#archeological discoveries

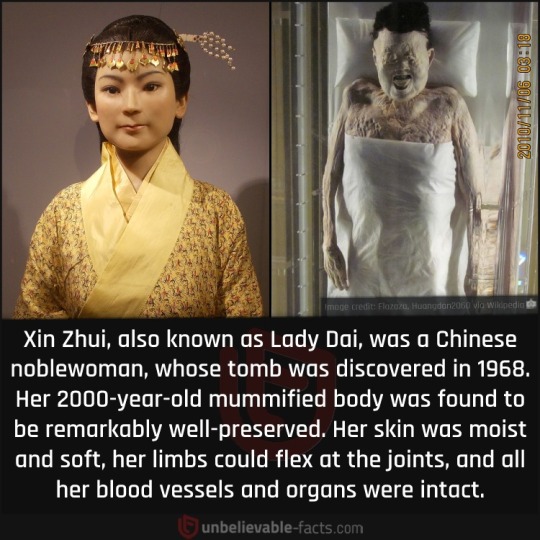

Photo

Discovered in a mine in Alberta, Canada in 2011, a fossil of a nodosaur dinosaur is one of the most well-preserved fossils of its kind, down to its skin, scales and even the contents of its stomach. These heavily-armored herbivores walked the Earth between the Late Jurassic and Late Cretaceous periods, with this particular specimen dating back 110 million years.

Considered one of the major archeological finds from the last decade, the nodosaur is currently on display at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta, Canada

#nodosaur#dinosaurs#dinosaur fossil#major archaeological find#dinosaur fossils#Royal Tyrrell Museum dinosaur finds#dinosaur museum in Alberta#Canada#archeology#archeological discoveries#mummified dinosaur

290 notes

·

View notes

Text

Temple Mount Secret Debris: An Archaeological Goldmine [Unseen Footage]

youtube

Temple Mount has a few mysterious that most people don't know about. The mountain of "trash" that is behind the Dome of the Rock is actually a debris from the illegal excavation at Temple Mount in 1999. This Debris holds 1st and 2nd temple period artifacts. In this video, Rhoda and I, together with our friends Jeremy and Jocelyn go on an unscripted expedition to the Temple Mount. Little did we know, today happens to be the Jerusalem day. A day which is usually known for civil unrest in this area. But this did not prevent us from seeing the debris, and also, accessing a completely new spot - the wall on top of the Eastern Gate. Join us in another adventure of the Unscripted series.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#Archeological discoveries#Drowned city#Enigma#Lost city#Myth#Rama empire#Rama the lost empire#amazing discoveries#archaeological discoveries#archaeological finds#atlantis#atlantis empire#atlantis the lost empire#atlantis: the lost empire#discoveries#greatest archeological discoveries#incredible discoveries#mysterious discoveries#mysterious finds#recent discoveries#strange discoveries#the sinking city#unexplained discoveries#Rama Empire Suddenly Disappeared#Youtube

0 notes

Photo

Italy Hails 'Exceptional' Discovery of Ancient Bronze Statues in Tuscany

Archaeologists in Italy have uncovered more than two dozen beautifully preserved bronze statues dating back to ancient Roman times in thermal baths in Tuscany, in what experts are hailing as a sensational find.

The statues were discovered in San Casciano dei Bagni, a hilltop town in the Siena province, about 160 kilometres (100 miles) north of Rome, where archaeologists have been exploring the muddy ruins of an ancient bathhouse since 2019.

"It is a very significant, exceptional finding," Jacopo Tabolli, an assistant professor from the University for Foreigners in Siena who coordinates the dig, said on Tuesday.

Massimo Osanna, a top culture ministry official, called it one of the most remarkable discoveries "in the history of the ancient Mediterranean" and the most important since the Riace Bronzes, a giant pair of ancient Greek warriors, were pulled from the sea off the toe of Italy in 1972.

Tabolli said the statues, depicting Hygieia, Apollo and other Greco-Roman divinities, used to adorn a sanctuary before they were immersed in thermal waters, in a sort of ritual, "probably around the 1st century AD".

"You give to the water because you hope that the water gives something back to you," he said of the ritual.

