#daughters courageous

Text

I was tagged by @norashelley, as well as @chantalstacys and @marciabrady (on my main) to post my to share my nine favorite first watches of 2023 (I know January's almost over alksdjfa). Thank you to all three of you for tagging me! I look forward to doing this every year :). I didn't watch that many new films in 2023 and most of the ones I watched were pretty darn bad lol. These were definitely the nine I enjoyed best, in chronological order.

💖 One Way Passage (1932), dir. Tay Garnett | A super well-directed film that's very somber in a good way. Bill Powell is also probably the most charming actor I've ever seen.

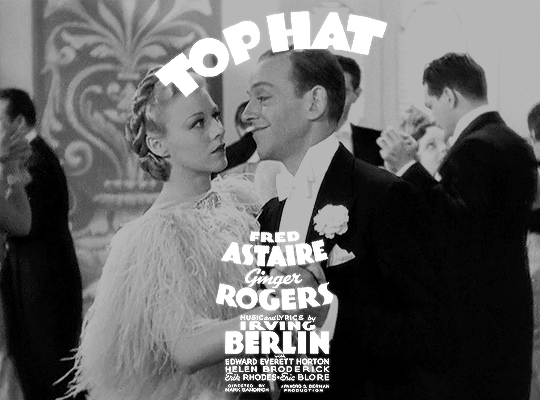

💖 Top Hat (1935), dir. Mark Sandrich | I just casually watched this on an airplane because I don't usually care much for 30s musicals or the kinds of characters I see Fred Astaire usually play, but I really loved him in this. I also don't usually like misunderstandings (a huge part of the plot is one big misunderstanding), but the film handled in it in such a comedic and engaging way.

💖 Daughters Courageous (1939), dir. Michael Curtiz | Literally the perfect romance movie made for me minus the absolutely heartbreaking ending :(.

💖 Mr. Skeffington (1944), dir. Vincent Sherman | I really love watching Old Hollywood romantic melodramas haha. Bette Davis and Claude Rains never fail to entertain, and this movie was also way sadder than I expected it to be (in a good way).

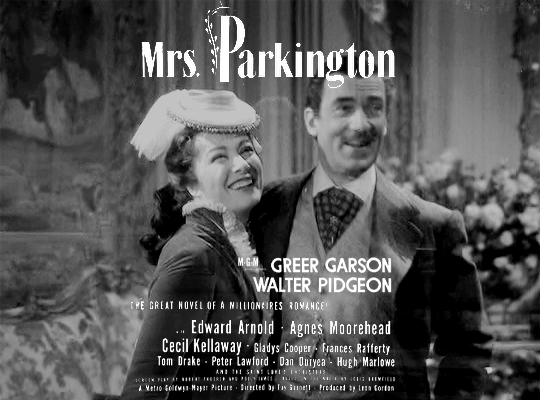

💖 Mrs. Parkington (1944), dir. Tay Garnett | A historical romance story made for me :'). Greer Garson is also perfect in everything, and I was so shocked to see Walter Pidgeon play such a domineering yet likable character. He did it so well.

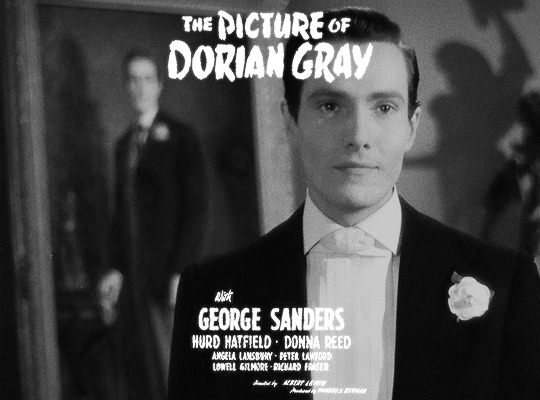

💖 The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945), dir. Albert Lewin | I enjoyed watching this movie more than reading the book 😅. Very well-directed. The cinematography is a work of art, and I love how so many things are conveyed visually instead of through words.

💖 Marty (1955), dir. Delbert Mann | I'd say that this is the only movie on this list that knocked me off my feet because it's so darn good. So beautifully understated and lowkey in its tone and subject and so tight in terms of acting and pacing.

💖 The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), dir. Henry Selick | Yes, I've gone this many years of my life without ever having seen this movie in full, and it was very good! I'm very impressed with how pleasant, likable, and simple it is. I love that it doesn't try to be anything more than what it is. It's so lovely and earnest.

💖 The Most Reluctant Convert (2021), dir. Norman Stone | I don't usually like movies with long monologues or dialogue, but Max McLean is a very engaging actor, and I like the extensive use of long shots. I also really enjoyed the scenery and sets; they're very pretty.

Tagging @sonnet77, @valsemelancolique, @glamourofyesteryear, @audreytotter, and anyone who wants to do it!

#long post#tag game#personal#one way passage#top hat#daughters courageous#mr skeffington#mrs parkington#the picture of dorian gray#marty#the nightmare before christmas#the most reluctant convert

19 notes

·

View notes

Video

Claude Rains in Daughters Courageous (1939)

Oh to be in love with a man born in 1889...

#YOUR HONOR I HAVE FALLEN HEAD OVER HEELS#the daddy issues have won#claude rains#daughters courageous#30s movies#fancam#starringvincentprice;posts

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part 2/7 💜📸📝

“I didn’t like the way he stared at her.”

“Who? Oh, Mr. Masters? I didn’t notice.”

“Well, I did. He’s still looking.”

“Who, Fanny?”

“Mr. Masters.”

“Don’t look at him, then.”

“Do you think he’s after her, George? I rather hope not, if I’m honest.”

“Why? He has a bit of money. And he’s clever.”

“But is he just looking for a wealthy socialite?”

“Well, he seems quite taken by your daughter’s beauty, and he wondered—”

“Why? I mean, why should he wonder?”

“He wondered if there was anybody— Well, that is, anybody she liked.”

“Did he ask you to find out?”

“Who, me? No, no. I just—”

“Well, you may tell him that we don’t like anybody in our house. That is, we like a great many people, but we don’t like men. Oh, we like men, too, but don’t like men who wonder about who else we Skeffington women like. My daughter is too young and far too clever to bother about who wonders about her. It’s ridiculous, that’s all. Ridiculous.”

“Why don’t you ask Mr. Masters to dinner? You can look him over and learn the worst. Give him a real chance, and perhaps you’ll like him even more than Sir John Talbot.”

“That won’t be necessary. An agreement between Sir John and I has already been reached.”

“Still invite him. You can size him up and he can size you up. If you don’t invite him, Fanny, then I will.”

You got eyes for Jim Masters, the chauffeur. Fanny had her suspicions, but there was some part of her that didn’t want to believe it. Manby said when you told your stories, Jim always made everyone be quiet so he could hear well. Jim was super likable. Everyone liked everything about him. You couldn't stop smiling when Jim started talking. The smiles you gave him made your mother want to puke. You smiled as if your relationship with Jim meant much more than the one you had with her. She’d never seen you smile like you smiled when you were around him. She told you to bring him to the house for dinner but you said he wouldn’t come because he was too shy and wouldn’t have time between his work, but Fanny wondered if that was the truth. Something changed. She felt it. It could have been so simple only if Jim didn’t get in the way. Both you and Jim kept saying nothing was going on between you. But she wasn’t about to believe everything was just rainbows and butterflies. In her eyes, Jim was using you to fill his sad, empty life. Fanny knew she had to do something. You’d been growing the idea of leaving New York since you came back from Berlin. Living with her didn’t help much with you being attached to your hometown. She and you never got to talk about it seriously, you didn’t really want to, but every time you hinted about leaving, Fanny tried so hard to ignore what it meant for her. Even those pictures in the morning newspaper were laughing at her... They were making fun of her impending doom. They were all saying,

“Ha ha ha. See? You’re gonna die alone here.”

She couldn’t let that happen. Then she remembered. Jim wrote secret letters to you. Manby got hold of the most recent one and gave it to her. In it, he was asking you to meet him. She locked it up so you wouldn’t ever read it. You weren’t allowed to see Jim of course and if you never saw that letter maybe you would think he didn’t like you anymore and maybe you would stop liking him. Your father would’ve known what to do. Fanny wished he was here. Unbeknownst to you, she knew where you kept your diary and letters. But they had no special meaning for her. Until curiosity got the better of her. What if you wrote something about Jim in your diary? What if your diary had something to do with Jim’s existence not just in your life, but in hers? She started digging. The first few pages were nothing outstanding. Just about your new school.

