#african cosmology

Text

Palo Mayombe: Kongo-derived Afro-Cuban Spirituality — Lawrence Talks!

“This complexity described in the Bantu-Kongo word for person, muntu is a ‘set of concrete social relationships ... a system of systems; the pattern of patterns in being.’ The person is contextualized as a system participating in other systems, a pattern, a ripple that is sourced and from a source.”

— Kimbwandende Kia Bunseki Fu-Kiau, African Cosmology 42

Dr. Kimbwandende Kia Bunseki Fu-Kiau, a Congolese native and scholar of African religion, captures the essence of Kongo cosmology with this quote, and from this cosmological structure lies the roots of the African diasporic religion Palo Mayombe. Just as a person is “a system of systems; the pattern of patterns in being,” ancestral reverence and inclusion positions humans through a multitude of bodies that have come before them. Ancestral veneration is at the core of many African Diasporic spiritualities. Many individuals who grew up in traditional Christian churches are leaving beliefs of Christendom in search for traditional religions that help them connect with their ancestors. Religious and spiritual systems like Ifa, Santeria, Vodou and Conjure have been popularized, sometimes in negative ways by the media, but for the most part these are the spiritualities that people turn to first in their exploration of African traditional religions (ATR). And what is known of Palo Mayombe by the general public is not a large amount of information by any chance. A Google search locates some articles which picture Palo as the “dark side” of Santeria, which is far from the truth. However, to understand Palo as a distinct spiritual system outside of other African diasporic religion, one must understand its BaKongo cosmological foundations.

History of ancient Kongo cosmology

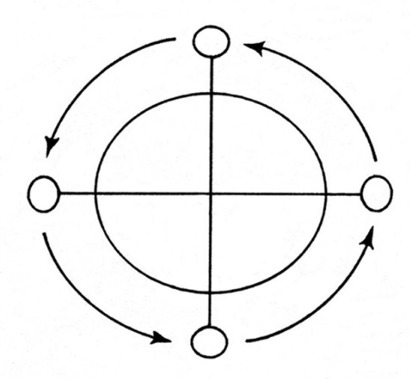

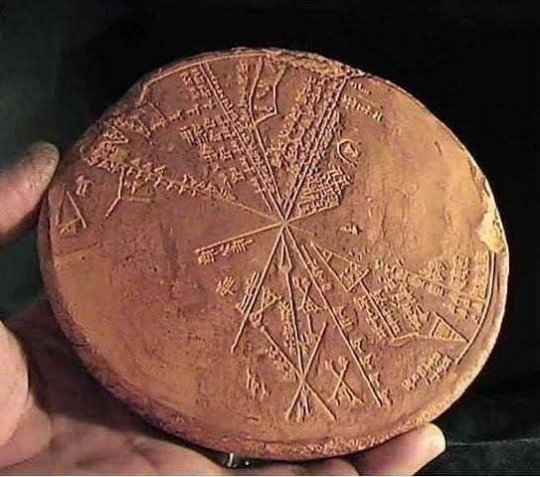

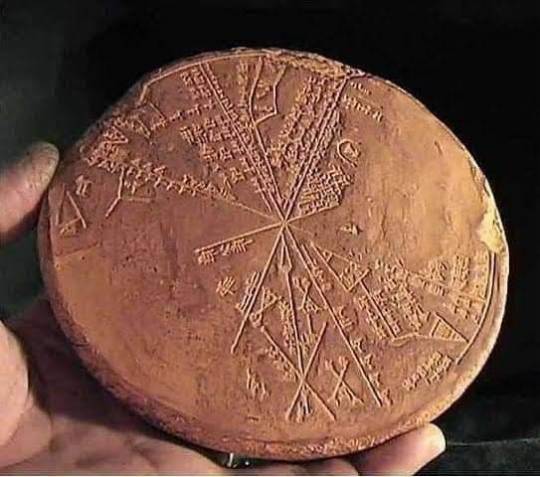

Figure 1: Kongo cosmogram (dikenga)

Fortunately, there is a symbol that captures the essence of Kongo cosmology. The Kongo cosmogram is a cosmological symbol that represents the very patterning of the life process. This symbol is a pre-colonial representation of the cosmogram, as it was conceptualized before European colonization in 1482[1]. It is called the dikenga in the KiKongo language, literally meaning “the turning;” it stands for the cycling of the sun around four cardinal points: dawn, noon, sunset, and midnight when the sun is shining in the world of the dead. Composed of a cross, a circle, and usually arrows, this symbol was found in Kongo material culture well before the contact of colonial Christianity and its cross motif. Anthropologist Robert Farris Thompson, a scholar of Kongo art and religion, says that the “dikenga represents the ultimate graphic design, containing key concepts of Bakongo religious belief, oral history, cosmogony, and philosophy, and depicting in miniature the Bakongo conceptual world and universe” (Thompson 110). The key principle of the dikenga is that nothing ever survives “intact” because nothing ever survives in a fixed form. It is this spiral that is the basic element of Kongo spirituality.

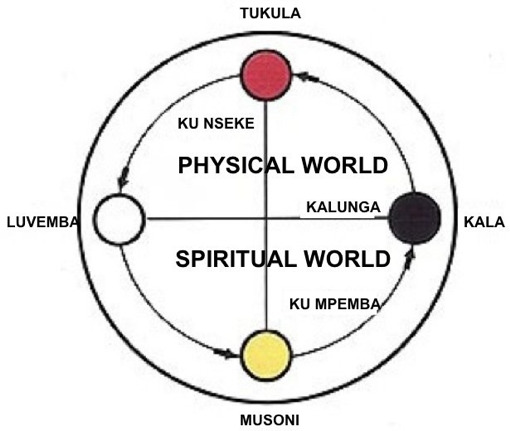

Figure 2: Dikenga

In his seminal piece on Kongo cosmology entitled African Cosmology of the Bantu-Kongo: Principles of Life & Living, Dr. Fu-Kiau explains the motion of the dikenga as the process of ancestralization, of dying and being reborn as an ancestor, through the heating and cooling of existence. This explanation of death and ancestralization is at the core of Palo Mayombe.

Origins of Palo Mayombe

Palo Mayombe is a Kongo derived religion from the Bakongo Diaspora. This religion was transported to the Caribbean during the Spanish slave trade and sprouted in Cuba mostly and in some places in Puerto Rico in the 1500. As the enslaved were forced out of their homelands, their beliefs went with them. Spanish colonialists in Cuba initiated a strategy in the sixteenth century to create mutual aid societies, called cabildos or cofradías, which served to cluster Afro-Cubans into different ethnic categories. This was a strategy of “divide and rule” designed to foster social differences across groups within the enslaved population so that they would not find a unifying focus through which to rebel against the colonial government. In contrast to the extensive blending of diverse African cultures that would be seen in Haiti and Brazil, Cuban cabildos contributed to rich continuations of Yoruba culture in the development of Santería and to largely separate developments of BaKongo beliefs in Palo Mayombe (Fennel). Elements of Catholic beliefs were incorporated into both Santería and Palo Mayombe due to the imposition of the Spanish colonial regime and the cabildo system.

