#early summer

Photo

June

#own photo#2 hours ago#I like how#two thirds across#that sort of light/dark divide appears#especially in the water#weirdly defined#woods#forest#nature#field#june 2023#late spring#early summer#walks#adventures#gloucestershire#nature photography#original photography#lensblr#light#shadows#outdoors#june

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Early summer at Sanzen-in, Kyoto, by Fujishima Takeji (1951).

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

SETSUKO HARA as Noriko in Yasujirō Ozu’s NORIKO TRILOGY:

LATE SPRING / 晩春 (1949)

EARLY SUMMER / 麥秋 (1951)

TOKYO STORY / 東京物語 (1953)

#setsuko hara#yasujiro ozu#late spring#early summer#tokyo story#worldcinemaedit#classicfilmcentral#filmauteur#cinemaspast#filmgifs#ladiesofcinema#japanese cinema#yasujirō ozu#banshun#late spring 1949#early summer 1951#bakushu#tokyo monogatari#晩春#麥秋#東京物語#setsukoharaedit#ozuedit#ozugifs#shgif#ellisgifs#myfilmgallery#from the drafts

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

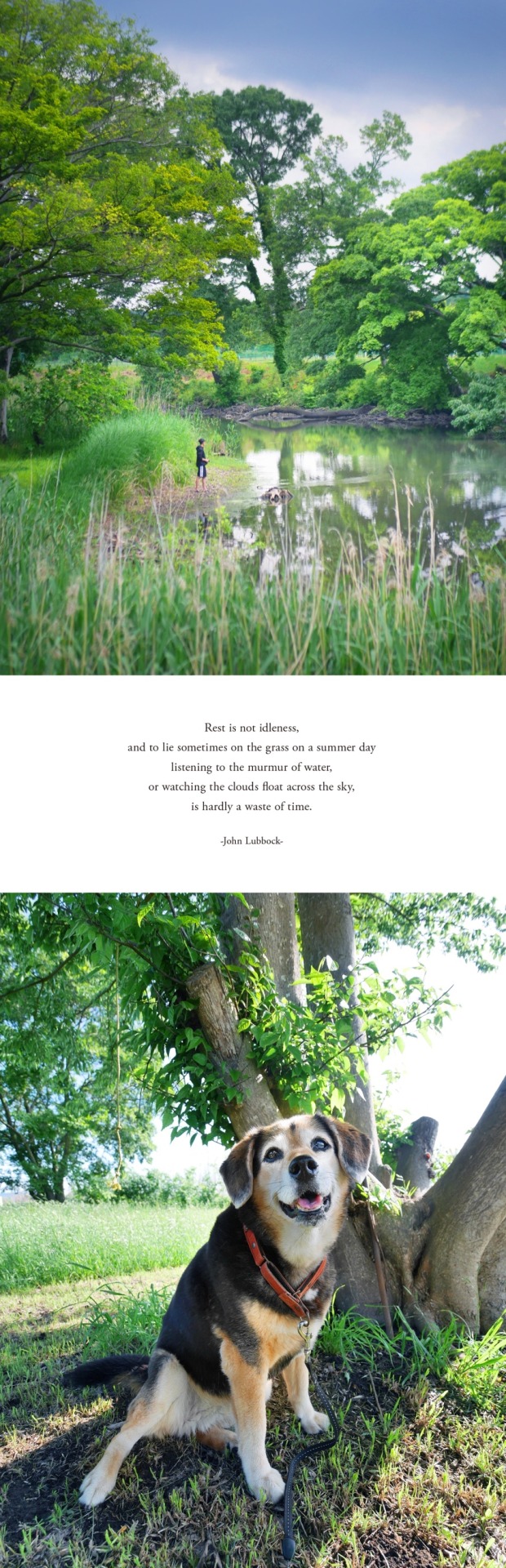

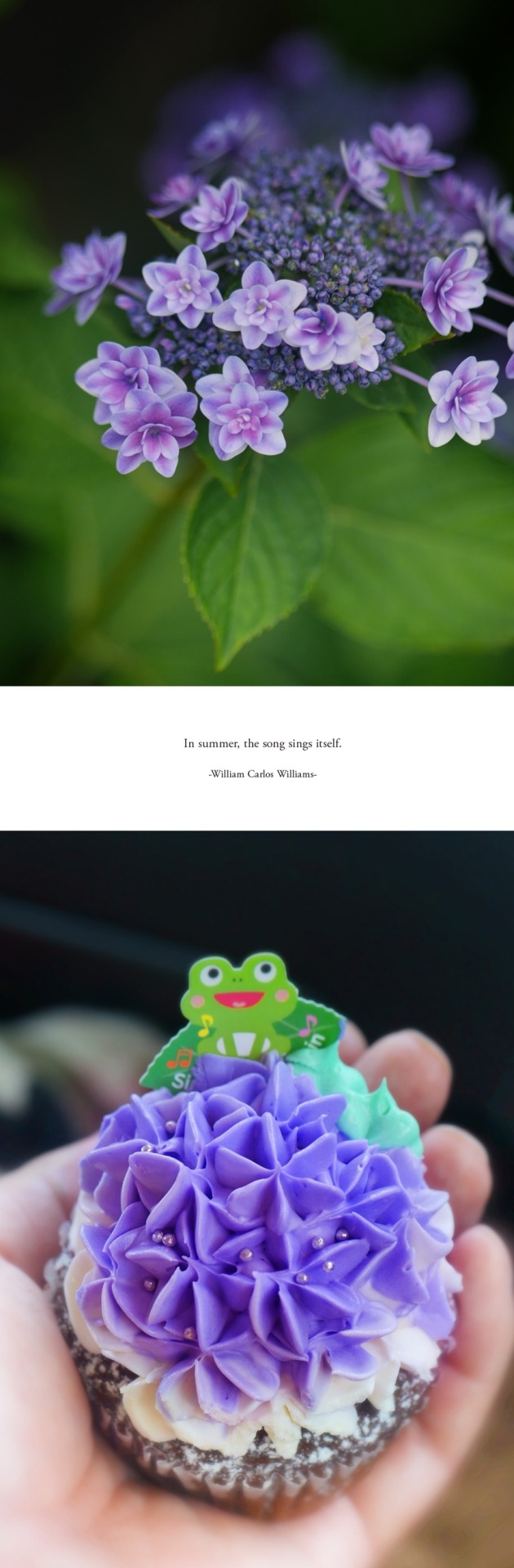

The season moves at a quick pace.

Spring flowers are turning into early summer flowers, the leaves become deeper green, and the sunlight is getting stronger.

Now, hydrangea is blooming beautifully everywhere. And there is a lovely hydrangea in my palm as well💜(This is a tiny cupcake😉🎶🧁)

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=lKbb_GPlyio

448 notes

·

View notes

Text

#nature#landscape#trees#lake#photographers on tumblr#artists on tumblr#lensblr#birches#birch trees#water#vertical nature#spring#early summer#original photography#may 2023

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

'23.6.3 飛火野、春日大社参道付近にて

雨台風過ぎた前回投稿の続きです。曇り日であっても雨の翌朝は写真に撮ると、水の反射が多いからか意外とコントラストが上がることを再認識しました・・。

#奈良#nara#日本#japan#奈良公園#nara park#飛火野#tobihino#春日大社#kasuga tasiha shrine#鹿#deer#子鹿#fawn#雨上がり#after the rain#初夏#early summer#photographers on tumblr#natgeoyourshot