August 1932

When you live in one place your whole life, your next door neighbor is kind of like, your default friend. And Jeremy only got weirder over the years. With Janie Clarkson as his mother… I can’t put him completely at fault for how insufferable he was when he was a kid. Moving away has been a good excuse to...not see him anymore, but he did say he had plans to move out when he turned eighteen... I wonder if he’s going to follow through with those plans. Maybe he was just saying it because he was sick and tired of his overbearing mother and wanted to separate himself from her. Whatever his decision, hopefully the years have done him some good and he’s freed himself from his mother’s clutches. Hopefully he’s grown out of whatever his mother’s influence did to smother his individuality and corrupt his personality and behavior when we were in school together. Can’t say I don’t empathize with him. He and I share the same sentiment about our mothers. Maybe I'll give him a call to see how he’s doing.

September 1932

Starting at a new school is a right of passage at certain ages, yet when you are the only new person you feel that there is a spotlight on you. But in that attention there is a chance, right? There is a chance to find new friends to connect with. Going in with a positive attitude is easier said than done, but when you make a great leap, you have to commit to it, right? That's how you land with grace on solid ground. So this new school, I’m gonna make it be okay. I can do that. Starting at a new school is a chance to start over, to have a reboot of who I want to become, a chance to make new friends. On this first day of school I’ll go to meet my other family, the one I will spend years learning with. I will gain new brothers and sisters from various walks of life. I will become part of their community and begin that journey of growing into the fine lady I am destined to become.

October 1932

[…] As for now, I’m just gonna leave those POI on my ‘To Do List’ which is already filled with a crazy amount of homework. I now know why youngsters of Zurich will try their best to get as far away from school as possible after class: to escape from choking on the pressure that teachers give them! Even on weekdays, pretty girls like Stephanie will have their boyfriends give them a ride, and others make use of the power of PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION to get to the more crowded part of town. It does feel too quiet since I’m no longer in public school, but at least I don't feel as lonely as I did in New York. At least I don't have to watch everyone I know turn their faces away like I’m some kind of a demon spawn. At least I don’t have to be reminded how fucked up things can be in a single moment.

November 1932

[…] but people in this town see graffiti as nothing but trashy doodles. I want to show the hidden side of girls—their impulses, their urges. What are YOU hiding inside…? Fanny, Uncle George, Father… they all tell me, “Don’t worry about what people think. Be proud.” How could I ever be proud of myself…? My classmates talk about me…

“Well! I don’t think you suffer as I do. You don’t have to go to school with impertinent girls who label your father just because he’s Jewish.”

“If you mean libel, then say so, and stop talking about labels as if Father was a pickle bottle.”

“I know what I mean. And you needn’t be satirical. It’s proper to use good words and improve one’s vocabilary.”

“Vocabilary?”

Father told me that it’s important to have goals in life. I wonder what life goal I should have. I wonder what Father’s goal is. Might not be a bad idea to leave town, actually… The great thing about graffiti is, the world’s your blank canvas, your home, begging for you to paint it with your hopes and dreams. I can have fun anywhere. Maybe that should be my goal. I’ve decided that’s what I want to do with my life. I’m going to travel the world, painting, photographing, and documenting my own finds! Well, as soon as I’m old enough to escape Mother, that is. There was an explosion in my brain... the good sort... the type that carries more possibilities than I could be conscious of... but there were hundreds of ideas there in that buzz of electricity... I could feel it. It was the calling card of adventure, of paths awaiting my feet.

Fanny kept flipping through the pages, until she found what she was looking for. It wasn’t even a challenge. She saw just how far back your and Jim’s affiliation went. It was beautiful. She found the perfect story, all she had to do was fill in the ending.

September 1934

So funny to find this diary again! I must have forgotten it at the bottom of the drawer during my travels. I still remember how innocent I was then... So many years ago... I remember being thirteen going on fourteen. I wanted to learn photography, so Father hired Rupert to be my tutor. At first, I thought he would be too old to teach. Plus, his techniques were probably too ancient. But when he came, I was surprised that he was a very humble person. Despite our age differences, we talked for hours. I felt comfortable around him. Then he showed me the photos he took. They were beautiful. It was around that point that I figured out that Rupert was perfect as a tutor, that I shouldn’t have been so quick to judge the old man. I'm glad Rupert was my teacher. I spent nearly five years under his tutelage and it’s paid off! Though I am only eighteen going on nineteen and will never get a degree in photography, Rupert said I’m a professional in my own right!

September 1934

Today I climbed a great pine tree at Wakeforte Park to try to get a shot of something. I can’t remember what I was even trying to photograph, but I didn’t realize how far up I had climbed until I fell out of the tree! I met a kind man when I hurt my leg. He rushed over and helped me, asking if I was okay and if anything was broken. Luckily, nothing was.

You know that feeling where the first moment you see someone, it's like they have a big gold star around them, and you have to get to know them? Well, there's this man. I had no idea how I would ever, like, have an excuse to talk to him... until he opened his suitcase to take out some bandages and I noticed all the pictures, stickers, and souvenirs that decorated both the outside and inside of it. He was a seasoned traveler from the looks of it and, when I mentioned it, he said he just came back from a trip in Hong Kong a month ago and he was now visiting Switzerland. Just passing through, really. Maybe I should have been frightened of him. This older man who saw that I was alone, who possibly felt like I owed him something, which was the worst thing a man like that could feel. He looked grim, all right. I could see how his face might frighten a lot of people, but I couldn’t imagine being afraid of him. Somehow, I... I rather liked him.

“You have a very bad habit of climbing trees. This is no place for children.”

“You think of me as a child? Well, you’re wrong. I am much younger than that!”

“You think my face frightens people, do you?”

“Did I say that out loud?”

“Yes. So you must’ve been thinking it.”

“Yes... sir. Frankly, I do. You understand, I don’t think you mean to frighten them, but your face— Well, you asked me, sir, and, yes, I do think so. But you don’t frighten me. You intrigue me. You’ve been to Hong Kong, huh?”

“My girl, there’s no spot on this earth I haven’t been.”

“Tell me about your time there. What was it like? What did you do?”

“Well, I confess once in Hong Kong when I was desperate I sold a relic of which I was only a part owner.”

“Yeah?”

“Mhm. Being a citizen of San Francisco I sold my share of the Oakland ferry to an Australian who wished to make a gift of it to his fiancée. And a very lovely fiancée. You know, she had the most beautiful… Well, that’s another story.”

“I’ve bet you got a satchel full of stories.”

“Mhm. I got the stories, all right. Trouble is, finding somebody who’ll listen.”

“Well if there’s a couple of bottles of beer around, I might be persuaded to lend an ear.”

“If there isn’t any, I’ll make some. Drink up, my good woman. The Earth’s a savage garden.”

“…It was the third day. I had fallen in with a group of Moorish travelers. One of them was suffering, struck with the curse of Scrofula, so I prayed with them for her fortitude, that she might reach the Cave of the Mother with all speed. They told me that a temple was within two day's journey, should all go well. Yet there was an obstacle still to overcome. The path went through the demesnes of one Idris Hannachi, a robber-baron of the Ottoman people. Pilgrims had to pay a heavy tithe to use his water, and to travel the mountain pass. I had spice, and three thalers left. I prayed it would be sufficient…”

“…Nigh a tenday I’d gone without honest fare worthy of the name - drank naught but what the sky offered for my thirst. Why, some bread, cheese, and a cup of wine would’ve appeared unto me a feast! Surely those fine people wouldn’t begrudge me a mite of rest and repast before I got ‘out with it’? Fine, fine. I turned a deaf ear to the clarion calls with which my scorned stomach beseeched me. Graver matters were at hand. Plenty to digest, after all. A good deal to stew over, if you will. Words ladled with import should be savored so as to better absorb their meaning, wouldn’t you agree?”

“…And so I drank the native wine, signifying eternal friendship. It was a touching scene as I bade the Mahabus farewell. For eight years, I said, I’ve been your chief. I give you modern plumbing, surrealist art, and a smattering of air conditioning. I hope that in time you forgive me. And so I leave you, before I bequeath you any more of the horrors of civilization.”

“I’ve listened to you for two hours. And two hours more solidly packed with bologna I’ve never listened to in all my life.”

“Well…perhaps I did lie a little. I like my stories. Like to hear myself talk. I like a little drama, I do. Mind you, lately there’s enough of it about. Do you know, my dear, as you grow older, you’ll find there’s nothing fuller than the truth. The whole truth and nothing but the truth.”

“You’ve kicked around the world all this time and you got nothing out of it at all. I wanna see this world too. That’s all I care about. I wanna get out of this hole. But it’s not wanderlust with me. Who cares about what New York or Copenhagen or Singapore looks like? They probably all look like Sacramento.”

“They all do. Except Sacramento.”