Figure 3 Palo Mayombe Ceremony

Palo Mayombe is very nature-based. Although most African Diasporic religions base rituals and practices in nature, palo (meaning “stick” or “segment of wood” in Spanish) solely depends on the material elements of nature to access the spiritual realm. In Cuba, the Kongo ancestor spirits are considered fierce, rebellious, and independent; they are on the “hot” scale of natural forces. Just as the importance of ancestralization mentioned above, the ancestors are present and inclusive in the practitioner’s life. Nzambi Mpungo is the greatest force in which paleros or paleras (Palo practitioners) call God. Nzambi Mpungo is literally the first ancestor, the initial iteration which all human life flows. Nzambi was viewed as having created the universe, people, spirits, transformative death, and the power of minkisi (ritualized, material objects). The Godhead was thus viewed as being removed from mortal concerns, and supplications were made instead to the ancestor spirits or the intermediary spirits created by Nzambi. Below Nzambi are the mpungus (elemental forces), the ancestors, and the spirits of natural forces (Bettelheim). Each mpungu is similar to an orisha from Yoruba culture due to shared African derived origins, but the two are not the same entity by any means. The mpungu are Afro-Cuban spirits, specific to their diasporic groundings and to the lands of the Diaspora. However, due to their origin

The material tools of Palo Mayombe

Cigars are used to enter into a trance-like state in order to more easily connect with spirits. Special machetes and chains are also used in spirit pots. Candles and rum are essential elements for any Palo ritual. The nganga is used to describe an iron cauldron filled with dirt and specialized sticks; this aids the palero/a in communication with the spirit. In Central America, Cuba and the Caribbean, this cauldron is called a Nganga-Prenda because the culture of modern day and the influence of Latin American's spiritualism in Palo Mayombe.

Figure 4: Prenda de Lucero

The Muertos are important entities in the Palo religion. The house of the dead is where the Palo spirits and the ancestors reside. As illustrated through the Kongo cosmogram above, Palo cosmology does not believe in death, but a continual cycle through various forms. It is the process of ancestralization that makes communication with the spirits of the dead accessible. In the Kongo tradition, ancestors, who have access to invisible forces, have the duty to protect the living. In exchange, the ancestor’s descendants have the obligation to take care of the ancestor’s memory and to venerate their earthly representation. This is why bones are another central tool in Palo. After a person has passed, the bones remain, and the bones carries the essence of a soul long after a person is gone. Bones are thus a sacred item in Palo Mayombe and are usually incorporated in Palo rituals. Usually an ancestor altar is an essential piece in the house of a palero/a, along with offerings of food, drink, and special itemize to venerate their ancestors.

Like many ATR’s and magical system, initiation of some kind is needed in order to practice. Guidance from the elders of the religion is highly encouraged, especially since the ways of the spiritual system is nothing like physical realms.

Palo Mayombe and Other Religious Connections

The influence of Palo Mayombe can be found in Central America, Brazil, and Mexico and in the United States. There are different sects of Palo (Palo Monte, Christian-based Palo, Jewish-based Palo) that come from different lineages and distinct engagements with the cultural environment around the practice. There is another Kongo-derived religion in Brazil is Quimbanda, which is a mixture of traditional Kongo, indigenous in India and Latin American spiritualism. Palo Mayombe is the engagement of Kongo influence in the Caribbean and the wider Diaspora. It has its own priesthood and set of rules and regulations. Rules and regulations will vary according to the Palo Mayombe house to which an individual has been initiated into.

Some people who practice Palo might mix other African-derived systems, like Ifa, Vodou, or Santeria, but Palo is a religion in its own right. For example, Yemoja, the orisha of the ocean and motherhood, may be seen as the same energy as Madre de Agua, the mpungo of the ocean and of motherhood. Although these spirits may have similar functions within the religions, they are two separate entites from particular cultural origins and with specific needs. It is quite common for spiritual seekers to be initiated in multiple religions, so it is of great importance to make sure each path is approached. Although there are other religious elements in Palo, it is all included in the practice and not separated within the religion. When Portuguese missionaries brought the message of Christianity to the Kongo/Bantu, the natives embraced it…while continuing their own native practices (Jason R. Young, Rituals of Resistance). So, this pattern of centripetal inclusion is also present in Palo Mayombe. As Iya TeeDee Oshún, a priestess of African diasporic religions, commented in a recent Facebook post:

“Palo is a beautiful road for those of us that it is for. It's also not just some shit you get done real quick before you ‘elevate’ because that's what Iya's spirit guide said to her in the shower. (Not making that up at all.) It's definitely not Iya nor Baba's "witchcraft pot" in the closet or behind the washing machine or above the grease stain in the garage. It's rarely what I hear when people talk to me in Yorabalese” (2019).

Iya’s mention of “Yorbalese” speaks to a common trend of people in the Diaspora making all of African-derived religions about orisha Ifa/Nigeria, but Palo is of the BaKongo Diaspora. The only system close in origin and practice to Palo is African American Hoodoo, which uses similar elements of the heating and cooling of herbs in spiritual work.

Conclusion

When one decides to take a step into the spirituality of Palo Mayombe, the journey really is a deep engagement with their ancestors and with the raw elemental forces of nature. It is a spiritual awareness that provides protection for the community and the self. The ancestors are the root of one’s existence; the root is the culminating point from which all life springs. This Afrocentric view of cosmology in which Palo Mayombe is grounded, deals with the consciousnesses of nature and of ancestry. Anyone who claims Palo Mayombe as a “dark” or unorthodox religion does not understand the Kongo origins of which Palo operates.

[1] The Kongo cosmogram is a pre-Christian symbol, but due to the iconography of the Christian cross, many people overlap their meanings

#Palo Mayombe Kongo-derived Afro-Cuban Spirituality#Palo#ATR#Congo#African Cosmology#Ancestry#African Religions#IFA#Palo Monte#Kongo

1 note

·

View note

Text

Stars are not just distant specks of light in the African night sky but the guiding lights of mythology, culture, and spirituality.

Indigenous astronomical knowledge is recorded among many African tribes like the Dogon people of Mali, who have rich astronomical knowledge and are said to have made ancient observations of the planetary orbits of Saturn, Mars, Venus and Jupiter with her four major moons.

The traditional astronomical knowledge of the San and Nguni people of Southern Africa is recorded to have guided their agriculture irrigation systems and inspired their religious practices.

In many African societies, navigating life with the guidance of stars has birthed a rich reservoir of practical knowledge useful for timekeeping, agriculture, geography, record keeping and history.

