#falstaff

Text

The way Sir Ian goes "no" and shakes his head 💙

Michael was so chill before "yeah we already know each other" but he's so excited he can't really hide it awww their hands 💜💜💜

692 notes

·

View notes

Text

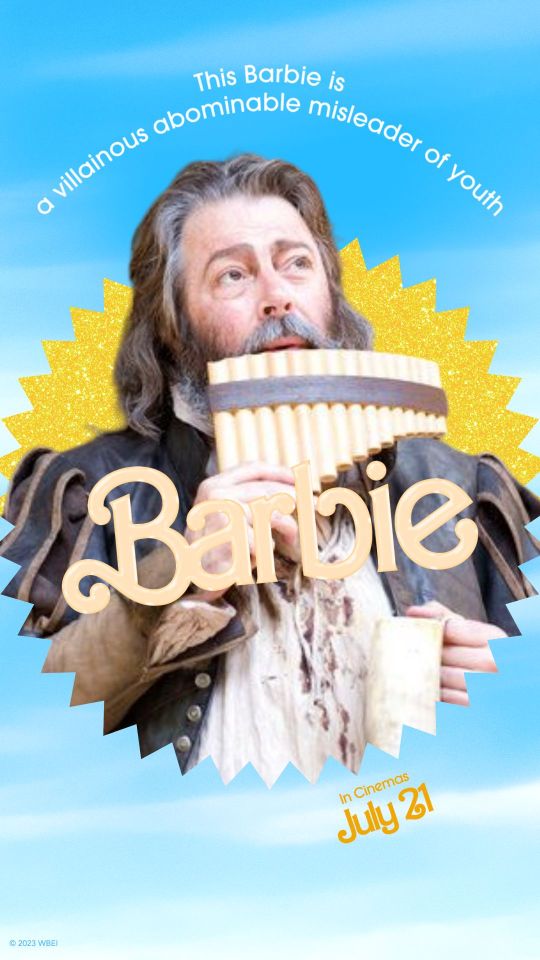

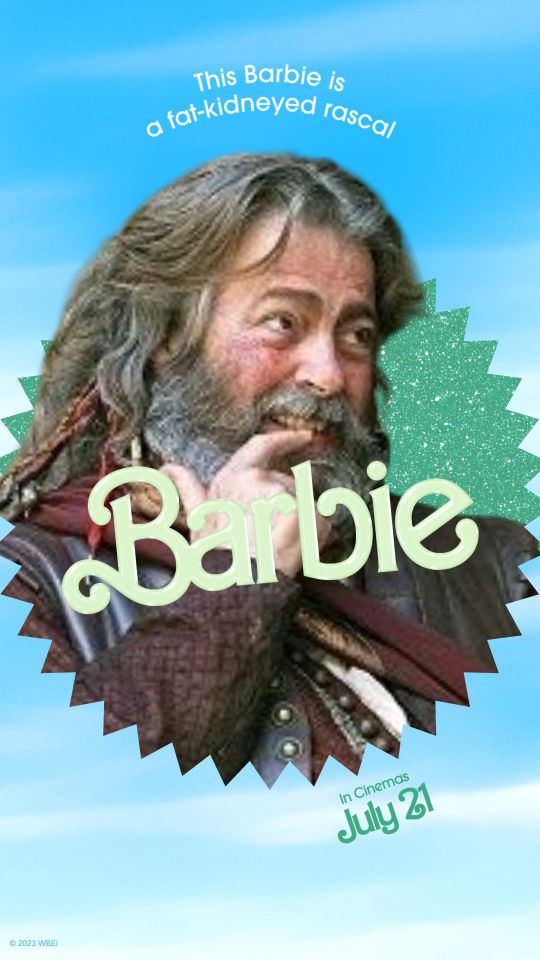

both of these prompts were in the same lesson

#duolingo#duo#falstaff#oscar#Spanish#learning spanish#learning#me#mary talks about stuff#shitpost#my posts

364 notes

·

View notes

Text

Metropolitan operas are NOT immune to my Uglydolls brainrot!

#uglydolls#ides of march#well hardly because i drew this back in november#but haha knives#tag citaaay#uglydolls lou#uglydolls mandy#uglydolls uglydog#uglydolls wage#uglydolls babo#uglydolls moxy#uglydolls ox#uglydolls lucky bat#falstaff#falstaff at the met#“how do i bring this back to uglydolls” is practically my motto!