292 notes

·

View notes

Photo

レモン×ミントソーダの妖精

Fairy of lemon x mint soda

#レモン#ミント#ソーダ#妖精#fairy art#fairy#lemon#mint#soda#初夏#early summer#ワンピースコーデ#ワンピース#one piece#ロリータファッション#ガーリーファッション#ファッションイラスト#lolita fashion#kawaii fashion#girly fashion#fashion#イラスト#Illustration

262 notes

·

View notes

Photo

DAILYWORLDCINEMA CELEBRATES 5K FOLLOWERS: Each Member’s Favourite Character in World Cinema - [Natty & @pixienatthecat]

→ Setsuko Hara as Noriko in Late Spring (1949) / Early Summer (1951) and Tokyo Story (1953) Directed By: Yasujiro Ozu

#late spring#tokyo story#early summer#filmgifs#classicfilmblr#moviegifs#dailyflicks#uservintage#dwc5k#usersunny#usercande#userkd#userraffa#usermulder#userkraina#1940s#1950s#japan#filmedit#worldcinemaedit#ours#by natty

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early Summer in Tuscany, Italy

By Jeff Stanford, 2023

Buy prints at:

https://jeff-stanford.pixels.com/

#© Jeff Stanford#midjourney#midjourneyart#ai#discord#digitalart#aiart#Artists on tumblr#Early Summer#Tuscany#Italy#cottage#poppies#field#May

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Early Summer is about the difference between the married and the unmarried, how the married try to persuade or (worse) coerce the unmarried into getting married, and how maybe that isn’t always such a good idea. This theme is explicitly called out more than once in the film.

Early Summer further implies that there may be a good reason why some unmarried people, including Noriko (but not just Noriko), don't want to marry: they may be “that type of person,” as the young lesbian Fumi described herself in Takako Shimura's manga Aoi hana. This subtext rises briefly to the level of text at least once before being ambiguously dismissed.

Both Ozu and Hara remained unmarried until their deaths, and to my knowledge neither were ever credibly reported as having a romantic relationship with anyone. Per Donald Richie’s commentary on the Criterion release (referenced in the next post), Ozu was reported to become angry at any talk of his marrying. Meanwhile Hara, though termed “the eternal virgin” by a film producer for her film image, in real life had close friendships with many women, including a hair and makeup artist whose friendship with Hara began early on and continued after Hara retired into obscurity at the height of her career.

In modern terms we could therefore hypothesize Early Summer as a queer film subtly but firmly protesting compulsory heterosexuality, made by a (possibly) queer director and starring a (possibly) queer actor.

…

Early Summer opens with three establishing shots: first a shot of a dog walking freely on the beach with the ocean in the background, then a shot of a single bird in a cage outside, and then a final shot of birds in cages inside a house. This is the house in the oceanside town of Kamakura in which Noriko (Setsuko Hara’s character) lives, along with her brother Kōichi (Chishū Ryū), his wife Fumiko (Kuniko Miyake), Noriko and Koichi’s father (Ichiro Sugai) and mother (Chieko Higashiyama), and Kōichi and Fumiko’s two young boys.

If we wish, we can interpret the first and third shots as showing a strong contrast between freedom in nature on the one hand, and the restrictions imposed by society and the Japanese family system on the other. In this interpretation the second shot represents Noriko, who has a degree of independence that her mother and Fumiko do not have, but is still constrained by the bonds of family and society.

In the following scenes Kōichi takes an early train to his job as a physician, while Noriko goes to the Kita-Kamakura station to catch a later one. There she meets Kenkichi, another physician who works with Kōichi and who (along with his mother) is the family’s next-door neighbor. Kenkichi tells her that he’s been reading a book, implied to have been recommended by Noriko. The Criterion release describes it only as “this book,” but the BFI release names it as Les Thibaults.

Les Thibaults (published in Japanese as Chibō-ka no hitobito, and apparently relatively popular in Japan at the time) is a multi-volume French novel that begins as one of its protagonists is discovered writing passionate messages to a fellow schoolboy — something Ozu himself was apparently falsely accused of — and is then separated from his friend. Later volumes describe their diverging paths in life. Why might have Noriko recommended this particular novel to Kenkichi? Hold that thought.