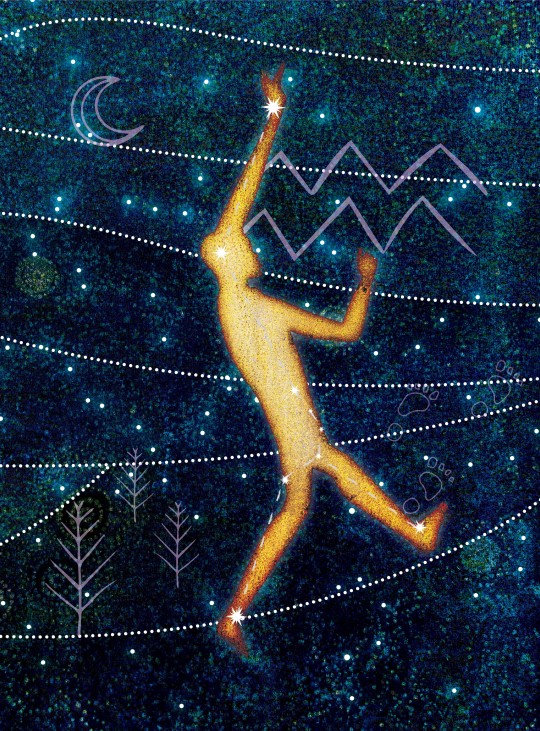

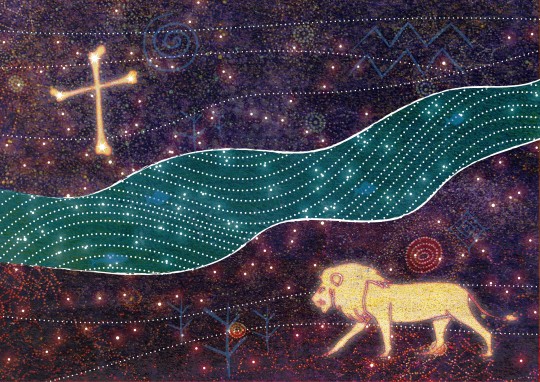

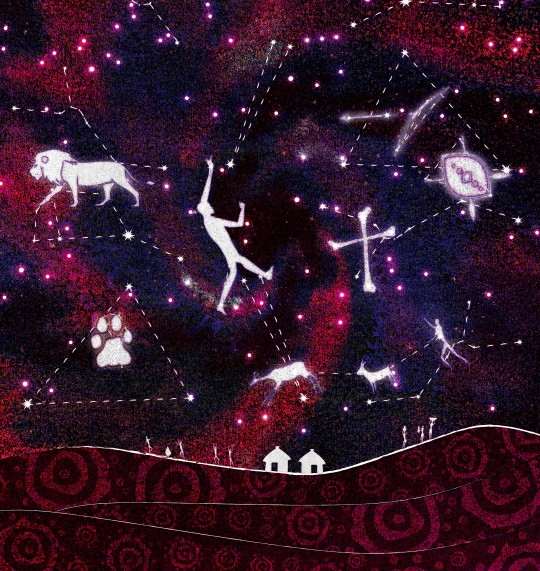

As we explore culture and astronomy from the Chokwe perspective, we must state that we see the skies as we are. Our place on the planet determines our seasons, which affects what heavenly bodies we can observe. Perceptions of star patterns are influenced by the latitude of the observer, and from around 10 degrees south, the Chokwe had the geographical placement to observe and intertwine their star knowledge with their practices and identity.

For the Chokwe, stars tell the story of their people, weaving an intricate tale that forms the fabric of their identity. To the Chokwe, the life of a star is like the story of man, starting with birth, coloured by obstacles and triumph, before ending with the honour of death. The night sky has served as a source of wisdom, a symbol of royalty, and a connection to their revered ancestors.

To learn Chokwe astronomy, we must begin with Tangwa, the sun; Ngonde, the moon's phases; Litota, the stars; and Ntongonoshi, the universe in relation to the stars.

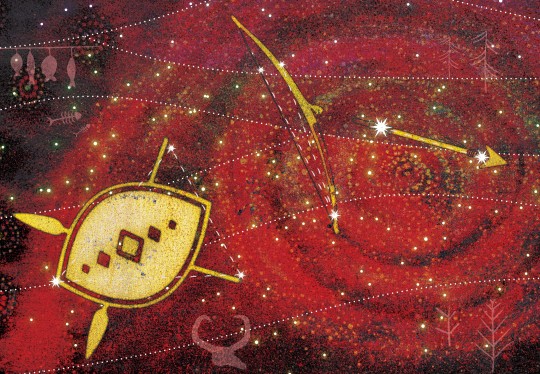

Royalty is a central part of Chokwe culture and is reflected in the sky where we see Ndumba, the lion that walks among the Tulamba - the ancestors, who guide his invisible stride in the Milky Way, leaving paw prints of litota in his path. The Chokwe people refer to the Milky Way as the Mulawiji or the Resting River, and it is used primarily as a star calendar and a compass. This shows an intimate knowledge of the skies as the orientation of the Milky Way changes considerably over the course of the year. Chokwe diviners call the Milky Way the Mulalankungu, which means the King's Road. Nkungu is the name of the great, ancient Chokwe king, and the term refers to him. The Milky Way is a significant part of divination stories, and the diviner's basket, or Ngombo, has objects that represent the stars that the diviner uses as symbols for interpretation.

We are also introduced to Tutumwe Twa Mwanangana, which means 'Child of Wisdom' or 'Sending a Message to the Lord of the Land'. This constellation is depicted as four stars displaying a running, sweating messenger sent to announce the arrival of Mwenga, the new wife represented by the morning star, Venus. We see him spanning across four stars encapsulated in the three constellations of Bootes, Coronae Borealis and Herculis. The four stars, Alphecca, his head; Coronae Borealis accentuating the curve of his powerful hips as he runs; Herculis is his leg extended behind him and in his outstretched hand, Arcturus, the bright message of wisdom.

The beauty of Chokwe cosmology is endless, with serendipitous parallels to Western astronomy. For example, the hunter seen in Orion's Belt is also seen as a hunter by the Chokwe, and they call it Tujita Jita, symbolically interpreted as 'go to fight and always win'. Interestingly, for the Chokwe, the hunter is much closer to his dog in the constellation than in Greek and Egyptian mythology, where the dogs are in separate Canis Minor and Major constellations. Tujilika spans across three modern constellations of Triangulum Australe, Circinus and Centaurus. The symbolic meaning of Tujikila to the Chokwe people is 'the children are protecting you.'

The Nkungu – The Southern Cross represents the ancestors' bones shown by the four brightest stars connected in a cross, and this constellation guides the Mukanda, a circumcision initiation ceremony practised by the Chokwe.

The Seven Sisters, or The Pleiades, are Van Ava Nkungulwila, a lion's claws. Nkungulwila refers to the Nkungu clan and its people, and just as they are together on earth, they are together in the heavens, forming a relationship between heaven, earth, life, and death. The Chokwe see the heavens as their ancestors' home; in their cosmology, when people die, they are reborn in the lion's claws – The Seven Sisters. Considering this belief, it is fascinating to note that astronomers have recognised that this constellation is a star factory where new stars are created as the interstellar gas cloud contracts under the force of gravity. There are reddish stars within the constellation that astronomers recognise as dying stars in a supernova, which the Chokwe recognise as the Nalindele; a star whose season is over and is waning; this story is told in relation to an old wife.

Ancient Chokwe star lore, steeped in symbolism and cultural significance, aligns intriguingly with Western scientific discoveries. It's a reminder that despite diverse perspectives, our shared celestial heritage connects us all.

Modern Zambian society is embracing its traditional star knowledge in exciting ways. Young Zambians blend age-old wisdom with contemporary science and technology, forging a path towards the stars. A brief look can be taken at the enduring legacy of the Zambia Space Program of Edward Nkoloso, who coined the term Afronauts, which has come to embody a time when Zambians were bold and brave about exploring the wondrous mysteries of the universe.

The stars have a unique way of uniting us all, transcending borders, cultures, and time. Our fascination with the night sky is universal, but it's crucial to stay curious and remember that the cosmos is vast and diverse, just like the cultures it inspires. Whether you're gazing at the stars from the Chokwe heartlands of Northwestern Zambia or the bustling streets of Lusaka, we're all part of a timeless story that stretches beyond the horizon of our understanding. The stars above are the same stars that have guided us since time immemorial, reminding us of our shared journey through the great expanse of the universe.

0 notes

Photo

The Sirius Mystery

#sirius#dog star#ancient astronomy#ancient egypt#ancient babylon#sumerians#dogon tribe#mali#west africa#african spirituality#cosmology#books

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celebrating Black History Month

The Metaphysical and Spiritual Contributions of the Dogon TribeAs we immerse ourselves in the rich observance of Black History Month, it is essential to explore not only the historical and cultural milestones achieved by African descendants but also the profound spiritual and metaphysical insights they have offered to the world. Among these contributions, the Dogon Tribe of Mali stands out,…

View On WordPress

#African Heritage#Black History Month#cosmology#Creation Myth#Dogon Tribe#Holistic Perspective#Interconnectedness#metaphysics#Sirius#Spirituality

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seed Conversations

Upgrade your plan to use this premium blockUpgrade

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

When you tag things “#abolition”, what are you referring to? Abolishing what?

Prisons, generally. Though not just physical walls of formal prisons, but also captivity, carcerality, and carceral thinking. Including migrant detention; national border fences; indentured servitude; inability to move due to, and labor coerced through, debt; de facto imprisonment or isolation of the disabled or medically pathologized; privatization and enclosure of land; categories of “criminality"; etc.

In favor of other, better lives and futures.

Specifically, I am grateful to have learned from the work of these people:

Ruth Wilson Gilmore on “abolition geography”.