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Brown for Falstaff, 1969

Theme Week: Black Celebrities 👑

#theme week#celebrity ads#james brown#beer#beverage#multicultural market#falstaff#1960s#1969#vintage advertising

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

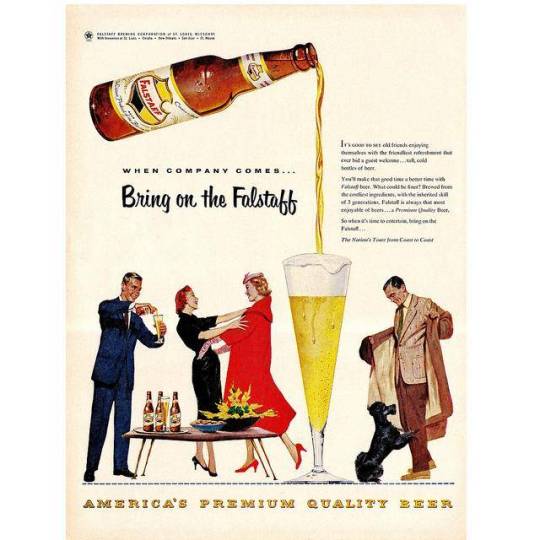

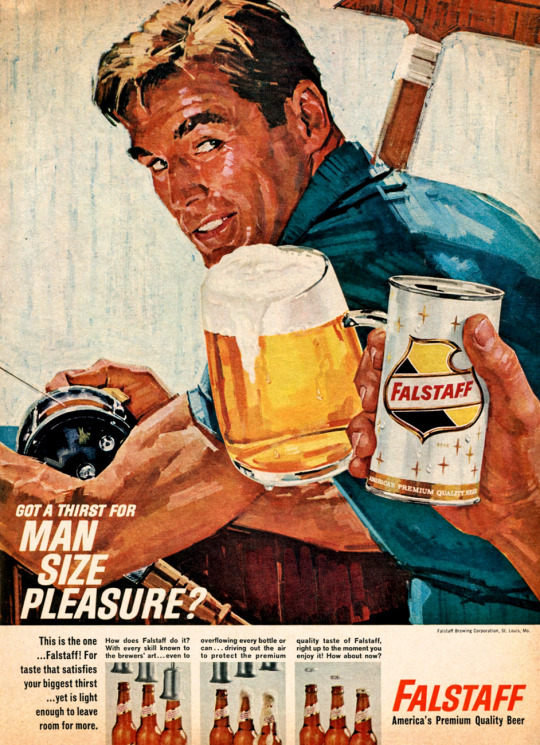

Thirst come. Thirst served. Falstaff Beer - 1967.

#vintage advertising#beer ads#beer advertising#beer#beer companies#falstaff#falstaff beer#brewers#brewing companies#alcohol#beer drinking#adult beverages#falstaff brewing corporation

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Falstaff is a professional criminal,” says the director, 37. “He’s not a sort of jolly, velvet-clad Santa figure. The very consistent picture you’re given of Falstaff is somebody who, when he was a bit younger, would have been really quite frightening. And the problem is he is now fat and old. So what is the retirement plan? How do you deal with the fact that you can no longer dominate physically and the younger lions are snapping at your heels?”

---

“It occurred to me that Henry IV’s only been on the throne for four or five years,” says Icke. “And this situation was never the plan. It’s not like Hal is Prince Harry. It’s not like he was born into [the royal] family.” Instead, we should understand that Hal has long had this gang of friends. “You’re watching a group of people who sort of knew where they were and who he was. Then suddenly his dad’s the king. And nobody’s quite worked out how to assimilate that, including him. There’s something in the whole pattern of the play about people caught between the past and the future, trying to maintain a status quo which is not maintainable . . . That’s what I see as being the DNA structure of the story.”

