#everything about the generals is insane and also has me on a chokehold

Note

I'm having trouble following Acxa's love life, so first she had an unrequited romance with Zethrid and now she's with Keith?

Okay let me be literal here - Acxa in show has no love life. Or at least, we have no explicit confirmation of a love life. All of these are headcanons based on what we know of the characters and what we can glean from the story told. And then extrapolating from there.

The idea behind zethacxa comes from certain interactions in the Grudge, specifically where Acxa tries to convince Zethrid to stop the hostage exchange with Keith. There, she promises that Zethrid could can and should change and if she does she can be "with me[Acxa], and Ezor."* In of itself Acxa says she cares for Zethrid, and Ezor too. But the interesting thing is that Acxa puts herself first. Before Ezor, who you know, is Zethrid's wife.** On one hand, this is meaningless, on the other hand, Acxa is letting out a Freudian slip - implicating that she is (or more accurately should) be a higher priority for Zethrid to change over her own wife.

It could also be cause Ezor left Zethrid on bad terms, and thus Zethrid and Ezor aren't talking (I mean, Zethrid is taking it out on Keith + Acxa instead of trying to talk to Ezor) so maybe Acxa operates on that logic. But if that is so, this means that somehow Acxa, who is responsible for blowing up half of Zethrid's face, is somehow in a better position to connect with her emotionally says a lot about everyone involved.They are so close you all. Either way, Acxa is measuring herself in an equal if not higher level than Ezor in importance for Zethrid, which imho, speaks volumes. And Zethrid also tells Acxa she's "too far gone" which is meaningless really, but it's the type of thing you'd tell someone whom you care for, if at least at one point.

Recall also that Ezor was supposed to have died as well, as one writer on the show admitted pre-s8 that Ezor was dead, but in response to backlash the undid Ezor's death. So in original canon, Zethrid was going to run away with Acxa, and lo and behold, at the end of the episode we have this:

Acxa has and will not give Zethrid any peace cause she cares enough for Zethrid to be with her until she gets better. Your ship could never.

But what does that have to do with past Zethacxa? For that, we look to past canon. Acxa and Zethrid always had a contentious relationship throughout the show. Both are quick fuses, but triggered by different things. Zethrid sought violent thrills, Acxa wants to stick to the plan. Acxa is pissy over incorrect information, Zethrid does not care. Zethrid plans for long-term self-sustainability, Acxa will stick to their current course in hopes of achieving political change. Anything Zethrid does sets Acxa off.

Conflict is a part of their dynamic and since s3 it's been foreshadowed that their arcs will go to a head this way. Now with that one line from the Grudge in mind, reading this animosity shifts slightly. It would be fun, if sometime before the events of the show, if they dated, broke off cause they were to quote Acxa "so full of hate and rage" and cannot carry a normal relationship (I mean, look how zethzor turn out by the Grudge, and Zethrid is older then), and then cause life hates them, they both get recruited by Lotor. Ironic. Their squabbling becomes exes drama. Zethrid is unphased by the shit Acxa pulls in s7 for ex, whereas Ezor took Acxa's leave as personal insult. If Zethrid is used to Acxa being Like That, it would make sense.

Alternatively, Acxa is very emotionally repressed, which given her whole thing with Keith, is a completely sound read of her.

So yeah that's the tea on Zethacxa.

With Keith, I don't really have to explain. Acxa hyper-fixated on him cause he saved her life (She was "born and bred in war" and every person was for themself, so Keith taking his time knowing she's the enemy to save her touched her personally.) and cause he has a freedom to achieve his plans/ideals in way Acxa could never imagine herself doing at that point of time (act 2). She hated him. She cannot let him die. From this, a more mature and self-actualized Acxa could develop an interest in him in act 3 and/or after. It doesn't have to be, nor did the writers want it by the time act 3 rolled around, but there's food there.

In other words - Zethacxa, break up, then kacxa. Or zethzoracxa polycule + Keith fourth wheel. Or very homoerotic intense Zethacxa friendship then kacxa. Or consider - Zethezoracxa but Acxa also has a thing with keith on the side. idk take your pick

*bear with me in that I don't have quick access to s7-8 cause it was never released in hard copy and I do not have Netflix. So a paraphrase from memory

** Yes they're married. To quote Avatar Korra - "You gotta deal with it!"

#d asks#Anonymous#Acxa#Zethrid#vld keith#zethacxa#kacxa#zethzor#vld#my headcanons#my meta#everything about the generals is insane and also has me on a chokehold

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

໒꒰ྀི´ ˘ ` ꒱ྀིა mimi’s fic recs !

in summary these are my fav fics that i’ve read recently and are living within the depths of my brain. this is just a way for my to show appreciation for the writers who had written them <3 please support their blogs and check out their other works as well!

please minors dni with the smut works. respect writers and their boundaries!!

f :: fluff / a :: angst / s :: smut

pretty girls make graves by @ijtaimes f

OBSESSED with this series!! the blend of the summer camp setting, the love triangle story, and the clever incorporation of horror elements?@)2)2) and the interactive storytelling it has with the outfit choices and other general choices?? ivy, cousin i love you and your sexy brain. i can’t get enough of it actually!

two peculiar swans by @astralnymphh f / s

WHEN I TELL YOU ALL I RAN LIKE THREE LAPS AND SAT IMMEDIATELY WHEN I SAW IT WAS POSTED. the writinggg!! so top tier! the dialogue, inner monologue how the story just flows so seamlessly?? i’m so excited for the rest of this series bro like aestra ate😋 HYPE IT UP YALL!!

loser!abby by @abbyscherry s

when i tell you all i profusely **** and ***** while reading both of the loser!abby works. like if i speak I would be deemed as insane, a mad woman it’s crazy. read them like bedtime stories before bed😭

cowboy!ellie + this by @catfern s

SAVE A HORSE RIDE A COWGIRL! COWBOY!ELLIE NATION RISEEEEE. these hcs had me foaming t the mouth like i need someone to hold me back before I ramble about how much I love these hcs and eat them up and will continue to eat up anything cowboy!ellie 😋

in for it by @brackishkittie s

ONE WORD. DIVINE. DELICIOUS. SCRUMPTIOUS. i could not stop smiling like a school girl while reading this it’s embarrassing actually. also vivian’s smau’s >>>> got me into the fandom actually

rockstar!ellie + this by @phantombriide s

i could write a thesis about how much i love this and rockstar!ellie works. like this is what i breathe, i eat, i consume everyday. it is the mantra i read to start my days. my daily reading to begin the day. god bless.

academic rival!abby by @beforeimdeceased f / s

ACADEMIC RIVALS CLENCHES FISTS. RAHHHHHHHHHHHH I LOVE IT I LOVE IT I LOVE ITTTTT. every bit of this series had me craving for more oml. like i need academic!rival abby in my bed immediately!

being pregnant with wife!abby by @bayasdulce f

baby fever has hit me once again what can i say?😞 I need wife!abby to take care of me so bad it’s getting sad at this point. I just this broke me down and worsened my baby fever (had me making a pinterest board and everything goodbye😞😞)

neighbour!ellie + this by @loaksky s / f

NEIGHBOUR!ELLIE NEIGHBOUR!ELLIE NEIGHBOUR!ELLIE MY FAV FAV FAV! i remember the influx of them on my dash and trust i was eating good 🍽️ both parts had me folding, giggling, smiling, swinging my feet everything and everything.

try it on by @moncherellie s

another work that got me into the fandom!! I remember reading this for the first time and hiding my face and giggling into my pillow and the audios lord i felt so giddy that night lmao😭

doctor!abby texts by @eightstarr f

doctor!abby has me in a chokehold like that’s my wife and mother of our three children everyone can leave pls and thanks😁 and i mean that with my whole chest. those texts are actual REAL evidence of what our convos look like you all can move (im joking pls don’t take what I’m saying seriously😭) I just am in love with everything zoe puts out because it’s so good and so dear and special to me

cutty love by @totheblood f

anything star puts out tbh >>>>> absolutely in love with cutty love actually! I am a whore for any fluff and PINNING (GIVE IT TEW ME). this is just so soft and sweet and it’s everything I need like uggggh. the audios too just chefs kiss love everything about it!

streamer!ellie hcs by @inf3ct3dd f

SIERRA’S HCS 🔛🔝 SO GOOD EATS EVERYTIME YALL like gen they all have made their home in my brain and I can’t go to bed without at least reading one of them before i hit the hay.

knight!ellie by @heavenbloom f

FIRSTLY written so beautifully?&* i love everything about this and i tend to go back to this work when I’m in need of a fluff fix! I absolutely adore how everything is written yes I’m reiterating my point because ‘green eyes thirsty for the well that was your beauty.’ LIKE WORLD STOP. ARE YOU SEEING THIS?? ‘she was utterly dedicated to you, body and soul, and she would be by your side until her very last breath. it was a fierceness, this love that consumed her, and it was all yours.’ LIKE WTF

partition by @whore4abby s

reserving my *clears throat* thoughts for now but just know * **** **** *** *** ***** **** * **** ***** *********!!! 😁😁😁 everyone should read this ASAP!

sun don’t set by @hier--soir f

another heavenly piece omg!! so in love with the writing in here oh my god. it’s so soft and sweet and it just felt like a warm hug on a cold winters day i just. please read this!!

you love it when i play with you by @ourautumn86 s

i think i like passed out and had three nosebleeds because of this. i think about this more than i should. I think about in the morning, throughout the day and night. my daily read at this point like it’s just sooooo😋😋😵💫😵💫😵💫😵💫

my love mine all mine by @doepretty f

this one is special to me too like. for one the writing is so beautiful and it made me shed a tear and secondly I melted into a puddle like i want Abby so bad I’m going to be sick.