Katherine McKittrick on "imaginative geographies"; emotional engagement with place/landscape; legacy of imperialism/slavery in conceptions of physical space and in devaluation of other-than-human lifeforms; escaping enclosure; plantation “afterlives” and how plantation logics continue to thrive in contemporary structures/institutions like cities, prisons, etc.; a “range of rebellions” through collaborative acts, refusal of the dominant order, and subversion through joy and autonomy.

Macarena Gomez-Barris on landscapes as “sacrifice zones”; people condemned to live in resource extraction colonies deemed as acceptable losses; place-making and ecological consciousness; and how “the enclosure, the plantation, the ship, and the prison” are analogous spaces of captivity.

Liat Ben-Moshe on disability; informal institutionalization and incarceration of disabled people through physical limitation, social ostracization, denial of aid, and institutional disavowal; and "letting go of hegemonic knowledge of crime”.

Achille Mbembe on co-existence and care; respect for other-than-human lifeforms; "necropolitics" and bare life/death; African cosmologies; historical evolution of chattel slavery into contemporary institutions through control over food, space, and definitions of life/land; the “explicit kinship between plantation slavery, colonial predation, and contemporary resource extraction” and modern institutions.

Robin Maynard on "generative refusal"; solidarity; shared experiences among homeless, incarcerated, disabled, Indigenous, Black communities; to "build community with" those who you are told to disregard in order "to re-imagine" worlds; envisioning, imagining, and then manifesting those alternative futures which are "already" here and alive.

Leniqueca Welcome on Caribbean world-making; "the apocalyptic temporality" of environmental disasters and the colonial denial of possible "revolutionary futures"; limits of reformism; "infrastructures of liberation at the end of the world."; "abolition is a practice oriented toward the full realization of decolonization, postnationalism, decarceration, and environmental sustainability."

Stefano Harney and Fred Moten on “the undercommons”; fugitivity; dis-order in academia and institutions; and sharing of knowledge.

AM Kanngieser on "deep listening"; “refusal as pedagogy”; and “attunement and attentiveness” in the face of “incomprehensible” and immense “loss of people and ecologies to capitalist brutalities”.

Lisa Lowe on "the intimacies of four continents" and how British politicians and planters feared that official legal abolition of chattel slavery would endanger Caribbean plantation profits, so they devised ways to import South Asian and East Asian laborers.

Ariella Aisha Azoulay on “rehearsals with others’.

Phil Neel on p0lice departments purposely targeting the poor as a way to raise municipal funds; the "suburbanization of poverty" especially in the Great Lakes region; the rise of lucrative "logistics empires" (warehousing, online order delivery, tech industries) at the edges of major urban agglomerations in "progressive" cities like Seattle dependent on "archipelagos" of poverty; and the relationship between job loss, homelessness, gentrification, and these logistics cities.

Alison Mountz on migrant detention; "carceral archipelagoes"; and the “death of asylum”.

Pedro Neves Marques on “one planet with many worlds inside it”; “parallel futures” of Indigenous, Black, disenfranchised communities/cosmologies; and how imperial/nationalist institutions try to foreclose or prevent other possible futures by purposely obscuring or destroying histories, cosmologies, etc.

Peter Redfield on the early twentieth-century French penal colony in tropical Guiana/Guyana; the prison's invocation of racist civilization/savagery mythologies; and its effects on locals.

Iain Chambers on racism of borders; obscured and/or forgotten lives of migrants; and disrupting modernity.

Paulo Tavares on colonial architecture; nationalist myth-making; and erasure of histories of Indigenous dispossession.

Elizabeth Povinelli on "geontopower"; imperial control over "life and death"; how imperial/nationalist formalization of private landownership and commodities relies on rigid definitions of dynamic ecosystems.

Kodwo Eshun on African cosmologies and futures; “the colonial present”; and imperialist/nationalist use of “preemptive” and “predictive” power to control the official storytelling/narrative of history and to destroy alternatives.

Tim Edensor on urban "ghosts" and “industrial ruins”; searching for the “gaps” and “silences” in the official narratives of nations/institutions, to pay attention to the histories, voices, lives obscured in formal accounts.

Megan Ybarra on place-making; "site fights"; solidarity and defiance of migrant detention; and geography of abolition/incarceration.

Sophie Sapp Moore on resistance, marronage, and "forms of counterplantation life"; "plantation worlds" which continue to live in contemporary industrial resource extraction and dispossession.

Deborah Cowen on “infrastructures of empire and resistance”; imperial/nationalist control of place/space; spaces of criminality and "making a life at the edge" of the law; “fugitive infrastructures”.

Elizabeth DeLoughrey on indentured labor; the role of plants, food, and botany in enslaved and fugitive communities; the nineteenth-century British Empire's labor in the South Pacific and Caribbean; the twentieth-century United States mistreatment of the South Pacific; and the role of tropical islands as "laboratories" and isolated open-air prisons for Britain and the US.

Dixa Ramirez D’Oleo on “remaining open to the gifts of the nonhuman” ecosystems; hinterlands and peripheries of empires; attentiveness to hidden landscapes/histories; defying surveillance; and building a world of mutually-flourishing companions.

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson on reciprocity; Indigenous pedagogy; abolitionism in Canada; camaraderie; solidarity; and “life-affirming” environmental relationships.

Anand Yang on "forgotten histories of Indian convicts in colonial Southeast Asia" and how the British Empire deported South Asian political prisoners to the region to simultaneously separate activists from their communities while forcing them into labor.

Sylvia Wynter on the “plot”; resisting the plantation; "plantation archipelagos"; and the “revolutionary demand for happiness”.

Pelin Tan on “exiled foods”; food sovereignty; building affirmative care networks in the face of detention, forced migration, and exile; connections between military rule, surveillance, industrial monocrop agriculture, and resource extraction; the “entanglement of solidarity” and ethics of feeding each other.

Avery Gordon on haunting; spectrality; the “death sentence” of being deemed “social waste” and being considered someone “without future”; "refusing" to participate; "escaping hell" and “living apart” by striking, squatting, resisting; cultivating "the many-headed hydra of the revolutionary Black Atlantic"; alternative, utopian, subjugated worldviews; despite attempts to destroy these futures, manifesting these better worlds, imagining them as "already here, alive, present."

Jasbir Puar on disability; debilitation; how the control of fences, borders, movement, and time management constitute conditions of de facto imprisonment; institutional control of illness/health as a weapon to "debilitate" people; how debt and chronic illness doom us to a “slow death”.

Kanwal Hameed and Katie Natanel on "liberation pedagogy"; sharing of knowledge, education, subversion of colonial legacy in universities; "anticolonial feminisms"; and “spaces of solidarity, revolt, retreat, and release”.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Yoruba religion (Yoruba: Ìṣẹ̀ṣe), West African Orisa (Òrìṣà), or Isese (Ìṣẹ̀ṣe), comprises the traditional religious and spiritual concepts and practice of the Yoruba people. Its homeland is in present-day Southwestern Nigeria, which comprises the majority of Oyo, Ogun, Osun, Ondo, Ekiti, Kwara and Lagos States, as well as parts of Kogi state and the adjoining parts of Benin and Togo, commonly known as Yorubaland (Yoruba: Ilẹ̀ Káàárọ̀-Oòjíire).

It shares some parallels with the Vodun practiced by the neighboring Fon and Ewe peoples to the west and with the religion of the Edo people to the east. Yoruba religion is the basis for a number of religions in the New World, notably Santería, Umbanda, Trinidad Orisha, and Candomblé.[1] Yoruba religious beliefs are part of Itàn (history), the total complex of songs, histories, stories, and other cultural concepts which make up the Yoruba society.