TIME OF CONFLICT

Most of the statues date to between the 2nd century BC and the 1st century AD, a period of "great transformation in ancient Tuscany" as it switched from Etruscan to Roman rule, the Culture Ministry said in a statement.

It was an "era of great conflicts" and "cultural osmosis", in which the Great Bath sanctuary of San Casciano represented a "unique multicultural and multilingual haven of peace, surrounded by political instability and war," the ministry said.

The statues were covered by almost 6,000 bronze, silver and gold coins, and San Casciano's hot muddy waters helped to preserve them "almost like as on the day they were immersed," Tabolli said.

The archaeologist said his team had recovered 24 large statues, plus several smaller statuettes, and noted that it was unusual for them to be made out of bronze, rather than terracotta.

Tabolli said this suggested they came from what he called an elite settlement, where archaeologists also found "wonderful inscriptions in Etruscan and Latin", mentioning the names of powerful local families, the ministry statement added.

According to Culture Minister Gennaro Sangiuliano, the "exceptional discovery ... confirms once again that Italy is a country of immense and unique treasures".

The ministry said the statues have been taken to a restoration laboratory in nearby Grosseto, but will eventually be put on display in a new museum in San Casciano.

#Italy Hails 'Exceptional' Discovery of Ancient Bronze Statues in Tuscany#bronze#roman bronze statues#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient tuscany#ancient bath house#roman history#roman empire

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Nearly three decades ago, a team of archaeologists were carrying out an expedition inside a large cave system on Mount Owen in New Zealand when they stumbled across a frightening and unusual object.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 13 full and fragmentary projectile points, razor sharp and ranging from about half an inch to 2 inches long, are from roughly 15,700 years ago Which is 3,000 years older than the Clovis fluted points found throughout North America.

These slender projectile points are characterized by two distinct ends, one sharpened and one stemmed, as well as a symmetrical beveled shape if looked at head-on. They were likely attached to darts, rather than arrows or spears.

#history#archeology#archeologicalsite#discovery#americas#native american#paleolithic#migration#projectal points

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

if his name id "chill" chuck thej why is he mad when we throw ice magic at him

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

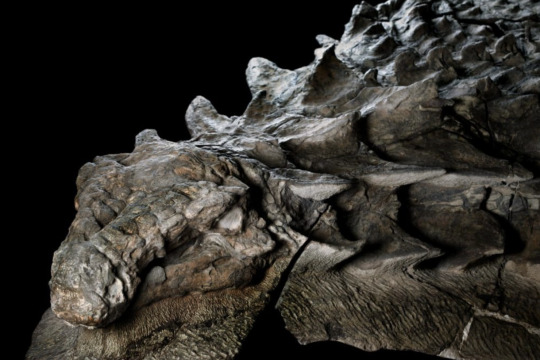

It’s not until she hears Sissel’s knees hit the floor that Efri is jolted back into her body.

She blinks, whipping her head around. Sissel is kneeling, bracing a palm on the ancient stone pavement, at the barrier – no, the barrier’s gone, it’s just Sissel on the floor. She lifts her head and meets Efri’s eyes; her hair is wispy and wild, the little plaits meant to keep it neat come loose and tumbling, her eyes wide. The barrier's gone, but still, her pale face is lit up blue.

“Are you okay?” she asks. She doesn’t speak loudly, but it echoes in the great stone chamber.

Nine, Efri doesn’t know.

She blinks again, looks down at her hands, clinging to the metal stick so fiercely that her joints ache. (Her own stick, her nice wooden one, is still on the floor somewhere, where it slipped out of her grasp when she hit the wall.) The lumpy heavy end of it, the clobbering end, is still resting on –

Not on. It’s in the thing’s head, fitted neatly in the opening of its dented helmet, the horns spiralling over the floor. There’s a tooth, perfectly preserved, by Efri’s foot.

One by one, she unwraps her gloved fingers from the handle of the metal stick, letting it drop to the floor with a clang so loud it makes her wince. Kazari is nosing at her side. (When did they let go of it? When did they get so close? She must have missed that. She feels out of the loop. Her heart is juddering like fish on a line, battering like some frightened trapped thing at her ribcage, and her breath is coming fast and heavy.) Absentmindedly bringing up a hand to press over her sore shoulder, she says, “’M fine. Not too – barely touched me.”