#shakespeare#william shakespeare#player kings#henry iv#rober icke#ian mckellen#falstaff#theater#theatre

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

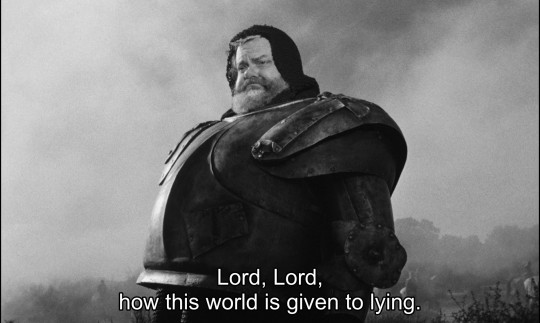

Chimes at Midnight (Orson Welles, 1965)

#chimes at midnight#campanadas a medianoche#orson welles#william shakespeare#falstaff#1965#cine español#spanish cinema#spanish film#spanish movies

81 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Henry IV, Part I (2012) dir. Richard Eyre

#The Hollow Crown#Henry IV#perioddramaedit#hiddlesedit#Tom Hiddleston#Prince Hal#Falstaff#Simon Russell Beale#Shakespeare#Medieval#tvedit#tvgifs#movies#gifs#my gifs

301 notes

·

View notes

Text

#opera#puccini#verdi#mozart#cherubini#classical music#operas#operablr#tosca#la boheme#falstaff#the magic flute#medea#rossini#the barber of seville#the marriage of figaro#cosi fan tutte

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

(sign up by August 4th to get your sass on)

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

OKAY grammatical feelings about Falstaff&Hal and Thursday&Morse

“I know thee not, old man.”

As any gnarled, middle-aged one-time English literature graduate knows, “thee/thou/thy/thine” is the now lost English equivalent of “tu/toi” etc. in French, and other informal+singular second person pronouns in any number of languages. In English we now use “you” for everyone, which was originally the formal and/or plural one.

It’s quite a recent loss, actually. As in, its continuing use in parts of rural Yorkshire etc. was still a thing in living memory. If you’ve ever watched The Last of the Summer Wine you may note that Compo uses “thee/thou” at times. But I digress.

[oh this got a bit long. ;-) Cut for length and spoilers for series 9 of Endeavour. Also content-warning for a bit of fatphobia in a quotation from Henry IV part 2.]

One of the things I find fascinating when reading Shakespeare and his contemporaries is when characters switch between “you” and “thou”. Sometimes it’s desperately moving - that moment when Benedick first uses “thou” for Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing is... fuck. Done right it’s an absolutely fizzing moment even now. That sudden intimacy.

I’m currently making a much more concerted effort to revive my French at the moment, and there was a moment in an episode of Dix Pour Cent I was watching earlier where a character suddenly switched from saying “vous” to “tu” to another character, and I went back to rewatch it with the French subtitles because I was sure I’d heard it, and I had. The English subtitles added a “darling” to give that moment its full impact. It was huge.

So to the Henry IV plays. Hal’s been using “thou” for Falstaff much of the two plays, and vice versa. Strictly speaking as Hal is the heir to the throne and Falstaff is just a knight (and a pretty rubbish one at that) Hal has the right to “thou” him in a higher-status-to-lower kind of a way anyway, but that’s not how he uses it, and Falstaff “thou”ing him, and Hal letting him? It shows the closeness of their friendship and quasi father-and-son relationship, however fraught it frequently is. It’s also worth noting that some of Falstaff’s friends also have been known to use “thou” for Hal (including Pistol).

But we’ve also known since early in Henry IV part 1 and *boy* do we continue to get hints, that once Hal is crowned, he’s going to chuck Falstaff and the others for good.

So here’s the newly-crowned King Henry V (formerly Hal, now King in this text which I just nabbed from the Folger library website) being greeted by Falstaff and Pistol. [NB: This is the bit with the fatphobia I warned for above]

* * * * * * * * *

[Enter the King and his train.]

FALSTAFF: God save thy Grace, King Hal, my royal Hal.

PISTOL: The heavens thee guard and keep, most royal

imp of fame!

FALSTAFF: God save thee, my sweet boy!

KING: My Lord Chief Justice, speak to that vain man.

CHIEF JUSTICE, to Falstaff: Have you your wits? Know you what ’tis you

speak?

FALSTAFF, to the King: My king, my Jove, I speak to thee, my heart!

KING: I know thee not, old man. Fall to thy prayers.

How ill white hairs becomes a fool and jester.

I have long dreamt of such a kind of man,

So surfeit-swelled, so old, and so profane;

But being awaked, I do despise my dream.