#🎀.favs#ellie williams#ellie williams x reader#ellie x reader#ellie tlou#ellie williams x you#ellie the last of us#ellie x fem reader#the last of us#tlou abby#abby x reader smut#abby smut#abby headcanons#fic recs#abby anderson fanfic#abby anderson fluff#abby anderson fic

602 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Top 9 albums of 2023

tagged by @mysterygrl20 tysm <3

my taste in music is kind of all over the place so prepare yourself for a wild ride, although I also listen to a lot of kpop (I've kinda been slacking on keeping up with releases over the past year tho oops) and we definitely have some overlap in favorite albums

I apologize in advance for how long this post is going to become but you're really opening the floodgates by letting me talk about music lol

(it's been a very dry year for my favorite metal bands or this list would've been even more chaotic lmao)

1) Dear Insanity... by DPR Ian

while I struggled to rank most of these, there was absolutely no question about my #1 album of the year. I only just discovered DPR Ian in 2023 and he very quickly became my favorite artist ever. you might have even seen me talk about this album an unhealthy amount of times already lol. he's just such an insanely good artist and every single song on this album is just soooo damn good.

part of why I love him so much is also the story he tells throughout his music videos and just how insanely good all of his MVs look and how well the visuals fit the music so I feel obligated to link the MV to my favorite song off this album:

(some flashing lights in this one, folks, be warned)

youtube

2) The World Ep.2: Outlaw by Ateez

everything Ateez releases is immediately getting added to my favorites, what can I say. I didn't have the money to go to their 2023 tour but I did see them live in 2022... absolutely worth the one and only time I ever caught corona. not a single bad song on this album, they're all absolute bangers.

3) Take Me Back To Eden by Sleep Token

I only just discovered Sleep Token in 2023 but I absolutely fell in love with this entire album and their style in general. almost got to see them live but then I ended up getting surgery on the exact day of their concert... :')

4) OO-LI by Woodz

I am a Woodz stan first and a human second. I'm convinced this man is incapable of releasing bad music, everything he does is just so damn good and I love how he explores a bunch of different genres while still making all of his music just sound like him y'know

also honorable mention to Amnesia which is only a single album so it didn't make the list but if you like more eerie stuff and the general vibe of his music, definitely check it out, I love it so much

5) On My Youth by WayV

WayV will forever have me in a chokehold. they've been my favorite NCT unit since their debut and honestly also the only unit I managed to properly keep up with over the last year ashgasj. I just really love their style of music and how they've actually been sticking to it

6) The Name Chapter: Temptation by TXT

It's truly been a TXT kinda year for me, I've been listening to them a lot. there aren't many songs on this album but I still love it so so much, all of the songs are great and Sugar Rush Ride is such a unique title track

7) Dark Blood by Enhypen

honestly Enhypen are part of the reason why I might have to update my top 3 kpop groups to a top 5 lol. all of their albums so far have been great and this one was no different, I still listen to a lot of the songs on it on repeat

8) RUSH! (Are U Coming?) by Måneskin

well what can I say, Måneskin have had me in a chokehold ever since they won the Eurovision and I actually got to see them live in 2023! drove all the way over to Berlin for them and everything, great album with great songs. I love both their more rock-ish songs and their slower songs and this album has a great mix of both (although I wish there would've been some more Italian songs on here)

9) MONO by K.Flay

K.Flay has been one of my more underrated faves for a couple years by now and I'll take any chance to gush about her music. there's just something very unique about K.Flay's music and this album certainly didn't disappoint. honestly, the only reason why I ended up putting this one on the "last" place is that I haven't listened to it as much as the other albums on this list

Honorable mentions!

bc once I start talking about music, I just simply can not stop at only 9 albums and this list isn't quite chaotic enough yet to properly describe my taste in music lmao

ODD-VENTURE by MCND

this is a rather recent one so I haven't listened to it enough for it to make the list, but I love everything MCND put out and this is definitely also a great album! (plus the title track is yeehaw kpop which is incredibly creative of them and I didn't know I needed that in my life)

HAPPYPILLS by Utsu-P

and this is where I expose the true chaotic nature of my taste in music lmao. Utsu-P's music is the perfect clash of world's between teen-me's obession with vocaloid and current-me's love for metal. I didn't include this album bc I still haven't gotten around to listening to all of it, but the songs that I did listen to, I absolutely loved

Phantomime by Ghost

oh you thought you made it through an entire post of me talking about music without mentioning Ghost? Hah, fool. jokes aside, this is an album full of cover songs so I didn't include it but it's still full of bangers. I reached audio cap now but I'll include their Jesus He Knows Me cover bc this was an absolute treat to witness live:

youtube

if you've made it this far without getting whiplash: congrats!

tagging (as always, no pressure, feel free to ignore this): @negrowhat @fallsouthwinter @spicypussywave @thisisworsethanitlookslike @supanuts @buddhamethods @alienwlw and anyone else who wants to do it!

#the lack of skz is only bc i still have not managed to listen to the full albums i'm-#i've been slacking on kpop releases so bad this past year it's ridiculous lol#tag game#tagged#music#rae's music rambles#Youtube#Spotify

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

👁️👄👁️

I'm alive, sorry I fell off the face of the earth for a few days there (I was unwell - new anxiety meds and all that jazz)

BUT!! I have much to say, both about your new fic and obviously one of the older ones, so here's an extremely belated / extended ART&RCSW <33

Firstly, Maelstrom was incredible, it changed the way I live my life

I don't even watch Trigun Stampede but good lord did you get me hooked on the characters - not to mention, a good poly fic is always the way to my heart

The twist of the secret bastard brothers?? Incredible. Delicious. Amazing. And the not so subtle hatred they have for their father?? The fact that the only good thing to come from him was their darling sister?? My gosh, you've got me wrapped around your finger Rhi

Though I must admit, the whole reveal and the part where reader is being lead to the throne room gave me anxiety - you always manage to surprise me with the way you set things up, and I mean that in the best way possible

I can't say anything about the characterisation of Vash and Knives because I don't watch the show, but I imagine that as with everyone else, you've done an amazing job

Also the sense of hopelessness at the end?? Because like, there's literally no escape - the best type of ending in my professional opinion

Next up on the agenda, we have a fic (series??) that I know you're not particularly fond of, but I absolutely love

Through the cold, I'll find my way back to you, your Hawks / Dabi soulmate fic - it has me in a fucking chokehold

It's literally everything I love in a fic - soulmates, poly relationship, yandere, it's just amazing

The slight sprinkle of angst kinda feels like a punch to the gut, but in a satisfying way - not to mention, the fact that Natsuo still keeps in touch with the reader even though they don't really have a connection aside from Touya kills me, he's so sweet

And poor Keigo (he's insane but I do not care <33)

The way my stomach drops when the reader realises that she has another soulmate will never not be a great feeling, but the way she knows instinctively that something is missing because Dabi isn't there really is painful

Like I said, I know you've said you don't really like the series, but I'm here to reassure you, I loved it, so rest assured, the hard work didn't go down the drain <33

I'm also really sorry for disappearing for like two or three weeks :// But I'm back now (??)