Kazari turns and spits on the floor. Efri blinks. She does it again, tongue lolling out of her mouth, face very disgruntled – and oh, Efri gets it. She does not glance down at the thing at her feet; she doesn’t need to, she knows what its arm looks like, chewed almost to pieces even through its banded armour. (If she hadn’t been so busy being scared of it, that sight might have made her a bit scared of Kazari. But not now, when they’re trying to hack and spit the taste of dead man arm out of their mouth.)

Efri unclips her canteen from her belt and holds it out. “Here,” she says. Her voice is rough. Her heart is racing too much to let constructing sentences be easy. “Not much, but –”

Kazari stands still while Efri tips half of the remaining water onto her tongue, and then Efri watches her swilling it around in her mouth, trying to bathe all of her teeth in it, before she spits it again on the floor at the dead thing’s feet.

The water is still clear. That’s something, at least; the dead man was too old to still have blood in him. Or maybe he was embalmed, drained of it hundreds of years ago, thousands.

“Are you okay?” Efri asks Kazari when they’re done, because they were the one doing most of the fighting, who was closest. They tip their head, shift their weight – wince when they put weight on one foot. Their lips peel back from their teeth. Their clothes on that side are singed.

Efri points it out. “Your robe,” she says, which makes it sound much fancier than it is. She’s too tired to think of a better word. She rubs a hand over her face, pushing the hair back over her forehead, says, “I’ll reinforce it for you when we get out.”

Kazari noses at Efri’s shoulder – the shredded fabric of her dress, the fraying edges stained with blood. Efri says, “I know. I’ll have to sew that up too.” Over her shoulder, she calls, “Kazari’s leg’s hurt, I think.”

“There’s blood on you,” Sissel replies. She peels her hand off the floor and leans back on her heels.

Efri touches her shoulder again. “’S fine,” she says. “Just a scrape. The blood’s drying already.”

It’s really sore, actually – the flesh abraded and tender, an ache sinking deep into the muscle – but it’s normal sore, the kind of sore you really should be after being thrown into a wall. It doesn’t feel sprained or dislocated or anything like that. Just like it will be bruised a whole rainbow of colours come tomorrow.

Kazari noses at it again. She leans too far forward and falters on her maybe-hurt leg – rights herself, wincing, and rolls her shoulder. It gleams, just for a moment, and she nearly stumbles again. Efri puts out a hand to steady her. (It doesn’t really accomplish anything – Efri’s strong, but she’s not that strong – but it’s the principle of it.) “What was that spell?”

“Pain relief,” Sissel says from behind her. “I think. Doesn’t actually fix anything, but.”

“You’ll be okay ‘til we find someone?” Efri asks, and Kazari nods. She presses a hand against their shoulder and nods back.

They both turn to look at Sissel, then, who’s just kneeling on the floor, sitting on her heels.

“You all right?” Efri asks her.

“All right,” Sissel confirms. She doesn’t look at them. “Didn’t even come near me.”

She’s staring.

Efri crosses the floor to stand with her. (She needs to lean on Kazari – her legs are too wobbly, and she doesn’t want to touch the dead thing’s stick, doesn’t want to look for her own. Kazari limps a little on their sore front leg.) There’s a moment of total, humming silence – all of them still and staring, necks craned back, looking up at the thing.

Whatever it is.

It’s a ball. Big and blue and shimmering, it floats above a wide crystalline dish set into the floor, spinning on an axis. Just spinning and spinning and spinning, endless motion. Its smooth surface is cut through with dark wavering lines, etched with lettering, and it doesn’t quite glow but it doesn’t not glow, either, the light moving across it silkily, like clouds in a blue sky. It looks like something that should be humming – a low pitch in their ears, an eerie shiver dancing over their skin – but it’s silent. Inert, maybe, but for the spinning.

“What is it?” Efri asks. Her voice cracks as she speaks. She looks down at Sissel’s face, staring as though mesmerised, illuminated by the room’s dim lighting – the fires that should not still be burning down here, the luminous not-glow of the ball.