We then see Noriko at work, as a secretary and executive assistant to the head of a small firm (Shūji Sano). As she talks with her boss regarding café recommendations, her best friend Aya (Chikage Awashima) arrives, there to collect payment for the boss’s spending at the restaurant her mother owns. Noriko’s boss wonders when they’ll both get married, and refers to them as “old maids.”

(Before becoming a movie actress, Chikage Awashima was a musumeyaku top star in the Takarazuka Revue and occasionally played “pants roles,” i.e., as a female character dressing as a man for plot reasons. Osamu Tezuka was a fan of hers, and she supposedly inspired the main character Sapphire, “born ... with a blue heart of a boy and a pink heart of a girl,” in his manga Princess Knight. Why might this be relevant to Early Summer? Again, hold that thought.)

After work, Noriko meets Kōichi and Fumiko for dinner. While they eat, Kōichi complains about post-war women (“[They’ve] become so forward.”) and Noriko corrects him: “We've just taken our natural place.” Kōichi then claims that’s why Noriko can’t get married, and she rebukes him: “It’s not that I can’t. I could in a minute if I wanted to.” (Note: a bit of foreshadowing here.)

Next occur the two key events that set the main plot in motion. First, Noriko’s great-uncle (Seiji Miyaguchi) arrives for a visit. He wonders why she isn't married yet. “Some women don't want to get married,” he tells her. “Are you one of them?” Noriko laughs and leaves the room, but the seed has been planted in the minds of her family.

Noriko’s boss also thinks it's time for her to get married, and he has just the man for her: “He’s never been married. Not sure if he's still a virgin.” Her boss has photographs to show her, and won’t leave her leave without taking them.

Meanwhile Noriko and Aya mercilessly tease one of their married friends, and after attending another friend’s wedding have dinner with that friend and another married friend, with a side dish of sexual innuendo. One of the married friends brags about how she spent a rained-out honeymoon playing with a “spinning top”: “My husband is very good at it.” Her friend cautions her: “You shouldn't flaunt it in front of the single girls.”

However, Aya is not impressed with the implied amazingness of heterosexual intercourse: “Silly! We don’t play with tops, do we?” Noriko enthusiastically agrees with her: “That’s for children, isn’t it?” The debate between the married and the unmarried continues, after which Noriko goes home, where Kōichi and Fumiko are scheming regarding the marital candidate proposed by Noriko’s boss.

Kenkichi’s mother then visits Noriko’s mother, and tells her that a man from a detective agency has been asking about Noriko: “I realized it was about her marriage.” We also learn that Kenkichi’s wife died two years ago (leaving him with a young daughter), and that he's not interested in remarrying: “All he does since his wife died is read books” (like Les Thibaults). Finally, we learn that Kenkichi’s best friend, Noriko’s brother Shoji, went missing in the war.

We now come to the climax of the first half of the movie. As Noriko’s nephews and their friends play with their model train set downstairs (one nephew asking if their father will buy them more train track), Aya visits Noriko and they talk in her room upstairs. Their married friends have made various excuses for why they couldn’t also visit; Noriko recalls how close they were at school and laments their drifting apart.

Throughout the first half of Early Summer Noriko and Aya are shown as mirroring each other’s gestures and speech. That mirroring continues in this scene (for example, they sit down next to each other at the exact same time and in the exact same manner), and then a very interesting thing happens. Ozu’s typical modus operandi is to continue a shot until someone stops speaking or moving, or even until they leave the room. But here he cuts immediately from Noriko and Aya simultaneously raising their glasses to drink, to Noriko’s father and mother simultaneously bringing food to their lips, as they relax sitting on a street curb in town.