Anyway, I hope you've been well, drinking water and sleeping and whatnot <33

See you next week Rhi (I hope??) Lol :))

BBY I MISSED YOU <33

i hope ur doing okay, i am sending you all the forehead smooches and love!!

ahh but this ask is so nice!! honestly i was so worried about posting maelstrom cuz it's a new fandom for both me and sort of in general – i know the manga and old anime have been around for a while, but for most people it's new – and i wasn't sure if people were actually going to read it

turns out you did anyway, not knowing any of the characters vhgfjdksjdhfjdks it's always such a huge compliment when that happens. it's actually how i found my way first to bnha and then to haikyuu so, yeah, it makes me happy to see it's the same for you guys

as for through the cold... hoo boy. i did have big plans for that one, and every month or so there's a part of me that wants to either delete part 2 and start again, or delete the entire thing and start again, with better execution this time. i may not be as in love with bnha as i used to be, but hawks and touya, and that particular storyline (i am if nothing else a sucker from the soulmate trope gone wrong)

but also... the part i hate about series, and one of my biggest gripes as a writer is when there's a demand for part 2's and 3's but then it's crickets in the notes. part 2 kinda flopped and idk if it was because it wasn't great or if people just couldn't be bothered to leave a response, so while i do occasionally have the motivation to continue it i don't know if it's actually worth while or if anyone (aside from you haha) would be into it. but then i think about all that delicious angst and keigo and touya being jealous assholes and... hmmmm.... vghfjdkjhvfjdks

in any case, i'm glad you liked it and it was very sweet of you to send this ask and i adore you.

also, pls take care of yourself, and don't apologise for taking the time you need. i, of course, live for these asks and seeing you in my notes, but it's never a necessity. your mental/physical health always comes first <33

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Give me what is considered a very unpopular opinion that you actually like about bro.

What about popular one that you hate?

Also do you think he would be the type to drink whatever unholy concoction of sugar and alcohol and caffeine you put in front of him without any hesitation?

my ass that hasn't stepped into the fandom since 201X and has no idea what is and isn't popular regarding bro outside of the (bro)ad strokes: uhhh

this is more of a general train a thought thing but like. people are so quick to scrutinise literally everything he does but he's just some dude to me... and really that's what should make his actions sting that much worse. like ok he's insane yeah but he wasn't forcing dave to be a baby DJ or he'd be worthless, he was doing that because he was sharing his interest with the little guy, dredging up the bottom of the barrel of what used to be his genuine self - much like that one really good analysis of rose & mom & roxy mentioned, interests are genuine and shared between beta / alpha selves. like yeah, dave was put into the strider mold to be a Cool Kid, but he was entirely free to develop his own interests once he got old enough - interests that bro entertained if not outright supported. also people making bro keeping track of dave's blogs & comics something controlling and sinister when like. buddy who do you think is paying for those. he is literally just keeping up with dave in the bullshit distanced cool dude who shows no earnest emotions way that he knows - watching from a distance and then bringing it up at a later date to show that he (kinda maybe?) cares... at least to make his horrible life lessons that much more personalized and traumatising.

as for something popular that i hate this is gonna be hard to describe. but people who make him too clean in a way? i spin him around in my head because he's a horrible person but like. he's a person. he's not holding dave in a chokehold 24/7 but he's also not the kinda guy to audibly admit he's proud of him. he's in the muddy grays in-between the two extremes and extremely turbulently going from one to the other because he is aggressively mentally ill and entirely unchecked. he cares for dave, he wishes he was never spawned, he'd do anything for the lil guy, he hates that dave's the player, he'll do anything to see dave succeed, he literally dies for him, he has zero regrets as to how he treated him because he's incapable of genuine introspection when his sense of self has always been paraded in front of him by lil cal. in his mind everything he did, he did for dave, sprinkled in with the bullying and mind games that would only come to the mind of an older brother figure who's completely off his rocker and incapable of being self aware / feeling empathy without literally having it explained to him.

as for drinks; he'd not appreciate drinks that are too sweet or fruity, calling them girly, but he'd still down those mother fuckers in one go as if to prove he's too strong for them - only to get shit faced all the same. roxx loved teasing him about it, but he just in general isn't a fan of sweet things. rots your teeth, yknow. as for alcohol mixed w energy drinks. yeah. been there done that. a couple times too many, maybe, considering he's prone to mania but hey when he finally conkers out he's out cold to the point dave might have gone and checked to see if he was still breathing. you know. because he has such a normal sleep schedule that seeing him still is akin to him being dead.

#🧢#💿#🆒#📩#i had to start and stop this so many times because people kept interrupting me i refuse to read it over. you either get it or you get it.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

JJK manga spoilers at the undercut! long tanget at the undercut!

(Continued for the storytelling!) Okay so 👀 in a very tragic turn of events where Gojo tries to Yuta-style his way out of the Prison Realm, but it goes oopsies and he's actually 'dead' dead and MC stares in disbelief at what she's seeing because this can NOT be real, oh but I'm sorry it is. And this is the one thing, the image of his best friend lying dead in front of him, that gives Geto much longer control over his body and he crawls over to Gojo and his hands are shaking.

(Part 2) He's clawing at himself to wake up from this nightmare to no avail. Nothing will change what's happened and MC flips, kicks him in the face, grabs him by his clothes and slams him onto the nearest surface yelling about how "is this what it takes for you to finally snap out of it?!" why couldn't he have done it sooner??! MC is filled with rage. That's not Geto. She knows it's not Geto, but she's just so angry from her warped sorrow and tells him that even though he changed so much.

(Part 3) and did all those things as a Curse User, she still grieved for him. She missed him so freaking much, dreaming of what could be with all of them together. She hated the fact he had to die because of those actions, and now??? What good is snapping out of it now when she knows she'll have to kill him again because the real Geto already died once before and once she ends the life of whatever is controlling him, the remnents of Suguru will die out again as well. Shes losing them both again.

(Part 4) "What went wrong those 11 years ago??!" They're both such idiots, she thinks, crying furiously. Stupid mistakes, stupid actions. What was Satoru thinking? Why would he try something like that? Why couldn't they have communicated better, why did all those little things have to add up until they got to this point, something that never should've happened? The pain and the sorrow, the hammering of her heart and difficulty breathing is too much. "I can't live in a world without Satoru."

(Part 5) And Suguru looks so sad, and he tries to tell her it's the real him- she knows, tells her that he's sorry. Tries to crawl over back to Satoru's corpse, MC tells him bluntly that he better not lose control as she lets him while keeping a careful eye on him, she won't let Satoru get hurt if the Thing takes over again. She can see in between his words and mumbling to his friend's corpse that he's fighting, and fighting even more once he tells her the name of what's controlling him.

(Part 6) "Kenjaku." He pleads with her, crying out her name to listen as he says. The Thing was after the Six Eyes, with Satoru dead another will be born, but a baby cannot replace The Strongest, the Honored One, (oh how she knows, Satoru was all she had left.) What he asks of her, is impossible. She cannot defile his body in such a way. To take out his eyes, replace her own with them. Her body is compatible to different cursed energies, like moldable clay, and with Shoko's healing.

(Part 7) the transplant has a chance of working flawlessly. She hates it. Satoru is worth more than his stupid powers, but Suguru is trying hard to fight Kenjaku twisting his tongue and silencing his voice, he's croaking out desperately, that if she wants everyone to live, for all her friends to live and defeat The Thing then she must. The Six Eyes have always been its worst enemy. She cannot let that power die out when the world needs it for salvation. She agrees.

(Part 8) She apologies. For kicking him in the face. It's fine, Suguru says, he's forgives it, and he knows it was somewhat deserved. Its time now, they know what needs to be done. It's over quick and easy, one shot through his heart, and not a trace of blood drops to the ground, the wound seared shut from the heat of her attack. The only traces of Suguru Geto that remains on this earth are the bloodstains miles away from here in Shibuya, at the Tomb of the Star, where destiny was destroyed.

(Part 9) Before she ends it all, she makes a wish. If they were to be reborn again, it'd be nice if they could find each other once more and make sure everything goes right. Suguru had smiled when she let her technique go. He too, had promises to keep. "Say hello to Satoru in heaven for me." She forces a smile on her own face, tears having not yet dried. No use holding onto her rage as she takes away Suguru's life. That shouldn't be the last thing he sees.

(Part 10) She'll have to comfort herself with this, that they were at least together now. She hopes they can rest peacefully, it'll be the only kind thing given to them at this point. It'd been far too long and they deserve that rest so long overdue from the harsh tales their birth had woven into them. (Reaching for Gojo's eyes feels like betrayal. Note: I want that one line to be a total opposite of another line earlier on in their fight where she says, "Well then, come dance with me in hell!")