Sissel says, “I don’t know. Something important.”

Hovering above the dish, it spins, and spins, and spins.

“Is it what the ghost was talking about?” Efri asks. She tilts her head and squints at it. It doesn’t – well, it looks strange and unearthly and powerful, but it isn’t doing anything. And it hadn’t been clear what the ghost was talking about, exactly, according to Sissel, just that it was something important – but what else could it be?

Sissel, still watching it, shrugs. “I don’t know,” she says. “I think so.”

Efri watches it with her, brushing a bit more hair out of her face. It’s sticking to her sweaty forehead. She feels a drip of not-dry blood running down her arm under her sleeve.

Kazari is staring at it too – just as confounded as the rest of them. Efri sees the light in their irises shifting as the ball spins.

They’re not learning anything from staring, the ball staying strange and mysterious as ever, so Efri raps her knuckles against her sternum to steady her breathing (it’s slowed a bit – not normal, but closer to it) and climbs up onto the stone rimming of the dish. Kazari, behind her, lows in consternation; Sissel catches her breath, a noise like a creaking door. “Careful,” she says.

“Promise,” Efri replies, and places her feet very, very carefully on the glassy blue flooring. Nothing happens. She doesn’t step on the dark curved lines as she treads toward the ball in the centre, slow and wary as if she were approaching a skittish animal. Nothing happens.

She reaches out, and, with just the tips of her fingers, she grazes the ball’s surface.

Nothing happens.

It’s cool to the touch, and smooth, like polished metal or not-frozen ice or delicate glasswork. It continues to spin gently under her fingers, warming her glove with friction, no smudges left on its clouded face.

It really feels like there should at least be a tingle running up her arm, a strange and unfamiliar current, a spark. But it’s just Efri, standing with an arm outstretched, pressing her hand to a ball.

“It’s not doing anything,” she reports, and Sissel clambers up onto the dish with her, fitting her palm to its gently hovering underside. Kazari balks, begins pacing agitatedly. Efri frowns. “Why isn’t it doing anything? Shouldn’t it be doing something?”

“It’s important,” Sissel says definitively. There’s ancient dust on her fingers, but none of it seems to transfer. “It’s something really special, I think.”

Efri shifts restlessly. She shifts her grip and tries to grab onto the dark ridged curves ringing its surface, but they slip easily away from her grasp as though her touch was no barrier at all. “But what does it do?”

Sissel shrugs.

Behind them, Kazari lows.

Efri drops her hand and grabs Sissel’s wrist. “C’mon,” she says, and when Sissel frowns at her, “We’re not going to learn anything about it this way. We have to look for clues!”

Kazari makes a more impatient noise. (Efri thinks she found a clue.)

Sissel gives the ball one last searching look and lets Efri tug her away, off the weird blue dish and down to where Kazari stands on the stone floor, at the head of the table where the dead man sat. Efri sniffs loudly and tries not to think about it too much. The table is smooth polished stone, worn a little away with time; Efri trails a gloved finger over the edge and directs her attention to where Kazari points with their chin.

There’s something carved into the surface, the edges blunted and shapes softened by however many years it must have been since it was put there. Efri squints, trying to make it out. She has to stand right up on her tiptoes to get the right angle to see much of it in full.

“That’s not letters,” she says eventually, frowning. She’s pretty sure she knows her alphabet well enough by now to know that. “Is it magic?”

Sissel shakes her head. “I don’t know what it is. It’s not like magical writing I’ve ever seen.”

Efri looks at Kazari, who also shakes her head. “Maybe it’s a different sort of lettering,” she theorises. It must have been written a long time ago, if it’s from back when the city had people. Onmund’s been reading all about it for ages, and he’s told her a bit – Saarthal was the city of Atmorans, populated by proto-Nordic people. All complicated history stuff. But they weren’t quite the same as Nords today, he said, so it stands to reason they had different writing, too. They’re supposed to be uncovering and cataloguing artifacts (at the thought, Efri glances back at the hovering ball and swallows an inane bubble of laughter) so she suggests, “Maybe you can copy it and we can show it to someone. I’m sure there’ll be someone at the College what knows what it is.”