If I were to speculate about what this juxtaposition might mean, if anything, I’d speculate as follows: that Ozu intended to show that, whatever Aya and Noriko might be to each other, they are as close, secure, and happy in their relationship as Noriko’s mother and father are in theirs — as much a couple as any other in the film, but not formally recognized as such.

Noriko’s father tells his wife, “This may be the happiest time for our family,” although he’s sad at the thought of Noriko leaving. They continue their conversation, and then are interrupted by the site of a balloon rising into the sky. “Some child must be crying,” Noriko’s father remarks. “Remember how Kōichi cried when he lost his balloon?”

…

The good times continue as Noriko brings home a cake to eat with her sister-in-law Fumiko, and their neighbor Kenkichi drops in unexpectedly and is invited to share it with them. The scene re-introduces Kenkichi and brings up the subject of his remarrying — something he doesn’t want, but his mother (played by Haruko Sugimura) does.

…

In the meantime Noriko’s brother Kōichi has been pursuing the idea of a marriage between Noriko and an unseen bachelor first suggested by Noriko’s boss, including asking his friends and associates for more information on the proposed groom. The results are “very promising”: “He’s in the social register, and seems to be a fine businessman.” “How nice,” replies his mother, but, “how old is he?”

…

Then Noriko’s boss asks a few questions that we’ve been asking ourselves. While Noriko is away from work, Aya stops by, and the boss questions Aya on whether Noriko will go through with the match or not: “I don't understand her ... Is she interested in men?” Aya at first demurs: “What do you think?” Noriko’s boss has seen indications both ways, and presses the question: “Has she always been like that?” Aya responds in the affirmative. The questioning goes on. Aya tells him that Noriko’s apparently never been in love, “but she has an album of ... Hepburn photos this thick,” holding her thumb and forefinger about 4 centimeters apart.

Here we have the first of two translation issues. Aya actually refers to “Hepburn” without mentioning a given name. The Criterion subtitles — by Donald Richie, who should have known better — make this a reference to Audrey Hepburn, who’d had only small roles by then. It’s almost certain that this is instead a reference to Katherine Hepburn, who was a major star by the time Noriko would have entered middle school. Was the teenaged Noriko besotted by the androgynous beauty of Katharine Hepburn (who would have made a stunning otokoyaku)? It sure looks like it.

The subtext now threatens to become text, as Noriko’s boss learns that “Hepburn” refers to an American actress, and asks the obvious follow-up question about Noriko. In the Criterion subtitles it’s translated as “So she goes for women?” The BFI translation puts it more bluntly: “Is she queer?” What is Noriko’s boss really asking? Japanese speakers can correct me here, but I believe his actual question uses the term “hentai.”

Western fans are used to thinking of “hentai” as referring to pornography. However, my understanding is that at the time of the film “hentai” in colloquial Japanese would have referred specifically to sexual behavior that was considered abnormal. So if Noriko’s boss did use the term, another possible translation might have been “Is she a pervert?” Both the Criterion and BFI translations soften the question; in particular BFI’s “is she queer?”, while defensible, risks projecting our current ideas about “queer” (including its positive connotations) onto a film created in a different time.

In any case, Aya is determined to shut down any discussion of Noriko’s proclivities. “No!” she firmly replies. Noriko’s boss is apparently unconvinced: “You can never know. She’s very strange, in any case.” His prurient instincts aroused, Noriko’s boss then envisions another solution to the problem of Noriko, and queries Aya about it: “Why don’t you teach her?” “About what?” “Everything.” “What do you mean, everything?” He pats her shoulder and admonishes her: “Don’t try to be coy,” as we viewers pause to consider the implications of what he’s asking her to do.

Aya rejects this line of inquiry as well: “Don’t talk to me like that! That was rude!” Noriko's boss laughs, offers a half-hearted apology, and then (after telling Aya that Noriko won’t be back that day) invites her to lunch and quizzes her on her preferences in sushi: “Tuna” she says. He continues, “How about an open clam?” (which Donald Richie's commentary helpfully informs us is a euphemism for the vagina). “Sure,” she replies. “And a nice long rice roll?” “No, thank you!” His final words are, “You’re strange too,” and again I think I hear the word “hentai” enter the conversation.