(Part 11) when fake!Geto probs said something about sending her there as a farewell or goodbye or whatever, idk haven't worked that bit out yet lol. It's so I can contrast the change in her negative mindset to being much calmer, to think of something more positive for those two. That 'that's' where they'll be. Suguru isn't the kind of evil Kenjaku is. It's the final acknowledgement and fully giving up her hatred.) Omg this is so long, I'm sorry. I hope its enjoyable at least??? *hearts and hugs*

Lol whoops, I forgot to mention but MC also kinda slaps Suguru after kicking him in the face and it's that moment of being stunned that lets her grab him, it's good that the "real" Geto doesn't fight back because geez Kenjaku controlling him is way too strong, a long-distance fighter and a great martial artist. At least then it's easier to get him in a chokehold and try to rip off the stitches hiding that cowardly brain.

Idk why but I think it’s cause I have no idea who your MC is that I am not really following lol. And I am not that great with canon material, but I am sure that Gege has mentioned that there isn’t much of Suguru left in his body. Cause even though his technique and his heart and all is there, I think the brain (or Kenjaku)’s power is to not only take over the host, but also shape themselves around the core of the host’s spirit. So in general it’s kinda like Mahito?

But I guess I enjoyed it? Idk it’s a lot, I can’t process much of it because I think I am too in the dark of your MC, but I also enjoy the entire thing? Idk, I am a mess of how I should feel cause I can barely process the entire Shibuya Arch lol.

Also does that mean that the Gojo clan does not have a head anymore? How is that going to work? Or are they going to take her in as the new head? Wouldn’t the world’s axis shift too cause because she isn’t the original owner of the Six Eyes. She doesn’t know how to use his Technique - I am assuming she is a no name before she took his eyes. Doesn’t that mean that open up an entire new Arch in your timeline as it is?

Honestly, now that I look over it again, there is so much going on that I am surprised that there are people out there with such rainbow brains to be able to think of something as insane as this. There is so much detail that it kinda blows my mind lol.

But I love that you shared so much cool ideas with me, anon! if you ever write this, do tag me so that i can read. or tag me in your entire MC timeline - I would love to explore this even more!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inktober day one: Birthday

Prompt list by @totallyevan, here ;3c

below the cut bc long

“Happy Birthday to us!” Klaus cheers loudly, passing out the party hats that Five suspects he’d stolen from the dollar store. Klaus himself is wearing two, having explained unprompted that clearly he was wearing Ben’s hat for him as well.

“I’m not wearing this.” Diego tells them all severely, glaring at the bright paper cone. “Absolutely not.”

“C’mon, D.” Klaus rolls his eyes, “Be a good sport!”

He’s inching closer to Five as he says this, causing the boy to squint suspiciously out of the corner of his eye. The fact that Klaus is gripping another party hat in his hands gave more than the necessary hint as to what he was up to.

“If you even try,” Five informs his brother serenely, making Klaus freeze in place, “Not even the buzzards will find your body.”

“Five,” Vanya says admonishingly. He gives his sister a scowl and crosses his arms. He’s not going to bow to this idiocy just because his favorite sister is looking at him like that. He’s not.

“If Diego doesn’t have to wear one then I don’t have to, either.” Five declares, and as one the entire family swings around to stare at Diego, who pinks at the attention and hunches his shoulders defensively.

“If I have to wear one, everyone has to wear one.” Luther scowls, and he really does look ridiculous with the tiny party hat against his big body. However, this input has the opposite effect of getting Diego to fall in line and he tosses the hat onto the table.

“Everyone has to wear one anyway, because it’s our birthday! Birthdays! We have to celebrate!” Klaus exclaims, leaning so far over the table that it’s a very real possibility that he’s going to tip over and crash. “We’re all together! For the first time in ages! Together birthday bash!”

“It’s not even your birthday.” Five’s voice cuts through the noise, making everyone blink and turn to him. Not expecting the attention, Five takes a small step back. “I mean - Klaus was in Vietnam for ten months. Technically his 30th birthday was… ten months ago. His 31st is in two months. It’s not today.”

Klaus blinks as the rest of the family turns towards him. “Hey hey, that’s not fair. That’s not what a birthday is! A birthday is the day you were born, and I’ll thank you all to remember that I was born on October 1st just like the rest of you.”

“A birthday is the celebration of surviving another 365 days,” Five rebuffs, “Otherwise people born on leap years would be legally toddlers their whole lives.”

“Is it the days that your mind has gone through or your body?” Vanya interrupts, looking contemplative. “Because you ended up in your younger body, Five. Does that make this your 59th birthday or your 14th?”

Five sputters with incoherent rage, as he always does when his physical vs. mental age is brought up, but the other siblings are picking up that thread now.

“If he has the body he left in,” Allison muses aloud, “And he left in November, right? We’d only just turned thirteen, right? So from April 1st to now is what, six months? So wouldn’t Five still be thirteen?”

“I am not thirteen!” Five hollers and is generally ignored by the rest of the family. As he always is when he tries to protest against being treated like a child.

“Your body is still thirteen.” Luther attempts to soothe, “We know you’re not actually thirteen.”

Five does not appreciate this. Five has never appreciated this argument. No one is sure why Luther thinks it might work this time when the evidence against it is so strong.

“I think everyone is getting off topic right now!” Klaus yells, slamming his hands on the table enthusiastically, right before he picks them up and rubs at them with a small whimper. Probably not his best idea, but at this point he’s committed. “What Five was really saying - is that I’m totally the oldest sibling now and by rules of oldest sibling I get to make everyone wear a party hat.”

There’s a short pause as they digest this information, and then absolute chaos as everyone immediately starts protesting as one.

“Absolutely not,” Allison is saying, shaking her head and looking vaguely horrified at the fact that technically Klaus is the oldest of them.

Luther and Diego seem to be attempting to compete with one another with sheer volume of their arguments against Klaus’s claims to the point that no one can understand either of them.

“I’m the oldest!” Five howls in outrage, slamming his own hands against the poor table and not even flinching. It’s much more impressive than Klaus’s earlier similar gesture.

“Nuh uh!” Klaus shoots back, very maturely. “In body! I have the body of an almost-32-year-old! Everyone else is 30, and you’re 13! That makes me the oldest!”

“He has a point.” Vanya, the only sibling still sitting calmly in her party hat, shrugs. Since coming off her meds she’s kind of become a little shit - giving the illusion of a neutral party while absolutely stirring shit within the family. Everyone figures it’s only fair after everything that’s happened though.

“No he doesn’t!” Five looks a little bit like he’s going to hurl himself across the table and physically fight Klaus, just that tiny mad gleam in his eyes, “I did not spend fucking decades in the apocalypse to be delegated to youngest siblings because of a fucking math error!”

“Well maybe ya shouldn’t have made the error!” Klaus shoots back, sniffing and crossing his arms like he’s the offended party in this discussion.

Five makes a strangled noise and then does launch himself across the table. Klaus yelps and stumbles backwards, tripping over his own two feet (albeit helped somewhat by the long rainbow feather boa that also looks like it came from dollar tree) and lands with a thump on his ass. He only has a few seconds before Five is making a grab for him and he starts outright screaming.

“Five!” Allison shouts, which Luther takes as his cue to at least try and resolve this situation. Of course, he does it in the worst possible way by scooping Five up by his armpits and physically trying to yank him off of Klaus.

This might have worked, if Five didn’t have a death grip on the brother he was currently most furious with. As it is, Klaus is yanked up alongside Five. Klaus was still screaming.

“What is going on in here?” A voice cuts through the insanity and everyone freezes.

Grace stands in the doorway with a cake in her hands, blinking at the absolutely chaotic scene before her.

Luther is halfway through folding in pain because one of Five’s sneakered feet is buried in his gut, while Five holds Klaus in a chokehold and refuses to let go, and Diego has come around and has his arms on Klaus’s arm to try and yank him away from their feral brother.

Allison is standing with her hands on her hips, mouth snapped shut where it was previously yelling at everyone, and Vanya is balancing precariously on two legs on the chair that she hasn’t yet moved from as she contemplates the insanity involved with being included as a member of the family.

“Hi mom.” Vanya offers into the silence.

“It’s Klaus’s fault!” Five bursts out before Grace can even answer.

“Is not!” Klaus shoots back, slapping at Five’s arm that is still wrapped around his neck.

“Is too!” Five shoots back, tightening his grip and making Klaus yell. This almost sparks into an entirely new scuffle as Diego starts to move and Luther unfolds - but thankfully they are interrupted.

“Boys,” Grace tuts, looking almost disappointed. “Can you not all try to get along, on today of all days?”

That makes Five finally release his grip on Klaus. Unfortunately, Klaus was not expecting this and shoots into Diego, making them both tumble to the floor. Luther was also not expecting the sudden loss of weight and Five shoots up in his arms like a jack in the box and is very nearly tossed across the room, and would have been if Luther’s grip had been any less secure.