Sissel, also standing on her toes, nods dutifully. “What will you do?”

The chamber they’re in is cavernous, and about empty but for the ball in the dish, the altar and chair, the body on the ground. “I’ll check him,” she says, and points. “See if he has anything on him that’s special.”

Sissel follows her finger and grimaces.

She digs out her note-paper and her stick of char, and Efri assumes it’s clues time, but when she turns she feels a hand grip her elbow. She looks back over her tattered shoulder at Sissel’s face, her furrowed brow.

“Promise you’re really okay?” she says, voice anxious and solemn.

“Promise,” Efri says, twisting her arm to touch her friend’s hand. Sissel presses her lips together and lets go of her arm.

Kazari trails after Efri to look at the dead man.

First thing is the metal stick. It’s magic someway, Efri knows – he waved it and threw her into a wall, flung spells with it – but she’s not sure how. Doesn’t know enough about enchantments. Didn’t need to, to use it; when Kazari clamped down on his arm she just ripped it from his grasp and –

She doesn’t quite exactly remember, actually, except for the bitter tang of adrenaline in her mouth and nose, the horrible grunting and scuffling sounds, the heft of the stick in her hands. Impact, over and over and over, against something that had a little more give each time.

Efri scrubs a hand over her mouth and grips the handle of the stick. It takes effort to wrest it out of the thing’s face, caught as it is by the edges of the helmet, and when it’s finally yanked free it’s – actually not as bad as she might have expected. There’s no blood, and the corpse was so desiccated it already didn’t even really look like a person anymore, so it registers less as someone with horrible violence done to it and more as a really gross art piece. It’s not nice. She doesn’t like the twisted, gaping mouth, teeth embedded wrong-ways in its tissue and scattered like coins over the floor. And one of the eyes, which had glowed unearthly blue, is now a dull, rotten black, squished like a plum in its socket.

It's worse the more she looks. She sniffs and turns away.

“This is magic, right?” she asks Kazari, testing the weight of it in her hands, the cool surface of the metal, and they nod. “A good artifact?” she adds, and they nod again, emphatically. Efri sets the stick aside and kneels.

It wasn’t wearing any clothes, really – or if it was, they rotted away. She touches the rusted armour gingerly, tries to avoid brushing her gloves against the shrivelled skin at all. Whoever it was had expensive taste, it seems – there’s jewellery in a shockingly well-preserved beard, pendants around the neck, armbands. Efri asks Kazari if each thing is enchanted. No to the armbands, no to the beard-ring, and then, pressed against the wizened chest where the flesh contours to the ribs, she finds some kind of necklace, sharp-edged and thrumming. Kazari nods to that, and, face scrunched up like an old fruit, Efri reaches around the ancient neck to slip it off.

She tucks it into a belt pocket with the tripwire necklace they found at the weird wall.

“Done,” Sissel says. She folds her paper and slips it into her own pouch. Her footfalls on the echo-y stone floor as she approaches the body for the first time are almost silent. “Did you find anything?”

“Necklace,” Efri replies, watching Sissel’s face pinch at the sight of him. “And – stick.” She scoops up the metal stick and holds it out. “He did spells with it.”

Sissel looks at it warily. “Is he a draugr?” she asks, glancing back down at his mashed-up face.

“I mean,” Efri says, “he’s got to be, right?” She’s certainly never seen a draugr before, but what else could it be?

(Calling it a draugr makes her shiver, the set of her shoulders quaking. She’ll stick to dead man.)

Sissel shudders. She reaches out to grip the handle of the stick, and Efri’s not sure if she’s taking it or just trying to keep herself upright. “I can’t believe that happened,” she says. Her voice sounds, suddenly, fragile. “I can’t believe we’re alive.”

“Me neither,” Efri says. She presses the tip of the stick into the ground so Sissel can lean on it, stands a little unsteadily.

Kazari, with a hushed murmur, telegraphs something. Efri recognises the head incline of understanding – she’s familiar with that word, that idea – and, after a moment, the flickering ear of doubt.

“They’ll have to believe us,” she says with conviction, because she means it. “We’ll show them. They’ll see for themselves.”

Kazari presses their nose to her head.

