm currently putting together a few pieces for a scholarship application, so I decided to go back and touch up some of my past work a little.

Here's a selkie! I just changed up some of the lighting and textures.

#artist#art#digital art#digital drawing#drawing#illustration#artwork#digital illustration#adhd artist#selkie#selkie art#foklore#folklore art#irish folklore#folklore and mythology

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

DNI if you:

are man or woman

are human or beast

dwell indoors or outdoors

browse clothed or unclothed

post by day or by night

reblog on land or at sea

#tumblr#blogging#social media#dni#folklore#mythology#nonbinary catgirl posting from a treehouse at twilight:

10K notes

·

View notes