The Yoruba name for the Yoruba indigenous religion is Ìṣẹ̀ṣẹ, which also refers to the traditions and rituals that encompass Yorùbá culture. The term comes from a contraction of the words: Ìṣẹ̀, meaning "source/root origin" and ìṣe, meaning "practice/tradition" coming together to mean "The original tradition"/"The tradition of antiquity" as many of the practices, beliefs, traditions, and observances of the Yoruba originate from the religious worship of Olodumare and the veneration of the Orisa.

According to Kola Abimbola, the Yorubas have evolved a robust cosmology. Nigerian Professor for Traditional African religions, Jacob K. Olupona, summarizes that central for the Yoruba religion, and which all beings possess, is known as "Ase", which is "the empowered word that must come to pass," the "life force" and "energy" that regulates all movement and activity in the universe".Every thought and action of each person or being in Aiyé (the physical realm) interact with the Supreme force, all other living things, including the Earth itself, as well as with Orun (the otherworld), in which gods, spirits and ancestors exist. The Yoruba religion can be described as a complex form of polytheism, with a Supreme but distant creator force, encompassing the whole universe.

The anthropologist Robert Voeks described Yoruba religion as being animistic, noting that it was "firmly attached to place".

Each person living on earth attempts to achieve perfection and find their destiny in Orun-Rere (the spiritual realm of those who do good and beneficial things).

One's ori-inu (spiritual consciousness in the physical realm) must grow in order to consummate union with one's "Iponri" (Ori Orun, spiritual self).

Iwapẹlẹ (or well-balanced) meditative recitation and sincere veneration is sufficient to strengthen the ori-inu of most people. Well-balanced people, it is believed, are able to make positive use of the simplest form of connection between their Ori and the omnipotent Olu-Orun: an Àwúre (petition or prayer) for divine support.

In the Yoruba belief system, Olodumare has ase over all that is. Hence, it is considered supreme.

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brownskin#afrakans#brown skin#african culture#afrakan spirituality#orisa#Ìṣẹ̀ṣẹ#Ori Orun#Ori#oyo#ogun#lagos#nigeria#nigerian#nigerians#vodun#yoruba religion#shango#oludamare#Olodumare#Candomblé#Trinidad Orisha#Yorubaland#Ilẹ̀ Káàárọ̀-Oòjíire#santería#umbanda

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

I ain't much of an artist (so be nice) but I've been working on new ref sheets for months. I hope you like it and it gets my ideas across.

My fursona is a Wolf Person from my nations stories, but I tend to say red wolf (canis rufus) for simplicity's sake. It's easier than giving a cosmology lesson and recapping about 2 traditional sagas, a folktale, and a couple language jokes more times than not. A Wolf Person is not really a wolf, but they are an unparalleled hunters with stories of them in hunting bands, killing monsters, and even acting as assassins. Backed up with magic powers of their own from healing things with spit to making magic arrows from their whiskers.

Mine works as a Librarian, using those hunting skills to hunt down information. He practices southern cunning, a syncretic magic from my Appalachian home that combines the folk traditions of Tsalagi (my folks), Irish, Scottish, German, and West African peoples into something it's own. Helps with doing magical oddjobs for the magical and non-magical folks in the community.

I tried my best to layer meaning for me in there, things from home. The story he's based off of is deeply personal. There are tattoos for stories I grew up with, basket patterns, ribbons, and beading. Earrings a cousin of mine wears to powwow. I've been in this fandom a long time and having something that reads native and pushes back on some of the more racist elements of fandom is important to me. Especially considering this is basically me as a wolf (person). I hope y'all like him too.

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Love yourself enough to learn about yourself and observe the transformation that takes place! The Home Study Course is an exploration of African spiritual cosmologies and practices, featuring a range of healers, practitioners and scholars across a range of traditions. Covering a variety of themes including the Concept of Creation, Natural Forces, Ancestors, Shrines & Altars, African Forms of Prayer and more... www.ancestralvoices.co.uk/digital-home-study-course @shiftingyourparadigm https://www.instagram.com/p/Cp_M-1kDQOO/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

For Ytasha Womack, the Afrofuture Is Now

The writer and filmmaker discusses the blend of theoretical cosmology and Black culture in Chicago’s newest planetarium show.

Ytasha Womack, a screenwriter on “Niyah and the Multiverse,” currently playing at the Adler Planetarium in Chicago, is the author of numerous works including “Black Panther: A Cultural Exploration."

By Katrina Miller, New York Times, March 16, 2024.

On Feb. 17, the Adler Planetarium in Chicago unveiled a new sky show called “Niyah and the Multiverse,” a blend of theoretical cosmology, Black culture and imagination. And as with many things Afrofuturistic, Ytasha Womack’s fingerprints are all over it.

Ms. Womack, who writes both about the genre and from within it, has curated Afrofuturism events across the country — including Carnegie Hall’s citywide festival — and her work is currently featured in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Afrofuturism is perhaps most popularly on display in the “Black Panther” films, which immerse viewers in an alternate reality of diverse, technologically advanced African tribes untouched by the forces of colonialism. (In 2023, Ms. Womack published “Black Panther: A Cultural Exploration,” Marvel’s reference book examining the films’ influences.)

But examples of the genre include the science fiction writer Octavia Butler, the Star Trek character Nyota Uhura and the cyborgian songs of Janelle Monáe. Some even envision the immortality of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman whose cells were taken without consent for what became revolutionary breakthroughs in medicine, as an Afrofuturist parable.

Ms. Womack was one of the scriptwriters for “Niyah and the Multiverse.” She spoke with The New York Times about what Afrofuturism means to her, the process of weaving the genre’s themes with core concepts in physics and how the show aims to inspire. This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

How do you define Afrofuturism?

Afrofuturism is a way of thinking about the future, with alternate realities based on perspectives of the African diaspora. It integrates imagination, liberation, technology and mysticism.

Imagination is important because it is liberating. People have used imagination to transform their circumstances, to move from one reality to another. They’ve used it as a way to escape. When you are in challenging environments, you’re not socialized to imagine. And so to claim your imagination — to embrace it — can be a way of elevating your consciousness.

What makes Afrofuturism different from other futuristic takes is that it has a nonlinear perspective of time. So the future, past and present can very much be one. And that’s a concept expressed in quantum physics, when you think about these other kinds of realities.

Those alternate realities could be philosophical cosmologies, or they could be scientifically explained worlds. How we explain them runs the gamut, depending on what your basis for knowledge is.

Which Afrofuturist works have influenced you?

I think about Parliament-Funkadelic, a popular music collective of the 1970s. As a kid, their album covers were in my basement. A lot of artists during that era — Herbie Hancock, Miles Davis, Earth, Wind & Fire, Labelle — had these very epic, Afrofuturistic album covers, but Parliament-Funkadelic sticks out. There’s one depicting Star Child, the alter ego of George Clinton, the lead musical artist, emerging from a spaceship. That sort of space-tastic imagery was abounding for me as a kid.

“The Wiz,” a reimagining of “The Wizard of Oz,” was on all the time in my house growing up. It had this fabulosity to it — a heightened dream world that reflected 1970s New York. You had the Twin Towers in Emerald City, the empty lots Dorothy walked through with all the trash, the Wicked Witch running a fashion sweatshop, representing the garment district. The film took an urban landscape and made it fabulous, tying in this theme of Dorothy coming into her own through her journey.

Those are images that had a very strong impact on me. As I matured, I got into house music and dance, and began to see relationships between rhythm, movement, space and time. It’s not always something I can give language to, but it’s certainly become a basis for how I talk about metaphysics, in a physical kind of way.

What inspired your team to create “Niyah and the Multiverse”?

We wanted to tell a story about a young girl named Niyah, who wants to be a scientist and who is figuring out who she is — not just on Earth, but also in the universe.

Niyah looks for insight from her grandparents, who explain some of the symbolism of the African artwork in her home. She thinks about concepts she has learned from her science teacher. And she even meets her future self, who is a theoretical astrophysicist. Together, the two explore some of the more popular multiverse theories that scientists are looking at today.