Efri clasps her hands together. “We’ll go tell someone now,” she declares – though it’s easier said than done; they were lost in the ruins ages before they even found the crumbling wall, the halls, this horrible wonderful chamber. But they’ll get un-lost eventually. They’ll get out eventually. Surely. They have practice enough with walking. “But first – help me find my stick.”

#little girl has a kill count now!! more at 11#for context: I altered stuff leading up to the discovery of the eye#efri and sissel went off to play in the undiscovered halls of this ancient archeological dig site#on the grounds that efri has a great sense of navigation and they'll find their way back to the group no problem.#(efri has a great sense of navigation in the wilderness.)#(introduce her to a series of roads and buildings and she is lost in the sauce.)#their friends split up to look for them after they've been missing from a while (wandering around with great interest and no sense of place#(incredibly lost)#kazari happens upon them right as they've found a necklace at the end of a dead-end passageway that - when dutifully grabbed#for archeological research purposes - ended up triggering the wall to crumble or disappear or otherwise remove itself from the equation#and efri wasn't going to just. LEAVE that opening there.#come ONN kazari that's weird!! we can't just leave it!! what if it closes up and we never ever find it again and there's incredible secrets#that the college never finds! what if we never know what's through there!#we HAVE to know what's through there!#so on they go.#and so ensue the horrors#they pass a lot of dead bodies before the main all but those ones are all immobile#also sissel is the only one to receive the psijic projection warning. which she explains to the others as a ghost telling her secrets#which efri accepts bc this seems like the kind of place that would for sure have ghosts#and kazari goes sure that tracks this place is fucking creepy can we leave now (<- is also curious but HAS to put on a show of reluctance#because clearly no-one else is going to)#(permanent babysitter of kids with the worst self-preservation instincts imaginable)#(she is so strong. living every childcare worker's nightmare)#ANYWAY#:D#normal type stuff#posting because it matches the artwork I'm also posting! look at that thing!!!#fay writes#oc tag#efri

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cleaning out my phone

#christopher pike#star trek the original series#star trek aos#star trek discovery#remember the blue check thing?#i must have made this then#meme archeology continues

12 notes

·

View notes

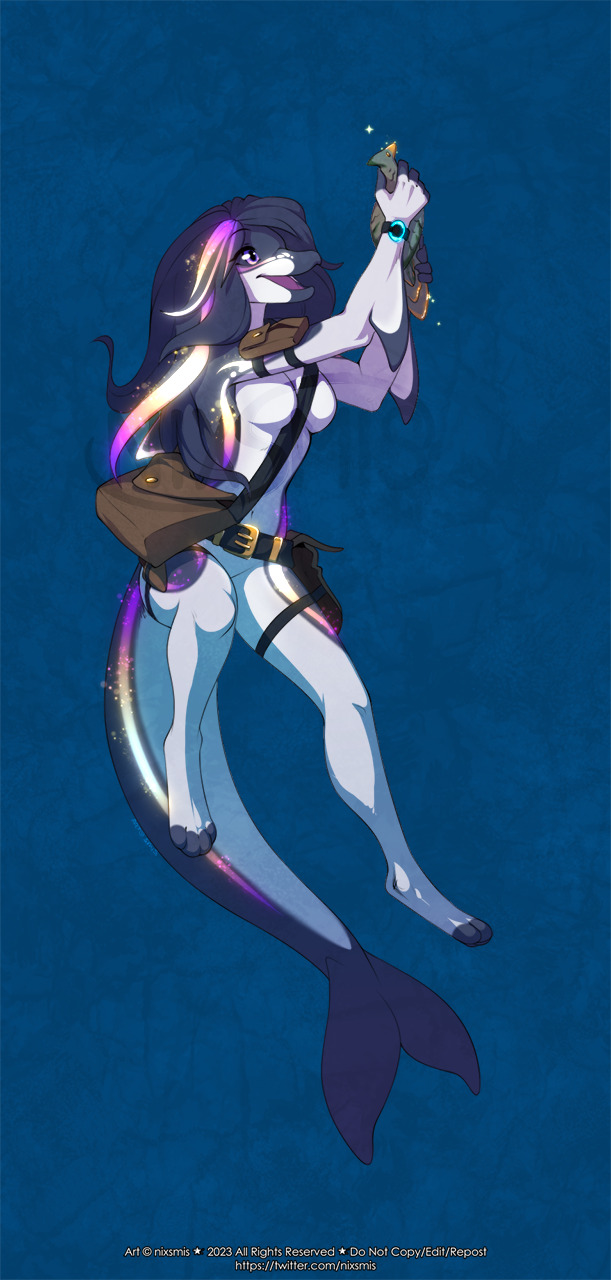

Photo

i'm open for wing-its weekly on fridays/saturdays via google form linked on FA/twitter!