“Five!” Diego snaps, hauling himself to his feet and bringing Klaus along for the ride. Klaus now only has one party hat perched precariously on his head, the other one having vanished to places unknown. His remaining one looks like it has seen better days.

“Diego.” Five shoots back, mockingly.

“Boys.” Grace says firmly, making them both look abashed. “Luther, put Five down. Diego, Klaus, why don’t you two take a seat. You can all tell me what this was about.”

“Klaus was trying to get us to wear his stupid party hats.” Five offers as soon as his feet hit the ground and he pulls out a chair.

“They’re not stupid!” Klaus squawks in outrage, “And Five said it’s not my birthday!”

“It’s not my fault you time traveled that first time! You did that all by yourself.” Five shoots back, leaning forward to better engage in the argument, but pauses when he sees the looks Grace is shooting all of them. Disappointed. He slumps back down in his chair and crosses his arms resentfully.

“Klaus,” Grace says gently, “Why are the party hats so important to you?”

Klaus crosses his arms as well, looking at the table. “‘Cause it’s our birthday. An’ it’s our first birthday together for seventeen years. I just wanted it to be special, and we never got proper birthdays as kids.”

The table is silent for a minute before Diego sighs loudly and snatches up his previously discarded party hat and jams it on his head. “Happy now?” He demands gruffly.

Klaus gives him a watery smile in response.

“Five?” Grace asks, “Why is it so important for you to not wear the party hat?”

Five shuffles in his seat, not making eye contact. “‘S childish and dumb.” He mutters under his breath, but the silence at the table means that it’s heard loud and clear.

“Why?” Grace asks again, gently.

“I’m not a child.” Five says, scowling at the surface of the table, “The others all want to - I dunno, vicariously live their childhoods through me or whatever but they don’t care that it’s not what I want. I’m not a kid and I don’t want to be childish.”

“Everyone else is wearing the dumb hats and none of us are kids,” Diego points out, rolling his eyes. The other faces at the table look a tiny bit more thoughtful. Allison’s is going through some interesting mental gymnastics in the corner.

“None of you look like kids. It doesn’t matter if you’re childish or whatever because no one is going to mistake you guys for dumb kids.” Five scowls.

“But,” Grace interrupts, raising a finger, “Everyone here is well aware that your physical body does not match your mental state. So no one here would mistake you for a real child for partaking.”

“Except they do!” Five protests, voice cracking embarrassingly. But he forges on regardless, “They’re constantly treating me like a little kid! And every time we go out and someone says something they all tease me like it’s all one big joke to them, but this is my life! This is reality for me, and it sucks!”

Deafening silence follows this outburst.

“Five…” Allison says, but the sentence doesn’t go anywhere.

“You don’t have to wear the party hat.” Klaus offers after another beat of silence.

“It’s not about the stupid hat at this point, Klaus.” Diego hisses, elbowing Klaus none too gently.

Grace holds up a hand and everyone quiets down. “Five,” She says, “Is it just the hat, or is it something else about all this that makes you feel childish.”

Five’s shoulders are up around his ears and he hunches down in his chair even further. “I dunno. The hat yeah. And the decorations. And the stupid paper plates. And the cake. It’s all just… stupid.”

“The birthday party itself is childish.” Grace clarifies.

“Yeah I guess.” Five shrugs. “I mean, I haven’t celebrated my birthday since I was…”

“Since you were thirteen.” Grace supplies softly.

Five can only shrug again. “I mean, I didn’t exactly know when I landed - only that it was after April 1st I guess. I only really counted like, summers and winters? Instead of months that is. Because there weren’t months or days or whatever anymore. So it’s not like I knew whenever October 1st rolled around.”

“And the Commission?” Grace asks.

“The Commission was - ” Five frowns to himself, “It was timeless. There weren’t really seasons? And when I went on missions there were seasons but there weren’t constant seasons, or months, or days, or anything. I’d have a missions one day where it snowed and the next week I was sent somewhere in the height of summer. It was weird. I think they do it on purpose though, to keep everyone off balance.”

“So this is your first real October 1st in a very long time.” Grace nods sympathetically. “So, do you know what an adult birthday party looks like?”

Five pauses, frown deepening. “No one in the Commission celebrated their birthdays and they were adults.”

“But you’ve mentioned you didn’t socialize within the Commission,” Grace points out, “So isn’t it possible that there were birthday parties you just didn’t get invited to?”

“I guess.” Five concedes.

Grace presses on, “So isn’t it possible that all of this,” She gestures at the paper plates and the party hats and the cake she set down with the delicately frosted letters, “Is in fact typical of an adult birthday party and that key features between child and adult birthday parties don’t change?”

“Diego didn’t want to wear a hat.” Five maintains his stance.

Grace tilts her head, “Is Diego your role model for adult life, Five?”

Five instantly is sputtering out denials and the others are laughing into their hands. Diego, for his part, looks incredibly offended by the direction this conversation has taken.

“If you had to pick one of your siblings to say who was the most adult,” Grace continues on easily, “Who would it be?”

Five actually looks thoughtful at the question. He looks up in thought before finally offering, “Vanya, I guess? She actually has a steady job. And a home. And she pays taxes.”

“Is Vanya wearing a hat?”

Vanya is indeed still wearing her bright and colorful birthday hat.

There’s a beat of silence, before - “Fine, I’ll wear the stupid hat. But if anyone says the words cute or adorable or young man or anything along those lines then I can’t be held responsible for my actions.”

“No one is going to treat you like a child today, Five.” Grace assures him, giving the rest of the family a look which there’s no arguing with. They sheepishly nod their heads in agreement, even though there was almost certainly teasing planned at the beginning of the day.

Grace smiles benignly at her children and claps her hands, “In that case, it’s time for the cake! I have the candles here, though I’m afraid since there’s only one cake you’ll all simply have to blow out the candles together.”

The kids gather round as Grace dims the lights to make the fire of the candles stand out all the more brightly. Mercifully, the group as a whole elects to skip the birthday song since it’s pretty much everyone’s birthday.

“Make a wish!” Grace commands, stepping back. Without needing further prompting, the group leans forward to blow, and the candles flicker out as quickly as they were lit.

Diego brings out a knife and starts a debate to the side about whether his knives should be allowed to doubly function as food knives. Allison stands up so she can straighten Luther’s party hat where the earlier fight knocked it off kilter. Grace moves to stand behind Five, placing a kind hand on his shoulder.

He looks up at her, looking contemplative. “Aren’t wishes for children?” He asks her, even though he participated along with the rest of them.

“Wishes are for everyone.” Grace informs him with a smile, leaning down and and pressing a kiss against his forehead. He made a face at her, so reminiscent of when he was younger, but didn’t move to scrub the kiss away like he might have done back in those days.

“Happy Birthday, Five.”

“Thanks, Mom.”

#inktober#tua inktober#the umbrella academy inktober#tua#the umbrella academy#five hargreeves#number five#luther hargreeves#diego hargreeves#klaus hargreeves#allison hargreeves#ben hargreeves#vanya hargreeves#grace hargreeves#these guys are very chaotic tbh#grace's full time job was keeping them from killing each other as kids#it. hasn't changed much#five has issues#but we address some of those issues like men#everybody wears a birthday hat#inktober day one#birthday#prompt: birthday

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

woodland creatures tour - day 7 (greensboro)

normally i feel very weird about sleeping over people’s houses, just in general??? you know what i mean? sometimes you just can’t get comfortable because you’re not in your own bed, not because of where you are or who you’re with. on tour i’m so fucking exhausted and so comfortable with living like i’m a backpacker that it’s all just normal to me. like a brat i located the couch and crawled up onto it while everyone else took an air mattress. i would have slept on an air mattress but we couldn’t fit one lmao.

i automatically woke up at like 8:30 and couldn’t fall back asleep, so i got up and started getting ready. tour has also made me skilled at being able to freshen up and do my makeup in the crevice of any house, hotel, car, you name it. i try not to make noise but inevitably everyone heard me and slowly woke up one by one. the door was unlocked so i started to pack whatever i could into the van. god, it was so beautiful out. though we were in the south, and the temperature was still pretty high day-to-day, at this moment it just felt like the most beautiful fall weather. we managed to get out of the house at 9:30 am, which we were aiming for. james’ roommate, who was leaving for work, kindly wished us well as we packed up the van to head out. we unfortunately missed james so i shot him a text.