Which theories are those?

Niyah learns about the many-worlds theory, which is this idea that all of your choices evolve into different universes. The choices you make create new paths, essentially creating multiple existences of yourself.

She learns about bubble theory, which says that after our Big Bang, more universes sort of bubbled off, each with their own laws of physics. Niyah also explores the idea of shadow matter, in which particles get reassembled as similar entities in mirror universes.

So there’s this parallel between Niyah learning about the multiverse and also exploring her own identity through her ancestral heritage.

Right. Because both of these are paths of meaning, different ways of understanding who we are. Afrofuturists tend to think in a way that is accepting of a lot of different realities anyway, so it was a pretty seamless experience to weave the physics and other aspects of the genre together. There’s already this intergenerational, or interdimensional, element to the conversation and the art that comes out of it.

The show is presented in the planetarium dome, which has a 360-degree screen, so it’s very immersive. Stepping into the space and watching the show feels like an interdimensional experience of its own.

The first audience to see it had a very emotional response. Some people were crying. There were Black women in the audience saying they always wanted to see this kind of imagery, that they had wanted to be scientists at one point in time. Others were deeply touched by the vibrancy of the show, of how it was able to bring these multiverse theories to life.

It’s impressive that these physics concepts, which can be difficult for people to understand or relate to, are made so accessible with examples that are not only imaginative but very rooted in Black culture.

Right. And it wasn’t difficult for us to do that, because as Afrofuturists, we operate in that space. It’s just about mirroring a way of being that we have always been immersed in.

I think “Niyah and the Multiverse” expresses that we all have different relationships to space and time. We are all looking to understand who we are, where we come from and where we can go in this broader space-time trajectory.

And maybe for some, the show normalizes the idea that there are kids who are Black who dream and are curious about the world. That curiosity can take them in the direction of becoming an artist, or becoming a scientist.

What challenges did you face in tackling the multiverse?

In trying to write some elements of the story, we had to push our own imagination to come up with what a universe might look like if you’re not using the laws of physics that exist in this one. Like, what does it mean to have your particles reassembled into something else? Sometimes we’d come up with ideas for different worlds, and our science consultants would say that already exists.

For me, this shows the beauty of bridging art and science. Artists can give visuals and narratives to ideas that scientists come up with. Or it could happen the other way around: Artists imagine something, and scientists think about what might be needed to support a universe that looks that way.

Image

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Voodoo and Hoodoo: What’s the Difference?

If you live in America, you have undoubtedly come across the terms of voodoo and hoodoo. What is the difference between the two, and how does African (umbrella term) culture play a role in each?

Voodoo

(A.K.A. Vodou, Voudou, Vodun) Voodoo is a religion that originated within Africa amidst the Atlantic slave trade. Its structure comes from a mix of traditional religions of West and Central enslaved Africans (Yoruba, Kongo, and Fon). Once brought to the Hispaniola island, Voodoo saw influences of the culture of the French colonialists who controlled the colony of Saint-Domingue (Freemasonry).

Many Haitians who practice Voodoo also practice Roman Catholicism, not seeing a contradiction between the two systems existing simultaneously. Characterized as Haiti’s “national religion”, Voodoo is one of the most misunderstood religions in the world. Voodoo is monotheistic, giving the teachings of a single supreme God. Believed to have created the universe, this entity is called Bondye or Bonié. For Vodouists, Bondye is seen as the ultimate source of power. This perception of God is also seen as remote, not involving itself in human affairs. While Vodouists often equate Bondye with the Christian God, Vodou does not incorporate belief in a powerful antagonist that opposes the supreme being akin to the Christian notion of Satan.

Vodou also holds the belief of many beings known as Iwa, a term that varies in its translation from “spirits” to “gods”. These beings can in many ways be equated to Christian angels in many of its cosmology. The lwa can offer help, protection, and counsel to humans, in return for ritual service. Each lwa has its own personality and individual correspondences. They can be either loyal or capricious in their dealings with their devotees, with many believing that the lwa are easily offended. When angered, the lwa are believed to remove their protection from their devotees, or to inflict harm.

Vodou also teaches a perspective of the human soul, which is believed to be divided into two parts (both of which exist within the head of a person). One of these is the ti bonnanj ("little good angel"), and it is understood as the conscience that allows an individual to engage in self-reflection and self-criticism. The other part is the gwo bonnanj ("big good angel") and this constitutes the psyche, source of memory, intelligence, and personhood. Vodouists believe that every individual is intrinsically connected to a specific lwa. This lwa is their mèt tèt (master of the head). They believe that this lwa influences the individual's personality. At bodily death, the gwo bonnanj join the Ginen, or ancestral spirits, while the ti bonnanj proceeds to the afterlife to face judgement before Bondye.

Vodou does not promote a dualistic belief in a division between good and evil. It offers no prescriptive code of ethics. Rather than being rule-based, Vodou morality is deemed contextual to the situation.

It is very important to respect Vodou as the closed practice that it is. While misunderstood through various contextualizations, it is a religion felt deeply by a group of people who use it to guide their lives. Those outside do not have the right to infringe upon said spaces.

Hoodoo

It is important to understand that Hoodoo does not describe a religion. Rather, Hoodoo is a set of mystical beliefs hailing from along the Mississippi River with influences from Indigenous herbalism, African spiritualities, and Christian influences. Practitioners of Hoodoo are called rootworkers, conjure doctors, conjure man or conjure woman, root doctors, Hoodoo doctors, and swampers.

Many Hoodoo traditions specifically draw from the beliefs of the Bakongo people of Central Africa during the Atlantic slave trade. After their contact with European slave traders and missionaries, some Africans converted to Christianity willingly, while other enslaved Africans were forced to become Christian which resulted in a syncretization of African spiritual practices and beliefs with the Christian faith. Enslaved and free Africans learned regional indigenous botanical knowledge after they arrived to the United States, including another influence to what would become known as Hoodoo.

During the transatlantic slave trade a variety of African plants were brought from Africa to the United States for cultivation (okra, sorghum, yam, benneseed, watermelon, black-eyed peas, etc.). African Americans had their own herbal knowledge that was brought from West and Central Africa to the United States. When it came to the medicinal use of herbs, African Americans learned some medicinal knowledge of herbs from Indigenous peoples. However, the spiritual use of herbs and the practice of Hoodoo remained African in origin as enslaved African-Americans incorporated African religious rituals in the preparation of North American herbs and roots.

Hoodoo was also a key part in black revolution in the United States. Enslaved women would use their knowledge of herbs to induce miscarriages so white owners wouldn’t be able to take their children. There were also examples of hoodoo being used to poison and kill white slave owners. The Bible itself, in conjunction with Hoodoo, was used in slave liberation. Free and enslaved people could read the stories of the Hebrews in the Bible, and found them similar to their situation in the United States as slaves. The Hebrews in the Old Testament were freed from slavery in Egypt under the leadership of Moses (held to be a conjurer in the beliefs of many who practice Hoodoo).

Hoodoo is also a closed practice, requiring initiation for practitioners.

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deep dives into folklore: creation myths

Creation myths are narratives that attempt to explain the origins of the universe, humanity, and the natural world. They serve as the foundational stories of various cultures, reflecting their beliefs, values, and cosmological understandings. Despite originating from diverse civilizations across time and geography, creation myths often share striking similarities while also showcasing distinct cultural nuances. This essay delves into the universality and diversity of creation myths, examining their common themes, differences, and possible origins.

One of the remarkable features of creation myths is the recurrence of certain themes across cultures. The notion of a primordial chaos or void from which the world emerges is a prevalent motif. For instance, in the Babylonian Enuma Elish, the universe is born from the union of primordial deities Tiamat and Apsu, symbolizing chaos and fresh waters respectively. Similarly, in the Maori creation myth of New Zealand, the universe is conceived in the embrace of Rangi (the sky father) and Papa (the earth mother) from the primal darkness of Te Po.