…

Recall that Kenkichi decided to accept an offer as a department head in a hospital in Akita, several hundred kilometers north of Tokyo and on the opposite coast. Noriko meets him in a café before her brother Kōichi is to host him at a farewell dinner party, and they talk about Shoji, Noriko’s other brother who went missing in action during the war. Kenkichi recalls how he and Shoji were best friends in school, often eating at this very café, indeed at this very table. Kenkichi tells Noriko that he still keeps a letter that Shoji sent him, with a stalk of wheat enclosed (probably indicating that Shoji was deployed in northern China). Noriko asks if she can have the letter, and Kenkichi agrees.

Afterward Noriko visits Kenkichi’s mother, while Kenkichi himself is still at his farewell party. Kenkichi's mother tells Noriko her secret dream (“please don’t tell Kenkichi”): “I just wish Kenkichi had gotten remarried to someone like you.” She apologizes and asks Noriko not to be angry (“It’s just a wish in my heart”), but Noriko stares at her with an intense expression (her usual smile absent), and asks her, “Do you mean it? ... Do you really feel that way about me?” Kenkichi’s mother apologizes again, but Noriko presses on: “You wouldn’t mind an old maid like me?” Then before Kenkichi’s mother can respond, Noriko speaks: “Then I accept.”

Kenkichi’s mother is incredulous. She asks Noriko several times to confirm what she’s saying, thanks Noriko effusively and weeps tears of joy at her good fortune, but continues to question Noriko about her decision even as Noriko leaves to go home. (Incidentally, this scene features a bravura performance by Haruko Sugimura.)

After she leaves the house, Noriko encounters Kenkichi, just returned from his farewell party. Noriko exchanges some small talk with him, but says absolutely nothing about what she just told his mother.

Noriko's decision then plays out across multiple scenes:

At first Kenkichi doesn’t understand what his mother is trying to tell him (“She accepted.” “Accepted what?”). When he finally gets the message (“She agreed to marry you. To become your wife!” “My wife?” “Yes. Isn’t it wonderful?”), he looks absolutely gobsmacked. His mother breaks down in tears again telling him how happy she is, and how happy he should be. He tries to play along (glumly echoing, “Yes, I’m happy”), but he looks for all the world like a man who would sooner eat nails than enter into another marriage.

Kenkichi’s mother doesn't understand why he’s not happy. She concludes, “What an odd boy you are.” The Japanese word here appears to be “hen,” which I understand to be a softer adjective than “hentai,” and not sexual in nature. But note that Kenkichi is now the third person after Noriko and Aya to be referred to as not normal in some way.

Meanwhile Noriko is interrogated about her decision by her family, especially by Kōichi, in a beautifully framed and shot scene — Noriko in white, her head bowed, her brother in black, barking questions like a prosecutor cross-examining a criminal. Noriko is unrepentant: “When his mother talked to me, I didn’t feel a moment’s hesitation. I suddenly felt I’d be happy with him.” Her parents retire upstairs to chew on their disappointment — Noriko walking silently past them on her way to her room — while Kōichi tells Fumiko, “What could we do now? She’s made up her mind. You know how she is.”

…

Meanwhile Noriko and Aya have their last scene together. It starts by echoing and completing the action at the end of their previous scene: then they raised their glasses together to drink, now they lower their glasses in a simultaneous gesture. Aya tells Noriko that she can’t believe Noriko would ever end up like this: she thought Noriko would be a modern woman living “Western-style, with a flower garden, listening to Chopin,” “wearing a white sweater, with a terrier in tow,” and greeting Aya in English — “Hello, how are you?”