the day before, taylor and i coordinated a group outing to the greensboro science center, which was a museum, zoo and aquarium all in one. for the price of $12 per person, since we were a group!!! incredible! before heading to greensboro, which would be our shortest drive all of tour (an hour and a half!), we hit starbucks and panera again. when we pulled up to the panera it was in a shopping plaza with people lined up waiting for like... verizon to open???? so bizarre.

i desperately needed to hunker down and get some work done before we hit the road, for the most part my phone was providing reliable wifi but i had a time sensitive task that needed to be completed. once that was done we hit the road. we arrived to the science center and once pulses. showed up, we headed in. the science center was so sick. we started our trek around the building at like 1, and penguin feeding was at 3:30. but with so much exploring to do, we knew we’d be able to kill two hours and a half easily.

we started with the zoo portion a

nd saw a lot of cool animals. they had a lot of atypical mammals you don’t always see at zoos. what they DID have was R E D P A N D A S, and theY WERE AWAKE. back at home we have the cape may zoo which is soooooo sick, i love going there, but their red pandas are always sleeping. i literally cried because the red pandas at this exhibit were so much closer, and they were romping around their lil home. the one red panda hopped off its perch and CAME TO THE WINDOW TO SAY HELLO IT JUMPED UP RIGHT IN FRONT OF US. i definitely made a fool of myself getting loudly emotional but i didn’t care in the slightest. my entire life was made. we also saw an owl at the barn where the petting zoo was!!!

we were all laughing so fucking hard cracking jokes at every exhibit. it felt like an adult school field trip hahaha. i was having so much fun. it was nice to enjoy something together and not be stuck in a van in a rush to get somewhere. the outdoor area tuckered us out pretty badly from being in the heat, so it was nice to get back inside to go check out the aquarium in the air-conditioned building. the aquarium was pretty sick, there was a tank that was home to the biggest octopus i have ever seen in person. i was most interested in the otters and penguins, to be honest. we also hit the touch tank which was sick, except i had to soak my entire fucking arm just to maybe get a crumb of attention from a sting ray. they were swimming everywhere but where i planted myself.

after going through the aquarium, we still had some time to kill before the penguin feeding at 3:30 pm. we hit the gift shop, where they had red panda and barn owl plushes. what a coincidence, both our tour mascots!! i’m a sucker for stuffed animals so of course i bought one. taylor bought an owl for pulses. so now we both had FRIENDS to represent our bands. we went downstairs to go check out the snakes and lizards. not as exciting for me, but still sick. we were going to hit the museum part finally, but it was 3:20 so we figured might as well head over to the penguins. it was worth the wait. there was a penguin named gojira haha

it turned out that there was enough time for us to get food together before the show. jaime found a restaurant named pastabilities, it was a sit-down but you could make your own pasta dish chipotle-style???? so i got chickpea pasta with chicken, sundried tomatoes, spinach and mushrooms. sooooooooooooooooooo good. i wasn’t going to get pasta because i was going to try to be a healthy guy but ugh what the fuck ever. i love pasta. i’m not going to rob myself of pasta opportunities!!!! we had another really wonderful meal together as a tour package. i guess because we were the biggest group and you could hear us talking loudly about tour the staff figured out we were musicians. the manager came over and started asking who played what haha.

after a delicious early dinner, we drove to our hotel for check-in so that we could drop our personal bags. pulses. followed us because they were just driving home after the show later, and waited in the parking lot until they could head to the venue. i forget the name of the hotel we stayed at but the people in there were super suspect, and projecting those vibes FOR sure. taylor said she thinks she saw a guy walking around with a burner phone as a car was slowly driving in circles around the parking lot. i’m like great, last thing we need is another scary motel. our stuff ended up being fine though, it was one of the better spots we stayed at.

pulses. awaited us at the venue and we arrived a little after load-in started. it was super quiet when we showed up, we set up quickly and waited around. the house we played, ice house, was huge. so much more massive than houses in new brunswick where students in jersey host shows, mostly. there was so much room to move around and sit, it was nice. at first it seemed like not many people were inside, but then you go outside and there’s DOZENS of kids hanging out drinking. eventually more and more people came inside to watch the bands too. glow and terms x conditions were great!

for all of us, it had been a weird afternoon, but we did our best to be positive and just rip our set(s) as best as we could. and the change in attitude paid off! both our bands received awesome crowd response from the people who attended. it was awesome to see people jamming out and genuinely having a good time. also uh a fight broke out during our set??? insane. there was a kid trying to take down everyone, like just to the ground lmao, and when he tried to do it to david he put in a chokehold. and david grabbed his arm and was just like, STOP. i made everyone stop playing until we sorted out that everything was all right. i had to play without my in-ears which sucked, in the past i have always struggled and tired myself out trying to sing loud enough over the monitors. so i just tried to listen carefully, sing carefully and trust myself. and joe said i hit some like bananas note during synapse that i haven’t been able to do since?? i remember going for it and it was fine, idk maybe it was actually BAD, but i will never know now haha.

we didn’t sell merch, nor make a lot of money, but i think what counts as a successful show is when people receive you super well. leaving a positive first impression on somebody as a band is so important to me because that person could potentially go on to listen to us for a long time. i will say though, it’s important to try to help touring bands make money if you can, like legit anything. i know we’re small guys and we’re not worth much, but we travel so far from home. and this is the ONE time of year that we actually do need money to operate. i’ve run into people who don’t believe in this, or don’t understand. i guess it won’t be possible to make those people understand until it happens to them. it’s why we can only tour on vacation time and even then we deplete our funds.

we sweat our fucking asses off playing the house because it had no AC, so nothing could feel more refreshing than loading out during a rainstorm. i wasn’t even mad that it was raining. it felt so amazing. normally i bug out during crazy storms, but the thunderstorm was lighting up the sky in an incredible display. it continued as we said our goodbyes to pulses. before they headed back to virginia late, and we made our way to sheetz for post-gig eats. i wasn’t going to pig out but i was feeling the munchies. sheetz doesn’t really have anything wawa doesn’t have except for the tacos, so i got some hard shell tacos that were absolutely banging. also wonderful, they had my favorite flavor of bon & viv (black cherry rosemary) so i grabbed that too. eating tacos and drinking late was NOT a smart move the night before we played our last show on tour, but boy did it feel like a nice TREAT after playing a fantastic show.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

As promised, here the continuing rec list of fics where Louis is called pet names. Part one can be found here, and when it’s out, part three will also be linked here. Happy reading!

1) Tie You Up and Make Me Scream | Explicit | 2166 words

AU where Harry teases Louis and it becomes a game until they cant handle it anymore and escape to have tent sex while the rest of the boys are in the other tents.

2) Feel The Need | Explicit | 4898 words

Louis and Harry attend Liam's Halloween party. Risky Business ensues.

3) Just Stop Your Crying (It’s A Sign Of The Times) | Explicit | 5864 words

My own imagining of the inspiration for Sign of the Times. Featuring boys in love, even after all this time.

4) We’ll Stumble Through Heaven | Explicit | 6504 words

Louis likes to be a good boy for his alpha.

5) Raised on Rhythm and Blues | Explicit | 8034 words

“That look on your face makes me think you’re not cooking me spaghetti fast enough,” Louis announces as he walks back into the kitchen. Harry knows exactly where Zoe gets her habits from.

“Cooking for my two beautiful and insanely intelligent children, not for the weird bloke that sleeps in my bed and eats all my food,” Harry answers, tilting his head and wondering if he should add more sauce.

6) Forever, Uninterrupted | Explicit | 8578 words

Harry finds a mysterious picture in Louis' bag one night and drives himself crazy over it. It's definitely not what he thinks.

7) Spice Up Your Life | Explicit | 9501 words

After a conversation with his Uni friends, Harry worries that his relationship with Louis has lost it's spark.

8) Infinitely All For Me | Explicit | 10630 words

The Alpha Louis' been betrothed to since he was 14 has finally come of age and Louis' been delivered to his home.

9) Keep Holding Me This Way | Explicit | 13747 words

An English grad student, a frat jock, and an unimpressed rich boy walk into a bar. No one walks out.

10) Let’s Take the World By Storm | Explicit | 14656 words

Harry lifts his head off Louis' chest to look at Louis' face. "What's that supposed to mean?"

“I don’t know, but our sex life feels a bit boring, ‘sall,” Louis says, completely avoiding eye contact.

“Boring.” Harry says flatly. He doesn’t say anything more, and Louis looks up to see that Harry seems to be mulling it over.

“Yeah, boring," Louis says, and keeps talking before Harry can pipe up. “I mean, think about it. We’ve been dating since X Factor, and now things are starting to drag a bit. We don’t even have the time for handjobs anymore, much less actual sex.”