“What’s going on in this world? Things are happening all around us. Why are they happening? You ever seen so much hate in one universe? Well, who sets it off and why? You read this in the papers and that. One person tells you one thing and another person tells you something else. Well, who’re you gonna believe? They all got an axe to grind. I’m shut up here. I know from nothing. But I’m gonna find out. I’m gonna find out for myself. And let me tell you one thing. They won’t keep me in the dark.”

“Well, listen. Don’t take it out on me. I’m not keeping you here.��

“I’m sorry. I get too excited. Let me tell you another thing. When I find out, I’m gonna do something about it.”

“Okay by me. And with that, you rather like me, do you?”

“Yes, I do. I really do, in spite of everything.”

“And I like you.”

“What is your name, please?”

“Don'’t you think secrets are fun? Just refer to me as a wayfaring stranger.”

“But I owe you so much for coming to my aid. I should pay you back somehow.”

“You are paying me back by lending an ear. I want to know who’s letting me talk her ear off. You haven’t told me your name either.”

“Don’t you think secrets are fun?” you parroted his words back to him with a smile. “Just refer to me as an ambitious tree climber.”

“It sounds so mysterious. From where do you come?”

“I am of the wind whose sound is heard, yet none can tell from whence it comes or where it goes.”

“Well, the next tour group gathers within the hour. Try not to blow away before then.”

When I was a girl, Dad always told me to not trust strangers, especially men, but I’m a woman of eighteen, soon to be nineteen now and I don't think he’s a bad guy. If he was, why would he go out of his way to help me? They do say we sometimes become friends with those who are at the opposite ends, so maybe it's not such a weird thing. I’m exhausted but hyped up beyond my limits. I can’t sleep. How can I when the whole day just feels like a dream? Maybe if I meet him again at the park, I can tell him stories of my own.

October 1934

I’m finally focused on my studies, so I think I might pull an all-nighter. It won’t be good for my skin (I can just hear people calling me "troll" and "nerd"), but I don’t care. I have to make it to college. Dad is counting on me to do well. I’ll make him proud by getting into my first choice. All right, time to hit the books till morning! My future isn’t in Switzerland or New York, it’s wherever college life is waiting for me. Everything’s riding on my entrance exam next year. I have to get out before I go stir-crazy.

February 1935

Today I went to Wakeforte Park again, and he was there! I raised a hand to wave and he spied me in an instant, sitting by the water fountain as I was. His face split into the grin I had imagined him to wear often. Then he came over in fast, easy strides and took my offered hand in his two, shaking and squeezing. I hadn’t seen him in over four months. I thought I was imagining him at first, seeing things. But it was him! I told him about the book I read last night. It was about the species of plants and flowers and that even now not all of them are discovered! I told him I want to be the one to discover them, but I’m not good at science. Then he said if I don’t give up, I can do it. I’m happy I told him. It was as if no time passed between us at all and we picked up right where we left off. He finally told me his name - Jim. Jim Masters. I like being with him. I can be myself in front of him. He doesn't judge me, or tell me what to do. He cares about what I think. He makes me happy. He talks a lot to me recently, and I feel comfortable whenever he’s around. I can be myself in front of him. He said we could meet here at Wakeforte for as long as we’re both in the area. I wonder if this is what friends are like.

“Where were you born?”

“The corner of Market and Cherry Street. Same hospital my father was.”

“Market and Cherry? Where's that?”

“Foot of the East River. It's about ten miles, I should say, from the nearest governess.”

“How do they call you?”

“Skeffington.”

“Curious name. Skeffington. That’s a strange name for Market and Cherry.”

“You mean, is that my real name? Yes and no. When my father was a child and he came over with my grandparents, the immigration official on Ellis Island wasn't a good speller...and ‘Skeffington’ was the closest he could get to Skevinzskaza. That’s my father’s real name. But Skeffington is what he goes by, so it says Skeffington on my and my sister’s birth certificates.”

“Market and Cherry… That’s in New York, isn’t it?”

“It is. I grew up on Charles Street.”

“You are far from New York, Miss Skeffington. Do you miss your family back home?”

“There’s not much of a family to miss. My father and sister are here, and my mother and Uncle George are back in New York. There’s my aunt, Martha Tintagel, but she lives in London, so I’m not very close to her. I’ve only seen her face on Christmas cards and such and have never heard her voice or met her in person. She’s a Lady and has a husband and three children - two boys and a girl. She’s a happy mother, always wrapped up in them. She loves being tied up, and is sure she can’t stand five minutes on her own feet unassisted. My other aunt, Nigella Pontyfridd, is wife to my Uncle George, but she kept her maiden name and they have no children. She doesn’t mind, though, because her heart is full to the brim of Uncle George. They’re not really my aunts and uncle, though. They’re my mother’s cousins. We’ve just always called them that for simplicity’s sake. As for everyone else… They’re dead. And they died before my sister and I were born, so we never knew them. Anything we know about them comes from the word of others. I miss Uncle George and Aunt Nigella, but my mother…”

Sensing that you didn’t want to talk about it, Jim changed the subject. “You have quite an art studio here. Did you bring all these art supplies from America?”

“A few of them.”

“May I look at them?”

“Of course. I even painted something for you to take with you on your journeys. Something to remind you of me.” You showed him the painting. It was small, a miniature portrait really, but the detail was exquisite. It was a painting depicting the exact spot you met, more specifically, the tree you fell out of and the surrounding area.

“This is beautiful. Looking at this, I can feel as if I’m actually there. You know, some works are so familiar. Looking at them is like being home again.”

“That's a nice music box you got there.”

“Most of my belongings I could bear to leave behind. I sold almost everything I owned to get my passage to come here, but this… Never. It's one of the few things I brought with me from the States. I will carry it with me everywhere I go.”

“What’s that little song playing?”

“Do you like it? A man composed it for a young violinist he once knew, a girl of infinite beauty and sensitivity. So far apart in age, yet a pair of misfit beauties they were. I can see why they both ran to the other. As for this… A remarkable painting by the hand of an even more remarkable painter.”

“You flatter me, sir. But I’m so happy you like the painting. I was thinking of you when I painted it. I knew you’d be able to tell.”

“Why do you always call me ‘sir’? You know my name.”

“Well, perhaps if I saw you oftener than once every two or three months. When you happen to be passing through.”

“If you think it’s on my way, you’re mistaken. When I left Spain my tour required I proceed direct to Paris. So…you see?”

“Then take me with you, please. You promised.”

“My dear, an attractive woman doesn’t go to Paris. She lets Paris come to her.”

“Meaning you, I suppose? You are so wise and so clever. Paris is a good place for a new life. I believe Paris is where you go to reinvent yourself. Will you be returning to Sacramento, Mr. Masters?“

“For God’s sake. Jim. Call me Jim. Please. Mr. Masters was my father.”

“Jimmy,” you said teasingly with a smile to match.

Jim laughed but then turned serious. “No. Jim.”

“All right. Jim,” you said, liking the way his name sounded on your tongue. “I better get going. My sister, Fanny, is waiting on me. Goodbye, Jim.”

“And when may I have the pleasure of seeing you again?”

“When Paris no longer comes to faith,” you teased him again before walking off.

Since he was heading out soon, he offered to give me a tour of the city.

“I was just going.”

“I’ll walk home with you. I’m afraid I’ve neglected my gentlemanly duties too long. Maybe I ought to go in and say goodnight to your old man and sister, huh?”

“Now listen. If you’re going to come around here to see me, you’ve got to promise to be friendly with my father, but not too friendly with my sister. While I want her to like you just as much as I want Dad to, she’s the pretty and sweet one of the two of us. We’re twins, but we’re nothing alike, you see. I wouldn’t be surprised, but I’d be greatly disappointed in you if you fell in love with her at first sight.”

“Who says I’m coming around to see you?”

“Who says you’re not?”

“Are you a natural brunette?”

“Practically. A chocolate rinse now and then.”

“I’m taking the boat out tomorrow at six. The main wall.”

“I’ll be there.”

“If you’ve got a good book, stay home and read it.”

“I don’t like reading. I was never much good at it in school. I couldn’t stand the snobs with impeccable taste. Still can’t. These people say: ‘I'd rather a good book than a shallow person’. They could cry over the plight of a fictitious character but they shamelessly insult real people because real people are ‘shallow’ and according to snobs these ‘shallow people’ don't deserve to live.”

“You don’t like reading? But last time we met, you told me about a science book you liked.”

“That was an exception to the rule. I can read, but only because of the efforts of my former psychiatrist, David Jaquith, and his wife, Charlotte. Adventure is allowing the unexpected to happen to you. Exploration is experiencing what you have not experienced before. I prefer spending my time doing something and actually experiencing it, instead of reading about it in some book. Do you know what I mean?”

“I think so. In that case, I guess…I guess I should let go of this. I won’t need it after tomorrow. Just one final reminder of bad memories I can do without. You can take this. I've already read it. If you read this and tell me what you think of it, that bad memory will become a good one.”