Moonbeam Patrons get a discounted price on Simple-Cel Wing-its!

https://www.patreon.com/nixsmis

character © NoxDawnsong

art © me

Posted using PostyBirb

#furry#anthro#dolphin#aquatic#glow#discovery#bird#statue#archeology#explorer#nixsmis#dawn#purple#pink#gold#belts#swim#swimming#underwater

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

If It Were Not Uncovered No One Would Believe It..

Biblical Archaeological sites that show that the Bible is real such as proof that pool of Siloam was real and the Tel Dan Stele.

Joe Kirby from Off The Kirb Ministries studies Christian archaeologists amazing discoveries for God.

youtube

#bible#jesus christ#christianity#jesussaves#scriptures#archeological#archeology#forensic examination#real history#the truth#archeological discoveries#skepticism#atheism#atheists#atheist#Youtube

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Listening to Imahara Joe talking about arcane batteries and holding a dagger to Caleb Widogast's throat like, "Give me all the papers you've published in the last six years, motherfucker."

#critical role#cr spoilers#sir. sir.#like it's possible it's just tech that hadn't really made it to wildemount six years ago. very reasonable.#but it's equally possible it's a lot of archeological discoveries out of preserved ancient ruins.#hmm. no idea who might be publishing that kind of research.

310 notes

·

View notes

Text

At midday on the road into Grünland, a Mennonite colony in the Bolivian department of Beni, the only sound is a distant chainsaw.

On either side, strips of deforested land extend into the distance. Underfoot, the soil is scattered with shards of ceramic and bone: remnants of the pre-Columbian peoples that this part of the Bolivian Amazon, known as the Llanos de Mojos, once supported.

Archaeologists are only just beginning to understand the scale and complexity of these societies, but all the while, the agricultural frontier keeps advancing, destroying sites before they can be studied. The environmental damage of deforestation is well-known, but the Llanos de Mojos reveals another side of its impact: the loss of human history.

Grünland was founded in 2005 by Mennonites, members of the tightly-nit Anabaptist Christian group that began arriving in South America in the early 20th century, in search of isolation and lands to cultivate.

In one field, a Mennonite man called Guillermo was resting in the shade of his tractor. He cheerfully acknowledged finding ceramics and bones while working the land.

Umberto Lombardo, an Italian earth scientist and one of a handful of academics who study the archaeology of Beni, probed gently with questions about the topography of the land when it was first deforested.

The Llanos de Mojos is an almost completely flat region, so any elevated areas are a sure sign of human activity. Lombardo walked about, stopping here and there to pick pieces from the earth of what was once a vast human-made mound, now partly flattened by the farmers.

“The surface of the site is completely destroyed, changed, because the earth has been moved, the pottery broken,” said Lombardo. “That part of the archaeological archive is lost.”

The Mennonites are just one facet of Bolivia’s booming agribusiness, and what is happening in Grünland is happening all over Beni.

The Bolivian government has big plans for the sector. Today, the country has roughly 4m hectares of cultivated land and 10 million cattle. By 2025, the government wants 13m hectares and 18 million cattle.

On the current trajectory the government will undershoot those targets substantially. Nonetheless it has boosted the sector’s growth by allowing more deforestation and reducing fines for illegal deforestation.

In 2021, Global Forest Watch placed Bolivia third in the world for loss of primary forest, behind Brazil and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Ranked by population, Bolivia is first by a distance.

Most of this deforestation is happening in two departments: Santa Cruz and Beni. But it is in Beni that a unique archaeological heritage is at risk.