11) The Seed Inside You, Baby, Do You Feel It Growin’ | Explicit | 14793 words

Louis really wants Harry to get him pregnant.

12) Oops, Baby, I Love You (In That Order) | Explicit | 25344 words

The minute Louis Tomlinson decides he don’t need no man to start a family, Harry Styles literally falls into his arms.

13) Another Day Gettin’ Into Trouble | Explicit | 25619 words

Harry’s drunk when the idea occurs to him. He’s also a pop star, so sometimes his drunk ideas turn into actual things instead of just ideas. The clone-a-willy kit is one of them.

In Harry’s defense, when he first thinks about it his intention is just to buy the kit and give it to Louis to make his own dildo with, because that’s what he wants anyway, right? To have a penis filling him up?

Then he realizes that it would be weird if Louis made a copy of his own dick to fuck himself with. It’d be super weird. Louis fucking himself? That’s a weird idea. Harry’s pretty sure Louis wouldn’t like that.

Clearly the only solution here is to use his own dick for the mold.

14) Force of Nature | Mature | 25672 words

Louis is a shy, young musician who doesn't want to go to Harvard.

Harry is a confident, second year athlete who likes to have a good time.

When their paths cross while their families are vacationing at the same lake resort, what begins as a summer of fun becomes a defining journey that might just change everything.

15) Up To No Good | Explicit | 26525 words | Sequel 1 | Sequel 2

Harry doesn’t think of himself as a womanizer, not at all. Sure, he enjoys sex, enjoys how women feel underneath him, and by some people’s standards he has sex with quite a lot of people, but that’s no reason to tell him that he can’t have a female PA anymore.

It’s especially no excuse for giving him a male PA who’s possibly the most gorgeous boy in the world who won’t even let Harry look at him for too long.

Sometimes Harry hates his life.

16) Always Come Back To You | Explicit | 28862 words

“I’ll do it,” Harry offers brightly. No one even blinks. “I’ll do it?”

Louis sighs irritably. “Shut up,” he orders, tossing a pillow in the general direction of Harry’s face. This is a terrible time for jokes, especially Harry’s lame, old people ones.

Not that it was an old people joke. Just that most of the time Harry’s jokes consist of knock-knocks or terrible puns. The type of jokes old people like, Louis’ pretty sure. His nan always finds them hilarious when Harry tells her one.

Harry bats the pillow out of the air without even blinking. “Be reasonable, Lou,” he says in his most reasonable voice.

Louis is perfectly reasonable, thank you very much, and he’s also frustrated and upset and tired and he really wants to punch something. Maybe he should have held on to that pillow a little longer.

“You’re not gonna fucking do it,” he snaps. “That’s the last thing I need.”

17) Blind From This Sweet, Sweet Craving | Explicit | 31170 words

"So, I guess we'll go?" Louis asks later, when Harry has calmed down and eaten his weight in Chinese food. He plays with this chopsticks, spearing another piece of chicken and pops it in his mouth. "I mean, I wouldn't mind. We could make it an adventure."

Harry observes him, watches him seated across from him on their old living room carpet, with a container of food on his lap. He's fidgeting, avoiding meeting Harry's gaze–he probably knows that Harry's mad at him for ruining the one chance they had to get out of this situation. And he's not wrong, Harry is definitely very mad. Harry wants to strangle him and castrate him and smack him upside the head.

But he's also Harry's best friend, and despite everything, despite all the fuck-ups and the plot twists and everything just not playing out the way it should, he'd still rather be stuck in this situation with Louis than any of the other boys. He's got Harry's back, and in a weird, abstract way, he knows they'll be able to get out of this situation, together.

Harry sighs. "We're going," he says resignedly, his shoulders slumping.

Oh well. There are definitely worse ways to spend the weekend than pretending to be engaged to his best friend.

18) Cupid’s Chokehold | Explicit | 35326 words

Louis is a Cupid who tries to match up Niall and Harry. It doesn't work out as planned.

19) Mark My Word (We Gon’ Be Alright) | Explicit | 35524 words

"He’s always known that there would come a time when Harry would bond with some beautiful, quiet omega, and they would have lots of curly-haired pups and live happily ever after.

Knowing it and living it are two very different things, though. Watching the object of your affection desperately search for a mate and completely disregard you as an option is all sorts of painful, but it is what it is, and Louis is just going to have to learn to live with that."

20) Who Would’ve Thought | Explicit | 44275 words | Companion Fic

The idea doesn’t come to Louis until they’ve been at the bungalow for a couple of days. Harry has no idea that he’s going to pop a knot. He’s been living his life with the expectation that he’s going to be a beta, and Louis isn’t going to tell him otherwise.

Louis is an omega, though, and most omegas want to be filled up with a knot, fucked the way their bodies are made to be fucked, and Louis is no different. In ten years he wants to have an alpha waiting for him at home who will hold him down and fuck him exactly the way Louis wants to be fucked without worrying that they’re going to expect him to stay at home, open a joint bank account, raise a litter of babies, cook and clean and, most importantly, be submissive. For that to happen Louis needs an entirely different kind of alpha.

And so the plan is born.

21) Tangled Up In You | Explicit | 45152 words

Harry blinks once. And blinks again. And says, his voice dangerous: “Niall, did you get me a mail-order bride?”

Because what the actual fuck. It kind of looks like Niall’s just purchased a person. For Harry.

Niall blinks back at him for a few moments, before throwing his head back and howling with laughter. Harry throws a pillow at him. Hard. “No, what the fuck, Harry.”

“A prostitute then?” Harry also doesn't want a prostitute.

“Of course not!”

“A stripper?”

“No!”

Damn, he’s running out of ideas. He settles for launching another pillow at Niall’s head. Niall bats it away easily, still laughing. “Stop!”

“What did you get me, then?!” Niall must hear the tinge of hysteria in his voice, because he’s pulling himself together, trying to stop himself from laughing.

There’s still a big grin on his face, though, when he says, “I got you a professional cuddler.”

A professional…what. “What?”

22) Nobody Does It Like You | Not Rated | 58820 words

Louis isn't looking for a home, but he finds one in Harry.

23) Tug-Of-War | Explicit | 63000 words

Louis' husband dies suddenly and he is left with nothing. Well, not really nothing. He has Harry. And a St. Bernard puppy named Link, whom his late husband left behind for him. Louis takes care of Link and Harry takes care of Louis. Everything is okay until suddenly, it isn't.

24) Why Can’t It Be Like That | Explicit | 63567 words

A fashion AU with a royal twist, where Louis doesn't need a stylist, Harry's thrilled to have a real life Barbie doll, and they're both very wrong about each other.

25) Perfect Storm | Explicit | 80230 words

What do you do when your best friend asks you and your (now) ex to be the best men at his destination wedding? You can either tell him the truth, tell him you’re not together anymore, and deal with the consequences, or you can pretend you’re still together and roll with it, just pray you don’t spiral. Fake it ‘til you make it. You know, for the sake of the wedding.

Harry and Louis choose the latter.

Check out our other fic rec lists by category here and by title here.

264 notes

·

View notes

Text

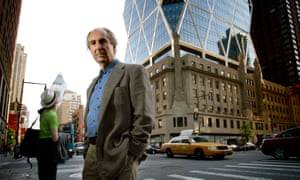

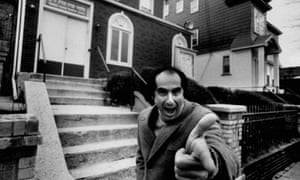

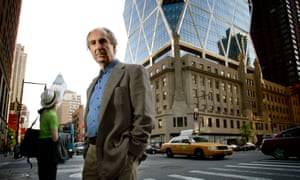

'Savagely funny and bitingly honest' – 14 writers on their favourite Philip Roth novels

New Post has been published on https://funnythingshere.xyz/savagely-funny-and-bitingly-honest-14-writers-on-their-favourite-philip-roth-novels/

'Savagely funny and bitingly honest' – 14 writers on their favourite Philip Roth novels

Emma Brockes on Goodbye, Columbus (1959)

I fell in love with Neil Klugman, forerunner to Portnoy and hero of Goodbye, Columbus, Philip Roth’s first novel, in my early 20s – 40 years after the novel was written. Descriptions of Roth’s writing often err towards violence; he is savagely funny, bitingly honest, filled with rage and thwarted desire. But although his first novel rehearses all the themes he would spend 60 years mining – sexual vanity, lower-middle-class consciousness (“for an instant Brenda reminded me of the pug-nosed little bastards from Montclair”), the crushing weight of family and, of course, American Jewish identity – what I loved about his first novel was its tenderness.