You looked at the cover. “Pulp horror fiction?”

“Yeah…sorry.”

“No, not at all! It’s my guilty pleasure.”

“Mine too. This one's great, You ever heard of Henrik Creighton?”

“I can’t say I have.”

“Oh! Well he—”

“Wait, we’re getting off-topic. Why did you mention taking the boat out if you don’t want me there anyhow?”

“All right, all right. Be there. Make that five instead of six. And uh, better bring your book along.”

“I’m sure there’ll be no need. You’ll have plenty of stories to tell me.”

“Don’t forget my jacket! It might get chilly later on,” Fanny called after you just as you were about to rush out the door for your…outing…with Jim. You didn’t want to call it a date. It wasn’t a date. Just a tour around town with a friend.

“You’re a darling. Wish me luck.”

“Aren’t I going to meet him?”

“What? And have him wonder why he picked me? No, you’re much smarter and better looking than I am. I’m only the intuitive one. We’re going out for dinner afterwards, so you don’t need to wait up for me.”

“I’ll wait up. If I want to.”

“And what will you tell Father when he asks?”

“Don’t worry about that. I’ll handle him when he gets home. Although you might have to tell him something when you get back. The truth, preferably. I might not wait up for you, but he undoubtedly will.”

“I don’t know why I’m making such a thing of it. You’re right. I could tell him the truth and he wouldn’t mind very much. He’d be happy I have a friend here.”

“We better not waste any more time dawdling. Isn’t Jim waiting for you outside?”

You gave her a quick kiss on the cheek. “You’re right! Gotta go!”

Out the window I could see the weird gigantic hill that was also visible from Jim’s motel room. He revealed that it's his secret base of some kind since few people actually visit Wakeforte Park and the surrounding area. He jokingly said he could take me there when I’m old enough. After dinner, Jim dropped me off at home and drove off. The second I went inside and closed the door behind me, Fanny was there waiting for me. She was sneakily watching me and this mystery man of mine from the window and now had a million questions. It was impossible to keep anything from my sister.

“Yoo-hoo! Hey, anybody home? Fanny, where’s Father? Isn’t he home? Is he asleep?”

“No, he’s still in Kreuzberg. There was a mixup and he has to take a later train. He called to tell me he’d be home tomorrow and to let you know. Lucky you!”

“Fanny, don’t tease.” Your admonishment was more playful than serious and Fanny knew that.

“Why, darling sister, who is he? Where’d you meet him?”

“Look, Fanny. I met him five or six months ago, but I’ve really only known him for two weeks at the most. He travels a lot. When we do meet, it’s mostly by chance. Well, he just came back last week. He's so handsome.”

“Where’d you meet this time?”

“He was with Mr. Hunneker. He drove up in a great, big, gray car.”

“Mr. Hunneker? As in Hamilton Hunneker, the Polo player?”

“That must’ve been the one.”

“Sister, you say the handsomest...”

“Well, make that the most distinguished.”

“Is he tall?”

“Well… Yes and no.”

“Is he young?”

“He’s young enough.”

“And he’s rich?”

“He is as poor as one might imagine an itinerant philosopher to be. Yet, as the hours go by I see that he is unfailingly generous to me. I am grateful to have a friend.”

“What did you say his name was again?”

“Jim. Mr. Jim Masters.”

“He can’t be so very rich.”

“He’s comfortably moderate in his money, But he’s rich in knowledge and experience. He asked me to go sailing with him Friday night. I accepted.”

“You didn’t?”

“I did.”

April 1935

I got some materials from my first choice in the mail today! I really want to be a college freshman at the Roski School of Art and Design in Southern California! If I got in, I’d be so, SO HAPPY! Dad, I’m going to work my ass off and be the best daughter ever! Thank you so much for everything!!!

May 1935

I’m so stupid sometimes. I was telling Jim that I was applying and hoping to get into my summer college program thing, and I was all making plans, telling Jim he should come visit me, stay in my dorm room. But he said, “Darling, I leave on June 6th.” I was like... “leave? You’re going? To where?” He said, “To Peru! What did you think I was doing all that stuff for?” I guess he’s been planning to continue his journey. And I guess he’s really going to do it. So I said, “I’m just... never going see you again?” He said, “Let’s just have fun while we can.”

May 1935

I asked Jim what he had to do to get ready for his trip to Peru. He said, “Not a lot, really. As a rule, I don’t allow myself to bring too much with me— the more I carry, the more slowed down I become. I have only a few possessions, but unlimited contact with the outside world while I’m…on the road, so to speak. I just wander every day. And then I keep on wandering from there.” So.. he’ll just go away. To Peru and then… to who-knows-where. The other side of the country? The other side of the world? My mind can't process it. That he’s really going to be... gone. Just gone.

June 1935

Jim had his going-away party with me tonight. He’s so incredible... When he was telling his stories, I could practically forget...everything... That we only had forty-eight hours left... That I don't know what comes next... That I can’t live without him. Then, he dedicated the last story...to me. And I couldn’t take it. I was out on the curb in the alley, sobbing till my ribs hurt. I would follow him anywhere. But I can’t, not where he’s going. After a long time he found me. He said he was sorry. He said, “I wish things could be different. I just wanted to make you happy.” I said, “I don’t think you can anymore.”

June 1935

We agreed our last night together would be our happiest ever, and we’d forget tomorrow was going to come at all. It worked for a while— We had a good time seeing Gabriel off, then ran up to the attic to look through our photos, to find one for Jim to take with him...and looking at them, I realized they were all in the past, and there wouldn’t be any more, and I didn’t know what I was going to do, and I cried, and he held me. He said he knew it was hard, but life would move on. I said I didn’t want my life to keep moving without him. That’s when he cried too. I was so exhausted, I must have fallen asleep like that, in his arms. In the morning, I woke up, and I was finally alone. I thought I found my happily ever after, but it was all a dream. I have to get out of here. I want to disappear. But where would I go? This is all a bad dream. This is all a bad dream. This is all a bad dream.

Darling,

Meet me at our secret place in Wakeforte Park. You know where. I need to see you one last time before I go to Peru. From there, I’ll go to Greece to make myself worthy of you. Be assured, my darling, it is you I want, and not your family. Please, do not do anything we will regret. Just in case I’m held up and can’t get away to meet you in time or something, I will leave a message for you with your sister so she can give it to you. It’s a puzzle, a sort of belated birthday gift for you. In that puzzle, you’ll have to visit both yours and my favorite locations in Switzerland. In each location lies a clue that I had written on the wall of the building exterior. The clues, when put together, will point to you the location of your gift. I thought it was a neat idea. I like vexing your brain, because when you are thinking real hard, like when you’re trying to capture the perfect shot or drawing the perfect subject, you are more beautiful than anything in the world. You’re always drawing in that sketchbook, looking so intense. While I’m gone, you can keep busy by looking for what I hid. Start by using this piece of paper to mark where all the rock pictures are. They will tell you what to do next. Your favorite flowers, start keeping them in mind too. Find my hidden treasure, darling. It’ll explain everything better than I could before.

Your friend,

Jim

June 1935

Dear Miss Skeffington,

After carefully reviewing your application, we regret to inform you that we are not offering you admission to Roski School of Art and Design. We realize that this decision may come as a real disappointment. We also hope that you will understand the decision as a reflection only of the extraordinary talent represented in our applicant pool, not a judgment about your own abilities. This year’s pool of applicants was the largest and most accomplished we’ve ever received, making our decision very difficult. Although we’d like to extend admission to all our applicants, we have limited space in each admitted class. Of the more than 19,000 individuals who applied to Roski School of Art and Design, most are fully capable of doing successful work and making a unique contribution to the Californian community. It is painful to us that we must turn away so many superbly talented students. You may be tempted to ask what was lacking in your application. In truth, it is usually difficult for us to point to obvious weaknesses, when so many applicants have demonstrated real achievement and potential for the future. Our decisions say far more about the small number of spaces available and the difficult choices we make than they do about a candidate’s personal and academic promise. While regretting that we were not able to respond positively to your interest in Roski School of Art and Design, we want to wish you every success in your educational pursuits. Experience suggests that regardless of our decisions, most of our candidates will be welcomed by other outstanding colleges. We acknowledge the time and energy put into your application and congratulate you on your academic accomplishments. We invite you to reapply in the future and extend our best wishes for the coming year.

Best regards,

Roski College Admissions Team

All that hard work was for nothing?! No way! I can't stay here! I can't be stuck here in New York with Mother!

June 1935

Jim is gone, and I can’t stop reminiscing on the time I spent with him. It all happened so fast. I was outside in the park reading when Jim appeared out of nowhere (again). He said “hello” and I started telling him how I actually enjoyed the book and how I never read the same book twice in my life.