* * * * * * * *

And he continues in that vein for about another twenty lines, during which Falstaff’s heart completely breaks.

It’s usual for Hal/the King to not exactly be on happy form himself. Alex Hassell, in the RSC version with Antony Sher as Falstaff, pretty much delivers those lines as one enormous panic attack. He’s even more immediately devastated than Sher’s Falstaff, who seems to be fending off his misery with denial. Jamie Parker’s Hal in the Globe production with Roger Allam as Falstaff is slightly less broken but not much less; Allam’s Falstaff just fricking falls apart before our eyes.

(Darn actor allusions in Endeavour. [sniffs])

Anyway. This brings me to Morse.

Thursday isn’t Falstaff. Yes, he’s arguably a father figure for Morse, and loves him. And in this moment Morse is at least considering rejecting him once and for all, with good reason. But Falstaff’s a consistently terrible person (not for any of the reasons Hal gives in that desperately painful speech, I more mean things like cheerfully accepting bribes leading to the deaths in battle of impoverished men he was meant to be leading and barely being sorry about it); Thursday is a mostly good but flawed and traumatised person who has made a series of massive fuck-ups under extreme pressure. Rather different.

And Morse and Hal use that phrase “I know thee not old man” so differently. Hal can’t know Falstaff any more and be the king he wants to be. It’s an absolute rejection.

Morse quotes Hal but does so more literally: he doesn’t know Thursday any more. There’s the potential for rejection there, but mostly he’s feeling lost and wants Thursday to help him understand why he did what he did.

Both these pairs part permanently. But with Hal and Falstaff it’s entirely tragic; with Morse and Thursday more bittersweet, as in the end they do part as friends, still clearly loving each other.

But here also is the thing:-

Is Hal saying “I know thee not, old man” just because he has the right in the stupid classist society in which he lives to “thee” an elderly knight in some contempt because he’s the king? Or is he falling back on the habit of using “thee” for him? Or is he expressing an absolute contradiction in terms, deploying the informality of closeness? Of “I don’t know you, friend”.

Morse knows his Shakespeare, and I can’t believe that with his language skills he wouldn’t be aware of what “thee” means. And Morse isn’t Thursday’s boss let alone king, even if they’re no longer inspector and bagman.

So when Morse says “I know thee not, old man”... it’s absolutely that contradiction. Denying and acknowledging understanding and closeness in the same breath. It’s very Morse. It’s very them. Ow.

Oh. Here’s another thought:-

Within the timescale of Shakespeare’s history plays (which are rather more conflated than actual history), Falstaff’s dead within a year, specifically of the broken heart that Hal gives him in the scene I quote above. It’s reported early on in the play Henry V. You know, the one which Falstaff isn’t in, that follows Hal’s later career...

If Morse and Thursday hadn’t made up to the extent that they do... would the same thing have happened to Thursday? Would Morse have accidentally cursed him, really making him his Falstaff? :-/ I mean, if Thursday had been arrested then obviously he would have died soon after one way or another, I think that’s plain for various reasons. But I mean, if Morse had still protected Thursday but they had parted in the heat of the pain and bitterness Morse betrays in that line, without the softening and love that’s apparent in their final scene together? We’re talking about a show that does stray into fantasy at times, after all.

#itv endeavour#endeavour morse#fred thursday#endeavour morse & fred thursday#shakespeare#henry iv parts 1 and 2#henry iv part 1#henry iv part#hal#falstaff#dix pour cent#grammar#language#much ado about nothing#alex hassell#jamie parker#antony sher#roger allam#shaun evans#darn you russell lewis#singular they predates singular you#singular informal you anyway#i wish to add that one of my least appealing characteristics is how unfairly annoyed i get#when people are doing shakespearean or earlier pastiche and use thee wrongly#it's the equivalent of tu folks#singular and informal singular and informal#don't be thrown by the fact that it's still used in the lord's prayer in some churches today#i believe that using the informal singular for god (at least in christianity) is still pretty standard in multiple languages#but also: the fact that i find it so annoying when people get this wrong really is on me not them ;-)#endeavour spoilers

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Top 40 Most Popular Operas, Part 3 (#21 through #30)

A quick guide for newcomers to the genre, with links to online video recordings of complete performances, with English subtitles whenever possible.