Another common theme is the concept of a divine creator or creators who shape the cosmos. Whether it's the monotheistic God of Genesis fashioning the world in six days or the Hindu god Brahma emerging from the cosmic egg to initiate creation, the idea of a supreme being or beings bringing order to chaos permeates many myths.

Furthermore, the emergence of humanity often involves divine intervention or the manipulation of natural elements. In Greek mythology, Prometheus forms humans from clay, while in the Aboriginal Dreamtime stories of Australia, ancestral beings shape the landscape and imbue it with sacred significance.

Despite these universal themes, creation myths exhibit immense diversity due to the unique cultural contexts in which they arise. Indigenous cultures, for example, often emphasize the intimate connection between humans and nature in their creation narratives. The Navajo creation story, for instance, speaks of the emergence of the Navajo people from the underworld through four different worlds, each characterized by distinct natural elements and spiritual challenges.

Similarly, African creation myths frequently incorporate animals as significant characters or ancestors. The Yoruba people of Nigeria, for example, believe in the primordial deity Oduduwa, who descends from the heavens on a chain and spreads sand over the waters to create the first land, symbolizing the interconnectedness of humans, animals, and the earth.

In contrast, some creation myths from ancient civilizations place a greater emphasis on cosmic battles or conflicts among deities. The Norse creation myth, for instance, depicts the struggle between the gods and the primordial giants, resulting in the formation of the world from the body of the slain giant Ymir.

The origins of creation myths are deeply intertwined with the human propensity for storytelling, symbolism, and the quest for meaning. Many scholars suggest that these myths emerge as attempts to make sense of the world and to establish cultural identity and cohesion.

Moreover, creation myths often serve as cosmogonic or etiological narratives, explaining the origins of natural phenomena, societal structures, and moral codes. By providing explanations for the fundamental questions of existence, these myths offer a framework for understanding the universe and humanity's place within it.

Additionally, the transmission of creation myths through oral traditions allows for variations and adaptations over time, contributing to the diversity observed among different cultures. As societies evolve and encounter new experiences, their creation myths may undergo reinterpretation or syncretism with other belief systems, further enriching the tapestry of human cosmology.

Creation myths represent a rich tapestry of human imagination, reflecting both the universal quest for understanding and the diverse cultural expressions of this endeavor. Through the exploration of common themes and cultural variations, we gain insight into the shared human experience and the myriad ways in which different societies have grappled with the mysteries of existence. By studying creation myths, we not only uncover the origins of diverse belief systems but also deepen our appreciation for the profound complexity of human thought and creativity.

#writeblr#writers of tumblr#writing#bookish#booklr#fantasy books#creative writing#book blog#ya fantasy books#ya books#deep dives into folklore#deep dives#writers block#national novel writing month#writers#fantasy writer#am writing#female writers#how to write#fiction writing#story writing#teen writer#tumblr writers#tumblr writing community#writblr#writer stuff#writerblr#writer problems#writers corner#writers community

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

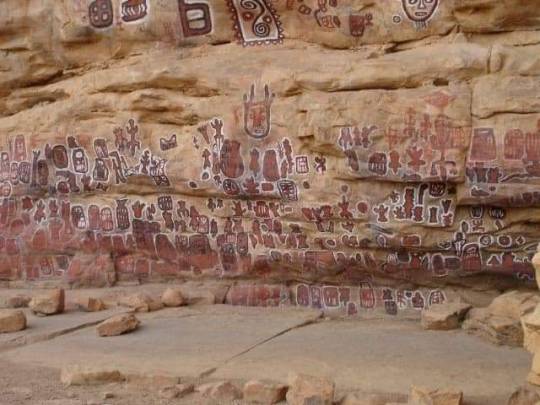

The Dogon People who are Naturally Specialize in Astronomy

The Dogon people are a community of people living in present-day Mali. Their original point of migration to their present locale is not known, however, some scholars have traced their ancestry to the ancient Egyptian empire. They are about 300,000 in population occupying about 700 villages with an average of about 500 inhabitants per village.

The Dogon people possess a rich oral history and knowledge of astronomy, which dates as far back as 3200 BC. According to the oral literature of the Dogon tribe, the star named; ‘Sirius A’ (the brightest star in the night sky with a bluish tinge) has an invisible companion star scientists have named ‘Sirius B’. This companion star is not only invisible to the naked eye but also completes a trip around ‘Sirius A’ every 50 years.

The story of the Dogon people of Mali is a remarkable tale of cultural preservation and astronomical knowledge. The Dogon people are an ethnic group that live in the Bandiagara Escarpment in Mali, West Africa. They are known for their unique and complex cosmology, which includes detailed knowledge of the stars and the universe. According to Dogon mythology, their ancestors were visited by a race of beings from the Sirius star system, known as the Nommo.

The Nommo were described as amphibious creatures who brought knowledge and culture to the Dogon people. They taught the Dogon about the movements of the stars, the nature of the universe, and the importance of harmony and balance. The Dogon have a detailed knowledge of astronomy, including the location and movements of the stars, the moon, and the planets. They have been able to accurately predict astronomical events, such as eclipses and the cycles of the moon, for centuries.

Their astronomical knowledge has been passed down through oral tradition and is considered to be among the most sophisticated in the world. The Dogon are also known for their unique architecture, which includes houses built into the cliffs of the Bandiagara Escarpment. These houses are made of mud and stone and feature intricate carvings and designs.

Despite the challenges of modernization and globalization, the Dogon have managed to preserve their cultural traditions and way of life. They continue to practice their cosmology and hold onto their ancient knowledge, even as the world around them changes.

The story of the Dogon people is a testament to the power of cultural preservation and the importance of honouring and respecting the knowledge and traditions of indigenous peoples. Their astronomical knowledge and unique architecture serve as a reminder of the richness and diversity of African cultures, and their story inspires us to learn more about the history and traditions of Africa and its peoples. #Africa

Joe_Bassey. - twitter

·

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spiritual & Ritual Bathing. The Secret On Why We Do It & Need It.

Not my photo.

If you read my post on baths then you know about bathing and useing a wash. But why do we do it? What is the real purpose of it? In this post I'm going to tell you why.

(See my post on bathing & washes)

Let's start with Spiritual Baths And Ritual Bathing: This practice of bathing has been used by cultures and faiths throughout history, Learning to prepare and perform ritual baths for yourself and others to remove something, gaining something, celebrate a season, welcome someone into a community is apart of our culture and others.

Now in this post I'm speaking to you not just as a priest in voodoo or a root worker but as a minister also.

Spiritual Bathing - Have you ever been asked or wanted to perform a ritual bath for someone? We may go into the ocean, or the waters of a mountain lake, a river, or let's say a waterfall. Why? To help us feel closer to nature or feeling closer to ourselves. Sometimes as spiritual people it helps feel closer to our beliefs our practices or our faith. That’s why water, has been a part of all sorts of rituals for as long as cultures existed.

Water As Part Of Ritual: When i talk about ritual or spiritual bathing, I'm talking about soaking in a special type of water… right...

Water that holds a special meaning, if you're doing a spells, or rituals or a baptisms.

But Why Do We Do A Wash Or Bath? In hoodoo or any culture for that matter, when a spell, ritual or ceremony is completed we do a wash or bath and the purpose of this is "To Seal It All In" 'That's the secret.' A secret that many may not know or may not understand. Because the so called Hoodoo/ African Spiritual books or spiritual books pierod don't tell you.

Why is that? Because a bath especially in the African cosmology a bath is a symbol of rebirth,it helps rids yourself of the old and start a new, a fresh start.

After a spell; what ever spell you are doing, you should finish with a bath. Then with prayer. (Depends on the spell)

If you are doing a baptism you will do a bath or wash you want to finish it off by sealing it all in to stay (with prayer). Once that is done you'll leaving it up to God to take it from there to help you in what ever your trying to achieve.