“Well, I’ve come to entertain you. I’ll read aloud, and you can listen. I do love to read aloud.”

“I’d rather just talk, if you don’t mind.”

“But this is German romantic philosophy! We throw off all our constraints and come to know ourselves through insight and experience. But it got out of fashion now.”

“Not in the Skeffington family, I’m afraid. It’s just that there comes much emphasis on perfecting oneself.”

“Ah! This gives you a problem?”

“I’m hopelessly flawed.”

“If only we could be ourselves without perfection, like your poet, Walt Whitman, who rides up and down the streets of Broadway all day shouting poetry against the roar of the carts. ‘Keep your silent woods, O nature. Your quiet places by the woods. Give me the streets of Manhattan.’ I think we are all hopelessly flawed. Oh, no. I love to talk, too. Very well. Let’s talk.”

Ten minutes later we were passing Bess’ Bakery. Home of the world famous Belgian waffles. “You’d find no better waffles than in Belgium itself,” said Jim.

There was also a gym across the diner. Fanny hated those kinds of places because they were teeming with creeps. I found my own POI: a bookstore! It was weird seeing a bookstore and a gym standing side by side though. At the end of the tour I finally got to taste that sweet Belgian waffle Jim worshipped. I miss Bess’ Bakery. Fanny never shut up about its doughnuts when we were children. The doughnut shop was her MUST GO TO place. Personally, I enjoyed the blancmange we’d get at another little shop. It was soft, so it would slide down easily. So tasty. But the doughnuts DID taste sweet. Just like Jim’s heart. Each bite was another memory to savor. But just like a doughnut, it had an expiration date. It turned cold and bitter. I miss its warmth. I miss its sweetness. I need it. I need to eat it up.

Why? Because after all those months, I just can’t forget about what used to be the light of my life. (I know. Overdramatic, much?) Resonating with Jim as much as I did is bound to leave that big chunk of residue. Let’s just say this diary is what’s left of our relationship. I miss him. Even when I’m with him. I see him. Even when he is not looking. As the time we spent together grew longer, one question kept on growing with it. What does the ME in Jim’s eyes look like? Does he see me as I see him? Does he see me as I see myself? Does he see me as I want him to? Things were so much easier back then. Jim could just say, “Hello”, and I would say “Hello”. Nothing but spending time together after that, with the occasional visit to Wakeforte Park. We had such a good thing going.

Every time I was around Jim, my head spun faster than a tornado. I didn’t “get” Jim sometimes. Like, his walk and his talk and everything were all “anti-authority,” but he said he was in JROTC and did drills in perfect formation, following orders, no question. He went to join the Army and had to lie about his age, about who he was. He said, “they didn’t need to know what they didn’t need to know,” like it was no big deal. This coming from the man who punched a man so hard the poor bastard was knocked out cold to defend my honor... I learned when to stop arguing though. I don't think Jim “gets” Jim sometimes. The person I saw depended on who he was talking to and what he wanted. He could be everything from invincible to vulnerable, albeit with a new story of each new situation. He had an infinite number of childhoods. His parents were happy, divorced, fighting, abusive, or dead. His father had been a banker, a road digger, a burglar, or unemployed. His mother had been a drunk, a politician, a Sally-home-baker, or a tart. He was an only child, the last of eight, brought up in a foster home or the heir to a fortune. Part of me wanted to walk away, but I was the only one he could tolerate. Why? Because I never asked to see behind his ever-changing disguise. Inside that body was a kid, a kid locked in at some emotional age far younger than his forty-something exterior. I’ll never know what happened to him but, whatever it was, it just stopped his development at that age. It was a one-way friendship, I knew that, but he needed someone.

July 1935

At night when I kneel to say my prayers I rest my elbows on the hope chest Uncle Fred gave me for my eleventh birthday. “We’re going to make a family someday, just you and me,” you’d said. Inside that chest are our dreams, Jim. I’m keeping them safe on my end, so you do your part over there and we’ll be right as rain soon enough. Moving on won't be easy but as long as I keep myself busy it won't be that hard. As for my weekend plan... I’ll just improvise in the morning. Write you later!

“Doesn’t it feel odd to have the rooms back? And only asked to sit in them. I suppose we’ll get used to it.”

“I don’t want to get used to it.”

“What do you mean?”

“I know what it is to travel now. To walk around for a full day, to be tired in a good way. I don’t want to start dress fittings or paying calls or standing behind the guns.”

“But how does one escape all that?”

“I don’t know yet. Oh, Fanny, truly I don’t know if I could ever be good like Father. I rather crave violence. But I’m not dreaming of hitting anybody. I’m just unhappy.”

"Then you’d better have your tea while it’s hot.”

“I’m sorry. I didn’t mean what I said before. You’re not just as shitty as them. It’s just that I feel very lonely and overwhelmed. But I love you. I’m just unhappy, indeed,” you sniffed. “If only I could do like Father did and go to war and stand up to the lions of injustice.”

“And so Mother does in her own way. And Uncle George, with his charities.”

“Yes. But I want to do something different! I don’t know what it is yet, but I’m on the watch for it.”

“You’ll find it. And thanks for the apology, sis. I know it isn’t ideal living in this house… But I’m here for you, no matter what.”

“No matter what, huh? Let’s both go back to bed, Fanny. I’m tired.”

“Sure. Goodnight.”

July 1935

Let’s see, Dad. I hope your dear friend can help a girl out. Come on Corporal Mark Pearce, I’m counting on you. Ahem. ‘Dear Miss Skeffington, my dear, I remember your father well and am forever in debt to his many sacrifices in the name of freedom. He was a frank man, so you’ll forgive me for being frank when I say that he'd have a conniption if he knew I put his sweet girl in the line of duty.’ W-what? Fa-Father would be proud of me! I’ve had more conniptions in my first twelve years of life than Father has had in his entire lifetime! Oh, well. No point in having one over the first rejection. If at first you don’t succeed, try again. Back to the drawing board.

July 1935

Aha, the WASPs! Boy, I’d like to slip into the cockpit of a Twin Beech! ‘Thank you for your interest in the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots. Unfortunately, all of our WASPS must be at least 21 years of age, at least five feet and two inches tall, in good health, in possession of a pilot’s license and 500 hours of flight time. Our records show you do not meet all of these requirements.’ Well, that’s just FOOLISH! I’m a fast learner and… Oh. No use crying over spilled milk! Once more unto the breach!

August 1935

From the office of Harold Perkins. Oh yes, the fellow from the local recruiting office. Surely they’ll have something for me to do overseas. ‘Dear Miss Skeffington, We appreciate your numerous requests to be placed in the field, but believe me when I say the most action you’ll see is from behind a desk.’ Excuse me? ‘I’m sure you’re a top notch typist, so why don’t you come down to the Boston—’ Typing? I wonder what an itchy trigger finger would do to a girl’s word-per-minute. Oh, cheer up! Miss Skeffington, you’ll get there yet. No point in being all down in the mouth. Mother might begin to suspect something. She almost did at dinner. “Tsk, tsk, tsk, tsk. You’ve barely touched your plate, my love. Go on, have some more,” she said. She’s got a point. My body needs the vitality for action.

August 1935

To trust yourself when all doubt. To lead from a danger only you can see clearly. To explain enable the blind to see. To give people the power to hear the extraordinary in the ordinary, the everyday and normal encryption of the spoken word. To show them the messages and conversations that happen all around us to different levels of the brain. That’s quite the challenge. That’s quite the challenge when, until you can prove it, they will think you mad and threaten you with the consequences that come to the insane. To speak and risk the twisting of the knaves of sophistry. That is what they ask. Last time I complied I almost died. I almost lost everything for nothing. So, tell me again why, tell me why this is the time, because even if it is now or never, I won’t act unless I can win. I know more than most what these adventures into the world of the saviors costs...and the cost is never to myself alone. You know what? I do trust myself. I do. It’s every other bastard out there I don’t trust. This is a world of monsters. So many monsters.

Those bastards. Kraut…bastards. You don’t belong over there. I do! When I find that gun I’m going over there and there will be hell to pay! Oh, for Heaven’s sake, where is that gun? Now, Dad, don’t you fret. I’ll find that gun lickity split. No soldier worth his salt ought to carry those shoddy government-issued pistols. Plastic handles? Pshaw! Give me checkered walnut any day. Practice, practice, practice. I don’t need fancy tools to disassemble a gun. See the cartridge here as a screwdriver. Just like Uncle George showed me. Next time, we should get a stopwatch and have some fun.

September 1935

Women’s Army Auxiliary Corp, you’re my last hope. ‘Dear Miss Skeffington, thank you for your enthusiasm. While we are always eager for more Women’s Army Auxilary Corp, we are unable to offer you—’ …malarky! Fine. Let’s see what I can do at home. At the very, VERY least. I won’t— I won’t be deterred. Perhaps I could appeal again to Mark. He might listen to reason.