Instead Aya now imagines Noriko wearing farmers clothes in rural Japan, speaking the local dialect. She playfully imitates country speech, and Noriko responds in kind: “Ya don’t look it, but ya talk like the locals.” “I figure to live in Akita when me and my man get hitched.” The subtext here I read as follows: Noriko knows how to pretend to be something she is not — a conventional heterosexual woman in a conventional heterosexual marriage — and she will accept doing so in her self-imposed exile from Tokyo, the price she must pay for avoiding what she considered to be a worse fate.

The tone then turns serious. Aya recalls meeting Kenkichi when they were in school, on a hiking trip with Noriko and her brother Shoji, and presses Noriko about her choice: “Did you already love him then?” “No, I had no particular feeling for him. ... I never imagined myself marrying him.” Noriko evades Aya’s questions about how she came to love Kenkichi, refusing time after time to acknowledge her feelings for him as those of love. Instead she insists, “No, I just feel I could trust him with all my heart and be happy.”

But trust Kenkichi for what? we want to ask Noriko. To respect her for who and what she is? To not want a conventional relationship with her? To not press her for sex or for children (after all, he already has one)? To keep her secrets, as she might keep any secret of his?

…

The family then gathers for one last commemorative photo. Without Noriko's salary they can no longer afford the house in Kamakura, so they break up: the parents to live with the great-uncle; Noriko to Akita with Kenkichi, his mother, and his daughter; and Kōichi, Fumiko, and their sons to some other less-expensive dwelling (perhaps an apartment in the Tokyo suburbs).

The parents recall when they moved into the house: “It was spring and Noriko had just turned 12.” Kōichi remembers that time as well: "She used to wear a ribbon in her hair, and she was always singing." But “children grow up so quickly,” her parents remark, and living together forever, "that's impossible."

Her usual smile nowhere in evidence, Noriko takes it all upon herself: “I’m sorry, I’ve broken up the family.” Despite reassurances from her father (“It’s not your fault. It was inevitable.”) she flees from the room, goes upstairs to her own room, and cries her heart out, distraught about the turn that her and their lives have taken.

The final scene shows Noriko’s parents at the great-uncle’s house, far from the sea. They glance at a wedding procession walking through the fields (“Look there. A bride is passing by. I wonder what sort of family she’s marrying into?”), think of Noriko, and resign themselves to the family's fate: “We shouldn’t ask for too much.” “We've been really happy.”

— Frank Hecker, “Ozu’s Early Summer Seems Pretty Darn Queer to Me”

#yasujiro ozu#ozu#queer history#setsuko hara#early summer#film criticism#queer film#gay subtext#queer coding#long post

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early summer at Summit Lake, a quick detour off the Highland Scenic Highway in the Monongahela National Forest.

From top: an unidentified fungi growing in a mossy nook; an impressive young Berkeley's polypore (Bondarzewia berkeleyei), which is not a true polypore but a member of the Russulales order; another massive Berkeley's polypore with my hand for perspective - these beauties can grow up to three feet wide and produce additional shelf-like caps from a single stem, giving them a tiered appearance as they mature; the tall and stately foxglove beardtongue (Penstemon digitalis), whose profusion of tubular white flowers draws hordes of long-tongued bees and hummingbirds from late spring to early summer; common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), whose large, dangling umbels of pink to purplish flowers are Mother Nature's ultimate pollinator buffets; swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata), also known as rose milkweed, a wetlands-loving beauty with narrow, lanceolate leaves; black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta), an irresistible summer aster with a prominent, dark brown button at the center of its flower head; and the sensual arc of a fireweed (Chamaenerion angustifolium), whose flowers have elongated, dangling stamens and a four-cleft, curling stamen.