Goodbye, Columbus is steeped in the nostalgia only available to a 26-year-old man writing of himself in his earlier 20s, a greater psychological leap perhaps than between decades as they pass in later life. Neil is smart, inadequate, needy, competitive. He longs for Brenda and fears her rejection, tempering his desire with pre-emptive attack. All the things one recognises and does.

My mother told me that the first time she read Portnoy’s Complaint she wept and, at the time, I couldn’t understand why. It’s not a sad novel. But, of course, as I got older I understood. One cries not because it is sad but because it is true, and no matter how funny he is, reading Roth always leaves one a little devastated.

I picked up Goodbye, Columbus this morning and went back to Aunt Gladys, one of the most put-upon women in fiction, who didn’t serve pepper in her household because she had heard it was not absorbed by the body, and – the perfect Rothian line, wry, affectionate, with a nod to the infinite – “it was disturbing to Aunt Gladys to think that anything she served might pass through a gullet, stomach and bowel just for the pleasure of the trip”. How we’ll miss him.

Emma Brockes is a novelist and Guardian columnist

James Schamus on Goodbye, Columbus (1959)

Philip Roth was more than capable of the kind of formal patterning and closure that preoccupied the work of Henry James, with whom he now stands shoulder-to-shoulder in the American literary firmament. So yes, one can always choose a singular favourite – mine is the early story Goodbye, Columbus, though I know the capacious greatness of American Pastoral probably warrants favourite status. But celebrating a single Roth piece poses its own challenges, in that his life’s work was a kind of never-ending battle against the idea that the great work of fiction was anything but, well, work – work as action, creation; work not as noun but as verb; work as glorious as the glove-making so lovingly described in Pastoral, and as ludicrous as the fevered toil of imagination that subtends the masturbatory repetitions of Portnoy’s Complaint. Factual human beings are fiction workers – it’s the only way they can make actual sense of themselves and the people around them, by, as Roth put it in Pastoral, always “getting them wrong” – and Roth was to be among the most dedicated of all wrong-getters, his life’s work thus paradoxically a fight against the formal closure that gave shape to the many masterpieces he wrote. Hence the spillage of self, of characters real and imagined, of characters really imagining and of selves fictionally enacting, from work to work to work. So, here, Philip Roth, is to a job well done.

James Schamus is a film-maker who directed an adaptation of Indignation in 2016

I read it when I was about 18 – an off-piste literary choice in my sobersided studenty world. I had been earnestly dealing with the Cambridge English Faculty reading list and picked up Portnoy having frowned my way through George Eliot’s Romola. The bravura monologue of Alex Portnoy wasn’t just the most outrageously, continuously funny thing I had ever read; it was the nearest thing a novel has come to making me feel very drunk.

And this world-famously Jewish book spoke intensely to my timid home counties Wasp inexperience because, with magnificent candour, it crashed into the one and only subject – which Casanova, talking about sex, called the “subject of subjects” – jerking off. The description of everyone in the audience, young and old, wanking at a burlesque show, including an old man masturbating into his hat (“Ven der putz shteht! Ven der putz shteht! Into the hat that he wears on his head!”) was just mind-boggling. A vision of hell that was also insanely funny. Then there is his agonised epiphany at understanding the word longing in his thwarted desire for a blonde “shikse”. (Was I, a Wasp reader, entitled to admit I shared that stricken swoon of yearning? Only it was a Jewish girl I was in love with.) Portnoy’s Complaint had me in a cross between a chokehold and a tender embrace: this is what a great book does.

Peter Bradshaw is the Guardian’s film critic

William Boyd on Zuckerman Unbound (1981)

Looking back at Philip Roth’s long bibliography, I realise I’m a true fan of early- and middle-Roth. I read everything that appeared from Goodbye, Columbus (I was led to Roth by the excellent film) but then kind of fell by the wayside in the mid 1980s with The Counterlife. As with Anthony Burgess and John Updike, Roth’s astonishing prolixity exhausted even his most loyal readers.

But I always loved the Zuckerman novels, in which “Nathan Zuckerman” leads a parallel existence to that of his creator. Zuckerman Unbound (1981) is the second in the sequence, following The Ghost Writer, and provides a terrifying analysis of what it must have been like for Roth to deal with the overwhelming fame and hysterical contumely that Portnoy’s Complaint provoked, as well as looking at the famous Quiz Show scandals of the 1950s. Zuckerman’s “obscene” novel is called Carnovsky, but the disguise is flimsy. Zuckerman is Roth by any other name, despite the author’s regular denials and prevarications.

Maybe, in the end, the Zuckerman novels are novels for writers, or for readers who dream of being writers. They are very funny and very true and they join a rich genre of writers’ alter ego novels. Anthony Burgess’s Enderby, Updike’s Bech, Fernando Pessoa’s Bernardo Soares, Ernest Hemingway’s Nick Adams, Edward St Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose and so on – the list is surprisingly long. One of the secret joys of writing fictionally is writing about yourself through the lens of fiction. Not every writer does it, but I bet you every writer yearns to. And Roth did it, possibly more thoroughly than anyone else – hence the enduring allure of the Zuckerman novels. Is this what Roth really felt and did – or is it a fiction? Zuckerman remains endlessly tantalising.

William Boyd is a novelist and screenwriter

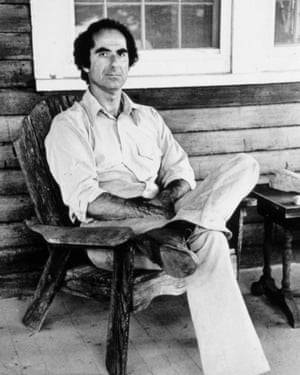

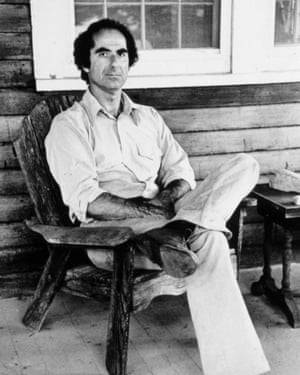

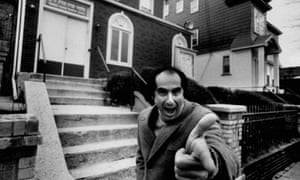

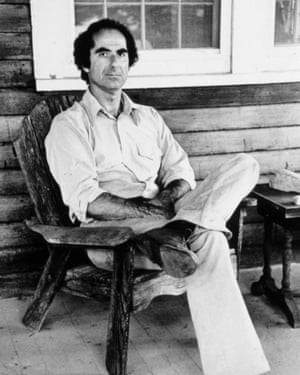

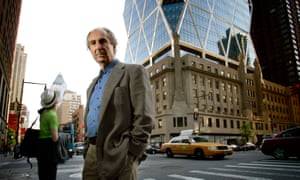

Roth outside the Hebrew school he probably attended as a boy. Photograph: Bob Peterson/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

David Baddiel on Sabbath’s Theater (1995)

Philip Roth is not my favourite writer; that would be John Updike. However, sometimes, on the back of Updike’s – and many other literary giants – books, one reads the word “funny”. In fact, often the words “hilarious”, “rip-roaring”, “hysterical”. This is never true. The only writer in the entire canon of very, very high literature – I’m talking should’ve-got-the-Nobel-prize high – who is properly funny, laugh-out-loud funny, Peep Show funny, is Philip Roth.

As such my choice should perhaps be Portnoy’s Complaint, his most stand-uppy comic rant, which is gut-bustingly funny, even if you might never eat liver again. However – and not just because someone else will already have chosen that – I’m going for Sabbath’s Theater, his crazed outpouring on behalf of addled puppeteer Mickey Sabbath, an old man in mainly sexual mourning for his mistress Drenka, which could anyway be titled Portnoy’s Still Complaining But Now With Added Mortality. It has the same turbocharged furious-with-life comic energy as Portnoy, but a three-decades-older Roth has no choice now but to mix in, with his usual obsessions of sex and Jewishness, death: and as such it becomes – even as we watch, appalled, as Mickey masturbates on Drenka’s grave – his raging-against-the-dying-of-the-light masterpiece.

David Baddiel is a writer and comedian

Hadley Freeman on American Pastoral (1997)

American Pastoral bagged the Pulitzer – at last – for Philip Roth, but it is not, I suspect, his best-loved book with readers. Aside from his usual alter ego Nathan Zuckerman, the characters themselves aren’t as memorable as in, say, Portnoy’s Complaint, or even Sabbath’s Theater, which Roth wrote two years earlier. And yet, of all his books, American Pastoral probably lays the strongest claim that Roth was the great novelist of modern America.