September 1935

Here it is, my last shot. Come on. ‘Dear Miss Skeffington, I’m not sure what you mean by being “ready and able” to fight. You’re five foot nothing, and a hundred and ten pounds soaking wet. How could you ever hold your own against a German brute? Think about holding down the fort instead. Think of the good you can do with a victory garden and a can drive. I’m sure a nice girl like you could certainly help out at the…women’s club bake sales downtown…’ Why won’t anyone give me a goddamn chance?

September 1935

I haven’t really been in a good mood since this morning. I got a letter at breakfast, but I didn’t have time to read it or even see who it was from since my schedule for the whole morning was filled. I left it in my dresser drawer to read later, and didn’t think much of it. It was midday by the time I got back. I’ve tried to lose myself in my art, but I’m not feeling it. Maybe it’s because Mother and I argued this morning? Probably not. We’ve clashed before. I’ve known for a long time we value different things. I just couldn’t stand Mother’s preaching attitude so I yelled back at her. I know I shouldn’t have done that but I’m so frustrated. She said that I’m not trying hard enough. What does that mean? I pressed her to keep talking, but she wouldn’t tell me anything after that. Is it because the Orwood girls teased me? I doubt it. They don’t know me. They’re just taking their issues out on someone. As awful as this morning was, this afternoon is looking up! Jim has written to me, and he’s coming to New York - more specifically, to Charles Street! Thanks to me, he heard about Mother’s advertisement for a new chauffeur that was put in the paper. Also thanks to me, the position still hasn’t been filled. Fingers crossed neither of us fall at the last hurdle and Jim gets the job!

Miss Skeffington,

It seems my luck has finally turned around. I received a phone call from the Silver Star Line, and it turns out I won a trip…to New York. I’ll be boarding the flagship Silver Star next week, and will soon be crossing the ocean to come see you. Or rather, your mother for a job interview. Hang tight, I’ll be on my way in no time. I can’t wait to see the look on your face when you see me!

Your friend,

Jim Masters

“Mr. Masters calling on Mrs. Skeffington. He’s here for an interview.”

“Oh, for the chauffeur position. Of course. Won’t you come in, Mr. Masters?”

“Thank you, I will. Hello, Mrs. Skeffington.”

“Hello. Let Clinton take your coat.”

“Thank you.”

“Let’s have some tea. How many lumps?”

“Uh…two, please.”

“Well, Mr. Masters, now do tell me all about yourself. Of course, I know all about your school and how you ran away to join the army. But before that, what?”

“Well, I used to live in San Francisco with my parents—”

“San Franscisco? My cousin, George, lives around there. I went to California when I stayed with him, you know.”

“Really? When?”

“During my pregnancy. Of course, at the time, I didn’t know it would be twin girls.” The mere mention of it brought forth a memory to the forefront of Fanny’s mind. A memory of Job. She tried to think of something or someone else but, once it began to play out, she couldn’t stop it.

~

“You’re laughing at me again. I suppose I’m just as fond of children as anybody else. Well, it’s just that... It’s just that babies grow up, and everybody expects you to grow up with them.”

“You’re not afraid of growing old, are you, Fanny?”

“Yes, I am.”

“Well, babies stay young for quite a long time.”

“Other people’s babies, never your own. Do I look puffy yet?”

“You look beautiful, Fanny.”

“I don’t know why. My face is all tear-stained.”

“Just enough to be becoming.”

“Well, I wanted to keep on crying, but I didn’t have the strength. You see, the sedative the doctor gave me made me very drowsy. Job, George is going to California in a week. I want to go with him and have my baby there.”

“You don’t want to have your baby in this house?”

“No.”

“But, Fanny, you love this house so much. Why, when we were married, you made me give up my home and live here.”

“Of course I love this house, but it’s too close to my friends. Soon, I’ll be all swollen and puffy and ugly. I don’t want anybody to see me like that. I couldn’t bear it. I won’t have them see me all swollen and ugly.”

“You’ll never be ugly, Fanny. And I don’t care how swollen you look. Fanny, a woman is beautiful when she’s loved. And only then.”

“Nonsense. A woman is beautiful if she has eight hours' sleep and goes to the beauty parlor every day. And bone structure has a lot to do with it too.”

“But I’m so busy in New York, and California is a six-day train trip. I won’t be able to see you very often.”

“I’ll write you every week, Job.”

“Fanny, that’s not the point. I want to be near you.”

“I’m so sleepy.”

“All right, Fanny. You can go to California if you want to. Fanny, aren’t you really happy about having...?”

~

Wanting to dispel the visions of Job and his sad, brown puppy dog eyes from both her mind and her sight, she quickly changed the subject back to what it was before. “Did you and your parents get on?”

“Yes, we got on very well. I’m an only child and, after my father died, I started to work for my mother as a sort of companion. Oh! And what a nervous, fidgety soul she was, too. Well, anyway, my mother had rheumatism, and the doctor thought, baths. Oh-ho, not that she hadn’t got baths. She had a very nice one in her house. Did you go to the baths while you were in California, Mrs. Skeffington? I mean, for your rheumatism.”

“I haven’t got rheumatism.”

“Oh, neither have I, but, you see, I figured baths wouldn't do me any harm, that is to say, while I was there. But I’ve always wanted to go to Europe. Not for the baths, of course, not at all, but for my writing. It's so good for writers. You see, my mother— Oh, but you don’t know my mother. What were you going to say, Mrs. Skeffington?”

“I wasn’t going to say anything. And I’m not Mrs. Skeffington. Not really. My husband and I divorced years ago, but I still go by his name.”

“I see. Well, Mrs. Skeffington… How are you getting along without him?”

“Oh, fine, fine, once I got used to it.”

“And your daughters?”

“You know, my daughters are... Well, they’re all right.”

“But they could be better?”

Around thirty or so minutes later, Jim emerged from your father’s office. You had been loitering outside, pretending to keep busy with drawing in your sketchbook so the servants wouldn’t question or bother you.

“How did it go? What did she say?”

“Your mother asked if I would like to be the chauffeur. She said your last driver wants to spend more time with his grandchildren, and is planning to retire. I have by the end of this week to decide.”

“And?”

“It’s a good opportunity. I’d get a raise in salary and I’d get to travel around the country. I think I’ll say yes.”

November 1935

It’s been almost two months since Jim first began driving for us. Instead of getting a taxi, Jim drives me. I know how to drive, I have my license, but this is one of the few times we can be together. Though we planned this scheme together, and I recommended him for the job under false pretenses so Mother would be none the wiser, it still feels strange that he’s the chauffeur and is technically below me. Social status serves as an invisible barrier between us when we’re in the company of others. As he’s driving, we talk freely as we always do whenever we’re alone together. I’ve been opening up more to him, telling him about the struggles I’ve been faced with, my rocky relationship with Mother, how I really dislike the confines and limitations of high New York society. I expressed that, despite having a successful art career, I felt empty and tired. Jim said that he wished he could do more to comfort me, since I’m going through so much right now. Sometimes, he will give me some suggestions when I ask what I should do. Other times, I just want someone to listen to me. Mostly, I am just happy to be with him. If only we could confess to everyone how much respect we have for each other, how much we admire each other. We’ve confessed to each other every opportunity we get, in different ways. I wish we didn’t have to hide, but keeping our friendship in secret will have to be enough for now.

“Hey, look, who’s taking you to dinner tonight?”

“Jeremy Clarkson.”

“Well, couldn'’t you speak to him?”

“I guess I could.”

“And who’s driving you to town tomorrow?”

“Matthew Jones.”

“Well, couldn’t I speak to him?”

“I don’t see why not.”

“And who’s taking you to dinner tomorrow night?”

“Brenda Jenkins. But nobody has to speak to her. We don’t like each other, so she probably won’t want me there, either. She was probably pressured into sending me an invite.”

“In that case, would you like to have dinner with me?”

“Oh, I’d be delighted.”

“Shall we go to the Waldorf?”

“Not the Waldorf. That’s where I’m not having lunch with Brenda Jenkins and her friends.”

November 1935

I told Mother and Uncle George that I was going to a double feature with Ann Lemp and that I wouldn’t be home till the morning. That’s only the half-truth. I did go to a double feature, but it wasn’t with Ann. Only Fanny knows who I was with. Afterwards, Jim and I crashed at a nearby motel. There was only one bed to sleep on, so we shared it. We kept our clothes on, only taking off our shoes and jackets so we’d be comfortable. He slept on top of the covers while I laid under them. The lights went out... I was turned toward him... My eyes started to adjust, and then I could see he was looking at me, too. In the dark, he smiled. My heart was beating so fast. I rolled over, I felt so... I don’t know, nervous? After a minute he put his arm around me and turned me back to face him, and he was so close, and whispered in my ear, “I really do love you, you know. In a way I thought I’d never love again.” I just nodded my head and I really hope he could tell. I really hope...that he meant what I think he did.