“Archaeology is everywhere in Beni,” said Lombardo. “They say if you put up a roof, you have a museum.”

The Amazon basin was once considered to be pristine wilderness, but a growing body of research has found traces of a vast network of earthworks predating the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Americas and implying the existence of large, complex societies.

#Bolivia#deforestation#archeology#pre columbian#beni#mennonites#I feel a bit awkward tagging it with that last one#apologies to the mennonites of tumblr I guess#but look it does have a distinctly doctrine of discovery flavor if you ask me#(I say that making some assumptions as to where Guillermo is from)#there is more active element of#colonization#going on as well#agriculture#ranching

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discovery of Roman Buried Coins in Wales Declared Treasure

Two sets of coins found by metal detectors in Wales are actually Roman treasure, the Welsh Amgueddfa Cymru Museum announced in a news release.

The coins were found in Conwy, a small walled town in North Wales, in December 2018, the museum said. David Moss and Tom Taylor were using metal detectors when they found the first set of coins in a ceramic vessel. This hoard contained 2,733 coins, the museum said, including "silver denarii minted between 32 BC and AD 235," and antoniniani, or silver and copper-alloy coins, made between AD 215 and 270.

The second hoard contained 37 silver coins, minted between 32 BC and AD 221. Those coins were "scattered across a small area in the immediate vicinity of the larger hoard," according to the museum.

"We had only just started metal-detecting when we made these totally unexpected finds," said Moss in the release shared by the museum. "On the day of discovery … it was raining heavily, so I took a look at Tom and made my way across the field towards him to tell him to call it a day on the detecting, when all of a sudden, I accidentally clipped a deep object making a signal. It came as a huge surprise when I dug down and eventually revealed the top of the vessel that held the coins."

The men reported their finds to the Portable Antiquities Scheme in Wales. The coins were excavated and taken to the Amgueddfa Cymru Museum for "micro-excavation and identification" in the museum's conservation lab. Louise Mumford, the senior conservator of archaeology at the museum, said in the news release that the investigation found some of the coins in the large hoard had been "in bags made from extremely thin leather, traces of which remained." Mumford said the "surviving fragments" will "provide information about the type of leather used and how the bags were made" during that time period.

The coins were also scanned by a CT machine at the TWI Technology Center Wales. Ian Nicholson, a consultant engineer at the company, said that they used radiography to look at the coin hoard "without damaging it."

"We found the inspection challenge interesting and valuable when Amgueddfa Cymru — Museum Wales approached us — it was a nice change from inspecting aeroplane parts," Nicholson said. "Using our equipment, we were able to determine that there were coins at various locations in the bag. The coins were so densely packed in the centre of the pot that even our high radiation energies could not penetrate through the entire pot. Nevertheless, we could reveal some of the layout of the coins and confirm it wasn't only the top of the pot where coins had been cached."

The museum soon emptied the pot and found that the coins were mostly in chronological order, with the oldest coins "generally closer to the bottom" of the pot, while the newer coins were "found in the upper layers." The museum was able to estimate that the larger hoard was likely buried in 270 AD.

"The coins in this hoard seem to have been collected over a long period of time. Most appear to have been put in the pot during the reigns of Postumus (AD 260-269) and Victorinus (AD 269-271), but the two bags of silver coins seem to have been collected much earlier during the early decades of the third century AD," said Alastair Willis, the senior curator for Numismatics and the Welsh economy at the museum in the museum's news release.

Both sets of coins were found "close to the remains of a Roman building" that had been excavated in 2013. The building is believed to have been a temple, dating back to the third century, the museum said. The coins may have belonged to a soldier at a nearby fort, the museum suggested.

"The discovery of these hoards supports this suggestion," the museum said. "It is very likely that the hoards were deposited here because of the religious significance of the site, perhaps as votive offerings, or for safe keeping under the protection of the temple's deity.

By Kerry Been.

#Discovery of Roman Buried Coins in Wales Declared Treasure#coins#collectable coins#roman coins#metal detecting#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire#roman art

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

The tomb of the first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang, despite being involved in one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of all times, endures as a mystery to archaeologists and historians as it remains largely sealed up and unexplored.

14 notes

·

View notes