#appalachia#vandalia#west virginia#wildflowers#flora#allegheny mountains#monongahela national forest#wv route 150#highland scenic highway#summit lake#early summer#fungi#berkeley's polypore#foxglove beardtongue#common milkweed#swamp milkweed#rose milkweed#black eyed susan#black-eyed susan#fireweed

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

same spot, four months :)

#midwest#missouri#nature#winter#spring#summer#early summer#naturecore#snow#woods#forest#forestcore#nature photography#my photography#my photos

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Woods in May I

#own photo#green#nature#forest#trees#walk#lensblr#spring#woodland#early summer#adventure#I said to a guy I see around here every now and then#that every spring#I think it's greener than it's ever been#but it's probably just me not remembering#this year the green feels breath taking#and it almost#popped#overnight#erm#tags#gloucestershire#uk#england#original photography

832 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early Summer, Yasujiro Ozu, 1951

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

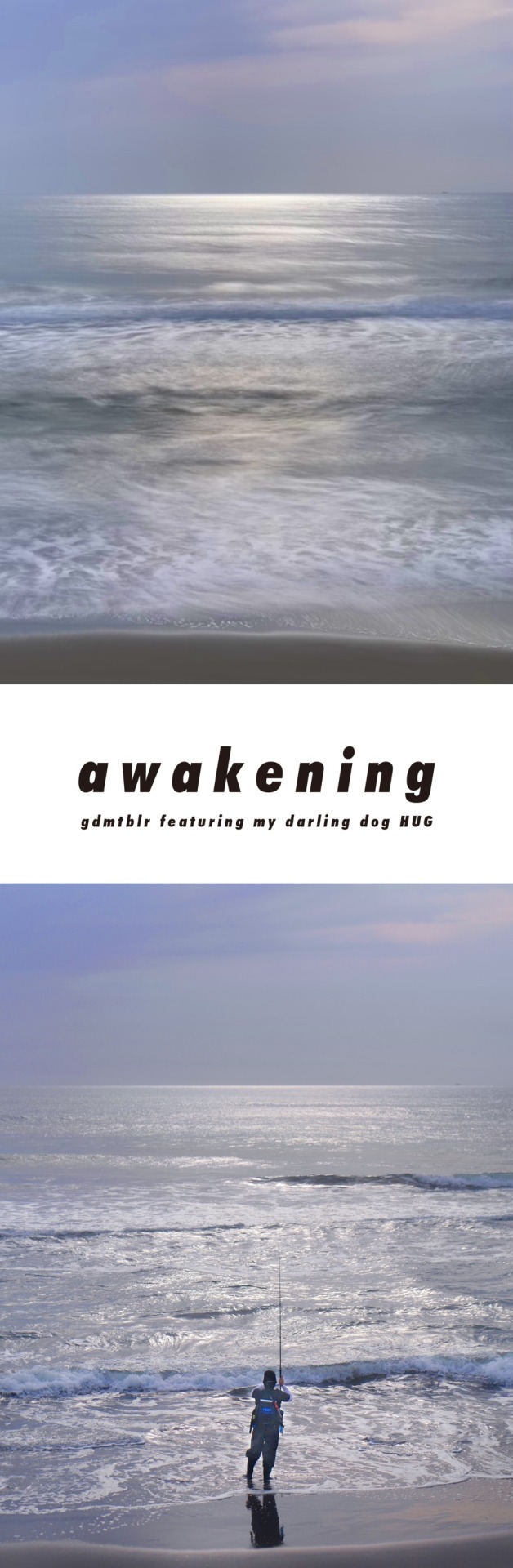

早朝の海へ。

ハグはまるで天職であるかのように、ひたすら貝殻拾いに勤しんでおりましたU(° ꈊ °)U✧キラーン!!

One early morning, I went to the sea with Hug.

She finds her ideal job in picking seashells🤣🤣🤣✨🐶🐚✨

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=Erhzyzyr4fI

#photography#dog portrait#my dog hug#early summer#seascape#Hiroshi Sato's album awakening is one of my favorite 80's Japanese City Pop💙#佐藤博

429 notes

·

View notes