“Well, well, well, look what the cat dragged in.”

“Oh, Fanny! It’s only you. You startled me.”

“How was the double feature?”

“It was good, though I don’t remember most of either film, to be honest. We got distracted.”

“It’s past lunch time. You must be starved.”

“What makes you think I didn’t have any dinner or breakfast?”

“Well, you were out with Jim Masters. If you got potato chips, you were lucky. I saved you some leftovers. Turkey leg’s in the kitchen. If you’re hungry.”

“It’s beautiful. Can’t be Manby’s work. It’s too neatly arranged.”

“Manby did the cooking. I did the assembly.”

“Thanks. Mother very much worried?”

“No. I told her you’d be a little late because you had gone to Selena’s to do some shopping this morning. You called while she was out, and since it’s Sunday and the servants’ day off, I answered the phone.”

“I don’t understand. Why did you lie?”

“Mostly from force of habit. Although I did rather gather that Mother wouldn’t be too pleased if she knew that you were out with Jim.”

“I see. I can understand Mother’s attitude, though. You can’t grow very fond of a daughter you’re always trying to keep on a leash and out of trouble. She keeps herself separated from the servants, always strictly professional and impersonal. She expects the same of us. She doesn’t know Jim the way I do.”

“Of course not.”

“You saved this food for me, and you lied for me, and you like Jim. You sure nobody’s home?”

“Nobody.”

November 1935

A week passed since my movie night with Jim. Fanny and I were looking out my second story bedroom window at Jim, who was out on the driveway, working on one of the cars.

“There he is. Fanny, stand back a little. Well, I'm glad he's a man. Certainly would like to know a man for a change and have a little fun.”

“Don’t let Mother hear you say such things.”

“Hello! Good afternoon!” Jim called up to you, raising his arm to wave at you.

“That dreadful man, he waved back.”

“You’re every bit as bad as he is.”

“I know. I wonder how I could get to know him. I wish we had a dog or a cat, and it would get lost and he’d bring it back, then we’d get to talking...”

“I don’t think that’s very romantic.”

“Who said anything about romance? I’m going to go down. I’m going to talk to him.”

“And if Janie Clarkson or one of her friends catches you? What will they think? Stopping to talk with the chauffeur.”

“I don’t care. Anyway, Janie and her friends weren’t very friendly to Jim. They wouldn’t even say ‘good afternoon’ or ‘hello’ to him whenever they saw him when they passed by our house.”

When I came out the front door and walked down the driveway to meet Jim, he was wiping his hands off with a cloth.

“Miss Skeffington. Why do you sit at your window looking out at me when I’m working on the driveway or in the garage?”

“It’s my family’s property, and I can look out as much as I like.”

“I saw you. I waved to you, but you didn’t wave back.”

“I was embarrassed you caught me. It's rude of me, I know, but you always seem to be having such a good time. When I watch you work on cars, it’s like looking at a picture and I want to commit it to memory. I wish you could come inside. Then you’d be a part of the picture. But Mother mightn’t approve. She doesn’t believe Fanny or I should be too friendly or overly familiar with the staff. How muscular your arms are when you roll up your sleeves, your skin glistening with sweat from the summer sun as you comb your hair back from your forehead with your fingers while you pop the hood of a car to tinker with an engine…”

“Miss Skeffington.”

“Oh no. Did I say that last part out loud?”

“You did.”

“I’m sorry. My mouth has run away with me again.”

“No, Miss Skeffington. It’s your mouth that has me hypnotized.”

“Watching you just reminds me of when we were in Europe. You asked me to see a wrestling match with you and stay over at your friend's place in the city after. That was a lie-to-Mom-and-Dad situation. But it was sooooo worth it. The men in the arena were just so big and muscular and sweaty, and everybody was moving together like one intricate dance. Between two matches you leaned over and said, ‘how do you like your first wrestling match?’ I was so happy I felt tears starting in my eyes, and then you up and hugged me. I think you could tell I was crying.”

“I could, but I didn’t want to say anything and ruin the moment.”

“Sometimes you just have to lie to Mom and Dad, just like we did last week. You know, I’m going to tell you something. Everybody in this neighborhood likes you, except for Mother and her followers.”

“Isn’t your mother and her followers practically everybody?”

“Exactly my point. In fact, there’s a popular front against you. Mother formed it last night, and it’s made up of her circle of so-called friends, lovers, and their envious wives.”

“Guess I deserve it.”

“I don’t know about that. Maybe you do and maybe you don’t. But I don’t feel the way Mother does. If you ask me, I think you’re all right.”

“Do you?”

“I’ve always had a lot of fun talking to you. You know, you’re not such an ogre after all, no matter what they say.”

“In fact, I have a couple good qualities if you look deep.”

“You certainly do. You’re very understanding and you like Fanny and Dad. That definitely shows a lot of character. I wouldn’t be surprised if we became more than good friends after a while.”

I’ve felt like a shook-up can of nerves ever since. I hope we have a chance to talk again before I explode.

December 1935

Mother wasn’t home, something about doing some Christmas shopping, so Jim made an excuse and came into the house today. He came into my room and said he had a note for me from Fanny, just something to get past Soames. I told Soames I could manage from there and dismissed him, and then Jim and I were left alone. But everything was...different. He was sitting at my desk chair while I sat on my bed. He wouldn't look at me. Finally I asked him what was going on. He said he felt like he’d done something wrong that night in the city, that I must think... But I said no, there was nothing wrong. I just wanted to say... But I couldn’t find the words. I felt like I was going to cry, but I wasn't sad. He got up and sat next to me on the window seat. I looked at him. “Jim... do you...think...you could ever...” And that’s when he kissed me. A kiss should be the simplest thing in the world. Not this gentle stirring, like wind through the underside of leaves, inexorable as the glacier grinding behind us. So hot and yet it doesn’t scorch. No, with every breath, with every touch, his kiss carves.

January 1936

It’s different now. I mean, we still see each other all the time like before. But now when no one else is around...well, you know. So you COULD say we’re dating. But it’s secret. Secret dating? I don’t know. I mean I guess that’s the real difference: Now, when we get off the phone, or go home for the night...or it’s just quiet and we’re alone...we say, “I love you.”

March 1936

Mother’s birthday is next Thursday, the 12th. Instead of celebrating on the day, she’s hosting a birthday ball at the house this Saturday. Probably to ensure she’ll have the largest turnout possible. She’s invited everyone, even me and Fanny. Weird that she sent for us so she could tell us this HERSELF instead of having Soames, Clinton, or Manby do it for her. Even weirder is that she wants either of us there. Surely she wouldn’t want us, reminders of Father, to be there? I was expecting her to ask us to go to the theater again or make some other excuse to get us out of the house so that we wouldn’t take any attention off of her. Heaven forbid one of us talks to a man for more than five minutes while she’s in the same room. We’re her daughters, yet we’re seen as competition to her. Normally whenever she sent for us, she recited the same script along the lines of, “I wanted to explain to you and your sister, Fanny... l’m giving a dinner party on Thursday for some very old friends of mine. And I’m sure it would be a frightful bore for both of you. You understand? Why don’t the two of you go to the theater? I hear there are some very good plays now.” and we’d take that as our cue to make ourselves scarce. We’d always say, “Oh, yes. Yes, of course we do. All right, Mother.” After all, I reasoned that Mother, who considered herself a very sensible woman, was soon going to have a fiftieth birthday, and on reaching so conspicuous, so sobering landmark in one's life, what more natural than to hark back and rummage, and what more inevitable, directly one rummaged, than to come across Father? Perhaps it was the highly unpleasant birthday looming so close that set her off in these serious directions.

“Good morning, Mother.”

“Good morning, girls. Come in. What sweet dresses.”

“Oh, thank you.”

“You don’t think, perhaps, they’re a little old for you?”

“You sent for us, Mother?”

“Oh, yes. Yes, I wanted to explain to you, girls...l’m giving a birthday ball on Saturday for myself and some very close friends of mine. And I’d like you and your sister to attend.”

“Would you really, Mother?”

“Yes, very much. A lot of my friends have sons and daughters that are around your age. It’d do you both some good to mingle a little, make friends. Do you understand?”

“Yes, of course we do.”

“Mother, do I really have to go? There’ll be all those people,” you asked, your voice laced with anxiety.

“Oh, it would hurt my feelings if you stay in your room or go elsewhere. Besides, dear, you must learn not to be afraid of people.”