Bathing Alone: Ritual of bathing along didn't always have to be done for spell work some times it's a time reflection, meditation, pray etc something that we all might need.

These baths gives you a time to let go of old things and welcoming in new things. Like a New Years bath. Just take the time to light a few candles, put on some good music on, and soak in a tub filled with bath salts or oils, whatever makes you feel good.

Ritual Use: There really is no universal recipe for spiritual baths! When you’ve been asked to perform this type of ritual for someone, start by asking them what they need and hope to achieve?

Are they seeking forgiveness? Emotional healing? Creative or inspiration? A blessing for fertility or childbirth, baptism. etc? Each ceremony will be personal but once you know what the ritual is for, you’ll be better prepared for what needs to be done and what to do afterwards like the wright prayer herbs, roots, music etc. You can even get a premade wash and add in your dry ingredients to it.

Asking Your Spiritual Guides: They can help ‘clear’ the space while using Incense like Palo, Sage or another type of incense. During your ritual your guides will assist you if you ask ☺️.

Performing A Bath: Start by pouring the water over the top of the bather’s head down to their feet. ( in case you’re wondering, bathers and the one preforming the bath usually wear ceremonial clothing other times they may wear swim wear… but not always!)

#Spiritual bathing#like and/or reblog!#spiritual work#google search#rootwork#southern hoodoo#traditional hoodoo#follow my blog#rootwork questions#traditional rootwork#southern conjure#southern spirits#african diasporic#african spirituality#ask me questions#message me#Spiritual Baths

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dogon People who are Naturally Specialize in Astronomy

___

The Dogon people is a community of people living in present-day Mali. Their original point of migration to their present locale is not known, however, some scholars have traced their ancestry to the ancient Egyptian empire. They are about 300,000 in population occupying about 700 villages with an average of about 500 inhabitants per village.

The Dogon people possesses a rich oral history and knowledge of astronomy, and this dates as far back as 3200 BC. According to the oral literature of the Dogon tribe, the star named; ‘Sirius A’ (the brightest star in the night sky with a bluish tinge) has an invisible companion star scientists have named ‘Sirius B’. This companion star is not only invisible to the naked eye but also completes a trip around ‘Sirius A’ every 50 years.

The story of the Dogon people of Mali is a remarkable tale of cultural preservation and astronomical knowledge. The Dogon people are an ethnic group that live in the Bandiagara Escarpment in Mali, West Africa. They are known for their unique and complex cosmology, which includes detailed knowledge of the stars and the universe.

According to Dogon mythology, their ancestors were visited by a race of beings from the Sirius star system, known as the Nommo. The Nommo were described as amphibious creatures who brought knowledge and culture to the Dogon people. They taught the Dogon about the movements of the stars, the nature of the universe, and the importance of harmony and balance.

The Dogon have a detailed knowledge of astronomy, including the location and movements of the stars, the moon, and the planets. They have been able to accurately predict astronomical events, such as eclipses and the cycles of the moon, for centuries. Their astronomical knowledge has been passed down through oral tradition and is considered to be among the most sophisticated in the world.

The Dogon are also known for their unique architecture, which includes houses built into the cliffs of the Bandiagara Escarpment. These houses are made of mud and stone and feature intricate carvings and designs.

Despite the challenges of modernization and globalization, the Dogon have managed to preserve their cultural traditions and way of life. They continue to practice their cosmology and hold onto their ancient knowledge, even as the world around them changes.

The story of the Dogon people is a testament to the power of cultural preservation and the importance of honoring and respecting the knowledge and traditions of indigenous peoples. Their astronomical knowledge and unique architecture serve as a reminder of the richness and diversity of African cultures, and their story inspires us to learn more about the history and traditions of Africa and its peoples.

#Africa #blackhistory #africa #BlackHistoryMonth #blackhistoryfacts

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jasper Gets Mad About "The Goodly Spellbook"

Also, re: Coven Olvenwilde, FUCK THEM. Their spellbook is shit and appropriative, they're big on that whole fucking duality of gender thing, and they have some of the grossest fucking takes of all time. And this is coming from the Monarch of Cold Takes themself, so you know it's bad.

Here's an excerpt from the Two Polarities section on page 75 that made my eyebrow pop off of my forehead:

The cosmos is inherently balanced. It provides both light and dark, both life and death, both laughter and tears. For every yang, there is a yin; for every day, there is a night; for every active, outward, or upward action, there is a passive, inward, or downward reaction - and vice versa. Male and female, Sun and Moon, rich and poor, fat and thin, I and you, us and them - there is no one without the other.

And then on page 164, under the title Three Times' the Charm, we have:

Crafters' cosmology contains many triplicities:

matter, magic, spirit

natural, celestial, and ceremonial magic

Goddess, God, and spellcrafter

Maiden, Mother, Crone

seeker, initiate, elder

virginity, fertility, wisdom

male, female, hermaphrodite

birth, life, death

past, present, future

beginning, middle, end

up, down, around

in, out, throughout

and so on...

Like, maybe I'm just a weird Gen Z kid (I say, as a 20-year-old grown-ass adult), but it's pretty tone-deaf to say that male and female are pure opposites and then say that they're actually two out of three genders (ignoring the fact that the term "hermaphrodite" is generally seen as a slur and the preferred term is "intersexed", which has been in use since well before this book was published).

Did I mention that the G slur is used more than the term Romani is? This book actively contributes to the exotification of Romani as "terrible sorcerers and powerful healers".

And I get it, this is a very specific Wiccan coven's craft that we're seeing a snapshot of here, but that doesn't excuse the fact that a good half of the spells written in here are derived from cultures that the very, very white members of Coven Oldenwilde have no business sticking their noses into. There are so many spells here derived from all kinds of cultures with no respect whatsoever for their origins, gods called down without any context of what they're actually like, and a weird obsession with purity as it's connected to the color white, which I'm sure my dearest mutuals have already torn apart enough of.

In the healing section alone, we have:

To Summon Strength's alternate variation, which has you create a mojo bag (which is NOT the same as a spell bag, let's be clear) and invoke a Welsh figure (Olwen) that some people believe to have once been a sun goddess. It also lists "Chinese magic" as part of the inspiration for this version of the spell, but I for the life of me can't figure out where the connection is.

To Induce Therapeutic Sleep, which is said to come from Greek and Native American magic but namedrops a Roman god.

To Break A Drought, which "originates" in Korean, African, European, and Native American magic, calls explicitly to invoke a Korean figure (Aryong-Jong) that the writers claim is a rain goddess. This spell's first line in the spell variations category is, "Stop a drought in deliciously Witchy fashion - strip skyclad, go adoors, and dance in the light of the full Moon amidst droplets from a water sprinkler." Don't do this, especially as the weather turns colder, or you will get sick because you're prancing around naked in sprinkler water.

To Heal Computer Eyestrain which claims to be "Romani magic" (naturally using the G slur instead, because we can't possibly see Romani as people, now can we? SARCASM); did I mention that this book cites Charles Leland for this spell? CHARLES FUCKING LELAND?

To Heal Wounds And Broken Bones is somehow derived from traditional European magic, "German variant", Voodoo herbalism, Irish magic, and Coven Oldenwilde's own practices. Did I mention is also calls for you to invoke Woden?

To Ease Childbirth somehow draws on lore from Ozark Mountain, Hawaiian, Filipino, Roman, German, Sumatran, Chittagong, Punjabi, and Sumerian cultures. It's a whole buffet and isn't even a fucking spell! It's just a list of superstitions!

And we can't leave well enough alone, can we? Because the final spell in the healing section is To Cure Mental Problems. Yes, It's just as ableist and bad as you think it is.

In conclusion, fuck Coven Oldenwilde.

I'm gonna go eat chocolate until I get sick now. Peace out.

69 notes

·

View notes