Verdi's Il Trovatore

The second of Verdi's three great "middle period" tragedies (the other two being Rigoletto and La Traviata): a grand melodrama filled with famous melodies.

Studio film, 1957 (Mario del Monaco, Leyla Gencer, Ettore Bastianini, Fedora Barbieri; conducted by Fernando Previtali) (no subtitles; read the libretto in English translation here)

Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor

The most famous tragic opera in the bel canto style, based on Sir Walter Scott's novel The Bride of Lammermoor, and featuring opera's most famous "mad scene."

Studio film, 1971 (Anna Moffo, Lajos Kozma, Giulio Fioravanti, Paolo Washington; conducted by Carlo Felice Cillario)

Leoncavallo's Pagliacci

The most famous example of verismo opera: brutal Italian realism from the turn of the 20th century. Jealousy, adultery, and violence among a troupe of traveling clowns.

Feature film, 1983 (Plácido Domingo, Teresa Stratas, Juan Pons, Alberto Rinaldi; conducted by Georges Prêtre)

Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, Part VI

Mozart's Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio)

Mozart's comic Singspiel (German opera with spoken dialogue) set amid a Turkish harem. What it lacks in political correctness it makes up for in outstanding music.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, 1988 (Deon van der Walt, Inga Nielsen, Lillian Watson, Lars Magnusson, Kurt Moll, Oliver Tobias; conducted by Georg Solti) (click CC for subtitles)

Verdi's Un Ballo in Maschera

A Verdi tragedy of forbidden love and political intrigue, inspired by the assassination of King Gustav III of Sweden.

Leipzig Opera House, 2006 (Massimiliano Pisapia, Chiara Taigi, Franco Vassallo, Annamaria Chiuri, Eun Yee You; conducted by Riccardo Chailly) (click CC for subtitles)

Part I, Part II

Offenbach's Les Contes d'Hoffmann (The Tales of Hoffmann)

A half-comic, half-tragic fantasy opera based on the writings of E.T.A. Hoffmann, in which the author becomes the protagonist of his own stories of ill-fated love.

Opéra de Monte-Carlo, 2018 (Juan Diego Flórez, Olga Peretyatko, Nicolas Courjal, Sophie Marilley; conducted by Jacques Lacombe) (click CC and choose English in "Auto-translate" under "Settings" for subtitles)

Wagner's Der Fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman)

An early and particularly accessible work of Wagner, based on the legend of a phantom ship doomed to sail the seas until its captain finds a faithful bride.

Savolinna Opera, 1989 (Franz Grundheber, Hildegard Behrens, Ramiro Sirkiä, Matti Salminen; conducted by Leif Segerstam) (click CC for subtitles)

Mascagni's Cavalleria Rusticana

A one-act drama of adultery and scorned love among Sicilian peasants, second only to Pagliacci (with which it's often paired in a double bill) as the most famous verismo opera.

St. Petersburg Opera, 2012 (Fyodor Ataskevich, Iréne Theorin, Nikolay Kopylov, Ekaterina Egorova, Nina Romanova; conducted by Mikhail Tatarnikov)

Verdi's Falstaff

Verdi's final opera, a "mighty burst of laughter" based on Shakespeare's comedy The Merry Wives of Windsor.

Studio film, 1979 (Gabriel Bacquier, Karan Armstrong, Richard Stilwell, Marta Szirmay, Jutta Renate Ihloff, Max René Cosotti; conducted by Georg Solti) (click CC for subtitles)

Verdi's Otello (Othello)

Verdi's second-to-last great Shakespearean opera, based on the tragedy of the Moor of Venice.

Teatro alla Scala, 2001 (Plácido Domingo, Leo Nucci, Barbara Frittoli; conducted by Riccardo Muti)

#opera#top 40#21 through 30#video#complete performances#english subtitles#il trovatore#lucia di lammermoor#pagliacci#die entfuhrung aus dem serail#the abduction from the seraglio#un ballo in maschera#les contes d'hoffmann#the tales of hoffmann#der fliegende holländer#the flying dutchman#cavalleria rusticana#falstaff#otello

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Got a thirst for man size pleasure?

#vintage illustration#vintage advertising#beer#beer ads#falstaff beer#falstaff#adult beverages#falstaff brewing corporation

54 notes

·

View notes