March 1936

St. Mary’s is an old school and very well respected. Though Mother didn’t care for it. She wouldn’t, even if it was where Georgia O’Keeffe herself learned to paint. I teach nice young ladies to paint. What could be more respectable? I only kept it a secret because I knew she’d be angry and/or disappointed. She found out about it the same afternoon as Uncle George, so she thought my contempt for them both was at least consistent. But I don’t have contempt for anyone. “George, why didn’t you stop her?” she asked, to which he asked in return, “Me? What could I have done?” It doesn’t seem to bother Uncle George that I teach at the school, or Fanny. Mother tried to tell me that the people in charge at the school feel sorry for me, that’s all. She’s wrong. Not everyone is as cruel and mean-spirited as her. I said as much. “Is it cruel to mind it when you stamp on our name and drag it in the mud? Now, get out of my way!” she huffed, and stormed off. Neither I nor Uncle George made a move to stop her. She just needed time to cool off and get used to the idea. I suppose in any other circumstance, I’d have to drop it. But I won’t. I’ve given my word to the headmistress, and I’m not going to break it. Things may be uncomfortable, but so what? I won’t be put in a cage! Soames came in and asked if everything was all right. He heard our shouting, which is unusual in this house. It... It was unusual, yes. But every now and then, I wonder if it isn’t good to shout a little and let off steam.

“Masters, when you’ve finished unloading, run down to the school and remind my daughter that we expect her here for dinner. And tell her I mean it. Really. She’s working herself to death like a canary in a coal mine.”

“I think she enjoys it though.”

Fanny turned around to put him in his place. “Please tell her to come home in time to change.”

Jim nodded grimly and returned to the car.

“I can’t possibly come! Really, Mother is incorrigible!”

“It’s not poor Masters’ fault.”

“But what is the point of Mother’s soirees? What are they for?”

“Well, I’m going out for dinner tonight and I’m glad. Is that wrong?”

The sudden act of courtesy was enough to leave me frozen. But to think of it, a self-conscious beauty queen like her would love showing off how ‘tolerant' she could be. I learned that very often the most intolerant and narrow-minded people are the ones who congratulate themselves on their tolerance and open-mindedness. I’d prefer celebrating quietly with her in her room, but since the party is practically being held for her and she is my mother, I thought it would be somewhat rude of me to not be there. Maybe I can use this birthday party as an opportunity to sneak away out the back door and spend more time with Jim. He has been nothing but sweet on me since Mother hired him, so the least I could do is show up, make my rounds of saying hello and exchanging pleasantries and engaging in idle chitchat with a few of the guests, then make my move. It’s not like anyone would miss me. I know Mother especially wouldn’t. Maybe…just maybe I could even piss Mother off if I manage to strike conversation with Jim. A Skeffington spending the entire evening with the chauffeur? Mother would be beside herself, fuming about how I mess up her ecosystem. No peer pressure, Miss Skeffington. Just clean drinks and hopefully some casual talk with Jim. What could possibly go wrong?

You finished your hair as Fanny entered.

“Mother said you were honoring us with your presence at dinner.”

“It’s easier there in the school. And I can always get changed back into my painting clothes if I need to. This stuck-up thing. Oh, dear. It shows.”

“I don’t know what you’re going to do.”

“I’ll blend it right in. I can do it with just a few strokes of the brush. Splendid. I’ll stick to every chair in the place.”

“I thought if I pinned this bow over it—”

“A bow? There?”

“I’m sorry, darling, but you’ll just have to sit on it.”

“Sit all evening?”

“You could stand if you’d keep your back to the wall.”

“You’d better hurry, girls,” your mother said as she came in to check on you. “Guests are arriving.”

“Oh... Oh, how I hate to be elegant.”

“Oh, how I detest rude, unladylike girls.”

“And I hate affected, niminy-piminy chits.”

“Oh, the dress is lovely, darling. Just lovely.”

“Oh, thank you, Mother, for letting me wear your velvet and pearls.”

“They’re old, but you’re young and very pretty.”

“Oh, thank you, Mother. Well, my shoes are too tight, and I have nineteen hairpins sticking in my hair and a curling iron burn mark on the back of my dress, and I feel dreadful.”

“Where are your gloves?”

“Here. They’re stained with lemonade. I don’t think I’d better wear them.”

“Why, you must. You can tell a lady by her gloves.”

“Not this lady.”

“A lady barehanded? You have to have gloves. You can’t dance without them.”

“Ha! I can’t dance and keep a back to the wall anyway. I’ll crumple them up in my hand.”

“At least wear one of my nice ones and carry one of your ruined ones.”

“Oh, all right.”

“Don’t stretch it. Your hands are bigger than mine. Don’t eat too much. Wait until you’re asked. Don’t be afraid, darling. Have you and Fanny got clean handkerchiefs? And don’t put your hands behind your back or stare. Don’t stride about or swear. Don’t use slang words, darling. Vulgarity is no substitute for wit, and wit is very fashionable at the moment.”

“All right.”

“And please don’t talk about Europe all the time. And especially don’t mention Cascade. You’ll embarrass me and yourself.”

Though she didn’t bring it up by name, I could tell she was referring to that infamous dinner party, when my unpleasant characteristics became especially evident, where I, unknowingly to myself, embarrassed her by singing and playing badly. I was only a child then, and was regarded as the plain-looking sister. Though much more sensible than my mother, I was still considered to be very silly by her peers. Despite the fact that my father was studious and once described as the most accomplished in the neighborhood, I lacked genius and taste.

“And stop whistling. It’s so boyish.”

“That’s why I do it.”

“I just want to make things easier for you.”

“For me or for you?”

“Don’t disappoint me, darling. Not now that you’re here.”

“Not to worry, Mother. I’ll be prim as a dish. Let’s be elegant or die!”

“Oh, so boyish.”

“Mother, you’re perfect.”

“Oh, thank you, darling. And you. Aren’t you the pretty one? Walk toward me, darling, that I may appraise you. Go on. Walk to me. Stand up straight. Turn around. Shh. Mm, yes. Oh, it’s quite as I expected,” she said. “You know, you’re very tall for your age.”

“Really? But, Mother, I’m nearly... Well, yes, perhaps I am.”

She placed her hand under your chin to cup your face. “You possess a woman's chin. Skin is a little dull. Have you not noticed? Observe her mouth, Fanny. And as for you, darling, now that you turn up your hair, you should realize you’re a young lady. My daughter...a woman. She’s beautiful, isn’t she? She’s going to be a stunning woman, don’t you think, Fanny?”

“Yes, she’s going to be.”

“I’m not! And if turning up my hair makes me one, I’ll wear it down or in two tails till I’m ninety. I won’t grow up and be Miss Skeffington. I won’t wear long gowns and look like a China aster. Oh, I’ll never get over my disappointment of not being a boy, and look at me! I’m dying to go and fight like Father did in the last war. Fine soldier I’d make. And here I am sitting and knitting like a poky old woman.”

“Knitting. Bless me. Poor you. Almost a lady. You must spend less time with the neighbor boys, and more time with me.”

You’ll never guess who I bumped into as I left the party that night. Oh, Fanny, it was meant to be. It was so perfect. There I was, weeping on the terrace, and there he was, Jim. He waited outside so he could give me some time without going too far.

Jim heard heels clicking on the garage floor and glanced up from the car engine. He did a double take as he saw you in your evening gown. You tilted your head shyly, waiting for him to say something. It was the first time you wore a dress since you were a baby.

“Don’t you dare laugh.”

“You look very fine.”

“Everything I own is trousers and shorts. Too boyish, according to Mother. Usually if I have to wear a dress or a skirt, Fanny lends me something. Mother lent me this dress from her season before the previous war. It’s very old, but she wants me to try to wear it out. If you ask me, it’s already there. Yards of fabric and I still feel naked.”

Jim continued to check you out.

“Where have you been all day?”

“Nowhere. I’ve just been busy.”

“I thought you were avoiding me.”

Jim walked purposefully forward. “Of course not.”

“But you haven’t come up with an answer yet, have you?”

Jim ducked his head and stared at the floor. “Not yet, I’m afraid. I know you want to see the world and play your part in its troubles, and I respect that, but… I have a lot weighing on my mind, and I need to sort it out before I can make a decision about us just yet. It won’t be long until I give you an answer. So, will you wait?”

“I’d wait forever.”

“I’m not asking for forever. Just a few more weeks. Darling, there’s something you should kn—”

“I’ve been thinking about us lately. Of course, I don’t want Mother to know that I deserted her so quickly so, if anybody’s around, you don’t mind if I act sort of cool and distant? To keep up appearances. Do you know how it is?”

“I certainly do. I understand perfectly.”

“Why are you smiling? I thought you’d be angry.”

“Because that’s the first time you’ve ever spoken about ‘us’.” Jim smiled with a sigh of relief and leaned forward to kiss you, but you held back.